Archive for the 'Directors: Anderson, Wes' Category

Wesworld

DB here:

Wes Anderson is back on our blog.

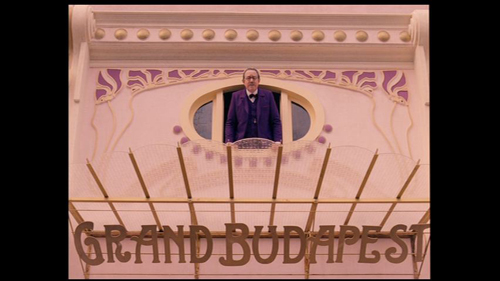

I composed a 2007 entry that tried to trace the stylistic tradition he belongs to (sloganized as “planimetric” staging and “compass-point editing”?). In 2014 the multiple aspect ratios of The Grand Budapest Hotel grabbed my attention. That essay, revised, was included in Matt Zoller Seitz’s anthology on the film, duly teased and announced here. At greatest length, another 2014 entry offered some thoughts on Anderson’s standing as an auteur through an analysis of Moonrise Kingdom (2012).

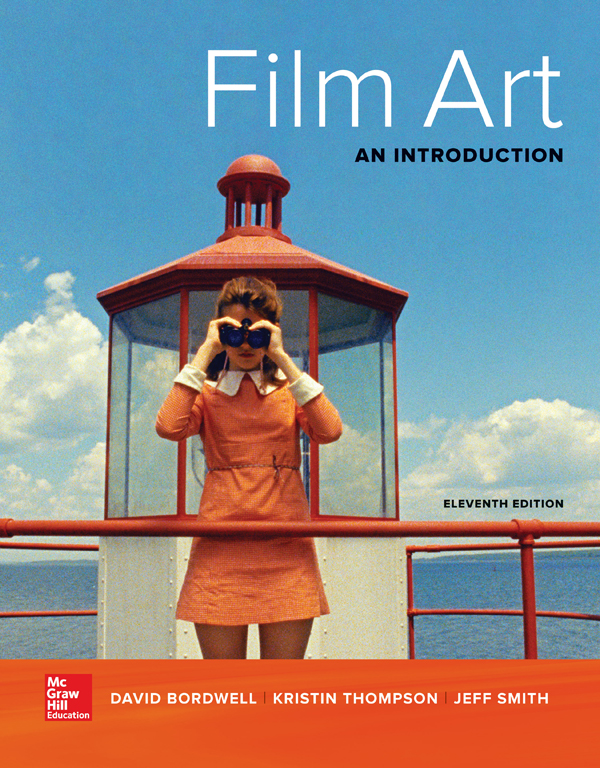

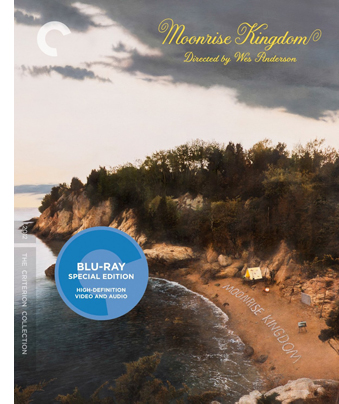

The film has worked its way into the eleventh edition of Film Art: An Introduction, forthcoming in January. In Chapter 11 an analysis of Moonrise Kingdom joins discussions of films by Ozu, Hawks, Hitchcock, Vertov, Scorsese, and other major directors. Moonrise Kingdom, I think, a film that will have lasting interest for young viewers and filmmakers, and it’s a fine vehicle for teaching principles of narrative and style.

Since then I’ve learned more, thought more, and seen more. Specifically, I’ve seen Moonrise Kingdom in the gorgeous new Criterion Blu-ray release.

Since then I’ve learned more, thought more, and seen more. Specifically, I’ve seen Moonrise Kingdom in the gorgeous new Criterion Blu-ray release.

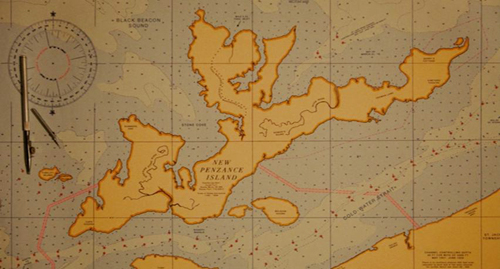

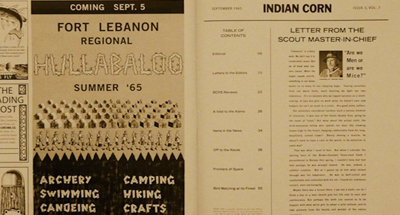

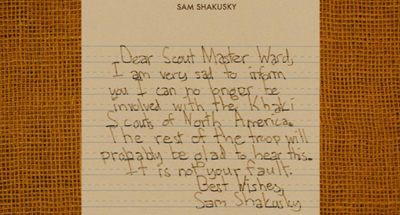

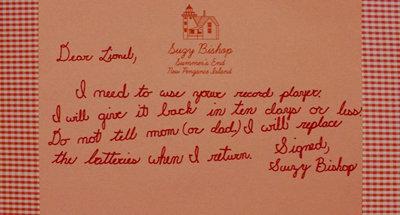

That release bundles in the sort of auteur artifacts my blog entry talked about. The purchaser gets a map of New Penzance, an invitation to the 1964 Noye’s Fludde performance at St. Jack’s, rather unflattering snapshots of the characters, and a postcard of the island ensemble (minus Social Services and the phone operator). On the disc we get Edward Norton home movies (as casual as anybody else’s, but showing some ingratiating behind-the-scenes stuff), some Bill Murray riffs, a brief making-of, and other snippets. The booklet, modeled on the Scouts’ magazine Indian Corn, includes a brief, sympathetic essay by Geoffrey O’Brien and reviews by kids.

A kid also conducts, if that’s the word, the extremely free-form commentary track on the disc. Young actor Jake Ryan, who plays one of Suzy Bishop’s brothers, sort of oversees chat among Anderson, Criterion leader Peter Becker, and participants in the production. Those last are brought in via phone calls. There are bathroom breaks, discussions of San Francisco Chinese restaurants, a Mozart piano performance by Jake, and a moment in which one discussant is accused, doubtless unjustly, of falling asleep. The whole enterprise, cut down from a five-hour marathon, will probably enchant Anderson devotees while giving new ammunition to those who find those admirers nuts, or worse. For my part, I found that Edward Norton and Bill Murray shared some worthwhile bits of acting craft, and Anderson gave some interesting information about the production.

Anderson adepts don’t need me to urge them toward this disc and its accessories. Today I want to think some more about this movie, which after two more viewings hasn’t lost any of its fascination for me. I’ll be concentrating on what it shows about worldmaking on the screen.

Departures, minimal and more

If you stripped off all the enticing elements like the toy lighthouse and the Khaki Scout badges, the gnomelike narrator and the interjected postcards and the implausibly perched treehouse, what do we have? In its bare bones, a pretty simple plot anatomy.

A couple in love, blocked by parental opposition, runs away. After an idyllic day and night, they are captured and separated. Then it all starts again, thanks to the miraculous conversion of some of the boy’s enemies, who decide to help him and the girl escape.

Again the couple flees, this time to be unofficially married. Pursued by parents and the authorities, the couple is trapped in a massive storm and is rescued by the kindly sheriff. They are united to live in a more-or-less tolerated love affair.

Although these are primal patterns of engagement, Moonrise Kingdom wouldn’t claim much interest if this were all it offered, folktale-fashion. As usual in modern narrative, the real interest involves finer-grained plot developments, characterizations, and narrational maneuvers. So the basic anatomy gets flesh, nerves, muscles, and circulating blood. Anderson and co-screenwriter Roman Coppola give us well-defined characters, dramatic situations, and secrets and mysteries and suspense. They play with time and viewpoint, build suspense, trigger surprises, and wrap things up with unexpected neatness. Several of these tactics I tried to chart in the 2014 entry.

Anderson and Coppola could have stopped there, but they didn’t. They went on to invent a world.

You can argue that this world’s main purpose is to distract us from the simple flight/pursuit/capture/rescue dynamic of the basic story action. But I’d argue that the final film benefits from fleshing the core action out in a way that situates it in a unique milieu. There’s also the point that worldmaking is no small achievement. Your task as a storyteller, George Lucas once noted, will change when you have to figure out what your character’s fork looks like.

Take the three dimensions of narrative I sketched out here and here—story world, plot structure, and narration. For some of us (I include myself) genre-based narrative has creative, even experimental possibilities along all those dimensions. Crime fiction, including mystery and suspense tales, can become a laboratory for experiments with plot structure and narration. Connoisseurs of thrillers and detective stories know that they must read warily, for the author is often trying to deceive and mislead. My entries on Side Effects and Gone Girl afford some examples of the process.

Fantasy and science-fiction can experiment with plot and narration, as do Blade Runner and Source Code, but those genres are more typically straightforward along those dimensions. Historically, their core appeal has relied mostly on creating unique story worlds. A prime attraction of Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings is the sense of an alternative realm teeming with unique creatures moving among unknown territories. But creating a distinctive story world puts demands on the storyteller.

We have an indefinite number of default values that are in place as we encounter any narrative. For one thing, we assume that the world we encounter there will be almost entirely like our own. Unless we’re told otherwise, we’ll assume that Sherlock Holmes can bleed.

Narrative theorist Marie Laure-Ryan calls this the principle of minimal departure. With secondary world tales, we move toward maximal departure. When a narrative world diverges drastically from ours, as those in fantasy and science-fiction do, we need a lot more extra information—about how these robots are related to their masters, about why the dragon has been sleeping for so long, about why it always seems to be raining in Blade Runner’s Los Angeles. The storyteller, in his or her own voice or via character dialogue, must spell out these minutiae.

But not all of them. Inevitably there are some unfilled spaces. Something always is left untold. As a storyteller, you know that every character comes trailing a backstory that can be expanded or revised (maybe in a sequel). In addition, your world gains solidity if you hint about tales yet to be told, as Dr. Watson alludes to the still-unwritten case of the Giant Rat of Sumatra.

What the author leaves blank others can fill in. As the internet has shown dramatically, fans can take up the job of adding to secondary worlds. They can offer their own versions of adventures in the realms of Star Trek, LotR, and other fictions. True, nothing stops you or me from writing new adventures of Sam Spade or a sequel to Rebecca, but you probably won’t be enriching the characters’ milieus with fanciful creatures or gadgets or foliage, let alone entire planets.

Several big Hollywood franchises have embraced the idea of secondary worlds, but independent cinema largely has not. Indie films tend to be modest, realist exercises that tell their stories and stop there. Part of their raison d’etre is to be different from the fantasy and science-fiction epics blasted at us by the studios. So melodramas and thrillers, biopics and anecdotal character studies, don’t by and large traffic in parallel worlds. The sequel, a standard narrative unit for worldmaking fiction, is rare in indie cinema, and even then it tends to be of a realist tenor, such as Linklater’s Before/After series. When fantasy enters an indie film, as in Being John Malkovich or Beasts of the Southern Wild, it tends to consist of one adjustment of the principle of minimal departure, not a drastic overhaul of the story world.

Now we can get a better sense of the originality of Anderson. Moonrise Kingdom, like The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, Fantastic Mr. Fox, and The Grand Budapest Hotel, presents itself as a richly realized parallel world. The classic comedy plot of lovers opposed by parental authority plays out in a densely furnished alternative realm derived from our own, but with its own peculiar features.

The uses of reenchantment

My 2014 blog entry took this parallel-world project as a valid one and defended Moonrise Kingdom against charges of preciosity and twee. I suggested that the film had affinities with a tradition of fantasy going back to Lewis Carroll, James M. Barrie, and G. K. Chesterton. In the back of my mind I had longer-term influences as well, such as stories of Atlantis and of course Gulliver’s Travels.

Since then, I’ve read Michael Saler’s excellent 2012 book As If: Modern Enchantment and the Literary Prehistory of Virtual Reality. Saler argues that the impulse toward fictional worlds in contemporary mass media and video games back to various strands of literary culture in the nineteenth century. He traces the development of a new kind of fiction: fantasy worlds rendered with the detail pioneered by emerging realist schools of writing. Poe and Verne were early sources, but the “New Romance” launched by Stevenson with Treasure Island (1883) and H. Rider Haggard with She (1887) crystallized the idea of imaginary lands that could be filled out in unprecedented detail. Stevenson’s and Haggard’s successors realized that maps, footnotes, news stories, eyewitness correspondence, and illustrations of artifacts could give pure fantasy a sense of solid reality.

Since then, I’ve read Michael Saler’s excellent 2012 book As If: Modern Enchantment and the Literary Prehistory of Virtual Reality. Saler argues that the impulse toward fictional worlds in contemporary mass media and video games back to various strands of literary culture in the nineteenth century. He traces the development of a new kind of fiction: fantasy worlds rendered with the detail pioneered by emerging realist schools of writing. Poe and Verne were early sources, but the “New Romance” launched by Stevenson with Treasure Island (1883) and H. Rider Haggard with She (1887) crystallized the idea of imaginary lands that could be filled out in unprecedented detail. Stevenson’s and Haggard’s successors realized that maps, footnotes, news stories, eyewitness correspondence, and illustrations of artifacts could give pure fantasy a sense of solid reality.

Admirers of these romances, Saler suggests, cultivated a complex frame of mind. They knew at bottom that it was all fiction, but they also enjoyed the imaginative freedom of a new game. They conceived a world that was as tangible as ours but still harbored the power of magic.

The imaginative exercise might vary. For extreme fans of the Sherlock Holmes saga, the task was to pretend that Arthur Conan Doyle was simply Dr. Watson’s literary agent, and that Holmes, Watson, Moriarity, and all the rest were living humans. Watson’s records of Holmes’ achievements became a sort of documentary scripture that had to be scrutinized for what it hinted at or left out. For admirers of Tolkien, engagement involved acquainting oneself with the encyclopedic variety of cultures, creatures, folklore, languages, and landscapes of a truly parallel world. What Tolkien called the legendarium presented as daunting a mythology as any discovered by a real-world ethnographer.

The broad social function of this trend, Saler argues, was to reenchant modern life. From geology to biology, from astronomy to psychology, turn-of-the-century science had blown away many dogmas. The spirit world was shrinking. The modern task of turning mysteries into puzzles for the rational intellect had begun. The “as if” invitation of virtual worlds gave both creators and consumers a way to exercise their minds in freer ways. Writers and readers could cultivate what Saler calls “animistic reason,” a rational scrutiny of what was there, but one fueled by imagination. As he notes, even that paragon of logic, Sherlock Holmes, relies on intuition and insight.

From this standpoint, Moonrise Kingdom reveals itself as part of a richer tradition than I’d realized. Its parallel world still seems to me to radiate the fairy-tale qualities of Carroll, Chesterton, and company, given some absurd twists; but now I see the emphasis on documentation, all the maps and letters and lists, as owing something to the New Romance. The film is something like a scrap-album version of a story. At the same time, the wondrous qualities of Anderson’s tale—not least, Sam’s survival of a lightning bolt and the miraculous rescue of the couple by Captain Sharp—carry, at least for me, some of that reenchanting of the everyday world that Saler finds in this tradition. Above all, we learn, as always, that things we think are very modern turn out to be new variants on something that went before. In Moonrise Kingdom, Anderson updates a nineteenth-century version of magical realism.

How to make a world

In my earlier entry I talked about how the worldbuilding enterprise fits snugly into modern cinema’s demands for both authors and brands. Anderson’s typical strategies of style and storytelling set him apart from his peers artistically, but they also offer entry points for merchandising and fan appropriation. What’s especially likable is Anderson’s embrace of the DIY aesthetic, as both he and his fans practice it. Unlike Lucas, who polices amateur Star Wars tchotchkes, Anderson encourages his admirers to spin their own riffs on his work.

Yet worldmaking is more than franchise branding. Saler’s As If, a work of cultural history, doesn’t try to analyze the literary strategies of the individual works very much. I want to ask: What does this creative option commit storytellers to? And how does Moonrise handle the challenges?

Most basically, the storyteller has to teach us the rules, big or small, that govern the world. Is it a kingdom, a post-apocalypse wasteland, or a world at war? This process goes easier if the imaginary world is a model world, a sort of schema we can fill out because it fits into a general concept we already have. If this is a kingdom, as Alice’s Wonderland partly is, then we can grasp the presence of Kings, Queens, aristocrats, soldiers, and beheadings. If it’s a wasteland, we expect something more like a world of nomadic tribes, with the absence of law producing scavenging bands and violent clashes. If an alternate world embodies one or more conceptual schemes we already know, we can learn our way around this new one faster.

The source schemas needn’t of course be absolutely real, just conceptually familiar. So the kingdom of Alice’s Wonderland is partly defined by the iconography of chess and playing cards. Likewise, our knowledge may not be wholly historical. Blade Runner’s LA is 80s Tokyo gone grubbily high-tech, but it’s also derived from the iconography of film noir. An idea of civil war informs Game of Thrones, with its borrowings from various phases of European history, but it seems likely that viewers’ familiarity with board games and role-playing games also clarify the forces in contention. The showrunner David Benioff tagged Game of Thrones “The Sopranos in Middle-Earth,” and this suggests how different schemas, real or fictional, can cooperate to distinguish a model world.

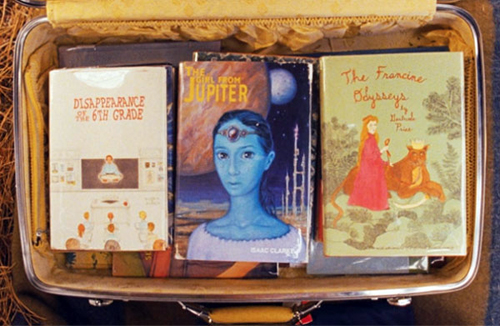

In Moonrise Kingdom, several schemas blend nicely to help us grasp the outlines and let the tweaks stand out. There’s the social situation of early adolescence, defined by family (or foster care, as in Sam’s case), schooling, and summer vacation. There’s the girl’s love of books with active heroines, a world counterposed against that of the boy scouts, with their ritualized adventures. Geographically, there’s the upper-coastal island that might be off Rhode Island, subject to tides and storms and inhabited by mostly upscale white folks. All these schemas and more are blended through the schema of “summer vacation,” a period where kids want to have adventures. Given our familiarity with these schemas, we can hook into a world of nerdish scout badges for Leaf Inspector and H2O Purifier, of slightly underscaled lighthouses, and a social worker named, by metonymy, Social Services.

An alterative world, by exaggerating a schema we already possess, can comment on the target world. Alice’s Wonderland satirizes the bloated capriciousness of the English aristocracy, and the Mad Max films suggest that increasing reliance on technology (i.e. oil-dependent machines) will paradoxically drive us backward to barbarism. In Moonrise Kingdom, probably most viewers would say that the summer in New Penzance provides a microcosm of the frustrations and disappointments of twelve-year-olds misunderstood by parents, teachers, guardians, peace officers, and other kids. By showing Sam bullied by other foster boys, as well as by the Khakis, I was reminded of my own stay in the Scouts. When the Scoutmaster’s back was turned, it all seemed merely a rehearsal for high-school thuggery.

Here’s another advantage. By mapping a schema we already know onto this new territory, we can appreciate not only the similarities but the novelties, the items that the storyteller has created to make this realm unique. In some cases, these novelties can be fairly narrowly focused. The Holmes saga emphasizes recurring characters and the furnishings and routines of the Baker Street household (keeping shag tobacco in a slipper, summoning the Irregulars). Beyond this perimeter, we are in more or less realistic 1890s London. Alternatively the infilling can be much greater, as with the imaginary landscapes and folkways of Middle-Earth. Here the creator earns esteem not only as a storyteller but as a sort of secular demiurge able, as the Romantics said, to echo the power of the Almighty. It’s easier to destroy a world than to make one.

Here’s another advantage. By mapping a schema we already know onto this new territory, we can appreciate not only the similarities but the novelties, the items that the storyteller has created to make this realm unique. In some cases, these novelties can be fairly narrowly focused. The Holmes saga emphasizes recurring characters and the furnishings and routines of the Baker Street household (keeping shag tobacco in a slipper, summoning the Irregulars). Beyond this perimeter, we are in more or less realistic 1890s London. Alternatively the infilling can be much greater, as with the imaginary landscapes and folkways of Middle-Earth. Here the creator earns esteem not only as a storyteller but as a sort of secular demiurge able, as the Romantics said, to echo the power of the Almighty. It’s easier to destroy a world than to make one.

Accordingly, much of the admiration fans feel for Anderson comes from the fact that it’s idiosyncrasy all the way down, from geography and architecture to books, games, toys, indicia, and the like. Other films give us fake locations, but he interpolates fake maps and a fake guide.

The pleasure is one of unnecessary abundance that suggests new stories. The detail that isn’t dwelt on—the kitty casually carried in a fishing creel or the needlepoint landscapes that preview the film’s locations—suggest that we could turn a corner and simply find more unpredictable stuff filling this world. What’s the story about One-Eye’s bandage? Anderson talks of wanting to suggest that the Bishop attic should entice us toward other narrativess:

I also had the idea that maybe the house could have the atmosphere of a rickety old place in some book where the kids go up into the attic and reach through a broken board and find a fragment of a forgotten map and set off on an adventure—that it could have that sort of feeling.

As with Doyle’s Giant Rat of Sumatra, there would always be more to find if we could probe this world more fully. The best Almighty is one that leaves some corners of creation to be imagined.

Imaginary gardens with imaginary toads in them

The overabundance of detail is open to the charge of fussiness and self-indulgence. Isn’t packing so much in just a matter of being cute? The infilling is particularly vulnerable because it often seems merely decorative. Details that affect the story action hardly count as details any more: the Ring in The Lord of the Rings is central to the action, while the Evermind flowers aren’t. Once we get beyond purely narrative functions, I think that the details of richly appointed worlds can fulfill at least five other purposes.

First, there’s realism. The doings on New Penzance and environs aren’t wholly cut off from the real world. The action is set in 1965, and the clothes, furniture, portable record player, and other furnishings match the period. To take one detail: the Françoise Hardy tune “Le temps de l’amour” anchors Suzy in a particular taste culture, that of American girls and women who took up yé-yé, Sylvie Vartan, and Salut les copains music rather than the Beatles or the Stones. American cinephiles are probably most familiar with this taste culture from Godard’s Masculin-feminin (1966).

It seems that an urge toward realism drives Anderson to build his micro-world. He speaks of creating all the props: “All these things just take forever, but I feel like even if they don’t get that much time [on screen], you kind of feel whether or not they’ve got the layers of the real thing in them.” It’s striking that he uses the same word that Ridley Scott did in calling Blade Runner‘s milieu a “seven-hundred-layer cake.”

Then there’s allusion. Details that are only minimally realistic can instead point outside the film. We’re familiar with more or less public movie allusions, as when a TV playing in a bar is running a film that comments on this one. Anderson seems not to have intended the title to be an allusion in this sense, it functions as one. It brings to mind Borzage’s Moonrise (1948), a hallucinatory noir centering on a backwoods manhunt for a less-than-guilty young man and the woman who loves him.

The name of Sam’s chief Scout tormentor, Redford, is more straightforward, as is the island called Penzance, which evokes the Gilbert and Sullivan operatic fantasy of blocked romance and also comic policemen.

One task for critics is to expose to our view the more hidden allusions, like the fact that the church on St. Jack Wood Island isn’t only a play on St. John’s Wood but refers to a favorite film of Anderson’s, Peter Bogdanovich’s Saint Jack (1979). Even if a viewer doesn’t know the allusion, she can suspect that any highlighted detail might like an Advent calendar window be hiding a citation.

The real mark of a richly realized world, as I’ve suggested, is a plethora of details that proliferate beyond the needs of realism and the temptations of allusion. So sheer density is another function. Moonrise Kingdom has to obey the principle of minimal departure, so perhaps the narrator is needed to explain the island’s geography. But in all the badges, books, and place names, the film supplies far more than the action requires. And such materials have been extended outside the film’s limits through the video extracts from Suzy’s books, the carefully printed collections of the Khaki buttons, and ephemera like those items collected in the Criterion package. Even the disc itself, with its little raccoon, is adapted to the story world. From this perspective, The Wes Anderson Collection, though a book, is exactly that: a gallery assembling items from the films’ distinct realms.

The real mark of a richly realized world, as I’ve suggested, is a plethora of details that proliferate beyond the needs of realism and the temptations of allusion. So sheer density is another function. Moonrise Kingdom has to obey the principle of minimal departure, so perhaps the narrator is needed to explain the island’s geography. But in all the badges, books, and place names, the film supplies far more than the action requires. And such materials have been extended outside the film’s limits through the video extracts from Suzy’s books, the carefully printed collections of the Khaki buttons, and ephemera like those items collected in the Criterion package. Even the disc itself, with its little raccoon, is adapted to the story world. From this perspective, The Wes Anderson Collection, though a book, is exactly that: a gallery assembling items from the films’ distinct realms.

Density for its own sake is part of the worldmaking project, but it accomplishes more. The effusion of such minutiae becomes an occasion for the filmmaker to display virtuosity, a zest for creating a consistent but unpredictable wash of detritus rivaling that in our world. Prodigality of invention, even when it gets a little obsessive, can be one mark of artistic quality. Joyce, Pynchon, Zola, Balzac, and other straining appetites invite us to appreciate how they’ve stuffed a wide canvas with minutiae.

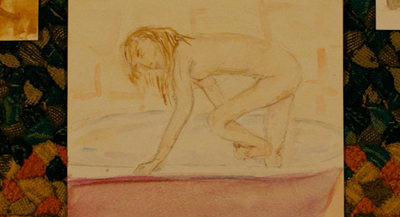

For a narrative to create a secondary world, then, we need a fair amount of sheer stuff. In Moonrise Kingdom Anderson highlights the stuff through unusual film techniques. Not content to let us simply register props in the distance or on the margins, he gives them prominence. In other films, the notes and maps and book passages that characters examine would be presented in a naturalistic way, clutched in hands or seen through optical POV. Instead Anderson simply thrusts these things at us, perfectly framed and lit, like items in a gallery display.

We shouldn’t forget a fourth function of all this detailing and infilling. Details need not point outward—toward a real world, or to other narratives, or to a New Penzance of the collective fan mind. Details can work very traditionally to bind the tale together. They can function as motifs.

My 2014 entry points out many of these, but this time I noticed the glimpse we get of Mrs. Bishop washing her hair during one of the gliding surveys of the house in the opening credits. That angling of her torso over the tub anticipates one of Sam’s drawings of Suzy we see after Mrs. Bishop finds the lovers’ correspondence.

Again, the picture isn’t in Mrs. Bishop’s hand as she shows it to the men; it’s mounted on the wall along its mates, ready for a DIY gallery show.

When I first noticed the flaming motif on the Khaki unit’s motorcycle and helmet, I thought it was associated with Redford’s petty meanness. It is, but it’s also part of the Khaki Scouts’ insignia, as we glimpse early on when a scout irons his kerchief, here in the lower left.

When Redford’s patrol attacks Sam and Suzy, Anderson cuts to one of those vitrine-display images but very abstract and flashed in alternate colors. The flash-frames conceal the action. The promise of a fight given in the symmetrical-flame logo is fulfilled, but it’s amplified by inclusion of Suzy’s weapon, the forbidding scissors. She turns the Scouts’ logo and the scissors’ brand (Lefty™) into her escutcheon.

Motifs can help the other functions. The Khaki Scouts’ branded images suggest a parallel to Boy Scouts regalia, but they also make the Penzance story world cohere as its own place. At the same time, the fiery iconography suggests the aggression that several of the boys are ready to let out at any time, and Anderson stresses that as a thematic motif through his nondiegetic inserts during the skirmish.

The fifth function, recidivism, is in a way the simplest of all. Just as we might rewatch a mystery film to see how we were misled, people can rewatch Moonrise Kingdom to seek out the sorts of felicitous touches we’ve been considering. A world saturated with details invites us to revisit it. That’s what happened with me.

Britten for boyhood

All these functions come together in one of Anderson’s most ingenious strokes, the use of the music of Benjamin Britten.

It’s an unexpected gesture of period realism from somebody of Anderson’s generation. In the 1960s classical concert music was central to intellectual culture in a way we can scarcely imagine today. Ives, Mahler, Satie, Shostakovich, and other masters were rediscovered, and avant-gardists like Varèse and Ligeti became familiar to a broad public. Imagine a time when filmmakers drew soundtracks from Penderecki (Kubrick) and Orff (Malick).

In this period, Britten achieved fame with LP recordings of his major operas, and he produced some indelible masterpieces. His War Requiem (1962, recorded 1963) became a best-selling album. The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, often paired with Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf, was recorded over a dozen times in the 1960s. The children’s pageant Noye’s Fludde (1958, recorded 1961) was designed for church performances of the sort we see in the movie (although probably few were as elaborate).

In this period, Britten achieved fame with LP recordings of his major operas, and he produced some indelible masterpieces. His War Requiem (1962, recorded 1963) became a best-selling album. The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, often paired with Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf, was recorded over a dozen times in the 1960s. The children’s pageant Noye’s Fludde (1958, recorded 1961) was designed for church performances of the sort we see in the movie (although probably few were as elaborate).

The Britten details amount to allusions too, both private and public. As a boy Anderson owned The Young Person’s Guide and with his brother sang in a performance of Noye’s Fludde. Just as important, if you had to pick a classical composer of the period who was centered on youth, it would have been Britten. Not only did he write a fair amount of music for young performers, but his later work drew ideas from pieces he wrote as a boy. The film includes a portion of one of these later recastings, the Simple Symphony of 1934. Set to Anderson’s images, the music evokes the brisk innocence of Sam and Suzy. So the allusions fit the subject and theme of the movie.

What about density? According to Anderson, Britten’s music permeates the movie. “The movie’s sort of set to it. . . . It is the color of the movie in a way.” Britten’s music isn’t incessant, but it is vividly presented in the story world during the big scene of Noye’s Fludde. Britten pieces are excerpted throughout the score as well. At the very end, the movie goes Britten-mad, first by playing the final fugue from The Young Person’s Guide (fulfilling the tease of the opening with Suzy’s brothers) and then, in the second part of the credits, applying Britten’s dissection of parts and choirs to Alexandre Desplat’s score.

The motivic uses of the Britten details are pretty evident. The Biblical flood in the church pageant predicts the film’s climax, and like the animals rescued two by two, Sam and Suzy will be saved. Less obvious is the motivic use of a lovely melancholy song from “Friday Afternoons,” one of several Britten pieces Anderson discovered while making the film.

In “Cuckoo,” a boy soloist and choir sings of the cuckoo’s waning stay: he comes in spring and flies away at summer’s end. We first hear the song during the low point of Sam’s fortunes. He has just been yanked away from Suzy and, as he is ferried back to camp, he’s told by Scoutmaster Ward that his foster parents have given him up.

The song’s text and plaintive melody evoke the end of the idyll and a bleak future for Sam.

But as we’ve seen, Sam and Suzy get reunited after the second cycle of escape/ chase/ capture. The song recurs in the epilogue as Sam, touching up his landscape painting, slips out of Suzy’s house to join Captain Sharp in the driveway.

At one point Sam has nothing; at the other he has everything. Now the song seems less a lament for a final fate than something less harsh: a lyrical envoi to a charmed summer that changed Sam’s life. The ineffectual father-figure Ward is replaced by the somewhat more competent Sharp, and Sam now has a future, with his mother’s pin worn discreetly alongside his Khaki honors. The cuckoo song gently enhances a scene that is at once an end and a beginning.

As for recidivism: Well, why not rewatch the movie listening for Britten’s music?

Henry Jenkins, a pioneering scholar of “participatory culture,” once pointed out a developing trend in recent popular media. Our creators seemed to have migrated from emphasis on the story (a singular chain of events, over and done with) to the character (a protagonist like Superman who can get involved in many stories), and now to the world (a realm in which many protagonists can interact, as in the Marvel Universe). Many fans want worlds they can redesign to suit their imaginations. But maybe we should sometimes leave those worlds intact.

I’m completely happy with tales that don’t proliferate across other platforms. I like characters who don’t carry the burden of multimedia backstories. But of course I’m open to worldmaking too. I’m especially open to it when an idea so identified with corporate branding and mass-production culture gets revamped by a temperament as unpredictable as Wes Anderson’s.

I’m as pleased as anybody when a swaggering space warrior lip-syncs “Come and Get Your Love” while using an alien lizard as a hand mike in Guardians of the Galaxy. Yet I’m even more appreciative when somebody finds a way to weave yé-yé and Benjamin Britten into an enclosed world I could never have imagined, and cannot improve. In place of the big worlds of Narnia, Middle-earth, the Marvel Universe and other macrocosms, New Penzance seems the right size for shades of ironic, tender feeling. Why should I want to rewrite this world? It’s enough to discover it, and explore it.

Thanks to Kristin and Brendan Colvin for good advice.

In the small-world spirit, Criterion offers close looks at some Khaki gear.

What do we call these relatively self-contained realms? I’ve used several terms. Tolkien may have helped the idea coalesce by coining the label “secondary world” in his essay “On Fairy-Stories”:

What really happens is that the story-maker proves a successful “sub-creator”. He makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is “true”: it accords with the laws of that world. You therefore believe it, while you are, as it were, inside. The moment disbelief arises, the spell is broken; the magic, or rather art, has failed. You are then out in the Primary World again, looking at the little abortive Secondary World from outside.

Most of my information about Anderson’s creative process, including his interest in Britten, comes from Matt Zoller Seitz’s book-length interview The Wes Anderson Collection, particularly pp. 313-317. Anderson’s remark about the Bishop attic is on p. 300.

Marie-Laure Ryan discusses the principle of minimal departure in several publications, most fully in Chapter 3 of Possible Worlds, Artificial Intelligence, and Narrative Theory (Indiana University Press, 1991). An earlier and less technical version appeared in 1980.

Derek Jarman was inspired by Benjamin Britten’s music too; Jarman’s War Requiem (1985) is a sort of Wagnerian music video accompanying the original recording. It’s available for streaming, rental, and purchase here.

See Henry Jenkins’ Convergence Culture:Where Old and New Media Collide for more on popular-culture worldmaking. Henry blogs, indefatigably, at Confessions of an Aca-Fan.

George Lucas’s remarks about details and Ridley Scott’s about layers come from The Way Hollywood Tells It, pp. 58-60. Those pages discuss the trend toward worldmaking in mainstream Hollywood.

P. S. 5 November 2015: We have had some inquiries about whether the eleventh edition will be available for course use during the spring 2016 semester. McGraw-Hill’s intention was to introduce the new edition during the spring semester, for adoption for the fall, 2016 semester. Our editor, however, tells us that there are options for teachers who want to be early adopters and use the book in the spring.

Use of the print version for spring would be a tight squeeze unless your semester starts late in January. McGraw-Hills aims to have the SmartBook (i.e., the online ebook version) live on January 15th, the same date as the books should be on their way from the printer to the warehouse. It might take some time for books to ship once they get to the warehouse, so our editor recommends the SmartBook as the safest option for spring use. Early adoption assumes that instructors do not have lots of lecture PowerPoints and tests to update.

Usually, if the instructor works with the local MHE sales representative, the publisher can figure something out. If you are interested in being an early adopter, you should get in touch with your rep. If you don’t know who that is, you can find contact information here.]

Pixels into print: The unexpected virtues of long-winded blogging

Penance (2013).

DB here:

Remember Web 1.0, when blogs were really logs? You know, diary-like accounts of events befalling the writer? The sense that every instant of one’s life needs preserving and broadcasting got absorbed into Facebook and Twitter and Instagram, I suppose. Today blogs are more likely to feature essayistic thinking. People slow-cook their blogs more, it seems to me, and they write in a reflective mode. Since our blog has always been, um, expansive in such ways, I welcome the Ruminative Turn.

Like most academics, we write long for a reason. You need more words to dig into a question. That’s why books exist. But mid-range is good too. The blog format suits specualtive, exploratory work and informal prose that wouldn’t show up in a journal. In this para-academic register, the aim is to spread ideas and information around. A reviewer of the book I mention below puts it well: “democratic, attainable erudition.”

Because we write long, and maybe because we’re a bit chatty, a few of our entries have become published, suitably spruced up, as “real” articles for diverse audiences. Some overseas journals, both print and online, have published translations of pieces available here. Thanks to the good offices of the University of Chicago Press, a gaggle of our entries became a book, Minding Movies. Lately, three of our blogs have wriggled their way into paper—two as DVD liner notes, and a third in an imposing rectangular solid that is sort of a mega-book. All are aimed beyond the academy.

Doing Penance

Two summers ago our friend Gabrielle Claes tipped me to a visit by Kurosawa Kiyoshi, accompanying a screening of his Penance (Shokuzai) at the Brussels arthouse Cinéma Vendôme. Of course we went, and we had a good time with the film and the Q & A that followed. I duly wrote it up, did a bit of quick analysis, and offered it to the world online.

When the Doppelgänger branch of Music Box Films decided they wanted to distribute Penance on DVD, they asked for the essay. The it’s come out in a good edition (alongside Eddie the Sleepwalking Cannibal, worth a look, and other genre fare). My essay is preceded by one by Tom Mes of Midnight Eye, who discusses the film’s relation to its source novel and pinpoints its exploration of “the gray area between the mundane and the ghastly.” there’s also an informative interview with Kurosawa.

As a five-part TV series, Penance fits its plot to the installments pretty rigorously. A little girl is assaulted and murdered, and only her four playmates have seen the killer. Taking advantage of the serial structure, Kurosawa begins each episode by revisiting the original crime, picking details relevant to what we’ll see but expanding the sequence a bit by tracing each girl’s efforts to notify the community. It’s a sophisticated version of the “Previously on [name of series]” recaps we commonly get in TV serials.

After revisiting the killing and showing the aftermath as it affects each girl, every installment shows the children gathering for a grim birthday party. On that occasion Emiri’s mother Asako demands that the girls either find the killer or do penance for their lack of vigilance.

After this juncture, each of the first four installments attaches the narration to one girl’s viewpoint fifteen years later. The episodes trace the awful effects of the crime on the girls’ personalities and their adult lives. Each one gets involved with an unstable man, with catastrophic consequences. In each episode, Asako reappears at a critical moment to demand penance or to absolve the woman. The fifth episode centers on Asako herself: her immediate reaction to her daughter’s death, her search for the killer, and her realization that the crime has roots in her own past.

I was happy to get a chance to see Penance again, because it’s continually engrossing and quite moving. It also exemplifies the sort of clean, classical genre filmmaking that doesn’t get done in America very much. After watching all the GPS views and whooshes down to street level and nonstop bludgeoning supplied by Run All Night (still, an okay movie), it’s a pleasure to turn to a film that builds its tension through a fixed camera, calm clarity, and performances suggesting suppressed menace rather than explosive confrontations–though there are a few of those too.

Penance would be something for young filmmakers to study. It shows how locations can be used elegantly and economically, and how the inability to get extreme long shots in cramped quarters can actually be an advantage. Classrooms, offices, and gymnasiums are used with a sober restraint, each one given defining geometry and color scheme. A crucial confession takes place in a police station being renovated, and Kurosawa lets the scene unfold in a way that continually reveals surprising bits of space, such as a cop standing somewhat ominously at a distance. He’s unafraid of holding long shots because the shot is propelled by the drama, not the cutting pace. Here’s another example that illustrates the Monroe Stahr rules of storytelling: not a car chase or gun battle, but a quietly puzzling situation that evokes curiosity and suspense.

Asako has gone to a drawer and withdrawn a ring. We’ve not seen it before and have no idea what it signifies.

She crosses the room, as if to do something with it. Before we find out, cut to her husband in the hallway. This cut initiates a take lasting over three minutes.

When he reaches the doorway he catches her hurling it angrily into the wastebasket. So now we know he knows…but what?

Reminding her that she’s treasured this since college, he fetches it out for her and quietly leaves.

As she starts to explain, she follows him into the corridor. The camera pans right to reframe their new confrontation.

There she reveals her secret, slowly. As she crumples to the floor, Kurosawa permits himself a camera bobble–a rarity in a film that almost entirely avoids handheld camerawork. The husband at first consoles her…

…but then she confesses her secret. He pulls away from her.

She tries to embrace him, looking for solace, but he shuts her out and withdraws.

She’s left to fall to the floor crying in shame, in that classic attitude of distraught Japenese women.

The highest pitch of the drama–Asako’s revelations–has been given a close view, but the action has led up to it and away from it through character blocking, not cutting. The situation unrolls and builds tension completely through dialogue, body language, and facial reaction. But it could hardly be considered theatrical, because the camera has judiciously strengthened certain parts, concealed others, and obliged us to shift character perspective (Asako-husband-Asako) through slight changes of position. And playing so much of the scene in distant and dorsal shots harks back, inevitably, to Mizoguchi.

As I mentioned in the early entry and the liner notes, Kurosawa always knows where to put the camera–no small accomplishment these days–and there’s as much power in this apparently simple scene as in any of the grandiose Steadicam movements in more inflated films. Trust the audience to sense the undercurrents, and they will follow you if you have mastered calm, precise cinematic storytelling.

Grand hotellerie

The Doppelgänger gang released Penance on DVD last November. I’m only a little less late in mentioning the arrival of Matt Zoller Seitz’s newest addition to The Wes Anderson Collection: The Grand Budapest Hotel. The decision to base a big, luscious book on a single Anderson film gives this ambitious picture even deeper treatment than we saw in the Collection’s individual chapters. From Seitz’s rich opening appreciation to the amiable list of contributors (The Society of Crossed Pens), the book is a serious divertissement, a wonder-cabinet of images, ideas, and semi-childish fun.

It’s partly a making-of book. We get production stills, script pages, set designs, storyboards, animatics, special-effects secrets, costume designs, and the now-celebrated photochrom images. Seitz has larded his captions with shrewd critical points about lenses, compositions, lighting, and staging—not the normal gee-whiz commentary of an “authorized” making-of. Anderson’s enjoyment of practical effects, his judicious use of digital tools, and his most complex voice-over narration yet come through vividly.

Seitz is especially interested in the history and artistic models behind the movie. His interviews are crowded with information about Anderson’s inspirations, which seem endless. Of course there is Stefan Zweig, who is given several pages of intense discussion. We also learn of Anderson’s interest in the exiled directors like Lubitsch and Wilder, who gave us both a Europeanized Hollywood and a Hollywoodized Europe. There are homages to The Red Shoes and Colonel Blimp and Letter from an Unknown Woman. Anderson was equally committed to a broader historical context, passing his story through different eras—the bell-jar atmosphere before the Great War, the premonitions of World War II (itself never shown), and the postwar emergence of Communism, seen in the revamped and decaying Hotel in the 1960s. Seitz has even spotted borrowings from James Bond movies. As skillful an interviewer as he is graceful an essayist, Seitz induces Anderson to reveal the density of this sweet, sinister movie—the cinematic equivalent of Chandler’s line about a tarantula on a slice of angelfood cake.

There are as well interviews with Ralph Fiennes talking of the “farce spectrum,” costume designer Milen Canonero ordering up a Prada leather coat for Willem Dafoe, the very great composer Alexandre Desplat explaining his compositional procedures, production designer (and Milwaukee native) Adam Stockhausen discussing the magnificent settings, and DP Robert Yeoman talking about shooting on 35mm.

There are as well interviews with Ralph Fiennes talking of the “farce spectrum,” costume designer Milen Canonero ordering up a Prada leather coat for Willem Dafoe, the very great composer Alexandre Desplat explaining his compositional procedures, production designer (and Milwaukee native) Adam Stockhausen discussing the magnificent settings, and DP Robert Yeoman talking about shooting on 35mm.

Anderson’s fussbudget aesthetic meets its match in a book crammed with fastidious minutiae. Whimsy, as Lewis Carroll and G. K. Chesterton understood, escapes coyness only when it’s pursued rigorously. Seitz reviews the careers of the major players in postage-stamp pasteups. When Anderson is revealed as a connoisseur of frame stories, flashbacks, and other fancy techniques we favor on this site, Seitz provides a four-page spread of pick hits of voice-over. Max Dalton, the illustrator, gets the message. With their modestly lowered eyes and sidelong grins, his neo-New Yorker figures swarm these pages but assemble, obediently rank and file, in the end papers.

Most surprising of all for a production dossier, in-depth criticism is not only allowed in the tent but given its turn in the spotlight. Christopher Laverty analyzes the costumes with a precision seldom seen in academic writing, while Olivia Collette contributes an enlightening study of Desplat’s score. Steven Boone examines the art direction, with a special sensitivity to how set designs are fitted to anamorphic optics. Ali Arikan brings his characteristic lucidity to a study of Zweig’s Vienna and the traces it leaves on his fiction and Anderson’s film. The essays show that analytical film books, like volumes of academic art history, can be merit high production values.

My contribution, a revamping and nuancing of an earlier blog entry, looks at how Anderson adjusts his planimetric staging and shooting to different aspect ratios. For me, this assignment was the big time. No academic book, my usual publishing platform, could have illustrate my ideas so splendidly. I’m proud to be among fine company, and I like the fact that people are reading and buying the thing.

Of course very few film books have the built-in audience of a Wes Anderson project. As I wrote last summer, he brings his brand with him. But that isn’t, I think, a bad thing when the results are as lively and lovely as The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Last year I had to go to Hong Kong the weekend the film opened. I dashed to it during my first day in town, then squeezed in two more screenings during the festival. Now, after a year and many more viewings, it hasn’t cracked yet. At the moment I think of it in relation to the “hotel” books and movies of the 1920s and 1930s. I think of its predecessors, such as Arnold Bennett’s 1902 novel The Grand Babylon Hotel. (Did Anderson read it? I don’t find a mention here.) I remember those star-filled ensemble comedies of the 1960s like The Pink Panther and The Great Race, twitching with celebrity walk-ons and the cartoonish effects Anderson relishes. In short, I think about film history, and it pleases me when a film and its book trace out, in dazzling detail, an exceptional movie’s debts to tradition. Keep your Birdman and Gone Girl and Jersey Sniper (or is it American Boys?): This is the 2014 American film that will be remembered for decades.

Hello again, my language

Last year’s other big film for the future is, no doubt now, Adieu au Langage, just coming out on Blu-ray as Goodbye to Language from Kino Lorber. I’ve said my say about this item twice (here and here) so about all I have to add is that after several more viewings, I’m still convinced of its excellence. Kino Lorber gives us two versions, the 3D one and the “merged” 2D one. The 2D one is still one hell of a film, but of course in 3D it’s spectacular.

The disc includes an essay developed beyond my blog entries. It says some new things, but it’s inevitably incomplete. Godard’s films so teem with ideas (both intellectual and cinematic) that there’s almost always more to notice. “One can put everything in a film,” he remarked back in the 1960s. “One must put everything in a film.” He sort of does, especially here.

Both versions belong on every cinephile’s shelf. If I didn’t already have a 3D TV (purchased so I could watch Dial M for Murder and Gravity properly, and even freeze the frame), I’d get one so I could see Farewell to Language whenever I wanted. Consider your options. 3D TV is now dead enough to be cool.

Thanks to Austin Vitt of Music Box films for picking up Penance, and Richard Lorber and Robert Sweeney for recruiting me for the Godard disc. I’m indebted to Matt Zoller Seitz for bringing me on board the Anderson project, and to Caitlin Robinson of Twentieth Century Fox for loaning me a print of The Grand Budapest Hotel so that I could study its aspect ratios in their natural habitat.

Midnight Eye features Kohei Usuda’s very detailed review of Kurosawa’s latest project, an entry in the “idol movie” genre. You can find MZS’s video introducing the Grand Budapest book here.

Goodbye to Language.

The sirens’ song for Oscar

The Lego Movie.

Another guest blog this week, this time from Jeff Smith, our colleague in the department here at UW–Madison. Jeff is one of America’s experts on movie music and sound technology. He contributed an entry on Atmos last year. He has written many articles on film sound, along with two books: The Sounds of Commerce and Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. He’s also our collaborator on the eleventh edition of Film Art: An Introduction.

‘Tis the season for Oscar buzz, and the media glut of award prognostications is already upon us. Most of the attention will go to the above-the-line talent who’ve received nominations (actors, directors, and screenwriters). The craft categories tend to get much less scrutiny, but the work of cinematographers, editors, and composers plays an equally important role in making their films award-worthy.

Today I offer some observations about this year’s nominees in the music categories: Best Original Score and Best Original Song. By using the nominees as examples, I hope to illuminate some of the ways that music continues to contribute to cinema’s narrative functions and its emotional impact on viewers. I’ll also offer my predictions for who will win at the end of each section.

Best Original Score

Even before this year’s nominees were announced, one of 2014’s most distinctive and innovative film scores was declared ineligible by the Academy. Antonio Sanchez’s driving percussion score for Birdman was disqualified under Rule 15, which states that scores “diluted by the use of tracked themes or other pre-existing music, diminished in impact by the predominant use of songs, or assembled from the music of more than one composer shall not be eligible.” Apparently, in the view of the Academy’s music branch, Birdman’s use of substantial excerpts of concert music by Mahler, Tchaikovsky, Ravel, and John Adams weakened the impact of Sanchez’s score. That explanation, though, probably doesn’t pass the eyeball (or eardrum) test of anyone who has seen Alejandro González Iñárritu’s film. Sanchez’s drum work adds verve and energy to several of the director’s elaborately choreographed (and seamlessly stitched together) long takes.

Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’s electronic score for Gone Girl was also a notable snub, especially since their bold, pathfinding music for The Social Network took home the top prize just four years ago. The fact that both of these scores failed to secure nominations may be a sign that the Academy’s music branch is returning to the verities of good old-fashioned melody and harmony as the basic tools in the composer’s kit.

That being said, the absence of Sanchez, Reznor, and Ross from the list of nominees doesn’t mean that the remaining scores are dull or unadventurous. Quite the contrary. Several of them push film composition in new and exciting directions. Their scores fulfill traditional functions but employ innovative scoring techniques and orchestrations.

Old sounds, new sounds

Take, for instance, Gary Yershon’s score for Mike Leigh’s biopic, Mr. Turner. Bypassing the conventions of orchestral writing for film, Yershon composed for a chamber-sized ensemble. Some cues combine a saxophone quartet with a string quintet, a musical choice that seems deliberately anachronistic. (As Yerson himself says in the soundtrack’s liner notes, Adolph Saxe’s invention wasn’t even patented until 1846, just a few years before Turner’s death.) Other cues add flute, clarinet, harp, tuba, or timpani to the mix. But these embellishments simply add color to the basic sound of Yershon’s twin string and saxophone ensembles.

Yershon says he was attracted to the saxophone due to its ability to glissando – that is, bend pitch from one note to another. Yershon certainly exploits this element of the instrument’s sound by building his melodies from long sustained notes that slowly take on serpentine shapes. Saxophone glissandi have an almost iconic function in the idioms of jazz and pop music . (Think of the opening phrase of Wham’s “Careless Whisper.”) In this case, though, the technique gives Yershon’s score a minimalist, modernist edge.

Yershon’s inclusion of a saxophone quartet departs from two norms: the period music of Turner’s time and the symphonic orchestrations that have characterized biopics for decades. The saxophone was never a major component of the Hollywood sound crafted during the studio era. Composers like Max Steiner and Victor Young occasionally included saxophones in their arrangements of music played onscreen by dance bands, but for the most part, their wind arrangements were for some combination of flutes, oboe, English horn, clarinets, and bassoons.

Is Yershon’s score inappropriate on historical grounds? I don’t think so. By modernizing the sound of Leigh’s period biopic, Yershon’s score adds a contemporary resonance, perhaps encouraging viewers to see parallels between Turner’s painting and the work of modern-day artists. Indeed, as Guy Lodge noted in his Hitfix review of the film, “It’s tempting, even, to view the film as biopic-as-self-portrait, revealing shades of one life through another. Leigh has a reputation for prickliness and resistance to self-explication; perhaps it’s not surprising that he’s long been fascinated by Turner’s allegedly gruff, taciturn genius.”

Yershon’s use of contemporary instruments may not in itself suggest those historical parallels. Indeed, most viewers probably have no idea when the saxophone was invented. But it certainly invites us to think about Leigh and Yershon’s reasons for opting for such a modern sound. And with its smaller instrumental forces, Yershon’s score resists some of the sweeping emotionalism that is found in other examples of the genre.

Zimmer pulls out all the stops

Hans Zimmer’s nomination for Interstellar is the tenth of his long and distinguished career. With all apologies to John Williams, Zimmer is arguably Hollywood’s leading film composer and his work is emblematic of a larger industry turn toward emphasizing musical tone and texture rather than big memorable themes. Zimmer’s score for Interstellar is no exception to this rule. In this case, though, much of the tone and texture is provided by the four-manual Harrison & Harrison pipe organ found in London’s Temple Church.

Director Christopher Nolan says that he liked the sound of the church organ as something that added an element of religiosity to Interstellar. But the organ contributes other things as well. For one thing, the organ’s booming bass register adds mass and heft not only to the music, but also to the astronomical bodies shown onscreen. The sheer size of these lower frequencies enhances the sense of scale in Nolan’s imagery. Thanks to the organ’s huge pitch range, the instrument’s upper register provides the quieter, swirling arpeggios needed to suggest the story’s filial bonds between father and daughter. At the same time, the instrument’s big, fat bottom end adds the musical bombast needed to convey the film’s epic visions of distant planets, wormholes, and alternate dimensions.

More important, despite the church organ’s strong association with sacred and liturgical music, Zimmer’s score never sounds like a Bach toccata. Rather, due to its repetitive, but intricate arpeggiations and simple, but affecting harmonic structures, Interstellar’s music has the kind of trippy, drone-ish, psychedelic feel that suggests both Terry Riley and Iron Butterfly. Zimmer’s score does not contain anything that is an obvious quote from the music of Stanley Kubrick’s “thinking man’s” sci-fi classic, 2001: A Space Odyssey. Yet, in its own way, Zimmer’s music recalls the period where such films were being produced, indeed the very kind of film that Nolan self-consciously tried to recreate.

In developing the score for Interstellar, Nolan and Zimmer also departed from the norms for director-composer collaborations. Most composers begin their work at a fairly late stage in the filmmaking process. In some cases, they may work from a completed script. In most cases, though, a composer starts with a rough cut of the film, making his or her contribution felt only during post-production.

In contrast, Nolan acknowledged that he has gradually been bringing Zimmer into his production at earlier and earlier stages. Nolan dislikes the practice of temp tracking, a technique that involves slugging in preexisting music that temporarily serves as a guide to the production team during the editing process. Says Nolan, “To me music has to be a fundamental ingredient, not a condiment to be sprinkled onto the finished meal.”

For Interstellar, Nolan asked to meet with Zimmer well before production began. As Nolan recounts in the liner notes to the soundtrack, he gave the composer an envelope containing a one-page summary of the fable that sat at the heart of the story. The description did not contain any details of the film’s genre or plot. Rather the summary simply laid out the narrative’s emotional core. Zimmer then took the summary and retired to his studio to start composing. Several hours later, Zimmer brought back a CD that contained about three or four minutes of music. Nolan listened to the new piece: a simple piano melody that nonetheless captured the feeling of what the director says he was “already struggling with on the page.”

When Nolan began shooting, he frequently listened to Zimmer’s simple piano piece, which functioned as a kind of “emotional anchor” for the film. Eventually, Zimmer returned to the studio and created the huge musical canvas that captures Interstellar’s heady exploration of space and time. Underneath it all, though, is the humble melody Zimmer wrote prior to production, the modest edifice upon which the rest of the score is built.

More songs about buildings and food service

Like Zimmer, Alexandre Desplat has several previous nominations to his credit, including those for the scores of Best Picture winners The King’s Speech and Argo. Unlike Zimmer, though, Desplat has yet to win. Among Hollywood’s current A-list composers, Desplat has shown extraordinary versatility. He’s at home writing for foreign art films, American indies, animation, and studio genre pictures. Desplat’s score for Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel is the third he has done for the director, following earlier collaborations on The Fantastic Mr. Fox and Moonrise Kingdom.

Here again, Desplat’s score for The Grand Budapest Hotel departs from established norms of Hollywood orchestration. Although he uses a slightly smaller version of the wind and brass sections usually found in older Hollywood film scores, he avoids the normal violins, violas and cellos. Instead he opts for a string section comprised of balalaikas, cimbaloms, zithers, mandolin, and acoustic guitar. This choice is intended to reflect the vaguely Mitteleuropean setting of the film. Just as the story is loosely inspired by the writings of Austrian novelist Stefan Zweig, the music reflects the social and geographical milieu of Zweig and his characters during the 1920s and 1930s. Eastern European and Russian folk melodies inspired much of Desplat’s. This combination of instrumentation and idiom creates a harmonic and timbral palette that proves to be enormously flexible in the composer’s hands, enabling him to add classical, modern, and jazz touches wherever they are needed.

Although Desplat employs unusual orchestration in The Grand Budapest Hotel, his score is fairly traditional in other ways. There are leitmotifs for several of the main characters, such as M. Gustave, Zero, Madame D., and Ludwig. An eight-measure theme is also linked to situations of adventure or danger. These themes and motifs tighten up the film’s structure. Such cues for patterning are particularly important when one considers The Grand Budapest Hotel’s “Chinese box” or “Russian doll” narrative construction, which nests stories inside stories.

Desplat’s score also captures the film’s dark yet whimsical tone. In interviews, the composer acknowledges that Bernard Herrmann and Carl Stalling were important influences on his work. At first blush, Herrmann, who composed several iconic scores for Alfred Hitchcock, and Stalling, who wrote crazy, almost manic music for Disney and Warner Bros. cartoons, would seem to occupy opposite corners of the universe. It’s to Desplat’s credit, though, that he is able to blend these diverse influences in a manner that is perfectly attuned to Wes Anderson’s imaginary “snow-globe” world. Indeed, the cue for the scene where Gustave is hanging from a cliff features harmony that would not be out place in Herrmann’s score for North by Northwest, an obvious inspiration.

But the mood is much lighter and airier in Anderson’s cliffhanger, partly because of the tenor established by Desplat’s music.

Scoring the Beautiful Minds of Cambridge

Ironically, Desplat’s chief competition may come from himself. Besides The Grand Budapest Hotel, Desplat also received a nomination for the fact-based espionage thriller, The Imitation Game. It was the fourth time in the last fifteen years that a single composer received two Oscar nominations for Best Original Score. And like the other nominees discussed here, Desplat developed an unusual compositional technique for the film, allowing for an element of randomness to determine his score’s final musical shape.

Whereas Sanchez deviated from compositional norms by improvising beats for Birdman, Desplat’s score for The Imitation Game pushes the envelope by featuring three computerized pianos, which sometimes play random patterns of preprogrammed music. According to the composer, the pianos’ fast, complex combinations not only underscore the urgency of the Bletchley Park team’s search for a solution to the Nazis’ Enigma code, but they also function as an musical correlative of cryptanalyst Alan Turing’s thought processes. As director Morton Tyldum put it, he wanted the music to seem subjective, as though it was conveying the mental operations inside the head of an awkward, but brilliant mathematician.

Desplat’s use of rapid scales and arpeggios to represent Turing’s genius actually recalls Philip Glass’ score for Errol Morris’s documentary about Cambridge physicist Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time. To be fair, Glass’ compositional style has employed these kinds of musical textures in many other types of cinematic contexts. Glass’s work not only appears in other Morris films, but also in biopics about Japanese writer Yukio Mishima and the Dalai Lama, and even in horror films and dramas, such as Candyman and The Hours. Given the constancy of his compositional proclivities, it is perhaps easy to make too much of Glass’s ability to depict the depth and brilliance of Hawking’s intellect. Yet there is little question that Glass’s music adds both a sense of mystery and majesty to Morris’s imagery, which itself explores such imponderables as the nature of time and the origins of the universe.

Because of this precedent, it is perhaps doubly striking that composer Johann Johannson took such a different tack in his music for the Hawking biopic, The Theory of Everything. With long sustained string lines and simple piano melodies, Johannson aims for a soft lyricism that is intended to add both pathos and subdued passion to the film’s depiction of Hawking’s relationship with his wife Jane. Since the film is based on Jane’s account of their marriage, it is probably not surprising that Johannson’s score plays her point of view even more than it does that of its putative subject. As the composer explains, the “heart of the film is the love story: Stephen and Jane, Jane and Jonathan. That’s really what the music needed to capture.” Thanks to Johannson’s use of harpsichord, celeste, harp, and guitar, the tone colors of the music remain light, making his score for The Theory of Everything a modern counterpart to the work of the Georges Delerue.

Prediction

All five nominees are quite worthy of the award for Best Original Score. But, if I had the opportunity vote, I would probably cast it for The Grand Budapest Hotel. Not only is Desplat’s score perfectly attuned to Wes Anderson’s distinctive style, but it would be nice to see the composer recognized for the overall quality of his oeuvre. Desplat’s fans, though, probably split their votes between The Grand Budapest Hotel and The Imitation Game, thereby increasing the chances that he’ll once again go home empty-handed.

In underlining The Theory of Everything’s romance plotline, Johansson’s score is perhaps the most traditional among the five nominees. I don’t believe, though, that its adherence to longstanding film score conventions will hurt it on Oscar night. Johansson’s sweet lyricism already carried the day at the Golden Globes, an award that has correctly predicted the eventual Oscar winner four out of the last five years. Although there could be an upset in this category, I expect we’ll see Johannson triumphantly hoist the little gold man over his head come Sunday night.

Best Original Song

If recent award ceremonies are any indication, this is a category that has fallen a bit on hard times. At least this year, there are five legitimate nominees. Last year one of the nominees was disqualified, and in 2012 and 2011, the category fielded only two and four nominees respectively.

One potential reason for the paucity of original songs may be the previously mentioned turn toward tone and texture in contemporary scoring practice. In the old days, many of the best-remembered and best-loved songs from the movies were crafted from themes specifically composed for the score. This was the case with tunes like Alfred Newman and Frank Loesser’s “Moon of Manakoora” from The Hurricane, Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer’s “Days of Wine and Roses,” or even James Horner and Will Jennings’s “My Heart Will Go On” from Titanic. Since current film composers are turning away from big themes, it seems there is less opportunity to adapt a musical motif into something that works as a theme song. (Of course, there are occasional exceptions. In 2013, Adele and Paul Epworth took home the Oscar for Skyfall, updating the established formula for making Bond theme songs.)

This year’s nominees also lack anything resembling last year’s heavyweight battle between Frozen’s “Let It Go” and Despicable Me 2’s “Happy.” All of the nominees seem quite worthy. None of them, though, has created the kind of cultural ubiquity enjoyed by Idina Menzel’s and Pharrell Williams’s chart-topping singles.

Two of the nominees have the misfortune of appearing in little seen films: Beyond the Lights and Glen Campbell: I’m Not Me. Diane Warren is one of the industry’s top songwriters and her “Grateful” is featured in the former of the two films. Warren also is a seven-time Oscar nominee, and although I believe her time at the podium will eventually come, it seems unlikely this year. Glen Campbell and Julian Raymond’s “I’m Not Gonna Miss You” is a moving ballad, made all the more poignant due to the singer’s ongoing struggles with Alzheimer’s disease. Campbell’s battle, which is the subject of James Keach’s documentary about the singer’s farewell tour, makes the song a counterpart to other epitaph numbers, such as Johnny Cash’s cover of “Hurt” or Warren Zevon’s “Keep Me in Your Heart.”

The third nominee is “Lost Stars” from Begin Again, director John Carney’s belated follow-up to his earlier indie sleeper, Once. “Lost Stars” was written by two members of the nineties band the New Radicals: Gregg Alexander and Danielle Brisebois. The latter has come a long way since her days as a seventies child star appearing in Broadway’s Annie and television’s All in the Family. Starting in the 1990s, Brisebois remade herself as a successful songwriter and producer, penning tracks for Donna Summer, Natasha Bedingfield, Kelly Clarkson, and a host of other top female performers.

“Lost Stars” is heard several times in Begin Again. The first time Gretta (Keira Knightley) performs it in a spare singer-songwriter arrangement featuring acoustic guitar, piano, and strings. It underscores a flashback of Gretta’s arrival in New York with her skeezy rock-star boyfriend Dave (Maroon 5’s Adam Levine). Later, we hear it as a track on Dave’s CD. Here he gives it an up-tempo stadium-pop sheen. Near the film’s end Dave again performs “Lost Stars,” this time as an arena-rock power ballad.

It is unusual to hear an Oscar-nominated song played in such wildly different styles, and even more unusual for one of those versions to be served up in a manner intended to seem excessive and distasteful. Tellingly, the end credits list Dave’s rendering of the song on CD as “Lost Stars (Overproduced Version).” The contrast between them, though, provides important character motivation for the film’s resolution. Dave’s indifference to Gretta’s creative vision of the song shows that he is ill suited to be her romantic partner. It also reveals producer Dan as a much more kindred spirit for Gretta’s professional ambitions. She gets to keep her coffeehouse, folkie purity even as her coffers are filled by the filthy lucre earned from sales of the soulless version featured on Dave’s major-label CD.

Interestingly, on Oscar night, Adam Levine will sing “Lost Stars” as part of the broadcast. If the producers wanted to stay true to the spirit of “Begin Again,” they might have opted for Keira Knightley to perform the song. Yet the fact that Levine was the first performer announced suggests that his star power was simply too much of a draw. Despite the film’s critical view of Dave’s talent, sales of Levine’s version of the song appear to have outpaced Knightley’s. Begin Again may be cynical about the music’s industry’s overinvestment in mainstream tastes, but Levine’s “overproduced” version of “Lost Stars” has done a great deal to give the film much-needed media exposure.

The fourth nominee, The LEGO Movie’s “Everything is Awesome!!!”, arguably displays an even more mind-bending degree of complexity in its relation to the popular music marketplace. The song appears quite early on in the film introducing us to a “utopian” animated world where citizens happily play their part in serving Lord Business. As my colleague Jeremy Morris pointed out in a campus symposium on song “hooks,” “Everything is Awesome!!!” is a tongue-in-cheek anthem to teamwork, conformity, and the dominant ideologies regarding labor and consumerism. Think of it as Adorno and Horkheimer for the toddler set, or better yet, as part of the Frankfurt Pre-School.

As an element of internal critique within The LEGO Movie, “Everything is Awesome!!!” is pretty effective. In a particularly naked example of Marx’s “false consciousness,” we see the characters’ submission to corporate control even as we recognize that all is not awesome in Lego Land.

If only the song weren’t so damned catchy. Like the film, the song appears to be crafted to appeal to both the kids who make up its target demographic and the parents stuck in the theater with them. The melody is deliberately simple with a pitch range and structure that any three year-old could sing. However, the song’s “four on the floor” rhythms and electro-flavored instrumentation also make it palatable to adults as well. The end result is an earworm that insinuated itself into my brain for days at a time.

Much of the song’s success derives from its ability to play it both ways. On the one hand, as a theme song for The LEGO Movie, “Everything is Awesome!!!” gently satirizes the unholy marriage between business and government that structures the Lego universe. On the other hand, though, the song appears in what is essentially a feature-length commercial for toys. Moreover, it is so hooky and memorable that it also helps promote The LEGO Movie in various ancillary markets. Still, if that sounds even more cynical than Begin Again’s depiction of corporate sellout, I can’t think of another song that would better fit what The LEGO Movie tries to accomplish.

The final nominee is “Glory” by John Legend and Common. The song is featured in Selma, Ava DuVernay’s biopic about Martin Luther King Jr. A soulful, gospel-inflected ballad, the song was written as a tribute to the members of the Civil Rights movement who worked tirelessly in their fight for equality, especially their efforts to help passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. It appears during an epilogue underscoring a montage that mixes fictional scenes with photographs and archival footage of the real-life Selma marches. The sequence also relates the fates of the various historical actors depicted in the film, reminding us of the sacrifices they made.

With its soaring chorus and rapped verses, “Glory” is decidedly contemporary fare. Yet it remains a worthy successor to the rhythm-and-blues classics heard in the film, such as Otis Redding’s “Ole Man Trouble” and The Impressions’s “Keep on Pushin’”.

Like the other four nominees, “Glory” displays the kind of multi-functionality that is the hallmark of great movie songs. Its style reminds viewers of the important role played by black churches in the early years of the Civil Rights movement. The song’s uplifting tone also provides a satisfying emotional climax to the film, providing a sense of triumph over the physical and political challenges faced by the film’s characters. Lastly, Common’s lyrical reference to the protests of Ferguson also reminds us that the struggles for civil rights continue.

The historical parallels between current events and protests portrayed in Selma have earned considerable commentary by pundits and journalists. And one doesn’t need to hear the song or even see the movie to understand the reasons why the phrase “Black lives matter” resonates across these different generations. Yet Legend and Common’s song makes perhaps the film’s most concrete and explicit connection between past and present. By linking the literal and metaphorical dimensions of Selma’s historical allegory, “Glory” achieves an associative richness that very few recent movie songs can match.

Prediction

Entertainment Weekly characterizes this as a two-horse race. The magazine suggests that “Everything is Awesome!!!” and “Glory” each give voters a chance to right a perceived wrong, honoring a film snubbed in some of the other categories.