Archive for the 'PANDORA’S DIGITAL BOX: The Blog Series' Category

PANDORA’s digital book

DB here:

Looking back at Kristin’s and my ventures online, I see a gradually expanding series of experiments. Step by step, maybe too cautiously, we’ve moved toward what you might call “para-academic” film writing–a way of getting ideas, information, and opinions out to a film-enthusiast readership whom we hadn’t reached with our earlier work. (Although we’re happy when academics take note of what we do.)

Today we have a new experiment to try. Pandora’s Digital Box: Films, Files, and the Future of Movies is now available here. Backstory follows.

Baby steps, then longer ones

To take another metaphor, we’ve been gradually exploring various niches in the online ecosystem. At first, back in 2000, knowing almost nothing about cyberculture, I dumped my vitae and a little essay onto my brand-new Geocities site. Later I saw the site mainly as a supplement to print publication, a way to add and correct things I’d written in my books Figures Traced in Light (2004) and The Way Hollywood Tells It (2005), along with material we’d included in our textbooks Film Art and Film History. By then I had retired from teaching.

I started to write more online. I began posting long, stand-alone pieces that I couldn’t imagine any journal or anthology publishing. (They’re in the list on the left-hand column of this page.) Somewhere around 2007, after finishing the collection Poetics of Cinema, I made Web publishing my primary expressive vehicle. So when I was asked to write pieces for various occasions, I tried to secure permission to publish them here as well. They too have wound up in the line-up on the left– a little essay on Paolo Gioli, one on Shaw Brothers’ widescreen cinema, and a liner note about The Mad Detective for the Masters of Cinema DVD line. There are more to come in this vein, including a historical survey of how film theorists have drawn ideas from psychological research.

While moving to fill the essayistic niche, we saw archival and revival opportunities as well. Thanks to Markus Nornes, I was able to republish the out-of-print Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema in a downloadable pdf version, with color illustrations. That’s on the University of Michigan Press site. Vito Adiraensens, who made a pdf of Kristin’s Exporting Entertainment, allowed us to post that on our site.

At this point, whole books we’ve done were available online. But those were straight reprints. The next logical step was to offer a revised edition. After the rights to Planet Hong Kong (2000) reverted to me, I decided to update and expand it and add color illustrations. I also decided to ask for money, making PHK 2.0 the only item on the site that wasn’t free. That was an experiment too, to see if the year I spent reshaping it might yield some payback. It did; so far, the sales have covered the costs of design and yielded me a little for my efforts.

Meanwhile we’ve explored the blog niche. Started in 2006, refreshed once or twice a week, our blog has become greatly satisfying to us. This entry is number 499. We’ve treated the blog wing of the site as a sort of magazine, with each entry as a feature or column or festival report or book notes. We write about anything cinematic, old or new, that interests us. The freedom is exhilarating, and we don’t lack ideas. I have a desk drawer’s worth of folders on topics I want to explore.

Nearly all of these are long-form endeavors. Some run to 6000 words. Even our festival reports, which could have been emitted in a flurry of communiqués, are blended into spacious pieces that permit us to compare films or develop a common theme. At a time when everyone declares that attention spans have shrunk to pinpoints, readers have been very patient with us. People still visit our blog, recommend it to others, and even Facebook and Tweet about it. Roger Ebert has been an especially generous supporter. Thanks to the efforts of Rodney Powell of the University of Chicago Press, we gathered some of our entries into a book, a “real” one called Minding Movies, and I’d hope that the length and contextual depth of the pieces gave them some bookish solidity.

Another niche coming up: As virtual books have found a public, I’ve made a book designed primarily for an e-reader.

Not bloviation, blogiation

Last fall, after realizing the scope of the digital conversion of movie theatres, I decided to write a series of blogs about it. I had no fixed number in mind, but I didn’t expect it to run as long as it did. I kept learning more, so the series, called Pandora’s Digital Box, stretched from December through March. I was encouraged by people who praised it in blogs and on social media. I decided to try to build a book out of the pieces.

Some people think that this is silly. One reviewer of our blog book, Minding Movies, wondered why anyone would buy something that’s available for free. More alert reviewers, like Scott Foundas of Film Comment (May/June 2011), understood that some readers don’t like to read long-form prose online, or don’t like zigzagging through the labyrinth that is our site, or want some guidance in selecting what to pay attention to. Moreover, by gathering items topically, the book suggested recurring themes and an overall frame of reference governing what we do. The broad aims of our enterprise aren’t apparent in a daily skim of each entry.

Still, Minding Movies was a varied mixture. Pandora was from the start a more focused series. And we added no new essays for our collection, but I had quite a bit more to say about the digital conversion. So I cooked up new rules for my latest experiment.

1. The original entries wouldn’t be taken down. As with Minding Movies, the entries will remain available online.

2. The book wouldn’t be simply a blog sandwich. I’ve rewritten, rearranged, and merged entries for smoother reading. The topics are more logically ordered, and the whole thing hangs together organically. The blogs formed a kaleidoscope; the book is a narrative.

3. The book would have lots of new material. It includes things I didn’t know when I wrote the blog, ideas that have come to me since, and as much background and context as I could supply. The original blogs amounted to about 35,000 words (enough for a Kindle single). The finished book runs over 57,000 words.

4. It wouldn’t be an academic book. It’s written in the same conversational tenor as the blog. I try not to make anybody’s head hurt. No footnotes, but….

5. The book would exploit online access. The text is unsullied by links, to promote continuity of reading. But a section of references in the back contains citations and hyperlinks to documents, interviews, sources, and sites of interest. This section tells you where I got my information and, if that information is online, takes you there.

6. The book would have to be for sale… Part of this experiment is to see whether I can make back what I’ve spent on the project. I reckon that my travel to theatres and events like the Art House Convergence in Utah, along with other expenses like paying our Web tsarina Meg to polish up my self-designed Word book, comes to about $1200. In addition, I’d like something for my extra time and effort.

7. …but not cost too much. Planet Hong Kong 2.0 runs $15, which I think is a fair price given the cost of designing a book with hundreds of color pictures. But Pandora is a lot simpler and has only a few stills. So I’m offering it for much less: $3.99.

Another Whatsit, but only $3.99

Pandora’s Digital Box: Films, Files, and the Future of Movies traces how the digital conversion came about, how it affects different sorts of theatres, how it shapes the tasks of film archives, and what it portends for film culture, especially the culture of moviegoing.

A key concern was trying to go beyond what I’d already written. For one thing, I try to answer questions I didn’t pursue in the blog entries. How did the major distributors orchestrate the transition? How did they reconcile the interests of the various stakeholders—filmmakers, theatre owners, manufacturers? By 2005, the specifications for digital cinema were established, but the real uptake came five to six years later. What led to the delay? How was digital cinema deployed outside the US? And so on.

Second, I provide background and context for areas I surveyed quickly online. For example, instead of sketching how a movie file gets projected, I take you into a booth and we follow the process step by step. The chapter on small-town cinemas reviews the role of single-screen theatres in the industry. The chapter on art-house cinemas goes back to the 1920s and shows remarkable continuity of taste and business tactics up to the present. Throughout, I consider how the US exhibition system has worked since the rise of multiplexes.

Third, there are unexpected tidbits. How did celebrity directors like Lucas, Cameron, and Jackson spearhead the shift to digital and later innovations? (I touched on that in a couple of recent entries here and here, but there’s more in the book.) Who invented multiplexes? Cup holders? When did those annoying preshow displays start, and more important, who controls them? How do distributors decide whether to release a movie wide or to let it “platform”? Why do art-house theatres serve coffee? There are even a couple of jokes (maybe more unintentional ones).

I think it has worked out well. I’ve tested the text on Kindle, Nook, and the iPad, and it fits very snugly. You just have to import it as a pdf from your computer. On the iPad, it seems to work particularly well with the app GoodReader, which permits smooth searches, easy bookmarking, and quick shifts back and forth.

As I mentioned above, you can go here to order the book. On the same page you can examine the Table of Contents and a bit of the Introduction.

It’s possible that some people might want to make a bulk purchase. Pandora might be used in a class, or given to staff members working at a film festival, or presented to members or patrons of an art house. For such worthy purposes, I can make the bulk price quite low. If you’re interested, please write to me at the email address above.

Self-publication is a risk for both author and reader. If you decide to buy the book, I thank you.

The next logical steps? A new ecological niche? A completely original book online, maybe. Or PowerPoint lectures with voice-over. Who knows? As Jack Ryan says at the end of The Hunt for Red October: Welcome to the new world.

Thanks as usual to our Web tsarina Meg Hamel, who did her usual superb job turning Pandora the Blog into Pandora the Book, and who has set up the payment process to be quick and easy. Earlier helpmates were Vera Crowell and Jonathan Frome, whose efforts in creating this site are remembered and appreciated.

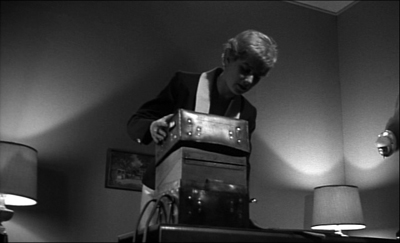

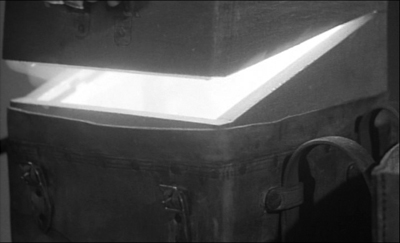

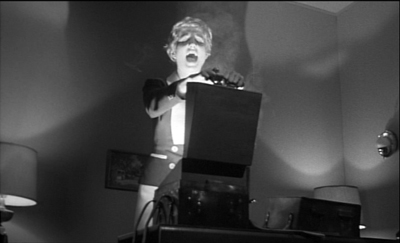

The illustrations are from Kiss Me Deadly and Pandora and the Flying Dutchman, but you knew that. Thanks to Jim Emerson for his suggestions.

Pandora’s digital box: Harmony

DB here:

I had thought I was finished with my series on digital projection that started back in December. That was before a late-night trawl of the Internets brought the JEM Theatre to my attention. Sometimes reality has a taste for a dramatic story, and this was one I couldn’t resist.

So I went to Harmony.

All in the families

A birthday party at the JEM Theatre.

For decades exhibiting movies has been a family business. Many regional chains were founded by fathers and brothers and staffed by sons, daughters, and in-laws. The Midwest’s Marcus chain of 700 screens originated in 1935 with grandfather Ben and is run by son Stephen and grandson Gregory. More modestly, Smitty’s Cinema, a nine-screen movies-and-eats circuit in Maine and New Hampshire, was the brainchild of three brothers.

The smaller the venue, the more likely you’ll find a family in charge. The Goetz Theatre of Monroe, Wisconsin, which I profiled earlier, has been in the family from the start. The single-screen Cozy in Wadena, Minnesota, has been run by the Quincers since 1923, with the founder’s great-grandson in charge today. Dirk and Jeri Reinauer have the Sunset Theatre in Connell, Washington. Tom and Barbara Budjanek, who bought Pennsylvania’s Ambridge Family theatre in 1967, are still running it in 2012.

Families pass theatres to each other. The venerable Roxy in Forsyth, Montana, was bought by a couple in 1967. They sold it to their projectionists, one of whom kept it going with his wife. (The theatre went digital in 2010, just in time for its eightieth birthday.) From 1947 to 1959 the Wayne Theatre in Bicknell, Utah, was operated by a husband and wife. Another couple bought it and ran it until 1994, when they sold it to a third husband and wife. A fourth family acquired it in 2008.

The record for husbands and wives running a single-screener might be held by the little town of Harmony, Minnesota. The JEM Theatre on the main street, closed in 1947, was reopened by Bob and Hazel Johnson in 1961. They ran it for twenty-five years. It passed through the hands of five more couples before Michelle and Paul Haugerud acquired it in 2002.

Paul and Michelle met in San Francisco, where Michelle was working for Bear Stearns and Paul had served in the Navy. In 1994 they moved to Harmony to be near Paul’s family. There they raised six children while Paul started a paint and drywall business and Michelle began a career in Web design. “When we bought the theatre,” Paul explained, “we knew it was gonna make no money. We knew it was gonna be basically like doing community service.”

To an extent that people living in cities and suburbs may not appreciate, the JEM has held a central place in the life of the town. By 2011, digital conversion threatened to end that.

Harmony, not far from Prosper

With a population of about a thousand, Harmony sits in farm country close to the Iowa border. As Prairie Home Companion reminds us every week, people of Norwegian descent are found all over Minnesota. What you may not know is that certain areas are also home to Amish communities. Waves of migration made Harmony a center of Minnesota’s Amish culture. Local businesses serve the five hundred households in the town, and tourism brings in some income too. One of the big attractions is Niagara cave, containing fossils pre-dating the dinosaurs. There’s also a major biking trail and a fall foliage tour.

The JEM was named, supposedly, for the first letter in the names of the original owner’s three children (but see the PS below). It helped knit the town together, and under the Haugeruds it became a unique institution.

They made a solid team, with Paul’s expertise in carpentry and engine repair matched by Michelle’s money-management skills. Paul, with no previous theatre experience, learned to thread up the platter projector. “The first few weeks, I would literally sit there with sweat rolling down my face as I pushed the start button. I’d be so nervous I did something wrong.” Paul introduced screenings with announcements and jokes. The Haugeruds knew most of their patrons, but at every screening there were fresh faces from nearby towns in Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin.

The JEM screened only on weekends, once each day at 7:30. Paul’s and Michelle’s day jobs made any other schedule impossible. During football season, Fridays brought in few teenagers, but Saturdays were better and Sundays were quite good. Overall, the 200-seat house averaged around 55 each night. On snowy nights, a few souls still braved the Minnesota winter to come see a movie.

The Haugeruds ran the JEM as a family business. There was no paid staff. The Haugerud kids sold tickets and snacks and helped with cleanup. Friends and volunteers came out as well. Michelle made the pre-show video slides of ads for local businesses. Even with low overhead, the theatre barely broke even. All tickets were $3. “We’ve always kept prices low,” Michelle explained, “so families that are financially hardshipped can still get their kids out of the house.”

Most of the JEM’s programs were subruns—movies that had opened nationally two or three weeks before. To avoid courier service costs, Michelle and Paul would make midnight drives to pick up prints from other towns. “I’d call and they’d just be breaking down their print from their last show on Thursday,” she says. “I’d say, ‘I’ll be there in fifteen minutes,’ and at midnight I’d go get the print for Paul to make up on Friday.”

Snack concessions are the core of every theatre’s income, but even here Paul and Michelle offered deals. They priced their candy at a dollar and a big tub of popcorn at four bucks. Soda was sold in plastic bottles, to allow for recycling and to keep costs down. Instead of getting concession items from theatre suppliers, Michelle bought them in bulk at Sam’s Club.

The JEM popcorn developed a following. High schoolers came to pop and bag it for football games. Paul and Michelle encouraged people to bring their own buckets to be filled with corn at a fixed price; some people showed up with shopping bags. The Amish didn’t come to the films, of course, but on some days you could see a horse and carriage lingering outside while the driver was buying a supply of popcorn.

The Haugeruds were generous with free passes as well. Over the years, they have donated hundreds of free passes to help local organizations raise money. At other times, Michelle realized, passes are a good form of marketing. “Give out one, and three more people will come along to pay.”

The JEM wasn’t just for movies. Youth groups held meetings there. Many local kids had their birthday parties there, accompanied by a movie or a videogame. The Haugerud daughters had slumber parties in the auditorium; after a movie, they settled down, if that’s the right word for a slumber party, in sleeping bags down front and in the aisles.

Many in Harmony believed that the JEM brought business to town. Julie Barrett, owner of the Village Square Restaurant across the street (and famous for her daily pies) said, “When people go to the movie, they stop at the Kwik Trip, our hardware store is open until 6:30, so you know they might try to kill two birds with one stone when they come to town.”

Over the situation hovered the fate facing every small town—the hollowing out of the center by the big-box stores down the road. Pull off any interstate highway, and you’ll see that the main streets of small towns have turned into empty storefronts, municipal offices, or struggling boutiques. When the JEM faced the need to go digital, Paul was concerned. “If we take one more thing away it’s going to hurt the community. I’m scared to death that main street is going to look like Harmony in the 1980’s when I was growing up. It was pretty bare.”

Single-screeners

Tonja Lawler selling tickets, Michelle Haugerud selling concessions.

The major distributors and the National Association of Theatre Owners now seem to take for granted that thousands of screens will close over the next few years. Some will fail to convert; others will struggle to pay for the conversion but still fold up. What are the likeliest victims? Those at the bottom of the food chain, the single screens and the “miniplexes” holding between two and seven screens.

These two categories account for over half of all exhibition sites in the US. But they amount to only a small slice of the total number of screens, which is what matters. And the number of small houses is shrinking. During the bankruptcy convulsions of the 1999-2001 period, circuits shed hundreds of screens. Since 2007, the total number of U. S. screens has remained fairly constant, but multiplex and megaplex installations have swollen by 2000 screens. Smaller facilities have lost about the same number—by going out of business.

Hollywood, people like to say, doesn’t want to leave money on the table. But more and more the long tail is a waste of resources. Why bother to prepare and ship a DCP to a theatre that yields a box-office take of less than $300 per day? Many decision-makers among the major distributors would be just as happy to let people in small towns wait a couple of months and catch the film on VOD or disc (rented from a gas station, since the video stores are gone too). As long as the megaplexes publicize the must-see movies, people will know what to buy or rent or stream. If you live in the countryside and you really feel the urge to catch the latest hit, get in your car or pickup and drive an hour to a ‘plex. No vehicle? Too young to drive? Wait for the video.

While digital projection allowed the major distributors to consolidate their power, it also offered a way to streamline and downsize exhibition. The 1600 American single-screen venues are especially vulnerable. For the industry, it seems, any part of film culture that preserves some history or takes root in a community is simply a nuisance. Michelle Haugerud puts it simply. “They don’t care if we go out of business.”

A digital jug

In late spring of 2011 Paul and Michelle decided to try to go digital. A new projection system and sound processor would cost $75,000. “We’ve tried to run it by ourselves and keep it independently owned, but it’s gotten to the point now where we’re looking for some help,” Paul said in July. “It was a difficult decision to ask for the community’s help,” Michelle wrote on her website. “We never wanted to ask for support, but we knew the public deserved to know why we may have to go out of business.”

In late spring of 2011 Paul and Michelle decided to try to go digital. A new projection system and sound processor would cost $75,000. “We’ve tried to run it by ourselves and keep it independently owned, but it’s gotten to the point now where we’re looking for some help,” Paul said in July. “It was a difficult decision to ask for the community’s help,” Michelle wrote on her website. “We never wanted to ask for support, but we knew the public deserved to know why we may have to go out of business.”

They began a fundraising drive. A young patron named Kirsten Mock decorated an old red juice jug for donations and put it on the candy counter. Paul and Michelle set up a designated savings account with a local lawyer’s name attached to make sure people understood that any donations would go only to the projector. A list was kept of all who put their names on donations, and the money would be refunded if the target sum weren’t reached.

The problem was that the JEM, privately owned and operated, wasn’t a nonprofit. Donations were not tax-deductible, and local government agencies couldn’t normally supply grants or other aid. During 4 July celebrations, however, a “Harmony Goes Hollywood” event featured a room in the Historical Society set up with an old projector and theatre seats, with clippings and photos showing the JEM over the years.

A local woman tipped Twin Cities media to the campaign. It was good timing: The US press was starting to notice the nationwide digital conversion. News outlets and TV stations covered the JEM’s crisis. Minnesota Public Radio picked up the story.

By fall, when the campaign had raised about $7200 locally, Paul and Michelle found a nearly new projector for $55,000. They managed to borrow the $48,000 they needed from a local bank. By shouldering the loan themselves, they showed the public that they were committed, and this gesture boosted donations.

As a result, on 11 November, the JEM screened its first movie on the Digital Cinema Package format, Dolphin Tale. On that weekend Paul thanked Kirsten for kicking off the fundraising and gave her a lifetime pass to the JEM. For the older crowd there was Football Monday, when Paul and Michelle projected a Vikings-Packers game. They couldn’t charge admission, but they sold tickets for drawings of prizes donated by local businesses.

Even though they had the equipment, Paul and Michelle still needed to pay for it. Later in November, the Trust for a Better Harmony stepped in to help. Enabled by a generous gift from Ms. Gladys Evenrud, the Trust and a Minnesota agency for community development arranged for a flexible loan package. As a result, the JEM now needed only $28,000, to be paid from community donation. The loan sparked still more offerings to the projection bank account.

New decisions

Paul Haugerud, son Peter (in overalls), and local boys tour the JEM booth.

On 13 January of this year, Paul died.

Commander of the local American Legion, he was cremated with military honors. He left behind Michelle, his six children, his parents, four brothers, and two grandchildren. The town grieved. “There’s nothing he wouldn’t do to help someone else,” a friend said.

Michelle remembers weeks going by in a blur. Friends brought over way too much food. “I had to freeze a lot of it.” She decided she simply had to move forward. She had a full-time job and had Peter, Julia, and Sierra at home, but she would keep running the JEM.

In February, a fundraiser was held at Wheelers Bar & Grill. The event had been planned before Paul’s death, but now it gained a new urgency and poignancy. Wheelers is named for its big roller rink, where Paul had helped out often. Across the day Wheelers held a silent auction and some bean-bag and darts tournaments. Those, along with food, drink, and music, raised an astonishing $16,000. That, plus the balance in the digital account, yielded enough to pay off the bank note for the projector. There have been more fundraising events, including a pancake breakfast. Michelle will soon pay the rest of the money owed. Any funds left over will be used for upgrades. Michelle is considering 3D conversion in a year or two.

Saturday night at the movies

Things have happened so quickly that Michelle hasn’t had time to thank everyone fully on her website, but she adds in a note to me:

It is so overwhelming to think of how the entire community and beyond has come together to make this all happen. I know that even though I am now the owner/ operator of the JEM, this theatre will be here for generations to come. I have had so many thanking me for staying in business. I know this is part due to the conversion and part due to Paul’s passing. I am very grateful for Paul’s family and my friends for being there helping me through all this.

Last Saturday, The Hunger Games drew a robust crowd, mostly groups of boys, groups of girls, and families, with a few elders sprinkled in. Nearly everybody bought concessions. Many carried in buckets for popcorn. The ticket booth was decorated with Easter rabbits and a Darth Vader helmet.

Upstairs, I saw a little room off the projection booth with a porthole. It was Michelle’s and Paul’s “private screening room,” she explained. They would watch the show from an old car seat there.

On the sidewalk outside, Girl Scouts were selling cookies. In the tiny lobby, dozens of construction-paper stars were pinned up, each bearing the name of someone who donated money. Above the booth was hung a framed lobby card for It’s a Wonderful Life.

Thanks to Michelle Haugerud for all her cooperation and enthusiasm. Her informative JEM website starts here. The page devoted to the digital upgrade traces the fundraising process and records her gratitude to the community. , On the same page, scroll down to see a video of Paul running the last 35mm show. Michelle supplied the photo of Paul and Peter above. Many of my quotations come from news stories that are linked on the JEM site.

Statistics on the number of theatres and screens in the US come from the annual reports of the Motion Picture Association of America and from The NATO Encyclopedia of Exhibition. Patrick Corcoran of NATO kindly supplied me with further information.

During my time in Harmony, I couldn’t get access to much material about the JEM in the old days. According to The Film Daily Year Book, the original JEM Theatre (sometimes called the Gem) opened in the mid-1930s. It burned down in 1940. The building next door was renovated as the New JEM, which opened in September of that year. A plain-spoken house of 325 seats, it had fluorescent lighting, satin curtains, three layers of acoustic tile, and a big furnace for the cold months. Its estimated cost was $18,000. For the premiere, a four-page color brochure was printed and sent to 3000 homes in the area. The publication was “made possible thru the whole-hearted cooperation of the businessmen of Harmony who fully realize the value and convenience of this modern, good-looking theatre.” This information comes from “Harmony, Minnesota, Salutes New Jem Theatre, S. E. Minnesota’s Finest Showplace!” The Harmony News, flyer dated September 1940.

Three years later the JEM closed and became a bowling alley. It sat vacant from 1947 to 1961, when Bob and Hazel Johnson reopened it. For a fuller chronology, go to Michelle’s page on JEM history.

Michelle Haugerud and daughter Julia, 24 March 2012.

PS 1 April 2012 Marilyn Bratager writes with this correction about the source of the JEM’s name.

Relatives of mine were the original owners: Joseph Milford Rostvold and his wife, Emma. The J was for Joseph Sr. and Jr., the E for Emma and their daughter Elizabeth, and the M for the senior Joseph’s middle name, Milford, which was the name he was known by. There was a third child, Richard, but they didn’t use his initial as they didn’t want the theatre to be called JERM. 🙂

Thanks to Marilyn for the information!

Pandora’s digital box: From films to files

“Up ahead was Pandora. You grew up hearing about it, but I never figured I’d be going there.”

DB here:

Actually it wasn’t originally a box but a jug. And it might not have been filled with all the world’s misfortunes; it might have housed all the virtues. In Greek mythology, the gods create her as the first woman, sort of the ancient Eve. We get our standard idea of her story not from the ancient world, however, but from Erasmus. In 1508 he wrote of her as the most favored maiden, granted beauty, intelligence, and eloquence. Hence one interpretation of her name: “all-gifted.” But to Prometheus she brought a box carrying, Erasmus said, “every kind of calamity.” Prometheus’ brother Epimetheus accepted the box, and either he or Pandora opened it, “so that all the evils flew out.” All that remained inside was Hope. (Don’t think there isn’t a lot of dispute about why hope was cooped up with all those evils.)

The idea of Pandora’s box spread throughout Western culture to denote any imprudent unleashing of a multitude of unhappy consequences. It’s long been associated with an image of an attractive but destructive woman, and we don’t lack examples in films from Pabst to Lewin. But there’s another interpretation of the maiden’s name: not “all-gifted” but “all-giver.” According to this line, Pandora is a kind of earth goddess. In one Greek text she is called “the earth, because she bestows all things necessary for life.”

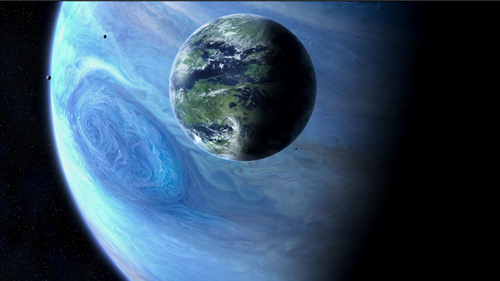

The less-known interpretation seems to dominate in Avatar. Pandora, a moon of the huge planet Polyphemus, is a lush ecosystem in which the humanoid Na’vi live in harmony with the vegetation and the lower animals they tame or hunt. Nourished by a massive tree (they are the ultimate tree-huggers), they have a balanced tribal-clan economy. Their spiritual harmony is encapsulated in the beautiful huntress Neytiri. As the mate for the first Sky-Person-turned-Na’vi, Avatar Jake, she’s also an interplanetary Eve. And by joining the Na’vi on Pandora, Jake does find hope.

The irony of a super-sophisticated technology carrying a modern man to a primal state goes back at least as far as Wells’ Time Machine. But the motif has a special punch in the context of the Great Digital Changeover. Digital projection promises to carry the essence of cinema to us: the movie freed from its material confines. Dirty, scratched, and faded film coiled onto warped reels, varying unpredictably from show to show (new dust, new splices) is now shucked off like a husk. Now images and sounds supposedly bloom in all their purity. The movie emerges butterfly-like, leaving the marks of dirty machines and human toil behind. As Jake returns to Eden, so does cinema.

Avatar or atavism?

Kristin suggested the title for this series of blog entries, and I liked its punning side. For one thing, Avatar was a turning point in digital projection. 3D, as we now know, was the Trojan Horse that gave exhibitors a rationale to convert to digital. Avatar, an overwhelming merger of digital filmmaking (halfway between cartoon and live-action) and 3D digital projection, fulfilled the promise of the mid-2000s hits that had hinted at the rewards of this format.

With its record $2.7 billion worldwide box office, Avatar convinced exhibitors that digital and 3D could be huge moneymakers. In 2009, about 16,000 theatres worldwide were digital; in 2010, after Avatar, the number jumped to 36,000. True, theatre chains also benefited from JP Morgan’s timely infusion of about half a billion dollars in financing in November 2009, a month before the film’s release. Still, this movie that criticized technology’s war on nature accelerated the appearance of a new technology.

Throughout this series, I’ve tried to bring historical analysis to bear on the nature of the change. I’ve also tried not to prejudge what I found, and I’ve presented things as neutrally as I could. But I find it hard to deny that the digital changeover has hurt many things I care about.

The more obvious side of my title’s pun was to suggest that digital projection released a lot of problems, which I’ve traced in earlier entries. From multiplexes to art houses, from festivals to archives, the new technical standards and business policies threaten film culture as we’ve known it. Hollywood distribution companies have gained more power, local exhibitors have lost some control, and the range of films that find theatrical screening is likely to shrink. Movies, whether made on film or digital platforms, have fewer chances of surviving for future viewers. In our transition from packaged-media technology to pay-for-service technology, parts of our film heritage that are already peripheral—current foreign-language films, experimental cinema, topical and personal documentaries, classic cinema that can’t be packaged as an Event—may move even further to the margins.

Moreover, as many as eight thousand of America’s forty thousand screens may close. Their owners will not be able to afford the conversion to digital. Creative destruction, some will call it, playing down the intangible assets that community cinemas offer. But there’s also the obsolescence issue. Equipment installed today and paid for tomorrow may well turn moribund the day after tomorrow. Only the permanently well-funded can keep up with the digital churn. Perhaps unit prices will fall, or satellite and internet transmission will streamline things, but those too will cost money. In any event, there’s no reason to think that the major distributors and the internet service providers will be feeling generous to small venues.

Did this Pandora’s box leave any reason to be optimistic? I haven’t any tidy conclusions to offer. Some criticisms of digital projection seem to me mistaken, just as some praise of it seems to me hype or wishful thinking. In surrendering argument to scattered observations, this final entry in our series is just a series of notes on my thinking right now.

What you mean, celluloid?

First, let’s go fussbudget. It’s not digital projection vs. celluloid projection. 35mm motion picture release prints haven’t had a celluloid base for about fifteen years. Release prints are on mylar, a polyester-based medium.

Mylar was originally used for audio tape and other plastic products. For release prints of movies, it’s thinner than acetate but it’s a lot tougher. If it gets jammed up in a projector, it’s more likely to break the equipment than be torn up. It’s also more heat-resistant, and so able to take the intensity of the Xenon lamps that became common in multiplexes. (Many changes in projection technology were driven by the rise of multiplexes, which demanded that one operator, or even unskilled staff, could handle several screens.)

Projectionists sometimes complain that mylar images aren’t as good as acetate ones. In the 1940s and 1950s, they complained about acetate too, saying that nitrate was sharper and easier to focus. In the 2000s they complained about digital intermediates too. Mostly, I tend to trust projectionists’ complaints.

But acetate-based film stock is still used in shooting films, so I suppose digital vs. celluloid captures the difference if you’re talking about production. Even then, though, there’s a more radical difference. A strip of film stock creates a tangible thing, which exists like other objects in our world. “Digital,” at first referring to another sort of thing (images and sounds on tape or disk), now refers to a non-thing, an abstract configuration of ones and zeroes existing in that intangible entity we call, for simple analogy, a file.

George Dyson: “A Pixar movie is just a very large number, sitting idle on a disc.”

Big and gregarious

Sometimes discussion of the digital revolution gets entangled in irrelevant worries.

First pseudo-worry: “Movies should be seen BIG.” True, scale matters a lot. But (a) many people sit too far back to enjoy the big picture; and (b) in many theatres, 35mm film is projected on a very small screen. Conversely, nothing prevents digital projection from being big, especially once 4K becomes common. Indeed, one thing that delayed the finalizing of a standard was the insistence that so-called 1.3K wasn’t good enough for big-screen theatrical presentation. (At least in Europe and North America: 1.3K took hold in China, India, and elsewhere, as well as on smaller or more specialized screens here.)

Second pseudo-worry: “Movies are a social experience.” For some (not me), the communal experience is valuable. But nothing prevents digital screenings from being rapturous spiritual transfigurations or frenzied bacchanals. More likely, they will be just the sort of communal experiences they are now, with the usual chatting, texting, horseplay, etc.

Of course, image quality and the historical sources and consequences of digital projection are something else again.

Irresolution

It’s a good thing the pros kept pushing. Had filmmakers and cinephiles welcomed the earliest digital systems, we might have something worse. Here’s George Lucas in 2005, talking less about photographic quality than the idea of the sanitary image.

The quality [of digital projection] is so much better. . . . You don’t get weave, you don’t get scratchy prints, you don’t get faded prints, you don’t get tears. . . The technology is definitely there and we projected it. I think it is very hard to tell a film that is projected digitally from a film that is projected on film.

And he’s referring to the 1280-line format in which Star Wars Episode I was projected in 1999.

Probably the widespread skepticism from directors and cinematographers helped push the standard to 2K. (So did the adoption of the Digital Intermediate.) Optimistic observers in the mid-2000s expected the major studios to make 4K the standard right away. Given the constraints of storage at that time, the 2K decision might be justified. But like the 24 frames-per-second frame rate of sound cinema, it was a concession to the just-good-enough camp.

At the same time, George seems to grant that progress will be needed in the area of resolution.

You’ve got to think of this [our current situation] as the movie business in 1901. Go back and look at the films made in 1901, and say, “Gee, they had a long way to go in terms of resolution. . . .”

Actually, in films preserved in good state from 1901, the resolution looks just fine—better than most of what we see at the multiplex today, on film or on digital.

The invisible revolution

Speaking of sound cinema: Is the changeover to talkies the best analogy for what we’re seeing now? Mostly yes, because of the sweeping nature of the transformation. No technological development since 1930 has demanded such a top-to-bottom overhaul of theatres. Assuming a modest $75,000 cost for upgrading a single auditorium, the digital conversion of US screens has cost $1.5 billion.

In an important respect, though, the analogy to sound doesn’t hold good. When people went to talkies, they knew that something new had been added. The same thing happened with color and widescreen. And surely many customers noticed multi-track sound systems. But what moviegoers notice that a theatre is digital rather than analog? Many probably assume that movies come on DVDs or, as one ordinary viewer put it to me, “film tapes.” Anyhow, why should they care?

There was a debate during the 2000s that audiences would pay more for a ticket to a digital screen. But that notion was abandoned. People aren’t that easy to sucker. So we’re back with 3D as the killer app, the justification for an upcharge. Whether 3D survives, dominates, or vanishes isn’t really the point. It’s served its purpose as the wedge into digital installation.

By the way, according to one industry leader, 2D ticket prices are likely to go up this year while 3D prices drop. Is this flattening of the price differential a strategy to get more people to support a fading format?

Mommy, when a pixel dies, does it go to heaven?

Digital was sold to the creative community in part by claiming that at last the filmmaker’s vision would be respected. Every screening would present the film in all its purity, just as the director, cinematographer et al. wanted it to be seen.

Last week I went to see Chronicle with my pal Jim Healy. The projector wasn’t perpendicular to the screen, so there was noticeable keystoning. The masking was set wrong, blocking off about a seventh of the picture area. And two little pink pixels were glowing in the middle of the northwest quadrant throughout the movie. I’m assuming that Chronicle’s director didn’t mandate these variants on his “vision.”

Jim went out to notify the staff, and two cadets came down to fiddle with the masking. The movie had already been playing in that house for several days. Maybe the masking hadn’t been changed for months? And of course the projector couldn’t be realigned on the fly. As for those pixels: There’s nothing to be done except buy a new piece of gear. Chapin Cutler of Boston Light & Sound tells me that replacing the projector’s light engine runs around $12,000. At that price, there may be a lot of dead pixels hanging around a theatre near you.

Video to the max

Not so long ago, the difference was pitched as film versus video. That was the era of movies like The Celebration and Chuck and Buck. Then came high-definition video, which was still video but looking somewhat better (though not like film). But somehow, as if by magic, very-high-definition video, with some ability to mimic photochemical imagery, became digital cinema, or simply digital.

We have to follow that usage if we want to pinpoint what we’re talking about at this point in history. But damn it, let’s remember: We are still talking about video.

The Film Look

Ever since the days of “film vs. video,” we’ve been talking about the “film look.” What is it?

I’m far from offering a good definition. There are many film looks. You have orthochromatic and panchromatic black-and-white, nitrate vs. acetate vs. mylar, two-color and three-color Technicolor, Eastman vs. Fuji, and so on. But let’s stick just with projection. Is there a general quality of film projection that differentiates it from digital displays?

Some argue that flicker and the slight weaving of film in the projector are characteristic of the medium. Others point to qualities specific to photochemistry. Film has a greater color range than digital: billions of color shades rather than millions. Resolution is also different, although there’s a lot of disagreement about how different. A 35mm color negative film is said to approximate about 7000 lines of resolution, but by the time a color print is made, the display yields about 5000 lines—still a bit ahead of 4K digital. But each format has some blind spots. There’s a story that the 70mm camera negative of The Sound of Music recorded a wayward hair sticking straight out on the top of Julie Andrew’s head. It wasn’t visible in release prints of the day, but a 4K scan of the negative revealed it.

Film fans point to the characteristic film shimmer, the sense that even static objects have a little bit of life to them. Roger Ebert writes:

Film carries more color and tone gradations than the eye can perceive. It has characteristics such as a nearly imperceptible jiggle that I suspect makes deep areas of my brain more active in interpreting it. Those characteristics somehow make the movie seem to be going on instead of simply existing.

Watch fluffy clouds or a distant forest in a digital display, and you’ll see them hang there, dead as a postcard vista. In a film, clouds and trees pulsate and shift a little. Partly the film is capturing very slight movements of them in air, or the movement of light and air around them. In addition, the film itself endows them with that “nearly imperceptible jiggle” that our visual system detects.

How? Brian McKernan points out that the fixed array of pixels in a digital camera or projector creates a stable grid of image sites. But the image sites on a film frame are the sub-microscopic crystals embedded in the emulsion and activated by exposure to light. Those crystals are scattered densely throughout the film strip at random, and their arrangement varies from frame to frame. So the finest patterns of light registration tremble ever so slightly in the course of time, creating a soft pictorial vibrato.

Another source of the film look was suggested to me by Jeff Roth, Senior Vice-President of Post-Production at Focus Features. Jeff notes that a video chip is a flat surface, with the pixels activated by light patterns across the grid. (We forget that in the earliest stages, “digital” image capture is “analog”—that is, photographic—before it gets quantized and then digitized.) But a film strip has volume. It seems very thin to us, but light waves find a lot to explore in there. Light penetrates different layers of the emulsion: blue on top, then a yellow filter, then green, then red. The light rays leave traces of their passage through the layers. Joao S. de Oliveira puts it more laconically:

There is a certain aura in film that cannot exist in a digital image. . . . From the capture of a latent image, the micro-imperfections created by light on a perfect crystalline structure—a very three-dimensional process—to its conversion into a visible and permanent artefact, the latitude and resolution of film are incomparable to any other process available today to register moving images.

For example, shadows and highlights are captured “deeply.” Bright areas move into shadow gracefully. Similarly, film is far more tolerant of overexposure than digital recording is; even blown-out areas of the negative can be recovered. (In still photography, darkroom technique allows you to “burn in” an overexposed area.) The blown-out elements are still there, but in digital they’re gone forever.

Film shown on a projector maintains the film look captured on the stock: You’re just shining a light through it. We’ve all heard stories, however, of those DVD transfers that buff the image to enamel brightness and then use a software program to add grain. One archivist tells me of an early digital transfer of Sunset Blvd. that looked like it had been shot for HDTV.

But today carefully done digital transfers can preserve some of the film look. When my local theatres were transitioning, I saw Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy first on film, then on digital, and then again on film. Although the digital looked a little harder, I was surprised how much graininess it preserved. So it seems to me that some qualities of the film look can be retained in digital transfers.

Marching orders

George Lucas, at the 2005 annual convention and trade show of the National Association of Theatre Owners: “I’m sort of the digital penny that shows up every year to say, ‘Why haven’t you got these digital theatres yet?'” (Variety 17 March 2005).

“His point to theater owners was that 3D, which can bring in new audiences and justify higher ticket prices, is only possible after they make the switch to digital projection” (Hollywood Reporter 10 February 2012).

Premonitions

In summer of 1999, Godfrey Cheshire published a two-part article, “The Death of Film/ The Decay of Cinema.” It’s proven remarkably far-sighted.

He predicted that within a decade your multiplex theatre would contain “a glorified version of a home video projection system.” He predicted that the rate of adoption would be held back by costs. He predicted that the changeover would mostly benefit the major distributors, and that exhibitors would have to raise ticket and concession prices to cover investments. He predicted what is now called “alternative content”—sports, concerts, highbrow drama, live events—and correctly identified it as television outside the home. He predicted the preshow attractions that advertise not only products but TV shows and pop music. He predicted what is being seriously discussed in industry circles now: letting viewers snap open their “second screen” and call, text, check email, and surf the net during the show. And he predicted that distractions and bad manners in movie theatres would drive away viewers who want to pay attention.

People who want to watch serious movies that require concentration will do so at home, or perhaps in small, specialty theatres. People who want to hoot, holler, flip the bird and otherwise have a fun communal experience . . . will head down to the local enormoplex.

Godfrey goes on to make provocative points about the effects of digital technology on how movies are made as well. His essay should be prime reading for everyone involved in film culture—e.g., you.

WYSIWYG

I’ve mentioned the postcard effect that makes static objects just hang there. In less-than-2K digital displays, I see other artifacts, most of which I don’t know the terms for. Film has artifacts too, notably graininess, but I find the digital ones more off-putting. There’s a waterfall effect, when ripples rush down uniform surfaces. Sometimes I see diagonal striping from one corner to its opposite, an effect common on home and bar monitors. (I’m told it comes from interference from phones and the like.) On cheap DVDs, or commercial ones played on region-free machines, you can detect a weird pop-out effect, where the surfaces of different planes, usually marked by dark edge contours, detach themselves. The surfaces float up, wobbling out of alignment with their surroundings.

I am not hallucinating these things. When I point them out, others see them, and then, like me, they can’t ignore them. So I’ve stopped pointing them out, especially when a friend wants to show me his (always his) fancy home theatre. Why spoil their pleasure?

Same difference

Various positions on the split between film and digital (for want of a better term): I’ve held nearly all of them at various points, and sometimes simultaneously. I’ll confine myself, as usual, just to film-based projection and digital projection, and assuming minimal competence of staff in each domain. (Just because something’s shown in 35mm, that doesn’t mean it’s shown well.)

1. They’re not the same, just two different media. They’re like oil painting and etching. Both can coexist as vehicles for artists’ work.

2. They’re not the same, and digital is significantly worse than film. This was common in the pre-DCI era.

3. They’re not the same, and digital is significantly better than film. Expressed most vehemently by Robert Rodriguez and with some insistence by Michael Mann.

4. They’re not the same, and digital is mostly worse, but it’s good enough for certain purposes. Espoused by low-budget filmmakers the world over. Also embraced by exhibitors in developing countries, where even 1.3K is considered an improvement over what people have been getting.

5. They’re the same. This is the view held by most audiences. But just because viewers can’t detect differences doesn’t mean that the two platforms are equally good. Digital boosters maintain that we now have very savvy moviegoers who appreciate quality in image and sound. In my experience, people don’t notice when the picture is out of focus, when the lamp is too dim, when the surround channels aren’t turned on, when speakers are broken, and when spill light from EXIT signs washes out edges of the picture. (See Chronicle anecdote above.) As long as they can hear the dialogue and can make out the image, I believe, most viewers are happy.

‘Plex operators are notoriously indifferent to such niceties. In most houses, good enough is good enough. Teenage labor can maintain only so much.

Film/video

“The picture was nice and crisp.” “So much better than film.” “We showed a Blu-ray and it looked fine.”

I don’t trust people’s responses to such things unless the judgment is comparative. Show film and the digital program side by side and then judge. Or even show rival manufacturers’ DCI-compliant projectors side by side. I think you will see differences.

As they develop, new reproductive media improve in some dimensions but degrade on others. As the engineers tell us, there’s always a trade-off.

CD is more convenient than vinyl, but its clean, dry sound isn’t as “warm.” Mp3, even more convenient and portable, packs a sonic punch but is inferior in dynamics and detail to CDs. Similarly, back in the 1990s, laserdiscs had to be handled more carefully than tape cassettes, and in playback they required interruptions as sides were flipped. But aficionados accepted these drawbacks because we believed that our optical discs looked and sounded much better than VHS. One well-known professor urged that classroom screenings could now dispense with film.

Now those laserdisc images would be laughed out of the room. Have a look at an image from the 1995 restoration of Disney’s Pinocchio. It’s taken from a transfer of the laserdisc to DVD-R. (You can’t grab a frame directly from a laserdisc.) In this and the others, I haven’t adjusted the raw image.

Actually, on a decent monitor, it looks better than this. Since you can’t grab a frame directly from a laserdisc, LD couldn’t stand up to home theatre projection today. The 2009 DVD and Blu-ray (below) are sharper.

Now compare the DVD with a dye-transfer Technicolor image from a 1950s 35mm print. There have been some gains and some losses in color range, shadow, and detail. For example, Stromboli’s trousers and the footlight area go very black, presumably because of the silver “key image” used for greater definition in the dye-transfer process. IB Tech restorations routinely bring out “hidden” color in such areas.

Which is best? You can take your pick, but you’re better able to choose when you’re not seeing one image in isolation.

Live/ Memorex

Of course side-by-side comparisons can fail when most viewers don’t notice even gross differences. In a course, I once showed a 16mm print of Night of the Living Dead, and a faculty friend came to the screening. (Yes, history profs can be horror fans.) In my followup lecture, I showed clips on VHS, dubbed from a VHS master. My friend came to the class for my talk. Afterward he swore that he couldn’t tell any difference between the film and the second-generation VHS tape.

This raises the fascinating question of changing perceptual frames of reference. My friend knew the film very well, and he’d watched it many times on VHS. Did he somehow see the 16 screening as just a bigger tape replay? Did none of its superiority register? Maybe not.

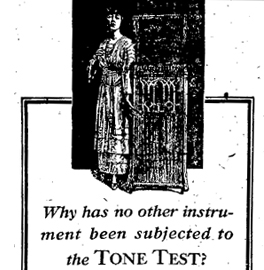

From 1915 to 1925, Thomas Edison demonstrated his Diamond Disc Phonograph by inviting audiences to compare live performances with recordings. His publicists came up with the celebrated Tone Tests. A singer on stage would stand by while the disc began to play. Abruptly the disc would be turned down and the singer would continue without missing a note. Then the singer would stop and the disc, now turned up, would pick up the thread of melody. Greg Milner writes of the first demonstration:

From 1915 to 1925, Thomas Edison demonstrated his Diamond Disc Phonograph by inviting audiences to compare live performances with recordings. His publicists came up with the celebrated Tone Tests. A singer on stage would stand by while the disc began to play. Abruptly the disc would be turned down and the singer would continue without missing a note. Then the singer would stop and the disc, now turned up, would pick up the thread of melody. Greg Milner writes of the first demonstration:

The record continued playing, with [the contralto Christine] Miller onstage dipping in and out of it like a DJ. The audience cheered every time she stopped moving her lips and let the record sing for her.

At one point the lights went out, but the music continued. The audience could not tell when Miller stopped and the playback started.

The Tone Tests toured the world. According the publicity machine run by the Wizard of Menlo Park, millions of people witnessed them and no one could unerringly distinguish the performers from their recording.

Edison’s sound recording was acoustic, not electrical, and so it sounds hopelessly unrealistic to us today. (You can sample some tunes here.) And there’s some evidence, as Milner points out, that singers learned to imitate the squeezed quality of the recordings. But if the audiences were fairly regularly fooled, it suggests that our sense of what sounds, or looks, right, is both untrustworthy and changeable over history.

To some extent, what’s registered in such instances aren’t perceptions but preferences. Wholly inferior recording mechanisms can be favored because of taste. How else to explain the fact that young people prefer mp3 recordings to CDs, let alone vinyl records? It’s not just the convenience; the researcher, Jonathan Berger of Stanford University, hypothesizes that they like the “sizzle” of mp3.

To some extent, we should expect that people who’ve watched DVDs from babyhood onward take the scrubbed, hard-edge imagery of video as the way that movies are supposed to look. Or perhaps still younger people prefer the rawer images they see on Web videos. Do they then see an Imax 70mm screening as just blown-up YouTube?

The epiphanic frame

Godard’s Éloge de l’amour: DVD framing vs. original 35mm framing.

Digital projection is already making distributors reluctant to rent films from their libraries, and film archives are likely to restrict circulation of their prints. When 35mm prints are unavailable, it will be difficult for us to perform certain kinds of film analysis. In order to discover things about staging, lighting, color, and cutting in films that originated on film, scholars have in the past worked directly with prints.

For example, I count frames to determine editing rhythms, and working from a digital copy isn’t reliable for such matters. True, fewer than a dozen people in the world probably care about counting frames, so this seems like a trivial problem. But analysts also need to freeze a scene on an exact frame. For live-action film, that’s a record of an actual instant during shooting, a slice of time that really existed and serves to encapsulate something about a character, the situation, or the spatial dynamics of the scene. (Many examples here.) This is why my books, including the recent edition of Planet Hong Kong, rely almost entirely on frame grabs from 35mm prints.

Paolo Cherchi Usai suggests that for every shot there is an “epiphanic frame,” an instant that encapsulates the expressive force of that shot. Working with a film print, you can find it. On video, not necessarily.

Just as important, for films originating in 35mm, we can’t assume that a video copy will respect the color values or aspect ratio of the original. Often the only version available for study will be a DVD with adjusted color (see Pinocchio above) and in a different ratio. I’ve written enough about variations in aspect ratios in Godard and Lang (here and here) to suggest that we need to be able to go back to 35mm for study purposes, at least for photographically-generated films. For digitally-originated films, researchers ought to be able to go back to the DCP as released, but that will be nearly impossible.

The analog cocoon

I began this series after realizing that in Madison I was living in a hothouse. As of this fall, apart from festival projections on DigiBeta or HDCam, I hadn’t seen more than a dozen digital commercial screenings in my life, and I think nearly all were 3D. Between film festivals, our Cinematheque, and screenings in our local movie houses, I was watching 35mm throughout 2011, the year of the big shift.

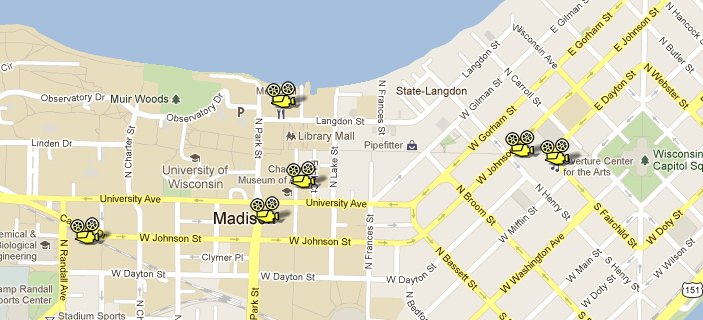

There are six noncommercial 35mm film venues within walking distance of my office at the corner of University Avenue and Park Street. And two of those venues still use carbon-arc lamps! Go here for a fuller identification of these houses. Moreover, in my office sit two Steenbeck viewing machines, poised to be threaded up with 16mm or 35mm film. (“Ingestion” is not an option.)

But now I’ve woken up. We all conduct our educations in public, I suppose, but preparing this series has taught me a lot. I still don’t know as much as I’d like to, but at least, I now appreciate the riches around me.

I’m very lucky. It’s not over, either. The good news is that the future can’t really be predicted. Like everybody else, I need to adjust to what our digital Pandora has turned loose. But we can still hold on to hope.

This is the final entry in a series on digital film distribution and exhibition.

On the Pandora perplex, see Dora and Erwin Panofsky, Pandora’s Box: The Changing Aspects of a Mythical Symbol (Princeton University Press, 1956). The Wikipedia article on the lady is also admirably detailed.

Godfrey Cheshire’s prophetic essay is apparently lost in the digital labyrinths of the New York Press. Godfrey tells me that he’s exploring ways to post it, so do continue to search for it. Another must-read assessment is on the TCM site. Pablo Kjolseth, Director of the International Film Series at the University of Colorado—Boulder, writes on “The End.” See also Matt Zoller Seitz’s sensible take on the announcement that Panavision has ceased manufacturing cameras. Some wide-ranging reflections are offered in Gerda Cammaer’s “Film: Another Death, Another Life.”

Brian McKernan’s Digital Cinema: The Revolution in Cinematography, Postproduction, and Distribution (MGraw-Hill, 2005) is the source of two of my quotations from George Lucas (pp. 31, 33) and some ideas about the film look (p. 67). My quotation from Greg Milner on the Tone Test comes from his Perfecting Sound Forever: An Aural History of Recorded Music (Faber, 2009), 5.

NPR recently broadcast a discussion of the differences, both acoustic and perceptual, among consumer audio formats. The show includes A/B comparisons. Thanks to Jeff Smith for the tip.

Thanks to Chapin Cutler, Jeff Roth, and Andrea Comiskey, who prepared the projector map of downtown Madison and the east end of the campus.

6 February 2012: This series has aroused some valuable commentary around the Net, just as more journalists are picking up on the broad story of how the conversion is working. Leah Churner has published a useful piece in the Village Voice on digital projection, and Lincoln Spector has posted three essays at his blogsite, the last entry offering some suggestions about how to preserve both film-based and digital-originated material.

“You get soft, Pandora will shit you out dead, with zero warning.”

Pandora’s digital box: Notes on NOCs

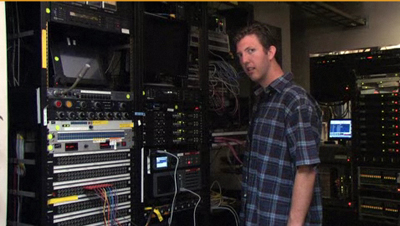

A video-wall display in the Christie Network Operations Center, Cypress, California.

DB here:

You’re in a multiplex. The pre-show attractions are large, loud promotions for TV shows, pop music, and star careers, interspersed with ads for men’s cologne and local pet-grooming facilities. Then comes the theatre chain itself telling you to hush up, turn off anything that emits light or sound, take your feet off the seats in front of you, and buy some popcorn. Next comes a barrage of trailers. Sooner or later the movie starts.

If you look back at the projection booth, will you see another human being? Not necessarily. It’s possible that everything that happens in your theatre is automated.

Now imagine another space, a large room with ranks of work stations. A couple of dozen people sit before their monitors, facing a video wall. From a room like this in Omaha, Nebraska, or in Cypress, California, or in Liège, Belgium, or in Shenzhen, China, these workers can remotely track thousands of theatre screens, including yours. It’s another consequence of the emergence of digital projection in our movie theatres.

Command and control

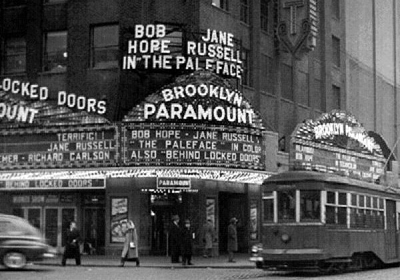

Brooklyn Paramount Theatre, 1948, from the splendor that is Cinema Treasures.

One of the many lessons you learn from Douglas Gomery’s magisterial history of the Hollywood studio system is straightforward. For about a hundred years, film producers and distributors have sought to control exhibition.

The advantages are obvious. Controlling exhibition keeps competitors off screens, it yields more or less assured revenues, and it allows vast economies of scale. If you can count on 2000-4000 screens playing your movie, as is common for Hollywood releases today, you can budget your production accordingly.

From the 1920s through the 1940s, studio control was quite direct. The Big Five companies (Paramount, Loew’s/MGM, 20th Century-Fox, Warner Bros., and RKO) wholly or partially owned hundreds of theatres, and these served as display cases for their product. Because no studio could supply all its theatre chains with films, studios shared their screens with their peers and kept other companies’ films out. “Here,” Gomery writes, “was a collusive oligopoly (control by a few) that operated as an almost pure monopoly.”

The studios didn’t own most of America’s theatres, just the most profitable ones. The thousands of independent houses and chains were subjected to studio control in more indirect ways. The studios forced the independents to book films in batches (“blocks”). To get prime releases, the exhibitors had to take weaker titles. Likewise, the independents had to bid for upcoming releases without being able to see them.

The structure of the market was another strategy of control. Adolph Zukor pioneered the system of runs, zones, and clearances. If people wanted to see a new release immediately, they had to pay top dollar at a first-run theatre. After a certain interval, the clearance, the movie would play a second run theatre in another territory at a lower price, and so on down the food chain of movie houses.

Technology was another strategy of control. The 35mm film standard wasn’t proprietary, but the sound systems that the studios adopted in the late 1920s were. Of the dozens of systems, only two became standardized: Western Electric and RCA. In a process similar to what’s happening today, theatres were forced to install one system or the other. The thousands of screens that couldn’t afford the new technology went dark.

This system worked to the Big Five’s benefit until 1948, when the Supreme Court declared Hollywood’s vertical integration monopolistic. The studios chose the wisest way to break up, given the slump in admissions: They divested themselves of their theatres and concentrated on production and distribution. (The process took several years in some cases, and there often remained close unofficial ties between the Majors and their former circuits.) In addition, block-booking and blind bidding were outlawed, so some market factors became more favorable to exhibitors.

The postwar studios occasionally tried to remake exhibition through new technology. CinemaScope, designed by 20th Century-Fox, sought to become the industry standard for widescreen presentation. Although there was considerable take-up, it had competition from other systems (notably Paramount’s VistaVision) and exhibitors were able to wring concessions from Fox. Centrally, exhibitors were reluctant to install magnetic stereo playback, and so Fox had to compromise by producing prints that could play on optical sound systems as well. Similarly, while various 70mm formats were tried, none became obligatory for exhibitors, since films released in 70 were also released in 35, if only in later runs.

Of course Hollywood still had a desirable product and could charge dearly for it, so stiff contracts for revenue returns gave studios considerable power. In the 1970s, the Majors (which no longer included RKO and had expanded to include Disney, Columbia, and Universal) found another way to use market dynamics to control exhibition. To publicize Jaws (1975), Universal launched massive television advertising and avoided the “platforming” or “exclusive engagement” practice. Studio chief Lew Wasserman opted for “saturation booking,” releasing Jaws on over 400 screens simultaneously. A month later it expanded to over 600.

The growth of the blockbuster, nurtured by Star Wars, Superman, and other huge hits, encouraged theatre chains to build multiplexes. The distributors could then blanket screens with their product. Exhibitors could realize economies of scale by holding over some movies for months while rotating regular releases through other screens.

With the arrival of cable, satellite transmission, and home video, studios were able to maintain tiers of price discrimination. The theatrical opening became the loss-leader, making less revenues but establishing buzz for the ancillary market. Theatrical runs were shortened considerably, but the “windows” of video distribution became the equivalent of second- and later runs. A movie becomes available on Pay Per View, then VOD and/or DVD, then premium cable, and so on. The windows’ length and ordering have changed over the years, but throughout, by carving up the market by price discrimination the studios continued to rule exhibition patterns.

My account makes recent history too neat, with studios apparently steamrollering unprotesting exhibitors. In fact, exhibitors have responded to some pressures by dragging their feet or pushing back. Better sound systems took some years to penetrate the market. Some big theatres refused to play Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace because of onerous terms, including a minimum guarantee and a commitment to a lengthy run in a ‘plex’s biggest auditorium. More recently, studios’ efforts to shorten windows and release films sooner on DVD or on VOD have sparked resistance.

Studios have periodically tried to become vertically integrated again. There were some attempts in the 1980s to run theatre circuits, but only Viacom has found success owning both Paramount and the National Amusements chain. Today, technology is providing a more effective lever–or rather a crowbar. Digital projection furnishes the most thoroughgoing opportunity for studio control over exhibition since the coming of sound, and perhaps since the days when the Majors owned movie houses.

NOC, NOC, who’s there?

Christie Network Operations Center, Cypress, California.

My first entry in this series considered the power of setting standards, something Hollywood has been good at for decades. In 2005 the Majors established the technical specifications for the Digital Cinema Initiatives. As has happened throughout history, they had the input from the powerful manufacturers, service companies, and professional associations, like the SMPTE and the American Society of Cinematographers.

Once the standards were set, the projection and service suppliers could move forward with appropriate equipment. The conversion is expensive, so exhibitors have been offered the option of signing up for a Virtual Print Fee. This is a partial subsidy from the major companies that is passed through an “integrator,” a third-party company that attends to acquiring the equipment, installing it, and monitoring payback.

A decade ago, over a dozen significant US theatre chains filed for bankruptcy protection, so costs are constantly on exhibitors’ minds. Digital projection offered multiplex operators the opportunity to cut staff. Screening film prints is somewhat technical, and it relies on mechanical skills that are growing rare. So anything the manager can do to simplify running the show is welcome. Movies on digital files filled the bill. A film projectionist, represented by what was once one of the more powerful unions around, is expensive. Teenage labor is not.

Digital works for the fresh-faced novice. Once the film comes in on a hard drive, it’s not terribly hard to set up a show. Disney has made a couple of remarkable instructional films (here and here) for the new projector operator Jimmy, who wears the requisite Bob & Ted apparel.

In the old days, Walt would have given us a cartoon, and Goofy would have been the star.

Jimmy loads the movies, and he or the manager sets up the programs. Once the features, the trailers, and the ads are on the servers or the library system, the theatre manager can program every screen. From a computer in the manager’s office, or almost anywhere, he or she can build each auditorium’s playlist by dragging and dropping. If the arrangements with the distributor permit, the files can be migrated from screen to screen.

Even under these conditions, though, you need minimal maintenance. Projector lamps must be changed, for instance. The installers or a local expert can supply routine maintenance, but sometimes there are problems. An encrypted file can’t be opened, or it’s corrupted, or the show mysteriously stops. Very likely Jimmy, even consulting his manual, can’t fix the problem.

Enter the NOC.

Network Operations Centers, also known as Data Centers, are part of broader Information Technology management. They’re used whenever a business or government agency has a network that needs 24/7 monitoring. All Fortune 1000 companies have NOCs, and probably have mirror backups of them scattered around the world. NOCs coordinate railway systems, military systems, banking, and police and fire departments. Amazon has a NOC in Seattle, Wal-Mart has one in Bentonville, Arkansas, and AT&T has a monstrous one in Bedminster, New Jersey (below).

There’s a nice gallery of NOCs here.

Don’t confuse NOCs with call centers or help lines. NOCs are handling and storing vast streams of data from computers, cameras, and other inputs. The goal is keeping track of things pertinent to the business or agency. But of course even large staffs can’t do this simply by eyeballing the flood of data. Instead, the software is set to notice anomalies and to call them to the attention of the humans. So if a police camera outside a Tube stop in London picks up a pattern of unusual activity, say three men running purposefully toward a woman, that information is pulled out of the stream and sent to an operator for inspection.

Once film theatres became digital, they acquired the ability to connect to NOCs via the Web. An owner who funded the purchase of the DCI-compliant equipment might well choose to pay a NOC to provide oversight and help. Exhibitors who sign up for a Virtual Print Fee program are required to sign up for a NOC. NOC services may be supplied by the equipment manufacturer (Sony, Christie’s, Barco, GDC et al.) or by the installer, such as Ballantyne Strong (Omaha) or Film-Tech Cinema Systems (Plano, Texas). An integrator may also offer NOC services, as Cinedigm does in the US and XDC does in Europe.

By the standards of giants like AT&T, a theatre-monitoring NOC tends to be fairly small, as my pictures indicate. Still, the purpose is the same. Each projector/ server combination and theatre-management system (essentially a master server) is connected via the internet to the NOC. The NOC monitors the state of the system, so that, for instance, it can keep track of lamp life, parts conditions, net connectivity, and the like. The software can send alerts to the theatre management for upcoming maintenance and can do troubleshooting. It’s also trained to notice problems—glitches in playback, lights going on, dropped subtitles, or whatever. Anomalies are called to the attention of the specialists at the work stations.

The projector manufacturer Christie’s initiated one of the first NOCs in 2003, and it now monitors over 3700 digital screens across the US and Canada. From its California facility it “manages the configuration of systems, provides help-desk services to customer staff, and access to local technicians with local parts to provide on-site repair and support.” The Shenzhen center maintained by GDC, a server company, monitors ten thousand screens. Most NOCs don’t plan programming or chase down encryption keys from distributors, but the NOC maintained by Film-Tech will perform these services as well. It will even power up and down the auditorium. With the Film-Tech system in place, says the company’s brochure, “The projection booth can literally operate for months without anyone ever entering it.”

The show must go on, if remotely

The projection area of the Studio Movie Grill City Centre, Houston, announced as the world’s first completely automated booth.

Now Jimmy and his manager have substantial support, but in turn they’ve shared a lot of information with the NOC. In order to collect the Virtual Print Fee, the exhibitor must play the studio’s film on a contractual basis—for a certain period, a certain number of times per day, and so on.

In earlier times, a dodgy exhibitor might run a film more frequently than was reported back to the distributor, with the exhibitor pocketing the difference. Or an exhibitor might trim shows of a poorly performing title, substituting something more popular and depriving the weak film of playing slots and box-office payback. In the pre-digital days, distributors sent out “checkers,” staff disguised as ordinary moviegoers, to see that theatres were running films according to the booking.

Now the projector/server mating provides real-time screening information to the NOC, and that flows to the distributor. Says an executive at a firm supplying NOC services: