Sunday | May 10, 2020

Phoenix (Christian Petzold, 2014).

DB here:

One of my undergrad professors told me: “Bordwell, you have to decide whether you’re going to be a reading man or a writing man.” Professors of the male persuasion talked that way then. When I said I wanted to be both, my mentor puffed his pipe. He really smoked a pipe. He said: “It’s damn hard.” This kindly man knew English Renaissance drama and poetry practically by heart but never wrote a book.

I start to see what he means. For some decades, I managed to read a fair lot and write a decent amount. You’d think in retirement it would get easier. But I have too many interests and projects, and publishers dump a heap of intriguing items on the market every week. The months go by, the books pile up on the side table and on the floor, and I try to keep up. I really do. I’m always behind.

So at intervals I stop obsessing about 1910s cinema and 1940s Hollywood and Rex Stout and how best to think about film form and style, and I swerve to what colleagues are discovering. Turns out, quite a bit. What better time than a plague to catch up?

Flooding the zone

What’s it like to live across the street from a prolific polymath?

For twenty-five years we had as neighbor James W. Cortada, a genuine intellectual range rider. Trained as a scholar in Spanish diplomatic history, he finished his Ph.D. in one of the worst hiring years: 1973, the same year I came out. I was lucky to find work, but Jim took a job selling IBM computers. Eventually he became an executive specializing in innovation and management.

But he was also a compulsive researcher and writer. While holding down a desk job and supervising staff and toting PowerPoints around the world, he managed to publish books in a host of areas. He was a guru of Total Quality Management, producing books and yearbooks on the subject. He also became a premiere historian of computer technology, with such classics as Before the Computer. What I like about this book is the way it integrates study of the tools and machines with examination of the office-based practices of sorting, bookkeeping, and other mundane activities. Unbelievably, Jim continued his graduate interest in Spanish political history. Along the way he wrote a research manual (History Hunting), turned out a study of 9/11’s impact on business, and edited with Alfred Chandler a massive book on information in US life.

Jim writes any size. He has produced The Digital Hand, a magisterial trilogy surveying the use of computers in American life. What about the rest of the world? That’s covered in The Digital Flood, another showstopper. Then there’s IBM: The Rise and Fall and Reinvention of a Global Icon, which is the definitive account of a corporate behemoth, with access to information only an insider could obtain.

Not to mention (so I’ll mention it), Jim’s more or less single-handed creation of a whole discipline: the history of information. The ideas are there in early works, but the first crystallization was the stupendous All the Facts, a sweeping survey of how Americans passed along data–not just in business but in cookbooks, diaries, maps, and other vessels of knowledge.

Since 1971 Jim has authored or edited over seventy books. Retirement has revealed what a slacker he was before. Between March 2019 and March 2020, he published four volumes. He also found time to head our neighborhood association, contribute many articles to professional journals, play with his grandkids, and banter over burritos at El Pastor (before lockdown).

You haven’t lived until your neighbor drops by at the cocktail hour with the cheerful greeting, “How many words did you write today?” Fortunately, he’s utterly generous. Jim reads everything I show him, immediately giving me helpful advice. He’s just an all-around intellectual who, because of the 70s job market, wound up in a non-academic line of work. He shows what you can do if you have brains, pluck, and a hunger to find things out. Long before our millennial “knowledge workers,” he showed what a rigorous university education could bring to corporate culture.

Probably the most immediately significant items in Jim’s recent output are two books he wrote with William Aspray. From Urban Legends to Political Fact-Checking: Online Scrutiny in America, 1990–2015 is a scrupulous in-depth account of how fake facts and the debunking of same stretch back to the very origins of the Net. The book digs back to pre-Internet online legends circulated on Prodigy and America On Line, chief among them being the infamous Willie Lynch letter purporting to instruct planters how to discipline their slaves. The bulk of the book shows how over twenty-five years, rumors and half-truths become depressingly long-lived.

In charting the surging infection of lies, pranks, and blatant dumbassery, the authors also show how snopes and other fact-checking bodies try to catch up. Still, I found the persistence of even the stupidest ones discouraging. Trump’s 2015 assertion that he saw Arabs in New Jersey celebrating 9/11 is an example of the “Celebrating Arabs” meme that popped up immediately after the Trade Center was hit. Asked about it, he asserted: “It was on television. I saw it.” That’s all you need. In charting the surging infection of lies, pranks, and blatant dumbassery, the authors also show how snopes and other fact-checking bodies try to catch up. Still, I found the persistence of even the stupidest ones discouraging. Trump’s 2015 assertion that he saw Arabs in New Jersey celebrating 9/11 is an example of the “Celebrating Arabs” meme that popped up immediately after the Trade Center was hit. Asked about it, he asserted: “It was on television. I saw it.” That’s all you need.

Fake News Nation: The Long History of Lies and Misrepresentation in America is broader and aimed at a more popular audience. It offers eight historical episodes as case studies in rumor and deceit. The earliest instance is the presidential election of 1828, which blended corruption, sex, and racism in an intoxicating cocktail: “General Jackson’s mother was a COMMON PROSTITUTE. . . . She afterwards married a MULATTO MAN, with whom she had several children, of which member General JACKSON is one!!!” Nice to know triple exclamation points aren’t an invention of tweens and trolls. The book surveys conspiracy theories around the assassinations of Lincoln and Kennedy, mythmaking in the Spanish-American War, and disinformation in controversies about Big Tobacco and climate change. It’s a completely fascinating read.

It’s also fairly dispiriting. It brings out the Mencken in me, admittedly never far from the surface. The books suggest that the venality of hoaxers, the credulity of the multitude, and the social incentives to hide the truth and spread lies don’t promote a public demand for accuracy and nuance. What we see now, in the Republicans’ current attempt at a fascist takeover of our civil society, is the implementation of Steve Bannon’s suggestion to “flood the zone with shit.”

It’s not that the wacko alternatives carry much weight, though they do play to darker desires. More important is the sheer firehose fusillade of preposterous claims. Who can keep up? Nuanced fact-checking seems only to add to the swirl of uncertainty. Are coronavirus cases being undercounted? Overcounted? Confusion and overload are central to the plan. Instead of “Drain the Swamp,” the motto is “Swamp the Drain.”

So books like Jim’s and Mr. Aspray’s buoy us as we paddle to keep our heads above the waves of sludge. Meanwhile, Jim is eight chapters into his next opus.

Techbeat

Jim’s work as a historian of business technology reminds us that tech is a part of film history too. But for many decades, materials, machines, and tools weren’t sufficiently reckoned into the study of film. Scholars of early cinema were, I think, the first to examine the standardization of equipment and film stock; Gordon Hendricks’ dauting Edison Motion Picture Myth (1962) situated the emergence of moving-image technology in the context of Edison’s corporate strategy. Eventually, by the 1980s, people were considering the role of camera and lens design, lighting rigs, film stock, and camera carriages in shaping film style. Our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema was one effort in this direction.

Since then many scholars have turned to the histories of image and sound technology to clarify their research questions. Patrick Keating’s The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood is a model of how to integrate information about labor practices, technology, and industrial organization with the results in the finished film. He shows, for instance, that the menu of options available to filmmakers in staging and cutting scenes had knock-on effects in choices about camera mobility, which in turn was facilitated by particular dollies, cranes, and other gadgets available. Since then many scholars have turned to the histories of image and sound technology to clarify their research questions. Patrick Keating’s The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood is a model of how to integrate information about labor practices, technology, and industrial organization with the results in the finished film. He shows, for instance, that the menu of options available to filmmakers in staging and cutting scenes had knock-on effects in choices about camera mobility, which in turn was facilitated by particular dollies, cranes, and other gadgets available.

His analyses of scenes from 1930s and 1940s films, both classic and obscure, train the reader in what to watch for. In all, it’s a persuasive meshing of functional explanations of style with causal accounts of what goes on behind the scenes–not least, the sheer sweat of pushing dollies and following focus. He draws an enlightening contrast with the brain-work of producers, screenwriters, and directors.

The work of production is bodily. The actors move their arms and legs and torsos, and the grip and operator move theirs. Each must anticipate the others’ gestures, like dancers in an ensemble. the Hollywood studio system relied on preproduction planning in order to rationalize production, but the process of filmmaking ultimately came down to craftspeople working together in the moment. One type of collaporation was corporate; the other was corporeal (158).

A graduate of our program, Keating carries forward our respect for filmmaking craft, including its more toilsome routines.

No less sensitive to the concrete demands of technology, and the ingenious workarounds that can be discovered, is Charles O’Brien’s account of the international transition to talkies, Movies, Songs, and Electric Sounds: Translatlantic Trends. Like Keating, he’s studying a body of conventions, here those that arose in the vogue for the international “song film” in 1928-1934. And like Keating, he’s very precise. He measuresg average shot lengths and brings out the implications of how much time is devoted to songs or dialogue.

But this is no simple data dump. O’Brien charts the various strategies in which song sequences allude to the theatre situation and absorb themselves into the ongoing story line. He traces a distinction between the Hollywood song sequences, which were quickly relegated to farces like the Marx Brothers films, and the European sequences, which adapted more varied forms, such as pantomime and verse-like dialogue stretches. The latter strategy was especially common in Germany, partly due to the studios’ commitment to direct sound. O’Brien offers a particularly cogent account of the virtuoso carriage scene in The Congress Dances (1931), which in its joyful excess remains stunning today. (See clip above.)

O’Brien further contextualizes his discoveries by considering broader business culture, such as the market in song recordings and sheet music. All in all, a tight, coherent account of how technological change introduces both functional equivalents of existing techniques and spillover effects–unexpected advantages that artists can exploit.

Shawn VanCour’s Making Radio: Early Radio Production and the Rise of Modern Sound Culture focuses similarly on technology and craft at this period, bringing in other institutional pressures on craft workers making audio artifacts. In fascinating detail, Shawn (another UW alumnus) shows how the separation of body and voice created by radio broadcasts posed many problems for engineers, writers, and other staff. One result was a sort of “practical theory,” a body of ideas about what radio essentially was, alongside particular practices that shaped both technology and dramaturgy.

For instance, everybody recognized the need to dramatize story action with sound effects and music, but paramount was the need to keep dialogue clear. The compromises and trade-offs were debated in trade journals and executed on the airwaves, with fascinating effects on standards of proper audibility. One consequence was the valorization of a “radio voice,” the mellifluous tones suited to the new medium’s demands, both technical and institutional. VanCour shows that these debates were picked up in the motion-picture industry at the period O’Brien investigates. Sometimes, less often than we think, inquiries do converge in fruitful ways.

At intervals of a decade, Paolo Cherchi Usai has rethought the ideas and evidence informing his exploration of silent film. Burning Passions (1991) was a precise manual for archival research. Silent Cinema: An Introduction (2000) was a deeper plunge, taking into account digital transformations that he explored in the contemporaneous The Death of Cinema (2001). Now, he has gone Full Cortada with the massive Silent Cinema: A Guide to Study, Research and Curatorship. At intervals of a decade, Paolo Cherchi Usai has rethought the ideas and evidence informing his exploration of silent film. Burning Passions (1991) was a precise manual for archival research. Silent Cinema: An Introduction (2000) was a deeper plunge, taking into account digital transformations that he explored in the contemporaneous The Death of Cinema (2001). Now, he has gone Full Cortada with the massive Silent Cinema: A Guide to Study, Research and Curatorship.

This is an encyclopedia that reads like a series of engaging art history lectures. In his opening, Paolo acknowledges the avalanche of new material he faced. More than fifty thousand features and shorts have survived from the years 1894 to 1929, and research has expanded accordingly. He pursues three questions: What was silent cinema thought to be at the time? How may we study it? And why does silent film matter as an expression of culture? These questions are pursued in fifteen chapters bearing one-word titles like “People,” “Building,” “Duplicates.”

No summary can do justice to the world that this book opens up. We learn about the machines, the venues, the processes, and the people. There are floorplans of studios and theatres, comparisons of different color processes (gorgeous), and discussions of how projectionists regulated the speed of the show. The book devotes a whole chapter to theatre acoustics, the use of sound effects and recordings, and even the clapper sticks used by the benshi commentators in Japan. Another fascinating chapter traces the fate of a single film through multiple versions, from camera negative to digital format. Throughout, Méliès’s Trip to the Moon is used as a benchmark to remind us of all the ways that every copy is a unique artifact, a claim that Paolo has advanced consistently over the years.

Silent Cinema is a must-have book for everyone interested in cinema of all eras. Its publication price made it the film-book bargain of the year, but Bloomsbury and Amazon are now offering it on obscenely generous terms. If you’re not a silent fan, this giddy ride can make you one.

Auteurs never went away

The Headless Woman (2008).

At intervals people tell us that we need to stop studying directors and turn instead to Culture or Other Collaborators or some other inputs. Surely the classic formulations of auteur criticism have some problems. Still, it’s terribly hard to shake the idea that a great many films are usefully understood in light of directors’ purposes and plans. Directors play a central role in the production process and under certain circumstances are granted the possibility of building a body of work. We can argue about Roy del Ruth or Michael Bay, but not certain “strong filmmakers” who have, as Andrew Sarris put it long ago, personal visions.

An obvious example is the obstinately eccentric Jacques Tati. In just a few films, he changed our conception not only of film comedy but of the art of cinema itself. How that happened is the subject of Malcolm Turvey’s fine book Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comic Modernism. Malcolm, who just last week contributed a guest blog on research into neuroscience and camera movement, is a major scholar of cinematic modernism. Here he shows that in spirit Tati is an experimental filmmaker. An obvious example is the obstinately eccentric Jacques Tati. In just a few films, he changed our conception not only of film comedy but of the art of cinema itself. How that happened is the subject of Malcolm Turvey’s fine book Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comic Modernism. Malcolm, who just last week contributed a guest blog on research into neuroscience and camera movement, is a major scholar of cinematic modernism. Here he shows that in spirit Tati is an experimental filmmaker.

There’s an extensive body of close analysis on Tati, to which Kristin in particular contributed as far back as the 1970s. Malcolm adds to this with some keen studies of framing, sound, and gag structures. What he brings to the table is the way that distinctively modernist conceptions of humor and comedy find their way into this vaudeville-inspired entertainer. From aleatory gags–apparently random synchronizations of noises and movements–to fragmented and incomplete or unconsummated gags, such as the precarious taffy that doesn’t quite plop off its hook, Tati intuitively reawakens the spirit of irrational laughter that inspired avant-gardists.

Malcolm traces Tati’s lineage back to Albert Jarry, Jean Cocteau, and the avant-garde’s fascination with circus and music hall. Other sources were Chaplin, Léger, and René Clair. In a sort of feedback loop, the avant-garde borrowed from slapstick comedy, while Tati’s cinematic transformation of music-hall numbers into decentered, absurd, or perplexing cinematic sequences revives the anarchic spirit of the modernists. His satire of the postwar managed society sought to make us see the world around us from a potentially subversive angle. The dreary vacation routines of M. Hulot’s Holiday and the opaque surfaces and chilly contours of Mon Oncle and Play Time are disrupted by characters who revel in disruption, and a filmmaker who imagines our daily march easily turned into charmingly clumsy dance. Beneath the paving stones, the beach, went a May ’68 slogan. “His was the quintessentially avant-garde project,” writes Malcolm, “of closing the gulf between art and life” (p. 237).

Tati went his own way, but many of our auteurs are part of larger schools or trends. From almost the beginning of cinema, historians have talked about movements or schools whose members share broad goals or generational sources, but who then can be distinguished by virtue of their particular sensibilities. Such, for instance, is Christian Petzold. One of “the Berlin School” of filmmakers coming to prominence in the 1990s, he has gained fame internationally, particularly with Barbara (2012), Phoenix (2014), and in 2018 Transit. I’m still catching up with his oeuvre, having seen these films at festivals (along with his contribution to Dreileben, 2011), and I’m also roaming among the no less interesting work of his colleagues, particularly Angela Schanelec and Thomas Arslan. Tati went his own way, but many of our auteurs are part of larger schools or trends. From almost the beginning of cinema, historians have talked about movements or schools whose members share broad goals or generational sources, but who then can be distinguished by virtue of their particular sensibilities. Such, for instance, is Christian Petzold. One of “the Berlin School” of filmmakers coming to prominence in the 1990s, he has gained fame internationally, particularly with Barbara (2012), Phoenix (2014), and in 2018 Transit. I’m still catching up with his oeuvre, having seen these films at festivals (along with his contribution to Dreileben, 2011), and I’m also roaming among the no less interesting work of his colleagues, particularly Angela Schanelec and Thomas Arslan.

All the more welcome, then, is Brad Prager’s monograph on Phoenix in the Camden House German Film Classics series. This is an admirable close reading of Petzold’s film, bringing a range of cultural references to bear on the suspenseful story of a woman returning from a death camp to a husband who, it turns out, has his own guilty secret.

Prager skilfully invokes the citations–Vertigo, Siodmak’s work, American noir–and considers how Petzold’s genre affiliations (he often makes politically inflected thrillers) merge with his examination of trauma in German history. It isn’t easy to do justice to the film’s remarkable climax, which I decline to spoil for you, but Prager manages it. This scene is one of the great fake-outs in recent film, I think, and Prager is alive to all its bleak ironies, including the heroine’s rendition of Kurt Weill’s “Speak Low.”

Phoenix (the book) is a model of compact, probing analysis. I’d be happy to have Prager tackle another Petzold, especially one I just saw and much admire, his first feature The State I Am In (Die innere Sicherheit, 2000), which seemed to me to do for Fritz Lang what Phoenix does for Hitchcock. More generally, Petzold has a pictorial exactitude we seldom see nowadays, and he deserves wide-ranging study.

The New Argentine Cinema wasn’t as cohesive a group as the Berlin School, but there’s little doubt that Lucrecia Martel emerged as one of its singular talents. I remember the jolt of seeing La ciénaga (2001) and immediately taking frames from a 35mm print so we could feature it in Film History: An Introduction (2d ed., 2002). The Headless Woman (2008) at Vancouver confirmed my sense of a major talent, and most recently Zama (2017) confirmed it. Kristin wrote an appreciation from the Venice premiere. It was the best film we saw there and one of the finest of that year. The New Argentine Cinema wasn’t as cohesive a group as the Berlin School, but there’s little doubt that Lucrecia Martel emerged as one of its singular talents. I remember the jolt of seeing La ciénaga (2001) and immediately taking frames from a 35mm print so we could feature it in Film History: An Introduction (2d ed., 2002). The Headless Woman (2008) at Vancouver confirmed my sense of a major talent, and most recently Zama (2017) confirmed it. Kristin wrote an appreciation from the Venice premiere. It was the best film we saw there and one of the finest of that year.

All the features of a classic auteurism were here (and in The Holy Girl, 2004): persistent themes, distinctive plotting, signature style. These qualities are given full consideration in Gerd Gemünden’s Lucrecia Martel. Gerd has done a thorough job in surveying her career and dissecting the films. He shows that she is especially interested in rendering physical sensation–textures, touch–through evocative images and sounds. Anybody who has seen La ciénaga can’t forget the opening scene’s glimpses of a scummy swimming pool and flaccid necks and groins, let alone the wine and splinters of glass splashed onto a drunken woman’s corrugated chest. The rain in The Headless Woman is no less palpable, while the humid torpor of the colonial outpost in Zama is sticky almost beyond endurance. This tactility makes Martel’s stringent criticism of class inequities even more powerful.

This critical aperçu finds its place in Gerd’s comprehensive account of Martel’s oeuvre. As is usual in the series Contemporary Film Directors (yeah, an auteur title for sure), we get detailed production dossiers, wide-ranging background on literary sources and cultural context of reception, and close studies of the films. There’s also a rich bibliography and an interview with some surprises; for such an elliptical, visually oriented director, Martel claims that oral storytelling is a primary inspiration.

Auteur studies are not what they used to be. Instead of paeans to directorial genius, they can be subtle, wide-ranging discussions of what Eliot called “tradition and the individual talent.” Acknowledging influences, circumstantial pressures, forced choices, opportunities, and the like, our writers can show that some directors still build up films that yield resonant personal expression. Choice within constraints: that’s the story of creativity in all the arts, and the most nuanced auteur accounts can show how that process works in fascinating detail.

Will we still have books as the coronavirus burns its way through our lives? Can publishers survive? Yes, we’re sequestered, and maybe that’s encouraging us to read more; but people will have a lot less money for books. What will entice us to invest in personal libraries?

An encouraging sign is that so many of the books on film here have very fine illustrations, many in color. So thanks to the publishers for understanding that well-reproduced pictures can attract readers as well as document arguments. And Silent Cinema includes a filmography with references to online collections. With books like these, we can correct and expand what my old prof said: You can be a reader and a writer and a viewer. Now we just need time, and safety.

Each of these books represents an integral research project, but all are part of larger research programs too. Jim Cortada’s work is an epic instance, but we find the same trajectory in the film scholars’ careers. As writer, archivist, and filmmaker, Paolo Cherchi Usai has devoted his life to silent cinema. Patrick Keating’s study of camera movement joins his first book on the history of Hollywood lighting. Charles O’Brien has already given us a fine-grained comparison of the conversion to talkies in the US and France. Shawn VanCour is active in archiving sound and is exploring radio’s relation to other acoustic media. Malcolm Turvey’s book on Tati joins his earlier books on avant-garde filmmakers’ conceptions of vision and 1920s modernism in Europe. Petzold’s film is a natural step beyond Brad Prager’s work on Herzog and on visuality in German Romanticism. Gerd Gemünden’s many books include one on German exile cinema and Billy Wilder’s American films.

Kristin’s writings on Tati from the late Seventies are in her Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis.

P.S. 29 May: I just got another volume that chimes with this entry. It’s Marco Abel’s The Counter-Cinema of the Berlin School from 2013, and it’s a very comprehensive and in-depth consideration of this important group.

Trafic (Jacques Tati, 1971).

Posted in Books, Directors: Petzold, Film history, People we like, Silent film |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Back on the book beat open printable version

| Comments Off on Back on the book beat

Sunday | May 3, 2020

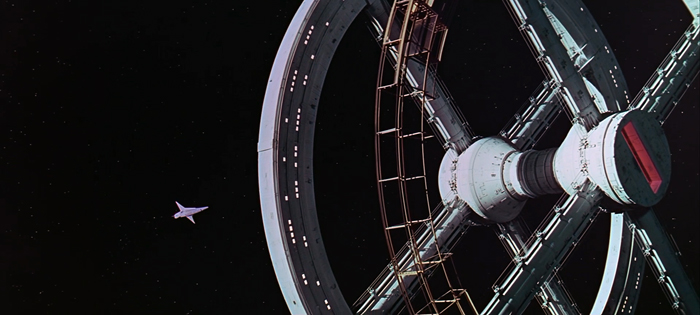

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

DB here:

Over the years we’ve brought you several guest posts from friends whose research we admire. The list includes Matthew Bernstein, Kelley Conway, Leslie Midkiff DeBauche, Eric Dienstfrey, Rory Kelly, Tim Smith, Amanda McQueen, Jim Udden, David Vanden Bossche, and our regular collaborator Jeff Smith (most recently, on Once Upon a Time in Hollywood…).

Today our guest is Malcolm Turvey, Sol Gittleman Professor in Film and Media Studies at Tufts University. Malcolm has long been a voice calling for rigorous humanistic study of film. His books include Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition (2008) and The Filming of Modern Life: European Avant-Garde Film of the 1920s (2011). Just this year he published Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comedic Modernism. (More on this in a future blog entry.) Among his many specialties, Malcolm applies the philosophical tools of conceptual analysis to problems of film criticism and theory.

My previous entry discussed some ways psychological research has helped me understand how films work, and I touched on the recent efforts to invoke mirror neurons to explain some effects that movies have on us. Today Malcolm takes a deeper plunge into this line of thinking, and the result is an exciting instance of how careful intellectual debate can be carried out in film studies. It’s also a cautionary tale about relying on scientific research to explain the appeal of artworks. A more extensive version of this piece is slated for publication in Projections: The Journal of Movies and Mind.

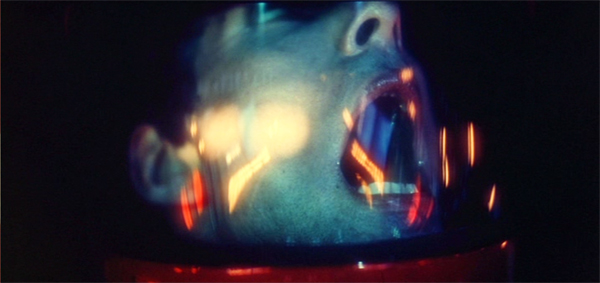

In Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946), Alex Sebastian (Claude Rains) is one of a group of Nazis who have relocated to Brazil after WWII. He has unwittingly married Alicia Hubermann (Ingrid Bergman), an undercover American agent seeking his circle. When Alicia learns that their scheme somehow involves the wine bottles locked in her husband’s cellar, she decides to procure the key so that she and her handler (and lover), Devlin (Cary Grant), can investigate.

Her opportunity comes in a characteristically suspenseful scene. Alicia nervously contemplates her husband’s keychain lying on a bureau as he finishes taking a shower nearby. She bravely steals the key and barely escapes discovery as Alex emerges from the bathroom. But what is the source of the scene’s suspense?

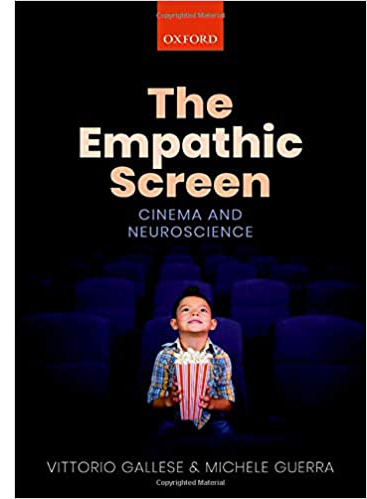

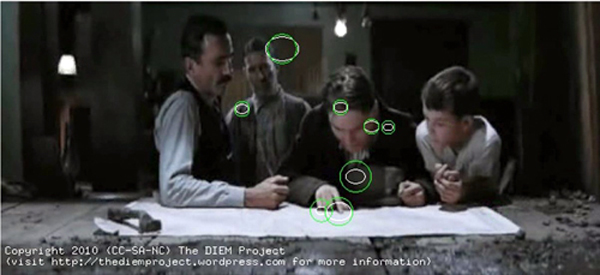

In a provocative new book titled The Empathic Screen, Vittorio Gallese and Michele Guerra claim the suspense should be attributed primarily to a brief, “human-like” camera movement toward the keys that occurs as Alicia looks at them. Moreover, they draw on neuroscience, specifically the science of mirror neurons, to make their case.

Here is the scene.

Are Gallese and Guerra right about the role played by the camera movement? For reasons I’ll give shortly, I doubt they are. More importantly, I question whether the neuroscientific evidence they lean on supports their case. This may seem like nit-picking, but I think their appeal to neuroscience contains valuable lessons about how students of film should–and shouldn’t–engage with scientific research.

Science and film studies

Readers of this blog are likely familiar with the idea that science has an important role to play in film studies. Since 1985, David Bordwell has drawn on contemporary cognitive psychology to answer questions about perceiving and understanding narrative films, thereby launching a new paradigm in film theory that has come to be known as cognitivism. In his previous entry, David offers an overview of his current thinking about cognition and movies.

Cognitivism has generated much heat in academic film studies. But at its heart is what should be an uncontroversial principle: that those who wish to understand the perceptual, cognitive, and affective capacities with which we engage with art should turn to the work of those who know something about these capacities, namely, the psychologists and other scientists who study them empirically and propose theories about them in light of their findings.

This is because our pre-scientific, “folk” understanding of our psychological capacities is usually non-existent or flawed. It is, for instance, hard to explain why we see still frames as moving images when they are projected above a certain speed merely by reflecting on our “phenomenological” experience of watching movies.

Perceptual psychologists, however, have studied this phenomenon empirically and have proposed explanations for it, such as critical flicker fusion frequency and the phi phenomenon (although like all scientific explanations, these are open to revision and even falsification in the light of new evidence and theorizing). The same is true of other features of our experience of films, and cognitive film scholars have built on David’s work by drawing on contemporary scientific knowledge of emotion, music, moral psychology and much else.

This does not mean that film studies is or should be a science. As David and Kristin’s blog entries repeatedly demonstrate, many of the things we want to know about cinema and the other arts can be discovered through non-scientific, humanistic methods such as analyzing films and researching the context in which they were made. In other words, our methods should be tailored to the questions we ask. Cognitivism argues that some important questions about the cinema can be answered by science, not that all or even most can.

The deceptive authority of Science

That said, I worry that engaging with science in a responsible manner is much more difficult than some of my cognitivist colleagues acknowledge. That difficulty is due, in part, to the “authority” of science.

Because of this authority, many non-scientists might assume that science is more settled than it often is, especially in a human science such as psychology. Those of us who aren’t scientists could be tempted to think that a scientific argument must be true because, well, there are scientific data to support it.

But as the recent “repligate” controversy in psychology and elsewhere shows, just because a scientist can present evidence for their views does not make them true. Data can be unreliable and the conclusions drawn from themunwarranted, as we are witnessing on a daily basis during the coronavirus pandemic.

Although there are occasional scientific revolutions, if science makes progress, something that some ph0ilosophers have questioned, it usually does so incrementally through trial and error, and there is much more failure than success. Those of us who don’t participate in this dialectical process might be apt to forget the provisional, tenuous status of much scientific research and accord it more certainty than it warrants.

Mirror neurons: The controversy

This has happened, I believe, with mirror neurons, a new scientific paradigm that has emerged over the past few decades and that some film scholars have started to draw on to explain some of our responses to films, such as empathizing with characters.

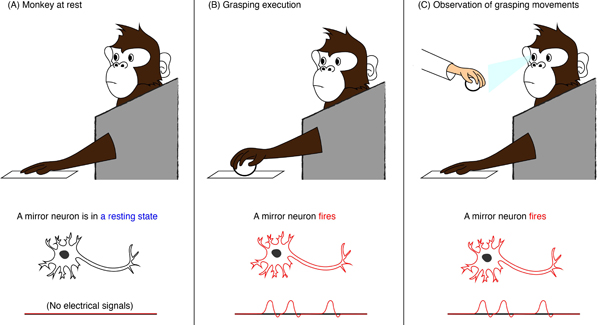

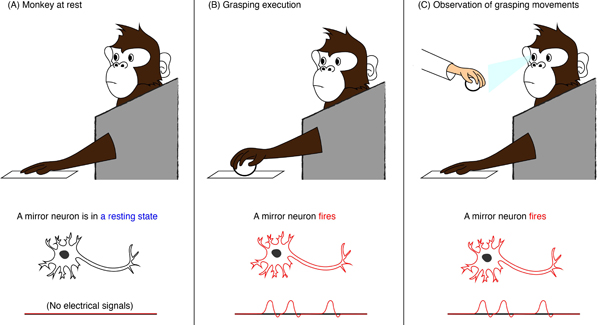

Mirror neurons are neurons that fire both when a subject executes a movement and when the subject sees the same movement executed by another. They were first discovered in the early 1990s in the motor cortex of pigtail macaque monkeys by a group of neuroscientists in Parma, Italy, and they have been invoked to explain a wide array of human behaviors such as language, imitation, empathy, art appreciation, and autism.

This is because mirror neurons appear to provide an explanation for how macaques and human beings understand the actions of their conspecifics. Researchers speculate that, if the same neurons fire when a subject reaches for an object, say food, and when the subject observes another agent reaching for food, the subject must be simulating the observed reaching-for-food action in its brain without actually executing it.

By simulating the observed reaching-for-food movement in its neurons, the subject knows the meaning of the movement–reaching for food–because it has performed the movement itself in the past, and attributes that meaning to the action being executed by the agent it observes, thereby comprehending it. As Marco Iacoboni puts it in a popular treatment of the subject:

To see . . . athletes perform is to perform ourselves. Some of the same neurons that fire when we watch a player catch a ball also fire when we catch a ball ourselves. It is as if by watching, we are also playing the game. We understand the players’ actions because we have a template in our brains for that action, a template based on our own movements.

Yet within neuroscience, mirror-neuron explanations of human behavior are controversial and contested, and no less an authority than Steven Pinker has referred to them as “an extraordinary bubble of hype.” Meanwhile, cognitive scientist Gregory Hickock has written an exhaustive book on the subject with a title that says it all: The Myth of Mirror Neurons.

Film scholars who appeal to the mirror neuron paradigm have not engaged with criticisms of it. Hence, their neural explanations of cinema appear to be supported by a scientific consensus that is in fact lacking, and they may not be drawing on the best current science.

For example, the philosopher of film Dan Shaw maintains that “The discovery of the existence and emotive function of mirror neurons confirms that we simulate other people’s emotions in a variety of ways, even in cinematic contexts,” and he views mirror neurons as the neurophysiological foundation for cinematic empathy. Notice how Shaw makes a strong claim here by using the word “confirms.”

Yet, although Shaw writes that “it is a cliché that monkeys are good imitators,” Pinker suggests that macaques do not imitate and they have “no discernible trace of empathy.” This is despite their possession of mirror neurons. Thus, the mere presence of mirror neurons or a mirror system in a creature cannot be evidence, in and of itself, for the creature’s capacity for empathy. While it might provide one of the neural foundations for empathy or contribute to its realization in some way, much more is needed than mirror neurons or a mirror system for a creature to empathize. Their presence certainly doesn’t “confirm” that we empathize with characters in film.

It is, however, a different, equally pernicious consequence of the authority of science that I wish to highlight here using mirror neurons. The apparent authority of a scientific paradigm can lead scholars to cherry-pick and mischaracterize our artistic practices in order to fit the science. This brings us back to Gallese, one of the co-discoverers of mirror neurons, and Guerra, and their claims about camera movement.

Camera movement and mirror neurons

Gallese and Guerra argue that our mirror neurons not only simulate the emotions of film characters but also the anthropomorphic movements of the camera recording them.

We maintain that the functional mechanism of embodied simulation expressed by the activation of the diverse forms of resonance or neural mirroring discovered in the human brain play an important role in our experience as spectators. Our ability to share attitudes, sensations, and emotions with the actors, and also with the mechanical movements of a camera simulating a human presence, stems from embodied bases that can contribute to clarifying the corporeal representation of the filmic experience. [My emphasis.]

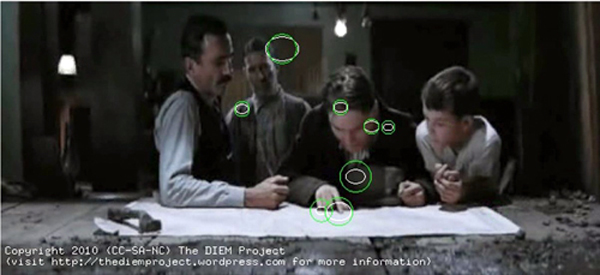

In support of their contention that the mirror neurons of film viewers simulate human-like camera movements, Gallese and Guerra cite an experiment they participated in. This measured the motor cortex activation of nineteen subjects who were shown short video clips of a person grasping an object. The action was filmed in four different ways: with a still camera, a zoom, a dolly, and a Steadicam.

“The results were positive,” Gallese and Guerra conclude. “Shortening the distance between the participant and the scene by moving the camera closer to the actor or actress resulted in a stronger activation of the motor simulation mechanism expressed by the mirror neurons” relative to the clips shot with a still camera. Moreover, the subjects rated those scenes filmed with a moving camera as more “involving.”

Gallese and Guerra rely on this single experiment to make a bold argument about the role of camera movement in the design of films and its effect on the experience of film viewers. “The involvement of the average spectator [in a film] is directly proportional to the intensity of camera movements.” This is because “the sense of participation in the camera action is undoubtedly enhanced by the fact that its behavior is interpreted by both filmmakers and spectators according to evident and automatic anthropomorphological analogies.”

When scenes are recorded with human-like camera movements, they seem to be suggesting, our mirror neurons simulate these camera movements because they are like actions we ourselves have performed. This in turn results in a feeling of “involvement” or “participation” in the scene on the part of the film spectator.

There is much one could question about this experiment and the conclusions Gallese and Guerra draw from it. For example, if it is camera movement that elicits mirror neuron simulation which in turn gives rise to a sense of immersion, viewers should feel involved in the camera movement, not the sceneit films. Indeed, what is depicted in the scene should be irrelevant to the viewer’s feeling of involvement if it is the camera movement that gives rise to this feeling by eliciting mirror neuron simulation.

Making the art fit the science

It is, however, the theory’s cherry-picking and mischaracterization of the artistic practice of cinema that most concern me here. According to this theory, as we have seen, “the involvement of the average spectator [in a film] is directly proportional to the intensity of camera movements.” The explanatory claim is that anthropomorphic camera movements, in other words those that resemble the human action of walking through space, elicit the mirror neuron simulation that gives rise to the viewer’s immersion in the film.

This is a strong claim, and if it were true it would have profound implications for both the study of film and filmmaking. It would mean that the more anthropomorphic camera movements that films contain, the more involving they would be for viewers. It would also mean that scenes filmed with human-like camera movements would be more involving than those shot with a still camera, and that scenes filmed with non-anthropomorphic camera movements would be less involving than those shot with anthropomorphic ones.

The latter is due to the mirror neuron simulation theory’s argument that we can only simulate movements we ourselves have performed. Hence, camera movements must be like ones we have executed ourselves in order for our mirror neurons to simulate them and produce the requisite sense of immersion.

Before assessing this claim, one question needs to be answered. What, exactly, is meant by involvement, participation and immersion? After all, there are a number of different kinds of possible involvement in a film.

We can be cognitively immersed in a film when we are intensely interested in the outcome of the plot or the revelations of a documentary. We can also be emotionally involved, as when we feel strong emotions toward the people or events depicted in the film. There is also aesthetic involvement when we pay close attention to and evaluate the design properties of a film. Then there’s physical or corporeal involvement, as when we are physically impacted by film techniques, such as the startle effect or bright lights and loud sounds. Doubtless there are other kinds of involvement too.

Gallese and Guerra never explicitly define what they mean by involvement, although on occasion they mention a “sensation of immersion in the spatiotemporal dimension of film.” In an earlier text they claimed that, by using the camera to mimic bodily movement, filmmakers make audiences feel that “we are inside the diegetic world, we experience the movie from a sensory-motor perspective and we behave ‘as if’ we were experiencing a real life situation.”

Personally, I am not sure what they mean by this. I have never felt immersed in the space and time of a film in the sense of somehow thinking or feeling that I am actually inside it. More importantly, it is not clear that the subjects of the experiment on which their theory is based meant spatiotemporal involvement as opposed to cognitive, emotive, aesthetic or other kinds of immersion when they rated how involved they felt in the clips they were shown. Thus, Gallese and Guerra’s experiment may provide no empirical evidence at all for their occasional references to spatiotemporal participation.

Confusingly, however, Gallese and Guerra sometimes seem to mean involvement in another sense of the term I have clarified. Regarding the brief camera movement toward the keychain in the scene from Notorious of Alicia stealing the key, they contend that “The problem that Hitchcock had to solve in this complex sequence was how to bring the spectator to an almost unbearable level of suspense.” They suggest that if Hitchcock had only used “classical editing” to film the scene, “our level of involvement would not be nearly so high.” They conclude: “This is why Hitchcock uses camera movement; it is this movement that creates the overpowering tension.”

Here, Gallese and Guerra seem to be using “involvement” in the emotive sense of feeling strong emotions such as “tension” and “suspense” about the characters and events in the scene, and they make no mention of “spatiotemporal immersion.” Either way, Gallese and Guerra provide no evidence at all that it is this brief camera movement “that creates the overpowering tension” in the scene. While the camera movement is certainly effective in drawing our attention to the keys and conveying Alicia’s anxious focus on them, I conjecture that there is a far more obvious, broadly “cognitive” reason for the scene’s suspense.

This is the possibility that Alicia, with whom we sympathize, will be caught stealing the key by her husband, who is a ruthless Nazi. Gallese and Guerra, however, discount such a narrative-based explanation for the suspense. They argue that “What strikes us most in films like Notorious is Hitchcock’s almost complete indifference to the plot” and that “the state of suspense in which we find ourselves at every viewing of Notorious has nothing whatsoever to do with the story.”

Yet, according to Hitchcock biographer Donald Spoto, Hitchcock himself wrote the outline for Notorious in late 1944, and then spent three weeks closeted with Ben Hecht writing the script, which was further modified in late-night script sessions with David O. Selznick before the project was eventually sold to RKO and filming began in October 1945. While it may be true that Hitchcock tended to see the plots of his films as merely a means to creating the arresting images and eliciting the strong emotions from his audiences that truly interested him, this does not mean he was “indifferent” to plot. He spent considerable time developing his scripts, and he was keen to work with talented screenwriters such as Hecht.

Nor is it plausible that the suspense in Notorious “has nothing whatsoever to do with the story.” Indeed, suspense is usually defined as a state of anxious uncertainty about what will happen in the story. If suspense has nothing to do with the story, it is hard to know what viewers feel suspense about. In the key-stealing scene in Notorious, it is surely the case that we are anxious about the possibility that Alicia will be caught in the act of stealing the key by her husband, an event that might happen in the narrative. If not, what else might the suspense be directed at?

Of course, the suspense in this scene is not solely dependent on the story but also on the scene’s style. But there are other stylistic techniques that play a much bigger role than the camera movement in the creation of suspense in the scene. For example, Alex’s shadow is visible on his partially open door as he towels himself dry and moves around the shower room.

This activity suggests that he has finished his shower and will emerge at any second. It starts to seem more likely that Alicia will be caught stealing the key, thereby intensifying the suspense. Meanwhile, other than delaying the scene’s outcome by a few seconds, it is not clear how the camera movement toward the keychain itself intensifies the scene’s suspense.

What is happening in the narrative and what is conveyed by other stylistic techniques, such as Alex’s shadow on the door and the music on the soundtrack, are the factors that intensify the scene’s tension. It seems highly unlikely that “our level of involvement would not be nearly so high” in the absence of the camera movement, in the sense of feeling tension and suspense about the scene’s outcome. Certainly, Gallese and Guerra provide no evidence to this effect.

Furthermore, as I’ve already mentioned, Gallese and Guerra’s theory at best explains our sense of involvement in the camera movement, not the scene it films. Recall that it is the camera movement itself that our mirror neurons simulate. It is unclear from their theory, therefore, how our putative feeling of immersion in the camera movement, if indeed we do feel immersed in it, can yield suspense about the concrete actions being filmed.

The category of human-like camera movement, if such a category is functionally relevant to cinema, comprises many fine-grained variations with different effects. Camera movements, for example, can elicit curiosity by making us wonder what they will reveal, as well as surprise when they come to rest on something unexpected. They can startle through their rapidity, as when swish pans suddenly disclose something off-screen, or they can uncover information at an agonizingly slow pace. They can reveal characters’ mental states through push-ins that show us that a character is concentrating hard on something, or they can hide information from us by moving away from it. They can also be aesthetically pleasing, as when we marvel at their gracefulness or the intricacy with which their movements are coordinated with those of the characters. None of these sources of the power of camera movement are explained by arguing that mirror neurons fire in response to anthropomorphic camera movements, if indeed they do.

Most broadly, as David points out in his previous entry, there is much that their theory cannot capture or explain about the power of framing. A static camera can evoke tremendous suspense, as David’s example from Hou’s Summer at Grandpa’s illustrates. It is hard to see what a tracking shot would add at such a moment.

The lessons of film history

Of course, just as damaging to the theory are the countless examples from the rich history of film of highly suspenseful, tension-filled, and in other ways involving scenes that lack anthropomorphic camera movements or that contain non-anthropomorphic ones.

In Notorious, right after the scene in which Alicia steals the key and is nearly caught by Alex, there is a crane shot in which the camera, having panned across the party in the hallway below from a first-floor landing, glides smoothly down toward Alicia talking to Alex and some guests in the hallway and ends in a close-up on her hand holding the key to the cellar.

Given that no human being could perform this movement, our mirror neurons shouldn’t be able to simulate it and produce a feeling of involvement in it. Yet, I hypothesize that, for most viewers, this camera movement creates a strong sense of cognitive, emotive, aesthetic, and other forms of engagement in the scene.

Among other things, this movement prompts us to wonder how Alicia is going to gain entry to the wine cellar without her husband noticing, thereby intensifying our sympathetic concern for her and our suspense about whether she will be caught. And in its overtness, it might make us think about Hitchcock’s choice of technique and the reasons behind it. For some, it might even induce that sense of “spatiotemporal immersion” that Gallese and Guerra mention given that it brings our perceptual perspective close to Alicia’s in the midst of the party, although I personally don’t feel this.

Either way, in this case, it cannot be due to mirror neuron simulation that we experience these forms of immersion. This is a non-anthropomorphic camera movement that human beings cannot execute themselves and therefore cannot simulate with their mirror neurons.

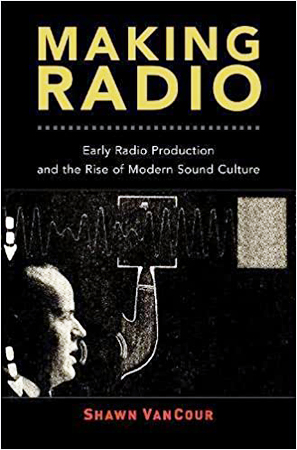

An example from a film by a different director would be the shots in 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968) of Dr Floyd (William Sylvester)’s ship docking with a space station while Strauss’s Blue Danubewaltz plays on the soundtrack. (See image surmounting today’s entry.) For many, the smooth camera movements through space in this sequence evoke an intense sense of weightlessness, thereby creating a physical or corporeal form of involvement in the film. Yet, very few of us have moved in space or have experienced weightlessness, meaning that our mirror neurons should not be able to simulate these camera movements.

Then there are the copious examples of involving scenes that lack camera movement. Hitchcock’s oeuvre contains many, such as the infamous shower scene in Psycho (1960), which is devoid of camera movement during the 20 seconds or so in which the stabbing of Marion Crane takes place. Another example is the highly suspenseful sequence in Strangers on a Train (1951) in which Bruno (Robert Walker) drops Guy (Farley Granger)’s cigarette lighter down a drain while he is on his way to plant the lighter at the amusement park where he murdered Guy’s wife, Miriam (Kasey Rogers). Bruno wishes to implicate Guy in the murder, and Guy, who is a professional tennis player, has guessed Bruno’s plan and is trying to complete a tennis match in time to stop him from planting the lighter. Hitchcock cuts back and forth between the tennis match and Bruno’s efforts to reach down into the drain and retrieve the lighter.

Interestingly, while there is some camera movement at the beginning of the sequence, as the suspense builds, the camera movement lessens. Hitchcock relies largely on still shots of Bruno’s grimacing face as he reaches into the grate, his hand inside the grate and the lighter below it, and the faces of the referees and spectators at the tennis match. Only the shots of Guy and the other tennis player contain a little movement when the camera slightly reframes them as they move to hit the tennis ball.

This sequence is considered one of the most suspenseful (and thereby emotionally involving) in Hitchcock’s oeuvre, yet it defies Gallese and Guerra’s prediction that “The involvement of the average spectator [in a film] is directly proportional to the intensity of camera movements.”

So does the astonishing sequence in William Wyler’s The Little Foxes (1941) in which Horace (Herbert Marshall), having told his estranged wife, Regina (Bette Davis), of his plans to leave his fortune to their daughter, begins experiencing painful symptoms of his heart disease as she tells him how much she despises him.

Horace reaches for his heart medication but knocks over the bottle and its contents and begs his wife to fetch another bottle of medication from upstairs. She, however, sits immobile while Horace, realizing she will not help him and wants him to die, staggers around her, clinging to the wall, and stumbles upstairs before collapsing on the staircase. An agonizing long take lasting about forty seconds shows Regina in medium shot sitting while her husband, who is out of focus, moves toward the stairs, and the shot is immobile except for slight reframings to keep Horace partly visible in the shot.

This is an intensely suspenseful, emotionally involving moment as we wonder whether Horace will reach his medication in time, or Regina or someone else will take action to help him. Yet, there is no anthropomorphic camera movement to elicit our sense of involvement in the scene. On the contrary, according to many critics, it is precisely the lack of camera movement that contributes to its emotional intensity. As André Bazin noted, “Nothing could better heighten the dramatic power of this scene than the absolute immobility of the camera,” in part because it mirrors and emphasizes the “criminal inaction” of Horace’s wife, Regina, who is hoping he will fail to reach his medication and die so that she can be rid of him and claim his fortune.

Gallese and Guerra could perhaps protest that I have misconstrued their theory. Although their claim that “The involvement of the average spectator [in a film] is directly proportional to the intensity of camera movements” seems to suggest that anthropomorphic camera movement is both a necessary and sufficient condition for occasioning involvement in a film, they might admit that immersion can be elicited in other ways. Instead, they could allow, human-like camera movement is merely a sufficient condition for involvement, not a necessary one. When it is present, we feel immersed in films, although this is not the only route to immersion.

However, it is not difficult to think of films containing lots of camera movement of both the anthropomorphic and non-anthropomorphic kinds that fail to engage viewers. An example is Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994), a film in which, as David Ansen of Newsweek put it, “The camera, and the actors, are always in a mad dash from here to there” (Ansen 1994). Nevertheless critics, who according to Gallese and Guerra “usually get much more excited” when camera movement is present, largely panned the film. (For what it’s worth, the film has a critics’ score of 38% and audience score of 49% on Rotten Tomatoes.) As Ansen put it:

What we get is Romanticism for short attention spans; a lavishly decorated horror movie with excellent elocution. [Branagh’s] strategy undermines itself–there’s a lot of sound and fury, but all the grand passions are indicated rather than felt. Watching the movie work itself into an operatic frenzy, one remains curiously detached: the grand gestures are there, but where’s the music? [My emphasis.]

Anthropomorphic camera movements do not, therefore, even appear to be a sufficient condition for immersion in a film, let alone a necessary one.

The way forward?

Gallese and Guerra, it seems to me, cherry-pick examples from films that appear to support their theory, and ignore obvious counterexamples even in the films they examine. They also mischaracterize scenes such as the one in which Alicia steals the keys, overlooking other evident sources of “involvement,” a term they fail to define consistently. They do, I suspect, because they are in thrall to the mirror neuron theory, and they therefore force the art to fit the theory.

None of this means that cognitivism should be abandoned and that film scholars shouldn’t be turning to science. Nor does it mean that camera movement doesn’t sometimes elicit and intensify emotions such as suspense. Moreover, neuroscience may well be able to shed light on some of the reasons why this happens, although many more experiments are needed to demonstrate this than the single one relied on by Gallese and Guerra.

But it does suggest that our engagement with the sciences should be governed by two principles.

First, when drawing on a scientific theory, it is crucial that film scholars also consider criticisms of it. Despite its authority, scientific research is typically provisional. Those of us in the humanities are not usually in a position to determine who is right in a scientific debate. So we should entertain criticisms of the scientific theory, in case they reveal pitfalls and other problems in applying the theory to cinema, or show the theory to be on far less secure ground than it may seem to be.

Second, those of us who are humanistic scholars of film should trust the knowledge we have gleaned from decades of work on the cinema. We shouldn’t simply accept conclusions that contradict this knowledge because they are supposedly scientific. We should not, in other words, be cowed by the authority of science. While we haven’t gotten everything right, most of us know from a little reflection, for example, that anthropomorphic camera movements aren’t required for greater “involvement” in a film.

Of course, we should allow for the possibility that our assumptions about these and other matters are incorrect. But given the weight of experience and knowledge behind them, the evidentiary bar should be set very high for their disconfirmation by empirical scientific research.

Thanks to Malcolm for all his work in preparing this version of his paper for our blog. Another essay of his along these lines is “Can Scientific Models of Theorizing Help Film Theory?” in Philosophy of Film: Introductory Texts and Readings, ed. Angela Curran and Tom Wartenberg (Blackwell, 2004), 21-32

Quotations from Vittorio Gallese and Michele Guerra’s Empathic Screen come from pp. 68, 111, 91, 94, and 114. Their claims about Notorious are found on pp. 53-58. The quotation from their earlier piece can be found in “Embodying Movies: Embodied Simulation and Film Studies,” Cinema: Journal of Philosophy and the Moving Image (2012) 3: 188.

The crucial experiment is documented in Katrin Heimann et al., “Moving Mirrors: A High-Density EEG Study Investigating the Effect of Camera Movements on Motor Cortex Activation during Action Observation,” The Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience (2014), 26,9: 2087-2101. with the discussion of involvement coming on p. 2097. The Marco Iacobobi citation comes from Mirroring People: The New Science of How We Connect with Others (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008), 5.

Pinker’s remarks about mirror neurons and empathy are to be found in The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (Penguin, 2011), 577. The quotations from Dan Shaw are from “Mirror Neurons and Simulation Theory: A Neurophysiological Foundation for Cinematic Empathy,” in Current Controversies in Philosophy of Film, ed. Katherine Thomson-Jones (Routledge, 2016), 148, 151.

André Bazin discusses The Little Foxes in “William Wyler, or the Jansenist of Directing,” in Bazin at Work, ed. Bert Cardullo (Routledge, 1997) 3, 4. A blog entry here supplies further thoughts on the famous scene, which DB also analyzes in On the History of Film Style.

Donald Spoto discusses Hitchcock’s working methods in The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock (Da Capo, 1999; Centennial Edition), 284-287. David Ansen’s strictures on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein appeared in “Monster Mush,” Newsweek (6 November 1994). More on Notorious is here.

During the current health crisis, Berghahn has made all issues of Projections: The Journal of Movies and Mind freely available. Several articles over the years debate issues around cognitive film theory and brain-based explanations of media effects. Malcolm Turvey has made many contributions to Projections; see especially his book review here.

2001: A Space Odyssey.

Posted in 1940s Hollywood, Directors: Hitchcock, Directors: Hou Hsiao-hsien, Directors: Preminger, Film theory, Film theory: Cognitivism, Narrative: Suspense |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Can the science of mirror neurons explain the power of camera movement? A guest post by Malcolm Turvey open printable version

| Comments Off on Can the science of mirror neurons explain the power of camera movement? A guest post by Malcolm Turvey

Wednesday | April 29, 2020

Summer at Grandpa’s (Hou, 1984).

DB here:

This is another phantom entry I posted as Private for the seminar I’ve been teaching this term. I’ve opened it up for a wider audience because some readers have written to ask for access to the ideas. These are comments based on assigned reading for the course. Just as important, this entry serves as an introduction to a guest post coming up next week from Malcolm Turvey.

An earlier phantom entry, which considers how critics interpret a movie’s themes, intersects with this one. This is no less wonkish than that was.

The course has been an examination of the theory and practice of a particular perspective on studying film, the poetics of cinema. A poetics of any medium tries to study the principles undergirding the craft (technê) of artistic work in that medium. These principles may be explicit rules, or guidelines steering the makers’ decisions. But poetics can also reasonably try to trace how those principles and practices are designed to shape effects on perceivers. (For film, let’s call them spectators, but they of course listen as well as watch.) What are some fruitful ways to think about effects?

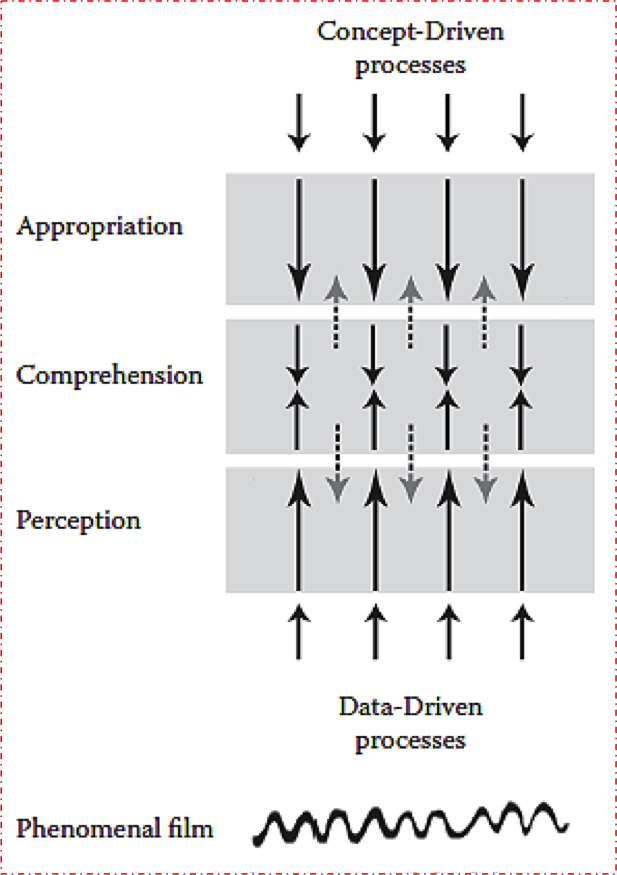

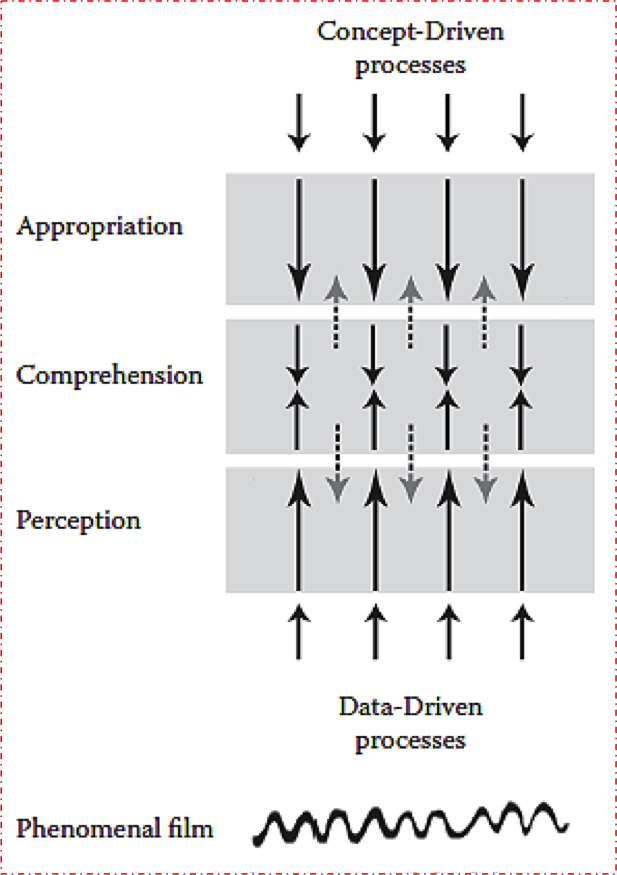

My initial stab at this was the bottom-up/top-down diagram of viewer activity.

To recap: As viewers we have capacities that are data-driven (bottom-up); these yield what we normally call perception. That’s already a huge range of activities, carried out mostly below the level of consciousness. (You can’t watch yourself registering color wavelengths.) In film viewing, perception runs from very fast, encapsulated, specialized, and “dumb” systems, like the phi phenomenon and apparent motion, to somewhat slower (but still fast and involuntary) ones like object recognition, speech recognition, and the like.

The top-down processes, which I called appropriation, are concept-driven, more voluntary, more deliberative, and more extensively funded by experience. A prototypical case would be judging a movie good or bad, or picking a clip to show in class. Interpretation, which I considered in this entry, is a common act of appropriation in the film-viewing community.

In the middle zone are what I called activities of comprehension. A prototypical example is following a story. It’s data-dependent (I can’t make Jackie Chan into James Bond) but it’s also concept-dependent (I can identify the conflicts and combats in a martial-arts film because they make the plot advance in a conventional manner). In non-narrative filmmaking, other comprehension skills come into play, drawing on knowledge bases, heuristics, and the like. You need some experience of art and life to follow the poetic fishing documentary Leviathan.

I wanted to allow feedback too, so the dotted lines in the middle try to suggest how comprehension can fund certain aspects of perception. We recognize Jackie Chan as likely to be the hero, and this concept helps steer our attention to him in his shots. Comprehension of course also funds appropriation, as when after grasping the film’s story we pick it apart in analysis.

One implication, already touched on in the interpretation entry, is this: As we go up from perception to appropriation, the filmmaker’s control wanes and the viewer’s control increases. Spielberg structures Raiders of the Lost Ark the way he wants, but you can appropriate his movie as a piece of imperialist ideology and he can’t do a damn thing about it. In the middle, it’s a negotiation: He steers you to construct the story a certain way, but you can also fill it out with your own inferences, or claim he hasn’t given you enough cues to do so. (Does Marion really love Indy? How much?)

And emotion is involved at all stages of the process, from the jolt of jump scares to the high-level social satisfactions of fandom.

Functions and inferences

This model was an attempt to be naturalistic—that is, in accord with what the special sciences currently know about how viewers’ minds work—but minimally so. This is an important point. This is a functionalist account. That is, it’s largely indifferent to how the processes are manifested in physical mechanisms. This model was an attempt to be naturalistic—that is, in accord with what the special sciences currently know about how viewers’ minds work—but minimally so. This is an important point. This is a functionalist account. That is, it’s largely indifferent to how the processes are manifested in physical mechanisms.

Think of all the vending machines you’ve encountered in your life. Each one yielded you those tasty snack treats in a predictable way, but there are different designs and materials. There are those drop-down machines that usually clamp your wrists when you try to reach into their pilfer-proof trenches. There are the little-window ones, which rotate the goodies into place (sometimes). There are even ones that use claws or turntables. And the bits and pieces can be made of plastic or metal, while the gearing and electronics and the machinery for grabbing your money (and denying your change) can be widely varied. But all in all, they have the same basic function and purpose: to take your payment and give you something deliciously unwholesome.

In the same way, my model of the spectator is agnostic about how the processes are instantiated in physical stuff. Doubtless retinas and neurons and inner ears and the nervous system are involved, but I’m not providing the details. I have no idea how to do so. Maybe we should think of the mind as having a core-periphery topography with outward-facing systems (the senses) as discrete modules picking up data while “central systems” supply the top-down treatment. Or maybe the mind is just a tangle of wetware, wires running all over the place, with “higher” functions jammed against, or crisscrossing “lower” ones.

I leave sorting all that out to the experts. But in terms of functions, I think it’s fair to say that most psychologists let the bottom-up/top-down metaphor capture distinct sorts of activities, however they are manifested in our senses, brains, and nervous systems.

More controversial is my argument that these activities are inferential in nature. This signals my commitment to New Look thinking, the early cognitive trend launched by Jerome Bruner, R. L. Gregory, Noam Chomsky et al. Computational models of mind emerged from this research. Nobody doubts that in the comprehension and appropriation phases, inferences are involved. Understanding a story or interpreting a movie as sexist clearly relies on inferences, “going beyond the information given.” The tougher controversy comes with perception.

Following Helmholtz, who believed that perception was “unconscious inference,” the information-processing perspective holds that perception is inference-like. It is defeasible. My eyes can fool me, as with mirages and the bent-looking stick in the pond. This is one reason New Look psychology is interested in illusions.

Moreover, perception operates with assumptions, just as inferences do. Many perceptual assumptions may not be learned but rather “innately specified” to some degree–that is, as presets. It seems, for instance, that we are evolutionarily “wired” to expect light to come from above. It’s also very advantageous for us to be able to separate figure from ground and tell living things from nonliving ones. These basic perceptual acts are funded not only by experience but by presets that steer us in a certain direction. No blank slate here; lots of veins and grooves. And given that we enter a structured ecosystem at birth, rich and flexible innate dispositions can be tuned to information pickup during a critical period. Babies learn fast because they’re primed to set the switches.

This perspective is usually contrasted with the view that holds that perception is “direct.” Most famously, J. J Gibson held that “the information is in the light.” Thanks to evolution and our mobility as creatures, we don’t need any elaborate inferential activity. The input is so redundant that we reliably detect the features of the environment automatically.

I think that the Embodied Cognition theorists are somewhat akin to Gibson in their belief in minimally mediated sensory pickup. Admittedly, though, as Gregory Hickok suggests in The Myth of Mirror Neurons, the Embodied Cognitivists do seem to have a computational side in treating mirror neurons as supplying “representations.” And one strain of Embodied Cognition, identified with George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, denies the inferential and computational model but still adheres to conceptual schemes (like metaphors) as representations of bodily experience. So some categorical, mediating inferences seem to play a role.

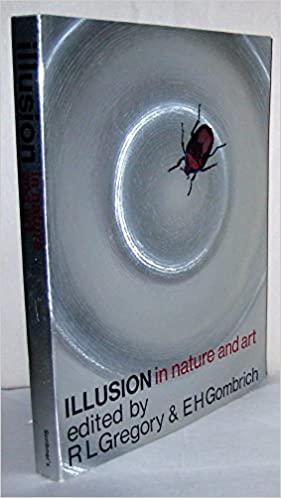

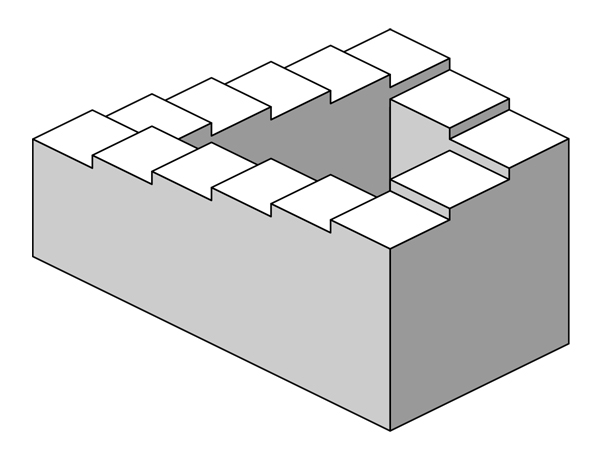

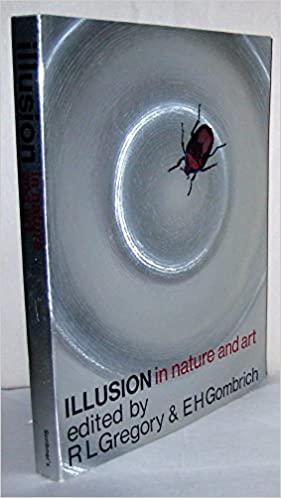

The next section discusses how New Look thinking can help us understand visual arts. My comments target two essays in the 1973 collection Illusion and Nature and Art: R. L. Gregeory’s “The Confounded Eye” and E. H. Gombrich’s “Illusion and Art.”

Gregory, Gombrich, and art

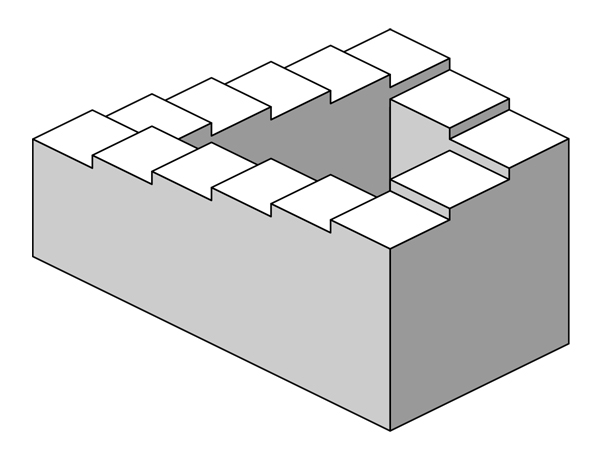

The Penrose steps.

New Look psychologist Sir Richard Gregory (lower right) was a passionate connoisseur of illusions like the Penrose stairsteps. He was famous for pushing the cognitive model of inference-making very far, deep into the basics of perception. He saw perceptions as the usually reliable results of assumptions and hypotheses, in a process significantly similar to what scientists do when they launch hypotheses and check for confirmation. For a career overview, go here.

I take it that he’s trying to answer the question: What perceptual processes generate visual illusions? We evolved to pick up accurate information from the environment, and normally our perception is accurate. The obvious problem with illusions is that they yield false information. What has fooled our eye?

Gregory’s essay “The Confounded Eye” offers a detailed set of explanations, divided between mechanism failures and misplaced strategies. In cinema, a clear mechanism failure would be apparent motion. Movies trade on a failure of our visual system to detect single frames that are still images. As we didn’t evolve to watch movies, and as we don’t encounter this sort of intermittent illusory motion in a state of nature, inventors found a way to trick our eye and create the impression of movement. Gregory’s essay “The Confounded Eye” offers a detailed set of explanations, divided between mechanism failures and misplaced strategies. In cinema, a clear mechanism failure would be apparent motion. Movies trade on a failure of our visual system to detect single frames that are still images. As we didn’t evolve to watch movies, and as we don’t encounter this sort of intermittent illusory motion in a state of nature, inventors found a way to trick our eye and create the impression of movement.

As for perceptual strategies, perhaps in film we could cite special effects and green-screen backgrounds, where perspective, lighting, focus and so on are calculated to suggest space that isn’t really in front of the camera. Our visual system assumes regularities of space that aren’t justified; we usually can’t force ourselves to see these backgrounds as flat.

Some controversies dog Gregory’s theory, chiefly in his reliance on prior experience. He thinks that even pretty low-level outputs depend on knowledge of some sort, if only about our world of discrete edges and solid shapes. He doesn’t seem to treat evolution as shaping many of our perceptual proclivities. In this essay “The Confounded Eye,” he appeals to classical conditioning (p. 66) to get the system off the ground.

But crucial are the ideas we also find in the work of E. H. Gombrich. Gregory assumes an active perceiver, one who takes fragmentary stimuli as cues for building up a perceptual conclusion, through a process of hypothesis-testing. Expectation, assumptions, and probabilities all play a role. Perception is inferential because it can be wrong.

In addition, Gregory reminds us of the importance of habituation (sometimes confusingly called “adaptation”). This means simply resetting the threshold of your sensory input. At first the coffee shop seems noisy, but soon enough you’re paying no attention to it and completely sensitive to your partner’s whisper. People can even adjust to wearing eyeglasses that turn the world upside down! Habituation is perhaps the most robust finding in all of psychology—and something that, when it becomes all-powerful, Victor Shklovsky deplores. (“Habitualization devours works, clothes, furniture, one’s wife, and the fear of war.”)

Gregory’s last book, the cleverly titled Seeing through Illusions (2009), published a year before his death, is a detailed expansion of these ideas. He classifies dozens of illusions according to a richer scheme than the one laid out in his 1973 article.

There’s a lot more in Gregory’s essay, not least the homunculus argument which has been broached against a lot of cognitive theorizing (mine included). But now let’s look at Gombrich’s essay “Illusion and Art.” He was a friend of Gregory’s and he borrowed heavily from New Look psychology.

Despite the book’s title, Gombrich’s magnum opus Art and Illusion doesn’t center on illusion as such. In trying to answer the question Why does [European representational] art have a history? he had to confront “illusionistic” styles, but that issue was secondary to the larger issue of continuity and change in representational traditions. So with an essay called “Illusion and Art,” Gombrich offers a more explicit and careful account of illusion.

I take it that his guiding research question is something like How may we explain the artistic and psychological processes that generate illusion in the visual arts? Not surprisingly, he will make use of some of Gregory’s ideas.

What seem to me crucial here are Gombrich’s reflections on animal perception. Far more than in A & I, he posits a continuum of sensory appeals and so a sort of spectrum of degrees of illusion. To a considerable degree, he has turned my vertical diagram into a horizontal one.

There are automatic, involuntary processes he calls “sensory triggers.” Moving along the spectrum, there are more elaborate strategies for conjuring up illusion, but these will rely on more deliberative processes. Throughout, we never lose the sense that we are watching a representation, however realistic it looks.

Moreover, Gombrich attributes the fast and mandatory illusions, the ones Plato called “lower reaches of the soul,” to evolution. He posits that just like other creatures, we have sensory systems that respond to “triggers” automatically, and sometimes we can be deceived–as predators are fooled by the camouflage of their prey.

So what about illusions? At one end is pure delusion, as with say counterfeit money. Trompe l’oeil is a little further along; you really have to get close to detect the difference. Flat objects, like letters tacked to a board, are good for this trickery, as are fictitious postage stamps like those of Donald Evans.

These cues are very realistic, but crucially the trigger need not be a close replica of what it represents. Approximation can work. The duckling can follow a moving brown box if it moseys like its mother; the box doesn’t look like Mom, it just triggers the Mom-response. Stickleback fish will strike a red cloth that doesn’t look much like another fish’s belly–except in being a moving patch of red. Recall as well the Frog Multiplex. These critters are slaves to innate “action programs.”

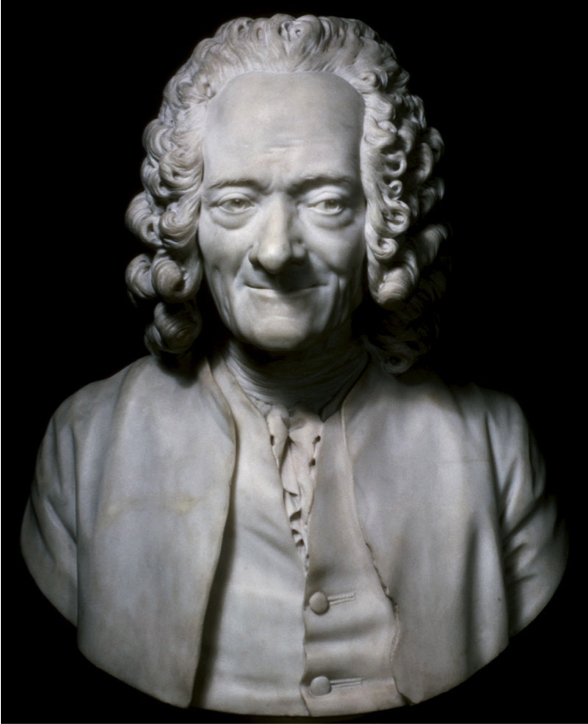

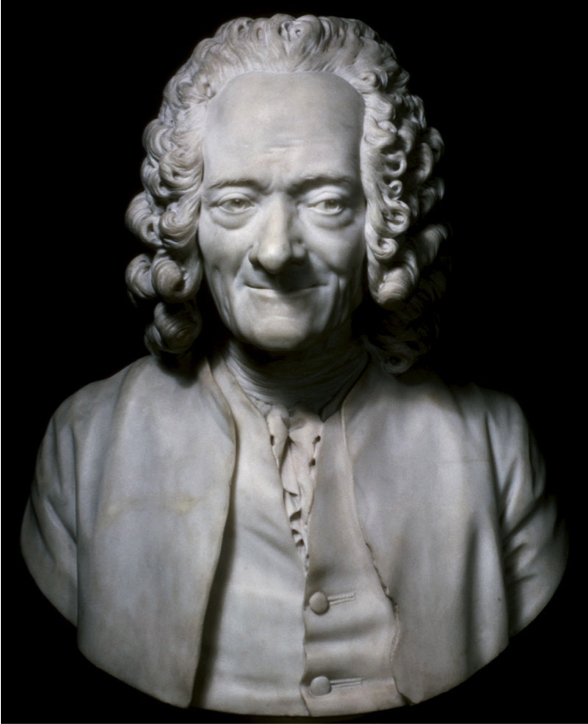

A flat, impoverished display of a wiggling worm is enough to get the right (wrong) reaction. And note a fascinating Gombrich example, Houdon’s bust of Voltaire, where the sparkle in the eye is actually a tiny lump protruding from the surface. You couldn’t get farther from a non-realistic device for depicting a gleam of light.