Archive for the 'Awards' Category

Women, Oscars, and power

Kathleen Kennedy on the 1 January 2013 cover.

Kristin here:

Now that I have your attention …

We are now well into the season when award speculation begins. Well, actually Oscar speculation knows no season these days, but it snowballs between now and the announcement of the winners on March 4–at which point the speculation concerning the 2018 Oscar race revs up.

Among the issues that will inevitably come up is the question of whether more women directors will get nominated, especially following the critical and box-office success of Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman. It would be great to see more female nominees for Best Director, but the real problem is achieving more equity in the number of women being able to direct films at all. Unless more women direct more films, their odds of getting nominated will be low. Maybe the occasional Kathryn Bigelow will emerge, but overall the directors making theatrical features remain largely male.

Variety recently ran a story about initiatives to boost women’s chances in Hollywood. It stressed the low percentage of women in various key filmmaking roles:

The Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State University found that in 2014, women made up just 7% of the directors behind Hollywood’s top 250 films. Overall, of the 700 films the center studied in 2014, 85% had no female directors, 80% had no female writers, 33% had no female producers, 78% had no female editors and 92% had no female cinematographers.

Discouraging, except that there’s one figure that doesn’t support the lack of women. If 33% of films were without female producers, that means 67% had female producers–which is a lot better than in those other categories.

One thing that has struck me as odd is the lack of attention paid to the distinct rise in the number of female producers being up for Oscars in the recent past. This Variety article, however, is the first one I’ve seen offering numbers to show that women are doing a lot better in the producing field than in other major areas.

The missing names

Kathleen Kennedy, the lady illustrated at the top of this entry has produced seven films nominated as Best Picture, and she is considered one of the most powerful people in Hollywood. How could she not be? She produced Steven Spielberg’s films, alongside others, for many years and since October, 2012, she has been President of Lucasfilm in its incarnation as a subsidiary of Disney. She runs the Star Wars series.

In the Indie realm, producer Dede Gardner is on a roll, having since 2011 had three films nominated for the top prize in addition to wins in 2013 and 2016. Others, such as Megan Ellison and Tracey Seaward, have enjoyed multiple nominations. (I’m using the film’s year of release rather than the year when the award was bestowed.) As we’ll see, female producers are beginning to catch up to their male colleagues in number as well as prestige. Why no fuss about such important strides?

I think the main reason is that there’s no “Best Producer” category. If there were, I suspect our image of women in the industry would be very different. But there’s just a Best Picture one. In most cases neither the industry journals nor the infotainment coverage lists the producers alongside the titles of the Best Picture nominees. So who’s to know that the “Best Picture” race also is, faut de mieux, the “Best Producer” contest.

Another, perhaps less important reason why producers draw less attention is that because a film often has several producers. It’s more complicated to assign responsibility for who did what. Most people have a general idea of what directors do. They’re on set, they make decisions, and they supervise other artists. A female producer, like a male one, may have been included for many reasons. She might have done most of the work in assembling the main cast or crew members or she might have concentrated on gaining financial support. She might instead be termed a producer as a reward for crucial support at one juncture. We can’t know, and that perhaps makes it difficult for the public to get enthusiastic about producers. Of course, if journalists covered them more in the entertainment press, the public might gain more of a sense of what producers do.

Yet whatever their contribution, those producers played some sort of crucial role, and they are the ones who get up and receive the statuettes when that last climactic announcement of the evening is made. (Lately there has been a trend for the every member of the cast and crew and all their relatives present to rush onto the stage for a grand finale, but it’s the producers who give the thank-you speeches.) They can take those statuettes, with their names engraved on them, home and put them on their mantels or to their office to display in a glass case. Yet few have any name recognition outside the industry, the entertainment press, and a few academics.

Despite these producers’ importance, it’s difficult to find out who they have been over the years. Go to almost any website, including the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ own, in search of Oscar nominees stretching back through the years, and you will usually find names listed in all the other categories–but only the title of the nominated films in the Best Picture category. I finally found a complete list of Best Picture nominees’ producers compiled by an industrious contributor to Wikipedia. Going through and doing some counting and cross-checking, I have created and annotated my own list. With it I’ve tried to show the fairly steady progress that women have made in this category. I call them “nominees” below. Somewhat paradoxically, they win the Oscars, though technically the film is the official nominee.

To keep this list from becoming even longer, I’ve listed only nominated films which had one or more women among their group of producers. Up to 2008 there were five films each year. Starting in 2009 the number could be anywhere between five and ten, though it’s usually eight or nine. I give the number of nominated films starting in 2009. Assume any films not listed were produced by men. If you’re curious about who those men were, click on the link in the previous paragraph.

Here’s how things developed, including only years when female producers were “nominated.” (My comments in red.) Be patient. It gets off to a slow start, but things pick up.

And the nominees are …

1973 The Sting (WINNER) Tony Bill, Michael Phillips, and Julia Phillips.

Julia Phillips becomes the first female producer nominated since the Oscars began in 1927 and the first to win.

1982 E.T. Steven Spielberg and Kathleen Kennedy.

The second female producer nominated.

1984 Places in the Heart. Arlene Donovon.

The third nominated female producer.

1987 Fatal Attraction. Stanley R. Jaffe and Sherry Lansing.

The fourth nominated female producer.

1989 Driving Miss Daisy. (WINNER) Richard D. Zanuck and Lili Fini Zanuck.

Lili Fini Zanuck is the second female producer to win.

1991 The Prince of Tides. Barbra Streisand and Andrew S. Karsch.

1994 Forrest Gump. (WINNER) Wendy Finerman, Steve Tisch, and Steve Starkey.

The Shawshank Redemption. Niki Marvin.

Wendy Finerman (right) becomes the third woman producer to win a Best Picture Oscar.

This is the first year when two women are nominated. From this point to the present, there has been no year without at least one female producer nominated.

1995 Sense and Sensibility. Lindsay Doran.

1996 Shine. Jane Scott.

1997 As Good as It Gets. James L. Brooks, Bridget Johnson, and Kristi Zea.

The first year when four women are nominated.

The first time two women are nominated for the same film.

1998 Shakespeare in Love. (WINNER) David Parfitt, Donna Gigliotti, Harvey Weinstein, Edward Swick, and Marc Norman.

Elizabeth. Alison Owen, Eric Fellner, and Tim Bevan.

Life Is Beautiful. Elda Ferri and Gianluigi Brasch.

Gigliotti is the fourth woman to win a producing Oscar.

1999 The Sixth Sense. Frank Marshall, Kathleen Kennedy, and Barry Mendel.

First year when a woman producer, Kennedy, is nominated for a second time.

2000 Chocolat. David Brown, Kit Golden, and Leslie Holleran.

Erin Brockovich. Danny DeVito, Michael Shamberg, and Stacey Sher.

For the second time, two women are nominated for the same film.

2001 The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Barrie O. Osborne.

2002 The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers. Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Barrie O. Osborne.

2003 The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. (WINNER) Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Barrie O. Osborne.

Lost in Translation. Ross Katz and Sofia Coppola.

Mystic River. Robert Lorenz, Judie G. Hoyt, and Clint Eastwood.

Seabiscuit. Kathleen Kennedy, Frank Marshall, and Gary Ross.

Walsh is the fifth woman to win in this category.

Walsh and Kennedy tie for the first woman nominated three times.

The second year when four women are nominated.

2004 Finding Neverland. Richard N. Gladstein and Nellie Bellflower.

2005 Crash. (WINNER) Paul Haggis and Cathy Schulman.

Brokeback Mountain. Diana Ossance and James Schamus.

Capote. Caroline Baron, William Vince, and Michael Ohoven.

Munich. Steven Spielberg, Kathleen Kennedy, and Michael Mendel.

Cathy Schulman is the sixth woman to win.

The third time four women are nominated.

Kennedy becomes the first woman nominated four times.

2006 The Queen. Andy Harris, Christine Langan, and Tracey Seaward.

2007 Michael Clayton. Jennifer Fox and Sydney Pollack.

Juno. Lianne Halfon, Mason Novack, and Russell Smith.

There Will Be Blood. Paul Thomas Anderson, Daniel Lopi, and JoAnne Sellar.

The first year in which five women are nominated in this category.

2008 The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. Kathleen Kennedy, Frank Marshall, and Céan Chaffin.

The Reader. Anthony Minghella, Sydney Pollack, Donna Gigliotti, and Redmond Morris.

The Reader. Anthony Minghella, Sydney Pollack, Donna Gigliotti, and Redmond Morris.

First time a woman, Kennedy, reaches a fifth nomination.

The third time two women are nominated for the same film.

2009 The first year of up to ten nominations. Ten films nominated.

The Hurt Locker. (WINNER) Kathryn Bigelow, Mark Boal, Nicholas Chartier, and Greg Shapiro.

District 9. Peter Jackson and Carolynne Cunningham.

An Education. Finola Dwyer and Amanda Posey.

Precious. Lee Daniels, Sarah Siegel-Magness, and Gary Magness.

Kathryn Bigelow becomes the seventh woman to win in this category. (Right, with her producing and directing Oscars.)

The fourth time two women are nominated for the same film.

2010 Ten films nominated.

Inception. Christopher Noland and Emma Thomas.

The Kids Are All Right. Gary Gilbert, Jeffrey Levy-Hinte, and Celine Rattray.

The Social Network. Pana Brunetti, Céan Chaffin, Michael De Luca, and Scott Rudin.

Toy Story 3. Darla K. Anderson.

Winter’s Bone. Alex Madigan and Ann Rossellini.

The second year five women are nominated in this category.

2011 Nine films nominated.

Midnight in Paris. Letty Aronson and Stephen Tenebaum.

Moneyball. Michael De Luca, Rachael Horovitz, and Brad Pitt.

The Tree of Life. Sarah Green, Bill Pohlad, Dede Gardner, and Grant Hill.

War Horse. Steven Spielberg and Kathleen Kennedy.

Kennedy receives her sixth nomination.

The third year in which five women are nominated in this category.

The fifth time two women are nominated for the same film.

2012 Nine films nominated.

Amour. Margaret Mengoz, Stefan Arndt, Veit Heiduschka, and Michael Katz.

Django Unchained. Stacey Sher, Reginald Hudlin, and Pilar Savone.

Les Misérables. Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner, Debra Hayward, and Cameron Mackintosh.

Lincoln. Steven Spielberg and Kathleen Kennedy.

Silver Linings Playbook. Donna Gigliotti, Bruce Cohen, and Jonathan Gordon.

Zero Dark Thirty. Mark Boal, Kathryn Bigelow, and Megan Ellison.

Eight female producers nominated, besting the previous record by three.

The first year in which each of two nominated films has two female producers.

Kennedy receives her seventh nomination.

2013 Nine films nominated.

12 Years a Slave. (WINNER) Brad Pitt, Dede Gardner, Jeremy Klein, Steve McQueen, and Anthony Katugas.

American Hustle. Charles Roven, Richard Suckle, Megan Ellison, and Jonathan Gordan.

Dallas Buyers Club. Robbie Brennert and Rachel Winter.

Her. Megan Ellison, Spike Jonze, and Vincent Landay.

Philomena. Gabrielle Tana, Steve Coogan, and Tracey Seaward.

The Wolf of Wall Street. Martin Scorsese, Leonardo DiCaprio, Joey McFarland, and Emma Tillinger Koskoff.

Dede Gardner becomes the eighth woman to win an Oscar in this category.

Megan Ellison becomes the first woman nominated for two films in the same year.

2014 Eight films nominated.

Boyhood. Richard Linklater and Cathleen Sutherland.

The Imitation Game. Nora Grossman, Ido Wostrowskya, and Teddy Scharzman.

Selma. Christian Colson, Oprah Winfrey, Dede Gardner, and Jeremy Kleiner.

The Theory of Everything. Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner, Lisa Bruce, and Anthony McCarten.

Whiplash. Jason Blum, Helen Estabrook, and David Lancaster.

2015 Eight films nominated.

Spotlight. (WINNER) Blye Pagon Faust, Steve Golin, Nicole Roaklin, and Michael Sugar.

The Big Short. Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, and Brad Pitt.

Bridge of Spies. Steven Spielberg, Marc Platt, and Kristie Macosko Krieger.

Brooklyn. Finola Dwyer and Amanda Posey.

The Revenant. Arnon Milchan, Steve Golin, Alejandro G. Iñárittu, Mary Parent, and Keith Redmon.

Blye Pagon Faust and Nicole Roaklin become the ninth and tenth winners.

For the first time two women win for the same film.

For the second time, two nominated films have two female producers.

2016 Eight films nominated.

Moonlight. (WINNER) Adela Romanski, Dede Gardner, and Jeremy Kleiner.

Hell or High Water. Carla Haaken and Julie Yorn.

Hidden Figures. Donna Gigliotti, Peter Chernin, Jenro Topping, Pharrell Williams, and Theodore Melfi.

Lion. Emile Sherman, Iain Canning, and Angie Fielder.

Manchester by the Sea. Matt Damon, Kimberly Steward, Chris Moore, Lauren Beck, and Kevin J. Walsh.

Adela Romanski and Dede Gardner become the eleventh and twelfth winners.

For the second time, two women win for the same film.

For the second time, eight women are nominated, which so far remains the record.

Why should these names be hidden?

So we have overall 88 nominations for women, with twelve women winning Oscars for producing films. That compares with four nominations and one win for female directors. Women have not come all that close to parity with men in the producing category, but compared to the directors category, which people seem to take as a bellwether for the status of professional women in Hollywood, it’s spectacular. Moreover, we can see a fairly steady growth over the past twenty-three years, to the point where seven or eight producing nominations a year routinely go to women.

Of course, Oscars are not the only or the most objective way of measuring women’s power in Hollywood. One could try a similar examination of the number of women producing Hollywood’s top box-office films over the years. I assume there would be a similar growth in numbers, but the measurement would probably be a little more nuanced. That would be a much bigger project than would fit in a blog entry–even entries as long as the ones we occasionally favor our readers with. The San Diego State University study I mentioned earlier took an approach of this sort, and I’m sure there is deeper digging to be done among the statistics revealed by such research..

Given the way the Oscars have captured the public’s and the industry’s imaginations, however, the growing number of female producers being honored is a good way to point out that things may be better than they seem when one focuses narrowly on the directors category.

After all, the prescription for putting more women in the director’s chair and behind the camera and so forth is always that more female producers and writers are needed, making films for women and by women. This seems reasonable, and yet the question remains, if women are doing so well, relatively speaking, in rising to the top as producers, why, over the twenty-three years since 1994 haven’t they hired more women at every level for their film crews? (Of course, some of them have acted as producer-directors on their own projects.) Why hasn’t Kennedy, who has been firing and hiring male directors for Star Wars projects lately, ever given a female director a shot at it? Maybe she will at some point, as the evidence grows that women can create hits.

Perhaps most women producers are constrained by their fellow producers on projects, who are often men. They may feel pressured to reassure studio stockholders and financiers by sticking with the tried and true. And yet there do finally seem to be signs that studios are looking beyond the obvious pool of talent. Patty Jenkins, an indie filmmaker, directs Wonder Woman to unexpected success. Taika Waititi, a Maori-Jewish indie filmmaker from New Zealand, suddenly finds himself directing Thor: Ragnarok, which shows every sign of becoming a hit. With luck, the effect of the rise of female producers, as well as of more broadminded male ones, will finally have a significant impact on both gender and ethnic diversity in Hollywood filmmaking.

In closing, I would suggest to the press that it would be helpful for them in writing their endless awards coverage to list more than just the titles of the Best Picture nominees. Add the names of their producers, who are in effect nominated for Oscars. Treat them more like stars, the way you do with directors. I realize that there are often lingering disputes over which of the many producers attached to some films are actually the ones eligible to accept Oscars for them. But once such disputes are resolved, these “nominees” should be listed, and certainly after the awards are given out, they should be part of the historical record of Oscar nominees and winners. This would help both the public and the industry to get the big picture, not just the Best Picture.

[Oct. 24, 2017: My thanks to Peter Nellhaus for pointing out Julia Phillips’ win for The Sting in 1973. I have corrected the text accordingly.]

The Shawkshank Redemption (1994).

The sirens’ song for Oscar

The Lego Movie.

Another guest blog this week, this time from Jeff Smith, our colleague in the department here at UW–Madison. Jeff is one of America’s experts on movie music and sound technology. He contributed an entry on Atmos last year. He has written many articles on film sound, along with two books: The Sounds of Commerce and Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. He’s also our collaborator on the eleventh edition of Film Art: An Introduction.

‘Tis the season for Oscar buzz, and the media glut of award prognostications is already upon us. Most of the attention will go to the above-the-line talent who’ve received nominations (actors, directors, and screenwriters). The craft categories tend to get much less scrutiny, but the work of cinematographers, editors, and composers plays an equally important role in making their films award-worthy.

Today I offer some observations about this year’s nominees in the music categories: Best Original Score and Best Original Song. By using the nominees as examples, I hope to illuminate some of the ways that music continues to contribute to cinema’s narrative functions and its emotional impact on viewers. I’ll also offer my predictions for who will win at the end of each section.

Best Original Score

Even before this year’s nominees were announced, one of 2014’s most distinctive and innovative film scores was declared ineligible by the Academy. Antonio Sanchez’s driving percussion score for Birdman was disqualified under Rule 15, which states that scores “diluted by the use of tracked themes or other pre-existing music, diminished in impact by the predominant use of songs, or assembled from the music of more than one composer shall not be eligible.” Apparently, in the view of the Academy’s music branch, Birdman’s use of substantial excerpts of concert music by Mahler, Tchaikovsky, Ravel, and John Adams weakened the impact of Sanchez’s score. That explanation, though, probably doesn’t pass the eyeball (or eardrum) test of anyone who has seen Alejandro González Iñárritu’s film. Sanchez’s drum work adds verve and energy to several of the director’s elaborately choreographed (and seamlessly stitched together) long takes.

Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’s electronic score for Gone Girl was also a notable snub, especially since their bold, pathfinding music for The Social Network took home the top prize just four years ago. The fact that both of these scores failed to secure nominations may be a sign that the Academy’s music branch is returning to the verities of good old-fashioned melody and harmony as the basic tools in the composer’s kit.

That being said, the absence of Sanchez, Reznor, and Ross from the list of nominees doesn’t mean that the remaining scores are dull or unadventurous. Quite the contrary. Several of them push film composition in new and exciting directions. Their scores fulfill traditional functions but employ innovative scoring techniques and orchestrations.

Old sounds, new sounds

Take, for instance, Gary Yershon’s score for Mike Leigh’s biopic, Mr. Turner. Bypassing the conventions of orchestral writing for film, Yershon composed for a chamber-sized ensemble. Some cues combine a saxophone quartet with a string quintet, a musical choice that seems deliberately anachronistic. (As Yerson himself says in the soundtrack’s liner notes, Adolph Saxe’s invention wasn’t even patented until 1846, just a few years before Turner’s death.) Other cues add flute, clarinet, harp, tuba, or timpani to the mix. But these embellishments simply add color to the basic sound of Yershon’s twin string and saxophone ensembles.

Yershon says he was attracted to the saxophone due to its ability to glissando – that is, bend pitch from one note to another. Yershon certainly exploits this element of the instrument’s sound by building his melodies from long sustained notes that slowly take on serpentine shapes. Saxophone glissandi have an almost iconic function in the idioms of jazz and pop music . (Think of the opening phrase of Wham’s “Careless Whisper.”) In this case, though, the technique gives Yershon’s score a minimalist, modernist edge.

Yershon’s inclusion of a saxophone quartet departs from two norms: the period music of Turner’s time and the symphonic orchestrations that have characterized biopics for decades. The saxophone was never a major component of the Hollywood sound crafted during the studio era. Composers like Max Steiner and Victor Young occasionally included saxophones in their arrangements of music played onscreen by dance bands, but for the most part, their wind arrangements were for some combination of flutes, oboe, English horn, clarinets, and bassoons.

Is Yershon’s score inappropriate on historical grounds? I don’t think so. By modernizing the sound of Leigh’s period biopic, Yershon’s score adds a contemporary resonance, perhaps encouraging viewers to see parallels between Turner’s painting and the work of modern-day artists. Indeed, as Guy Lodge noted in his Hitfix review of the film, “It’s tempting, even, to view the film as biopic-as-self-portrait, revealing shades of one life through another. Leigh has a reputation for prickliness and resistance to self-explication; perhaps it’s not surprising that he’s long been fascinated by Turner’s allegedly gruff, taciturn genius.”

Yershon’s use of contemporary instruments may not in itself suggest those historical parallels. Indeed, most viewers probably have no idea when the saxophone was invented. But it certainly invites us to think about Leigh and Yershon’s reasons for opting for such a modern sound. And with its smaller instrumental forces, Yershon’s score resists some of the sweeping emotionalism that is found in other examples of the genre.

Zimmer pulls out all the stops

Hans Zimmer’s nomination for Interstellar is the tenth of his long and distinguished career. With all apologies to John Williams, Zimmer is arguably Hollywood’s leading film composer and his work is emblematic of a larger industry turn toward emphasizing musical tone and texture rather than big memorable themes. Zimmer’s score for Interstellar is no exception to this rule. In this case, though, much of the tone and texture is provided by the four-manual Harrison & Harrison pipe organ found in London’s Temple Church.

Director Christopher Nolan says that he liked the sound of the church organ as something that added an element of religiosity to Interstellar. But the organ contributes other things as well. For one thing, the organ’s booming bass register adds mass and heft not only to the music, but also to the astronomical bodies shown onscreen. The sheer size of these lower frequencies enhances the sense of scale in Nolan’s imagery. Thanks to the organ’s huge pitch range, the instrument’s upper register provides the quieter, swirling arpeggios needed to suggest the story’s filial bonds between father and daughter. At the same time, the instrument’s big, fat bottom end adds the musical bombast needed to convey the film’s epic visions of distant planets, wormholes, and alternate dimensions.

More important, despite the church organ’s strong association with sacred and liturgical music, Zimmer’s score never sounds like a Bach toccata. Rather, due to its repetitive, but intricate arpeggiations and simple, but affecting harmonic structures, Interstellar’s music has the kind of trippy, drone-ish, psychedelic feel that suggests both Terry Riley and Iron Butterfly. Zimmer’s score does not contain anything that is an obvious quote from the music of Stanley Kubrick’s “thinking man’s” sci-fi classic, 2001: A Space Odyssey. Yet, in its own way, Zimmer’s music recalls the period where such films were being produced, indeed the very kind of film that Nolan self-consciously tried to recreate.

In developing the score for Interstellar, Nolan and Zimmer also departed from the norms for director-composer collaborations. Most composers begin their work at a fairly late stage in the filmmaking process. In some cases, they may work from a completed script. In most cases, though, a composer starts with a rough cut of the film, making his or her contribution felt only during post-production.

In contrast, Nolan acknowledged that he has gradually been bringing Zimmer into his production at earlier and earlier stages. Nolan dislikes the practice of temp tracking, a technique that involves slugging in preexisting music that temporarily serves as a guide to the production team during the editing process. Says Nolan, “To me music has to be a fundamental ingredient, not a condiment to be sprinkled onto the finished meal.”

For Interstellar, Nolan asked to meet with Zimmer well before production began. As Nolan recounts in the liner notes to the soundtrack, he gave the composer an envelope containing a one-page summary of the fable that sat at the heart of the story. The description did not contain any details of the film’s genre or plot. Rather the summary simply laid out the narrative’s emotional core. Zimmer then took the summary and retired to his studio to start composing. Several hours later, Zimmer brought back a CD that contained about three or four minutes of music. Nolan listened to the new piece: a simple piano melody that nonetheless captured the feeling of what the director says he was “already struggling with on the page.”

When Nolan began shooting, he frequently listened to Zimmer’s simple piano piece, which functioned as a kind of “emotional anchor” for the film. Eventually, Zimmer returned to the studio and created the huge musical canvas that captures Interstellar’s heady exploration of space and time. Underneath it all, though, is the humble melody Zimmer wrote prior to production, the modest edifice upon which the rest of the score is built.

More songs about buildings and food service

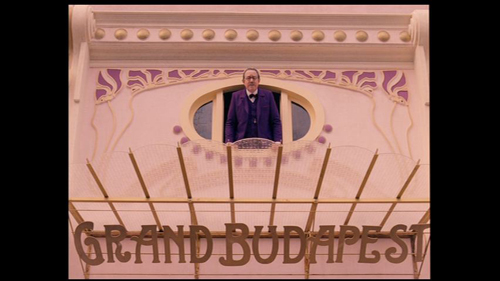

Like Zimmer, Alexandre Desplat has several previous nominations to his credit, including those for the scores of Best Picture winners The King’s Speech and Argo. Unlike Zimmer, though, Desplat has yet to win. Among Hollywood’s current A-list composers, Desplat has shown extraordinary versatility. He’s at home writing for foreign art films, American indies, animation, and studio genre pictures. Desplat’s score for Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel is the third he has done for the director, following earlier collaborations on The Fantastic Mr. Fox and Moonrise Kingdom.

Here again, Desplat’s score for The Grand Budapest Hotel departs from established norms of Hollywood orchestration. Although he uses a slightly smaller version of the wind and brass sections usually found in older Hollywood film scores, he avoids the normal violins, violas and cellos. Instead he opts for a string section comprised of balalaikas, cimbaloms, zithers, mandolin, and acoustic guitar. This choice is intended to reflect the vaguely Mitteleuropean setting of the film. Just as the story is loosely inspired by the writings of Austrian novelist Stefan Zweig, the music reflects the social and geographical milieu of Zweig and his characters during the 1920s and 1930s. Eastern European and Russian folk melodies inspired much of Desplat’s. This combination of instrumentation and idiom creates a harmonic and timbral palette that proves to be enormously flexible in the composer’s hands, enabling him to add classical, modern, and jazz touches wherever they are needed.

Although Desplat employs unusual orchestration in The Grand Budapest Hotel, his score is fairly traditional in other ways. There are leitmotifs for several of the main characters, such as M. Gustave, Zero, Madame D., and Ludwig. An eight-measure theme is also linked to situations of adventure or danger. These themes and motifs tighten up the film’s structure. Such cues for patterning are particularly important when one considers The Grand Budapest Hotel’s “Chinese box” or “Russian doll” narrative construction, which nests stories inside stories.

Desplat’s score also captures the film’s dark yet whimsical tone. In interviews, the composer acknowledges that Bernard Herrmann and Carl Stalling were important influences on his work. At first blush, Herrmann, who composed several iconic scores for Alfred Hitchcock, and Stalling, who wrote crazy, almost manic music for Disney and Warner Bros. cartoons, would seem to occupy opposite corners of the universe. It’s to Desplat’s credit, though, that he is able to blend these diverse influences in a manner that is perfectly attuned to Wes Anderson’s imaginary “snow-globe” world. Indeed, the cue for the scene where Gustave is hanging from a cliff features harmony that would not be out place in Herrmann’s score for North by Northwest, an obvious inspiration.

But the mood is much lighter and airier in Anderson’s cliffhanger, partly because of the tenor established by Desplat’s music.

Scoring the Beautiful Minds of Cambridge

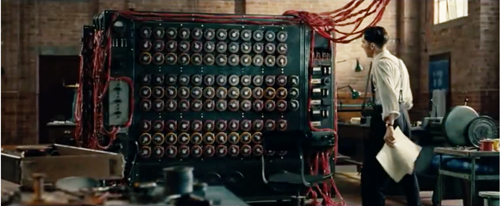

Ironically, Desplat’s chief competition may come from himself. Besides The Grand Budapest Hotel, Desplat also received a nomination for the fact-based espionage thriller, The Imitation Game. It was the fourth time in the last fifteen years that a single composer received two Oscar nominations for Best Original Score. And like the other nominees discussed here, Desplat developed an unusual compositional technique for the film, allowing for an element of randomness to determine his score’s final musical shape.

Whereas Sanchez deviated from compositional norms by improvising beats for Birdman, Desplat’s score for The Imitation Game pushes the envelope by featuring three computerized pianos, which sometimes play random patterns of preprogrammed music. According to the composer, the pianos’ fast, complex combinations not only underscore the urgency of the Bletchley Park team’s search for a solution to the Nazis’ Enigma code, but they also function as an musical correlative of cryptanalyst Alan Turing’s thought processes. As director Morton Tyldum put it, he wanted the music to seem subjective, as though it was conveying the mental operations inside the head of an awkward, but brilliant mathematician.

Desplat’s use of rapid scales and arpeggios to represent Turing’s genius actually recalls Philip Glass’ score for Errol Morris’s documentary about Cambridge physicist Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time. To be fair, Glass’ compositional style has employed these kinds of musical textures in many other types of cinematic contexts. Glass’s work not only appears in other Morris films, but also in biopics about Japanese writer Yukio Mishima and the Dalai Lama, and even in horror films and dramas, such as Candyman and The Hours. Given the constancy of his compositional proclivities, it is perhaps easy to make too much of Glass’s ability to depict the depth and brilliance of Hawking’s intellect. Yet there is little question that Glass’s music adds both a sense of mystery and majesty to Morris’s imagery, which itself explores such imponderables as the nature of time and the origins of the universe.

Because of this precedent, it is perhaps doubly striking that composer Johann Johannson took such a different tack in his music for the Hawking biopic, The Theory of Everything. With long sustained string lines and simple piano melodies, Johannson aims for a soft lyricism that is intended to add both pathos and subdued passion to the film’s depiction of Hawking’s relationship with his wife Jane. Since the film is based on Jane’s account of their marriage, it is probably not surprising that Johannson’s score plays her point of view even more than it does that of its putative subject. As the composer explains, the “heart of the film is the love story: Stephen and Jane, Jane and Jonathan. That’s really what the music needed to capture.” Thanks to Johannson’s use of harpsichord, celeste, harp, and guitar, the tone colors of the music remain light, making his score for The Theory of Everything a modern counterpart to the work of the Georges Delerue.

Prediction

All five nominees are quite worthy of the award for Best Original Score. But, if I had the opportunity vote, I would probably cast it for The Grand Budapest Hotel. Not only is Desplat’s score perfectly attuned to Wes Anderson’s distinctive style, but it would be nice to see the composer recognized for the overall quality of his oeuvre. Desplat’s fans, though, probably split their votes between The Grand Budapest Hotel and The Imitation Game, thereby increasing the chances that he’ll once again go home empty-handed.

In underlining The Theory of Everything’s romance plotline, Johansson’s score is perhaps the most traditional among the five nominees. I don’t believe, though, that its adherence to longstanding film score conventions will hurt it on Oscar night. Johansson’s sweet lyricism already carried the day at the Golden Globes, an award that has correctly predicted the eventual Oscar winner four out of the last five years. Although there could be an upset in this category, I expect we’ll see Johannson triumphantly hoist the little gold man over his head come Sunday night.

Best Original Song

If recent award ceremonies are any indication, this is a category that has fallen a bit on hard times. At least this year, there are five legitimate nominees. Last year one of the nominees was disqualified, and in 2012 and 2011, the category fielded only two and four nominees respectively.

One potential reason for the paucity of original songs may be the previously mentioned turn toward tone and texture in contemporary scoring practice. In the old days, many of the best-remembered and best-loved songs from the movies were crafted from themes specifically composed for the score. This was the case with tunes like Alfred Newman and Frank Loesser’s “Moon of Manakoora” from The Hurricane, Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer’s “Days of Wine and Roses,” or even James Horner and Will Jennings’s “My Heart Will Go On” from Titanic. Since current film composers are turning away from big themes, it seems there is less opportunity to adapt a musical motif into something that works as a theme song. (Of course, there are occasional exceptions. In 2013, Adele and Paul Epworth took home the Oscar for Skyfall, updating the established formula for making Bond theme songs.)

This year’s nominees also lack anything resembling last year’s heavyweight battle between Frozen’s “Let It Go” and Despicable Me 2’s “Happy.” All of the nominees seem quite worthy. None of them, though, has created the kind of cultural ubiquity enjoyed by Idina Menzel’s and Pharrell Williams’s chart-topping singles.

Two of the nominees have the misfortune of appearing in little seen films: Beyond the Lights and Glen Campbell: I’m Not Me. Diane Warren is one of the industry’s top songwriters and her “Grateful” is featured in the former of the two films. Warren also is a seven-time Oscar nominee, and although I believe her time at the podium will eventually come, it seems unlikely this year. Glen Campbell and Julian Raymond’s “I’m Not Gonna Miss You” is a moving ballad, made all the more poignant due to the singer’s ongoing struggles with Alzheimer’s disease. Campbell’s battle, which is the subject of James Keach’s documentary about the singer’s farewell tour, makes the song a counterpart to other epitaph numbers, such as Johnny Cash’s cover of “Hurt” or Warren Zevon’s “Keep Me in Your Heart.”

The third nominee is “Lost Stars” from Begin Again, director John Carney’s belated follow-up to his earlier indie sleeper, Once. “Lost Stars” was written by two members of the nineties band the New Radicals: Gregg Alexander and Danielle Brisebois. The latter has come a long way since her days as a seventies child star appearing in Broadway’s Annie and television’s All in the Family. Starting in the 1990s, Brisebois remade herself as a successful songwriter and producer, penning tracks for Donna Summer, Natasha Bedingfield, Kelly Clarkson, and a host of other top female performers.

“Lost Stars” is heard several times in Begin Again. The first time Gretta (Keira Knightley) performs it in a spare singer-songwriter arrangement featuring acoustic guitar, piano, and strings. It underscores a flashback of Gretta’s arrival in New York with her skeezy rock-star boyfriend Dave (Maroon 5’s Adam Levine). Later, we hear it as a track on Dave’s CD. Here he gives it an up-tempo stadium-pop sheen. Near the film’s end Dave again performs “Lost Stars,” this time as an arena-rock power ballad.

It is unusual to hear an Oscar-nominated song played in such wildly different styles, and even more unusual for one of those versions to be served up in a manner intended to seem excessive and distasteful. Tellingly, the end credits list Dave’s rendering of the song on CD as “Lost Stars (Overproduced Version).” The contrast between them, though, provides important character motivation for the film’s resolution. Dave’s indifference to Gretta’s creative vision of the song shows that he is ill suited to be her romantic partner. It also reveals producer Dan as a much more kindred spirit for Gretta’s professional ambitions. She gets to keep her coffeehouse, folkie purity even as her coffers are filled by the filthy lucre earned from sales of the soulless version featured on Dave’s major-label CD.

Interestingly, on Oscar night, Adam Levine will sing “Lost Stars” as part of the broadcast. If the producers wanted to stay true to the spirit of “Begin Again,” they might have opted for Keira Knightley to perform the song. Yet the fact that Levine was the first performer announced suggests that his star power was simply too much of a draw. Despite the film’s critical view of Dave’s talent, sales of Levine’s version of the song appear to have outpaced Knightley’s. Begin Again may be cynical about the music’s industry’s overinvestment in mainstream tastes, but Levine’s “overproduced” version of “Lost Stars” has done a great deal to give the film much-needed media exposure.

The fourth nominee, The LEGO Movie’s “Everything is Awesome!!!”, arguably displays an even more mind-bending degree of complexity in its relation to the popular music marketplace. The song appears quite early on in the film introducing us to a “utopian” animated world where citizens happily play their part in serving Lord Business. As my colleague Jeremy Morris pointed out in a campus symposium on song “hooks,” “Everything is Awesome!!!” is a tongue-in-cheek anthem to teamwork, conformity, and the dominant ideologies regarding labor and consumerism. Think of it as Adorno and Horkheimer for the toddler set, or better yet, as part of the Frankfurt Pre-School.

As an element of internal critique within The LEGO Movie, “Everything is Awesome!!!” is pretty effective. In a particularly naked example of Marx’s “false consciousness,” we see the characters’ submission to corporate control even as we recognize that all is not awesome in Lego Land.

If only the song weren’t so damned catchy. Like the film, the song appears to be crafted to appeal to both the kids who make up its target demographic and the parents stuck in the theater with them. The melody is deliberately simple with a pitch range and structure that any three year-old could sing. However, the song’s “four on the floor” rhythms and electro-flavored instrumentation also make it palatable to adults as well. The end result is an earworm that insinuated itself into my brain for days at a time.

Much of the song’s success derives from its ability to play it both ways. On the one hand, as a theme song for The LEGO Movie, “Everything is Awesome!!!” gently satirizes the unholy marriage between business and government that structures the Lego universe. On the other hand, though, the song appears in what is essentially a feature-length commercial for toys. Moreover, it is so hooky and memorable that it also helps promote The LEGO Movie in various ancillary markets. Still, if that sounds even more cynical than Begin Again’s depiction of corporate sellout, I can’t think of another song that would better fit what The LEGO Movie tries to accomplish.

The final nominee is “Glory” by John Legend and Common. The song is featured in Selma, Ava DuVernay’s biopic about Martin Luther King Jr. A soulful, gospel-inflected ballad, the song was written as a tribute to the members of the Civil Rights movement who worked tirelessly in their fight for equality, especially their efforts to help passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. It appears during an epilogue underscoring a montage that mixes fictional scenes with photographs and archival footage of the real-life Selma marches. The sequence also relates the fates of the various historical actors depicted in the film, reminding us of the sacrifices they made.

With its soaring chorus and rapped verses, “Glory” is decidedly contemporary fare. Yet it remains a worthy successor to the rhythm-and-blues classics heard in the film, such as Otis Redding’s “Ole Man Trouble” and The Impressions’s “Keep on Pushin’”.

Like the other four nominees, “Glory” displays the kind of multi-functionality that is the hallmark of great movie songs. Its style reminds viewers of the important role played by black churches in the early years of the Civil Rights movement. The song’s uplifting tone also provides a satisfying emotional climax to the film, providing a sense of triumph over the physical and political challenges faced by the film’s characters. Lastly, Common’s lyrical reference to the protests of Ferguson also reminds us that the struggles for civil rights continue.

The historical parallels between current events and protests portrayed in Selma have earned considerable commentary by pundits and journalists. And one doesn’t need to hear the song or even see the movie to understand the reasons why the phrase “Black lives matter” resonates across these different generations. Yet Legend and Common’s song makes perhaps the film’s most concrete and explicit connection between past and present. By linking the literal and metaphorical dimensions of Selma’s historical allegory, “Glory” achieves an associative richness that very few recent movie songs can match.

Prediction

Entertainment Weekly characterizes this as a two-horse race. The magazine suggests that “Everything is Awesome!!!” and “Glory” each give voters a chance to right a perceived wrong, honoring a film snubbed in some of the other categories.

As I indicated earlier, I find the pop panache of “Everything is Awesome!!!” undeniable. More important perhaps, the filmmakers adroitly weave the song into particular scenes in The LEGO Movie. Still, I don’t think that will be enough for “Everything is Awesome!!!” to take home the top prize. In underscoring Selma’s import and its timeliness, “Glory” does something that none of the other nominees does. By drawing together African-American musical styles, both past and present, “Glory” is imbued with a political and historical resonance that strives for higher ground. For that reason, I expect John Legend and Common will add Oscar to the other accolades they have received.

First, many thanks to Jeremy Morris, my colleague in the University of Wisconsin’s Communication Arts Department, whose thoughts on The LEGO Movie have unquestionably shaped my own. A shout-out also to Jon Burlingame, whose coverage of film music topics in Variety is second to none. Burlingame has surveyed the best Original Score nominees, and the Best Original Song nominees.

On Desplat, see Burlingame’s article “Alexandre Desplat’s Twin Takes on WWII: ‘The Imitation Game’ and ‘Unbroken.” Additionally, Matt Zoller Seitz’s companion volume to The Grand Budapest Hotel contains an interview with Desplat and an analysis of the score that reproduces excerpts from certain cues. More on Seitz’s book can be found in this promo film. The Grand Budapest Hotel’s entire soundtrack is on YouTube. Earlier entries on The Grand Budapest Hotel on this site are here and here.

For those interested in the development of Interstellar’s score, there’s a short video on J. Bryan Lowder’s blog containing interviews with both Christopher Nolan and Hans Zimmer. Lowder offers a thorough overview of Zimmer’s score here. John Legend offers comments on his song for Selma.

Begin Again.

Oscar fever up close

Kristin here:

Most years when I’m at home, I join in our departmental Oscar party, where grad student and faculty get together to watch the broadcast and match wits at predicting the winners. It beats the grimness of sitting home watching the show.

But this year, being a relatively new staff member on TheOneRing.net, I decided to attend their celebration, “The One Expected Party,” for The Hobbit. TORn put on three Oscar parties for The Lord of the Rings, in 2002, 2003, and 2004. Those parties became the stuff of legend within the fandom, having rapidly sold out each time. The nominees and winners from the trilogy dropped by the TORn party each year (fueling the next year’s ticket sales). I wrote about the Oscar parties as part of my coverage of TORn in my book, The Frodo Franchise, but I had never been to any of them.

In planning my trip, I quickly discovered that there are a lot of other activities around the run-up to the Oscar ceremony. I knew, of course, that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences offers screenings of the nominated films to their members and to anyone else lucky enough to get a ticket. But our old friend Chen Mei, who works for the Academy library, told me about panel sessions featuring the nominees in various categories and kindly obtained tickets for me to attend two of them.

Obviously the nominees take these events seriously. For both of those I attended, with one exception all the directors of the nominated films showed up to answer questions from a moderator. Obviously they couldn’t hope to influence the members’ votes, since the ballots had already been turned in. They generously gave time to offer insights into their work to audiences who clearly were knowledgeable about filmmaking.

“Oscar Celebrates Animated Features”

This panel discussion took place on the evening of February 21, the day I arrived in Los Angeles. When I got to the Academy’s Samuel Goldwyn Theatre, more than an hour before the 7:30 event, there was already a long line of ticket-holders hoping to get good seats. I gathered from conversations with people around me in line that tickets are getting harder to obtain each year.

Most of the best seats were roped off, reserved for Academy members and the guests of honor. I got an unreserved one in the second row but way over on the side. It actually gave a pretty good view of the stage. Unfortunately photos are strictly forbidden inside the Samuel Goldwyn Theatre, so I have none to show you.

Most of the best seats were roped off, reserved for Academy members and the guests of honor. I got an unreserved one in the second row but way over on the side. It actually gave a pretty good view of the stage. Unfortunately photos are strictly forbidden inside the Samuel Goldwyn Theatre, so I have none to show you.

Almost all of the directors of all five nominated features were there: Peter Lord for The Pirates! Band of Misfits; Sam Fell and Chris Butler for ParaNorman; Mark Andrews for Brave (co-director Brenda Chapman being unable to attend); Rich Moore for Wreck-It Ralph; and Tim Burton for Frankenweenie. (All but Burton stuck around to pose for the press; left to right, Moore, Butler, Andrews, Lord, and Fell.)

This line-up of talent should have made for an enlightening evening. Unfortunately the AMPAS had chosen as MC a comic actor, Rob Riggle (Talladega Nights, The Hangover) who turned out to know less about animation than most of the people in the audience did. He was obviously more concerned with being entertaining than with drawing out any solid information about the films. He kept asking the guests what inspired them to make their films, while very little got said about the films’ innovative techniques and the challenges the filmmakers faced–in short, about the films. Despite this obstacle, the guests managed to say some interesting things. There was obviously no audio recording either, so I frantically took notes.

One motif that cropped up several times was the fact that this year’s nominees included three stop-motion films. But as some of the animators emphasized, despite their love for the slow, frame-by-frame manipulation of puppets and objects, they do mix in new technologies. Fell described himself and fellow director Butler as “Luddites who’ve embraced the loom.” For example, although ParaNorman‘s young witch Aggie was animated as a puppet, her dress was an added digital effect. As Butler said, although they basically work with puppets, they will use whatever animation technique will look best on the screen. (Earlier this month, I discussed the use of color laser printing that made the wide variety of character expressions possible.)

Lord twice mentioned the convivial atmosphere created at Aardman’s Bristol studio, where people who love puppet animation have come together as a team. They avoid computer animation whenever possible, preferring “the lovely, amazing toys in the world, stuff the animators work with at Aardman.”

Fell and Butler described their influences as the horror films they saw during their childhoods in England. Butler had watched Night of the Living Dead at age 6, and Fell referred to “video nasties,” as they are labeled in England, very violent films that were banned or at least difficult to see. The age of VHS made such films as Driller Killer available, as Fell pointed out, though Butler hastened to point out that that particular film had not influenced ParaNorman.

Moore, who had directed episodes of both The Simpsons and Futurama, made Wreck-It Ralph as his first feature. Asked the difference between episodic animated TV and features, he responded that in features, characters move through an arc that changes their situation by the end. In TV, the characters start at square one, play out an action, and end up on square one by the end, ready to do the same thing the following week.

Burton was asked the difference between the original Frankenweenie short and the feature. Because the feature was animated, he considers it “a more pure version” of the original live-action short. In working on the style of the set designs for the feature, he went back not to the short itself, but to the drawings he had originally done for it. He also admitted that during the early days when he was had a job at Disney drawing cels for The Fox and the Hound (1981), his drawings of the fox looked “like road kill.”

Interlude: Ground Zero, the Dolby Theatre

The grand theater on Hollywood Boulevard where the awards ceremony takes place may now be named the Dolby, but it remains the Kodak Theatre on Google Maps and in the minds of the many who still call it that. Then again, I heard people at one of the Academy panels refer to “Grauman’s Chinese Theatre,” despite that fact that the Mann’s chain acquired it decades ago and it has again changed hands.

I was staying in the Hilton Garden Inn, on Highland Avenue a few blocks north of where it intersects Hollywood Boulevard at the corner dominated by the Dolby Theatre’s huge complex. Having a free morning on Friday, I wandered down, looking to take some pictures of the Oscar preparations.

The Dolby Theatre is also a shopping mall. It is surely the only mall in the world modeled on the work of D. W. Griffith, specifically his Babylon sets from Intolerance. Giant white elephants on pillars loom over tourists. (Top, and at left, a view looking toward the back of the complex from the north.)

Naturally the block of Hollywood Boulevard in front of the theatre was closed to traffic. Online one could find a complicated schedule of road and even sidewalk closings that went on for as much as a week before the day of the ceremony. Fortunately on this day the sidewalks were still open, so I could join the tourists watching the preparations and snapping photos. The bleachers had been installed, as had the famous red carpet. A larger nearby parking lot was filled with trailers sprouting satellite dishes. The infrastructure for this event is vast, as one would imagine. It’s also far from glamorous.

“Oscar Celebrates Foreign Language Films”

On Saturday morning I got to the Samuel Goldwyn Theatre earlier, about 8:30 am for a 10:00 event. This time I was among the first twenty-five or so in line and got an excellent seat in the third row opposite the podium. Mark Johnson, who until recently ran the foreign-language category, was the MC. David and I have known Mark for years, since the early 1970s, when we were all in graduate school in film studies at the University of Iowa. Between his film education and extensive work in the industry (including producing the Chronicles of Narnia films, Rain Man, Galaxy Quest, A Little Princess, and Breaking Bad), Mark was an excellent choice to host the event, as he had done several times in past years.

All the directors showed up: Michael Haneke for Amour; Kim Nguyen for War Witch; Pablo Larraín for No, Nikolaj Arcel for A Royal Affair; and Joachim Rønning and Espen Sandberg for Kon-Tiki. (I discussed No and A Royal Affair in a report from the Vancouver International Film Festival last year.)

As each director came onstage, Mark graciously asked him to acknowledge any members of his filmmaking team who were in the audience. These included three of the four producers of Amour, Stefan Arndt, Veit Heiduschka, and Michael Katz. When Mark asked where the fourth producer, Margaret Menegoz was, Haneke got off the first zingy of the evening, saying that she would be arriving that evening: “She was picking up the Césars.” (On Friday, Amour won five, for best picture, director, original screenplay, actor, and actress).

Mark’s excellent questions solicited much information. I can’t summarize it all, but here are some highlights, film by film.

Arcel emphasized how difficult it was to finance A Royal Affair, given that it was a big, expensive costume picture: “It’s a risk in Denmark, where we have more the kitchen drama.” Although Zentropa Productions made the film, there was considerable investment from other European countries. One of the film’s stars, Mikkel Boe Følsgaard, was an acting student when he was cast as the eccentric Danish king, and he won the best actor prize at Berlin. Arcel revealed that after making A Royal Affair, Følsgaard went back to resume his acting-school education, where the next unit was on film acting. A Royal Affair was the only nominee shot on 35mm. Rather than following the European art-cinema tradition, he was influenced by his favorite Hollywood films, like Gone with the Wind and Lawrence of Arabia.

No was the third film in a trilogy about the Pinochet years in Chile, the earlier ones being Tony Manero (2008) and Post Mortem (2010). Mark asked Larraín if he had initially planned a trilogy. He said no, “I would say it is mostly the press who have named this a trilogy.” On the other hand, he thinks the term makes sense when applied to these films, and he has no objection. He commented that the film depicts how the same tools of propaganda Pinochet used on the people were turned against him. Rather than staging a violent takeover, “They put him out with the tools of beauty.” His filmmaking team had intended the lead role for Gael García Bernal from the start, despite his being a Mexican actor. The other actors had been with Larraín on previous films and all are well-known in Chile.

Larraín also talked about the four 1983 video cameras that were used to simulate older footage, each of which produced footage with a slightly different look. The team was worried about the various shots not cutting together smoothly with each other and with the archival footage that was integrated into the film. During editing, however, they began to forget which footage was new and which was archival and realized that they were succeeding. “What we shot became documentary, and the documentary shots became fiction.”

Nguyen talked about casting War Witch. Seventy-five per cent of the cast were non-actors. Rachel Mwanza, who played a young African girl forced to serve as a child soldier, was recommended by some documentarists who had filmed her as part of a group of homeless street kids; she had been abandoned by her parents at age 6. The film was shot with an Alexa. Tires constantly burning in the streets of Kinshasa created a haze that the filmmakers used as a filter for the natural light. Nguyen read many autobiographies of child soldiers as models for the voiceover narration in the film.

Rønning and Sandberg were inspired by the story of Thor Heyerdahl’s raft voyage from South America to Polynesia in 1947. Heyerdahl was a national legend, and his documentary record of the trip, Kon-Tiki (1950), won the only Oscar so far awarded a Norwegian film. Heyerdahl’s life was extremely well-documented in his diaries, which guided the scriptwriting. The filmmakers were lucky enough to gain access to a replica of the original raft, which had been made by Heyerdahl’s grandson to repeat the original voyage. The shooting at sea lasted for a month. In addition, however, there were over 500 special-effects shots–making Kon-Tiki, like A Royal Affair, a big-budget, Hollywood-style film. The directors said that with so much drama on TV, they wanted to create an epic that cried out to be seen on a big theatre screen. The effects were mainly for creating sharks and other creatures, extending sets, and occasionally erasing boats or shorelines in backgrounds.

Mark pointed out to Haneke that a lot of Americans know Amour is good but avoid seeing it because they think it’s too grim. Haneke blamed the American media for giving that impression of the film, saying that he considers it to be about love rather than death. But with a smile he also admitted, “I’m afraid it’s partly my fault.” He has gotten a reputation “for inflicting pain on audiences.” From the start he had planned the film around Jean-Louis Trintignant and would not have made it had he refused the part. Emmanuelle Riva, however, he found through the conventional casting process of auditions.

Mark mentioned the fact that the film juxtaposes wide views with close-ups, with few camera distances in between. Some scenes play out in a single long shot. Haneke responded “I want to give my audience time to reflect […] I try to manipulate the audience as little as possible.” Mark pointed out that in spite of this, the spectator always knows where to look. Haneke replied: “It’s all a question of craft.” (This drew applause from the audience.) The apartment in the film was a set, a choice made mainly because the older actors could not work long hours in difficult circumstances. The views seen through the windows were added with computer effects. Haneke dislikes non-diegetic music in films, and so he writes characters who would naturally be playing or listening to music within the story. In the case of Amour, he chose all the classical music before writing the script.

“The Art of Production Design”

The AMPAS isn’t the only organization hosting events around the presence of so many Oscar nominees being in Los Angeles. Straight from the foreign-film event I went with our friend Jonathan Kuntz, who teaches film and television at Los Angeles City College and the University of California at Los Angeles, to the Egyptian Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard. There the Art Directors Guild, the Set Decorators Society of America, and the American Cinematheque were presenting a similar panel discussion on “The Art of Production Design.” Nearly all the nominees were present (with production designer listed first and set  decorator(s) second): Sarah Greenwood and Katie Spencer for Anna Karenina; Dan Hennah and set decorators Ra Vincent and Simon Bright for The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey; Eve Stewart and Anna Lynch-Robinson for Les Misérables; David Gropman and Anna Pinnock for Life of Pi (at right); and Rick Carter for Lincoln (set decorator Jim Erickson couldn’t attend). The co-moderators were Thomas A. Walsh, Production Designer and Co-Chair ADG Film Society with Academy Governor Rosemary Brandenburg, SDSA.

decorator(s) second): Sarah Greenwood and Katie Spencer for Anna Karenina; Dan Hennah and set decorators Ra Vincent and Simon Bright for The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey; Eve Stewart and Anna Lynch-Robinson for Les Misérables; David Gropman and Anna Pinnock for Life of Pi (at right); and Rick Carter for Lincoln (set decorator Jim Erickson couldn’t attend). The co-moderators were Thomas A. Walsh, Production Designer and Co-Chair ADG Film Society with Academy Governor Rosemary Brandenburg, SDSA.

Greenwood stressed how little time there had been to prepare the sets for Anna Karenina. The production at first was intended to be a conventional version, and location-scouting was done in Russia. The team decided to shoot in London, but there was no unifying conception until twelve weeks before principal photography director Joe Wright decided to stage the action in a set representing a theatre. There ended up being twelve days to actually construct the set, with the designers marking the sets in chalk on the floor and starting to build before there were drawings of them. She describes the theatre set as “rich but minimalist,” since the approach was to remove as many items as possible.

Hennah answered a question from the audience concerning where conceptual design, done for The Hobbit by illustrators John Howe and Alan Lee, ends and production design begins. He responded that conceptual design involves creating the environments as a whole, as if they were real places. “The production design kicks in in terms of what takes place in the parts of that set.” The sets were drawn digitally and then built as 3D models that went to the pre-viz department. Howe and Lee worked in at Weta Digital rather than in the art department, as did an assistant art director. Vincent and Bright both consulted on the color grading, among other roles.

Hennah spoke of the design of the huge Goblin Town set. He conceived it as having been built within a great diagonal rift inside the mountain caused by an earthquake. The Goblins being thieves, they constructed the buildings and bridges out of random stolen items like carts. The layout of the Dwarves kingdom within the Lonely Mountain derived from the idea that the space expanded randomly as the workers removed stone to follow veins of gold.

According to Stewart, the filmmakers did not try to make Les Misérables a faithful reproduction of the stage play. They wanted to do what the stage version couldn’t: “You can’t see big wides and you can’t see up people’s nostrils.” Hence the film utilized sweeping cityscapes with huge buildings and crowds, while the musical numbers are filmed in relentless close-ups. Tom Hooper likes to “make things up on the day,” so Stewart had to make the sets bigger than usual, since she couldn’t plan ahead for what he might improvise during filming.

Given how much of Life of Pi was shot in tanks, what did the designers have to do? Gropman explained that they designed the interior of the Indian house where the early part of the story is set, with the interiors being constructed in Montreal and the exteriors shot in India. The apartment in the frame story had to be simple and bland, so that it would not reflect the character at all. Since the film was not shot in continuity, a big challenge was keeping track of the deterioration of the lifeboat, which becomes more worn and damaged.

Given how much of Life of Pi was shot in tanks, what did the designers have to do? Gropman explained that they designed the interior of the Indian house where the early part of the story is set, with the interiors being constructed in Montreal and the exteriors shot in India. The apartment in the frame story had to be simple and bland, so that it would not reflect the character at all. Since the film was not shot in continuity, a big challenge was keeping track of the deterioration of the lifeboat, which becomes more worn and damaged.

Gropman asked artist Haan Lee, director Ang Lee’s son, to design the raft that Pi builds, and he came up with the idea of the raft as a triangle. The island was based on a single huge banyan tree in southern Taiwan, which was filmed for a day and then built in the studio.

Carter described having spent part of a day in the White House in preparation for Lincoln, including being left alone in the evening in the Lincoln bedroom. He graciously emphasized the importance of the set decoration, by the absent Erickson, as the main aspect of the settings that makes an impression on the audience. Virtually every day during the president’s last year of life was heavily documented, and research informed the set dressings. The designers also spent much time in Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Confederacy, which Carter considered a city almost as much influenced by Lincoln as was Springfield, Illinois.

A member of the audience asked what effect 3D had had on the designers’ work. The two designers of 3D films gave similar answers. Gropman remarked, “There’s nothing you do where you’re not thinking about foreground, middle ground, and background. […] We’re creating the environment primarily for the actors.” Hennah’s response was, “It doesn’t change anything in terms of how you approach it. […] It’s about giving a feeling of depth and a feeling of separation, which you would do in the real world anyway.” In other words, 2D films have always had plenty of depth cues.

Afterward Jonathan introduced me to Rick Carter, a long-time friend with whom he had gone to school (Jonathan on the left, Rick on the right). He turned out to be the one from the group who won the Oscar the next evening.

The Hobbit, win or lose

TheOneRing.net’s celebration of The Hobbit‘s three nominations (production design, makeup and hairstyling, and visual effects) began on Friday night with an art show. I was one of many volunteers helping out with setting up that and the Sunday night party, so I ventured into the labyrinth of old warehouses east of downtown, an area now established as an arts district.

The show drew some major exhibitors, including veteran Tolkien illustrator Tim Kirk, seen above posing with his most famous paintings. I was also delighted to meet some fellow TORn staff members whom I had previously only known from the group email messages we exchange and from their postings on the site. They’re an enthusiastic group who all work on a strictly volunteer basis.

The big event was on Sunday at the Hollywood American Legion hall (at bottom, the entrance, with a representation of the Arkenstone above the door and a life-sized Gollum statue lurking inside to provide a photo op). I helped out with the setup that morning, hanging signs and folding a great many “One Expected Party” T-shirts to be sold in the “Rivendell” room (aka the shop).

The main auditorium, dubbed “The Hall of the Elven-King” for the occasion, was where most of the celebrants gathered to watch the Oscars on a vast TV screen. If they turned around, they would notice that a full sized cave troll from The Fellowship of the Ring was watching along with them:

I managed to watch the first half of the show but then was slotted to help sell T-shirts and CDs by the band that would be playing after the Oscar show ended: Billy Boyd’s “Beecake.” I was there long enough to sit through two of the categories for which The Hobbit was nominated and to be nearly deafened by the cheers–and then groans of disappointment. The fans reassure each other that as with The Lord of the Rings, the third part will scoop up Oscars serving to reward the whole trilogy.

Being in “Rivendell” selling stuff, I missed the second half of the show, but I gather that was not much of a loss. The Oscar fever being exhibited elsewhere in the building and around town turned out to be more interesting than the ceremony itself.