Archive for October 2007

Rowling’s revelations: Who wants to know

Dumbledore, by Lisa, from

http://www.poudlard.org/fanarts/displayimage.php?album=toprated&cat=6&pos=0

Kristin here–

By now anyone who has not lived in thorough isolation from the media knows that on October 19, during a signing of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows at Carnegie Hall, J. K. Rowling revealed that Prof. Albus Percival Wulfric Brian Dumbledore is gay.

At least in her opinion, some might add.

Rowling’s public revelation that she has long considered Dumbledore to be gay came during a question and answer session in which a fan asked, “Did Dumbledore, who believed in the prevailing power of love, ever fall in love himself?” Rowling replied, “My truthful answer to you … I always thought of Dumbledore as gay.” According to mainstream media reports, after a stunned silence the audience burst into a lengthy ovation.

Rowling has made a few additional comments on this subject since then. On October 22 during a press conference in Toronto, she was questioned about how far back her outlook on Dumbledore’s sexual orientation went. She dated it back to the planning stages, “probably before the first book was published” (Harry Potter and the Philospher’s Stone, 1997). She pointed out, “I was writing for seven years before the first book came out.” (The press conference has been posted in two parts on YouTube, here and here. Some stories from reporters covering the event have slightly misquoted Rowling’s statements. My quotations are transcribed from the video.)

Naturally questions about the Dumbledore outing came at regular intervals during the Toronto press session. Initially Rowling commented, “It has certainly never been news to me that a brave and brilliant man could love other men.” Asked about the political ramifications of the outing, Rowling said that she could not comment on that so soon after the fact. “I can’t really answer that. It is what it is. He’s my character, and as my character, I have the right to know what I know about him and say what I say about him.”

But do we want to listen?

Of course, she has the right. The questions that have been raised by many are, should she? If she does, should we accept her statements as true within the universe of the published books?

Whether she should provide additional background for the series is basically a matter of opinion. Some people, many of them children, want more information and think she should.

Salon.com’s Rebecca Traister has posted a thoughtful essay taking the “she shouldn’t” position. She points out one thing that most fevered accounts of the Dumbledore outing have neglected: “Dumbledore’s gayness is one of the pieces of bonus information about her characters that she’s been dispensing steadily since the publication of her magical swan song, ‘Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.’”

Certainly at the Carnegie Hall appearance, the Dumbledore question came amidst several that Rowling was asked about the fates or motives of other characters. (The most extensive transcript of that Q&A session is on The Leaky Cauldron.) Nearly all mainstream media reports ignored these in favor of blowing up the gay issue, but just as much information about other characters was revealed, and Rowling has answered similar queries in other Q&A situations.

Traister admits that the fans are the ones asking for such information. “Her abundant generosity with information is surely a response to a vast, insatiable fan base that does not have a high tolerance for never-ending suspense, ambiguity or nuance. As she told the ‘Today’ show’s Meredith Vieira back in July, ‘I’m dealing with a level of obsession in some of my fans that will not rest until they know the middle names of Harry’s great grand-parents.’”

Traister adds, “Rowling naturally wants to provide answers for these heartbroken obsessives who perhaps are too young to know the satisfying pleasures of perpetual yearning and feel that they must must must know how much money Harry makes and whether Luna has kids.” I don’t know about heartbroken, but they certainly are curious.

Traister goes on to argue that Rowling should stop giving out information and ruining readers’ own imaginings about what the author left out. She cites an example of Rowling revealing to a fan what Harry’s Aunt Petunia nearly said to him upon their last parting. According to Rowling, it was “I do know what you’re up against, and I hope it’s OK.” Traister is disappointed: “Oh. That’s too bad. Because in my imagination, Petunia was going to say something much more exciting than that.”

Perhaps in many cases, especially about specific details like this, knowing is less fun than imagining. Still, I’m sure some of Rowling’s revelations are more exciting, or at least more interesting, than what we imagine.

Let’s take one small example, Rowling’s explanation for the name “Dumbledore.” Few readers will imagine anything about it or realize that the word actually means something. I have wondered whether Rowling just liked the sound of the word (which appears in Hardy and Tolkien) or she saw some connection between the headmaster and a bumblebee. She revealed the answer in a radio interview in 1999: “Dumbledore is an old English word meaning bumblebee. Because Albus Dumbledore is very fond of music, I always imagined him as sort of humming to himself a lot.”

That’s charming. I didn’t imagine Dumbledore humming as I read the book. Indeed, I don’t recall any scenes where he is alone (presumably when he hums), given how much of the narration is restricted to Harry’s point-of-view. But I am glad to know this, even if it had to come from the author herself. (In the same interview, by the way, she said, “I kind of see Dumbledore more as a John Gielgud type, you know, quite elderly and – and quite stately.” Perhaps a hint of where the gayness crept in.)

If Rowling were to heed Traister’s plea that she stop dispensing extra-textual information, that would mean we adults, who presumably “know the satisfying pleasures of perpetual yearning,” would get our way and the children wouldn’t. (Of course, not nearly all adults would refrain from asking for more information from Rowling.) I think that’s rather unfair, since these are at bottom children’s books. It was initially surprising how many adults ended up reading them, and there are HP fans of all ages. Still, shouldn’t the target audience take priority?

The video of the Meredith Vieira interview and the transcript of the Carnegie Hall event confirm that many of the questions were requests for more information about the characters. Would we really want the author to refuse each of these? How boring and frustrating for those children if every other answer is, “I really shouldn’t tell you. Just use your imaginations”! They want those “pieces of bonus information about her characters that she’s been dispensing steadily.” As far as I can tell, most or all of the bits of information Rowling has given out have come in response to specific questions from fans. She hasn’t been volunteering them right and left. And apart from the Dumbledore comments, the information she gives out has hardly been flooding the media to such an extent that we can’t avoid it if we wish. Given that Rowling has been answering such questions for months, why did commentators wait until this particular revelation to complain?

Who’s J. K. Rowling to tell us Dumbledore is gay?

Quite apart from there being some people who want this information and others who don’t, there is a more theoretical question. As Jason Mittell puts it in a brief essay on his website, “What does it mean for an author to proclaim such information about a character in an already completed fictional world?”

Mittell would accept that Rowling’s statements about that world would become part of the HP canon as long as the series was still in progress. “But something changes once a series is complete.” He points out that Rowling seems to have known all along that Dumbledore is gay, and yet she never made that explicit. “Does she retain her power to control her fictional world after the books have been closed?”

Does it have to be explicit, or will implicit do? Some, including Rowling, would say that there is a portrayal of Dumbledore’s relationship with Grindelwald that hints at his being gay. At the Toronto press conference, Rowling stated, “It’s in the book. It’s very clear in the book. Absolutely. I think a child will see a friendship, and I think a sensitive adult may well understand that it was an infatuation. I knew it was an infatuation.” I must admit that I didn’t pick up on the clues. Not that I’m insensitive, I hope, but because it would not have occurred to me that a popular mainstream writer would include a prominent gay character. (Associated Press writer Hillel Italie has pointed out a few passages that some may have taken as indications.)

[Added Oct. 29: The November 2 print issue of Entertainment Weekly has the results of an online poll, “Did you suspect Dumbledore was gay? (p. 11). 22% said they did. That’s probably self-selecting, as those who did might be more likely to vote. Still, at least some people did figure it out.]

Putting aside that example, though, much of the other information Rowling has been giving out does concern events that occur after the books’ action or are never referred to in the texts, so Mittell’s question remains.

Mittell contrasts this situation with that of Star Trek, where it has been the fans who “claim their interpretive rights to open up ambiguities and subtext freely,” primarily by writing fanfiction. The situation is different, though, I think, because most fans would not claim that their fics enter into and become part of the canon, even though they may meticulously obey its premises. Rowling seems to be claiming the right to expand the HP canon by her statements as well as by her writing.

(By the way, Rowling also mentioned fanfiction during her answers about Dumbledore at Carnegie Hall. I’ve written on her remarks and that subject on the Frodo Franchise blog.)

One can accept Rowling’s pronouncements about the book series or not. But do those pronouncements carry any greater weight than comments made about the HP world by others?

I am aware that in the 20th Century, the “death of the author” was proclaimed. When I was in graduate school, “intentions” was still sort of a dirty word in analysis. If the work cannot stand entirely by itself, then it has to some degree failed, was the widespread view.

There’s some truth to that, and yet there clearly is a very widespread impulse on the parts of readers and viewers to ask living creators for more. Film scholars read interviews with directors and other filmmakers. Some filmmakers have written about their individual works or their craft in general. David has commented here recently, “Do filmmakers deserve the last word?” As he shows, they can dispense misleading information about their own films. Yet not letting them have the last word doesn’t mean we must ignore all their other words. They often have very interesting things to say.

There are points that could be made in favor of a voluble Rowling.

One could argue that the books are not necessarily closed. Rowling could always write more in this universe. Indeed, she has said she probably will write an encyclopedia on the HP world–though she has cautioned this may not be her next project. A summary of Rowling’s July 24 appearance on the Today Show describes the project, partly in Rowling’s words: “’I suppose I have [started] because the raw material is all in my notes.’ The encyclopedia would include back stories of characters she has already written but had to cut for the sake of the narrative arc (‘I’ve said before that Dean Thomas had a much more interesting history than ever appeared in the books’), as well as details about the characters who survive ‘Deathly Hallows,’ characters who continue to live on in Rowling’s mind in a clearly defined magical world.” Presumably much of the information she has given in answer to questions comes from this mass of material, so it may someday exist in print with her as the author.

In the Toronto press conference Rowling gave further information about possible writing projects within the franchise. She said she would probably not write a prequel for the HP series, though she would not rule it out entirely. Asked about the rumored encyclopedia, she replied that it “would be the way of putting in all the information, the extra information on all these characters.” She adds that the proceeds would go to charity and that “It’s certainly not something I plan on being my next project. I’d like to take a little time from Harry’s world before I go into that.”

Tolkien did something comparable. For nearly two decades after the publication of The Lord of the Rings, he wrote drafts of essays on various characters and events. He seems to have initially intended these as an entire volume of appendices, though later he continued because he just could not seem to stop examining his invented world. The resulting posthumous publications of these texts as edited by his son are not exactly canon—not least because they are unfinished and sometimes contradict each other. But they certainly are treated by scholars and fans as illuminating parts of Tolkien’s created world that are not in the novel. Semi-canon, if you will. Perhaps if Rowling does write down all the nuggets of information that she has been tossing out, publication will anoint them with canonical status at last.

One could also argue that HP is not just a book series but an ongoing franchise or saga. The book series may be finished, but the HP universe is larger than it. Rowling’s outing of Dumbledore and other remarks come when there are two films yet to appear. One of these has already been slightly affected. In the Carnegie Hall Q&A, Rowling related how she scotched a scene in the script where Dumbledore reminiscences romantically about a young lady by passing along a note that the character is gay. Given that the object of Dumbledore’s putative past affections, Grindelwald, will presumably figure in the seventh film, it’s quite possible that Rowling’s statements will affect the portrayal of that relationship. While she is not one of the filmmakers, she scrutinizes the scriptwriting process closely, and whatever makes it into the movies might be considered as canon in some sense.

Finally, one could argue that Rowling’s voice is not simply one among many who might comment on the subject of her books. Setting aside aesthetic theory, for most people in the real world her authority as the author simply is more compelling than anyone else’s. Don’t believe it? What if Stephen King wrote a column announcing that Dumbledore is definitely not gay? (Not that he’s likely to do so.) Would we be inclined to believe him as much as Rowling just because he is also one of the most successful current writers and a fan of the series? I doubt it. What if Pat Robertson preached a sermon stating that Dumbledore is so admirable that he could not possibly be gay? Might we not indignantly counter him by saying, “He is, too. Rowling says so.” It’s the only concrete evidence we have.*

Robertson probably wouldn’t make such a claim. Much of the far right is already up in arms against Rowling. They don’t seem to doubt for a minute her after-the-fact statement that she has written a gay character. They not only believe it but they denounce it as part of some liberal plot to promote homosexuality as normal. For once they’re not far off.

Such claims suggest that we might have political reasons to accept Rowling’s outing of Dumbledore as authoritative—and presumably her remarks about other characters as well. We might want the overall theme of tolerance that is so evident in the series to extend to homosexuality. Clearly Rowling does, too. And she knows what it means. At a signing in Los Angeles a few days before the Carnegie Hall outing, Rowling stated, “I take my inclusion on the banned book list as a massive compliment.”

The Timing of the Revelation

Many comments have been made about the timing of Rowling’s announcement. If she’s so proud of having her books banned, why didn’t she speak up before? Was there a hidden, cynical motive for waiting until all the books were published? Was she trying to avoid losing sales by not revealing Dumbledore’s gayness while the books were still coming out? Was she trying to boost sales of the books after the series’ conclusion by stirring up controversy?

I’ve already argued that the second reason is unlikely. Rowling answered a child’s question on the spur of the moment. (The questions asked by the children in such sessions are pre-screened, but it seems unlikely that the assistants who do the screening convey the questions to Rowling ahead of time.)

How much will sales be boosted now that she has told the public about Dumbledore? This series is such a huge seller that it’s hard to imagine anyone, other than gay men, deciding to buy it solely because Dumbledore has been revealed to be gay. Surely no kids would buy it for that reason. OK, maybe a few liberal parents desiring an uplifting book for their kids might buy it for them.

But we know how many right-wingers there are in this country and how successful they have been at attacking the teaching of science in schools and at demanding that books be removed from library shelves, including the HP series because it “promotes witchcraft.” Surely the outing of Dumbledore in the midst of the series would have cut significantly into the sales for the rest of the books.

I doubt Rowling calculated it that way, but if she did, she was being smart. Possibly, though, her calculations, if any, were as much or more ideological than monetary. She clearly is a liberal, claiming that one major theme of the HP series is tolerance and that another is suspicion of authority.

(For a discussion of these political aspects of the books, see Keith Olbermann’s October 22 Countdown segment on the Dumbledore outing, in transcript or video form.)

Consider what outing Dumbledore after the book series ended implies. There are undoubtedly millions of children in this country whose parents oppose equality for homosexuals. Many of those children now have all seven books lined up on their bedroom shelves, and they may own several HP franchise products, including DVDs. They adore this series. For many the books are probably their favorite cultural artifact in the world. Now picture what would happen if those ultra-conservative parents march in and declare that everything Potter is going in the garbage because it’s immoral, pro-gay propaganda—or less pleasant terms to that effect.

I can imagine three basic reactions.

One, the child will respond, yes, take these terrible books away, they’re bad for me. Ned Flanders’ sons would say that. Maybe a few others would. Such kids are already indoctrinated, and we will just have to hope that they leave home someday and discover more enlightened views.

Two, the child starts crying, arguing, and defending the books. The parents give up and go away. Now this child of ultra-conservative parents has and will likely re-read a book series whose content–at least according to Rowling–runs counter to their parents’ beliefs. A tiny victory for tolerance, repeated in many homes across the land. Perhaps Rowling’s series will help guide such children, if only in a small way, to be less bigoted than their parents. Indeed, there is reason to hope so. Opposition to gay marriage is already less widespread among young evangelicals than among the older generation, with 81% of those above 30 opposed, 76% among those under 30.

Three, the child starts crying, arguing, and defending the books. The parents are adamant and dispose of all the books and paraphernalia. As a result, the child is upset by a homophobic act. Some such children may grow up primed to realize that homophobia is a bad thing. Others will presumably recover and become as intolerant as their parents.

I suppose there might be some way that a child who has already read the books could become even less tolerant of homosexuality as a result of Dumbledore’s turning out to be gay. It’s hard to believe, but maybe it could happen. On the whole, though, Rowling’s revelation creates a win-tie situation. Kids are either influenced for the good or they remain the same. She has smuggled liberal ideas into the heart of the enemy’s camp in a form that will be difficult to eradicate.

How much can a mere book series, along with its attendant films and franchise products, affect society’s attitudes toward something as important as equal rights for homosexuals? It’s hard to say. On rare occasions, books do have a real impact in society. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a major factor in promoting abolitionism, the Civil War, and the freeing of the slaves. Apart from the Bible, it was the best-selling book of the nineteenth century. Perhaps a phenomenally popular liberal author of our own times can use her influence for good as well.

Do pre-teen children really understand what’s going on when Rowling says Dumbledore is gay? Conservatives complain about her choice to do the outing to an audiences of kids. But as Olbermann points out in the segment linked above, the HP books contain death, persecution, betrayal, torture, revenge, and all sorts of dark things that caring parents would likely want to discuss with children as they read the books. In comparison, to complain about having to explain a professor’s sexual preference, particularly when it intrudes only subtly into the plot, seems absurd.

Traister’s Salon.com article contains a cheering anecdote. She says she learned of Rowling’s revelation from a nine-year-old friend at a wedding. The child “exuberantly announced, ‘Dumbledore is gay!'” Traister asked whether she was surprised by this, and the reply was, “Well, I always thought he loved McGonnagall, but I guess he only loved her like a sister.” If only all reactions to the news could be so sensible.

[Added Oct 30: Today’s Star Bulletin (Hawaii) contains an account of three unflappable fans who attended the Carnegie Hall signing and loved it. A photograph taken by the mother of one of them provides the first image I’ve seen of the event.]

*A less prominent figure, John Mark Reynolds, writing on a Christian site, The Scriptorium, makes exactly this claim in his “Dumbledore Is Not Gay: Taking Stories More Seriously Than the Author.” He argues his case in comparable terms to Mittell’s position that the author has no power to affect a book’s content once it has been published.

Scribble, scribble, scribble

Detective (Godard, 1985).

Another damned, thick, square book! Always scribble, scribble, scribble, eh, Mr. Gibbon?

William Henry, Duke of Gloucester, 1781.

David here:

Kristin kept the blogfires burning while I traveled last week and did UW duties this one. I had a great time at the University of Georgia in Athens (but didn’t see Stipe) and at Emory in Atlanta (but didn’t see Scarlett). At both places I met sharp, energetic students and faculty. I have a couple of blog entries backlogged for posting, but now recent items relating to publications get the pole position.

First, a Japanese translation of our Film Art: An Introduction has just appeared. It’s a very handsome version of the seventh edition, rendered by Fujiki Hideaki and Kitamura Hiroshi. We’re grateful to them and to Nagoya University Press for publishing it.

First, a Japanese translation of our Film Art: An Introduction has just appeared. It’s a very handsome version of the seventh edition, rendered by Fujiki Hideaki and Kitamura Hiroshi. We’re grateful to them and to Nagoya University Press for publishing it.

Second, the University of California Press is having a big sale on many outstanding media titles, from Richard Abel’s books on French silent cinema and André Bazin’s classics of film theory to Michele Hilmes’ study of NBC television and Mike Barrier’s new Disney biography, The Animated Man. To get the discount you must sign up for an e-newsletter, but it’s not intrusive.

Among the books of mine on sale, the biggest bargain is the hardcover edition of Figures Traced in Light (2005), originally priced at $65, now going for $7.95 plus postage. (No, apparently I don’t get the full-price royalties.) You can find this item here. There are also paperback copies of Figures (going for $12.95) and of The Way Hollywood Tells It ($15.95). If you’re inclined, hurry: the sale ends on 31 October.

The biggest news, though, is that I just got my author’s copies of Poetics of Cinema, published last week. For a while Amazon was telling some people who pre-ordered it that copies won’t be available until 27 December, but now, despite what it says here, the book seems ready to ship.

The biggest news, though, is that I just got my author’s copies of Poetics of Cinema, published last week. For a while Amazon was telling some people who pre-ordered it that copies won’t be available until 27 December, but now, despite what it says here, the book seems ready to ship.

Bad news first. Poetics of Cinema is priced at $45 in paperback, with no sellers I know offering it at discount. Go ahead, say it: Very expensive. If you haven’t published a book, you may not know that authors have no say in the pricing of their work. Publishers would never set a price or price ceiling in a contract, and calculations about pricing are based on many factors, including what comparable books sell for. A high cost isn’t my preference, of course; every writer wants to reach as many readers as possible. But unless you blog or self-publish your work, the publisher sets the price.

There are some good reasons for the cost. Running to 500 fairly dense pages and containing over 500 photographs, Poetics of Cinema was a complicated book to produce. I peddled it to other publishers, but they ruled it out as too whopping an investment for them. So Routledge has priced it along lines of comparable books, reckoning in the size of the likely audience (I hope, more than 118.3 readers). I have to thank Bill Germano, then Publishing Director at Routledge, for taking a chance on this project.

From age fifteen or so I’ve been a compulsive writer. Scribble, scribble, scribble. I’ve been at work on one book or another for over thirty years. I’ve got several projects in mind for my next effort, but I’ve held back committing. Is there any point in publishing more books, at least as books?

I mean this as a serious question. Would it have made any difference to me or my readers if Poetics of Cinema appeared as pdfs, available at a price considerably less than $45? Wouldn’t I find more readers? What about variable pricing? If Radiohead can do it, why can’t I? Somebody in film studies should try putting a digital book for sale online; maybe I will. But for a few years at least, this last baggy monster will be available only in dead-tree format.

Poetics: Some puzzles

Gentlemen Marry Brunettes (Richard Sale, 1955).

If you’ve read this far, you may be interested in what the book is about. Most basically, it’s predicated on the belief that we make progress in research by asking questions. Some questions are too deep to be answered—call them mysteries—but others can be answered with a fair degree of precision and reliability. We can turn mysteries into puzzles and puzzles into plausible answers.

Here’s a fairly common sort of composition in Hollywood cinema of the 1940s. This shot from The Killers (1946) displays the sort of steep depth I’ve talked about at various points on this blog and in my other books.

But now here’s an equally tense confrontation at a counter, from Bad Day at Black Rock (1955), made in early CinemaScope.

It doesn’t look much like the 1940s shot. The characters stand far from us, and the figure in the foreground doesn’t loom over the background. The shot is more open, the composition more porous. And unlike The Killers, Bad Day doesn’t contain close-ups of the actors in any scenes.

So questions come to mind. Did John Sturges have to stage the scene in Bad Day this way? Did other filmmakers resort to the same choice? What factors created pressures toward this more spacious format? Could more resourceful filmmakers have done something different? And given that such shots are rare today, what changes made it possible for filmmakers in later years to create the tight anamorphic widescreen close-ups we have now (as here in Cellular)?

Despite all that has been written about CinemaScope and other early widescreen processes, no one has explored, shot by shot, what staging options were used by filmmakers. A chapter in Poetics of Cinema called “CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See Without Glasses” tries to show how filmmakers used the new format to tell their stories. This led them, I propose, to experiment with some staging strategies that, surprisingly, had precedents as far back as the 1910s.

Take another instance. We’re all familiar with recent films that present alternative futures, like Run Lola Run. A story line runs along and then is interrupted, and we switch to the same characters living a different storyline in a parallel universe. The emergence of such “forking path” movies arouses my curiosity. How do they work? How do they make their alternative-reality stories intelligible to the audience? How is it that we’re able to understand them? (After all, the notion of an infinite number of alternative universes to ours is pretty hard to get your head around.) Are such stories a brand-new innovation, or do they have precedents? (Clue: Remember A Christmas Carol?) Why do we see a cluster of these emerging in recent filmmaking?

I tackle these questions in another essay, called “Film Futures.” There I look at several such movies and try to spell out the tacit rules that filmmakers follow and that audiences pick up on. While this story format probably doesn’t constitute a genre, it does obey certain conventions, and I try to chart those. Some films also make some clever innovations in the format, which I also try to trace. The essay as well suggests how the conventions are handled differently in mass-market films like Sliding Doors and in art films like Kieślowski’s Blind Chance.

These two essays, along with the others in the book, try to explain and illustrate an approach to film studies I call film poetics. At bottom, this is an effort to explain why films are designed the way they are: how filmmakers have made certain choices in order to shape our response to their films. How do movies work? How do movies work on us?

Poetics: The project

Vagabond (Varda, 1985).

As a kind of reverse engineering, film poetics looks at both structure and texture. I argue that we ought to study how films are constructed architecturally, as revealed for instance in plot structure or narration. Poetics also concentrates on stylistic patterning, the way filmmakers organize the techniques available to the medium. Poetics traditionally deals as well with thematics, the subjects and ideas that are mobilized by filmmakers and reworked by large-scale form and cinematic style.

Put it this way: I want to know how filmmakers have confronted problems set by others, or created problems for themselves to solve. I want to know how they draw on the past to borrow or modify or reject creative strategies. I want to know filmmakers’ secrets, including the ones they don’t know they know. And I want to know how all this creative activity is shaped to the uptake of spectators in different times and places.

Some of what I’ve written on this blog could illustrate how the poetics-driven perspective works in particular cases. The book offers more such instances, probed in more detail than is possible here. Using a comparative method, I also trace out some general principles of film form and style as they have developed over history.

The book consists of fifteen essays. Some have been published before; those have been revised for this collection. Other essays are newly written. After a somewhat polemical introduction, the first part concentrates on some theoretical problems. The anchoring essay offers a general introduction to the idea of a film poetics, with several examples. (An earlier version is on pdfs here.) In the same essay, I float a model of how film viewers respond to various aspects of films. I distinguish activities of perception, comprehension, and appropriation, and I suggest that a cognitive perspective sheds light on them.

Part I also contains an essay considering how cinematic conventions work. A poetics-based approach will spend a lot of time on norms, traditions, and received routines, for these are often the basis of filmmakers’ creative choices. This essay argues that some conventions are local and require a lot of cultural knowledge, while others are cross-cultural, compelling us to study why certain cinematic strategies seem to crop up across the world.

The second part of Poetics of Cinema considers narrative, one of the most common ways in which films are organized to affect viewers. I wrote a new essay to launch this section, a wide-ranging study called “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative.” The three dimensions I consider are narration, plot structure, and the narrative world. The essay considers how each of these shapes our understanding of a film’s story. This essay ends with a discussion called “Narrators, Implied Authors, and Other Superfluities.”

Some more tightly-focused pieces follow. One is devoted to forking-path plots. Another concentrates on an odd question: What role does forgetting play in our watching a film? Cognitive theory can offer some answers, and I take Mildred Pierce as an example. There’s an update of an essay that has been something of a golden oldie in film courses, “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice.” In a supplement to that piece I suggest some new avenues of inquiry and draw on more examples, notably Varda’s Vagabond (Sans toit ni loi).

The longest piece in Part II is devoted to what I call network narratives. Prototypes of this would be Grand Hotel, Short Cuts, Crash, and Babel. This essay tries to show how a poetics of cinema shed light on this format, currently a very popular one. When I started looking at these movies, I was surprised to discover how many filmmaking traditions work in this vein; I append a filmography with nearly 250 items, and today I could update it with several more. (1) I consider how this option has developed distinctive strategies of narration, plotting, and worldmaking. I also survey some common themes running across network tales, such as the role of chance and fate. The essay finishes with more in-depth analyses of four films: Altman’s Nashville, Iosseliani’s Favoris de la lune, Anderson’s Magnolia, and Jean-Claude Guiget’s Les Passagers.

Poetics: More problems

Bus Stop (Logan, 1955).

Part III moves from questions of narrative to questions of film style, no stranger to this blog. The opening essay is a tribute to Andrew Sarris that appraises his role in making readers of my generation style-conscious. It’s the most personal piece in the book. There follows a study of Robert Reinert, a director in the German silent cinema who might have become much better known if his quite demented Nerven and Opium had been as widely seen as Caligari. The essay “Who Blinked First?” considers how our reaction to films is affected by the ways in which actors use their eyes, including how and when they blink. Big deal, huh? Actually, yes.

The monster essay in this section is the CinemaScope piece, of which I’ve given versions in lecture form over the last couple of years. I argue that some directors responded to the new widescreen technology by adapting certain norms of staging and shooting to the new format, while other filmmakers moved in more adventurous directions. The piece uses the model of problem/solution as a way to understand stylistic continuity and change, a framework I’ve floated in On the History of Film Style as well.

The last four studies in Part III are devoted to style in Asian cinema. There are two essays on Japanese film of the 1920s and 1930s, both expanded somewhat from their original versions. There I argue that we can see Japanese directors as building upon, as well as adventurously departing from, stylistic norms shared by most filmmaking countries of the period. This brace of essays fills out some ideas that I fielded in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, and they should appeal to that growing body of viewers who have developed a passion for Naruse Mikio and Uchida Tomio. It’s gratifying that several of the films I discuss, which I had to study in archives, are now circulating in touring programs.

Poetics of Cinema concludes with two studies of Hong Kong film, one surveying the stylistic tactics by which that very lively tradition excites its audience, the other analyzing the unique innovations of King Hu. The articles are companion pieces to Planet Hong Kong.

Poetics: The mysteries

A Touch of Zen (King Hu, 1970).

As an approach to answering questions about cinema, poetics blends history, criticism, and theory. It requires that we do research into the artistic history of film, looking at styles, genres, narrative modes, and other traditions. It asks for close analysis and interpretation of films. At the same time, it asks broader questions about what principles govern narrative, stylistic patterning, and the like. I’d say it obliges a historian to concentrate on aesthetics; it makes criticism more historical and theoretical; it ties theory to concrete historical conditions and the fine-grain workings of individual films.

Kenneth Burke used to say that you could get a sense of a book by looking at its first and last sentences. My book’s first essay opens this way:

Sometimes our routines seem transparent, and we forget that they have a history.

I think that this captures my concern to look closely at familiar things in film and try to make their principles a little more evident. Yet in trying to make filmmakers’ choices explicit and tracing out the principles undergirding how we make sense of movies, I’m sometimes criticized for simply stating common sense. Poetics can look bland alongside the skywriting swoops of most academic film theory. But skywriting is blurry and dissolves while you look at it. By contrast, clearly setting out some basics of filmic construction and comprehension offers a firmer place to start answering questions about how movies work and work on us.

Poetics tries to produce concrete, approximately true claims about cinema. Most film theory operates as an application, borrowing big theories of culture, identity, nationhood, and the like and then mapping them onto films. The results are usually thin. It seems to me that most film theory today is not carefully thought through or persuasively argued. For examples, see my essay in Post-Theory, the last chapter of Figures, and my comments here and here on this site.

In trying to establish reliable knowledge about cinema, we won’t answer every question and we will make false steps, but we can make progress. Film poetics is one way we film enthusiasts can join that tradition of rational and empirical inquiry which remains our most dependable path to knowledge. My introduction, though peppered with some pokes at Big Theory, has the serious purpose of making a plea for film scholars to join that tradition.

The final line of the book concludes the essay on King Hu:

The mainstream [Hong Kong] style has given us many beautiful and stirring films, but Hu’s eccentric explorations evoke something that other directors’ works seldom arouse: a sense that extraordinary physical achievement, if caught through precisely adjusted imperfections, becomes marvelous.

To get the full point you need to read the essay, but what should come through here is my concern to highlight filmmakers’ originality when I find it, and to locate it by means of a comparative method. In addition, I hope that what comes through is an appreciation of the sheer exhilaration we feel when a filmmaker has made the right, bold choice. A poetics-based approach probably can’t fully explain this feeling—it may fall under the heading of mysteries rather than puzzles—but at least it can reveal how some forces contribute to it.

My summary, and the size of the book, may leave the impression that I think that I’ve answered these questions fully. Of course I don’t. I try only to make some progress, realizing that offering answers is also an invitation to disagree, to refine the questions and tackle new ones. Nor do I think that these are the only questions that matter. We’re just starting to understand how films work and work on us, and there are a great many areas we haven’t charted. (Performance, to take a big one.) We have to start somewhere, though. I’d hope that by posing some questions and proposing some answers, Poetics of Cinema offers fruitful points of departure.

(1) Some candidates are 25 Fireman Street (1973, Hungary, István Szabó), Feast of Love (2007, US, Robert Benton), Continental—A Film without Guns (2007, Canada/ Stephane Lafleur), The Edge of Heaven (2007, Germany/ Turkey, Fatih Akin), Unfinished Stories (2007, Iran, Pourya Azarbayjani), God Man Dog (2007, Taiwan, Singing Chen [Chen Hsin-hsuan]), A Century’s End (2000, Korea, Song Neung-han), and Why Did I Get Married? (2007, US Tyler Perry).

A Moment of Innocence (Mohsen Makhmalbaf, 1996).

Crix Nix Variety’s Tics

Kristin here–

Today Anne Thompson’s blog contains a short entry linking to an “acerbic Brit Blogger” who has objected to the language used in Variety. The writer in question is Ronald Bergan, whose title sums up his claim: “It’s time Variety started speaking English.”

Bergan acknowledges that Variety is the best source of news on film, film festivals, and reviews. (The journal also covers TV and theater, as well as occasionally music and videogames.) But, he adds, “Pity then that it is unreadable.” Bergan attributes the cause to “Varietyese.” “Sticks Nix Hick Pix,” which he cites from the 1930s, is the sort of joke that has “now worn thin.”

Bergan also quotes a passage rife with what Variety itself terms “slanguage”: “The rookie self-distribbed indie pic, helmed and lensed by Alan Smithee, is geared for upscale fest auds and urban markets, particularly in Euro zones west and east. But the protags are too high-hat for wider BO appeal. Most perfs are boffo and tech contributions are on the money.” His opinion is that “This sort of writing not only degrades film criticism and demeans reviewers but debases the English language.”

Thompson, unfazed, responds, “I enjoy throwing around slanguage like prexy, helmer, boffo and pics with legs. They’re ingrained in my brain. What’s not to like?”

What, indeed? Anne, there’s plenty of mitting for your position, despite a few sour comments agreeing with Bergan that have been posted in response to your entry. As you point out, the heavier use of terms that might be unfamiliar to many comes in the print versions of Variety. The website, available to a broader public, tones them down distinctly. Given how much it costs to subscribe to the print edition, presumably mostly industry insiders (and some film historians) are reading it. Speaking as one who looks forward to the arrival of Variety every week and reads the film parts immediately, I enjoy its distinctive prose.

I occasionally run across a slanguage term I don’t recognize. Usually they’re pretty easy to figure out. As a hypothetical headline, “Thesp Ankles Ten-percenter” is a little odd, but couldn’t a reader figure out that an actor has left his or her agent? OK, it’s a little obscure, but I for one find it charming rather than annoying. And if I can’t figure a term out, I can check Variety‘s online slanguage dictionary.

Indeed, I’d like to suggest that slanguage is only one element in a Variety style. It’s partly the breezy tone, whether slanguage is employed or not. It’s most evident in the headlines, which can draw upon a number of devices. I can think of at least three. These examples come from the October 22-28, 2007 print edition.

There’s rhyming, as most famously represented by “Sticks Nix Hick Pix.” Most aren’t that spectacular, but there’s the subtler “Studios try slower pace to kudos race.” (That’s for one of Thompson’s own stories.)

There is insistent alliteration, which is a pretty common tactic. Three instances: “Super-size Skeins Shrink Skeds”; “Brooks Book is Biz’s Bible”; and “Claques Click with Canucks.”

Finally, there’s the pun on a familiar title or phrase: “Puttin’ on the Snits.”

These are all fairly ordinary Varietyese. I wish I could remember some of the past titles that have made me laugh out loud. Glancing through my files, I could only find one of those, on a story concerning studio head Michael De Luca’s abrupt departure from New Line Cinema in early 2001 (above).

Dignified? No, but Variety covers the entertainment industries, and why should it not take on a little of the spirit of its subject?

When I was writing The Frodo Franchise, I wanted to make its style appealing. I wanted it to be clear that it wasn’t just an academic tome but one aimed at the general reader—especially fans of the Lord of the Rings trilogy. Of course there are the standard tricks, such as starting chapters with an intriguing anecdote or with a surprising fact. It occurred to me that maybe I could lighten the tone with some amusing titles for the chapters and their subsections. What better model to follow than Variety?

I began to appreciate the challenges a Variety title-writer must face. In some cases I came up with some decent ones, falling into the three types I listed above—not that I thought about the categories while waiting for inspiration to strike. I’ve read the trades long enough to know what an authentic Varietyese title sounds like.

Rhyme: “Last Ditch for PJ Pitch” for the section where I talk about Peter Jackson’s presentation of his project to New Line head Bob Shaye.

Alliteration: The book title itself, and the chapter “Flying Billboards and FAQs.”

Puns on familiar phrases: “In the Darkness Spellbind Them,” on the release and success of the films, and my personal favorite, “Zaentz and Zaentz-ability,” on Miramax’s negotiations with producer Saul Zaentz for the Rings production rights. A zinger of a Variety headline should make you groan at the silliness and yet at the same time shake your head with admiration.

But I couldn’t think of such “headline” titles for every chapter and subsection. Many of them ended up being just plain and descriptive. Still, I tried in every case. It was fun.

That brings us back to the Bergan blog entry. He seems to believe that Variety’s writers are forced to write such stuff by their employers and ends his entry by urging them to “go on strike for more textual flexibility. I can see the headline now: Hax Nix Variety Lingo.”

The author presumably thinks that that headline typifies Varietyese, but it really doesn’t. It has no rhyme, no alliteration, no pun, and no slanguage words. Bergan just made up “hax” to echo the “Sticks” title quoted above. (Pretty insulting to Variety scribes, too.) I’ll never be good enough or quick enough at this to get a job at Variety. Still, I offer the title of this entry as more in the magazine’s true spirit.

A turning point in digital projection?

Kristin here–

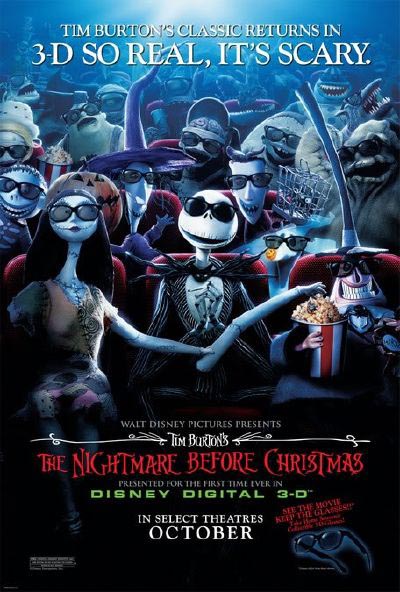

This past Friday, October 19, marked an historic moment in the history of Madison movie-going. We got our first permanent digital projection set-up, and not just digital, but 3D. The first film to be presented there was Tim Burton’s The Nightmare before Christmas.

We’ve had several big changes in the local theater scene recently. In May the first purpose-built Sundance Cinemas art-film multiplex opened. Madison, I gather, is considered a pretty good moviegoing market for its size. A more modest two-screen theater, the Hilldale, was shut down and demolished. Not such a bad thing, since the Hilldale, a two-screen house, was not aging well. We now have two multiple-screen theaters showing nothing but art films, Westgate and Sundance, as well as the Orpheum theater, University of Wisconsin union, and the Communication Arts Department’s Cinematheque showing art films part-time. Overall the city has a total of something like 60 screens for a population of just over 200,000.

Film vs. Digital: The Film Scholar’s Perspective

As film historians, David and I like to work directly with films. This summer he posted an entry on the joys and possibilities of analyzing films on a flatbed editing table. We used to insist that all the frame enlargements we used to illustrate our books be from film. We acquired hundreds of trailers and patiently cut them up, mounting them in slide frames to use in lectures. Naturally they looked great. For older films, we went to archives and used special photographic equipment to capture frames. Eventually DVD technology got good enough that we had to admit frames captured from them could look as good on the pages of a textbook as reproductions from our slides or negatives. Now Film Art and our other books contain illustrations from a mixture of sources.

But obtaining images for illustrations is a very different thing from watching a movie projected digitally in a theater. The images from a strip of real film have a distinctive look to them. They convey a sense of life. It’s a subtle thing, but the minute grains that make up the blacks, whites, and colors in the frames shimmer slightly from frame to frame. (That’s why a freeze frame makes an image look suddenly grainy. There’s no play of the particles from frame to frame to overlap and create a richness.) Digital projection throws visual information on the screen far faster, eliminating the shimmer and creating instead a fixed-looking image.

So we’re not in a great hurry to see 35mm projection disappear, and we watch the growth of digital exhibition with both interest and some trepidation.

The Slow Progress of Digital Projection

Digital projection has been around for years now, but for most of those years we lovers of 35mm film could largely ignore it. The earliest digital screenings of films in theaters took place way back in 1998, with satellites beaming The Last Broadcast into the few American houses with the proper equipped. Every now and then other digital advances would be touted, but the installation of digital projection equipment around the world has been slow.

Some of the reasons for that slowness are obvious. As usual with such technological breakthroughs, there have been competing systems. There still are. The cost of such a projection system is around $150,000. Tell your theater-chain owner holding nine sites, each with ten screens, that he or she needs to make an expenditure of $13.5 million and see what the response is. Especially if that owner has fairly new, expensive 35mm projectors already installed. The theater owners have argued that the distributors should pay part of the costs. The distributors, naturally, want the exhibitors to pay.

Both groups would gain advantages from digital. Among those are savings in printing up thousands of copies of a given film, usually at over a thousand dollars apiece, and shipping the very heavy prints via overnight courier service. There would be no physical prints going through projector gates and suffering scratches and breakage.

Assuming theater owners will end up paying for most or all of the conversion, they would want to charge extra in order to make up the costs of the equipment. There are undoubtedly people who think digital is superior, and they would pay a higher admission price. A lot of moviegoers, however, couldn’t care less whether the moving image they see in the multiplex is coming out of a 35mm projector or a digital one—and they’re probably not about to pay a dollar or two more to go in the digital auditorium that’s playing The Bourne Ultimatum rather than the one with the old-fashioned 35mm system.

Until now, that is. Modifications of projection systems that allow for 3-D projection have finally given exhibitors a selling point that will get patrons into theaters at advanced prices. Our local multiplex that is showing Nightmare is charging two dollars more for it than for films on its other screens. Apparently people will pay. Nationwide this weekend Nightmare is estimated to make $5,245,000 in 564 theaters, for a per-screen average of $9,122. That’s the highest average in the top 25 films. In contrast, 30 Days of Night, the top grosser at $16 million, has a $5,604 per-screen average.

The question remains, will people remain willing to pay extra for 3-D once its novelty value wears off?

2007 is increasingly being touted as the year when digital installations have speeded up most radically. The conversion will still be a slow process, but for the first time it becomes plausible to think that in the not too distant future digital might kill off 35mm projection. In the October 13-14 issue of The Hollywood Reporter, Gregg Kilday, its editor, suggests that 2009 will be the breakthrough year for digital 3-D. Two major 3-D projects, DreamWorks’ animated Monsters vs. Aliens and James Cameron’s Avatar, will debut within a few months of each other. The real question, he says, is whether enough theaters will be outfitted with digital projection by then. With big theater chains now adopting the new technology, it seems quite possible. (See here for an excellent summary of the current situation of theater conversion and 3-D films in the pipeline.)

Alone with my 3D Glasses

As I was sitting at my desk last Wednesday afternoon, finishing up my David Cronenberg entry, I got a call from a friend of ours, Tim Romano. Tim is an expert projectionist, perhaps the best in town. He’s the one theaters often call on to test new equipment and screen the big blockbusters ahead of time to check for flaws. Not surprisingly, Tim was testing the new digital projector by running Nightmare over and over, as if for a regular day’s screenings, but without an audience. Tim suggested that I might want to drop in and catch a screening. Naturally I headed for we call Point, which is really the Marcus Point UltraScreen Cinema.

As the name suggests, Point is part of the Marcus Theatres Corporation’s chain of 47 theaters (594 screens), scattered across Wisconsin, Illinois, Minnesota, Ohio, North Dakota, and Iowa. Some of the chain’s other theaters will be getting digital projection installations as well. The name Marcus is a big one here in the Midwest, since The Marcus Corporation also owns or manages 20 hotels in the area. Its theater chain is the seventh largest in the country.

Arriving at Point, I received my 3-D glasses from the ticket seller, obtained my snack of choice (Junior Mints), and headed for what proved to be an otherwise empty auditorium. I had missed the opening, but having seen the film a couple of times, I figured that didn’t matter. I was here to see what digital 3-D looks like.

When we go to the movies, David and I usually sit in the center of rows three to five, depending on the size of the screen. This time I sat in row five, but I quickly found the edges of the eyepieces were not wide enough to take in the entire screen. There’s an aisle across the auditorium behind the fifth row, so I sat at the front of the upper section of the house, approximately row eight. That worked fine.

I’m not sure the glasses I had were the same kind that are being used for commercial screenings. Still, my impression is that if you’re used to being down front, sitting a bit further back works well for this film.

Nightmare was originally made on 35mm film using stop-motion to animate puppets. It was transformed into a 3-D film using technology from a company called Real D, which also has been the major player in the move to install digital projection equipment in theaters.

Tim wasn’t, however, projecting Nightmare on a Real D projection setup. Just recently Dolby has moved into digital projection in a big way, and the Point installation is part of its rollout of competing equipment. (For details and other cinema chains using Dolby, see here.) Dolby may have the edge, since its projector works with existing white screens, while Real D’s requires a special silver one.

Happily, the new polarized glasses work better than earlier models. My experience with the older glasses was that one’s eyes sometimes had to struggle to resolve the images onscreen into three dimensions, and one could end up with a headache by the end of the movie. Dolby’s digital 3-D system makes perception of the depth effects automatic and effortless.

Speaking of the glasses, I was amused to note that publicity for the film (see the poster above) shows the characters wearing what look very much like sunglasses. Most probably people still think of 3-D glasses as clunky and cumbersome. This is clearly an attempt to counter that image and make the glasses look cool, like the ones sported by characters in Men in Black or The Matrix.

The depth effect is definitely impressive, even in a retro-fitted film like Nightmare. Because it was not originally produced in 3-D, most of the depth appears to extend behind the screen. I remember seeing 3-D films made in the 1950s that strive to thrust objects out at the audience—most effectively in House of Wax when a carnival barker has a paddle-ball that he bounces directly toward the camera. I rather prefer the depth behind the screen to the depth in front, which tends to be distracting. Whatever the promoters say about people wanting to feel themselves in the movie, I would prefer not to have projectiles coming at my face or actors tumbling into my lap.

The movement of the characters was fine most of the time. I found that rapid action caused a ghosting, blurred effect that was quite different from the rock-steady three-dimentionality of static or slowly moving figures. That ghosting may simply be an artifact of the process of turning 2-D into 3-D, and perhaps films made in 3-D will not have it.

Then there’s the matter of grain and other qualities of 35mm film. Certainly one can’t object to the lack of dust and scratches. The absence of grain is a little disconcerting, but it’s really hard to judge in an animated film like this. Presumably, though, it’s not significantly different from 2-D digital projection, which I’ve never seen. I suppose I shall get used to it.

The Current Trend

So Nightmare provides only a limited indication of what the future holds.

Thus far animated films have made up the bulk of the digital 3-D films released. It’s much easier and cheaper to build 3-D into a CGI cartoon (e.g., Disney’s Meet the Robinsons) than to use it on the set of a live-action film. Indeed, the current generation of 3-D features that include actors have employed motion-capture technology. The proof of that pudding will come with Robert Zemekis’s Beowulf, due out November 16.

The real future of 3-D will depend on it attracting adult audiences, and that means that more live-action films will need to be made. That’s not happening now because the technology remains to expensive, cumbersome, and touchy to be easily used on set. The technology is bound to advance, though.

In the meantime, possibly we can expect that for the near future, digitally equipped auditoriums will be a little like Imax is now. A multiplex might have one Imax screen, but it would never put Imax in all its other theaters. Similarly, a theater owner might be willing to pay that $150,000 to convert one projection system in a multiplex, with digital 3D remaining a special attraction, one which people are willing to pay a little extra for.

If such a scenario is fulfilled, then we may see 35mm and digital share the multiplexes of the world for a long time. You wouldn’t hear me complaining.