Archive for the 'Documentary film' Category

Wisconsin Film Festival 2021: Streaming goodness

Trailer by Christina King.

DB here:

We’re been tardy about posting lately. Reasons, not excuses: I finished a book manuscript of ungainly length. Kristin has been preparing and giving a talk for an Egyptological conference. Some medical matters (non-fatal, boring) have preoccupied me further.

But who could resist telling you about the offerings of our revived Wisconsin Film Festival? Felled last spring by COVID, it has bounced back as lively as ever. Over 110 films are streaming over eight days, 13-20 May.

Some films are available to anybody anywhere, others only to people in Wisconsin or the Midwest or the USA. Some screenings may be “at capacity” because of audience limits set by distributors (who reasonably don’t want to cannibalize screenings at other fests). You can check your access to a film by visiting that film’s Eventive page on the fest site, and you can learn how to access the fest shows on the Eventive information page.

In particular, many of the regional productions we proudly host might be things you can’t be sure of catching anywhere else.

The other S-word

“Socialism” is back in the news. 120 mostly obscure brass hats have just proclaimed that the 2020 election was stolen. (Maybe this level of cluelessness explains our post-1945 record of winning wars.) The signatories add that the immediate conflict is “between supporters of Socialism and Marxism vs. supporters of Constitutional freedom and liberty.” These writers who obviously have not seen Dr. Strangelove or Seven Days in May. Otherwise, they’d try out better lines.

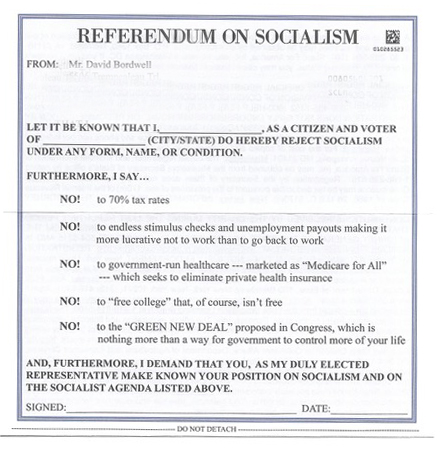

Earlier this week I received an invitation from former UN Ambassador Nikki Haley to sign up for the “National Referendum on Socialism.” The envelope window displayed a teasing flash of legal tender. It turned out to be a crisp 100-Bolivar note from Venezuela, worth about $.10.

This crushing proof that socialism doesn’t work was accompanied by Nikki’s memoir about seeing, first hand, the failures of regimes like Venezuela, Cuba, and Communist China, all representing “the terminal stage of socialism.” She reports that some of them lack toilet paper. This outrage must not stand.

For me to receive this, the Republican Big Data dragnet proves as undiscriminating as a notification I’ve inherited a fortune in Bitcoin. Still, I was happy to reply. I voted yes, or as Nikki would have it YES!, to all the options. These included 70% tax rates for her and her friends and a rejection acceptance of Nordic social democracy, an option her world travels seemed to have missed. And I’m keeping the Bolivars.

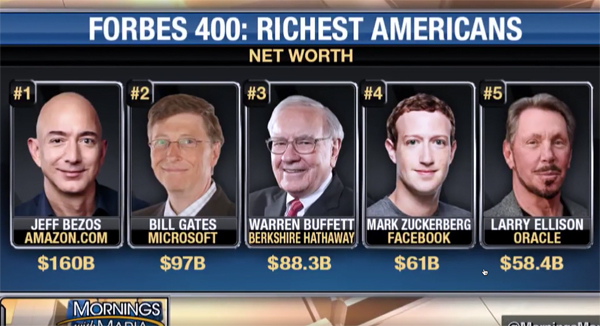

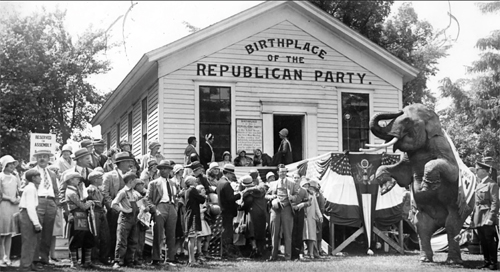

So the right-wing lies make it all the more timely that WFF has included a double feature that might well speak to the rising interest in socialism among the young and the equality-curious. The main film is Yael Bridge’s The Big Scary “S” Word. It interweaves an historical narrative with two ongoing dramas of today. From the survey we learn, as Cornel West explains, that socialism is “as American as apple pie.” John Nichols, author of The S-Word, is on hand to trace the movement back to the nineteenth century and remind us that “The Republican Party was founded by socialists.”

Other commentators show how the rise of capitalism and the cascade of crises it brought forth tended reliably to arouse demands for equal rights and economic justice. We learn of Lincoln’s friendly correspondence with Marx, of slavery’s centrality to American capital accumulation, and of the post-World-War II reaction against the New Deal, building through Reagan to Bush and Clinton. The 2008 financial crisis supplied fresh momentum for a critical reaction to capitalism; Wall Street’s capture of the economy encouraged some people to take a new look at socialist policies.

There are as well doses of theory, as when political scientists point out that capitalism depends crucially on expanding the concept of private property and inclines toward treating unpropertied individuals as interchangeable, expendable units. This may explain why conservatives explode over graffiti but praise a teenager shooting down peaceful demonstrators.

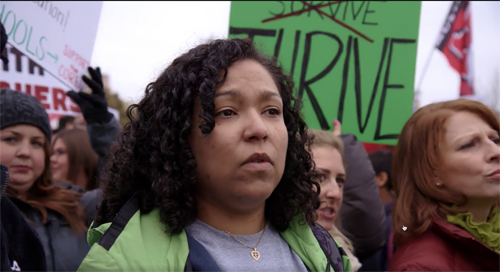

Threaded through Bridge’s account are affirmative moments: the creation of worker-owned coops, the establishment of the Bank of North Dakota (owned by taxpayers), and the stories of two young people who were fed up with injustice. One is Stephanie Price, an elementary-school teacher working two jobs; some of her income goes to books and supplies for her students. (This scenario is familiar.) She joins a teachers’ strike and finds that the union isn’t effective in fighting their Oklahoma legislature. Chris Carter, an ex-marine, is the only socialist on the Democratic side of the Virginia legislature. He learns that even Democrats are capable of sabotage (surprised?), running an oppo ad linking him with a hammer and sickle. The stories of Stephanie and Chris provide suspense and yield a flare of hope.

How to Form a Union, directed by Gretta Wing Miller, is a story that could only come from the People’s Republic of Madison. During the 197os, the Willy Street Coop was an emblem of our town’s progressive tradition. But as it expanded, it faced competition from Whole Foods and other hip purveyors of provender. (I remember visiting Whole Foods and feeling old when Björk came on the Muzak.) Workers at the Coop accused it of corporatization and agitated for higher wages, less draconian shift policies, and ultimately a union. What happened next is told with quiet passion and a fine array of talking heads.

The proclamations of our statewide election officials, cartoonish reactionaries like Ron Johnson, Glenn Grothman, and their lot, have over the last few years made me think that such large, loud, stupid people typify Wisconsin. Seeing these two films, steeped in state history, reminded me of things we can be proud of. Yes, Wisconsin gave America Joe McCarthy and Scott Walker and Reince (Obvious Anagram) Priebus and Scott Fitzgerald, who greeted voters in a hazmat suit while assuring them that Covid was no danger. But we also gave America socialist mayors, Bob LaFollette (a Republican), and political fighters like Tony Evers, Mandela Barnes, Mark Pocan, and Tammy Baldwin. These are people on the right–that is, left–side of history.

Roman New Year

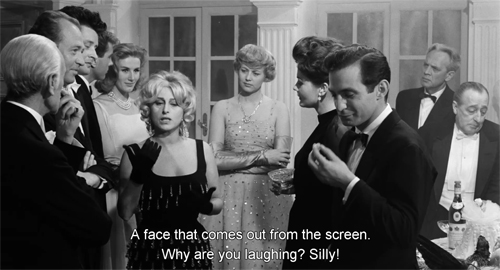

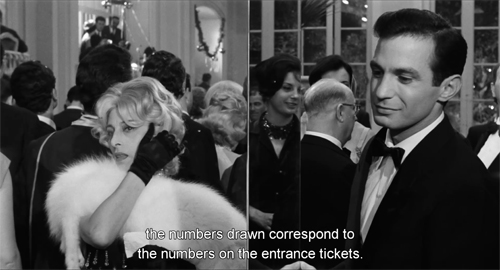

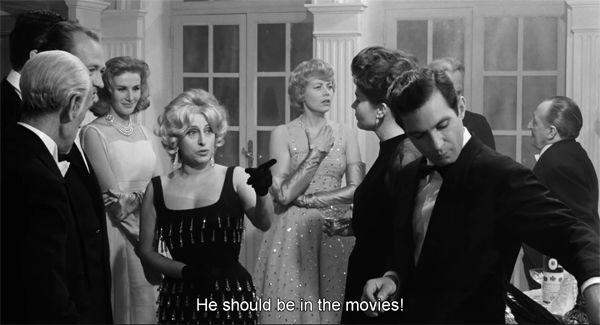

The Passionate Thief (1960).

One of the long-running revelations of the Bologna festival Cinema Ritrovato is the rich tradition of Italian comedy. (See here, and here.) One admirer is our programmer Jim Healy, who this year brought us a delightful example, Mario Monicelli’s The Passionate Thief (another film from the fabulous year 1960). Two top Italian stars, the vivacious Anna Magnani and the glum Totò, work on the fringes of the film industry. This justifies behind-the-scenes glimpses of Cinecittà, as well as the usual satire on the follies of filmmaking. We’re introduced to Magnani as part of a crowd in a sword-and-sandal epic, while Totò scrapes up work as an extra.

But it’s New Year’s Eve, and Magnani seeks out friends for a party. Meanwhile Totò is recruited as a partner for pickpocket Ben Gazzara, in the sort of imported-star turn that was common in European coproductions. His brooding, cynical presence adds a touch of gravity to a crowded night of crisscrossing destinies featuring a drunk American millionaire (Fred Clark), frenzied Roman partygoers, and rich Germans whose mansion is invaded by our trio. Gusto, brio, sprezzatura, zest–choose the word, this movie has plenty.

It also has stunning black-and-white cinematography, and its use of the 1:1.85 ratio should be studied by every film student. The screen area is shrewdly filled in long-take mid-shots.

And since we know Ben is a thief, his wandering left hand draws us away from La Magnani’s monologue, while Totò frets in the background.

Yes, mirrors are involved throughout, sometimes creating weird split-screen effects.

Much of the movie was shot on location and it reminds us that the splendor of La Dolce Vita (released the same year) wasn’t a one-off.

This ripe imagery doesn’t slow down the bustle of the whole thing. The plot seems more episodic than it is; the opening sets up a minor character (a tram driver) and a food motif (lentils) that will pay off later. Clever as the devil, The Passionate Thief is one of those pieces of good dirty fun that keeps you, and us, going back to film festivals.

The Festival’s Film Guide page links you to free trailers, podcasts, and Q &A sessions for each film.

Thanks as ever to the untiring efforts of the festival panjandrums (I always wanted to use that word) Kelley Conway, Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Pauline Lampert, and all their many colleagues, plus the University and the donors and sponsors that make this event possible.

The Passionate Thief (1960).

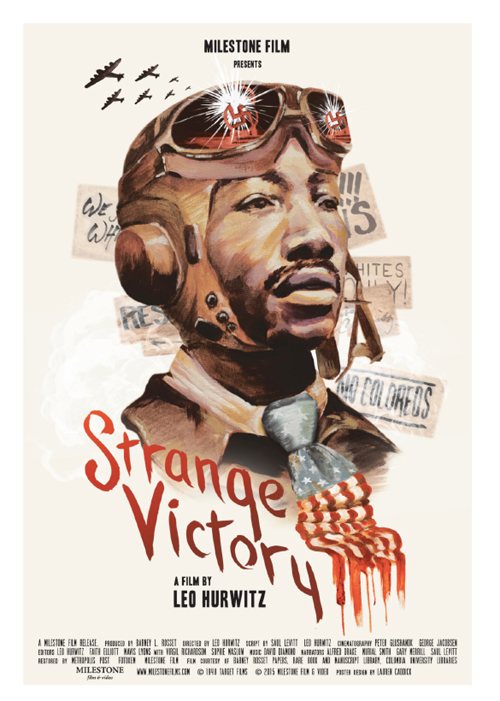

Repost: Our daily barbarisms: Leo Hurwitz’s STRANGE VICTORY (1948)

We have never reposted an entry before, but given recent events in US history, and the celebration of Martin Luther King’s legacy yesterday, and the impending inauguration of a new president tomorrow, we are re-running this entry, unrevised, from nearly four years ago.

It’s not just that it remains timely. (The interpolations remind us that Trump has been inciting violence from the start.) We wanted also to note that thanks to Milestone Films you can stream Strange Victory here. I plan to write more about the end of the Trump era in the days to come, but for now we can acknowledge the struggles ahead of us. We can be strengthened by recognizing that in 1948 people who had sacrificed far more than we have still sustained an urge to fight for decency and justice. –DB

DB here:

Leo Hurwitz is perhaps best known for Native Land (1942), the documentary codirected with Paul Strand and narrated by Paul Robeson. Strange Victory (1948) has been less easy to see. It was scarcely distributed and, though some reviews praised it, it was accused of Communistic sympathies. Now, restored and recirculated by the enterprising Milestone Films, Strange Victory has lost none of its compassion and righteous anger. Thanks to the energy of the Milestone team, led by A my Heller and Dennis Doros, every citizen has a chance, say rather a duty, to see a film whose force is undiminished today.

my Heller and Dennis Doros, every citizen has a chance, say rather a duty, to see a film whose force is undiminished today.

In a period of postwar optimism, Hurwitz and his colleagues dared to point out that the prejudices exploited by the Nazis remained powerfully present in the United States. The winners, it seemed, hadn’t repudiated the bigotry of the losers. American racism persisted and even intensified. The Nazis lost, but a form of Nazism won.

Dec. 14, 2015, in Las Vegas. Individuals at a Trump rally yelled “Sieg Heil” and “Light the motherfucker on fire” toward a black protester who was being physically removed by security staffers.

News of the world

Like The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936), on which Hurwitz was cameraman, and the Why We Fight series, Strange Victory is largely a compilation documentary. Guided by voice-over narration, it ranges across newsreels of Hitler’s rise, chilling combat shots, and footage from the liberated death camps.

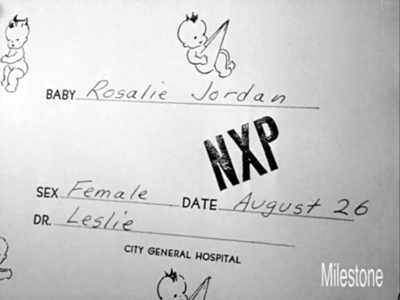

But Hurwitz and his team shot a lot of new material as well, with an eye to bringing out the postwar significance of their theme. Newborn babies eye the camera, and kids play on sidewalks and in backlots (some shots recall Helen Levitt’s evocative street photos). Meanwhile, anxious adults approach a newsstand. “If we won, why are we unhappy?” the narrator asks at the beginning. The question is answered at the end: “There was not enough victory to go around.”

Thanks to a hidden camera, that newsstand becomes a sort of gathering spot, a place where people might encounter uncomfortable truths. Intercut with people buying newspapers are images of battles, as if the hunger for news aroused by the war didn’t dissipate. But what is that news? Hurwitz introduces it quickly: the rise of nativist bigotry. In an eye-blink, racist decals are slapped on fences, synagogues are smashed, and vicious pamphlets swarm through the frame. Race-baiting politicians, radio hate-mongers, and fascist sympathizers–the 1940s equivalents of our celebrity demagogues–are pictured and named. This is just one of many passages that guaranteed that Strange Victory could never be circulated on mainstream theatre circuits.

Hurwitz mixes found footage, stills, posed images, and fully staged scenes, such as the episode in which a Tuskegee Airman tries to find a job with an airline. In this mixed strategy he follows not only the precedent of the March of Time series but also, and more self-consciously, the Soviet documentarist Dziga Vertov.

In a 1934 article, Hurwitz called The Man with a Movie Camera “the textbook of technical possibilities,” and he isn’t shy about mimicking the master. Early in the film, portraying the Allies’ victory, a shot shows a swastika-emblazoned building blown to bits in slow motion. Later, to convey the return of Hitlerism, the same shot is run backward, reinstating the swastika on the building’s roof. A graphically matched dissolve equates a Klan wizard with Southern senator John Elliott Rankin.

Later, via constructive editing à la Kuleshov, parental pride is made color-blind, as both a white mother and a black one return a father’s glance.

The film hasn’t aged a bit. The print is gorgeously subtle black and white, and the score by the underrated David Diamond is warm in a chamber-music way. The film’s vigorous voice-over and its ricocheting images (some returning as refrains, bearing new implications) look forward to the hallucinatory, expanding associations created by our most biting contemporary documentarist, Adam Curtis.

Shiya Nwanguma, a young African-American student at the University of Louisville, was shoved and verbally abused when she attempted to protest at the Trump event. “I was called a nigger and a cunt, and got kicked out,” Nwanguma said after the incident. “They were pushing and shoving at me, cursing at me, yelling at me, called me every name in the book. They’re disgusting and dangerous.”

Shiya Nwanguma, a young African-American student at the University of Louisville, was shoved and verbally abused when she attempted to protest at the Trump event. “I was called a nigger and a cunt, and got kicked out,” Nwanguma said after the incident. “They were pushing and shoving at me, cursing at me, yelling at me, called me every name in the book. They’re disgusting and dangerous.”

One of the individuals involved in the confrontation with Nwanguma was Joseph Pryor, a native of Corydon, Indiana, who graduated from high school last year. After the rally, Corydon posted a photo on his Facebook page that showed him shouting at Nwanguma. The post went viral and eventually attracted the attention of the Marine Corps, which Pryor had just joined.

The Marine Corps recruiting station in Louisville told military publication Stars and Stripes that Pryor had recently enlisted and was about to head off for boot camp. Captain Oliver David, a spokesman for the Marine Corps command, said Pryor had not yet undergone Marine Corps ethics training. . . . He added: “Hatred toward any group of individuals is not tolerated in the Marine Corps and he is being discharged from our delayed entry program effective [Wednesday].”

The tyranny of facts

As ever, the ordering of parts matters greatly. How best to convey the idea that after a struggle to cleanse Europe of violent prejudice, the same attitude is flourishing in America? You might think of couching your argument as a narrative. In chronological order, that would be: The rise of Hitler; the war defeating Hitler; the celebration of victory; the return of American bigotry in the postwar period. Clear and straightforward.

Hurwitz is more canny. Many films embracing rhetorical form, like the problem/solution structure of Pare Lorentz’s The River (1938), will embed brief narratives into their overarching argument. This is Hurwitz’s approach, but his stories aren’t chronologically sequenced. Instead, we start with the America of today before flashing back to the high price of defeating the Axis. “Everybody paid,” says the male narrator. “Everybody.” With a pause to register Roosevelt’s death, jubilation surges up as the Nazis fall. “For a day or two, the plain people owned the world.” But then we’re back to the newsstand and a montage of race-baiters and graffiti scrawlers.

Then, as we see a pregnant woman on a bench, we hear a woman’s voice. Her poetic musings reassure the newborn babies that they have a place here; she welcomes them to earthly love. Following the montage of haters with images of innocence casts a melancholy pall over these fresh-begun lives. They know nothing of the American brownshirts, but we know that they must learn our world.

This foreboding is confirmed by a chorus of name-calling over shots of newborns, the woman’s song of innocence is undercut by a song of bitter experience. A new male narrator (Gary Merrill) raps out the facts of “our daily barbarisms.” Get ready, he warns the babies: You will be tagged and vilified by how you look and where you live. “Separation of people is a living fact,” and they are future “casualties of war.” Throughout the rest of the film, the shots of children carry a terrible aura; they have no idea of what they’re facing.

Now, after a long delay, we flash back to Hitler’s rise. The Führer’s strategy, funded by the rich, is seen as a deliberate mobilization of just these tribal “facts” for the sole end of acquiring power. And where that process ends is the death camp. In a chilling visual refrain, the happy American toddlers are compared to troops of children marched along barbed wire.

The narrative spirals back to the beginning. Again we see Hitler defeated, again ecstatic celebrations–but not, as before, among civilians in cities. Instead, we see Russian and American soldiers fraternizing, and included in this mix is the black pilot, smiling serenely in his cockpit. His presence was foreshadowed by swooping aerial shots of the beginning. Now we’re back to the present, and he’s looking for work. No luck; maybe he can be a porter? A new montage generalizes his plight: American society refuses to assimilate African Americans. A savage cut takes us from a room full of white secretaries to a cotton field–the only work available for people who participated as fully in the war effort as anyone.

Now the early montage of Jim Crow images is recalled in a poetic string of associations on the word word, from Hitler’s control of The Word to signs barring blacks from entry, ending with inscriptions etched on forearms.

The final images of passersby, filmed unawares, replace the newsstand of the opening with shop windows as they peer inside. The sequence uncannily predicts the explosive consumer society that would follow in the war’s wake. Again, though, a shadow falls over the postwar world. Hurwitz daringly intercuts the intent window-shoppers with the plunder of the camps–hair, jewelry–and the numbers on inmate uniforms, as if these were commodities on display.

The war against inhumanity is far from over. Americans will need to be more than curious consumers if they are to face the struggle that lies ahead.

16 March 2016. UW-Madison police are investigating an act of racist vandalism that was committed earlier this week on campus, officials confirmed Wednesday. The drawing, which was found in a men’s bathroom in the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, shows a stick figure hanging from a noose in a tree with the word “nigger” written next to it. UW police spokesman Marc Lovicott says the vandalism was reported at about 7:20 p.m. on Monday and is believed to have occurred some time between 3:30 and 7 p.m. that same day. (Photo by Marla DG on Twitter.)

16 March 2016. UW-Madison police are investigating an act of racist vandalism that was committed earlier this week on campus, officials confirmed Wednesday. The drawing, which was found in a men’s bathroom in the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, shows a stick figure hanging from a noose in a tree with the word “nigger” written next to it. UW police spokesman Marc Lovicott says the vandalism was reported at about 7:20 p.m. on Monday and is believed to have occurred some time between 3:30 and 7 p.m. that same day. (Photo by Marla DG on Twitter.)

Strange Victory is, it seems to me, the essential documentary of our moment. A nearly seventy-year-old film can remind us that, as the narration puts it, “hopelessness is next door to hysteria.” The frustrations, despair, and hatreds that surfaced during Obama’s tenure have crystallized in an American fascist movement of unprecedented breadth. The film reminds us that scapegoating is eternal, sometimes summoned quietly (they’re not like us, she’s a traitor, he knows exactly what he’s doing), sometimes conjured up in full fury. At a moment when America is one IS attack away from a Trump or Cruz presidency, it’s good to be reminded how the well-funded Hitler exploited Us vs. Them. Temporizing pundits give every sufficiently funded lunatic the benefit of straight-faced interviews, or even tongue-baths. Right-wing politicians and agitators, keen on power and uncommitted to principle, are ready to fall in line behind a leader if he might win. Forget Godwin’s Law. Facing today’s assault on peace and justice, Strange Victory can rekindle our energies, without a moment to lose.

The crematorium is no longer in use. The devices of the Nazis are out of date. Nine million dead haunt this landscape. Who is on the lookout from this strange tower to warn us of the coming of new executioners? Are their faces really different from our own? Somewhere among us, there are lucky Kapos, reinstated officers, and unknown informers. There are those who refused to believe this, or believed it only from time to time. And there are those of us who sincerely look upon the ruins today, as if the old concentration camp monster were dead and buried beneath them. Those who pretend to take hope again as the image fades, as though there were a cure for the plague of these camps. Those of us who pretend to believe that all this happened only once, at a certain time and in a certain place, and those who refuse to see, who do not hear the cry to the end of time.

Milestone, who gave us the restored Portrait of Jason, has provided a very full presskit for Strange Victory here. My final quotation comes from Jean Cayrol’s text for Night and Fog (1955).

Strange Victory (1948).

Little stabs at happiness 6: Breathe

Commander in Chief (2020).

Last summer, in hope of reviving spirits in these times, I ran a series of clips I admired for their ability to arouse and energize. They created a sort of disciplined exhilaration through adroit editing, camerawork, and music. They reliably gave me a lift, and maybe you too.

Now, in the Caligula phase of Trump’s presidency, it seems appropriate to pay my respects to a masterpiece of engaging agitprop. I’ve registered my reservations about the Lincoln Project in an earlier entry, but there’s no denying that these walking wounded of right-wing partisanship have recruited some very talented filmmakers. Their “Covita” assemblage was superb, and they have outdone themselves with this morning’s triumph.

Here it is:

Experience it–but then we should study it.

It’s an excellent example of what we call in Film Art associational form–a blending of images, sounds, and texts to imply ideas and provoke feelings, in the manner of lyric poetry. The text itself is a lyric poem, at once ode, elegy, and apostrophe. Demi Lovato’s choked, rising and falling vibrato is in itself powerfully expressive. Just as important, the audiovisual texture enriches the text. Sometimes it’s a matter of the image echoing the words, and sometimes the associations are purely visual. An element in one shot, such as a gesture or facial expression, will call up something similar, or a contrast.

The effects flash by quickly. Taken just as images, what do these shots have in common?

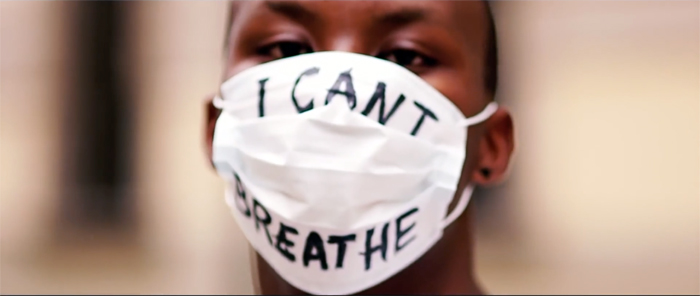

Nothing but a pulse: Labored breathing on a ventilator matches the flicker of an emergency vehicle’s turn signal, as if life is running out before our eyes..

The structure mimics the song’s layout. We move from problem to solution, from crisis to resistance, from emptiness to crowds, ending on a resolution that puts action in the hands of the viewer. Threading it all together is the way “I can’t breathe” gets redefined. The phrase shifts from being associated with George Floyd and other victims of police atrocities, to the COVID-19 pandemic, before adding a twist: Trump’s own bout with the virus, capped in a direct address to him. How does it feel to be able to breathe? By the end breathing becomes metaphorically linked to voting. How does that feel?

As I mentioned in that earlier entry, contemporary agitprop reminds us how much every filmmaker owes to traditions. The techniques used in Commander in Chief stretch far back into the history of cinema; the upraised fists of the finale could have come straight out of Soviet montage.

It might seem pedantic to talk this way about such a powerful piece of cinema. But the point is that the things we study are really out there, crafted by creative filmmakers and having an impact on viewers. The art we care about has concrete effects, and in studying it we can clarify just how those effects are achieved. Analyzing forms and styles can broaden our sense of what cinema can do, and it can strengthen our respect for the filmmakers who explore it.

A similar analysis could be undertaken with many of the best current polemical documentaries, like Unfit and Totally Under Control. These galvanize us not just through their subjects and “messages” but through their fresh use of conventions of form and style. (The sequences of Totally Under Control devoted to First Capon Jared Kushner will remain models of satiric montage.) As with the best of Adam Curtis’s work, these are important contributions not just to political discourse but to the history of film as an art form.

Those goosebumps, that quivering gut, those tears? They come from cinema, grand synthesis of the arts.

Another documentary working in this vein, Leo Hurwitz’s Strange Victory, is discussed here. It’s completely appropriate to our current crisis.

For other reflections on the Trump coup attempt, go here and here and here and here.

P.S. 9 December 2020: After winning an Advertising Age award for the Lincoln Project campaign videos, Rick Wilson explains the strategy and assesses their success in the first of four parts.

P.P.S. 24 December 2020: More backstory on the making of these videos from producer/director Ben Howe.

Totally Under Control (2020).

Vancouver: “It’s the Arts”

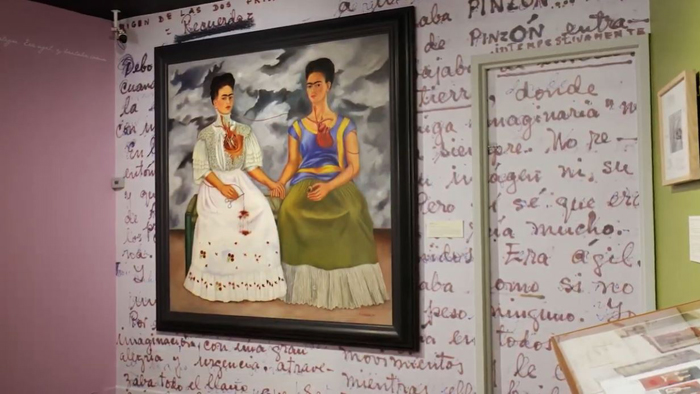

Frida Kahlo (2020)

Kristin here:

I wonder how many of my readers will recognize the source of this entry’s title. Is Monty Python’s Flying Circus still the perennial classic it was among young people for decades after its original series was broadcast? That brief sentence was the title of the sixth episode of the first season, shown in 1969, though I didn’t see it until some years later. The episode itself has little to do with the arts, but for some reason that particular title stuck with David and me, as few if any others did. Whenever we have encountered a TV program or a review, often something pretentious, one of us will turn to the other, or both simultaneously, and say, “It’s the Arts!”

The Vancouver International Film Festival has an admirable custom of showing many documentaries. They often deal with ecological issues and Canadian subject matter. One prominent thread, however, is documentaries about the arts. These are known as MAD, or “Music, Art and Design.” Although, as I mentioned in my previous entry, I tend to stick to the Panorama program of international fiction films, I always try to attend a few of these arts documentaries when they fit in with my interests. Most of these are in fact wonderful, not pretentious. Still, I am too accustomed to the phrase, and I think automatically, “It’s the Arts.”

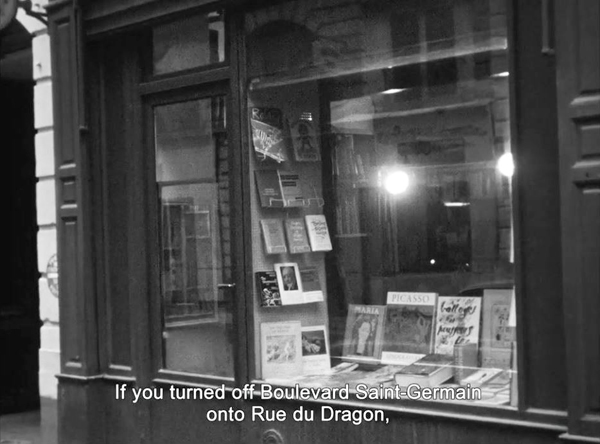

Paris Calligrammes (2019)

One documentary that I was keen to see is Ulrike Ottinger’s autobiographical account of her years living in Paris during the 1960s. Ottinger is known, at least in the US, primarily for her experimental fiction films, like Freak Orlando (1981) and Joan of Arc of Mongolia (1989). I had not encountered her work since then and was eager to catch up with her at this year’s festival.

Ottinger did what many young people think of doing but never carry through on. She left home at the tender age of twenty for an exciting new life. In 1962, she moved from Germany to Paris, where she lived until 1969 before returning to West Germany. In France she lived among Bohemians and stayed long enough to witness the protests of May, 1968.

Naturally she was hugely influenced by her experiences. She tells of encountering artists and ideas: “In my euphoria, I wanted to convert all my experiences directly into art.” But how? Early on, she muses on how to convey those experiences of decades ago:

I ask myself that same question over fifty years later. How can I make a film from the perspective of a very young artist I remember, with the experience of the older artist I am today? In Paris, I followed in the footsteps of my heroines and heroes. Wherever I found them, they will appear in this film.

There is no footage of Ottinger from this period, and relatively few relevant photographs. Instead she wisely organizes the early portions of the film around her connection to an extraordinary bookshop that was a center of artistic and intellectual life at the time: Calligrammes (above), founded in 1951 by Fritz Picard, who had fled Nazi Germany in 1938. As a dealer in rare German and other books on the arts, Picard became host to innumerable avant-garde artists and intellectuals. Ottinger recalls buying many books on the German Expressionists and other avant-garde artists and movements of earlier decades.

(David bought some books for his dissertation on French Impressionist cinema at Calligrammes in the summer of 1973. Picard died in November of that year, though the shop was continued for a time by others.)

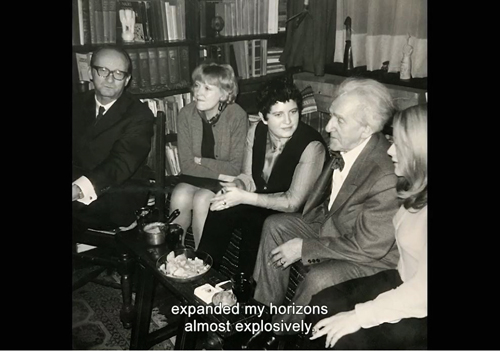

Ottinger became a friend of Picard and socialized with the patrons and visitors of the shop. Below, she’s in the black vest, sitting beside Picard at a party. She also was indirectly influenced by the great artists of the past, such as Hans Richter, who had frequented Calligrammes. In one sequence she flips through the guest-book signed by many a famous visitor, and we see clips from films like Ghosts before Breakfast, which influenced her.

Following this section, Ottinger gives us sequences on the effects of the Algierian war on her friends in Paris and describes the protests of May, 1968, some of which she was able to see from her apartment near the Sorbonne.

Perhaps inevitably, Paris Calligrammes reminded me of some of the Agnès Varda’s late autobiographical work. Ottinger is less lyrical and personal, as well as being more overtly political. There is more of a sense of name-dropping, at least in the early section. Still, who wouldn’t be interested in hearing about the early life of someone who has had such adventures? Ottinger also describes the influences on her by the artists she learned about and met. The brief clips from her own films should inspire a new generation of film buffs to seek out her work.

Like so many of the films at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year, Paris Calligrammes was shown in Berlin. For an enthusiastic and informative review done at the time, see Richard Brody’s piece in The New Yorker.

Marcel Duchamp: The Art of the Possible (2020)

I am of two minds about Matthew Taylor’s documentary on Duchamp. It presents an excellent overview of the artist’s career and work, and one could learn a great deal from it. It makes clear, for example, the relationship between Duchamp’s early ready-mades and the fact that they were mostly subsequently lost and much later replaced by replicas–all with the artist’s cooperation. It puts his important early painting “Nude Descending a Staircase” (see bottom) in its historical context.

There are the usual experts explaining Duchamp’s intellectual approach to his artworks and his considerable influence on subsequent generations. We are not given much indication concerning who some of these experts are. The identifying labels often just say “Curator” or “Art historian” without linking the experts to any institution or publication. I tried looking one of them up on the internet and couldn’t find him. I’m sure, however, that they know Duchamp’s life and work well.

These experts are also almost all extremely enthusiastic about Duchamp’s work and especially the impact he has had upon art–not, as they emphasize, just specific trends but absolutely all subsequent art up to the present. Early on in the film, before we have been introduced to most of the talking heads, a voiceover declares, “Without him, imagine where we would be. We’d be painting in the style of Matisse or Picasso. That’s what modern art would be without Duchamp.”

(Ironic note: Duchamp’s stepson, Paul Matisse, is the grandson of Henri Matisse.)

That’s a pretty remarkable claim. It’s hard to think of a period that long in the post-Medieval era when art has just frozen in place for a century. Surely innovative styles and individual artists would have come along and produced distinctive work that did not depend on Duchamp’s main claim to fame, his demonstration that anything could become an artwork if we regard it as such. Did the Soviet Constructivists depend on Duchamp’s idea? Did the German Expressionists? Do highly individualistic artists? (See the section below.) Do manga and graphic novels, which are coming to be thought of as worthy of attention as art–not just because someone found them and declared them so, but because they contains qualities that were considered artistic well before Duchamp?

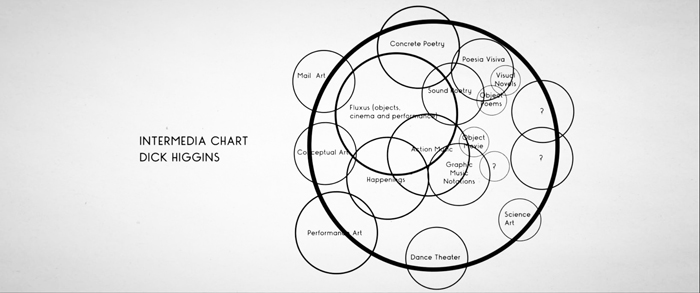

To be sure, Duchamp did have a huge impact, as this chart, shown in the film, suggests. It was devised by Dick Higgins, artist and co-founder of Fluxus. (The absence of Pop Art among the circles is rather puzzling, though it does figure in the film.) One could, however, devise many other circles for trends and institutions that do not reflect that impact.

Toward the end of the film, the experts go further, suggesting that Duchamp encourages the democratization of art by suggesting that anyone can be an artist, whether on their own or by taking and re-purposing existing artworks or objects or sounds. Yet would we say that the many outsider artists of the past century who have come to the recent attention of taste-makers had anything to do with Duchamp? And fanart, if that is included in this vast generalization, existed before Duchamp.

Despite the obvious excitement the experts display in extolling Duchamp’s work, someone watching the film might be less sympathetic, given the debatable state into which Postmodernism in general has led the art world. As one inevitably thinks, what’s next, Post-Postmodernism?

Duchamp himself seems, according to the film, to have had considerably less enthusiasm about his own artworks, preferring perhaps the idea of them rather than the execution. He took twelve years to complete the Great Glass and declared himself pleased with the results when an accident severely cracked its surface. He did not bother to keep track of his ready-mades, most of which disappeared. One wonders why he bothered to follow the initial venture into that area with “Fountain” (a urinal signed “R. Mutt 1911”), since subsequent ready-mades like “Hat Rack” (above) make the same intellectual point.

Late in life Duchamp seemingly gave up art-making to devote himself to competitive chess. After his death it turned out that from 1946 to 1966 he had been working on “Étant donnés,” a peep-show view of a spreadeagled nude woman, based on his mistress during part of that time. Despite the raptures expressed by the experts, it looks like it could be considered revenge porn. But only, presumably, if one calls it that.

Only one of the experts, Peter Goulds, departs from the general unquestioning idolization of Duchamp. Near the end he says,

Later in life, of course, he must have found it incredibly amusing to hear people latch onto his theories as though they were universal truths, when actually his whole life was about bucking those very conventions and defying them. So I’d like to suggest that his form of so-called conceptual art was a much more playful exchange. I’m not so sure about how even serious he was about it himself. Here he throws these things out as suggestions, with thought. Others, perhaps more needy than himself, would make these rules be therefore solely applicable.

Frida Kahlo (2020)

Frida Kahlo is one of those artists who don’t appear to owe much, if anything to the influence of Marcel Duchamp. As the film makes clear from the start, she was aware of European artistic movements and developments. Still, neither she nor her husband, muralist Diego Rivera, seem to have absorbed much from them. Kahlo always denied that her later work was Surrealistic, and one might rather attribute its fantastical elements derive more from the Latin American tradition of Magical Realism.

Indeed, the whole idea that Duchamp influenced all of modern art comes to seem remarkably Amero- and Euro-centric if one considers that it implicitly either scoops highly individual artists like Kahlo up into one enormous category or eliminates them from that category altogether.

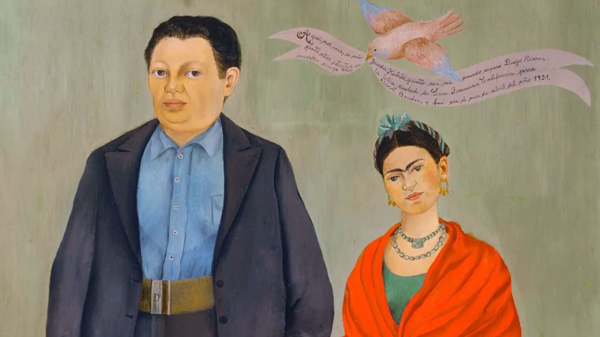

I found Frida Kahlo more satisfying than Marcel Duchamp. Its experts are all clearly identified as to their position and institution. Some are curators of the institutions which own her works, such as the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City. There “The Two Fridas” is shown (see top) as the curator discusses it.

These experts are as enthusiastic about their subject as those in the Duchamp film, but they are focused entirely on recounting Kahlo’s life, her social context, and the influences on and changes in her style across her life. For example the simple presentation of “Frida and Diego Rivera,” an early portrait done shortly after their marriage, gives way to the more sophisticated and symbolic “The Two Fridas.”

Archival photographs and film clips illustrate the eras of the places where Kahlo lived and traveled. The impact of the lingering effects of her injuries in an extremely serious traffic accident in her youth, her travels with Rivera in the US, and the rockiness of their marriage are all discussed to help clarify the often cryptic visual references in her paintings.

In short, Frida Kahlo is a model of a staightforward and informative documentary on an artist. I was pleased to be introduced by it to its producers, Exhibition on Screen. In business since 2011, it has made twenty-six such documentaries. These are shown in theaters and festivals initially, before being made available on disc and streaming on their website. Frida Kahlo is promised for streaming on October 20.

Once again, thanks, as usual to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Jane Harrison, Curtis Woloschuk, and their colleagues for their help during the festival.

Marcel Duchamp: The Art of the Possible (2020)