Archive for the 'Directors: Anderson, Wes' Category

Rebooking at THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL

DB here:

I didn’t plan it, but this has been the year of Wes Anderson on our blog.

After an entry on The Grand Budapest Hotel and its play with aspect ratios, I posted an analysis of Moonrise Kingdom (my favorite Anderson movie). Now comes a book from the indefatigable Matt Zoller Seitz that continues the work of his splendiferous Wes Anderson Collection.

Matt provides critical commentary, natch, along with many interviews with Anderson and his creative team. Some critics have a look-in as well. I add my $.02.

You can read more on Vulture here. Available from Abrams on 10 February–too late for the December holidays, but well ahead of Valentine’s Day.

Proof! and a minor mystery

DB here, sort of:

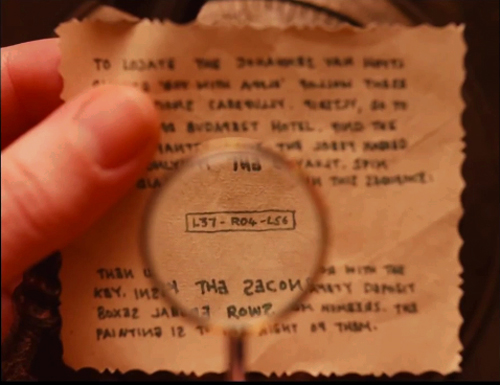

Even doggedly determined readers of this blog may not have seen the codicil to my infuriatingly long entry on The Grand Budapest Hotel. I revisit those remarks now, only because coming back from my trip to Yurrrp, I have evidence of a version that many cinephiles may not see. Here’s what I appended to the old post:

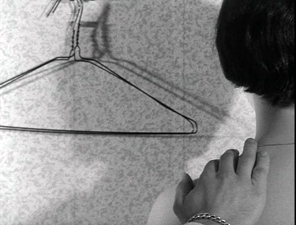

Flying here the other evening, I watched The Grand Budapest Hotel on the plane, just to see what adjustments might have been made. (“This film has been modified to fit this screen and edited for content.”) Surprisingly, the aspect ratios were all preserved. The cuss words were cut out, as was the fellatio shot (but not the guillotined fingers). The most startling change was that the painting of female sexual congress had become a big, blank white one in the Rauschenberg mold. Was it an alternative shot for the airline version, or was the naughty one digitally whitewashed?

Flying back, diligent film researcher that I am, I took a shot of the bowdlerized image. My questions remain. I could imagine it as an Anderson joke, but also as a default for a censorious post-production.

MOONRISE KINGDOM: Wes in Wonderland

DB here:

“An auteur is not a brand,” argues Richard Brody. Not always, I’d suggest; but it can happen. And it’s not necessarily a bad thing.

Wes Anderson has found a way to make films that project a unique sensibility while also fitting fairly smoothly into the modern American industry. He has his detractors (“I detest these films,” a friend tells me), but there’s no arguing with his distinctiveness. The Grand Budapest Hotel is perhaps the most vivid example of Andersonian whimsy as signature style.

In any case, before summer’s end I want to look at the auteurish aspects of another Anderson film. Whether you admire him, abominate him, or have mixed feelings, I think that studying this film can show us some interesting things about authorship in today’s film culture.

Toy worlds

When I’m making a movie, what I have in mind, first for the visuals, is how we can stage the scenes to bring them more to life in the most interesting way, and then how we can make a world for the story that the audience hasn’t quite been in before.

A film auteur is often described as having a characteristic tone, an attitude, and recurring themes. But we also find more tangible marks of authorship. One is a tendency to create distinctive story worlds. Hawks gives us milieus filled with stoic, sometimes grimly resigned professionals. Scorsese presents manic, sometimes vicious worlds that encourage his protagonists to go too far.

If the auteur’s story world is the what, plot patterning and cinematic narration give us the how. How are the actions arranged to create an arc of engagement? How are the events rendered in film style—the texture of images and sounds?

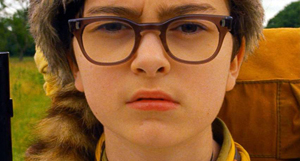

It seems clear that no auteur can be absolutely unique; each one works with norms and conventions given by tradition. For instance, a great many US independent films subscribe to the Hollywood convention of the goal-driven protagonist. Moonrise Kingdom accepts it too: Sam and Suzy want to be together, and their aims propel the action. Anderson and co-screenwriter Roman Coppola even give us the classic formula of lovers, kept apart by society, who escape to freedom in the wilderness. Likewise, the film maintains the convention of multiple lines of action: it creates parallels between the idealistic Suzy-Sam romance and the pallid routine of her parents’ marriage, as well as the hint of emerging affection between the phone operator Becky and Scoutmaster Ward.

Like a mainstream film, Moonrise Kingdom is at pains to build the plot toward a crisis—the second elopement of the couple and the massive storm that hits the region. The film turns the storm into a deadline: It will hit, says Bob Balaban’s narrator, “in three days’ time.” And as in a classical Hollywood film, the couple’s problems are solved and we get an epilogue showing their happy, if somewhat covert union.

Anderson has absorbed some lessons from mainstream cinema in more specific ways, I think. Since the Star Wars series (1977-on), we’ve seen Hollywood ever more eager to try “world-making”—adapting the traditions of fantasy, science-fiction, and comic books to creating fairly separate realms governed by their own rules. Batman and Superman adaptations of the 1980s and after followed this line, with Lord of the Rings proving that world-making could sustain long-running franchises (Harry Potter, the Marvel universe).

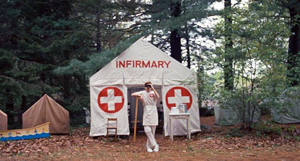

Anderson follows Lucas in creating his own worlds, but outside the conventions of space opera. We can find more or less parallel worlds in The Royal Tennenbaums and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, but Moonrise Kingdom may be the most elaborate example. It takes place in terra incognita, a cluster of imaginary islands presumably on the upper Atlantic coast. The name of the primary island, “New Penzance,” reminds us of the fantasy-worlds of Gilbert and Sullivan. There are make-believe Amerindians (Chickchaws) and the Khaki Scouts are parallel to the Boy Scouts, with Accomplishment Buttons instead of Merit Badges. The Scout regalia are given us in the sort of fussy detail that Anderson has long enjoyed.

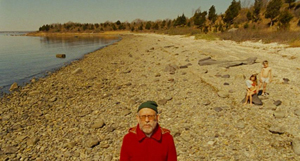

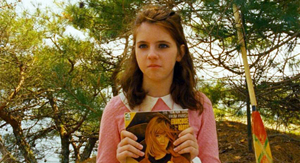

Parts of the story are relayed by a gnome-like Narrator whose range of knowledge includes past, present, and future. He suggests a fairy-tale wizard or bard. An ancillary film tells us that he’s the librarian of New Penzance—the tribal chronicler as small-town administrator. (The existence of this short film serves to reinforce the pretense that New Penzance exists.) Then there are the young-adult books that Suzy carries with her. They’re fictitious but they get strongly tagged to aspects of the action. The books and the scouting gear take on the same solidity as retro details like Suzy’s battery-powered phonograph and Sam’s jar of Tang: 1965 stuff is recruited to flesh out Anderson’s miniature world.

Suzy’s books remind us that New Penzance, like other Anderson story worlds, is redolent of childhood. The film’s opening presents a family’s home as a dollhouse filled with toys and games. Once we’ve seen the fabric pictures rushing past on the walls, the landscapes they preview retain a miniaturized quality.

Those landscapes themselves have a childish defiance of gravity, as when we’re introduced to the poles at the tidal canals and when the Scouts build their tree house improbably high. This motif of top-heaviness eventually yields a sight gag when we learn the implausible fate of Redford’s motorcycle.

Childhood is everywhere. The music we hear in the opening is Britten’s Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, played by three little brothers on a phonograph and narrated by a child for one of Leonard Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts. Throughout the film we hear grownup music designed for kids, such as bits of Bernstein’s rendition of Saint-Saens’ Carnival of the Animals.

Benjamin Britten’s music is central to the film’s soundtrack, from his juvenilia (Simple Symphony, songs from Friday Afternoons) to his later opera A Midsummer Night’s Dream and its chorus of child fairies. A performance of Britten’s church parable Noye’s Fludde is the occasion of Sam’s first encounter with Suzy, and it prophesies the devastating storm of a year later. Carrying this kid-friendly ethos further, Anderson designs his closing credits so that Sam’s voice-over can anatomize Alexandre Desplat’s score, instrument by instrument.

If Britten suggests childhood vitality, the mournful Hank Williams tunes evoke adult disappointment. They’re associated from the start with the lonely, not-overbright Captain Sharp. When Sam’s canoe odyssey is accompanied by the fantasy Williams song “Kaw-Liga,” about a wooden Indian yearning for the carved woman across the street, Anderson suggests a parallel between two lonely, yearning males, and tagging it to Sam prefigures his eventual alliance with his surrogate father.

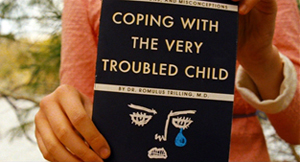

A tradition of twee

The density of this childish New Penzance, like that of other DIY cinematic worlds, supports a tendency I talked about in The Way Hollywood Tells It. For some time now, filmmakers have been filling their films with details that can be discovered on re-viewing, particularly on the DVD format, which allows us to stop and study a frame. The musical citations I just mentioned can be researched after an initial viewing, and perhaps cinephiles will notice that the therapy book’s cover is a riff on Saul Bass’s credit sequence for Bonjour Tristesse (like Françoise Hardy, a link to Left Bank pop culture).

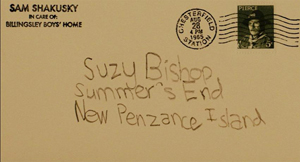

Still, on the first pass we’re unlikely to notice that the stamp on Sam’s postcard to Suzy bears the likeness of Commander Pierce.

Likewise, only after many viewings did I notice that the peculiar flaming-scissors abstraction during the skirmish in the woods is given the same design as that on the motorcycle and helmet of the despicable, and rightfully lacerated, Redford.

And in the epilogue, we might spot that Sam, having cast off his Accomplishment Buttons, has kept his mother’s pin on his new Island Police uniform.

Art and commerce again: What exec could object to loading every rift with ore when it supports ancillary sales to the fan faithful?

Some people find an inward-turned world like this to be fey, coy, twee, infantile, precious, or self-indulgent. It seems to me, though, that Anderson’s work from The Life Aquatic onward links up with a literary tradition we associate with J. M. Barrie and G. K. Chesterton. These writers employed childhood fantasy in an effort to imagine a richer, livelier realm behind prosaic reality. Another kindred spirit would be Winsor McCay, like Anderson an obsessively meticulous stylist who gives heft and lilt to dream worlds. In cinema we might recall Greenaway’s The Falls (1980), as obsessive and precious a project as can be imagined.

Indeed, why not mention the most famous figure of all? There is a trace of Lewis Carroll in Moonrise Kingdom’s looking-glass world—its strangely safe tree house, its deadpan absurdity, the habit of lawyers talking as if always in court. Like Carroll, Anderson doesn’t shrink from cruelty; the death of Snoopy is as perfunctory as that of the oysters on which the Walrus and the Carpenter tearfully dine.

Significantly, modern efforts to reenchant the world are often framed by loss. Wendy comes back from Neverland, Little Nemo awakes with a thump, Alice must return to lazy and boring afternoons. Anderson too evokes the fading of enchantment. Moonrise Kingdom takes place at the onset of autumn, and Suzy’s family lives at Summer’s End. Unlike other modern explorations of faerie, however, this one lets its characters wake up in something approximating their dream life.

Day by day, with interruptions

In accord with the child-based story world, the plot of Moonrise Kingdom provides something of a modern fairy tale. A runaway orphan who retains a token of his parentage heads out for the wilderness. A princess imprisoned in a tower scans the horizon for her rescuer. Lovers exchange messages before they escape into a realm of danger and death. They are rescued by a beneficent authority who will allow them to stay together.

Of course it’s a meta-exercise, since its authors and audiences are self-consciously deploying fairy-tale conventions. But as Barrie and Chesterton and Carroll show, enjoyment of artifice is central to art. Anderson accordingly stylizes both his plot structure and his narration.

He has long been drawn to block construction, building his plots out of big chunks that are often signaled explicitly. In Moonrise Kingdom, the chunks divide up in unusual ways—part, again, of this auteur’s cinematic signature.

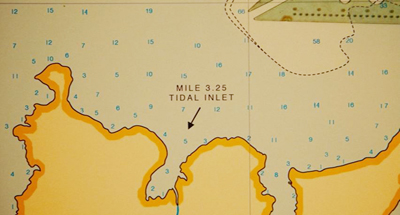

At first we might think we can just track the adventure day by day. On 2 September 1965 Sam goes AWOL from scout camp and Suzy sets out with her belongings. On 3 September the couple fend off their pursuers—the battle of arrow, BB gun, and scissors—and make camp on Mile 3.25 Tidal Inlet. There they swim, dance, and spend the night. On 4 September they’re captured and separated.

But that night the scouts help them escape again, and all head for New Lebanon. The “marriage” of Sam and Suzy on the 5th leads to their flight to Saint Jack Wood Island just as the storm hits. Before they can make a lovers’ leap from the church steeple, Captain Sharp rescues them and arranges to be Sam’s foster parent. These four days are sporadically marked by changes from day to night and some remarks, as when Scoutmaster Ward dictates into his tape recorder. An epilogue is reserved for 10 October.

Running athwart the day-by-day divisions are other blocks. Actually, the first day is shown us three times, via shifts in narrational attachment. First we’re with Scoutmaster Ward, his charges, and Captain Sharp, all of whom are searching for Sam. After Ward dolefully ends his audio diary entry (“Let’s hope tomorrow is better”), Anderson cuts to Sam in the stolen canoe.

You might think this scene of Sam paddling is taking place the next day, but actually it skips back to the morning of the 2nd, when he sneaked off. Thereafter we’re attached to him when he meets Suzy in the meadow and they share their first day on the run. Then the plot skips back again to earlier that night, when Mrs. Bishop calls Suzy to dinner and discovers that she’s gone.

The 2 September section is even more complicated than I’ve suggested. When Suzy and Sam rendezvous in the meadow, their encounter is interrupted by a flashback to their first meeting a year earlier (signaled by a title). Later, the Bishop-centered evening section is interrupted by another block, a flashback montage triggered by Mrs. Bishop’s discovery of the couple’s love letters.

Here Anderson provides important backstory paralleling the two kids’ reasons for running away. Sam is bullied by the older boys in the foster-family-compound run by the Billingsleys, and Suzy blows up at her parents and schoolmates. By the end of the third iteration of 2 September, all the major forces in the drama have been delineated.

The two expository flashbacks give us more reason to care about Sam and Suzy in the following scenes, particularly during their skirmish with the Khaki Scouts squadron. Redford’s bullying ways, ignoring Ward’s orders to avoid violence, earn him a lumbar thrust from Suzy’s scissors, and it’s a mis-aimed arrow that wipes out poor Snoopy.

The couple’s idyll, presented as more or less another block, becomes the center of the film. It ends, at the midpoint of the running time, with Suzy reading: “Part Two.”

After they’re captured, Mr. Bishop vows to keep Suzy from Sam. Worse, Captain Sharp learns that Sam is headed for an orphanage and maybe shock therapy. This will encourage Sharp to defend and rescue the two kids at the climax.

With this crisis looming, the plot gives us a sort of nocturne on the evening of September fourth and the dawn of the fifth. In the night, all the players mull over what has happened: Suzy and her mother, Sam and Captain Sharp, Mr. and Mrs. Bishop, and Scoutmaster Ward. But this isn’t merely downtime. The Scouts in their treehouse decide they’ve treated Sam unjustly and set out to help the couple. This decision propels the climax.

By the morning of the final day, Sam and Suzy are reunited and ready for their mock marriage. All that remains is for the storm to disrupt things (even giving Sam some shock therapy by lightning), but also to set things right. The epilogue shows the new stable state of the story world, tying together the plot action neatly. Scoutmaster Ward, reinstated from disgrace, has replaced Captain Pierce’s picture with Becky’s. Sam has a foster father, and he can covertly see Suzy every day.

The magic power of binoculars

Narration involves the moment-by-moment flow of story information, organized around the key question: Who knows what, when?

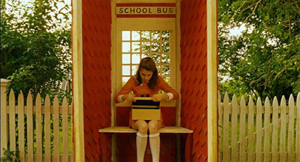

A simple example: Early in the film Suzy finds a letter in the family mailbox. She takes it to the bus shelter and reads it. When she’s done, she looks up resolutely at us and slips the letter into a shoe box.

What was in the letter? The narration has suppressed that information, stirring up curiosity and preparing us for what, many scenes later, Mrs. Bishop will reveal when she finds it: Sam’s final message about their rendezvous. Moreover, the narration flaunts its suppressiveness: She looks at us as if insisting that the message is private.

Unlike the letter scene, which suppresses information, the opening tours of the house give us a fair amount, but we’re not yet in a position to understand it. This applies to our glimpses of the scissors and the New Penzance locations, but there’s also the vertically rising shot showing Suzy’s suitcase in the attic along with her cat peeping out of the fishing creel.

This becomes significant only later, when we realize that Suzy is preparing to bolt.

The narrational process mobilizes film style, both visual and auditory, to engage us in a constant process of expectations—stated, prolonged, fulfilled, or cheated. Consider Suzy’s binoculars. Early in the film we see her looking through them, but we don’t see what she sees. What is she looking at? Or looking for? Soon enough we’ll see that she manages to learn of her mother’s affair with Captain Sharp.

Once we’re set up for the binoculars device, Anderson can use it elliptically. In the meadow we see Sam through binoculars, so we’ll assume that Suzy is looking at him, even if Anderson doesn’t show the customary head-on reverse shot of her.

In effect, this image of Sam is the answering POV shot that has been missing in the early sequences.

But at the climax, when Sam rushes back to camp to fetch Suzy’s binoculars, he’s again caught in their field of view. This immediately leads us to ask: Who’s watching him? Anderson has stuck to Sam in the scene, so we get a gratifying surprise when we learn that the odious Redford has grabbed the glasses and is watching Sam’s search.

Or consider the film’s opening as a narrational gesture. The toy world that the tracking shots present is packed with story information. The very first image shows a fabric version of the Bishops’ house, flanked by Suzy’s left-handed scissors; the picture will soon be echoed by an establishing shot.

Shot by shot, the film channels information in order to set up expectations, to prolong them, to confirm them, or to deflate them. This is how cinematic narration can engage us.

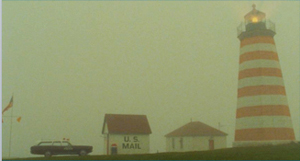

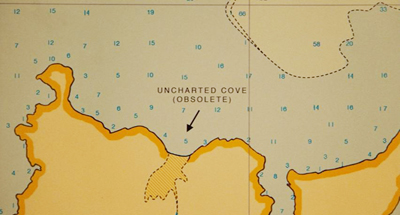

The gnome-like narrator is another source of information. Anderson has compared him to the Stage Manager in Our Town, who can address the audience but also interact with other characters. His opening explanation supplies factoids about this imaginary landscape, while foreshadowing things explicitly (the storm) and implicitly, as with this image that looks forward to Sam and Suzy’s interlude at Mile 3.25 Tidal Inlet.

Narration doesn’t just pass along information; sometimes it suppresses it. It can point out when it’s hiding something, as when the film refuses to show us Suzy’s letter. Sometimes information is noticeably incomplete, as when only bits of Suzy’s and Sam’s correspondence are relayed to us. Another instance is the elliptical handling of the Khaki bullies’ attack on the couple, with a glimpse of an arrow and Paul-Sharits-ish flashes of scissors. Only quite a bit after the assault do we see the damage.

At other moments a film’s narration can create an informational gap that it doesn’t fill, only to do so later. During the central idyll Moonrise Kingdom omits a crucial piece of information and puts it in place only at the very end.

Down the aisle and face to face

Cinematic narration involves stylistic choices as well, and here again Anderson has sought an identifiable look and feel. In an earlier entry on The Grand Budapest Hotel, I talked about his adherence to planimetric images, the tendency to fix the camera at right angles to a background plane and then arrange figures either horizontally, like clothes on a line, or in profile.

Likewise, Anderseon employs what I’ve called compass-point editing. He usually puts the camera between the characters so that they face us in shot/ reverse-shot.

Or he films the action from straight-on, straight-back, or at a right angle. This geometry can be extended to camera movements: moving lateral and parallel to the planes of the shot, or panning at right angles, or zooming along the lens axis. Another extension is the straight-down angle, which is another variant of shooting at a different right angle to the action.

Planimetric shots and compass-point editing aren’t absolutely new with Anderson, but he uses them more thoroughly than most other filmmakers do. They govern his staging to the extent of pushing him away from realism. How plausible is it that all the Khaki scouts would line up on one side of the picnic table? Or that Ward wouldn’t notice, in a later scene, that all of them are gone?

Anderson’s use of such imagery evokes silent-film comedy, especially the compositions of Keaton, but these shots also suit a fairy-tale world. The stylized naivete of these compositions recalls children’s drawings, which tend to spread figures out against a flat background. (This was prefigured in the squashed perspective of the Bishop house as portrayed in the fabric picture.)

When a director commits to a particular style, he or she may have limited choices on other fronts. A good example is the climactic confrontation of all the adults in the St. Jack Wood church. Anderson might have staged this in many ways, but his stylistic preferences make the central aisle the most feasible arena. So we get the groups facing one another, in reverse-angle depth, moving from one planimetric composition to another, the cutting being either 180-degree reverses or simple axial cuts (zero-degree changes of angle). Sometimes the actors pivot to provide foreground profiles and frontal faces in the distance.

Once you the filmmaker embrace such a marked style so thoroughly, how can you signal special moments? In Moonrise Kingdom, Anderson does this by reverting to more commonplace technical choices.

When Suzy and Sam meet in the dressing room in 1964, we get straightforward 180-degree reversals.

And when they re-meet in the meadow, we get a mixture of profile and head-on shots.

But then Anderson starts to exempt them from the usual spatial strictures. The correspondence montage, for instance, retains the perpendicular framing but decenters his protagonists in mirror-image fashion.

As they get to know one another on their camping trip, the facing-front staging becomes less severe, more modulated.

And finally, when they admit their love to each other, Anderson gives us conventional ¾ views of faces and over-the-shoulder angles. These setups are reiterated when they embrace and dance.

At an emotional peak, Anderson sharply violates the film’s intrinsic norm by bringing in a common technique—which now gains a force it doesn’t customarily have.

Summer’s end

The epilogue recapitulates both narrative and stylistic features. There’s another lateral tracking shot of the Bishop house, but now Sam is painting in a space that was empty at the start.

Again Suzy is using her binoculars, but now, dressed in cheery yellow, she has something worth seeing.

On the soundtrack we hear Britten’s “Cuckoo” song, a reiteration of the summer’s-end motif. The cuckoo, born in spring, enjoys the summer but must eventually fly. As we hear this over Sam’s departure through the window, Anderson’s camera slides down to reveal that Sam’s picture presents a landscape that has now vanished.

Here is the big ellipsis that Anderson didn’t flag in the central idyll. When Sam was painting a stretched-out Suzy at Mile 3.25 Tidal Inlet, they had agreed that the name of the place was insipid. She says she’ll think of a new name. But we’re told no more about the matter. In the epilogue, when we see Sam’s picture, we realize that they have given the place a better name: Moonrise Kingdom, inscribed in white on the shore.

“This is our land!” Sam had shouted when they looked out at the inlet. Like Anderson’s imagining of a parallel world of childhood, Sam has recreated, in the manner of modern fairy tales, something that is gone. As if in sympathy with the gesture, the film’s closing shot updates one that was given us during the scenes on the shore, with the yellow pup tent now pitched as the mist rolls in.

Did the couple really write MOONRISE KINGDOM on the shore during their stay? Hard to say. What matters is that, provoked by Sam’s picture, the film’s narration concludes by asserting the power of imaginative artifice.

Selling directors

Floating Real Scarab Beetle Earrings.

Thinking about auteurs has always obliged us to focus on the interchange between industrial demands and artistic aims.

In general, I don’t see an inevitable conflict between market demands and artistic expression. (I argue for this here and elsewhere.) True, often producers and executives and censors mangle creators’ efforts. But some directors know how to do what they want with what they have. For example, Hitchcock’s artistry benefited from his status as a celebrity director. He won substantial budgets and greater control of his work. And sometimes the suits’ demands improve a film (as I suggest here).

Historically, it isn’t easy to separate auteurs from their brands. Let’s assume that a branded auteur is one who is known to a broad public for certain qualities of his or her films. A simple measure would be an ordinary viewer saying “I like X movies,” where X is the name of the director.

Hitchcock is nearly everybody’s clear-cut example of an auteur, but by the time the Cahiers du cinéma critics were forging their conception of cinematic artistry, Hitch was a brand too. How else to explain the 1940s-1950s book collections bearing his name, or The Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine, or the tag, “The master of suspense”? Hitchcock participated in this image-building with his jokey interviews, his walk-on appearances in his movies, and his reputation as a bland-faced prankster. Few directors today foster such shameless self-promotion. Also branded were Chaplin, Disney, Welles, and Cecil B. DeMille. Among the cinephilic public there was recognition of Huston, Sturges, and a few other hands.

Hitchcock is nearly everybody’s clear-cut example of an auteur, but by the time the Cahiers du cinéma critics were forging their conception of cinematic artistry, Hitch was a brand too. How else to explain the 1940s-1950s book collections bearing his name, or The Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine, or the tag, “The master of suspense”? Hitchcock participated in this image-building with his jokey interviews, his walk-on appearances in his movies, and his reputation as a bland-faced prankster. Few directors today foster such shameless self-promotion. Also branded were Chaplin, Disney, Welles, and Cecil B. DeMille. Among the cinephilic public there was recognition of Huston, Sturges, and a few other hands.

Of course many of the auteurs discovered by the Cahiers critics were unknown to the public at large, and they didn’t make profitable pictures. In 1940s Hollywood, the successful Lang was Walter, not Fritz. But as the film industry developed, and as auteur criticism became prominent, directorial distinctiveness became a marketing angle. By the 1970s, the movie brats, along with older hands like Altman, were presenting themselves as having “personal visions” carried by their films.

More recently, US independent cinema has come to depend on several appeals (sex, social comment, and the like), but surely authorship is a central one. The indie scene exploits the signatures of directors as different as Lynch, Jarmusch, and Paul Thomas Anderson. The emergence of younger talent like Nicholas Winding Refn and Kelly Reichardt conforms to a similar pattern; people follow and support emerging directors, and distributors publicize the films that way. No wonder James Schamus, founder of Good Machine and late of Focus Features, once remarked: “I’m in the business of selling directors.”

This is just a fact of life for ambitious independent filmmakers. Wes Anderson’s cultivation of a distinct style is probably partly a genuine reflection of his personality and partly a matter of willed self-presentation. But of course we’re all indulging in self-presentation, using Goffman’s “impression management,” every time we interact with others.

Like an indie band, Anderson has created a marque unusual enough to let the fans feel they’re in on something keyed to their nonconformist tastes. He has provided the usual panoply of ancillary items, like soundtracks and bonus DVD tracks, but he has allowed others to participate in his world. Amateur videos comment on his style; graphic artists render their own versions of his posters. There are dozens of unlicensed Moonrise Kingdom tchotchkes. Anderson’s willingness to permit all manner of “tribute” memorabilia fits the handmade quality evoked by his films.

Like an indie band, Anderson has created a marque unusual enough to let the fans feel they’re in on something keyed to their nonconformist tastes. He has provided the usual panoply of ancillary items, like soundtracks and bonus DVD tracks, but he has allowed others to participate in his world. Amateur videos comment on his style; graphic artists render their own versions of his posters. There are dozens of unlicensed Moonrise Kingdom tchotchkes. Anderson’s willingness to permit all manner of “tribute” memorabilia fits the handmade quality evoked by his films.

Call it Geek Chic if you want, but it exemplifies an important and potentially valuable part of modern popular culture. For such reasons, I don’t see anything inherently bad about being an auteur with marketing possibilities. People don’t seem to object to David Lynch’s coffee and his nightclub. With eccentricity, spontaneous or willed, all is permitted.

My argument assumes that the term “auteur” picks out something neutral. For some people, though, it’s not a description but a compliment; there can be no bad auteurs. But I think we can have both weak auteurs—filmmakers distinguished only by technique or tone or narrative strategy—and downright bad ones as well. I have my own list.

This piece is based on a talk I gave earlier in July at the Hochschule für Fernsehen und Film in Munich. Thanks to Andreas Rost and Michaela Krützen for arranging my visit.

In the New Yorker column I mention, Richard Brody develops an argument along a different line than mine. As I understand it, he’s replying to critics who claim that the auteur approach overrates individual creativity at the expense of collaborators. He’s also objecting to the expanding search for ever more auteurs, who turn out to be minor artisans at best. My remarks are focused on different issues.

For much more on Moonrise Kingdom consult Matthew Zoller Seitz’s indispensable The Wes Anderson Collection. Michael Newman’s Indie: An American Film Culture examines Anderson’s cinema as a development of the “Quirky Indie.” The fan-generated merchandise exemplifies what Henry Jenkins, in his book Textual Poachers, called “participatory culture.”

The three-part anatomy of film narrative I use here is explained in greater detail in this chapter from Poetics of Cinema and this blog entry.

My stills showing Sam’s painting and the extreme long shots of the shore can’t do justice to the originals; I tried bigger proportions, but the MOONRISE KINGDOM inscription remains hard to see. I have to assume that most readers have seen the movie, or will. The image below will have to do.

P.S. 21 July 2014: One sign of a distinctive authorial approach is that it can be parodied. James Fiumara writes to recommend the Saturday Night Live parody of Anderson, applying his style to domestic horror. “I frequently show this to students in discussions of both auteurism and genre conventions. The students all laugh at the parody and then I get them to try to recognize what the parody depends on (namely, their recognizing recurring styles and patterns distinct to Anderson films, recognizing the conventions of the horror home-invasion subgenre, and of course seeing the incongruity between Anderson’s films and the horror genre).” Thanks to James for the link.

P.P.S. 12 September 2014: Guillaume Campeau-Dupras writes to point me toward his 2012 blog on the film, which looks at the film from a perspective related to what Kristin and I have written about (but with many original ideas of his own). I think readers interested in Anderson would benefit from his entry.

P.P.P.S. 2 October 2020: The branding continues! See this story about Anderson-style buildings around the world. Here is a filmmaker who has truly changed how people see their environment.

THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL: Wes Anderson takes the 4:3 challenge

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014).

DB here:

Be shot-conscious! I urged in a blog entry some years ago. I illustrated the point with a tradition of staging and shooting that seemed simple and modest but was actually quite flashy, and even fashionable. Although many filmmakers resorted to it, either often or occasionally, critics hadn’t attended to it. Wes Anderson’s work yielded one of many examples of what I called (swiping from art historian Heinrich Wölfflin) a “planimetric” style.

Ideally, you should look at that entry before reading this one. (To encourage you, I link it again. Not for the last time.) Very briefly, this style involves a frontal presentation of the action. You frame people against a perpendicular background, as if they were in a police line-up. Usually you face them to camera, as in this shot from Godard’s Made in USA.

As we’ll see, sometimes you can frame the characters at right angles to the camera, or turned directly away from the camera. Here are examples from Napoleon Dynamite and from Angelopoulos’ The Traveling Players. (Is this the first time these two movies have been mentioned together?)

The key idea is that the people and the setting aren’t observed from an oblique angle; if the background is perpendicular, the people will stand or sit at 90 or 180 degrees to that.

You can arrange them in some depth too, but again, they are stacked in perpendicular fashion, making each area a pretty strict plane. Here’s an example from Pulp Fiction.

One point of my earlier entry is that this is a surprisingly old strategy; Keaton used it occasionally, and Godard was using it heavily fifty years ago. Here are two shots from Contempt (Le Mépris, 1963).

It has endured in some surprising places. It’s now a go-to option for one-off effects in mainstream cinema. Here are examples from Shutter Island and The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (2013 version).

A few filmmakers make it the basis of an entire film, as I indicate in this entry on Oliveira’s Gebo and the Shadow. And since I wrote the original entry, I’ve drawn on other examples from time to time, particularly from directors who are pastiching Ozu to some degree or another.

Still, Anderson is today the most widely visible example of the style, partly because while others use it sporadically, he is single-minded about it. He has made people shot-conscious (at least when they watch his movies). So after seeing his newest film, I thought it would be fun to think about what distinguishes his approach.

Playing with planes

With the release of The Grand Budapest Hotel, several bloggers have pointed to recurring compositional features, most obviously bilateral symmetry. I’d just add that such symmetry is often used by practitioners of the planimetric approach, with results that sometimes exceed Anderson’s. Here are two shots from Angelopoulos’ Weeping Meadow.

When you think about it, it takes a brave filmmaker (e.g., Godard) to use this approach and not deploy symmetry.

Anderson has used the planimetric approach more extensively in recent years, and he modifies it some distinctive ways. I think particularly of his habit of crowding people together in layers rather than stretching them along a single line. He makes some images look like group portraits or over-posed highschool yearbook shots (The Royal Tenenbaums; Fantastic Mr. Fox).

By employing the planimetric strategy, Anderson gains a somewhat awkward formality, a sense that we are looking from a distance into an enclosed world that sometimes looks back at us. There are as well the sort of comic possibilities that Keaton recognized in Neighbors and The General. A rigid perpendicular angle can endow action with an absurd geometry.

These apparently simple framings often evoke a world of childhood. Just as Kitano Takeshi shows us gangsters behaving like little boys, Anderson’s dollhouse-room frames make adults seem to be toy people arranged just so–like items laid out in a Joseph Cornell box. It’s a style suitable for magical-realist premises like The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, and in Moonrise Kingdom it finds its echo in children’s illustrated books.

All in all, then, I have to salute an American filmmaker who thinks about his images carefully and has incited sensitive viewers to notice them. I think we should go further, though. We can ask: How does Anderson, staying loyal to this tradition, vary the look of the shots? And how does he cut them together?

Cutting around

Consider the editing option first. Unless every scene is to consist of only one shot, the question comes up: How do you maintain the style while cutting? Either you make all your cuts axial, straight in or straight back.; or you create a sort of compass-point editing. This can involve cutting 180 degrees, to what’s “behind” the camera in the initial shot. So if characters are confronting one another, the camera is in effect sitting between them as each looks over or through the lens at the other (Ozu’s Late Autumn).

In effect, this option respects the classic 180-degree line, or axis of action, between the characters. It’s just that the camera sits right on that line. Parking the camera on the axis is a common tactic for subjective cutting, showing us first a person looking, more or less at the camera, then what she or he sees from their vantage point. Our example in Film Art: An Introduction comes from Rear Window.

Ozu used this 180-degree reversal often, but not absolutely; he had a more complicated way of conceiving space, and the 180-degree frontal cuts were only part of it. Kitano made a simpler variant central to his early films.

When I asked Kitano why he did it, he explained that it was exactly the way people saw each other in ordinary life. We face each other. He then added that he was such a naive director when he started that it was the only way he knew to set up scenes. We get kindred images in Terence Davies’ work; his frontality may owe something to the Hollywood musical.

Compass-point editing offers another possibility, that of cutting at 90-degree angles to the background plane or the figures’ position. Chantal Akerman does it throughout Jeanne Dielman 23 Quai du Commerce 1080 Bruxelles (1975).

Anderson exercises all these cutting options inThe Grand Budapest Hotel. Here a planimetric profile 2-shot yields two frontal shots; we shift 90 degrees and then 180 degrees.

Now here’s a 90-degree shift for the reverse shot.

In the passage below, the first cut rotates 90 degrees, and the second cuts in right on the lens axis. In this tradition, an axial cut respects the perpendicular layout of the space.

In such cutting patterns, the compositions keep the action in the same upper zone of the frame from shot to shot. As a result, our eye doesn’t wander much. In long shots, Anderson sometimes follows the classic Hollywood practice of allowing some decentering, as long as the cuts balance one off-center composition against another. Here the changing angles obey the compass-point principle across three shots, and they crisply shift the emphasis from the right side of the frame to the center to the left.

Someone who wanted to deflate Anderson’s visual ambitions could say that his shots are monotonous. Having imposed a big constraint on himself, he’s now obliged to show us that this approach can be varied–in obvious or subtle ways.

One way is through lens length. Most planimetric filmmakers use long lenses, which flatten the space even more. The figures can look like clothes hanging on a line. But Anderson favors quite wide-angle lenses (often 40mm). These make horizontal lines bulge, as in early CinemaScope films (Rushmore, The Life Aquatic).

You can see similar distortions in the straight-on shots of the hotel desk in Grand Budapest, above.

Another way Anderson varies his images is by departing from straight-on angles. As long as the framing maintains a planimetric geometry, we can look down or up at the action. In this passage, again the camera makes 180-degree reverses. This contrasts with the more orthodox shot/reverse shot framings in a comparable scene in The Little Foxes.

In this spirit, Anderson can give us bird’s-eye views, as Matt Zoller Seitz points out in his sumptuous book-length interview with the director. It’s rare, but there are precedents, as in the work of the Coens. In one shot of The Hudsucker Proxy, a movie with an inordinate number of straight-down angles, the inflexible framing creates a joke.

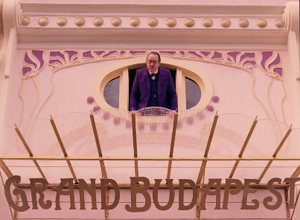

Grand Budapest Hotel has room for some classically funny framings. If you want somebody to look lonely, common practice says, frame the figure off center in a long shot. Here Anderson seems to be having a joke on the convention. He presents it as a POV, although presumably if the Writer were looking at the mysterious man he would put the object of attention in the center of his field of vision.

I think that Anderson’s earliest films weren’t quite so strict in obeying the planimetric and compass-point strategies. Those options were often slipped in as alternatives to more orthodox framing and cutting. But as he’s become more rigorous about using them, he has found ways to put his stamp on some common techniques. Like Ozu incorporating devices of classical continuity into his unique stylistic system, Anderson can recruit certain conventions while staying faithful to his basic approach.

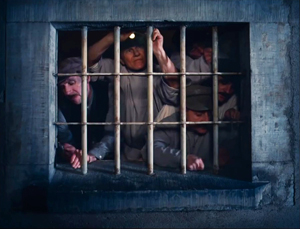

For instance, Anderson sneakily brings in the OTS–the over-the-shoulder framing standard in shot/ reverse-shot dialogue scenes. In one prison scene, Harvey Keitel’s Ludwig is granted an OTS that varies subtly from the more purely straight-on views.

Much the same thing happens with in the punching scene at the reading of the will, when frontal characters are assaulted by fists coming in as if in reverse angles.

Anderson has figured out another way to vary his compositions. I learned this before I saw the movie, thanks to some comments by the cinematographer Robert Yeoman (great name).

High or wide, and handsome

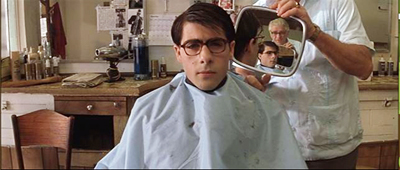

Rushmore (1998).

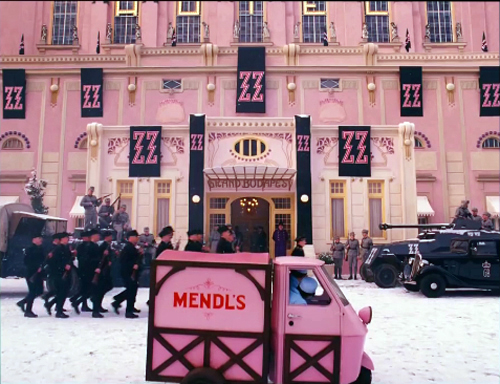

To get the criticky part of this entry out of the way: The Grand Budapest Hotel has all the charm, fussiness, and intricate whimsy typical of Anderson’s work. As often in his films, it cuts its preciosity with moments of offhand brutality (sliced-off fingers) and flashes of naughty sexuality (fellatio, the lesbian painting). With its ensemble cast, sometimes deployed in cameos, it suggests a PoMo remake of those sprawling, self-congratulatory spoofs of the 1960s like The Great Race, Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines, and It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. (The film’s title evokes those all-star films set in hotels, like Grand Hotel and Hotel Berlin.) It’s much better than those, partly because it engages in an oblique way with history, creating a comic-pathetic alternative account of Nazi imperialism. It imagines the collapse of Europe in operetta terms, filtered through Anderson’s pawky humor and distinctive style. I admired the film but don’t feel able to analyze it much after only one viewing. Fortunately for me if not you, its stylistic aspects fit today’s sermonette.

The Grand Budapest Hotel is set in several time periods, and they’re presented via The Blog’s old friend, the device of flashbacks within flashbacks. One character recalls the past or tells a story, and inside that line of action another character recalls or recounts a story, and so on. In Grand Budapest Hotel we move from the present, more or less, to events in the 1980s, then the 1960s, and eventually the 1930s, which constitute the central episodes.

Anderson has shot the frame stories in different aspect ratios. It’s 1.85 for the near present and the 1980s, when the Author recounts meeting the hotel owner. That meeting, set in the 1960s, is shown in 2.40, the anamorphic aspect ratio. The central story, taking place in the 1930s, is presented in classic 1.37, or 4:3 imagery. With typical Anderson butterfly-collector wit, each era gets a ratio that could have been used in a movie at the time. It’s remarkable that Anderson could persuade Fox Searchlight to let him do this.

Most commercial releases in the 1950s and afterward were filmed in some widescreen ratio. In the early days, a popular option was a sort of clothesline staging, centering a single character or balancing others around the central axis: two side by side, three across, four as a pair of pairs, and so on. These shots are from Demetrius and the Gladiators and How to Marry a Millionaire.

Thanks to the widening of the frame, there is less air above the characters and less ground below them. The empty spaces are typically on the sides, particularly in the anamorphic 2.40 ratio. The problem of filling that up was solved, at least for some directors, by moving the camera very close to the actors. Spielberg remarked that he began shooting more close-ups when he filmed in anamorphic.

If you’re inclined to the planimetric approach, it fits the wider format nicely. Anderson wasn’t worried by the extra acreage; he just used the set or empty areas to balance one side against the other. Shots of only one character could be centered, as if posed, and shots of groups could be arranged more or less symmetrically, as in this passage from Moonrise Kingdom. Central perspective helps drive your eye to the main items.

In Grand Budapest, Anderson’s signature framings fit snugly into the scenes shot in 1.85 and 2.40. (The latter has been his favored ratio over the years.) But what about the 1.37 scenes? This brings me to Mr. Yeoman’s remark.

Explaining why he and Anderson watched a lot of films from the 1930s, especially by Lubitsch, Yeoman notes:

We looked at those more to familiarize ourselves with the 1.37:1 aspect ratio, which Wes wanted to use for the 1930s sequences. This aspect ratio opens up some interesting compositional possibilities; we often gave people a lot more headroom than is customary. A two-shot tends to be a little wider than the same shot in anamorphic. It was a format I’d never used before on a movie, and it was a fun departure. You can get accustomed to 1.85 or 2.40 to the point that the shots become more predictable.

Put it another way: Anderson’s penchant for centering and symmetry inclines him toward widescreen compositions that could be simply cropped right and left to fit the 1.37 ratio. His single characters and huddled groups could remain much as before. But in more distant framings you might get a lot of extra space at top and bottom–areas that simply aren’t there in the wide ratios. In other words, Anderson’s multi-format strategy gave him a new problem in maintaining his signature style.

How did he solve it? Many Budapest Hotel shots do leave considerable headroom, as you see in most of the 1.37 examples above. But other shots show Anderson filling his 4:3 frame in varied and engaging ways.

As Ozu showed, for instance, the planimetric option can fill the frame’s upper area when the camera height is below eye level. During the conversation in the car, above, Anderson gets the head of M. Ivan (Bill Murray) in the top of the frame thanks to a low angle. Here are two more examples of filling the upper reaches of the format by use of a lowish camera position.

In the elevator shot, the headroom becomes comic, with M. Gustave and Madame D. seated on the right, the morose bellboy filling the vertical area on the left, and Zero in the middle. The empty space above the couple creates a lively imbalance emphasizing them in a way different from the very balanced framing that centers Henckel among his men.

The set can cooperate. In the first shot below, Zero’s and Agatha’s centered embrace leaves lots of headroom, but the slightly disheveled stack of pastry boxes in the upper background contributes to the sense that they’re engulfed. In the second shot below, part of its humor comes from the rigid geometry of the grid and the way M. Gustave and his colleagues fill in the matrix with their intent faces and busy hands.

In all, Anderson seems to me to find intringuing ways to create visual interest in the 4:3 format. But as with any severe style, you wonder about what’s been lost.

Most obviously, Anderson loses some of the intimacy that comes with more angular and less strict approaches to the classic ratio. We like to see people from 3/4 views too. We also like depth shots that plunge us into a dynamic, diagonal playing space. Here’s a shot from John Huston’s In This Our Life, as precious in its own way as Anderson’s imagery.

As Hogarth pointed out, with the serpentine line in painting and drawing, such shots can lead our eye on “a wanton kind of chase.”

Because directors of the 1920s-1940s accepted a wider range of compositional options than Anderson embraces, headroom simply wasn’t an important problem, as in the Huston shot. Even in simpler shots, classical uses of the 4:3 ratio permitted a flexible organization of figures.

Centered symmetry against a flat ground is a fairly easy compositional strategy, after all. It wasn’t used much in the mainstream tradition because it looks artificial; perhaps only with the rise of art cinema was this sort of self-conscious composition welcomed. In any case, sticking with symmetry sacrifices the more delicate spotting of figures and faces around the frame.

A lot of visual art tries for more supple and subtle twists, torsions, and counterbalancing. Apart from organizing your space along the horizontal and vertical axes, you can try to set figures in delicate array along diagonals. This is why some old-time cinematographers argued that the 4:3 ratio was the best suited to the human body: it can flatter it from any angle.

To get a sense of these possibilities, I’ve compiled a little collection of images from a film that doesn’t boast any outrageously pretty shots: Otto Preminger’s Angel Face (1953). It’s typical of the unassertive approach we find in Preminger’s work of the 1940s and 1950s. He avoids the flashy depth of the post-Kane directors and offers something less aggressive but no less fascinating. Composition and staging integrate expressions, posture, glances, and gestures to create a smooth flow of action. My samples also indicate how rare straight-on views of faces and bodies are in American studio cinema. The 3/4 angle rules.

As with the American films of Lang, Preminger’s work displays a style that’s tough to analyze because the technique isn’t obvious. There’s a marvelous variety in the ways that the 4:3 ratio can render a single figure or two figures, or three, shifting them not around the perfect center of the picture format but around curves and diagonal axes–that yield interest in their own right.

This last comparison isn’t a slam on Anderson. I think well of many of his films, particularly the most recent ones, and I appreciate anyone who takes on a challenge of narrowing his range of creative choices. Once you narrow that range, it turns out there’s a host of new possibilities that pop out. Call it the Ozu strategy: refine your means and you discover nuances nobody else notices.

Still, in art as in life, every choice is a trade-off. It’s worth remembering what one loses by pursuing a particular path. By sticking to his signature look in working with 4:3, Anderson gave himself a problem that didn’t exist for directors of an earlier time, the problem of maintaining a frontal style in a squarish format. I’m glad he faced it and solved it. But I’m also glad that classical filmmakers, quite intuitively, showed how much you could do with an alternative option.

Without any conspiring between us, Matt Zoller Seitz, top expert on Wes Anderson, has just urged critics to write more about film form–to be, among other things, shot-conscious.

Iain Stasukevich’s American Cinematographer article on the making of The Grand Budapest Hotel is well worth your attention beyond the technical matter I latched onto.

The Huston image came to hand because of the previous entry. Go there for more instances of the sort of framing and staging that Anderson and his planimetric colleagues don’t aim at.

I survey the planimetric style in On the History of Film Style and in Figures Traced in Light. A search of this blog’s archive will bring other instances to light. I analyze Ozu’s style in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, available as a pdf here. For more on CinemaScope, you can visit my online lecture.

P.S. 27 March (Hong Kong time): Jonah Horwitz writes with a useful point:

One thing I would add to your summary is that as early as Rushmore, most notably in The Darjeeling Limited, Anderson purposely inserts into his limited stylistic palette selected, isolated “foreign” devices like loose framings, handheld camera, and relatively aimless zooms (as opposed to his more common precise shock-zooms). In some cases, as in the drama-club staging of “Serpico” in Rushmore, these devices serve as citations, in that case to “realist” New Hollywood cinematography. But they also feel very much like the exceptions that prove the rule: they stand out from his usual stylistic register so much that they effectively reinforce the latter. I’m looking forward to seeing Grand Budapest to see if this continues, or if he emphasizes instead a further refinement of his typical gestures.

I agree with Jonah that importing foreign devices often throws into relief a filmmaker’s signature style–a matter of a film’s intrinsic norm getting reinforced by some marked deviation from it. I think of Ozu’s pans or tracking shots, which occur in all his black and white films, and which often just remind us how narrow the style is in the rest of the movie. And sometimes, as in The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice, those camera movements are hybrids or compromises with with his static style. Thanks to Jonah for corresponding.

P.P.S. 27 March: This entry has been revised to eliminate an error. Originally I had said that the play with aspect ratios in the film wouldn’t have been possible before digital projection. Bryce Utting wrote to point out that it was indeed possible on film, since Peter Greenaway’s Pillow Book used both 1.85 and anamorphic widescreen. I had even seen the film and forgotten that! Thanks to Bryce for the correction.

P.P.P.S. 30 March (Hong Kong time): Jim Healy, impresario of our Wisconsin Cinematheque, writes to point out several other films that mix aspect ratios:

The first hour of Redford’s The Horse Whisperer, the urban-set part, is in 1.85. When the characters make it to the open horse country, the image widens to ‘scope. . . . The 2002 Disney animated feature Brother Bear (which isn’t so bad) is 1.85 for about the first 20 minutes and when the principal Inuit character (voiced by Joaquin Phoenix) is transformed into a bear, the picture goes to Scope.

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014).