Archive for the 'Special effects and CGI' Category

Harry Potter treated with gravity

Kristin here:

Going into the summer movie season this year, I wasn’t particularly excited about most of the upcoming films. I was looking forward to Monsters University, which I thoroughly enjoyed, though it didn’t return to the dazzling levels of Pixar’s films before Cars 2. Right now I’m assembling my viewing list from the impressive array of offerings at the Vancouver International Film Festival. (The new Oliveira! Godard in 3D! Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s long-awaited return to filmmaking!)

But I’m also aware that during the festival, another film that I’m really excited to see will be released in North America: Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity. I didn’t see the 17-minute opening shot shown at Comic-Con, but I watched one of the trailers, and it was the most exciting new piece of filmmaking I’ve seen this year. If you haven’t seen one of the four trailers, you can watch them on Warner Bros.’s site, or on any number of video and infotainment sites. The one called “Drifting” reminded me of Michael Snow’s brilliant Central Region, but with narrative, with the earth and stars spinning past a close-up of Sandra Bullock as the marooned, panicky astronaut protagonist.

Unfortunately a still frame conveys almost nothing of the dazzling effect of this image. You’ll just have to follow the link above and look for yourself.

Judging by the ecstatic reviews and descriptions of audience responses that came out after Gravity was screened as the opening-night gala at the Venice Film Festival, the movie lives up to the expectations generated by the clip and trailers. One of the most insightful reviews is by Todd McCarthy, who combines giddy enthusiasm (mentioning twice that people will want to see the film repeatedly) with some solid analytical comments on the soundtrack, camerawork, and special effects. After Cuarón screened the film for James Cameron, the latter enthused: “I was stunned, absolutely floored. I think it’s the best space photography ever done, I think it’s the best space film ever done, and it’s the movie I’ve been hungry to see for an awful long time.” Indiewire’s Steve Greene has compiled a selections of excerpts from reviews from the Venice opening.

Cuarón’s previous film had been Children of Men, released way back in 2006. After such a gap, authors of articles and reviews have felt the need to summarize his career briefly. Most frequently they mention Children of Men and the 2001 Mexican comedy Y tu mamá también, which was a breakthrough film for the director. Less frequently there is a reference to Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004) and A Little Princess (1995).

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban in Cuarón’s career

Living paintings in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azakaban

As that line-up of titles suggests, Cuarón has had a career that makes him difficult to characterize. Although he is perceived as a Mexican director, he has done relatively little work there. Apart from shorts and TV projects, his Mexican features consist only of Love in the Time of Hysteria (Sólo con tu pareja, 1991) and Y tu mamá también. He’s also perceived as an art-film director. Variety′s cover story on Gravity was entitled “An Auteur’s Re-entry” in the September 3 print edition (though it was “Alfonso Cuaron Returns to the Bigscreen after Seven Years with ‘Gravity’ online). This impression obviously arose from the success of Y tu mamá también (distributed in the USA by Good Machine, now Focus Features) but also from the fact that the grim Children of Men was a financial flop and succès d’estime. Yet Children was produced and distributed within the Hollywood mainstream by Universal.

Instead of pursuing his career in Mexico, Cuarón headed for Hollywood immediately after his first feature. He described this career move in a 2006 interview:

After coming up the ranks as a cable operator on a movie set and an assistant director, he made his first feature, “Sólo con tu pareja,” in 1991, and it won several awards at the Toronto Film Festival. However, the Mexican Film Commission, which had subsidized it, wasn’t happy with the movie.

“I basically burned my bridges with the commission,” says Cuarón, who moved to Los Angeles with no contract to do another film. Director-producer Sydney Pollack gave him a chance to shoot an episode on the cable TV series, “Fallen Angels.”

“Tom Cruise had directed one episode and Tom Hanks another. But mine was the one that won a cable award,” Cuarón says. “It was one of those things that led to the next.”

That turned out to be the sublime children’s movie “A Little Princess.”

“I never watch my movies after I’m done with them, but in my memory that’s the one I love the most,” he says.

Cuarón’s next experience directing a modern-day version of “Great Expectations” [1998] starring Gwyneth Paltrow and Ethan Hawke, wasn’t so great.

“My instinct always told me not to do it, and I ended up doing it anyway,” he says. “So I learned to trust my instinct.”

Also in this interview, Cuarón describes himself as lucky in his Hollywood work:

That a major studio (Universal) was willing to underwrite such a downbeat story [as Children of Men] is a credit to Cuarón’s reputation. Unlike many foreign directors used to having enormous latitude in their native countries, Cuarón has learned to work within the Hollywood system.

“There is a tendency to see Hollywood like Darth Vader trying to destroy filmmakers,” he says. “And I’m sure that’s sometimes true. I have been very lucky to be able to create my own stuff without studio interference.”

The perception of Cuarón as an art-film director has perhaps led to a tendency to dismiss his one venture into the Harry Potter series as an aberration. In his excellent analysis of the long takes in Children of Men (which focuses on the fact that they were created by digitally blending multiple takes), James Udden remarks on how, after first using long takes in Y tu mamá también, “Next, Cuaron takes a ‘step back’ in a sense with Prisoner of Azkaban, paying yet more ‘dues’ to the system.” Justin Chang’s brief but informative survey of long takes in Cuarón’s work does mention that the technique “even reared its head in 2004’s ‘Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban,’ in which the director boldly imprinted his personality onto one of Hollywood’s most successfull–and most risk-averse–franchises,” though he does not mention how the technique “reared its head.”

Yet Cuarón evidently loved his experience working on Prisoner of Azkaban. The interview just quoted was one of several in 2006 where he expressed keen interest in making another film in the series: “If I’m invited, I would be very tempted to direct it. The idea of revisiting that beautiful universe is irresistible [….] Everything that happens around a J. K. Rowling creation is enveloped in this beautiful, beneficial energy.” Maybe he will have a chance to work on a Rowling film again, given the recent announcement that she will write the script for a franchise-starter for a new film series based in her wizarding world.

Setting aside Cuarón’s feelings about his experience making the film, we should not dismiss it as a minor part of his career, something he supposedly made so that he would be able to make other, more personal projects. For a start, it does have a style distinctly different from the other Harry Potter films. It’s not always recognizable as a Cuarón style, but then, Cuarón’s films are so different from each other that that is hardly surprising. Udden points out that while Children of Men has an average shot length of slightly over sixteen seconds, Prisoner of Azkaban′s ASL is about 5.5 seconds. Still, it contains three long takes, each of considerable interest. Moreover, the introduction to cutting-edge CGI would leave Cuarón with valuable experience that he could apply to his two subsequent features.

Prisoner of Azkaban has a reputation as one of the best, if not the best, of the Harry Potter films. Its quality is not solely due to Cuarón’s direction. The book is arguably also the best of Rowling’s series. While the first two books (Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone and Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets) are pleasant, entertaining children’s stories, Prisoner of Azkaban marks a leap in the complexity and depth of the plotting. It adds two major new characters, the sympathetic professor (and werewolf) Remius Lupin and the apparently threatening Sirius Black, who turns out to be Harry’s parents’ best friend and his godfather. It also adds a third character, the dotty Prof. Trelawney, who seems just to offer a source of comedy but will eventually prove to have affected Harry’s life in unsuspected ways.

New villains also appear, notably the soul-sucking Dementors and the literal and figurative rat, Peter Pettigrew, another old friend turned traitor who has become Voldemort’s main helper. Lupin introduces the technique of casting a “patronus,” a protective figure of light that repels the Dementors–something that will continue to be crucial for the rest of the series. Finally, there is the ingenious episode of the time-turner, a device Hermione has been employing to take multiple classes at once but which she ultimately uses to allow her and Harry to go back in time and manipulate a series of tragic events and make them end happily. This lengthy scene, one of the high points of Rowling’s series, is even better in the film, where we can see the doubled characters on the screen.

Apart from drawing on the book’s strengths, the film also has the advantage of being the one that replaced Richard Harris with Michael Gambon as Dumbledore. Apparently some viewers were fond of Harris’ portrayal, but the casting seems to me a real mistake and no kindness to an actor clearly in failing health. I found him disturbingly feeble, stiff in his movements and expressions, and barely able to get a whole line out without gasping for breath. How the producers thought he could last through the series is a mystery, and Gambon’s livelier and funnier performance came as a relief.

Prisoner of Azkaban also quickly gained a reputation as being much darker in tone than the two films that preceded it. I doubt there was a single reviewer who failed to make this claim. The Washington Post’s critic called it “everything the first two films were not: complex, frightening, nuanced.” For Roger Ebert, “Harry’s world has grown a little darker and more menacing.” In a later survey of the first four Harry Potter directors, Manohla Dargis and A. O. Scott wrote of Prisoner of Azkaban, “the tone and color palette have shifted, the bright, flat lighting giving way to a somber and dangerous feel, evocative of horror films.”

Perhaps such comments had something to do with the fact that Prisoner of Azkaban earned less at the box office than any other film in the series: a mere $797 million. (The second lowest earner, Chamber of Secrets, made $879 million; the highest, Death Hallows Part 2, $1.3 billion.) It’s hard to believe that fewer people would go to the film based on a change of directors. How many, after all, would be likely to know who Cuarón was? More likely parents kept younger children away for fear that the action would be too intense.

The book version of Prisoner of Azkaban also takes a much darker turn. If that was the reason for the downturn, it didn’t last long. The trend toward darker, scarier content continued through the later books, with the return of Voldemort in the fourth and the deaths of major characters in each subsequent book. Similarly, the later films are distinctly more grisly and frightening than Prisoner of Azkaban. None of this kept people from buying books and movie tickets.

One might assume that studio executives decided on Cuarón as an appropriate director for a darker entry in the series, but he had not yet gained a reputation for grim subject matter. That came with Children of Men. In fact, Cuarón was not the first or even second choice as the film’s director. A retrospective article on Den of Geek! gives this account:

The studio’s choices included Guillermo del Toro, who baulked at how the film was “so bright and happy and full of light”, and Marc Forster, who didn’t want to direct children again so soon after making Finding Neverland.

It came down to a final short-list of Kenneth Branagh (who had co-starred in the previous instalment as Gilderoy Lockhart), Alfonso Cuarón (A Little Princess) and Callie Khouri (Divine Secrets Of The Ya-Ya Sisterhood and screenwriter of Thelma And Louise). Eventually, Cuarón was appointed, and the director is largely credited with energising the series.

Let’s examine some of what Cuarón brought to Harry Potter by looking at his signature device, long takes.

Three long takes and some flashy effects

Unlike in Children of Men, the long takes in Prisoner of Azkaban are not used primarily for action scenes. Unlike in more conventional Hollywood films, they are not used at the opening as a flashy way of presenting exposition. Rather, they function to emphasize transitional points in the plot and to create motivic parallels. Not surprisingly for Cuarón, all involve camera movements. Two of the three involve conversations, one with an impressive but not flashy tracking movement to follow the characters, the other with a more subtle, slow push-in and out.

The first and lengthiest of the long takes comes in the Leaky Cauldron inn when Harry encounters the Weasley family and Mr. Weasley takes him aside to warn him about Sirius Black’s escape from Azkaban prison. It lasts for one minute and 53 seconds.

The setting is bustling, and the camera movement serves in part to gradually pull attention away from the crowded dining room and to focus on the conversation. The shot opens on the busy table, with a large tea kettle floating on its own through the air. (In Prisoner of Azkaban, Cuarón frequently uses this tactic of having objects floating in the foreground to suggest a magical environment; he will repeat the device in Gravity to depict weightlessness in space). Mrs. Weasley effusively greets Harry:

Mr. Weasley asks to have a word with the boy, and they move toward a squared-off opening near the back of the set. A wanted poster for Black, visible to the right of center from the opening of the shot, becomes more prominent at the frame edge. Since photographs in this magical world move, we cannot help but notice it:

The camera tracks past the poster through a second opening closer to the camera and stops once the characters are centered. Mr. Weasley tells Harry about Black, and the camera moves back to accommodate them when they come forward to look at the poster:

As they continue to talk, the camera again moves backward as Mr. Weasley steers Harry to a third opening into the main dining room. They pause beside a second poster of Black, and Mr. Weasley explains that Black had betrayed Harry’s parents to Voldemort, who had killed them and tried to kill him. As a man in a bowler sits at the table near them, Mr. Weasley again guides Harry into a more private area:

He says Black is going to try and kill Harry and urges Harry not to go looking for him. The shot ends on a push in toward Harry, who replies, “Mr. Weasley, why would I go looking for someone who wants to kill me?” and the scene ends.

This moment marks a crucial change in the narrative tone. The film started with two comic scenes: Harry’s use of magic to inflate his obnoxious Aunt Marge into a human blimp and then the antics of the fantastical Knight Bus that rescues Harry and transports him to the Leaky Cauldron. Now for the first time the theme of grave danger is introduced, with the insane-looking Black screaming silently in the wanted poster. A darker storyline takes over, though there are many moments of humor to come. This conversation leads into the scene on the train to Hogwarts, which, for the first time in the series, has a heavy rainfall occurring throughout. During this scene the first Dementor appears, and Lupin explains what Dementors are.

The second long take (one minute and thirty seconds) comes in a much quieter scene at Hogwarts. Harry has been unable to accompany the other students on a day’s outing to Hogsmeade, the local village, and he is depressed and lonely. He has a conversation with Lupin, set on a long elevated bridge that was added to the Hogwarts setting for this film. The scene begins with an extreme long shot tracking slowly toward the bridge as Harry discusses his fear of Dementors with Lupin, followed by a cut-in to them:

The camera moves in slowly as Lupin turns away and recalls his friendship with Harry’s mother. As he says, “Well, your father James, on the other hand, he … he had a certain, shall we say, talent for trouble,” Harry smiles:

Lupin walks back to Harry, concluding, “A talent, rumor has it, he passed on to you. You’re more like them than you know, Harry. In time you’ll come to see just how much”:

The scene ends with a cut to a shot of the bridge from the original distant framing:

The two scenes are parallel but contrasting, as Harry receives information from two father figures. Initially he speaks to Mr. Weasley, the head of a large, boisterous family that has semi-adopted Harry; we are reminded of them (including Ginny, whom Harry will eventually marry) at intervals in the background of the Leaky Cauldron long take. The two rooms are divided by a series of square openings in a thick wall, which the pair move through as Mr. Weasley prepares to deliver threatening news. The melancholy Lupin, on the other hand, has no family, and here he comforts Harry in a setting with airy, intricate archways framing a vast, empty mountain vista beyond. The quiet atmosphere is appropriate, since Lupin is the first of three classmates and close friends of his dead parents that Harry meets in this film.

The film’s third long take is the only one that could be said to involve an action scene, though it is really just the prelude to a lengthy segment of the film stringing together several brief action scenes. (It is the shortest of the three long takes, at one minute and eight seconds.) This shot marks another transition, introducing the film’s climax. Everything has just gone wrong. Gamekeeper Hagrid’s pet hippogriff Buckbeak has been executed as too dangerous to be around the students. Sirius, whom the children now know to be innocent of the crime for which he was imprisoned, has been captured and is about to be turned over to the Dementors. Pettigrew, having been revealed as the true traitor to Harry’s parents, has escaped in rat form. In the hospital dormitory where Ron has ended up, Dumbledore hints that Hermione should use the time-turner so that she and Harry can return to the beginning of these events and try to reverse them.

The camera circles around Hermione as she turns away from Ron’s bed and pulls the time-turner on its chain from inside her jacket. She lifts it and places the chain around Harry’s neck, so that they are both wearing it:

He looks on uncomprehendingly as she twirls the time-turner to send them back to a point shortly before the scheduled execution of Buckbeak:

Startled, Harry watches rapid changes in lighting and blurred figures moving backward in fast motion as Hermione keeps track of how far they have traveled. During all this, Ron disappears from the bed at the right rear:

The camera moves in as she hides the time-turner and circles as they run out of the room:

They run along a corridor, the camera following until they turn and exit left:

The camera continues straight ahead, through the large clock wheels, and reveals the school grounds far below:

The camera moves through the glass of the clock window and tilts down to the courtyard, where Hermione and Harry emerge and run out through the doorway at the top of the screen:

Later, after the pair has accomplished their goals, a somewhat similar shot moves with them through this same courtyard and cranes up and through the clock again, joining them at the same point as they run in and away down the corridor to the hospital wing.

On a more modest scale, there is a somewhat similar technique used in Y tu mamá también. The heroine, Luisa, waits in her apartment for Tenoch and Julio to pick her up for a trip to the beach. Once they call to let her know they have arrived, she exits through the front door; the camera tracks rightward to a window and tilts down to reveal the car waiting below and pulling away from the curb as the three depart. Although not a particularly lengthy shot, it functions, as in the third one from Prisoner of Azkaban, to mark a narrative transition, in this case the end of the film’s first portion and move into the long car trip that will occupy most of the rest of the film:

This is a far simpler shot and was accomplished by moving the handheld camera through the room to an open window, sticking it through, and tilting down. The Prisoner of Azkaban “shot” was in fact an elaborate manipulation of images, with the segment where time runs in reverse around Harry and Hermione shot against a green screen; the portion going through the clock’s works and its window was done with CGI elements. (See American Cinematographer‘s article on the film for an explication of the technology involved.)

Admirers of the elaborate “camera movements” in Children of Men and Gravity, some of which were done by stitching together several elements into apparently continuous shots, might take note that Cuarón’s experiences on Prisoner of Azkaban made them possible. A 2006 interview on SFGate describes the director’s progress:

One benefit was a crash course in computer-generated visual effects. Cuarón used “maybe a shot or two in “Y Tu Mamá También”–the 2001 Mexican indie that got him an Oscar nomination for best original screenplay–and in his earlier Hollywood movies, “A Little Princess” and “Great Expectations.”

On the Harry Potter sequel, working with computer effects was “like speaking Russian,” he says. The hardest part was figuring out how to shoot an object such as a plate, knowing that later it would be substituted by some wild effect.

“The important thing was not to be shackled by these effects, to shoot as you would your normal scene. There’s a tendency I witness in movies and completely dislike in which the narrative is kind of forced because of the visual effects. You have to try to keep your character and the visual-effect character as separate as possible.”

By the time he started “Children of Men,” all of this was “like second nature.”

In a more recent (undated) interview given at the time when Gravity‘s principal photography was beginning, Cuarón stressed its connection to the things he had learned about special effects on Prisoner of Azkaban: “Well, Potter was my kindergarten and grammar school and high school and college education of visual effects. It is coming in handy with Gravity which is so, so visual-effects savvy [that] we’re inventing new technologies. Now it’s just second nature.” He also mentions that his work with David Heyman, who produced all the Harry Potter films, was what led him to invite Heyman to produce Gravity.

Apart from the CG-compiled long takes, there were effects like the hundreds of candles floating in the air above the great dining hall of Hogwarts (see top) and the living paintings crowding the walls (above left). It seems remarkable that Cuarón’s third film after his modest Mexican sex comedy could draw such high praise from James Cameron, one of the top directors of effects-heavy films, but working on a Harry Potter movie for a couple of years made that possible. And, as the frame below demonstrates, directing Quidditch matches is a good preparation for showing people drifting weightlessly in space.

The quotation from James Udden comes from his article, “Child of the Long Take: Alfonso Cuaron’s film Aesthetics in the Shadow of Globilization,” Style 43, 1 [Spring 2009]: 40. For those with access to a research library, this issue is available on ProQuest and other online archives.

Beyond praise 5: Still more supplements that really tell you something

Real-time performance-capture images for The Adventures of Tintin.

Kristin here:

The Extraordinary Voyage (2011, Serge Bromberg and Eric Lange)

I had expected to follow up my entry on Hugo when the DVD was released. I anticipated that its supplements would explore the flashy technical and artistic aspects in detail. But the lengthy first chapter proved to be largely the cast and crew presenting variations on how lucky they were to have worked with Martin Scorsese (and each other) and how much they learned from him.

That wasn’t promising, and I turned instead to Georges Méliès himself. Flicker Alley, which has served the filmmaker so well in the past (see here), has recently released the restored color version of A Trip to the Moon in a Blu-ray/DVD combination set. It is accompanied by a 65-minute documentary on the Méliès, the film, and the restoration. It’s odd to call a 65-minute film that accompanies a fifteen-minute “feature” a supplement, but I recommend it anyway.

I suspect that The Extraordinary Voyage would be quite effective in easing students into very early silent cinema and intriguing them about an era that must seem hopelessly remote to them. It begins with a charming introduction to the context of the turn of the previous century and then moves quickly into the director’s young-adult life. When it comes to the famous incident in which Méliès’ camera jammed while he was filming, creating an inadvertent magical transformation, the filmmakers have an actual 1937 recording of Méliès himself describing the event. Presumably this was the original source of this oft-repeated anecdote. He specifies that it happened on the Place de l’Opéra and involved a bus turning into a hearse. I still wonder if it all happened so neatly, but hearing it directly from Méliès makes it a little more plausible. If it wasn’t true, it should have been.

The film includes as talking heads several filmmakers who admire Méliès’ work: Costa-Gavras, Jean-Pierre Jeunet, Michael Gondry, Tom Hanks, and Michel Hazanavicius. There is a good summary of the fascination with the moon in popular culture of the day,  including works by Jules Verne, Jacques Offenbach, and H. G. Wells.

including works by Jules Verne, Jacques Offenbach, and H. G. Wells.

The documentary touches on issues relevant to early silent cinema in general. One of these is the frequent pirating of films, with Méliès starting an American branch of his Star Films in New York, under the direction of his brother Gaston, to help protect his intellectual property. A clip from the Segundo de Chomon version of the film, An Excursion to the Moon, is included.

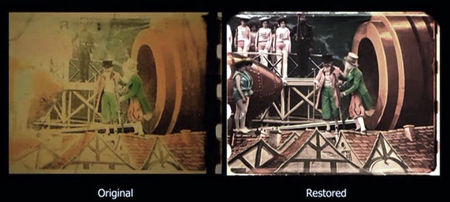

At about 23 minutes in, a short overview of early movie music is given, followed by a helpful explanation of how the hand-coloring of Méliès’ films was handled by a local workshop run by women. At 30 minutes in there are several dazzling examples of hand-colored scenes (right).

After a quick summary of Méliès’ decline and death, the film moves to the restoration of the only known hand-colored copy of A Trip to the Moon, found in the film archive in Barcelona. Here the hero is Tom Burton, the Director of Technicolor Creative Services, who gives a brief indication of how computers have transformed restoration:

We have a palette of digital tools to work from that are a collection of maybe five or six of the main commercially available restoration platforms, but then we also bring into the mix all of the approaches that you would use if you were doing visual effects for a modern movie.

The comparison of visual effects with restoration is in some ways an apt one and might lead students to look upon early films in a new light.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (Blu-ray/DVD/Ultraviolet set, Sony Pictures Home Entertainment)

It’s probably a good idea to supply both Blu-ray and DVD discs in one package, but including the supplements only in Blu-ray is annoying and increasingly common. That’s the way the Girl with the Dragon Tattoo discs have been handled. Teachers without access to a Blu-ray player have fewer options when trying to use supplements in teaching. It also makes it much more difficult to make frame grabs from the supplements to, say, illustrate a blog entry on useful supplements.

I decided to check out the supplements for this film because the ones for Zodiac and The Social Network were so good. I figured David Fincher was particularly concerned about his films’ bonus materials. Unfortunately this set of supplements is quite uneven. The cast and crew seem to be obsessed with the character of the heroine and with the delights of shooting in Sweden. I confess that I stopped watching some of the chapters as the talking heads went on and on about these subjects. Some of the tracks also consisted of a lot of candid behind-the-scenes footage, which is all very well, but there was little structure to this and only occasional comments to explain what was going on.

Fortunately the “Post-Production” section is very informative and interesting. “In the Cutting Room” is fairly technical but makes some fascinating points. I particularly liked the description of how Fincher eliminates reframings and unsteady shots by using the extra image space allowed by newer capture media. (Earlier digital film frames allowed no extra image area outside what would show up on the screen; as the image below indicates, the final frame can be selected from a larger picture.) This desire for a stable image in an era where the “queasi-cam” so often rules points to one distinctive trait in Fincher’s style. It indicates a willingness to actually think through the framing of each individual shot and the purpose for choosing that framing. Steven Spielberg does the same thing. Many don’t.

Editor Angus Wall talks about this advantage of the extra size of the image and how Fincher uses it to stabilize unsteady images. It’s worth quoting at length, and it demonstrates the thoughtful commentary in this particular supplement:

I’ve never seen a movie that was sort of “re-operated” to the extent that this one was. Which I think has an effect on the viewing of the movie. David is really type-A in terms of making the shots very specific. They start in a certain way, they end in a certain way. And the framing, he’s very precise in terms of his composition. He doesn’t like a lot of what you see in 99% of movies, which is very subtle moves where the operator will actually reframe according to how the actor’s moving. David doesn’t like that. Even if there were a lot of those in this film, and before, some of those takes we would have thrown out, because we just wouldn’t have been able to stabilize them to the degree that he likes it. With this, because you have this full raster, this big area around the image, you can take those images and stabilize them, really lock them down. So the movie is really locked down in terms of camera operating. More than any other movie that I can think of.

The smooth glide as the car initially approaches the country house is one example of that utter stability, used to ominous effect in that particular scene.

There’s also some interesting discussion about how the two main characters don’t meet each other until well into the film and how that affected decisions about editing. Rather than frequently intercutting between Mikael Blomkvist and Lisbeth Salander, the filmmakers decided to create longer self-contained scenes involving each, thus switching back and forth less frequently. The idea was that the exposition set forth in each scene would be too difficult to absorb if it was chopped into smaller segments. Form, style, and function, neatly explained.

Fincher also points to an interesting underlying anxiety the spectator might feel because the narrative progress gives little sense of how much action is still to come:

You don’t know where you are in the narrative. You don’t know if you’re at the beginning of the third act or … I don’t think it’s bad, because we have a five-act movie. I think that’s what’s causing everybody’s anxieties, that it doesn’t feel like, OK, here’s where we are, we’re entering the third act now. Now it feels like, fuck, this movie could go on … indefinitely. That’s the part that’s bothering me. If we told them it was going on for another forty-five minutes, they wouldn’t have a problem. It’s the indefinite part.

Since I’ve written a book claiming that classical films usually don’t have three acts, I was intrigued by this statement. (See also my earlier blog entry here and David’s essay here.) I posit instead that classical films typically create acts that run about 25 to 30 minutes, and that the film’s length determines how many acts it has. Four acts is the most common throughout Hollywood’s history, but a 158-minute film would be likely to have five acts. (Has David Fincher read my book?!) His point about the audience feeling a bit lost in an unconventional narrative structure is a rare instance of a director talking about form in such an abstract way, and it seems quite valid for The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

It’s also rare to get a supplement on ADR (automated [or additional] dialogue replacement), but there’s a six-minute one in the “Post-Production” section. This consists of a behind-the-scenes session with Rooney Mara supplying not just dialogue but breathing, grunts, and other noises. It’s clearly a real session, not a staged one, though the actress does seem a bit self-conscious with the documentarian’s camera turned on her. Fincher’s and Mara’s banter between takes gives a sense of what I suspect really goes on during this phase of production.

There’s a brief supplement called “Main Titles,” which deals with the form and inspiration for the CGI under the titles. Fincher wanted to tell the story of the whole trilogy in two and a half minutes, “and it has to be spectacular.” Apart from the discussion of form, there’s a good look at unrendered CGI footage compared to the finished images.

Finally, an eight-minute “Visual Effects Montage” displays a variety of special effects in a clever way. There is a section at the beginning where we are shown the image without added effects, then the same image with the areas to be altered highlighted in various superimposed colors, and finally the finished images with the effects added. This is particularly good for showing the sorts of mundane effects that are used to enhance shots unnoticeably, adding cars’ headlight beams, reflections in glass, falling snow, and the like. There is a shot with a section of a building on location blotted out with a greenscreen and the final shot showing the use of alterations in the building:

Obviously here the fog was also added with CGI.

This montage goes very quickly. If you’re using it in a class, best to prepare ahead and be ready to pause and point out what’s going on in the many short shots used in the demonstrations.

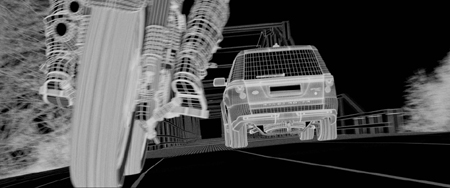

The second half of the effects montage moves to splashier scenes of the type the public associates with “special effects”: wire-frame vehicles for a chase (see image at the top of this section), head-replacement to add Mara’s head to her stunt-double’s body, and explosions.

Don’t bother with the “Stockholm Syndrome” section. Basically all we learn is that when a scene is shot on location, sheep can unexpectedly wander in and interfere.

The Adventures of Tintin (Blu-ray/DVD/Digital Copy combo, Paramount Pictures)

Again, the supplements for this release are available only in Blu-ray.

Steven Spielberg and Peter Jackson decided some years ago to collaborate on what was announced to be a three-film series adapted from Hergé’s Tintin comic books. The notion was that each of them would direct one film, with an as-yet-unspecified director doing the third. Spielberg’s initiatory film did not do as well at the domestic box-office as had been hoped, though it fared better in Europe and other non-North American markets, where the comics are highly popular. Jackson has announced that after he finishes both parts of The Hobbit, he will launch into the next Tintin film. (At least, that’s what he said originally. After yesterday’s announcement that there will be three Hobbit films, his start on the Tintin film will presumably be delayed.)

The supplements form a narrative of the film’s making, bookended by “Toasting Tintin” and “Toasting Tintin Part 2,” brief episodes set at the launch and wrap parties. The tale is pleasant and generally worth watching, though they are far from as entertaining and informative as the supplements that Michael Pellerin produced and directed for Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings and King Kong DVD sets. But this is Spielberg’s show, since he did the first film and indeed originated the project. At first he envisioned the film as live-action, with the dog Snowy the only major CGI character. Spielberg asked Jackson’s effects house Weta Digital to do some tests animating Snowy. To his (apparent) surprise, Jackson himself, as a fan of the comics since childhood, played Captain Haddock in the test. That fact was well known to fans, and the inclusion of the test footage (above) is no doubt a crowd-pleaser.

The decision to use cutting-edge performance-capture techniques led to the film being entirely animated.

“The World of Tintin” gives background on Hergé and deals briefly with the screenwriting process. This leads into “The Who’s Who of Tintin,” dealing with characters and acting, with some good material on performance capture near the end. The next section, “Tintin: Conceptual Design” has good material on the visual style of the characters and near the end includes some pre-viz material.

The outstanding supplement, however, is “Tintin: In the Volume,” nearly 18 minutes of footage concerning performance capture. Spielberg’s role as director was primarily concentrated into a remarkably short 31-day shoot with the actors. This was done in a state-of-the-art performance-capture facility called “The Volume” and located at Giant Studios. The Volume is a large space with about 160 cameras built into the ceiling and pointing down into the performance space. These capture the space from multiple angles. Additional cameras on the stage level follow the actors’ movements, which are inserted into the space. Moreover, hand-held monitors similar to portable gaming devices allow the filmmakers to see simple versions of the settings and the partially rendered characters while pointing the device at the actors in their performance-capture rigs.

There are also larger monitors that show the actors their own performances translated into the characters (top of entry). Whatever one thinks of the look of contemporary animation of this type, the technology has evolved to a remarkable level, and this supplement provides an excellent explanation of the practicalities of performance capture. We see the motion-capture suits being put on and the dots painted onto the actors’ skin. There is also information on how the set elements and props need to be transparent so that the cameras can capture the dots on the actors’ faces and costumes through them. The image at the bottom shows Jamie Bell as Tintin looking at a mock-up of the model ship. It’s made of little metal rods and rendered into a ship on the monitors.

“Snowy: From Beginning to End” is less cutesy than it sounds. It discussed the digital tool developed for modeling the dog’s fur. There’s also good stuff on how several dogs were recorded to provide different-sounding barks depending on the type of action in a scene.

The biggest tasks on the film came after the performance capture and editing. Weta Digital spent two years creating the final images. “Animating Tintin” is an excellent eleven-minute account of that process.

The sections “Tintin: The Score” and “Collecting Tintin” (on Weta Workshop’s designs for the collectible figures) are rather thin and could be skipped unless a teacher wants to show the whole set of supplements as a single “making-of” documentary.

It’s become apparent that many of the best supplements on Blu-ray and/or DVD releases are devoted to special effects, especially performance capture. The Adventures of Tintin does genuinely involve innovations in this technology, and the “In the Volume” chapter is very informative. Supplements are getting repetitive, though, and I would like to see the producers of such documentaries pay more attention to techniques and choices in other areas. Comparing final cuts of scenes with earlier cuts, or showing story conferences where real debates about scripts occur (as was done in the first Pirates of the Caribbean film’s supplements), or displaying how decisions about digital-intermediate grading are made–a bit of imagination could spice up the offerings. That and a realization that film fans are interested in just about any aspect of production (or distribution, for that matter). Supplements risk falling into conventional patterns, and that won’t make them the appealing bonus material that they used to be.

While I was gearing up to write this entry, we received Mark Parker and Deborah Parker’s book, The DVD and the Study of Film: The Attainable Text (Palgrave, 2011). Based on a great deal of research, including many interviews, the authors include a summary history of DVDs and supplements; there is a detailed chapter on The Criterion Collection, interviews with directors and scholars who have recorded commentary tracks, and a case study of Atom Egoyan.

Three minutes of “Three Brothers”

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1

Kristin here:

Last wee I went to see Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1. Behind the pack, of course, since it had been out nearly a month. But I dislike watching films in a crowd. My ideal is to be alone in the theater, which David and I managed last week with Megamind. In this case I picked the first matinee on a school day and saw the film at our local Sundance multiplex. (Yes, even Sundance runs some popular films to help support the less successful art films.) I figured that noisy youngsters, even if they skipped school to see DH1, wouldn’t go to Sundance. I was right. Four or five adults were sitting about ten rows behind me. I never heard a peep or crackling candy wrapper out of them. The film was really film, too, 35mm.

I had been curious about how the filmmakers would deal with some of the stranger aspects of J. K. Rowling’s seventh and final book. Breaking it into two parts seemed an obvious and smart move, and it does have less of a rushed feeling than the previous adaptations had. But Deathly Hallows the book has some very unconventional aspects.

For a start, Rowling reveals dark, indeed downright nasty things alleged about Albus Dumbledore, who up to this point has been your standard-issue comic-but-wise, twinkly-eyed mentor figure. I wondered if the film would dare to do the same. It does, but so far only as a very minor side issue. In the first part, at least, Harry is obviously distinctly miffed that Dumbledore hasn’t left him more information about how to deal with horcruxes, but he doesn’t seem to feel that his hero had feet of clay.

Second, it seems downright perverse on Rowling’s part that in a long series which has come to focus on the search for horcruxes and should just be working up its climax, she throws another set of mysterious, lost objects, the three Deathly Hallows, at us. Let’s see, six horcruxes, three hallows. What’s the difference? Which should the characters be seeking, and why? Is Voldemort after them, too? In the book, Harry becomes obsessed with finding the hallows, even though the horcruxes are the main point. That last premise, Harry’s obsession, hasn’t shown up in the film, so far anyway, but otherwise the hallows are fully treated in the film.

Finally, Rowling gives us a very long portion of the book where Harry, Hermione, and, for a time, Ron, are fugitives moving from place to place, camping out each night as they try to figure out where the remaining horcruxes are—and not having much luck either with that or with destroying the one they have obtained. I personally think this is a rather daring move. Given that for this long section we are confined entirely to Harry’s point of view, we get little sense of what is happening in the outer world. Naturally the film can’t spend quite as much of its length on this period of nomadic existence. Still, it does devote an unexpectedly long time to portraying it.

Some critics have complained that the action stalls during this portion. Others have noted that the slow-down allows for us at last to linger over the psychological states of the three main characters, who are being worn down by fear, frustration, and the horcrux’s presence. This stretch also displays some beautifully bleak locations, well filmed. Plus, as Rowling no doubt intended, this part of the narrative conveys a real sense of the characters’ seemingly hopeless position: They are in great danger and without any apparent clue as to where to look next.

One minor obstacle that I remember noting when I first read the book is that the hallows are introduced by having Hermione read aloud a fairy tale from the book Dumbledore has bequeathed to her, The Tales of Beedle the Bard. The tale, “The Tale of the Three Brothers,” occupies only about two pages, but having someone read that much text aloud in a film can be deadly.

The filmmakers came up with a solution that is both inspired and extremely well executed. As Hermione reads, we see a roughly three-minute animated sequence that illustrates her words.  The filmmakers have acknowledged that their model was Lotte Reiniger’s technique of silhouette animation, which she developed in the 1920s and used for such classics as The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926). For DH1, similar silhouette effects are achieved with 3D digital animation.

The filmmakers have acknowledged that their model was Lotte Reiniger’s technique of silhouette animation, which she developed in the 1920s and used for such classics as The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926). For DH1, similar silhouette effects are achieved with 3D digital animation.

I wondered who had designed and animated this little sequence and determined to watch for references to it in the credits. As is typical with effects-heavy films these days, several companies were listed and the credits rolled by too quickly for me to catch much. Still, I don’t think that the little film-within-a-film was mentioned specifically or its creator named as having been attached to it. Even Variety‘s review, which refers in passing to the sequence, doesn’t mention its maker.

A lot of other viewers were impressed enough to try and find out who was responsible. DH1 was released in the US on November 19, and by the next day, Cartoon Brew posted a story on the subject: “A number of readers have written to ask who animated the shadow puppet-inspired ‘Tale of the Three Brothers’ sequence in the new Harry Potter film Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. It was directed and designed by Ben Hibon who produced it in association with Framestore.” Surprisingly, it also turns out that the section of Framestore that normally makes commercials did the “Three Brothers” scene.

I spent some time tracking Hibon down, finding some good-quality frames to display here, and locating clips. There are a few interviews with Hibon, plenty of clips and entire shorts, and filmographies. The video quality of some of these clips is dreadful, though, and a lot of the stories one finds via Google are short, repetitive pieces.

Most of this material is not all that easy to find, so herewith a guide to where you can most usefully find information on someone who seems to be an up-and-coming talent.

Hibon has designed video games, made music videos and commercials, done a short “screen” for MTV, and directed a few shorts and a trailer for a feature, A.D., which seems still to be in progress. The fullest filmography is the official one on the website for Hibon’s own company, Stateless Films.

Animation and effects expert Bill Desowitz has interviewed Hibon for Animation World Network. That’s recent, December 3, and deals exclusively with the DH1 scene. On November 23, fxguide posted an interview with Dale Newton, the sequence supervisor for the piece. An older, undated interview with Hibon on It’s Art Magazine concerns the series of five two-minute shorts collectively known as “Heavenly Sword.” These relate to a video game of the same name that Hibon designed. This series is visually quite distinctive, but it’s a far more conventional work than the “Three Brothers” short, being heavily influenced by anime.

Also on November 23, indiewire posted a short background article on Hibon, with several videos. With one exception, which I’ll get to shortly, don’t watch these films here or on YouTube. Why? Because the Stateless Films site has most of them and more. Hibon’s clips are larger and better quality than anything else I checked, plus they’re displayed with a black screen and far fewer distracting graphics than on YouTube. Click on the Archives link to see older works, including samples of Hibon’s work on videogames.

His site is the only place where I found a full version of his ad for the French bank, Crédit Agricole. The point of the ad is that this is the first green bank. It’s a gorgeous piece, full of images of pollution and decay gradually giving way to scenes of places restored to their pristine state and new, clean technology in place. Here are some images, from a vertical descent downward through a series of jet-trails (at bottom), a shot in which a wall of identical canned goods suddenly flies away to reveal a street market with fresh produce on sale, and windmills replacing old factory chimneys that fly apart:

There’s a dream-like quality to the whole thing, with a lot of shots, many with rapid movement, juxtaposed with slow, stately music.

The indiewire clips linked above include two shortened, English-language versions of this ad, with Sean Connery appearing to make the message explicit. There are also some Crédit Agricole ads made by more conventional filmmakers. Watch one or two of those, and you’ll find the contrast dramatic.

None of these sites and others with Hibon clips or shorts has the “Three Brothers” sequence, not surprisingly. That is, YouTube has some horrendous, out-of-focus subtitled auditorium videos, made in perhaps a South American or Spanish theater. Avoid like the plague.

Framestore’s site has some information on Hibon’s sequence, and the only clip from it that I could find. It’s very small and too dark to render the subtleties of the visuals, but there it is. Framestore also animated the two house-elves, Dobby and Kreatur, and there’s some information on that part of the project as well.

The January, 2011 issue of Cinefex has a story on DH1 that will undoubtedly include a section on the “Three Brothers” animation, but I haven’t seen that yet.

One reason that there are so many short pieces on Hibon on the internet is that at almost exactly the same time, on November 22, Variety announced that the filmmaker had been signed to direct a long-dormant New Line project, Pan. It’s a variation on the Peter Pan story, with the roles of villain and hero being switched; here Captain Hook is a detective on the trail of a certain child-kidnapper. The studio acquired the project in 1996, and for a while it looked as though Guillermo del Toro would direct. This time the film might get made, since the Variety story reports that it’s being cast and should start shooting next fall.

Beyond praise 3: Yet more DVD supplements that really tell you something

Darby O’Gill and the Little People (1959)

Kristin here–

Every now and then I discuss a few DVD supplements that teachers might find useful for their classes, though they might be of interest to others as well. Previous installments can be read here and here.

Darby O’Gill and the Little People (Walt Disney Video)

Yes, you read that right. I can’t claim credit for having discovered this disc’s excellent supplement, “Little People, Big Effects.” Shortly after the second “Beyond praise” entry, Dan Reynolds, who teaches at the University of California Santa Barbara, wrote to recommend it.

Darby O’Gill was one of the few Disney live-action films I missed when I was growing up in the 1950s. I acquired the disc and started by watching the feature. I must say that this is one weird movie.

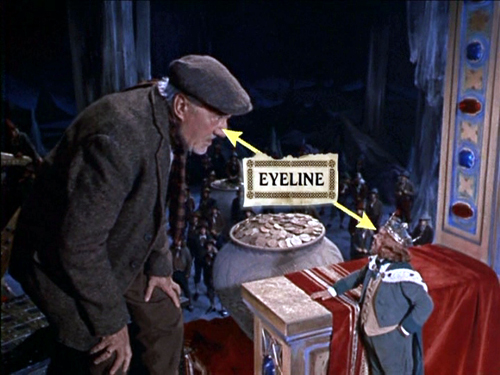

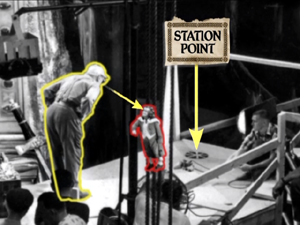

The “little people” of the title are leprechauns, and the special effects used to make them look small are mostly achieved through forced- perspective techniques. In less than eleven minutes, this supplement demonstrates the use of glass paintings, mattes, false perspective, and even a revived Schüfftan process, most famously used for Metropolis, where scale is manipulated by shooting into an angled, partially transparent mirror. Careful calculations allow for over-sized sets in the background to be lined up precisely with normal-scale ones in the foreground, so that the foreground person looks much larger then the background one. Since the two characters, here Darby and King Brian, are supposed to be conversing face-to-face, a manipulation of eyelines, a term we use a lot in Film Art, is necessary. (Despite what my spell-check keeps trying to tell me, “eyeline” is one word in the movie business, as demonstrated above.) In explaining how the actors knew where to look in the shot illustrated at the top, the film shows that “station points” were placed on the floor so that the characters’ eyelines would seem to match up (below). These days actors alone against blue or green screens often have to look at tennis balls to make the direction of their gaze match correctly.)

Clearly some behind-the-scenes footage was made during the production of Darby O’Gill, and this is incorporated into a documentary that includes interviews with master effects expert Peter Ellenshaw, who died in 2007. Ellenshaw worked as a matte painter on half the British classics of the 1930s and 1940s, including Black Narcissus (which has perhaps the greatest matte paintings ever). He then moved to Hollywood in 1950 and began a string of films with Disney that won him an Oscar for Mary Poppins. It’s good to have even these short clips of him demonstrating and discussing his work.

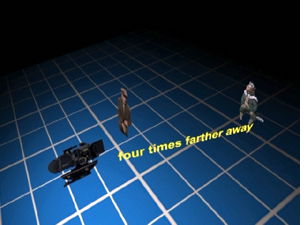

“Little People, Big Effects” should give students (and just about anyone else) a better grasp of perspective and its importance in the representation of depth on a flat screen. I would definitely show it as part of a study of cinematography. If a fifty-year-old film seems a bit out of date, point out to students that, as the narrator mentions, exactly the same techniques were used in many scenes of The Lord of the Rings to make the hobbits and dwarves look small. Similar demonstrations are provided in the supplements to the extended DVD version of The Fellowship of the Ring (Disc 1, “Visual Effects: Scale”).

Elijah Wood sits further from the camera than Ian McKellen in order to make him appear as small as a hobbit

Zodiac (“2-Disc Director’s Cut,” Paramount)

At the end of my first “Beyond praise” entry, I complained about the lack of supplements on the initial DVD release of Zodiac. Then, after the two-disc set with the supplements appeared in early 2008, I forgot to include it in the second entry. Better late than never, so I’m tackling it here. (The supplements are apparently the same for the Blu-ray set.)

As the “DVD Talk” review says. “The self-congratulatory praise is kept to a minimum.”

The main supplement is a 53-minute film called “Deciphering Zodiac.” It’s a good, objective, chronological summary of the film’s production. A lot of talking heads are included, such as the producer, scriptwriter, set decorator. That’s usually a good sign, since it shows that care was taken with the making-of and that enough of the crew members are participating that the account will probably be rounded. There’s a 15-minute making-of specifically on “The Visual Effects of Zodiac.”

Zodiac was primarily shot on professional-level digital cameras, apart from the slow-motion shots, which still need to be done on 35mm due to limitations of the digital technology. Hence there’s a lot of information here on digital techniques. Most of these techniques are used in ways that aren’t necessarily obvious to the viewer. If you want to show students some material on digital effects, this might be a good choice, since it avoids the flashy, obvious effects that so many fantasy and sci-fi DVD supplements concentrate on.

“Deciphering Zodiac” has shots showing the digital camera attached to an elaborate rig around a car, which was used to follow moving cars, including the famous opening tracking shot along a suburban street. The video-assist monitor is often visible in the shots.

One change that digital filming has made in production has been the frequent use of “digital dailies” rather than dailies on film. (Dailies are the unedited takes just as they come from the camera(s); directors and other key creative people typically watch them at the end of each day.) Several scenes of the “Deciphering” documentary show raw shots and are labeled as digital dailies, something which doesn’t seem to be a common feature of supplements. It’s pretty obvious that the shot of Jake Gyllenhaal below would need to be manipulated in post-production. There’s also informative coverage of the methods used to match location and studio-shot footage, particularly for the scene where the killer shoots a taxi driver.

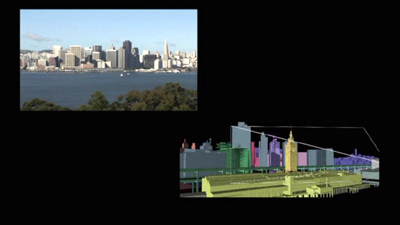

The visual effects documentary has good explanations of the early shot of a rapid move across the bay toward San Francisco as it looked in the period when the film’s action begins, a shot that was done entirely digitally.

Now that so many best-lists for the decade have included Zodiac, it seems to be an official modern classic. Perhaps a somewhat more dignified way of teaching special effects than using a Transformers movie.

The Dark Knight (Two-Disc Special Edition, Warner Home Video)

The supplements for The Dark Knight make a nice contrast with those for Zodiac. Here the makers of a spectacular action movie avoided digital special effects to a surprising extent. Instead they used practical effects, that is, effects accomplished via physical means while shooting rather than those done in post-production via laboratory or digital manipulation. Digital technology was used, of course, but often for rather modest tasks in planning and in erasure of unwanted elements. It’s also interesting as the first 35mm fiction feature to be shot partially on Imax cameras.

The main supplement is “Gotham Uncovered.” It begins by showing how the Imax camera was initially tested on a single action scene shot on location in Chicago. The results led to additional Imax scenes being added to the film. The advantages of Imax—primarily a huge gain in visual quality due to the larger size of the individual frames—are shown to be balanced against the camera’s limitations. The camera is much larger, making handheld shots difficult. It holds only three minutes of film and has a shallower depth of field. While interesting, this first section is surprisingly lacking in actual footage of the filming, often depending on still photos. We tend to assume that in this day and age, the making-of is taken into account from early on in a production. It’s surprising how often that turns out not to be the case.

A five-minute segment, “The Sound of Anarchy,” shows Hans Zimmer sitting at a computer and talking about the modernist, dissonant music for the Joker character. It’s mildly informative.

“The Chase” is perhaps the most useful section of the making-of. The decision was made to shoot the scene on Lower Wacker in Chicago. Here digital effects were kept to a minimum, with multiple cameras mounted on vehicles like the motorcycle below. These were special smaller Imax cameras. Only four such cameras existed at the time, though an accident reduced that to three!

One big moment in the chase has the Batmobile crashing into a garbage truck. Again, rather than resorting to digital effects, the crew built miniatures of the two vehicles and the set. The decision was also made to shoot a crash of an 18-wheeler on LaSalle Street using a real truck on location, and the scenes showing the practice sessions for this reveal the kind of planning that goes into the big action scenes that are so common in films these days.

A multi-vehicle crash scene was done with several cameras, which is common practice for unrepeatable actions. (Even on a big-budget film like this, no one would want to crash more than one Lamborghini.) The cameras often show up in each other’s shots, and the supplement shows the resulting footage and how CGI is later used to erase them—again, a very common use of digital tools. Here a camera on a crane is visible at the center left in the original footage of the crash:

In one scene, the Joker walks out of a hospital, which explodes behind him. A prime candidate for digital effects, one would think. Instead, the filmmakers opted to have a demolition company destroy a real building. CGI was used to plan the scene:

A shorter supplement, “The Evolution of the Knight,” deals mostly with the design process for Batman’s suit and the Batpod. Again the emphasis is on bringing reality into the filming. It’s pointed out that while much of Batman Returns was shot on sound stages, the team decided to try and shoot the sequel in the city streets as much as possible.

Beware of these

I have to admit, one reason that this series appears so rarely is that for every DVD with useful supplements that I find, there are two or three uninformative ones that I have to sit through–or at least sample. In addition to recommendations, let me warn you away from some of the ones I switched off.

I had expected the Slumdog Millionaire DVD extras to be interesting, given the mixture of digital and 35mm shooting, the location work, and so on. But obviously the filmmakers had no idea that the film would be a success, so they seem to have done little behind-the-scenes shooting as they made it. The result is a not terribly informative, bare-bones 18-minute making-of.

Supplements as praise-fests have not gone away. Musicals seem especially to bring them out. “Get Aboard! The Band Wagon” provides 36 minutes of mutual admiration. In “From Stage to Screen: The History of Chicago,” Chita Rivera unintentionally achieves a parody of the gushing movie star who lauds everyone she worked with.

David and I just watched Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs. I had liked it when I saw it in first run, and predictably, David enjoyed it, too. It’s a clever, well-scripted, well-animated film. We hoped to learn something from its supplements, but the making-of seems to be aimed at children, and young ones at that. The co-directors and some of the other filmmakers look distinctly embarrassed to be participating, partly because a lame comparison of making a film to mashing food together forms a running motif. A pity, since the movie deserves better. As reviewers keep pointing out, the best animated films these days are made for adults as much as for children.