A matter of ‘Scope

Thursday | April 7, 2011 open printable version

open printable version

Killer Constable.

DB here:

Like most cinephiles of my vintage, I love anamorphic widescreen, especially in its early years. Even though CinemaScope as a trademarked format is long gone, its aspect ratio of 2.35 or 2.40 to 1 became the standard, and we tend to call any widescreen film of those proportions a “‘Scope” production.

Nowadays many films are in ‘Scope; it’s sensed as a cool ratio. Too cool, actually: I’m not sure that Cop Out and The Hangover needed to be in ‘Scope. Things were quite different in Asian cinema during the 1960s and 1970s, where directors had to learn how to master and exploit the new acreage available to them. I was reminded of their problems, and some of their dazzling solutions, when I visited films that were part of two big retrospectives at the Hong Kong Film Festival this year.

The Shochiku touch

Festival goers tend to ignore their cities’ round-the-year programming. We’ve shown films at our Cinematheque that would have drawn more strongly if they had been presented under the umbrella of a festival. A festival is a big, ballyhooed event, and people set aside time to plunge into it. They take it as an occasion to explore cinema. But that impulse isn’t as strong, I think, in other seasons.

Accordingly, the HKIFF has developed a smart strategy. It often launches a retrospective during the festival period but then continues it after the festival is finished. This enables the festival to spotlight the series more vividly and to engage viewers to return in the weeks to come. The drawback is that the strategy tantalizes us visitors, who wish we could stay on to get a full dose of Shimizu Hiroshi (subject of a 2004 roundup) or Kinoshita Keisuke (2005) or Nakagawa Nobuo (2006). This year’s hors d’oeuvres were even more scanty: only two of the films of Shibuya Minoru played during the festival, which ended Tuesday. The rest come later in April.

At the venerable Shochiku studio, after assisting Naruse Mikio and Gosho Heinosuke, Shibuya worked with Ozu on What Did the Lady Forget? (1937) before launching his own directing career. He made over forty films, the last one released in 1966. My own awareness of Shibuya before my visit was limited to the family dramas A New Family (Atarashiki Kazoku, 1939) and Cherry Country (Sakura no kuni, 1941), both in a mildly, though not rigorously, Ozuian vein.

At the venerable Shochiku studio, after assisting Naruse Mikio and Gosho Heinosuke, Shibuya worked with Ozu on What Did the Lady Forget? (1937) before launching his own directing career. He made over forty films, the last one released in 1966. My own awareness of Shibuya before my visit was limited to the family dramas A New Family (Atarashiki Kazoku, 1939) and Cherry Country (Sakura no kuni, 1941), both in a mildly, though not rigorously, Ozuian vein.

The earlier film in the partial Shibuya retrospective was Righteousness (1957), an ensemble piece about a neighborhood still laboring under postwar hardships. The young Seitaro is in love with Michiko, but her mother offers her in marriage to her more prosperous roomer. Seitaro works as a mechanic for a bus company, where Fujita is a driver. Fujita has just married a young woman against his father’s wishes. The characters are introduced through the peripatetic Okyo, Seitaro’s mother, who peddles black-market goods to her neighbors. Fujita’s troubles mount up when his bus hits a child, and Seitaro must decide whether to reveal what he knows about the accident. The film builds well to two climaxes, the consequences suffered by Seitaro after he makes his painful decision and then Okyo’s denunciation of her neighbors. On the other side of the ledger, Fujita’s domestic troubles are resolved rather abruptly and implausibly. Still, Righteousness exemplifies the classic Shochiku formula of smiles mixed with tears, capped by a more-or-less upbeat resolution.

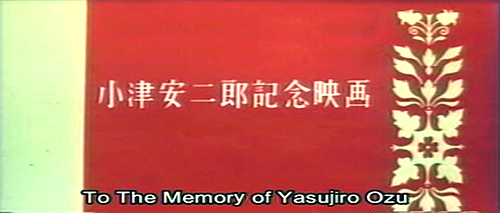

Shibuya was shadowed by Ozu even after the master’s death, for he was assigned to make a memorial film based on the last project planned by Ozu and screenwriter Noda Kogo. This was the film now circulating as Mr. Radish and Mr. Carrot (1965).

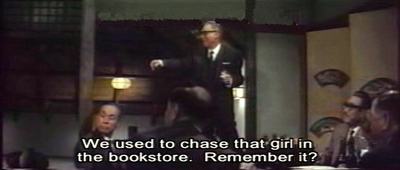

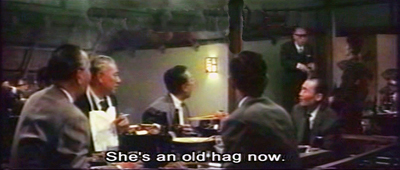

Chris Fujiwara has provided us an enlightening account of how Shibuya turned what would probably have been another subtle Ozu meditation on generational strife, in the manner of An Autumn Afternoon, into a more raucous comic melodrama. Yamaki is an executive who lives by strict routine, but he’s also pestered by his four daughters and his lothario brother. When a friend comes down with cancer and the brother reveals himself as an embezzler, Yamaki flees without warning. As his family fret about him, and quarrel among themselves, he settles in among working people, notably some prostitutes and a swindler selling Chinese medicine.

No one in the family displays much virtue, and even Yamaki is seen as cranky and oblivious to the needs of his wife and children. Radish and Carrot’s cynicism seemed to me too easy, and the physical comedy, such as Ryu Chishu’s bodily contortions, struck me as forced and overplayed. Stylistically, the film is eclectic and almost casual. It begins with a zoom and a whip pan. Thereafter, we get flash cuts, canted setups, and a fashion show. Unlike Righteousness, this film justifies Fujiwara’s claim, in a HKIFF catalogue essay not available online, that Shibuya sometimes embraced “visual excess.”

Ozu refused widescreen filming; he compared the ‘Scope frame to a roll of toilet paper. He may have realized that it would pose problems for his graphically matched cuts, deep and subtly imbalanced compositions, and other techniques he had refined over decades. Similarly, Radish and Carrot made me wonder if Shibuya was comfortable working in ‘Scope. He drops in some Ozuian corridor images, but at other times he mounts the sort of packed wide-angle shots common in 1960s Japanese anamorphic films.

When Ozu fills up his 4×3 frames, he gives us more to look at, along with more daring placement of figures. This is not your typical establishing shot.

Ozu’s signature shot is at a low height but seldom at a low angle. Shibuya’s compositions remind you what a real low-angle image looks like, with the camera tipped up considerably.

I know, it’s unfair to judge Shibuya’s film by the exalted standards of Late Autumn (1960), and we risk saddling him with purposes he didn’t have. He probably didn’t set out to make an Ozu pastiche. Yet we can, I think, fault Radish and Carrot sheerly on craft grounds. Two party scenes, one gathering men and one among wives, seemed to me almost haphazard in their spatial development. This cut, for instance, is more careless than anything I noticed in Righteousness.

In the second shot, on the far right side, a waitress is now in the frame next to the old man, and he has already turned and is talking to her instead of his classmates at the other table. When this film was made, younger directors, like Suzuki Seijun and Oshima Nagisa, were already handling ‘Scope with much more assurance. I look forward to seeing more Shibuya widescreen entries to learn if they made more polished use of the format.

Elegance and vulgarity

The other retrospective in question was devoted to Kuei Chih-hung (in Cantonese, Gwei Chi-hung), a Shaws director who has been overshadowed by the more famous Chang Cheh and Li Han-hsiang (here and here on this site). Kuei worked in several genres, including the sex movie and the horror film, and he was able to supply cheap items in quantity. But he stands out partly because he moved outside the opulent Shaw studio to shoot on locations. Working with an efficient crew and a lightweight camera, Kuei produced some films, like The Delinquent (1973) and The Teahouse (1974), that look forward to the social realism of the New Wave that followed. Like some New Wavers as well, Kuei highlighted the cruelty of class warfare in Hong Kong both past and present. Ironically, he ceased directing when he felt that the young generation had pushed things further than he could go.

The other retrospective in question was devoted to Kuei Chih-hung (in Cantonese, Gwei Chi-hung), a Shaws director who has been overshadowed by the more famous Chang Cheh and Li Han-hsiang (here and here on this site). Kuei worked in several genres, including the sex movie and the horror film, and he was able to supply cheap items in quantity. But he stands out partly because he moved outside the opulent Shaw studio to shoot on locations. Working with an efficient crew and a lightweight camera, Kuei produced some films, like The Delinquent (1973) and The Teahouse (1974), that look forward to the social realism of the New Wave that followed. Like some New Wavers as well, Kuei highlighted the cruelty of class warfare in Hong Kong both past and present. Ironically, he ceased directing when he felt that the young generation had pushed things further than he could go.

The crime-centered plots of The Delinquent, The Teahouse, and Big Brother Cheng (1975) manage a fair amount of outrage at policing and justice in Hong Kong, as do Kuei’s contributions to a series of omnibus films called The Criminals. His excursions into exploitation fare with Bamboo House of Dolls (1973), Killer Snakes (1974), and the Hex cycle (1980 and after) show, if nothing else, how anxious Shaws was to retain market share in the face of the thrusting popularity of Golden Harvest releases. Obliged to go gross, the man didn’t flinch. The Boxer’s Omen (1983), a supernatural kickboxing yarn, features one rite that demands that celebrants chew food, spit it out, and pass it along to be eaten by others. (No fakery, everything done in one shot.) My tastes run more to something like Killer Constable (1980).

It’s a shooting-gallery plot. Constable Leng and his team are sent to recover gold stolen from the Empress’s palace, and one by one the fighters are eliminated in skirmishes with the thieves. Kuei pointed proudly to the social criticism in the film: “I simply wanted to depict how insignificant commoners are and how, under totalitarian rule, they turn out to be the victims.” Leng, preferring to kill lawbreakers rather than bring them to trial, pursues the bandits with unblinking ferocity. When he finds a miller who helped the gang, he decapitates the man in front of his wife and squalling baby. But Leng’s brutality meets its match in the bandits, who devise comparably sadistic ways to decimate his posse.

Killer Constable comes near the tail end of the Shaws output, just a few years before the company largely abandoned theatrical film production in favor of television. Kuei is thus able to absorb and advance some of the studio’s signature techniques. His film starts out in the splendor of high-key lighting and saturated color typical of Shaws court epics, but soon enough, sword battles play out by torchlight or in semidarkness.

As for ‘Scope, Kuei had the benefit of a strong tradition. In action films, both Japanese and Hong Kong directors cultivated a “precisionist” use of the ratio that made parts of the composition–sometimes widely distant parts–click into place one by one, at a staccato pace. Here are phases of an early fight in Killer Constable.

The rhythm builds, from the cut to the new angle, then the peekaboo flip of the window, then the spotlighting of Leng in the lower right, and finally the thrusting hand of his victim in the extreme left, at which point the shot comes to rest.

‘Scope felicities like this may stem as much from the power of the tradition as from Kuei’s individual talent. In any case, his retrospective, like the Shibuya one, shows that we haven’t fully charted the range of expressive possibilities opened by popular Asian cinema in their early encounters with widescreen.

Chris Fujiwara’s survey essay, “Irony, Disenchantment, and Visual Excess: The Style of Shibuya Minoru,” appears in the HKIFF catalogue, available here. In Chapter 12 of Poetics of Cinema, I illustrate Japanese filmmakers’ relative laxity about the 180-degree matching system with a couple of shots from Shibuya’s A New Family. The passage in question may be one-off borrowing from Ozu.

The Hong Kong Film Archive book devoted to Kuei Chih-hung provides precious information not only on the director but also on the Shaws studio system. For more on widescreen style at Shaws see my online essay, “Another Shaw Production: Anamorphic Adventures in Hong Kong.” I discuss the rhythmic resources of Hong Kong combat in Chapter 8 of Planet Hong Kong.

Other continuing retrospectives at this year’s HKIFF are devoted to Abbas Kiarostami and Vietnamese cinema from 1962-1989. If you’re passing through town, you could do worse than check them out.

Thanks to Li Cheuk-to for correcting some information.

Opening title for Mr. Radish and Mr. Carrot.