Archive for the 'Poetics of cinema' Category

Revisiting Planet Hong Kong

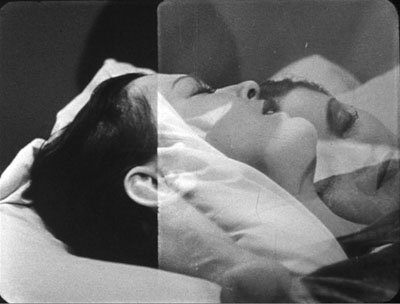

The East Is Red (1993).

DB here:

In about two weeks, we try something new here. It’s an experiment in self-publishing, like everything on this site, but this time we offer a new version of an oldish book.

Planet Hong Kong was published in 2000. It sold pretty well for an academic book, shifting about 7000 copies through 2007. It was translated into Chinese twice, once in Hong Kong and once on the mainland. It also got encouraging reviews; I’ve put up links at the end of this entry.

At some point in 2008, Harvard University Press took the book out of print, a decision I learned about accidentally in spring of 2009. The story is here.

Since then, the book has become rather scarce; only about twenty copies are currently offered on Amazon. Rather than letting the poor thing fade away, I considered revising it for the web. The more I thought about it, the better the prospect looked. I could add as much to the text as I wanted. The text could be corrected, updated, and supplemented in the future. I could add photos, lots of them, and they could be in color. The text would be searchable. And instead of waiting nine to thirteen months to see the result, I could see it in weeks.

Moreover, readers could use the book as they liked. If it was presented as a pdf download, they could read it on a computer or on several models of e-book readers. They could also print out all or part of it. Interestingly, when I asked students and faculty if they’d use the book, nearly all said they’d print it, or let a facility like Kinko’s do it. All in all, it looked like an experiment worth trying.

[Insert montage of fluttering calendar pages here]

God of Gamblers (1989).

Since July I’ve spent virtually all my time on the book, with a break to go to the unmissable Vancouver film fest. Reworking the manuscript, watching and rewatching films, and preparing new material kept me from writing other things I had planned. No blog for Godard’s eightieth birthday, aiming to defend Film Socialisme as an intelligible part of his career. No web entry on the remarkable films of Kon Satoshi, creator of Perfect Blue, Millennium Actress, and The Girl Who Leaped through Time. No discussion of the 1950s-1960s art-cinema canon in the light of Tino Balio’s fine new book on that period in U. S. film culture. No speculations on the psychological processes aroused by a movie’s opening scenes. Maybe next year.

Instead, apart from two quick entries provoked by Inception, I was absorbed in Hong Kong movies on film and DVD, notes from ten years of film festivals and conferences, and plenty of books and websites. Two blog entries, one on coincidence and the other on Jackie Chan’s Police Story, were chips from the workbench. As for my seeing recent releases, The Social Network and Megamind have been about it.

Now, after a month of fourteen-hour days, Planet Hong Kong redux is close to ready. I hope to make it available on this site during the week of 20 December.

The beast has grown in captivity. The first edition ran about 130,000 words; the new version adds 40,000 words. (In defense, I remind you of Adorno explaining why The Authoritarian Personality turned out so long: “We didn’t have enough time to make it short.”) There are over 150 new stills, all in color and many from 35mm prints. But no clips! These films are too beautiful to be reduced to those wretched mutants you get on YouTube. Besides, I don’t have the rights.

Planet Hong Kong 2.0 will not be free. My Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema and Kristin’s Exporting Entertainment are free online, but neither of those was revised, and we absorbed comparatively little of the costs of production. By contrast, the digital PHK is the fruit of a lot of paid labor. Heather Heckman and Mark Minett did excellent scanning and Photoshop tweaking, and Meg Hamel, our web tsarina, designed the book and is making it web-ready. I’m still reckoning the cost of the e-book, but it will be $20 or less. Payment will be rendered unto Caesar, aka Caesar Bordwell, via PayPal.

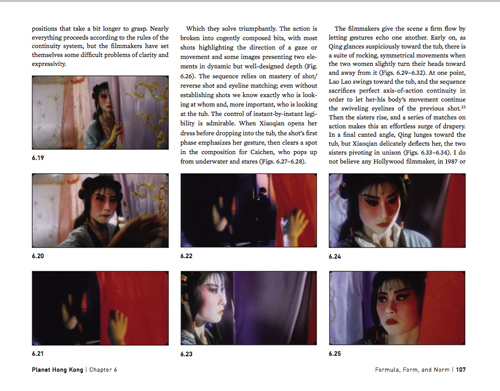

Here’s a sample page from our beta version. I’m still fiddling with the text, but the design looks to me like a nice compromise between the stability of a book page and the flow of a website. The file I’m using here is low-resolution, and this frame from it is a paltry 72 dpi jpeg, but the final pdf page should look very sharp. For curious boffins, the 35mm frame stills were scanned at 2000 dpi and reduced to 300 dpi for insertion. We don’t know yet how big the whole book’s file will be, but of course Meg will optimize it for downloading.

By the way: No, Wong Kar-wai did not invent the luscious image of the yearning woman.

Once the book is up, I plan to add a Hong Kong picture gallery to this site. It will include snapshots of celebs and fans from across the years 1995-2010.

ISNAQs (Infrequently, Sometimes Never, Asked Questions)

Enter the Dragon (1973).

PHK isn’t a comprehensive history of Hong Kong filmmaking; for that you must turn to Stephen Teo’s Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions. Nor is it a fan’s guide to the wild and crazy side of this local cinema. Stefan Hammond’s two books handle that task nicely, and there are many similar handbooks since. Most strikingly, the fanboys have been usurped by the professors. A geyser of academic books and articles about Hong Kong cinema burst in the new millennium, along with invaluable documentation from the Hong Kong Film Archive and the Hong Kong International Film Festival. My book doesn’t rival these.

What does this book do, then?

I try to design my books in layers, with different implications and possibly different readerships, at each level. The first and founding layer of Planet Hong Kong is my effort to convey the sheer pleasure offered by this filmmaking tradition. I write as an enthusiast for other enthusiasts, and for potential converts. In this respect, PHK is an academic dressup of a noble gonzo tradition. Hong Kong cinema has benefited from the gusto of admirers like Ross Chen, Lisa Morton, Stephen Cremin, Grady Hendrix, Stefan Hammond, Chuck Stephens, Richard Corliss, David Chute, Howard Hampton, and other lively writers. This cinema inspires dazzling, sometimes headbanging appreciations from critics.

Next there’s a historical layer. Hong Kong cinema is, I’m convinced, an important “national school” in world film history. It shaped global popular culture to a degree matched only by the westerns and gangster films turned out by the Hollywood studios. Every video game that includes martial arts, every American action movie, and every comic book showing a sword-wielding superhero owe a lot to Bruce Lee and the cinema he springs from. Less obviously, Hong Kong innovated approaches to film form and style that remain striking today. When I wrote the book, this artistic heritage was almost completely unappreciated, by both general audiences and specialized film scholars. The situation is a little better now, but the case always needs restating. Through close analyses of many films and sequences, the book tries to show the originality and force of the Hong Kong touch.

Another layer up, the book asks how popular cinema works. The clichéd split between “art” and “business” isn’t much help in understanding mass-entertainment film. The business relies on artistic traditions, and those traditions in turn are born from and shaped by industrial factors–not just constraints but also enabling opportunities. Hong Kong film provides a case study in how a mass-entertainment movie builds its effects on genre, star appeal, storytelling strategies, and stylistic tactics. It shows vividly how a media industry relies on conventions, and how artists tap those, stretch them, and sometimes twist them out of recognition. My interviews with several writers, directors, choreographers, and actors helped me understand the ways that creativity could be fostered by craft traditions.

At the most general level, PHK is a small-scale demo of an approach to asking questions about cinema. It shows how we might systematically study the principles of construction informing popular filmmmaking. Stealth poetics, in other words.

The old and the new

Leave Me Alone (2004).

The big changes in Asian cinema of the last decade make the original book something of a historical artifact itself. I did the research across the 1990s and wrote nearly all of it in 1998. Its emphases reflect issues circulating in fan and academic culture at that time. DVDs, introduced in 1997, had not become widespread, and VCDs were unwatchable. (Still are.) Most of the films that mattered had to be studied on film copies, although laserdiscs offered a passable backup in some cases. VHS tapes were seldom letterboxed, but laserdiscs often were.

The biggest constraint on the book was the scant availability of Shaw Brothers films on any format. Thanks to the Hong Kong International Film Festival, trips to archives, and the film collector’s market, I was able to see quite a few, but nothing like what’s available now in the massive and restored Shaw DVD library. Consequently, apart from the work of King Hu, Chang Cheh, and Lau Kar-leong, PHK doesn’t deal with the very interesting output of the territory’s most famous company. Fortunately, Shaws has been carefully studied in the years since my book, in a massive volume from the Hong Kong Film Archive and in Poshek Fu’s China Forever: The Shaw Brothers and Diasporic Cinema. For my part, this web essay and these blog entries try to make amends.

I could have recast PHK top to bottom, but I wasn’t convinced that I could come up something as pointed as the original. The text has been corrected, of course, and patches have been recast for greater clarity. It has also been enhanced by a few more examples, film sequences I referred to in passing but could not illustrate because I couldn’t find a print or couldn’t include color images. The chief updating is a series of sections added to the back end.

So here is what the book now looks like.

The first chapter broaches the general idea of an aesthetic of popular cinema. There follows an interlude comparing Hong Kong and Hollywood, focusing on The Untouchables and Gun Men. Instead of launching into a general history of local cinema, Chapter 2 sketches some general features of the territory’s film culture, concentrating on its audiences and its critics. The following interlude,”Two Dragons,” talks about Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, the two most famous Hong Kong heroes. Chapter 3 provides a condensed history of Hong Kong filmmaking up to 1997. The next chapter, “Once Upon a Time in the West,” traces how Hong Kong film attracted fans and festival prestige. There’s an interlude devoted to John Woo, then the fanboys’ demigod.

The first chapter broaches the general idea of an aesthetic of popular cinema. There follows an interlude comparing Hong Kong and Hollywood, focusing on The Untouchables and Gun Men. Instead of launching into a general history of local cinema, Chapter 2 sketches some general features of the territory’s film culture, concentrating on its audiences and its critics. The following interlude,”Two Dragons,” talks about Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, the two most famous Hong Kong heroes. Chapter 3 provides a condensed history of Hong Kong filmmaking up to 1997. The next chapter, “Once Upon a Time in the West,” traces how Hong Kong film attracted fans and festival prestige. There’s an interlude devoted to John Woo, then the fanboys’ demigod.

Chapter 5 surveys the industry, with emphasis on filmmakers’ craft traditions (how stories are planned, scenes are cut, and so on). The interlude that follows takes Tsui Hark as an instance of a director who creatively reworked such traditions. Chapters 6 and 7 go into the most detail about the aesthetics of Hong Kong film, surveying the dynamics of genre, the star system, visual style, and plot construction. Between these two chapters is sandwiched an interlude devoted to Wong Jing, the most disreputable major filmmaker in the territory. The longest chapter, the eighth, explores the distinctive aesthetic of action pictures, from martial arts to contemporary crime movies. The interlude that follows discusses three outstanding directors in the martial-arts tradition: Chang Cheh, Lau Kar-leung, and King Hu. The final chapter of the original book considers how the premises of popular cinema can be adapted to create “art films.” The principal, but not sole, example is the work of Wong Kar-wai. The original book concluded with an analysis of Chungking Express.

The new material in this edition starts with a chapter on changes in the film industry since 1997. That’s followed by an interlude focusing on the Infernal Affairs trilogy, which was as you know the source for The Departed. The next chapter considers how the artistic trends surveyed in the first edition have changed over the last ten years or so. While discussing developments in genre, storytelling, technology, and style, the chapter includes sections on Stephen Chow (particularly Shaolin Soccer and Kung-Fu Hustle), Wong Kar-wai (In the Mood for Love and 2046), and Johnnie To Kei-fung. The final interlude is a more in-depth discussion of To’s crime films and their relation to the indigenous action-movie tradition. At the very end is a new bibliography and endnote citations.

Readers not drawn to Hong Kong cinema might find my more general arguments of interest. For example, I suggest that Hong Kong shows us how important regional and diasporan networks are in creating and maintaining a film culture. To the claim that films reflect their societies, I reply that Hong Kong films suggest a different way to think about such a dynamic, using the model of cultural conversation. Readers interested in fandom should find something intriguing in the story of how cultists around the world helped establish Hong Kong film as a cool thing in the early 1990s. I also argue against the tendency in film studies to assume that when a film tradition doesn’t follow the rules of classical plot construction it must be based on something called “spectacle.” I suggest instead that we need to study principles of episodic plotting, which are probably quite common in popular art generally. In these and other areas, I wanted to use this cinema as a way into thinking about popular moviemaking as a whole.

After World War II, a tailor shop in Hong Kong put up a sign: “Reopening soon. Sooner if possible.” The same goes for me: Planet Hong Kong Redux is coming soon. Sooner if possible.

Here are some reviews of Planet Hong Kong by Richard Corliss in Time Asia (said I typed in my shorts with a beer at my elbow), Paul F. Duke in Variety (liked the book, worried that I talked like a Marxist), an anonymous writer in The Economist (said I’m a scholar who writes as a fan), Steve Erickson in Senses of Cinema (noticed my appreciation of stars), Mina Shin for Framework (developed my suggestions about festival culture), Leon Hunt in Scope (liked book, called me an empiricist, which tickles me down to my sense data), and Shelly Kraicer at chinesecinemas.org (as usual, more generous than he should be).

The most unexpected mention of the book seems to have vanished from the web. A New York critic who is surprisingly easy to outrage made an interesting attempt to charge me with synergistic marketing. He proposed, in the midst of a pan of Tsui Hark’s Time and Tide, that PHK was a covert attempt to promote Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, which had just won acclaim at Cannes. I wrote James Schamus, writer-producer of CTHD: “Now that we’ve been found out, we have to abandon our scheme to reprint my Dreyer book so as to coincide with Ang’s remake of Ordet.”

My quotation from Adorno may be apocryphal.

P.S. 13 December: Thanks to Daniel Erdman, I’ve now got the synergistic review mentioned above. It’s here. Thanks as well to Antti Alanen, who writes from Finland:

About ‘no time to be short’: quite possibly Adorno said so, and you are in good company:

Blaise Pascal: “Je n’ai fait celle-ci plus longue que parce que n’ai pas eu le loisir de la faire plus courte” (The Provincial Letters). J.W. von Goethe: »Da ich keine Zeit habe, dir einen kurzen Brief zu schreiben, schreibe ich dir einen langen« (letter to his sister Cornelia, but Goethe had apparently learned this from Cato and Cicero).

And soon after that came from Antti, Philippe Theophanidis wrote to point out the Pascal source as well. Once more I pay for the lack of a classical education!

Golden Scissors Part I (1963). Famous martial-arts choreographer and director Lau Kar-leung is on the far right. Source: Hong Kong Film Archive.

Once upon some times in Hong Kong

Johnnie To Kei-fung on the set of Running out of Time 2.

DB here:

Exactly nine years ago, Kristin and I were in Hong Kong. Lau Shing-hon, head of the film division of the Academy for Performing Arts, had arranged for me to be Sir Edwin Youde Memorial Fund Visiting Professor. It was a great honor, and Kristin and I enjoyed many happy sessions with Shing-hon, his colleagues, and his students. On this trip, though, something else happened. That lucky encounter has had consequences for my thinking about cinema throughout all the years since.

The encounter was the result of unintended networking. Jeff Smith, now a professor here at Madison, had been my TA in the early 1990s, when I was starting to include Hong Kong films in my courses. He caught the bug. While Jeff was teaching at NYU, a young Taiwanese man, Shan Ding, took some of his courses. Shan, who was naturally as keen on Hong Kong cinema as we were, wound up going to Hong Kong and eventually getting a job with Johnnie To Kei-fung.

So it was during our November 2001 stay that I got a call from a friend, who said that Shan was trying to reach me. Shan wanted to get together, but not in the customary coffee shop or noodle restaurant. He invited Kristin and me to come to a set.

Local heroes

Lifeline.

While doing research for my book Planet Hong Kong in 1996 and 1997, I managed to interview several directors, screenwriters, cinematographers, and action choreographers. Johnnie To was on my list of people to meet because of the cult classics The Big Heat (1988), Heroic Trio (1993), The Executioners (1993), and Loving You (1995). There was also his prestige picture, All about Ah-Long (1989) and an extraordinary movie I saw during one trip to Hong Kong, the firefighter drama Lifeline (1997). At about this time Mr. To was launching his own production company, Milkyway Image.

I keenly wanted to talk with Mr. To, but for various reasons it didn’t prove possible. I submitted my manuscript to the publisher in mid-1998, so I couldn’t incorporate discussion of the three Milkyway masterpieces of that year: Expect the Unexpected, The Longest Nite, and A Hero Never Dies. By the time the book came out in early 2000, there had been three more: Where a Good Man Goes (1999), Running Out of Time (1999), and possibly To’s finest work, The Mission (1999). There I was: the most important director of the late 1990s and early 2000s was largely left out of my book.

Ironically, soon after PHK came out, Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love and Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon triumphed at Cannes. Westerners’ perception of Chinese film changed forever. But in all this fuss, where was Johnnie To?

Making movies, that’s where. He emerged as a heroic figure of local film of the 2000s. True, Infernal Affairs (2002) and Stephen Chow Sing-chi and Wong Kar-wai sustained interest in Hong Kong movies on the international market. But Wong and Chow made films at long intervals, while IA was that rarity in Hong Kong, a “must-see” movie not starring Chow, Jet Li, or Jackie Chan. Johnnie To was just moving ahead, creating romantic comedies, cop dramas, and unclassifiable items like Running on Karma (2003) and Throw Down (2004). Election (2005) and Election 2 (2006) showed, in unprecedented detail, how triad societies governed themselves, and more daringly how they were still connected to mainland China. With his longtime collaborator Wai Ka-fai he went out on a limb with Mad Detective (2007), but on his own he gave us satisfying polars like Exiled (2006) and Triangle (2007) as well as lighter exercises like Sparrow (2008).

Unlike the reclusive Wong Kar-wai and Stephen Chow, To stepped into the public eye. He tried to sustain the local industry by hectoring the government, throwing his weight behind new awards, supporting student film contests. He worried, he has explained, that filmmaking in Hong Kong could collapse the way it did in Taiwan. And he kept surprising us—not least by signing arthouse demigod Jia Zhang-ke to make, of all things, a martial arts movie.

Most of those developments were in the future when we got the call from Shan.

One rainy street

Johnnie To and Shan Ding, Milkyway Image office, 2005.

A van picked us up on a rainy night and we drove far into the New Territories. Along the way Shan was explaining that he was a sort of man-of-all-work for Mr. To. I would see over the years that Shan would assist in scripting and shooting, he might step in front of the camera, and he would help execute ad campaigns. He was sometimes billed as a film’s “Production Supervisor,” which is probably as good a description as any. Because he has fluent English, he was the ideal liaison between Milkyway and the west. Shan played a central role in helping critics and festival programmers learn about Milkyway’s projects.

We arrived at a big abandoned storage facility in a grove of trees. A street set about a block long had been built, bathed in artificial rain and mist. Mr. To was presiding over things.

He greeted us warmly. I had met him briefly at a 1999 Hong Kong film festival event arranged by Athena Tsui and Li Cheuk-to. The festival’s Panorama section paid tribute to Milkyway’s big films of the previous year, and a seminar was held with Wai Ka-fai, Patrick Yau Tat-chi, Lau Ching-wan, and Mr. To.

But by then Planet Hong Kong was in press. Nonetheless, I came to the seminar and took notes. I hoped that some day I would write about this team’s remarkable movies.

That November night Mr. To graciously said he remembered me from the seminar. But he soon went back to work as the crew prepared for what would be a bicycle race. A bicycle race? Who’d be racing? Kristin and I turned, and I gaped. There was Lau Ching-wan.

What Chow Yun-fat was to John Woo, Lau was to To: his exemplary protagonist. Chow was virtually born in a tuxedo, but onscreen Lau projects the image of an ordinary working stiff. In To’s films he usually plays the profane, irritable, unheroic hero; or if the film has no hero, as in The Longest Nite, he becomes a glowering, implacable force.

Not tonight, though. He was as friendly as Mr. To. His English was fine and we chatted a little. For the life of me I can’t recall what we said; I was too, as the Brits say, gobsmacked. I have long known I was a fanboy at heart, but here was the embarrassing proof.

Standing next to him was Ekin Cheng Yee-kin–at that point, one of the leading jeunes premiers of Hong Kong film. He had made his career as a teen idol, particularly in the young-triads cycle known in English as the Young and Dangerous series. He was also extremely cordial.

Both actors had to do a lot of waiting around between shots, of course. While we snacked on food from Styrofoam containers, there was time for pictures. Here’s one of Lau and Cheng flanking Yau Nai-hoi, Mr. To’s prolific screenwriter and later director of Eye in the Sky (2007).

We couldn’t get too close to the main set, but I did get some general shots of the crew at work. The crew filmed take after take of Lau and Cheng pedaling along the same short strip, over and over. I also got some shots of the stunt men, who were trying again and again to knock off some cars’ side mirrors. These guys take some serious spills.

Only when I saw Running Out of Time 2 was it clear that our night’s shoot, and others before and after, yielded a charming scene in which Ekin, the unnamed magician figure, taunts and exasperates Lau as detective Ho. It’s crucial because the race teaches Ho that Ekin’s mysterious cat-and-mouse game is essentially benevolent, even joyful. Staring at the set, I was impressed by how fake it looked. But on film, swathed in darkness, rain, and mist, it looks fine.

Yesterday, re-watching the movie, I enjoyed spotting the moment when we pass from the location to the set. From a shot taken on location, To cuts to a tighter shot of Lau, on the set.

Track in to Lau’s face as we hear a bike bell and Ekin whizzes by.

At Ekin’s urging, Lau grabs a bike and pursues him.

Once you see the film, you can notice how most of the shots are framed to conceal the fact that Lau and Ekin are pedaling down the same stretch over and over, sometimes in reverse directions on the set. Occasionally a changed background sign gives away the repeated takes.

Elaborate as this is set was, it’s still more economical in Hong Kong to mount such a thing than to spend nights on location to get dozens of shots. The magic of the movies, after all. And the signs enable product placement to help cover costs.

Never a man to waste a chance, Mr. To re-dresses the set a bit for Running Out of Time 2‘s cheery epilogue, when Christmas breaks out.

Just as in classical Hollywood cinema, scenes echo one another partly because it’s economical to re-use sets at different points in the movie.

This wasn’t my last encounter with Johnnie To. Shan kept in touch, and my spring visits to Hong Kong included a stopover at Milkyway headquarters. There I would run into Lorenzo Codelli, Shelly Kraicer, Todd Brown of Twitchfilm, Sabrina Baracetti of Udine’s Far East Film Fest, Grady Hendix of the New York Asian Film Festival, and other movers and shakers in film culture. Partly because of To’s promotional outreach to these tastemakers, he is much better known worldwide than he was in 2001. I managed to visit shoots for Throw Down, Exiled, and Triangle. He showed me work-in-progress versions of several films. Mr. To also sat down for interviews with me; my favorite is the one in which he went shot by shot through the “Sukiyaki” scene in A Hero Never Dies. Needless to say, I learned a lot from all these encounters.

These days I’m refurbishing my book for web publication, writing frantically while listening to Cantopop (Sammi and Faye and Gor Gor, mostly). Now I can give Milkyway its due. I’ve spent the last couple of weeks reviewing To’s oeuvre, and I’m more convinced than ever that he is one of the finest directors of the last fifteen years. Planet Hong Kong Redux will contain two lengthy sections on his films. Like all the illustrations in the new version, the stills (many from 35mm prints, not DVDs) will be in color.

As PHK Redux moves closer to online publication in mid-December, I’m mounting other items for the delectation of those discerning souls who know that Hong Kong has created one of the great traditions of film history. This week the site adds my DVD booklet essay on Mad Detective, courtesy Nick Wrigley and Masters of Cinema. And in a couple of weeks, as a run-up to PHK Redux, we’ll be putting up a gallery of celebrity snapshots I’ve taken since my first visit to Hong Kong in 1995.

Secrets

Oh, yes, what were the consequences of this evening in November 2001? Well, one was meeting a new batch of interesting people, Shan and Mr. To and Mrs. To and Martin Chappell and others. Their warm, informal hospitality constitutes one reason I come to Hong Kong every spring.

Another consequence: the conviction that I would have to write more about Hong Kong film. Having followed it since the 1970s, I thought I detected a dropoff in quality and energy in the late 90s. I wasn’t alone. The revised version of my book details how the industry went into a slump then. But the movies from Milkyway showed that you could still flourish in hard times. Seeing Mr. To’s movies made me want to stick with this tradition a little longer. So I continued to write, mostly short pieces about him, until PHK’s going out of print pushed me to update my thinking.

A third consequence of that set visit was broader and deeper. Getting to know filmmakers confirmed that I was a fanboy through and through, but I also felt it shifted me in new directions as a researcher. I’m fascinated by the practice of making movies. I still want to know, within my limited technical expertise, the tangible stuff that people do to build the images and sounds that captivate us. What tools do they use? What work routines have become standardized? What happens when technology or craft practices change?

As a graduate student, I thought that in order to understand movies we just needed to look at the screen. Although I had made some amateur films (bad ones), I failed to see that the fine grain of craft is exactly where artistry begins. By the time I started to write academic essays and books, especially The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I realized that knowing what goes on behind the screen sensitizes you to what’s there. You literally see more.

Most film academics aren’t interested in how craft can nourish artistry. In their eagerness to avoid “formalism,” they tend to neglect artistic traditions, trends, and choices. Movies are made, and the making—poeisis, as the old Greeks called it—demands concrete decisions about form and style. Filmmakers make different choices in different times and places, and we can try to analyze and explain some of those choices. As E. H. Gombrich once suggested, very simply, the artist’s key question is often: “What is there for me to do?” We need not stop there, but considering creative options and decisions is a good place to start if you want to do justice to the films, the filmmakers’ hard work, and the experiences we have as viewers.

I want to know directors’ secrets, especially the ones they don’t know they know. Planet Hong Kong was an effort to bring some of those secrets to light. I think I’ve found some more since then. Thanks to the courtesy of filmmakers like Mr. To, I’m compelled to try sharing them with you.

A fairly recent interview with Johnnie To is here. Especially interesting are his memories of growing up in Kowloon Walled City, a sort of criminal jungle. Corpses on the playground, that sort of thing.

Although the book will pay tribute to them, let me here signal two excellent online resources, now far more elaborated than when I wrote the first version of the book. Ryan Law’s Hong Kong Movie Database is indispensible for investigating people, companies, and films (detailed lists of cast and crew members). HKMDB also has a lively news section. Ross Chen’s vast and entertaining LoveHKFilm lives up to its name, with meaty reviews and news updates. There are many other fine sites, but these are the ones I’ve relied on most often. In addition, I must signal a book that came out too late for me to use; John Charles’ remarkable Hong Kong Filmography 1977-1997.

The friend whom Shan contacted was Li Cheuk-to. Since 1995 Ah-to has been my advisor, translator, editor, and host. I owe him more than I can say.

I have many other people to thank for my times in Hong Kong, and the revised PHK will do so. In the meantime, if you’re interested in Johnnie To and Milkyway, you can check my other blog entries here.

P.S. After I finished this entry there came the sad news of the death of Mr. Wong Tin-lam, a director from the classic era of Cantonese cinema. His Wild, Wild Rose (1960) is still remembered as a trail-blazer. The father of director Wong Jing, he brought a grassroots gravitas to some of the best Milkyway films, in which he was likely to play a Triad elder. Go here for more pictures and background information.

Wong Tin-lam in A Hero Never Dies.

P.P.S., 20 November: Thanks to Yvonne Teh for correcting my spelling! Check her enjoyable Hong Kong site Webs of Significance.

Grandmaster flashback

DB here:

Elsewhere I’ve sung the glories of Turner Classic Movies. Would that the other basic-cable staple, the Fox Movie Channel, were as committed to classic cinema. It’s curious that a studio with a magnificent DVD publishing program (the Ford boxed set, the Murnau/ Borzage one) is so lackluster in its broadcast offerings. Fox was one of the greatest and most distinctive studios, and its vaults harbor many treasures, including glossy program pictures that would still be of interest to historians and fans. Where, for instance, is Caravan (1934), by the émigré director Erik Charell who made The Congress Dances (1931)? Caravan‘s elaborate long takes would be eye candy for Ophuls-besotted cinephiles.

Occasionally, though, the Fox schedulers bring out an unexpected treat, such as the sci-fi musical comedy Just Imagine (1930). Last month, the main attraction for me was The Power and the Glory (1933), directed by William K. Howard from a script by Preston Sturges.

This was an elusive rarity in my salad days. As a teenager I read that it prefigured Citizen Kane, presenting the life of a tycoon in a series of daring flashbacks. I think I first saw it in the late 1960s at a William K. Everson screening at the New School for Social Research. I caught up with it again in 1979, at the Thalia in New York City, on a double bill with The Great McGinty (1940). In my files, along with my scrawls on ring-binder paper, is James Harvey’s brisk program note, which includes lines like this: “One of Sturges’ achievements was to make movies about ordinary people that never ever make us think of the word ‘ordinary.’” I was finally able to look closely at The Power and the Glory while doing research for The Classical Hollywood Cinema (1985). The UCLA archive kindly let me see a 16mm print on a flatbed viewer.

So after a lapse of twenty-eight years I revisited P & G on the Fox channel last month. It does indeed prefigure Kane, but I now realize that for all its innovations it belongs to a rich tradition of flashback movies, and it can be correlated with a shorter-term cycle of them. Rewatching it also teased me to think about flashbacks in general, and to research them a little. You see, I am very fond of what contemporary practitioners like to call broken timelines.

A trick, an old story

On our subject for today, the indispensible book, which ought to be brought back into print or archived online, is Maureen Turim’s Flashbacks in Film: Memory and History (Routledge, 1989). We may think of the flashback as a modern technique, but Turim shows that flashbacks have been a mainstay of filmic storytelling since the 1910s.

On our subject for today, the indispensible book, which ought to be brought back into print or archived online, is Maureen Turim’s Flashbacks in Film: Memory and History (Routledge, 1989). We may think of the flashback as a modern technique, but Turim shows that flashbacks have been a mainstay of filmic storytelling since the 1910s.

Although the term flashback can be found as early as 1916, for some years it had multiple meanings. Some 1920s writers used it to refer to any interruption of one strand of action by another. At a horse race, after a shot of the horses, the film might “flash back” to the crowd watching. (See “Jargon of the Studio,” New York Times for 21 October 1923, X5.) In this sense, the term took on the same meaning as then-current terms like “cut-back” and “switch-back.” There was also the connotation of speed, as “flash” was commonly used to denote any short shot.

But around 1920 we also find the term being used in our modern sense. You can find it in popular fiction; one short story has its female protagonist remembering something “in a confused flashback.” F. Scott Fitzgerald writes in The Beautiful and Damned of 1922:

Anthony had a start of memory, so vivid that before his closed eyes there formed a picture, distinct as a flashback on a screen.

At about the same time writers on theatre start to adopt the term and credit it to film. A historian of drama writes in 1921 of a play that rearranges story order:

The movies had not yet invented the flashback, whereby a thing past may be repeated as a story or a dream in the present.

Within film circles, there were signs of an exasperation with the device. One 1921 writer calls the flashback a “murderous assault on the imagination.” Turim quotes a New York Times review of His Children’s Children (1923):

For once a flash-back, as it is made in this photoplay, is interesting. It was put on to show how the older Kayne came to say his prayers.

In the same year, a critic discusses Elmer Rice’s On Trial, an influential 1911 stage play. Rice employs

a dramatic technique which up to its time was probably unique, though since then the ever recurrent “flash back” of the movies has made the trick an old story.

During the 1930s, although some critics and filmmakers employed older terms like “switch back” and “retrospect,” flashback seems to have become the standard label. It denoted any shot or scene that breaks into present-time action to show us something that happened in the past. It probably speaks to the intuitive and informal nature of filmmaking that writers and directors didn’t feel a need to name a technique that they were using confidently for two decades.

The early flashback films pretty much set the pattern for what would come later. Turim shows that all the sorts we find today have their precedents in the 1910s and 1920s. Adapting her typology a little bit, we can distinguish between character-based flashbacks and “external” ones.

A character-based flashback may be presented as purely subjective, a person’s private memory, as in Letter to Three Wives or The Pawnbroker or Across the Universe. There’s also the flashback that represents one character’s recounting of past events to another character, a sort of visual illustration of what is told. This flashback is often based on testimony in a trial or investigation (Mortal Thoughts, The Usual Suspects), but it may simply involve a conversation, as in Leave Her to Heaven, Titanic, or Slumdog Millionaire. It can also be triggered by a letter or diary, as happens with the doubly-embedded journals in The Prestige.

An alternative is to break with character altogether and present a purely objective or “external” flashback. Here an impersonal narrating authority simply takes us back in time, without justifying the new scene as character memory or as illustration of dialogue. The external flashback is uncommon in classic studio cinema (although see A Man to Remember, 1938) but was common in the 1900s and 1910s and has returned in contemporary cinema. Typically the film begins at a point of crisis before a title appears signaling the shift to an earlier period. Recent examples are Michael Clayton (“Three days earlier”), Iron Man (“36 Hours Before”), and Vantage Point (“23 Minutes Earlier”).

In current movies, flashbacks can fall between these two possibilities. Are the flashbacks in The Good Shepherd the hero’s recollections (cued by him staring blankly into space) or more objective and external, simply juxtaposing his numb, colorless life with the past disintegration of his family? The point would be relevant if we are trying to assess how much self-knowledge he gains across the present-time action of the film.

Rationales for the flashback

What purposes does a flashback fulfill? Why would any storyteller want to arrange events out of chronological order? Structurally, the answers come down to our old friends causality and parallelism.

Most obviously, a flashback can explain why one character acts as she or he does. Classic instances would be Hitchcock’s trauma films like Spellbound and Marnie. A flashback can also provide information about events that were suppressed or obscured; this is the usual function of the climactic flashback in a detective story, filling in the gaps in our knowledge of a crime.

By juxtaposing two incidents or characters, flashbacks can enhance parallels as well. The flashbacks in The Godfather Part II are positioned to highlight the contrasts between Michael Corleone’s plotting and his father’s rise to power in the community. Citizen Kane’s flashbacks are famous for juxtaposing events in the hero’s life to bring out ironies or dramatic contrasts.

Of course, flashbacks need not explain or clarify things; they can make things more complicated too. We tend to think of the “lying flashback” as a modern invention (a certain Hitchcock film has become the prototype), but Turim shows that The Goose Woman (1925) and Footloose Widows (1926) did the same thing, although not with the same surprise effect. Kristin points out to me that an even earlier example is The Confession (1920), in which a witness at a trial supplies two different versions of a killing we have already (sort of) seen.

At the limit, flashbacks can block our ability to understand characters and plot actions. This is perhaps best illustrated by Last Year at Marienbad, but the dynamic is already there in Jean Epstein’s La Glace à trois faces (“The Three-Sided Mirror,” 1927).

I argue in Poetics of Cinema that, at bottom, flashbacks are tactics fulfilling a broader strategy: breaking up the story’s chronological order. You can begin the film at a climactic moment; once the viewers are hooked, they will wait for you to move back to set things up. You can create mystery about an event that the plot has skipped over, then answer the question through a flashback. You can establish parallels between past and present that might not emerge so clearly if the events were presented in 1-2-3 order. Consequently, you can justify the switch in time by setting up characters as recalling the past, or as recounting it to others.

Having a character remember or recount the past might seem to make the flashback more “realistic,” but flashbacks usually violate plausibility. Even “subjective” flashbacks usually present objective (and reliable) information. More oddly, both memory-flashbacks and telling-flashbacks usually show things that the character didn’t, and couldn’t, witness.

I don’t suggest that recollections and recountings are merely alibis for time-juggling. They bring other appeals into the storytelling mix, such as allegiance with characters, pretexts for point-of-view experimentation, and so on. Still, the basic purpose of nonchronological plotting, I think, is to pattern information across the film’s unfolding so as to shape our state of knowledge and our emotional response in particular ways. Scene by scene and moment by moment, flashbacks play a role in pricking our curiosity about what came before, promoting suspense about what will happen next, and enhancing surprise at any moment.

A trend becomes a tradition

When The Power and the Glory was released in August 1933, it was part of a cycle of flashback films. The Trial of Mary Dugan (1929), The Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932), and other courtroom films rendered testimony in flashbacks. A film might also wedge a brief or extended flashback into an ongoing plot. The most influential instance was probably Smilin’ Through (1931), which is notable for using a crane shot through a garden to link present and past.

When The Power and the Glory was released in August 1933, it was part of a cycle of flashback films. The Trial of Mary Dugan (1929), The Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932), and other courtroom films rendered testimony in flashbacks. A film might also wedge a brief or extended flashback into an ongoing plot. The most influential instance was probably Smilin’ Through (1931), which is notable for using a crane shot through a garden to link present and past.

Also well-established was the extended insert model. Here we start with a critical situation that triggers a flashback (either subjective or external), and this occupies most of the movie. Digging around, I found these instances, but I haven’t seen all of them; some don’t apparently survive.

- Behind the Door (1919): An old sea salt recalls life in World War I and, back in the present, punishes the man responsible for his wife’s death. A ripoff of Victor Sjöström’s Terje Vigen (1917)?

- An Old Sweetheart of Mine (1923): A husband goes through a trunk in an attic and finds a memento that reminds him of childhood sweetheart. The pair grow up and marry, facing tribulations. At the end, back in the present, she comes to the attic with their kids.

- His Master’s Voice (1925): Rex the dog is welcomed home from the war. An extended flashback shows his heroic service for the cause, and back in the present he is rewarded with a parade.

- Silence (1926): A condemned man explains the events that led up to the crime. Back in the present, on his way to be executed, he is saved.

- Forever After (1926): On a World War I battlefield, a soldier recalls what brought him there.

- The Woman on Trial (1927): A defendant recalls her past.

- The Last Command (1928): One of the most famous flashback films of the period. An old movie extra recalls his life in service of the tsar.

- Mammy (1930): A bum reflects on the circumstances leading him to a life on the road.

- Such is Life (1931): A ghoulish item. A fiendish scientist confronts a young man with the corpse of the woman he loves. A flashback to their romance ensues.

- The Sin of Madelon Claudet (1931; often cablecast on TCM): A young wife bored with her husband is told the story of a neighbor woman who couldn’t settle down.

- Two Seconds (1932): A man about to be executed remembers, in the two seconds before death, what led him here. A more mainstream reworking of a premise of Paul Fejos’s experimental Last Moment (1928), which is evidently lost.

An interesting variant of this format is Beyond Victory, a 1931 RKO release. The plot presents four soldiers on the battlefield, each one recalling his courtship of the woman he loves back home. The principle of assembling flashbacks from several characters was at this point prised free of the courtroom setting, and multiple-viewpoint flashbacks became important for investigation plots like Affairs of a Gentleman (1934), Through Different Eyes (1942), The Grand Central Murder (1942), and of course Citizen Kane, itself a sort of mystery tale.

Why this burst of flashback movies? It’s a good question for research. One place to look would be literary culture. The technique of flashback goes back to Homer, and it recurs throughout the history of both oral and written narrative. Literary modernism, however, made writers highly conscious of the possibility of scrambling the order of events. From middlebrow items like The Bridge of San Luis Rey (1927) to high-cultural works by Dos Passos and Faulkner, elaborate flashbacks became organizing principles for entire novels. It’s likely that Sturges, a Manhattanite of wide literary culture, was keenly aware of this trend.

It’s just as likely that he noticed similar developments in another medium. By 1931, when Katharine Seymour and J. T. W. Martin published How to Write for Radio (New York: Longmans, Green), they could devote considerable discussion to frame stories and flashbacks in radio drama (pp. 115-137). Especially interesting for Sturges’ film, radio programs were letting the voice of the announcer or the storyteller drift in and out of the action that was taking place in the past.

For whatever reasons, the technique became more common. The year 1933 saw several flashback films besides The Power and the Glory. In the didactic exploitation item Suspicious Mothers, a woman recounts her wayward path to redemption. Mr. Broadway offers an extensive embedded story using footage from another film (a common practice in the earliest days). Terror Aboard begins with the discovery of corpses on a foundering yacht, followed by an extensive flashback tracing what led up the calamity. A borderline case is the what-if movie Turn Back the Clock (1933). Ever-annoying Lee Tracy plays a small businessman run down by a car. Under anesthesia, he reimagines his life as it might have been had he married the girl he once courted. Call it a rough draft for the “hypothetical flashbacks” that Resnais was to exploit in his great La Guerre est finie.

The point of this cascade of titles is that in writing The Power and the Glory, Sturges was working with a set of conventions already in wide circulation. His inventiveness stands out in two respects: the handling of voice-over and the ordering of the flashbacks.

Now I’m about to divulge details of The Power and the Glory.

Narratage, anyone?

The film begins with what became a commonplace opening gesture of film, fiction, and nonfiction biography: the death of the protagonist. We are at the funeral of Thomas Garner, railroad tycoon. His best friend and assistant Henry slips out of the service. After visiting the company office, Henry returns home. Sitting in the parlor with him, his wife castigates Garner as a wicked man. “It’s a good thing he killed himself.” So we have the classic setup of retrospective suspense: We know the outcome but become curious about what led up to it.

Henry’s defense of Garner launches a series of flashbacks. As a boyhood friend, Henry can take us to three stages of the great man’s life: adolescence, young manhood, and late middle age. Scenes from these time periods are linked by returns to the narrating situation, when Henry’s wife will break in with further criticisms of Garner.

Sturges boasted in a letter to his father: “I have invented an entirely new method of telling stories,” explaining that it combines silent film, sound film, and “the storytelling economy and the richness of characterization of a novel.” At the time, the Paramount publicists trumpeted that the film employed a new storytelling technique labeled narratage, a wedding of “narrating” and “montage.” One publicity item called it “the greatest advance in film entertainment since talking pictures were introduced.” Hyperbole aside, what did Sturges have in mind?

There is evidence that some screenwriters were rethinking their craft after the arrival of sound filming. Exhibit A is Tamar Lane’s book, The New Technique of Screen Writing (McGraw-Hill, 1936). Lane suggests that the talking picture’s promise will be fulfilled best by a “composite” construction blending various media. From the stage comes dialogue technique and sharp compression of action building to a strong climax. From the novel comes a sense of spaciousness, the proliferation of characters, a wider time frame, and multiple lines of action. Cinema contributes its own unique qualities as well, such as the control of tempo and a “pictorial charm” (p. 28) unattainable on the stage or page.

Vague as Lane’s proposal is, it suggests a way to think about the development of Hollywood screenwriting at the time. Many critics and theorists believed that the solution to the problem of talkies was to minimize speech; this is still a common conception of how creative directors dealt with sound. But Lane acknowledged that most films would probably rely on dialogue. The task was to find engaging ways to present it. Several films had already explored some possibilities, the most notorious probably being Strange Interlude (1932). In this MGM prestige product, the soliloquys spoken by characters in O’Neill’s play are rendered as subjective voice-over. The result, unfortunately, creates a broken tempo and overstressed acting. A conversation will halt, and through changes of facial expression the performer signals that what we’re now hearing is purely mental.

The Power and the Glory responds to the challenge of making talk interesting in a more innovative way. For one thing, there is the sheer pervasiveness of the voice-over narration. We’re so used to seeing films in which the voice-over commentary weaves in and out of a scene’s dialogue that we forget that this was once a rarity. Most flashback films in the early sound era had used the voice-over to lead into a past scene, but in The Power and the Glory, Henry describes what we see as we see it.

Most daringly, in one scene Henry’s voice-over substitutes for the dialogue entirely. Young Tom and Sally are striding up a mountainside, and he’s summoning up the nerve to propose marriage. What we hear, however, is Henry at once commenting on the action and speaking the lines spoken by the couple, whose voices are never heard.

This scene, often commented upon by critics then and now, seems have exemplified what Sturges late in life recalled “narratage” to be. Describing that technique in his autobiography, he wrote: “The narrator’s, or author’s, voice spoke the dialogue while the actors only moved their lips” (p. 272).

So one of Sturges’ innovations was to use the voice-over not only to link scenes but to comment on the action as it played out. In her pioneering book Invisible Storytellers: Voice-Over Narration in American Fiction Film (Univesity of California Press, 1988), Sarah Kozloff has argued that the pervasiveness of Henry’s narration has no real precedent in Hollywood, and few successors until 1939 (pp. 31-33). (There’s one successor in Sacha Guitry’s Roman d’un tricheur.) The novelty of the device may have led Sturges and Howard toward redundancies that we find a little labored today. The transitions into the past from the frame story are given rather emphatically, with Henry’s voice-over aided by camera movements that drift away from the couple. (Compare the crisp shifts in Midnight Mary, below.) Henry’s comments during the action are sometimes accentuated by diagonal veils that drift briefly over the shot, as if assuring us that this speech isn’t coming from the scene we see.

The “montage” bit of “narratage” also invokes the idea of a series of sequences guided by the voice-over narrator. The concept might also have encompassed the most famous innovation of The Power and the Glory: Sturges’ decision to make Henry’s flashbacks non-chronological.

Even today, most flashback films adhere to 1-2-3 order in presenting their embedded, past-tense action. But Sturges noticed that in real life people often recount events out of order, backing and filling or free-associating. So he organized The Power and the Glory as a series of blocks. Each block contains several scenes from either boyhood, youth, or middle age. Within each block, the scenes proceed chronologically, but the narration skips around among the blocks.

For example, a block of boyhood scenes gives way to a set showing Garner, now in middle age, ordering around his board of directors. The next cluster of flashbacks returns to Garner’s youth and his courtship of his first wife, Sally. Then we are carried back to his middle age, with scenes showing Garner alienated from Sally and his son Tommy but also attracted to the young woman Eve. And from there we return to Garner’s early married life with Eve.

To keep things straight, Sturges respects chronology along another dimension. Not only do the scenes within each block follow normal order, but the plotlines developing across the three phases of Garner’s life are given 1-2-3 treatment. In one block of flashbacks, we see Tom and Sally courting. When we return to that stage of their lives in another block, they are happily married. The next time we see Garner as a young man, he is improving himself by attending college. The later romance with Eve develops in a similar step-by-step fashion across the blocks devoted to middle age.

A major effect of the shuffling of periods is ironic contrast. Maureen Turim points out that seeing different phases of Garner’s life side by side points up changes and disparities. In his youth, Tom watches the birth of his son with awe; in the next scene, we are reminded what a wastrel young Tommy turned out to be.

The juxtaposition of time frames also nuances character development. As Sally ages, she turns into something of a nag, quarreling with her husband and pampering Tommy. But in the next sequence we see her young, ambitiously pushing Tom to succeed and willing to undergo sacrifice by taking up his job as a railroad track-walker. The next scenes show Tom in class and in a bar while Sally walks the desolate tracks in a blizzard. She has given up a lot for her husband. In the next scene, set in middle age, Garner confesses his love to Eve but says he could never leave Sally, and the juxtaposition with Sally’s solitary track-walking suggests that he recognizes her sacrifice. And in the following scene, when Sally comes to Garner’s office, she admits that she has become disagreeable and asks if they couldn’t take a trip to reignite their love. The juxtaposition of scenes has turned a caricatural shrew into a woman who is a more complex mixture of devotion, disenchantment, and self-awareness.

Other characters aren’t given this degree of shading—Tommy is pretty much a wastrel, Eve a vamp—but another married couple deepens the central parallel. Meek Henry is dominated by his wife, but by the end she is chastened by what she learns of Garner’s real motives. Critic Andy Horton, in his helpful introduction to Sturges’ published screenplay, indicates that this couple adds a note of contentment to what is otherwise a pretty sordid melodrama of adultery and quasi-incest.

The innovative flashbacks and voice-overs are an important part of the film’s appeal, but director William K. Howard supplied some craftsmanship of his own. Particularly striking are some silhouette effects, low angles, and deep-focus compositions that underscore the parallels between Sally’s suicide and Garner’s impending death.

The original screenplay suggests that Sturges intended to push his innovations further. About halfway through, he starts to break down the time-blocks. In the script, Sally visits Garner while he’s working on a bridge. The next scene shows their son Tommy already grown and spoiled, being taken back into his father’s good graces. Then the script returns to the bridge, where Sally tells Tom she’s pregnant. The interruption of the bridge scene reminds us of how badly their child turned out.

The script jumps back to the birth of the baby. In the film the birth scene plays out in its entirety, but in the screenplay Sturges cuts it off by the scene (retained in the film) showing Garner’s marriage to Eve. The final moments of the birth scene, when Garner prays (“Thou art the power and the glory”), become in the script the very end of the film. Coming after Tom’s death at the hand of his son, this epilogue is a bitter pill, rendered all the harder to take by providing no return to Henry and his wife.

The greater fragmentation of the second part of the script, along with Garner’s death as a sort of murder-suicide and the failure to return to the narrating frame, is striking. It’s as if Sturges felt he could take more chances, counting on his viewers’ familiarity with current flashback conventions and on his film’s firmly established time-shuttling method. But if, as sources report, Sturges’ script was initially filmed exactly as written, then it seems likely that the film’s June 1933 preview provoked the changes we find in the finished product. “The first half of the picture,” he remarked in a letter, “went magnificently, but the storytelling method was a little too wild for the average audience to grasp and the latter half of the picture went wrong in several spots. We have been busy correcting this and the arguments and conferences have been endless.”

Even the compromised film proved difficult for audiences. Tamar Lane, proponent of the “composite” form suitable for the sound cinema, felt that the “retrospects” in The Power and the Glory were too numerous and protracted. Nonetheless, he praised it for its “radical and original cinema handling” (p.34). That handling rested upon tradition—a tradition that in turn encouraged innovations. Once flashbacks had become solid conventions, Sturges could risk pushing them in fresh directions.

Mary remembers

Finally, two more flashy flashback movies from 1933. Some spoilers.

Midnight Mary (MGM, William Wellman) works a twist on the courtroom template. The defendant Mary Martin is introduced jauntily reading a magazine while the prosecutor demands that the jury find her guilty of murder. This also sets up a nice little motif of shots highlighting Loretta Young’s lustrous eyes. The motif pays off with a soft-focus shot of her in jail just before the climax.

As the opening scene ends, Mary is led to a clerk’s office to wait for the verdict. There’s an automatic dose of suspense (Will she be found guilty?) but there’s also considerable curiosity: Whom has she killed? How was she caught?

These questions won’t be answered for some time. Lounging in the clerk’s office, Mary runs her eye runs across the annual reports filling his shelves. The flashbacks, which comprise most of the film, are introduced as close-ups of the volumes’ spines—1919, 1923, 1926, 1927, and so on up to the present. They serve as neatly motivated equivalents of those clichéd calendar pages that ripple through montage sequences of the 1930s.

The flashbacks are motivated as subjective; Mary doesn’t recount her life to the clerk but simply reviews it in her mind. Unlike the flashbacks in The Power and the Glory, they are chronological and without gaps. Nothing is skipped over to be revealed later. As usual, though, once Mary’s recollections have triggered the rearrangement of story order, the flashbacks are filmed as any ordinary scenes would be, including bits of action that she isn’t present to witness. The film is a good example of using the extended-flashback convention chiefly to delay the resolution of the climactic action. Told in chronological order, Mary’s tale of woe would have had much less suspense.

Transitions between present and past are areas open to innovation, and early sound filmmakers took advantage of them. In Midnight Mary, the long flashback closes with gangsters pounding on the door of Mary’s boudoir; this sound continues across the dissolve to the present, with Mary roused from her reverie by a knock on the clerk’s office door. Earlier, one transition into the past begins with Mary blowing cigarette smoke toward the bound volumes on the shelf.

Dissolve to a close-up of one book as smoke wafts over it, and then to a shot of Mary’s gangster boyfriend blowing cigarette smoke out before he sets up a robbery..

At one point the narration supplies a surprise by abruptly shifting into the present. Once Mary has become a prostitute, she is slumped over a barroom table in sorrow, while her pal Bunny consoles her. In a tight shot, Bunny (Una Merkel, always welcome), leans over and says: “Oh, what’s the diff, Mary? A girl’s gotta live, ain’t she?”

Cut directly to the present, with Mary murmuring: “Not necessarily, Bunny. The jury’s still out on that.”

Mary’s reply casts Bunny’s question about needing to live in a new light, since Mary is facing execution, and the use of the stereotyped phrase, “The jury’s still out,” now with a double meaning, reminds us of the present-tense crisis. It is a more crisp and concise link than the transitions we get in The Power and the Glory. But then, Wellman has no need for continuous voice-over, which gives the Sturges/ Howard film its more measured pace.

Filmmakers were concerned with finding storytelling techniques appropriate to the sound film, and these unpredictable links between sequences became characteristic of the new medium. Similar links had appeared in silent films, but they gained smoothness and extra dimensions of meaning when the images were blended with dialogue or music. For more on transitional hooks, go here.

Nora and narratage

The hooks between scenes are perhaps the least outrageous stretches of The Sin of Nora Moran, a Majestic release that, thanks to a gorgeous restoration and a DVD release, has rightly earned a reputation as the nuttiest B-film of the 1930s.

It is a flashback frenzy, boxes within boxes. A District Attorney tells the governor’s wife to burn the apparently incriminating love letters she’s found. In explaining why, the D. A. introduces a flashback (or is it a cutaway?) to Nora in prison. We then move into Nora’s mind and see her hard life, the low point occurring when she’s raped by a lion tamer.

Now we start shuttling between the D. A. telling us about Nora and Nora remembering, or dreaming up, traumatic events. At some points, characters in her flashbacks tell her that what she’s experiencing is not real. In one hazy sequence, her circus pal Sadie materializes in her cell to remind Nora that she killed a man. (Actually, she didn’t.) At other moments Nora’s flashbacks include moments in which she says that if she does something differently, it will change—it being the outcome of the story. At this point another character will point out that they can’t change the outcome because it has already happened . . . of course, since this is a flashback.

By the end, after the governor has had his own flashback to the end of his affair with Nora and after she appears as a floating head, things have gotten out of hand. The rules, if there are any, keep changing. And the whole farrago is propelled by furious montage sequences built out of footage scavenged from other films.

Publicity and critical response around The Sin of Nora Moran implied that the movie followed the “narratage” method. There was surely some influence. Scenes contain fairly continuous voice-over commentary, and director Phil Goldstone occasionally drops in the diagonal veil used in The Power and the Glory. But on the whole this delirious Poverty Row item falls outside the strict contours of Sturges’ experiment. Nora Moran blurs the line separating flashbacks and fantasy scenes, and it illustrates how easily we can lose track of what time zone we’re in. Watching it, I had a flashback of my own—to Joseph Cornell’s Rose Hobart, another compilation revealing that Hollywood conventions are only a few steps from phantasmagorias.

Unwittingly, Nora Moran’s peculiarities point forward to the flashback’s golden age, the 1940s and early 1950s. Then we got contradictory flashbacks, flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks, flashbacks from the point of view of a corpse (Sunset Boulevard) or an Oscar statuette (Susan Slept Here). Filmmakers knew they had found a good thing, and they weren’t going to let it go.

The original screenplay of The Power and the Glory is included in Andrew Horton, ed., Three More Screenplays by Preston Sturges (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998). Sturges’ reflections from the late 1950s are to be found in Preston Sturges by Preston Sturges: His Life in His Words, ed. Sandy Sturges (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990). The quotations from Sturges’ letters and from publicity about “narratage” can be found in Diane Jacobs, Christmas in July: The Life and Art of Preston Sturges (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 123-129 and James Curtis, Between Flops: A Biography of Preston Sturges (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982), 87.

My citatations of literary uses of the term come from Elliott Field, “A Philistine in Arcady,” The Black Cat 24, 10 (July 1919), 33; Fitzgerald’s The Beautiful and Damned (1922), available here, 433; Samuel A. Eliot, Jr., ed., Little Theater Classics vol. 3 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1921), 120; The Outlook (11 May 1921), 49, available here; review of His Children’s Children, quoted in Turim p. 29; commentary on On Trial, in The New York Times (25 March, 1923), X2.

For more on the history of flashback construction, apart from Maureen Turim’s Flashbacks in Film, see Barry Salt’s Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis, 2nd ed. (London: Starword, 1992), especially 101-102, 139-141. There are discussions of the technique throughout David Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), especially 42-44.

P.S. 15 November 2015: 1940s flashback technique is surveyed in my Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

Do filmmakers deserve the last word?

DB here:

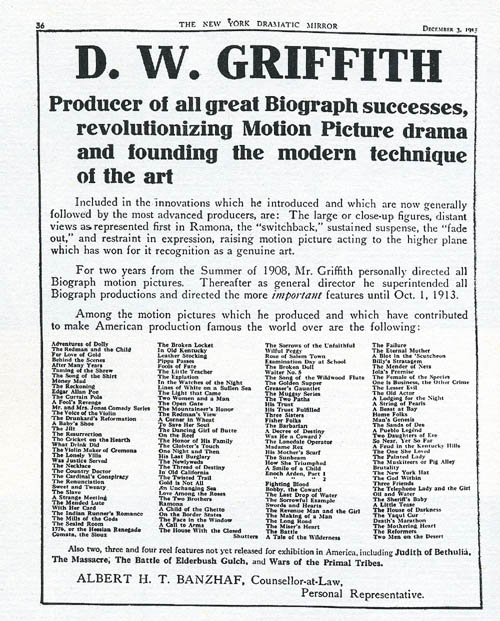

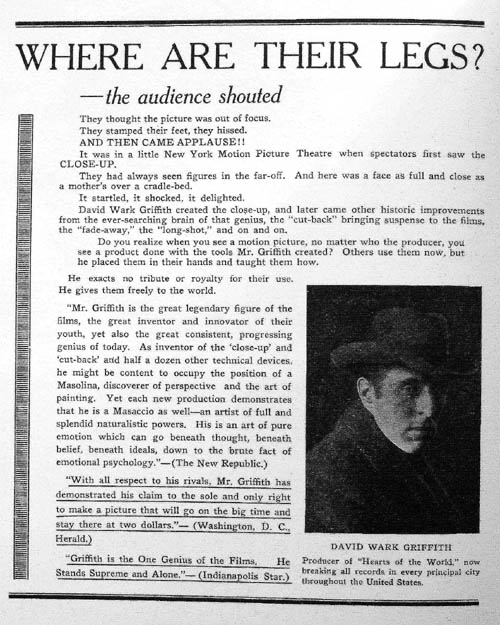

On 3 December 1913, the above advertisement appeared in the New York Dramatic Mirror. D. W. Griffith had left the American Biograph company and set out on an independent path that would lead to The Birth of a Nation and beyond. Because Biograph never credited directors, casts, or crews, he wanted to make sure that the professional community was aware of his contributions. Not only did he point out that he had made several of the most noteworthy Biograph films; he also took credit for new techniques. He introduced, he claims, the close-up, sustained suspense, restrained acting, “distant views” (presumably picturesque long-shots of the action), and the “switchback,” his term for crosscutting—that editing tactic that alternates shots of different actions occurring at the same time.

Griffith’s bid for credit was a shrewd move for his career, and it had repercussions after the stunning success of The Birth of a Nation two years later. Many historians took Griffith at his word and credited him with the breakthroughs he listed. He became known as the father of “film grammar” or “film language.” The idea hung on for decades. Here’s the normally perceptive Dwight Macdonald, criticizing Dreyer’s Gertrud for being anachronistic:

He just sets up his camera and photographs people talking to each other, usually sitting down, just the way it used to be done before Griffith made a few technical innovations. (1)

Filmmakers believed the Griffith story too. Orson Welles wrote of the “founding father” in 1960:

Every filmmaker who has followed him has done just that: followed him. He made the first close-up and moved the first camera. (2)

In the late 1970s a new generation of early-cinema scholars gave us a more nuanced account of Griffith’s place in history. They pointed out that most of the innovations he claimed either predated his Biograph work, (3) or appeared simultaneously and independently in Europe and in other American films. Some Griffith partisans had already conceded this, but they maintained that he was the great synthesizer of these devices, and that he used them with a vigor and vividness that surpassed the sources.

That judgment seems right in part, but Eileen Bowser, Tom Gunning, Barry Salt, Kristin Thompson, Joyce Jesniowski, and other early-cinema researchers have drawn a more complicated picture. (4) Griffith did speed up cutting and devote an unusual number of shots to characters entering and leaving locales. But these innovations weren’t usually recognized as original by previous historians. More interestingly, much of what Griffith did was not taken up by his successors. His technique was idiosyncratic in many respects. By 1915 younger directors like Walsh, Dwan, and DeMille were forging a smoother style that would be more characteristic of mainstream storytelling cinema than Griffith’s somewhat eccentric scene breakdowns. Instead of creating film language, he spoke a forceful but often unique dialect.

The New York Dramatic Mirror ad coaxes me to reflect on how filmmakers have shaped critics’ and historians’ responses to their work. Hawks and Hitchcock developed a repertory of ideas, opinions, and anecdotes to be trotted out on any occasion. Today, directors write books, give interviews, appear on infotainment shows, and provide DVD commentary. We know that many of the talking points are planned as part of the film’s publicity campaign, and journalists dutifully follow the lead. (In Chapter 4 of The Frodo Franchise, Kristin discusses how this happened with Lord of the Rings.) For many decades, in short, filmmakers have been steering critics and viewers toward certain ways of understanding their films. How much should we be bound by the way the filmmaker positions the film?

Deep focus and deep analysis

Citizen Kane (1941).

Determining intentions is tricky, of course. Still, I think that in many cases we can reconstruct a plausible sense of an artist’s purposes on the basis of the artwork, the historical context, surviving evidence, and other information. (5) This may or may not correspond to what the artist says on a particular occasion. For now, I want simply to point to one instance in which filmmakers have shaped critical uptake, with results that are both illuminating and limiting.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, André Bazin, one of the great theorists and critics of cinema, argued that Orson Welles and William Wyler created a sort of revolution in filmmaking. They staged a shot’s action in several planes, some quite close to the camera, and maintained more or less sharp focus in all of them. Bazin claimed that Welles’ Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons and Wyler’s The Little Foxes and The Best Years of Our Lives constituted “a dialectical step forward in film language.”

Their “deep-focus” style, he claimed, produced a more profound realism than had been seen before because they respected the integrity of physical space and time. According to Bazin, traditional cutting breaks the world into bits, a series of close-ups and long shots. But Welles and Wyler give us the world as a seamless whole. The scene unfolds in all its actual duration and depth. Moreover, their style captured the way we see the world; given deep compositions, we must choose what to look at, foreground or background, just as we must choose in reality. Bazin wrote of Wyler:

Thanks to depth of field, at times augmented by action taking place simultaneously on several plane, the viewer is at least given the opportunity in the end to edit the scene himself, to select the aspects of it to which he will attend. (6)

While granting differences between the directors, Bazin said much the same about Welles, whose depth of field “forces the spectator to participate in the meaning of the film by distinguishing the implicit relations” and creates “a psychological realism which brings the spectator back to the real conditions of perception” (7).

In addition, Bazin pointed out, this sort of composition was artistically efficient. The deep shot could supply both a close-up and a long-shot in the same framing—a synthesis of what traditional editing had given in separate shots. Bazin wove all these ideas into a larger theory that cinema was inherently a realistic medium, bound to photographic recording, and Welles and Wyler had discovered one path to artistic expression without violating the medium’s biases.

There are many objections to Bazin’s argument, some of which I’ve rehearsed in On the History of Film Style. My point here is that Bazin was presenting analytical points that stemmed from publicity put out by Welles, Wyler, and especially their talented cinematographer Gregg Toland.

In a 1941 article in American Cinematographer, Toland talked freely about how he sought “realism” in Citizen Kane. The audience must feel it is “looking at reality, rather than merely a movie.” Key to this was avoiding cuts by means of long takes and great depth of field, combining “what would conventionally be made as two separate shots—a close-up and an insert—into a single, non-dollying shot.”(8) Toland defended his sometimes extreme stylistic experimentation on grounds of realism and production efficiency, criteria that carried some weight in his professional community of cinematographers and technicians. (9)

Toland’s campaign for his style addressed the general public too. For Popular Photography he wrote an article (10) explaining again that his “pan-focus” technique captured the conditions of real-life vision, in which everything appears in sharp focus. A still broader audience encountered a Life feature in the same year (11), explaining Toland’s approach with specially-made illustrations. Two samples show selective focus, one focused on the background, the other on the foreground.

An accompanying photo shows pan-focus at work, with Toland in frame center, an actor in the background, and Toland’s camera assistant in the foreground.

In sum, Toland’s publicity prepared viewers, both professional and nonprofessional, for an odd-looking movie.

Throughout the 1940s, Welles and Wyler wrote and gave more interviews, often insisting that their films invited greater participation on the part of spectators. In a crucial 1947 statement, Wyler noted:

Gregg Toland’s remarkable facility for handling background and foreground action has enabled me over a period of six pictures he has photographed to develop a better technique for staging my scenes. For example, I can have action and reaction in the same shot, without having to cut back and forth from individual cuts of the characters. This makes for smooth continuity, an almost effortless flow of the scene, for much more interesting composition in each shot, and lets the spectator look from one to the other character at his own will, do his own cutting. (12)

Some of this publicity material made its way into French translation after the liberation of Paris, just as Kane, The Little Foxes, and other films were arriving too. Bazin and his contemporaries picked up the claims that these films broke the rules. Deep-focus cinematography became, in the hands of critics, a revolutionary new technique. They presented it as their discovery, not something laid out in the films’ publicity.

But the case involved, as Huck Finn might say, some stretchers. Watching the baroque and expressionist Kane, it’s hard to square it with normal notions of realism, and we may suspect Toland of special pleading. Some of Toland’s purported innovations, such as low-angle shots showing ceilings, had been seen before. Even the signature Toland look, with cramped, deep compositions shot from below, can be found across the history of cinema before Kane. Here is a shot from the 1939 Russian film, The Great Citizen, Part 2 by Friedrich Ermler.

More seriously, some of Toland’s accounts of Kane swerve close to deception. For decades people presupposed that dazzling shots like these were made with wide-angle lenses.