Archive for the 'Art cinema' Category

More of the world in a multiplex: another dispatch from Vancouver

Kristin here:

Latin America

In my first report, I mentioned that the Iranian film A Respectable Family was an unexpected gem. I’ve come across another, the Brazilian film, Neighboring Sounds (2012). It has a remarkable formal device that unfortunately I can’t disclose without ruining the film for those who haven’t seen it. It’s a technique that takes a while to figure out, since it’s cumulative. (Fortunately, unlike with A Respectable Family, I have yet to find a review or program note that mentions it.)

The film is set in Recife, the fifth largest city in Brazil. It centers around members of two families living in a complex of smaller, older houses surrounded by new condo high-rises that will eventually swallow the entire area. (The image above vividly shows the juxtaposition.) The divide between rich and poor is extreme, however, and the residents live in fear of crime, with elaborate gates and with grilles over their windows. Suspense is generated when a small group of men offer their services to provide security for the block, and once they are hired, we are left for a long time to wonder whether this is a cover for some other devious purpose.

The film is beautifully shot, taking advantage of the abstract compositions created by the modern apartment blocks and their glass windows and doors. As director Kleber Mendonça Filho says in the online press kit, “Architecture gone wrong is a nuisance, but extremely photogenic.”

The film’s title is taken literally, with many layers of offscreen sounds from nearby houses and streets forming much of the soundtrack. The complex use of Dolby Surround makes it especially desirable to view and listen to this film in a theater.

Neighboring Sounds has been picked up for US distribution by the Cinema Guild, which has handled other films we’ve enjoyed here in Vancouver , most notably Once upon a Time in Anatolia and The Strange Case of Angelica (and written about here and here, both available on DVD and Blu-ray.)

The Chilean film No (2012), starring Gael Garcia Bernal, has already gained a high reputation on the festival scene. (Like A Respectable Family, it was shown in the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes.) David and I both thought it lived up to its buzz.

The plot deals with the 1988 referendum as to whether dictator Augusto Pinochet would remain in power. The side campaigning for the “no” vote was allowed a single 15-minute TV commercial each evening. Bernal plays a successful director of TV ads, Rene, who is lured into devising this commerical; he’s introduced showing off his latest spot for “Free” cola. He conceives of a campaign based on breezy optimism, with musical numbers (below right) and shots of cheerful workers acting as if Pinochet is already out of office. His tactics disgust several of the left-wing party leaders, as well as Rene’s estranged wife.

Technically the film is cleverly done. It was shot on old-fashioned U-matic video and shown in Academy ratio (not exactly reflected in these frames from the online trailer). Fuzzy images with occasional overexposure and other video artifacts not only suggest a period piece, but they also allow director Pablo Larraín (Tony Manero, Post Mortem) to seamlessly edit in historical footage of Pinochet and street clashes from 1988. No generates considerable suspense as well, whether or not one knows how the referendum turned out.

Sony Pictures Classics picked up No at Cannes and currently lists its release date as to be announced; according to IMDB, it will have a limited release in the USA on February 15.

Europe

A Royal Affair (2012, Nikolaj Arcel) has been chosen as Denmark’s entry for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar. Of course, the long list of entries from various countries will be reduced to five before the voting occurs. Still, I wouldn’t be surprised if A Royal Affair ended up on the final list and even took the top award. In a way, it’s just what the Academy members like: a big, glossy costume drama based on uplifting historical events.

But I was relieved to discover that this is no Merchant-and-Ivory-style middle-brow adaptation. It’s a fascinating example of what happens when a bunch of leftist, cutting-edge filmmakers get their hands on a budget to make an historical epic. Although the film’s title and publicity center on the illicit romance that provides part of the drama, A Royal Affair focuses largely on politics. Its plot is loosely based on historical events during the Age of Enlightenment, during which Denmark initially remained a backward country based on serfdom, summary arrest, torture, and execution, and grinding poverty for the lower classes.

The opening shows the heroine, Caroline, born an English princess and wed to Danish King Christian VII, writing the story of her life for her children. A flashback then begins the story proper, with Caroline optimistically setting out for Denmark and quickly discovering that her husband is an impetuous, rude and possibly insane young man who cares nothing for her. Her loneliness and the backward situation in Denmark are gradually established. Eventually a young doctor, Struensee, who believes in the ideas of the Enlightenment philosophers, comes to court and befriends the king, helping him to behave in a more restrained fashion.

Caroline, too, is a devotee of Rousseau, Voltaire, and other authors whose works are banned in Denmark. Nearly an hour  into the film, she discovers that Struensee is of like mind, and a friendship gradually moves into love and a sexual affair. The couple manipulate Christian into passing laws to benefit the peasants, earning the ire of the nobility. The narrative continues to center more on the social struggle that the three carry out than it does on the romance plotline.

into the film, she discovers that Struensee is of like mind, and a friendship gradually moves into love and a sexual affair. The couple manipulate Christian into passing laws to benefit the peasants, earning the ire of the nobility. The narrative continues to center more on the social struggle that the three carry out than it does on the romance plotline.

When I heard that the Silver Bear for Best Actor was awarded to the film at Berlin, I assumed it went to Mads Mikkelsen, who plays Struensee–and seems to star in half the films coming out of Denmark these days (such as Thomas Vinterberg’s The Hunt, also shown this year in the festival). But the role of Christian VII actually seemed to me more challenging. Mikkel Boe Følsgaard has to play a character who begins as border-line insane, crude, and obnoxious, but who also must gain our sympathy when he becomes part of the plot to reform Denmark’s laws. I was delighted to learn upon further inquiry that is was in fact Følsgaard (on the left, with Mikkelsen, in the photo) who won the award. Well deserved.

As the image suggests, the film is shot in muted tones that tend to play down the costumes and sets more than historical dramas usually do. This approach helps direct our attention to the plot and politics rather than the pageantry. In short, I ended up liking the film much more than I expected to.

A Royal Affair will be released in the USA on November 9 by Magnolia Pictures.

At the other end of the budgetary scale is the Portuguese feature The Last Time I Saw Macao (2012, co-directed by João Pedro Rodrigues and João Rui Guerra da Mata). A common impulse among critics seems to be to compare this mysterious, lyrical film to some of Chris Marker’s works. There is little information available on it, but my impression was that the filmmakers shot a lot of lyrical footage of Macau and then concocted a story to fit it. There are shots of buildings, from skyscrapers to disreputable-looking back streets, as well as ephemeral items like some big, gaudy, cartoony balloons of tigers that decorated the streets for a local festival.

The plot has something to do with a mysterious gang, the Chinese zodiac (see image at the bottom), and the end of the world. The hero is barely glimpsed, narrating the story in voiceover (provided by both of the directors). The plot centers on his search for a transvestite named Candy, perhaps the “woman” seen performing a musical number in front of a cage containing live tigers in the sultry opening scene. The song, “You Kill Me,” is among several references to Josef von Sternberg’s Macao.

Despite the shoestring budget, the filmmakers manage convincingly to portray an apocalyptic destruction of the city, followed by bleak shots of deserted, early-morning Macao buildings that effectively suggest the aftermath. It reminded me of Godard’s depiction of a futuristic city in Alphaville, using contemporary buildings and highways.

No US release is planned, but The Last Time I Saw Macao is worth seeking out at upcoming festivals.

A Filmmaker of the World

I’ve mentioned some films that pleasantly surprised me, but almost certainly the best film we saw at Vancouver came as no surprise at all. We both loved Abbas Kiarostami’s Like Someone in Love, but we’re not going to write anything substantive about it, at least not now. It deserves another viewing or two before we could say anything worthwhile–and it hardly needs us to publicize it. The opening scene is fabulous, the subsequent rambling plot absorbing and intriguing, and the end, as so often happens with Kiarostami, puzzling and frustrating. Possibly the man can do no wrong.

IFC has theatrical rights for the USA. Currently its webpage announces “Coming in 2013.” This may mean primarily On Demand, though it would be a pity not to see Like Someone in Love on the big screen.

The end of one multiplex

Rumors circulated almost from the start of the festival, and on October 8 the festival’s director, Alan Franey, revealed officially that the Empire Granville will soon be closing down. A detailed story on the history of the Granville and its closing, with quotations from Franey and representatives of other film festivals that have used the venue, can be found here. Ideally next year’s festival will house most of its screenings in another of the city’s multiplexes, but the new venue is yet to be determined. We hope it will be someplace where we can bounce around the world from screen to screen as easily. The Granville has served us all well and will be missed.

Pandora’s digital box: Art house, smart house

The Art Theater, Champaign, Illinois. Photo by Sanford Hess, reproduced with permission.

DB here:

Theatres’ conversion from 35mm film to digital presentation was designed by and for an industry that deals in mass output, saturation releases, and quick turnover. A movie comes out on Friday, fills as many as 4,000 screens around the country, makes most of its money within a month or less, and then shows up on VoD, PPV, DVD, or some other acronym. The ancillary outlets yield much more revenue to the studios, but the theatrical release is crucial in establishing awareness of the film.

Given this shock-and-awe business plan, movies on film stock look wasteful. You make, ship, and store several thousand 35mm prints that will be worthless in a few months. (I’ve seen trash bags stuffed with Harry Potter reels destined for destruction.) Pushing a movie in and out of multiplexes on digital files makes more sense.

After a decade of preparation, digital projection became the dominant mode last year. Today “digital prints” come in on hard drives called Digital Cinema Packages (DCPs) and are loaded (“ingested”) into servers that feed the projector. The DCPs are heavily encrypted and need to be opened with passkeys transmitted by email or phone. The format is 2K projection, more or less to specifications laid down by the Digital Cinema Initiatives (DCI) group, a consortium of the major distributors.

Upgrading to a DCI-compliant system can cost $50,000-$100,000 per screen. How to pay for it? If the exhibitor doesn’t buy the equipment outright, it can be purchased through a subsidy called the Virtual Print Fee. The exhibitor can select gear to be supplied by a third party, who collects payment from the major companies and applies it to the cost of the equipment. The fee is paid each time the exhibitor books a title from one of the majors. See my blogs here and here for more background.

It’s comparatively easy for chains like Regal and AMC, which control 12,000 screens (nearly one-third of the US and Canadian total), to make the digital switchover efficiently. Solid capitalization and investment support, economies of scale, and cooperation with manufacturers allow the big chains to afford the upgrade. But what about other kinds of exhibition? I’ve already looked at the bumpy rise of digital on the festival scene. There are also art houses and repertory cinemas, and here one hears some very strong concerns about the changeover. “Art houses are not going to be able to do this,” predicts one participant. “We will lose a lot of little theatres across the country.”

The long, long tail

‘Plexes, whether multi- or mega-, tend to look alike. But art and rep houses have personality, even flair.

One might be a 1930s picture palace saved from the wrecking ball and renovated as a site of local history and a center for the performing arts. Another might be a sagging two-screener from the 1970s spiffed up and offering buns and designer coffees. Another might look like a decaying porn venue or a Cape Cod amateur playhouse (even though it’s in Seattle). The screen might be in a museum auditorium or a campus lecture hall. When an art house is built from scratch, it’s likely to have a gallery atmosphere. Our Madison, Wisconsin Sundance six-screener hangs good art on the walls and provides café food to kids in black bent over their Macs.

Most of these theatres are in urban centers, some are in the suburbs, and a surprising number are rural. Most boast only one or two screens. Most are independent, but a few belong to chains like Landmark and Sundance. Some are privately held and aiming for profit, but many, perhaps most, are not-for-profit, usually owned by a civic group or municipality.

What unites them is what they show. They play films in foreign languages and British English. They show independent US dramas and comedies, documentaries, revivals, and restorations.

In the whole market, art houses are a blip. Figures are hard to come by, but Jack Foley, head of domestic distribution for Focus Features, estimates that there are about 250 core art-house screens. In addition, other venues present art house product on an occasional basis or as part of cultural center programming.

Art house and repertory titles contribute very little to the $9 billion in ticket sales of the domestic theatrical market. Of the 100 top-grossing US theatrical releases in 2011, only six were art-house fare: The King’s Speech, Black Swan, Midnight in Paris, Hanna, The Descendants, and Drive. Taken together, they yielded about $309 million, which is $40 million less than Transformers: Dark of the Moon took in all by itself. And these figures represent grosses; only about half of ticket revenues are passed to the distributor.

More strictly art-house items like Take Shelter, Potiche, Bill Cunningham New York, Senna, Snow Flower and the Secret Fan, Certified Copy, Page One, The Women on the 6th Floor, and Meek’s Cutoff took in only one to two million dollars each. Other “specialty titles” grossed much less. Miranda July’s The Future attracted about half a million dollars, Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives grossed $184,000, and Godard’s Film Socialisme took in less than $35,000. For the distributors, art films retrieve their costs in ancillaries, like DVD and home video, but the theatres don’t have that cushion.

Something else sets the art and rep houses apart from the ‘plexes: The audience. It’s well-educated, comparatively affluent, and above all older. Juliet Goodfriend’s survey of art house operators indicates that only about 13% of patrons are children and high-school and college students. The rest are adults. A third of the total are over sixty-five. As she puts it, “Thank God for the seniors!” However much they like popcorn, they love chocolate-covered almonds.

Almonds aside, how will these venues cope with digital? To find out, I went to Utah.

Harmonic Convergence

Tim League, Alamo Draft House, during his keynote address at the Art House Convergence.

Five years ago, the Sundance Institute founded the Art House Project, a group of theatres that could screen a tour of Sundance Festival films. The original members recognized the advantages of collaborating, and Russ Collins of the Michigan Theatre organized an annual meeting held just before the festival. In its first year, 2008, the Art House Convergence attracted twenty-two people. This year it drew nearly three hundred—not only programmers and operators and major speakers, but delegates from distribution companies, service firms, and equipment manufacturers. To my eye, it’s becoming an informal trade association.

My three and a half days at the Convergence in Midway, Utah filled me with information and energy. Having attended one of the classic art theatres in my youth, the Little Theatre in Rochester, New York, I’ve been a patron in this sector for fifty years. But I never really met the people behind the scenes. This bunch is exuberant and committed to sharing their love of cinema. They want to watch a movie surprise and delight their audiences. Ideally, the customers would so completely trust the programmer’s judgment that they would come to that theatre without knowing what’s playing.

If you wonder where old-fashioned movie showmanship went, look here. These folks mount trivia contests, membership drives, singalongs. They help out with local film festivals. They bring in filmmakers and local experts for Q & A sessions. They screen those plays, operas, ballets, and concerts that attract a broader arts audience. The bigger entities, like the Bryn Mawr Film Institute and the Jacob Burns Film Center, offer courses in filmmaking and appreciation, along with special events for children, teenagers, and other sectors of the community.

Everything is about localism. These people know their customers, often by name. They sense the currents of taste crisscrossing their town. The success of the Alamo Draft House reveals that Austin has a demographic hungry for the kung-fu classic Dreadnaught, an Anchorman quote-along, or a compilation of the worst CGI work in film history. In LA, The Cinefamily attracts a crowd ready to watch Film Socialisme alongside Battle Royale, Pat O’Neill films, and the 1927 Casanova. “Mission” was a word heard often heard in Midway. These people aren’t only about making money but about weaving unusual cinema into the fabric of their town’s culture and subcultures.

The classic art house was mission-driven too, and it could pay a little as well. Before the advent of videotape, you could make decent money showing Ealing comedies, Fellini, and Bergman years after their initial release. Some exhibitors continue as profit-driven businesses. But many, perhaps most, people in the Project operate not-for-profit venues. The cinemas are funded by donations, foundations, and government agencies, such as arts councils. Russ Collins has argued for embracing this trend.

“New model” Art House cinemas are community-based and mission-driven. . . . Most “new model” Art House cinemas are non-profit organizations managed by professionals who are expert in community-based cinema programming, volunteer management and the solicitation of philanthropic support from local cinephiles and community mavens.

Russ points out that over the twentieth century, opera, theatre, and other sectors of the performing arts have moved toward non-profit status. “If it makes sense that if music has a range from very commercial to very subsidized, film should too. There are all kinds of movies, and there should be all kinds of outlets.” The University of Wisconsin–Madison Cinematheque and the Wisconsin Film Festival have shown me that this strategy can work—again, if the programming meshes with the tastes of its community.

There are clouds on the horizon, of course. Gary Palmucci of Kino Lorber recalled a line from Irvin Shapiro, who distributed foreign-language films for fifty years: “When were there ever not problems?”

For example, the baby-boomers, cinephiles since the ‘60s, are likely to be around for ten or fifteen more years. Where will new patrons come from? When I was in college, you scheduled your life around theatres’ showtimes, but younger people have gotten used to time shifting and on-demand access via tape, disc, cable, or the Web. A more worrisome sign: even in art houses near college campuses, students tend to make up a small fraction of the audience. The next few years will tell if changed tastes, along the habit of unbridled access to movies, will keep an aging Gen X from the art house.

More pressing the problem is digital conversion. It was the topic of two information-filled sessions at the Convergence, and it came up often during other panels.

Where do they get those movies?

An AHC panel: Russ Collins, Ira Deutchman (Emerging Pictures), Jeff Lipsky (Adopt Films), and Gary Palmucci (Kino Lorber).

Historically, most major new film technology was introduced in the production sector and resisted in the exhibition sector. Exhibitors have been right to be conservative. Any tinkering with their business, especially if it involves massive conversion of equipment and auditoriums, can be costly. If the technology doesn’t catch on, as 3D didn’t in the 1950s, millions of dollars can be wasted.

Shooting movies on digital was no threat to theatres as long as 35mm prints were the standard for screening. But distribution has long been the most powerful and profitable sector of the film industry. Today’s major film companies—Warners, Paramount, Sony et al.—dominate the market through distribution. So when the Majors established the Digital Cinema Initiatives (DCI) standards, exhibitors had to adjust.

Since distributors call the tune, let’s look at the different digital alternatives available.

Mainstream commercial films from the major studios are currently distributed in both 35mm copies and digital copies. But at some point fairly soon, the majors will cease releasing 35mm. Twentieth Century Fox has taken the lead in declaring that at the end of this year it will circulate no more film prints. John Fithian, the plain-spoken President of the National Association of Theatre Owners, said in March of 2011:

Based on our assessment of the roll-out schedule and our conversations with our distribution partners, I believe that film prints could be unavailable as early as the end of 2013. Simply put, if you don’t make the decision to get on the digital train soon, you will be making the decision to get out of the business.

This means that the theatre will require full 2K/4K projection, and the exhibitor will need a DCI-compliant projector and a server for every screen. To pay for the upgrade, many exhibitors will want to take advantage of the Virtual Print Fee. But many VPF programs have set their signup deadlines during this year.

Arthouse films distributed by studio subsidiaries are the tentpoles and blockbusters of the arthouse market. Sony Pictures Classics, Universal Focus, and Fox Searchlight usually furnish the most desirable pictures for these screens. Add in certain titles supplied by “mini-majors” like Relativity, The Weinstein Company, and Lionsgate/ Summit. This season, for instance, art houses would have suffered without Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (Focus), The Descendants (Fox Searchlight), A Dangerous Method and The Skin I Live In (SPC), and The Iron Lady, The Artist, and My Week with Marilyn (Weinstein).

As far as I can determine, all these firms currently supply 35mm prints. Jack Foley of Focus recognizes that film copies remain the default for most art houses. For Focus, 35mm circulation makes sense because many films play widely enough and roll out slowly enough to amortize print costs.

Focus will be patient with its core customers and their financial challenges in going digital. . . . Supplying them with 35mm in the meantime allows us to play them and play them cheaply by using prints multiple times at no cost more than shipping.

But studio subsidiaries must also provide the DCI-compliant Digital Cinema Packages. Some art houses have converted and can handle them. More important, many of these films play in “smart houses.” These are screens, located in a mainstream multiplex, that will show films that get good response in art-house runs. If a movie has crossover appeal, a smart house can hold it long enough to build word of mouth. Right now, several multiplexes are playing Tinker Tailor, The Descendants, My Week with Marilyn, and the like. There are, Jack Foley estimates, between 250 and 500 screens of this sort in the country.

Smart houses, as parts of multiplex circuits, are usually showing DCPs. At the moment, Foley points out, the Virtual Print Fee is onerous for non-major distributors, since if they supply a DCP to a theatre, they must pay the fee (often about $850). Foley believes that eventually all viable art houses will convert to DCI projection, the VPFs will expire, and every party will reap the benefits of digital cinema.

Films distributed by smaller, independent distributors offer still other options. These are companies like Kino Lorber, IFC, Magnolia, Strand, Roadside Attractions, Oscilloscope, Zeitgeist, and their peers. They circulate the most offbeat product, dramas like The Messenger and Meek’s Cutoff (Oscilloscope), along with documentaries and foreign titles like Cave of Forgotten Dreams, Pina, and Certified Copy (IFC) and 13 Assassins (Magnolia). Restorations and reissues of classics, such as Metropolis (Kino Lorber) and On the Bowery (Milestone), operate in this sector as well. Like their studio counterparts, these firms need the video aftermarket to support purchasing theatrical rights.

Some of these distributors supply 35mm prints, like Magnolia’s very pretty one of Melancholia that I saw in Madison a few weeks ago. But most Virtual Print Fee agreements apparently demand that if a non-Majors film arrives on DCP and is to be played on a projector financed through the VPF, the independent distributor must chip in the fee. Some are willing to do that.

What surprised me most was learning that independent distributors will supply the film in many digital formats, even Blu-ray and DVD versions. There are now first-run films playing commercial theatres, even in Manhattan, in Blu-ray. On small screens, many exhibitors say, that format works fine and their patrons don’t notice. Many of these films aren’t available on 35mm prints at all, although a distributor may prepare a print if there’s enough interest to help pay for it.

A lateral option, sometimes called i- or e-cinema, also exists. There are now companies offering theatre delivery via the Internet. The idea is to stream encrypted files, in HD, to cinemas signed onto the system. Emerging Pictures, currently the dominant player in this domain, will deliver material from many independent distributors, including Sony Classics, IFC, and Magnolia. Emerging will also supply performing arts shows. Other companies offering or preparing to offer comparable services are Specticast, Proludio and Storming Images.

Summing up: If an art house wants to show only films from the independent, second-tier distributors, then the pressure to convert to DCI isn’t great. The exhibitor will, however, be playing more and more movies on DVD or Blu-ray. But the fact is that one Iron Lady pays for a lot of Take Shelters. The need to show art house blockbusters will eventually push most art-house operators toward buying or leasing the high-end equipment.

In between

Juliet Goodfriend, Art House Convergence. Photo by Chuck Foxen, reproduced with permission.

The new digital problems confronting the art-house market don’t end with decisions about equipment.

For one thing, DCP playback creates a degree of inflexibility that festivals have also encountered. Shifting showtimes and screens is more difficult, as it may require special permission and a new key to open the file. There is, moreover, an air of surveillance that is inimical to the more informal, trust-based atmosphere of most art-cinema milieus.

More constraints appear if the exhibitor chooses to fund the changeover through the Virtual Print Fee. For example, VPFs oblige the exhibitor to screen only films supplied by the major companies–the ones that created the Digital Cinema Initiatives. If an exhibitor wants to play an independent distributor’s title on a DCP, that distributor needs to pay the fee, in effect helping to cover the theatre’s conversion. Other constraints are more obscure. I can’t report reliably on them because when joining a VPF program, the exhibitor signs a non-disclosure agreement pledging not to reveal details of the deal. But hints suggest that exhibitors could be prevented from “splitting,” that is showing two or more films in the same auditorium on one day. This is a practice that many art cinemas rely on because it allows them to vary programs in mid-week, or to compensate for having only one or two screens.

Another effect of the digital revolution comes from streaming, or Video on Demand. Many of the most desirable films from independent distributors are released on VoD simultaneous with or even before theatrical release. At the Convergence, one exhibitor pointed out that Melancholia was available on VoD several weeks before she could play it on her screen.

Distributors offer several justifications for their streaming decisions. Ancillary income from DVD has declined steeply, and VoD pays well. According to Josh Dickey’s Variety article and Daniel Miller’s Hollywood Reporter piece on the rise of VoD deals, Margin Call, which attracted $5.3 million theatrically, took in an estimated $4-$5 million on VoD. Another advantage is that streaming provides fast returns, while any DVD income won’t show up for many months. Moreover, VoD can reach audiences in areas of the country that don’t have art houses. And some distributors believe that the theatrical and VoD audiences don’t significantly overlap. For Margin Call, it’s claimed, most people who saw it in the theatre didn’t know that it was on VoD, and many who caught it on VoD would not have gone to a theatre.

There don’t seem to be any firm conclusions about how much day-and-date or early release on VoD can harm a film’s theatrical release. In the absence of detailed evidence about VoD grosses, exhibitors are understandably nervous.

Finally, what about access to older films in studio collections? These titles are central to repertory cinemas, and many art houses that play recent releases schedule some classics too. Yet some studios are increasingly reluctant to supply 35mm prints from their libraries. If the film isn’t on DCP, exhibitors may be told that they must pay to have a DCP made, or show a Blu-ray or DVD. But repertory cinemas are reluctant to screen on the low-resolution formats, and rarer and more obscure titles are unlikely to be available on disc. Unhappily, we may get less repertory programming on the whole. Audiences that don’t live in a town with an archive or cinematheque will have less chance to discover film history.

A tradition, forced to reconfigure

The energetic arts entrepreneurs who gathered at Midway can claim a proud tradition. The art-house and repertory model of exhibition, originating in the 1920s, came to prominence after World War II. These theatres played imported films from small distributors, with occasional independent items mixed in. A 1949 Variety article noted that the market had a boom that was starting to level off.

Postwar surge of art theatres, born as an outlet for the flock of British and foreign-lingo pix which hit this country after V-J Day, is now slowing to a normal growth. In the U. S. at the present time there are 57 theatres which are out-and-out art houses and 226 additional flickeries which play foreign-made product part of their time. . . . With the exception of Newark. . . every city of 200,000 or over now sports at least one art theatre.

Then as now, these theatres offered a more personal atmosphere and upscale service (tea, coffee). Like today’s art houses, they depended on what we call buzz; their films were very much critic-driven. Then as now, British films could break out, with Henry V (1944), Hamlet (1948), and The Red Shoes (1948) proving very successful. The major studios sensed a new market and began financing and importing films from overseas. This policy has been revived several times since, up to today’s “studio boutiques” like Focus and Sony Classics. And some art-house operators moved into distribution themselves. Exhibitor-distributors like Cinema 5 and New Yorker are the predecessors of IFC and Music Box.

This system of distribution and exhibition has survived six decades. But in that period, art houses haven’t faced any change as sweeping as this. The big distributors have decided on a standard, and the most powerful theatre chains have converted. History suggests that critical mass on this scale is irresistible.

Many major art houses and nonprofits have already converted. Film Forum in New York City, which mixes repertory and new releases, has long had a policy of showing classics on 16mm or 35mm film. But now the theatre is using DCPs; some restorations are not offered on film, and that trend is almost certain to grow. Taking the bull by the horns, Film Forum is running a series, “This is DCP,” to introduce the audience to the format. Bruce Goldstein’s program note asks:

Is watching a DCP the same experience as watching a film print? The jury is still out, so for this one-week series, we’ve chosen the crème de la crème of classics on DCP and have invited Sony Pictures’ Grover Crisp, one of the true giants of film restoration, to explain things on opening weekend. You be the judge.

Exhibitors who haven’t yet converted are raising funds through information campaigns and capital exercises. Single-screeners face the toughest climb. Take the Art Theatre of Champaign, Illinois, seen in my topmost still. It opened in 1913 and has had a pretty typical history (including showing erotic films). Revived as an art house in 1987, it has screened foreign and independent cinema, as well as classics and out-of-the-way items, including a revival of City of Lost Children. Now the Art needs to go digital. Its operator, Sanford Hess, stresses that without the new gear, priced at about $80,000, he will have to close the venue when the lease runs out in December. He has started to rebuild the enterprise as a co-operative. Since the co-op launched in December, 270 people have bought shares, generating about $29,000 toward a new projection system. (You can trace the progress of the campaign on Facebook.)

David Hancock of IHS Screen Digest suggests that 5% of US screens could disappear during the conversion. That number sounds small, but it amounts to nearly 2000 screens, and many are likely to be in art houses. The prospects remind me of 1928, when the studios agreed to shift to talking pictures. Put aside your pity for those actors like George Valentin in The Artist. Harder hit were the people who worked at the more than four thousand movie theatres too small, too remote, or too poor to be wired for sound. Of course that technological shift took place during the Great Depression. But our economy isn’t looking exactly vigorous, and in some ways today’s technological changeover is more hazardous. 1930s audiences didn’t have cable and Netflix to make staying home more attractive.

This is the fifth in a series on the transition to digital projection.

Thanks to Jack Foley of Focus Features distribution for sharing information with me. I also got useful information from Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics, Mike Maggiore and Bruce Goldstein of Film Forum, Jim Healy of our Cinematheque, Sanford Hess of the Art Theatre, and Merijoy Endrizzi-Ray of Sundance 608.

I’m very grateful to Jan Klingelhofer of Pacific Film Resources, Russ Collins of the Michigan Theater Foundation, and the membership of the Art House Project for welcoming me so generously to their annual Convergence. Special thanks as well to Juliet Goodfriend, Cordelia Stone, and Valerie Temple of the Bryn Mawr Film Institute for their survey of the art-house market, which I have drawn on here. That online survey, conducted in late 2011, collected data from 126 theatres in 29 states and Canada. I also benefited from conversations with Lisa Dombrowski, who’s writing a book on specialty cinema in the US, and Jenn Jennings, who is making a film, The Lost Picture Show, about digital conversion.

A good overview of the early development of digital art-house exhibition is offered by Michael Goldman’s 2008 article, “Digitally Independent Cinema,” in Filmmaker magazine. The Variety article I quoted from is “7 out of 10 Sureseaters Click” (27 July 1949), 13. For the history of art cinemas, see Michael F. Mayer, Foreign Films on American Screens (Arco, 1965); Barbara Wilinsky, Sure Seaters: The Emergence of Art House Cinema (University of Minnesota Press, 2001); and Kerry Segrave, Foreign Films in America: A History (McFarland, 2004). Tino Balio’s The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2010) traces the phenomenon from the standpoint of distribution. I discuss Tino’s book more here.

Box office figures for recent releases are taken from Box Office Mojo. My figures on theatres that closed during the conversion to sound come from The Film Daily Yearbook from the years 1931-1935. The process, which has many analogies with today’s digital conversion, is discussed in Donald Crafton, The Talkies: American Cinema’s Transition to Sound 1926-1931, vol. 4 in History of the American Cinema, ed. Charles Harpole (Scribners, 1997), Chapter 11, and Douglas Gomery, The Coming of Sound (Routledge, 2005), Chapter 8.

Seven Gables Cinema, Seattle, Washington. Photo by Joe Mabel. Reproduced under Gnu Free Documentation License.

PS 20 February: John Fithian, President of the National Association of Theatre Owners, confirms the prospect of theatre closures here: “For lower-grossing theaters, it’s just not affordable. I predict we’ll lose several thousand screens in the U.S.”

TINKER TAILOR: A guide for the perplexed

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.

DB here:

As the final credits rolled, a man behind me blurted out, “I don’t get it.” He’s not alone. Kristin and some acquaintances have told me that they found parts of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy hard to follow. Several critics, while praising the film (and doubtless getting more of it than that guy), have warned viewers to pay close attention. Roger Ebert said:

I enjoyed the film’s look and feel, the perfectly modulated performances, and the whole tawdry world of spy and counterspy, which must be among the world’s most dispiriting occupations. But I became increasingly aware that I didn’t always follow all the allusions and connections.

Some of the film’s admirers advise us not to worry much about the intricate storyline. Michael Phillips remarks:

This is one of the finest achievements of the year, and while it’s easy to lose your way in the labyrinth, I don’t think “Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy” is most interesting for its narrative pretzels. Rather, it’s about what this sort of life does to the average human soul.

Even if I weren’t a le Carré fan, I’d be fascinated by a film that can succeed both critically and financially and still leave its audience puzzled about its plot.

Critics of popular filmmaking claim that our movies cater to simple minds, but we actually find a lot of successful films, from Groundhog Day and Pulp Fiction to Inception, that are complex in intriguing ways. I argued in The Way Hollywood Tells It that since the 1960s one current of filmmaking has explored narrative strategies that were minor, even unheard-of, options in earlier times.

I’m not ready to join Steven Johnson in suggesting that audiences have become smarter. In certain respects older films are more demanding than contemporary ones. I’d rather say that new conventions are in force, aimed at certain sectors of the audience who are willing to put forth the effort. Ambitious filmmakers may find new ways to fulfill these conventions, balancing novelty with intelligibility. This is the path, I think, that the makers of Tinker Tailor took, and it didn’t prevent the film from earning $17 million at the US box office.

The film’s ’70s patina isn’t off-putting. The filmmakers offer deliberately grainy imagery, enveloped in hazes of rain and cigarette smoke. The palette, except for Ricki Tarr’s idyll with Irina, is grey, brown, and beige. Scenes are shot with long lenses, rack-focus, and drifting tracking shots. Zooms and push-ins are interrupted by cutaways. The result is an Altmanesque look, but more disciplined. It’s not the visual style, then, but those the narrative pretzels—another reminder of late ‘60s and early ‘70s storytelling—that attract my notice today.

So I persist: What makes the movie hard to grasp? If we can get a sense of this, we might get to know Tinker Tailor more intimately, while also producing some ideas about how mainstream films work generally. To attempt an answer, I have to go into detail. I won’t be supplying a plot synopsis, but the Wikipedia entry is reasonably comprehensive. I’ll be looking less at the story and more at the storytelling. Still, don’t read further if you haven’t seen the film. In the tradecraft jargon of blogging: There are spoilers ahead.

Breaking up the blocks

One factor contributing to the film’s difficulties, as many reviewers have pointed out, is that it’s adapted from a big and complex book. But it isn’t just the size of the original novel that poses problems. It’s the way the plot is constructed and the story is narrated.

The plot of the novel Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (published 1974; the commas aren’t in the adaptations) consists mostly of blocks of flashbacks. The action starts long after Control has died and his old staff, including George Smiley, has retired. The novel’s first scenes show Jim Prideaux’s arrival at the boy’s school, seen from the perspective of Bill Roach, his shy confidant. We don’t yet know how Jim connects to Smiley, who after a dinner with a gossipy acquaintance, is summoned to investigate the prospect of a mole in the Circus’s top echelon.

Smiley’s investigation involves questioning witnesses like Connie Sachs, but more often it involves “burrowing,” working patiently through the files that Control had studied. Le Carré presents what Smiley gleans from the files as flashbacks, and interwoven with those are Smiley’s reflections on the key personnel and their power struggles. Institutional memory and Smiley’s rueful recollections tie together the ambush of Jim Prideaux and the vein of top-secret information code-named Witchcraft.

Respecting the novel’s construction would demand a cascade of long tales framed by Smiley’s step-by-step pursuit. Arthur Hopcraft’s screenplay for the seven-installment 1979 BBC series took the simpler option of starting with a scene that is presented very late in the novel, during Jim’s revelatory confession to Smiley. The TV series opens with Control summoning Jim and sending him off to Czechoslovakia. Jim is shot and Control is cast out. Clarifying the string of events this way, and giving us a decent action scene early on, has its cost: Smiley doesn’t enter the series for twenty-three minutes.

Since Hopcraft and director John Irwin had hours at their disposal, the scenes could stretch and breathe, and they retain the somewhat chunky, modular quality of the novel. But a two-hour film couldn’t handle the book’s plot so spaciously. What did the team of Bridget O’Connor and Peter Straughan do? Straughan explains:

The adaptation process differs from book to book, but in the case of “Tinker Tailor,” it involved a kind of mosaic work. The structure of the novel was broken into pieces. Some long sequences would remain intact – Peter Guillam stealing the files from the Circus, for example – but in other cases we would take a line or event from one place in the narrative and move it elsewhere, shifting the fragments around endlessly until it felt right. The goal was to create a new version of the narrative which would bear a close family resemblance to the source material, but have its own cinematic personality. The really difficult part was not fitting the plot into two hours but doing it without losing the tone; to give the film the same autumnal, melancholy pace, and to give the script air and silence.

The most obvious instance of this fragmentation is the repetition of the ambush of Bill Prideaux in the Budapest café. In keeping with current norms of storytelling, this scene is replayed at crucial points, each time giving us a bit more information relevant to the scenes of testimony around it.

Repetition is a luxury that can’t be overindulged in adapting a hefty novel. To spare time for the pace, the air, and the silences the filmmakers want to include, they had to be more concise in their presentation of plot. They had to chop le Carré’s big narrative blocks into bits.

When we view a mosaic we can step back to see how the composition blends all the fragments. But we have to experience a movie bit by bit. A film, we might say, is a moving mosaic, and we are usually standing very close to it. Just as important, a mosaic, made out of gaps, leaves it to us to grasp how the parts fit together—to make our mind jump the gaps.

Unconventionally conventional

How does Tinker Tailor fit the pieces together? In general, the film adheres to common conventions of modern storytelling but then subtracts one or two layers of redundancy. The little gaps created make the film seem roundabout today, when rather linear and explicit narration is the norm.

Start with a simple case. Like many modern spy films, Tinker Tailor initiates a shift to another locale by a long-shot framing, often from on high. Here’s an example from The Bourne Ultimatum.

It’s triply redundant: We see a city landscape including the Arc de Triomphe; we’re told it’s Paris; and we’re told it’s Paris, France (not Paris, Maine). Compare the parallel shot from Tinker Tailor.

Not exactly a difficult leap—who doesn’t know that the Eiffel Tower is in Paris (France)?—but it’s a little less explicit. Earlier instances are more laconic. When we’re taken to Budapest and Istanbul, probably not as immediately recognizable to many in the audience as Paris, we get a cityscape with only one mention in the dialogue to tag the setting, and no captions. Least explicit of all are the shots picking out the Circus in London.

Another film would have typed out, “MI6 HQ,” but we’re left to infer that behind this façade the Secret Intelligence Service does its work. So the convention of the exterior establishing shot is respected but made a little less redundant.

Consider as well the introduction of the Circus’s decision makers. Another film might have started with Smiley and followed him from his office into the briefing room. Instead, he’s introduced as one of several men, then as an out-of-focus figure alongside Control. And even Control could have been more clearly identified. He signs his resignation with what could become an emblem of the film’s stingy approach to storytelling.

Just as truculent is the process by which Lacon is led to summon Smiley. First Lacon gets a warning call from the field agent Ricki Tarr. So far, so conventional. But Tomas Alfredson has staged things so that Tarr is seen at a distance, turned from us, and blocked by a phone booth. Who is this guy? We must get all our information solely from his voice, not his facial expression.

Soon after Peter Guillam has entered the Circus, he gets a call. Most directors would have cut away to the caller, or at least let us hear what Peter is hearing. But we’re denied that information. On the soundtrack, we hear only a muffled, “It’s Oliver…ringing…” It’s Lacon, but you know that only if you know his first name is Oliver, and we’re teased by hearing almost nothing of what he’s saying. We know even less than Guillam, and this suppressive narration is characteristic of Alfredson’s handling of genre conventions.

Next we see Smiley at home, watching television. There’s a knock at the door. Cut to a car driving, Peter at the wheel and Smiley in the back seat. Smiley is silent, and Peter offers his regrets: “I was sorry to hear about Control, Mr. Smiley.” Earlier we’ve been given one shot of the dead Control in the hospital. So much for his backstory.

Finally, as the car pulls up at Lacon’s house, the fragments combine into an intelligible sequence when Peter says, “He said Tarr called him from a phone box.” Retrospectively, we can buckle the sequence up as a familiar genre action: The hero is called back to the battle by his chief.

Another convention, one that goes far back, is the dialogue hook. This is a bit of speech that ends one scene and links directly to the next one. Tarr calls Lacon and names Guillam as his supervisor. Cut to Guillam crossing the street and entering the Circus. Later, Smiley suggests that he and Guillam investigate Control’s flat. Cut to them entering it.

Dialogue hooks, as I’ve traced out here, are enormously helpful in guiding us through the plot. But sometimes Tinker Tailor works more obliquely. In one scene Peter reads of the staff who were sacked following Control’s fall. One is Jerry Westerby, whom we’ll meet a long while later, and the other is Connie Sachs. Cut to a train station, with Smiley buying a ticket to Oxford. It’s a hidden hook: most films would include in the earlier scene a line such as, “Connie Sachs, who’s now in Oxford.” Again, a conventional device is roughened a bit, made slightly more difficult. And sometimes the hook is visual and disruptive, as when a shot of Jim, bleeding in the Budapest arcade, is followed by a shot of the boy Bill Roach looking out a window at Jim’s arrival, as if he’s also looking down at his future teacher.

The BBC series was broadcast in weekly episodes, so recapping and backtracking in each installment helped viewers remember. At intervals we see Smiley bringing Peter up to date and briefing Lacon on current discoveries. The film flagrantly refuses to provide this conventional help. As Ebert notes:

More ordinary spy movies provide helpful scenes in which characters brief each other as a device to keep the audience oriented. I have every confidence that in this film, every piece of information is there and flawlessly meshes, but I can’t say so for sure. . . .

What replaces the standard briefing scenes? Some rather elliptical passages. There are the nodes in which Smiley reflects on the evidence. We get a shot of him staring, followed by a cascade of imagery as his mind plays with possible suspects.

Linked to the briefing scene is another convention, the board or wall on which all the suspects are diagrammatically arranged. In our visit to Control’s apartment we might have seen pictures of Bill Haydon, Roy Bland, Toby Esterhase, and Percy Alleline laid out in a rectangle, with the sinister silhouette of Karla up top, and dotted lines connecting them. Yet Control, the bedraggled chainsmoker, could hardly be so tidy. Instead, the film gives us something more in character and more oblique: a litter of chessmen, each with a picture taped awkwardly on. Eventually Karla is revealed as another piece (the powerful white Queen). On his own, Smiley joins in Control’s conceit and tapes a picture of the new suspect Polyakov to a bishop.

Le Carré’s novel tied the suspects together with a verbal emblem, based on the child’s nursery rhyme. It linked the boy’s school to the Circus. But the film doesn’t introduce the tinker-tailor motif until very late. Instead the chess pieces visualize the multiple-choice problem, but in a ragged, haphazard way that suggests that perhaps Control really was, as Jim Prideaux suspects, going mad. More broadly, the imagery (with the briefing room as a gridded checkerboard) reminds us that spying, known for decades as The Great Game, is now a global chess match. It pits Karla against Smiley—whom Control has identified as the black Queen.

George the Obscure

Again and again, the script and Alfredson’s direction invoke a convention only to make it more difficult to grasp. The central examples involve Ann, the faithless wife. She isn’t just treated elliptically; she’s suppressed. Instead of showing her flirting with Bill at the Christmas party, we see only the back of her head and Bill looking past Smiley’s shoulder.

In a later flashback to the party, Smiley looks out the window and sees Ann in the garden. Another film would have shown us who’s clutching her in the foliage, but this film leaves it to us.

Of course many viewers will know Ann’s partner is Bill, but another film would have confirmed this more explicitly. Instead another standard scene is handled in a glancing way. More generally, Ann’s phantom presence not only makes her seem remote, like a princess in a tower, but sets her off against the blonde Irina, the maiden to be rescued in Ricki Tarr’s story. Thanks to the camera and a compact mirror, Irina’s face gets the caresses another film would devote to Ann.

Irina, beautiful and sincere, holds the film’s major secret, the one that initiates Smiley’s investigation. She harks back to the blonde mother who is in the line of fire in the Budapest arcade, and that shooting prefigures Irina’s fate.

The crowning achievement in the film’s laconic way with conventions is the climax in the safe house. Smiley has arranged for Ricki to send a message that will force Karla’s mole to make an emergency appointment with his connection Polyakov. There Smiley, Guillam, and Mandel will record the meeting and capture the double agent. In the BBC series, this climax runs over eight minutes, built out of crosscutting and suspenseful waiting. Smiley and Guillam burst in together and a quick pan shot reveals Bill as the culprit.

The film uses suspense and crosscutting as well, but the sequence consumes only six minutes. More important, by switching our attachment away from Smiley at the crucial moment, it conceals his entry to Bill and Polyakov. Instead we follow Guillam separately into the house, up the stairs, and to the parlor. There he confronts the aftermath of what might have been a heroic confrontation. Climax is treated as anticlimax.

Jim Emerson, in a nicely honed piece, suggests that we think of such passages as not so much elliptical as economical. I want to have it both ways. The scenes are economical because they fulfill familiar narrative and genre-based functions: We know how to fill them in. Yet they’re also elliptical because they hold back information, sometimes a little and sometimes a lot. A mosaic can show us familiar people and things, but it also asks us to make extra effort to see the pattern emerge. The tesserae fit, but the bumps and grooves between them are palpable.

It may be that art films have always tended to be self-consciously wrought genre films. L’Avventura: A mystery-melodrama. Blow-Up: A detective story. Drive: the thinking person’s action film. If so, then Tinker Tailor is the smart Bourne movie. Creative novelty needs a familiar base to play off. Movies come from other movies, and originality can take a tradition, even a popular one, as a point of departure for innovation.

Best watcher in the unit

Once plot gaps have alerted us, we should expect things to proceed through hints. Granted, there are hints that can’t be picked up unless you know the novel. For instance, the film doesn’t stress the fact, emphasized in the novel, that Bill is an amateur painter and the canvas he brings Ann on the fateful night is one of his own works. It’s the picture that Smiley is studying at the end of the credits sequence, as if the film’s two primary antagonists are already squaring off.

But, sticking just to the hints we can pick up without the novel, the film is fairly rich. It invites multiple viewings, as many movies do nowadays, in order to catch the undercurrents or the things that flash by too quickly on the first pass. (If we want to find more, we can buy the DVD.) I can’t pretend to exhaust the possibilities, but here are some that strike me.

Go back to those chessmen. As we’ve seen, the two antagonists, Karla and Smiley, are made parallel as the rival Queens. Three suspects are assigned to innocuous pieces: Percy as the white Rook, Toby as the black Knight, and Roy as the black King (although that assignment might be a narrative feint, hinting that Roy’s the traitor). But Bill is the white Bishop, and in retrospect we can see the fact that Smiley makes the Moscow agent Polyakov a black Bishop is a pointer to Bill’s guilt—and maybe a suggestion that, as Bill will say, George knew all along.

Or take the homosexual element. One question that comes up in conversation after the movie is whether Bill and Jim were lovers. It’s treated as a possibility in the original novel and becomes stronger as the film proceeds, especially after Bill—in a moment of privileged information for the audience—pockets a picture of the two friends embracing and laughing. By the end, in the final flashback of the Christmas party, Bill rouses the loner Jim and flashes him a smile; but the brandy glass he floats away with seems intended for Ann. Bill’s bisexuality is explicit in the epilogue when, in the compound, he asks Smiley to pay off both a girl and a boy. More than a hint, as well, is the tear that dribbles down Jim’s cheek as he executes his friend. (Bill’s wound, rhyming with Jim’s perforated back in Budapest, again recalls the slain mother in the arcade.)

Similarly ambivalent is the presentation of the dapper Peter Guillam. He’s introduced turning his head to watch a cute young lady pass. Later he’s revealed to be gay: for security reasons, he has to break up with his partner. In retrospect, we can see the shot when Bill and Peter eye the new clerk Belinda as presenting two double agents, each one passing as a lady-killer.

More minor touches hint at the sexual undercurrent. Bill on the phone: “And I said you may fuck me but you still have to call me sir in the morning.” It takes a quick eye to spot another manifestation of the motif. Polyakov, posing as a cultural attaché, writes articles for a bilingual magazine. After Connie has told her tale, there’s an insert—an excerpt from Connie’s memorabilia, or perhaps only a memory of Smiley’s—of an article signed by Polyakov, which says of the Russian Ballet corps:

To see them only in a narrative ballet would be to know them incompletely. The programme shows a perfect cross section of their accomplishments.

They can dazzle us with a technique that seems to defy the laws of gravity but that is not merely acrobatic because it is truly gay in expression.

Like the dancers, Bill and Jim are both athletes and acrobats, powerful and graceful. I can’t prove this implication was intended by filmmakers, but by chance or design, it’s a fragment that fits.

Or take the Christmas party. There the tune, “The Second-Best Secret Agent in the World” ramifies outward to several second-besters: that night Jim is Bill’s second-best lover, Smiley is Ann’s second-best lover, and Smiley is the agent outwitted, at that point, by Bill. Another hint: At the height of the evening, the USSR anthem is sung ironically by the Circus staff, while Bill, an undercover Soviet, is off in the garden. Not to mention that as Control signs his retirement papers, he asserts: “A man should know when to leave the party.”

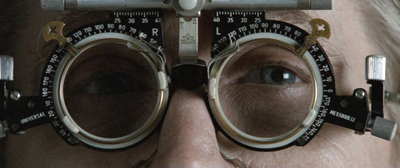

Above all are the eyeglasses. Promoted in the film’s publicity (when Oldman found them, he found the character), they become associated with seeing things as they are. The old hornrims seem to be something of a shield; Smiley pushes them back into place after he sees Bill with Ann. But once Smiley has gotten his new, more powerful pair after leaving the Circus, he uses them as an instrument of scrutiny. They enlarge his vision eerily; often they’re lit and in focus when his eyes aren’t. And they hide his eyes from others.

Although he bears Bill’s name, the podgy boy Roach is a closer parallel to Smiley. For him and for George, spectacles are a sign of wary vigilance. Jim praises Roach: “Best watcher in the unit, I’ll bet. As long’s he’s got his specs on, aye?” The motif may come from a passage in the novel that is recast for the film. Bill tells Smiley that Karla had worried that Smiley would catch him.

Karla said you were good—the one we had to worry about. But you do have a blind spot. And if I was known to be Ann’s lover, you wouldn’t be able to see me straight. And he was right—up to a point.

But those were the old glasses, and Smiley was a more vulnerable man then.

Saint George?

The novel is based, as most people know, on the revelation back in 1963 that a cadre at the center of the British Secret Intelligence Service was in the pay of Moscow. Kim Philby was the central figure, surrounded by Donald Maclean, Guy Burgess, and “the fourth man” identified later as art historian Anthony Blunt. In a scathing introduction to a 1981 book on the conspiracy, le Carré diagnoses the scandal as symptomatic of an endemic weakness in Britain’s ruling class. (Yes, he uses that phrase, which no American politician dares to utter.)

Was he not born and trained into the Establishment? Effortlessly he copied its attitudes, caught its diffident stammer, its hesitant arrogance; effortlessly he took his place in its nameless hegemony. . . . The SIS quite clearly identified class with loyalty.

He might be describing Bill Haydon:

Philby, an aggressive, upper-class enemy, was of our blood and hunted with our pack; to the very end he expected and received the indulgence owing to his moderation, good breeding, and boyish, flirtatious charm.

Worse, the agency that was pledged to protect Britain had insulated itself from reality, somehow seeing in an American-promoted anti-Communism a small rebirth of the Raj.

Whatever went on the big world outside, England’s flower would be cherished. “The Empire may be crumbling; but within our secret elite, the clean-limbed tradition of English power would survive.”

Le Carré’s lacerating remarks remind us that he might be our only major popular novelist who has held uncompromisingly critical positions on international affairs, including the Iraq war and the growth of American militarism and corporate power.

But the polemicist isn’t identical with the novelist. Tinker, Tailor provides a far more ambivalent picture of betrayal. Le Carré the polemicist has created in Haydon a perfect embodiment of what he despised about British Intelligence and the class system that feeds it. The parallel world of the boys’ school evokes the origins of the corrosive ethic that led to Bill’s treachery.

Yet the novelist spares his traitor the worst. For one thing, Peter Guillam, who idolized Haydon, can’t summon up condemnation.

Despite his banked-up anger at the moment of breaking into the room, it required an act of will on his own part—and quite a violent one, at that—to regard Bill Haydon with much other than affection. Perhaps, as Bill would say, he had finally grown up.

Smiley, who has every reason to hate Bill, is at a loss. He mulls over how he should judge the man who has done such monstrous things. As a friend worthy of respect who stood by his convictions? As a committed thirties intellectual? As a romantic elitist clouded by ideology? As an esthete who elevated his distaste for Philistinism to a political principle? As a superficial man in the grip of a compulsion to betray?

Smiley shrugged it all aside, distrustful as ever of the standard shapes of human motive. He settled instead for a picture of one of those wooden Russian dolls that open up, revealing one person inside the other, and another inside him. Of all men living, only Karla had seen the last little doll inside Bill Haydon.

In the book, Smiley’s uncertainty about Bill leads him to hope for a reconciliation with Ann. For him, unlike Bill and Karla, love isn’t an illusion or cover story. In the TV series, for all his triumph over the Alleline cadre and Karla’s mole, he returns to Ann and her chiding: “Poor George, life’s such a puzzle to you, isn’t it?” But the film gives us a different Smiley, and it interprets his reward quite differently.

We can approach the problem through performance. The TV series makes Smiley a stern schoolmaster, keeping his own counsel but voluble, thanks to the fluting of that Guinness voice. His facial expressions work a narrow range, but are very nuanced within that compass. Here is Guinness shifting, minutely, from polite approval to a steely comprehension while his oblivious informant chatters on.

By contrast, as every critic has noted, Oldman’s Smiley is virtually blank for most of the film. His frog-mouth, half-open or clamped shut, remains impassive. Guinness lets us into Smiley’s mind as he interrogates his targets, but Oldman’s most marked reactions are brow-wrinkling concentration and puzzlement. The high point, George’s discovery of Ann’s disloyalty, elicits only a gasp and a gape (and a pushing up of the glasses). As usual, even that reaction is muffled a bit, this time by the profile angle.

Similarly, everything conspires to make George obscure. Framing, setting, and lighting put him far from us, wrap him in shadows, let reflections on his spectacles block his eyes.

Guinness’s Smiley isn’t hard to read, once you tune to his high, narrow frequency, but Oldman’s Smiley is a sphinx. And it seems to me that this poker face works toward a new conception of Smiley’s role. The elliptical narration conspires with Oldman’s performance to create a conclusion that is far more harsh than what we find in the book or the series.

Early on, the film shows us George shamed. Control, forced to resign, announces that Smiley will leave with him. It evidently comes as a surprise to Smiley, who—in a moment that many critics have rightly praised—turns his head slightly and after a beat and a blink accepts with a tiny nod. For the rest of the film, George’s head-turns will be his principal signal of surprise, uncertainty, or sudden realization. (It’s even contagious: his adversaries execute the same gesture, and even Guillam catches the habit.) Smiley and Control stalk out of the Circus as exiles and part on the sidewalk without a word and Smiley comes home to an empty house.

Summoned back into service, he launches his investigation. In a key scene in the novel, the series, and the film, he confides to Peter his meeting with Karla long ago, when he tried to persuade the Russian to switch sides. The meeting disclosed a faultline in Karla’s character (“He’s a fanatic, and the fanatic is always concealing a secret doubt”), but it revealed Smiley’s weak spot too. Asking Karla to think of his wife, Smiley betrayed his worries about Ann. Karla retained the cigarette lighter that Ann had given Smiley, a token of Smiley’s fear of losing her. Years later, cuckolded by Bill at Karla’s behest, Smiley adds sexual shame to professional disgrace.

There’s a certain mystery about how the movie Smiley cracks the case. In the book and the series, there’s a lot more evidence about the mole than we get in the film. In the turning-point sequence, subjective montages lead to a burst of images and recurrent lines from Ricki: “Everything the Circus thinks is gold is shit.” Smiley is convinced there really is a mole, chiefly because of Jim Prideaux’s testimony, but we have to reason on trust: the reappearance of Karla and the murder of Irina before Jim’s eyes connect the mission to Budapest with the Witchcraft files.

The TV Smiley reveals his reasoning in a very lengthy interrogation of Toby Esterhase. Over fifteen minutes, Smiley builds a plausible case and forces Toby, to avoid suspicion that he’s the mole, to reveal the location of the safe house. Lacon is briefed offscreen, and George is given permission to set the trap.

But the film Smiley acts very differently. He confronts Lacon and the Minister and bluntly announces that there’s a mole, that Karla controls him, and that SIS has been feeding the Americans trivia and lies. He offers no evidence. The officials are shaken solely by Smiley’s uncharacteristic vehemence. His mocking conviction smashes their resistance and they give him permission to go after Toby.

With Toby, Smiley again uses brute force. No reasoning, no evidence, just the bald threat of throwing Toby onto the plane and shipping him back over the Curtain. Cringing and whining, Toby gives up the safe house’s address, and George can proceed to set the trap. And this comes after the moment when Smiley, knowing full well that Irina is dead, promises Ricki to do “his utmost” to retrieve her. Guinness’s Smiley makes the same promise, but in his gentleness we sense a man pained by his bad faith. Oldman’s Smiley is as guarded as ever.

I submit that the Smiley of the film, once he has overpowered his superiors, can’t spare a moment to brood over Haydon’s personality. He proceeds largely from a vindictive, controlled aggression. Lacon fired him, Alleline despised him, Toby insulted him, and Bill betrayed his marriage. Behind that severe blankness, I think, burns a desire to avenge Control, and to get a bit of his own back. When that mask slips, in talking with Lacon and the Minister, he’s nearly gloating.

The film, in sum, seems to me to offer a legitimate reinterpretation of the Smiley character. His fierce anger is rather close to le Carré’s attitude toward Kim Philby: The man may have been an enigma, but he was still despicable. The difference is that while le Carré can castigate the man in print, George can pay his traitor back. In this dirty game, he can finally checkmate Karla.

Was it worth it? The novel leaves you wondering. In its final pages, Smiley moves toward uncertain reconciliation with Ann. Jim’s future is more hopeful: after killing Haydon, he returns to the school and rebuilds his relation with young Bill, the other “new boy.” The only hope, it seems, lies in human relationships, not in a frigid bureaucracy.

But in the film, Jim harshly breaks off with the boy, and Smiley triumphs. To the music of “Beyond the Sea,” the losers—Ricki, Connie, Bill—are glimpsed. But Smiley, having kept his own counsel throughout, is a winner. There’s little sense here of le Carré’s distaste for the institution that nourished Bill and his breed. Smiley reenters the Circus, in a smart new suit and topcoat, striding to the top floor and taking Control’s seat, to offscreen applause. (I grant you there’s a bit of irony in that sound effect.) And how else to explain the vignette before that when, after the death of Bill Haydon, Smiley comes home to find Ann there? The sailor of the song has returned to the woman who has been waiting for him. Beggarman has gotten what Ricki saw in Irina: Treasure.

In preparing this entry, I was much helped by James Schamus and Khaliah Neal of Focus Films. Thanks also to Jeff Smith and Kristin for conversations about the movie.

For more on the film’s artistic approach, see Jean Oppenheimer, “A Mole in the Ministry,” American Cinematographer 92, 12 (December 2011), 28-34 (apparently not available online). After explaining that DP Hoyte van Hoytema and Alfredson sought “a grainy, somewhat colorless look,” the article reports van Hoytema saying that the zoom shots were modeled on 1970s ones: “When I look at films from the ‘70s, I like the fact that the zooms are so functional and solid. They have a beginning and an end.”

Le Carré’s introduction may be found in Bruce Page, David Leitch, and Phillip Knightley’s The Philby Conspiracy (Ballantine, 1981). Valuable studies of le Carré’s work include Peter Lewis, John le Carré (Ungar, 1985) and Michael Denning, Cover Stories: Narrative and Ideology in the British Spy Thriller (Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1987). In an earlier entry I offer an appreciation of the second book in the Karla trilogy, The Honourable Schoolboy.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy: John le Carré in right foreground.

PS 1 March: In a followup entry, I explore other aspects of Tinker Tailor.

Reasons for cinephile optimism

Hollywood may have largely let us down this year, but after the first few days at the Vancouver International Film Festival, we’ve seen several excellent films and a lot of originality. Here are two of the highlights so far.

Kristin here:

Every year, when festival posts its list of films, I look through it for titles I’d heard about from other festivals or seen enthusiastically reviewed or had recommended to me. One title I was delighted to see on this year’s program was Lech Majewski’s The Mill & the Cross. It’s not nearly as famous as some of the other films showing here, like The Skin I Live In or Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, but I keenly anticipated seeing it.

I learned about The Mill & the Cross through an article in American Cinematographer (posted on the film’s rich website). Majewski collaborated with art historian Michael Francis Gibson to explore Pieter Bruegel’s 1564 masterpiece, “The Way to Calvary.” In the painting, the figure of Christ carrying his cross to calvary is set in the midst of a vast landscape full of fields, cliffs, a distant town, trees, and hundreds of people, all surmounted by a windmill atop one of the rocky formations and silhouetted against a windy, cloudy sky. Majewski sought, as he said, “to enter Bruegel’s world”—to enter into the painting itself and bring it to life.

His goal reminded me of Godard’s 1982 film, Passion, where one of the main characters films actors in a studio. He appears to be trying to replicate classic paintings, with models posed in costumes and miniatures representing a cityscape. I’ve never been able to picture what the result might have looked like. I’m not sure I would have enjoyed watching it, which may be part of Godard’s point. But Majewski had the tremendous advantage of modern computer technology to create an almost seamless blend between digital elements derived from the original painting and those derived from live-action filmmaking on location and in front of blue screens. For those who complain about “effects-heavy” blockbusters, The Mill & and Cross is a powerful counter-example, a film utterly dependent on CGI yet meditative and even profound. It certainly succeeds in Majewski’s goal, creating an uncanny sense of being inside the painting (see above.)

For the film seeks to explore the qualities that Bruegel himself did, to push the crucifixion to a minor place in the composition of the whole and to explore the sacred in the everyday. The film’s story is dense. On one level, we watch Bruegel sketching his models as he explains the concept of the painting to his patron. But we also see him departing home in the morning, and we follow the everyday doings of his family. We see several other minor characters who will figure in the painting waking up and beginning to work, including the miller in his mill atop the cliff. The filmmaking team found a surviving mill of the period, and for an astonishing scene early on, the ancient works in the vast interior were set in motion for the first time in centuries.

We see details of the characters’ lives, such as a man hitching up a horse to a wagon, an innocent-appearing detail until we realize much later in the film that this cart will deliver the wood for making the crosses and will carry the two thieves condemned to die alongside Jesus to Golgotha. Finally, we are invited to contemplate the contradiction, so familiar from thousands of paintings, that an event from antiquity is seen taking place in a contemporary landscape. The result is a comment on the Spanish occupation of Flanders as well as on the Biblical story.

In an all-too-brief scene, Bruegel explains the composition of the painting to his patron, showing how the small group around Jesus forms the center, with the lines between the other main elements around the periphery intersect with it. The implicit comparison is to a charming moment in the film when the painter admires an intricate spiderweb. Apart from all the thematic material, we do learn something about Bruegel’s painting–a point that is emphasized at the end of the film, which tracks back from the actual painting in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, as if inviting us to go and contemplate it in the light of what we have just seen.

Part of what makes The Mill & the Cross so exciting is that it achieves that rarest of things, making us feel that we are seeing something very worthwhile that has never been done before.

The film has a very limited release in the U.S. Anyone who has a chance to see it on the big screen should snatch it. The images, shot on the Red One camera and projected (here, at least) on 35mm, are spectacular.

Once upon a time, and time again

DB here:

Cesare Zavattini, central screenwriter of Italian Neorealism, liked to tell this story. A Hollywood producer once told him:

“This is how we would imagine a scene with an aeroplane. The plane passes by. . . a machine gun fires . . . the plane crashes. And this is how you would imagine it. The plane passes by. . . The plane passes by again… The plane passes by once more…”

He was right. But we have still not gone far enough. It is not enough to make the aeroplane pass by three times; we must make it pass by twenty times.

And, Zavattini seems to suggest, the machine gun should never fire.

Neorealism was one of the most important influences on what we’ve come to call the postwar European “art cinema,” and particularly on filmmakers’ treatment of time. I thought of the Zavattini passage while watching the opening scenes of Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, a film which proves that you can always ring fresh changes on a well-established tradition.