A modest extravagance: Four looks at Ozu

Monday | December 12, 2011 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

Ozu Yasujiro was born on 12 December 1903. He died on 12 December 1963.

For Donald Richie

The film comes to us calmly, not trying to overpower us or sneak into our good graces: just a simple story that seems to tell itself. First there is the daily routine. People arise, go to work or school, greet their acquaintances, labor at their desks, meet friends at a bar or teahouse or coffeehouse. Gradually, as one character mentions or meets another, the film carries us to that one. Then we discover another network of people, also linked through everyday action and little courtesies. This movie, it seems, could sidestep from group to group forever, eventually introducing us to the population of Japan.

A plot coalesces. Someone has fallen in love; someone is unhappy; someone must pass an exam; someone must get married to oblige a parent. Now everything that we have seen starts to crystallize into a drama. But the narrative flow is so unpredictable, even diffuse, that we can scarcely imagine what the climax could be. Sometimes the action is just put on hold, and an idyll shows a character recalling days of prior happiness, or imagining recalling today as a moment of consummate peace.

Suddenly a crisis descends. Someone we have come to care about falls ill, or decides not to marry, or decides to marry someone else, or betrays a friend. And soon we are truly overpowered, with a climax that seems completely contingent. Why this? Why now? The characters may ask along with us, but they resign themselves to things. The epilogue is like a farewell. These people who have come to matter to us drift away to an uncertain future that has a touch of stoic serenity.

All very straightforward, even artless. But that’s at first glance. Take a second look, and you see a subtle architecture. The distantly connected characters actually form a table of contrasts. For every wilful father, a tolerant one; for every cheerful daughter, a morose one; for each flirtatious boss a kindly widower. Long ago Donald Richie pointed out the importance of parallelism in Ozu: every person or circumstance is echoed or inverted elsewhere. Into these parallels Ozu inserts prefigurations of future action, motifs which connect characters (gestures, lines of dialogue, props like watches or cups), and daring ellipses which skip over important events. (Once he has us hooked, he can tease us by withholding what we want to see.) The ending and epilogue have the inevitability of the final lines of a grand poem. Look closely, and each Ozu film has a magnificently filigreed structure, and everything that will happen seems quietly destined from the start.

Third look: The simplicity of style. What could be easier than to shoot each scene with a master shot, followed by medium-shots? Each character, no matter how minor, gets his or her “single,” and a cut very seldom interrupts a line of dialogue. Every person gets a chance to speak, and people listen to each other. Nobody interrupts. A few establishing shots will link one scene with another. The camera is set low in nearly every shot, as if to eliminate any decision about where else it might be put, and it almost never moves. This, surely, is Moviemaking 101.

Look again, and it all becomes staggeringly complicated. Each shot is composed meticulously, down to the arrangement of food on the table. The compositions mirror each other uncannily: every medium-shot single puts the person’s face in the same part of the frame, so that the eyes of one character weirdly coincide with those of another. Indeed, Ozu’s bold play with graphic qualities—lines, masses, and color—from shot to shot is without peer in mainstream filmmaking. Contrary to what critics still say, the camera position doesn’t mimic a seated person’s view. It’s obstinately low even in train corridors and on sidewalks. What it does is subject the entire visible world to a precise patterning.

Thanks to this maniacally repeated framing, layers of space bristle with tantalizing possibilities. A humdrum space becomes charged with muted dynamism. Mundane bits of setting, like a red teakettle or a hanging sock-tree, come alive. And the intermediate spaces which link scenes often don’t establish the new scene’s locale very clearly. Instead, they hook one area to another by visual or auditory rhymes. The transitions also play games with our expectations. We may think we are going one place, but something, perhaps only the shadow of rippling water cast on a screen, swerves us to somewhere else. Just as Shakespeare’s dialogue can be read as pure poetry, the surface texture of these films would entrance us even if there were no story to follow.

Thanks to his apparently simple stories and easily grasped technique, Ozu has captivated and moved audiences for eighty years. But this humble artisan who compared himself to a tofu seller created a cinema of which no other director dreamed. Modest in effect yet extravagantly precise in execution, Ozu’s films are at once amusing, rapturous, and experimental. He tests his characters, his medium, his audience, and himself. His films show us how profound a genre- and star-driven studio picture can be. At the same time they open up a vast realm of purely cinematic possibilities. No filmmaker has come closer to perfection.

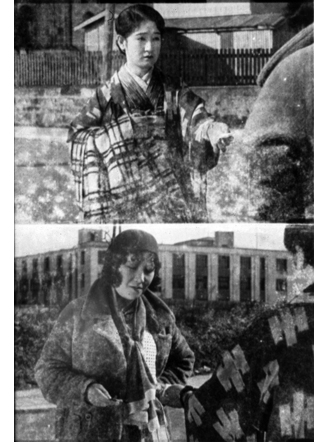

This essay originally appeared in slightly different form in Ozu Yasujiro: 100th Anniversary (Hong Kong International Film Festival, 2003). It is reprinted here by permission. Illustrations are from 35mm prints of Equinox Flower, Dragnet Girl, The Lady and the Beard, and Early Summer. DVD copies of Ozu films are available from the Criterion Collection in the US, the British Film Institute in the UK, and other sources elsewhere. A site showcasing all things Ozu is Ozu-san.com. My book, Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, is out of print in hard copy, but a free pdf file is available for download here.