Archive for the 'Directors: Godard' Category

Talks, pictures, and more

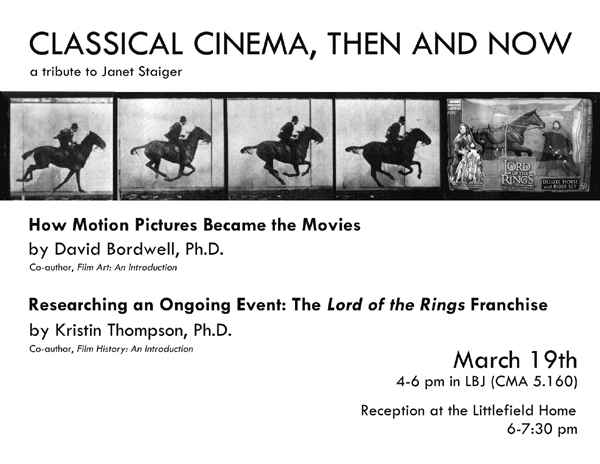

Hard though it is to believe, our dear friend and colleague Janet Staiger is retiring this year from her post as the William P. Hobby Centennial Professor of Communication at the University of Texas. About a year and a half ago, Janet joined us in writing an essay celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of the publication of our collaborative volume, The Classical Hollywood Cinema. Several of our other books have gone out of print, but that one remains available. We’re convinced that its success rests on the fact that the three of us were able to contribute different areas of expertise that meshed seamlessly to cover what turned out to be a far more ambitious topic than we initially envisioned.

We’re delighted to help celebrate Janet’s retirement, since the Department of Radio-Television-Film has invited both of us to lecture at an event to pay tribute to Janet. We’d love to see any of you in the Austin area on March 19. We chose our topics without planning it that way, but they end up book-ending the classical era. David will be speaking on the 1910s, when the early cinema was coalescing into the art of “the movies,” and Kristin deals with the question of how one can deal with a contemporary event that has not yet run its course. (KT)

Short film

The American release of Jafar Panahi’s This Is Not a Film, as well as the first Best Foreign Film Oscar for an Iranian film, A Separation (Asgar Farhadi), have kindled a new interest in Iranian cinema just as some of its most prominent practitioners are dealing with exile, house arrest, and censorship. The International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran has recently posted a short film, Iranian Cinema Under Siege, which lays out the issues succinctly.

Earlier many cinephile sites, including ours, called attention to Panahi’s plight. Anthony Kaufman updates us on his still-undetermined fate. (KT)

Lotsa pictures, lotsa fun (cont’d)

Lynda Barry, Ivan Brunetti, and Chris Ware share a mic.

Our Arts Institute has brought Lynda Barry to campus as an artist in residence this spring, and it’s been a breath of fresh air—actually, make that “blast.” Kristin and I have loved Barry’s work since the 1970s, but only recently did we learn that she was born in Wisconsin and still lives here.

Barry’s UW webpage is a captivating foray into Barryland, and her course, “What It Is: Manually Shifting the Image,” has been open to anyone interested in exploring drawing and/or writing. Convinced that art is a biological phenomenon (“Anybody can make comics,” she says), she encourages people to expand their creative powers without fear of being considered unskillful.

As part of her visit, Professor Lynda has also scheduled events to introduce people to writers and artists. She hosted Ryan Knighton (“badass blind guy”), gave a talk

As part of her visit, Professor Lynda has also scheduled events to introduce people to writers and artists. She hosted Ryan Knighton (“badass blind guy”), gave a talk on with guest Matt Groening, and will interview Dan Chaon (3 May). Her first pair of invitees, on 15 February, was Chris Ware and Ivan Brunetti.

You know I was there.

In fact, I came ninety minutes early to get my front row seat, alongside comics guru Jim Danky. Good thing too; by the time the session started, the big lecture hall was packed.

The first part of the session was a brief panel discussion among Barry, Brunetti, and Ware. As if by design, the table mike didn’t work, so Barry’s lavaliere, threaded up through her pants and blouse, had to be yanked out and stretched across the table when her guests wanted to talk. Result shown above.

Barry called Brunetti a master of balancing the verbal and the visual aspects of comics, and she introduced Ware as “the Wright Brothers” of the graphic novel, with Lint as his Kitty Hawk. Then the two guests, who live in Chicago and get together for Mexican lunch once a week, talked about their influence on one another. Brunetti says that seeing Ware’s work in Raw made him rethink comics altogether. Ware finds in Brunetti “an honest critic.”

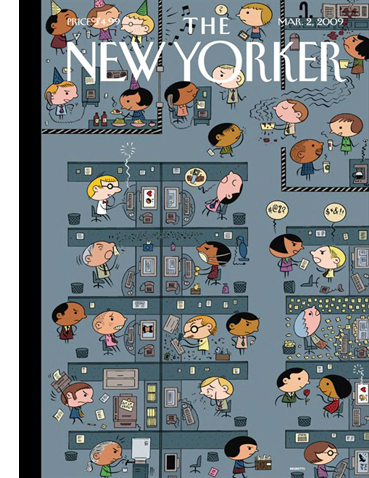

Then Ware left the stage to Brunetti, who took us through his career in PowerPoint. He traced the influence of comics like Nancy and Peanuts on his pretty but edgy big-head style, and he talked about the autobiographical impulse behind much of his work. (“I draw these things to make fun of myself.”) Like many comics artists, he’s fascinated by cinema—be sure to check his “Produced by Val Lewton” page—and some of his New Yorker ensemble panels have the fluid connections we find in network narratives.

In all, it was a lively session that reminded me, among other things, how comic-crazy our town is. Not to mention our state: don’t forget Paul Buhle’s Comics in Wisconsin. That book is filled with work by Crumb, the Sheltons, Spiegelman, etc. It’s as well a tribute to enterprising publisher Denis Kitchen and the now-departed Capital City comics distribution firm. (DB)

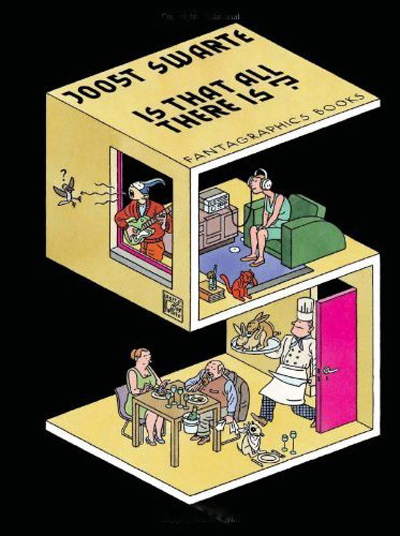

Le mot Joost

I got a little chance to talk to Ware, and we shared our admiration of Joost Swarte, one of the greats of cartooning. Readers of this blog may recall my shameless promotion of Swarte’s work (here and here and here); one of the big events of my fall was getting to meet him in a Brussels gallery. As chance would have it, a couple of days after Barry’s event, I got my copy of the new Swarte collection Is That All There Is?

The book is a fine introduction to work that has for too long been restricted to French and Dutch publications. You get to meet the infinitely knowledgable Dr. Anton Makassar, the lumpish Pierre van Genderen, and the hip but mysteriously ethnic Jopo de Pojo. You also get the first statement of Swarte’s idea of the “Atom Style” of postwar design, connected to the “clear line” school of cartoon art. The book, done up in gorgeous graphics, is graced by an introduction by none other than Chris Ware.

It’s sort of hard to write an introduction for a cartoonist you can’t completely read. . . . I’ve read plenty of his drawings, however. Studied, copied, and plagiarized them, actually; the precise visual democracy of his approach compelled me as a young cartoonist to consider the meaning of clear and readable or messy and expressive, and it was the former which won out.

Now that he mentions it, there is a line running from Ware’s obsessive schematics of narrative space (and time, as Barry says) straight back to the fluent precision of Swarte’s design. Both artists invite your eye to discover things at all level of scale and visibility, while leading you, in Hogarth’s phrase, “on a wanton kind of chase.” (DB)

Derange your day with Feuillade

Two patient, ambitious researchers have contributed to our knowledge of Louis Feuillade’s work, a central concern of DB’s writing and this blog (here and here, in particular). They also teach us intriguing things about cinematic space.

First, Roland-François Lack of University College, London hosts The Cine-Tourist, a site that traces the use of Paris locations in films. His devotion to Paris equals that of the city’s filmmakers, so he provides a thorough canvassing of areas seen in Les Vampires, Fantômas, and Judex. Beyond Feuillade, you can find the places featured in other movies, including L’Enfant de Paris and Le Samourai. Roland-François has even solved the riddle of what movie house Nana visits in Vivre sa vie.

Hector Rodriguez of the City University of Hong Kong has set up a site devoted to Gestus. It’s a program that tracks vectors of movement in a shot and generates abstract versions of them that can be compared with action in other sequences. Gestus can whiz through an entire film–in this case, Judex–and come up with an anatomy of its movement patterns. Hector sees the enterprise as sensitizing us to movement patterns that we don’t normally notice. It also provides a dazzling installation.

Gestus’ ability to generate a matrix of comparable frames recalls Aitor Gametxo’s Sunbeam exploration. But Aitor was interested in how Griffith maps adjacent three-dimensional spaces. Hector’s project focuses on two-dimensional patterning, specifically the deep kinship between different shots when rendered as abstract masses of movement. And while the Sunbeam experiment lays out how spectators mentally construct a locale, Hector is just as interested in friction. “The system invites, confuses, and sometimes frustrates the viewer’s cognitive-perceptual skills.”

That, of course, is part of what cinema is all about. Visit Roland-François’ and Hector’s sites and have a little derangement today. (DB)

If you’re unfamiliar with Chris Ware’s work, a good overview/interview can be found here. Swarte’s stupendously beautiful site is here.

PS 12 March: Because I’ve been immersed in other stuff, I didn’t realize that Matt Groening actually showed up for Barry’s session! And I missed it! Hence the strikeout correction above, initiated by Jim Danky. More on Groening’s visit here.

Echoic patterns of stooping in Judex, as revealed by Gestus.

The Ship of Statements sails on

Kristin here:

I’m glad I held off seeing Jean-Luc Godard’s Film Socialisme (2010) until I could watch it on the big screen. Last September, thanks to the UW Cinematheque I was finally able to do that. I thoroughly enjoyed it, was baffled by parts, thought I understood other parts, and wallowed in the gorgeous imagery that is late Godard. I certainly didn’t understand it well enough to blog about it and point out to the nay-sayers that just because a film is well-nigh impossible to understand doesn’t mean it’s bad. Besides, Andréa Picard has already written an intelligent and spirited defense of the film on CinemaScope where she, among other things, rightly dismisses critics’ claims that Godard is irrelevant and “out of touch with the world.”

A floating metaphor with thirteen decks

I was intrigued last month to learn that the cruise ship the Costa Concordia, which ran aground on January 13 with at least 17 people killed and many others injured, was the ship Godard had used as the setting for the first section of Film Socialisme. A number of websites pointed this out and tried to make some connection, logical or otherwise, between Godard’s choice of his setting and the fact that the ship subsequently crashed. IBTraveler noted:

On Friday, Jan. 13, the Costa Concordia cruise ship crashed into rocks off Italy’s west coast. Just three days earlier on Jan. 10, Jean Luc Goddard’s [sic] hotly debated 2010 “Film Socialisme” was released on DVD. What do the two seemingly unrelated events have in common? The first of the film’s three movements, “Des choses comme ça” (“Such things”), was shot on and prominently featured the doomed ship.

The purely coincidental fact that the DVD had just come out proved mildly newsworthy and undoubtedly garnered Godard a little extra publicity.

The Guardian, in a widely quoted editorial posted two days after the disaster, described Godard’s use of the ship:

Anyone who sat through Film Socialisme may have suspected that the Costa Concordia was heading for trouble. The cruise liner was the setting for the first ‘movement’ of Jean-Luc Godard‘s ambitious, infuriating 2010 picture, serving as a self-conscious metaphor for western capital ploughing through choppy waters. In Godard’s film, the Concordia plays the role of a decadent limbo where the tourists drift listlessly amid the ritzy interiors.

The ship of state is a well-worn metaphor, but critics assumed that Godard had taken it one step further, using the multi-lingual, multi-national group of tourists singled out from among the thousands on the ship as an image of the new Europe and its growing problems. The first movement of the film ends with the title, “QUO VADIS EUROPA.”

Yet Godard did not choose the Costa Concordia and turn it into his central “self-conscious” metaphor. The ship’s makers had created it as a giant floating metaphor well before Godard shot aboard it. The Carnival Corporation ordered it in 2004 and received it in 2006. The ship and its five sister ships are operated by the Costa Crociere company in Italy, which is owned by the Carnival Corporation, also the parent company of Carnival Cruise Lines. According to the owners, the “Concordia” fleet’s name “expresses the wish for continuing harmony, unity and peace between European nations.”

Presumably as a way of expressing that wish, the Costa Concordia, the first of the ships in the fleet to be built, was designed with thirteen decks, each named for a European nation (using the Italian version of each name, since that is where the vessel is registered): Deck 1, Olanda; Deck 2, Svezia; Deck 3, Belgio; Deck 4, Grecia; Deck 5, Italia; Deck 6, Gran Bretagna; Deck 6, Irlanda; Deck 8, Portogallo; Deck 9, Francia; Deck 10, Germania; Deck 11, Spagna; Deck 12, Austria; and Deck 13 (sometimes referred to as 14), Polonia.

An ordinary director, stumbling upon such a perfect ready-made setting encapsulating one main theme of the film, would use these country names. There must be a directory somewhere, or name plates inside and outside the elevators. Yet despite all Godard’s stairway and elevator shots, he never includes a sign that would reveal these names to us. I learned about them not from the film but from the helpful Wikipedia entry on the ship. The only time in the film where I spotted a sign related to the country names was the “Salone Londra” in the background of one shot, presumably on Deck 6. The ship owners might have been heavy-handed, but Godard is not. Even the most unsympathetic critics were able to spot this central metaphor without his having to nudge them.

A floating Tower of Babel

Some commentators implied that in making his film about tourist behavior abroad the ship, Godard had somehow foretold that the Costa Concordia was doomed. The Guardian passage quoted above says a viewing of the film would tell one that the ship “was heading for trouble.” Such a statement spices up a journalistic comment, but I’m sure Godard never dreamed that the Costa Concordia would end up where it has. Certainly many, many other cruise ships are continuing to operate around the world, many of them with the same sorts of multiple restaurants, swimming pools, casinos, bars, and exercise classes that we see in Film Socialisme, and they don’t run aground and cause fatalities. The proportion of people who drive cars and are killed or injured is vastly higher than those who take cruises (or airplanes) and suffer the same fate. When a younger Godard critiqued European society in Weekend (1967), he chose a vast car crash to symbolize it.

All this in itself would not be reason to blog about the link between Godard’s film and the ship’s disaster. Yet recently Newsweek ran an intriguing editorial (also online on the magazine’s sister publication, The Daily Beast) about some possible underlying causes for the disaster, causes related to multiple languages and incomprehensible safety lectures. According to author Eve Conant:

Former crew of numerous other lines say workers were often too exhausted to pay attention during safety-training sessions, and many didn’t speak enough English to even understand what was being said. Reshma Harilal says that during her eight years as a stateroom attendant with Carnival Cruise Lines, parent company of the ill-fated Concordia, boat-safety drills varied in regularity, and she never once had a native English speaker conduct training. “We all got safety training, but even I had difficulty understanding the English of the officers who trained us, who were always Italian with strong accents.” Carnival referred questions to the Cruise Lines International Association, which responded that “training must be conducted in a language that will be understood by the particular crew members.”

[…]

Those who’ve spent their lives in the industry say some answers are floating right on the surface. One is crew-to-passenger ratios, which have widened over the past few decades from an average of one crew member for every two passengers to one for every three, according to the International Transport Workers’ Federation. Crew members work 12-to-14-hour days, seven days a week, for months at a stretch, with minimal time off. “Half the ship is working in a state of fatigue,” says James Walker, a former cruise-industry lawyer who now represents aggrieved crew. “All types of safety studies have shown if you’re really exhausted you can be impaired to the point of intoxication.” The mostly Asian crew of the Costa Concordia had been on an eight-month shift when the ship capsized after running ashore off the Tuscan island of Giglio. Accommodations were like the Titanic’s steerage section. Only managers had shared cabins, and the others slept in dormitory bunks.

This description recalled something that struck me upon seeing Film Socialisme for the first time. It was obvious that Godard was depicting the decadence, wastefulness, and conformism of the people well off enough to take such cruises. But if the film is a microcosm of the European Union, it presents that society as having seen the development a social divide between the prosperous Europeans and a new working class who have come from outside the continent, primarily from Africa, southeast Asia, and the Pacific Rim. They face not only the traditional problems of the working class but also racism and language barriers.

Godard doesn’t make this point overtly. There are relatively few shots of the ship’s crew members. The five frames below are from the only images that focus on crew members, but it’s notable that none is a sailor. Most are waiters; one is a maid. They are the ones most likely to come in direct contact with the passengers and have to obey orders from them. We don’t see anyone order them about in a peremptory fashion or scold them. Usually they are just going about their business, and almost none of them ever speaks. There’s a cook who I suspect is the man invariably present at cruise and hotel buffets making omelets fresh to order. There’s a maid dusting a room, and the inevitable waiters in the bars. The last one, with the yellow vest, is the one who speaks, saying something as she presents the bill.

These shots are so understated and appear so seldom that it is easy to overlook them. Still, their presence can’t be arbitrary. I may have noticed this motif because, even though I’ve never traveled on a huge ship like the Costa Concordia, I’ve been on enough much smaller Nile cruise ships and in enough hotels in Egypt to have seen how some European and American tourists treat the bartenders, waiters, and maids. These servant figures have, I think, an important link to the baffling use of language and the “Navajo” subtitles.

These subtitles baffled a lot of critics. Samuel Bréan has written a fascinating essay about them (and is at work on a book on translation and subtitling in Godard’s films) on senses of cinema. He points out that characters at various points speak Latin, Russian, German, Italian, Spanish, Hebrew, Arabic, Bambara, English, and Greek. In a seemingly perverse, arbitrary gesture, Godard chose not to subtitle these stretches of dialogue in any way that could render them intelligible to someone who doesn’t understand the respective languages of the characters. Rather, he included what he termed “Navajo” subtitles, small series of words that don’t add up to even the barest summary of what the characters are saying. At times they seem almost random. The film was distributed in France without these subtitles, though the French DVD lists “Navajo” in the little box concerning subtitles on the back of the box. The default setting is for them to play, though the viewer has the option to switch them off.

Some critics have assumed that the term “Navajo” refers to real American Indians and thus is in some way offensive. But as Bréan points out, a newspaper story published shortly before the film was shown at Cannes declared that the subtitles would be “as in old Westerns where the Native Americans spoke in choppy phrases.” Not real Navajo, but Hollywood’s clichéd version.

Bréan finds patterns in the subtitles: they are all written as one line, mostly with two or three words, but occasionally with as few as one and as many as five. The words have wide spaces between them, with no punctuation. The verbs are seldom conjugated; there are few pronouns or articles; and separate words are often mashed together, as with “civilwar.”

As Bréan points out, some critics found the subtitles poetic or experimental. He thinks “that if Godard took the principle of reduction inherent to subtitling to an extreme (and added other peculiarities of his own), it is, among other things, to show how relative it is to try and assess a film without acknowledging the inevitable changes in perception caused by subtitling.”

True, no doubt, and yet there is something more going on. Some of the brief strings of words are actual translations of some of the words spoken by the characters. Others are mistakes. In the opening, when the young man with the camera says “une chose,” the subtitle renders it as “nochoice,” as if some invisible non-French-speaker has heard the phrase as something like “unchoice.”

During the introduction of one of the significant characters, Mr. Goldberg, the subtitles render his name as if it were a phrase:

Even when the words are accurate, they tell so little that they actually become a distraction in the struggle to interpret what little one can from the characters’ dialogue.

Given Godard’s concern with the situation in the Arab world, and in particular the injustices done to Palestine, it is telling that the one character whose dialogue is not given any subtitling is a woman speaking Arabic.

Overall my impression of the subtitles on first seeing the film was that they place the spectator in somewhat the same position as someone who is listening to a language he or she does not really understand. When I hear someone speaking Italian or German, I can pick out individual words (no doubt being mistaken about some of them), but they don’t add up to an understanding of what is said. Whether or not we make the connection, we are in somewhat the same situation as those waiters and maids, though for them their jobs may depend upon figuring out what all these tourists speaking their various languages want from them. Europe is full of such people. We more privileged, educated people can have little sense of how they cope, but for me, Godard has found a way to sort of put us in their positions for a little while.

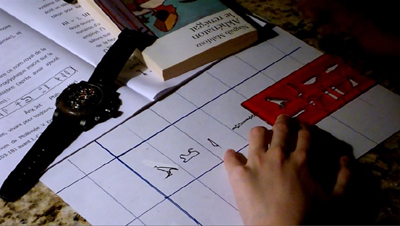

Apart from making this serious point, the focus on language also occasionally creates humor. One character lies on her bed watching a well-known YouTube video of two cats “conversing” in what sounds remarkably like human speech. The woman, however, starts meowing and declares, correctly, that the ancient Egyptian word for cat was Meow (or Miu, as the conventional transliteration of the hieroglyphs has it). She is probably the same person seen earlier writing her name, Alissa, in hieroglyphs, with an elementary introduction to hieroglyphs and a copy of Nagib Mafouz’s novel about the pharaoh Akhenaten. She is the only character presented as having enough interest in the countries where the ship will dock to study them in advance, if only superficially.

A world unto itself

Not that Alissa will get much chance to use her knowledge while ashore in Egypt. Godard does not show the brief excursions that the passengers will be taken on at the various ports of call. There is one single shot of them out on deck looking at a nearby city.

It would be doubly ironic if this city were on the Isola del Giglio, where the Costa Concordia met its fate, but that doesn’t seem to be the case. I don’t know what city this is, but it has managed to draw at least some of the passengers out onto the deck. Otherwise most of them don’t even venture outside to contemplate the sea. Most of the deck shots show immense stretches, empty apart from a few people, including a young man with a camera, and a contemplative young woman (seen in a knit cap in the “nochoice” frame above) who seems to be the closest thing we get to a point-of-view figure.

What Godard doesn’t show is that the occasional excursions are likely to be superficial. I remember on one occasion I was on a tour of Egypt. The group I was with, most of whom knew quite a bit about ancient Egypt, was spending most of the day on the Giza Plateau, hiking around the Great Pyramids and visiting the Sphinx but also viewing some of the quarries, subsidiary pyramids, ruined temples, and private tombs that cover the plateau around and between the pyramids. We went back to our bus to have lunch. While we were there, we were treated to the spectacle of 24 identical buses arriving and disgorging their full loads of tourists. Clearly they had come from one of these giant cruise ships. (Tours within Egypt seldom require more than one bus.) They had a look at the pyramids from the parking lot and walked down the hill to see the Sphinx. Reloading the buses took a while, and the entire group departed twenty minutes after they arrived. They might have gone to the Egyptian Museum, though the ticket and security lines might take too long for such a large group. Maybe they just had lunch instead and headed back for Alexandria, where their ship was docked.

The drive from Alexandria to Giza is about three hours each way, during which passengers are treated to a desert landscape empty apart from billboards for Pepsi, Coke, KFC, and other familiar products, as shown in this photo I took in 1995. (For a charming, illustrated account written by an upbeat couple who took what seems like an pretty good version of such a whirlwind tour in Egypt, see here and here. They did get a quick look-in at the museum and had lunch at the wonderful Mena House at the foot of the Giza Plateau.)

I assume the same sort of thing happens at each stop along the cruise-ship’s itinerary.

Godard’s point, presumably, is that for the vast majority of the people on the trip, the entertainment and sustenance offered within the Costa Concordia itself, along with the duty-free shops ashore (we see some of the passengers visit a gallery displaying remarkably bland art unrelated to the local culture) are the main attractions. A chance to get a photograph taken in front of the Sphinx or the Parthenon is a little bonus.

If you don’t understand Godard

Then there is the visual side of things. How could anyone dismiss a film that has images like these?

Ledoux’s legacy

DB here:

Every summer Brussels hosts one of the world’s most unusual film festivals. By global standards it’s a small event: it showcases only twenty or so titles, each screened twice. The films are on the whole unknown. The prizes are minuscule by the million-plus benchmarks set by Dubai and Abu Dhabi. The venue stands behind an inconspicuous doorway. Yet for me it’s an unmissable event, a crucial influence on my thinking about film and my search for cinematic satisfaction.

Jacques the gentle

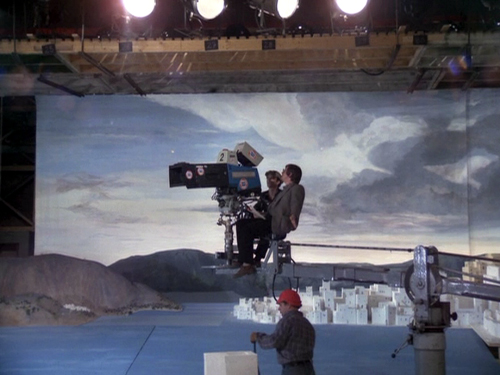

Young Murderer (Seishun no satsujin sha, 1976).

Between 1948 and his death in 1988, Jacques Ledoux was the curator of the Royal Film Archive of Belgium. He made it into one of the cinema’s legendary places, at once Mecca and Aladdin’s cave. On remarkably small budgets, he assembled broad and deep collections. He bought many titles for distribution to local cinemas and schools. He created a public screening program that for decades has shown five different films (two of them silents), every day of the year. The year Ledoux died he received an Erasmus Prize for his services to European culture.

His early life could have come out of an East European movie. Born in Poland in 1921, he fled to Belgium to escape the German onslaught. He hid in several places, including a monastery. There the abbot gave him work publishing Benedictine books. In the abbey’s screening room Ledoux discovered a copy of Nanook of the North. He offered it to the just-started Belgian Cinémathèque, and its supervisor, the filmmaker Henri Storck, offered Ledoux a job. Finding film archivery more appealing than studying science and medicine, he stayed with the Cinémathèque. Interestingly, “Jacques Ledoux” was a pseudonym; one translation is Jacques the Gentle.

Not always gentle Jacques in his scraps with other archivists and local politicians, Ledoux pledged himself to filmmakers, audiences, and—a rarity at the time—overseas film scholars. New Wave directors and Parisian critics made railway pilgrimages to Brussels to see films unavailable in France. When Kristin and I started doing research in the archive in the 1979, Ledoux welcomed us and guided us to treasures we hadn’t known existed.

Unlike the very public Henri Langlois, Ledoux worked best behind the scenes. Probably most cinephiles today know him only from his brief appearance as one of the sinister experimentalists in La Jetée (1961). He resisted being photographed, and he refused to wear a necktie. Unsurprisingly, he admired directors who strayed from the beaten path. He created the first festival of experimental cinema at Knokke-le-Zoute, in 1949.

Unlike the very public Henri Langlois, Ledoux worked best behind the scenes. Probably most cinephiles today know him only from his brief appearance as one of the sinister experimentalists in La Jetée (1961). He resisted being photographed, and he refused to wear a necktie. Unsurprisingly, he admired directors who strayed from the beaten path. He created the first festival of experimental cinema at Knokke-le-Zoute, in 1949.

His desire to widen everyone’s knowledge of cinema found another outlet when he created the Prix l’Age d’or/ Prijs l’Age d’or in 1958. It was aimed to reward, as Ledoux put it, “a film that, by questioning taken-for-granted values, recalls the revolutionary and poetic film of Luis Buñuel, L’Age d’or.” Ledoux wanted to encourage a cinema that was subversive in both content and form.

The first prizes were given within the framework of the Knokke event: in 1958, to Kenneth Anger; in 1963, to Claes Oldenberg; in 1967 to Martin Scorsese (for The Big Shave). In 1973, the prize assumed something close to its current form. Several films were screened for the public, and the award, now in the form of cash, was decided by a jury system. The first winners were W. R.: Mysteries of the Organism (in 1973); Borowczyk’s Immoral Tales (1974); Raul Ruiz’s Expropriation (1975); Angelopoulos’ Traveling Players (1976); Hasegawa Kazuhiko’s Young Murderer (1977); and Antoni Padros’ Shirley Temple Story (1978).

The winners emerged from a vast and powerful field of competition. In 1973, the first formal year of L’Age d’or, there were sixty-nine films screened, including Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Oshima’s Ceremonies, Paul Morrissey’s Heat, Tout va bien, and works by Rosa von Praunheim, Wim Wenders, and Miklós Jancsó. There was even The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, but Buñuel didn’t win a prize named after his own film! The number of titles dropped a little as the years passed, but it’s good to know that in 1978 Assault on Precinct 13, Eraserhead, Perceval le Gallois, and films by Ruiz, Littín, and Schroeter were in the competition.

Ciné-Discoveries

City of Sadness (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1989); screened at Cinedécouvertes 1990.

Things changed a bit after 1979. The L’Age d’or criteria were modified to identify “films that by their originality, the singularity of their viewpoint, and their style [ecriture] deliberately break from cinematic conformity.” For whatever reasons, hard-edged subversive cinema was harder to come by. In the meantime, the Prix was absorbed into a broader festival Ledoux launched in 1979, Cinédécouvertes.

Cinédécouvertes became a “festival of festivals.” It culled its selection from films that had been screened at Rotterdam, Berlin, Cannes, Venice, and other events. What set Cinédécouvertes apart was its determination to expand film culture. All the films on the program had no Belgian distribution. Each cash award (today, two of 10,000 euros each) would go not to the filmmaker but to a distributor willing to pick up the film. This is a very tangible way to help films of quality find a local audience.

Over the last ten years, Cinédécouvertes has awarded prizes to Audition, Chunhyang, Werckmeister Harmonies, Oasis, Tropical Malady, Day Night Day Night, Mogari no Mori, Afterschool, and Police, Adjective. The L’Age d’or prize has been given to Aoyama’s Eureka, Reygadas’ Japón, Encina’s Hamaca Paraguay, Balabanov’s Cargo 200, and several others. Not every film has been picked up for local distribution, but the impulse to elevate films that go beyond the obvious festival favorites has continued. Ledoux’s successor as curator, Gabrielle Claes, has maintained the legacy of L’Age d’or and Cinédécouvertes. The July festival flourishes in the Cinematek’s newly rebuilt complex and in its other venue, the lovely postwar-moderne building in the Flagey neighborhood.

The annual Brussels event helped me find my way through modern cinema. There I saw my first Kiarostami (Where is My Friend’s Home?), my first Tarr (Perdition), my first Hou (Summer at Grandpa’s), my first Oliveira (No; or, the Vainglory of the Commander), my first Sokurov (The Second Circle), my first Kore-eda (Maborosi), my first Panahi (The Mirror), my first Jia (Xiao Wu). The Cinematek’s talent-spotters were quick to find many of the most important filmmakers of the 1980s and 1990s, and I’ll be forever grateful for their acumen. After I saw these films and many others here, my ideas about cinema got more cogent and complicated. My life got better, too.

Now most of these filmmakers find commercial distribution in Belgium, so Gabrielle’s scouts must scan new horizons. This year as usual Cinédécouvertes boasted some familiar names like Iosseliani, Wiseman, Guzman, and the eternal troublemaker Godard. But there are also filmmakers from Costa Rica, Sri Lanka, Ireland, Peru, Colombia, and Ukraine. The landscape of film is vast, as Ledoux always reminded us, and a small festival can nonetheless open windows wide.

Mind games, or just games

Elbowroom.

Psychology is at the center of festival cinema. Deprived of car chases and exploding buildings, arthouse filmmakers try to track elusive feelings and confused states of mind. That this can be dramatically engaging in quite a traditional way, as was shown by one of the Cinédécouvertes winners, How I Ended This Summer.

Director Aleksei Popogrebsky puts two men on a desolately beautiful island in the Arctic. They’re initially characterized by the way they execute the routines of measuring weather conditions. Sergei, the stolid older one, is soaked in the ambience of the place, enjoying fishing and boating while insisting on exactness in the log. Pasha is a summer intern, a little careless because he’s exhilarated by the atmosphere: he’s introduced first taking a Geiger-counter reading but then hopping and racing along a cliff edge to the beat of his iPod.

Soon, though, Pasha must give Sergei a piece of bad news that comes in over the radio. Out of awkwardness, fear, refusal of responsibility, and other impulses, he avoids telling his mentor. The consequences are unhappy for each. The film takes on the suspense of a thriller, with conflicts surfacing in a cat-and-mouse game at the climax. Yet before that, more subtly, we have watched several tense long takes of Pasha’s face as he tries to cover up his failures. Not surprisingly, How I Ended This Summer won one of the two Cinédécouvertes prizes. It is an engrossing case for character-driven, locale-sensitive cinema.

Elbowroom tackles psychology from a more opaque and disturbing angle. With no exposition or backstory, we’re plunged into an institution for the handicapped. During the first ten minutes, without dialogue, a handheld camera lurks over the shoulder of a young woman who tries with twisted fingers to apply lipstick. Soon she is preparing to have sex with another inmate, and after their liaison she is whacking her feeble roommates, who sob under her blows. Eventually we’ll recognize this introduction as a summary of her days: fighting with others, being coaxed or berated by staff, meeting her lover, and taking up cleaning tasks. Only far into the film will we learn about how she got here and what her fate will be.

Soohee, stricken with cerebral palsy, is played by a young woman with a milder disease. Very often the camera doesn’t let us see her face, fastening instead on a ¾ view from behind. This seems to me partly a matter of tact, but its ultimate effect is to force us to infer Soohee’s state of mind from her behavior. The visual narration remains resolutely outside the character. Psychology gets reduced to gestures— spasmodic smearing of lipstick, the clasping of a necklace, the seizure of a baby doll (with which she’s bribed). Only at the end does a long held close-up of Soohee’s twitching, smiling face give us fairly direct access to her feelings. Despite the smile—which can be read as a sort of perverse victory for her—Soohee isn’t the noble victim; we’ve seen her petty and selfish side already.

This trip into a world most of us haven’t seen before is presented without conventional pieties, and it’s unsettling. Elbowroom, Ham Kyoung-Rock’s first feature, offers the sort of challenge to aesthetic and moral conventions that the L’Age d’or Prize was designed to encourage. The film won it.

Characters’ psychological developments can also be brought out by parallel construction. A willful little girl and a scientist cross paths in Paz Fábrega’s Cold Water of the Sea. Karina is on a beach holiday with her family and insists on wandering off at intervals. Marianne is a medical researcher, here for a vacation with her boyfriend. When Marianne finds Karina asleep along the road one night, the girl claims that her parents are dead and that her uncle abuses her. But next morning she’s gone, and fears for her safety are only the first of several anxieties that haunt Marianne’s holiday. While Karina incessantly bedevils her mother and makes mischief with other kids, Marianne descends into ennui as she watches her boyfriend devote his time to selling a piece of family property.

Characters’ psychological developments can also be brought out by parallel construction. A willful little girl and a scientist cross paths in Paz Fábrega’s Cold Water of the Sea. Karina is on a beach holiday with her family and insists on wandering off at intervals. Marianne is a medical researcher, here for a vacation with her boyfriend. When Marianne finds Karina asleep along the road one night, the girl claims that her parents are dead and that her uncle abuses her. But next morning she’s gone, and fears for her safety are only the first of several anxieties that haunt Marianne’s holiday. While Karina incessantly bedevils her mother and makes mischief with other kids, Marianne descends into ennui as she watches her boyfriend devote his time to selling a piece of family property.

Once more Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy proves to be a template for festival cinema. What is wrong with Marianne goes beyond her diabetes: she feels bored and useless. But while Rossellini adhered primarily to the viewpoints of his dissolving couple, Fabrega opens out the portrayal of upper-class anomie by intercutting episodes from the lives of working-class families. The film has two fully-developed protagonists, with Karina’s verve balancing Marianne’s increasing torper. Splitting his story allows Fabrega to make some social points (the family camps on the beach, the couple stays in a motel with a scummed-over swimming pool) and to suggest secret affinities between the little girl and the professional woman. Cold Water of the Sea seemed to me an honorable effort to let some air into the premises of the standard portrayal of a cosmopolitan couple’s ennui.

Parallels likewise form the core of Otar Iosseliani’s Chantrapas, another of his celebrations of shirkers, layabouts, con artists, and free spirits. The title is Russian slang for a disreputable outsider (derived from the French ne chantera pas, “won’t sing”). Here the outsider is Kolya, a young Georgian director who turns in a movie that can’t pass the censors. He emigrates to Paris, where he finds an aging producer (played by Pierre Etaix) eager to tap his talent. But the new project’s backers try to take over the project in scenes deliberately echoing the ones of Party interference.

Chantrapas lacks the shaggy intricacy of Iosseliani’s “network narratives” like Chasing Butterflies (1992) and Favorites of the Moon (1984), the latter of which I enjoyed analyzing in Poetics of Cinema. When we’re given a single protagonist, as in Monday Morning (2002), Iosseliani’s characteristic refusal of motivation, exposition, and introspection creates a more plodding pace. No mind games here. In earlier films, his favorite shot—panning to follow people walking—creates convergences and near-misses and comic comparisons in the vein of Tati. Here the pans serve as merely functional devices, almost time-fillers, and comedy is largely lacking. Still, Iosseliani avoids the easy traps. A Soviet censor bans Kolya’s film, then congratulates him on making such a good movie. When the Parisian preview audience flees the theatre, we can’t call them philistines. Kolya’s movie, despite its stylistic debt to Iosseliani’s own films, looks awful. In the end, even cinema seems less important than smoking, drinking, eating, and, above all, loafing.

It was a documentary, Nostalgia de la Luz by Patricio Guzmán, that won the second Cinédécouvertes prize. It starts as a memoir of Guzmán’s fascination with astronomy, explaining that the unusually clear skies of Chile have attracted researchers who want to probe the cosmos. Because the light from heavenly bodies takes a long time to reach us, Guzmán casts his observers as archeologists and historians: “The past is the astronomer’s main tool.” This is the pivot to the film’s main subject, the search for the disappeared under the US-installed dictator Pinochet.

The analogies rush over us. The enormity of the universe is paralleled by the immensity of Pinochet’s oppression of his country. Captives in desert concentration camps learned astronomy, but eventually they were forced inside at night; the skies’ hint of freedom threatened the regime. Some of the astronomers are friends or relations of the disappeared and see research as therapeutic, putting their personal sufferings in a much more vast cycle of change. Above all there are the old women who patiently scour the desert for traces of their loved ones. A woman tells of finding her brother’s foot, still encased in sock and shoe. “I spent all morning with my brother’s foot. We were reunited.” Scientists try to know the history of the cosmos, and ordinary people tirelessly challenge their government’s efforts to conceal crimes. Both groups, Guzmán suggests, acquire nobility through their respect for the past.

Taking some chances

More formally daring was Totó. This was the first Peter Schreiner film I’ve seen, and on the basis of this I’d say his high reputation as a documentarist is well-deserved. Without benefit of voice-over explanations, we follow Totó from his day job at the Vienna Concert Hall (is he a guard or usher?) to his hometown in Calabria. The film is an impressionistic flow registering his musings, his train travel, and his conversations with old friends, many of the items juggled out of chronological order.

Schreiner avoids the usual cinéma-vérité approach to shooting. Instead the camera is locked down, the framing is often cropped unexpectedly, and the digital video supplies close-ups that recall Yousuf Karsh in their clinical detail. We see pores, nose hair, follicles at the hairline; the seams of sagging eyelids tremble like paramecia. In addition—though I won’t swear that Schreiner controlled this—the subtitles hop about the frame, sometimes centered, sometimes tucked into a corner of the shot, usually with the purpose of never covering the gigantic mouths of the people speaking. All in all, a documentary that balances its human story with an almost surgical curiosity about the faces of its subjects. The Jean Epstein of Finis Terrae would, I think, admire Totó.

I had to miss some of the offerings, notably Oliveira’s Strange Case of Angelica. (Fingers crossed that it shows up in Vancouver.) Eugène Green’s Portuguese Nun was screened, but I’ve already mentioned it on this site. Other things I saw didn’t arouse my passion or my thinking, so they go unmentioned here. Of the remainders, two stood out above the rest for me.

My Joy (Schastye moe), by Sergei Loznitsa, is a daring piece of work. After a harsh prologue, it spends the first hour or so on Georgy, a trucker whose effort to make a simple delivery takes him into the predatory world of the new Eastern Europe. He meets corrupt cops, a teenage hooker, and most dangerously a trio of ragged men bent on stealing his load. After an anticlimactic confrontation, the film introduces a fresh cast of characters, including a mysterious Dostoevskian seer. The film becomes steadily more despairing, culminating in a shocking burst of violence at a roadside checkpoint.

At moments, My Joy flirts with the idea of network narrative. When Georgy turns away from a traffic snarl, the camera dwells on roadside hookers long enough to make you think that they will now become protagonists. One character does bind the stories together: an old man who fought in World War II and who now helps the seer at a moment of crisis. The sidelong digressions, slightly larger-than-life situations, and the floating time periods suggest a sort of Eastern European magic realism. But the whole is intensely realized, at once fascinating and dreadful. After one viewing, I wanted to see it again.

My favorite, as you might expect, was Godard’s Film Socialisme. There are the usual moments of self-conscious cuteness (the zoom to the cover of Balzac’s Lost Illusions, for instance), but on the whole it’s pretty splendid.

Contrary to what a lot of people claim, I don’t think Godard is an “essayist” in most of his films. (Perhaps in Histoire(s) du cinema, but rarely elsewhere.) He tells stories. Granted, they are elliptical, fragmentary, occulted stories, free of expository background and flagrantly unrealistic in their unfolding. Into these stories he inserts citations, interruptions, digressions: associational form gnaws away at narrative. But stories they remain.

The first part of Film Socialisme takes place on a cruise ship. As it visits various ports on the Mediterannean, some passengers learn that a likely war criminal is on board. Then, like Loznitsa, Godard shifts to a new plot. In the French countryside, a garage-owner’s family is invaded by a TV crew. (As far as I can tell from the untranslated dialogue, the son and daughter are purportedly running for elective office.) Finally, in the last eighteen minutes or so, we get pure associational cinema—not an essay, I think, but something like a collage-poem: a busy montage of clips seeking (or so it seems to me) to ask what sort of European politics is possible after the death of socialism.

Andréa Picard has already written a superb commentary on the film, and it would be useless for me, after only two viewings, to try to go much beyond her account. I’d just say that the first two stories show the same sort of ripe visual imagination we have come to expect from late Godard. The images are oblique and opaque, framed precisely but denying us much in the way of story information. Who are these people? Who’s related to whom? (Who are the women apparently linked with the mysterious Goldberg?) More concretely, who’s talking to whom?

Godard cuts among images of varying degrees of definition in a manner reminiscent of Eloge de l’amour, but here color is paramount. We get saturated blocks of blue sky and blue/ turquoise/ charcoal sea. See the image further above, or this one, which is virtually a perceptual experiment on the ways that color changes with light and texture.

Anybody with eyes in their head should recognize that such shots show what light, shape, and color can accomplish without aid of CGI. They aren’t simply pretty; they’re gorgeous in a unique way. No other filmmaker I know can achieve images like them. We also get entrancing scatters of light in low-rez shots in the ship’s central areas and discotheque.

Just as noteworthy from my front-row seat was Godard’s almost Protestant severity in sound mixing. For the first twenty minutes or so, the sound is segregated on the extreme right and extreme left tracks, leaving nothing for the center channel. We hear music on the left channel and sound effects on the right, or ambient sound on one side and dialogue on the other. The result is a strange displacement: characters centered in the screen have their dialogue issuing from a side channel. Sometimes a sound will drift from one channel to another and back again, but not in a way motivated by character movement (“sound panning”). Having accustomed us to this schizophrenic non-mix, Godard then starts dropping a few bits into the center channel. But for the bulk of the shipboard story, that region is largely unused.

We leave the ship with a title, “Quo Vadis Europa,” and now we’re in Martin’s garage, listening to him being interviewed by an offscreen woman. His voice squarely occupies the central channel, with offscreen traffic sliding around the side channels. The same central zone is assigned to the wife and the kids. Would it be too much to say that the working people have taken control of the soundtrack? In any case, although the side channels are very active, the sound remains centered during a permutational cluster of family scenes (parents and children alone, father with daughter, mother with son, boy with father, daughter with mother).

This section ends with a final confrontation with the nosy reporters. The overall episode can be seen as a revisiting of Numero deux (1975), another uneasy family romance and one of Godard’s first forays into video.

The rapid-fire finale would require the sort of parsing that Histoire(s) du cinema has invited. Through footage swiped from many other filmmakers, Godard revisits the cruise ship’s ports of call, investing each with a symbolic role in the history of the West. Egypt and Greece get considerable emphasis, but so do Palestine and Israel. This history is, naturally, filtered through cinema: not just footage of the Spanish Civil War but clips from fiction films like The Four Days of Naples (1962). After glimpses of Eisenstein’s Odessa Steps massacre, we get shots of today’s kids standing on the steps declaring they have never heard of Battleship Potemkin.

Exasperating and exhilarating, Film Socialisme shows no flagging of its maker’s vision. “He’s a poet who thinks he’s a philosopher,” a friend remarked. Or perhaps he’s a filmmaker who thinks he’s a painter and composer. In any case, Film Socialisme will be remembered long after most films of 2010 have been forgotten. More intransigent than most of his other late features, and unlikely to be distributed theatrically outside France, if there, it shows why we need “little” festivals like Cinédécouvertes now more than ever.

The home page of the Cinematek is here. A complete list of L’Age d’or and Cinédécouvertes winners is here. Last year, between research and preparing for Summer Movie Camp, I had no time to blog about the festival. But you can go to my earlier coverage for 2007 and 2008.

As one who cares about Godard’s aspect ratios, it pains me to use illustrations from online sources, which are notably wider than the version I saw projected in Brussels. When I can get my hands on a proper DVD version, I will replace these images with ones of the right proportions.

Seeing movie seeing: Display monitors in the reception area of the Cinematek.

It takes all kinds

Kristin here—

How many directors are there whose bad reviews just make you more eager to see their new films? I’m not at Cannes and haven’t seen Jean-Luc Godard’s Film socialisme. But I’ve read some negative reviews, mainly those by Roger Ebert and Todd McCarthy. Now I’m really hoping that Film socialisme shows up at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year. (Please, Mr. Franey? I promise to blog about it.)

As you can tell from my writings, I’m no pointy-headed intellectual who won’t watch anything without subtitles. I love much of Godard’s work and have analyzed two films from early in what a lot of people see as his late, obscurantist period (Tout va bien and Sauve qui peut (la vie) in Breaking the Glass Armor). But I also love popular cinema. If I made a top-ten-films list for 1982, both Mad Max II (aka The Road Warrior) and Passion (left and below) would be on it.

Of course, those are old films by most people’s standards. Godard’s films have gotten much more opaque since I wrote those essays. I wouldn’t dare to write about King Lear or Hélas pour moi. That’s partly because I don’t speak French, though a French friend of ours has assured us that that doesn’t help much. Here Godard thwarts the non-French-speaker further by not translating the dialogue. Variety‘s Jordan Mintzer describes the subtitles that appear in the film: “To add fuel to the fire, the English subtitles of “Film Socialism” do not perform their normal duties: Rather than translating the dialogue, they’re works of art in themselves, truncating or abstracting what’s spoken onscreen into the helmer’s infamous word assemblies (for example, “Do you want my opinion?” becomes “Aids Tools,” while a discussion about history and race is transformed into “German Jew Black”).” Mintzer’s review provides a long description of the film; he mentions how baffling it is but doesn’t offer any real value judgments on it. Like other reviews, though, it piques my interest in the film.

Since Godard has increasingly moved into video essays, I’ve not kept as close track of him. But I always look forward to seeing his occasional new features on the big screen. The man has a mysterious knack for making beautiful images out of the mundane. How could a shot of a distant airplane leaving a jet-trail across a blue sky be dramatic? Godard manages it in the first shot of Passion. (I won’t show a frame from that shot, since it depends on the passage of time for its effect.) His soundtracks are dense and playful. Every few years the man cobbles together an incomprehensible plot based on rather tired political ideas and turns out something so visually striking that it might as well be an experimental film. I’m willing to watch and listen hard without assuming that I’m obliged to strain to find a message. McCarthy comments, “More personally, I have become increasingly convinced that this is not a man whose views on anything do I want to take seriously. […]” Did we take his views all that seriously back when he was a Maoist? I didn’t, but La Chinoise is a terrific film.

That’s not my point, though. As Ebert’s and McCarthy’s reviews both mention there are devotees of Godard who will most likely enjoy and defend Film socialisme. Ebert: “I have not the slightest doubt it will all be explained by some of his defenders, or should I say disciples.” McCarthy says that Godard is one of an “ivory tower group whose work regularly turns up at festivals, is received with enthusiasm by the usual suspects and then is promptly ignored by everyone other than an easily identifiable inner circle of European and American acolytes.” (McCarthy’s review is entitled “Band of Insiders.”)

I’m not sure what’s wrong with being devoted to Godard, even to the point of defending films that may be obscure or even maddening. I personally haven’t enjoyed his more recent theatrical releases like Forever Mozart and Éloge pour l’amour as much as his earlier work, but they’re still better than most Hollywood, independent, and foreign art-house films. The man is pushing 80 and not likely to change, so live and let us acolytes live.

Not coming to a theater remotely near you

I’m not here to defend Godard—not yet, anyway. But on May 19, Roger posted an essay calling for more “Real Movies” to be made, essentially narratives based on psychologically intriguing characters in situations with which we can empathize. He doesn’t say so, but I suspect this idea was inspired in part by his reaction to Film socialisme. His examples of real movies are some of the films he’s enjoyed this year at Cannes. I haven’t seen those, either, but I’ve read enough of Roger’s writings and been to Ebertfest often enough to know he loves U. S. indie films like Frozen River and Goodbye Solo. Excellent films with fascinating characters, but they and most of the foreign-language films that get released in the U.S. play mostly at festivals and in art-houses, both of which tend to be confined to cities and college towns. I’m sure that such character-driven films would be more likely than Film socialisme to get booked into art-houses, but they wouldn’t wean Hollywood from its tentpole ways.

Even the films that play festivals and arouse great emotion and admiration in the audiences will seldom break through into the mainstream. There simply aren’t enough of those art-houses.

As with many of Roger’s posts, “A Campaign for Real Movies” has aroused comments from people complaining about the lack of an art-house within driving distance of where they live. Jeremy Chapman remarked:

But Roger, if they did that (“Real Movies”), then I’d return to the cinema. And those in charge of the movie industry have proven again and again that they don’t wish to see me there. They’d rather show regurgitated nonsense to people so desperate for some distraction from their lives that they’ll go even though they know that they’re watching rubbish.

If any of these films you mention play nearby, then I shall see them. But they won’t. Instead I’ll have the option of Avatar II or some remake of a movie that was quite good enough (or not) the first time it was made. I love the movies, but I’m so over the movie industry (at least in the US).

Talking to regulars at Ebertfest, one hears time and again that some of them journey across several states to have a quick, intense immersion in films that haven’t played near their homes. Similarly, many who post comments on Roger’s essays refer to having been limited to seeing indie and foreign films on DVDs or downloads from Netflix.

I completely sympathize with that problem. Even with Sundance’s six-screen multiplex and the University of Wisconsin’s Cinematheque series and Wisconsin Film Festival, most of the movies David and I see at events like Vancouver or Hong Kong don’t play here. Sundance has to book pop films on some of its screens to allow them to bring art films to the others. Right now Iron Man 2 and Sex in the City 2 are playing there, alongside The Secret in Their Eyes and Letters to Juliet. If that’s what it takes to keep the place going, then so be it.

I completely sympathize with that problem. Even with Sundance’s six-screen multiplex and the University of Wisconsin’s Cinematheque series and Wisconsin Film Festival, most of the movies David and I see at events like Vancouver or Hong Kong don’t play here. Sundance has to book pop films on some of its screens to allow them to bring art films to the others. Right now Iron Man 2 and Sex in the City 2 are playing there, alongside The Secret in Their Eyes and Letters to Juliet. If that’s what it takes to keep the place going, then so be it.

However much people decry the crassness of Hollywood—and there’s plenty of it to go around—or denounce audiences who only go to the latest CGI spectacle, the simple fact is that the market rules. Indeed, if there were a truly free market, we probably would see far fewer indie and foreign-language films. Film festivals are supported largely by sponsors, and the films they show are often wholly or partially subsidized by national governments. The festival circuit has long since become the primary market for a range of films that otherwise never reach audiences.

That may sound terrible to some, but consider the other arts. Some presses only publish books they hope will be best-sellers, while poetry and other specialist literature is relegated to small presses whose output doesn’t show up in Barnes & Noble. That’s very unlikely to change. Amazon and other online sales have been a shot in the arm for small presses, just as Netflix has made it far easier for people to see films they probably would not otherwise have access to. (Our plumber told me the other day that he had been watching a bunch of recent German films downloaded from Netflix. Well, that’s Madison, as we say; high educational level per capita. But most people have the same option, if they wish.)

Art-houses are scarce in small cities and towns, but such places are not likely to have opera houses either, or galleries with shows of major modern artists, or bookstores which offer 125,000 titles. (As I recall, that’s what Borders claimed to have when it first opened in Madison. Now they seem to be working on that many varieties of coffee.) Opera or ballet lovers are used to traveling to cities where they can see productions, and serious Wagner buffs aim to make the pilgrimage to Bayreuth at least once in their lives.

David and I are lucky. It’s vital to our work to keep up on world cinema, so now and then we travel to festivals and wallow in movies for a week or two. Quite a few civilians plan their vacations around such events, too. We’ve run into people in Vancouver who say they save up days off and take them during the festival. Naturally not everyone can do that, but not everybody can see the current Matisse exhibition in Chicago (closes June 20) or the recent lauded production of Shostakovich’s eccentric opera The Nose at the Metropolitan. I really wish I had seen The Nose, but I don’t really expect the production to play the Overture Center here.

To some people, film festivals might sound like rare events that inevitably take place far away, like the south of France. Those are the festivals that lure in the stars and get widespread coverage. But there are thousands of lesser-known festivals around the world, dedicated to every genre and length and nationality of cinema. For those who like to see old movies on the big screen, Italy offers two such festivals, Le Giornate del Cinema Muto (silent cinema) and Il Cinema Ritrovato (restored prints and retrospectives from nearly the entire span of cinema history; this year’s schedule should be posted soon). Last month in Los Angeles, Turner Classic Movies successfully launched its own festival of, yes, the classics. Ebertfest itself began with the laudable goal of bringing undeservedly overlooked films to small-city audiences, specifically Urbana-Champaign, Illinois. It was and is a great idea, and it would be wonderful if more towns in “fly-over country” had such festivals.

The films we don’t see

Usually when someone calls for more support of independent or foreign films, there seems to be an implicit assumption that all those films are deserving of support, invariably more so than Hollywood crowd-pleasers. If a filmmaker wants to make a film, he or she should be able to, right? But proportionately, there must be as many bad indie films as bad Hollywood films. Maybe more, because there are always lots of first-time filmmakers willing to max out their credit cards or put pressure on friends and relatives to “invest” in their project. There’s also far less of a barrier to entry, especially in the age of DYI technology.

True, the indie films we see seem better. By the time most of us see an indie film in an art cinema, it has been through a pitiless winnowing process. Sundance and other festivals reject all but a relatively small number of submitted films. A small number of those get picked up by a significant distributor. A small number of those are successful enough in the New York and LA markets to get booked into the art-house circuit and reach places like Madison. Yes, some worthy films get far less exposure than they deserve. But many more films that would give indies a bad name mercifully get relegated to direct-to-DVD, late-night cable, or worse. On the other hand, most mainstream films, no matter how dire their quality, get released to theaters. Their budgets are just too big to allow their producers to quietly slip them into the vault and forget about them.

The winnowing process for art-house fare happens on an international level as well. A prestige festival like Cannes dictates that a film they show cannot have had a festival screening or theatrical release outside its country of origin. Programmers for other festivals come to Cannes and cherry-pick the films they like for their own festivals. Toronto has come to serve a similar purpose, especially for North American festivals. Some films fall by the wayside, but the good ones attract a lot of programmers. These films show up at just about every festival. By the way, that kind of saturation booking of the year’s art-cinema favorites at many festivals means that the distributors are more and more often supplying digital copies of films to the second-tier events. Going to festivals is no longer a guarantee that you’ll be seeing a 35mm print projected in optimal conditions. At the 2009 Vancouver festival, I watched Elia Suleiman’s The Time that Remains twice, because it was a good 35mm print and I suspected that I’d never have another chance to see it that way.

To each film its proper venue

There’s no way that every deserving film will reach everyone who might admire it. Condemning the crowds who frequent the blockbusters won’t help open new screens to offbeat fare. If someone loves Avatar, as long as they keep their cell phones off, refrain from talking, and don’t rustle their candy-wrappers too loudly, as far I’m concerned they can go on believing that this is the best the cinema has to offer. Simply showing these audiences a film like A Serious Man, say, or Precious isn’t going to change their minds about what sort of cinema they prefer. To break through decades of viewing habits, such people would need to learn new ones, which takes time and effort. People’s tastes can be educated, but the odds are usually against it actually happening.

Finally, in defending art cinema against mainstream multiplex fare, commentators often cite Avatar or Transformers or the latest example of Hollywood’s venality and audience’s herd-like movie-going patterns. Yet every year major studio films come out that get four stars or thumbs up or green tomatoes. Last year, we had Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs, Up, Inglourious Basterds, Coraline, and a few others that were well worth the price of a ticket. All of them did fairly well at the box-office while playing in multiplexes. Some readers might substitute other titles for the ones I’ve mentioned, but to deny that Hollywood is bringing us anything worth watching seems blinkered. As I said in 1999 at the end of Storytelling in the New Hollywood, where I criticized some aspects of recent filmmaking practices, “In recent years, more than ever, we need good cinema wherever we find it, and Hollywood continues to be one of its main sources.”

Ultimately my point is that in this stage in cinema history, international filmmaking has settled into a defined group of levels or modes. Hollywood gives us multiplex blockbusters and more modest genre items like horror films and comedies. They bring us the animated features that are among the gems of any year’s releases. Then there are the independent films and the foreign-language ones which together form festival/art-house fare. There are also the experimental films, which play in festivals and museums. The institutions that show all these sorts of films have similarly gelled into specialized kinds of venues suited to each type. A broad range of films is still being made. There are some few really good films in each category made each year. The question is not how many worthy films are getting made but how much trouble it takes to see them.

None of the current types of institutions is likely to change on its own. What will make a difference is the growing possibilities of distribution via the internet. Filmmakers who get turned down by film festivals can produce, promote, and sell their movies via DVD or downloads. True, recouping expenses that way is so far a dubious proposition; it’s probably easier to get into Sundance than to do that. As I mentioned, digital projection may make some festivals less attractive to die-hard film-on-film cinephiles. On the other hand, in some towns opera-lovers who can’t get to the big city now can see a digital broadcast of a major production each week at their local multiplex. Not as exciting as a trip to the city to see it live, but a lot cheaper and hence within the reach of a lot more people’s means. All sorts of other digital developments will change movie viewing in ways we can’t yet imagine.

_______________

Jim Emerson has been covering the Film socialisme battle of the reviews on Scanners, with quotes and links to the ones I mentioned and more. He also demonstrates that people have been baffled by Godard since Breathless, with reviews that “are, incredibly, the same ones he’s been getting his entire career — based in part on assumptions that Godard means to communicate something but is either too damned perverse or inept to do so. Instead, the guy keeps making making these crazy, confounded, chopped-up, mixed-up, indecipherable movies! Possibly just to torture us.” He offers as evidence quotes from New York Times reviews over the decades.

Eric Kohn gauges the controversy and offers a tentative defense of the film on indieWIRE.

For our reports on various festivals, see the categories on the right. We discuss Godard’s compositions, late and early, here and his cutting here.