Archive for the 'People we like' Category

Little stabs at happiness 4: Hitmen, with a side of sukiyaki

A Hero Never Dies (1998).

DB here:

Again, with apologies to Ken Jacobs, I offer another clip that pleases me in this long, hot summer. For earlier installments, go here, here, and here.

Johnnie To Kei-fung has been one of the leading Hong Kong directors since the 1990s. The first edition of my Planet Hong Kong (2000) wasn’t able to incorporate many mentions of his work, but that failing was remedied in my second edition, where he got several pages. Kristin and I first met him in fall of 2001, when Yuin Shan Ding arranged for us to visit the set of Running Out of Time 2. That was a memorable night, with the bike race shot in an elaborate false street wreathed in noirish city vapor.

We spent down time with the stars Ekin Cheng Yee-kin and Lau Ching-wan. It was the beginning of a long friendship with Shan, Mr. and Mrs. To, and the Milkway team.

Well before this, though, I had been teaching Mr. To’s films in my courses, and I much enjoyed showing–on 35mm, no less–A Hero Never Dies (1998). This flamboyant film, about two rival hitmen who unite against the gang bosses who have betrayed them, is a sort of post-John-Woo meditation on the costs of loyalty.

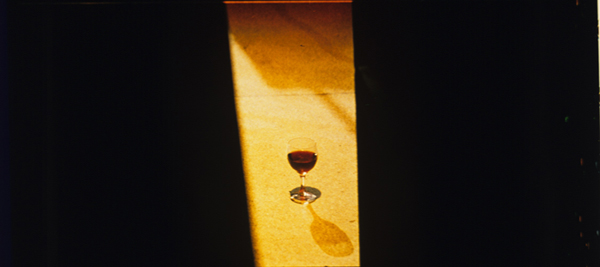

One sequence that usually got the students going was the men’s first up-close confrontation in a bar. Having struck out at each other long-distance, they rendezvous for a face-off–not over guns but over glasses of wine. The clip lacks subtitles, so I should explain that each man instructs the bartender to pour for the other one. Then, after Lau deploys his portion tactically, he refers to Lai’s wrecking his apartment: “This is for destroying my home.” There follows a tabletop action scene.

Shot and cut with great precision, timed to an infectious tune, it’s a model of mock-heroic filmmaking. Its brashness suits its swaggering protagonists, but it has a playground absurdity that evokes Leone. (Think of the hat-blasting gun duel in For a Few Dollars More.) The comedy is enhanced by Lau’s reaction shots and, as Kristin likes to point out, the heaviest coin in Hong Kong. One student told me: “When you’ve got a sequence like this, you’ve got a great national cinema.”

The result yields a pure kinetic pleasure, due partly to the coiling camera movements and the echoing rhythm of the cuts and gestures (ducking out of frame/rising into frame, finger flips/snorting smoke). Mr. To kindly took me through the sequence in an interview, and I learned that it was all shot in one night, after the bar had closed. It wasn’t storyboarded, but by this point Mr. To had all his shots and cuts in his head, and he and the actors developed the sequence as they filmed it.

It takes real pictorial intelligence, I think, to glide between concreteness and abstraction, onscreen and offscreen space, and each man’s optical viewpoint so suavely and zestfully. The camera plays peekaboo with the action.

As for the performances, Mr. To explained that Lau Ching-wan is such an extroverted actor that Leon Lai-ming could counter that bravado best by impassivity, returning his look at key moments. It’s an echo of what Howard Hawks told Montgomery Clift in facing off against John Wayne in Red River. Eventually it all settles into a calm, integrating long shot that declares a truce. What a pleasure to see a scene that actually buttons itself up visually.

And the song? Mr. To told me that the pop version of “Sukiyaki” (on the ambient soundtrack of my own teen years) was often played in theatres as pre-show music. “It always reminds me of movies.”

Thanks to Shan, Mr. and Mrs. To, To Kei-chi, and many other members of the Milkyway team. And to Li Cheuk-to, Athena Tsui, Jacob Wong, Sam Ho, and all the other HKIFF allies over the years. And continued hope for a strong Hong Kong!

We have many blog entries on Johnnie To and Milkyway.

Upper row, left to right: Lau Ching-wan, Yau Na-hoi, Johnnie To Kei-fung; bottom row, Ekin Cheng Yee-kin, DB, KT. Hong Kong, November 2001. Photo: Yuin shan Ding.

Homage to Hong Kong

Yellowing (2014).

DB here:

Since forever, or so it seems, reports in the US media have been dominated by the struggles against the domestic fascism incarnated in the Republican Party and its leader Donald Trump. Every day, we’ve been subject to fusillades of stories about our collapsing economy, the pervasive corruption of the federal government and the judiciary, Trump’s frenzied efforts to whip up his racist supporters, and his failure to contain the coronavirus. In this churn, one world-altering event has gotten little attention: Mainland China’s swift and brutal takeover of the civil society of Hong Kong.

This spring, a new law–one that makes a mockery of lawfulness–was shoved through. Drafted in secret, its provisions were not made public to Hong Kong citizens or representatives before the central authorities in Beijing ratified it. It went into effect on 30 June. A good overview of timeline is on the BBC site.

While claiming to be within the One-Country/Two-Systems provision of the 1997 handover, the bill actually violates that, placing ultimate power in Beijing. The law devotes considerable attention to the purposes of

safeguarding national security; preventing, suppressing and imposing punishment for the offences of secession, subversion, organisation and perpetration of terrorist activities, and collusion with a foreign country or with external elements to endanger national security in relation to the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. . . .

The law goes on to indicate what counts as subversion:

(3) seriously interfering in, disrupting, or undermining the performance of duties and functions in accordance with the law by the body of central power of the People’s Republic of China or the body of power of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region; or (4) attacking or damaging the premises and facilities used by the body of power of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region to perform its duties and functions, rendering it incapable of performing its normal duties and functions.

Obviously street demonstrations could “interfere in” or “disrupt” the activities of the territory’s “body of power”–as it resides in the bureaucracy, the police, and other realms of society. The penalties are severe:

A person who is a principal offender or a person who commits an offence of a grave nature shall be sentenced to life imprisonment or fixed-term imprisonment of not less than ten years; a person who actively participates in the offence shall be sentenced to fixed-term imprisonment of not less than three years but not more than ten years; and other participants shall be sentenced to fixed-term imprisonment of not more than three years, short-term detention or restriction.

The Economist explains:

The bill could result in far more serious charges being laid against protesters should they engage in activities that were common during the recent upheaval. Vandalising public transport could now be treated as terrorism. Breaking into the legislature or throwing eggs at the central government’s liaison office, as demonstrators did last year, could be considered subversive. Calling for Hong Kong’s independence, as some protesters have, could invoke a charge of secession. Encouraging foreign countries to impose sanctions on China could result in prosecution for collusion. The maximum sentence for all four of these categories of crime is life in prison.

How tightly will these provisions be enforced? The answer comes in a story in today’s New York Times. The day after the bill was enacted, a man was arrested for flying the Hong Kong flag during a demonstration. Police also arrested a 15-year-old girl for “inciting subversion” and a young man who carried in his bag a banner urging Hong Kong independence.

Other provisions lay out punishment for “terrorist activities” and, not least, “collusion with a foreign country or with external elements to endanger national security.” Possible offenders include international companies or non-governmental agencies that

provoke by unlawful means hatred among Hong Kong residents towards the Central People’s Government or the Government of the Region, which is likely to cause serious consequences.

A firm that participated in sanctions against China, or an NGO objecting to human-rights treatment could be charged with “fostering hatred.” The boundary between “lawful” and “unlawful” provocations will be left up to administrators such as the Secretary of Justice.

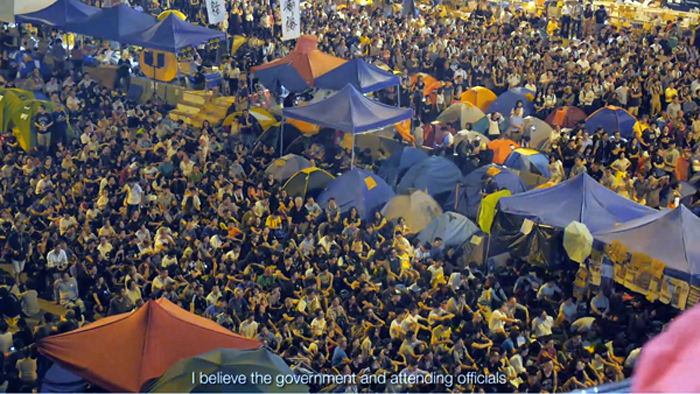

Hong Kongers saw clearly what might come. Such films as Yellowing and Ten Years foresaw just these strictures on free speech and free thought. Thanks partly to the 2014 Umbrella Movement, and the recent effort to pass a “Fugitive Offenders” bill, Hong Kongers’ support for an open society has been peaking. That surge was expressed last fall not only in more rounds of street activism but in the election of democratic representatives to 90 per cent of district seats.

Like Trumpists, Hong Kong’s business interests treat the behavior of the stock market as an index of prosperity. And it’s true that the market has bumped up at the prospect of “stability” under the new law. Yet, as in the US, this has proven a weak indicator. In 2013, the markets crashed and China had to inject money and conceal the sources of the failure.

During my first visit in 1995, a Dutch businessman who was already planning to take his gains and depart told me that in twenty years Hong Kong would be “just another city on the China coast.” He foresaw the mainland’s plan to build up Shanghai, to shrink Hong Kong as a business center, and to gut its quasi-democracy.

In the runup to 1997, Britain could have offered passports to all its former subjects, if only as a gesture to restrain Beijing’s hand. But of course that would have meant Margaret Thatcher acknowledging that there was something called “society,” which she explicitly denied. (That is, we owe no collective obligations to one another.) Now, in an encouraging sign some three million “overseas nationals” (i.e. Hong Kongers born before 1997) may be allowed to emigrate to the UK and seek citizenship there. As for the US, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Congress have proposed measures to retaliate against Chinese officials. Given Trump’s fear of offending Xi, I would not bank on his supporting the effort.

In all, the Dutchman’s prediction was off only in its timing. China has squeezed Hong Kong ever since the takeover, but its citizens–long and mistakenly thought of as indifferent to politics–have fought back with shining commitment. They are as much a vessel of strategic, patient political energy as the Black Lives Matter and Me Too movements.

My heart goes out to my friends in Hong Kong, and all their fellow citizens. They have been, and I expect will continue to be, a model of tenacity and resilience for the rest of us. We are all Hong Kong now. We face new authoritarian policies emerging, it seems, in every news cycle.

P. S. 6 July 2020: Yvonne Teh’s Webs of Significance blogsite offers a wealth of commentary on the changing culture and politics of Hong Kong. See especially her thoughts about Evans Chan’s latest film We Have Boots.

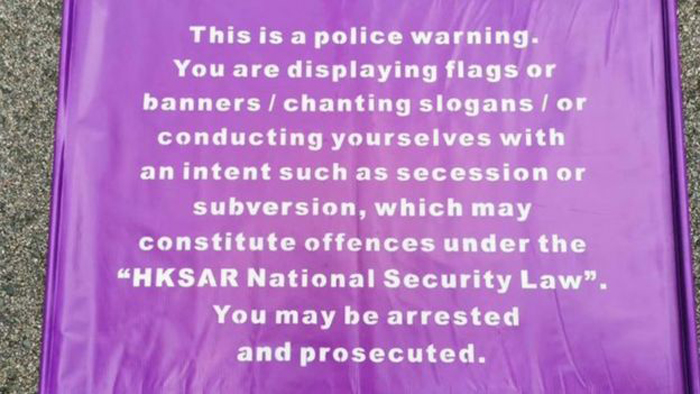

P.P.S. 6 July 2020: I should have included this photo (from Lam Yik Fei of the Times) as a sign of tenacity and resilience. HK demonstrators hold up blank signs. When will the PRC declare a blank piece of cardboard to bear “an intent such as secession or subversion”?

P.P.P.S. 13 July: Well, my answer came fast. The police are indeed arresting people for holding up blank sheets of paper. From the Los Angeles Times:

Hundreds of people have been arrested for unlawful assembly since the law came into effect, some charged with violations including carrying items bearing protest slogans and Bible verses. No one knows what is safe. Even the word “conscience” printed on a sticker can get you into trouble in an atmosphere that is scary and increasingly surreal.

The first blank-paper protester on July 1 was a young woman who told reporters she held up white paper because she wasn’t sure what would be illegal under the new law.

She had remembered a joke she’d read from the Soviet Union: an officer once arrested a person handing out fliers on Red Square, only to find that the fliers were blank. Undeterred, the officer shouted: “You don’t think I know what you wanted to write?”. . . .

Cartoonists drew protesters with empty speech bubbles, made emoji versions of their slogans and wrote out the tune to “Glory to Hong Kong” in numbers signifying the notes. A new graffiti theme appeared across the city: eight blank squares, each one holding space for a slogan whose absence seemed to speak out loud.

Two days after the white-paper protest, one of the arrested women was photographed walking out of the police station. She had been charged with illegal assembly and obstruction of police, according to local news reports.

She paused, her belongings slung over each shoulder, her eyes steady between a face mask and cap, and raised the blank paper once again.

A banner carried by Hong Kong police facing demonstrators “conducting themselves with an intent such as secession or subversion.”

Nero, Archie, and me: Preface to a new web essay

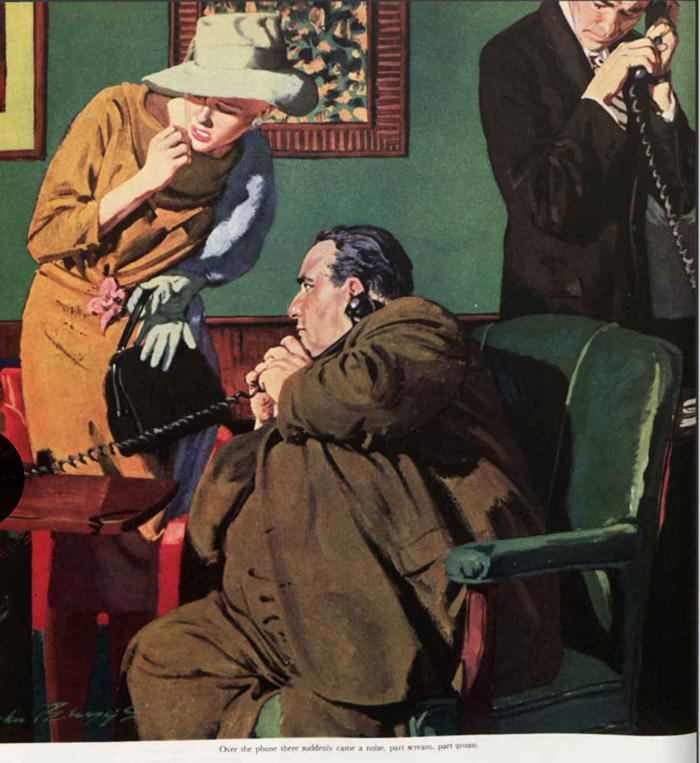

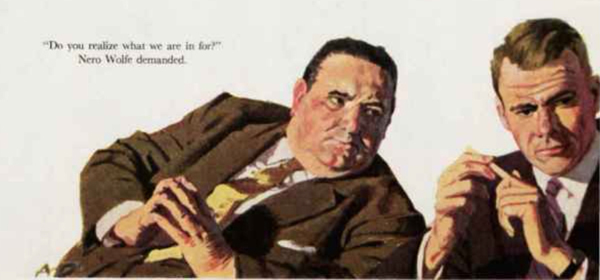

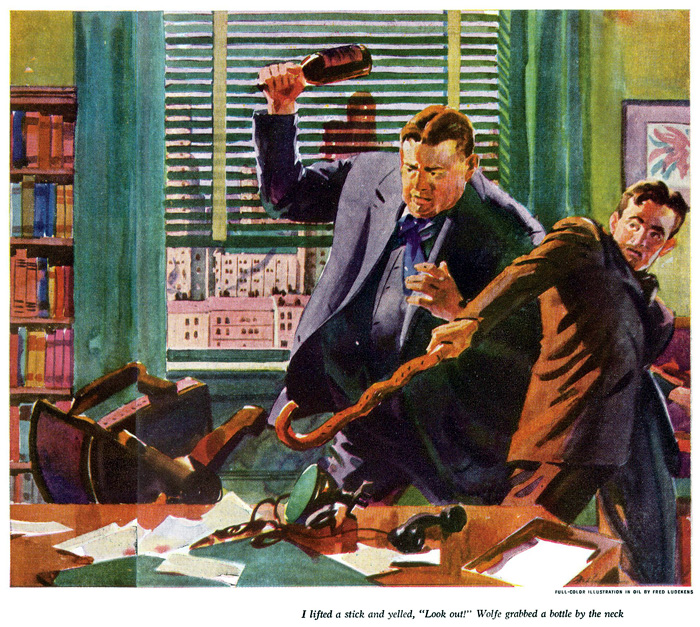

“Frame-Up for Murder” (“Murder Is No Joke”), Saturday Evening Post (21 June 1958).

DB here:

“It is impossible to say which is the more interesting and admirable of the two.” Thus Jacques Barzun on Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin, the characters created by Rex Stout. I’d go farther. For me they are among the outstanding figures of American fiction, and Stout is one of the finest American writers of the twentieth century.

Wolfe and Archie are detectives, and Stout wrote mystery fiction. But that just goes to prove that genre work isn’t just good “of its kind.” It’s often good, period.

Stout started as a pulp novelist. He moved to what we now call literary fiction before pursuing a variety of more mainstream genres. He wrote quasi-experimental novels (one is told backward), comic romances, lost-world sagas, and a political thriller, The President Vanishes. (Stout admitted that Wellman’s film version was better than the book.) He introduced several other detective protagonists, but he wisely concentrated on Wolfe and Archie, whom he launched in 1934 and traced through dozens of adventures until his death in 1975.

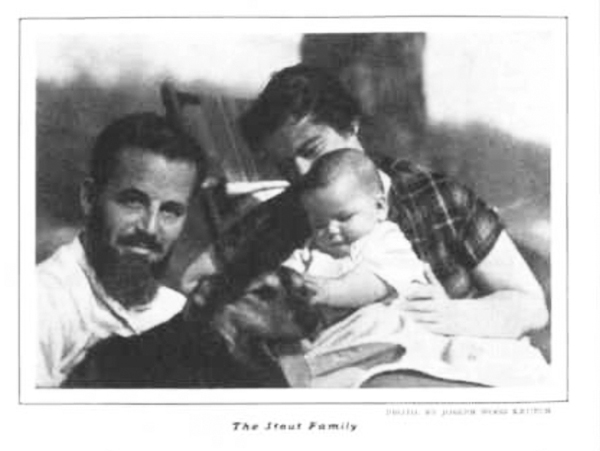

Here is Stout with his wife Pola and daughter Barbara in 1935.

Are these stories still read? I hope so. When I quizzed the grad students in my seminar this spring, most seemed unaware of what for me–and, I think, other baby boomers–were major figures in popular culture. It’s partly because the ancillary media never did a good job spreading the word. The film Meet Nero Wolfe (1936) was weak, in keeping with the general failure of 1930s films to capture the strengths of supersleuths like Philo Vance and Ellery Queen. (Better were the Mr. Moto and Charlie Chan vehicles.) During the late 1990s, Bantam reprinted the books in quality paperback editions, with introductions by other writers (Westlake, Lippman et al.). There was a solid cable-TV series (A Nero Wolfe Mystery) back in the early 2000s, with a trying-a-bit-too-hard Timothy Hutton as Archie but a near-definitive Wolfe in the form of Maury Chaykin. But that’s all pretty far back now.

O well . . . . If Perry Mason can come back, maybe Wolfe and Archie can too. And they won’t be scruffy and unshaven. Archie explains: “I was born neat.” So was his prose.

Today, I’m posting a long (22,000 words!) essay on Wolfe and Archie in an effort to show some reasons they and their creator matter. Background follows below.

Research? Say rather, obsession

Like most academics, I try to pour my obsessions into my research. My interest in mystery stories (fiction, film, even theatre and TV) is surfacing in my current project, a book studying principles of popular narrative as they emerge in thrillers and detective stories. In a way, the book turns inside out what I tried to do in Reinventing Hollywood. There I traced film techniques to sources in adjacent media. Now I’m looking directly at those media to consider their formal and stylistic strategies, with some consideration of how film shaped and was shaped by them.

My survey covers familiar ground. I consider the classic detective story (the so-called “Golden Age” of Christie, Sayers, Queen, Carr et al.), the hardboiled writers, the suspense thriller, and the crystallization of major techniques in the 1940s (a polemical point with me). Later chapters analyze the heist plot, the police procedural, and particular writers (e.g., Cornell Woolrich, Ed McBain, Richard Stark, Patricia Highsmith). As presently planned, the book ends with an odd-couple pair of chapters: the “puzzle film” trend of the 1990s, and the domestic thriller of recent years (Gone Girl, The Girl on the Train). Some chips from the workbench have littered this blog, as the links indicate.

One of my key questions is: What has enabled readers and viewers to welcome the sort of extreme complexity that we find in movies like Pulp Fiction or Memento? We’re all now connoisseurs of narrative intricacy, in not only crime plots but science-fiction and fantasy ones (which actually often rest on mysery premises; see Devs).

Another theme of the book is one I pitched in Reinventing Hollywood. I argued that very quickly “modernist” innovations in fictional technique were channeled into something more moderate and middlebrow. It’s there that wider audiences gained proficiency in handling flashbacks, ellipses, plunges into subjectivity, opaque exposition, and other challenges to linear storytelling. At the end of the 1920s, while Joyce and Woolf and Faulkner were pushing modernism into ever more recondite byways (Finnegans Wake, The Waves, The Sound and the Fury), other writers were adapting advanced techniques to traditional ends.

Another theme of the book is one I pitched in Reinventing Hollywood. I argued that very quickly “modernist” innovations in fictional technique were channeled into something more moderate and middlebrow. It’s there that wider audiences gained proficiency in handling flashbacks, ellipses, plunges into subjectivity, opaque exposition, and other challenges to linear storytelling. At the end of the 1920s, while Joyce and Woolf and Faulkner were pushing modernism into ever more recondite byways (Finnegans Wake, The Waves, The Sound and the Fury), other writers were adapting advanced techniques to traditional ends.

And traditional genres. I’ll argue that modernist experiments provided some strategies that mystery writers could recast within the bounds of their tradition. Stout’s first two serious novels, How Like a God (1929) and Seed on the Wind (1930) joined the trend toward mainstreaming modernism. By 1930 he had fully absorbed what the 1910s-1920s writers had achieved. What’s less obvious is the mark of modernist writing on his reader-friendly detective stories. Yet one lesson of modernism, I think, is the need to play with language, to “defamiliarize” literary texture. That, I think, is one of the tasks Stout took on in the Wolfe saga.

I had planned to include a chapter on the Wolfe/Archie series, but what resulted was far too long in comparison with its mates. So I’m posting it online as an essay. A shorter version will show up, somehow, in the finished book.

Luckily, thanks to the Internetz, the essay’s web incarnation can include some illustrations from magazine publication of the stories. Since most of the books’ drama takes place in Wolfe’s office, artists are challenged to find nifty ways to show people grouped around a desk.

I hope, then, that fans of the series will find some ideas and information of interest. Above all, I hope what I’ve said here and there will stimulate novices to venture on one of the great exercises in American popular storytelling. If you don’t care for it, all I have to say is: Pfui.

There are many good websites devoted to mystery fiction. The most comprehensive is Mike Grost’s. You should also look into Martin Edwards’ fine blog Do You Write Under Your Own Name? See also the official Wolfe Pack site, full of links and assorted Stoutiana. John McAleer’s biography Rex Stout (Little, Brown, 1977) is vastly informative. Stout was not only a great writer but also a fascinating man.

P.S. 8 July 2020: I’ve just learned that jazz pianist Ethan Iverson has posted on his site “Comfort Food,” a superb appreciation of Nero and Archie’s world. He discusses all the books, and even includes a page of Stout’s FBI file!

Fer-de-Lance, serialized as “Point of Death” in American Magazine (November 1934).

Auteurs by the hour: The Walker Art Center Dialogues

DB:

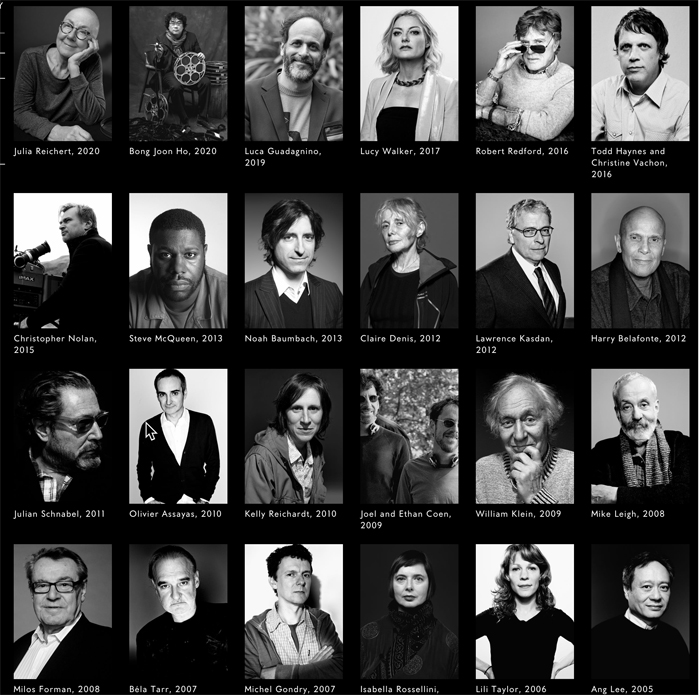

For decades, the world’s top filmmakers have made pilgrimages to the splendid Walker Art Center of Minneapolis. A series of astute curators of film provided a keen public with in-depth conversations about cinema. Now, suitable for a podcast-friendly era, the Center has given the world precious recordings of those discussions. The talent on display is overwhelming. Here’s just the half of it.

Some dialogues are audio only, but many are carefully mounted videos, with stills and clips. The questioners have been chosen from the ranks of archivists, programmers, critics, and academics. (I did one with Altman in 1992.) There are also written transcripts available for download.

In all, this should provide cinephiles with a rich array of ideas and information for years to come: Film history on the hoof. Thank you, Walker demi-gods, for reminding us that the Internet can be benign.

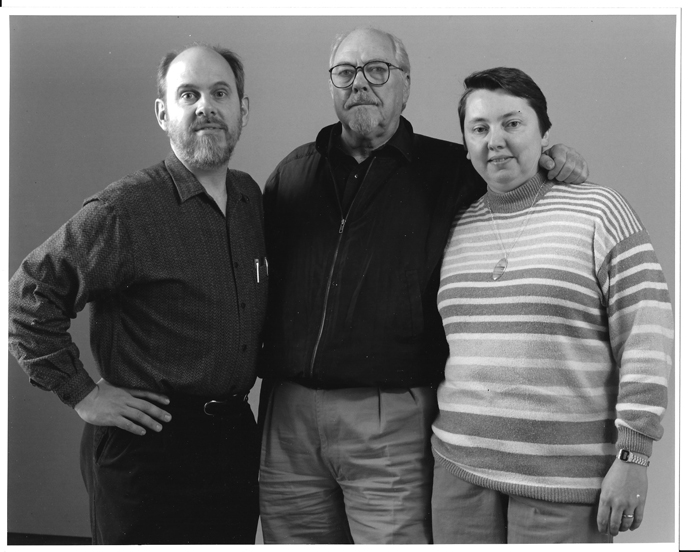

DB and KT with Robert Altman, Walker Art Center 1992.