Archive for the 'Film history' Category

Tracking down Aardman creatures in 2008

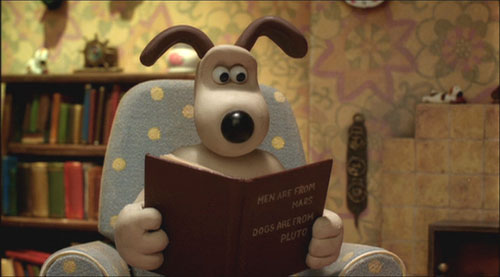

Cracking Contraptions: The Tellyscope.

David’s health situation has made it difficult for our household to maintain this blog. We don’t want it to fade away, though, so we’ve decided to select previous entries from our backlist to republish. These are items that chime with current developments or that we think might languish undiscovered among our 1094 entries over now 17 years (!). We hope that we will introduce new readers to our efforts and remind loyal readers of entries they may have once enjoyed.

On Friday, December 15, Chicken Run: Dawn of the Nugget will have its American streaming release on Netflix. I’ve been a fan of the film’s producer, Aardman, since David and I saw a compilation of the three original Wallace and Gromit shorts, including the sublime The Wrong Trousers, in a theater. On January 28, 2008 I posted a long entry on Aardman’s history to that time, including a chronology of all its releases. Aardman has been so productive since then that I could not possibly update this entry. The company has been extremely successful in the area of television series, such as those featuring Shaun the Sheep, thus multiplying the number of titles created. Nevertheless, I think this entry offers some useful information on the early period of the studio.

Kristin here—

David and I are currently plugging away on revising our Film History textbook. In setting out to update the section on Aardman animation, I ran into difficulties pinning down the dates of certain television series or the director of a given short film. Indeed, I was quite surprised at the dearth of complete chronologies or filmographies for such a famous and important company.

The obvious sources such as Wikipedia and the Internet Movie Data Base, are helpful but sketchy. Aardman’s own “History” section on its official website is even briefer–and ends in 2005. The filmography in Peter Lord and Brian Sibley’s coffee-table book, Creating 3-D Animation (p. 189), is far from complete. (I must confess that I’m still using the first edition, but even so the filmography is sketchy for the period it covered. The revised edition came out in 2004.) Each source was, however, incomplete in different ways. I decided to try and compile as comprehensive a chronology/filmography as I could as a research and reference tool. This turned out to be a considerable task. Given how little of this work will end up in the textbook, I decided that I might as well offer it to the world.

I expected to find one or more fan-originated sites that would provide additional information, as so often happens in the world of popular culture. The main “unofficial” site that came up when I Googled Aardman is actually an online shop with scarcely any actual information.

What follows is not by any means complete. It’s more like a rough draft for a filmography, though it’s more detailed than any that I have found so far. No doubt it has gaps and perhaps inaccuracies. One problem I encountered is that dates given in various filmographies seem to waver between when a film was made, when it was copyrighted, and when it was released to theaters or first shown in TV. I’ve tried to stick to release/broadcast dates when I could find them.

Aardman has produced many ephemeral animations for station-identification logos, credit sequences, and websites, as well as perhaps hundreds of commercials. I’ve made no attempt to include commercials, apart from the Heat Electric series, which are available on DVD. The following primarily includes television shorts and series, as well as films.

My main sources of information are: The Internet Movie Datebase; the history section of Aardman’s official website (which ends with 2005); the Big Cartoon Database’s Aardman page; Lord and Sibley’s Creating 3-D Animation; Insideaard (a booklet included in the British DVD Aardman Classics); and the credits of various Aardman films on DVD and on AtomFilms. Some details have been filled in from the Wikipedia entries on Nick Park and Steve Box. The main Aardman entry is so far rather sketchy, though it includes some films not listed in other filmographies and links to entries on the individual films and series, given below.

[Added January 29: Aardman itself might seem to be the ideal place to start, but the company doesn’t currently have a list of all its productions. It recently hired an archivist who, among other tasks, plans to compile such a list, including the commercials. In the meantime, this entry can serve as a stop-gap reference source.]

* indicates a music video, as identified in Lord and Sibley.

1970s

c. 1972, Friends and amateur animations Peter Lord and David Sproxton sell an untitled cel short featuring a “Superman” gag (illustrated on p. 10 of Lord and Sibley) to the BBC for about ₤15, for its “Vision On” series (producer Patrick Dowling; aimed at deaf children). The superhero’s name, Aardman, would give the pair’s company its name.

1976 Aardman Animation founded.

1976 Aardman Animation founded.

1978 Two films for Animated Conversations series, BBC: Down and Out (copyright 1977) and Confessions of a Foyer Girl (left; both dir. Lord and Sproxton). First use of real-life interviews for soundtracks.

1980s

1979-1982 Morph shorts for BBC. Initially part of Vision On series, then Take Hart, and finally on its own as The Amazing Adventures of Morph (dated 1981-83 in Lord and Sibley; 1980-81 on imdb).

c. 1982 Aardman starts making commercials. This becomes the financial staple of the studio and allows the company to move into larger facilities and hire more staff. Thereafter Aardman has produced 25-30 commercials a year. Lord and Sibley’s filmography contains a list of the products/companies for which Aardman made commercials from 1982 to 1998, but listed alphabetically without individual dates. (A few of these are on YouTube, such as this one for Chevron.)

1983 Conversation Pieces series: Sales Pitch, Palmy Days, Late Edition, Early Bird, and On Probation (dir. Lord and Sproxton). All shown during one week on Channel Four for its first anniversary.

1985 Nick Park joins Aardman full time.

1986 Babylon (Lord and Sproxton) First film that Nick Park worked on. Channel Four.

* Sledgehammer (dir. Stephen Johnson; Aardman’s portion animated by Park, Lord, Richard Goleszowski) Peter Gabriel music video.

1986-91 Aardman provides the Penny segments for five seasons of Pee-wee’s Playhouse, CBS.

* 1987 My Baby Just Cares for Me (dir. Lord; right).

Going Equipped (dir. Lord).

* Barefootin’ (dir. Goleszowski) On YouTube.

* 1988 Harvest for the World (one sequence, dir. Sproxton, Lord, and Goleszowski).

1989 Lip Sync series: Next (dir. Barry Purves; left), Ident (dir. Goleszowski; first appearance of Rex the Runt), Going Equipped (dir. Lord), Creature Comforts (dir. Park), War Story (dir. Lord) Channel Four.

1989 Lip Sync series: Next (dir. Barry Purves; left), Ident (dir. Goleszowski; first appearance of Rex the Runt), Going Equipped (dir. Lord), Creature Comforts (dir. Park), War Story (dir. Lord) Channel Four.

Creature Comforts spawns the Heat Electric series of ads.

A Grand Day Out (dir. Park) Produced by the National Film & Television School and finished with help from Aardman. The introduction of Wallace & Gromit.

Lifting the Blues (dir. Sproxton).

1990s

1990 Steve Box joins Aardman.

1990-91 Rex the Runt: How Dinosaurs Became Extinct (dir. Goleszowski).

1991 Adam (Lord; right).

1991 Adam (Lord; right).

Rex the Runt: Dreams (Goloeszowski).

1992 Never Say Pink Fury Die (dir. Louise Spraggon).

Love Me … Loves me Not (dir. Jeff Newitt).

1993 The Wrong Trousers (dir. Park). Co-financed by Aardman and the BBC. Shown during the Christmas season.

Not without My Handbag (dir. Boris Kossmehl) Channel Four.

1994 Pib & Pog (dir. Peter Peake; left).

1994 Pib & Pog (dir. Peter Peake; left).

1995 A Close Shave (dir. Park), shown on the BBC at Christmas.

The Title Sequence (dir. Luis Cook and Dave Alex Riddett).

The Morph Files (dir. Lord and Sproxton) BBC.

1996 Rex the Runt: North by North Pole (Goleszowski) “Pilot”.

Wat’s Pig (dir. Lord) Channel Four.

Pop (dir. Sam Fell)

* Never in Your Wildest Dreams (dir. Bill Mather).

1997 Dreamworks pre-buys the U.S. rights to Chicken Run.

1997 Dreamworks pre-buys the U.S. rights to Chicken Run.

Stage Fright (dir. Box, right).

Owzat (dir. Mark Brierly)

1998 Humdrum (dir. Peake) Channel Four and Canal +.

Al Dente (dir. Brierly).

Rex the Runt (dir. Goleszowski) 13 episodes for BBC2, aired December 1998 to January 1999.

The Angry Kid series (dir. Darren Walsh) 3 episodes posted on the internet by AtomFilms.

* Viva Forever (dir. Box).

1999 The Angry Kid (dir. Darren Walsh) 13 episodes distributed on the internet by AtomFilms.

Minotaur and Little Nerkin (dir. Nick Mackie) Theatrical release.

Rabbits! (dir. Sam Fell).

2000s

2000 The Angry Kid (dir. Walsh) episodes 14-25 (continuation of season one).

Chicken Run (dir. Lord and Park) Aardman’s first feature. Released in the U.S. by DreamWorks and in the U.K. by Pathé.

Non-Domestic Appliance (dir. Sergio Delfino) This and the next four films were posted on AtomFilms in 2003.

Chunga Chui (dir. Stefano Cassini).

Comfy (dir. Seth Watkins).

Ernest (dir. Darren Robbie)

Hot Shot (dir. Michael Cash).

2001 Rex the Runt (dir. Golwszowski; left) second season, BBC2, 13 episodes, aired September to December.

2001 Rex the Runt (dir. Golwszowski; left) second season, BBC2, 13 episodes, aired September to December.

The Deadline (dir. Stefan Marjoram) A CGI short imitating Aardman’s traditional claymation style, made for an Aardman retrospective in New York. Nickelodeon subsequently commissioned twenty one-minute episodes with the same characters to create the series The Presenters (The Deadline on YouTube.).

2002 Cracking Contraptions (dir. Lloyd Price and Christopher Sadler) Ten episodes shown by BBC during the Christmas season.

Chump (dir. Fell) Theatrical.

2003 Creature Comforts (dir. Goleszowski) First season, 13 episodes, ITV1.

The Angry Kid moves from the internet to BBC3.

2004 The Angry Kid: Who Do You Think You Are? (dir. Walsh) 22 minute film outside the series.

2005 Wallace & Gromit in The Curse of the Were-Rabbit (dir. Box and Park) Released in the U.S. by DreamWorks and in the U.K. by United International Pictures.

Planet Sketch (dir. ?) 13 episodes, 2005-2006. For a breakdown of episodes, see the Wikipedia entry.

Creature Comforts, second season, ITV starting in October.

2006 Flushed Away (dir. David Bowers and Fell) Distributed in the U.S. by DreamWorks and in the U.K. by United International Pictures. Aardman’s first CGI feature.

Purple and Brown (dir. Richard Webber) 21 episodes, Nickelodeon U.K. (Episode list on Wikipedia; a collection of the YouTube postings have been collected here, with some repetition.)

2007 January, DreamWorks terminates its five-feature contract with Aardman (claiming a write-off of $25 million for Wallace & Gromit in The Curse of the Were-Rabbit and $109 million for Flushed Away).

Pib and Pog (dir. Peake) Five shorts for the AtomFilms site: The Kitchen, X-Factor, Peter’s Room, Daddy’s Study, and The Dentist (copyright date 2006).

April, Sony announces that it has a deal to distribute Aardman features.

Shaun the Sheep (dir. Sadler) 20 episodes, BBC, first series March, second series September.

Creature Comforts America (dir. ?) CBS, seven episodes. Three episodes aired in June, and the rest were cancelled due to low ratings.

The Pearce Sisters (dir. Cook) Theatrical.

Chop Socky Chooks (dir. Delfino) 26 episodes, Cartoon Network (For character list, see Wikipedia entry).

2008 Creature Discomforts (dir. Steve Harding-Hill) Four public-service spots featuring disabled characters (with sound provided by people with disabilities), on ITV beginning January (also online).

Wallace and Gromit in Trouble at Mill (dir. Park) Half-hour Wallace & Gromit film to be shown by the BBC at Christmas.

[February 19, 2009: This films was shown under the title Wallace and Gromit: A Matter of Loaf and Death. The DVD is currently available for pre-orders on Amazon.UK and will be released March 23.]

1000 Sing’n Slugs (dir. ?) Bonus disc for re-issue of Flushed Away.

2009 Announcement of Timmy (dir. Jackie Cockle) Spin-off from “Shaun the Sheep” aimed at pre-schoolers. 52 ten-minute episodes for BBC.

These features are currently announced as in progress: Tortoise vs. Hare (2009), Pirates (2009), Untitled Wallace & Gromit project (2010), Operation Rudolph (2010), and The Cat Burglars (2010).

Aardman has a CGI department mainly used for commercials and station-identification logos, including BBC’s three Blob spots, Nickelodeon’s Presenters, and BBC2’s Booksworms

Lord and Sibley list an undated, untitled public-information film on HIV/AIDS.

DVDs and the Internet

I won’t attempt a complete list of DVDs, given that some of these films have been repackaged in various compilations. I’ll mention the ones in our own collection, which cover most of what is available on DVD.

Leaving aside the Wallace & Gromit films for now, the crucial DVD for the studio’s output is Aardman Classics, which contains 25 shorts plus 12 Heat Electric ads that use interviews with animals in the style of Creature Comforts. Unfortunately this DVD was issued only in the U.K. [Added January 22: It was also issued in Australia with Region 4 coding.] It’s still available, and if you have a multi-standard player and are interested in Aardman, I can’t recommend it highly enough. It contains most of the films to 1998, going back to Confessions of a Foyer Girl and Down and Out. Presumably for rights reasons, it does not include the classic music video, Sledgehammer.

American viewers restricted to Region 1 DVDs have far less available to them. The American DVD of Creature Comforts (now out of print) contained only three other Aardman films: Wat’s Pig, Adam, and Not without My Handbag (left)—among the best, no doubt, but far from the cornucopia on Aardman Classics.

American viewers restricted to Region 1 DVDs have far less available to them. The American DVD of Creature Comforts (now out of print) contained only three other Aardman films: Wat’s Pig, Adam, and Not without My Handbag (left)—among the best, no doubt, but far from the cornucopia on Aardman Classics.

Sledgehammer is included on the Peter Gabriel: Play the Videos DVD. I assume the quality there is distinctly better than the many copies available on YouTube and elsewhere on the Internet. By the way, the Quay Brothers did the rest of the animation for Sledgehammer.

Some of the TV series are available on DVD. Both seasons of “Rex the Runt” were released as a boxed set in the U.S. It’s rather pricey but has a 260-minute running time and some minor extras. The British DVD of the first season of The Angry Kid is now out of print. Both seasons of the British series Creature Comforts are available as a set in the U.S. The ill-fated “Creature Comforts America” has also been released. So far the two “Shaun the Sheep” series are only available in the U.K., separately or in a boxed set containing both.

Chicken Run, Wallace & Gromit in The Curse of the Were-Rabbit, and Flushed Away are all out on DVD. (The Were-Rabbit disc includes the classic 1997 Steve Box short, Stage Fright, as well as some good making-of supplements.) I had held off ordering Flushed Away in the hope, probably vain given the film’s weak U.S. box-office showing, that an edition with making-of bonuses will be forthcoming. Now, however, a re-issue (NTSC, but with no region coding) is coming out on February 19. (U.K. here.) It includes a second “all-new slugtacular disc,” 1000 Sing’n Slugs (not sold separately). Forget the making-ofs, my pre-order is in!

Finally, the all-important question: which DVD of the three classic Wallace & Gromit shorts to purchase? For once the American disc, “Wallace & Gromit in Three Amazing Adventures,” has the advantage, in that it includes all ten episodes of the “Cracking Contraptions” series. These are all available on the Aardman website, but for a larger image and better visual quality, fans will want the DVD. The British disc, “Wallace & Gromit: Three Cracking Adventures!” has only the three films and a bonus, “The Amazing World of Wallace & Gromit,” a brief history of Aardman that I remember as being pretty good.

Apart from its own website, the official outlet for Aardman shorts on the Internet is AtomFilms, which currently has lists 37 titles under the category The Best of Aardman. A group of very short films, Non-Domestic Appliance, Chunga Chui, Comfy, Ernest, and Hot Shot (all copyright 2000 but posted in 2003) look to me as if they might have been training exercises for young animators who also worked on Chicken Run. A group of classic films are available: Creature Comforts, Minotaur and Little Nerkin, War Story, Wat’s Pig, Stage Fright, Hundrum, Pop, Owzat, Adam, Al Dente, and Loves Me, Loves Me Not. The original Pib and Pog is also there, as well as a Pib and Pog series of five original shorts posted in 2007. Another series, A Town Called Panic, has six episodes; it is a Belgian production (copyright 2002; see the Wikipedia entry for episodes, characters, and links) which Aardman distributes. It was posted on Atom Film in 2007. There are also several Angry Kid episodes.

There are many Aardman items on YouTube. Many are bad copies of films available elsewhere, but there are some treasures to be found among them. I leave it to you to continue the search.

I would appreciate any corrections, additions, or other significant links that readers can provide.

In a 2006 post, I discussed the problems Dreamworks had in distributing Flushed Away in the US, and in a 2007 post, I discussed the departure of Aardman from Dreamworks.

Cracking Contraptions: The Autochef.

Wisconsin Film Festival 2021: Retrospectating

Keep Rolling (2020).

DB here:

Several of the films I’ve seen this go-round are either revived versions of older films, or recent films indebted to older traditions. Herewith, some thoughts on them.

Tender and tawdry

La Belle de nuit (1934).

I felt less dopey about not knowing about Louis Valray when Serge Bromberg, in an interview on the WFF site with Kelley Conway, confessed he’d not heard of him until he found an incomplete print of Escale (1935) by accident. Bromberg went on to find more footage, discover Valray’s first film, and secure the rights to restore and distribute them. Splendid in their restored versions (with curved corners on the frame), the films are at once generic and pleasingly perverse.

La Belle de nuit (1934) is a boulevard melodrama with hints of Vertigo and Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne. When a playwright discovers his wife has cheated on him with his best friend, he plots vengeance. By chance (i.e., dramaturgy) he finds a prostitute who is almost a dead ringer for the wife. He dresses her up, installs her in an apartment, and coaxes her to adopt a remote, mildly mocking manner. Of course, the treacherous best friend is in a frenzy to possess her. Wait till he learns about the past of his new passion.

La Belle de nuit alternates rather flat scenes of bourgeois flirtation with bursts of cinematic energy. Like other early sound films, there are some sharp auditory transitions. Dynamic hooks link scenes with sounds, images, or both: automobile wheels, locomotives, phonograph records.. There are peculiar angles and, most noticeably, a fascination with the unattainable woman. As ever, cigarette smoke helps the mystique.

I suspect that Valray learned a lot from making this first film because I found Escale a more polished production. Like his debut, it centers on a fallen woman who hangs around hazy cafes where hard-used women stroll among tables and sing about the troubles of life. Jean, an uptight lieutenant on passenger ships, falls in love with Eva, who hangs around smugglers in her seaport town. Jean and Eva share an idyll, and she seems redeemed. But when Jean leaves on a voyage, Eva’s loyal manservant Zama can’t keep her from succumbing to the mesmeric bootlegger Dario.

Escale has more exquisite visuals than La Belle de nuit. Filmed on a lush Mediterranean island, it bathes its landscapes and sea vistas and seedy port with a languid melancholy akin to that of Pépé le Moko (1937). Practically every shot, on land or sea or in the alleys or the boudoir, yields brooding, hypnotic imagery.

I find Escale‘s villain far scarier than the fussbudget playwright of La Belle de nuit. Dario wears more mascara than Eva, but the effect is to give him the burning glance of the true monster.

Both films, available on French DVD, would be a fine double feature for an enterprising US disc publisher or streaming service. Thanks to Bromberg and Lobster Films, they can be seen in their full glory.

A Taiwanese revelation

Just as the Valray films cast a new light on 1930s French cinema, so The End of the Track (1970) puts the standard history of Taiwanese cinema into a fresh perspective. The story is that the New Taiwanese Cinema of the 1980s, developed by Hou Hsiao-hsien, Edward Yang, and others, created a fresh turn toward social realism and more adventurous storytelling. Their tales of rural life and urban anomie clashed with the entertainment genres of commercial cinema and the government-sponsored films asserting that under Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang regime life was buoyant and carefree. With The End of the Track we have a fine predecessor, a “parallel” film that dared formal and thematic opposition to the mainstream, and did so well before the New Wave directors.

Yung-shen’s father and mother run a noodle cart; Hsiao-tung’s family is well-off. But the boys are fast friends. They enjoy long days in their rural paradise–swimming naked, play-fighting, and exploring caves. The film’s first twenty-five minutes are almost plotless, built out of routines of school, play, and homework. But then a crisis strikes, and the film turns achingly sad in a quiet, unmelodramatic way. The plot shifts slowly to a study of how one boy becomes a surrogate son for a grieving family, while his own parents respond uncomprehendingly.

The boys’ skinny-dipping and mud wrestling earned the film a ban for “homosexual undertones and ideology.” There’s surely a homosocial, and maybe homoerotic undercurrent, but the main impression is that of devoted friendship and the heavy weight of obligation. One boy must leave childhood behind, too soon, and start a new life. Just as powerful is the class component. In one grueling sequence, Yung-shen’s parents try to push their cart through typhoon-swept streets as Hsiao-tung’s parents look on from their car.

Pictorially, director Mou Tun-fei makes full use of the glorious scenery that rural Taiwan can yield. He uses fast cutting, handheld shots, abrupt flashbacks, and other “modern cinema” techniques. These techniques can be seen in many commercial Taiwanese films of the period, but most directors used them to jazz up generic plots. Here, the fastidious black-and-white palette gives them a certain sobriety. The gravity is enhanced by severe but lyrical compositions, like this planimetric shot of the boys laying out a running track.

Above all, the slow pace of the film–the basic story is almost an anecdote–allows Mou to soak us in the characters’ milieu. There are even some prolonged, static long shots that look ahead to the precisely unfolding scenes we get in Hou’s films and in Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day (1991).

Mou is now, like Valray, a rediscovered director enjoying belated fame in his national cinema. In a very helpful discussion of his career, Wafa Ghermani and Victor Fan point out that there was at the period an important trend toward independent, low-budget films in Taiwanese (rather than the official language of Mandarin), and Mou’s work is just one example. As usual, a festival screening can remind us that there’s a lot more powerful cinema out there than we’ve realized.

Her time has come

Keep Rolling (2020) isn’t an old film, but it’s about a director who has over forty years quietly carved her own niche in world cinema.

In the 1980s, a new generation of filmmakers overturned Hong Kong cinema. Some, like Tsui Hark, Jackie Chan, and John Woo, brought a turbocharged version of the New Hollywood to a film culture already energized by a tradition of martial-arts action. Other young talents formed what came to be called the Hong Kong New Wave. Although Tsui was sometimes identified with this, this trend was not so brash. It moved toward social realism, with directors like Allen Fong and Stanley Kwan exploring a modernizing Chinese culture living under colonial rule but forging its own identity.

Of all the New Wave directors, Ann Hui distinguished herself by her sincere and dogged attention to Hong Kong life as it is lived. After making some docudramas for television, she directed her first feature, The Secret (1979) and won festival attention with Boat People (1982) and Song of the Exile (1990). Although she has happily embraced genre films–she has made ghost stories and thrillers–she always treats sensational material with a calm, unspectacular attention to characterization and mood. Her swordplay film, the two part Romance of Book and Sword (1987), emphasizes landscape and interpersonal drama over action set-pieces. Who else would make Ah Kam (1996), a martial-arts movie centering on a stuntwoman?? She brought attention to social problems, sometimes in advance of social policies: caring for a parent suffering from dementia (Summer Snow, 1995), the need to shelter victims of marital abuse (Night and Fog, 2009), and lesbian rights in Hong Kong (All About Love, 2010).

In all, she has directed twenty-eight features. Every one has been a struggle.

Because the local market has been small, Hong Kong filmmakers have had to look abroad. For directors like Tsui and Woo, that meant making flamboyant action vehicles for audiences across East Asia, as well as for the Chinese diaspora and fans in other territories. But Ann Hui’s commitment to local life meant that her films had to gain wider attention on the red-carpet circuit. They did. Over the decades, they routinely played the major festivals. Her A Simple Life (2011) got a standing ovation when it played Ebertfest in 2014; Roger called it one of the year’s best films.

Last year Kristin and I were sorry we couldn’t be in Venice to watch her accept a Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement. In response to my email of congratulation, she was characteristically modest in facing a 14-day quarantine when she returned home. As ever, she makes personal contact:

Tonight I am dead beat n have a whole day of press tomorrow before I leave on the day after. I promise myself I’ll only stick to filmmaking from now onwards. How r u and is the pandemic bad in your area? HK is bad all the way you must know. Will u still come n visit us? Take care n keep well! Ann

Ann’s career receives a fitting tribute in Man Lim-chung’s Keep Rolling. It surveys her life, with fine interviews with her sister and brother, along with comments from friends and critics. There’s a lot of behind-the-scenes production footage. Above all, Man offers a personal portrait of her persistence and dedication. Virtually the only female director to make a career in Hong Kong, she has contributed to the world’s humanist cinema shaped by directors like Kurosawa, Kiarostami, and Satayajit Ray. Stubbornly sincere, with no PoMo flash or trickery, her small-scale studies of character always have wider social resonance. One can only hope that this film brings her–and her films, shamefully neglected on DVD–to more audiences.

The four films reviewed above are all available from the Festival across the USA until midnight Thursday. You can sign up here.

The Festival’s Film Guide page links you to free trailers, podcasts, and Q &A sessions for each film.

Thanks as ever to the untiring efforts of Kelley Conway, Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Pauline Lampert, and all their many colleagues, plus the University and the donors and sponsors that make this event possible.

For more on Ann Hui’s visit to Ebertfest, go here. We’ve reviewed many of Ann’s films on this site; check the category. I discuss trends in Hong Kong cinema in Planet Hong Kong and consider some aspects of Taiwanese film in Chapter 5, on Hou, in Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. I sure wish I had known The End of the Track when I wrote that chapter.

The End of the Track (1970).

How the world ended in 1916

The End of the World (1916).

DB here:

The pull-quote might be “Gripping entertainment and a vivid introduction to storytelling strategies characteristic of Danish silent cinema!” (Too long for a poster, though.) It appears in my essay on a remarkable silent film you may not know. I bet you’d like it.

Danish cinema has gripped my interest for about fifty years. Like most cinéphiles, I started with Dreyer, moved on to Christensen, and then just tried to keep up with trends leading to Scherfig, Vinterberg, Winding Refn, Anders Thomas Jensen, and Dogme. There always seemed to be a new comedy or noir or psychological drama or just weird-ass experiment to keep my loyalty (most recently, the well-crafted Another Round).

One of our first blog entries, on 20 October 2006, was devoted to an anthology on the great film company Nordisk. Soon I was chattering about von Trier’s editing in The Boss of It All and surveying a big batch of recent releases.

Now this national cinema’s silent-era history is coming steadily online. The Danes are too modest to brag about the enormous accomplishment of making so many beautifully restored classics available for anyone to watch. But here they are, accompanied by thematic essays from critics and historians.

Like other Little Cinemas That Could (Hong Kong, Taiwan. Iran), Denmark attracts me because it has shown what can be done a lot of imagination on smallish budgets. Or sometimes, biggish budgets. That’s an impulse that emerged in the 1910s when Nordisk was struggling to keep a foothold in the international market during the Great War. One result was a pair of remarkable spectacles.

A Trip to Mars (Himmelskibet, 1918) is a massive, nutty plea for peace and international—make that interplanetary—understanding. The Martians are more or less like us, except they don’t kill other creatures, which leaves them time to assemble in carefully picturesque crowds and invest in ambitious infrastructure projects.

The other big Nordisk production was The End of the World (Verdens Undergang, 1916). A comet is plunging toward earth. Can we avoid collision? Or at least survive?

All the conventions of the cosmic disaster movie (Armageddon, Independence Day, 2012) are already in place. We have the innocent family, the corrupt capitalist squeezing money out of catastrophe, the scientists trying to calm the public, and of course the separated lovers who must find one another in the midst of chaos.

The special effects range from passable to truly impressive, as in the model of the village under fiery bombardment, surmounting today’s entry. The comet’s approach is cleverly suggested as a blip in the sky, and the shots of the heroine’s drowned neighborhood are splendid.

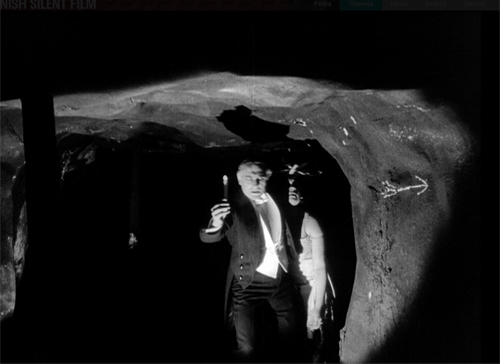

Just as remarkable are other technical achievements. The lighting in the underground passages of the capitalist’s mansion, with its Caligariesque steps, could teach the Germans a few tricks, and the miners’ fierce assault on the plutocrats is cut with rowdy, immersive vigor.

August Blom had made his reputation with Asta Nielsen dramas and another would-be blockbuster (Atlantis, 1913). He’s often considered a stolid director, but The End of the World seems to me an underrated achievement. Dismissed by many critics as over-produced, its ambitious spectacle is probably more to our current taste for overwhelming scale. For us, it seems, too much is never enough.

So I recommend to your attention this remarkable movie. As usual, I throw in a case for the 1910s as one of the great and glorious eras of film history. You can handily sample further evidence in the film links alongside the essay.

Thanks to Thomas Christensen and his colleagues at the Danish Film Archive. It was fun!

There’s always more to say about the Danes. Outside our blog entries, I’ve written about Nordisk and the “tableau aesthetic” and on early Dreyer in another essay on the Danish Film Institute site.

The End of the World (1916).

Rotterdam starts strong

Dear Comrades! (2020)

DB here:

Thanks to Gerwin Tamsma, Monika Hyatt, Frédérique Nijman, and their colleagues at the International Film Festival Rotterdam, we’re able to visit this venerable event, celebrating its fiftieth year! As with Venice and Vancouver, we’re happy to get online access to some outstanding films. We pass along the news to you here and in upcoming entries.

A dish best served cold?

Riders of Justice (2020).

Why is revenge so common as a driving force in film, fiction, and drama? Well, it sets up story action we like: search, mysteries, discovery, pursuit, confrontation. And it’s an impulse we find easy to understand. If you wrong me or mine, I’m likely to want payback.

As a high-school teacher once said to me, when I protested that the punishment wasn’t fair: “I don’t want to be fair. I want to be just.” In real life, Trump whines about unfairness, but he wouldn’t recognize justice if it met him head-on. Which it just might. Anyhow, in movies justice becomes our noblest excuse for the pleasures of vengeance.

Once our sympathy for the avenger is aroused, the storyteller has to decide how to treat the plot. Revenge shouldn’t be easy. It comes with a price. In Hong Kong films, revenge is usually the righteous settling of accounts.The price it demands is usually physical (wounds, maybe death) and social (the loss of friends cut down in the assault).

There’s another tradition of revenge drama that emphasizes the moral costs of revenge, the sense that it taints the avenger. You turn implacable, self-righteous, prone to error. Maybe the target isn’t really guilty? And can’t you forgive? And aren’t you turning obsessive? Can you sacrifice the other parts of your life to this mission? All of these questions haunt Anders Thomas Jensen’s seriocomic thriller Riders of Justice.

Markus, a stolid soldier, returns home when his wife is killed in a subway accident. His daughter Mathilde is traumatized. Markus’s stoic grief changes to rage when he is told by the statistician Otto, who survived the accident, that the crash was engineered by a gangster killing a rival. Markus’s icy pledge to vengeance sweeps up Otto, his two hacker friends, Mathilde, her boyfriend, and others.

In early days of this blog I wrote a lot about Danish films, which I’ve always admired. Many years ago Anders Thomas Jensen, director of Riders of Destiny, brought to our Wisconsin Film Festival The Green Butchers (2003). His scripts, for his own films and those directed by others, find a unique, tightly designed blend of drama and humor, with a penchant for showing the dumb side of male bonding (In China They Eat Dogs, 1999; Flickering Lights, 2000; Adam’s Apples, 2005)

Riders of Justice is in this vein, but it plays with larger ideas too. It starts and ends with a network-narrative premise (again, very Danish) emphasizing remote human connections. In between the characters come to grips with the role of chance in their lives. Scenes both serious and comic show them trying to reckon the reason behind their impulses. Even the numbermumbler Otto, who calculates probabilities of everything, admits to Mathilde that even the simplest event is impossible to explain through cause and effect.

You know that comfortable feeling you get at the start of a movie, when the story has hooked you, the characters command your sympathy (even when they make mistakes), and you realize that you’re in good hands for the next couple of hours? That was my response to Riders of Justice. Not least, it brings together for the umpteenth time two of the finest actors in world cinema, Mads Mikkelson (scary, in a trim Pentateuch beard) and Nikolaj Lie Kaas (sensitive, blinking behind wire-rims).

Riders of Justice has been purchased by Magnolia and is planned for a spring release.

Bolshevik nostalgia in 1.33

Dear Comrades! (2020)

“Dear Comrades!” is the salutation of a letter never sent. At a meeting of officials trying to handle a sudden strike, Lyudmila Syomina voiced a need for harsh reprisals for these traitors to the Soviet state. But after being called to write a letter and read it at a forum, she flees. She is torn by fear that her daughter has been captured or killed during the very violence she advocated.

Dear Comrades!, the latest and perhaps best film from the distinguished, pleasantly erratic director Andrei Konchalovsky, is set in Novocherkassk, 1962. The strike and the massacre were revealed in 1975 by Alexandr Solzhenitsyn and confirmed by an inquiry in 1992. Konchalovsky has undertaken a historical recreation, an examination of his parents’ postwar generation, and, I think, an oblique critique of authoritarianism. He seems equivocal about Putin’s “managed democracy” (though he’s not as big a booster as his brother Nikita Mikhalkov). In any case, we can’t help seeing the film as echoing the tyranny on display in Russia’s recent years, i.e., yesterday. Unlike the current demonstrators supporting Navalny, though, Konchalovsky’s characters yearn for well-run autocracy. After all, under Stalin, prices went down.

Classic Soviet fiction and film featured what’s come to be called a “conversion narrative.” In order to build any plot, you need drama. But you also have to conform to Bolshevik ideology. Some conflict can be supplied by villains (“traitors,” “wreckers”) seeking to undermine the Great Soviet Experiment. You can also create drama with characters who are ignorant of the true way, or uncertain about abandoning personal commitments and embracing the Party. So the plot can trace the gradual conversion of a character to sturdy Communist principles. This functions, in classic Socialist Realist storytelling, as psychology.

But Lyudmila is a hard-core Party loyalist. She benefits from the perks of office: a love affair with her superior in a nice apartment, the ability to jump the queue scrambling for food and matches, a paycheck that pays for a European-style coiffure. In exchange she mouths, with unblinking cobra severity, a strict adherence to policy. Yet her daughter Svetka has joined the strike and goes missing during the melée.Lyudmila’s search doesn’t easily dissolve her ideological tenacity. Like Mother Courage, Lyudmila stubbornly refuses to see what’s in front of her. She can’t believe that the KGB, not the Army, would plan a massacre that mowed down citizens.

Eventually we get glimpses of a de-conversion narrative. Lyudmila starts to sense that the current system is corrupt. “What am I supposed to believe in if not communism? Blow it all up and start again.” Yet what should replace it? The only alternative she knows. “I wish Stalin would come back.”

Konchalovsky has shot the film in lustrous, drypoint black and white, and in a silent-era ratio of 1.33:1. It’s one of the most elegantly composed and staged films I’ve seen in recent years; it could be studied just for its use of axial cuts. I’d almost call it “Straubian-Huilletian,” were it not so defiantly committed to the melodrama of a family crisis within social turmoil. But Dear Comrades! is far from your standard historical pageant. It’s at once austere and inventive.

Konchalovsky activates a great many motifs from classic Soviet film, treating them both for sly comedy and sharp drama. Satire on bureaucracy, another traditional source of plot developments, pervades the first half. Like Eisenstein in October, Konchalovsky can spare a shot mocking an empty conference table after the staff has fled.

Eisenstein is of course more grotesque: the panicked Mensheviks have leaped out of their furs, or been Raptured. The portrait of Khrushchev stands in for the Stalin picture hanging in every Socialist Realist office, parlor, bivouac, and meeting hall.

Konchalovsky stages the massacre of the strikers mostly through the heroine’s viewpoint. In place of the vast views supplied by Eisenstein in October (1928), the camera is tied down to a beauty shop.

In Soviet World War II films, the officials plan strategy in monumental headquarters (Front, 1943). The shabby offices of Konchalovsky’s provincials seem both cramped and hollow.

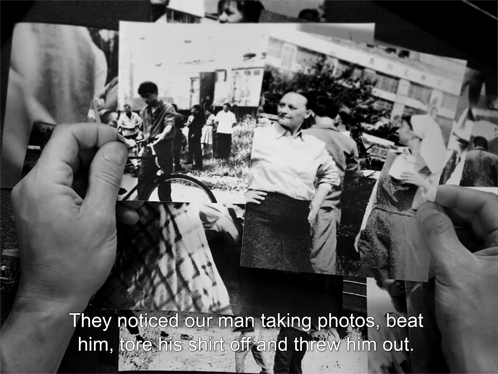

During the agitation and cleanup, Konchalovsky seems to me to rework specific images from Eisenstein’s Strike (1925). The hosing of blood from the streets seen in reflection echoes a shot of the factory in Strike. And in both, the police study the spies’ snapshots of strikers.

Dear Comrades! deserves all the attention it’s getting. Winner of this year’s Special Jury Prize at Venice, it has been picked up by Neon for US release. It’s also Russia’s submission for the Best International Feature Film Academy Award. It’s being streamed by several film festivals, notably Seattle’s, which offers it at a very reasonable price. But how I long to see it on the big screen.

I discuss some Danish network narratives in Chapter 7 of Poetics of Cinema and other examples in some entries. Katerina Clark has an excellent discussion of the conversion narrative in The Soviet Novel: History as Ritual (Indiana University Press, 2000). For a discussion of Socialist Realist film style, see this entry.

P.S. 4 Feburary 2021: Anders Thomas Jensen gives a very informative interview about Riders of Justice in Variety.

Riders of Justice (2020).