Preserving two masters

Wednesday | December 10, 2008 open printable version

open printable version

Kristin here—

This past weekend the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Cinematheque played host to Stefan Drössler, the head of the Filmmuseum in Munich. The Filmmuseum is a major force in film restoration, and on Saturday we were treated to a much longer print of Ernst Lubitsch’s 1922 epic, Das Weib des Pharao, than had previously been available.

Lubitsch on the verge of going Hollywood

This restoration came too late for me to see it before my book on the director’s silent features, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (2005), was published. Not that that was a problem. I was dealing largely with style in that book, and the old version furnished plenty of examples to support my point. I argued that Das Weib was a turning point in Lubitsch’s career. It was the first film he made after the German ban on film imports was lifted and he was able to see recent Hollywood films for the first time since the war. It was also made with American financing, offering him the chance to work with American cameras and lighting equipment—an opportunity that gave him much more stylistic flexibility.

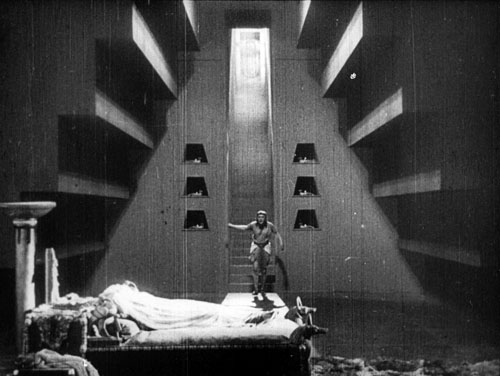

As a result, Lubitsch goes from using mostly flat, frontal light to employing the recently developed three-point lighting system. The frame above shows a very Hollywood-style lighting layout, and that’s fairly typical of this film.

Of course, it was a treat to see the film with so much new material. As I recall, the old version ran about 40 minutes, while this one is 110 minutes. There’s still footage missing, replaced in this print by still photographs and summary intertitles. Still, the plot makes a lot more sense. For the most part, the visual quality is better. The restoration depended on footage supplied by a number of archives, however, and the occasional inferior shot indicates that a less well-preserved print had to be used as source material.

The story, set in ancient Egypt, is rather clichéd and the characters little more than ciphers. The interest lies mainly in the style and the majestic scale of the production. Given a much larger budget than usual and a longer shooting schedule, Lubitsch distinctly outdid his own earlier historical dramas, Madame Dubarry (1919) and Anna Boleyn (1921). Reportedly 8000 extras participated in the battle and crowd scenes, and the sets were erected on a colossal scale. Designer Ernst Stern was a serious Egyptology buff, and despite occasional lapses, the sets, props, and hieroglyphs are a lot more authentic than those in most movies set in this era. The film’s cast also includes a remarkable line-up of some of the most prominent actors of its day: Paul Wegener, Albert Bassermann, Harry Liedtke, and Emil Jannings (above).

Perhaps, as happened recently with Metropolis, a new, complete version of Das Weib des Pharao will someday be found. As Stefan said, however, more footage from Lubitsch’s last German film, Die Flamme (1922) would be even more welcome. An intimate drama starring Pola Negri, it survives in only one tantalizing reel. That footage reveals the director’s rapidly growing grasp of continuity editing as well as three-point lighting. Clearly he was ready to make the move to Hollywood and to even further development as a filmmaker. (My own dream film to be rediscovered would be Kiss Me Again, a completely lost 1925 Warner Bros. feature. Odds are pretty good that the one film Lubitsch made between The Marriage Circle and Lady Windermere’s Fan would be a masterpiece.)

A new Walter Ruttmann DVD

Seeing a 35mm print of such a restoration well projected is the ideal, of course, especially with an expert pianist like the Cinematheque’s David Drazin providing the accompaniment. For those who can’t get to such screenings or who want to study its restorations, the Filmmuseum also makes many of its restorations, as well as art and avant-garde films, available on DVD.

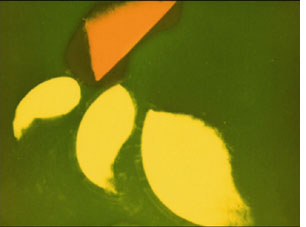

Stefan gave us a copy of one of the latest of these, a Walther (or Walter, as he sometimes spelled it) Ruttmann disc entitled “Berlin, die Sinfonie der Grossstadt & Melodie der Welt.” Actually, that’s a bit misleading, since the DVD actually contains a great deal more than those two features. All of Ruttmann’s surviving films up to 1931 are included. He was on the forefront of abstract animation, and the full series, Lichtspiel Opus I (1921), Opus II (1922), Opus III (1924), and Opus IV (1925), is included here. All have musical accompaniment, including Hanns Eisler’s 1927 score for Opus III. (That’s a frame from Opus I on the left.)

Stefan gave us a copy of one of the latest of these, a Walther (or Walter, as he sometimes spelled it) Ruttmann disc entitled “Berlin, die Sinfonie der Grossstadt & Melodie der Welt.” Actually, that’s a bit misleading, since the DVD actually contains a great deal more than those two features. All of Ruttmann’s surviving films up to 1931 are included. He was on the forefront of abstract animation, and the full series, Lichtspiel Opus I (1921), Opus II (1922), Opus III (1924), and Opus IV (1925), is included here. All have musical accompaniment, including Hanns Eisler’s 1927 score for Opus III. (That’s a frame from Opus I on the left.)

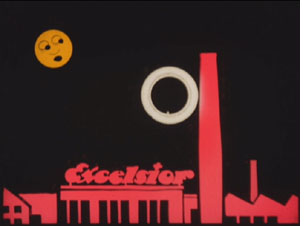

In addition, there’s a group of charming advertising films, all animated. These tend to be abstract and only bring in the product near the end. In doing the short for Excelsior tires, however, Ruttmann obviously found a round, nearly abstract shape that he could play with. A  tire rolls around in a flat landscape, having adventures that include going up and down the Excelsior factory smokestack and being threatened by spiky shapes that fail to puncture it.

tire rolls around in a flat landscape, having adventures that include going up and down the Excelsior factory smokestack and being threatened by spiky shapes that fail to puncture it.

Apart from these shorts, the two-disc set includes as bonuses a series of 22 paintings and drawings by Ruttmann, a number of texts by and about him, photographs, and so on. There’s also a CD-ROM section with additional documentation, plus a small booklet.

The two features are restorations. If you’ve only seen Berlin on a mediocre 16mm copy, this version should be a revelation. Its visual quality is gorgeous, and it has the original Edmund Meisel score, well played and well synched. The “symphony” aspect of the film makes a lot more sense with this accompaniment.

Melodie der Welt is credited with being the first German sound feature. It’s a lot simpler than Berlin. Financed  by a steamship company, it purports to follow a sailor on a huge liner around the world to exotic countries. Ruttmann takes footage from English, Greek, Japanese, and other cultures and cuts them together by topic to emphasize the similarities. Religious ceremonies are compared, military exercises intercut, children’s games assembled into a montage, people playing music (right), and so on. The laudable goal is to make customs of “exotic” peoples seem less remote and strange by showing them doing things that are not all that different from what Europeans do. A pity this was happening just before the Nazis sought to eradicate such notions of universal humanity.

by a steamship company, it purports to follow a sailor on a huge liner around the world to exotic countries. Ruttmann takes footage from English, Greek, Japanese, and other cultures and cuts them together by topic to emphasize the similarities. Religious ceremonies are compared, military exercises intercut, children’s games assembled into a montage, people playing music (right), and so on. The laudable goal is to make customs of “exotic” peoples seem less remote and strange by showing them doing things that are not all that different from what Europeans do. A pity this was happening just before the Nazis sought to eradicate such notions of universal humanity.

This set is just about ideal as a presentation of Ruttmann’s work in this period. I hope that someday a print of his 1933 fiction feature, Acciaio, will become available. It was made in Italy, and although it has been many years since I’ve seen it, I remember it as a very good film with spectacular documentary-style scenes shot in a steel mill—and as a forerunner of Neorealism.

David and I look forward to seeing Stefan at next summer’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna and to whatever new treasures he and his fellow archivists have restored.