Archive for the 'Directors: Godard' Category

Pixels into print: The unexpected virtues of long-winded blogging

Penance (2013).

DB here:

Remember Web 1.0, when blogs were really logs? You know, diary-like accounts of events befalling the writer? The sense that every instant of one’s life needs preserving and broadcasting got absorbed into Facebook and Twitter and Instagram, I suppose. Today blogs are more likely to feature essayistic thinking. People slow-cook their blogs more, it seems to me, and they write in a reflective mode. Since our blog has always been, um, expansive in such ways, I welcome the Ruminative Turn.

Like most academics, we write long for a reason. You need more words to dig into a question. That’s why books exist. But mid-range is good too. The blog format suits specualtive, exploratory work and informal prose that wouldn’t show up in a journal. In this para-academic register, the aim is to spread ideas and information around. A reviewer of the book I mention below puts it well: “democratic, attainable erudition.”

Because we write long, and maybe because we’re a bit chatty, a few of our entries have become published, suitably spruced up, as “real” articles for diverse audiences. Some overseas journals, both print and online, have published translations of pieces available here. Thanks to the good offices of the University of Chicago Press, a gaggle of our entries became a book, Minding Movies. Lately, three of our blogs have wriggled their way into paper—two as DVD liner notes, and a third in an imposing rectangular solid that is sort of a mega-book. All are aimed beyond the academy.

Doing Penance

Two summers ago our friend Gabrielle Claes tipped me to a visit by Kurosawa Kiyoshi, accompanying a screening of his Penance (Shokuzai) at the Brussels arthouse Cinéma Vendôme. Of course we went, and we had a good time with the film and the Q & A that followed. I duly wrote it up, did a bit of quick analysis, and offered it to the world online.

When the Doppelgänger branch of Music Box Films decided they wanted to distribute Penance on DVD, they asked for the essay. The it’s come out in a good edition (alongside Eddie the Sleepwalking Cannibal, worth a look, and other genre fare). My essay is preceded by one by Tom Mes of Midnight Eye, who discusses the film’s relation to its source novel and pinpoints its exploration of “the gray area between the mundane and the ghastly.” there’s also an informative interview with Kurosawa.

As a five-part TV series, Penance fits its plot to the installments pretty rigorously. A little girl is assaulted and murdered, and only her four playmates have seen the killer. Taking advantage of the serial structure, Kurosawa begins each episode by revisiting the original crime, picking details relevant to what we’ll see but expanding the sequence a bit by tracing each girl’s efforts to notify the community. It’s a sophisticated version of the “Previously on [name of series]” recaps we commonly get in TV serials.

After revisiting the killing and showing the aftermath as it affects each girl, every installment shows the children gathering for a grim birthday party. On that occasion Emiri’s mother Asako demands that the girls either find the killer or do penance for their lack of vigilance.

After this juncture, each of the first four installments attaches the narration to one girl’s viewpoint fifteen years later. The episodes trace the awful effects of the crime on the girls’ personalities and their adult lives. Each one gets involved with an unstable man, with catastrophic consequences. In each episode, Asako reappears at a critical moment to demand penance or to absolve the woman. The fifth episode centers on Asako herself: her immediate reaction to her daughter’s death, her search for the killer, and her realization that the crime has roots in her own past.

I was happy to get a chance to see Penance again, because it’s continually engrossing and quite moving. It also exemplifies the sort of clean, classical genre filmmaking that doesn’t get done in America very much. After watching all the GPS views and whooshes down to street level and nonstop bludgeoning supplied by Run All Night (still, an okay movie), it’s a pleasure to turn to a film that builds its tension through a fixed camera, calm clarity, and performances suggesting suppressed menace rather than explosive confrontations–though there are a few of those too.

Penance would be something for young filmmakers to study. It shows how locations can be used elegantly and economically, and how the inability to get extreme long shots in cramped quarters can actually be an advantage. Classrooms, offices, and gymnasiums are used with a sober restraint, each one given defining geometry and color scheme. A crucial confession takes place in a police station being renovated, and Kurosawa lets the scene unfold in a way that continually reveals surprising bits of space, such as a cop standing somewhat ominously at a distance. He’s unafraid of holding long shots because the shot is propelled by the drama, not the cutting pace. Here’s another example that illustrates the Monroe Stahr rules of storytelling: not a car chase or gun battle, but a quietly puzzling situation that evokes curiosity and suspense.

Asako has gone to a drawer and withdrawn a ring. We’ve not seen it before and have no idea what it signifies.

She crosses the room, as if to do something with it. Before we find out, cut to her husband in the hallway. This cut initiates a take lasting over three minutes.

When he reaches the doorway he catches her hurling it angrily into the wastebasket. So now we know he knows…but what?

Reminding her that she’s treasured this since college, he fetches it out for her and quietly leaves.

As she starts to explain, she follows him into the corridor. The camera pans right to reframe their new confrontation.

There she reveals her secret, slowly. As she crumples to the floor, Kurosawa permits himself a camera bobble–a rarity in a film that almost entirely avoids handheld camerawork. The husband at first consoles her…

…but then she confesses her secret. He pulls away from her.

She tries to embrace him, looking for solace, but he shuts her out and withdraws.

She’s left to fall to the floor crying in shame, in that classic attitude of distraught Japenese women.

The highest pitch of the drama–Asako’s revelations–has been given a close view, but the action has led up to it and away from it through character blocking, not cutting. The situation unrolls and builds tension completely through dialogue, body language, and facial reaction. But it could hardly be considered theatrical, because the camera has judiciously strengthened certain parts, concealed others, and obliged us to shift character perspective (Asako-husband-Asako) through slight changes of position. And playing so much of the scene in distant and dorsal shots harks back, inevitably, to Mizoguchi.

As I mentioned in the early entry and the liner notes, Kurosawa always knows where to put the camera–no small accomplishment these days–and there’s as much power in this apparently simple scene as in any of the grandiose Steadicam movements in more inflated films. Trust the audience to sense the undercurrents, and they will follow you if you have mastered calm, precise cinematic storytelling.

Grand hotellerie

The Doppelgänger gang released Penance on DVD last November. I’m only a little less late in mentioning the arrival of Matt Zoller Seitz’s newest addition to The Wes Anderson Collection: The Grand Budapest Hotel. The decision to base a big, luscious book on a single Anderson film gives this ambitious picture even deeper treatment than we saw in the Collection’s individual chapters. From Seitz’s rich opening appreciation to the amiable list of contributors (The Society of Crossed Pens), the book is a serious divertissement, a wonder-cabinet of images, ideas, and semi-childish fun.

It’s partly a making-of book. We get production stills, script pages, set designs, storyboards, animatics, special-effects secrets, costume designs, and the now-celebrated photochrom images. Seitz has larded his captions with shrewd critical points about lenses, compositions, lighting, and staging—not the normal gee-whiz commentary of an “authorized” making-of. Anderson’s enjoyment of practical effects, his judicious use of digital tools, and his most complex voice-over narration yet come through vividly.

Seitz is especially interested in the history and artistic models behind the movie. His interviews are crowded with information about Anderson’s inspirations, which seem endless. Of course there is Stefan Zweig, who is given several pages of intense discussion. We also learn of Anderson’s interest in the exiled directors like Lubitsch and Wilder, who gave us both a Europeanized Hollywood and a Hollywoodized Europe. There are homages to The Red Shoes and Colonel Blimp and Letter from an Unknown Woman. Anderson was equally committed to a broader historical context, passing his story through different eras—the bell-jar atmosphere before the Great War, the premonitions of World War II (itself never shown), and the postwar emergence of Communism, seen in the revamped and decaying Hotel in the 1960s. Seitz has even spotted borrowings from James Bond movies. As skillful an interviewer as he is graceful an essayist, Seitz induces Anderson to reveal the density of this sweet, sinister movie—the cinematic equivalent of Chandler’s line about a tarantula on a slice of angelfood cake.

There are as well interviews with Ralph Fiennes talking of the “farce spectrum,” costume designer Milen Canonero ordering up a Prada leather coat for Willem Dafoe, the very great composer Alexandre Desplat explaining his compositional procedures, production designer (and Milwaukee native) Adam Stockhausen discussing the magnificent settings, and DP Robert Yeoman talking about shooting on 35mm.

There are as well interviews with Ralph Fiennes talking of the “farce spectrum,” costume designer Milen Canonero ordering up a Prada leather coat for Willem Dafoe, the very great composer Alexandre Desplat explaining his compositional procedures, production designer (and Milwaukee native) Adam Stockhausen discussing the magnificent settings, and DP Robert Yeoman talking about shooting on 35mm.

Anderson’s fussbudget aesthetic meets its match in a book crammed with fastidious minutiae. Whimsy, as Lewis Carroll and G. K. Chesterton understood, escapes coyness only when it’s pursued rigorously. Seitz reviews the careers of the major players in postage-stamp pasteups. When Anderson is revealed as a connoisseur of frame stories, flashbacks, and other fancy techniques we favor on this site, Seitz provides a four-page spread of pick hits of voice-over. Max Dalton, the illustrator, gets the message. With their modestly lowered eyes and sidelong grins, his neo-New Yorker figures swarm these pages but assemble, obediently rank and file, in the end papers.

Most surprising of all for a production dossier, in-depth criticism is not only allowed in the tent but given its turn in the spotlight. Christopher Laverty analyzes the costumes with a precision seldom seen in academic writing, while Olivia Collette contributes an enlightening study of Desplat’s score. Steven Boone examines the art direction, with a special sensitivity to how set designs are fitted to anamorphic optics. Ali Arikan brings his characteristic lucidity to a study of Zweig’s Vienna and the traces it leaves on his fiction and Anderson’s film. The essays show that analytical film books, like volumes of academic art history, can be merit high production values.

My contribution, a revamping and nuancing of an earlier blog entry, looks at how Anderson adjusts his planimetric staging and shooting to different aspect ratios. For me, this assignment was the big time. No academic book, my usual publishing platform, could have illustrate my ideas so splendidly. I’m proud to be among fine company, and I like the fact that people are reading and buying the thing.

Of course very few film books have the built-in audience of a Wes Anderson project. As I wrote last summer, he brings his brand with him. But that isn’t, I think, a bad thing when the results are as lively and lovely as The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Last year I had to go to Hong Kong the weekend the film opened. I dashed to it during my first day in town, then squeezed in two more screenings during the festival. Now, after a year and many more viewings, it hasn’t cracked yet. At the moment I think of it in relation to the “hotel” books and movies of the 1920s and 1930s. I think of its predecessors, such as Arnold Bennett’s 1902 novel The Grand Babylon Hotel. (Did Anderson read it? I don’t find a mention here.) I remember those star-filled ensemble comedies of the 1960s like The Pink Panther and The Great Race, twitching with celebrity walk-ons and the cartoonish effects Anderson relishes. In short, I think about film history, and it pleases me when a film and its book trace out, in dazzling detail, an exceptional movie’s debts to tradition. Keep your Birdman and Gone Girl and Jersey Sniper (or is it American Boys?): This is the 2014 American film that will be remembered for decades.

Hello again, my language

Last year’s other big film for the future is, no doubt now, Adieu au Langage, just coming out on Blu-ray as Goodbye to Language from Kino Lorber. I’ve said my say about this item twice (here and here) so about all I have to add is that after several more viewings, I’m still convinced of its excellence. Kino Lorber gives us two versions, the 3D one and the “merged” 2D one. The 2D one is still one hell of a film, but of course in 3D it’s spectacular.

The disc includes an essay developed beyond my blog entries. It says some new things, but it’s inevitably incomplete. Godard’s films so teem with ideas (both intellectual and cinematic) that there’s almost always more to notice. “One can put everything in a film,” he remarked back in the 1960s. “One must put everything in a film.” He sort of does, especially here.

Both versions belong on every cinephile’s shelf. If I didn’t already have a 3D TV (purchased so I could watch Dial M for Murder and Gravity properly, and even freeze the frame), I’d get one so I could see Farewell to Language whenever I wanted. Consider your options. 3D TV is now dead enough to be cool.

Thanks to Austin Vitt of Music Box films for picking up Penance, and Richard Lorber and Robert Sweeney for recruiting me for the Godard disc. I’m indebted to Matt Zoller Seitz for bringing me on board the Anderson project, and to Caitlin Robinson of Twentieth Century Fox for loaning me a print of The Grand Budapest Hotel so that I could study its aspect ratios in their natural habitat.

Midnight Eye features Kohei Usuda’s very detailed review of Kurosawa’s latest project, an entry in the “idol movie” genre. You can find MZS’s video introducing the Grand Budapest book here.

Goodbye to Language.

Say hello to GOODBYE TO LANGUAGE

DB here:

Godard is making trouble again. Adieu au langage–known now as Goodbye to Language– is doing better in the US than any of his films have done in the last thirty-some years. It has a per-screen average of $13,500, which is about twice that attained by Ouija in its opening last weekend.

But that average represents only two screens, and it’s going to be hard to expand because Goodbye to Language is in 3D. Many art houses would love to play it, but they lacked the money to upgrade to 3D during the big digital conversion of recent years. Even high-powered venues in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago don’t have 3D installed. Here in Madison we’re showing it as a benefit for our Cinematheque. But the film’s prospects may be brightening.

Re-seeing it (twice) at the Vancouver International Film Festival back in September, I was struck by a few more ideas about it. Kristin and I avoid listicles, but after writing an expansive entry on the film, all I’ve got at this point is some scattered observations. Two ragtag comments are semi-spoilers, and I’ll warn you beforehand.

The Power of post As far as I can tell, Godard hasn’t used the converging-lens method to create 3D during shooting. Instead of “toeing-in” his cameras, he set them so that the lenses are strictly parallel. He and his DP Fabrice Aragno apparently relied on software to generate the startling 3D we see onscreen.

This reminds me that postproduction has long been a central aspect of Godard’s creative process. Of course he creates marvelous shots while filming, but ever since Breathless (À bout de souffle, 1960), when he yanked out frames from the middle of his shots, he has always made post-shooting work more than simply trimming and polishing. His interruptive aesthetic is made possible by editing that wedges in intertitles (sometimes the same one several times). He breaks off beautiful shots and drops in bursts of music that snap off just before they cadence.

In both sound and image, the post-production process for Godard is a kind of transformation, an openly admitted re-writing of what came from the camera. He slaps graffiti on his own film. In Narration in the Fiction Film, I argued that our sense of a Godard film being “told” or narrated by the director proceeds partly from his ability to create the impression of a sort of Cineaste-Emperor, a sovereign master who is governing what we see and hear at any given moment. The collage principle suggests someone behind the scenes pasting these fragments together. Not only his commentary (once whispered, now croaked) but every shot-change and bit of music and noise, every intertitle and look to the camera all bear witness to Godard as God. Before he cut a strip of film; now he twiddles a knob or guides a slider. In all cases, we still feel his playful, exasperating hand.

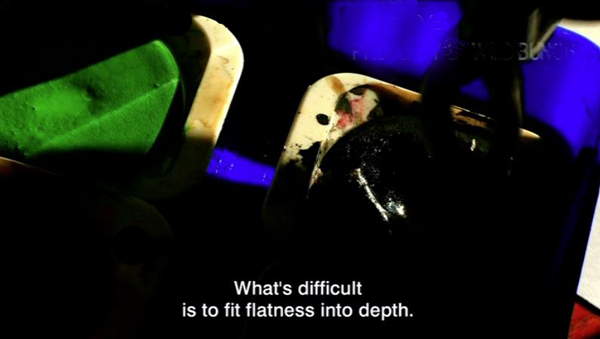

Godard’s famous collage aesthetic relies on aggressive changes to image and sound in postproduction that all but deface the surfaces of his movie. No surprise, then, that Godard 3D lays out those surfaces boldly, with distant planes sharply edged and volumes that stretch out before us.

Yet with his superimposed titles, sometimes hovering among the audience, he can flatten volume and stack up planes like playing cards. It’s partly a joke that the 2D title below is closer to us than the 3D one behind it, but even that sticks out further than the unidentifiable light array that is farthest away.

The Rule and the exception. Just as Hollywood cinema erected rules for plotting, shooting, and editing, it has cultivated rules for “proper” 3D filming. An informative piece by Bryant Frazer points out some ways that Godard breaks those rules. Still, just calling him a maverick makes him sound merely willful. Part of his aim is to explore what happens if you ignore the rules.

This is Godard’s experimental side: He considers what “good craftsmanship” traditionally excludes, just as the Cubists decided that perspective, and smooth finish, and other features of academic painting blocked off some expressive possibilities. To get a positive sense of what he’s doing, we need to understand what the conventional rules are intended to achieve. Consider just two purposes.

1. 3D, the rules assume, ought to serve the same function as framing, lighting, sound, and other techniques do: to guide us to salient story points. A shot should be easy to read. When 3D isn’t just serving to awe us with special effects, it has the workaday purpose of advancing our understanding of the story. So, for instance, 3D should use selective focus to make sure that only one figure stands out, while everything else blurs gracefully.

But 3D allows Godard to present the space of a shot as discomfitingly as he presents his scenes (elliptical, they are) and his narrative (zigzag and laconic, it is). As in traditional deep-focus cinematography, we’re invited to notice more than the main subject of a shot, but here those piled-up planes have an extra presence, and our eye is invited to explore them.

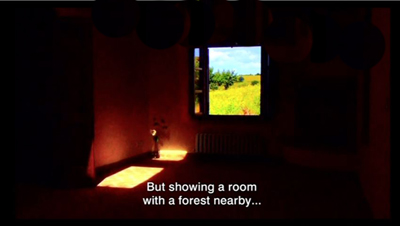

2. According to the rules, 3D ought to be relatively realistic. Traditional cinema presents itself as a window onto the story world, and 3D practitioners have spoken of the frame as the “stereo window.” People and objects should recede gently away from that surface, into the depth behind the screen. But Adieu au langage gives us a beautiful slatted chair, neither fully in our lap nor fully integrated into the fictional space. It juts out and dominates the composition, partly blocking the main action–a husband bent on violence hustling out of his car.

That chair, or one of its mates, reappears, usually with greater heft than the human characters shoved nearly out of sight behind it.

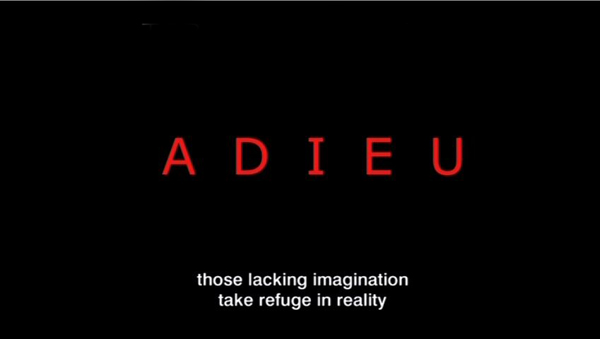

In sum, visual realism of the Hollywood sort is only one mode of moviemaking. Godard lets us know from the very start that he’s after something else. The film’s first title announces: “Those lacking imagination take refuge in reality.” Goodbye to Language is an adventure of the imagination.

Innovation, intractable. Godard has been around so long that some of his innovations—jump-cuts, interruptive intertitles—have become common in mainstream movies. But there remains an intractable core that is just too difficult to assimilate, and he has always been a few jumps ahead of people who want to de-fang his experiments.

Supposedly Picasso told Gertrude Stein: “You do something new and then someone comes along and makes it pretty.”

A fresh eye. French thinkers have long pondered the possibility that language separates us from the world. It drops a kind of scrim that keeps us from seeing things in their innocent purity. Given the film’s title, I suggested in an NPR interview that Godard’s use of 3D, along with the insistence on the dog Roxy, is aiming to make us perceive the world stripped of our conceptual constructs (language, plot, normal viewpoints, and so on). Personally, the idea that language alienates us from some primordial connection to things seems to me implausible, but I think it’s a central theme of the film. This very talky movie exploits a paradox: we must use language to say goodbye to it.

Learning curve. Critics put off by Godard, I think, have too limited a notion of what criticism is. They seem to think that their notion of cinema, fixed for all time, is a standard to which every movie has to measure up. They are notably resistant to a simple idea: We can learn something from films. Not only can we learn things about life but we also learn things about cinema. We learn things that we never realized that film can do.

But then, how many critics actually want to learn something about cinema, which can only happen the way we learn anything: by wrestling with something that strikes us as difficult?

Two soft spoilers ahead!

On re-viewing, I was struck by other ways in which the two long parallel stories echo one another: a big bowl of flowers, later one of fruit; the repetition of “There is no why!”; and an odd colorless or nearly colorless image of each principal woman.

As with so much else in the film, Godard posits his own slippery version of a parallel-universe plot, and this overall formal option is underscored by these stylistic choices. In the first prologue, the woman on the left above is also given to us in a color shot, as if the disparity color/black-and-white points ahead to the nearly black-and-white color shot to come.

The (apparent) deaths of the principal men are rendered very obliquely, but apparently out of story order. This juggling with chronology, a staple of modern cinema, is fairly rare in Godard, at least as I recall.

Clearly, 3D is becoming something we cinephiles need to face up to. I balked at the beginning, but I’ve come around. Important filmmakers like Godard, Herzog, and Wenders are working with it. Just as important, we’ve never until now been able to study 3D movies closely. I remember watching Bwana Devil and others on a flatbed in the Library of Congress in the early 1980s, but if I stopped on any frame, I couldn’t tell what the 3D effect was like. Of course any 2D print of a classic 3D title represents only one camera’s view.

The victory of digital projection yielded a benefit I hadn’t foreseen when I wrote Pandora’s Digital Box. After Dial M for Murder came out in BD in 2012, I realized I needed to upgrade. We bought a bargain TV and BD player just when 3D TV had been declared dead. Now our 3D collection has expanded to include Hong Kong titles as well as favorites like Wreck-It Ralph, Gravity, and A Very Harold and Kumar 3D Christmas. Costs of 3D discs are sometimes low, and while you need a bigger monitor than we have to approach the force of a big-screen viewing, we can at least study a director’s use of the format frame by frame.

So for viewers who can’t get to Goodbye to Language in theatres but who have a 3D TV may take heart: Kino Lorber will be releasing a 3D Blu-ray disc.

Vadim Rizov has a brief but intriguing interview with Aragno in Filmmaker Magazine. “”Hollywood says you shouldn’t have more than six centimeters between cameras, so I began at twelve to see what happened.” Obviously a simpatico collaborator.

I discuss aspects of Hitchcock’s use of 3D in Dial M for Murder here.

P.S. 4 November 2014: The distribution of Goodbye to Language has become a cause célebre. Justin Chang surveys the situation in Variety.

P.P.S. 13 November 2014: Geoffrey O’Brien’s enthusiastic appreciation of the film not only illuminates it but conveys the excitement of seeing it.

P.P.P.S. 14 November 2014: Two more thoughts, after seeing the film again last night at our Cinematheque screening. First, the “unidentifiable light array” I mention above is actually on the cover of the French edition of A. E. Van Vogt’s The World of Null-A shown later in the film. Second, this time I noticed that the war imagery in the film’s first part subsides in the second, to be replaced, it seems, by Roxy’s wanderings–a more lyrical, peaceful counterweight to the horrors invoked earlier. The pivot would seem to be the first helicopter crash at the end of the first part. There among the flaming ruins we can see the burned head of a dead dog. Roxy’s proxy? Anyhow, the original survives, exuberantly, in the film’s second long part.

Goodbye to Language.

ADIEU AU LANGAGE: 2 + 2 x 3D

Adieu au langage (2014).

DB here:

Godard’s Adieu au Langage is the best new film I’ve seen this year, and the best 3D film I’ve ever seen. As a Godardolater for fifty years, I’m biased, of course. And I might feel that I have to justify taking a train from Brussels to Paris to watch it (twice). But the film seems to me superb, and it gets better after several more (2D) viewings.

People complain that Godard’s movies are hard to understand. That’s true. I think they provide two different sorts of difficulty. He lards his dialogue and intertitles with so many abstract (some would say pretentious) thoughts, quotations, and puns that we’re tempted to ask what he is implying about us and our world. That is, he poses problems of interpretation—taking that to mean teasing out general meanings. What is he saying?

I think that this type of difficulty is well worth tackling, and critics haven’t been slow to do it. Scholars have diligently tracked the sources of this image or that barely-heard phrase. Adieu au langage provides another field day; there are movie clips, some quite obscure, and citations (maybe some made-up ones) to thinkers from Plato and Sartre to Luc Ferry and A. E. van Vogt. Ted Fendt has discovered a massive list of works cited in the film, and even his list, he acknowledges, is incomplete.

I confess myself less interested in interpretive difficulties. I don’t go so far as my friend who says, “Godard is a poet who thinks he’s a philosopher.” But I do think that he uses his citations opportunistically, scraping them against one another in collage fashion. In particular, I think that by having characters quote, quite improbably, deep thinkers, he’s trying for a certain dissonance between the abstract idea and the concrete situation.

What situation? That brings us to the second sort of difficulty. It’s often rather hard to say just what happens, at the level of plot, in a Godard film. From his “second first film,” Sauve qui peut (la vie) (1980), “late Godard” (which has lasted over thirty years, much longer than “early Godard”) has made the story action quite hard to grasp. Oddly enough, most reviewers pass over these difficulties, suggesting that story actions and situations that we scarcely see are fairly obvious. (Reviewers do have the advantage of presskits.)

The brute fact is that these movies are, moment by moment, awfully opaque. Not only do characters act mysteriously, implausibly, farcically, irrationally. It’s hard to assign them particular wants, needs, and personalities. They come into conflict, but we’re not always sure why. In addition, we aren’t often told, at least explicitly, how the characters connect with one another. The plots are highly elliptical, leaving out big chunks of action and merely suggesting them, often by a single close-up or an offscreen sound. Godard’s narratives pose not only problems of interpretation but problems of comprehension—building a coherent story world and the actions and agents in it.

We ought to find problems of comprehension fascinating. They remind us of storytelling conventions we take for granted, and they push toward other ways of spinning yarns, or unraveling them.

Case in point: Adieu au langage.

Since the film will be appearing in the US this fall, under the title Goodbye to Language, I want to encourage people to see this extraordinary work. But I’m also eager to talk about it in detail. So here’s my compromise, a four-layered entry.

I’ll start general, with some sketchy comments on some of Late Godard’s narrative strategies. In a second section I make some speculative comments on Godard’s use of 3D. No real spoilers here.

Then I’ll offer an account of the opening fifteen minutes. If you haven’t yet seen the film, this section might be good preparation. But part of experiencing the film is feeling a bit at sea from the start, so this section might make the film more linear than it would appear on unaided viewing. You decide how much of a preview you want.

The last section briefly surveys the overall structure of the film, and it is littered with spoilers. Best read it after viewing.

Spoilers notwithstanding, nothing stops you from eyeing the pictures.

Ecstasy of the image

Film Socialisme (2010).

Much in Adieu au langage is familiar from other Godard films. There are his nature images–wind in trees, trembling flowers, turbulent water, rainy nights seen through a windshield–and his urban shots of milling crowds. All of these may pop in at any point, often accompanied by fragments of classical or modern music. Again he returns to ideas about politics and history, particularly World War II and recent outbreaks of violence in developing countries. His standard techniques are here too. The film begins before, and during, the credits, which appear in brusque slates often too brief to read. Music rises, often just enough to cue an emotional response, before being snapped off by silence or an abrasive noise.

In his narrative films, as opposed to the collage essays like Histoire(s) du cinéma, we get scenes, but those are handled in unusual ways. He tends to avoid giving us an establishing shot, if we mean by that a shot which includes all the relevant dramatic elements. He often has recourse to constructive editing, which gives us pieces of the space that we are expected to assemble. Although Godard’s early films relied on this a fair amount, it became pronounced in his later work, where he tweaks constructive cutting in unusual ways. I discuss one example here.

Often we get an image of one character but hear the dialogue of an offscreen character. And the shot of the lone character may hang on quite a while, so that we wait to see who’s speaking. By delaying what most directors would show immediately, Godard creates, we might say, a stylistic suspense. I can’t prove it, but I suspect the influence of Bresson, who said to never use an image if a sound will suffice.

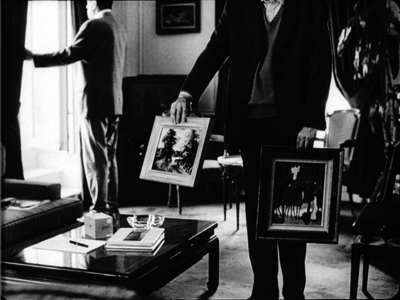

When Godard doesn’t give us unanchored close-ups or medium-shots, he may do something more drastic. A signature device of his later work is the shot which stages its action in ways that make the characters hard to identify. He may shoot in silhouette (Notre musique, 2003).

More outrageously, he may frame people from the neck or shoulders down (Bresson again?) and make us wait to discover who they are (Éloge de l’amour).

Such decapitated framings are disconcering, since orthodox cinema highlights faces above all other body areas. When we can’t access facial expressions, then the dialogue, gestures, postures, and clothes become very important. Godard can, of course, combine these strategies (below, Éloge de l’amour; also the Film Socialisme image above). In this shot, the man standing in the background is an important character but we never see him clearly.

Godard’s opaque “establishing” shots may be very condensed and laconic; he jams in a lot of information, partial though it is. In one shot of Adieu au langage, a dog approaches a couple on a rainy night and the woman urges her partner to take him in. All we see, however, is the man gassing up the car (and we don’t see him all that clearly).

We hear (dimly) the dog’s whimpering and the woman’s plea, but we see neither one.

Godard frets and frays his scenes in other ways. He creates ellipses, time gaps between shots that may leave us uncertain. What happened in the interval? How much time has passed? He also interrupts the scene through cutaways to black frames, objects in the scene, or landscapes; the scene’s dialogue may continue over these images, or something else may be heard.

At greater length, the scene can open up onto a digression, a collage of found footage, intertitles, or other material that seems triggered by something mentioned in the scene. In Film Art: An Introduction, we argued that one alternative to narrative form is associational form, a common resource of lyrical films or essay films. Godard embeds associational passages in his narratives, the way John Dos Passos embedded newspaper reports in the fictional story of his USA trilogy. Sometimes, though, the associations are textural or pictorial. At one point in Adieu au langage, Godard associates licked black brushstrokes on a painting with churned mud and the damp streaks on the coat of the dog Roxy.

By fragmenting his scenes, Godard gets a double benefit. We get just enough information to tie the action together somewhat, and our curiosity about what’s happening can carry our narrative interest. But the opaque compositions and the bits and pieces wedged in call attention to themselves in their own right. Blocking or troubling our story-making process serves to re-weight the individual image and sound. When we can’t easily tie what we see and hear to an ongoing plot, we’re coaxed to savor each moment as a micro-event in itself, like a word in a poem or a patch of color in a painting.

But those images and sounds can’t be just any image or sound; they hook together in larger patterns that sometimes float free of the plot, and sometimes work indirectly upon it. The best analogy might be to a poem that hints at a story, so that our engagement with the poetic form overlaps at moments with our interest in the half-hidden story.

Where, some will ask, is the emotion? We want to be moved by our movies. I suggest that with Late Godard, we are mostly not moved by the plot or the characters, though that can happen. What seizes me most forcefully is the virtuoso display of cinematic possibilities. The narrative is both a pretext and a source of words and sounds, forms and textures, like the landscape motifs that painters have used for centuries. From the simplest elements, even the clichés of sunsets and rainy reflections, the film’s composition, color, voices, and music wring out something ravishing.

We are moved, to put it plainly, by beauty–sometimes exhilarating, sometimes melancholy, often fragmentary and fleeting. Instead of feeling with the characters, we feel with the film. For all his exasperating perversities, Godard seeks cinematic rapture.

3D on a budget

The smallest set of electric trains a boy ever had to play with? Photo: Zoé Bruneau.

Most of the 3D films I’ve seen strike me as having two problems.

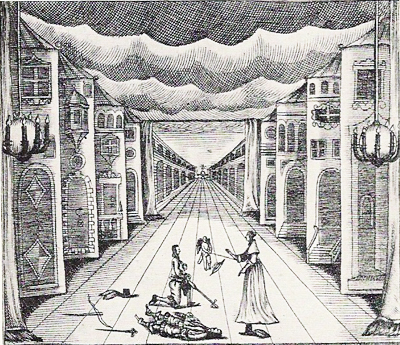

First, there is the “coulisse effect.” Our ordinary visual world has not only planes (foreground, background, middle ground) but volumes: things have solidity and heft. But in a 3D film, as in those View-Master toys, or the old stereoscopes, the planes we see look like like cardboard cutouts or the fake sections of theatre sets we call flats or wings (coulisses). They lack volume and seem to be two-dimensional planes stacked up and overlapping. Here’s an example from a German stage setting of 1655, with the flats painted to resemble building facades.

In cinema, the thin-slicing of planes seems to me more apparent with digital images that are rather hard-edged to begin with. (3D film was more forgiving in this respect.) Sometimes the flat look can be quite nice, as in Drive Angry (2011). In this action sequence, the planes prettily drift away from one another, with no attempt to suggest realistic space.

Apart from the coulisse effect, there’s the problem that the 3D impression wanes as the film goes along. I’ve long thought it was just me, but other viewers report perceiving the depth quite strongly at the start of the movie and then sensing it less after a while, and maybe not even noticing it unless some very striking effect pops up. Part of this is probably due to habituation, one of the best-supported findings in psychology. Maybe, as we get accustomed to this fairly peculiar 2.5D moving image, it becomes less vivid.

More than our perceptual habituation might be at stake. Filmmakers may reduce depth during certain scenes to save money on postrproduction effects. Some gags in A Very Harold and Kumar 3D Christmas (2011) rely on old-school, smack-in-the-eye, paddle-ball depth, but much of the middle of the film doesn’t employ it. By tipping up the glasses and checking how much displacement is in the image, I’ve been surprised to find that remarkably long stretches of 3D films have little or no stereoscopy.

My impression is that Adieu au langage has overcome the problems I mentioned. Granted, many of the shots have sharply-etched images that emphasize the thinness of each plane. But other shots have unusual volume. Several factors may contribute to this. Unusual angles sometimes give foreground elements a greater roundness. This happens in the low-angle tracking shots created by the toy-train rig shown above.

In addition, the relatively low resolution of some of the images avoids creating hard contours.The wavering blown-out softness may enhance volume.

Perhaps as well the slight tremors of the handheld camera mimic one of the factors that yield volume for our normal vision: the very slight movements of our head and body. Such shots shift the aspect enough to suggest the thickness of things.

Godard maintains the sense of depth in a tiny ways. For instance, he discovers that the crackling snow on a TV monitor can yield shimmering depth in the manner of Béla Julesz’s random-dot stereograms. Julesz sought to show that 3D vision wasn’t wedded to perspective cues or the identification of recognizable objects–a conclusion that ought to appeal to the painterly side of Godard.

Production stills indicate that Godard shot the film with parallel lenses. Instead of creating convergence by “toeing in” the lenses during filming, he and his crew played with the images in postproduction to control planes and convergence points. What they did exactly, I don’t know, but the results yield, for me at least, some strong volumes and a continual impression of depth that doesn’t wane.

I wish I could analyze the film’s 3D technique more exactly, but I don’t know enough about the craft of stereoscopic cinema or Godard’s creative process. What this film shows, however, is that 3D is a legitimate creative frontier. In the credits, as usual Godard brusquely lists his equipment, from the high-end Canon 5D Mark II (and Canon is proud to be associated with him) to small rigs like GoPro (in 3D) and Lumix. What is clear is that filming in 3D can be pictorially adventurous with cameras costing a few hundred dollars.

Nature, the ultimate metaphor

Now I’ll concentrate on the first few minutes, at the risk of potential spoilers.

The narrative in Adieu au langage is sketchy even by Godardian standards. Normally he gives us some characters in a defined situation (though it takes a while for us to grasp what that situation is), and a series of more or less developed dramatic scenes that advance a sort of plot. In Passion (1982) a movie director recreates famous paintings on film while a factory owner, his wife, and a worker get embroiled in his project. Detective (1985) carries us through a stay of several people at a luxury hotel. Je vous salue Marie (1985) gives us not one but two plots (Adam and Eve, Joseph and Mary). Éloge de l’amour follows a young writer in his exploration of art dealing and commercial filmmaking.

Adieu au langage doesn’t give us a plot even as skimpy as these. Instead, Godard builds his film out of a bold use of ellipsis and a strict patterning of story incidents. The ellipses are exceptionally cryptic. We must, for instance, eventually infer, on slight cues, that a couple has been together for at least four years, and that the man has stabbed the woman. We learn, with almost no emphasis, that both of the women have ties to Africa–hence the footage of street violence and the recurring question of how to understand that continent.

These very vague plot elements are arranged in a rigorous pattern. This patterning will seem very schematic in my retelling. But it’s not obvious when you see the film. Godard wraps his film’s grid in digressions, sumptuous imagery, and, of course, striking 3D effects.

To get a sense of both the firm architecture and the wayward surface, let’s look at the opening. The first fifteen minutes of Adieu au langage introduce in miniature what the rest of the film will be doing.

A montage of citations before the credits is followed by a fuzzy image of a neon sign. Now we get a sort of overture. Frantic video shots of a crowd under attack and running to a fire are followed by a clip from Only Angels Have Wings and a close-up of the dog identified in the credits as Roxy. That’s followed by a black frame dotted with points of white light. That image will become a little clearer later (stylistic suspense again). Then a title superimposes the numeral one in red with the word, “La Nature.”

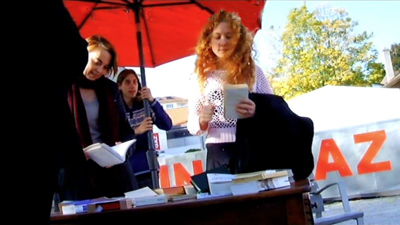

What ensues, after a shot of a ferry approaching a pier, is a fairly disjunctive scene. A booksellers’ table stands across the street from the Usine a Gaz, a cultural center in Nyon, Switzerland. People casually gather there: a redheaded woman (Marie), a young man in a sweater who seems to be the bookseller, a woman on a bicycle (Isabelle), and the older man Davidson (later identified as a professor), here seen from the rear.

The cockeyed low-angle framing might make you think that this is Godard’s Mr. Arkadin, but it suggests footage from a camera or cellphone simply left tipped on some surface behind the table. In that respect it would make manifest the line in Éloge de l’amour: “The image, alone capable of denying nothingness, is also the gaze of nothingness upon us.”

Soon Davidson is sitting in the street commenting on Solzenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago as a “literary investigation.”

A question he asks Isabelle behind him leads to a punning exchange about the thumb (pouce) that we use on our phones, which leads to a question about Tom Thumb (Poucette), a pun on “push” (pousser), and the suggestion that digital icons are like Tom’s trail of pebbles to the giant’s castle. The little skein of associations knots in a remarkable shot of two pairs of hands tickling their mobiles while another person’s hands examine books.

As the men swap phones, a car coasts through the shot in the background.

This scenic fragment, suppressing faces that would help us identify characters, is characteristic of Godard’s approach in the whole film. He isolates gestures and surroundings, letting sound suggest the scenic action; and often the most important narrative action—here, the arrival of the car carrying a gunman—is a minor element in the frame.

So far, we’ve seen one of Godard’s strategies for hiding his story action: ellipsis. Time is skipped over (Davidson behind the table/ in a chair/ then perhaps behind the table), and bits of scenic action are omitted. There is also the opaque framing that impedes character recognition. What about digression? ? We’ve had one example in the Tom Thumb dialogue, but digression can be more overt. Godard can insert shots that have only a tangential narrative connection to the action.

The Godardian digression usually develops in a spreading web of associations that takes us on a detour. Here, one trigger seems to be the mention of Tom Thumb’s Ogre; another is the video display on the phones. These bits lead to a montage about Hitler, who, a woman’s voice reflects, left behind the belief that the state should handle everything. In a polyphony with the woman’s voice reflecting on Hitler, we get Davidson reflecting on how Jacques Ellul foresaw a good deal of the contemporary world. The associational links spread further, to images of the French revolution, crowds hailing Hitler, crowds at the Tour de France, and finally flowers and a voice reiterating a question at the scene’s start: How to produce a concept of Africa?

Now we’re back to the street, with the car pulling up. A chair that may have been Davidson’s is now empty. A man in a suit, the husband, emerges and lights a cigarette, looking off left. A woman, Josette, is in close-up—evidently the target of his look.

Since a black-and-white shot of Josette, head bent, was inserted in the Hitler montage, it’s possible that hers was the voice reciting the argument about the enduring trust in state authority. Perhaps she is reading? In any case, no sooner has a drama of sorts started than we get another digression. Marie reads aloud to us from a book held by the sweater boy. Again, the subject is state power and its inability to acknowledge its violence.

Domestic, not state-sponsored, violence is next on the agenda. A long shot shows the husband stalking up to Josette and berating her in German. The Usine sign is a big help in anchoring the action in the space we’ve seen, and Isabelle’s bike is visible on screen right.

Josette hangs stiffly on his arm, passively resisting and saying, “I don’t care.” He rushes out left. Gunshots are heard, and she jerks in spasmodic response. People rush through the frame. (We’ll never learn exactly what happened offscreen, though later there’s a hint that someone was shot.)

After the car has turned around and left in the way it came, Josette walks stiffly out of the frame. The man in the background who was startled by the husband’s abuse walks to the empty chair and pauses for a time to stare at it.

Cut to leaves floating on water, with hands washing and a man’s voice off saying: “I am at your command.”

So far, so Godardian. The narrative gist is that a woman has fled her husband, refused to return to him, and been approached by a different man who offers to join her. But the flow of images and sounds has made that gist very obscure, obliging us to absorb some fairly ravishing images and to listen to words, noises, and music as they form jagged, interruptive patterns.

And now something very unusual happens. Godard re-plays the events of “1-Nature” in a different location and time of year, using some new characters and some old ones.

A new section, “2” supered on “Metaphor,” appears. Its opening images run parallel to the overture that led up to “1.” After a shot of a swimmer (echoing the previous image of water), we get newsreel footage of combat and fire, and another film extract, this one from Les Enfants Terribles. A shot of Roxy along a river bank is followed by one of a hand opening and closing as a woman’s voice speaks of the “return” of language and a title repeats her insistence that she has made an image.

As at the start of “1,” the ferry comes toward the pier. And now we’re back with Davidson, now sitting along the edge of the water, again reading. His position and the tipped angle suggest a mirror-image of the earlier shot of him near the book table.

A link to the previous scene is provided when Marie and the sweater boy come to Davidson and say they’re going to America. The boy will study philosophy (obligatory quote from Being and Nothingness follows). Their conversation is interrupted by the arrival of the husband again, who shouts and fires his pistol. The shot announcing him is another skewed mirroring: his earlier entrance is inverted–again, as if a mobile phone’s camera had fallen.

The young couple flee and a woman, Ivitch, steps in to talk with Davidson. She shouts at the husband in German, “There is no why here!” ( a line that gets explained later in the film) and tells Davidson to ignore him. This moment offers a variant of the close shot of Josette when the husband had approached.

Ivitch asks Davidson, who evidently has been her professor during the previous term, questions about fighting unemployment by killing workers and about the difference between an idea and a metaphor.

In a new angle, Davidson meditates about images. As if to confirm the professor’s hunch that images murder the present, the husband lunges into the frame and yanks Ivitch out. We now get a shot in which the two cameras diverge: the left eye stays on Davidson, the right one pans over to Ivitch and the husband overlooking the lake. This offers a dense composition akin to that of the book-table shot, with figures piled on one another. The superimposition below is somewhat faithful to what we see, but it can’t convey your temptation to close one eye, then the other, in creating your own shot/reverse-shot editing.

The husband paces around Ivitch, points the pistol, and hollers in German that she’s a dirty whore. She replies as Josette had: “I don’t care.” She walks back to Davidson on the bench, and shortly the husband strides back to the car waiting in the background. Davidson returns to Ivitch’s question about metaphor and then points out two kids playing with dice. These exemplify “the metaphor of reality.” Cut to the kids rolling three dice.

The image echoes Godard’s segment of 3 x 3D, where he puns on “D” as dés, or dice. The kiddies’ shot literalizes the metaphor: trois dés, 3D.

Finally we see Ivitch behind a grille, looking up, then down as we hear the ferry’s horn off. A man’s hand comes in from the left, voice off: “I’m at your command.”

This action repeats the end of the “1” section, but differently: There we saw Gédéon when he inspected Josette’s chair, and heard him say the same words over the leafy water shot. Here both the words and the face of the speaker, Marcus, are offscreen.

Again a woman is threatened by her violent husband and a man emerges to replace him. Again that action is occulted by verbal digressions, dislocated framings, and major characters–here, Marcus–not introduced in a normal fashion. Once more the separate pieces of the scene, straining to cohere, are pulled apart just enough to register as individual instants of beauty, shock, puns, metaphors, or just peculiarity.

Godard’s prospectus for Adieu au langage indicated: “A second film begins. The same as the first.” This describes, laconically, what we’ve seen in the first fifteen minutes. That parallel structure is laid out again with astonishing, yet mostly hidden, rigor in the film as a whole.

Two plus two

Maximal spoilers here.

Over the last thirty years or so, we’ve had plenty of films that replay sections of their stories. Sometimes that dynamic is motivated as time travel, as in Source Code or Edge of Tomorrow—“multiple draft” narratives that let characters, as in Groundhog Day, revisit situations until they master them. Sometimes the repetition has been motivated through varying point of view, so that we see the same action again, but from a different character’s perspective. Examples would be Go, Lucas Delvaux’s Trilogy, and Ned Benson’s recent Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby. Once in a while we get films that present the events as repeated but significantly and mysteriously different. This is what happens in some Hong Sang-soo films, such as The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, as well as in Lee Kwangkuk’s Romance Joe.

In all, this is a minor but important convention of modern screenplays. The replay plot is common enough for screenwriting guru Linda Aronson to consider it separately in her book The 21st Century Screenplay. Trust Godard to take this emerging norm and fracture it.

The opening I’ve just considered invites us to see the film as split into two storylines. Godard has explored duplex construction before, in Éloge de l’amour (with the second part in color video) and Film Socialisme (with its third “movement” appended to two long sections). Yet Adieu au langage offers something different.

Here we have multiples of two: a prologue bookended by an epilogue, the two opening parts that are mirrors of each other, and then two long sections that are uncannily symmetrical. Those sections continue the stories sketched out in the opening section. Each plotline bears the same title as before, but now presented in different graphics (the number and the words are not superimposed, but presented in separate title cards). What’s remarkable is the precise parallels and echoes set up between the pair of tales.

The couples were cast with resemblances in mind, and this affinity is expanded through rather precise doubling. Nearly every scene in the plotline of Josette and Gédéon has its counterpart in the one featuring Ivitch and Marcus. Two nude scenes, two toilet scenes, two bloody-sink scenes, two mirror scenes, two movie-on-TV scenes. There are parallel sequences of driving in the rain, of a woman fleeing into a forest, of Roxy wandering in the woods, of helicopters crashing, of men dying in fountains. As we saw in the early 1/2 segments, the shots’ framings often echo one another.

Godard has laid bare the device in the second story, when Marcus and Ivitch and Marcus talk in front of a mirror.

Marcus: Look in the mirror, Ivitch. There are both of them.

Ivitch: You mean the four of them.

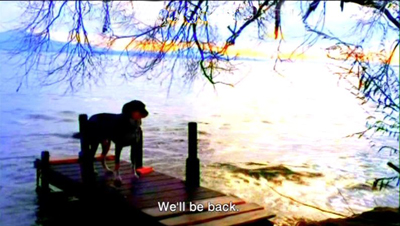

Rather than exact repetitions, we get repetition with variation. One couple takes Roxy in, the other (perhaps) does not. The first couple abandons Roxy on a pier in summer; in the second part, the pier in winter stands empty.

Most remarkably, the parallel scenes of the long section “2/Metaphor” proceed in almost exactly the same order as in “1/Nature”. Evidently Godard shot the bulk of the first story well before he shot the second. It’s as if the first film became the script for the second. In any event, the two long parts mirror one another with unusual precision. This geometrical structure recalls the “grid” organization of Vivre sa vie, but it’s not announced as boldly. Godard refuses to mark the parallel scenes in normal ways–with titles, or musical motifs. The labeling of the sections, 1 and 2 in the intro, 1 and 2 in the longer stretches, are sufficient for this laconic filmmaker.

Just as Godard blurs the shape of individual scenes through digression and opacity, so he hides the tabular structure of the film behind interruptions, landscape shots, and above all the charmed wanderings of Roxy, who more or less takes over the last portion of the second part. In addition, certain images from the second part echo or condense images we’ve seen before. The blood-filled fountain at the end of the second tale echoes both the bloody sink of the first one and the floating-leaf fountain in the prelude, while the clasping hands seem to consummate the gesture begun in the grille shot. These hybrid images can only make the strict double-column scene lineup more difficult to notice.

The fact that the exceptionally exact parallels and orderings of the two parts aren’t remarked upon by critics (I began to sense them a little during my second pass) is a measure of how successfully Godard has camouflaged the film’s anatomy. What shall we call this tactic? Distant counterpoint? Barely discernible rhymes?

Second film, or two films (short and long) times two: We’re free to see the characters as couples running uncannily in synchronization, or as the same couple in two guises, or as two stories in parallel universes. More likely, though, Godard is distressing and disheveling the emerging conventions of replay plotting.

And yet the ending of “the second film, same as the first” isn’t quite the whole story either. Godard has always enjoyed setting up rigid structures and then spoiling them–cutting off the arc of a melody or chopping a shot that could have been breathtaking. So he cracks his elegant 2 + 2 structure by giving us an epilogue and a third couple.

Images recur: crowds on the streets, Roxy snuggling on a sofa, a TV (but this time with two empty chairs). We glimpse a man reading, but mostly we see one hand painting with water colors while another is writing in a journal. Godard’s familiar dichotomy between image and word is here tied to the harmony of an unseen, but clearly heard, man and woman making art in tandem. The male voice seems to be Godard’s; I can’t say whether the female voice belongs to his partner Anne-Marie Miéville, but the woman seems to understand Roxy best. She can even access his thoughts. (“He’s dreaming of the Marquesa Islands.”) Yet this couple has another parallel, shown a little earlier: Percy and Mary Shelley, a poet and a novelist, the latter seen finishing Frankenstein in the forest. This is at least one farewell to language, but it also implies that creativity binds a couple together.

Roxy Miéville, as he’s called in the credits, haunts the film. He checks out streams, train platforms, and tree roots. He is never seen in the same shot with the main characters; his link to them is tenuous. His ramblings suggest freedom, sensory alertness, and a trust in immediate experience that perhaps the people can’t attain. The final images after the credits show Roxy wandering off in the distance and then bounding eagerly back to someone who stands, of course, offscreen.

Godard: The youngest filmmaker at work today.

Many thanks to Robert Sweeney and Richard Lorber of Kino Lorber, a bold company that still believes in art films. It will be releasing Goodbye to Language on 29 October (not September as I erroneously stated in an earlier version of the entry.) Later the film will appear on Blu-Ray 3D. Thanks also to Marc Silberman for help with German translation and to Ben Brewster for advice on stage wings.

For an interesting memoir of the filming of Adieu au langage, see Zoé Bruneau’s En Attendant Godard (Paris, 2014). The photo of the camera train is drawn from p. 93 of her book.

An excellent evocation of the fizz of word and image in Adieu au langage is offered by James Quandt in Artforum (also in the September print edition). Some other stimulating appreciations of the film are Scott Foundas in Variety, Daniel Kasman for MUBI, and Blake Williams in Cinema Scope. A useful description of the film is by Jean-Luc Lacuve on the site of the Ciné-club de Caen.

Too bad the GoPro Fetch, a harnessed camera for dogs, wasn’t available for Roxy to use.

To get a sense of how complex Late Godard is at the level of narrative comprehension, see Kristin’s essay “Godard’s Unknown Country: Sauve qui peut (la vie),” in Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis. I analyze strategies of storytelling in Godard’s 1960s films in Chapter 13 of Narration in the Fiction Film. She wrote about Film Socialisme on the blog here. For a discussion of Godard’s very fussy compositions, try this entry. I consider multiple-draft narratives more generally in the essay

“Film Futures” in Poetics of Cinema.

P.S. 30 Sept: Since Adieu au langage screened at TIFF, VIFF, and elsewhere, a great many critical responses have accumulated. Thanks to the assiduous passion of David Hudson, you can track them all at Fandor. My initial posting should have mentioned two more enlightening discussions of the film: Kent Jones’s Cannes thoughts and the heroic display of Godardiana assembled by Craig Keller at Cinemasparagus.

P.P.S. 15 October: The beat goes on. Ted Fendt’s astonishing list of “Works Cited” in the film, which I added to the body of the above entry, deserves another link here. And the ever-expandig Mubi deserves our thanks for making it available.

P.P.P.S. 29 October: And more, of course. Background on the production process from Fabrice Aragno for Filmmaker; David Ehrlich’s sensitive discussion on The Dissolve; and a story on NPR, with interviews with Héloïse Godet, Vincent Maraval, and (gulp) me. Thanks to Pat Dowell for asking me to participate.

P.P.P.P.S. 2 November: If you haven’t had enough, I posted another entry on the film.

P.P.S. 13 November 2014: Geoffrey O’Brien’s enthusiastic appreciation of the film not only illuminates it but conveys the excitement of seeing it.

VIFF 2013 finale: The Bold and the Beautiful, sometimes together

Gebo and the Shadow (2012).

DB here:

I’m a little late catching up with our viewings at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year (it ended on the 11th), but I did want to signal some of the best things we didn’t squeeze into earlier entries. Kristin and I also want to pay tribute to one of the biggest moving forces behind the event.

Safe but not sorry

Like Father, Like Son (2013).

Among other goals, film festivals aim to provide a safe space for nonconformist filmmaking. Programmers need to find the next new thing—art cinema is as driven by novelty as Hollywood is—and they encourage films that push boundaries. What isn’t so often recognized is that sometimes festivals show filmmakers who were once quite artistically daring backing off a bit from their more radical impulses. Part of this is probably age and maturity; part of it reflects the fact that apart from daring novelties, festivals also showcase works that might cross over to wider audiences. And of course festivals will present recent works by the most distinguished filmmakers, almost regardless of the programmers’ hunches about their quality. Some sectors of the audience want to see the latest Hou or Kiarostami or Assayas.

Koreeda Hirokazu was thirty-three when Mabarosi (1995) won a prize at Venice. It’s an austerely beautiful work, presenting a disquieting family drama in very long, static takes. Once the action shifts to a seacoast village, distant shots render slowly-changing illumination playing over landscapes, while the tension between husband and wife is built out of small gestures. For example, we learn that the forlorn wife is waiting in the bus stop only when a little bit of her comes to light.

Lest this seem just fancy playing around, Koreeda occasionally used his long takes to build suspense. Yumiko’s new husband has been drinking. While he’s out of the room, she opens a drawer to retrieve the bike bell she keeps in memory of her first husband, killed in a traffic accident. The second husband returns unexpectedly, and drunkenly collapses on the table beside her. But when she lifts her hands out of her lap, she inadvertently lets the bell tinkle a little.

The sound rouses him and he asks what she’s holding. She raises her head at last and they begin a quarrel about each one’s motives in marrying the other.

Eventually he will shift woozily to the other side of the table and notice what has been sitting quietly in the frame all along: the still-open drawer on the far right.

In later films, from After Life (1998) to I Wish (2011), Koreeda’s visual design became less reliant on just-noticeable changes within a placid shot. The images have become less demanding, and more extroverted narrative lines carry stronger sentiment. The films remain admirable in their ingenious plotting and mixture of humor and pathos—which is to say, they are committed to that “cinema of quality” that makes movies exportable.

That commitment is firmly in place in Like Father, Like Son. Koreeda, now fifty-one, dares almost nothing stylistically or narratively. Yet every scene leaves a discernible tang of emotion, and his light touch assures that things never lapse into histrionics. If Nobody Knows (2004) and I Wish (2011) are his “children films,” this is, like Still Walking (2008), a movie about being a parent.

The plot has a fairy-tale premise: Babies switched at birth. Our viewpoint is aligned with the well-to-do parents and particularly the ambitious executive Ryota. When he finds that six-year-old Keita isn’t his birth son, he insists on swapping the boy into the household of the happy-go-lucky working-class Saiki family. In exchange, Ryota and his wife take in the boy that Saikis have raised as their own.

As the film proceeds, our view widens to create a welter of comparisons—two ways of being six years old, tough discipline versus easygoing parenting, what rich people take for granted and what poor people can’t, a solicitous mother versus one who can’t spare time for coddling. Koreeda is faultless in measuring the reactions of all involved. Ryota’s wife slips into quiet depression. Saiki is an affable father with a childish streak, but he also looks forward to suing the hospital. Saiki’s wife, a no-nonsense woman with two other kids to care for, is a mixture of toughness and maternal affection. As in a Renoir film, everyone has his reasons, and the drama depends on a process of adjustment stretching across many months. Climaxes become muted, though no less powerful for that.

A smile and a tear: the Shochiku studio formula, enunciated by Kido Shiro back in the 1920s, remains in force here. Simple motifs, such as images stored on a camera’s photo card, hark back to all those affectionate picture-taking scenes in Ozu’s classics. The whole is shot with a conventional polish—coverage through long lenses, straightforward scene dissection—that’s far from the strict, slightly chilly look of Maborosi.

It’s impossible to dislike this warm, meticulously carpentered film. Koreeda has proven himself a master of humanistic filmmaking, and I admire what he’s done (as these entries indicate). Those of us who’ve been following his career for nearly twenty years, however, may feel a little disappointed that he hasn’t tried to stretch his horizons a bit more.

Like Father, Like Son was rewarded with the Jury Prize at this year’s Cannes festival. Steven Spielberg, jury president, has acquired remake rights for DreamWorks.

Action, blunt or besotted

A Touch of Sin (2013).

Jia Zhang-ke’s A Touch of Sin offers a comparable adjustment to broader tastes. It’s far less forbidding than his early features Platform (2000), Unknown Pleasures (2002), and The World (2004). Somewhat like Koreeda, Jia’s earliest fiction films embraced a long-take aesthetic that tended to keep the characters’ situations framed in a broad context. (His documentaries, like the remarkable 2001 In Public, were somewhat different.) Jia proceeded to breach the boundary between documentary and fiction in Still Life (2007), Useless (2007), and 24 City (2008). With A Touch of Sin, Jia takes on a twisting, violent network narrative that is as shocking as Koreeda’s duplex story is ingratiating.

We start with a villager who fumes at the corruption in his town and carries out a vendetta against its rulers. Another story centers on a receptionist who is taken for a prostitute and abused by massage-parlor customers. A third protagonist is an uneducated young man floating among factory jobs who turns his frustration inward. Threading through these is a drifter who shoots muggers from his motorcycle and later takes up purse-snatching.

The sense of inequity and exploitation that ripples through Still Life and 24 City now explodes into rage. Rich men (one played by Jia) puff cigars while strutting through a brothel, businessmen casually exploit their mistresses and buy off politicians, and injustices are settled with fists, knives, pistols and shotguns. “I was motivated by anger,” Jia says. “These are people who feel they have no other option but violence.”

Like Koreeda, Jia has had recourse to some of the casual long-lens coverage we find in many contemporary movies, but certain shots gather weight through his signature long takes–especially shots holding on brooding characters. In all, we get a dread-filled panorama, with bursts of violence staged and filmed with an impact that reminds you how sanitized contemporary action scenes are.

For more, see Manohla Dargis’ rich Times review of the film.

After the painstaking (and pain-giving) dynamics of Drug War (our entry is here), one of Johnnie To Kei-fung’s best recent films, it’s wholly typical that he does something outrageous. His work with Wai Ka-fai at their Milkyway company has always alternated unforgiving crime films of rarefied tenor with sweet and wacko romantic comedies that assure solid returns. But seldom have they combined the two tendencies into something as screechingly peculiar as The Blind Detective.

Initially the investigator, inexplicably named Johnston, seems to be a brother to Bun, the mad detective of To and Wai’s 2007 film. He insists on having the crime reenacted so as to intuit the perp’s identity. But since Johnston is blind, somebody else must tumble down stairs, get whacked on the head, and generally suffer severe pain in the name of the law. Ready to sacrifice herself to Johnston’s mission is officer Ho, a spry and game young woman with a crush on him.

Johnston and Ho are trying to find what happened to a schoolgirl who went missing ten years before. But this account makes the movie seem more linear than it is. Johnston makes his living from reward money, and he’s also dedicated to finding a dancing teacher he fell in love with when he had sight. So the search for Minnie is constantly deflected. Yet the digressions end up, mostly through Johnston’s inexplicable flashes of imagination, carrying them back to their main quest.

This episodic plot, or rather two plots, stretched to 130 minutes (making this the longest Milkyway release, I believe), yields something like a Hong Kong comedy of the 1980s, where slapstick, gore, and non-sequitur scenes are stitched together by the flimsiest of pretexts. The tone careens from farce (not often very funny to Westerners) to grim salaciousness. Johnston’s intuitive leaps are represented by blue-tinted fantasies that show him gliding through a scene at the moment of the murder, or assembling a gaggle of victims to declaim their stories. Characters are ever on the verge of exploding in anger or aggression, and between the big scenes Ho and Johnston dance tangos and gnaw their way through steaks, fish, and other delicacies.

Once more, the congenitally fabulous Andy Lau Tak-wah is accompanied by Sammi Cheng as his love interest, and the two ham it up as gleefully as in Love on a Diet (2001). (They were more subdued in my favorite of the cycle, Needing You…, 1999.) This is, in short, a real Hong Kong popular movie. It brought in US $2.0 million in the territory, and $33 million on the Mainland, about the same as Monsters University. If it keeps Milkyway in business, how can I object?

For a discerning take on The Blind Detective, see Kozo’s review at LoveHKFilm.

JLG in your lap

Kristin and I were keenly looking forward to 3 x 3D, the portmanteau film collecting stereoscopic shorts by Peter Greenaway, Edgar Pêra, and Jean-Luc Godard. Kristin found the Greenaway episode–sort of his version of Russian Ark, taking the camera through the labyrinth of a ducal palace and showing off elaborate digital effects–fairly appealing. But for us the Godard was the main attraction, and he didn’t disappoint.

At one level, The Three Disasters reverts to his characteristic collage of found footage, film stills, scrawled overwriting, and insistent voice-over. (Is it my imagination or does the the 83-year-old filmmaker’s croak sound increasingly like that of Alpha 60?) The montage is sometimes over-explicit, as when Charlie Chaplin is juxtaposed with Hitler. There’s a funny passage of portraits of one-eyed directors (Lang, Ford, Ray), as if to reassert the primacy of classical monocular cinema. At other points, things get obscure, as when Eisenstein’s plea for Jewish causes during World War II is followed by shots from The Lady from Shanghai. But this is the Godard of Histoire(s) du cinema, piling up impressions that beg for acolytes to identify the images and find associations among them.

Frankly, this side of Godard doesn’t grab me as much as his pseudo-, quasi-, more-or-less-narrative features. But in 3D his dispersive poetic musings take on a new vitality. He doesn’t retrofit old movie clips and still photos for 3D. Instead he superimposes them, making one cloudy plane drift over another. He can also, more forcefully, present his signature numerals and intertitles in a new way–by having them pound out of the screen and hang rigidly in front of the image.

There are also some 3D shots made specifically for the film, most consisting of handheld shots that shift around a park, a medical complex, and, of course, a media studio. The very title of Godard’s film, punning on 3D as a technical disaster, as well as a throw of the dice (dés), suggests his ambivalence toward the technology. “The digital,” his voice declares, “will be a dictatorship,” but perhaps it will never abolish chance.

As usual, Godard has fun with simple equipment. He frankly shows us his camera rig, two Canon DSLRs lashed together side by side, one upside down. By shooting them in a mirror and shifting focus, he manages to make each lens pop and recede disconcertingly, as if Escher had gone 3D. This shot alone should inspire DIY filmmakers everywhere. So too should the one-slate credits. Whereas Greenaway’s segment lists scores of names in its credit roll, Godard’s lists only four, alphabetically. I can’t wait for the feature, Farewell to Language. (Trailer here.)

Brian Clark has an informative review of The Three Disasters at twitchfilm.

Looking at the fourth wall

In nineteenth-century Portugal, the elderly Gebo ekes out a living as a company accountant. His wife Doroteia and his daughter-in-law Sofia wait with him for the return of João, a rebellious ne’er-do-well. Gebo feeds Doroteia’s illusions about their son, who has likely become an outlaw. When João returns after eight years away, he throws the family into turmoil and becomes fixated on the cash that his father safeguards for the firm.

After World War II, André Bazin noticed that many filmmakers were starting to take a creative approach to adapting plays. Olivier’s Henry IV, Welles’ Macbeth and Othello, Dreyer’s Day of Wrath, Cocteau’s Les Parents terribles, Melville’s Les Enfants terribles, Hitchcock’s Rope, and Wyler’s Little Foxes and Detective Story, are far from the “photographed theatre” that some critics feared would dominate talking pictures. For decades Manoel de Oliveira has explored avenues of theatrical adaptation that have led us to some daring destinations. Gebo and the Shadow, drawn from a 1923 play by the Portuguese Raúl Brandão, is a powerful recent example, and possibly the best film I saw at VIFF this year.

After the credits show João loitering on the docks, the film confines the action almost wholly to the parlor of Gebo’s family home. Early on we see the street outside through a window, but most of the film concentrates on the characters gathered around the room’s central table. On stage, we can imagine the table at the center and the major characters assembling around it but leaving one side clear, facing the audience–in effect, accepting the convention of the invisible fourth wall that gives us access to the space.

As the still above suggests, it seems initially that Oliveira is playing up this convention, putting us into the stage space and setting the fourth wall behind us. Very soon, though, we’re inserted between the players, so that we see the other side of this lantern-lit playing space.

For the most part, the first stretch of conversations and soliloquys among Gebo, Doroteia, and Sofia are played out in this planimetric, clothesline layout. So is the late-night arrival of the vagrant João, coming to sit opposite his father and laughing wildly. This shot corresponds to the end of the play’s first act.

On the next day, when Gebo and his family receive some friends, the table is sliced in half.

The effect is to redouble the sense of proscenium space, presenting two planimetric arrays that always keep one “behind” us.

Like other chamber-plays-on-film (Dreyer’s Master of the House, Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder), Gebo varies its spatial premises slightly to incorporate other possibilities. In the stretch corresponding to the second act of the play, the angle on the table changes twice, once to present the split table-scene above, and later, to the climactic moment when João joins Sofia and contemplates breaking open the strongbox.

Sometimes we’re shown the window and other walls, usually presented when characters leave one shot and enter another. The constructive editing helps us tie together zones of the room that aren’t ever given in an all-encompassing master shot. And the camera never moves, not even to reframe characters’ gestures.

In previous films, Oliveira has played with the ambiguities of who’s looking where. (See, for instance, Eccentricities of a Blonde-Hair Girl and The Strange Case of Angelica.) After a mysterious prologue involving João, a ravishing image presents Sofia watching at the window, then moving aside to reveal Doroteia behind her (and behind us).