Archive for January 2007

From Hollywood to Atlanta to us

DB here:

Some day Ph. D. students will be writing dissertations on the contribution of Turner Classic Movies to US culture. I’d argue that Ted’s baby is as important to our collective sense of cinema history as the establishment of the Museum of Modern Art Film Department was.

As a movie fan, I’m overwhelmed by the chance to see so many of my favorites for the cost of monthly cable. As a film researcher, I find myself feeling as if a film archive dumped a dozen movies on my front lawn every morning. In 1990, my colleagues and I would’ve killed for the opportunity to see this stuff, and now it’s whizzed to us at home. “Seven Brides for Seven Brothers again?” some of us sigh. We are so spoiled.

To refresh his core MGM-RKO-WB titles, Turner showcases items from Columbia, Paramount, Goldwyn, and other studios. The channel has become an eternal college course in cinema, with no exams or papers and all viewers happy to earn a perpetual Incomplete.

To refresh his core MGM-RKO-WB titles, Turner showcases items from Columbia, Paramount, Goldwyn, and other studios. The channel has become an eternal college course in cinema, with no exams or papers and all viewers happy to earn a perpetual Incomplete.

Why mention TCM now? Because I’m especially wrought up by what’s on offer over the waning days of January. Every day boasts many classics, so I’ll mostly skip mentioning all the fine standbys that they’re running. Here are more offbeat things I’m up for, most of which I haven’t seen.

Overturning centuries of Western tradition, TCM defines a new day as starting at 6:00 AM. Sounds reasonable to me. But check for local playing times.

Jan 21: Stolen Moments (1920): I don’t get Rudolph Valentino’s appeal, but any film from this era demands a look.

Munchhausen (1943) A textbook classic from the Nazi cinema.

Jan. 22: The Legend of Lylah Clare (1968): Trashy premise + Kim Novak + Robert Aldrich = must-see.

Jan. 23: A cornucopia. I’ll just keep the recorder going all day for:

The Black Book (1949): As oddball a film as Anthony Mann ever made, with John Alton’s pitch-black scenes turning the French Revolution into a noir nightmare. Forget the commercial DVD, evidently ripped from a 16mm print; the TCM version should look better.

Gangster Story (1959): Walter Matthau starred and directed this NYC low-budgeter.

The Guilty Generation (1931): From Rowland V. Lee, endless supplier of B’s.

The Criminal Code (1931): Excellent Hawks with Karloff. Bogdanovich paid tribute to this in Targets.

A string of Boston Blackie films, from 1941-1942: I remember this popular B series from TV syndication in my childhood. Fast-paced and punchy, with direction by Robert Florey, Edward Dmytryk, Michael Gordon, and the prolific Lew Landers.

Angels over Broadway (1940; on right): Mostly shot in one nightclub set (in the Astoria studio?), a murky drama signed by Ben Hecht and Lee Garmes. Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Thomas Mitchell, and a young Rita Hayworth fill out sober long takes.

Angels over Broadway (1940; on right): Mostly shot in one nightclub set (in the Astoria studio?), a murky drama signed by Ben Hecht and Lee Garmes. Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Thomas Mitchell, and a young Rita Hayworth fill out sober long takes.

The King Steps Out (1936): Hard-to-see von Sternberg.

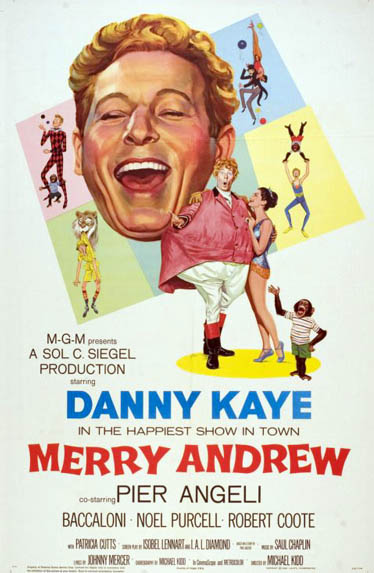

Jan. 24: Of course you’ll watch La Strada, Detective Story, The Big Carnival, etc. if you haven’t seen them. Me, I’m poised to record Merry Andrew (1958), a CinemaScope vehicle featuring Danny Kaye as an Oxbridge archaeologist. The film contains another unexorcizable ghost from my childhood, the song “Everything is Tickety-Boo.” What’s tickety-boo? Canadians know.

Jan. 25: Lots of prime stuff, including Experiment in Terror, Anatomy of a Murder, Dead Heat on a Merry-Go-Round, The Caddy, and several classic MGM musicals.

Jan. 26: A day devoted mostly Paul Newman and Paris, but there’s also:

The Killer Is Loose (1956): Boetticher. Say no more.

To Paris with Love (1955): Robert Hamer, director of the Ealing classic Kind Hearts and Coronets, gave us this, starring Alec Guinness, one of cinema’s finest and most modest actors.

A drive-in horror double bill courtesy William Beaudine: Billy the Kid vs. Dracula (1966) and Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter (1966).

Jan. 27: Of course you’ll see, if you haven’t, Gunga Din, The Yearling, The Naked Spur, The Manchurian Candidate (kinda overrated, methinks), The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (kinda underrated), The Quiet American, etc. But there’s also:

The Last of the Mohicans (1935): This, rather close to Michael Mann’s later version, I remember as being pretty solid.

A Bullet for Joey (1955): Edward G and George Raft in their sunset years; can it be bad? Okay, it can, but I’m still going to check it out.

Jan. 28: Among much good stuff, including the still poignant Umbrellas of Cherbourg, I’ll be targeting Dragnet (1954), a nifty, seldom seen feature by that unique genius Jack Webb. How often do we get an ashtray’s-eye-view of a scene? Does this cablecast portend a DVD release?

Jan. 28: Among much good stuff, including the still poignant Umbrellas of Cherbourg, I’ll be targeting Dragnet (1954), a nifty, seldom seen feature by that unique genius Jack Webb. How often do we get an ashtray’s-eye-view of a scene? Does this cablecast portend a DVD release?

Jan. 29: It’s teen dance music till prime time: Bop Girl, Rock around the Clock, Don’t Knock the Rock, Don’t Knock the Twist, Don’t Rock the Twist, Don’t Twist My Rock, etc. Might just as well keep the recorder rolling… and rocking!

Today’s outstanding piece of esoterica is The Show (1927). Every year or so I’ve been writing TCM to ask them to play this strange item from the agreeably warped Tod Browning. Let’s just say that John Gilbert plays Cock Robin and Renee Adoree plays Salome, with Lionel Barrymore chewing the scenery as the villain. Other attractions include cuckoldry, decapitation, and murderous iguanas. With a new score from TCM’s highly laudable Young Composers competition.

Jan. 30: Of course you’ve seen Ford’s stunning Arrowsmith, Pressburger’s Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, This Happy Breed, Shane, His Girl Friday, etc. But don’t forget:

The Clairvoyant (1935): the relentlessly prolific Maurice Elvey, doyen of Brit good taste, directs Claude Rains (ditto) and Fay Wray.

Strike Me Pink (1936): Eddie Cantor isn’t for all tastes, but I want to give this one a chance.

Raffles (1939): I’m a sucker for gentleman-thief stories, and with Gregg Toland as cinematographer, Sam Wood may indulge his Gothic streak, so memorable in Our Town and Kings Row.

Jan. 31: Not as strong a day as yesterday, but I’ll be checking on This Could Be the Night (1957), helmed, as they say, by Robert Wise and starring the radiant Jean Simmons (another adolescent fascination of mine), and Mitchell Liesen’s The Mating Season (1950), written by Charles Brackett and starring the fascinatingly blank Gene Tierney.

February, devoted to Oscar pictures, doesn’t contain so many marginal items, but still it’s a cornucopia of outstanding movies.

Controversial as he is, Ted Turner has proven a generous mogul, both politically and cinematically. Forget colorization! That was a bogus issue, and anyhow, for every colorized title a spanking fine-grain positive was made for archival preservation. Turner has done more than any single person to sustain and publicize the American film heritage, and he’s made it available to everyone within reach of cable. You can read more about Ted in Ken Auletta’s brisk and chatty biography.

Dorothy’s rainbow comes to earth at TCM. Watch regularly. Check the website for extra stuff, and browse the 150,000 film database. Buy the monthly program guide; it’s only twelve bucks. While you soak up the pleasure, pause to pity the cinephiles overseas. Their version of TCM, hedged by rights holder restrictions, offers mere crumbs from our bursting banquet table.

PS: Since I first posted this, film historian Doug Gomery has pointed out that Turner hasn’t controlled TCM in 12 years, but both Time-Warner bosses Gerry Levin and Dick Parsons have kept it going. We owe them thanks for refusing to ‘AMC’ it with commercial breaks and dopey gimmicks. Fortunately it makes money for TW. Long may TCM prosper.

PPS as of 23 Jan.: Lee Tsiantis of the Turner Entertainment Group adds that credit also belongs to Jeff Bewkes, who among other duties oversees the channel. So a big thanks to him as well.

Updates and outtakes (in which we try, perhaps in vain, to catch up with ourselves)

Exiled

Kristin writes:

“The Hobbit Film: New Developments” (January 13, 2007)

In this entry I discussed Bob Shaye’s recent claim that Peter Jackson would never get a chance to direct The Hobbit for New Line. I mentioned that one of the factors involved in the negotiations about who would direct is that the production rights will eventually revert to producer Saul Zaentz. I didn’t know the length of the option on those rights, which New Line currently holds. The January issue of the fantasy/sci fic magazine Locus says that the rights will revert to Zaentz in 2009.

Zaentz had owned the rights since the mid-1970s and sold them to Miramax in early 1997. Miramax had the two-film version of The Lord of the Rings in pre-production for about 18 months and then sold the rights to New Line in August of 1998. I don’t know what the source of Locus’ information is, but a twelve-month option would seem pretty plausible.

If that information is correct, New Line only has about two years to get the actual making of the film underway. It takes years for any big film to lumber into production in Hollywood these days, so the studio doesn’t have a lot of room to wiggle.

“By Annie Standards” (December 14, 2006)

Here I talked about methods for publicizing animated features. One way, I suggested, would be to foster audience interest in the various animation awards other than the Oscars. I remarked, “Under Academy rules, only three animated features can be nominated in any year unless sixteen or more such features are released that year. Then the number of nominations jumps to five, but so far that hasn’t happened. It may finally happen this year, if all sixteen features currently under consideration qualify under Academy rules.”

Close, but not close enough. On January 11, Variety announced that one film, Luc Besson’s Arthur and the Invisibles, had been disqualified as an animated feature. To qualify, a film must have at least 75% animated footage, and Arthur has too much live action.

With the number of qualifying features down to fifteen, only three can be nominated. Probably Cars will win, as I predicted in the original entry. It just won the Golden Globe in the newly established Animated Film category.

“Snakes, No, Borat, Yes: Not All Internet Publicity Is the Same” (January 7, 2007)

Here I suggested some reasons why Snakes on a Plane failed at the box office and Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan succeeded, despite the fact that both garnered considerable fan-generated publicity on the internet. I mentioned that Sacha Baren Cohen had appeared on talk shows in character as Borat rather than in persona proper: “Each appearance by “Borat,” supposedly there to talk about the film, ended up being a hilarious performance by Cohen, ad-libbing on everything around him—the chairs, the coffee mugs, the cameras, the audience. Spectators ended up with one impression about the film: it was about this incredibly funny guy doing incredibly funny things.”

Trying to correct the widespread assumption that Borat was an improvised film, the January 8-14 issue of Variety ran a story about how Cohen worked with three scriptwriters, Peter Baynham, Dan Mazer, and Anthony “Ant” Hines: “The scribes even concoct Cohen’s dialogue for his promo appearances on ‘The Tonight Show’ and ‘Live With Regis and Kelly.’” Although Cohen presumably ad-libs to meet specific circumstances of each talk show, the publicity appearances are even more controlled by Cohen than I had assumed.

I also remarked that it is difficult to judge the degree to which the film manipulated the scenes of Borat’s encounters with real people. Especially in terms of editing and sound techniques, there was clearly much opportunity for this manipulation. The same Variety story goes on to say, “Much of the script had to be altered depending on how situations unravel. This means the writers ultimately end up producing the equivalent of multiple scripts, much of which ends up on the cutting room floor.” I’m not sure how chunks of scripts can end up on the cutting-room floor, but the point is that the filmmakers were carefully stitching the “documentary” scenes together on the script level and presumably would do so through stylistic means as well.

David writes:

Back to the Hotel

The Uchoten Hotel (aka Suite Dreams, blogged here) has acquired yet another English-language title: Hotel Avanti. It made it to #93 on Variety‘s list of the world’s 100 top-grossing films, with $51 million box office in Japan and none yet recorded overseas.

Speaking of Variety‘s list, the highest-grossing non-English language item turns out to be Bong Joon-ho’s Korean hit The Host (#59 at $84 million), due out in the US any month now. Only ten non-English-speaking films made the top 100, and of those, three were European (including Volver) but all the rest were Asian: Chinese (Fearless), Korean (The Host and King and Clown), and Japanese (Tales from Earthsea, Umizaru 2 Limit of Love, Hotel Avanti, and Japan Sinks–no rude remarks, please).

The entire list is in the 15-21 January hard copy of Variety, p. 15, but evidently it isn’t yet available on the paper’s site.

More on Johnnie To

In an earlier blog I praised Johnnie To as a director who shot and cut PTU smoothly and crisply. I waited through the fall, hoping somehow to see To’s latest, Exiled, on the big screen at one festival or another. No such luck. So last night I broke down and watched the DVD. Making full use of the widescreen format, To shows that classic technique can be at once rigorous and imaginative.

Exiled was more visually engaging than any US film I can recall last year, including Miami Vice. It immediately became my Best Film of 2006 That I Saw in 2007. (Runner-up: Children of Men.) I visited Milkyway while the film was being shot, and I hope to blog about the result in a future entry.

At Large on the Internets

On this very site, I’ve posted a new essay on action movies.

Annie Frisbie interviewed me for the Zoom-In podcast here. Annie is also blogging/reviewing Sundance films here.

Fox Independent visited Madison and posted videos on its site. The setup and the interview with filmmaker and teacher Erik Gunneson are here. An interview with me is here.

Shot-consciousness

Most professional critics seem uninterested in the film shot as a shot. They might notice when the images call flagrant attention to themselves, as in Zhang Yimou’s recent films, or in those protracted walk-and-talk Steadicam takes. On the whole, though, reviewers prefer to talk about plot and acting.

Granted, it’s hard to be aware of shots, especially if you get engrossed in the story. But if we want to be fully alert to how movies work on us, we should keep our eyes open. Back in 1968, I read The Moving Image by Robert Gessner, one of the first teachers of cinema studies in the US. There Gessner offered a sturdy piece of advice: Be shot-conscious.

About twenty years later, trying to be shot-conscious and all, I started to notice a certain type of image becoming more common, especially in European and Asian films. Then it started to appear in US films as well, especially indie items. Now it’s very common everywhere, though it’s still not the predominant sort of shot.

Here’s a fairly early example, from R. W. Fassbinder’s Katzelmacher (1969).

How to characterize it? The camera stands perpendicular to a rear surface, usually a wall. The characters are strung across the frame like clothes on a line. Sometimes they’re facing us, so the image looks like people in a police lineup. Sometimes the figures are in profile, usually for the sake of conversation, but just as often they talk while facing front.

Sometimes the shots are taken from fairly close, at other times the characters are dwarfed by the surroundings. In either case, this sort of framing avoids lining them up along receding diagonals. When there is a vanishing point, it tends to be in the center. If the characters are set up in depth, they tend to occupy parallel rows.

Linda Linda Linda (2005)

No one to my knowledge had noticed this sort of shot, let alone named it. I started to call it mug-shot framing, but I found that art historian Heinrich Wölfflin had called it planar or planimetric composition. I went with “planimetric” because that term suggests the rectangular geometry so often seen in these shots.

What’s striking is that such imagery is quite rare before, say, 1960. We can find some examples, principally in silent comedy and especially the films of Buster Keaton (himself a pretty geometrical director). But in the 1960s, we find Antonioni and Godard using planimetric shots fairly often.

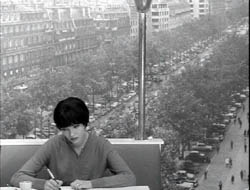

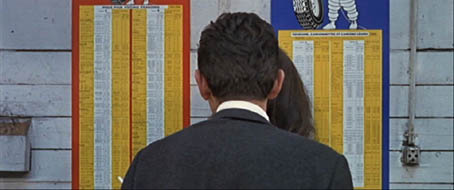

Vivre sa vie (1962)

This image design became more popular from the 1970s onward. Why? In On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light, I tried to trace out some sources and functions of it. Briefly, I think that the planimetric shot emerged from filmmakers’ growing reliance on long lenses, which tend to create a flatter-looking, more cardboardy space than wide-angle lenses do. A telephoto shot makes an image seem less voluminous. It seems to be made of slices of space lined up one behind another.

Filmmakers began using long lenses for many purposes, often because of the demands of filming on location. And some directors realized that long-lens optics offered fresh resources for staging and composition.

For instance, the planimetric scheme is well-suited to a “painterly” or strongly pictorial approach to cinema. In Figures, I discuss two directors who made planimetric shots central to their style. Hou Hsiao-hsien saw very deeply into the possibilities of these shots; I think he learned it from his early skill at shooting on the street with long lenses. You can find more about that here. By contrast, Angelopoulos used the planimetric image in conjunction with architecture and landscape to create a sort of de-dramatized spectacle, a spare grandeur reminiscent of icon painting.

The Suspended Step of the Stork (1991)

The functions of the planimetric image can vary a lot. Often it’s used to suggest stasis and passivity, as in the Katzelmacher instance. Kitano Takeshi picks up on this sense of torpor in certain shots of Sonatine, which suggests that being a gangster means having a lot of time to kill just hanging out.

Kitano’s use of the image also suggests a kind of childish simplicity or naïve cinema. Unlike Hou and Angelopoulos, Kitano uses the planimetric schema as if it were just the most basic way to film anything. Line up your characters and shoot ’em, as if they were figures in South Park or Cathy.

Kitano has compared himself to the kamishibai man, the street performer who narrates stories for children by flipping through illustrated cards, and Kitano’s paintings are more sophisticated, often planimetric versions of those drawings.

The planimetric schema can suggest something more oppressive too. That’s one purpose, I think, of certain shots in Terence Davies’ remarkable Distant Voices, Still Lives. The film’s stylistic system is quite rigorous in its use of straight-on compositions, and it’s worth more attention than I can give it here. For now I’ll just mention that the first part presents tableaux of unhappiness that suggest bleak family portraits.

Here and more generally, the planimetric image often carries the connotations of a posed photograph. Possibly the dry, rectilinear imagery of Walker Evans and the wide-eyed attitudes of Diane Arbus’s portraits have contributed to the sense of stiff ceremony such shots sometimes have.

Walker Evans, Roadside Stand Near Birmingham (1936)

Asian filmmakers combined the planimetric image with very long takes. In Kore-eda Hirokazu’s Maborosi, Yumiko’s husband comes home drunk, a slip from his usual reliable habits. She has just been remembering her previous husband, dead in a bike accident. The rocklike stability of the shot, aided by the grid backing the characters, throws every gesture into relief, particularly when Yumiko’s face lifts slightly into and out of shadow in the course of the action.

In the 1990s US indie filmmakers adapted this staging strategy. In Safe, Todd Haynes uses it to suggest the hard-edged sterility of the wife’s suburban life, which surrounds her with cubical furniture.

Wes Anderson used the image schema occasionally in Bottle Rocket but came to rely on it more and more. (He tended to use wide-angle rather than longer lenses, though; note the bulging effect in the Life Aquatic shot below.)

For Anderson, as for Keaton and Kitano, the static, geometrical frame can evoke a deadpan comic quality. This comes out as well in Jared Hess’s Napoleon Dynamite.

Initially, this scheme also helped filmmakers distinguish their work from Hollywood. Mainstream American films tend to film players in 3/4 views, except for certain situations, such as a theatrical performance or a scene showing a mammoth image display.

V for Vendetta (2005)

Some American directors seem to have used the planimetric shot decoratively, as a nifty one-off touch, as here in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang.

Many overseas directors who rely on this schema adjust their cutting accordingly. In Figures I called it compass-point editing. The usual tactic is to follow one planimetric shot with a reverse shot that’s also planimetric. In the first four shots of Kitano’s A Scene at the Sea, the camera angle switches either 180 degrees or zero degrees.

When I asked Kitano why he cut this way, he gestured toward me, then at himself. “When we are speaking, this is the way we look toward each other. It’s the most natural way to show a conversation.” Apparently this is why over-the-shoulder shots are pretty rare in Kitano’s films.

Planimetric shot/ reverse shot is seldom used in Hollywood films, and it seems to be reserved for certain confrontational situations, or institutional scenes (e.g., doctor/ patient conversations). It can sometimes suggest an unnerving or unnatural encounter, as in I, Robot. The detective Spooner is calling on his old friend Dr. Lanning, and their dialogue is shot in to-camera medium-shots.

At the climax of the conversation, the camera takes up a 3/4 position and arcs around Lanning, revealing him to be only a hologram, presenting his dying message to Spooner. The planimetric image is motivated as suitable for a flat, virtual presence.

Proyas has cleverly prepared us for this subterfuge by ending the previous scene with an unremarkable planimetric framing on Spooner as elevator doors close on him.

This shot leads directly to the initial shot of Dr. Lanning above, apparently addressing us, in a sort of shot/ reverse shot cut across two scenes.

As we might expect, Godard, who helped disseminate the schema, is all up for upsetting it, in Vivre sa vie and Made in USA. The first shot below teases us to read the flat background as a high-angle vista; the second carries the idea of a conversation in a planimetric frame to a beautiful absurdity.

My quick survey doesn’t exhaust the various forms and uses of this strategy. I just wanted to show how shot-consciousness can lead us to notice when filmmakers take up new pictorial tools and modify them for particular purposes.

The Hobbit Film: New Developments

(Photograph by Emma Abraham)

Kristin here–

Behind closed doors, major negotiations and offers concerning the film of The Hobbit are presumably passing back and forth. The glimpses afforded the public via the key players suggest a stormy process. One of those players, Bob Shaye, is president of New Line Cinema, which he founded in 1967 and has headed ever since. He was the one who in 1998 took on the Lord of the Rings project and decided to make the film in three parts.

On January 10th, a report posted on the internet quoted Shaye as declaring that Peter Jackson will never get to direct The Hobbit for New Line.

That’s quite a leap from the situation as it was back on October 2, when I posted my first blog on the subject. At that point MGM (which owns the distribution rights for The Hobbit) had just announced that it and New Line would co-produce the film. The studio’s spokesperson mentioned Jackson as the director of choice.

The big concern among fans then was whether Jackson, who had been announcing new producing and directing projects right and left, would have time in his schedule to tackle such a major project—especially given that MGM suggested that the film might be made in two parts.

Having written a book, The Frodo Franchise, with the cooperation of the filmmakers, I weighed in on the logistics of all this. As I said at the time, since finishing my research in New Zealand in 2004, I have not had direct contact with Jackson or the others privy to the negotiations concerning his subsequent projects. I simply offered an educated opinion on the situation and why Jackson might well be able to fit The Hobbit into his schedule. The recent major developments suggest that it’s time again to provide some additional context.

One fundamental bit of backstory on the whole issue of who will direct The Hobbit dates back to early 2005, when Jackson filed a lawsuit against New Line. The entire complaint, published March 25, 2005, is available online. It makes a number of claims concerning New Line, including ways in which the exploitation of The Fellowship of the Ring and its licenses was dealt with. Primarily it alleges that New Line did not “properly account, calculate and pay to Wingnut its share of the profits” (i.e., from theatrical distribution) and didn’t “properly allocate license fees paid with respect to packages of defendants’ film properties that include the Film.” I take it that the latter refers to the DVDs. Jackson insists that the lawsuit does not demand a set amount of money but simply a proper auditing of the money from the Fellowship release, licensed goods, and DVD.

On November 19, 2006, Jackson and producing/writing partner Fran Walsh posted a letter on TheOneRing.net. In essence they said that they had been approached by New Line to make The Hobbit, with the implication that the lawsuit would be settled if they accepted. Jackson and Walsh countered by saying that they would not link the film to the lawsuit. New Line decided to find another director, and Jackson and Walsh told the fans they would not be making The Hobbit.

There followed a storm of protest on the Internet. MGM pointed out that it still wanted Jackson to direct The Hobbit. Saul Zaentz, who had sold the production rights back in 1997, said he hoped that Jackson would direct.

At that point, an observer might reasonably assume that the participants were drawing lines in the sand. Jackson clearly wanted to direct The Hobbit, but he had plenty of other projects in the pipeline and did not need to chase this one. Perhaps he saw the November 19 announcement as a way to pressure New Line into settling the lawsuit. Perhaps New Line suspected that they would end up owing Wingnut a great deal of money if the audit occurred.

There the situation evidently stood for nearly two months, with no public signs of either side budging. Then, in a brief interview with Sci Fi Wire (the news service of the Sci Fi Channel’s website) posted on January 5, Shaye declared: “I do not want to make a movie with somebody who is suing me. It will never happen during my watch.” Shaye declared that Jackson had so far been paid “a quarter of a billion dollars,” implying that suing for more was greedy and again emphasizing: “He will never make any movie with New Line Cinema again while I’m still working for the company.” Wingnut’s deal with New Line for producing, directing, and writing LOTR involved flat fees for Jackson and Walsh as well as an undisclosed percentage of the income and bonuses if the film hit certain box-office levels.

Later the same day, Jackson responded on Ain’t It Cool News, briefly reiterating in measured terms the reasons for the lawsuit and expressing regret at Shaye’s statement.

Where do things stand now?

According to the November 19 letter, Mark Ordesky (Executive Producer of LOTR) was the one who called Jackson about The Hobbit. In the course of it he mentioned that the option on the production rights for the novel would eventually revert to Saul Zaentz. Hence New Line’s need for speed and its decision to seek another director. Rumors that Sam Raimi had been approached circulated, though no evidence for that has surfaced.

It is customary for production options on a literary property to be sold for a limited time. Given that we just passed the tenth anniversary of Zaentz’s sale of the rights, obviously that wasn’t the period. Who knows how many years are left? Is New Line using that issue as a way to put pressure on Jackson? Quite possibly.

New Line must realize that Jackson’s name adds tens of millions of dollars in value to The Hobbit as a film property. Its executives know that fans are up in arms about all this. A poll taken by TheOneRing.net beginning December 18 asked whether fans would go see The Hobbit if it were directed by someone other than Jackson. “Definitely No—No way without PJ!” garnered 62.5% of the votes; “Not likely—I can’t imagine another team involved” drew 14.1%; “Very likely—Can’t wait for any live-action Hobbit film!” 10.3%; “Don’t know—Depends on who directs,” 10.3%; “Likely—It is time for some fresh creative juices,” 2.6%. 10,143 people voted, thousands higher than in other recent TORN polls.

Clearly indignant fans would be more likely to participate in such a poll than would non-indignant ones. And no doubt many of the fans would change their minds and go to The Hobbit as directed by someone else. Still, considerable resentment would linger and be volubly expressed right up to the time of the film’s release. Any director approached by New Line would doubtless be aware that he (or possibly she) would be swimming upstream against a flood of fan opprobrium. Would any major director agree to it? Some of the likeliest candidates are also friends of Jackson’s.

Another relevant factor that New Line would have to consider is whether any of the actors would return to work under a different director. Jackson creates a fierce loyalty among the people he works with. During the making and release of LOTR, the actors rallied behind him during a number of disputes with the studio.

On November 22, Ian McKellen put the Jackson/Walsh letter on his series, “E-Post: The Lord of the Rings” and added a comment: “The LOTR fans are already expressing a sense of betrayal. On my own account, I am very sad as I should have relished re-visiting Middle Earth with Peter again as team-leader. It’s hard to imagine any other director matching his achievement in Tolkien country. We will have to await developments but being an optimist I am hoping that New Line, MGM and Wingnut can settle outstanding problems so that the long expected ‘Hobbit’ is filmed sooner rather than later.”

Of course not all that many characters in LOTR appear in The Hobbit. Gandalf is the crucial one, and McKellen strongly implies that he wouldn’t return under another director. Elrond appears in two brief episodes. (The general opinion is that Ian Holm would be too old to play Bilbo, who is 50 in the novel.) Jackson has mentioned the possibility of showing the White Council meeting, which is only mentioned in the book, and that would involve at least Galadriel and Saruman. It is quite possible that the relevant actors would refuse to return unless Jackson helms the film. Important crew members might do the same.

The possibility of the rights reverting to Zaentz remains vague unless someone reveals the length of New Line’s option. I suspect that Zaentz would like nothing better than to regain those rights. He is a formidable producer himself, having three Best Picture Oscars on his mantel (One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Amadeus, and The English Patient). He got a very significant cut of the gross income from Lord of the Rings, as well as loads of money from the licensed products. By producing The Hobbit himself, he would probably receive a considerably higher cut.

He also wouldn’t have to depend on New Line’s accounting practices. Zaentz himself sued New Line over his share of the box-office take for LOTR. His suit alleged that although his contract gave him a cut of the gross theatrical income, New Line had calculated his share on net revenues, paying him $168 million. The trial was set to commence on July 19, 2005, but New Line entered into negotiations and settled with Zaentz in August, giving him an additional $20 million.

Lawsuits like this aren’t uncommon in Hollywood, so the Jackson/Walsh and Zaentz claims against New Line are not extraordinary events. The Zaentz case does, however, give some indication of the kinds of money involved. It is notable that New Line has caved as a result of a lawsuit somewhat similar to the one now in contention.

Presumably Jackson and Walsh’s suit will eventually make it to court if New Line does not do as they did with Zaentz and settle it. Thus the advantage of shutting Jackson out of the Hobbit project doesn’t seem apparent to an outsider. They’ll face it at some point—why not bite the bullet, settle, and regain access to the one director virtually guaranteed to make this valuable literary property into a huge hit?

The success of LOTR went beyond any of its makers’ most optimistic expectations. That success was largely due to Jackson and Walsh. They were the ones who brought the project to New Line, which otherwise would have had no way of getting the novel’s production rights. The first film came out in a year that was perhaps the worst the studio had ever endured. In January, 2001, cutbacks imposed by AOL Time-Warner, New Line’s owner, had forced Shaye to let go a hundred employees. This was not a minor thing for such a small company, and one which was known for its long-term retention of a tight-knit staff. In the spring of 2001 New Line had two of its most costly failures with the Adam Sandler comedy Little Nicky and the infamous Town and Country. The December release of Fellowship pulled New Line out of a huge slump. It is probably not true, as many predicted at the time, that the studio would have ceased to exist had it not been for LOTR. It does seem likely, though, that Shaye would have had far less autonomy and power in running the company that he had started.

I discuss the events of that period in detail in The Frodo Franchise. At this point, the fracas seems odd indeed, both from a personal and a financial point of view. There may be other factors involved that those not apparent to outsiders, and we may well never learn what those were.

In the meantime, the actors involved grow older. Ian McKellen went to New Zealand and began playing Gandalf in January of 2000, when he was 60. Last year, at 66, he predicted, “I’ve got another 10 years in me, probably, of capering.” In the same interview he remarked, “I would love to do ‘The Hobbit,’ yes. Partly because I would hate to see anybody else playing Gandalf.”

So would just about anyone else.

[Added August 6: For my earlier comments on the Hobbit project, go here.