Archive for the 'People we like' Category

Stuck inside these four walls: Chamber cinema for a plague year

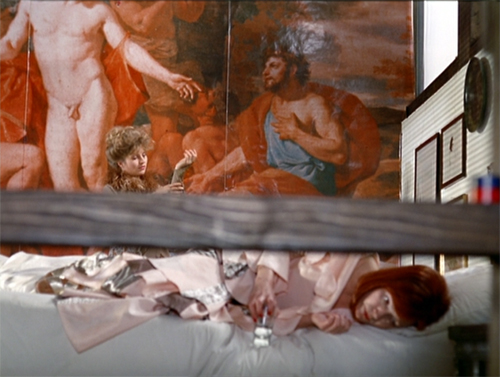

The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972).

Privacy is the seat of Contemplation, though sometimes made the recluse of Tentation… Be you in your Chambers or priuate Closets; be you retired from the eyes of men; thinke how the eyes of God are on you. Doe not say, the walls encompasse mee, darknesse o’re-shadowes mee, the Curtaine of night secures me… doe nothing priuately, which you would not doe publickly. There is no retire from the eyes of God.

Richard Brathwaite, The English Gentlewoman (1631)

DB here:

We’re in the midst of a wondrous national experiment: What will Americans do without sports? Movies come to fill the void, and websites teem with recommendations for lockdown viewing. Among them are movies about pandemics, about personal relationships, and of course about all those vistas, urban or rural, that we can no longer visit in person. (“Craving Wide Open Spaces? Watch a Western.”)

Cinema loves to span spaces. Filmmakers have long celebrated the medium’s power to take us anywhere. So it’s natural, in a time of enforced hermitage, for people to long for Westerns, sword and sandal epics, and other genres that evoke grandeur.

But we’re now forced to pay more attention to more scaled-down surroundings. We’re scrutinizing our rooms and corridors and closets. We’re scrubbing the surfaces we bustle past every day. This new alertness to our immediate surroundings may sensitize us to a kind of cinema turned resolutely inward.

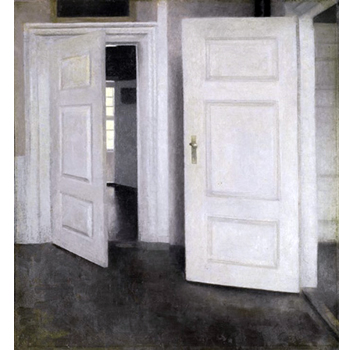

Long ago, when I was writing a book on Carl Dreyer, I was struck by a cross-media tradition that explored what you could express through purified interiors. I called it “chamber art.” In Western painting you can trace it back to Dutch genre works (supremely, Vermeer). It persisted through centuries, notably in Dreyer’s countryman Vilhelm Hammershøi (below).

Plays were often set in single rooms, of course, but the confinement was made especially salient by Strindberg, who even designed an intimate auditorium. For cinema, the major development was the Kammerspielfilm, as exemplified in Hintertreppe (1921), Scherben (1921), Sylvester (1924), and other silent German classics. Kristin and I talk about this trend here and here.

In the book I argued that Dreyer developed a “chamber cinema,” in piecemeal form, in his first features before eventually committing to it in Mikael (1924) and The Master of the House (1925). Two People (1945) is the purest case in the Dreyer oeuvre: A couple faces a crisis in their marriage over the course of a few hours in their apartment. (Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem available with English subtitles.) But you can see, thanks to Criterion, how spatial dynamics formed a powerful premise of his later masterpieces Vampyr (1932), Day of Wrath (1943), Ordet (1955), and Gertrud (1964).

Dreyer wasn’t alone. Ozu tried out the format in That Night’s Wife (1930), swaddling a husband, wife, child, and detective in a clutter of dripping laundry and American movie posters.

Bergman exploited the premise too, in films like Brink of Life (1958), Waiting Women (1952), his 1961-1963 trilogy, and Persona (1966). (All can be streamed on Criterion.)

Chamber cinema became an important, if rare expressive option for many filmmaking traditions. Writers and directors set themselves a crisp problem–how to tell a story under such constraints?

The challenge is finding “infinite riches in a little room.” How? Well, you can exploit the spatial restrictiveness by confining us to what the inhabitants of the space know. Limiting story information can build curiosity, suspense, and surprise. You can also create a kind of mundane superrealism that charges everyday objects with new force.

On the other hand, you need to maintain variety by strategies of drama and stylistic handling. Chamber cinema–wherever it turns up–offers some unique filmic effects, and maybe sheltering in place is a good time to sample it.

Herewith a by no means comprehensive list of some interesting cinematic chamber pieces. For each title, I link to streaming services supplying it.

Bottles of different sizes

From David Koepp I learned that screenwriters call confined-space movies “bottle” plots. There’s a tacit rule: The audience understands that by and large the action won’t stray from a single defined interior. In a commentary track for the “Blowback” episode of the (excellent) TV show Justified, Graham Yost and Ben Cavell discuss how TV series plan an occasional bottle episode, and not just because it affords dramatic concentration. It can save time and money in production.

Usually the bottle consists of more than a single room. The classic Kammerspielfilms roam a bit within a household and sometimes stray outdoors. But their manner of shooting provides a variety of angles that suggest continuing confinement. Dreyer went further in The Master of the House. He built a more or less functioning apartment as the set, then installed wild walls that let him flank the action from any side. Then editing could provide a sense of wraparound space.

The variations in camera setups throughout the film are extraordinary. Dreyer would create more radically fragmentary chamber spaces in La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928), while his later films would use solemn, arcing camera movements to achieve a smoother immersive effect. (For more on Dreyer’s unique spatial experimentation, here’s a link to my Criterion contribution on Master of the House. I talk about the tricks Dreyer plays with chamber space in Vampyr in an “Observations” supplement on the Criterion Channel.)

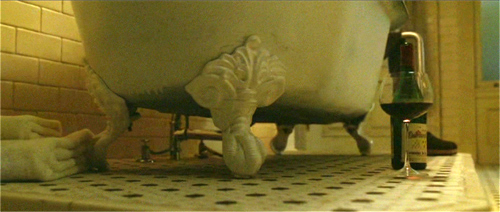

Likewise, Koepp’s screenplay for Panic Room allows David Fincher to move 360 degrees through several areas of a Manhattan brownstone. The film also offers a fine example of how our awareness of domestic details gets sharpened by a creeping camera.

Trust Fincher to find sinister possibilities in a dripping bathtub leg and a kitchen island.

Confined to quarters

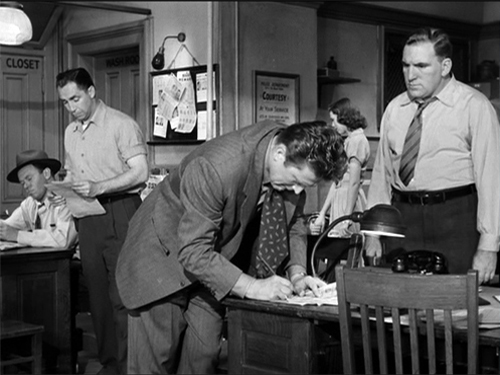

Detective Story (1951).

Many chamber movies are based on plays, as you’d expect. Unlike most adaptations, though, they don’t try to “ventilate” the play by expanding the field of action. Or rather, as André Bazin pointed out, the expansion is itself fairly rigorous. They don’t go as far afield as they might.

Bazin praised Cocteau’s 1948 version of his play Les parents terribles (aka “The Storm Within”) for opening up the stage version only a little, expanding beyond a single room to encompass other areas of the apartment. This retained the claustrophobia, and the sense of theatrical artifice, but it spread action out in a way that suited cinema’s urge to push beyond the frame. The freedom of staging and camera placement is thoroughly “cinematic” within the “theatrical” premise.

Depending on how you count, Hitchcock expanded things a bit in his adaptation of Dial M for Murder. Apart from cutting away to Tony at his club, Hitchcock moved beyond the parlor to the adjacent bedroom, the building’s entryway, and the terrace.

An earlier entry on this site talks about how 3D let Sir Alfred give an ominous accent to props: a particularly large pair of scissors, and a more minor item like the bedside clock.

Hitchcock gave us a parlor and a hallway in Rope (1948), but when Brandon flourishes the murder weapon, the framing audaciously reminds us that we aren’t allowed to go into the kitchen.

Bazin did not wholly admire William Wyler’s Detective Story (1951), despite its skill in editing and performances; he found it too obedient to a mediocre play. True, the film doesn’t creatively transform its source to the degree that Wyler’s earlier adaptation of The Little Foxes (1941) did; Bazin wrote a penetrating analysis of that film’s remarkable turning point. Detective Story is more obedient to the classic unities, confining nearly all of the action to the precinct station. Although I don’t think Wyler ever shows the missing fourth wall, he creates a dazzling array of spatial variants by layering and spreading out zones of the room. In his prime, the man could stage anything fluently.

As Bazin puts it: “One has to admire the unequaled mastery of the mise-en-scène, the extraordinary exactness of its details, the dexterity with which Wyler interweaves the secondary story lines into the main action, sustaining and stressing each without ever losing the thread.”

Some films are even more constrained. 12 Angry Men (1957), adapted from a teleplay, is a famous example. Once the jury leaves the courtroom, the bulk of the film drills down on their deliberation. Again, the director wrings stylistic variations out of the situation; Lumet claims he systematically ran across a spectrum of lens lengths as the drama developed.

But you don’t need a theatrical alibi to draw tight boundaries around the action. Rear Window (1954), adapted from a fairly daring Cornell Woolrich short story, is as rigorous an instance of chamber cinema as Rope. Here Hitchcock firmly anchors us in an apartment, but he uses optical POV to “open out” the private space.

With all its apertures the courtyard view becomes a sinister/comic/melancholy Advent calendar.

Fassbinder’s Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972) denies us this wide vantage point on the outside world. This space seems almost completely enclosed. But Fassbinder finds a remarkable number of ways to vary the set, the camera angles, and the costumes. We’re immersed in the flamboyant flotsam of several women’s lives. The result is a cascade of goofily decadent pictorial splendors.

It’s virtually a convention of these films to include a few shots not tied to the interiors. At the end, we often get a sense of release when finally the characters move outside. That happens in 12 Angry Men, in Panic Room, in Polanski’s Carnage (2011) , and many of my other examples. Without offering too many spoilers, let’s say Room (2015) makes architectural use of this option.

On the road and on the line

Filmmakers have willingly extended the bottle concept to cars. The most famous example is probably Kiarostami’s Ten (2002), which secures each scene in a vehicle and mixes and matches the passengers across episodes. The strictness of Kiarostami’s camera setups exploit the square video frame and always yield angular shot/reverse shots. They reveal how crisp depth relations can be activated through the passing landscape or in story elements that show up in through the window.

Perhaps Kiarstami’s example inspired Danish-Swedish filmmaker Simon Staho. His Day and Night (2004) traces a man visiting key people on the last day of his life, and we are stuck obstinately in the car throughout. This provides some nifty restriction, most radically when we have to peer at action taking place outside.

Staho’s Bang Bang Orangutang (2005), a portrait of a seething racist, takes up the same premise but isn’t quite so rigorous. We do get out a bit, but the camera stays pretty close to the car. I discuss Staho’s films a little in a very old entry.

Like autos, telephones provide a nice motivation for the bottle, as Lucille Fletcher discovered when she wrote the perennial radio hit, “Sorry, Wrong Number.” The plot consists of a series of calls placed by the bedridden woman, who overhears a murder plot. The film wasn’t quite so stringently limited, but the effect is of the protagonist at the center of several crisscrossed intrigues.

A purer case is the Rossellini film Una voce umana (1948), in which a desperate woman frantically talks with her lover. It relies on intense close-ups of its one player, Anna Magnani.

It’s an adaptation of a Cocteau play, which Poulenc turned into a one-act opera. In all, the duration of the story action is the same as the running time.

I wish Larry Cohen’s Phone Booth displayed a similarly obsessive concentration, but we do have the Danish thriller The Guilty, where a police dispatcher gets involved in more than one ongoing crime. We enjoyed seeing it at the 2018 Wisconsin Film Festival.

And of course car and phone can be combined, as they are in Locke (2013)–another play adaptation. Tom Hardy plays a spookily calm businessman driving to a deal while taking calls from his family and his distraught mistress. Those characters remain voices on the line while he tries to contend with the pressures of his mistakes.

House arrest, arresting houses

Sometimes you must embrace the chamber aesthetic. In 2010 the fine Iranian director Jafar Panahi was forbidden to make films and subjected to house arrest. Yet he continued to produce–well, what? This Is Not a Film (2012) was shot partially on a cellphone within (mostly) his apartment.

Wittily, he tapes out a chamber space within his apartment. Then he reads a script to indicate how absent actors could play it and how an imaginary camera could shoot it.

But his imaginary film still isn’t an actual film, so he hasn’t violated the ban. So perhaps what we have is rather a memoir, or a diary, or a home video? Panahi’s virtual film (that isn’t a film) exists within another film that isn’t a film. Yet it played festivals and circulates on disc and streaming. The absurdity, at once touching and pointed, suggests that through playful imagination, the artist can challenge censorship.

Panahi slyly pushed against the boundaries again with Closed Curtain (2013, above). Shot in his beach house, it strays occasionally outside. Next came Taxi (2015), in which Panahi took up the auto-enclosed chamber movie, with largely comic results.

More recently, he has somehow managed to make a more orthodox film, 3 Faces (2018), which considers the situation of people in a remote village.

The chamber-based premise needn’t furnish a whole movie. As in Room, Kurosawa’s High and Low (1963) is tightly concentrated in its first half. We are in two enclosures, a house and a train. The film then bursts out into a rushed, wide-ranging investigation. Large-scale or less, the chamber strategy remains a potent cinematic force.

They say that the last creatures to discover water will be fish. We move through our world taking our niche for granted. Cinema, like the other arts, can refocus our attention on weight and pattern, texture and stubborn objecthood. We can find rich rewards in glimpses, partial views, and little details. Chamber art has an intimacy that’s at once cozy and discomfiting. Seeing familiar things in intensely circumscribed ways can lift up our senses.

So take a break from the crisis and enjoy some art. But return to the world knowing that for Americans this catastrophe is the result of forty years of monstrous, gleeful Republican dismantling of our civil society. Rebuilding such a society will require the elimination of that party, and the career criminal at its head, as a political force. This pandemic must not become our Reichstag fire.

Yeah, I went there.

Thanks to the John Bennett, Pauline Lampert, Lei Lin, Thomas McPherson, Dillon Mitchell, Erica Moulton, Nathan Mulder, Kat Pan, Will Quade, Lance St. Laurent, Anthony Twaurog, David Vanden Bossche, and Zach Zahos. They’re students in my seminar, and they suggested many titles for this blog entry.

Bazin’s comments on Detective Story come in his 1952 Cannes reportage, published as items 1031-1033, and as a review (item 1180), in Écrits complets vol. I, ed. Hervé Joubert-Laurencin (Paris: Macula, 2018), pp. 918-922, 1059. My quotation comes come from the review, where he does grant that Wyler is the Hollywood filmmaker “who knows his craft best. . . . the master of the psychological film.”

The tableau style of the 1910s probably helped shift Dreyer toward the chamber model, which he learned to modify through editing. I discuss Dreyer’s relation to that style in “The Dreyer Generation” on the Danish Film Institute website. Also related is the web essay, “Nordisk and the Tableau Aesthetic.”

Some other examples could be mentioned, but I didn’t find them on streaming services in the US. It would be nifty if you could see the tricks with chamber space in Dangerous Corner (1934); fortunately it plays fairly often on TCM. There’s also Duvivier’s Marie-Octobre (1959), a tense drama about the reunion of old partisans.

I especially like the 1983 Iranian film, The Key, directed by Ebrahim Forouzesh and scripted by Kiarostami. It’s a charming, nearly wordless story of how a little boy tries to manage household crises when Mother is away. It has the gripping suspense that is characteristic of much Iranian cinema, and the boy emerges as resourceful and heroic (though kind of messy). Kids would like it, I think.

Also, I’ve neglected Asian instances. Maybe I’ll revisit this topic after a while.

P.S. 1 April 2020: Thanks to Casper Tybjerg, outstanding Dreyer scholar, for corrections about the nationality of The Guilty and the Staho films.

Gertrud (1964).

Annette Michelson and the Post-Revolutionary Project

The All-Union Creative Conference of Workers in Soviet Cinematography, 1935. First row: V. I. Pudovkin, Sergei Eisenstein, Edward Tissé, and Alexander Dovzhenko. Second row Yuri Raisman, Annette Michelson, et al.

DB here:

Annette Michelson, a pioneering figure in studying cinema, died nearly a year ago, age 95. She enjoyed a distinguished career as an art critic, lecturer, editor, and professor of film. Her influence went beyond her own writings; as an editor she supported now-classic works like P. Adams Sitney’s Visionary Film and the English translation of Noël Burch’s Theory of Film Practice. She was a tireless advocate for contemporary avant-garde filmmakers as well as “difficult” films, from the works of Godard and Vertov to 2001. Upon her retirement, her students and colleagues published a festschrift, Camera Obscura, Camera Lucida: Essays in Honor of Annette Michelson. Many of her essays were collected in a volume called, poetically enough, On the Eve of the Future.

One of Annette’s major accomplishments was co-founding the journal October in 1976. So it’s entirely appropriate that the newest issue is devoted to essays and memoirs celebrating her accomplishments. Edited by Rachel Churner and Malcolm Turvey, it gathers many exceptionally valuable items. It makes available two little-known pieces by Annette: her important essay from 1969, “Art and the Structuralist Perspective,” and a later reflection on Picabia and the cinema. There’s also a wide-ranging conversation with Edward Dimendberg.

One of Annette’s major accomplishments was co-founding the journal October in 1976. So it’s entirely appropriate that the newest issue is devoted to essays and memoirs celebrating her accomplishments. Edited by Rachel Churner and Malcolm Turvey, it gathers many exceptionally valuable items. It makes available two little-known pieces by Annette: her important essay from 1969, “Art and the Structuralist Perspective,” and a later reflection on Picabia and the cinema. There’s also a wide-ranging conversation with Edward Dimendberg.

Yve-Alain Bois analyzes her early, Paris-based art reviews and journalism, including many extracts and printing in toto her very first piece in the New York Herald Tribune. (The first sentence uses one of her favorite words: radical.) There are lengthy tributes from students, colleagues, artists, filmmakers (Gitai, Rainer, Ken Jacobs). Babette Mangolte contributes portraits and some images of Annette’s legendary loft. In all, this is a monumental undertaking and essential for anyone who wants to understand Michelson’s unique stance at the crossroads of film, visual art, critical theory, and Continental philosophy.

The recollections go far toward humanizing a figure who was for many of us a forbidding presence. I met Annette in late 1972, when I interviewed for a job at New York University. She scared me. (I wasn’t alone.) A few years later, when I did a visiting stint there during Noël Carroll’s leave, she proved much less intimidating. Maybe I was less skittish, or she was more mellow. She took a shine to Kristin, and we developed a mutually teasing friendship. I enjoyed her unusual habits, such as playing Berg on her turntable at ear-splitting pitch.

The last time I saw her was in March 2006. She had recently moved from her loft to a new place in midtown, and she was surrounded by boxes of books. Though somewhat frail, she insisted we go out for lunch. We talked about Eisenstein, Godard, and the history of the Anthology Film Archive.

Years before, feeling frisky during a sabbatical, I sent some friends the photo you see above, accompanied by the following text.

From Moscow Weekly (7 November 1993)

INTERACTION OF SOVIET MONTAGE CINEMA AND NEW AMERICAN AVANT-GARDE CONFIRMED BY NEWLY DISCOVERED PHOTO

Glasnost’ has brought many unexpected revelations, but few have been so striking as the proof that there existed an objective relationship between revolutionary Soviet filmmaking and the New York avant-garde cinema of the 1960s.

Until now, a continuity between the experimental Montage directors and the “New American Cinema” of Stan Brakhage and Hollis Frampton seemed an academic flight of fantasy. Many scholars had posited such an affiliation, but hard evidence had been lacking. What could the Marxist cinema of the 1920s have offered the apolitical formalists of the post-Beat generation?

Plenty, it now turns out.

While rummaging in old photographs at Goskino, a young Russian filmmaker, Yevgenii Zhirmunsky, found a crumpled envelope labeled “Conference 1935: Miscellaneous.” The notation referred to the notorious 1935 All-Union Conference of Soviet Cinematography, at which the major directors capitulated to Stalinist demands for Socialist Realism.

Highlight of the Conference was the ritual humiliation of Eisenstein, the most celebrated Soviet director, and the elevation of the Vasilievs’ Chapayev, soon to become the prototype of Socialist Realism.

Zhirmunsky discovered that the envelope held several snapshots of cineastes dozing through papers or denouncing their comrades from the lectern. Most informative, however, was an original version of the famous photo of the premiere directors–Eisenstein, Dovzhenko, Kuleshov, Pudovkin, and others. Zhirmunsky was startled to discover that versions of this photo, reproduced in both East and West for sixty years, had eliminated a key participant at the Conference.

Airbrushing and photomontage were common in the Stalin era. When a political figure fell from favor, he was often deleted from all photographs. Sometimes other figures were added in this Bolshevik version of “virtual reality.”

Now, thanks to Zhirmunsky’s discovery, film scholars know that an influential figure of the New York avant-garde attended the 1935 Conference. Professor Annette Michelson, critic, teacher, and tireless promoter of the New American Cinema, was present and, to judge by the photo, became a central participant in the events taking place.

The photo shows her wearing a loose sweater and blue jeans, characteristic garb of New York bohemians. While a woman seems out of place amid the gabardine-suited directors, Michelson’s intensely serious expression suggests that she followed the debates with keen interest. Her proximity to Eisenstein, and his almost adoring expression, suggests a special affinity between them.

Zhirmunsky surmises that Michelson, long an advocate of the historical continuity of the Soviet avant-garde and the New American film, conveyed to her Manhattan contemporaries the essential insights of the revolutionary directors. This would provide the “missing link” long sought for between the two movements.

Not surprisingly, Michelson has been the most outspoken advocate of the continuity of the two traditions.

Zhirmunsky surmises that Michelson’s “formalism” was anathema to authorities and led to her being deleted from the photo.

The photo is to be published in the US journal October this fall, prefaced by an essay by Zhirmunsky detailing the facts behind his extraordinary discovery.

And he persists in his quest for glasnost’ treasures. “I’ve found some new film footage of the taking of the Winter Palace,” he remarks. “There’s a chap in one shot who seems to be Fredric Jameson.”

My friends assured me that Annette would enjoy it. Apparently she did, because she responded in kind.

Dear Professor David Bordwell,

Professor Annette Michelson asks me, in her present absence from New York, to answer your most kind forwarding to her and to express her profound thanks. I communicated to her your message by telephone last night in California where she was delivering a keynote address at a Maya Deren conference and speaking, as fate would have it, on the Deren-Eisenstein relation.

You can, of course, imagine the extremely great gratification she feels about E. Zhirmunsky’s* discovery. This is a true resurrection that will heal an error and correct a wound maintained for more than a half century! Well, once again, we see that truly Truth is the daughter of Time. Of course you and I know that Professor Michelson, with her usual modesty, rejoices not for herself alone, but for Film History and for all those, who like yourself, labor to its greatest glory.

Professor Michelson found most interesting, of course, your hermeneutics of the original version. She suggested, however, that I communicate to you (although not for publication) her personal interpretation, based, of course, on her living memory of the fateful occasion. You will have noticed that everyone in this picture is smiling or laughing; everyone but Pudovkin, who seems to be explaining something and Professor Michelson (who was , of course at that time, far from being a tenured full Professor, in fact, she had not yet begun the graduate studies from which she … but that is another story).

The reason for this is that Professor Michelson had just challenged the famous director and actor on a point involving the famous debate between himself and Comrade (this is, of course, old style way of speaking) Eisenstein. Perhaps you have some memory of this about building blocks or opposing forces?

Such, it would appear, was the strength of Professor’s challenge coming, in addition to boot, from an American young girl, that the general reaction – even from Donskoi and Bek-Nazarov – was “It appears like the Amerikanska has you, there, Comrade! What have you got to say for yourself now?”

And while Eisenstein is certainly admiring of this daring young female who defends his more correct Hegelian position, he is also clearly amused by Pudovkin’s being flustered by her so that he can hardly defend himself.

For everyone but the two protagonists, the event was a subject of amazement and amusement that lasted far into the Moscow night and beyond, but as you can see from the transcripts of the Conference, it was erased from the record. Perhaps one day, Zhirmunsky or some bold graduate student will turn up the handwritten transcript of this important vis à vis. In the meantime, all heartfelt thanks to you, Professor Bordwell, in Professor Michelson’s name,

Yours sincerely,

R.I. Durakova, Research Assistant, The Post-Revolutionary Project

*Do you have his patronymic, since we would like to write and thank him?

I learned from this that even a sophomoric jape can help cement a friendship. Stuart Liebman, one of her most devoted friends, tells me that Annette continued to enjoy that picture in her final days. Her sense of humor is only one of the many things that make me glad to have known her.

The group portrait is discussed in Annette Michelson, “From Magician to Epistemologist: Vertov’s The Man with a Movie Camera,” reprinted in October (162 (Fall 2017), 113-132. The essay was first published in Artforum in 1972. She notes that Jay Leyda suggested that the photo might have been misdated and was taken later than 1935.

For discussions of Soviet creative retouching of photographs, see David King’s The Commissar Vanishes.

Thanks to Malcolm Turvey for conversations around this issue of October, which also includes an extract from my book Making Meaning.

Doctored photograph of the 1935 group portrait, with Michelson removed and a generic comrade substituted.

Kindest, E.: A memoir of Edward Branigan

Equinox Flower (1958).

DB here (but writing for Kristin too):

Edward Branigan died on Saturday, 29 June, in Bellingham, Washington. He had fought for a year against Acute Myeloid Leukemia. He was 74.

Edward was an ambitious, highly original film theorist. His first book, Point of View in the Cinema (1984) has become the definitive study of the creative POV options available within “classical” filmmaking. Narrative Comprehension and Film (1994) is a sweeping account of the viewer’s activity in ascribing meaning to stories on the screen. Projecting a Camera: Language-Games in Film Theory (2006) is a meta-level account of how critics and theorists talk about films; it teases out different capacities and qualities we assign to “the camera.” Edward’s last book, published in December 2017 is Tracking Color in Cinema and Art: Philosophy and Aesthetics. It ranges across physics, psychology, art history, and philosophy (mostly Wittgenstein) to explore how we understand and appreciate color imagery.

Edward was also a prodigious editor, producing with Warren Buckland The Routledge Encyclopedia of Film Theory (2015) and with Chuck Wolfe the American Film Institute Readers, a series of forty anthologies on a huge range of topics. He taught at UCLA and Iowa, but his tenure home was UC–Santa Barbara, where he started in 1984 and remained until retiring in 2012.

Keeping in touch

Edward and Evan Branigan, 1984.

So much for a bare-bones Wikipedia entry; Edward deserves a full-blown one as soon as possible. What even that couldn’t capture is the intense admiration, even devotion, he aroused in students and colleagues. He won many teaching awards, including a Distinguished Service Award from the graduate students of his department. For his peers in the profession he was a reliably easygoing, cheerful presence in the sometimes chilly corridors of academe.

Kristin and I met Edward in 1974, and we kept up with his life (one far more dramatic than ours) as best we could, separated by half a continent. Over the decades we visited him occasionally in Santa Barbara and Los Angeles. For too-few times he returned to Wisconsin for summer vacations. Our last reunion was in September of 2016 at a Seattle coffee house.

My email records before 2004 have gone astray, but after that I count over 400 messages, some very long. I could fill this entry with remarkable passages, and I expect other correspondents have equally plump archives. From 2007:

John [Kurten] and I have had three consecutive movie binge weekends. it’s a treat to start watching films in the afternoon and never think about stopping (more or less for two days at a time) — isn’t this what the profession promised?

He often wrote to correct mistakes I made in books and essays, so getting this reaction to my In the City of Sylvia entry left me elated. (Fortunately for me, he hadn’t seen the film yet.) One sequence perfectly fulfilled the conditions he laid out in his POV book.

You madman, it’s brilliant. Your latest blog. Maybe the film, too. From what you say, I thought of layers and uncertainties, intersections and random slidings. Open expectation or expectation opened. Is *Sylvia* for the point-of-view shot, i.e. for a point in space, what *The Conversation* was for sound, *Blow-up* for the photograph, *Time Regained* for memory, and etc.?

When I discovered a “Hitchcock supercut” compiling favorite motifs and themes, I was reminded that in the pre-digital era Edward had mounted something similar for his course.

Thanks for this link. . . . I did teach Hitchcock a number of times in the mid-to-late 80’s. My final lecture was exactly and precisely as described on the link you sent. All (almost) of Hitchcock’s films were represented on two Kodak Carousel projectors jammed full. I projected two simultaneous images side by side of visual motifs (staircases, camera movements…etc.). Slow dissolves between each pair of images to the next pair. I made a music tape and keyed certain images to climaxes in the music. Only taught the course in the 80’s. Seems an age ago. Not to mention the changes in technology. I have ten metal cases of slides that are orphans now with no projectors. As do you and Chuck [Wolfe] with many more cases. I had some of my slides digitized, but the quality was disappointing.

But later he reports his house fire:

I have realized that my eight cases of 35mm slides taken directly from 16mm prints — collected since 1974 — are gone in the fire, including a slide from every setup of An Autumn Afternoon.

Speaking of Hitchcock, in 2012 I told him that Sir Alfred would have a place in the book I was planning on the 1940s. This got him going:

Mr. missed D.,

Rethinking Hitchcock! I want to read it. . . . Nice to hear from you generally and I trust you and KT to be well. I suspect the latter has seen The Hobbit many a time so far and planning still more viewings. Nicholas and I are in Seattle. This morning after a large breakfast (omelet, steel-cut oatmeal, hash browns, muffins, black tea) I watched out a tenth floor window as the monorail docked at the Space Needle, while visiting my parents and the other Usual Suspects (i.e., relatives), and planning further hiking, movies, bridge, serious eating, shopping ski apparel activities, and so forth. It’s fairly deeply relaxing here. (It suggests what retirement could be for me in Summer 2014, retirement being in name only at the moment.) I saw two float planes land on Lake Union, taxiing to the shore, water spraying up over the floats, red and green lights continually snapping on and off on both wings (i.e., not one red on the left wing, one green on the right wing). Interstate 5 is in the distance, the car headlights of morning commuter traffic turning it into a winding white snake as the day is strongly grayish, clouds about 40 stories up, swirling, banking up, no sign of sky (thus solar panels are useless), the Olympic Mountains are in the distance, people are walking on the streets below this way and that with purpose, with destinations firmly in mind. Have I mentioned the large rotating, neon pink elephant sign glimpsed in the distance between some buildings that advertises simply, “Car Wash,” as if it doesn’t rain often in Seattle? The sign stops briefly on every rotation to shine out its message in white neon bulbs, “Car Wash,” the message never changing. Up here I’m living in a parenthesis. Looking out at a vast aquarium.

He never forgot my birthday. This is from 2014, as is the photo at the bottom.

HB, big guy. Wherever you are, it’s still HB. Thinking of you.

I’m traveling for a month, meeting many persons, hiking above the treeline in the Rockies, World Lacrosse Championships, Denver, Boulder, Fort Collins, Estes Park, The Stanley Hotel (think The Shining), Seattle, northern Wisconsin, seeing all the sons, and more. Consulting on two legal cases. Have no time. Retirement is the bestest. Even trying to write.

From 2018:

I’ve seen Blade Runner 2049 seven times. A masterwork. Been drinking the Blade Runner Director’s Cut Johnnie Walker Black Label Scotch in the film’s Italian crystal glasses. Watched all sixteen episodes of the Netflix series, Babylon Berlin, in three nights. Should interest you in terms of detective fiction. First-rate fun. Weimar seems like hell with all its circles intact. It’s not up to Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, but what is?

During his cancer treatments, he managed to keep corresponding. Although the paragraphs got shorter, the tone never changed. This from May of this year:

I appreciate your generous words and kind thoughts. I haven’t been feeling well. The blasts have been creeping back. . . . More chemo is likely, maybe a clinical trial. . . .

Enemy. The film streams on Netflix. Take a look. Don’t read anything about it, and its shocks, until it settles on you.

Game of Thrones ends tomorrow for all time until the HBO prequel is ready. I think Dany is killed by Ayra disguised as Tyrion. Jon Snow moves the Iron Throne to Westeros with him upon it.

He inevitably signed these energy bursts, “Kindest, E.”

The 70s: Beyond the New Hollywood

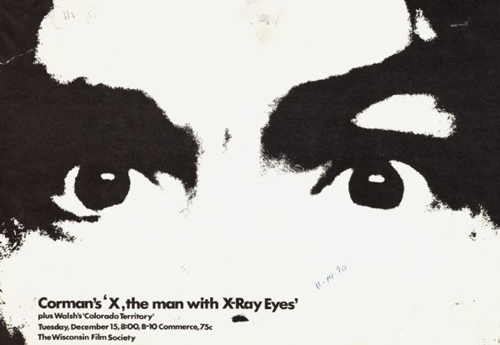

Wisconsin Film Society poster, 1970.

My most vivid memories come from the years we knew him as a student and friend here in Madison. He was part of a thriving intellectual community that, from the distance of today, informed our lives in deep and lasting ways.

Edward, Vietnam veteran (Marines, Communications), took a film course with me in spring 1974, his final year of law school at UW. It was my second semester of full-time teaching. He then signed up for our graduate program. I shouldn’t have been surprised by his shift of career. As an undergraduate he had majored in Electrical Engineering and English. He also wrote poetry.

He entered a community bursting with talent. When I got here in 1973 I was handed four superb TA’s: rigorous and righteous Doug Gomery, witty and charming Brian Rose, meticulous silent-film aficionado Frank Scheide (who looked like a young Buffalo Bill), and already stunning experimental filmmaker James Benning. There was Maureen Turim, fresh from a year in Paris and immersed in Bresson and the avant-garde; Diane Waldman, who’d write the still-definitive account of Hollywood’s female Gothics; Fina Bathrick, who was researching family melodrama before almost anybody else; Marilyn Campbell, the first I think to analyze the Fallen Woman film of the 1930s; Bette Gordon, already at work on her own fine films; and Peter Lehman, already an eloquent advocate for John Ford, Blake Edwards, and Roy Orbison. While everybody else was hot for the new Hollywood, we were into the old one, along with films from beyond the US that later would gain their proper recognition.

Coming in the door were still more gifted grads: Vance Kepley, Janet Staiger, Kerman Eckes, Barb Follick, Barbara Pace, Nancy Ciezki, Diane Kostecke, Mary Beth Haralovich, Cathy Klaprat, Don Kirihara, Darryl Fox, and on and on. I was also establishing ties with young scholars elsewhere: Phil Rosen, Mary Ann Doane, and Bobby Allen at Iowa; Noël Carroll, Paul Arthur, and Tom Gunning at NYU. Networks and enduring friendships were forming. An actual academic field was emerging.

Like every young faculty member, I was learning on the job. I was groping to figure out the problems that interested me most–film form and style, considered in a comparative historical context. The BFI magazine Screen was having a big impact, but so were translations of works by Noël Burch, the Russian Formalists, and French Structuralists. Feminism, neo-Marxism, and Third World politics found their way into our curriculum. Barthes’ S/z became a constant reference point. I went on WORT radio to defend semiotics and The Godfather.

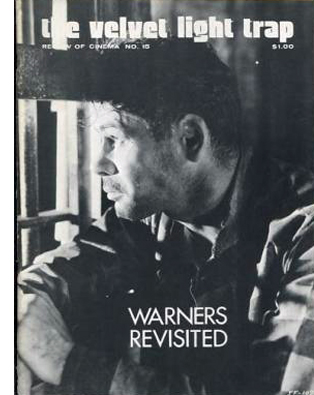

Just as important, American distributors like New Yorker and Audio-Brandon were releasing new European and Latin American titles as well as old works from Asia. In those pre-video days, 16mm prints were our best chance to catch up, not just through classroom showings but through the twenty-plus campus film societies. (There were Sam Fuller double features, but also Godard retrospectives and political documentaries.) And we had The Velvet Light Trap, which published zesty in-depth studies of genres, studios, and auteurs. The campus was movie-mad.

Just as important, American distributors like New Yorker and Audio-Brandon were releasing new European and Latin American titles as well as old works from Asia. In those pre-video days, 16mm prints were our best chance to catch up, not just through classroom showings but through the twenty-plus campus film societies. (There were Sam Fuller double features, but also Godard retrospectives and political documentaries.) And we had The Velvet Light Trap, which published zesty in-depth studies of genres, studios, and auteurs. The campus was movie-mad.

In my seminar on “Classical Hollywood Cinema and Modernist Alternatives,” we analyzed random titles from the Warners and RKO archives alongside Ordet, Equinox Flower, Four Nights of a Dreamer, and Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach. The Student Union screened Play Time in 35 across a whole weekend so my theory class could write essays on it. We brought touring Japanese, French, and Italian film packages to campus.

His Girl Friday, Meet Me in St. Louis, Possessed, Naniwa Elegy, Genroku Chushingura, Tom Tom the Piper’s Son, Death by Hanging, The Man Who Left His Will on Film, The Red and the White, and many other films became touchstones for us. In the midst of all this, senior colleague Tino Balio helped us see how to tie aesthetic analysis to the protocols of national film industries and similar institutions. He became a good friend and ally in many skirmishes, as did Jeannie Thomas Allen, with her work on women and media.

For Kristin and me, the years 1973-1980 crystallized research programs we never left behind. In these years I wrote my Dreyer book, Kristin did her dissertation on Ivan the Terrible, and we published Film Art: An Introduction. With Janet Staiger we began work on what became The Classical Hollywood Cinema. Meanwhile, our students were writing articles for journals and showing up en masse at conferences, a good-natured mafia.

Edward plunged into this and never looked back. He made an offbeat, poetic narrative film (which I hope his family can locate). He ran scenes to and fro on our Steenbecks and analytical projectors, checking match cuts and camera movements. He and Kristin drove down to Chicago for back-to-back screenings of Lancelot du Lac. He began writing on film color, a focus of his research for the next forty years. Above all, we were bound together by Ozu.

Tokyo Story was circulating in 16mm after its smashing New York revival in 1972, and Audio-Brandon and New Yorker acquired several more Ozu titles, early and late. That began our love, or rather mania, for this director. We three watched those prints over and over, eventually writing two essays for Screen in summer of 1976. Edward hoped for a long time to write his doctoral dissertation on An Autumn Afternoon, planning to devote an entire chapter to the woman in the red sweater who passes through scene after scene.

I still want to read that.

Ozu was never far from our thoughts. When Edward finished his dissertation, he gave me a framed still from Equinox Flower. It surmounts this entry. I learned so much from our conversations that I dedicated my Ozu book to him, with a Japanese inscription that means “the pupil who teaches the teacher.” As soon as the book went online, he wrote to tell me of Net problems.

I downloaded the Ozu book. Now, how do I get the color photos and the new crisp b&w’s? Must they be downloaded individually, one at a time? I want them in the book. I want them.

Thanks to his persistent pressure, the University of Michigan created a smoother download.

One constant point of discussion in the 70s was Ozu’s red teakettle in Equinox Flower. When in 2011 Kaurismaki noted it, I sent the link to Edward. He replied:

The red teakettle was a killer for sure. I never really leave the 70s and Vilas Hall… Late nights. 16mm stop motion. I also very much appreciated your blog entry on the four looks at Ozu. Shouldn’t you at some point do a streaming video for your blog?

Sometimes Ozu was merely evoked, not mentioned. One email had this attachment.

Edward knew I would immediately think of a shot from Dragnet Girl and two from Early Summer.

My last email from Edward in May includes this:

Ozu… A year ago I looked at all six of his color films. The color designs are distinctive and sophisticated, but perhaps too complicated to write about. . . .

If he were still with us, I bet he’d try.

Edward’s vitae is available here.

We’re grateful to all those who have shared Edward’s company with us over the years. Vance Kepley helpfully corrected my memory of the 1970s. Thanks especially to Roberta Kimmel and Evan Branigan, who sent us bulletins.

P.S. 9 July 2019: Thanks to Chuck Wolfe, Edward’s tireless colleague at UCSB, for correcting my initial claim about his undergraduate major.

P.S. 12 July 2019: The Film and Media Studies Department at UCSB has posted its tribute to Edward.

Edward Branigan, 1945-2019.

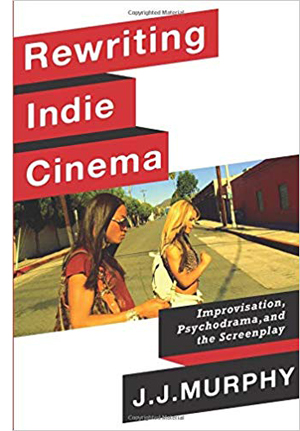

Accident forgiveness: J.J. Murphy’s REWRITING INDIE CINEMA

Maidstone (1970).

DB here:

Did you ever want to beat up Norman Mailer? The impulse must have flitted through the minds of many who paged through his work, saw him on TV, or encountered him swaying pugnaciously at a party. Rip Torn took the opportunity. One day in 1968, he whacked Mailer with a hammer and started to strangle him. As the distinguished author tried to bite off Torn’s ear, Mailer’s wife leaped into the fray and his children shrieked with fear.

This scene, totally unscripted, appears in Mailer’s film Maidstone (1970) and opens J. J. Murphy’s new book Rewriting Indie Cinema: Improvisation, Psychodrama, and the Screenplay. Nothing could better prepare us for his exploration of the traditions–and sometimes jarring consequences–of spontaneous performance in modern American movies.

I couldn’t have predicted that J. J., who was in grad school with Kristin and me, would turn to research. He began as part of the Structural Film movement, achieving wide renown with Print Generation (1974) and (my personal favorite) Sky Blue Water Light Sign (1972). After he was hired here at Wisconsin, he rejuvenated our production program and went on to make independent features: The Night Belongs to the Police (1982), Terminal Disorder (1983), Frame of Mind (1985), and Horicon (1994).

I couldn’t have predicted that J. J., who was in grad school with Kristin and me, would turn to research. He began as part of the Structural Film movement, achieving wide renown with Print Generation (1974) and (my personal favorite) Sky Blue Water Light Sign (1972). After he was hired here at Wisconsin, he rejuvenated our production program and went on to make independent features: The Night Belongs to the Police (1982), Terminal Disorder (1983), Frame of Mind (1985), and Horicon (1994).

At the same time, he was teaching both production and screenwriting. His books reflect his deepening interest in the creative process of making a film outside the Hollywood system. His initial study, Me and You and Memento and Fargo: How Independent Screenplays Work (2007), focused on the principles of screenplay construction that emerged with US indie cinema. Then, in The Black Hole of the Camera: The Films of Andy Warhol (2012), J. J. offered the most complete analysis of this superb body of work. In the process, he opened up a new vein of exploration. The idea of psychodrama proved an exciting way of explaining the fascinating, awkward performances in films like Kitchen (1965), Vinyl (1965), and Bike Boy (1967).

Now the concept of psychodrama gets full play in an ambitious account of the changing role of improvisation in off-Hollywood cinema. What happens, J, J. asks, when filmmakers give up the screenplay? How do they construct a story, define characters, build performances? Rewriting Indie Cinema sweeps from the 1950s to recent films like The Rider and The Florida Project. By looking for alternatives to the fully prepared screenplay, it posits a fresh way of thinking about American film artistry.

Human life isn’t necessarily well-written

Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968).

To start off, J. J. proposes that we think of improvisation in a systematic way. Of course, the concept can be treated broadly. Even Hitchcock, we learn from Bill Krohn, improvised on the set much more than he claimed. But J. J. suggests that improvisation can be considered as a basic creative concept, a founding choice for art-making.

In the 1950s, many American artists began to embrace chance, accident, and personal expression. Abstract Expressionism, bebop, the Judson Dance Theater, Robert Frank’s snapshot aesthetic, and other tendencies valued spontaneity as both authentic self-expression and a challenge to conformist culture. The idea of spontaneity was carried into cinema by Jonas Mekas and fueled what became the New American Cinema of John Cassavetes, Shirley Clarke, and other filmmakers.

But the idea had deeper sources in another trend that J. J. painstakingly brings to light. The Austrian theater director Jacob L. Moreno developed in the 1920s what he called the Theatre of Spontaneity (Das Stegreiftheater). Performances consisted of purely improvised dialogue. When Moreno emigrated to America, he founded “Impromptu Theatre” in the same vein. His 1931 performance at Carnegie Hall was greeted by the New York Times with some disdain:

The first play, like the ones that followed, turned out to be a dab of dialogue uneasily rendered by its hapless players. . . . It became more and more evident that heavy boredom, rather than “forms, moods and visions,” were [sic] the product of the actors. Demanding wit above all else, the Moreno players lacked that essential as fully as the premeditation upon which they frown so heartily. The legitimate theatre, it can be reported this morning, is just about where it was.

Of course improvisation had already proven its worth in vaudeville and in jazz and other musical idioms. Today versions of Moreno’s “spontaneous theatre” flourish in comedy clubs.

Before coming to America, Moreno had discovered that improvisation had therapeautic functions as well. When a couple enacted the frustrations of their marriage, the audience was moved and Moreno was convinced that this “psychodrama” harbored artistic possibilities. Moreno’s wife Zerka called psychodrama “a form of improvisational theatre of your own life.”

J. J. shows Moreno’s pervasive influence on the postwar American scene. Psychodrama became one trend in social psychology, used to help prisoners, narcotics addicts, and even business executives. Woody Allen, Arthur Miller, and other artists were aware of Moreno’s work as well.

Drawing on Moreno but recasting him for film-related purposes, J. J. proposes a spectrum of improvisational options. There’s the completely improvised, ad-lib option, seen in Maidstone and much of Warhol’s work. Here the performers just make it up as they go, though with minimal framing of a situation. Then there’s the possibility of “planned” improvisation, in which there’s a story outline and more or less pre-set scenes. Sean Baker’s Tangerine (2015), for example, was made from a seven-page treatment that included only a couple of lines of dialogue. Then there’s the “rehearsed” option, in which the players collaborate to prepare the scenes and develop the characters, workshop fashion. In production the performers mostly stick to the “script” they’ve created. J. J. points to the films of Cassavetes as a clear case.

Any given film can mix these options, so that some scenes are planned roughly while others are purely ad-lib. And a filmmaker can explore the spectrum across several films, as Joe Swanberg has done.

Where does psychodrama come in? J. J. shows that any of the three points on the improvisation spectrum–pure, planned, and rehearsed–can yield performances that are based in the actual mental states and personal histories of the players. In our Cinematheque screening devoted to his book, Abel Ferrara’s Dangerous Game (1993) served as an example. Harvey Keitel invested his character, an intransigent film director, with the still simmering emotions he felt after his breakup with Lorraine Bracco. Meanwhile Ferrara set up scenes that would provoke Madonna, playing Keitel’s actress, to break character and reveal her immediate responses.

Ferrara wanted to attack Madonna’s celebrity image, and J. J. reads the aftermath to a rape scene in the film being made as projecting the star’s own stammering outrage at having been exploited.

Throughout the book, when improvisation becomes psychodrama, fiction moves closer to documentary. The last chapter examines how certain films considered documentaries, like Robert Greene’s Actress (2014) and James Solomon’s The Witness (2015), cross over into psychodrama from the other side, so to speak.

A detailed study of William Greaves’ Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968) shows how Greaves used psychodramatic techniques to create an even more complicated film-within-a-film than Dangerous Game. Two characters, Freddie and Alice, are played by five different pairs of actors, with all their scenes recorded by a bevy of camera and sound staff.

Greaves also incorporates self-criticism. When crew members object to the script, another participant remarks: “Human life isn’t necessarily well-written, you know.”

Given these conceptual tools, J. J. goes on to trace the production methods employed by a wide range of filmmakers, from Morris Engel in The Little Fugitive (1953) and Cassavetes in Shadows (1959) to Mumblecore and after. Through a mixture of film analysis and background research, he brings to light a vast variety of creative options that can bypass fully-scripted cinema.

Rewriting the unwritten

Paranoid Park (2007).

J. J.’s survey of production methods is embedded in a new historical argument about the shape of off-Hollywood filmmaking. The New American Cinema of the 1950s, which Mekas called “plotless cinema,” was wedded to a sense of realism. But it operated within limits. Cassavetes serves as a benchmark: “I believe in improvising on the basis of the written work and not on undisciplined creativity.” By balancing the planned with the impromptu, his films allowed for the actors to surprise one another. At the same time, Shirley Clarke’s Portrait of Jason (1967) showed how psychodrama could pass easily into documentary, exemplifying Erving Goffman’s theory that everyone is playing theatrical roles in everyday life.

This open approach to screenwriting and screen acting was explored by many filmmakers in the 1960s and a little after: not only the well-known Warhol and Mailer but also Kent Mackenzie, Barbara Loden, William Greaves, and Charles Burnett. J. J. examines all this work in admirable detail. I was especially happy to see that he includes Jonas Mekas’ The Brig (1964), the harrowing film that showed me, in my undergrad days, what the New American Cinema could do in filming a play.

By the time Ferrara made Dangerous Game, most independent filmmaking had moved away from improvisation toward more tightly scripted expression. J.J. traces the institutional pressures operating here. The Sundance Film Festival and PBS’s American Playhouse favored fully-planned projects compatible with the Hollywood standard. The Sundance Institute, launched in 1981, explicitly aimed to correct what was considered the two faults of independent production: screenplays and performances.

The success of polished work like sex, lies, and videotape (1989) and Pulp Fiction (1994) created new norms for American indie cinema. Director-screenwriters like Soderbergh, Tarantino, David Lynch, Hal Hartley, Todd Haynes, the Coens, and Todd Solondz were models for younger filmmakers. As J. J. points out, their screenplays were often published as part of the marketing of the films. Framing the new trend as dominated by the screenplay helped me understand why Bryan Singer, Doug Liman, Karyn Kusama, and other indie filmmakers who came up in the wake of this generation moved so easily to mainstream genres and big-budget projects.

But history plays strange tricks. In the 2000s, filmmakers who felt constrained by the demands of tight scripting began to try something else. J. J. pays special attention to Gus Van Sant, who after proving his commercial craft, made some films with varying degrees of improvisation: Gerry (2002), Elephant (2003), Last Days (2005), and Paranoid Park (2007). Some of the Mumblecore directors relied on screenplays, but the prolific Joe Swanberg adopted a free-form approach, to which J. J. devotes a chapter.

J. J. goes on to survey the work of Sean Baker, the Safdie brothers, Ronald Bronstein, and other directors who have revived the New American Cinema’s impulses in the digital age. He concludes:

Digital technology in effect, democratized the medium, allowing young filmmakers to revive cinematic realism precisely at a time when indie cinema was at risk of losing its identity. In the new century, the use of improvisation and psychodrama provided a sense of continuity with indie cinema’s roots.

J. J. retired from UW–Madison at the end of 2018, and last Saturday night he was honored at our annual screening of student projects. He has been a constant force for good in our department, and we owe him more than we can say. Among those debts is this outstanding contribution to US film studies.

The book’s title carries a double meaning. American independent cinema has been, at crucial periods, “rewritten” by filmmakers who relied on spontaneity rather than a cast-iron screenplay. At the same time, J. J.’s panoramic research in effect rewrites that history. I’m sure that other researchers will build on his wide-ranging arguments, which put the creativity of artists–filmmakers, performers–at the center of our concerns.

J. J.’s books join a cascade of recent work by other colleagues here at Wisconsin. This blog has highlighted Jeff Smith’s Film Criticism, the Cold War and the Blacklist (2014), Kelley Conway’s Agnès Varda (2015), Lea Jacobs’ Film Rhythm after Sound (2015), Lea’s and Ben Brewster’s enhanced e-book of Theatre to Cinema (2016), and Maria Belodubrovskya’s Not According to Plan: Filmmaking under Stalin (2018).

P.S. 9 May 2018: Thanks to Adrian Martin for correction of a misspelled name!

Kelley Conway awards J. J. Murphy a gilded Badger at the Communication Arts Showcase, 4 May 2019.