Archive for the 'Poetics of cinema' Category

A dose of DOS: Trade secrets from Selznick

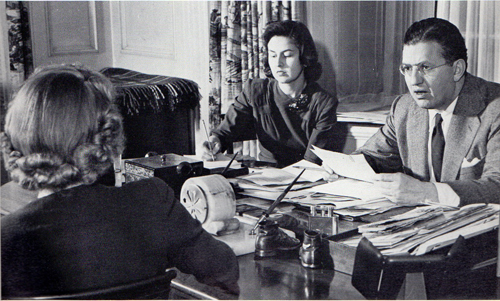

David O. Selznick dictating a memo in 1941. Secretaries are Virginia Olds (back to camera) and Frances Inglis.

DB here:

Tucked neatly within over 4500 archive boxes in Austin, Texas, are tens of thousands of items of information about how the Hollywood studio system worked. The trick is to find the ones you’re looking for…and the ones you didn’t know you should be looking for.

Those archive boxes are housed at the Harry Ransom Research Center at the University of Texas. This magnificent research library holds cultural records of inestimable value, from Whitman and Poe manuscripts to the papers of David Foster Wallace. Among the Center’s impressive film collections, the jewel in the crown is the David O. Selznick papers—a vast trove of material related to the career of the man who produced, some would say over-produced, Gone with the Wind, Rebecca, Spellbound, Duel in the Sun, and other classics of the Hollywood system.

Selznick has been studied from many angles, partly because his collection provides exceptionally full accounts of his activities. He kept, it seems, nearly everything, most famously memoranda. While chainsmoking cigarettes, swallowing amphetamines, writing amateur poetry, and revising scripts and visiting sets and critiquing rehearsals and watching rushes and retaking scenes and checking on rivals’ films, Selznick found time to dictate a blizzard of memos.

From his youth he loved to write memos–“I could sell an idea much better in written form than I could verbally”–and he became adept at dictating them. The results were precise, punchy, and often eloquent. Usually signed DOS (the O being a middle initial he bestowed upon himself), these communiqués could be lapidary (a one-liner asking if the cast is protected from sunburn) or epic. After getting Selznick’s dense, eight-page telegram explaining why Since You Went Away’s nearly three hours could not be reduced, a colleague replied: IF I WERE YOU I WOULD MAKE NO FURTHER CUTS IN SYWA. YOU MIGHT TAKE ABOUT TEN MINUTES OUT OF YOUR TELEGRAM.

In his later years Selznick contemplated publishing a collection called Memo Strikes Back. After he died in 1965, his son encouraged film historian Rudy Behlmer to make a compilation. The result, Memo from David O. Selznick (1972), is a superb collage portrait of the man’s personality and creative years. In the 1980s, the Ransom Center acquired the papers that Behlmer worked through, along with physical artifacts, including costumes from GWTW.

Me-mos, they were called by many, since they seemed to reflect the compulsive micromanaging of their creator. Directors and staff smarted under Selznick’s insistence that he control every creative decision. But for those of us coming afterward, Selznick’s criticisms, complaints, demands, reminiscences, agonies of frustration, and I-told-you-sos help us grasp the concrete problems of filmmaking.

Last week I went to Austin hoping to get some information about how Hollywood creators of the 1940s regarded the task of storytelling. DOS delivered as he did on the screen: splashily.

Paper traces

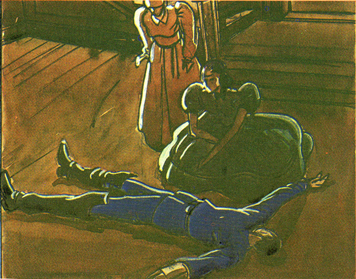

William Cameron Menzies production sketch for Gone with the Wind.

Most commentary on movies stops with the films as we find them. Critics who concentrate on producing interpretations are particularly inclined to play down primary-document research. “We already know,” a famous English critic once told me, “all we need to know.”

In my youth I mostly agreed. Criticism starts with watching and listening closely to what’s happening on the screen. But it doesn’t have to end there. That’s because doing systematic research into film depends on asking questions. And if we’re going beyond a single movie and asking questions about craft, norms, preferred practices, and regulative principles shaping a filmic tradition–in short, questions of film poetics–evidence from practitioners can help a lot.

Hollywood, for instance, has produced a rich array of published materials–interviews, trade coverage, promotion, technical papers–that offer evidence of what filmmakers thought they were doing. You have to read them with a jaundiced eye and be alert for rhetoric, but there’s still a lot to be found in Hollywood’s public presentation of its doings. There’s an even richer lode of unpublished script drafts, production memos, correspondence, transcripts of meetings, court cases, and the like. Mountains of such material remain locked up in studio files. This is what makes the paper collections at major universities, at the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy, at the Museum of Modern Art, and at other institutions precious to those of us studying film history.

Collections like these are grist for the perpetual flow of celebrity biographies and accounts of Hollywood as a business. What, though, can they tell us about the history of film form and style?

Like some published material, these items can suggest how aware filmmakers were of their creative choices. When I was teaching, and the class focused on details of framing or cutting, some students were skeptical. “This is reading too much in,” they’d say. “The director couldn’t have intended that!” And it’s true that sometimes things we think were carefully planned came about through accident or sudden inspiration. Still, in other cases a document shows that filmmakers were consciously aiming at fine-grained effects.

Moreover, archive documents can indicate the array of creative options available—the extent to which one artistic choice is preferred over alternatives that wouldn’t work as well. If filmmaking is problem-solving, we learn about the costs and benefits of competing solutions. We gain a better sense of what can and can’t be done within a tradition when we glimpse filmmakers struggling to decide between expressive possibilities.

Yet another benefit of paging through archival documents is the recognition that we can’t neatly separate filmmaking as business from filmaking as an art. We commonly imagine a studio producer ordering a director to take the cheapest option, to trim costs in every way. Surely this happened a lot. Surprisingly often, though, the suits did and still do invest a lot in artistic effects, even innovative ones. When writing our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960, we were struck by the power of the idea of the “quality film,” that mixture of novelty, showmanship, and high production values that justifies time and resources. A flamboyant crane shot, a complicated lighting scheme, a gorgeous musical score, flashy special effects—in the Hollywood tradition and others, these are appeals worth paying for, even if not every viewer appreciates them.

Perhaps above all, studying records can call our attention to aspects of the film that your initial impression didn’t pick out. A critic can’t notice everything. Examining collections such as Selznick’s, or those housed in our Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, have taught me that what appears effortless or perfunctory on the screen can be the product of intense thought, protracted debate, and hours of hard work. Once you re-tune your attention, even minor moments can be worth thinking about, if only because the filmmakers labored patiently over them.

Getting what you pay for

Since You Went Away (1944).

Selnick was a fussbudget on a scale that makes Schulz’s Lucy look laid-back. He sought control over every aspect of the film, from purchase of material through production, post-production, publicity, and distribution. Gone with the Wind’s volcanic success seemed to confirm the wisdom of his endless tracking of every detail. Because that tracking is made explicit, not to say vehement, in his memos and other correspondence, we get glimpses of Hollywood’s artistic strategies large and small.

Start small. In The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production, I wrote about the “rule of three”–the guideline that presses filmmakers to state important story information three times, preferably with variations (serious/ funny/ pathetic). I gleaned that precept from reading published work, and I could check it by studying the films. Still, further evidence is always welcome, so it’s nice to see a transcript of a story conference during the prolonged rewriting of Portrait of Jennie (1949). The hero, the painter Eben Adams, comes to a coastal town in search of his dream-girl, and DOS suggests:

In every scene he is to ask: “Do you remember a girl named Jennie Appleton?” Use rule of three–two [townfolk] do not remember her–the third one does. . . “Remember her well. . . pretty young thing with dark hair.”

More recently, I’ve been wondering whether studio screenwriters of the 1930s and 1940s were consciously adhering to something like today’s notion of a three-act structure. I’ve found scattered evidence from memos elsewhere that refer to a movie’s “first act” or “last act,” but nothing that indicates a commitment to an overarching three-part layout.

I haven’t found clear-cut evidence in DOS’s papers either, but in another story conference on Jennie, Broadway showman Jed Harris is reported as saying: “The second act–he must get the picture back because that’s all he’ll ever have of her.” In the finished film, Eben doesn’t search for the portrait, but Harris’s remark indicates that he had some sort of multiple-act structure in the back of his mind. He adds later: “The picture at this point is about 1/3 gone, and from here you have the machinery of trying to stop what is impossible to stop.” Far from definitive evidence, but teasing.

Now consider a medium-size example. Kristin and I have argued that many Hollywood films have a symmetrical opening-and-closing structure, often presented as an epilogue that mirrors the beginning. More recently I suggested that this bookend structure often displays an advance/ retreat pattern. At the start, the camera may move into a space or a character may come toward us; at the end, the camera may retreat and/or the characters may turn away or walk into the distance. On Since You Went Away (1944), Selznick sweated over ways to frame this panorama of the American home front. Early on he decided to start his film with an exterior view of the Hilton family home. This image dissolves to a closer view showing a star in the window, which indicates that a member of the family is in the armed forces.

Eventually Selznick decided to end the film by pulling back from a miniature of the house, with a single camera movement replacing the two unmoving shots that started things off. Anne is joyfully embracing her two daughters; they’re inserted as a matte into the upstairs window.

Selznick considered redoing the opening as a slow camera movement in to the window, but only if the miniature was good enough. Perhaps it wasn’t. And at one point he wanted the final shot to start with the star in the window, at least for purposes of the preview screening, “to parallel that at the beginning of the picture.” Again, that wasn’t accomplished, but his playing with possibilities reflects his tradition’s commitment to symmetrical openings and closings.

It would have been far cheaper simply to have ended the film on the three-shot of the women, shown at the top of this section. But Selznick wanted “a nice rounded feeling” in his epilogue, and he was prepared to pay for it. True, he was exceptionally finicky, but going to a lot of trouble and expense to get this formal rhyme was not unusual in studio practice. The hardheaded film business is willing to invest in vivid, emotionally gripping artistry identified with quality moviemaking.

Stylistic trends

Portrait of Jennie (1949).

In broad terms, it’s fair to say that American studio films of the 1940s display a more self-conscious use of long takes, sustained camera movements, and deep-focus cinematography than we find in other eras. (Actually, it’s a trend we find throughout the world at the time, for reasons that aren’t well understood.) But these new techniques didn’t replace traditional analytical editing. They worked within it. Continuity cutting, established in America in the late 1910s, remained the dominant stylistic framework for filmmakers.

Citizen Kane‘s fixed single-shot scenes in depth were very unusual in cinema of the period. More commonly, deep-focus shots, like moving-camera shots, served as establishing framings or otherwise became part of conventionally edited sequences. This middling or compromise style can be found in dozens of films of the forties, and Selznick seems to have more or less consciously gone along with it.

He worried about what he called “cuttiness,” the tendency to break every scene into brief single shots of the players. Often, he suggested, a well-handled two-shot would work better. He told his editor on Since You Went Away to avoid “the conventional treatment of close-ups and reactions.”

It most definitely is not necessary always to treat every one of our scenes with dead center close-ups, and direct cuts or over-the-shoulder angles, when an intimate scene is played between two people.

He goes on to tell a second-unit director that a scene of a couple in a car could be played in one or two setups, perhaps in a single shot “if we could get an interesting composition on the two of them rather than a dead center two-shot on individuals.”

Selznick saw Hitchcock as an editing-biased director and so after signing him to make Rebecca (1940), he warned him and other members of the team to avoid over-cutting. Again, the preference was for a tight two-shot.

The new scene between the girl and Mrs. Danvers on the arrival at Manderley (Script Scenes 130A, 130N and 131) may be very cutty as described in the script, and perhaps ought to be protected in a close two-shot of ‘I’ [the heroine] and Mrs. Danvers, or some other angle that will keep us from playing it in too many short cuts.

In most cases, however, Selznick gave himself an out by treating faster cutting as an alternative. He consistently wanted coverage, as he indicates immediately for the Rebecca scene just mentioned.

However, I suggest we make the short cuts also, as this may be the best way of playing it after all. If we use the camera to move up to Mrs. Danvers for the finish, which is the way I think it should be used, then perhaps the first shot of her should be retaken also.

As the last sentence indicates, Selznick sometimes opts for camera movement to avoid cuttiness. Perhaps the American Hitchcock’s interest in tracking shots that follow characters, particularly glamorous women, through the set stemmed from Selznick’s belief in the power of occasional camera movements. He notes that a tracking shot introducing Alida Valli in The Paradine Case (1948) is too bumpy, asking why the staff couldn’t manage “something as simple as going up to a woman’s face, and then pulling back from it across a set, without the camera shaking in the manner of early silent pictures.”

Yet these longish takes aren’t to be the dominant stylistic approach. Sustained takes often block off choices in post-production. Producers, then and now, want coverage, and you didn’t have to be a micromanager like Selznick to want your directors to give you options for rebuilding scenes in the cutting room. We see this when Selznick objects to John Cromwell’s playing entire scenes in lengthy shots.

This is of course nonsense, since as often as not an incomplete take is better than the identical portion of a complete take. . . . It seems folly to spend hours getting a complete scene instead of just picking up those sections of the beginning or middle or end that have been fluffed.

Some directors resisted by shooting long takes without coverage. Hitchcock did this in one sequence of The Paradine Case and then promoted this “three and a half-minute take” to the Hollywood community, perhaps to make it harder for Selznick to change it. Nonetheless, Selznick cut the scene up. Once freed from Selznick, of course, Hitchcock was able to pursue the long-take option to extremes with Rope (1948) and Under Capricorn (1949).

Despite wanting flexibility in editing, producers can be seduced by the prospect of “pre-cutting” a film–planning the shots so exactly that the film can be “pre-visualized.” The director can thus avoid taking shots that won’t be used. Selznick was proud of William Cameron Menzies’ precise production planning on Gone with the Wind, and this made him believe in the power of the storyboard. When he rewrote a script, which was often, he was inclined to have artists immediately prepare fresh drawings of sets and shots.

Hitchcock had promoted himself as someone who drafted a film on paper so thoroughly that shooting became efficient and predictable. Selznick was therefore startled when Hitchcock proposed a long shooting schedule for Rebecca. “In view of the many speeches he has made to me about how he pre-cuts a script, so as to shoot only necessary angles, it is a mystery to me as to how he could spend even 42 days.”

During shooting, DOS became furious with the pace of production, declaring Hitchcock “the slowest director we have had.” Hitchcock, he believed, was spending more time getting his few angles than directors who shot in normal fashion. Yet Selznick remained susceptible to the dream of pre-cutting. Some years later, he predicted that Since You Went Away wouldn’t take much time in the editing room because the scenes “will be camera-cut to an extra-ordinary degree, and putting it together should take no time at all.” The film’s editing occupied several months.

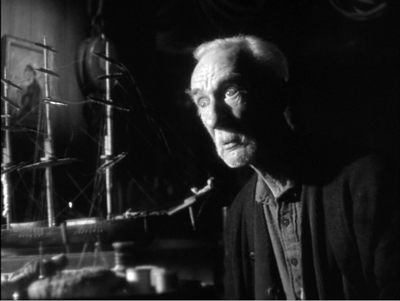

Selznick, then, was attracted to current trends of longish takes and the fluid camera, but like nearly all his peers he saw these as subordinate to the overarching demands of analytical editing, whether through traditional protection coverage or through “pre-cutting.” Something similar seems to have governed his interest in depth staging and deep-focus cinematography. Peppered throughout the memos I examined are his concern for “foreground pieces,” props that can enliven a shot. A miniature sailing ship in Portrait of Jennie, he suggests, is too big for its placement in the shots as taken. “It would have been a far better foreground piece for another angle.” So it became such a piece, as the still surmounting this section indicates.

Of Since You Went Away DOS notes:

I think that lately we have been overlooking chances for good foreground and background planes in our set-ups. I don’t want to over-do this but of a lot of our shots could be much more interesting in this regard.

In particular he emphasizes the bronzed baby shoes introduced in the film’s opening, as the camera glides through the Hilton family parlor picking up traces of the departed father. A later scene, in which Anne writes a letter to her husband Tim, seemed the ideal chance to re-use that prop. “Photographically, I thought it would be much more interesting with the shadow of the shoes, or using the shoes as foreground pieces.” This composition, if it was shot, didn’t appear in the final film, but it shows once again that filmmakers can be aware of broader trends of their period, and that they’re willing to go to considerable trouble to join them.

A striking example of the insistence on participating in the deep-focus trend appears in the files around Spellbound. After arriving in America, Hitchcock occasionally produced some big-foreground depth images, as below in Shadow of a Doubt (1943), and in Notorious (1946).

Such compositions were rare in most films Hitchcock did under Selznick, but in Spellbound Selznick realized the value of keeping up-to-date. The most famous big foreground in the film (and in all Hitch’s work) is seen at the climax, when Dr. Murchison trains his revolver on Constance as she edges out of his office.

This bizarre shot is somewhat anticipated by a less aggressive setup. Constance hears over the radio that the police have tracked J. B. to Manhattan, and she goes into the next room to pack to follow him. The action is handled in a canonical post-Kane composition.

The production records make me wonder whether this shot (presumably using a larger-than-life clock and radio) was filmed under Hitchcock’s supervision. It may have replaced an even more complex shot that cinematographer George Barnes objected to. (I’m still gathering information on this.) In any event, Selznick realized that a minor transitional scene could be dynamized by a flamboyant, difficult-to-achieve image: a throwaway mark of quality.

Pendulum swings of innovation

Since You Went Away.

I’ll save other things I found for future work. Let me finish by talking about how Selznick’s “directing at a distance” shows a craftsman’s concern for novelty and pictorial storytelling.

Hitchcock famously shot the Old Bailey scenes of The Paradine Case with several cameras in an immense set. Selznick may have okayed this tactic on this occasion because it would speed up Hitchcock’s schedule. (Selznick had hoped it would take only one day; it took three for principal photography and several more for pick-up inserts.) But both before and after Paradine, Selznick was interested in extending multiple-camera shooting beyond its normal uses.

Multiple-camera coverage of ordinary scenes had a heyday in the early years of sound, but afterward it was usually reserved for unrepeatable action (fires, stunts, cars going off cliffs) or very big scenes. Selznick had deployed several cameras, including the lightweight Eyemos, during the dance at the airplane hangar in Since You Went Away. Like Welles, he also considered using the tactic for ordinary dramatic scenes. He writes in 1947:

I have long felt that sooner or later, probably when economic necessity dictates, this method of shooting will come into vogue, with far more time spent on rehearsal, far less time on shooting, enormous savings and better quality. I know that for years I have been discussing with Hitchcock my feeling that we could take a film of a particular type, thoroughly rehearse it, and shoot it in a week–and this is just what Hitch is planning to do on The Rope [sic].

Selznick anticipated the practice of multiple-camera television production. It’s intriguing to think of Hitchcock taking this idea and simply substituting one camera for many, creating another technical stunt that could be publicized.

DOS was sensitive to conventions and often sought to refresh them. For one back-projected scene of Portrait of Jennie, he advises Dieterle “to avoid the awful-looking, head-on, two-shot process setups and angle camera in different ways: perhaps with lower cameras, one shooting across Adams at Spinney and the other shooting across Spinney at Adams.” This echoes his concern for finding unusual angles on the process arrangement in Since You Went Away‘s driving scene. He likewise encouraged unusual staging, recalling

the love scene between Freddie March and Janet Gaynor in A Star Is Born, the one in which he takes her home the first night, after the kitchen scene, where the entire scene is played on Freddie’s back; and the love scene in Nothing Sacred in the crate after Carole Lombard has fished Freddie March out of the river. Both of these treatments enormously enhanced the value of these scenes, which shot conventionally would not have been necessarily so effective.

In the first instance, the conversation is handled by an unusually prolonged over-the-shoulder shot that doesn’t show March replying to Gaynor. In the second, the romantic dialogue is emphasized by the darkness of the crate and our inability to see either actor clearly.

Yet Selznick worried about becoming too “arty” as well. During the filming of Since You Went Away he confessed:

I feel that I am at least partially responsible for our increasing tendency to play scenes on people’s backs. . . . In Jane’s attack upon the colonel after the breakfast scene, we are on neither one principal nor the other, but on the colonel’s back and Jane’s back . . . In the church scene there has been talk of playing it on the three backs, but I have tried in the script to indicate that we should not do this.

Stark lighting is of course common in 1940s cinema generally, but Selznick favored it in the 1930s as well, in the shots above and more famously in Gone with the Wind. By the 1940s, Since You Went Away and Portrait of Jennie include scenes steeped in rich shadow areas, cast shadows, and silhouettes.

But here, as elsewhere, DOS’s urge for innovation was curbed by anxiety about going too far. In a memo to Cromwell on Since You Went Away, he wrote that “all of us (mostly myself) are overdoing the silhouette business. . . . Let’s from now on all use this silhouette effect very sparingly, and only when it’s absolutely indispensable to our mood.”

Perhaps what I’ve called his middle-of-the road approach was less a balance and more of a pendulum swing between extremes. He could sometimes foreswear the grand, almost monumental look of many scenes and demand something quieter. At the end of the day when Anne’s husband has left for war, she looks at his unmade bed.

She leaps up and wriggles into it, covering her face with the blankets, and starts to cry.

Commentators often fasten on the twin-beds convention as an example of the naive timidity of studio-era Hollywood. Yet every convention offers opportunities for expression. When Anne rises, the sight of one rumpled bed and one pristine one brings home the husband’s absence in a simple, powerful image, and her plunging into it directly conveys her longing to be in his arms.

I’m absolutely positive that this gag will not get over unless we see the two beds in the clear, one made up and one not made up, before she hops into the other bed. I think these two beds constitute good storytelling.

When the hard-bitten Ben Hecht saw Since You Went Away, he cabled Selznick: “It made me cry like a fool.”

You can certainly argue that Selznick the fussbudget was his own worst enemy. His micromanagement raised his budgets and drove away his collaborators. As the production values grew more inflated, it was hard to recoup costs, let alone turn big profits. Ten years after Gone with the Wind premiered, Selznick’s fiefdom lay in ruins. He withdrew from production, millions of dollars in debt. He wrote in a confidential 1948 memo:

In the final analysis it is my fault for two reasons: (1) my production methods; (2) my tolerance through the years of the wastefulness. . . . The most successful series of pictures ever made in the history of the business has produced profits which are perhaps not more than twenty per cent of what they should be.

Ideas matter in any domain, even in studying Hollywood. And not just the ideas of critics, historians, and theorists. The practicing artisans of the studio system had rich ideas about preferred ways to build plots, to shoot and cut scenes, to mix sound and add music. These norms were seldom stated outright. Were Selznick less interfering, less prone to hesitate between alternatives, less obsessed with minute details, we would not know as much about the workings of the system he sought to rule. He distilled into typescript and double carbons many notions that ordinarily went unstated. His plump files teem with ideas about how films were made, and how their creator thought they should affect audiences. Thanks to institutions like the Ransom Center, his work is preserved to enlighten us about filmmakers’ secrets, even the secrets they don’t know they know.

I’m very grateful to Emilio Banda and the rest of the staff at the Harry Ransom Center, who helped me during my visit. Thanks also to Steve Wilson, Curator of Film there, for advice. And of course thanks to my family–Diane, Darlene, Kewal, Kamini, Megan, and Sanjeev–who made our trip to Austin so enjoyable.

My quotations come from the memos I examined, as well as from other items in Rudy Behlmer’s Memo from David O. Selznick. I also drew on Ronald Haver’s David O. Selznick’s Hollywood (Knopf, 1980), the initial edition of which is surely the most gorgeous book ever published about the American film industry. Haver’s study is not only spectacularly illustrated but deeply researched, and it, like Behlmer’s, is indispensable for the study of the studio system. The Menzies production sketch is taken from the Haver volume.

No less indispensable is Leonard J. Leff’s Hitchcock & Selznick (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1987). After sifting through both the Selznick collection in Austin and the Hitchcock collection at the Academy’s Margaret Herrick Library, Leff produced a detailed account of the two men’s creative work. Hitchcock’s long take in The Paradine Case is promoted in Bart Sheridan, “Three and a Half Minute Take…,” American Cinematographer 27, 9 (September 1948), 304-305, 314.

Paul Ramaeker offers a subtle account of Portrait of Jennie as a “supernatural romantic melodrama” at The Third Meaning.

For more on 1940s stylistic norms, see The Classical Hollywood Cinema, chapter 27, and On the History of Film Style, chapter 6. The first essay in my Poetics of Cinema discusses Hitchcock in relation to trends of the period, concentrating on Rope and long-take options. On Citizen Kane and rationales for deep-focus cinematography, you can go here. I mention a bit about the fashion for the “fluid camera” in 1940s Hollywood in this entry.

William Cameron Menzies served as art director and more for Gone with the Wind, and he and was pressed into service ad hoc for later DOS projects. I think he may have influenced the shadow-drenched style of Since You Went Away and Portrait of Jennie. I wrote about Menzies’ work, and again about deep-space work in 1940s Hollywood, here and here. See also David Cairns’ enlightening essay in The Believer.

Since You Went Away: “I think that Miss Keon had better start preparing a script of retakes and additional scenes. I think we missed a wonderful opportunity in the Christmas scene in not having a shot from the angle of the family, or from the bottom of the stairs, of the Colonel going up the stars with Soda behind him.”

Return to Paranormalcy

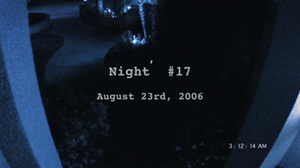

Paranormal Activity (2007).

DB here:

What is there for me to do? Art historian Ernst Gombrich suggested that this is a problem that confronts every creative artist. If you want to make paintings or compose music or direct movies, you confront an existing community of artists and long-established traditions of art-making. You work with what you’re given. You inherit technology and materials, but you also inherit ideas and familiar conventions and well-worn work habits. You want to find a niche, but you’re also in competition with others for it.

You confront, in other words, a kind of ecosystem with its own history and a current state of play. How can you fit your talents and temperament into that ecosystem? How, more specifically, can you create something different?

Variorum moviemaking

Paranormal Activity (2007).

It can be useful to think of commercial filmmaking as this sort of system, a cooperative/ competitive arena challenging directors, writers, cinematographers, and other film artists to innovate. Innovation isn’t the only aim of moviemaking, of course, and just because something is innovative doesn’t mean it’s good. And not all innovations announce the fact; Jean Renoir’s deft uses of space in his 1930s films didn’t trumpet their originality. Innovation can be quiet and subtle.

Still, as students of the art of film, we’re naturally attuned to novelty—a fresh treatment of an established genre, an unusual approach to characterization, a new application of existing technology. If we’re interested in mainstream film, particularly Hollywood’s, we learn things from the way that filmmakers swarm over something new and try to mimic it or tweak it or turn it around. Make a movie about a possessed pre-adolescent girl who needs an exorcism, and soon we’ll have movies about possessed high-school girls, possessed dogs, possessed cars, and so on.

Call it the variorum quality of popular culture—the tendency to explore, sometimes exhaustively, all the possibilities of a single premise. Filmmakers seize an idea and run with it, in different directions. Of course they may be asking, “How can we cash in on this trend?” but in order to answer that they have to ask another question: “What if we did such-and-such differently?” Even if you start by trying to make money, you still have to make a movie. And that movie will need to be minimally distinctive. The question for the filmmaker remains: What is there for me to do?

Something like this process is going on under our noses. Paranormal Activity (2007), Paranormal Activity 2 (2010), Paranormal Activity 3 (2011), and Paranormal Activity 4 (2012, released in October) have become a cheaply made but very successful franchise. Taken together, the four films have won estimated worldwide box-office revenues of $700 million and counting.

Their popularity offers one reason to examine them, but a better reason is that they make the variorum dynamic unusually clear. The originator and director of the first installment, Oren Peli, and the directors who followed (Tod Williams for the second entry, Henry Joost and Ariel Schulman for the last two, along with continuing writer Christopher Landon) were obliged to innovate within very tight limits. From movie to movie, they came up with fresh and unexpected solutions.

This isn’t about proving these movies to be masterpieces or stinkers. Whatever you think about the quality of the innovations I’ll be looking at, they offer us some leads about how filmic storytelling can change under the “selection pressures” of American commercial cinema.

More strikingly, the Paranormal Activity franchise is that rare thing: a popular series that stands out by very specific and noticeable uses of film technique. Audiences eat it up. The suspense and surprises are part of the appeal, certainly, but there’s reason to think that at least some viewers look forward to following each entry’s formal dynamic of familiarity and variation. Filmmaking becomes a kind of gamelike performance that coaxes us to ask: How will they deal the cards this time?

Of course there are spoilers from here on. Even the pictures contain spoilers.

The same, please, only different

The Blair Witch Project (1999).

The broad task that Peli faced when he began work on Paranormal Activity was clear: How to make a diabolic-possession film different from the others? By then, and still, that variant of horror was pretty well-defined. And indeed the film Peli came up with wasn’t that original in outline. A couple is disturbed by mysterious noises and actions in their house. They call in experts and try to find the source of the disturbance. Eventually the woman becomes possessed and kills her lover.

Throughout, the conventions of the supernatural film rule: sudden blackouts, bone-shaking noises emitted by offscreen fiends, and characters exploring basements, closets, moonlit yards, and other scary spaces. Special effects are invoked to levitate victims or drag them by unseen hands. Occasionally we’re faked out by scares launched as pranks that some characters pull on others. As usual, normal, i.e. bourgeois American life, is devastated by supernatural forces. Cozy domestic surroundings, including an array of consumer goods, become menacing. Much of all this was pioneered by The Exorcist (1973), so the tradition has plenty of cobwebs on it.

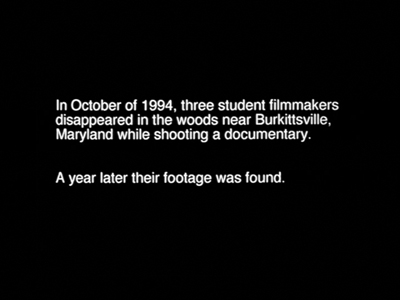

Shooting in seven days on a small budget, Peli settled on a formal framework that borrowed from another tradition, that of the pseudo-documentary fiction film. This too goes far back, to This Is Spinal Tap (1984) and Bob Roberts (1992), and before to Stanton Kaye’s Georg (1964), Jim McBride’s David Holzman’s Diary (1967), and Mitchell Block’s No Lies (1972) , and Peter Watkins’ Culloden (1964) and The War Game (1965). More distant predecessors might be Welles’ 1938 War of the Worlds radio broadcast, or even the fake memoirs we find in the early years of the novel. Today the pseudo-documentary mode, used for comic or dramatic purposes, is familiar to us from television shows like The Office. This mode has its own conventions, such as to-camera interviews and the occasionally awkward framing, most noticeable in the recurring image of a fallen camera.

The pseudo-documentary approach had been tried in the horror film in the 1980s, but it gained attention at the end of the 1990s with The Last Broadcast (1998) and The Blair Witch Project (1999). No surprise: Horror films tend to be low-budget items, and shooting in a run-and-gun manner, with handheld shots and awkward sound, was both cheap and realistic-looking. A cycle emerged, exemplified most notably in the bigger-budget Cloverfield (2008).

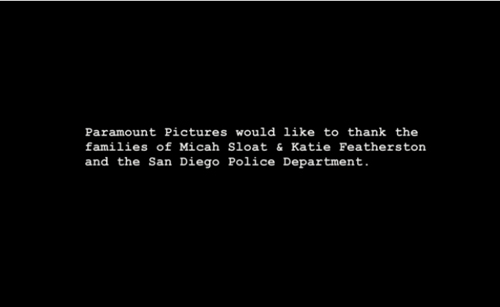

The problem of the pseudo-documentary is to motivate the fact that someone is filming these dramas. Various solutions have been worked out. You might make the protagonist a filmmaker exploring a subject or creating a diary. Or you can pretend that the people being filmed are celebrities (as in Spinal Tap). Or make the act of filming an effort to document dramatic occurrences. Filmmakers face a second problem as well: motivating how the film has been made public. You can, for instance, present it as a TV or theatrical documentary, as Spinal Tap purports to be. More recently another solution has been found. You can suggest that this film has been discovered after the events were over.

Because of this rationale, the approach is sometimes called the “found-footage” treatment, or in Varietyese the “faux found-footage film.” I’m not delighted by this term because for a long time “found-footage” has referred to films like Bruce Conner’s A Movie or Christian Marclay’s The Clock, assembled out of existing footage scavenged from different sources. So I’ll call fictional movies like Blair Witch and Cloverfield “discovered footage” films.

One reason for this name is that these films hark back to an early tradition of literary fiction, that of the “topos of the discovered manuscript” or “the old oak chest.” Here a tale is presented as a manuscript found and prepared for publication by other hands. The purpose, at first blush, is to give the story an air of authenticity. The same urge prevails in the discovered-footage horror movies, which use this blatant artifice to play with the possibility that these weird happenings really took place. As the image surmounting this blog entry suggests, Peli linked his film to this tradition, even letting the all-too-real company Paramount Pictures attest to the veracity of what we’re going to see.

The development of the Paranormal series took place under the sign of rivalry. A great many horror films of the late 2000s and early 2010s used the pseudo-documentary approach, sometimes marking the footage as recovered. After the success of Peli’s original film, intense competition emerged. There was a blatant ripoff (Paranormal Entity, 2009), followed by many others, including the subtler pseudo-doc The Last Exorcism (2010), which seems to presume that we’ll take it as a found-footage item too.

Just as important, in making successors to the original film, Peli and his colleagues had to compete with themselves. So they freshened up their plots. Paranormal 2 features not a live-in couple but a family; Paranormal 3 centers on an unmarried mother, her live-in boyfriend, and her two daughters. Paranormal 4 features a family whose neighbors are a possessed mother and son.

Interestingly, the subsequent films supply relatively little mythical or doctrinal backstory. Although there are always one or two scenes in which the characters launch on some research, the plots mostly minimize exposition about the hows and whys of possession. (Contrast The Exorcist.) We get just enough hints to assume that there’s a demon who offers women worldly goods in exchange for innocent boys’ souls. Mostly the films concentrate on the characters’ responses, chiefly their quarrels about whether the weird happenings are supernaturally caused. Each film needs at least one blocking character, somebody whose skepticism, obstinacy, or cluelessness keeps the plot going and prevents the characters from simply getting the hell out.

The films also vary protagonists and the characters we’re attached to. Micah moves the plot forward in the first entry with his urge to document the weird happenings, while in the second, the father Daniel and his daughter Ali take turns probing what’s going on. In the third film, again it’s mostly a male filmmaker, Dennis, who propels the inquiry, while in the latest iteration, the narrative momentum is passed to the inquisitive teenage girl Alex.

Perhaps the most up- to-date way the filmmakers refresh the franchise is by making the various films interlock. The films set up a chronology that positions the original release as the third phase of a larger action. Paranormal 2 occurs just before the events of the first one, and Paranormal 3 flashes back eighteen years to supply some preconditions for the previous entries. Moreover, some portions of the plots overlap, so that scenes from one installment are replayed in another, explaining how the time frames mesh. This sort of shuffling with time and perspective is nowadays common both within films and across them; the second and third Bourne films offer good examples.

Above all, the filmmakers have created a new ecological niche by virtue of some initial stylistic choices Peli’s first film made. They were striking but exceptionally constraining. To produce more Paranormal films created a very specific set of problems: How to respect those initial constraints and yet rework them in unpredictable ways?

Hand-eye coordination

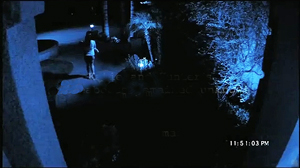

Paranormal Activity 3 (2011).

Cloverfield and The Blair Witch Project use the discovered-footage format to justify their amateurish look. These are on-the-fly records of some pretty strange phenomena. By contrast, the Paranormal Activity series doesn’t limit itself to handheld footage. It sets up a dynamic between that and something quite different: the fixed, distant shot reminiscent of surveillance footage.

The alternatives are laid out in the first film, when Micah, perplexed by the ghostly goings-on, buys a fancy video camera and sets it up in the bedroom he shares with Katie. That way he can capture what’s happening while they are sleeping. At other times he takes the camera off its tripod and shoots the house in the usual handheld, eyewitness way.

The result is a movie, and a series, with two markedly different visual treatments. The handheld footage is pure subjectivity, showing exactly what the camera operator sees. It responds immediately to what’s out there, panning or moving toward things of interest. It also permits fairly close shots of the other characters. By contrast, the locked-down shots are completely objective, recording in the manner of surveillance video. Indifferent to human intentions, the camera may be poorly placed to capture what’s happening. And it’s by and large committed to very wide and distant views, compared to the closer views yielded by the probing handheld lens.

Take the handheld technique first. This yields a severely restricted range of knowledge, as I’ve already discussed in relation to Cloverfield. This narrow range is suited for a film playing up mystery and suspense. In any given scene, we don’t know any more than the camera operator does. But of course this feature is also a drawback, because the filmmaker can’t build suspense through crosscutting—showing, say, a door creaking or a shadow moving somewhere else in the house.

The default for most fiction films is camera ubiquity. That is, in principle the camera can be anywhere and show us anything. If the camera doesn’t do that, you need special justification. So for thrillers or horror films, you can show just advancing feet or clutching hands or scary shadows, because we know that these genres promote gaps in our knowledge. We accept the obvious suppression of information.

Another way to justify not showing everything is attachment to one character’s range of knowledge. This is another common strategy of suspense and horror. Even more restrictive is an optical point-of-view treatment, which might be the polar opposite of camera ubiquity. Hitchcock was particularly keen to find ways he could drill into optical point-of-view as a narrative device.

Treating the camera as a vehicle for subjective POV can yield some sudden shocks. One of the most provocative ones in the Paranormal franchise occurs in the third installment, when Dennis approaches Julia at the top of the stairs. His camera-eye viewpoint makes her seem to be standing there, but as he approaches the perspective changes and we see that she’s actually floating.

In the same installment, the “Bloody Mary” encounter in the bathroom gains force not only through the camera’s limitation to Randy’s optical pov, but through the mirror that in the darkness reflects only the red dot of the camera’s “on” signal. It’s all we have to look at in a scene in which the sounds of thrashing and smashing overwhelm the image.

So the handheld subjective camera of Paranormal Activity and other films in the trend avoids camera ubiquity. This creates familiar problems, but filmmakers in this stylistic cycle have come up with solutions.

*How do you explain why the camera is recording this drama? The standard justification is that a crew has decided for some reason to make a movie about something, as in Spinal Tap and The Last Exorcism. Paranormal Activity finds two more pretexts. The video camera can record home movies in Daddy-cam fashion; this motivation is especially important in Paranormal Activity 2. Or the camera can serve to document the weird goings-on in the demon-haunted homes. This motivation is especially strong for the locked-down surveillance recordings.

The camera operator may be the protagonist or at least a major character. How do you show the character to the audience? Options: Have him or her shoot the act of filming in a mirror (very popular). Have him or her address the camera when it’s resting. Let other characters wield the camera and show the cameraperson. Or set the camera down and let it keep filming, often risking decentered compositions but still indicating things clearly enough.

Sometimes you want camera ubiquity. Shot/ reverse-shot cutting is especially valuable because it can emphasize major lines of dialogue and reactions. How can you achieve this in the subjective-camera style? By cheating a little. For example, a single-camera record can capture the give-and-take of a conversation only by either framing both people in a single shot or by panning between them. If you want proper shot/ reverse-shot cuts you have to use overlapping sound during editing to cover the moments when you stopped the shot or panned to reframe the other character. Even when you establish that two cameras are filming the action, you may have to cheat on position quite a bit. (See this discussion of a scene in The Office.)

Chronicle offers an intriguing example of how these problems can be solved. At the beginning Andrew, shooting into a mirror, explains that he has decided to film everything.

Throughout the early portions of the movie we get only what his camera sees, usually with him behind the viewfinder. But eventually we meet Casey, a young woman who has a camera too. The result is shot/ reverse-shot cutting justified as each camera’s viewpoint.

At the climax, when the boy superheroes fight it out above the city, so many people are filming the scene with cellphones, TV news cameras, and government surveillance, that the action is covered fully from many angles. The visual storytelling achieves camera ubiquity.

The impersonal view

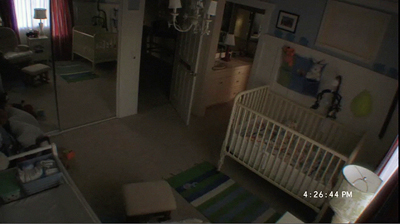

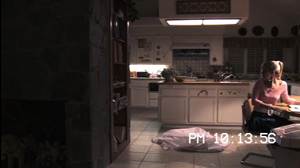

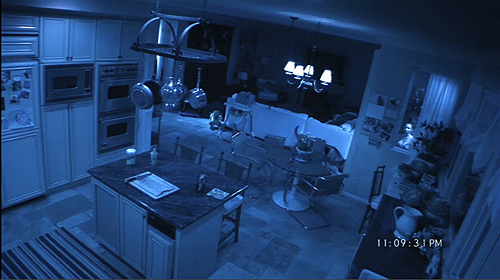

Paranormal Activity 2 (2010).

Many horror films have used the handheld approach, but the strongest innovation of the Paranormal series, I think, is the idea of counterweighting the free-camera shots with fixed-camera footage. Like the moving handheld shot, the locked-down surveillance shots avoid camera ubiquity and restrict us severely. But they have other advantages.

As we’ve seen, the fixed setup complements the human-centered handheld camera. It shows everything in front of it indiscriminately. By prying itself loose from the characters, and filming them while they’re not aware of it—especially when they’re sleeping—it allows us a more neutral sense of the film’s space and the things that happen in it. Just as important, it fits smoothly with some standard horror conventions.

For example, offscreen threats are central to the horror film, and the fixed camera can maintain their effects. As (bad) luck would have it, the cameras set up in Paranormal Activity aren’t always ideally framed for showing everything. Very often they merely suggest the demon’s pursuit of the characters. The demon Toby is just off left of frame in the third installment (he blasts some air at the babysitter Lisa) and some entity like Toby seems to be at work offscreen right in the second one, attracting Hunter’s attention.

Likewise, offscreen sound is crucial to the horror film, as Val Lewton and Jacques Tourneur showed long ago with the sudden intrusion of bus brakes into a suspenseful pursuit in The Cat People. The fixed camera can capture those sounds but because no human agent is behind it, there’s no way it can move forward to explore their sources, as a camera operated by a human might.

The surveillance shots, while limited visually, provide information that the subjective shots don’t. In the first film, while Micah sleeps, the bedroom-cam shows some weird goings-ons that he isn’t aware of—notably, Katie getting up and standing unmoving by the bed for several hours. In later installments, the presence of more than one surveillance camera can provide story information via crosscutting. As with Chronicle, multiplying surveillance views pushes the visual narration toward a more complete (and conventional) coverage of the action.

Crucial to the films’ innovation is the fact that the locked-down shots are distant views. The films have extraordinarily few shots for contemporary productions: about 230 in the first part, about 500 in the second (because of the multiple cameras), about 230 again in part three, and about 320 in the last. The number of setups is greater than these figures would suggest because some cuts are jump cuts or drop-frames within extended camera takes.

Long-take, locked-down shots are common in “festival cinema” but virtually unheard of in mainstream Hollywood film. Remarkably, we have box-office hits consisting of long, static takes that hold multiplex audiences in thrall. Of course the long “empty” takes are recruited to the conventional cause of sustained silence and sudden, startling outbursts. The genre, we might say, motivates the style. The same audience wouldn’t be so tolerant of a protracted shot in Tarkovsky or Hou.

Yet we shouldn’t dismiss these shots as mere gimmicks. Their stillness encourages us to scan these spacious frames for hints about what will happen next. The impersonal lens often lingers on bare spaces, and when something of interest happens we won’t be given a cut in. Sometimes the crucial action is barely there, as when Ali and Brad are hidden in shadow, behind the digital read-out, in the lower right of this shot.

To some extent, the distant framing of the surveillance shots revives classic staging techniques in a cinema that seems largely to have forgotten them. Instead of the barrage of close-ups and rapid shot changes we get with today’s intensified continuity style, we get lengthy, static, often indiscernible images we have to scour for clues.

Granted, often those clues are signaled through slight movements, as in the eerie twirling of the toy spider suspended over Hunter’s crib (top of this section). Centering is also important, as when the Ouija board’s planchette scuttles around and then bursts into flames. Sometimes a character can point to what’s important in the visual field.

For the most part, the static framings yield deep, dense compositions reminiscent of 1910s tableau cinema. In the second installment particularly, key bits of action are pushed very far from us or isolated in apertures. The kitchen camera setup lets Ali’s distant face poke up from the sofa into bare visibility (immediately below), or be framed in the window when she tries to get back in as Abby the dog approaches the locked door. (See bottom of this entry.) Unlike most modern films, these lose a great deal of information on small screens.

Overall, the handheld POV shot and the detached and distant long shot complement each other. Both are well fitted to the demands of the horror film, which requires secrets to be concealed from the characters while throwing out hints to us. Beyond genre conventions, though, these films might train the young audience to be patient and learn to settle into images that ripen slowly and don’t yield their meanings up immediately. Well, I can dream, can’t I?

Stretching the rules

Paranormal Activity 2 (2010).

I’ve spoken of these films in general terms, but what makes the series particularly intriguing to me is the development from one installment to the next. The makers aren’t only competing with other filmmakers; they’re competing with themselves. Each new episode has to innovate within the framework they’ve set up—not only by expanding the story action, as we’ve seen, but also by varying the stylistic parameters. That generates new problems, self-imposed ones, and the search for new solutions.

The original Paranormal Activity sets up many of the stylistic premises of the series: the use of mirrors to introduce the camera and its operator, the idea that the investigator will replay the locked-down footage (and then film that with the handheld camera), and the need for at least one skeptical character who will resist the investigation. Here Micah has one camera, which he carries with him by day and installs on its tripod at night. And the resolution of the film is played directly to the camera, as Micah slips out at night to follow Katie and after a long pause is hurled back into the camera, smashing it to the floor. The tipped-over framing records Katie creeping forward, smiling, and roaring into the lens—her revenge on the filming she hated from the start.

Paranormal Activity 2 is largely a prequel, taking place about a year before the first one. Now the single camera is a daddy-cam, recording the arrival of Hunter, the baby born to Daniel and Katie’s sister Kristi. This camera is really a daughter-cam, because it’s mostly wielded by Ali, Daniel’s daughter by a previous marriage. She drives the investigation, but she’s initially more thrilled than afraid. (She also wonders if the ghost is her mother.) The situation shifts from a live-in couple (Paranormal 1) to a happy nuclear family (Paranormal 2) and from a midrange income level to a very prosperous one.

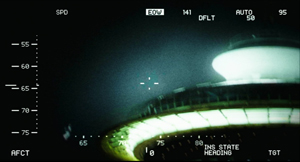

After the house is mysteriously ransacked, Daniel installs a home surveillance system. Six high-angle cameras cover the house. They’re trained on the front door, the back pool, the kitchen, the living room, Hunter’s room, and the master bedroom. In addition, we have Daniel’s Daddy-cam, now outfitted with night vision. This will become important in the climax, allowing us to glimpse, spasmodically, the demon’s response to the attempted exorcism of Kristi.

Naturally all these cameras yield a much-expanded range of knowledge. Now we can see at least part of what’s going on in various parts of the house, and the narration cuts freely from one room to another. Because of the shot scale, though, quicker cutting means that we have to run fast checks in each shot on whether anything seems dangerous.

Important shifts toward camera ubiquity, these new setups also can play a game with our expectations. For example, the eerie shots of the swimming pool at night show the bobbing pool cleaner sidling through the water. Yet Kristi points out that every morning the cleaner has been removed from the pool. The surveillance shots we see never show this, and not until late in the film, when other stretches of the surveillance footage are played, do we see it leave the water. Even sneakier is the tendency of the night footage to mislead us about what’s important. Nearly every night sequence begins with a shot showing the front stoop of the house, but nothing (so far as I can tell) is ever revealed by these images in Paranormal 2, though at the start of Paranormal 4 they pay off by showing Katie leaving with Hunter in her arms.

In context, Paranormal 2‘s recurring shot serves to announce a new sequence of hauntings, but it’s also a little amusing. The standard shot showing a safe household, with no one approaching, serves simply to remind us that the demon is already comfortably inside.

Paranormal Activity 3 is a more distant prequel, setting up the childhood of sisters Kristi and Katie. Here the novelty is the use of VHS tape to record the action. Again, the footage begins as Daddy-cam shooting, as Dennis films Katie’s eighth birthday party and then starts to make a sex tape with Julie. But when the spooky hijinks start, the man of the household decides to investigate. Unlike Micah, though, Dennis is a videographer by trade and so has three cameras at his disposal. He uses one as a handheld device, occasionally set up in his and Julie’s bedroom. He installs another camera in the girls’ bedroom and puts the third one downstairs.

Reducing the “panopticon” of the previous installment from seven to three might be seen as a step backward, but the filmmakers have a clever innovation up their sleeve. Dennis can’t cover the downstairs adequately with his remaining camera. Out of a table fan he constructs a swiveling base to which he can attach a camera. This yields a panning back-and-forth framing.

Of course this mechanical panning is just as little concerned with items of human interest as the static shots of the earlier installments. Indeed, it maintains the horror-film convention of ominous offscreen action, but motivates it as impersonal scanning. The camera slowly reveals pieces of space, but if something exciting starts to happen onscreen, the camera relentlessly turns away.

Set in 2011, Paranormal Activity 4 is the first chronological sequel to the first entry, with a new cast of characters involved in action long after the initial demon outbreak. In some ways, making a teenage girl the protagonist is more conventional than the early films’ focus on couples. Still competing with themselves, the filmmakers needed to recast the series’ stylistic premises. They seem to have asked: Well, who uses dedicated video cameras today—especially if our characters are mostly teenagers? Accordingly, the franchise’s signature seesawing between handheld imagery and locked-down recording is now provided by cellphones and computers.

Although some footage purports to come from a video camera, most of it doesn’t. Alex and her boyfriend Ben set up four laptops around the house, all constantly recording what transpires in the rooms. This tactic allows some changes in the surveillance footage. The camera angle is typically lower than in Paranormal 2, since the laptops are sitting on tables or counters. Moreover, their framings can shift. In the boy Wyatt’s room, his laptop is sometimes closer or farther away, and is sometimes blocked by masses of blankets. The kitchen laptop is shifted around when Alex’s mother moves it closer to her work area.

In addition to recording the household’s supernatural doings, the laptop device lets the teenage heroine Alex have video chats with her boyfriend Ben. In the earlier films we get occasional to-camera monologues, but here we watch Alex talk close to the lens, directly to us, and at length; we see what Ben sees, and sometimes we see him from her screen’s vantage–a sort of virtual shot/ reverse-shot.

At crucial moments Alex picks up the laptop and carries it around with her. As a result, we get more conventional horror-film images of the protagonist—ideally an easily startled young woman—moving through space. In the earlier films, the camera operator’s reactions were given through the subjective framing and offscreen comments, curses, and yelps. Now when Alex hurries across the street to Robbie’s mystery house, we see principally her face.

Ariel Schulman acknowledged that the laptop device adheres to the “rules” of the franchise and the genre while producing, for the first time, conventional close shots of the camera operator. “We were really psyched just to do a shot where the girl’s carrying a laptop, and it’s just filming her. . . It just seemed like a really fun way to carry a camera and film ourself because otherwise there’s no other way to shoot close-ups in a ‘Paranormal’ movie.” Henry Joost adds: “The close-up on a teenaged girl’s face being scared is a horror movie icon. . . . If it’s dark, the only light is from the laptop screen, which is scary. It has all the right ingredients to be in a horror movie.”

Finally, in an innovation parallel to the night-vision footage of part two and the swiveling camera of part three, Paranormal Activity 4 incorporates Xbox Kinect technology. The gadget projects a blast of green dots into the living room, and these can be picked up by night-vision video. One effect is to make Robbie even more ghoulish.

Consistent with the perceptual teasing in earlier films’ extreme long-shots, the Kinect grid also signals the demon’s presence by slight contours, most jolting when the dots shift a little to betray phantom movement. As the earlier entries used powder or dust to track the invisible demon, Paranormal 4 enlists a higher-tech sort of particle. Like the other innovations, it shows that the creators needed not only new situations and plot twists but new variants on their stylistic premises.

Who’s there?

I haven’t yet mentioned one creative problem discovered-footage filmmakers need to confront. Who’s responsible for what we see?

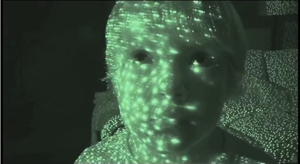

The Paranormal films are obviously assembled. They often have superimposed titles, as above and at the start of the night hauntings. The very first one, at the top of this entry, suggests that something dire will happen to our protagonists; otherwise why ask the families for permission to show the footage?

Editing and camera tricks show the hand of some coordinating intelligence. Some scenes fade out and the night scenes typically start with a fade-in. Locked-down scenes consuming hours are sometimes run fast-forward. We even get dialogue hooks. Randy says, “Just watch the fuckin’ tape, Dennis.” Cut to Dennis watching the tape. In the multiple-camera entries like 2 and 3, there’s cutting from room to room, sometimes following characters through the house. There’s also crosscutting for traditional suspense effects, as when Julie and Dennis are quarrelling while Katie is terrorized by Toby upstairs.

The multiple-camera films betray some perverse humor. We cut from the babysitter Lisa’s terrified retreat from the girls’ room to a shot, about an hour later, of her waiting anxiously by the door for the parents’ return so she can get out as fast as possible.

And sometimes the series of shots is deliberately misleading, dwelling on vacant spaces and failing us to show the characters doing crucial things. Some agent who wanted to convey basic information would provide a more concise set of extracts. This assembler wants to build suspense.

Cloverfield presents itself as a government file, presumably collected and joined by analysts. But Chronicle and The Last Exorcism don’t bother to explain how the recovered footage was discovered, let alone assembled. It’s as if, by this point in the development of the cycle, these marks of authenticity can be omitted.

As usual, the Paranormal series is a bit cagier. With opening titles indicating that the footage is in official hands, the films suggest that these too are from an ongoing investigation of Katie and her family. But I wouldn’t put it past some future installment to center on the unseen collators and editors who have provided us with these shocks and thrills.

In any case, problem-setting and problem-solving remain. The filmmakers have pursued the implications of a narrow set of stylistic choices, and that pursuit comes with both rewards and risks. Meanwhile, other filmmakers may take up the challenge and try to surpass what this series has achieved: limited but genuine experimentation within mainstream conventions. Competing with each other and with their own achievements, filmmakers are pressed to discover new, if narrow, niches in Hollywood’s ecosystem.

E. H. Gombrich’s comment about artists’ tasks comes from his interview with Didier Eribon, Looking for Answers, p. 168. George Watson has some brief but helpful comments on fake memoirs and the discovered-manuscript convention in The Story of the Novel, pp. 15-22. Wikipedia includes a useful list of pseudo-documentaries and discovered-footage here, but calls them “found-footage films,” as most horror aficionados seem to do. As I indicate in the entry, that term confuses these fiction films with what has for a long time been a genre of experimental filmmaking. See for an overview William Wees’ 1993 book Recycled Images: The Art and Politics of Found Footage Films.

On Paranormal Activity, a helpful chronology is available at Dread Central. The chronological collection of the first three films available as a download includes a few extra scenes but omits some things as well, including some of the “official” titles marking the material as recovered footage. In an incisive analysis, Nicholas Rombes praises Paranormal Activity 2 as verging on avant-garde cinema.

Series creator Oren Peli has also directed The Chernobyl Diaries (2012), which has a pseudo-documentary quality at times. More peculiar and puzzling is the film Catfish (2010) by Henry Joost and Ariel Schulman. Many viewers and critics were unsure whether Catfish was a straight documentary or a reenacted one, perhaps with fictional elements added. Whatever the case, it made Joost and Schulman likely candidates for directing the last two installments of the Paranormal franchise. Schulman discusses the transition to studio filmmaking here, while also filling in some background on the Paranormal team’s working methods.

I regret that some of these illustrations are tiny, but I would have had to make them very large for full visibility, and then their quality would have suffered (and the entry would have been even longer). As should be evident, these films need to be seen on a big screen for all their details to be clear.

For a more disconcerting experiment in mechanized camera pickup in a fiction film, see Lars von Trier’s The Boss of It All (2006), discussed here.

Paranormal Activity 2 (2010): On the right, Ali peers in the window as Abby approaches, sniffing.

I Love a Mystery: Extra-credit reading

Thornton Utz illustration for Rex Stout novella from American Magazine, 1951. Obtained from the excellent site Today’s Inspiration.

DB here:

Over the next few months, I’ll be traveling with a talk on Hollywood cinema of the 1940s. The ideas I’ll propose are destined for a book about narrative norms during that period. Mystery fiction is important to that lecture, but I don’t have room there to supply much background about the relevant conventions. So I’m sketching in this background here, for people who might hear the talk somewhere or who might just be curious. Consider this as another experiment on the blog, using the web to supplement a lecture.

Although the lecture is mostly about cinema, this entry is mostly about novels and plays. But I’ll mention film here and there, and you’ll notice that some of the books and plays I mention were adapted for the screen.

A mega-genre

The first half of the twentieth century saw an explosive expansion in genres built around mystery and suspense. The most obvious genre is the detective story. In the wake of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes tales, a great many writers developed and elaborated on the idea of the master sleuth, the genius of observation and reason. Central to this tradition was the puzzle that could be solved by careful noting of clues and meticulous reasoning about them, supplemented by a good knowledge of human nature or local customs. The author needs to keep us in the dark about both the crime and the detective’s chain of reasoning; hence point-of-view figures like Watson, who can be appropriately confounded, relay the detective’s cryptic hints, and marvel at the final revelations.

Readers quickly learned the conventions, so writers had to innovate constantly. Sometimes a writer was original on more than one front. For example, R. Austin Freeman created a revamped Holmes surrogate in a scientific criminologist, Dr. Thorndyke, while also creating a new narrative structure: that of the “inverted” tale. The first section of the story follows the criminal who commits the crime; the second part details how Thorndyke, using evidence and inference, solves it.

Historians of the detective story have a standard account that goes like this. The puzzle-centered plot developed to its apogee in the 1920s and 1930s, chiefly in Britain, and was picked up in the United States. In books like The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (Agatha Christie, 1926), The Canary Murder Case (S. S. Van Dine, 1927), The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (Dorothy L. Sayers, 1928), The Poisoned Chocolates Case (Anthony Berkeley, 1929), The Egyptian Cross Mystery (Ellery Queen, 1932), and The Crooked Hinge (John Dickson Carr, 1938), the crimes are deeply puzzling, even fantastical, and the solutions ever more recherché.

Historians of the detective story have a standard account that goes like this. The puzzle-centered plot developed to its apogee in the 1920s and 1930s, chiefly in Britain, and was picked up in the United States. In books like The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (Agatha Christie, 1926), The Canary Murder Case (S. S. Van Dine, 1927), The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (Dorothy L. Sayers, 1928), The Poisoned Chocolates Case (Anthony Berkeley, 1929), The Egyptian Cross Mystery (Ellery Queen, 1932), and The Crooked Hinge (John Dickson Carr, 1938), the crimes are deeply puzzling, even fantastical, and the solutions ever more recherché.

It’s hard for us to conceive today how massively popular these puzzle books were. Van Dine’s first novels were bestsellers comparable to Jonathan Kellerman’s books today. Just as important, the detective story was granted quasi-literary status. Magazines and newspapers that wouldn’t dream of reviewing romance or adventure fiction devoted space to detective stories, sometimes even setting up separate columns or sections for reviews. It was believed, rightly or wrongly, that whodunits had a more intellectual readership than Westerns or science fiction.

At about the same time, according to the standard account, a counter-current was swelling. In the pulp magazines of the 1920s, the “hard-boiled” detective emerged as an alternative to the master sleuth. The prototype is Dashiell Hammett’s Continental Op in stories through the late 1920s, to be followed by Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon (1930). Strikingly, Hammett and other hard-boiled writers don’t wholly abandon the basic idea of solving a mystery through some sort of reasoning. The differences have to do with realism. The crimes, however, aren’t usually fantastical ones like the Locked-Room problem; the killings tend to be mundane. If the white-glove detective’s only real opponent is a master criminal like Professor Moriarty, the hard-boiled detective faces off against organized crime, or at least people who commit murder outside upper-crust parlors and remote country houses. Clues are less likely to be physical, and more psychological, depending on bits of behavior or flashes of temperament. Raymond Chandler and others took the hard-boiled initiative into the 1940s, and the brute detective, who solves crimes with boldness, insolence, and a pair of fists, occasionally supplemented by torture, found bestseller status in Mickey Spillane’s I, the Jury (1947) and subsequent novels.

I’d argue that some writers could blend the master-mind detective and the tough guy. Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason was one such hybrid, though leaning closer to the hard-boiled model. Rex Stout solved the problem neatly by creating two detectives: the insolent legman Archie Goodwin serves as a hard-boiled Watson to sedentary Nero Wolfe. But on the whole, historians tend to assume that the Holmesian superman and the puzzle-dominated plot were swept aside by the rise of the tough-guy detective solving mysteries that were grittier and more “realistic” than what had preoccupied Golden Age writers.

Two other major developments are typically highlighted by historians. There was the police procedural, perhaps initiated by Lawrence Treat’s V as in Victim (1945), and explored with great ingenuity in the novels of Ed McBain. There was also what Julian Symons has called the “crime novel,” the story of psychological suspense, with Patricia Highsmith’s Strangers on a Train (1950) serving as a good example. Both of these genres have proven popular to this day (CSI as a procedural, the films of De Palma as psychological thrillers).

A tree and its branches

Like most histories hovering fairly far above the ground, the standard account traces some main contours of the landscape but misses some interesting byways. By taking Doyle as the prototype, this account tends to identify mystery fiction with detective plots in the Holmes mold. But mysteries come up in other forms.

The standard account has trouble accommodating the development of the spy genre, which often involves solving a crime, but less through abstract reasoning than by putting the hero through hairbreadth adventures. Think for instance of The 39 Steps, both the 1915 novel and the 1935 film.

More seriously, by identifying solving mysteries with the activities of professional, overwhelmingly male, detectives historians have neglected the powerful and popular tradition of the revived Gothic or “sensation” novel of the mid-nineteenth century. This is typified by Wilkie Collins’ Woman in White (1859-1860) as much as by The Moonstone (1868), often considered the first detective novel (largely because a detective figures as one of the characters, even though he doesn’t solve the mystery). Collins’ novels, along with those of Mary E. Braddock, updated the Gothic format through more complex plotting and multiple points of view. In the next century, Mary Roberts Rinehart, with The Circular Staircase (1908), has to be considered as important as Freeman. Rinehart’s plot introduces the crucial conventions of the mysterious house, the curious and brave woman who explores it, and the threats lurking behind placid domesticity. While the classic white-glove sleuth isn’t usually in much danger, The Circular Staircase and other updated sensation novels make the investigating figure a woman in peril. The sensation novel replaces cool rationality with fear and desperation.

More seriously, by identifying solving mysteries with the activities of professional, overwhelmingly male, detectives historians have neglected the powerful and popular tradition of the revived Gothic or “sensation” novel of the mid-nineteenth century. This is typified by Wilkie Collins’ Woman in White (1859-1860) as much as by The Moonstone (1868), often considered the first detective novel (largely because a detective figures as one of the characters, even though he doesn’t solve the mystery). Collins’ novels, along with those of Mary E. Braddock, updated the Gothic format through more complex plotting and multiple points of view. In the next century, Mary Roberts Rinehart, with The Circular Staircase (1908), has to be considered as important as Freeman. Rinehart’s plot introduces the crucial conventions of the mysterious house, the curious and brave woman who explores it, and the threats lurking behind placid domesticity. While the classic white-glove sleuth isn’t usually in much danger, The Circular Staircase and other updated sensation novels make the investigating figure a woman in peril. The sensation novel replaces cool rationality with fear and desperation.

Jane Eyre is an obvious source for Rinehart and her successors, and perhaps the association with women’s writing in general made historians and practitioners of the Golden Age mock the revived Gothic as too feminine, too far removed from the bluff masculine camaraderie of 221 B Baker Street. The Gothicists had their revenge: Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938) outsold every other mystery novel of its time and sustained a cycle of new sensation novels by Mabel Seeley (The Chuckling Fingers, 1941), Charlotte Armstrong (The Chocolate Cobweb, 1948), and Hilda Lawrence (The Pavilion, 1946). The genre is maintained today by Mary Higgins Clark, Nicci French, and many other writers.

So mystery and detection formed a broader tradition than literary historians sometimes acknowledge. Another marginal form was the suspense thriller. Again, we can point to a woman: Marie Belloc Lowndes, author of The Lodger (1913). An early instance of the serial-killer plot, it’s also a tour de force of point-of-view; unlike the film versions, it restricts itself quite rigorously to what certain secondary characters know. Choices about narration and viewpoint are no less crucial to the thriller than to the Great Detective tradition.

The psychological thriller was revived during the Golden Age, sometimes by practitioners of the puzzle-story. Anthony Berkeley Cox, writing as Anthony Berkeley, noted in The Second Shot (1930):

The psychological thriller was revived during the Golden Age, sometimes by practitioners of the puzzle-story. Anthony Berkeley Cox, writing as Anthony Berkeley, noted in The Second Shot (1930):

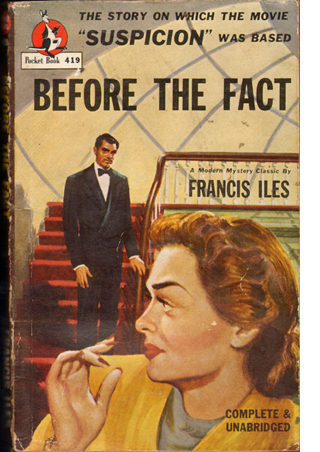

I personally am convinced that the days of the old crime puzzle pure and simple, relying entirely upon plot, and without any added attractions of character, style, or even humour, are, if not numbered, at any rate in the hands of the auditors. . . The puzzle element will no doubt remain, but it will become a puzzle of character rather than apuzzle of time, place, motive, and opportunity. The question will be not “Who killed the old man in the bathroom?” but “What on earth induced X, of all people, to kill the old man in the bathroom?”