Archive for the 'National cinemas: China' Category

News from Hou

Hou Hsiao-hsien and producer and production designer Huang Wen-ying on the set of The Assassin. Photo by James Udden.

DB here:

Stephen Cremin brings good tidings: Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Assassin, a project planned since 1989 and in production for several years, has completed shooting. It’s aimed for Cannes. More details at Film Business Asia.

About a year ago Jim Udden visited Hou on the set and shared his insights with us in this entry.

A new Hou film, especially if it featured swordplay, would make me a very happy man. 2013 was a good year for several top Chinese directors, especially Tsai Ming-liang, Jia Zhang-ke, Johnnie To Kei-fung and Wong Kar-wai. Having a new film from Hou augurs well for the Year of the Horse. And it stars the sultry Shu Qi.

P.S. 19 January 2014: Alas, the Year of the Horse won’t be as auspicious as I’d hoped. Jim Udden tells me, on the basis of a message today from Ms. Huang, that The Assassin will require another year for post-production. But they are likely to show some clips at Cannes, so there’s that. . . . Thanks to Jim and Ms. Huang for the correction and update.

Picking up the pieces; or, a Blog about previous blogs

A not-so-intimate bedroom scene from Cinerama Holiday (1955).

DB here:

Many of our blog entries are written in response to current events–a new movie, a film festival in progress, a development in film culture. Later we sometimes add a postscript (as here) bringing an entry up to date. Today, though, enough has happened in a lot of areas to push me to post the updates in a single stretch. It’s a sort of aggregate of chatty tailpieces to certain entries over the last year or so. Should the impulse seize you, you can return to an original entry, and there are other peekaboo links to keep you busy.

Out and about

Drug War.

Kristin wrote in praise of Neighbouring Sounds when she saw it at the Vancouver International Film Festival in 2012. Roger Ebert gave it a five-star rating, and A. O. Scott placed it on his annual Ten Best list. This network narrative is Brazil’s official entry for the Academy Awards. Sample Neighbouring Sounds here; the DVD is coming in May.

The annual Golden Horse Awards at Taipei have finished, and the Best Picture winner was the Singaporean Ilo Ilo, which neither Kristin nor I have seen. It would have to be exceptionally good to match the other films nominated, all of which we’ve discussed: Tsai Ming-liang’s Stray Dogs, Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster, Jia Zhang-ke’s A Touch of Sin, and (probably my favorite film of the year so far) Drug War, by Johnnie To Kei-fung. Stray Dogs did bring Tsai the Best Director award and his actor Lee Kang-sheng a trophy for best lead. Wong’s Grandmaster picked up six trophies, including top female lead and Best Cinematography. Jackie Chan won an award for Best Action Choreography. Although his CZ12 struck me as pretty dismal as a whole, its closing montage of Jackie stunts from across his career was more enjoyable than most feature-length films. In all, this has been a splendid year for Chinese-language cinema.

Back in the fall of 2012, I celebrated Flicker Alley‘s admirable release of This Is Cinerama, a very important film for those of us studying the history of film technology. Now Jeff Masino and his colleagues have taken the next step by releasing combo DVD-Blu-ray sets of two more big pictures, Cinerama Holiday (1955), the sequel to the first release, and South Seas Adventure (1958), the fifth and last of the cycle. Both are in the Smilebox format, which compensates for the distortions that appear when the curved Cinerama image is projected as a rectangle. Fortunately, Smilebox retains the outlandish optics to a great extent. The image surmounting today’s entry would give Expressionist set designers a run for their money, and it recalls the Ames Room Experiments. Cinerama wrinkles the world in fabulous ways.

Filled out with facsimiles of the original souvenir books and supplemented with a host of extras putting the films in historical context, these discs are fine contributions to our understanding of widescreen cinema. Because film archives don’t have the facilities to screen Cinerama titles (if they even hold copies), we have never been able to study, or even see, films that now look gloriously peculiar. Dare we hope that, from The Alley or others, we’ll get The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962), a strange, clunky, likeable movie?

Bookish sorts

Spyros Skouras and Henri Chrétien.

2013 saw the first of our online video lectures, one on early film history and the other on CinemaScope. The response to them has been encouraging, but as usual nothing stands still. If I were preparing the ‘Scope one now, I would draw from the newly published CinemaScope: Selected Documents from the Spyros P. Skouras Archive. Skouras was President of 20th Century-Fox, and he kept close tabs on the hardware he acquired from Chrétien in 1953. This collection of documents, edited by Ilias Chrissochoidis, shows that Skouras saw ‘Scope as a way to follow Cinerama’s path and boost the studio’s profits. “I would hate to think what would have happened to us if we had not created CINEMASCOPE. . . . Certainly we could not have continued much longer with the terrific losses we have taken on so many of our pictures.” ‘

Scope didn’t rescue the industry, or even Fox, from the postwar doldrums, but some of the behind-the-scenes tactics of the format’s first years are revealed here. For example, Skouras hoped that filmmakers would put important information on the surround channels deployed by the format, in the hope that theatre owners would make more use of them. “Such scenes would have to be unusual ones, but even with my limited imagination I can visualize many scenes in which dialogue would be heard from only the rear or the sides of the theatre.” This seems fairly extreme even today.

Jeff Smith is a swell colleague here at UW–Madison. (He and I are teaching a seminar that’s just winding down. More about that, I hope, in a later entry.) In his May guest entry for us, Jeff wrote about the new immersive sound system Atmos. But he’s been busy filling hard covers too. Research articles by him have appeared in three new books on film sound.

To Arved Ashby’s Popular Music and the New Auteur: Visionary Filmmakers after MTV Jeff contributed “O Brother, Where Chart Thou?: Pop Music and the Coen Brothers”–surely required reading in the light of Inside Llewyn Davis. He’s also a contributor to two monumental volumes that will set the course of future sound research. David Neumeyer has in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies gathered a remarkable group of foundational chapters reviewing the state of the art. Jeff’s piece charts the changing relations between the film industry and the music industry, from The Jazz Singer to Napster and file-sharing. For another doorstop volume, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, edited by John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (three more top experts), includes a powerful essay in which Jeff shows how techniques of intensified continuity editing have their counterparts in scoring, recording, and sound mixing. Not to mention his forthcoming book on an altogether different subject, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. All in all, a busy man–the kind we like.

To Arved Ashby’s Popular Music and the New Auteur: Visionary Filmmakers after MTV Jeff contributed “O Brother, Where Chart Thou?: Pop Music and the Coen Brothers”–surely required reading in the light of Inside Llewyn Davis. He’s also a contributor to two monumental volumes that will set the course of future sound research. David Neumeyer has in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies gathered a remarkable group of foundational chapters reviewing the state of the art. Jeff’s piece charts the changing relations between the film industry and the music industry, from The Jazz Singer to Napster and file-sharing. For another doorstop volume, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, edited by John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (three more top experts), includes a powerful essay in which Jeff shows how techniques of intensified continuity editing have their counterparts in scoring, recording, and sound mixing. Not to mention his forthcoming book on an altogether different subject, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. All in all, a busy man–the kind we like.

My March essay, “Murder Culture,” devoted some time to the women writers of the 1930s and 1940s who created the domestic suspense thriller–a genre I believe has been slighted in orthodox histories of crime and mystery fiction. The piece brought friendly correspondence from Sarah Weinman, editor of a new anthology from Penguin: Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives. She has assembled a fine collection, boasting pieces by Vera Caspary, Dorothy B. Hughes, Charlotte Armstrong, Dorothy Salisbury Davis, Margaret Millar, Patricia Highsmith, and Elisabeth Sanxay Holding (whom Raymond Chandler considered the best suspense writer in the business). These stories will whet your appetite for the excellent novels written by these still under-appreciated authors. Sarah’s wide-ranging introduction to the volume and her headnotes for each story will guide you all the way.

Finally, not quite a book but worth one: “The Watergate Theory of Screenwriting” by Larry Gross has been published in Filmmaker for Fall 2013. (It’s available online here to subscribers.) The essay is based on the keynote talk that Larry gave at the Screenwriting Research Network conference here in Madison.

Digital is so pushy

From Doddle.

Back in May, I provided an update on the progress of the digital conversion of motion-picture exhibition. Today, 90% of US and Canadian screens are digital, and over 80% worldwide are. (Thanks to David Hancock of IHS for these data.) I wish I could say the Great Big Digital Conversion was at last over and done with, but we know that we live in an age of ephemera, in which every technology is transitional. As I was finishing Pandora’s Digital Box in 2012, the chatter hovered around two costly tweaks.

The first involved higher frame rates. One rationale for going beyond the standard 24 fps was the prospect of greater brightness to compensate for the dimming resulting from 3D. Peter Jackson presented the first installment of his Hobbit film in 48 fps in some venues, and James Cameron claimed that Avatar 2 and its successor would utilize either 48 fps or 60 fps. And in January of this year some studio executives predicted that 48 fps would become standard.

Not soon, though. The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug will play in 48 fps on fewer than a thousand screens. Bryan Singer, who praised the process, has pulled back from handling the next X-Men movie at that frame rate. The problem is partly cost, with 48fps demanding more rendering and vast amounts of data storage. As far as I can tell, no one but Jackson and Cameron are planning big releases in the format.

The other innovation I mentioned in Pandora was laser projection. It too will brighten the screen, and according to its proponents it will also lower costs. Manufacturers are racing to build the machines. Christie has presented GI Joe: Retaliation in laser projection at AMC Theatres’ Burbank complex, and the firm expects to start installing the machines in early 2014. Seattle’s Cinerama Theatre is scheduled to be the first. NEC, the Japanese company, premiered its laser system at CineEurope in May. A basic NEC model designed for small screens (right) will cost about $38,000—an attractive price compared to the Xenon-lamp-driven digital projectors currently available. But the high-end NEC runs $170,000!

How to justify the costs? One Christie exec suggests branding: “Laser is a cool term that audiences immediately identify with.”

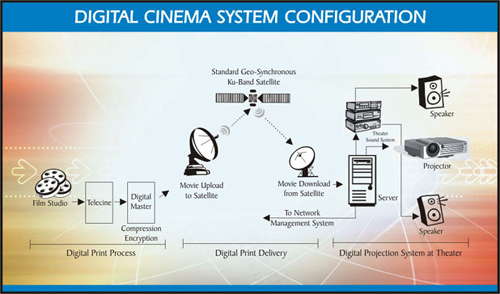

Perhaps the most important innovation since last spring’s entry involves an electronic delivery system. In October, the Digital Cinema Distribution Coalition, a consortium of the top three theatre chains along with Warners and Universal, launched a satellite and terrestrial network for delivering movie files to theatres. Theatres are equipped with satellite dishes, fiberoptic cable, and other hardware. The new practice will render the current system of shipping out hard drives obsolete, although the drives will probably continue for a time as backups. The DCDC has scheduled over thirty films to be sent out this way by the end of the year, and 17,000 screens in the Big Three’s chains are said to be hooked up. For more information, see David Hancock‘s IHS Analyst Commentary.

In the 1990s, satellite transmission was touted as the best way to send out digital films, and it was tried with Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones in 2001. Sometimes things move in spirals, not straight lines.

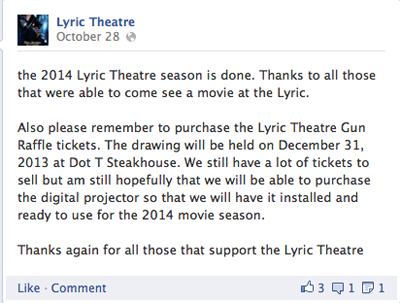

Speaking of the Conversion, an earlier entry pointed out the creative strategy used by the Lyric Theatre in Faulkton, South Dakota to finance its digital changeover. A gun raffle was announced on the Lyric’s Facebook page. Top prize was planned to be a set of three weapons: an AR-15 rifle, a shotgun, and a 1911 pistol.

The theatre’s screening season concluded, but the raffle is going forward, on New Year’s Eve, no less.

Television in public, movies in private

Dr. Who: Day of the Doctor (2013).

I can’t stand all this digital stuff. This is not what I signed up for. Even the fact that digital presentation is the way it is right now–I mean, it’s television in public, it’s just television in public. That’s how I feel about it. I came into this for film. —Quentin Tarantino

Spirals again. When attendance began to slump after 1947, Hollywood tried a lot of strategies–color, widescreen processes like Cinerama and ‘Scope, stereo sound, and not least “theatre television.” Prizefights, wrestling matches, and even operas were transmitted closed-circuit. Now theatre television is back, made possible by The Great Big Digital Convergence.

Godfrey Cheshire predicted some fourteen years ago that as theatres became “TV outside the home,” what we now call “alternative content” would become more common.

Pondering digital’s effects, most people base their expectations on the outgoing technology. They have a hard time grasping that, after film, the “moviegoing” experience will be completely reshaped by–and in the image of–television. To illustrate why, ponder this: if you were the executive in charge of exploiting Seinfeld’s last episode and you had the chance to beam it into thousands of theaters and charge, say, 25 dollars a seat, why in the hell would you not do that? Prior to digital theaters, you wouldn’t do it because the technology wouldn’t permit it. After digital, such transpositions will be inevitable because they’ll be enormously lucrative.

Godfrey’s prophecy has been fulfilled by all the plays, operas, and other attractions that run in multiplexes during the midweek or Sunday afternoon doldrums. His Seinfeld analogy was reactivated by last month’s screenings of Dr. Who: The Day of the Doctor in 3D. It was shown on 800 screens in seventy-five countries, from Angola to Zimbabwe, while also being broadcast on BBC TV (both flat and stereoscopic). The Beeb boasted that the per-screen average for the 23 November show beat that of The Hunger Games: Catching Fire. Globally, it took in $10 million, despite being available for free on TV and the Net. In the US, the event was coordinated by Fathom, a branch of National Cinemedia, a joint venture of the Big Three chains.

While some complained about dodgy 3D in the show, a surprisingly fannish piece in The Economist declared that “this landmark episode was buoyed up with fun, silliness, and hope.” The larger prospect is that other TV shows will take the hint and host season premieres or end-of-season cliffhangers in theatres. Many art house programmers would kill to show episodes of Game of Thrones or Mad Men, or even marathon runs of House of Cards. If it happens at all, I’d bet on Fathom getting there first.

I’ve had little to say, in this arena or in Pandora, about streaming and VOD, but these are becoming important corollaries of the Great Big Digital Convergence. Netflix in particular is expanding its reach, growing its subscriber base, creating original series, and enhancing its stock value, despite some ups and downs. At the same time, it’s pressing studios and exhibitors for the reduction in “windows,” the periods in which films are available on different platforms.

The theatrical window was traditionally the first, followed by second-run theatrical, airline and hotel viewings, pay cable, and so on down the line. Now that households have fast web connections, streaming disrupts that tidy business model. In October Ted Sarandos, Chief Content Officer for Netflix (right, with Ricky Gervais), suggested that even big pictures should go day-and-date on Netflix.

The theatrical window was traditionally the first, followed by second-run theatrical, airline and hotel viewings, pay cable, and so on down the line. Now that households have fast web connections, streaming disrupts that tidy business model. In October Ted Sarandos, Chief Content Officer for Netflix (right, with Ricky Gervais), suggested that even big pictures should go day-and-date on Netflix.

“Why not follow with the consumer’s desire to watch things when they want, instead of spending tens of millions of dollars to advertise to people who may not live near a theater, and then make them wait for four or five months before they can even see it?” he added. “They’re probably going to forget.”

Exhibitors howled. Sarandos quickly recanted, saying only that he wanted people to rethink the current intervals between theatrical and ancillary release.

Some observers speculated that his October remarks were staking out an extreme position he intended to moderate in negotiations down the line–possibly to suggest that mid-budgeted pictures would be good ones to experiment with on day-and-date. Perhaps too Netflix was emboldened by the much-publicized remarks of Spielberg and Lucas in a panel last June, when they indicated that the future for most movies was VOD, with multiplexes furnishing more costly entertainments for the few. (In the same session, Lucas predicted that brain implants would allow people to enjoy private movies, like dreams.)

In any event, windows are already shrinking. In 2000, the average theatrical run was 170 days; now it’s about 120 days. With about 40,000 screens in the US, films play off faster than ever before. Video piracy, which makes new pictures available well before legal DVD and VOD release, puts pressure on studios to shorten windows. It seems likely that the windows and the intervals between them will shrink, perhaps allowing films to go to all video formats as quickly as 30-45 days after the theatrical release ends.

Studios have incentives to shorten the windows, if only because a single promotional campaign can be kept going long enough for both theatrical and home release. In addition, buying or renting a movie with a couple of clicks encourages impulse purchasing, and the cost feels invisible until the credit-card bill comes. Nonetheless, commitment to day-and-date home delivery would be risky for the studios.

Hollywood is more than ever before playing to the global audience. Even with the VOD boom, digital purchase and rental constitute a small portion of the world’s movie transactions. According to IHS Media and Technology Digest, theatrical ticket sales, purchase and rental of physical media (DVD, Blu-ray) add up to nearly 12 billion transactions, while Pay Per View, streaming, and downloads come to only about a billion or so. (These categories omit subscription services like cable television and basic VOD on Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, and the like.) Moreover, customers in 2012 spent about 61 billion dollars buying tickets to movies, buying DVDs, and renting DVDs. Tania Loeffler of the IHS Digest writes of North America, the most developed market for digital sales and rental:

Movie purchases made online in North America increased year-on-year by 36.6 per cent to reach 29.2m transactions. The rental of movies online also increased, to 112m transactions, an increase of 57.3 per cent over 2011. Despite this strong growth, movies purchased or rented via over-the-top (OTT) online movie services still only accounted for a combined $836m, or 3.3 per cent of total consumer spending on movies in North America.

By contrast, worldwide consumer spending on theatrical movies actually grew in 2012, to a whopping $33.4 billion–over 50 % of all movie transactions. (Thank you, Russia and China.) And despite the decline of disc purchases and rentals, Loeffler estimates that physical media will still comprise about thirty per cent of worldwide movie transactions through to 2016.

Theatrical releases continue to offer studios the best deal. Because the prices of streaming and downloaded films are low, there is less to be gained from them. True, if windows shrink, the studios will demand that Netflix and its confrères price VOD at high levels, say $25-50 for an opening-weekend rental. But consumers used to cheap movies on demand could balk at premium pricing.

At present, digital delivery of movies to the home provides solid ancillary income to the distributors, even if it doesn’t yet offset the decline in physical media. Add in Imax and 3D upcharges, and things are proceeding well for the moment. Like the rest of us, moguls pay their mortgages in dollars, not percentages or transactions. As long as some hits keep coming, we should expect that studios will maintain an exclusive multiplex run for major releases, as the most currently reliable return on investment.

Orpheum metamorphosis

The New Orpheum Theatre, 216 State Street, 1927.

Another note on exhibition relates to the last commercial picture palace in downtown Madison, Wisconsin. My July 2012 entry related the conspiratorial tale of how the grand old Orpheum Theatre on State Street fell on hard times. In fall of 2012 the building seemed slated for foreclosure, but then maybe not. Last month Gus Paras, a hero of my initial post, stepped forward and bought the old place. According to Joe Tarr in our politics and culture weekly Isthmus, there’s a lot of work to do.

Plaster is crumbling off sections of the ceiling, the result of years of water damage from a leaky roof. The walls are littered with scratches and marks, in bad need of a paint job. A plastic garbage can sits in the theater, collecting water leaking from an upstairs urinal. Paras even found dried-up vomit in two spots on the carpet.

Making matters worse, Monona State Bank, which controlled the property while it was in foreclosure, filled in the “vaults” behind the theater, which means replacing the building’s frail boilers and air conditioning will be much more complicated and expensive.

“I don’t have any idea how I’ll get the boiler in and out,” Paras says. “The stairs are not strong enough.”

Envoi

Have any of you worked on a film, say, 10 years ago, and it comes out on Blu-ray and you look at it and think, “This isn’t the film I’ve shot”?

Bruno Delbonnel (DP, Inside Llewyn Davis): Always. Always.

Barry Ackroyd (DP, Captain Phillips): I’ll be watching and it’s in the wrong format.

So what is it like to devote your lives and careers to creating images that you know exist only momentarily in their absolute best state, that may never be seen by most people the way you would like them to be seen?

Sean Bobbitt (DP, Twelve Years a Slave): At least you get a chance to see it once. All you can do is hope that people will see an approximation of that. I’ve been to screenings where I’ve had to get up and walk out because I just couldn’t bear to watch the film in the state it was in. But at the end of the screening, people say, “That was fantastic. That was beautiful. Well done!” and you’re thinking, “If only they had seen the real thing.” We would drive ourselves mad if we worried too much about it.

On shrinking windows, see Andrew Wallenstein and Ramin Setoodeh, “Exhibitors Explode over Netflix Bomb,” Variety (5 November 2013), 16. The chart on this page doesn’t appear in Variety‘s online edition of the story. Tania Loeffer’s report, “Transactional Movies: The Big Picture,” appeared in IHS Screen Digest (now IHS Media and Technology Digest) for April 2013, 123-126. Douglas Gomery discusses the theatre television plans of the 1940s-early 1950s in his Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States, pp. 231-234. My envoi comes from a revealing conversation among cinematographers at The Hollywood Reporter.

A 2012 catchup blog chronicling earlier phases of these developments is here.

P.S. 23 December 2013: David Strohmaier, the creative force behind the Cinerama restorations, has put online the stirring original trailers for Search for Paradise (low resolution and high-definition) . David attended the U of Iowa when Kristin and I did, though alas we didn’t meet him. He deserves a big thank-you for all his work in making these extraordinary films available to us.

The Grandmaster.

Mixing business with pleasure: Johnnie To’s DRUG WAR

Drug War (2012).

DB here:

At first glance, Drug War (2012) seems an unusual film for Johnnie To Kei-fung and his Milkyway Image company to make. For one thing, this Mainland production lacks the surface sheen of To’s Hong Kong projects. Shot in wintry Jinhai, a northern port city, and in the central city of Erzhou, it presents stretches of industrial wasteland and bleak superhighways. As a result, To’s characteristic audacious stylization gives way to a bare-bones look. The saturated palette of The Longest Nite (1998) and A Hero Never Dies (1998) is gone, replaced by metallic grays and frosty blues. Hong Kong heartthrob Louis Koo, rapidly becoming To’s jeune premier, is bluntly deglamorized—first glimpsed spewing foam as he tries to steer his car, then moving through the film with a blistered face and a bandaged nose. The noir-flavored Exiled (2006) made its steamy Macau locales seem exquisitely somber and menacing, but Drug War’s early scenes in a hospital have a mundane, documentary quality. Little in To’s earlier work prepares us for the grubby scene of drug mules groaning as they shit out plastic pods of dope.

Of course it’s a crime story, the genre in which To and his writer-producer collaborator Wai Ka-fai have gained most acclaim. More specifically, it’s a police procedural, a mode they have worked skillfully with Expect the Unexpected (1999) and Mad Detective (2007). Those, like most cop movies, thread the personal lives of the investigators into the cases they’re running. Drug War, though, gives us no glimpse of the cops off-duty. The result presents our officers as strictly business: no wives, kids, or civilian pals distract them from their mission. In this respect, the film’s closest analogue is probably PTU (2003), but even that showed its patrolling cops in more camaraderie and clashes than we get here.

True, there are brief moments of comradeship, as when Yang offers money to help the cops from Erzhou, and her colleagues chip in. A marvelous shot juxtaposes one cop’s cash with the video stream of the burning bills in the ceremony honoring Timmy’s dead wife and her brothers.

Yet the result humanizes the crooks more than the cops. Timmy mourns his family; we don’t know if Captain Zhang has one.

The concentration on routine and tactics is due partly to the action’s compressed time frame: the seventy-two hour pursuit of the drug gang permits no rest. In addition, made chiefly for the Mainland audience (with Mainland funding), Drug War was subject to censorship that’s more stringent than that in Hong Kong. It may be that To, Wai, and their screenwriting team were cautious about integrating personal lives into their plot. Exploring the officers’ off-duty frailties and failures might have made censors fret. And of course the emphasis on selfless officers sacrificing their personal lives sends a positive ideological message.

I think that the film benefits in other ways from skipping what Ross Chen calls “cop soap opera” and focusing relentlessly on the central cat-and-mouse game. Zhang’s investigation becomes engaging for us thanks to well-honed Milkyway narrative maneuvers: a focus on suspenseful strategies and unexpected countermeasures, the weaving together of various destinies, a fascination with doubling and mirroring, surprising genre tweaks, and unusually laconic signaling of story information. Beneath its drab, almost generic surface and its apparently prosaic account of police procedure, Drug War offers a typically engrossing, off-center Milkyway experience.

And yes, gunfights are involved. But even those are not quite business as usual.

Live or die, I’ll be with you

After a prologue in which a vomiting Timmy Choi Tin-ming crashes his car into a restaurant, we see several lines of action converging at a highway tollbooth. A truck driven by two drug-addled men pulls through, followed by two more men in a muddy red sedan. Soon an overheating bus pulls up. Panicking, the drug traffickers inside make a run for it before they’re brought down by highway officers and Captain Zhang Lei, who has been working undercover on the bus. The mules are taken to a hospital—the second convergence point—and there Captain Zhang notices that Timmy, borne by on a gurney, has burns typical of a drug explosion. Zhang and female officer Yang Xiaobei visit the site of Timmy’s crash, where they find his cellphone. Its mysterious call queue launches their investigation.

If you haven’t yet seen the film, I hope that the preceding has whetted your interest. From now on, I’m afraid I must indulge in what we in the trade call spoilers.

The tollbooth confrontation, it turns out, is a sting operation by which Zhang can nab the traffickers he has infiltrated. The truckers who pass through at the same time are bringing ingredients for Timmy Choi’s local meth factory, and the red sedan is carrying cops who’ve been tracking them. When Zhang and Yang find Timmy’s cellphone, they find dozens of missed calls from the truck drivers, and this enables them to connect Timmy with the shipment. His lab has exploded, killing his wife and her brothers. He escaped but suffered the burns and nausea we saw at the outset.

To escape the death penalty Timmy offers to turn snitch. The rest of the film will intercut among various lines of action: the truckers and their pursuers, the cops using CCTV cameras to track the crooks, and Zhang’s efforts to use Timmy to infiltrate the ring. Zhang’s strategy takes him up the chain of command. There is the laughing Jinhai smuggler HaHa and his wife, who are trying to become drug distributors by means of the port they control. They are wooing the cokehead Li Suchang, his superior Uncle Bill Li, and the real bosses, a Hong Kong gang headed by Fatso (Milkyway regular Lam Suet). Timmy, who knows them all, is positioned as go-between. As with many Hong Kong films, a hierarchy of villains permits a cascade of meetings, showdowns, chases, and chance encounters. Through it all, the question persists: Can Zhang trust Timmy to stay bought?

The first third of the film centers on Zhang’s daring scheme to penetrate the gang. Since HaHa and Li Suchang (called Chang in the English subtitles) have never seen one another, he forces Timmy to set up two meetings. The meetings are timed so that Zhang can impersonate Li in the first meeting and then play HaHa in the second. The result is a pair of virtuoso scenes I’ll go into shortly.

The central chunk of the film follows Timmy’s efforts to get a fresh load of dope for Zhang’s deal. His source is another of his factories, this one staffed by a family of deaf-mutes (a typically perverse Milkyway genre tweak). This section culminates in two intercut police raids: one, a painless seizure of HaHa and his wife, the other a bloody shootout in the factory. The two mutes in charge escape through a hidden passageway, a ploy that renews Zhang’s distrust of Timmy. Timmy vows that he didn’t know about the escape hatch.

The film’s final third introduces the Hong Kong gang directing Uncle Bill from behind the scenes. The film’s first two sections have emphasized the cops’ ability to track the gang with public surveillance cameras and minicams secreted in hotel suites and in the meth warehouse. Now we learn that the gang has its own technology. Hidden microphones and wireless recorders allow gang members to listen to conversations. Fatso feeds dialogue to Uncle Bill in his negotations with Zhang/HaHa. In their final rendezvous at a nightclub, Zhang discovers the ruse and uses it as an excuse to finalize the deal. But when the Hong Kongers demand a night out just for themselves, Captain Zhang must let Timmy go off with them and trust him to deliver them to him the next day.

Timmy betrays everyone. At the climax all the forces in play converge once more, this time outside a primary school. Cars bearing police surround the vehicles carrying the gang. Even the truckers are summoned by Timmy, and eventually the deaf-mutes show up too. Timmy tears off the wire he’s wearing, tells the gang that it’s an ambush, and launches an all-out firefight. While cops and crooks blast each other, Timmy slips into a school bus to hide from the barrage.

The gang is cut down, but so too are the police, including Yang. Even our protagonist Zhang is fatally wounded. Hong Kong aficionados will find here echoes of the pitiless climax of another Milkyway policier I probably should not specify.

The film’s epilogue, like the prologue, centers on Timmy in extremis. In prison he’s strapped down for lethal injection while he babbles the name of every dealer he knows, hoping somehow to save himself from execution. He fails.

Perhaps the most memorable image in the film’s final moments comes a bit earlier, at the end of the gun battle. Timmy brutally finishes off Captain Zhang, only to discover that Zhang has handcuffed his wrist to Timmy’s ankle. Timmy is captured frantically dragging Zhang’s corpse around the street, fulfilling Zhang’s warning after the ill-fated factory raid: “Live or die, I’ll be with you.”

Playing parts

Within this broad movement toward giving Timmy his punishment, at horrendous cost to the forces of law, To and Wai have built fine-grained scenes that swerve the conventions of cop movies in typical Milkway directions. The chief example involves large-scale repetition. During the first section, Zhang goes undercover, pretending to be a gang member. The subterfuge is given a twist: Zhang impersonates Li Suchang in his meeting with HaHa, then he impersonates HaHa in his meeting with Suchang. Once more a Milkyway film finds tricky drama in symmetry and doubling.

The first impersonation goes more easily, but it gets a healthy dose of suspense. Zhang plays Li Suchang as a cold, impassive negotiator. He barely speaks in response to HaHa, who lives up to his name by supplying a stream of chatter and guffaws. He’s not as dense as he might appear, but Zhang has little trouble intimidating him. The problem is that the mini video camera hidden in Zhang/Li’s cigar case is first blocked by food on the table and then arouses the curiosity of HaHa. The tension rises as HaHa examines the case, but Timmy nonchalantly rescues it. His intervention reinforces our sense, in this stretch of the film, that he is cooperating smoothly with the police sting.

Once the charade is over, the film’s narration increases the suspense by the tight timing of the next meeting, which takes place only minutes after the first. Zhang and Yang, who will be playing HaHa’s wife, must change clothes swiftly and prepare cameras to record the deal. The real Li Suchang goes upstairs with Zhang and Timmy just as the real HaHa and wife saunter out of the other elevator: The shot sums up the charade Zhang has engineered, as well as the plot’s mirror structure.

The second encounter ratchets up the tension. Zhang and Yang imitate HaHa and his wife, whom they’ve watched moments earlier; they even repeat lines spoken by the real couple in the previous scene. But Li Suchang is a more aggressive bargainer than HaHa and offers Zhang/HaHa some cocaine. The real HaHa claimed never to have touched the drug, so Zhang/HaHa declines. But Li insists, so the policeman must snort a line. This induces a good deal of uneasiness, which is upped when Li insists he take another hit. Zhang/HaHa obliges and becomes woozy. When Li demands that he snort a third line, Timmy again intervenes and asks that they proceed with the deal. Li relents and they make an appointment with Uncle Bill.

After Li Suchang leaves, there follows a chilling scene in which Zhang goes into drug shock, collapsing to the floor and twitching frantically. Timmy explains what the other cops must do to save him, and by following his commands they revive Zhang. Again Timmy seems firmly on the side of the police. But Zhang still wonders: Did Timmy secretly signal to Li? His mistrust will expand when the deaf-mute factory workers elude the police through an exit that Timmy didn’t mention.

The motif of doubling, a To/Wai staple, runs through the movie: two truckers, two cops tailing them, two deaf-mute killers, two raids, two traffic encounters with the gang, two times that Zhang must trust Tommy and release him. Even the climax consists of not one but two gun battles, the first in front of the school, the second in a nearby street. But the scenes in which Zhang plays both parties in a drug deal serve as the most audacious instance, and a fine example of Milkyway’s gift for reimagining basic conventions of the crime film.

Milkyway’s rule of one

In Planet Hong Kong 2.0, as well as in my discussion of Mad Detective on this site, I suggest that despite all this obsessive doubling, Milkyway films tend to refuse the redundancy that crime movies usually demand.

One instance is the gradual revelation that in the opening, the bus overheating at the toll booth is part of a police trap. Not only is Zhang aboard (sporting a Stetson), but the ticket taker is Officer Yang and the driver (merely glimpsed) is one of Zhang’s men. Since the incident isn’t referred to as a sting afterward, we must realize on our own that this sequence furnishes an abrupt introduction to the police unit’s efficiency and farsightedness.

Another instance is a little less cryptic but has longer-term consequences. The police are preparing for the double masquerade, and Zhang lets Timmy pick out appropriate outfits for them to wear. In a scene lasting only forty-five seconds and ten shots, the emphasis is on Timmy’s careful selection of suits—presented, as we might expect, in imagery of pairing.

While this preparation is going forward, To inserts a shot of hands crushing aspirin tablets into powder.

Later we see that Officer Yang is filling a flask with the powdered aspirin.

What’s going on here? Another sort of film would have inserted dialogue something like this: HaHa hasn’t met Li Suchang, but he’s probably heard that he’s a druggie. He’ll expect me to use coke. If he offers, I’ll tell him that I use only my own. We’ll prepare some fake stuff for me to bring in a flask. And this would have been a clear setup for what will in fact happen in the first meeting. But we don’t get such a setup. Moreover, at this point Yang’s action is even more cryptic because we don’t yet know about Suchang’s addiction, which Zhang is planning to mimic. Yang is preparing a protective measure against a threat we will only learn of later.

The Milkyway writing team often treats story points in this peremptory way. If the Hollywood rule is “Tell the audience every major point three times,” To and Wai often assume that one mention is enough, and even that can come before we’re in a position to appreciate it. Indeed, Zhang’s scam depends completely on the fact that HaHa and Suchang have never met, but that premise is told us on only one occasion, and it’s not given much emphasis.

Again, we could play Hollywood scriptwriters and let Zhang and Yang huddle to explain how they will exploit the fact that the two gangsters can’t recognize each other. But the Milkyway team skips all that. The plan is devised offscreen. We next see Zhang and Timmy picking their wardrobe and Yang preparing the phony cocaine.

In the prologue, we have gotten another roundabout piece of foreshadowing. As Timmy’s car careens down the street, a single shot is presented as the view of a surveillance camera.

A more orthodox film would then cut to a Network Operations Center where concerned officials are watching traffic. But To simply cuts back to the car, where Timmy’s cellphone falls to the floor. Only after Timmy becomes a person of interest to the police do we see investigators re-running CCTV footage of the car. The one video shot has been a hint about how the police will build up their knowledge of Timmy. More broadly, it prefigures the importance of police video surveillance of the gang throughout the film.

Most laconic of all, I think, is the rather complicated scene taking place at a traffic light. The transfer of an important valise, containing money or drugs, is one of the most hoary conventions of the cop thriller. Director To makes it the occasion of a crisscrossing geometry and barely noticeable hints about Timmy’s ultimate aims.

Waiting at the light on the way to a meeting, Zhang as HaHa gets a call from Suchang and Uncle Bill, in a Mercedes sedan waiting behind them. There’ll be no meeting; a deal will be done right here. Zhang’s team is spread out in other vehicles backed up at the light.

But when Zhang as HaHa picks up a parcel to deliver to a white van further along the line of cars, To’s camera coasts rightward to show a dark van waiting in the next lane. We aren’t shown who’s in it. Soon, as Zhang transfers the bag to the van, we see yet another vehicle at the front of the line, and over his shoulder we see a woman inside.

Cut to inside that vehicle, where the woman, the driver, and a fat man in the back seat sit impassively.

Within the plot, the scene functions as Bill Li’s effort to determine whether he’s being set up. The transfer turns out to be a fake, aiming to confirm that Timmy has not turned snitch. If his associates are undercover cops, they are likely to reveal themselves here in order to make a bust. That would fail, because the bag Zhang ends up with carries only imported cigars.

Beyond its function as a test, the traffic stop plays a crucial narrational role. Through mere glimpses and without anything being prepared for, we’re introduced to the Hong Kong gang that will play a commanding role in the last third of the film. The subterfuge is that we haven’t yet been told that there is such a gang; at this point, they are simply oddly emphasized passengers in adjacent vehicles. A more traditional plot would have included an earlier scene in which the police identify the Hong Kong suspects and provide their backstory. Then, seeing them at the intersection would satisfy us that we were putting the story together. Instead, working with almost no dialogue, using the traffic backup as another convergence point, To and Wai have evoked a strange uneasiness. Who are these people, and why are we seeing them?

Immediately after these shots of adjacent vehicles, another dark van opens and a passenger sets a carrying case on the street. Yang in her guise of HaHa’s wife fetches that case. Then, in a slippery set of POV shots, Timmy turns and looks back at other men in vehicles, and then at Uncle Bill and Li Suchang, who seem to evade his stare.

Why dwell on Timmy at the height of the scene? For the first time we can study his reactions when his captors aren’t watching him. His calculating stare suggests that he knows, well before the police do, that the deal is a sham. He realizes that if the cops do take the bait and reveal themselves, only he will pay the price. Now he knows that he can’t count on the gang and that he’s on his own. At the climax he’ll take his revenge on both sides by halting the motorcade before it reaches the port, where cops are poised to arrest the gang. That will provoke the final shootout—which, like this scene, involves all the principals confronting one another in vehicles on the street.

This is a lot to load onto a brief, silent exchange of looks, but it’s typical of To and Wai’s glancing exposition. Another director would have provided stronger clues to what’s going on in Timmy’s mind, perhaps through flashbacks or voice-over. Yet that tactic would depend on our knowing who the people in the other cars are. Only later, before the meeting at HaHa’s port, will Timmy identify them. He will spill this information very quickly. And just once.

Since its founding in 1996, Milkyway Image has responded adroitly to changes in the regional film industry. For their local audience, To and Wai have created popular comedies, off-kilter thrillers, and unclassifiable items like Running on Karma (2003) and Throw Down (2004). They have occasionally completed coproductions with Europe (Vengeance, 2009) and an Asian branch of Hollywood (Turn Left, Turn Right, 2003). They have adjusted to the soaring Mainland market, even revising Breaking News (2004) to suit the censors. Just as a string of Milkyway romantic comedies yielded some financial stability in the 2000s Hong Kong market, more recent efforts like Don’t Go Breaking My Heart (2011) and Romancing in Thin Air (2012) have given the company a foothold in the PRC.

Yet Milkyway takes chances too. Election 2 (2006) surprised everyone with its bold acknowledgement of Triad networks on the Mainland; neither it nor its predecessor was shown theatrically there. Drug War has attracted notice among international critics for its frank treatment of the PRC underworld. To and Wai seem to find unusual opportunities in every project. Here, making Hong Kong gangsters the ultimate villains suggests that the pestilence comes primarily from elsewhere. At the same time, giving Timmy and the Hong Kong gang such prominence permits casting some of the Milkyway repertory company, familiar actors not only in Hong Kong and the Mainland but also in the international market.

Johnnie To, it seems, can zigzag his way to creative achievement in different circumstances. He and Wai are keeping Hong Kong cinema alive in unpromising times and finding new narrative resources in a genre that often seems played out. Their latest, Blind Detective (2013), is receiving pretty unfavorable notices, but this long, preposterous semi-comedy is, I expect, another symptom of the sidewinding strategy that characterizes their work.

With Milkyway, adventurous exploration of cinema is also a business plan. Catch them if you can.

Thanks to Geoff Gardner, Athena Tsui, Li Cheuk-to, To Kei-chi of Milkyway Image, and Crystal Decker of Well Go USA for their assistance in preparing this entry.

For a sensitive discussion of the film’s treatment of China, see Kozo’s review at LoveHKFilm.

Drug War performed sturdily at the Hong Kong box office (over US $600,000) but did really well in China, garnering upward of $23 million during its April release. Well Go and Variance open Drug War on 26 July for a US theatrical run. Before that it’s playing several festivals, including the mammoth TIFF Chinese series on 14 July. Mr. To will introduce the TIFF screening. The day before, 13 July, he will be present for a conversation.

Milkyway plots often rely on converging destinies, of character trajectories intersecting through chance. This principle is less pronounced in Drug War, except for the moments when the two truckers and the two deaf-mutes unexpectedly hook into the main plotline. Accidental convergence, often pointing up parallels among the characters, is clearer in A Hero Never Dies (1998) and Life without Principle (2011). I discuss the first film in Planet Hong Kong 2.0, the other in this entry.

P.S. later 8 June: Today you get double value. Grady Hendrix, Hong Kong film expert and one force behind Subway Cinema, writes with this thoughtful interpretation of Drug War–which makes it seem as daring thematically as it is in its narrative strategies.

For me, the most interesting element is the long game that I think To and Wai are playing and what I see as the secret heart of the movie. I think that the meaning of the film isn’t conveyed so much by the narrative as by the tools used to create the narrative: the actors. All of the cops are Mainland actors, most of the drug dealers are Hong Kong actors. What are drug dealers besides capitalism run amuck, completely unregulated? What are cops but authoritarian impulses, completely unregulated? The two groups have similar goals: make money at all costs; catch the criminals at all costs.

The cops in the film are China personified: they have unlimited resources, massive numbers, infinite organization, but they are heartless towards outsiders, unforgiving, and they don’t trust anyone. The criminals are all the stereotypes of Hong Kong-ers: they are family, they are stylish and chic, they eat meals together (Hong Kong people love to eat, after all) but they are only interested in money. They will save themselves and leave their wives to die, they will betray anyone (including their uncle and godfather), to make a buck. Both groups use the same tools, but they are opposites: unregulated capitalism vs. unregulated authoritarianism; the unstoppable object and the immovable force.

The fact that when put into conflict these two forces destroy each other is, I think, a critique of both Hong Kong and the Mainland, and I think To and Wai want to show how each has gone too far and both have become merciless and inhuman. Of course, in the end, China wins out and Hong Kong’s biggest pop star is on a table whimpering as China slips in the needle (which is weird, since I don’t think China uses lethal injection to execute people, but then again it’s an instance of Chinese drugs beating Hong Kong’s drugs).

Thanks to Grady for opening up this aspect of the film! And I’m sure the packed house that greeted Drug War during its screening at the New York Asian Film Festival thank him and his colleagues too.

Drug War, with Sun Honglei as Captain Zhang Lei.

Stretching the shot

Walker (2012).

It’s the editor’s job to think about coverage, and mistakes at this stage can have a very high price. Without that shot of the murderous feet walking slowly down the stairs, it’s impossible to build suspense. Inexperienced directors are often drawn to shooting important dramatic scenes in a single take—a “macho” style that leaves no way of changing pacing or helping unsteady performances.

Christine Vachon

DB here:

Go to any ambitious film festival, such as the Vancouver one Kristin and I are attending at the moment, and you’ll see several films made up of unusually sustained shots. Some Asian and European films may even be made entirely of long takes; in a few instances, none of the scenes may employ any editing at all. Movies made wholly of one-take scenes, or sequence-shots (plans-séquences) are probably more common today than they have been since 1920.

Why so many long takes? In the 1990s, when Vachon was writing, imitation and competition probably did come into play. The Movie Brats were sometimes up-front about their boy-on-boy rivalry. Here’s De Palma after seeing the shots following Jake into the ring in Raging Bull:

I thought I was pretty good at doing those kind of shots, but when I saw that I said, “Whoa!” And that’s when I started using those very complicated shots with the Steadicam.

Something similar may have been going on in earlier times. It seems to me that in 1940s Hollywood, directors came to a new consciousness of the long take. Preminger, Ophuls, Sturges, and Welles became famous for their sustained shots, and even Hitchcock, a long-time proponent of editing, switched sides, making some of the longest-take films of the era. Sometimes an action scene might be played out in one flamboyant take, as in The Killers and Gun Crazy. It does seem that these big boys appearing to compete to see how long they could hold their shots and how complicated they could make them. One scene in Welles’ Macbeth runs a full camera reel, or about ten minutes; Hitchcock’s Rope contains only eleven shots.

Yet I don’t think that macho showoffishness or competition can completely explain the urge to shoot long takes. Watching the Vancouver Dragons and Tigers series leads me to consider some other options.

Long view of the long take

Naniwa Elegy (1936).

Of course there were single-take movies at the beginning of cinema, as in Lumière’s documentary shorts. And in the period 1908-1920, as I’ve argued in many entries on this site, some great films were made relying on single-shot scenes. They operated with a staging-driven aesthetic that’s come to be known as the “tableau” style.

But with the rise of American cinema to international prominence, and worldwide directors’ willingness to create scenes in the process of editing, the long take became relatively uncommon. In the 1920s, a rapidly-cut film might make occasional use of a long take, often as a fairly intricate traveling shot, as in Murnau’s Sunrise and Vidor’s The Crowd. Early talkies sometimes began with a long tracking shot (e.g., Sunny Side Up, Scarface) before settling into a more editing-driven style. And a few directors in Western cinema, like Max Ophuls, Jean Renoir, and John Stahl, handled extended dialogue passages in a single shot. A long-take approach was somewhat more common in Japanese cinema, with of course Mizoguchi Kenji being a prime exponent in films like Naniwa Elegy, Sisters of Gion, and Genroku Chushingura.

Citizen Kane probably helped popularize the long take in the 1940s, but so did the development of new camera supports. Dollies that could move through a set in tight turns encouraged directors to try out more sustained shots. For such reasons, most long takes of the period involved camera movement. Although Welles had his share of flashy tracking shots, he was one of the few directors who also let the camera stay fixed in place throughout a scene, in both Citizen Kane (Toland emphasized its “single, non-dollying” shots) and the extraordinary kitchen scene of The Magnificent Ambersons.

Occasional long-take shots have been with us ever since, some of them highlighting balletic camera-actor staging, as in Antonioni’s bridge encounter in Story of a Love Affair and many interior shots of Le amiche. By the 1960s, and 1970s, some directors became identified with long takes and even single-shot sequences: Tarkovsky most famously, but also Straub and Huillet, Miklós Jancsó, and Theo Angelopoulos. Fassbinder tried it out occasionally (Katzelmacher) as did Wenders (Kings of the Road). And of course in the avant-garde, devastating half-hour shots marked some works by Andy Warhol, not your most macho filmmaker.

There are still long-take films being made in the mainstream—not only those motivated as scavenged recordings like Cloverfield or Paranormal Activity, but also ambitious experiments like Children of Men. On the whole, however, long-take technique has become a hallmark of festival cinema. As commercial directors (not just in Hollywood) has embraced ever-faster cutting, other filmmakers have pushed toward ever-longer takes. It’s as if the rise of what I’ve called intensified continuity has provoked filmmakers to go to the other extreme. This impulse is thrown into still sharper relief by the fact that many of these festival films use little camera movement. And today’s shooting on video lets you hold shots a lot longer than shooting on camera reels.

But what does long-take cinema buy you?

Dragons, tigers, and stillness

A Mere Life (2012).

This year’s Dragons and Tigers series, the festival’s panorama of recent Asian cinema, had its usual quota of young people’s films about young people, not unlike America’s Mumblecore. The kids hang out, smoke, drink, flirt, berate each other, sometimes humiliate one another, occasionally come to a crisis in their lives. Other films were a bit more unusual. Several of all types, though, pointed up the virtues and limitations of current approaches to long-take shooting.

Most low-budget directors employing long takes don’t do so out of bravado or competitiveness. The reasons are more mundane: the tactic saves time and money. If you have rehearsed your actors, or if you want spontaneity and improvisation, you can get through a lot of your film more efficiently if you simply record the action. Editing in post-production comes down to choosing your best takes and finding the best arrangement of them.

For instance, Ninomiya Ryutaro’s The Charm of Others has about fifty shots in its eight-five minutes. Most scenes consist of only one or two shots. One seven-minute shot shows a young layabout Sakata trying to jolly his girlfriend out of dumping him. She’s seen him with another girl and tells him, “Eat first, then we’re through.” Instead, he pokes and tickles her, makes faces and jokes about liking to eat hair, and eventually wins her back. It’s a nice little examination of how men turn boyish, even babyish, when they’re trying to avoid a woman’s wrath.

Ninomiya, who plays Sakata, explains that although he had each scene’s core action fully scripted, he let actors improvise a fair amount during shooting. (Some specific words, however, had to be used.) The girlfriend scene was shot four times, the first three developing one approach to the action and the fourth take trying a totally different approach. Ninomiya wound up using the third take.

The Charm of Others is shot in a loose handheld style, with panning and tracking to follow its characters. This “free camera” technique is probably the most common way off-Hollywood directors employ the long take. The approach was on display as well in Mine Goichi’s The Kumamoto Dormitory. The plot follows a pair of slackers who want to work in films but lack ambition and anything approaching realistic expectations. More editing-driven, and somewhat more slickly made than The Charm of Others, it still averaged about eleven seconds per shot, a far cry from contemporary Hollywood’s average of five seconds or less.

For the most part, The Kumamoto Dormitory uses long takes in traditional ways–to record a scene’s interactions, and sometimes to create parallel story situations. In the beginning a lengthy shot drifts along dorm corridors as kids are moving in. One later in the semester shows boys in each room masturbating, playing mahjongg or computer games, and otherwise goofing off. Near the end another traveling shot shows the boys packing to leave as we hear an admistrator’s public speech describing how dorm life brings beginning students and graduating ones closer together. His inspiring line, “You were brought into the world because you were needed,” becomes ironic in the light of the dead-end hopes of a would-be movie director and his pal, an aspiring stunt man.

More rarely, the camera can be locked off during the long take, creating a static setup that may be refreshed by slight pans and reframings. Two of the films I’ve discussed earlier, Romance Joe and In Another Country, exemplify this approach; the former has fewer than 200 shots, the latter fewer than seventy. A similar approach, with a little more emphasis on dramatic compositions, is taken in Park Sanghun’s A Mere Life, a movie not about twentysomething crises but about the failure of a man to provide security for his wife and child. In a somewhat Mizoguchian tale of misery, most scenes are covered in only one or two fixed shots. There’s a striking scene in a café which obliges us to scan the background when a con artist bilks the husband and flees with his money. At another point, the camera’s refusal to budge and the director’s refusal to cut create considerable tension. Soon after the husband has lost the family’s savings, walls block our view of his desperate attempt to kill his wife and child.

The static long take is used in a more transparent way in Luo Li’s Emperor Visits the Hell, the winner of the Dragons and Tigers competition. The curious premise is that characters in present-day China are reenacting an episode in the classic saga Journey to the West. The reenactment, moreover, isn’t an affair of costumes or combat. It’s more abstract. For instance, the Dragon King is decapitated in the original story, but the Triadish character playing him in this film strolls around with his head firmly in place.

There are few single-take scenes, but the starkness of the décor and the fact that characters tend to be planted in a single spot give the film a sense of ceremonial gravity enhanced by the precise choices of camera position. Only in an epilogue, during the production’s wrap party in a restaurant, do the cast and crew assume their everyday identities. Then the camera goes handheld and roams bumpily around the table.

By the end Emperor Visits the Hell becomes a collection of contemporary long-take options: fixed versus moving, rock-solid framing versus shakycam.

Time on our hands

The long take has, we’re often told, another purpose: to capture real duration. Editing, it’s said, fragments not only space but also time. Whenever you cut, you have the opportunity to skip over dead moments. With a long take, especially a static one, the filmmaker is in effect asking us to register all the dead time between more important gestures, expressions, or lines of dialogue. This happens again and again in The Charm of Others, The Kumamoto Dormitory, and most of the movies I’ve already mentioned.

But the assumption of that “real time” flows through the shot can be questioned. The most common counterexample is slow- or fast-motion, which doesn’t respect the actual duration of the action the camera records. A rarer instance is offered by Tsai Ming-liang’s episode Walker in the portmanteau project Beautiful 2012, sponsored by the Hong Kong International Film Festival Society.

The action is bare-bones: A Buddhist monk walks through Hong Kong bearing a crinkly plastic bag in one hand and a sweet bun in the other. Across twenty-four minutes, twenty-one shots trace his progress through the city. In most the camera never movies, capturing the monk’s movement in static, sometimes abstract compositions. The catch is that the monk, played by Tsai regular Lee Kang-sheng, is advancing with preternatural slowness.

Sometimes we have to play a sort of Where’s-Waldo game with the compositions, searching for his stooped head or brilliant red robe or bare feet in a crowded shot. Most often, the emphasis falls simply on the monk’s movement. Hands lifted, head bent, he makes his way as if walking underwater. We watch each foot lift, shift weight, and descend in excruciatingly small changes of position. The movement proceeds not from camera trickery or CGI gimmicks; Lee’s performance presents a “temporal close-up” of humble, unstoppable walking. Meanwhile traffic, passersby, and other parts of his surroundings bustle along as usual. This is really stretching the shot–making the long take seem even longer.

One effect of these shots is to unroll an image of pure spiritual discipline, a sort of Zen exercise showing how microscopically an adept can control his body. Pedestrian yoga, you might say. Another effect Tsai creates is to summon up two times in one shot: that of normal activity and that of a spiritual tempo nestled within, but also opposed to, ordinary life. Eventually, when the monk bites into the bun, even that is rendered with the clarity of stop-motion photography. Here the long take exercises an almost scientific force, letting us see a simple act pulverized, as if a Muybridge image were translated into live action.

At the opposite extreme is the action-packed long take, running about seventy-five minutes, that comprises J. P. Sniadecki and Libbie D. Cohn’s People’s Park. The filmmakers had the good idea of taking us through a day’s pleasure in the city park of Chengdu, China, by means of a single traveling shot. A modern version of People on Sunday, the film unrolls a pageant of the everyday. People snack, trot past, make cellphone calls, rest on benches, sketch calligraphy on the paving stones, and above all make music. We see band concerts, karaoke performances, traditional opera, and spontaneous dancing to pop beats. The film starts with couples dancing and ends with an exuberant display of bouncy soloists who, we learned from Libbie Cohn after the screening, come often to perform for the sheer fun of it.

Just as important, instead of shooting at eye level, Sniadecki and Cohn filmed from a wheelchair. The lower-than-normal framing emphasizes kids, fills the frame with torsos, and yields unexpected revelations of figures in depth. We also get to watch a choreography of politeness as people subtly adjust to the camera as it squeezes through crowds or sidles among couples on a dance floor. Far from being the weightless, invisible camera of most Hollywood films, this camera and its carriage occupy actual space as the whole unit carves a sinuous path through the park. How, we sometimes wonder, will it get through here?

Many of the most famous long takes in film history are, we might say, teleological: They build toward a climax. Think of the tracking shot that opens Touch of Evil, beginning with a bomb set ticking and ending with an explosion. In a quieter way, the tableau aesthetic of the 1910s often gave the shot a distinct curve of interest, building to an expressive peak. (See here and here.)

And occasionally in today’s cinema, a shot that seems casual will subtly prepare us for a payoff. In The Charm of Others, a drinking game allows Sakata to tell others around the table what they must do. He orders two boys to kiss, and the girls join him in chanting, “Kiss! Kiss!” Those boys have already been present from the start of the shot, but now they become more than a pair of framing shoulders. Their obeying the order close to us furnishes an enjoyable topper for the take.

One problem facing the makers of People’s Park was the need to provide such a climax. As in Russian Ark, a single-shot feature film can’t simply stop; it needs to draw to a close, preferably on a striking note. In my view, Sniadecki and Cohn manage it. It would be unfair to tip you off–can there be such a thing as a stylistic spoiler?–but let’s just say it’s a moment of abrupt change within what is otherwise continuous, evenly-paced unfolding. Yes, dancing is involved.

In certain contexts, a long-take trend can, as Vachon mentions, exude a certain bragadoccio. Competition among artists, though, even with some bravado, isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as 1940s and 1980s Hollywood suggests. Sometimes as well the long take is an exigency demanded by time and money. It can yield artistic advantages, too, by building suspense (as in A Mere Life) or surprise (as in The Charm of Others) or both (as in People’s Park). It can also be a mark of virtuosity, a quality prized in most artistic traditions. A well-done long take can be like a sustained aria in an opera; its confident audacity can make you smile.

The epigraph quotation is from Christine Vachon’s Shooting to Kill (Morrow, 1998); the passage is available here. My quotation from Brian De Palma comes from “Emotion Pictures: Quentin Tarantino Talks to Brian De Palma,” in Brian De Palma Interviews, ed. Lawrence F. Knapp (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2003), 148. I discuss stylistic competition in contemporary American film in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

I consider Mizoguchi’s use of the long take in Chapter 3 of Figures Traced in Light. Some elaboration of that chapter is on this site.

Toland’s explanation for avoiding cutting is explained in his essay “Realism for Citizen Kane,” available here. For more on his decision-making, see our book, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960, as well as this blog entry. For more on 1940s “fluid camera” technique, go here.

The segments of the film Beautiful 2012 began life as online videos. They are linked at Hong Kong Cinemagic. They play rather jerkily on my laptop, but the motion in projection is completely smooth.

My thanks to Tony Rayns and Shelly Kraicer, programmers of the Dragons and Tigers series, for their acumen and assistance.

People’s Park (2012).