Archive for the 'National cinemas: Middle East' Category

Seduced by structure

Mysteries of Lisbon.

DB here:

If you’re hungry to learn about the ways films can tell stories, a festival provides a feast. A huge array of narrative strategies is spread out for your delectation. You won’t like every movie you see, but thinking about the mechanics of each one can deepen your experience of it, as well as your appreciation for just how wide cinema’s resources can be. You also get to see how more unusual approaches to storytelling are often imaginative revisions of more traditional strategies.

We can usefully think about narrative from three angles. We can study the story world that a film conjures up: the characters, places, and actions we encounter. We can analyze plot structure, the distinct parts that are put together sequentially. They might be scenes or sequences or larger-scale parts, like the Hollywood screenwriters’ “acts.” We can also analyze narration, the patterned, moment-by-moment process of presenting the story world and the plot structure. Think of a narrative as like a building. The building’s furnishings correspond to the story world, and the architectural design of the building, plan and elevation, is like plot structure. Our real-time pathway through the building, from the front doorway into its depths, corresponds to narration.

The Vancouver International Film Festival that Kristin and I have been visiting offers a banquet of storytelling devices—some quite traditional, some fairly fresh. I’ll just survey some aspects of structure that I found intriguing.

The longest distance between points

The Chinese blockbuster Aftershock, centering on the 1976 earthquake that struck Tangshan, has earned some complaints about weepiness and jokes about “Afterschlock.” Perhaps melodrama makes many critics uncomfortable. They seem more at home with comedy and noirish crime stories, perhaps because the emotions stirred by these are bracketed by a degree of intellectual distance. But tell a story about a happy family split apart by a catastrophe; show a mother forced to choose between saving her son and saving her daughter; show that the girl miraculously escapes death; present her raised by a pair of new parents; and dwell on the fact that her mother, living elsewhere, expects never to see her again—do all this, and you court mockery.

Well, mockery from everybody except the hundreds of thousands of people who have always enjoyed these situations. Aftershock is now the biggest box-office success in Chinese film history (presumably using today’s currency standards). Whatever the film owes to Chinese traditions, it is easily understandable in a Western context. Stories based on pseudo-orphans, separated siblings, and parents forced to give up children have long been sure-fire. Les Deux orphelines, an 1874 play, is one strong prototype. This pathetic tale of two sisters torn apart in post-revolutionary Paris was adapted by many directors, including Griffith (Orphans of the Storm, 1921). Feuillade developed similar motifs in Les Deux gamines (1921), L’Orpheline (1921), and Parisette (1922). A mother’s loss of her children through accident or social oppression is another stock situation, seen in sublime form in Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff. The obligation to pick a child to save is at the core of Sophie’s Choice, a more highbrow melodrama. Likewise, the discovery of unexpected kinship forms the climax of many stories, from Oedipus Rex to Twelfth Night and beyond.

You may call these conventions hackneyed, but it would be better to call them tried and true—proven effective by centuries of deployment, counting on emotions aroused by ties of love and blood. Such situations would be good candidates for narrative universals, which can be reshaped by local cultural pressures.

The premise of a fragmented family bears chiefly on the story world. The filmmaker still must choose how to structure the plot. For Aftershock, director Feng Xiaogang and his collaborators settled on the time-honored route: parallel stories across the years, shown by means of crosscutting. After the quake, scenes of the mother and son alternate with scenes showing the girl’s rescue and her life with her adopted parents, both soldiers in the People’s Liberation Army. For about the first sixty minutes, the segments are rather long, but after that shorter scenes from each plot line are intercut. The son moves off to a separate life, but his success as an entrepreneur is given short shrift. The plot concentrates on the daughter’s college career, her sometimes stormy relation with her foster parents, and her unexpected pregnancy. In the meantime, the mother survives, turning aside a kindly suitor in order to preserve her faithfulness to the husband who saved her life.

Narrationally, the alternation between the separated characters gives us superior knowledge. We know, as the mother and brother do not, that the daughter survives; we also know that she nurses a bitter memory of hearing her mother choose the rescue of her brother. Likewise, we know that the mother has tormented herself for decades over her forced choice. Thus the recriminations that will burst out after they rediscover one another will require some healing, which is provided in the plot’s last phase. Melodrama depends on mistakes, and they must be corrected. In a telling image of two sets of schoolbooks (not previously shown to us), we and the daughter realize that over the years the mother has been thinking of her as if she were still alive.

The dual structure can also tease us with suspense. At the hour mark, we learn that both the brother and the daughter are in Hangzhou, without each other’s knowledge. The brother even encounters the foster father. It’s the sort of coincidence that leads us to expect a reunion. Coincidences, I mentioned in an earlier entry, are fascinating narrative devices, and here the fortuitous convergence doesn’t actually pay off. But it does prepare us for the genuine reunion that will take place an hour or so later, when an earthquake hits Sichuan in 2008.

There’s a lot more to be said about Aftershock; I was struck by the fact that the children are left in the collapsing apartment because the parents have sneaked off to have sex in the husband’s truck. (So is the whole arc of suffering the punishment for a little carnality?) But just sticking with structure, we find that a cluster of ancient plot devices, fed into the established technique of crosscutting, can still find purchase in a contemporary film. In films like Aftershock, as in Hollywood’s romantic comedies and horror films and historical adventures, very old narrative conventions live on. Suitably spruced up with CGI, they still provide pleasure.

Sometimes, however, you get the sense that filmmakers in other cultures are borrowing conventions of recent Western films. This seems the case in City of Life from the United Arab Emirates. Faisal is a spoiled playboy who spends his nights with his pal Khalfan, a fistfight-prone club-hopper. Natalia is a Romanian flight attendant who gets romantically involved with an advertising man. Basu is a taxidriver with an uncanny resemblance to a Bollywood star, and so he tries to supplement his earnings by appearing in a nightclub. As all of them move through Dubai, their lives intertwine.

We have, in short, what I’ve called a network narrative. Mostly the plot lines are juxtaposed through crosscutting, but sometimes the characters in one line of action encounter those in another. Faisal is at a club on the same night as Natalia is there, with her boyfriend and her roommate. Objects circulate as well. Natalia pays Basu for a cab ride, and Basu preserves her €20 note until he has hit rock bottom. At the midpoint, an ad campaign links Natalia’s boyfriend, Faisal’s father, and Basu’s job. Many of the conventions of the “small world” network format are included, with one character remarking that Dubai is a small city. Our old friend the traffic accident (shot and cut with exceptional vividness) plays a crucial role. A refuse collector threads through the plot, turning up at unexpected times and providing an ironic coda.

Director Ali F. Mostafa mobilizes a lot of contemporary techniques, including fast motion and rapid cutting (3.6 seconds average shot length). The editing sometimes extends the crosscutting principle by flipping back and forth between two successive scenes, creating little flashforwards. For instance, when the adman Guy phones Natalia to introduce himself, we cut to them talking in a bar and then back to her listening to his sweet talk.

The anticipatory cuts lead us to expect that Guy is calling to ask her out, and Natalia will accept. This sort of cross-stitching can be found in The Godfather and other films of the late 1960s and early 1970s, and it has shown up sporadically since, but it’s rare enough to still look modern.

In cinema, network narratives can occasionally be found before the 1990s, but they’ve become far more common. I count nearly 150 films of the last twenty years employing the structure. In literature, of course, such plots go back quite far, and they formed the basis of nineteenth-century novels by the likes of Balzac, Dickens, Zola, and George Eliot. Television soap operas and ensemble series like Hill Street Blues showed that modern media’s long-form formats fit well with network storytelling. So cinema has caught up, adjusting the template to feature-length plots. City of Life shows that artists from emerging filmmaking nations can use this structure to enter a festival circuit dominated by Western norms of construction. At the same time, those artists can tailor this structure to their own ends—in this case, it seems to me, presenting Dubai as a city of emigrants ruled by a feckless leisure class.

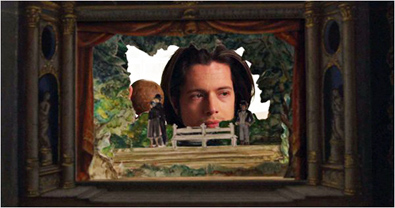

The theatre of memory

What happens, though, when conventions of sprawling nineteenth-century novels aren’t squeezed so drastically into the usual feature length? I had a chance to find out from Vancouver’s screening of Raul Ruiz’s four-and-a-half-hour Mysteries of Lisbon. Based on an 1854 novel by Camilo Castelo Branco, a fictioneer as prolific as Ruiz himself, the film doesn’t trim off the exfoliating plot lines that we enjoy in three-deckers from the period. This being a Ruiz film, there is as well a tangible pleasure in the artifice of storytelling. The film acknowledges that all the handy coincidences, buried pasts, multiple identities, and revelations of kinship are there for our delectation.

Orphans again: João is being raised in a church school, but he has no idea of his parentage. Early on, kindly Father Dimis tells him that his mother is Angela, the countess of Santa Barbara, but her brutal husband is not his father. We are soon embarked on the extended flashback that traces the doomed love affair that results in the birth of the young hero, now named Pedro. In the course of that tale, we meet two more suspicious characters, the gypsy Salino Cabra and the hired assassin Heliodoros.

This recounted history is only the first of a cascade of flashbacks, issuing from several characters, and these gradually show deep connections among persons tied to Pedro’s past. Secondary characters in one story become protagonists of another. The young hero is gradually displaced as the center of the action by war, secret romances, rivalries, duels, and infidelities. Like Pasolini in his Trilogy of Life, Ruiz is happiest when opening up a plot detour that will eventually become a new main road.

By the end, our young hero has become something of a nullity, an empty center around which aristocratic ecstasies and follies have swirled. He’s something like the Dubai of City of Hope: a point of intersection of many fates. He’s also a passive observer of scale-model dramas played out on his toy theatre stage. His voice-over narration has enwrapped the whole film, and our last glimpse of him is as merely a narrator. Pedro seems finally to realize that his entire existence has served simply to gather other people in a tangle of doomed passions.

Mysteries of Lisbon has a rich, high-thread-count look, but it’s not your usual prestige costume drama. The long takes cling to characters as they flirt their way across a ballroom, and the camera slips through walls in the manner of old-fashioned cinema. There are the usual Ruiz flourishes of hallucinatory deep focus (achieved through split-focus diopters), characters floating rather than walking, and the occasional peculiar angle. But the film remains calm and lustrous, culminating in a slow tread into pure light.

Mysteries of Lisbon has a rich, high-thread-count look, but it’s not your usual prestige costume drama. The long takes cling to characters as they flirt their way across a ballroom, and the camera slips through walls in the manner of old-fashioned cinema. There are the usual Ruiz flourishes of hallucinatory deep focus (achieved through split-focus diopters), characters floating rather than walking, and the occasional peculiar angle. But the film remains calm and lustrous, culminating in a slow tread into pure light.

Ruiz’s appetite for narrative is almost gluttonous; he supposedly wrote over a hundred plays in six years, and he’s made about as many films. He once told me that he thought that Postmodernism was simply a revival of the Baroque in modern dress. From Mysteries of Lisbon, it’s clear that he sees in many older narrative traditions affinities with our tastes today. Network narratives? They’ve been done, and maybe better, centuries ago. Follow the lacy tendrils of classic family-origins plots, and you’ll find a pattern as intricate as anything in Short Cuts or Pulp Fiction. More story ahead: there’s a six-hour television version.

Rumination on ruination

Ruiz understands that modernist narrative techniques, including unreliable narrators and fancy time-switches, depend upon a long tradition in at least two ways. First, very often the tradition got there first; scholars like Meir Sternberg and Robert Alter have demonstrated complex plays with chronology and point of view in the Bible and the Greek classics. Secondly, unusual plot structures may ring unexpected variations on more conventional ones. Case in point: reversed plot sequence.

Again, this seems to be something of a modern trend. The locus classicus appears to be Harold Pinter’s 1978 play Betrayal, in which, scene by scene, the plot proceeds in reverse chronology. This was filmed in 1983 and gave birth to a famous Seinfeld episode. As you know, Memento, Irreversible, and other recent films have taken up reverse-chronology plotting. Actually, however, there are several earlier instances, notably the 1934 Kaufman and Hart play Merrily We Roll Along (turned into a musical by Stephen Sondheim) and W. R. Burnett’s 1934 novel, Goodbye to the Past. Other examples, some going back quite far, are listed here.

Rumination, a film by Xu Ruotao in the Dragons & Tigers young directors competition at Vancouver, turns the structure to political ends. Reduced to the bare bones, the film shows a teacher, his wife, and their son caught up in the Chinese Cultural Revolution. The father falls in with a gang of Red Guard youths rampaging through the countryside. The son trails the gang at a distance and occasionally interferes with their acts of violence. These story events are arranged in blocks, with each cluster of scenes associated with a specific year. The blocks proceed backward in time, from 1976 to 1966. After a prologue, the film shows scenes of the waning of the Revolution; before the epilogue, we get a stalwart young man announcing the Revolution’s birth.

The scenes are fairly episodic and independent, so I didn’t detect the backwards structure for quite a while. But my uncertainty had another source. Xu introduces each year’s scenes with a date that is, except for one instance, not the year of the actions shown. In fact, while the segments move in reverse order, the years’ designations move in chronological order.

The opening 1976 section is labeled 1966, the 1975 section is labeled 1967, and so on up to the end, with the 1966 action designated as 1976. So we see the father’s reunion with his wife, a moment of clumsy embrace, long before he decides to leave home. As you’d expect, there’s one year in which the action and the tag coincide, 1971, and that is the only one built out of photos and film clips from the period. The year is privileged, Xu explains, because that was the year of the mysterious plane-crash death of Lin Biao, a military hero and Cultural Revolution leader who was accused of plotting Mao’s assassination.

In my viewing, the misleading dates helped conceal the reverse chronology. Confronted with so many discrete episodes of unidentified characters sprinting through the countryside, beating passersby and stealing chickens, I took the default option and assumed that the segments were chronological. Moreover, the film’s scenes play out almost entirely in overcast landscapes and decrepit factories, a landscape in which I couldn’t detect any indications of change from year to year. Watching Ruination a second time, I saw the reversal more clearly, but I also thought that some segments tease us into thinking along chronological lines. An early scene shows the father getting up in the morning (a conventional way to start a plot), saluting Chairman Mao’s statue, and reading from the Little Red Book. Yet this scene is set in 1975, after the father has returned to his wife from his Red Guard period.

Moreover, there’s some evidence that the son actually matures across the film, even though the scenes show him objectively getting younger. By the end of the plot (the earliest moment in story time) he seems to have transformed himself into a strapping young Red Guard. Supporting this construal is the fact that in the Q & A after the showing, Xu mentioned that one influence on his film’s design was The Curious Case of Benjamin Button!

Xu explained that the tragedy of the Cultural Revolution could not be comprehended through normal storytelling techniques. I suspect that viewers familiar with the relevant events and the film’s slogans, iconography, and oblique citations (even to Godard) could follow the backwards sequencing. But I suspect that those viewers would need a sense of the historical chronology to grasp the 3-2-1 order of the plot. It seems to me that Xu, known until now as a painter, has shown how an innovative approach to plot structure relies on conventional responses even as it thwarts them.

Hahaha indeed

Hong Sangsoo has been one of the leading experimenters with narrative in today’s Asian cinema. My two favorites, The Power of Kangwon Province (1998) and The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (2000) have engaged the viewer in playful puzzlement about how story lines can collide or slip sideways, how our memory of earlier scenes’ action can be tested and found faulty. I haven’t been deeply engaged by his recent forays into more straightforward drama/comedy, such as The Woman on the Beach (2006), but his two latest features, both from this year and both on display in Vancouver, completely satisfied my hunger for intriguing plot structures.

It’s an unspoken convention of recounted-flashback tales that even though the events are told by A, B learns everything that we do—everything, that is, that we can see or hear in the flashback. But Hahaha decouples the verbal recounting from the visual presentation. Here listener B definitely does not grasp what we witness happening onscreen in the tale as told.

Hahaha is a parallel-protagonist tale. Two pals meet for some drinking before one, Munkyung, leaves South Korea for Canada. Through a series of flashbacks, they regale each other with their recent adventures, mostly amorous. The plot is structured as two alternating streams, crosscutting one man’s tale with the other’s and usually returning to the framing situation of their drinking bout. But because we can see what each one recounts, we come to realize that both stories are populated by the same people, notably the tempting female tour guide Seongok. And those people have their own relationships, which we must piece together out of the glimpses we get in each man’s tale.

Neither Munkyung nor his pal Jungshik has a clue that they are part of a fairly tight circle. The result, as usual with Hong, is a comedy of ironic misunderstanding and the puncturing of male pretension. Hahaha can also be seen as his response to the rise of network narratives. Characters in such a film don’t usually realize the larger mosaic they’re part of; the intersecting lives in City of Life transform one another unwittingly. Normally that lack of awareness isn’t the main point of the film. Here it is, and it’s wrung for classic humor at the protagonists’ expense.

In Oki’s Movie, Hong gives us another fractured plot, but now in the form of four short films. They center on three characters: Song, a film director turned professor; his student Jingu; and Oki, the woman both men are interested in. The raggedy credits of each short suggest handmade movies, but what we see in each one is the polished style familiar from Hong himself, including his current interest in abrupt zooms.

The four-part structure is far from transparent. It might be taken as a series of episodes from the trio’s lives. The first film, “Specters of the New World,” which presents Jingu as a professor himself, would have to take place in the present, and the following three would then be presenting flashbacks to the Jingu-Oki-Song triangle. In that case, the first segment would prove that Jingu did not wind up with Oki, as he’s married to another woman.

Perhaps, though, all four films are free hypothetical variations on the central situation. I’m not sure that we can easily arrange the events in the second, third, and fourth episodes chronologically. The films could be presenting successive groups of events, or events scattered across a single time span and then selectively gathered around one of the central characters. The first episode is largely organized around Jingu’s range of knowledge; the second is confined to professor Song; and the third is explicitly presented as Oki’s own thoughts. Earlier Hong films have offered us contrasting, even incompatible plots built out of a core group of characters. Oki’s Movie may be using the framing conceit of student films (none of which is plausible as a student film) to give us a suite of variants on the love triangle.

The idea of ambiguous variation is made explicit in the final mini-film, “Oki’s Movie.” It’s a sustained exercise in—yes, again—crosscutting. This episode alternates two excursions to Mount Acha, one with each man. Shot by shot, we see different courtship styles and we hear her differing reactions to her two lovers. Was she dating both men at once? When did the two excursions take place? Which one occurred first? As these questions are juggled, we get a rapid checklist of Oki’s attitudes, in voice-over, toward both these minor-key losers.

In both Hahaha and Oki’s Movie, Hong takes what’s offered by tradition—in this case, the romantic comedy and the conventions of flashbacks, crosscutting, and restricted narration—and creates a fresh structure. The play of novelty and norm is engrossing in itself, apart from the vagaries of the drama. Our appetite for narrative will always be whetted when directors find ways to whip up something new out of familiar ingredients.

For more on the three dimensions of film narrative, as well as discussion of the principles of network construction, see my Poetics of Cinema. There’s more discussion of flashbacks in film in this entry. On early narrative structure, see Meir Sternberg’s Poetics of Biblical Narrative and Robert Alter’s Art of Biblical Narrative, as well as Sternberg’s discussion of The Odyssey in Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction. For a sharp-eyed consideration of Oki’s Movie, see Andrew Tracy’s review at Cinema Scope.

Oki’s Movie.

ROW, take a bow

Of Love and Other Demons.

Kristin here:

There are dozens of American films playing at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year, but the vast majority of them are documentaries. Once again the Rest of the World (ROW) gets its turn. David has started by handling a group of Asian films (one of the festival’s specialities), and I’ve got films from three continents to describe.

Morgen (Romania; dir. Marian Crisan, 2010)

Morgen opens with the camera following the hero, Nelu, riding his motorcycle toward a border checkpoint. The border guards question him and discover that he’s been fishing and caught a large carp. One guard is inclined to let him pass, but the stricter one insists that he can’t take it across. We may think that this guard wants the fish for himself, but when Nelu finally empties his bucket into the gutter, the guards retire into their office and the fish is left to flap pathetically as Nelu rides across the border.

It’s a simple, obvious way to set up the absurdity and arbitrariness of border controls within the European Union, but it also sets up the character of the two guards, who will figure later when a more important border-crossing is attempted.

A security guard at a local grocery store, Nelu lives with her termagant wife in a modest farmhouse near the Hungarian border. During one of his regular fishing trips, he spots a forlorn Turkish refugee hiding from the border police. He takes the man home. Although the Turk’s dialogue isn’t subtitled, he mentions Germany often enough for Nelu and us to grasp where the man is heading. Not having a clue about how to help, Nelu hides the Turk in his cellar, and despite the wife’s objections, he gradually becomes a sort of handyman around the place. Nelu keeps telling him, “Morgen” (“tomorrow”) suggesting that he vaguely hopes to do something eventually.

Virtually every scene occupies a single take, some long, some not. But these aren’t the deliberately lugubrious shots of a Béla Tarr. In its quiet way, Morgen is a comedy, and an entertaining one. Nelu’s passivity presents the slowly growing friendship between him and the Turk without the film tipping over into sentimentality, and there is genuine suspense in the scenes of threatened encounters with the border police and guards. It’s a charming film, reminiscent of some of the Czech New Wave comedies of the 1960s.

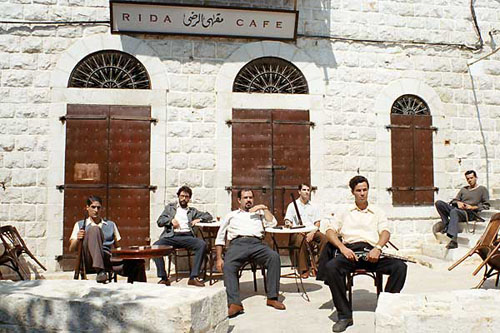

12 Angry Lebanese: The Documentary (Lebanon; dir. Zeina Daccache, 2009)

The film’s subtitle is intended to differentiate it from a play of the same name that was produced within the largest prison in Lebanon, starring a group of prisoners. In the United States the director, Leina Daccache, studied drama as a method of prisoner habilitation. She managed to get funding to try the first ever use of this method in Lebanon, though there followed a year of negotiations before government officials allowed the experiment. The  program was to include a loose adaptation of the American play 12 Angry Men, as well as some songs and monologues by the prisoners. Eight soldout performances were eventually put on, attended by government ministers and members of society.

program was to include a loose adaptation of the American play 12 Angry Men, as well as some songs and monologues by the prisoners. Eight soldout performances were eventually put on, attended by government ministers and members of society.

The process of casting and rehearsals took fifteen months, and Dacchache documented the process with a cinematographer shooting digital video. There are atmospheric shots of the prison, scenes of the rehearsal and premiere performances, and interviews with the prisoners who play the lead roles. The resulting images are necessarily not of high photographic quality, but the intrinsic drama of the situation more than makes up for that.

Although 45 prisoners were involved in the performances, Daccache wisely concentrates on the central dozen, composed of several murderers, some drug dealers, and a rapist. Even in the early interviews, before rehearsals have progressed very far, all are remarkably articulate and thoughtful about their own lives and how they ended up in prison. (Presumably they were chosen because they could speak so revealingly.) By the end, they realize that they have learned all the things they were deprived of during their early years, most notably how to function as a group and work toward a goal beyond their own wants.

The film creates a moving and convincing image of the effects art can have in changing the lives of prisoners thought to be beyond rehabilitation. It’s a rare documentary that has an immediate positive effect on society. In this case, there had been a law providing for early release for prisoners on the books in Lebanon for several years. As Daccache revealed in a Q&A after the film, that law was never put into practice until after the successful run of the play.

Of Love and Other Demons (Costa Rica/Colombia; dir. Hilda Hidalgo, 2010)

Filmmaking on a sophisticated level continues to spread through Latin America. Hidalgo’s adaptation of Gabriel García Márquez’s novella seems to have been shot in Costa Rica, with financing and other technical work done in Colombia.

The story is relatively simple. The teenage daughter of a local nobleman in colonial Cartagena is bitten by a rabid dog. It’s not clear whether she has contracted the disease, but she is taken to a local nunnery and locked away in a cell for observation. Somehow the diagnosis is changed to demonic possession, mainly because the girl has been raised by her family’s black slaves and has been steeped in their native, highly non-Catholic beliefs. A young, philosophically minded priest is sent to exorcize her but ends up falling in love with her instead.

In contrast to the slapdash editing so common in contemporary Hollywood films, it’s a pleasure to see a film where every shot has been intelligently planned. The Variety review compares cinematographer Marcelo Camorino’s lighting to Caravaggio paintings, an apt parallel. The heroine’s implausibly dense, waist-length red curls are lovingly dwelt upon, as in the shot illustrated at the top of this entry. The sense of magical realism emerges most powerfully in a dazzling sequence in which the priests watch a solar eclipse. A moon far larger than it would normally appear passes across an equally huge sun, creating a fiery corona that hovers above the open sea (see below).

Microphone (Egypt; dir. Ahmad Abdalla, 2010)

Ahmad Abdalla, whose first feature Heliopolis we blogged about last year, is back with his second. Microphone is much more polished, reflecting a longer shooting time and perhaps a bigger budget. The same lead actor, Khaled Abol Naga, returns as Khaled, a young man returning to his native Alexandria after seven years in the United States. Finding that the girl he had hoped to marry has decided to go abroad to do her Ph.D., he sets out to help set up a studio in a warehouse. Gradually he gets drawn into the more popular goings-on in the working-class districts, notably rap music, skateboarding, and graffiti art. After a hypocritical government arts bureaucrat promises funding and then reneges, Khaled sets out to stage a concert in the open air, only to be confronted by Islamic and police opposition.

While Heliopolis simply followed a set of disparate characters around the upscale Cairo suburb, Microphone has a more ambitious structure, flashing back to stages in Khaled’s disillusioning reunion with his ex-girlfriend–flashbacks that are presented out of order within the ongoing scenes of his growing interest in street art. The result has the sophistication of a modern festival film.

The film presents a grim take on government repression and censorship. Abdalla, on hand to answer questions, told us that we had seen the full version, which he fully expects will be cut by the Egyptian authorities. Even  though he shows the young street artists in a sympathetic light throughout, Abdalla does not avoid the fact that their work is wholly positive. There is a motif of Khaled opening his shutters each morning to a view of an aging yellow stucco building across the way; one morning he opens again to find the façade covered with a giant graffiti image.

though he shows the young street artists in a sympathetic light throughout, Abdalla does not avoid the fact that their work is wholly positive. There is a motif of Khaled opening his shutters each morning to a view of an aging yellow stucco building across the way; one morning he opens again to find the façade covered with a giant graffiti image.

Indeed, one audience member, a young man from Alexandria, objected to the portrayal of his beautiful home city as ugly, since the story is set mostly in poorer neighborhoods. Abdalla defended the approach, saying that the film is intended to portray a certain arena of life in the city realistically, with the incidents in the film being derived from stories recounted to him by the actual young artists who played themselves.

The film’s criticism of the Egyptian government may seem rather tame by western standards. Yet a telling change in the ending reveals how current are its concerns. There is a street vendor selling pop-music cassettes out of a cardboard box who returns at intervals as a motif, though he has little to do with the story. The film was to have had an upbeat ending involving the vendor. But in June, when the filming was still going on, the beating death of Khaled Said by two policemen outside an internet cafe in Alexandria took place. The filmmakers altered their ending, with police chasing the cassette vendor and starting to beat him. (The trial of the real-life policemen is ongoing and has every appearance of being a sham.)

The Man Who Will Come (Italy; dir. Giorgio Diritti, 2009)

This film dramatizes a set of massacres of villagers perpetrated by Nazi soldiers in the region around Bologna in 1944 in response to the people’s support of partisan troops. It’s a tale told through the eyes of Martina, a girl of about 9 who has been mute since her newborn brother died in her arms. (No points for guessing whether she regains speech by the end.) Since the main peasant family to which Martina belongs is fictional, there was no necessity to make her mute, and unfortunately the result is that she has very little personality. She is shown being bullied by some boys early on, which presumably is intended to make us sympathize more with her, though the choice of a pretty little girl as the point-of-view figure entails a pretty automatic sympathy on the audience’s part.

The film is largely episodic, with the life of the central peasant family and their neighbors being vividly conveyed as we see them at their tasks. At intervals, Nazis are seen near the village, and the partisans recruit young men and have some early successes. But since Martina understands little of what goes on around her, she has no particular goal, though eventually she gains one as the Germans begin the massacre and she is left to save another newborn brother. I found it difficult to keep track of the lengthy scene of the rounding up of the peasants and their executions in various venues. One group is taken to a chapel in a graveyard to be killed, another is killed by the church, and so on, but it is difficult to tell one group from another or to get a sense of how many peasants were slaughtered. (The original total was somewhere around 750 to 800.)

Overall the cinematography conveys the setting well, both the hilly, wooded landscapes and the ancient stone farmhouses. There’s a very effective scene where the townspeople take refuge in a church and Martina’s older sister runs back and forth from the bell-tower, reporting the fighting below, which we see only from far away, as she does. In fact, this sister is a more engaging character than Martina, and would have made a better point-of-view figure. Another gripping scene comes when she, seriously wounded in the massacre, is suddenly pulled out of the pile of bodies and given first aid by a Nazi officer. She’s mystified as to why he’s doing this, though we hear him tell another soldier that she reminds him of his wife. It may seem as if the insanity of war would be more effectively conveyed through a thoroughly naive character’s eyes, but at least in this case, somehow that doesn’t work.

Of Love and Other Demons.

The ROW strikes again

The Time that Remains.

Kristin here:

Last year I remarked on how festivals like Vancouver are increasingly showing films from countries that have barely contributed to world cinema until recently. Not surprisingly, the trend continues. Yesterday I saw The Search (dir. Pema Tseden), the second feature to by made in Tibet by a team of Tibetans. (The first was also by Tseden.) It’s strongly reminiscent of Kiarostami’s best-known films, with a small film team traveling through the countryside trying to cast a movie based on a classic indigenous opera.

So far, however, most of the films I’ve seen have been from more established filmmaking regions.

Latin America

Latin American cinema continues to grow beyond Mexico, Brazil, and Peru, largely thanks to European co-productions and occasionally co-productions between countries within the region. For me, the first day of the festival concentrated on Latin America.

The first stop was Peru, with the surprise winner of this year’s Golden Bear at Berlin, Claudia Llosa’s The Milk of Sorrow. The plot concerns Fausta, a young woman whose mother, pregnant with her, was raped and tortured during era of the government’s war against the Shining Path insurgents (1980s-1990s).

Haunted by a fear of being raped herself, Fausta imitates a trick that a woman supposedly employed to fend off attackers. She places a potato in her vagina, hoping that the protruding shoots will repel a would-be rapist. Her terror of leaving home alone limits her freedom, though she manages to take a job as a maid to an eccentric female pianist. Her plight is ironically emphasized by the fact that her uncle is a wedding coordinator, and there are several scenes involving outgoing young women who are attuned to modern life and eager to marry.

The Milk of Sorrow is beautifully shot, with a minimal plot that proceeds at a languorous pace. It fits very much into the art cinema destined primarily for festival and big-city screenings.

Two other two films of the day were distinctly more reminiscent of Hollywood in their pacing and strong plots. Sebastián Silva’s The Maid has a familiar plot, the repressed character who needs to learn to enjoy life and other people. Raquel has served the same family for decades and become obsessed about her own little domain of power, pampering one child she adores, annoying another, and running the household to suit herself. Eventually, when an outgoing second maid is hired, Raquel is surprised to find herself with a friend and begins to come out of her shell.

Two other two films of the day were distinctly more reminiscent of Hollywood in their pacing and strong plots. Sebastián Silva’s The Maid has a familiar plot, the repressed character who needs to learn to enjoy life and other people. Raquel has served the same family for decades and become obsessed about her own little domain of power, pampering one child she adores, annoying another, and running the household to suit herself. Eventually, when an outgoing second maid is hired, Raquel is surprised to find herself with a friend and begins to come out of her shell.

Stylistically there’s nothing of great interest. As with so many films these days, it was shot in real locales, mostly the interior of one large house, and so consists mostly of medium shots and lots of panning. It’s essentially an actor’s film, though, and I could easily imagine it being remade in English as a vehicle for someone like Meryl Streep. It effortlessly balances drama and humor and is continually entertaining. It also features the only unequivocally upbeat ending among the films I’m discussing here, which no doubt says something either about the state of the world or about what filmmakers assume festival programmers look for.

Equally skillful but miles away in tone is the Mexican feature Backyard, by Carlos Carrera. Focusing on the astonishingly frequent rape, torture, and murder of women in Juàrez, the film follows a lone female detective in a police force which refuses to arrest or prosecute any of the perpetrators. (Above, she is confronted with hundreds of photos of the dead and missing.) The reasons behind both the numerous murders and official indifference turns out to be a combination of circumstances: at least one serial killer with the means to pay off the police, the executive of a Japanese factory that doesn’t want bad publicity, and random abusive husbands and young punks who take advantage of the situation to dump their victims in the desert with impunity.

The story is handled in taut classical fashion, intercutting between the detective’s investigations and the story of one young factory girl factory who eventually becomes a victim. This is the stuff of CSI and other crime shows, but all based on a horrific real-life situation that goes beyond what any mainstream drama would dare to show and that continues to this day right, as the title emphasizes, in America’s backyard.

One of the best films we’ve seen so far is Lucrecia Martel’s third feature, The Headless Woman. Although I had admired her visually gorgeous La ciénaga (2001), I found it a bit obvious in its use of the central swamp metaphor to characterize the upper-middle class. The Headless Woman, though, is the epitome of subtlety, with the plot being a puzzle with easily missed clues doled out sparingly. (The Variety review considerably mis-describes what happens, and I suspect others do as well.)

The opening is simple enough, with some boys playing in a dry concrete canal. Nearby, Veró, the woman of the title, helps her sister Josefina shoo a group of noisy kids into one car, while Veró takes off alone in the other. In a remarkable long take, she drives until the car lurches, causing her to bump her head on the windshield. Rather than cutting to what Veró hit, the camera stays with her as she sits, dazed. After a long pause she drives on, and a new framing allows us to briefly glimpse a large dead dog on the road in the distance. Soon the heroine stops and gets out of the car, walking out of focus as we stay in the car and the first heavy drops of a storm strike the windshield (below). One hint: even the exact moment when the rain starts becomes a clue to unraveling the action to come.

The rest of the film stays with Veró, who is present onscreen or off in every scene. We watch her uncertainty, caused by a concussion, but those around her barely notice, attributing her memory loss to tiredness or illness. Eventually Veró tells her husband that she thinks she has killed someone on the road. It would be unfair to reveal more, since experiencing the twists and implications of the plot should be up to the viewer.

Stylistically the film develops on Martel’s characteristic technique of shooting largely in tight shots filmed with highly selective focus. Often one must search for the one significant character. At other times, the camera lingers on Veró’s face, glancing vaguely around with a slight, defensive smile, pretending that nothing is wrong, as more significant actions by the other characters occur out of focus in the background. Often children swarm around, placing the thin thread of the central drama in the context of insignificant gestures of everyday life but making the clues all the harder to notice.

So well hidden is the plot that many viewers will mistakenly decide that it’s a film where nothing much happens. Those who engage with it will discover quite the opposite. But be warned, only a very alert viewer could figure out the plot correctly on a single viewing. I’ll admit I missed a crucial remark on the first pass.

(See also Jim Emerson’s take on The Headless Woman.)

The Middle East

Ahmad Abdalla behind the camera shooting Heliopolis.

David and I both saw Heliopolis, he because it’s a network narrative and I because it’s an interesting district of Cairo that I know only slightly. Egypt may in the past have been the main supplier of mainstream entertainment movies for the Middle East, but Heliopolis is very much an indie, made by first-time director Ahmad Abdalla with a tiny crew shooting on location for a mere two weeks.

In a rare move for this kind of narrative, the characters from the various plotlines barely intersect. Instead, Heliopolis itself is the focus. It’s a suburb near the airport that tourists drive through on their way to the central city but seldom visit. Once an enclave of foreigners, it is now is one of the main districts for middle- and upper-middle-class Egyptians. The beauty of the old buildings, some now shells and threatened with demolition, contrasts with an increasingly westernized youth culture on the streets. Similarly the characters, all with their own aspirations, suffer disappointments in the end, creating a bittersweet tone that becomes generalized to the district.

Lebanon, the Israeli film that won the top prize at the Venice Film Festival, tells a compressed story set during the first day of the Israeli-Lebanon war. It centers on a four-man team in a tank, all going into real combat for the first time. Director Samuel Maoz confines his camera to the interior of the tank for nearly all of the action, limiting our knowledge to the characters’ viewpoints (above). What we see of the war appears through the crosshairs of the mens’ scopes, though the director does not cue us to identify consistently with any of the individual team members.

The increasingly fetid interior of the tank becomes tangibly apparent as the men’s stubbly faces gleam with sweat and grime. At intervals Maoz cuts to grotesquely lyrical details of the tank’s surfaces, with oil oozing into dials or down the walls and filthy liquid on the floor rippling with the machine’s vibrations.

Many of the conventions of the men-at-war film are present, including the young man being killed just as his message assuring his parents of his safety is delivered and the novice gunner who fails to fire when he should but then kills an innocent passerby. But such conventions are renewed through the claustrophobia of the setting and the refusal to hold back in showing the confusion, terror, and savagery of war. Only the opening and closing shots, whether consciously or not an echo of Dovzhenko, offer a hint of peace.

As an admirer of Elia Suleiman’s Divine Intervention, I anticipated most seeing his new film, The Time that Remains: Chronicle of a Present Absentee. It did not disappoint, though it is less ingratiating than the earlier film. Where Divine Intervention is largely based on subtle, ironic comedy played out primarily in Tati-esque long shots, The Time that Remains mixes long stretches of pure drama with the irony. I’ve read tepid reviews that reflect a lack of patience in figuring out what Suleiman was up to this time.

There are no Arrafat-face balloons flying over Jerusalem or fantasy ninja-revenge scenes here. Instead, apparently working with a larger budget, Suleiman ambitiously sets parts of his film in 1948 and other key years of the struggle between Palestinians and Israelis. His father appears as a constant participant in that struggle (seen in dark trousers in the frame at the top). The child Elia shows up partway through and becomes a silent witness to much of this. (As in Divine Intervention, the director plays himself but never speaks.) He acts more as a sympathizer than as an active participant in the conflict, going into exile as a young man and, as we know returning at intervals to make films that comment on the political situation. Hence the “present absentee” of the title.

The older scenes include staged skirmishes and chases, with genuine suspense, before the film settles into the modern era and the humorous, sometimes blackly humorous, life of Suleiman’s aging family and neighbors. As the earlier film dealt with his father’s final illness, the new one lingers over his mother’s.

Despite the drama, there are some characteristically hilarious moments. An unarmed Palestinian man takes out his garbage and paces during a cellphone conversation, ignoring all the while an enormous tank whose gun-turret swivels to cover his every move from a few feet away. Young Palestinians dance to loud music, seen through the glass walls of a discotheque. An Israeli jeep stops outside, vainly trying to make a curfew warning heard over the din, and the soldiers inside unwittingly start bobbing their heads slightly in time to the music.

We’re off to another day of film-viewing and will post again soon.

The Headless Woman.

Showing what can’t be filmed

DB, again:

People tend to think that documentary films are typified by two conditions. First, the events we see are unstaged, or at least unstaged by the filmmaker. If you mount a parade, the way that Coppola staged the Corpus Christi procession in The Godfather Part II, then you aren’t making a documentary. But if you go to a town that is holding such a procession and shoot it, you are making a doc—even though the parade was organized to some extent by others. Fiction films stage their events for the camera, but documentaries, we tend to think, capture spontaneous happenings.

Secondly, in a documentary the camera is seizing those events photographically. The great film theorist André Bazin saw cinema’s defining characteristic as its capacity to record the actual unfolding of events with little human intervention. All the other arts rely on human creation at a basic level: the novelist selects words, the painter chooses colors. But the photographer or filmmaker employs a machine that impassively records what is happening in front of it. “All the arts are based on the presence of man,” Bazin writes; “only photography derives an advantage from his absence.” This isn’t to say that cinema can’t be artful, only that it offers a different sort of creativity than we find in the traditional arts. The filmmaker works not with pure imaginings but obstinate chunks of actual time and space.

Given these two intuitions, unstaged events and direct recording of them, it would seem impossible to consider an animated film as a documentary. Animated films consist of almost completely staged tableaus—drawings, miniatures, clay, even food or wood shavings (in the works of Jan Svankmajer). And animated movies offer no recording in Bazin’s sense of capturing the flow of real time and space. These films are made a frame at a time, and the movement we see onscreen doesn’t derive from movement that occurred in reality. And of course you can make an animated film without a camera, for instance by painting directly on film or assembling computer-generated imagery.

Recently, however, we’ve been faced with animated films that claim documentary validity. How is this possible? Maybe we need to rethink our assumptions about what documentary is.

In certain types of documentaries, especially those in the Direct Cinema or cinéma vérité traditions, the assumption that we’re seeing spontaneously occurring events holds good. But a documentary can consist wholly of staged footage. Think back to those grade-school educational shorts showing a tour of a nuclear power plant. Every awkward passage of dialogue recited by the hard-hatted, white-coated supervisor was scripted. The whole show was planned and rehearsed, but that doesn’t detract from the factual content of the film.

Go further. Recall those attack maps that are shown in war films, tracing the progress of an army through enemy terrain. Now imagine an entire film made of those animated maps. The maps might even be enhanced with a few cartoon images, as in the above shot from one of the Why We Fight films. The film would be entirely designed, presenting no spontaneous reality being captured by the camera. Yet it would plainly be a documentary, telling us that, say, the Germans marched into the Sudetenland in 1938 and proceeded on to Poland. So we don’t need photographic recording of actual events to count a film as a documentary either. Both the staging and the recording conditions don’t have to be present for a film to count as a documentary.

I’m not saying that the claims advanced in my nuclear-power film or my attack-map movie would necessarily be accurate. They might be erroneous or inconclusive or false. But that possibility looms for any documentary. The point is that the films, presented and labeled as documentaries, are thereby asserting that the claims and conclusions are true.

Film theorist Noël Carroll defines documentary as the film of “purported fact.” Carl Plantinga makes a similar point in saying that documentaries take “an assertive stance.” Both these writers argue that we take it for granted that a documentary is claiming something to be true about the world. The persons and actions are to be taken as representing states of affairs that exist, or once existed. This is not something that is presumed by The Gold Rush, Magnificent Obsession, or Speed Racer. These films come to us labeled as fictional, and they do not assert that their events and agents ever existed.

This isn’t just a case of a professor stating something obvious in a fancy way. Once we see documentary films as tacitly asserting a state of affairs to be factual, we can see that no particular sort of images guarantees a film to be a doc.

Take the remarkable documentaries made by Adam Curtis. These are in a way very old-fashioned. Blessed with a voice whose authoritative urgency makes you think that at last the veils are being ripped away, Curtis mounts detailed arguments framed as historical narratives. Freudian theory shaped the emergence of public relations, which was in turn exploited not just by business but by government (Century of the Self). Islamic fundamentalism grew up intertwined with US Neoconservatism, both being reactions to perceptions that the West was becoming heartlessly materialistic (The Power of Nightmares). Mathematical game theory came to form politicians’ dominant conception of human behavior and civic community (The Trap). The almost uninterrupted flow of Curtis’s voice-over commentary could be transcribed and published as a piece of nonfiction. True, there are some interpolated talking heads, but those experts’ statements could be printed as inset quotations.

What’s particularly interesting is that Curtis’ rapid-fire declamation accompanies images that often seem not to illustrate it, or at least not very firmly. Like the found footage in the preacher’s sermon “Puzzling Evidence” in True Stories, Curtis’ images are enigmatic, tangential, or metaphorical.

Here are a few seconds from the start of The Power of Nightmares. Eyes are staring upward, as if possessed.

We hear: [Our politicians] say that they will rescue us from dreadful . . .

The eyes are replaced by a shot of a man wearing a cowl, and as this image zooms back the commentary continues.

. . . dangers that we cannot see and do not . . .

Cut to a magician or mime demanding silence.

. . . understand.

Cut to rockets being fired.

And the greatest danger . . .

Cut to a procession of cars, seen from above, rounding a corner into a government compound at night.

. . . of all is international terrorism.

Cut to shot of security agent staring at us.

The ominous, not to say paranoid, tenor of the sequence is aided by the unexpected juxtapositions. For instance, you’d think that the shot of the iconic terrorist (anonymous, with automatic weapon) would be synchronized with the final line of the commentary, referring to “international terrorism.” Instead the commentary links the mention of terrorism to an image of government deliberation, and then to an image of surveillance (aimed at us, but also perhaps suggesting the previous high-angle shot was the spy’s POV). The wild-eyed close-up might belong to a terrorist, but is accompanied by claims about rescuing us from fearsome threats, so the eyes could also belong to someone panicked–especially since they contrast immediately with the sober eyes of the gunman in the cowl. Perhaps the first shot represents the fearful public ready to be led by the politicians playing on fear. And the insert shot of the mime becomes sinister but also comic, perhaps debunking the official position that our dangers are unseen and unknowable. In all, the sequence bubbles with associations that are less fixed and more ambiguous than we’re likely to find in a more orthodox documentary, like Jarecki’s Why We Fight.

My point isn’t to analyze the image/ sound relations in Curtis’s work, a task that probably demands a whole book. (This sequence takes a mere eleven seconds.) I simply want to propose that regardless of what pictures Curtis shows, his films are documentaries in virtue of a soundtrack constructed as a discursive argument that makes truth claims. The picture track often works on us less as supporting evidence than as a stream of associations, the way metaphors or analogies give thrust to a persuasive speech.

Just as we could have an account of Germany’s 1938 invasion of Czechoslovakia presented in cartoon form, we could imagine The Power of Nightmares illustrated with political cartoons. Once we’ve pried the image track loose from the assertions on the soundtrack, anything goes.

One example much on our minds now is Waltz with Bashir. Ari Folman interviews former Israeli soldiers. But instead of using film footage of their conversations and, say, still photos of the events in Lebanon they took part in, he provides (until the final sequence) drawings a bit in the Eurocomics mold of Tardi or Marc-Antoine Mathieu. The result takes the form of a memoir, admittedly. But in both literature and cinema, memoir is a nonfiction genre.

Another memoir supports the point. Marjane Satrapi’s autobiographical graphic novels, Persepolis and Persepolis 2, assert factual claims about her life. The claims are presented as drawings and texts rather than simply as texts, but that doesn’t change the fact that she presents agents and actions purported to have existed. True, on film the people whom she remembers are represented through voice actors speaking lines she wrote. But as with written memoirs (especially those that claim to remember conversations taking place fifty years ago), we can always be skeptical about whether the events presented actually took place.

Another memoir supports the point. Marjane Satrapi’s autobiographical graphic novels, Persepolis and Persepolis 2, assert factual claims about her life. The claims are presented as drawings and texts rather than simply as texts, but that doesn’t change the fact that she presents agents and actions purported to have existed. True, on film the people whom she remembers are represented through voice actors speaking lines she wrote. But as with written memoirs (especially those that claim to remember conversations taking place fifty years ago), we can always be skeptical about whether the events presented actually took place.

Turning Satrapi’s published memoir into an animated film did not change its status as a documentary. If we had contrary evidence, we could charge her with fibbing about her family life, her rebelliousness, or her life in Europe. But we’d be questioning the presumptive assertions the film makes, not the fact that it is drawn and dubbed rather than photographed from life.

We’re tempted to see the animation in these films as adding a level of distance from reality. We’re so used to fly-on-the-wall documentaries that we may be suspicious of the cobra-like caricatures of the female teachers in Persepolis or the hallucinatory dawn bombardment in Bashir. Yet animation can show things, like the Israeli veterans’ dreams, that lie outside the reach of photography. And the artificiality doesn’t dilute the claims about what the witnesses say happened any more than does purple prose in an autobiography. In fact, the stylization that animation bestows can intensify our perception of the events, as metaphors and vivid imagery in a written memoir do.

I realize I’m pointing toward a slippery slope here. Strip off the image track from Aardman‘s Creature Comforts and you have impromptu recordings of ordinary people talking about their lives. Those monologues could have been accompanied by documentary-style talking heads. Does that make Creature Comforts a documentary? I’d say not because the film doesn’t come to us labeled that way; it’s presented as comic animation using found soundtracks (like the movie based on the Lenny Bruce routine Thank You Mask Man). Then there are Bob Sabiston‘s rotoscoped films like Waking Life and The Even More Fun Trip, recently released on Wholphin no. 7. The latter (left) takes another documentary form, the home movie, as the basis for its animation. This seems to me an instance where the documentary category has the edge, but it’s a surely a borderline case.

I realize I’m pointing toward a slippery slope here. Strip off the image track from Aardman‘s Creature Comforts and you have impromptu recordings of ordinary people talking about their lives. Those monologues could have been accompanied by documentary-style talking heads. Does that make Creature Comforts a documentary? I’d say not because the film doesn’t come to us labeled that way; it’s presented as comic animation using found soundtracks (like the movie based on the Lenny Bruce routine Thank You Mask Man). Then there are Bob Sabiston‘s rotoscoped films like Waking Life and The Even More Fun Trip, recently released on Wholphin no. 7. The latter (left) takes another documentary form, the home movie, as the basis for its animation. This seems to me an instance where the documentary category has the edge, but it’s a surely a borderline case.

Animated documentaries are likely to remain pretty far from our prototype of the mode. Still, we should be grateful that even imagery that seems to be wholly fictional—animated creatures—can present things that really happen in our world. This mode of filmmaking can bear vibrant witness to things that cameras might not, or could not, or perhaps should not, record on the spot.

André Bazin’s arguments for the documentary basis of cinema are set out in “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” in What Is Cinema? ed. and trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), 9-16. Noël Carroll’s argument that documentaries are framed as presenting “purported fact” can be found in Theorizing the Moving Image (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 224-259. On the “assertive stance” of documentaries, see Carl Plantinga, Rhetoric and Representation in Nonfiction Film (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 15-25. Errol Morris interviews Adam Curtis here. Thanks to Mike King for pointing me toward The Even More Fun Trip.

PS 10 March: Harvey Deneroff writes:

Very much enjoyed your post on animated documentaries, a topic of some interest to and often discussed in the animation studies community. There was a panel on it during last year’s Society for Animation Studies conference and there will also be one at this year’s as well.

Two recent Oscar recipients for Best Animated Short Subject are also documentaries: Chris Landreth’s wonderful computer animated Ryan (produced by the NFB about animator Ryan Larkin, and features a lot of talking heads) and John Canemaker’s The Moon and the Son: An Imagined Conversation, which is about Canemaker’s father and mixes animation with home movies and photographs.

At least two winners in the Oscar Documentary Short Subject category were largely animated: Chuck Jones’ So Much for So Little (WB, 1949, which I believe was made for the US Public Health Service) and Norman McLaren’s Neighbours. The Story of Time, a 1951 British documentary which featured stop motion animation was nominated in the same category.

Also, the International Leipzig Festival for Documentary and Animated Film includes a section for animated documentary films.

Thanks to Harvey for this. I’m not sure I’d categorize Neighbours as a doc, but it’s a long time since I’ve seen it. On Harvey’s site he also has a note quoting Ari Folman on the difficulty of funding animated docs. And thanks to Ryan Kelly and Pete Porter for reminding me of Winsor McCay’s Sinking of the Lusitania from 1918.