Archive for the 'Film theory' Category

Invasion of the Brainiacs II

DB here:

What gives movies the power to arouse emotions in audiences? How is it that films can convey abstract meanings, or trigger visceral responses? How is it that viewers can follow even fairly complex stories on the screen?

General questions like this fall into the domain of film theory. It’s an area of inquiry that divides people. Some filmmakers consider it beside the point, or simply an intellectual game, or a destructive urge to dissect what is best left mysterious. Many readers consider it academic bluffing, another proof of Shaw’s aphorism that all professions are conspiracies against the laity.

These complaints aren’t quite fair. Early film theorists like Hugo Münsterberg, Rudolf Arnheim, André Bazin, and Lev Kuleshov wrote clearly and often gracefully. Even Sergei Eisenstein, probably the most obscure of the major pre-1960 theorists, can be read with comparative ease. Moreover, generations of filmmakers have been influenced by these theorists; indeed, some of these writers, like Kuleshov and Eisenstein, were filmmakers themselves.

But those day are gone, someone may say. Does contemporary film theory, bred in the hothouse of universities and fertilized by High Theory in the humanities, have any relevance to filmmakers and ordinary viewers? I think that at least one theoretical trend does, if readers are willing to follow an argument pitched beyond comments on this or that movie.

That is, film theory isn’t film criticism. Its major aim is more general and systematic. A theoretical book or essay tries to answer a question about the nature, functions, and uses of cinema—perhaps not all cinema, but at least a large stretch of it, say documentary or mainstream fiction or animation or a national film output. Particular films come into the argument as examples or bodies of evidence for more general points.

In about three weeks, about fifty people will gather at the University of Copenhagen to do some film theory together. It’s the annual meeting of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. I talked about the group last year (here and here) in the runup to our Madison event.

The sort of theorizing we’ll do, for all its variety, is in my view the most exciting and promising on the horizon just now. It’s also understandable by anyone interested in puzzles of cinematic expression, and it has powerful implications for creative media practice.

We’ll also be in Copenhagen for Midsummer Night, which is always pleasant. Go here for the lovely song that thousands of Danes will try to sing, despite terminal drunkenness. No real witches burned, however.

Concordance and convergence

But back to topic: Puzzles of cinematic expression, I said. What puzzles? Well, films are understood. Remarkably often, they achieve effects that their creators aimed for. Michael Moore gets his message across; Judd Apatow makes us laugh; a Hitchcock thriller keeps us in suspense. What enables movies to reliably achieve such regularity of response?

It’s not enough to say: Moore hammers home his points, Apatow creates funny situations, Hitchcock puts the woman in danger. Any useful explanation subsumes a single case to a more general law or tendency. So a worthwhile explanation for these cinematic experiences would appeal to more basic features of artworks, cultural activities, or our minds. We can pick up on Moore’s message because we know how to make inferences within certain contexts. We can laugh at a joke because we understand the tacit rules of humor. We recognize a suspenseful situation because… well, there are several suggestions.

This sort of question is largely overlooked by theorists of Cultural Studies, another area of contemporary media studies. They typically emphasize difference and divergence, highlighting the varying, even conflicting ways that audiences or critics interpret a film.

Studying how viewers appropriate a film differently is an important enterprise, but so is studying convergence. Arguably, studying convergence has priority, since the splits and variations often emerge against a background of common reactions. A libertarian can interpret Die Hard as a paean to individual initiative, while a neo-Marxist can interpret it as a skirmish in the class war, but both agree that John and Holly love each other, that her coworker is a weasel, and that in the end John McClane’s defeat of Hans Gruber counts as worthwhile. Both viewers may feel a surge of satisfaction when McClane, told by a terrorist he should have shot sooner, blasts the man and adds, “Thanks for the advice.” What enables two ideologically opposed viewers to agree on so much?

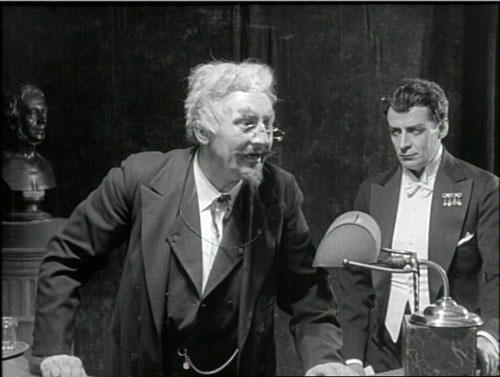

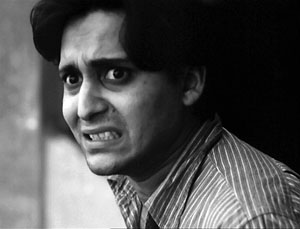

Films aren’t just understood in common; they arouse remarkably similar emotions across cultures. This is a truism, but it’s been too often sidestepped by post-1960 film theory. Who, watching The World of Apu, doesn’t feel sympathy and pity for the hero when he learns of the sudden death of his beloved wife? Perhaps we even register a measure of his despair in the face of this brutal turn of events.

We can follow a suite of emotions flitting across Apu’s face. I doubt that words are adequate to capture them.

Are these facial expressions signs that we read, like the instructions printed on a prescription bottle? Surely something deeper is involved in responding to them—for want of a better word, fellow-feeling. Indians’ marriage customs and attitudes toward death may be quite different from those of viewers in other countries, but that fact doesn’t suppress a burst of spontaneous sympathy toward the film’s hero. We are different, but we also share a lot.

The puzzle of convergence was put on the agenda quite explicitly by theorists of semiotics. Back in the 1960s, they argued that film consisted of more or less arbitrary signs and codes. Christian Metz, the most prominent semiotician, was partly concerned with how codes are “read” in concert by many viewers. Today, I suppose, most proponents of Cultural Studies subscribe to some version of the codes idea, but now the concept is used to emphasize incompatibilities. So many codes are in play, each one inflected by aspects of identity (gender, race, class, ethnicity, etc.), that commonality of response is rare or not worth examining.

A complete theoretical account, if we ever have one, would presumably have to reckon with both differences and regularities. The dynamic of convergence and divergence is a central part of one arena of film studies that has, for better or worse, been called cognitivism.

Sampling

Gathering for Uri Hasson‘s keynote lecture, SCSMI 2008.

The cognitive approach to media remains a pretty broad one, and the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image hosts a plurality of approaches at its annual meetings. SCSMI has become home to media aesthetes, empirical researchers, and philosophers in the analytic tradition who are interested in interrogating the concepts used by the other two groups. Last year’s gathering, at our campus here in Madison, created a lively dialogue among these interests.

For instance, some of us Film Studies geeks wonder why people so consistently ignore mismatched cuts. Dan Levin’s ingenious experiments on “change blindness” provide a hilarious rejoinder. In one study conducted with Dan Simons, a stooge asks directions of an innocent passerby. As they’re talking, a pair of bravos carry a plank between them, and another confederate is substituted for the first one.

You guessed it. Most subjects don’t notice that the person they’re talking to has changed into somebody else! So how can we worry about mismatched details in cuts? Actually, Dan’s research isn’t just deflationary. It helps spell out particular conditions under which change blindness can occur.

Another stimulating talk was offered by Jason Mittell. He asked how long-running prime-time TV serials can solve the problem of memory. In this week’s episode what strategies are available to recall the most relevant action of earlier episodes? How can previous action be presented without boring faithful fans? Jason, who has a new book on American TV and culture out this spring, went beyond describing the strategies. He suggested how they can become a new source of formal innovation, as in the Death of the Week in Six Feet Under.

Sermin Ildirar of Istanbul University presented the results of a study on adults living in a village in South Turkey. These viewers were older, ca. 50-75, and—here’s the interesting part—had never seen films or TV shows. To what extent would they understand “film grammar,” the conventions of continuity editing and point-of-view, that people with greater media experience grasp intuitively? To facilitate comprehension, the researchers made film clips featuring familiar surroundings.

The results were intriguingly mixed. Some techniques, such as shots that overlapped space, were understood as presenting coherent locales. But most viewers didn’t grasp shot/ reverse-shot combinations as a social exchange. They simply saw the person in each shot as an isolated figure.

The discussion, as you may expect, was lively, concerning the extent to which a story situation had been present, the need to cue a conversation, and the like. I found it a sharp, provocative piece of research. Stephan Schwan, who worked with Sermin and Markus Huff, has become a central figure studying how the basic conventions of cutting and framing might be built up on the basis of real-world knowledge, and both he and Sermin are back at SCSMI this year.

Stephan Schwan, Thomas Schick, Markus Huff, and Sermin Ildirar, with Johannes Riis in the background; SCSMI 2008.

There were plenty of other stimulating papers: Tim Smith’s usual enlightening work on points of attention within the frame, Johannes Riis on agency and characterization, Paisley Livingston on what can count as fictional in a film, Patrick Keating on implications for emotion of alternative theories of screenplay structure, Margarethe Bruun Vaage on fiction and empathy, and on and on.

One of the best things about this gathering was that the ideas were sharply defined and presented in vivid, concrete prose. I can’t imagine that ordinary film fans wouldn’t have found something to enjoy, and of course many of these matters lie at the heart of what filmmakers are trying to achieve. Indeed, some filmmakers regularly give papers at our conventions. The much-sought link between theory and practice is being made, again and again, in the arena of the SCSMI.

Last year I came to believe that this research program was hitting its stride. My hunch is confirmed by this year’s gathering in Copenhagen. The department of media studies there has long been a leader in this realm. You can download a Word version of the schedule here.

Lest you think that the conference participants don’t talk much about particular movies, I should add that there’s one film we’ll definitely be talking about this time around. Our Copenhagen hosts have arranged for a screening of von Trier’s Antichrist.

Next time: Going deeper into cognitivism, and three recent explorations.

Malcolm Turvey makes a point to Trevor Ponech and Richard Allen, SCSMI 2008.

Kristin and I have talked about pictorial universals elsewhere on this site. See her blog entry on eyeline matching in ancient Egyptian art, and my comments on “representational relativism” here.

Images at the top of this entry are taken from the Danish film Himmelskibet (The Space Ship, aka A Trip to Mars, 1918).

Getting real

Art is not reality; one of the damned things is enough.

Attributed to Virginia Woolf, Gertrude Stein, and others.

DB here, with another followup to Ebertfest:

Ebertfest, once known as the Overlooked Film Festival, has always been keen to support American independent filmmaking. In previous incarnations, Roger spotlighted Junebug, Tarnation, and other movies that flew below the multiplex radar. This year’s crop was especially ripe. Besides The Fall and Sita Sings the Blues, there were important documentaries like Begging Naked and Trouble the Water. In particular, two fiction features set me thinking about types of independent storytelling and how they might be considered realistic.

The river is wide

Roger noted that when he first saw Frozen River, he wanted to bring it to his festival, but then it became the very opposite of an overlooked movie. It has grossed $4.3 million worldwide, a very healthy amount for a small-budget film without big stars. It won eleven national awards and was nominated for fourteen others, including a Best Original Screenplay Oscar. By now, you’ve probably seen it. I had been away during its Madison run, so I was happy to catch up with it.

“You have five minutes to show the audience you’re in charge,” commented director Courtney Hunt in the Q & A, and her film follows that advice. Seconds into Frozen River, we hit a crisis. Ray finds that her no-good husband has grabbed their savings and taken off to gamble, even as she waits for the delivery of their new prefab home. What begins as a drama of pursuit, with Ray trying to track down her husband, turns into a blocked situation. He’s gone and she has to not only pay off their mortgage but also keep her two sons going, counting on their school lunches to offset their domestic meals of popcorn and Tang.

Drama is about choices, and good drama is about bad choices. Ray has clearly made her share of mistakes—addictive mate, kids she can’t support, a bigscreen TV she can’t afford—and the plot shows her making the biggest of all. To scrape together money she agrees to transport illegal immigrants from Canada to upstate New York, driving across the frozen St. Lawrence. She casts her lot with Lila Littlewolf, a Native American with her own bad choices, and their common fate creates a series of parallels about motherhood that are resolved through Ray’s final sacrifice. The film also activates some current concerns about immigration, racism, and the problems shared by poor whites and ethnic minorities.

Resolutely unHollywood in its setting, theme, and characters—deglamorized women, especially—Frozen River still adheres to classical script structure. We have characters with goals, encountering obstacles and entering into conflicts, and the turning points come at the standard junctures. The ending is a resolution, although not an entirely happy one. In the course of the plot, suspense is built up at many points. Will Ray and Lila be caught by the state troopers who grimly monitor their comings and goings? What will become of that abandoned baby? The film is a sturdy example of how classic principles of construction can be applied to subject matter that is worlds away from our prototype of Hollywood filmmaking.

Neo-neo and all that

Ramin Bahrani’s Chop Shop, which I was also just catching up with, offers another flavor of independent dramaturgy. Roger has been a staunch supporter of Ramin’s films since Man Push Cart, and he has declared him “the new great American director.”

Bahrani has mastered a somewhat different narrative tradition than the crisis-driven plotting of Frozen River. “Neo-neorealism,” A. O. Scott has called it, linking Goodbye Solo to Wendy and Lucy, Treeless Mountain, Old Joy, and other films that offer us an “escape from escapism.” Now, Scott suggests, American cinema is having its delayed Neorealist moment. Richard Brody offers some useful, sometimes scornful, qualifications of Scott’s conjecture, reminding us of the urban dramas of the 1940s and the rise of Method acting. Scott has replied, claiming that their dispute essentially depends on their differing tastes in movies.

Here’s my $.02. “Neorealism” isn’t a cinematic essence floating from place to place and settling in when times demand it. The term, like the films it labels, emerged under particular circumstances, and it’s hard to transfer the label to other conditions. Moreover, there are many problems just with applying the term to Italian cinema, since it tends to cover not only the purest cases, like Bicycle Thieves, but also more mixed ones like the historical drama The Mill on the Po.

Still, because postwar Italian cinema had a big influence on other national cinemas, we have a prototype of The Italian Neorealist Movie. The filmmaker focuses on the lives of working people. He emphasizes their daily routines and travails. The film will be shot on location (at least in the exteriors) and may use nonactors in some or all roles. Bazin pointed out that we’re likely to find an elliptical or unresolved plot. It’s also very likely that we’ll see washlines and women in slips.

Why not just call this an Italian variant of that broad tradition of naturalism or verismo or “working-class realism” that we find in many national cinemas? In France there was the work of Andre Antoine (e.g., La Terre, 1921) and Jean Epstein’s Coeur fidele (1923) and his lyrical barge romance La Belle Nivernaise (1923). More famous are Renoir’s Toni (1935) and The Lower Depths (1936). (Recall that Visconti was Renoir’s assistant on A Day in the Country, 1936.) In Italy, there were harbingers too, not only the famous ones like Four Steps in the Clouds (1942) but also the charming Treno Popolare (1933). And Japan gave us many instances in the 1930s, notably Ozu’s Inn in Tokyo (1935) and The Only Son (1936).

Realer than real

On an Ebertfest panel Ramin Bahrani argued for a realist aesthetic. “Most people in movies never seem to pay rent or keep track of how often they can eat out . . . [Ordinary people] have day-to-day struggles; they ask how to survive.” That’s to say that a realistic work is distinguished primarily by its subject matter, the social milieu it presents. Bahrani also mentioned that some plot devices are unrealistic. Criticizing Slumdog Millionaire, he remarked: “My world doesn’t end in a Hollywood fantasy.” He didn’t deny the need for a dramatic structure, but he did insist on avoiding “obvious plot points like ‘He crossed the door and can’t go back.’”

This leads me to another $.02 contribution. I’m reluctant to contrast realism with something like artifice or formula. To me, realism comes in many varieties, but none escapes artifice. All realisms I know rely on conventions shaped by tradition.

For example, Chop Shop shows us a slice of life that most of us don’t know, the world of garages and salvage yards clustered around Shea Stadium. Such a low-end milieu is a convention of literary naturalism (Zola, Gorki). In this tradition, an artwork acknowledging the lives of the poor gains a dose of realism that, say, a novel by P. G. Wodehouse or a play by Noël Coward will lack. Some critics complained that when Rossellini’s Europa 51 and Voyage to Italy presented upper-class life, he left Neorealism behind.

There seem to me other conventions at work in Chop Shop. In one garage we find a boy, Alejandro, who has two goals. He wants to set up a food van that will sell meals to the men working in the neighborhood, and he wants to keep his sister Isamar safe from bad companions. Goal-driven plotting is central to Hollywood dramaturgy, as it is to much literary realism (e.g., An American Tragedy). It’s true that in real life people often form goals, but many do not, and those who do seldom come to a state of heightened awareness in the time frame typical of a movie’s plot. Alejandro fails to achieve one goal but partially achieves another, so we have an open, somewhat ambivalent ending—another convention of realist storytelling and modern cinema (especially after Neorealism). Life goes on, as we, and many movies, often say.

Instead of following a crisis structure, as Frozen River does, Chop Shop presents what we might call “threads of routine.” Most scenes consist of ordinary activities: the work of the garage, Alejandro’s sales of candy and DVDs, opening and closing the shop, Alejandro watching from the window of his room. But these vignettes aren’t sheer repetitions. They vary as Alejandro encounters progress or setbacks with respect to his goals. Most of the routines establish a backdrop against which moments of change and conflict will stand out.

Building a movie out of routines can also make convenient coincidences seem plausible. For instance, dramas have always relied on accidental discoveries of key information—the overheard conversation, the token that betrays what’s really happening. In Chop Shop, Ale and his pal Carlos discover that Isamar has become one of the hookers who service men in the cab of a tractor-trailer. They might have discovered this, as in life, by simply wandering by the spot on a single occasion. Instead, Bahrani’s script motivates their discovery by explaining that they habitually spy on the truck assignations. “Let’s go to the truck stop and see some whores.” Planting information in scenes of everyday activities seems more natural than giving it special emphasis at a moment of crisis. In two later scenes, the truck-stop becomes an arena for conflict, so Ale’s initial discovery motivates his later actions.

As for plot points, Chop Shop has them. (At about 15 minutes, the zone of the Inciting Incident, Ale declares his intention to buy the van. At about 30 minutes he discovers that Isamar is turning to prostitution.) Likewise, the threaded routines yield poetic motifs, such as the pigeons that are carefully established early in the film. Bahrani’s plotting is meticulous, and it highlights the paradox of realism: It takes effort and calculation to “capture reality.” De Sica was said to have endlessly rehearsed the boy in Bicycle Thieves.

What gives the film a more episodic organization than Frozen River, I think, and what gives it a greater sense of “dailiness,” is that it lacks deadlines. There’s relatively little time pressure on the action, except for Ale’s sense that he’s getting close to having enough money for the van. Chop Shop’s refusal of Hollywood’s ticking clock seems to me to confirm the observation, made by Geoff Andrew and J. J. Murphy, that in some respects American indie film is located midway between classical narrative cinema and “art cinema.”

The threads-of-routine pattern can be harnessed to character-driven drama, as in Chop Shop, but it can also be more opaque or minimalist. During at least half of Elia Suleiman’s Chronicle of a Disappearance, we watch anonymous characters go through routines, but instead of revealing their psychological drives, the scenes show the people overwhelmed by their surroundings. Narrative development is charted through changes in the spaces that the figures inhabit and vacate. The result is a “surreal realism” that evokes the anxieties of Magritte or de Chirico.

To say that realist traditions rely on conventions doesn’t make them less worthwhile. Chop Shops seems to me quite a good film. Nor would I deny that realist conventions do capture some aspects of real life. Both the crisis structure and the threads-of-routines structure can be taken as realistic. Sometimes our lives are in crisis, and at other times we do just plod along. But more stylized narrative forms can capture important aspects of reality too. The Searchers, a work of high artifice, renders a portrait of a self-destructive racist that many of us recognize in the world outside the movie house. Has any film better caught the adolescent yearning for romantic love and family stability than Meet Me in St. Louis?

The problem comes when we think that only one variant of realism can lay claim to validity, let alone beauty. Sometimes fidelity takes a back seat to vivacity. In Roy Andersson’s films, everyday nuisances like checking in to a plane flight or waiting in a clinic are inflated to grotesque, gargantuan proportions, becoming torments in a vision of hell. Like all caricatures, the exaggeration captures something true.

Comparing Wilkie Collins and Dickens, T. S. Eliot notes that both writers give us vivid characters. Collins’ characters are “painstakingly coherent and life-like,” terms of praise that we could assign to Bahrani’s films as well. But, Eliot adds, “Dickens’ characters are real because there is no one like them.”

What was Neorealism? Some of André Bazin’s invaluable essays on the subject can be found in What Is Cinema? vol. 2 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971). Kristin and I offer a survey of some historical factors in Chapter 16 of Film History: An Introduction. (Go here for a little bibliography.) For more on art cinema and its commitments to realism and open endings, see my essay, “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice,” in Poetics of Cinema, 151-169. On American indies’ borrowing of art-cinema conventions, see Geoff King, American Independent Cinema (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005) and J. J. Murphy, Me and You and Memento and Fargo (New York: Continuum, 2007). J.J. also has a blog entry on Chop Shop here. The quotations from T. S. Eliot come from “Wilkie Collins and Dickens,” Selected Essays (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1950), 410-411.

Songs from the Second Floor (Roy Andersson, 2000).

Books, an essential part of any stimulus plan

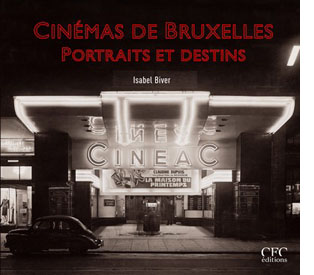

The Pathé Palace theatre, Brussels, designed by Paul Hamesse.

DB here:

Some shamefully brief notes on new publications. Disclaimer: All are by friends. Modified disclaimer: I have excellent taste in friends.

You call me reductive like that’s a bad thing

It’s easy to see why we might tell each other factual stories. We have an appetite for information, and knowing more stuff helps us cope with the social and natural world. We can also imagine why people tell fictitious stories that we think are true. Liars want to gain power by creating false beliefs in others. But now comes the puzzle. Why do we spend so much of our time telling one another stories that neither side believes?

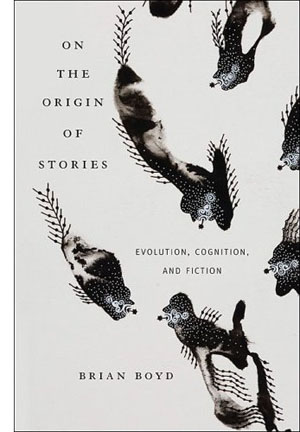

Brian Boyd’s On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction (Harvard University Press) is the first comprehensive study of how the evolution of humans as a social, adaptively flexible species has shaped our propensity for fictional narrative. The book is a real blockbuster, making use of a huge range of findings in the social and biological sciences. Brian paints a plausible picture, I believe, of the sources of storytelling. Along the way he shows how two specimens of fiction, The Odyssey and Horton Hears a Who, exemplify the richness and value of make-believe stories.

Brian Boyd’s On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction (Harvard University Press) is the first comprehensive study of how the evolution of humans as a social, adaptively flexible species has shaped our propensity for fictional narrative. The book is a real blockbuster, making use of a huge range of findings in the social and biological sciences. Brian paints a plausible picture, I believe, of the sources of storytelling. Along the way he shows how two specimens of fiction, The Odyssey and Horton Hears a Who, exemplify the richness and value of make-believe stories.

The standard objection to an evolutionary approach to art is that it’s reductive. It supposedly robs an individual artwork of its unique flavor, or it boils art-making down to something it isn’t, something blindly biological. Art is supposed to be really, really special. We want it to be far removed from primate hierarchies, mating behavior, or gossip. For a typical criticism along these lines, see this review of Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct. Brian has already adroitly responded to this sort of complaint here. See also Joseph Carroll’s examination of reductivism on his site.

It seems to me that all worthwhile explanations are reductive in some way. They simplify and idealize the phenomenon (usually known as “messy reality”) by highlighting certain causes and functions. This doesn’t make such explanations inherently wrong, since some questions can be plausibly answered in such terms. For example, often the literary theorist is asking questions about regularities, those patterns that emerge across a variety of texts. That question already indicates that the researcher isn’t trying to capture reality in all its cacophony. (For me, it’s all about the questions.)

Literary humanists sometimes talk as if they want explanations to be as complex as the thing being explained. But that would be like asking for the map to be as detailed as the territory. In fact, however, humanists tacitly recognize that explanations can’t capture every twitch and bump of the phenomenon. Consider some types of explanations that are common in the humanities: Culture made this happen. Race/ class/ gender / all the above caused that. Whatever the usefulness of these constructs, it’s hard to claim that they’re not “reductive”—that is to say, selective, idealized, and more abstract than the movie or novel being examined. Likewise, when people decry evolutionary aesthetics for its “universalist” impulse, I want to ask: Don’t many academics take culture or the social construction of gender to be universals?

I want to write more about Brian’s remarkable book when I talk about our annual convention of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. For now, I’ll just quote Steven Pinker’s praise for On the Origin of Stories: “This is an insightful, erudite, and thoroughly original work. Aside from illuminating the human love of fiction, it proves that consilience between the humanities and sciences can enrich both fields of knowledge.”

Faded beauties of Belgium

In its day, Brussels played host to some fabulous picture palaces. Now after years of research Isabel Biver has given us a deluxe book, Cinémas de Bruxelles: Portraits et destins. It’s the most comprehensive volume I know on any city’s cinemas.

Isabel glides backward from contemporary multiplexes and tiny repertory houses to the grandeur of the picture palaces. The Eldorado was a blend of Art Deco style and quasi-African motifs sculpted in stucco. King Albert graced the opening in 1933. There was the Variétés, a multi-purpose house built in 1937. It had rotating stages, air conditioning, and space for nearly 2000 souls (cut back to a thousand when Cinerama was installed). It was, Isabel claims, the first movie house in the world to be lit entirely by neon.

Isabel glides backward from contemporary multiplexes and tiny repertory houses to the grandeur of the picture palaces. The Eldorado was a blend of Art Deco style and quasi-African motifs sculpted in stucco. King Albert graced the opening in 1933. There was the Variétés, a multi-purpose house built in 1937. It had rotating stages, air conditioning, and space for nearly 2000 souls (cut back to a thousand when Cinerama was installed). It was, Isabel claims, the first movie house in the world to be lit entirely by neon.

Then there was the Pathé Palace, shown at the top of this entry. Dating back to 1913, it boasted 2500 places and included cafes and even a garden. This imposing Art Nouveau building was designed by Paul Hamesse, probably the city’s most inspired theatre architect. Hamesse also created the Agora Palace, which opened in 1922. Huge (nearly 3000 seats), the Agora was one of the most luxurious film theatres in Europe.

And we can’t forget the Métropole, the very incarnation of the modern style. Sinuous in its Art Deco lines, it packed in 3000 viewers. When it opened in 1932, it attracted nearly 53,000 spectators during its first week. The neon on the Métropole’s façade lit up the night, and its two-tiered glassed-in mezzanine became as much a spectacle as the films inside. See the still at the bottom of this earlier entry of mine. A ghost of its former self still sits on the Rue Neuve. Local historians consider the failure to preserve the Métropole a scandal in the city’s architectural history.

Cinémas de Bruxelles is a model presentation of local theatres. Not only does it trace the history of the major houses, but it includes a glossary of terms, a large bibliography, and an index of all theatres, both central and suburban. Needless to say, it is gorgeously illustrated. Whether or not you read French, I think you would enjoy this book, for it evokes an age we’re all nostalgic for, even if we didn’t live through it.

A TV interview with Isabel in French is here, with glimpses of what remains of the Métropole. She also gives guided tours of the remaining cinemas in the city center and in the neighborhoods. More information here.

A guy named Joe

Tropical Malady.

It’s seldom that a young filmmaker gets a hefty book devoted to him. Apichatpong Weerasethakul (aka Joe) will turn forty next year. He comes from Thailand, not a country adept at negotiating world film culture, and he is known chiefly for only four features. Yet he has become one of the most admired filmmakers on the festival circuit. His films are apparently very simple, usually built on parallel narratives. They have a relaxed tempo, exploiting long takes, often shot from a fixed vantage point, and scenes whose story points emerge very gradually. Joe’s movies tease your imagination while captivating your eyes. Each one could earn the title of his first feature: Mysterious Object at Noon.

It’s appropriate, then, that the tireless Austrian Film Museum has published a lavish collection of critical studies. Edited by James Quandt, the anthology arrives along with a massive retrospective of the director’s work, which includes many short documentaries and occasional pieces.

It’s appropriate, then, that the tireless Austrian Film Museum has published a lavish collection of critical studies. Edited by James Quandt, the anthology arrives along with a massive retrospective of the director’s work, which includes many short documentaries and occasional pieces.

James’ introductory essay, as evocative and eloquent as usual, is virtually a monograph, discussing all the features in depth. Alongside it are discerning essays by other old hands. Tony Rayns offers his usual incisive observations, focusing largely on Joe’s short films and the recurring imagery of hospitals, while Benedict Anderson surveys the Thai reception of Tropical Malady. Karen Newman offers precious information and judgments about Joe’s installations. The director himself signs several essays and participates in interviews and exchanges. Even Tilda Swinton has something to say.

I remember when Mysterious Object at Noon played the Brussels festival Cinédécouvertes in 2000. I was baffled. Joe’s movies taught me to watch them, and finally with Syndromes and a Century I got in sync. Its austere lyricism, off-center humor, and patiently unfolding echoes win me over every time I see it. (You can search this blogsite for several mentions, but JJ Murphy has a fuller appreciation of Syndromes here.) Thanks to Alexander Horwath and his colleagues for making this wonderful anthology, decked out with color stills and rich bibliography and filmography, available to us—and in English.

Zap goes the Chazen

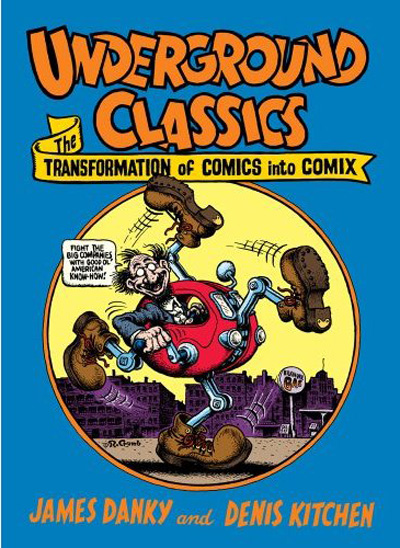

Zap, Snarf, Subvert, Young Lust, Tits & Clits, Air Pirates Funnies, Slow Death Funnies, Feds ‘n’ Heads, Corn Fed Comics, Dope Comix, Cocaine Comix, Corporate Crime Comics: The names define the era. The sixties didn’t end until the mid-1970s, and these outrageous cartoon books really came into their own after the election of Nixon in 1968.

On 2 May, the Chazen Museum on our campus launches its exhibition, Underground Classics: The Transformation of Comics into Comix, 1963-1990. A whirlwind of events, including films and lectures, will revolve around galleries full of imagery from the demented pens of Kim Deitch, Aline Kominsky Crumb, Trina Robbins, Gilbert Shelton, Robert Crumb, Bill Griffith, and many other cartoonists.

The show was originated by Jim Danky, a scholar of public media from our State Historical Society, and Denis Kitchen, comic artist and the publisher of Kitchen Sink Press here in Wisconsin. Jim has long argued for the archival value of minority and subcultural publications. He started our Center for Print Culture and has been an advocate for gathering print materials by and for children, women, and ethnic minorities. He virtually created the area of “alternative library journalism”—collecting obscure publications from all zones of the political spectrum. I recall his satisfaction in telling me that he had managed to acquire a collection of The War Is Now!, the radical Catholic newsletter published by Hutton Gibson, father of Mel.

The show was originated by Jim Danky, a scholar of public media from our State Historical Society, and Denis Kitchen, comic artist and the publisher of Kitchen Sink Press here in Wisconsin. Jim has long argued for the archival value of minority and subcultural publications. He started our Center for Print Culture and has been an advocate for gathering print materials by and for children, women, and ethnic minorities. He virtually created the area of “alternative library journalism”—collecting obscure publications from all zones of the political spectrum. I recall his satisfaction in telling me that he had managed to acquire a collection of The War Is Now!, the radical Catholic newsletter published by Hutton Gibson, father of Mel.

For some years Jim has been telling me about his efforts to mount the comix show. It’s no small matter to collect this elusive material and then persuade a museum to show it. Not too many galleries feature talking penises, Jesus visiting a faculty party, or Mickey and Minnie robbed at gunpoint by a dope dealer. Maybe we forget, in the age of the Web and The Onion, just how scabrous these things looked forty years ago. Actually, they still look scabrous. They also look pretty funny, and they’re often well-drawn. As a historical codicil, the exhibition includes 1980s images from artists extending the tradition, such as Drew Friedman and Charles Burns.

The show runs until 12 July 2009. If you can’t get to town, there’s the splendid catalogue. It includes essays by Jim and Denis, Jay Lynch, Patrick Rosenkranz, Trina Robbins, and Paul Buhle. There are free screenings of Fritz the Cat and Crumb at our Cinematheque. And you can read an interview with Jim about the show here.

Remember our motto: Lotsa pictures, lotsa fun.

Up next: Days and nights at Ebertfest.

The Eldorado Cinema, Brussels, designed by Marcel Chabot.

Color, shape, movement . . . and talk

Bonjour Tristesse.

DB here:

Our weekly Film Colloquium is sort of like your old high-school assembly, except that it’s fun. The Film Studies area meets nearly every Thursday afternoon at 4 to hear a paper by a grad student, a faculty member, or a guest. It’s a great forum for ideas and information, and it gives the speaker a chance to try out a talk before taking it to a conference or lecture gig. The local audience is, in my experience, the toughest I’m likely to encounter. And this spring, despite a heavy travel and work schedule, Kristin and I caught two outstanding presentations.

Not in color, but colored

By now we all understand that silent films were most often shown with musical accompaniment, and sometimes sound effects. But we tend to forget that most silent films were in color too.

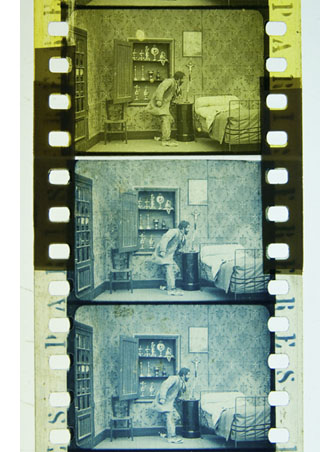

By the early 1920s, 80% of films were colored in one way or another. There were a few efforts to record the actual colors in a scene, but most often color was added after filming. Areas of the frame might be painted over by stenciling or by freehand. More commonly, the shots were dipped into dyes, yielding images that were tinted (washing over the image and coloring the areas of white, as in the frames below) or toned (coloring the darkest areas and leaving the white areas white). Over the years, film prints were preserved in black and white, partly because color stock was more expensive than today. As a result, even archival prints lost the sense of what audiences actually saw. Today archivists labor to reconstruct what silent films looked like in all their rainbow glory.

Professor Joshua Yumibe of Oakland University wrote his Ph. D. thesis on early color processes, and his Colloquium talk asked some powerful questions. We know that there was a transition in film artistry from the late 1900s to the early 1910s, a shift toward what Tom Gunning has called the “cinema of narrative integration.” As films became longer and were shown in more or less permanent venues, moviemakers began to tell more complicated stories. How, Josh asks, did this shift away from a cinema of isolated “attractions” affect practices of coloring? Do color processes affect the way stories were told? Do the color processes change how people saw the space on screen? How did the trade press respond to different strategies of coloring?

Professor Joshua Yumibe of Oakland University wrote his Ph. D. thesis on early color processes, and his Colloquium talk asked some powerful questions. We know that there was a transition in film artistry from the late 1900s to the early 1910s, a shift toward what Tom Gunning has called the “cinema of narrative integration.” As films became longer and were shown in more or less permanent venues, moviemakers began to tell more complicated stories. How, Josh asks, did this shift away from a cinema of isolated “attractions” affect practices of coloring? Do color processes affect the way stories were told? Do the color processes change how people saw the space on screen? How did the trade press respond to different strategies of coloring?

These are fascinating questions, and Josh’s exploration of them was careful and detailed. He has done enormous research on the various color processes, and he was able to trace several lines of development. For instance, he found that writers of the earliest years thought that color enhanced the sensual and emotional effects of the image, even creating an illusion of 3-D. In a shot like that of the butterfly dancer, people seem to have sensed that her multicolored shape was thrusting out of the screen toward them.

Josh argues that with the growing emphasis on narrative, color became more muted. Filmmakers were no longer aiming at momentary stimulation but at ongoing mood. Now tinting and toning came into their own. Color codes developed: blue for night scenes, yellow for sunlight, red for fire, amber for artificial light. Josh also explored the different ways in which European and US companies conceived of color; there seem to have been different color policies at Pathé and at American companies. But this wasn’t the end of change. In the 1920s, with the feature film now at the center of the theatre program, a wide variety of color practices emerged, including those isolated Technicolor sequences we find in films like The Wedding March.

The Q & A was as lively as the talk itself, and afterward, we repaired to a bar and thence to dinner. Josh’s talk was a model of deep, imaginative research and it kept us thinking and talking for a long time afterward. Not to mention his slide show, which regaled us with gorgeous shots that make you realize how much you’re missing when you see an old movie in black and white.

Bass, o profondo!

Another stimulating Colloq session was presided over by our old friend Jan-Christopher Horak, director of the UCLA Film and Television Archive. Chris was in town because our Cinematheque has been showcasing UCLA archival restorations across the semester, and he introduced our screening of The Dark Mirror. But we also got him to give a talk, and that was quite something.

Chris reminded me that we first met thirty years ago, here in Madison, when he came to do research on his dissertation. Since then Chris has been a top-flight scholar and author of many books. His Lovers of Cinema, published by our series at the UW Press, laid the groundwork for the popular film series Unseen Cinema. He’s also been one of the world’s leading film archivists, having supervised collections at Eastman House, the Munich Film Archive, Universal studios, and most recently UCLA.

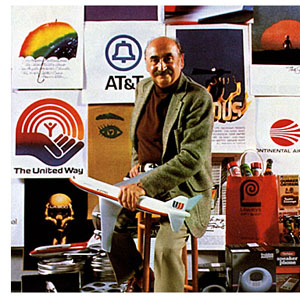

Chris has long worked at the intersection of film, photography, and the graphic arts. He is one of the world’s experts on the 1920s German avant-garde; one of his early curatorial coups was a 1979 restaging of the pioneering Film und Foto exhibition of 1929. Chris has also long been fascinated by film publicity, having written a book on the subject. So it’s natural that he would gravitate toward studying the film-related work of Saul Bass, one of America’s greatest graphic designers.

Chris’s talk focused not so much on Bass’s brilliant credit sequences for films by Preminger and Hitchcock as on Bass’s contributions to poster design. Bass turns out to have had a fascinating career, having worked in Manhattan advertising before moving to Los Angeles in 1948. Chris has found at least one early 1950s poster design that Bass probably executed, but he definitely worked for Preminger on publicity for The Moon Is Blue (1953) and Carmen Jones (1954)—the latter yielding to my mind one of the greatest credit sequences in film history. In 1955 Bass founded his own firm.

Chris’s talk focused not so much on Bass’s brilliant credit sequences for films by Preminger and Hitchcock as on Bass’s contributions to poster design. Bass turns out to have had a fascinating career, having worked in Manhattan advertising before moving to Los Angeles in 1948. Chris has found at least one early 1950s poster design that Bass probably executed, but he definitely worked for Preminger on publicity for The Moon Is Blue (1953) and Carmen Jones (1954)—the latter yielding to my mind one of the greatest credit sequences in film history. In 1955 Bass founded his own firm.

Throughout, he carried on the ideals of György Kepes, his teacher and a major conduit for Bauhaus ideas into America. Like his European models, Kepes promoted the idea of art as having cognitive value, teaching us to see the world in a new way. Kepes also emphasized that artworks could be of practical utility—an idea that chimed with Bass’s turn toward commercial design.

Chris was able to show that the Bauhaus tradition powerfully influenced Bass’s design principles. Who would have thought that the credits for The Seven Year Itch replayed Paul Klee? Obvious, though, when Chris showed us the images.

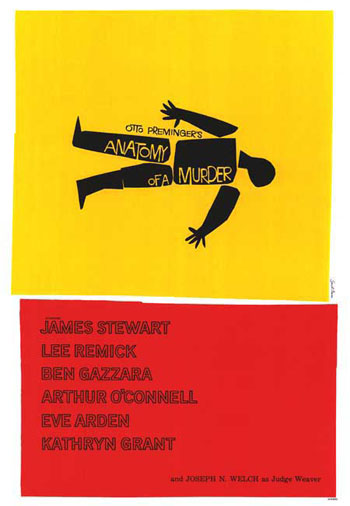

Chris emphasized two further points. First, Bass understood what we now call branding. We have to remember that it up to that time, most film publicity featured images of the stars, either in portraits or caught in typical scenes from the film. Bass’s poster design concealed the stars. Instead, he relied on dynamic geometrical design to capture a film’s mood in a powerful, stylized image. The result was an eye-catching logo, instantly recognizable: the flaming rose of Carmen Jones, the Vertigo whirlpool, the dismembered body of Anatomy of a Murder.

The key image could be repeated in newspaper ads, posters, credits, even the production company’s letterhead. When you saw the teaser trailer for Star Trek (“Under Construction”) dominated by that looming boomerang shape, you saw the heritage of Saul Bass. Who cares who’s in the movie? The very image is intriguing. No accident that Bass also designed many corporate logos, like the ATT bell and the United Way hand.

Chris’s second main point was that Bass was able to flourish because of the rise of independent production in the 1950s. Preminger, Hitchcock, and Wilder, acting as their own producers, could control the publicity for their films to a degree not possible for directors working in the classic studio system. Now films were sold as one-offs, and each film needed to pull itself above the clutter. In addition, Bass’s signature designs could set a director apart. In the 1950s, the Bass look was closely identified with his major clients like Hitchcock and Preminger, to the point that other designers for those directors tried to copy his style. I had always thought that Bass did the title design for Hurry Sundown, but Chris showed that it’s another artist’s pastiche of the master.

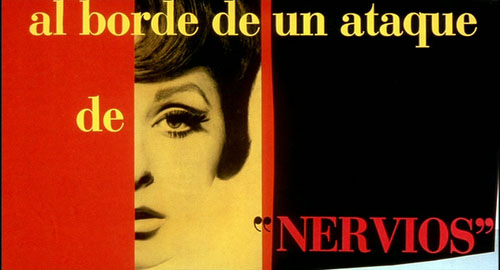

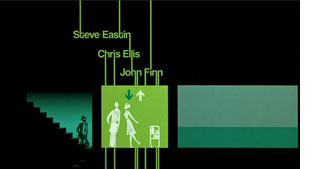

Chris’s talk reminded me that Bass contributed to making the opening credits a major attraction—not merely an overture, but an abstract treatment of the key story idea, a sort of graphic map that teases us into the main story. The opening sequences of Se7en and Catch Me If You Can (left) owe a lot to Bass’s idea that the credits should constitute a little movie, witty or ominous, tantalizing us with sketchy glimpses of what is to come. And Almodóvar’s diverting openings, probably the most sheerly enjoyable credit sequences we have today, are unthinkable without Bass. Synchronized with infectious music, Bass’s credit sequences can be seen as continuing the tradition of Walter Ruttmann and Oskar Fischinger, who back in the 1920s and 1930s made abstract films that advertised consumer goods.

Chris’s talk reminded me that Bass contributed to making the opening credits a major attraction—not merely an overture, but an abstract treatment of the key story idea, a sort of graphic map that teases us into the main story. The opening sequences of Se7en and Catch Me If You Can (left) owe a lot to Bass’s idea that the credits should constitute a little movie, witty or ominous, tantalizing us with sketchy glimpses of what is to come. And Almodóvar’s diverting openings, probably the most sheerly enjoyable credit sequences we have today, are unthinkable without Bass. Synchronized with infectious music, Bass’s credit sequences can be seen as continuing the tradition of Walter Ruttmann and Oskar Fischinger, who back in the 1920s and 1930s made abstract films that advertised consumer goods.

For such reasons, I’m glad I hung around Madison after my retirement. With visiting researchers like Josh and Chris, who wants to go fishing?

Woman on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown.

Thanks to Joshua Umibe for the silent-film illustrations. The first comes from Gaston Velle, Métamorphoses du Papillon / A Butterfly’s Metamorphosis (Pathé, 1904). Frame enlargement from Discovering Cinema (di. Eric Lange and Serge Bromberg, Lobster Film/Flicker Alley). The second comes from Albert Capellani’s Le Chemineau / The Vagabond (Pathé, 1905; tinted and toned). Frame enlargement Joshua Yumibe, courtesy of the Netherlands Filmmuseum.