Archive for the 'Directors: Nolan' Category

DUNKIRK Part 2: The art film as event movie

Dunkirk (2017).

DB here:

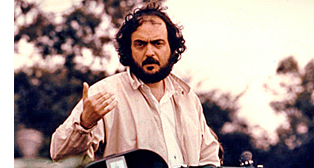

In some ways Christopher Nolan has become our Stanley Kubrick. Many directors have found ways to turn genre movies into art films; think of Wes Anderson and comedy, or Paul Thomas Anderson and melodrama. But seldom does the result become both a prestige picture and an event film.

Kubrick managed it. After showing his commercial acumen with Spartacus, Lolita, and Dr. Strangelove (costume picture, controversial adaptation, satire) he was able to make 2001, a meditation on life and the cosmos in the trappings of science fiction. From then on, he could frame any project as both working in a familiar genre and offering a challenging narrative or theme. Thanks to shrewd marketing of both each project and his image, he invested his adaptations (A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, Eyes Wide Shut) with a must-see aura. Whether or not the film was a top grosser, people said, this is a guy a studio wants to be in business with. Warners obliged.

Kubrick managed it. After showing his commercial acumen with Spartacus, Lolita, and Dr. Strangelove (costume picture, controversial adaptation, satire) he was able to make 2001, a meditation on life and the cosmos in the trappings of science fiction. From then on, he could frame any project as both working in a familiar genre and offering a challenging narrative or theme. Thanks to shrewd marketing of both each project and his image, he invested his adaptations (A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, Eyes Wide Shut) with a must-see aura. Whether or not the film was a top grosser, people said, this is a guy a studio wants to be in business with. Warners obliged.

Like Kubrick, Nolan moved from the independent realm to an assignment (Insomnia) before being entrusted with a big picture, the first of the Batman reboots. As he developed the Dark Knight trilogy, he made two films in the one-for-them, one-for-me mode (The Prestige, Inception). But Inception became his 2001, a genre hybrid (science-fiction/heist film) that proved that he could turn an eccentric “personal” project into a blockbuster. After The Dark Knight Rises, Interstellar showed that he could make an original genre film that was both prestigious (brainy, based on real science) and an event film. He became another director you want to be in business with. Warners obliged.

There are other affinities, surely. Both Kubrick and Nolan are often considered cerebral technicians, setting themselves gearhead problems with each project. They’re called cold as well. In Kubrick’s case, his detachment is best understood, as Jim Naremore has convincingly argued, as a commitment to the grotesque. Nolan, on the other hand, takes strong emotional situations as his premise but subordinates them to labyrinthine formal designs. For example, the conventional device of the dead wife justifies intricate plot structures in both Memento and Inception. Sensitive to the charge of coldness, in promoting every film Nolan emphasizes how his formal strategies aim to enhance emotion. But Kristin and I think that they’re of intrinsic interest, as she argues in relation to exposition in Inception.

There are other affinities, surely. Both Kubrick and Nolan are often considered cerebral technicians, setting themselves gearhead problems with each project. They’re called cold as well. In Kubrick’s case, his detachment is best understood, as Jim Naremore has convincingly argued, as a commitment to the grotesque. Nolan, on the other hand, takes strong emotional situations as his premise but subordinates them to labyrinthine formal designs. For example, the conventional device of the dead wife justifies intricate plot structures in both Memento and Inception. Sensitive to the charge of coldness, in promoting every film Nolan emphasizes how his formal strategies aim to enhance emotion. But Kristin and I think that they’re of intrinsic interest, as she argues in relation to exposition in Inception.

True, Kubrick the former photographer is the more fastidious stylist. You can’t imagine him accepting that his film could be shown in three aspect ratios (as Dunkirk is). The Prestige shows that Nolan can be a precise pictorialist, but as I argue in our little book on his work he’s usually looser at the level of composition and cutting. What he’s interested in above all is narrative.

It’s rare to find any mainstream director so relentlessly focused on exploring a particular batch of storytelling techniques. Like Resnais, Godard, and Hong Sangsoo (a strange crew, I admit), Nolan zeroes in, from film to film, on a few narrative devices, finding new possibilities in what most directors handle routinely. He seems to me a very thoughtful, almost theoretical director in his fascination with turning certain conventions this way and that, to reveal their unexpected possibilities.

Specifically, I think, he’s interested in subjective storytelling, and how it interacts with a very traditional film technique: crosscutting. And he manages to make both fit within a genre framework.

Take Dunkirk. Spoilers ahead.

Field-stripping the war movie

In working on Reinventing Hollywood, I came to realize that the war film bristles with a lot of narrative possibilities. You can focus on a single protagonist, as Sergeant York and Hacksaw Ridge do. Or you can spread the protagonist function to two pals, three comrades, or an entire unit. Mission-team movies like Desperate Journey or The Guns of Navarone can be tightly plotted, but films about ongoing combat can be more episodic, stressing the long slog (The Story of G.I. Joe) or the need to respond to more or less random attacks (Battleground). In most variants, battles and strategy sessions alternate with relatively dead time when the grunts ponder their fate and talk about life back home. Letters from mom or photos of wives and girlfriends are a must.

One popular subgenre is the Big Maneuver movie. In The Longest Day the Allies’ landing at Normandy is given as a panorama across nations and a trip through the military hierarchy. The viewpoint sweeps from top brass on both the Allies’ and Axis side to lower-down infantrymen, partisans, and ordinary citizens. Although A Bridge Too Far stresses the generals’ debates about what turns out to be a failed strategy, it too spends time on lower-echelon officers.

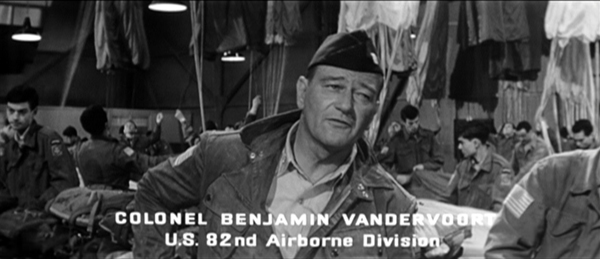

In the Big Maneuver movie, certain scenes are conventional. We see briefing rooms fitted out with maps and models of the terrain. Because the cast is vast, officers are sometimes distinguished by titles (as well as being played by instantly recognizable stars).

And when the film’s narration shifts to the grunts, we get quick characterizations that invoke their pasts. Early in The Longest Day, a rosary in an envelope reminds paratrooper Schultz of an incident at Fort Bragg.

Later in the film we’ll find out what this incident was, and what it says about his character.

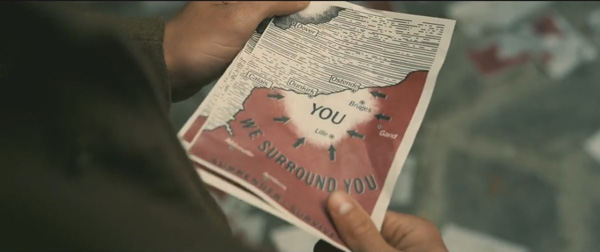

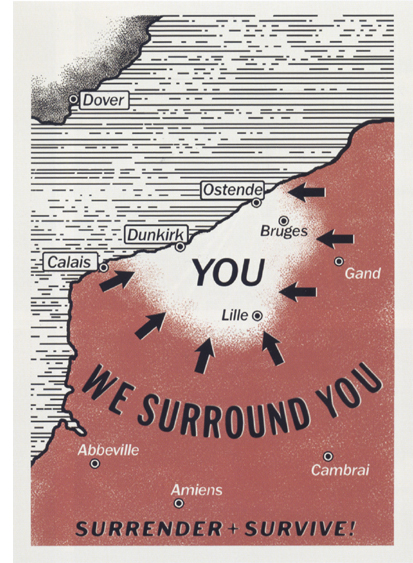

As many critics have noticed, Dunkirk adopts the framework of the Big Maneuver war movie but it strips away many of these conventions. The only map we can examine, as Kristin mentioned, is the one on the leaflets the Germans are circulating, and for our protagonist the leaflets’ biggest value is as toilet paper. Commander Bolton and Colonel Winnaut are the only brass we see, apart from a brief visit from a Rear Admiral. More important, they’re in the thick of it, not in some safe HQ reading dispatches and pushing toy ships around tabletops.

Just as important, Nolan has purged the characters of backstory. Tommy, Farrier, pilot Collins, the French boy posing as Gibson, and Alex, the angry soldier who attaches himself to Tommy, aren’t given family or memories, nor do they display tokens of home. We don’t even know how Tommy got those scars on his knuckles. Only Mr. Dawson has a bit of a past, and that’s given us late when we learn that his son, an RAF pilot, was killed–thus giving extra motivation to his patriotic urge to help in the evacuation.

While critics complained of too much exposition in Inception, now Nolan gives almost none. In one sense, this laconic presentation is characteristic of the blank spaces we find in “art films,” where character motivation and psychology are often obscure. This is, by Hollywood standards, certainly a sparse war picture. Yet Nolan has spoken of this strategy as reworking a familiar structure. His film, he says, is all climax.

For me, this film was always going to play like the third act of a bigger film. There have been films that have done this in recent years, like George Miller’s last Mad Max film, Fury Road, or Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity, where you’re dealing with things as the characters deal with them.

Kristin’s previous entry points out that in her model of classical plot structure, the film is actually both a Development and a Climax–that is, parts three and four. A Development section consists of obstacles and delays, which comprise most of the action of this film before the climactic bomber attack. Still, Nolan’s point is well-taken. In most climax sections (third acts), we know everything we need to know about the action. All the relevant motivations and backstory have been supplied in the earlier stretches, so we can concentrate solely on what happens next. In Dunkirk, we don’t see those prior sections, so we’re plunged into the prolonged suspense characteristic of climaxes.

The war movie as thriller

Granted, suspense is an ingredient of any war picture. Alongside GHQ debates about strategy, the Big Maneuver movie includes episodes aiming at momentary tension. The dive into the French village in The Longest Day offers the painful spectacle of men being shot down like a flock of geese, while A Bridge Too Far shows Urquhart (Sean Connery) trapped in a Dutch household as Nazis surround him.

Nolan’s strategy, though, is to make virtually the entire film an exercise in suspense. He understands that pure suspense doesn’t require us to like or even know a lot about the characters. We can feel tension in relation to characters we don’t like (e.g., Bruno’s reaching for the lighter in Strangers on a Train) or characters we don’t know much about at all.

Dunkirk offers a cascade of primal dangers, an anthology of narrow escapes and last-minute rescues.

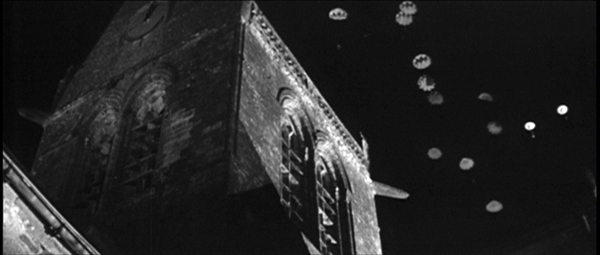

The whole film is a race against time, enclosing mini-races. Nolan plays on fears of being crushed, swallowed by darkness, blasted to bits, and shot out of the sky. How many ways can you drown–in a sinking ship, under a flaming oil slick, inside a Spitfire cockpit? The appeals are elemental and irresistible; a child of five could understand the dangers here. This catalogue of stark situations takes us straight back to silent cinema, to cliffhangers, Griffith rescues, and Lang’s dungeons filling with water. Nolan points out:

Dunkirk is all about physical process, all about tension in the moment, not backstories. It’s all about ‘Can this guy get across a plank over this hole?’

Those who want films to focus only on higher things, big ideas or subtle emotions, miss the visceral dimension of cinema. It’s led critics to avoid analyzing musicals, cop thrillers, Asian martial arts films, and Eisenstein’s action sequences. (Ritual invocations of The Body notwithstanding.) The Battleship Potemkin, Police Story, The Raid: Redemption, and much other excellent cinema happily passes The Plank Test.

Does this make the film superficial? Nolan explains that even in the absence of characterization, suspense triggers involuntary, universal responses. Consider Tommy trying to run across the plank.

We care about him. We don’t want him to fall down. We care about these people because we’re human beings and we have that basic empathy.

In creating the suspense, Nolan went, as he puts it, “in a more Hitchcock direction.” That entails, for reasons we’ve talked about here and here, playing between restricted and more unrestricted point of view. Not only do we not see the GHQ strategizing, we aren’t taken into the enemy camp. From the start, when gunfire drives Tommy down the Dunkirk streets, the attacks come from offscreen. Only at the very end will a couple of blurry Nazi-shaped figures appear behind the captured pilot Farrier.

In the end, the key for me was reading a lot of firsthand accounts of the people who were there. It became apparent to me that the subjective approach — really putting the audience on the beach with the characters, putting them in the cockpit of the plane, putting them on one of the boats coming across to help — that was going to be the way to tell the story and get across this much bigger picture.

To drive home what it feels like to just barely get by, Nolan ties us tightly to Tommy the foot soldier, Mr. Dawson and his son Peter on their boat, and Farrier the Spitfire pilot, with side visits to Commander Bolton on the Mole. Sometimes he supplies optical POV shots, but more generally he simply confines us to what happens in these men’s ken. The result is both surprise–when the bullets or bombers appear–and suspense, when we cut between Tommy and other soldiers swamped below deck while Gibson struggles to open the hatch and free them.

Even the clicking shut of a cabin latch–or not clicking it shut–generates tension, heightened by the ticking of Zimmer’s score. (At times I thought the pulse in my skull was synched up with the metronomic soundtrack.) The emblem of Nolan’s narrational strategy might be the pitiless shot surmounting today’s entry, showing Tommy flattened while bombs drop one by one behind him, coming inexorably closer to the foreground. Nolan turned superhero films, science-fiction films, and fantasy films into ticking-clock thrillers, and now he does it with a war movie.

The limiting of viewpoint links to some of Nolan’s perennial concern with subjectivity, I think, but it’s also there as a strain within the tradition of war fiction and film. Remarque’s novel All Quiet on the Western Front is like a diary, told in first-person present tense but with flashbacks in the past tense. Catch-22 is in long stretches tied to Yossarian’s jumbled memories of flight missions and hospital stays. Terrence Malick’s adaptation of The Thin Red Line, a film Nolan much admires, turns James Jones’ third-person novel into a lyrical fantasia on war as both a violation of nature and an extension of it, with flashbacks and brooding soliloquys. But in Dunkirk Nolan avoids the deeper registers of subjectivity he’s explored before–no memories, no dreams or fantasies, just brute happenings and the stubborn physical demands of earth and rock and water.

The viewpoint range isn’t as narrow as I’ve suggested, though. Nolan broadens his scope by cutting back and forth among the subjective stretches. Again, this is standard operating procedure in the Big Maneuver film. But that crosscutting was never like this.

Time out from battle

Dunkirk, sans credits, runs a little more than 99 minutes and consists of around 99 sequences. It’s very fragmentary. But then, so is a lot of war fiction. All Quiet consists of many fairly short scenes. Evelyn Scott’s vast novel The Wave (1929) surveys the US Civil War through over a hundred vignettes of the home front and the battlefront, involving characters mostly unaware of each other. William March’s Company K (1933) consists of 113 short segments, each bearing the name of one soldier and told in first-person by him (even if he dies in the course of the episode). Unlike what happens in The Wave, the men are mostly known to one another, and some actions are replayed through different viewpoints. A fancier sort of fragmentation goes on in Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead (1948), which interrupts its scenes with flashbacks (“The Time Machine”) and sections called “Chorus.”

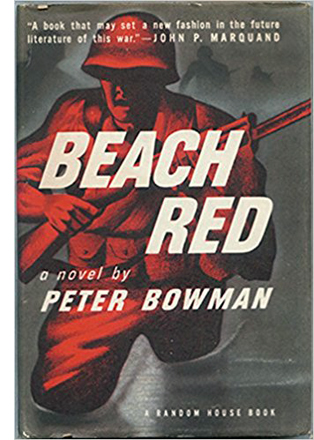

T he war novel I’ve seen that’s closest to what Nolan gives us is Peter Bowman’s Beach Red (1946). The story tells of a US effort to capture a Japanese-held island. Bowman wanted, he explained to achieve “a sincere representation of a composite American soldier living from second to second and minute to minute because that is all he can be sure of.” This heightened sensitivity to duration led Bowman to try an unusual strategy.

he war novel I’ve seen that’s closest to what Nolan gives us is Peter Bowman’s Beach Red (1946). The story tells of a US effort to capture a Japanese-held island. Bowman wanted, he explained to achieve “a sincere representation of a composite American soldier living from second to second and minute to minute because that is all he can be sure of.” This heightened sensitivity to duration led Bowman to try an unusual strategy.

His novel is in blank verse, in stanzas of varying length but all conforming to a strict pattern. Each line is equal to one second of story time. Each chapter consists of sixty lines, or one minute of story time. And the book has sixty chapters, representing the hour in which the forces take the beachhead. Like Nolan, Bowman wants a deep, visceral subjectivity, and he aims at this through a frankly mechanical layout of his text. The rigid pattern seeks to force the reader to sink into time. Bowman explains:

I have tried to create a mood of inexorable regularity that would correspond to the subtle tyranny of the military timetable. . . . I have attempted to do for the eye what the ticking of a clock accomplishes for the ear. . . the relentless inflexibility of time itself.

The aching inching forward of time is stressed thematically too, which includes reflections like “Would there be armies if clocks had never been invented?” The book ends with the second-person narration (“You”) dying. Soldier Whitney reports: “There is nothing moving but his watch.”

Like Bowman, Nolan is interested in both the psychology of time and the problem of representing it in his artistic medium. I maintained in our book on Nolan that he isn’t only interested in shuffling chronology. I think that he’s particularly keen on exploring what the technique of crosscutting does to story time.

He has explained that he got the idea from Graham Swift’s 1983 novel Waterland.

It opened my eyes to something I found absolutely shocking at the time. It’s structured with a set of parallel timelines and effortlessly tells a story using history–a contemporary story and various timelines that were close together in time (recent past and less recent past), and it actually cross cuts these timelines with such ease that, by the end, he’s literally sort of leaving sentences unfinished and you’re filling in the gaps.

Crosscutting would become a central artistic strategy for Nolan, a way of shaping his other storytelling choices.

Admittedly, what strikes you first about Memento is its flagrant exercise in reversing story order. But that 3-2-1 sequencing is accompanied by a counterpoint, that of chronologically advancing time, 1-2-3 in the present. Backwards-moving sequences are crosscut with forward-moving ones. Likewise, the structure of Following stems from treating phases of a single action as different story strands which can be crosscut. And the shuffling of order in The Prestige comes from intercutting stretches of two characters’ lives in complicated polyphony.

In his last three films, I think that Nolan, intuitively or deliberately, has hit upon an important feature of conventional crosscutting. Nearly all crosscutting in fictional cinema presumes different time spans, or rather different rates of change, in the crosscut lines of story action. We presume that overall the actions are simultaneous, but at a finer level, they proceed at different speeds. Some parts of the action in one line are skipped over, while other actions in another line are prolonged.

This disparity can be seen in some of Griffith’s classic sequences. In The Birth of a Nation, the black soldiers are inches away from breaking into the cabin’s parlor while the Ku Klux Klan is riding to the cabin, but the riders are miles away. If both strands were on the same clock, the Klan would arrive much too late.

Crosscutting allows Griffth to skip over the distance that the Klan covers, so the riders arrive at the cabin “implausibly” fast. Correspondingly, the glimpses we get of the cabin stretch out the action “unrealistically.” To put it technically, we get ellipsis in one line of action, expansion in the other.

Nolan does the same thing in his crosscut sequences. Consider the passage in The Dark Knight when the judge opens the Joker’s fake message. One or two seconds in her timeline are stretched while Gordon’s conversation with Commissioner Loeb runs on a different clock, consuming several seconds. And when Harvey Dent talks with Rachel and is grabbed by Bruce, that action takes even longer.

To speak of different clocks is a bit misleading; we can’t think that the judge turns over the envelope in super-slo-mo. But the idea of different rates of unfolding is useful because it reminds us that crosscutting aims to convey an overall impression of simultaneity. When we look closer, we realize that the action in one story line can be slowed or accelerated while another story line is onscreen.

Nolan’s interest in this quality of crosscutting is literalized in Inception, in which embedded dream actions unfold at different speeds on different levels. In Interstellar, cosmology motivates crosscutting between slow and fast rates of change. In the first planet the astronauts visit, one hour is equal to seven years on earth, so characters literally live at different rates. The pathos of the film depends upon the fact that Cooper returns, barely aged, to his daughter, to find an old woman on her deathbed. But the differential also allows Cooper to appear to her as the ghost that she saw in childhood and, in circular fashion, set him off on his mission.

The war movie as puzzle film

Nolan notes for Interstellar.

For Dunkirk, Nolan found another way to highlight the rate differences secreted within crosscutting. Like Bowman in Beach Red, he lays down crisp time markers. Farrier’s combat sortie lasts one hour; Dawson’s rescue efforts at sea last one day; and events around the breakwater (the Mole) are said to consume one week. The actual evacuation ran longer, but Tommy and his pal aren’t the last to leave.

These three stretches of action could have been presented as separate blocks. We might have been attached first, say, to Dawson and his boat to attain a pitch of excitement during the bombing of the minesweeper. Then we could flash back to Tommy at the start, in a long lead-up to being rescued by Dawson. Finally we could cover the same events yet again by starting with Farrier’s aerial combats and tracing his fate. The film could have concluded with an epilogue showing Tommy and his pal safely on the train.

Interestingly, Kubrick explored this creative option to a limited extent in The Killing, his 1955 adaptation of Lionel White’s Clean Break. As in the novel, one string of scenes sticks with one participant in a racetrack robbery. Then we jump back in time, guided by a voice-over narrator (“About an hour earlier…”) and follow another man leading up to the situation we’ve already seen. Tarantino did the same block-shifting in Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction and Jackie Brown, and he (rightly) noticed it as a standard literary technique.

Novels go back and forth all the time. You read a story about a guy who’s doing something or in some situation and, all of a sudden, chapter five comes and it takes Henry, one of the guys, and it shows you seven years ago, where he was seven years ago and how he came to be and then like, boom, the next chapter, boom, you’re back in the flow of the action. . . . Flashbacks, as far as I’m concerned, come from a personal perspective. These [in Reservoir Dogs] aren’t, they’re coming from a narrative perspective. They’re going back and forth like chapters.

But Nolan avoided block construction and went for braiding. He splintered his story lines and crosscut them. Events that are mostly taking place at different times are, as it were, laid atop one another and offset. Crosscutting en décalage, we might say.

I’m struck by how bold this is. A more conventional choice would be to confine the action to a fairly brief stretch of time, say two hours, with the rescue fleet arriving at the climax. There might even have been an effort to handle the action as occurring in “real time,” that is, with the duration of the scenes matching their duration in the story. In any event, Nolan could have crosscut his four men–Farrier in the air, Dawson and others at sea, Bolton and Tommy around the Mole–at the points when their activities are roughly simultaneous. If Nolan wanted to include earlier incidents, such as Tommy’s escape from the Germans or his efforts to board the Red Cross ship, those could have been presented as personalized flashbacks. Instead, all that material appears in chronological scenes, but on three distinct time scales.

Nolan set himself enormous problems with this choice. He chose to show the time frames without recourse to an onscreen calendar or clock; after the three initial titles indicating the places and the time spans, we get no more explicit markers. Then Nolan faced the problem of how, on a finer-grained level, to gather these fragments into a whole. He had to create parallels, and, eventually, convergences.

So early in the film, Tommy and Gibson run a stretcher to the departing Red Cross ship.

Cutting makes their urgency flow into that of Mr. Dawson hastening to cast off before the navy requisitions the Moonstone.

Forty-five seconds later Farrier’s team is sent to Dunkirk.

In story time, of course, these aren’t simultaneous at all. Tommy’s attempted escape happens days ahead of Mr. Dawson’s departure, which is hours ahead of Farrier’s mission. But Nolan, aided by Hans Zimmer’s endlessly propulsive score, has given all three primary roles in launching the film’s plot, the start of a time-gapped fugue.

That sort of primacy works at a higher pitch when two life-or-death situations are intercut. Tommy, Alex, and some other soldiers have rashly taken shelter in a fishing trawler, hoping that the tide will carry them away from the beach. But they get pinned inside by target fire. The tide has indeed pulled them out to sea, but the hold is taking on water–at the “same time” (not) that Collins, trapped in the cockpit of his ditched plane, is himself about to drown. The two scenes are intercut.

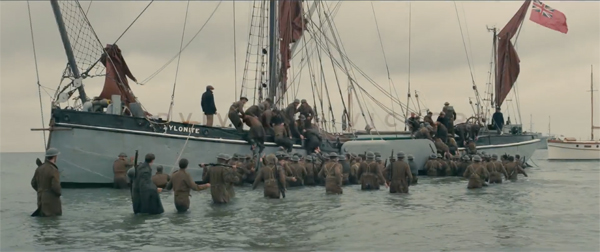

At the climax, the gestures of rescue are exuberantly crosscut: Dawson hauling on the oily survivors of the blasted minesweeper, the civilians helping the stranded soldiers clamber aboard their boats.

In this passage, Nolan daringly cuts single shots of Dawson’s Moonstone moving as if in sync with the impromptu flotilla, even though he’s some distance off; the crosscutting makes him visually one of the fleet near the Mole.

Crosscutting can also dial up the suspense by delaying the outcome of a line of action. Farrier’s dogfights are pretty much incessant, so cutting away from them to more placid action on the beach or in Dawson’s boat postpones their outcome. Nolan points to another advantage of intercutting the different periods:

You have three different intertwined storylines, and you have them peaking at different moments, so that the idea is that you always feel like you’re about to hit–when you’re hitting the climax of one episode of the story . . . then another one is halfway through and the other one is just beginning. So there’s always a payoff.

Nolan compares this to the “corkscrew” effect of the Shepard Tone in music, which David Julyan used in the drone soundtrack of The Prestige.

At other points, the crosscutting uses one line of action to explain another. While Tommy and Gibson take refuge in the second ship, the Shivering Soldier tells Dawson he refuses to return to Dunkirk because his ship was hit by a torpedo. Soon enough we see a torpedo rip open the ship and plunge Tommy, Gibson, and Alex into the night sea. And soon after that, when they try to clamber into a lifeboat, they’re told by an officer to stay in the water: it’s the Shivering Soldier, pre-PTSD. The contrast between his cool efficiency near the Mole and his spasm of cowardice on the Moonstone is another proof of war’s disastrous impact on warriors.

The lines of action, segregated by crosscutting, intersect eventually. Farrier’s teammate Collins ditches his plane and is rescued by Dawson; later Tommy will get on the Moonstone as well. These are staggered a bit in the film’s unfolding, having the effect of replays. At at least one point, though, I think that all three lines converge. One moment unites Farrier shooting down the German bomber, Dawson steering his ship away from the falling plane, and Tommy, dragged along underwater and hauled to the deck. Shortly the realms of Air and Mole converge when Bolton sees the German plane go down and his men cheer Farrier’s plane as it glides past.

After these moments are briefly pinned together (the script calls it the “confluence”), the time scales diverge again. The epilogue phase of the film resets each strand’s clock. The rescued men arrive at Dorset, and Tommy and Alex board a train at night. Back at the Mole, it’s still daylight and we can see Farrier’s plane burning in the distance. A day or so later in Dorset, the newspaper has published a tribute to George. Now we see Farrier days before, still within his allotted hour of story time, guide the plane down, step out, and set fire to it, as Tommy reads from Churchill’s speech.

Three viewings of the film weren’t enough for me to catch all the alignments, shifts, and echoes, the glimpses of things that take on importance only retrospectively. Early on, a distant shot of Collins’ downed plane briefly shows what turns out to be the Moonstone chugging towards it. On first viewing I was puzzled by Farrier’s view of a sinking private ship; only on the second pass did I realize that it’s the blue trawler that we’ll later see the young soldiers hiding in and fleeing from. And it’s likely, even with many pages of notes, that I’ve mistaken some of the juxtapositions that fly by. (The film averages about 3.3 seconds per shot, and sometimes we jump across story lines in a fusillade of alternations.) Like other puzzle films, the film demands rewatching and scrutiny, and it merits it.

In all, Nolan has taken the conventions of the war picture, its reliance on multiple protagonists, grand maneuvers, and parallel and converging lines of action, and subjected it to the sort of experimentation characteristic of art cinema. (As, in a way, Bowman’s time-grid in Beach Red anticipates the rigor of the Nouveau Roman.) Nolan exploits one feature of crosscutting: that it often runs its strands of action at different rates. He then lets us see how events on different time scales can mirror one another, or harmonize, or split off, or momentarily fuse. As a sort of cinematic tesseract, Dunkirk is an imaginative, engrossing effort to innovate within the bounds of Hollywood’s storytelling tradition.

The juxtapositions aren’t just fancy footwork, I think. In this film, because of the imminence of danger, heroism gets redefined as luck and endurance.

A cynic could call the movie Profiles in Cowardice. Tommy flees German bullets and instead of helping the French hold the barricades, he keeps running. The French boy steals boots and an identity in order to get off the beach sooner. He and Tommy try to slip on board a departing Red Cross ship as stretcher bearers. When that fails, they hide among the pilings. When the ship is hit, they leap into the water, the better to pretend to have been among the survivors and get a new ride. The Shivering Soldier wants to cut and run, and the soldiers who drift beyond the perimeter plan to use the blue trawler to carry them to safety, jumping the evacuation queue. All too often, despite acts of aid and comfort, it’s every man for himself.

At one point Alex claims “Survival’s not fair.” Too right. Mr. Dawson risks his and his son’s life to save a few men, while the lad George, who joined them on impulse and promised to be useful, dies before he can do much, accidentally killed by the Shivering Soldier. The closest the film comes to standard war-movie heroics is Farrier’s cutting down Stukkas. And he doesn’t make it back.

By plunging Tommy and his counterparts into almost unremitting peril, Nolan’s suspense tactics lower the bar for heroism, making us hope that they simply get away, somehow. Trapped on land and sea, you can’t fight dive bombers, U-boats, and marksmen squeezing in from the perimeter. At the end, the boys disembarking at Dorset are reassured that survival was enough. And thanks to Nolan’s crosscutting, individuals at different points in time are shown pulling together to make retreat its own victory.

I wrote nearly all this entry before I got a copy of the published screenplay. Reading Nolan’s conversation with his brother there enabled me to add the quotation about catching lines of action at different points (p. xxii). This conversation also considers the reasons Nolan omitted GHQ scenes (mentioning A Bridge Too Far) and adds comments about Hitchcock, early sound filming (some mistakes here), and The Thin Red Line (“maybe the best film ever made,” xiii). As far as I can tell, the screenplay is fairly close to the finished film until the climactic bombing of the minesweeper; at that point, the onscreen editing doesn’t completely match what’s on the page.

Speaking of climaxes, I should add that even though the film is in Nolan’s sense “all climax,” it also falls quite nicely into Kristin’s four-part structure. I think the midpoint comes when Tommy and his mates head to the blue trawler, starting a typical Development section.

My quotation from Tarantino comes from Jeff Dawson, Quentin Tarantino: The Cinema of Cool (New York: Applause, 1995), 69-70. The Nolan quotation about Waterland comes from Jeff Goldsmith, “The Architect of Dreams,” Creative Screenwriting (July/ August 2010), 18-26 (available, sort of, here).

On the tendency of war novels to play with time, it’s worth mentioning that Catch-22 may exemplify one weird possibility. The Yossarian plotline slips between past and present very fluidly, with some sentences containing several jumps to and fro. The Milo Minderbinder plot is linear, tracing Milo’s building of his empire in 1-2-3 order. But Milo’s progress appears at different moments in past and present in the Yossarian strand, so some critics have argued that the novel has a deliberately impossible time scheme. See Jan Solomon, “The Structure of Joseph Heller’s Catch-22” (1967) and, for rebuttal, Doug Gaukroger, “Time Structure in Catch-22“ (1970). Even if Catch-22 doesn’t actually do this, it remains a creative option that someone should try. Mr. Nolan?

Is the name of Dawson’s boat, the Moonstone, an homage to Wilkie Collins’ 1868 mystery novel? Collins tells the story through different character viewpoints and skips back and forth in time, using replays that gradually explain what’s going on. Mr. Nolan?

For more on block construction, especially in the work of Tarantino, see this entry. You can find more of our thoughts on Nolan’s work in our book Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages (with lots more about crosscutting). See also our blog entries on Inception (here and here), “Superheroes for Sale,” and “Niceties,” and our online article (originally in Film Art) on sound in The Prestige.

Dunkirk (2017).

DUNKIRK Part 1: Straight to the good stuff

Kristin here:

All kinds of spoilers ahead.

The last time I wrote about a Christopher Nolan film on this blog, I was defending the unusual use of protracted exposition to explain Inception’s complicated plot premises. (Critics had complained about the lack of character depth, though I daresay that we knew more about those characters than we do about the ones in Dunkirk.) Concluding that discussion, I said, “I don’t see why we should get annoyed because Inception doesn’t contain rich, fully rounded characters. It’s clearly a puzzle film that takes the usual complicated premises of a heist movie and pushes them to extremes. Accepting the flow of nearly continuous exposition may remove some of the frustrations viewers face. After all, there’s no rule against it.”

Art occasionally does have rules, often imposed from without by government dictate or patronage preference. Artists can impose rules on themselves to guide their creativity, or groups of artists can agree upon rules that define specific types of artworks, like sonnets or sonata-allegro form. But mostly it has norms and conventions–rules of thumb rather than strict rules–and originality consists of playing with them in interesting ways. Now Nolan gives us a film that has even less character psychology and backstory than in Inception, but it also avoids that film’s great lashings of exposition.

Most reviewers seem to have understood that depth of character and explicit elaboration of complex premises are not what Nolan was going for:

If the result holds individual characters at a bit of a remove, then, it isn’t by accident. The enormity of the potential destruction, and the scale of the evacuation and defensive military action, would likely be hampered if the film indulged in too much narrative buildup or character backstory. (Alissa Wilkinson)

In a compact 105 minutes, he takes what was in reality a nine-day effort and brings it all into focus, even without dwelling on a lot of character exposition or development. This is not a typical war picture in which we get much backstory of the men fighting it. […] Told from different perspectives on land, sea, and air, we barely even know the names of the key characters. (Pete Hammond)

The latter point is certainly true. Most of the characters’ names are only given in the credits (and possibly in some of the notoriously inaudible passages of dialogue).

A few reviewers complained, however. Deborah Ross, a critic who in the old days might have been characterized as “dyspeptic,” shunts off her own response onto her readers.

But mostly you must understand that Nolan wants us to come at events as they happened, which means this isn’t about individual heroism, or any kind of character development. (No one carries a letter from a beloved in their inside pocket, for example.) It is brave, and even admirable, but if you are fond of an emotional core? Then you will sorely feel the lack of it. (Deborah Ross)

The readers might or might not find this a failing. Clearly Ross did, but I don’t think this reaction is typical. Surely suspense, empathy, pity, admiration, and ultimately bittersweet relief and pleasure are evoked by this film. My friends and colleagues who have seen the film describe audiences remaining dead silent, a rare thing these days, riveted to the screen throughout. That was certainly true in the two viewings I have had so far.

Let’s assume that Dunkirk does arouse emotions in most viewers, though using an approach that departs from that of conventional war films. Let’s also assume that the story being told is fairly simple, though made elaborate by the ingenious intercutting among the three time frames. David will discuss those two traits in Part 2 of our discussion.

On a need-to-know basis

How Nolan does Nolan convey what little exposition he gives us? Of course, his subject is a famous historical instance of triumph in the face of overwhelming adversity. The Dunkirk evacuation is familiar to most British citizens, and educated Americans and others will have at least a bare-bones notion of the event. Still, he obviously needs to get across points that are salient to this particular film’s treatment of this huge, relatively length operation. (The Dunkirk evacuation took place from May 26 to June 4, 1940.)

Rather than the frequent explanations Nolan used in Inception, here he drops in little pellets of premises at intervals that get broader as the film progresses.

To start with, Nolan gives us the basics of the initial situation–which remains the basic situation until very near the end–all at once with written texts. A title gives the most salient facts about the 300,000 troops trapped by the Germans, and in the first scene the information is supplied with admirable economy by the German fliers dropped on a small band of British soldiers. The one we see in close-up (above) provides the only map we’ll ever see. (At right, the flyer as designed for the film, from James’ Mottram’s The Making of Dunkirk.) Indeed, this is among the few bits of written information we ever get during the main plot; in addition there are the three early titles establishing the geographical areas and their plotlines, the names of the ships and boats, and the chalked records of fuel levels on the control board of the main pilot, Farrier (Tom Hardy). In a conventional war movie, we might expect explanatory maps pored over by officers or letters from home read out by idle soldiers. Writing returns in the epilogue, with the newspapers that report the triumphant retreat, show us George’s obituary, and provide Churchill’s speech, as read by Tommy.

the names of the ships and boats, and the chalked records of fuel levels on the control board of the main pilot, Farrier (Tom Hardy). In a conventional war movie, we might expect explanatory maps pored over by officers or letters from home read out by idle soldiers. Writing returns in the epilogue, with the newspapers that report the triumphant retreat, show us George’s obituary, and provide Churchill’s speech, as read by Tommy.

Apart from telling us that the troops are surrounded, the white area of the map on the flier explains that the trapped men are on beaches extending from Ostende in Belgium to nearly Calais in France. This lets us know that the entirety of the 300,000 trapped men are not at Dunkirk itself and that we should expect to see only a part of that group. At the bottom of the map and difficult to read (this is why we see it in IMAX) is another message, “Surrender + Survive.” This will be a tale of survival without surrender–apart from Farrier’s heroic self-sacrifice at the end. He surrenders and presumably is killed, while most of the others do survive.

After this we get mere scraps for a significant stretch of time. The notion of an organized, prioritized evacuation is demonstrated rather than explained. There is the soldier at the end of a queue who snarls to Tommy that it’s only for Grenadiers. We see desperate French soldiers turned away from the Mole, where a hospital ship waits to take away the British wounded and those assisting them. We learn all this quickly, barely noticing that we’re receiving exposition, and this plotline can go on for a while with little further information.

The setup of Mr Dawson (Mark Rylance), Peter (Tom Glynn-Carney), and George (Barry Keoghan) is sketchy indeed. We learn that the small private boats are being requisitioned for the rescue effort. Dawson is characterized by his neat three-piece wool suit (he discards the jacket for a sweater) and not much else. The brief scene ends with a shot of stacks of life-preservers waiting to be loaded aboard the Moonstone, perhaps hinting at Dawson’s ambition to rescue a considerable number of men despite the apparent small size of his boat. We do not learn where the Moonstone takes off from, though near the end it’s revealed to be Weymouth, a town quite far west from Dunkirk along the southern coast of England.

A cut to the Spitfires in the sky establishes the third timeline of one hour, and the brief scene mainly serves to allow a voice on the radio to set up the idea of limited fuel, with only 45 minutes at Dunkirk possible: “Save enough to get back!” Another brief scene returns to the beach and we see Tommy (Fionn Whitehead) and his friend Gibson (Aneurin Barnard; the name is given only in the credits, and, not being French, is probably the name on the dog-tags he has stolen) trying to pass themselves off as stretcher-bearers in order to get onto the hospital ship, thus trying to evade the prioritized evacuation system set up earlier.

We return to Dawson loading his boat. He looks anxiously at a group of Royal Navy officers and sailors further along the pier. The officers are assigning small groups of sailors to each of the rescue boats, and Dawson obviously is hurrying to cast off before they can reach his boat. (The three Spitfires pass over the Moonstone at this point, providing the first, tangential link between two of the stories.) Dawson says, “I’m the captain!” further implying that he doesn’t want the sailors aboard his boat. He departs, leaving the puzzled-looking officers and sailors looking after him. We never find out why Dawson is so averse to having a few official crew members abroad, and it isn’t necessary to the plot.

After more crosscutting among the plotlines, a Rear Admiral (Matthew Marsh) shows up to talk with Commander Bolton (Kenneth Branagh) and Colonel Winnant (James D’Arcy). They deliver as big a dose of exposition as we get in the course of the film: the German tanks have stopped, Britain needs to get its army back for future battles, the English coast is a remarkably short distance away, Churchill wants to have at least 30-45,000 men out of the roughly 300,000 trapped on the beach rescued, and the sea at Dunkirk is too shallow for any but small boats.

There is no point in picking out all the moments that provide us with information in the course of the film, especially give that the crosscutting is so insistent that most scenes are split up. Nolan takes advantage, however, of having three threads of action running simultaneously. This allows him to explain something through the action of one thread and have that knowledge carry over into one or both of the others. Most notably, there is the scene where Dawson and Peter rescue the Shivering Sailor (Cillian Murphy) from a nearly sunken ship (top). George asks him, “You want to come below? Much warmer.” the Sailor refuses, terrified, and Dawson tells George, “Leave him be, George. He feels safer on deck. You’d be, too, if you had been bombed.”

Immediately before this scene we had witnessed the hospital ship hit, with men jumping from the deck into the sea. There had been no attention paid to those, if any, below deck. Immediately after the scene of Dawson mentioning feeling safe on deck, however, there begins the extended action of Tommy and his French friend being ferried to another large ship where a nurse sends the men below to get tea and jam sandwiches. The door is locked behind them, and Alex (Harry Styles) asks Tommy where his friend went. Tommy replies, “Looking for a quick way out. In case we go down.”

That ship does go down, with the men and nurses trapped underwater in the locked room until Gibson opens the door and lets at least some, including Tommy, escape. The notion of being trapped below deck becomes a major part of subsequent scenes, as Gibson finally drowns when he cannot make it out of the swamped derelict ship in which a group of the men try to put to sea. At one point the attacks cause such chaos that men in the sea are climbing onto a sinking ship’s top deck while at the same time men on lower decks are jumping into the water.

Partly because of the scrambled time-scheme, some exposition ends up being given remarkably late in the action. Well into the film the second Spitfire pilot, Collins (Jack Lowden), is hit and decides not to bail out but to stay with his plane and ditch it in the water. Shortly after this we return to the point where the three Spitfires had originally flown over Dawson’s boat, witnessed by Dawson, Peter, and George. Dawson identifies them as Spitfires and enthuses over them, saying they have Rolls Royce engines. We have seen several scenes with the Spitfires by the point at which they are identified for us. Not that we absolutely need this information, but it invokes the great affection and admiration felt for the Spitfire in Britain and in general helps motivate Farrier’s feats later in the film. The identification also adds a poignancy to Farrier’s defiant immolation of his plane at the end.

More significantly, near the end of the evacuation portion of the film, Collins asks Peter how his father knew how to sail a boat to evade fire from an airplane. Peter replies, “My brother. He flew Hurricanes. Died third week into the war.” (Hurricanes were the other main type of British fighter plane used during World War II.) Almost any other film would reveal Dawson’s loss of his pilot son soon after he is introduced, to motivate his decision to risk going to save other young man and his zealousness in saving as many as he can. Nolan withholds this until nearly the last time we see Dawson. Even if we didn’t learn this scrap of backstory, we would admire Dawson’s willingness to undertake the rescue mission, and we would accept it as due to the legendary British pluck that underlies the whole story.

If we did learn of the death of Dawson’s son early on, we would be likely to view his actions and statements quite differently through the rest of the film and to focus more sympathy on him. This is not, however, a psychological study in heroism. We do not need to know much about these characters. We are inclined to sympathize with people in trouble, especially ones we know are on the right side in a conflict. The crosscutting, the music, the choice of a small number of point-of-view figures to personalize the actions of a much larger group–all these techniques suffice to keep us absorbed.

Often while helping publicize their films, actors describe elaborate backstories they devised as aids for portraying characters, even though none of the information in those backstories would ever be used in the film. Not so with Dunkirk, at least according to Rylance, who describes the simple assumptions he had about Dawson:

Chris is very particular and very much in control of everything as a director, but he didn’t micromanage any of the scenes. He really much responded to how we played the dialogue he had written. The interesting thing about this film is that it doesn’t have 20 minutes of exposition and back story.

What we do know about Mr. Dawson is that he has a wooden motor boat, which I assume had never been across the Channel before. It was for going out with his family in the Bay of Weymouth, which is a town in southwest coast of England, and maybe going along the beautiful coast. It is a pleasure boat that was built in the 1930s and was therefore relatively new at the time. He has a son, who has a friend who hops on the boat.

There is almost nothing here that we can’t learn from what we see on the screen, and even if one is not familiar with Weymouth, the scenes set there were actually filmed on location to give us a quick impression of the place.

In effect, what Nolan has done is to start his film roughly in the middle of a conventional film story, skipping the Setup (exposition) and Complicating Action portions and starting with what would ordinarily be the Development (obstacles) part of the film and its Climax. Then he provides us with snippets of information to get us up to speed without interfering too much with the suspense.

Finally, we don’t need much information to know why and how such people did what they did, because we know it happened.

The color of suspense

The first short trailer for Dunkirk, called an “Announcement” rather than a “teaser” on Youtube, was posted there nearly a year ago, on August 4, 2016. There were a lot of titles naming Nolan’s previous films, with only six shots, some of which didn’t make it into the final film. The one above, for example, though I’m not sure about some of the others. It’s a pity that one didn’t make the final cut, but my point is that immediately upon seeing that tiny trailer 1) I really wanted to see Dunkirk and 2) I was immediately reminded of James McNeill Whistler’s series of paintings collectively called Nocturnes.

This is rather odd, since the Nocturnes obviously depict night scenes, and relatively little of Dunkirk takes place at night. Whistler’s paintings, however, depict a sort of dusk or night lit up by the glow of London. (They mostly show the Chelsea-Battersea region of the Thames.) They are striking for the wash of nearly monochromatic color with shadowy shapes of buildings or ships or distant shorelines, with a barely distinguishable horizon line, as in “Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Cremone Lights” (1872)

and “Nocturne: The Solent” (1866).

I’m not implying that Nolan or cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema was influenced by Whistler. I have no idea whether they’re familiar with the artist’s work. I’m just suggesting that they are using a similar technique. Nolan never tries for the level of abstraction present in Whistler’s Nocturnes, since he has a story to tell, and an epic one, crowded with people and vehicles and incidents. Still, through much of the film he uses an unusually restricted range of colors, mostly shades of brown and tan, gray, blue-gray, and black. There is usually something in the foreground, but the action is placed against backdrops that emphasize this same sort of hazy composition where sea, sky, and land come close to blending. Although the land is termed “The Mole” in the first expository title, the first plot thread introduced is essentially the beach and its surroundings, and so earth, air, and sea are emphasized by the very fact that they are not as sharply differentiated as one might expect in a conventional film.

To be sure, the first scene is crisply focused and brightly lit, so that we can get a good sense of the geography of the beach and sea and the vulnerability of the men crowded on it.

Soon, however, the sunlight disappears, and we are left with a much hazier background of more muted colors, with a gray sky and ocean, as Tommy and Gibson begin their attempt to carry a stretcher aboard the hospital ship.

The Mole itself creates a stark shape, but the ships and smoking buildings in the distance could come straight out of a Whistler canvas.

The effect is enhanced by drifting smoke or, in a another scene, a light fog.

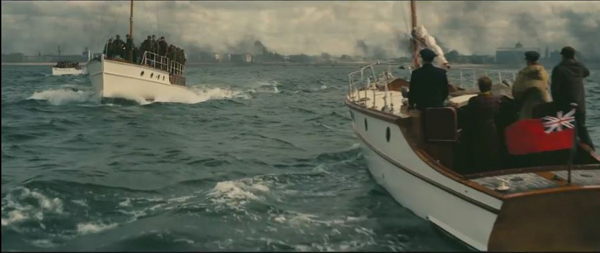

The shots of the planes occasionally show some blue sky or sea, as do a few of the shots of the Moonstone, as in this one with dark blue water forming a sharp horizon.

On the whole, however, the sea shots show a very muted palette, as in the image at the top of this entry.

In contrast, the harbor at Weymouth from which the Moonstone departs creates a much busier composition, with many crisp verticals and highlights of color which, if not bright, are at least cheerier than the hues on the Dunkirk beach.

The point of this restraint in the use of color is clearly in part to capture the realism of the weather. It also, however, enhances the oppression of the men’s situation as they wait for help in a maddening combination of tedium and terror.

The film’s few bits of bright color are mostly red, and they are mostly associated with rescue–successful or not. Early on there are the large scarlet crosses on the rescue ship that is abruptly bombed and sunk.

Later, Tommy and his comrades are served red jam sandwiches aboard another ship that is torpedoed and from which they barely escape.

The successful rescues, however, come from the fleet of small private boats, with their flags providing flashes of color, modest within the huge frame, as befits the little boats they adorn.

These flags are Red Ensigns, with a Union Jack in the upper corner of a red rectangle; they are used by civilian boats in the UK.

Dawson’s ship, oddly enough, flies a Blue Ensign (above) rather than a red one. Is this just an attempt to hold back the red motif until we see the other small boats nearer the Dunkirk coast? Or are we to read a scrap of backstory for Dawson in this particular flag? The Blue Ensign has a confused history, having been used through much of British history for a variety of purposes, and only someone with specialist knowledge would be able to interpret it. Most obviously it might simply identify Dawson as a member of the Royal Dorset Yacht Club, one of a number of such clubs with the right to use that flag. Alternatively, it might mark the Moonstone as being owned by a retired Navy man or a member of the Royal Navy Reserve. In any case, to the degree that anyone notices and interprets Dawson’s Blue Ensign, it motivates his skill as a seaman and his ability to rescue enough men to make an officer back in Weymouth exclaim in astonishment, “How many you got here?” as they disembark.

The use of variants of the Union Jack to create these little flashes of red hardly constitutes a riot of color, but it does effectively mark out the boats (one of which has a set of red sails) and to visually echo the cheers of the waiting soldiers as their saviors approach.

Incidentally, the Spitfires have orange-red dots at the centers of their surprisingly target-like decorations, creating a variant of the motif (below). The penultimate shot in the film lingers on Farrier’s Spitfire, which he destroys to prevent its falling into German hands, blazing away as the red of rescue grows bigger and brighter and comes to signify the defiance we hear as Tommy finishes reading Churchill’s speech–a speech that mentions sea, air, and land.

Whistler’s “Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Cremone Lights” is in the Tate, accession number N03420; “Nocturne: The Solent,” is in the Gilcrease Museum, accession number 0176.1185

You can find more of our thoughts on Nolan’s work in our book Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages, in our blog entry “Niceties,” and in our online article (originally in Film Art) on sound in The Prestige.

THE PRESTIGE, one way or another

DB here:

Thanks to our web tsarina Meg Hamel we have now posted an analysis of sound in Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige on our site. It sits along with others under the rubric Books>Film Art. Or you can go directly to it.

It was originally included in the last couple of editions of Film Art: An Introduction. Why is it here now?

One of the most original aspects of Film Art from the beginning (1979) was our belief that for each technique we surveyed (cinematography, editing, etc.) we provide one example of how the technique functioned either in an entire sequence or across a whole film, or both. This, we thought, would get beyond one-off technique-spotting (“The low angle makes him look powerful”) that was common in other texts.

For several editions our sound chapter examined a sequence from Bresson’s A Man Escaped, while tracing how its use of sound fitted into the film as a whole. But we were told that the example was becoming problematic for teaching, because students had trouble concentrating on the sound while reading subtitles. So we put the Bresson analysis up on this site and I wrote something new on The Prestige (still my favorite Nolan film).

It turned out very lengthy and somewhat more intricate than our other analyses, partly because of the plot’s boxes-in-boxes structure. (One guy reads another guy’s journal, in which he’s reading the first guy’s journal….) So, because we had to keep within space limitations, we replaced the Prestige analysis with a briefer one of sound in The Conversation, co-written with Jeff Smith. That film, to be fair, is probably more frequently taught than the Nolan.

On the bright side, I’m happy that the Prestige analysis is likely to find new readers by being openly available on the Net. Had things gone differently, we’d probably have adapted it into a chapter of Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages. But then you’d have to pay to read it, and now you have it for free.

Our new edition, number 11, of Film Art will be appearing early in 2016. Kristin, Jeff, and I have added some new things to it and its online progeny. We’ll be previewing more of it in the weeks to come. In the meantime, let’s just say FA 11 includes a new analysis of another film. Look at the cover below and guess which one.

Apart from our Nolan book and the entries it’s based on, I study another aspect of The Prestige here.

The sirens’ song for Oscar

The Lego Movie.

Another guest blog this week, this time from Jeff Smith, our colleague in the department here at UW–Madison. Jeff is one of America’s experts on movie music and sound technology. He contributed an entry on Atmos last year. He has written many articles on film sound, along with two books: The Sounds of Commerce and Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. He’s also our collaborator on the eleventh edition of Film Art: An Introduction.

‘Tis the season for Oscar buzz, and the media glut of award prognostications is already upon us. Most of the attention will go to the above-the-line talent who’ve received nominations (actors, directors, and screenwriters). The craft categories tend to get much less scrutiny, but the work of cinematographers, editors, and composers plays an equally important role in making their films award-worthy.

Today I offer some observations about this year’s nominees in the music categories: Best Original Score and Best Original Song. By using the nominees as examples, I hope to illuminate some of the ways that music continues to contribute to cinema’s narrative functions and its emotional impact on viewers. I’ll also offer my predictions for who will win at the end of each section.

Best Original Score

Even before this year’s nominees were announced, one of 2014’s most distinctive and innovative film scores was declared ineligible by the Academy. Antonio Sanchez’s driving percussion score for Birdman was disqualified under Rule 15, which states that scores “diluted by the use of tracked themes or other pre-existing music, diminished in impact by the predominant use of songs, or assembled from the music of more than one composer shall not be eligible.” Apparently, in the view of the Academy’s music branch, Birdman’s use of substantial excerpts of concert music by Mahler, Tchaikovsky, Ravel, and John Adams weakened the impact of Sanchez’s score. That explanation, though, probably doesn’t pass the eyeball (or eardrum) test of anyone who has seen Alejandro González Iñárritu’s film. Sanchez’s drum work adds verve and energy to several of the director’s elaborately choreographed (and seamlessly stitched together) long takes.

Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’s electronic score for Gone Girl was also a notable snub, especially since their bold, pathfinding music for The Social Network took home the top prize just four years ago. The fact that both of these scores failed to secure nominations may be a sign that the Academy’s music branch is returning to the verities of good old-fashioned melody and harmony as the basic tools in the composer’s kit.

That being said, the absence of Sanchez, Reznor, and Ross from the list of nominees doesn’t mean that the remaining scores are dull or unadventurous. Quite the contrary. Several of them push film composition in new and exciting directions. Their scores fulfill traditional functions but employ innovative scoring techniques and orchestrations.

Old sounds, new sounds

Take, for instance, Gary Yershon’s score for Mike Leigh’s biopic, Mr. Turner. Bypassing the conventions of orchestral writing for film, Yershon composed for a chamber-sized ensemble. Some cues combine a saxophone quartet with a string quintet, a musical choice that seems deliberately anachronistic. (As Yerson himself says in the soundtrack’s liner notes, Adolph Saxe’s invention wasn’t even patented until 1846, just a few years before Turner’s death.) Other cues add flute, clarinet, harp, tuba, or timpani to the mix. But these embellishments simply add color to the basic sound of Yershon’s twin string and saxophone ensembles.

Yershon says he was attracted to the saxophone due to its ability to glissando – that is, bend pitch from one note to another. Yershon certainly exploits this element of the instrument’s sound by building his melodies from long sustained notes that slowly take on serpentine shapes. Saxophone glissandi have an almost iconic function in the idioms of jazz and pop music . (Think of the opening phrase of Wham’s “Careless Whisper.”) In this case, though, the technique gives Yershon’s score a minimalist, modernist edge.

Yershon’s inclusion of a saxophone quartet departs from two norms: the period music of Turner’s time and the symphonic orchestrations that have characterized biopics for decades. The saxophone was never a major component of the Hollywood sound crafted during the studio era. Composers like Max Steiner and Victor Young occasionally included saxophones in their arrangements of music played onscreen by dance bands, but for the most part, their wind arrangements were for some combination of flutes, oboe, English horn, clarinets, and bassoons.

Is Yershon’s score inappropriate on historical grounds? I don’t think so. By modernizing the sound of Leigh’s period biopic, Yershon’s score adds a contemporary resonance, perhaps encouraging viewers to see parallels between Turner’s painting and the work of modern-day artists. Indeed, as Guy Lodge noted in his Hitfix review of the film, “It’s tempting, even, to view the film as biopic-as-self-portrait, revealing shades of one life through another. Leigh has a reputation for prickliness and resistance to self-explication; perhaps it’s not surprising that he’s long been fascinated by Turner’s allegedly gruff, taciturn genius.”

Yershon’s use of contemporary instruments may not in itself suggest those historical parallels. Indeed, most viewers probably have no idea when the saxophone was invented. But it certainly invites us to think about Leigh and Yershon’s reasons for opting for such a modern sound. And with its smaller instrumental forces, Yershon’s score resists some of the sweeping emotionalism that is found in other examples of the genre.

Zimmer pulls out all the stops

Hans Zimmer’s nomination for Interstellar is the tenth of his long and distinguished career. With all apologies to John Williams, Zimmer is arguably Hollywood’s leading film composer and his work is emblematic of a larger industry turn toward emphasizing musical tone and texture rather than big memorable themes. Zimmer’s score for Interstellar is no exception to this rule. In this case, though, much of the tone and texture is provided by the four-manual Harrison & Harrison pipe organ found in London’s Temple Church.

Director Christopher Nolan says that he liked the sound of the church organ as something that added an element of religiosity to Interstellar. But the organ contributes other things as well. For one thing, the organ’s booming bass register adds mass and heft not only to the music, but also to the astronomical bodies shown onscreen. The sheer size of these lower frequencies enhances the sense of scale in Nolan’s imagery. Thanks to the organ’s huge pitch range, the instrument’s upper register provides the quieter, swirling arpeggios needed to suggest the story’s filial bonds between father and daughter. At the same time, the instrument’s big, fat bottom end adds the musical bombast needed to convey the film’s epic visions of distant planets, wormholes, and alternate dimensions.

More important, despite the church organ’s strong association with sacred and liturgical music, Zimmer’s score never sounds like a Bach toccata. Rather, due to its repetitive, but intricate arpeggiations and simple, but affecting harmonic structures, Interstellar’s music has the kind of trippy, drone-ish, psychedelic feel that suggests both Terry Riley and Iron Butterfly. Zimmer’s score does not contain anything that is an obvious quote from the music of Stanley Kubrick’s “thinking man’s” sci-fi classic, 2001: A Space Odyssey. Yet, in its own way, Zimmer’s music recalls the period where such films were being produced, indeed the very kind of film that Nolan self-consciously tried to recreate.

In developing the score for Interstellar, Nolan and Zimmer also departed from the norms for director-composer collaborations. Most composers begin their work at a fairly late stage in the filmmaking process. In some cases, they may work from a completed script. In most cases, though, a composer starts with a rough cut of the film, making his or her contribution felt only during post-production.

In contrast, Nolan acknowledged that he has gradually been bringing Zimmer into his production at earlier and earlier stages. Nolan dislikes the practice of temp tracking, a technique that involves slugging in preexisting music that temporarily serves as a guide to the production team during the editing process. Says Nolan, “To me music has to be a fundamental ingredient, not a condiment to be sprinkled onto the finished meal.”

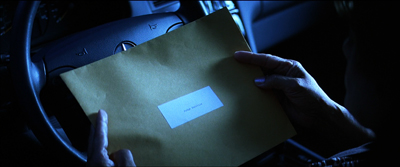

For Interstellar, Nolan asked to meet with Zimmer well before production began. As Nolan recounts in the liner notes to the soundtrack, he gave the composer an envelope containing a one-page summary of the fable that sat at the heart of the story. The description did not contain any details of the film’s genre or plot. Rather the summary simply laid out the narrative’s emotional core. Zimmer then took the summary and retired to his studio to start composing. Several hours later, Zimmer brought back a CD that contained about three or four minutes of music. Nolan listened to the new piece: a simple piano melody that nonetheless captured the feeling of what the director says he was “already struggling with on the page.”

When Nolan began shooting, he frequently listened to Zimmer’s simple piano piece, which functioned as a kind of “emotional anchor” for the film. Eventually, Zimmer returned to the studio and created the huge musical canvas that captures Interstellar’s heady exploration of space and time. Underneath it all, though, is the humble melody Zimmer wrote prior to production, the modest edifice upon which the rest of the score is built.

More songs about buildings and food service

Like Zimmer, Alexandre Desplat has several previous nominations to his credit, including those for the scores of Best Picture winners The King’s Speech and Argo. Unlike Zimmer, though, Desplat has yet to win. Among Hollywood’s current A-list composers, Desplat has shown extraordinary versatility. He’s at home writing for foreign art films, American indies, animation, and studio genre pictures. Desplat’s score for Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel is the third he has done for the director, following earlier collaborations on The Fantastic Mr. Fox and Moonrise Kingdom.

Here again, Desplat’s score for The Grand Budapest Hotel departs from established norms of Hollywood orchestration. Although he uses a slightly smaller version of the wind and brass sections usually found in older Hollywood film scores, he avoids the normal violins, violas and cellos. Instead he opts for a string section comprised of balalaikas, cimbaloms, zithers, mandolin, and acoustic guitar. This choice is intended to reflect the vaguely Mitteleuropean setting of the film. Just as the story is loosely inspired by the writings of Austrian novelist Stefan Zweig, the music reflects the social and geographical milieu of Zweig and his characters during the 1920s and 1930s. Eastern European and Russian folk melodies inspired much of Desplat’s. This combination of instrumentation and idiom creates a harmonic and timbral palette that proves to be enormously flexible in the composer’s hands, enabling him to add classical, modern, and jazz touches wherever they are needed.

Although Desplat employs unusual orchestration in The Grand Budapest Hotel, his score is fairly traditional in other ways. There are leitmotifs for several of the main characters, such as M. Gustave, Zero, Madame D., and Ludwig. An eight-measure theme is also linked to situations of adventure or danger. These themes and motifs tighten up the film’s structure. Such cues for patterning are particularly important when one considers The Grand Budapest Hotel’s “Chinese box” or “Russian doll” narrative construction, which nests stories inside stories.

Desplat’s score also captures the film’s dark yet whimsical tone. In interviews, the composer acknowledges that Bernard Herrmann and Carl Stalling were important influences on his work. At first blush, Herrmann, who composed several iconic scores for Alfred Hitchcock, and Stalling, who wrote crazy, almost manic music for Disney and Warner Bros. cartoons, would seem to occupy opposite corners of the universe. It’s to Desplat’s credit, though, that he is able to blend these diverse influences in a manner that is perfectly attuned to Wes Anderson’s imaginary “snow-globe” world. Indeed, the cue for the scene where Gustave is hanging from a cliff features harmony that would not be out place in Herrmann’s score for North by Northwest, an obvious inspiration.

But the mood is much lighter and airier in Anderson’s cliffhanger, partly because of the tenor established by Desplat’s music.

Scoring the Beautiful Minds of Cambridge

Ironically, Desplat’s chief competition may come from himself. Besides The Grand Budapest Hotel, Desplat also received a nomination for the fact-based espionage thriller, The Imitation Game. It was the fourth time in the last fifteen years that a single composer received two Oscar nominations for Best Original Score. And like the other nominees discussed here, Desplat developed an unusual compositional technique for the film, allowing for an element of randomness to determine his score’s final musical shape.

Whereas Sanchez deviated from compositional norms by improvising beats for Birdman, Desplat’s score for The Imitation Game pushes the envelope by featuring three computerized pianos, which sometimes play random patterns of preprogrammed music. According to the composer, the pianos’ fast, complex combinations not only underscore the urgency of the Bletchley Park team’s search for a solution to the Nazis’ Enigma code, but they also function as an musical correlative of cryptanalyst Alan Turing’s thought processes. As director Morton Tyldum put it, he wanted the music to seem subjective, as though it was conveying the mental operations inside the head of an awkward, but brilliant mathematician.

Desplat’s use of rapid scales and arpeggios to represent Turing’s genius actually recalls Philip Glass’ score for Errol Morris’s documentary about Cambridge physicist Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time. To be fair, Glass’ compositional style has employed these kinds of musical textures in many other types of cinematic contexts. Glass’s work not only appears in other Morris films, but also in biopics about Japanese writer Yukio Mishima and the Dalai Lama, and even in horror films and dramas, such as Candyman and The Hours. Given the constancy of his compositional proclivities, it is perhaps easy to make too much of Glass’s ability to depict the depth and brilliance of Hawking’s intellect. Yet there is little question that Glass’s music adds both a sense of mystery and majesty to Morris’s imagery, which itself explores such imponderables as the nature of time and the origins of the universe.

Because of this precedent, it is perhaps doubly striking that composer Johann Johannson took such a different tack in his music for the Hawking biopic, The Theory of Everything. With long sustained string lines and simple piano melodies, Johannson aims for a soft lyricism that is intended to add both pathos and subdued passion to the film’s depiction of Hawking’s relationship with his wife Jane. Since the film is based on Jane’s account of their marriage, it is probably not surprising that Johannson’s score plays her point of view even more than it does that of its putative subject. As the composer explains, the “heart of the film is the love story: Stephen and Jane, Jane and Jonathan. That’s really what the music needed to capture.” Thanks to Johannson’s use of harpsichord, celeste, harp, and guitar, the tone colors of the music remain light, making his score for The Theory of Everything a modern counterpart to the work of the Georges Delerue.

Prediction

All five nominees are quite worthy of the award for Best Original Score. But, if I had the opportunity vote, I would probably cast it for The Grand Budapest Hotel. Not only is Desplat’s score perfectly attuned to Wes Anderson’s distinctive style, but it would be nice to see the composer recognized for the overall quality of his oeuvre. Desplat’s fans, though, probably split their votes between The Grand Budapest Hotel and The Imitation Game, thereby increasing the chances that he’ll once again go home empty-handed.

In underlining The Theory of Everything’s romance plotline, Johansson’s score is perhaps the most traditional among the five nominees. I don’t believe, though, that its adherence to longstanding film score conventions will hurt it on Oscar night. Johansson’s sweet lyricism already carried the day at the Golden Globes, an award that has correctly predicted the eventual Oscar winner four out of the last five years. Although there could be an upset in this category, I expect we’ll see Johannson triumphantly hoist the little gold man over his head come Sunday night.

Best Original Song

If recent award ceremonies are any indication, this is a category that has fallen a bit on hard times. At least this year, there are five legitimate nominees. Last year one of the nominees was disqualified, and in 2012 and 2011, the category fielded only two and four nominees respectively.

One potential reason for the paucity of original songs may be the previously mentioned turn toward tone and texture in contemporary scoring practice. In the old days, many of the best-remembered and best-loved songs from the movies were crafted from themes specifically composed for the score. This was the case with tunes like Alfred Newman and Frank Loesser’s “Moon of Manakoora” from The Hurricane, Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer’s “Days of Wine and Roses,” or even James Horner and Will Jennings’s “My Heart Will Go On” from Titanic. Since current film composers are turning away from big themes, it seems there is less opportunity to adapt a musical motif into something that works as a theme song. (Of course, there are occasional exceptions. In 2013, Adele and Paul Epworth took home the Oscar for Skyfall, updating the established formula for making Bond theme songs.)

This year’s nominees also lack anything resembling last year’s heavyweight battle between Frozen’s “Let It Go” and Despicable Me 2’s “Happy.” All of the nominees seem quite worthy. None of them, though, has created the kind of cultural ubiquity enjoyed by Idina Menzel’s and Pharrell Williams’s chart-topping singles.