Archive for the 'Film genres' Category

Vancouver envoi: What happens in movies happens between your ears

Summer 85 (2020).

DB here:

One of the nicest things anybody ever said to me came from Jacques Aumont, the distinguished French film scholar. He was visiting us in the early 1980s and I showed him a book manuscript I had just sent to the publisher. He read the first three chapters and said, “You remind us of something important. The spectator is thinking.” The book eventually came out as Narration in the Fiction Film.

In emphasizing that the spectator thinks, at least a little, I was driven to pay special attention to openings. The opening is where a film sets up information about its story world, about the action that will take place in it. We usually call this exposition. But a film also attunes us to the how as well as the what: how the story will be told. Exposition, in other words, includes introducing us to the characters and their situation but also to the ways we’ll learn about them. In the book I called the latter the “intrinsic norms” of narration.

But exposition isn’t simply a part of the plot, a chunk of opening material we need to digest. Exposition, the narrative theorist Meir Sternberg shows, is a process. In revealing what we call “backstory,” circumstances that predate the first scenes we see, exposition can go on throughout a film. (Kristin talks about this in her entry on Inception, and in revised form in our Nolan book.) So it turns out that the spectator has to keep thinking, keep reevaluating what’s being told about the story world and the way the story is told.

Three films showcased at the Vancouver International Film Festival set me thinking about these matters. Two depended on surprises, and these stemmed from the way exposition was handled. The third had very sparse exposition, asking us to gradually fill in story background through drifts and whiffs of information. In all cases, our enjoyment depends on thinking.

Surprise!

Bettina Oberli’s My Wonderful Wanda updates the ingredients of classic bourgeois comedy for the modern world of migratory caregivers. Josef and Elsa Wegmeister-Gloor oversee their pampered and confused son and daughter. Into the household comes a servant who is exploited for sexual favors by the old man. Wanda, the nurse brought in from Poland, is today’s equivalent of the chambermaid lusted after by both father and son.

As in most domestic comedies of class relations, Wanda the worker is no fool. Her duties help support her father, mother, and sons back home, and she proves herself a shrewd negotiator from the start. When Elsa asks her to perform extra chores, she demands more money. And when Elsa’s stroke-felled husband is willing to pay for sex, she agrees. Their secret bargain will, in good farce fashion, come to light in the most embarrassing way possible.

I went into the film knowing much less of the plot than I’ve just told you, so I want to keep back the rest. (Alas, the trailer overshares.) I was able to appreciate the way that Oberli’s tight script kept the surprises coming. Her script finds an admirable balance between clear structure and unpredictable turns.

Here the exposition is, in Sternberg’s terms, mostly concentrated and preliminary. The early scenes fill us in on the basic situation. Wanda is among several women met at the bus by Elsa. This is a compact way to suggest how much this class depends on the arrival of emigrant labor. Wanda is then taken to the family’s sumptuous villa. We learn about the situation as she does, and this introductory stretch culminates in Wanda’s introduction to her cramped basement room. In good traditional fashion, the exposition quickly encourages us to sympathize with the protagonist by showing her treated unfairly. On the basis of the information we get, the film’s first “act” becomes a tensely rising action in which Wanda becomes victimized by the petty conflicts that wrack the family.

A second long section begins in a lighter key, with the dismissed Wanda returning after some months, in a scene parallel to the opening. This chunk provides another concentrated dose of information, bringing us up to date on the family’s situation. Comic complications emerge when the family has to cope with a new, more pressing set of demands.

In good Renoirian fashion, Oberli gives everyone a dose of sympathy. The frailties of the son and daughter get nuanced and softened, and we see this coddled pair as less selfish than self-destructive. The action tapers into cringe comedy (drunken embarrassment) and farce (an errant cow), but it’s steered by carefully modulated character revelation, particularly on the part of Elsa, who is played by an indominatable Marthe Keller.

My Wonderful Wanda keeps surprising you to the very end; it trains us not to take everything for granted. There’s even a classic theatrical denouement, itself twisty, which is undercut by a final shot of GOFAC (Good Old-Fashioned Art Cinema) uncertainty. Yet after each reversal, you think it had to be that way. What happens later is consistent with the exposition we’ve built up.

Surprise, postponed

Concentrated exposition, gathered in an opening or elsewhere, sets our expectations, so new story information can modify or revise them. For instance, when Wanda is summoned late at night to Gunther’s bedside, I assumed he needed meds or some help going to the toilet. The expository scenes had set her up as a traditional caregiver. So I was surprised when she mechanically slipped into what became clear was a sexual routine. That prompted me to recalibrate my sense of their relationship, and it made me aware of the limits of what I’d assumed.

Which is to say that exposition as a process is usually partial. We don’t get everything in the backstory at once, and sometimes what’s suppressed is central (as in My Wonderful Wanda). A more extreme example is François Ozon’s Summer 85 (Été 85). Here the expository information is distributed much more widely across the film. We get the backstory only gradually and piecemeal. Because some important information is withheld, the film nudges us toward certain expectations that need to be adjusted.

Again, I have to be careful about spoilers, so let me talk generally. In the book that I mentioned and for many years since, I’ve written a lot about flashbacks. One common schema for flashbacks is the crisis structure. The plot starts near a story’s climax and then suspends the outcome in order to shift back into the past and show how the crisis came about. The crisis structure can provide a film’s overall intrinsic norm of narration, so we expect that this pattern will carry through from scene to scene.

Ozon, another elegant storyteller, knows we have learned the crisis structure. When the opening of Summer 85 shows the teenager Alex dragged into a corridor and then interviewed by police authorities, we’re encouraged to summon up our experience of other movies. A crime has been committed, and he’s either a witness or a suspect. Ozon sets up a familiar to-and-fro pattern between past and present, an investigation and the mysterious crime leading up to it.

The distributed exposition provides flashbacks that take us chronologically through the events leading up to the night of the arrest. Alex is drawn into a love affair with David, a charismatic older boy. With his mother David runs a shop on the beach. She is slightly scatterbrained and seems unaware of their passions, while Alex’s parents are likewise in the dark (and surely disapproving). When the English au pair Kate shows up on the beach, Alex fears David will abandon him, and we expect that a classic romantic triangle will drive the film forward.

Except that’s not quite what happens. As Alex’s jealousy deepens, we might expect a sort of Patricia Highsmith crime to ensue. Instead, Ozon dares to go with a less brutal but more plausible turn of events–one that makes us reevaluate why Alex is being investigated, and what his actual crime is. By distributing exposition slowly across the whole film, Ozon not only creates a lot of curiosity about what has actually happened, he’s able to arouse expectations that will get challenged by new revelations. He exploits the how of narration to modify our understanding of what has occurred–and, it turns out, why.

I’m sorry to be so cryptic, but I face the reviewer’s dilemma of not giving away plot twists that should take you by surprise. Here, though, the surprises aren’t short and sharp, as in My Wonderful Wanda. They unfold more gradually and allow you time to think–about the characters and their motivations, and about what you took for granted might have happened. You might even feel a bit ashamed for misjudging Alex, who turns out to be loyal and forgiving in ways we might call unexpected. Yes, dancing is involved.

Surprise?

My Wonderful Wanda has a straightforward arc of conflict and resolution. Summer 85 is more nonlinear, skipping to and fro through time, but it too can be plotted as a drama of tension and release. What then to say about Kala Azar? It’s another film that teaches us how to watch it, and how to think through it. But it seems to lack those traditional patterns of coherence.

Or rather, it has other patterns. Instead of a drama of conflict and change, it explores a situation built out of routines, gradually revealed and eventually varied. This is another plot strategy, one familiar from “art cinema.” It builds a mystery into not only the story action but into the way the story is told. What is going on? And why am I told about it in this way?

Start with the title. It refers to a severe infectious disease spread to animals and humans by sandflies. It’s currently raging as a pandemic in over seventy countries. But the film Kala Azar is less about the disease (although we spot some lesions on characters who might be infected) than about the relations of humans and animals–specifically, some marginal Greeks scrounging a living on the outskirts of a city, along with the dogs, cats, and other creatures that wander into their lives.

There are three strands of action, each with its own routines. Most prominent are the couple, a young man and woman working for a service that cremates household pets. The couple live mostly on the road in their van, gathering pet remains from households and bringing them back to a central facility. They then return the ashes (not always scrupulously preserved, it seems) to the waiting owners. Another couple, the woman’s father and mother, keep stray dogs in their house. A third line of action involves Orguz, a migrant worker glimpsed from time to time at a chicken farm nearby.

The central couple have started adding roadkill to their cargo, as if believing that these creatures too deserve a serious farewell to life. And at certain points the story strands meet, although glancingly. In something close to a traditional climax, the young man, provoked by seeing a shooting party, takes a decisive action.

All of what I’ve told you is built up through dozens of short scenes, usually without dialogue. There’s probably more going on here than I’ve been able to grasp on one viewing. But the sparse, widely distributed exposition, and the apparent looseness of the plot challenge us to fill in things as best we can. Just as important, by not providing a traditional dramatic arc, director Janis Rafa encourages us to shift our attention to other aspects of her film.

We’re invited, for instance, to examine shot composition, to explore the landscapes on which the camera dwells, to scrutinize textures and gestures. These items are sometimes seen at one remove, through dirty panes of glass or layers of focus or in slim apertures.

Entire scenes often chop off faces in order to emphasize the contact that the bodies make with their surroundings, or to turn bodies into pure pattern, as when two grieving pet lovers are shown dressed identically.

These visual strategies may seem a bit arty, but I think they build up a tactile sense of the environment of these routines. Rafa has said that she wanted to evoke the “animalistic” quality of the imagery, which isn’t only a matter of a low camera position. The sensuous quality of the vegetation, streams, and roaming dogs comes across strongly. Kala Azar earns its severe gravity through its patient attention to details of a world in which humans and animals interact in very tangible ways. Stray animals meet stray humans, and the visual style registers the encounter with quiet nuance.

From concentrated preliminary exposition, to distributed and elliptical exposition, to what we might call minimal exposition: This continuum shows some creative options available to filmmakers in telling their stories. Each one invites us to build up expectations, to reconsider new information in the light of what we knew (or thought we knew), and to assemble a coherent line of action. In other words, we think. That’s not all we do, but it’s a big part of how we watch movies.

As usual, special thanks to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Jane Harrison, Curtis Woloschuk, and their colleagues for their help during this reliably exciting festival. This is usually the time of the year when Kristin and I wish we lived in Vancouver, and that feeling is sharpened by the health crisis now engulfing so many countries. Cinema helps keep us civilized.

These and other films we’ve reviewed should be making their way to other festivals, so we hope you have a chance to catch up with them.

For more on the narrative strategies I’ve discussed here, see Meir Sternberg’s magisterial Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction (1978). This is in my view one of the great books in narrative theory.

For more on narratives built on threads of routines, see this earlier entry on Chop Shop and other films at Ebertfest. An entry on editing pursues the between-your-ears theme.

Kala Azar (2020).

TRAPPED: Low-budget flash is good for you

Trapped (1949).

DB here:

Films of the 1940s sported many vivid titles, from Double Indemnity to The Best Years of Our Lives. But a lot of them really didn’t try too hard. We have Dangerous Lady, Shock!, Men on Her Mind, Bad Sister, Lust for Gold, and Criminal Lawyer. Even worse are Crack-Up, Manhandled, Temptation, Nightmare, Impact, Homicide, and even, the purest of all, Conflict.

Fortunately the lack of imagination didn’t always extend to story and style. In the Forties, even minor genre films could get flashy, displaying weird plot turns and wild visuals. Nowhere was this truer than in films centered on crime and mystery.

Granted, this material always encouraged some unorthodox techniques. (We can find examples going back to the 1910s.) Still, whatever you think “noir” was, it encouraged filmmakers to push even further. A 1930s B would have been unlikely to be as bodacious as a moment in Detour (1945), when a single forward tracking shot lets the lights lower and makes a coffee mug as big as a bucket.

For such reasons we should be grateful to the Film Noir Foundation, to the UCLA Film and Television Archive, and to Flicker Alley for bringing us Trapped (1949). The generic title had been used by four earlier films, and it could refer to several of the characters, but the results onscreen are far less banal. I hadn’t known the film, but if I had I might have wormed it into Reinventing Hollywood for the wrinkles it adds to the government-agent semidocumentary.

Crime high and low

Product placement for studio Hollywood’s favorite brand.

Trapped was produced by Brian Foy and distributed by Eagle-Lion, the same company that gave us the bizarre Repeat Performance (1947) and some of Anthony Mann’s best Forties items. According to the disc’s informative, pleasantly sensationalistic booklet, the project was hitching a ride on the success of Mann’s T-Men (1947). The Treasury Department approved of the project, and the film includes lots of fascinating shot-on-the-street scenes of LA. Although director Richard Fleischer doesn’t mention the film in his autobiography Just Tell Me When to Cry, he should have been proud of it. (He does mention Clay Pigeon, though, a film I talk about in another entry.)

A stern voice-over launches a quasi-documentary montage of the rise of counterfeiting after the war. Tris Stewart is serving time, but bills with his signature have resurfaced. Agreeing to act as a mole, he’s allowed to bust out of prison, but soon he eludes his federal handlers. He hooks up with his old girlfriend Meg and discovers that his precious plates are in the hands of an old adversary, Jack Sylvester. The bulk of the plot follows Tris’s effort to fund a last big job before fleeing to Mexico with Meg. In the course of it, he joins up with John Downey, a down-at-heel gambler.

The viewpoint shifts freely among the characters, so we always know more than any one of them. We know that the Feds have wired Meg’s apartment for sound. We learn that Downey is actually a government agent working to trap both Tris and Sylvester. And we see Tris eventually learn Downey’s identity decide to double-cross him.

Meg has a pivotal role in precipitating the climax. She’s naturally punished for hanging out with the wrong guy. I could apply my quatrain on Hollywood Stories:

The plot only works

If the men are all jerks;

But at the end of the game,

It’s the woman to blame.

Lloyd Bridges plays the sort of natty, grinning sociopath whom he would make memorable in The Sound of Fury (1951, aka Come and Get Me!). The dry John Hoyt is needed to carry the last stretch of the film, which he does with sangfroid, but Tris exits the plot a little sooner than we’d probably like. Eddie Muller suggests that Tris was intended to be in the climax but production contingencies put Sylvester into it.

To compensate, the wrapup becomes one of those dazzling Forties climaxes played out on an overwhelming location. Like the gasworks in This Gun for Hire (1942), the field of storage tanks in White Heat (1948), and the Fort Point Compound of The Man Who Cheated Himself (1950), here a vast trolley-car barn provides spectacular compositions and lighting effects.

Noir really did bring out the best in creative personnel. Guy Roe, a camera operator and assistant since the 1930s, had moved up to Director of Photography for Sirk (A Scandal in Paris, 1946), Mann (Railroaded!, 1947), another punchy Eagle-Lion effort, and Boetticher (Behind Locked Doors, 1948), so he was ready to give this effort flamboyant touches, some overt and some more subtle.

We tend to think of crane shots as aiming for surveying vistas outdoors. By the 1940s, many interiors were shot with smaller cranes or vertically mobile dollies that permitted alternation between tight high- and low-angle setups.

Roe would go on to shoot more films now considered strong noir entries: Armored Car Robbery (1950, another flat title) and The Sound of Fury. This last, as I suggest here, promotes the same tight high angles we find in Trapped, with perhaps more fine-grained results.

Fleischer didn’t have the blasting visual force of Mann, and Roe didn’t have the baroque imagination of Mann’s DP John Alton. Still, Trapped does deliver a handsome array of long-take deep-focus shots. These attest to the influence of Citizen Kane (1941) as a prototype for dynamic compositions, often exploiting ceilings on sets.

Such angles led directors to think more about using the vertical stretch of the screen, again aided by a camera pitched slightly high or low.

One turning point, Tris’s discovery of the Feds’ bug in Meg’s lamp, is designed to exploit a slightly tipped-down framing, with the splash of light accentuating the moment of revelation.

American crime films weren’t unique in their pictorial bravado. Watching Trapped drove me back to Noose, a 1948 British film by Edmund T. Gréville. A semi-comic tale of London gangsters, it abounds in florid depth compositions. (See below.) Just more proof that the 1940s saw a new exploration of bold narrative and stylistic initiatives in sound cinema around the world. And those weren’t confined to the big productions. Once new image schemas were available, artisans at all levels could make piquant uses of them.

The Flicker Alley release is nicely filled out with informative supplements contributed by Alan K. Rode, Eddie Muller, Donna Lethal, and Julie Kirgo. Mark Fleischer offers some touching reminiscences of his father’s life and creative ambitions. Thanks as well to Jeffrey Masino and Josh Fu of Flicker Alley. And we owe a debt to the collector who deposited a 35mm acetate print at Harvard, whence it comes to us.

For more on 1940s cinematography, see our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 and entries in the 1940s Hollywood categories here. Patrick Keating’s central chapters in The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood supply a lot of information about the growing use of cranes and maneuverable dollies for intimate dramatic scenes.

Noose (1948). A Brit noir ripe for Blu-ray release.

Not just a Christmas movie: DIE HARD on the big screen

Die Hard (1988).

DB here:

It’s been quite a fall season for UW–Madison film culture. There were visits from avant-garde legend Larry Gottheim, New York Times co-chief film critic Manohla Dargis, Schawn Belston (Senior VP of Mastering at Disney), and Julia Reichert, whose American Factory is now routinely turning up on ten-best lists. The semester’s first screening at our Cinematheque was Kiril Mkhanosvsky’s Give Me Liberty, a Milwaukee movie also gracing year-end best lists. Our programs included restored films by African pioneer Paulin Soumanou Vieyra, retrospectives of Reichert and Kiarostami, a 3D double feature of Revenge of the Creature and Parasite (no, the other one), a program of early women directors in America, a selection of films conserved by the Chicago Film Society, and a miscellany ranging from Olivia and Near Dark to Tropical Malady and Red Rock West.

Travels to festivals, partly covered in our blog entries, forced us to miss too many of these shows. But we couldn’t miss the final one: Die Hard (1988).

It’s a film I’ve admired since I first saw it in summer of 1988. I’ve taught it in many classes, but never written about it. Seeing it again, in a pretty 35mm print from the Chicago Film Society, has made me want to say a few things as my final blog entry for this busy year.

The man between

Think-piece pundits like to say that Hollywood movies are about good guys versus bad guys. But usually things are more complicated. Very often the good guy is an outsider caught between two large-scale forces, good or bad or both–the cattle ranchers versus the townspeople, or the mob versus the cops. Often the protagonist is an outlier, forced to solve the problem using means that respectable social forces can’t.

Call it the problem of the House Democrats. When the lawbreaker can’t be brought to justice, how do you make him pay? The answer is one that William S. Hart movies provided in the 1910s. We need a “good bad man,” a rogue agent who knows the scheme from the inside but is willing to do the right thing. Which means that he has to be flawed too, a little or a lot, and that he can eventually reform.

In Die Hard, the forces of law and order line up as the Los Angeles police and the FBI. The threat is Hans Gruber’s gang, posing as terrorists but actually planning to rob the Nakatomi Corporation of $640 million in bearer bonds and kill lots of hostages in the process. The naive TV broadcasters support both, recycling official scenarios of how hostage-taking works and reinforcing the gang’s masquerade as a terrorist group.

The contrasts are marked. The forces of order are American, in alliance with a Japanese company, while the attackers are Europeans. At the start, we hear American music (the rap played by the limo driver Argyle), but Hans hums Beethoven. The cops’ technology notably fails, as when the assault vehicle and a helicopter are consumed by firepower. But the gang’s hi-tech expert Theo can crack the vault, assisted by Hans’ plan to push the Feds to cut the building power.

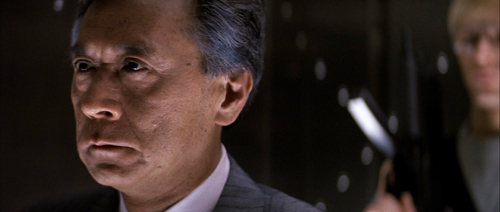

Above all, the forces of social order are strikingly inept, while the gang is ruthlessly efficient. Unlike the police, who “run the terrorist playbook,” Hans boasts that he has left nothing to chance. The cops can’t imagine an adversary that exploits the official by-the-book procedures. As for the business types, Takagi’s calm bluff and Ellis’s freewheeling jargon can’t cope with a gang leader who doesn’t get the Art of the Deal.

Clearly, America and Japan need help. That appears in the form of John McClane, the cop from the East Coast trapped in Nakatomi Plaza.

McLane is the man between, spatially and strategically. He witnesses the action from inside the skyscraper, and bit by bit he figures out the gang’s real scenario. And he’s caught between both forces. The gang tries to find and kill him, while the cops refuse to recognize him as an ally. Confronting Karl’s brother early on teaches McClane that he can’t play by procedure. (“There are rules for policemen,” says a thug who doesn’t believe in rules.) The LAPD’s ineptitude shows that McClane can’t expect help on that front. So he must become almost as reckless as his adversary, though in a virtuous cause. This principally means blowing stuff up.

McClane isn’t totally without resources. He has as helpers Al, the desk cop who comes on the scene and sustains his morale, and Argyle, who’s there to play a crucial role at the climax. But mostly he’s alone in facing problems. He needs weapons. He needs shoes. He needs to protect the hostages, most of all his wife Holly, who has climbed up the corporate ladder. (In another movie, she would be the in-between protagonist.) To keep Holly from becoming a bargaining chip, McClane needs to hide his identity. And he needs to figure out the gang’s ultimate plan, of seeding the rooftop with explosives that will destroy the building and cover their escape.

John’s solutions are notably low-tech. While the police and the gang depend on advanced firepower and computer finagling, McClane lashes an explosive to a desk chair and uses a fire hose as a rope. He has to improvise shoes by taping a maxi-pad to a bleeding foot. No holster for your automatic? How about some Christmas wrapping tape? And don’t forget to taunt your adversaries with Yankee wisecracks.

In the course of this drama, the very physical McClane becomes a model for his allies. Holly punches the reporter who revealed John’s identity, and Argyle cold-cocks Theo at the point of getaway. Most dramatically Al kills the revived Karl when he’s about to plug McClane. The people in between take up arms.

McClane and his allies solve the House Democrats’ problem. Law can’t be lawless, even in protecting itself. Business, always aiming at the bottom line, has to give up principles. (“Pearl Harbor didn’t work out, so we got you with tape decks.”) These forces of social order are inefficient, trusting, and superficial. They can’t stand up to sheer brutal onslaught. In a crisis they will fold, or simply choose the nuclear option: agents Johnson and Johnson are ready to lose a big chunk of hostages.

McClane is a mediating figure that permits the film to show you can be strategically lawless for the sake of lawfulness. The fly in the ointment, the monkey in the wrench, screws up plans on both sides, but for the benefit of everyone else.

The Big Dumb Action Picture isn’t so dumb

This thick array of thematic parallels would be interesting in itself, but it gets worked out through precise storytelling. There was a time when critics knocked action movies as simply ragbag assortments of fights, chases, and explosions. Die Hard, I think, changed ideas of just how well-wrought an action picture could be. About 53 minutes of it consist of physical action (including people sneaking around), leaving almost 70 minutes for other stuff: suspense, changing goals, surprise information, attention to parallel plotlines, and little moments like the thief pilfering candy just before an ambush.

The film typifies tidy classical Hollywood construction, beginning with an arrival (the jet) and ending with a departure (the McClanes in a limo). In between we get a big dose of the classic double plotline, romance and work. Holly’s job at Nakatomi threatens their marriage, and John takes on a temp job, that of fighting the gang, which also endangers the couple’s efforts to reconcile.

For every Superman, there’s a Kryptonite, and here the protagonist’s flaws include his fear of heights (set up in the second shot, reiterated throughout) and, more importantly, his resistance to Holly’s independence. By the end, he’s learned a lesson. The film’s streak of male sentimentality allows John to ask his wife’s forgiveness for blocking her career ambition. She’s ready to compromise too, reassuming his last name when she meets Al. The characters we care about change, at least a little. That could be the motto of most classical Hollywood plots.

As usual, we get crosscutting among several lines of action. John’s arrival is crosscut with Holly at work fending off Ellis, and in the rest of the film the gang’s stratagems are intercut with the cops’ plans and McClane’s efforts. At various points, five or six actions are alternating with one another.

All these escalating situations cluster into distinct parts, the four that Kristin has argued for as typical of Hollywood architecture.

The Setup runs about 33 minutes, culminating in the murder of Takagi and Hans’s promise that he can open the vault.

The Complicating Action, a counter-setup, coalesces around John’s goals of communicating with outsiders, avoiding capture, and attacking the thieves when he can. Through many chases and fights, the gang seeks to block all these efforts. The lines converge when John shoots Marco and tosses his body onto Al’s car. He gains the bag with the detonators, giving him the upper hand. Then the TV reporter gets involved, the cops arrive, and John is ordered to wait. Things seem to be stabilized.

After this midpoint, the Development supplies what Kristin calls “action, suspense, and delay.” Officer Dwayne Robinson arrives, pitting himself against Al and McClane. We can regard the police assault, Ellis’s clumsy attempt to broker a deal, and the arrival of the FBI men as a series of delays that endanger the stability of the standoff. At the end of this section, John meets Hans (posing as an escaped hostage): now both men know each other. And in the firefight that follows, John loses the detonators. Hans declares, “We’re back in business,” and the original plan can go forward.

The last twenty-five minutes constitute the Climax, launched by McClane’s “darkest moment.” He seems utterly beaten. Picking glass shards out of his feet, he gives Al a message for Holly over the CB radio. Al tells of his own burden, the accidental shooting of a child. The stakes are now very high.

Rapid crosscutting shows John finding the bombs on the roof and fighting with Karl, while the FBI helicopter attacks the building and Hans discovers that Holly is John’s wife. John stampedes the hostages down the stairs off the roof and escapes the strafing from the chopper before it blows. Argyle dispatches Theo, while John finds the surviving gang members in the atrium and shoots Hans, who falls to his death.

In the Epilogue, Al and John meet, Al dispatches Karl, Holly socks the newsman, and John and Holly drive off with Argyle.

These parts present a tight, logically building plot composed of swiftly changing situations. Along the way we encounter a great many motifs that create echoes or contrasts. Everyone notices the Rolex, at first a symbol of Holly’s talents but also of corporate swagger; only by unfastening it can they let Hans drop from the window. When Argyle floats the possibility that Holly will rush back into John’s arms for a movie ending, John murmurs: “I can live with that.” Agent Johnson speaks the same line, but for him it means an acceptable level of civilian casualties.

Holly’s unmarried name, Gennero, shows how a motif can develop in relation to the drama. At first it’s a sign of pride in her own identity (typical corporation, Nakatomi has misspelled it on the touch screen). Her name-change triggers the couple’s quarrel, but it has another narrative use: It conceals John’s identity from Hans. And at the end he introduces her to Al as Gennero but she reasserts her love by correcting him: “Holly McClane.”

Then there are differences of class and country. Hans reads Forbes, but McClane the US boomer references Roy Rogers and Jeopardy. (Hans is so unplugged from pop culture he thinks John Wayne was in High Noon.) Argyle the former cab driver and Al the cop know the downside of city life, but so does John the New York detective, who adapts Roy’s trademark phrase to the mean streets: “Yippee-ki-yay, motherfucker.”

Even a conventional Hollywood gesture, that of attacking a picture of a loved one, acquires a nifty plot function. Annoyed at John, Holly slaps down the family portrait on her shelf. Good thing too, because otherwise Hans would have seen it during the invasion. We’re reminded of that picture when in a moment of quiet John looks at the same snapshot in his wallet. Only after Hans has encountered John is he able to flip the portrait back up and realize that Holly is the “someone you do care about.”

There are lots more felicities like these–so many that I’d consider Die Hard a “hyperclassical film,” a movie that’s more classically constructed than it needs to be. It spills out all these links and echoes in a fever of virtuosity. Hard to believe that the makers started shooting without a finished script.

Intensified continuity, personalized

Die Hard is a good example of a stylistic approach I’ve called “intensified continuity.” It’s a modification of the classical method of staging, shooting, and cutting scenes. Here director John McTiernan and DP Jan de Bont tweak that approach in distinctive and powerful ways. You can find examples all the way through the movie, but I’ll draw most of my illustrations from the first hour, when the stylistic premises get laid out for us.

Cutting speeds accelerated sharply in Hollywood films from the 1960s onward, and for its time, Die Hard was a rapidly-cut movie. The average shot runs just under five seconds, about what you’d get in a 1920s silent film. By today’s standards, which fall more in the 3-4 second range (even for movies outside the action genre), it’s a bit sedate.

One factor that increases the cutting pace is a greater reliance on singles and close-ups. These are tighter than we’d expect in most studio films of the classic era.

Even in close-up, the shots aren’t snipped free of their surroundings, thanks to the wide frame and layers of focus–both important in the film’s overall style, as we’ll see.

Likewise, intensified continuity exploits a greater range of lens lengths than we’d find in studio films of the classic era. We get wide-angle shots like those above along with telephoto shots throughout. Here the long lens is used to pile up people around Holly, and an even longer lens shows her optical viewpoint on the bandits in the office.

And there’s a free-roaming camera, thanks chiefly to Steadicam technology. But interestingly, Die Hard avoids some of today’s most common camera movements, such as shooting a fixed conversation with a sidewise or circular tracking shot. These would become more common in the 1990s.

McTiernan thought a lot about his camera movements, as he explains in interviews and the commentary track on the DVD. He wanted to shape spectators’ attention, to use camera movement to nudge things into view. “The audience’s eye wants to go with you.” Accordingly, more than in many contemporary films, Die Hard‘s camera movements have a shape: they end on a point of information.

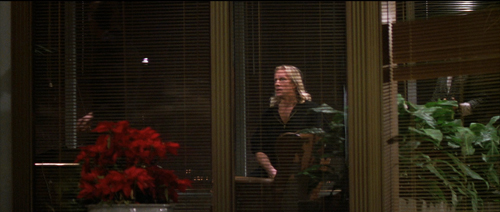

Sometimes it’s just a quick pan, doing duty for a cut. At other times, the reframing is a gentle nudge that prepares for a new scenic element, as when Holly enters her office.

In shooting Predator (1987), McTiernan wanted to cut moving shots together, but his editor resisted. For Die Hard, he refilmed his camera movements at different rates so that two would match. A good example is when Karl’s brother strides carefully into an area under construction. The camera tracks with him, but when he turns to find the source of a whining noise, the arcing movement at the end of one shot is picked up in the next as the framing circles to reveal the saw.

That reveal is given, characteristically, in rack focus. I could have added rack focus as another featured technique of intensified continuity. McTiernan and de Bont take it very far, making Die Hard one of the great rack-focus movies. The image is constantly shifting focus to guide our attention to the changing layers of the scene.

This neat, compact presentation not only preserves the commitment to long-lens close-ups we find in intensified continuity. The technique also gives each rack focus the snapping force of a cut. (And you don’t need to build big sets.) Needless to say, the rack-focusing wouldn’t work if McTiernan hadn’t committed himself to staging his action in depth. More on this below.

Staging in ‘Scope

Die Hard finds ingenious ways to “let the audience’s eye go with you” in the widescreen format. Sometimes it’s a matter of classic edge framing. Thanks to a low angle, John and Holly converse along a wide-angle diagonal.

Sometimes McTiernan reverts to a technique not enough directors use nowadays: blocking and revealing. In classic cinema that was usually a technique reserved for long shots, when actors could move aside as part of ensemble. Die Hard applies blocking and revealing to the tight framings of intensified continuity.

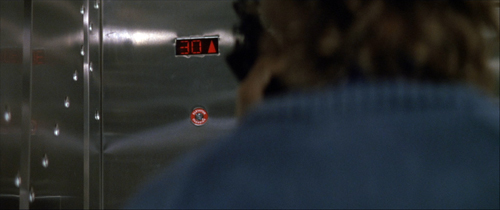

A thug in an elevator checks his weapon, pivots for an instant, and then moves aside to show the elevator arriving at the target floor.

Here again a rack focus helps. The moment reiterates the importance of the thirtieth floor in the skyscraper’s geography.

When Hans finds the body of Karl’s brother, we can study his expression. He flips the victim’s head to reveal a gunman, who looks to Hans before he says his line.

In a neat touch, the thug’s mouth isn’t shown. Today a director would probably show his whole face, but, really, who cares? The careful framing keeps him a secondary character, and a future target of McClane. And no need to rack focus on him, which would give him unwonted importance. All we need to remember him is that he’s the thug with long hair.

I can’t refrain from using one audacious example from late in the film. John and Hans have met, and Hans has revealed himself by targeting John with the pistol McClane has given him. In reverse shot, John reveals that it has no bullets and grabs it away from Hans.

But the pistol, and that gesture, have concealed the elevator behind them. When the pistol is knocked down, the elevator light pops on in the background. Our attention snaps to it, aided by that characteristic ping we hear throughout the movie (another motif).

The crisp turn of events, given visually and sonically, gets ampified by the acting. McClane’s cockiness turns to panic and Hans gets the upper hand. (“Think I’m fucking stupid, Hans?” Ping. “You vere saying?”)

The most bravura rack-focus comes during the climax, when the firehose reel whizzes down behind McClane and he realizes that he’s being dragged through the shattered window.

The coordination of the long lens, camera movement, staging, and racking focus is especially rich when Hans drifts among the hostages searching for the man in charge. He recites Takagi’s life history as he passes from one possibility to another (including, comically, Ellis).

At the climax of the passage, McTiernan’s staging-in-layers sets up Takagi, Karl, and Holly before Takagi takes charge. Briefly blocked by Hans, he admits his identity by stepping out from behind and into focus.

McTiernan isn’t done. A reverse shot of Hans finishing his spiel (“…and father of five”) punctuates the suspense. McTiernan buttons up this passage by returning to his “moving master” shot and having Karl shove Takagi out.

That clears the way for us to see Holly’s reaction. A beat dwells on her as she shifts her eyes to Hans, foreshadowing her conflict with him at the climax.

This sort of layering of faces popping in and out of visibility has precedents in earlier cinema, chiefly of the “tableau” period of the 1910s. McTiernan has, I think, spontaneously rediscovered for modern times what William C. de Mille was up to in the party scene in The Heir to the Hoorah (1916). (For more on that, go here.)

Of course McTiernan also has to work with the 2.35:1 anamorphic format, which enables him to spread his layers out more. That format also allows some remarkable compositions, such as the one surmounting today’s entry. The cut to the shot of John in Holly’s office uses the abstract splash painting (seen here for the first time) as a visual analogy for the explosion of gunfire offscreen at the same time.

McTiernan and de Bont constantly find striking but cogent images, thanks to lighting as well as color and format. Here’s McClane on top of an elevator peering through the perforated grille; his POV is a striking but still informative composition. the cut between the two provides a little punch of contrasting light and shade.

There are felicities like these feathered all through this remarkable movie, but the momentum of storytelling never flags. This remains a masterpiece of Hollywood filmmaking.

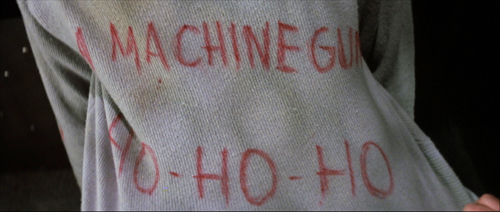

Thanks to our readers for following us this year. Kristin will be weighing in soon with her annual list of best films from ninety years ago. In the meantime, HO-HO-HO.

Madison owes an enormous debt to our Cinematheque team: programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, Ben Reiser, and Zach Zahos, as well as veteran projectionist Roch Gersbach. Santa should reward them. You can too by visiting the Cinematheque’s Podcast, Cinematalk. There you’ll find conversations with Manohla Dargis, Schawn Belston, and James Runde.

For lots of background on the making of this film and the four sequels, there’s Die Hard: The Ultimate Visual History by Ronald Mottram and David S. Cohen. At rogerebert.com, Matt Zoller Seitz has a discerning appreciation on the occasion of the film’s twenty-fifth anniversary.

Jake Tapper has provided the definitive analysis of Die Hard as a bona fide Christmas movie.

McTiernan (with whom I share an alma mater) provides very good DVD commentaries (even for Basic). Prison also seems to have given him some pronounced political views. Alas, the website he created as a platform for them is apparently no longer available. Word is that McTiernan is preparing a new film, Tau Ceti 4, with Uma Thurman. A videogame promo is purportedly signed by him.

Of other McTiernan films, I also much admire The Hunt for Red October (1990). The Thomas Crown Affair (1999) seems to me better directed than the original, and The 13th Warrior (1999), despite being taken out of his hands, remains a pretty interesting film. (Name another Hollywood movie in which a Muslim poet visiting Northern Europe is justly appalled at its barbarism.) Nomads (1986) also has its good points.

I discuss the issues of narrative and style raised here at greater length in The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies. You can also search “intensified continuity” for blog entries hereabouts. On CinemaScope aesthetics, see this entry and this video.

Die Hard (1988).

Women in charge: Highlights from Torino

Beanpole (2019).

DB here:

Every day we’ve spent at the Torino Film Festival has yielded us fine and sometimes superb film experiences. Herewith some examples, all probably coming to a screen (large, small) near you.

Extracurricular melodrama

Wet Season (2019).

From Anthony Chen (Ilo Ilo, 2013) comes a woman’s drama of professional and personal travail. Ling is a Malaysian teacher working in a Singapore boys’ school. She’s trying to get pregnant through in vitro fertilization , although her husband is reluctant. She takes care of her elderly father-in-law while pressing her mostly indifferent students to pass their Chinese examinations. Things take a drastic turn when, just as Ling’s husband drifts away from her, one boy becomes violently infatuated with her.

Poised and mild-mannered, Wet Season handles its melodramatic material with restraint. For instance, there’s the careful use of Ling’s car. She and her husband are introduced driving to work together, but the shots don’t show their faces. It’s an effective expression of their empty marriage. Similar shots recur throughout the film.

Denying us the standard view forces us to pay attention to the dialogue. Lest this be thought a simply byproduct of production constraints (it’s easier to shoot a rainy drive from the back seat), later we see Ling in a more standard angle.

The new framing allows us to see her accusing glance at Wei Lun.

Still other uses of the car enable Chen to stress Ling’s reactions to developments in the drama.

Here, as so often in film, simple but shrewd production choices can build strong emotional impact. By the end, when the typhoon has finally blown over, Ling can confront the future with some hope.

Horror diva

As indicated in our previous entry, the guest of honor for Torino’s horror retrospective was the star of 1960s Italian (and other) frightfests, Barbara Steele. She received the Gran Primio Torino during the festival. Several of her films were shown, reminding me of the delirious ways that Italian filmmakers revised the genre. Take the two features I saw.

Mario Bava’s Black Sunday (La maschera del demonio, 1960), which came out the same year as Psycho, is in some ways more shocking. The opening, in which a spike-studded iron mask is pounded bloodily into the face of a witch still makes you jump. What follows is essentially an old-dark-house plot, with one character after another prowling around a castle and getting killed off by the undead witch Asa and her brother. Asa targets her descendant, the beautiful Katia, in the belief that taking her blood will grant her immorality.

Barbara, with bat-wing eyelashes and magnificently tousled hair, plays both Asa and Katia. In a bravura image, Bava uses visual effects to give us the two women in a fine widescreen composition.

The film’s endless play of highlights and shadow is really something. Although I’ve seen it before, I never appreciated its visual splendor until I encountered this DCP restoration. Kristin pointed out that we can see how the eyelights on Asa are flicked on and off so that she seems throbbing with supernatural energy.

Two years later, Barbara made for director Riccardo Freda The Horrible Dr. Hichcock (L’Orribile Segreto del Dr. Hichcock). It’s close to 1940s Hollywood Gothics in centering on uxoricide. But in a typical giallo fantastic twist, the husband who dispatches one wife accidentally tries to kill a second to revive the first. There are 1940s motifs such as the sinister housekeeper (Rebecca), the dominating portraits of Wife #1, the efforts to gaslight Wife #2, and even a glowing glass of milk (Suspicion) with which Dr. H hopes to dispatch his new wife–played, of course, by Ms Steele.

Freda has recourse to the fog and sinister noises of Black Sunday, but Bava’s labyrinthine secret passages and torture chambers are replaced by rooms stuffed with sinister chachkies. And Hichcock is in Technicolor, so Freda gives the dank Victorian parlors a subdued color design. Barbara is right at home here too, rolling her eyes apprehensively as she’s given the poisoned milk.

In all, the Torino horror retrospective was a bracing reminder of a genre that has shaped popular cinema to this day. The presence of Ms Steele was a wonderful bonus.

Cops, moles, and femmes fatales

The Whistlers (La Gomera, 2019).

When a film is grounded in a basic genre formula, much of your enjoyment comes from seeing not only fresh twists of plot but also felicities of sound and image. That was my response to Corneliu Porumboiu’s The Whistlers (La Gomera), a quietly flashy neo-noir.

Everything is there. We have the intricate schemes of cops, crooks, and everybody in between in pursuit of mattresses stuffed with cash. There’s the tired, seen-too-much cop who works for the gang, not least because of the wiles of a stupendously gorgeous femme fatale. There are the Eurotrash thugs and heavies supervised by a calculating boss, and flashbacks that lead you to wonder who exactly is conning whom.

But Porumboiu tinkers with the familiar narrative mechanics. In an age of cellphones and video surveillance, the crooks must communicate in a frankly analog code: they whistle their messages, disguised as birdsong. The tough supervisor who suspects our protagonist is a mole isn’t the usual overbearing male, but rather a woman with her own femme fatale streak. She’s as suspicious of surveillance as the crooks, stepping outside her bugged office to negotiate extralegal stings with her staff.

Likewise, Porumboiu gives up the “free-camera” straying and fumblings that we see in so many films these days. He locks down his camera to create precise, radiant images. Here’s Gilda, yes, you heard that right, smoking and waiting for trouble.

It’s a pleasure to see crisp frame entrances and exits, along with tracking shots reserved for climactic moments, as when the gang steps into a police ambush mounted on a disused film set. A well-judged sense of framing enables an overhead shot in which the dark blood of a dead man at a work station flows into the mouse and lights it up in a discreet crimson flash.

The Whistlers isn’t as rich, I think, as the director’s earlier policier, Detective, Adjective, but it’s a satisfying genre exercise. It yields dry wit (sleek fashionista gangsters struggling to load mattresses into a small car) and surprise twists–not least the epilogue, which brings back the coded whistles in an amusing sound gag.

Women at war

Beanpole (2019).

Another way to put it: The Whistlers is that rarity today, the thoroughly “designed” film. Here all the stylistic and narrative choices stand sharply revealed as part of what we are to notice, and enjoy. (Other instances: the Coens, Almodóvar.) Another example at Torino is the already widely-praised Russian drama by Kantemir Balagov, Beanpole.

Leningrad: World War II has recently ended, and two women must face the postwar world. Iya and Masha have been gunners at the front. Iya was invalided out because of episodes of “freezing,” seizing up in a sort of paralyzed trance and making clicking sounds until the spasm eventually passes. Now she works in a hospital patching up wounded soldiers and taking care of Masha’s child, born at the front. Masha eventually returns and takes a job at the hospital as well.

But their friendship suffers through a horrific accident that plunges the towering and slender Iya, the beanpole (dilda, “tall girl”) of the title, into shame and depression. Masha, more aggressive in remaking herself as the war ends, drives the second half of the film. She begins a pragmatic relationship with the weak soldier Sasha. When he brings her home to meet his parents, proud members of the Bolshevik bourgeoisie, she supplies all her backstory about life on the front that fills in crucial gaps.

Beanpole‘s few characters–the two women, Sasha, and a weary doctor supervising the clinic–throb with a Dostoevksian intensity. With her paralysis and quiet mournfulness, Iya recalls Prince Myshkin; some shots virtually sanctify her.

As in Dostoevsky’s novels, nearly every scene is worked up to a furious emotional pitch. The nosebleed that seems to pass contagiously among characters is virtually a sign of passions under pressure.

The tension is carried through lengthy, often silent stares shared between characters thrusting themselves at one another. Balagov relies on close-ups and tight two-shots running very long; there are about 325 shots in the film’s 131 minutes. Here Iya helps a dying soldier to smoke in a perfectly composed two-shot in the wide format.

Without prettifying Leningrad during and after the siege, the film’s pictorial design is ravishing. The main sets are designed to complement one another. The hospital is bathed in a creamy light, while the night streets radiate a dark golden glow.

The apartment Iya and Masha share is ripe in dark greens and reds, the result of years of tearing away layers of wallpaper. (See our top image.) The doctor’s apartment offers a warmer, less distraught balance of reds and greens.

The palatial home of Sasha’s parents yields another register, one of tidy, frosty elegance.

And the clinic is given a dose of red and green by the painted walls and the presence of little Pashka.

The pictorial harmonies and modulations are just one part of this gripping, exhilarating film. Beanpole will be distributed by Kino Lorber in the US and Mubi in the UK.

We wish to thank Jim Healy, Emanuela Martini, Giaime Alonge, Silvia Saitta, Lucrezia Viti, Helleana Grussu, and all their colleagues for their kind help with our visit.

Thanks as well to David Vandenbossche for a correction of a movie title.

For more Torino images, visit our Instagram page.

Cynthia Hichcock (Barbara Steele), trapped in a coffin by her husband, in The Horrible Dr. Hichcock (1962).