Archive for the 'National cinemas: UK' Category

Scriptography

Hollywood screenwriters at work, according to Boy Meets Girl (1938).

It’s not every conference that opens a morning session by asking the men in the audience to take off their underwear.

But I anticipate.

Last weekend I was a guest of the Screenwriting Resource Network’s fourth annual Screenwriting Research Conference in Brussels. I think that a hell of a time was had by all, and I learned quite a bit, including some reasons why people are interested in screenplays.

Schmucks with Underwoods

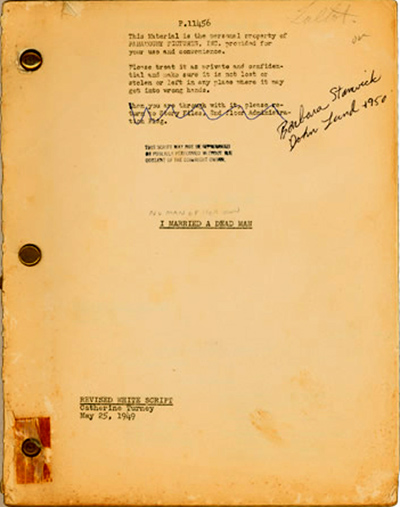

Catherine Turney script for No Man of Her Own (1950).

In my youth, there seemed to be a solemn pact among my peers that we would never study certain areas: censorship, audiences, adaptation (novels into film, particularly), and screenwriting. An earlier generation had, through patient labor, shown decisively that these subjects were dead boring. We, on the other hand, were fired by notions of the director as auteur, and indifferent to what were called “literary” and “sociological” approaches to film. So we triumphantly turned toward The Text—that is, the finished movie.

Things have changed since then. Yet there are still tempting reasons to consider the study of screenwriting a nonstarter if you’re interested in cinema as an art. If you think of the finished film as the achieved artwork, then study of screenplay drafts risks seeming irrelevant. Whatever the screenwriter(s) intended seems irrelevant to the result. So what if six or more screenwriters labored over Tootsie? The movie stands or falls by what we see onscreen.

This was the view presented in Jean-Claude Carrière’s three talks to our group. He suggested that the screenplay is destined to become landfill, and rightly so. It’s like the caterpillar that becomes a butterfly. Once the film has been made, the script has no intrinsic value.

Someone might say, “Wait! We study a painter’s sketches, a novelist’s drafts, or a composer’s early scores. These materials can contribute to understanding the finished work, and sometimes they have an artistic value of their own.” The problem is that in these arts, the preparatory materials are in the same medium as the result. But a script can’t count as a version of the film because prose can’t adequately specify the audiovisual texture of a movie. It’s commonly thought, plausibly, that giving the same script to two directors would result in significantly different films. So the script is at best a series of suggestions for filming, not a sketchy version of the movie. Why not discard it when the film is done?

The study of screenwriting has probably also lain in the shadows because of the proliferation of screenwriting gurus and how-to manuals. Every American over the age of eighteen seems to be writing a screenplay; the Cable Guy who visited me last week was working on two. So all the seminars and advice books have arguably put thinking about screenplays rather close to the amateur-script racket.

Moreover, screenplay studies seem to be part of a broader, paradoxical development in academic film studies. Today scholars have more access to films than ever before, thanks to video, festivals, archives, and the internet. Yet many researchers prefer to talk about everything but the film. More and more scholars want to study just those subjects that my cohort considered dull or irrelevant: censorship and regulation, audiences (composition, demographics, critical reception, fandom), and preproduction factors (storyboards, scripts). In addition, many academics have turned to bigger thematic ideas like film and architecture, film and the city, film and modernity. These trends of research usually make only glancing reference to actual movies, mostly mining them for quick illustrative examples.

In sum, many academics have abandoned the study of film as an artistic medium that finds its embodiment in important works. To get to know particular films more intimately, you increasingly have to go to the Net, to writers like Jim Emerson, Adrian Martin, and other sensitive analytical critics. Talking about screenwriting can seem to be another way of avoiding coming to grips with the intrinsic power of movies.

You can probably tell that one side of me shares some of the biases I’ve listed. But when I remind myself that what people should study aren’t topics but questions, I cheer up quite a bit. For there are, I think, worthwhile questions to be asked about all these areas, screenwriting included. The Brussels event gave some good instances of resourceful, occasionally exciting research into them.

Based on my short acquaintance, most of the research questions seem trained on one of two broad areas: Screenwriting and The Screenplay.

In the trenches

Kinky & Cosy

Screenwriting can be thought of as a practice, a creative activity with both personal and social aspects. How, we might ask, do screenwriters or directors express themselves in the script? How does a media industry recruit, sustain, and reward screenwriters? What are the conventions and constraints at work in a particular screenwriting community?

Questions like this are somewhat familiar to me. When I wrote my first book, on Carl Dreyer, I had to examine his scripts (notably the unproduced Jesus of Nazareth), and that helped me understand his characteristic methods of researching and planning his films. Later, when I collaborated with Kristin and Janet Staiger on The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I recognized a more institutional side of things. We can see from the films of the 1910s that filmmakers were cutting up the space in fresh ways. But this wasn’t a matter of directors simply winging it on the set. Kristin used published manuals and Janet used original screenplays to show that shot breakdowns were planned to a considerable degree before shooting. This habit made production more efficient and controllable.

At the Brussels get-together, Steven Price offered further evidence of this sort, which displayed some of his research on early scenarios for Mack Sennett movies like Crooked to the End (1915). Interestingly, Steven found that sometimes the later version of a continuity script was more laconic than the initial one. Perhaps the gags, once spelled out in the first draft, could be left up to the actors. This is the sort of thing he identified as a “trace” of production practices.

A parallel of sorts emerged in Maria Belodubrovskaya’s paper on screenwriting under Stalin. The Soviets, admiring Hollywood efficiency, tried to come up with a similar system. But their efforts to produce films in bulk were blocked by a censorship apparatus bent on ideological correctness. No surprise there, I guess. But Masha showed convincingly that the very efforts to mimic Hollywood’s “assembly-line” system also discouraged authors from submitting scripts. The writers thought (like many of their LA counterparts) that such a setup denied them creative freedom. In addition, the prospect of story departments providing a stream of screenplays ran afoul of the tradition that gave the director control of the final draft. And the role of producer, as one who could steer the whole process, didn’t exist! So much for the Soviet Hollywood.

What about other media? Sara Zanatta traced out the process of creating Italian TV series. She reviewed some major formats (miniseries, original series, adaptations of foreign series) and then took us through the process of creating individual episodes. Interestingly, it seems that the Italian system, unlike US television, makes the director the boss of it all. Frédéric Zeimat explained how he gained entry to the local screenwriting community through his university education, including work in Luc Dardennes’ workshop at the Free University of Brussels. Eventually he came up with a script that won prizes. He is about to become a showrunner for a sitcom.

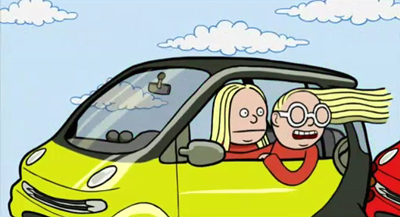

One of the most stimulating panels I heard considered the writing of graphic novels and animation. Richard Neupert explored how recent French animation sustained the tradition of individual authorship while still acceding to some international norms of moviemaking. The cartoonist Nix discussed how he faced new problems in transferring his three-panel comic strip Kinky & Cosy from print to television. TV demanded less written text, especially signs, so that the clips could be exported outside Belgium. More deeply, Nix had to rethink how to pace the action and leave a beat (say, two seconds) after the punchline.

Pascal Lefèvre, one of Europe’s leading experts on comic art, provided a brisk, packed account of the history and practices of scriptwriting for Eurocomics. He described patterns of collaboration, format, and creative choice, placing special emphasis on comics as a spatial art different from cinema. His example was a page from Regis Franc’s ulta-widescreen album Le Café de la plage. Here’s a portion in which two periods of Monroe Stress’s life coexist in a single space. He muses as an adult while his childish self gobbles up food under the guidance of Mom.

Comics space can also change abruptly, as when a window appears in second panel.

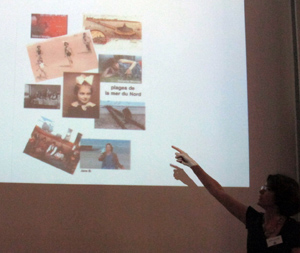

Other papers presented less institutionally fixed, more personal versions of screenwriting as a practice. Kelley Conway’s lecture on Agnes Varda exploited unique access to the filmmaker’s notebooks, scrapbooks, and databases. Kelley showed how Varda conceived three of her documentaries by means of strict categorical structures that were then frayed by digressions born out of the material she shot.

Anna Sofia Rossholm provided something similar for Bergman. Out of the vast Bergman archive she quarried sixty “workbooks,” typically one for each film. Whereas Varda’s books were filled with cutouts and images, Bergman was a word man, treating the books as diaries that recorded “this secret I.” Anna Sofia proposed that in his jottings and planning, Bergman not only communed with himself (calling himself an idiot on occasion) but also explored patterns of doubling akin to those we find in the films. The workbooks evidently held a special place for him: he included their pages in films like Hour of the Wolf and Saraband.

David Lean might be thought of as working in between the Hollywood system and the more personal European milieu. Ian Macdonald suggested that one of Lean’s unfilmed projects sheds light on what he calls screenplay poetics. Macdonald seeks, I think, a principled method for studying the creative process. He does this by tracing how a screen idea is transformed in a series of documents generated by the creative team. The process, he points out, is governed by the participants’ various conceptual frameworks. For Nostromo, Lean solicited two screenwriters and oversaw their rather different versions of the novel. Ian showed that Lean seems to have found solutions to adapting the book by fitting it to the three-act structure advocated by Hollywood artisans, a concrete case of a filmmaker accepting a fresh “poetics” or set of creative constraints.

All of these inquiries could lead to more general thoughts about the creative process in cinema. For some filmmakers, it’s a professional task, undertaken with full knowledge that problems and constraints will have to be dealt with. For others, such as Bergman and Varda, it’s obviously deeply personal, even autobiographical. Perhaps most intimate was the film discussed by Hester Joyce. New Zealand filmmaker Gaylene Preston based Home by Christmas (2010; above) partly on audiotape interviews with her father as he recalled his World War II experiences. Her script reconstructed her interviews with actors, then filled in scenes with documentary footage and scenes she imagined. It’s a family memoir on several levels: Preston’s daughter portrays her own grandmother.

The Screenplay: What is it?

Several of these probes into the creative process raise a more theoretical question. How should we best conceive of the screenplay? As a blueprint? A recipe? An outline? These labels all suggest something disposable preliminary to the real thing, the movie. But why can’t we think of the screenplay as a freestanding object? After all, there are films without screenplays, but there are also screenplays—some written by distinguished authors—that were never made into films. And some of these, like Pinter’s Proust screenplay, are read for their own sake.

In cases like this, should we consider the screenplay a literary genre? And if the screenplay for an unproduced film can be considered a discrete object, what stops us from treating a filmed script in exactly the same way? Moreover, why even speak of a single screenplay, when we know that most commercial films at least go through several drafts? Can’t we consider each one an independent literary text? We’re now far from Carrière’s idea that the script finds its consummation in the finished film and as a piece of writing it should wind up in the ashcan.

And not all screenplays are literary texts. The scrapbooks and databases that Varda accumulates are works of visual art, collages or mixed-media assemblages. Are these merely drafts of the film, or do they have an independent existence or value? We seem to be asking the sort of question that Ted Nannicelli poses in his Ph. D. dissertation. Is there an ontology of the screenplay?

Take a concrete example. Ann Igelstrom’s paper, “Narration in the Screenplay Text,” asked how literary techniques are deployed in the screenplay. When a passage in the script for Before Sunset begins, “We see…,” who exactly is this we? Ann argued that traditional narrative concepts involving the source of the narration, the implied author and implied reader, and the rhetoric of telling can illuminate conventions of screenwriting. Here the screenplay seems definitely a literary text.

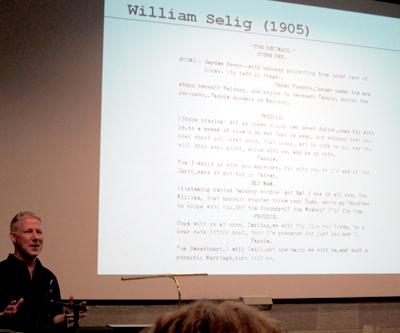

In his keynote address, “The Screenplay: An Accelerated Critical History,” Steven Price (above) declared a more abstract interest in the ontology of the screenplay but proposed that there was no clear-cut way of defining it. Historically, the screenplay takes many forms. Steven pointed out that even in Hollywood, there were many alternative formats, ranging from detailed breakdowns to the “master-scene” method (the option that didn’t specify shots or camera positions). And conceptually, the screenplay carried traces of its original production purposes, as well as other constellations of meaning. (Mack Sennett scripts seem to him part of a Sadean tradition of dehumanized, repetitive recombination.) So if there is a distinctive mode of being of the screenplay, outside of its role in production, it will turn out to be a messy one.

Envoi

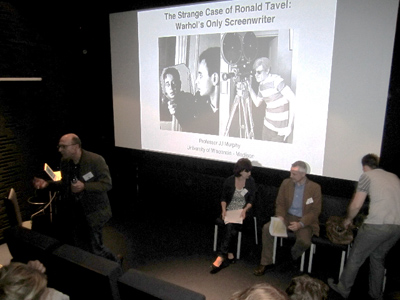

J. J. Murphy presents a paper on Ronald Tavel. Photo courtesy Richard Neupert.

If we conceive studies of screenplay and screenwriting as revolving around specific research questions, those of us interested in film as art can learn a lot. If our interests are in film history, researchers can show how organizations of production and individual choices by screenwriters/directors can shape the final product. For those of us interested in more theoretical explorations, asking about the nature and “mode of being” of the screenplay can’t help but make us think more about the ontology of cinema itself.

And if we want to know films more intimately, being aware of the creative choices that were made by the filmmakers throws a spotlight on aspects of the film we might otherwise not notice. It’s all very well to say we’ll examine the film “in itself,” but our attention is invariably selective. Knowledge of behind-the-scenes decisions can sharpen our awareness of artistic matters. Anna Sofia’s research on Bergman, like Marja-Riitta Koivumäki’s paper on Tarkovsky’s screenplay for My Name Is Ivan, activates parts of the film for special notice.

Because there were split sessions at the conference, and because I was plagued by jet lag, I couldn’t attend every panel and talk. I regret missing papers I later heard were very fine, and I haven’t written up everything I heard. I haven’t sufficiently talked about screenwriting pedagogy, represented in papers like Lucien Georgescu’s dramatic appeal to rethink whether screenwriting should be taught in film schools, or Debbie Danielpour’s stimulating survey of her methods of teaching genre scripting. So this is just a small sample of what these folks are up to. But you can tell, I think, that they’re posing questions at a level of sophistication that my 1960s cohort couldn’t have envisioned. Despite what the cynics say, there is progress in academic work.

As for men’s underpants: All is explained here.

I’m grateful to conference organizers Ronald Geerts and Hugo Vercauteren for inviting me to speak at the gathering. I must also thank conference organizer and old friend Muriel Andrin, along with Dominique Nasta and their colleagues and students from the Arts du Spectacle Department at the Université Libre de Bruxelles. My friends at the Cinematek, Stef and Bart and Hilde, helped me with my PowerPoint. Thanks as well to the Universitaire Associatie Brussel (Vrije Universiteit Brussel / Rits-Erasmushogeschool Brussel) and Associatie KULeuven (MAD-Faculty / Sint Lukas Brussel). A high point of the event was the visit to La Fleur en Papier Doré. Special thanks to Gabrielle Claes for her heartfelt introduction to my talk, not to mention a delicious bucket of moules.

A founding document in the contemporary study of the screenplay is Claudia Sternberg’s Written for the Screen: The American Motion-Picture Screenplay as Text (Stauffenburg, 1997). Other books central to the conference cohort include Steven Maras’s Screenwriting: History, Theory, and Practice, Steven Price’s The Screenplay: Authorship, Theory and Criticism, J. J. Murphy’s Me and You and Memento and Fargo: How Independent Screenplays Work, and Jill Nelmes’s anthology Analysing the Screenplay, which includes many essays by members of the group. See also the affiliated Journal of Screenwriting.

For more information on the Screenwriting Research Network, go here. (Thanks to Ian Macdonald for the link.) The next conference will be held in Sydney, and the 2013 one will take place in Madison, Wisconsin.

P.S. 22 Sept 2011: A panel discussion with Jean-Claude Carrière held during the conference is available here. Although the site is in Dutch, the discussion is in English. Thanks to Ronald Geerts for the information.

P.P.S. Thanks to Joonas Linkola for a spelling correction!

Coke does go through you pretty fast. Richard Neupert at a Coca-Cola machine that exploits a Brussels landmark.

Slumdogged by the past

DB here:

In graduate school a professor of mine claimed that one benefit of studying film history was that “you’re never surprised by anything that comes along.”

This isn’t something to tell young people. They want to be surprised, preferably every few hours. So I rejected the professor’s comment, and I still think it’s not a solid rationale for studying film history. But I can’t deny that doing historical research does give you a twinge of déjà vu.

For instance, the film industry’s current efforts to sell Imax and 3-D irresistibly remind me of what happened in the early 1950s, when Hollywood went over to widescreen (Cinerama, CinemaScope, and the like), stereophonic sound, and for a little while 3-D. Then the need was to yank people away from their TV sets and barbecue pits. Now people need to be wooed from videogames and the Net. But the logic is the same: Offer people something they can’t get at home. It’s 1953 once more.

So historians can’t resist the “Here we go again” reflex. But they shouldn’t turn that into a languid “I’ve seen it all before.” Because we can genuinely be surprised. Occasionally, there are really innovative movies that, no matter how much they owe to tradition, constitute milestones. In my view, Kiarostami’s Through the Olive Trees, Hou’s City of Sadness, Wong’s Chungking Express, Tarr’s Satantango, and Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction are among the 1990s examples of strong and original works.

More often, the films we see draw on film history in milder ways than these milestones. But this doesn’t mean that these movies lack significance or impact. We can be agreeably surprised by the ways in which a filmmaker energizes long-standing cinematic traditions by blending them unexpectedly, tweaking them in fresh ways, setting them loose on new material. And the more you know of those traditions and conventions, the more you can appreciate how they’re modified. Admiring genius shouldn’t keep us from savoring ingenuity.

Which brings me to Slumdog Millionaire. I happen to like the film reasonably well. Part of my enjoyment is based on seeing how forms and formulas drawn from across film history have an enduring appeal. Many people whose judgments I respect hate the movie, and they would probably call what follows an ode to clichés. But I mean this set of notes in the same spirit as my comments on The Dark Knight (which I don’t admire). Even if you disagree with my predilections, you may find something intriguing in Slumdog’s ties to tradition. These ties also suggest why the movie is so ingratiating to so many.

Warning: What follows contains plot spoilers, revelatory images, and atrocious puns.

Slumdog and pony show

Adaptation is still king. Almost as soon as movies started telling stories, they were borrowing from other media. Many of this year’s Oscar candidates are based on plays, novels, and graphic novels. Slumdog is a redo of Vikas Swarup’s 2005 novel Q & A. The book provides the basic situation of a poor youth implausibly triumphing on a version of Who Wants to be a Millionaire? The novel also lays down the film’s overall architecture: in the present, the hero narrates his past, tying each flashback to a round of the game and a relevant question. In the novel, the video replays are described, but of course they’re shown in the film.

There are many disparities between novel and movie, but for now I simply note two. First, Swarup’s book has several minor threads of action, but the film concentrates on Jamal’s love of Latika. (The screenwriter Simon Beaufoy has melded two female characters into one.) Correspondingly, the book introduces a romance plot comparatively late, whereas the film initiates Jamal’s love of Latika in their childhoods. Such choices give the film a simpler through-line. Second, whereas Q & A skips back and forth through Jamal’s life, keying story events to the quiz questions, the film’s flashbacks follow the chronology strictly. This is a good example of how screenwriters are inclined to adjust the plasticity of literary time to the fact that, at least in theatrical screenings, audiences can’t stop and go back to check story order. Clarity of chronology is the default in classical film storytelling.

Then there’s the double plotline. The streamlining of Swarup’s novel points up one convention of Hollywood narrative cinema. The assortment of characters and the twists in the original novel are squeezed down to the two sorts of plotlines we find in most studio films: a line of action involving heterosexual romance and a second line of action, sometimes another romance but just as often involving work. The common work/ family tension of contemporary film plotting is to some extent built into the Hollywood system.

Beaufoy has sharpened the plot by giving Jamal a basic goal: to unite with Latika. The quiz episodes form a means to that end: the boy goes on the show because he knows she watches it. If told in chronological order, the quiz-show stretches would have come late in the film and become a fairly monotonous pendant to the romance plot. One of the many effects of the flashback arrangement is to give the subsidiary goal more prominence, creating a parallel track for the entire film to move along and arousing anomalous suspense. (We know the outcome, but how do we get there?)

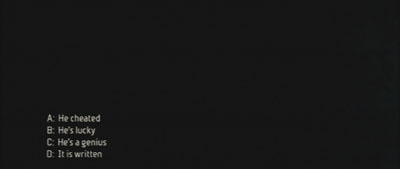

Q & A. Swarup’s novel begins: “I have been arrested. For winning a quiz show.”

We have to ask: What could make such a thing happen? Soon the police and the show’s producers are wondering something more specific. How could Ram, an ignorant waiter, have gotten the answers right without cheating?

Noël Carroll proposes that narratives engage us by positing questions, either explicitly or implicitly. Stories in popular media, he suggests, induce the reader to ask rather clear-cut ones, and these will get reframed, deferred, toyed with, and in the short or long run answered.

Slumdog accepts this convention, presenting a cascade of questions to link its scenes and enhance our engagement. Will Jamel and Salim get Bachchan’s autograph? Will they survive the anti-Muslim riot? Will they escape the fate of the other captive beggar children? And so on.

More originally, the film cleverly melds the question-based appeal of narrative with the protocols of the game show, so that we are confronted with a multiple-choicer at the very start. (As in narrative itself, the truth comes at the end.) The principal question will be answered in the denouement, in a comparably impersonal register.

Flashbacks are also a long-standing storytelling device, as I was saying here last week. A canonical situation is the police interrogation that frames the past events, as in Mildred Pierce, The Usual Suspects, and Bertolucci’s The Grim Reaper. This narrating frame is comfortable and easy to assimilate, and it guides us in following the time shifts.

But 1960s cinema gave flashbacks a new force. From Hiroshima mon amour (1958) onward, brief and enigmatic flashbacks, interrupting the ongoing present-tense action, became common ways to engage the audience. Such is the case with the glimpse of Latika at the station that pops up during the questioning of Jamal, rendered as almost an eyeline match.

At this point we don’t know who she is, but the image creates curiosity that the story will eventually satisfy. Flashbacks can also remind us of things we’ve seen before, as when Jamal recalls, obsessively, the night he and Salim left Latika behind to Maman’s band. Boyle and company call on these time-honored devices in the assurance that wewill pick up on them immediately, as audiences have for decades.

Flashforwards are trickier, and rarer. The 1960s also saw some experimentation with images from future events interrupting the story’s present action. Unless you posit a character who can see the future, as in Don’t Look Now, flashforwards are usually felt as externally imposed, the traces of a filmmaker teasing us with images that we can’t really assimilate at this point. (See They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?) Such flashforwards pop up during the initial police torture of Jamal.

Encountering the bathtub shot so early in the film, we might take it as a flashback, but actually it anticipates a striking image at the climax, after Jamal has been released and returned to the show. I’d argue that the shot functions thematically, as a vivid announcement of the motif of dirty money that runs through the movie and is associated with not only the gangster world but also the corrupt game show.

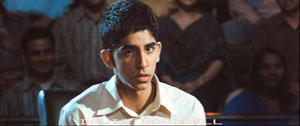

Slumdog days

Empathy. One of the most powerful ways to get the audience emotionally involved is to show your protagonist treated unfairly. This happens in spades at the start of Slumdog. A serious-faced boy is subjected to awful torture, then he’s intimidated by unfeeling men in authority. He’s mocked as a chaiwallah by the unctuous host of the show, and laughed at by the audience. Once Jamal’s backstory starts, we see him as a kid (again running up against the law) and suffering a variety of miseries.

To keep Jamal from seeming a passive victim, he is given pluck and purpose. As a boy he resists the teacher, boldly jumps into human manure, shoves through a crowd to get an autograph, and eventually becomes a brazen freelance guide to the Taj Mahal. This is the sort of tenacious, resourceful kid who could get on TV and find Salim in teeming Mumbai. The slumdog is dogged.

Our sympathies spread and divide. Latika is also introduced being treated unfairly. An orphan after the riot, she squats in the rain until Jamal makes her the “Third Musketeer.” By contrast, Salim is introduced as a hard case—making money off access to a toilet, selling Jamal’s Bachchan autograph, resisting bringing Latika into their shelter, and eventually becoming Maman’s “dog” and Latika’s rapist. The double plotline gives us a hero bent on finding and rescuing his beloved; the under-plot gives us a shadier figure who finds redemption by risking his life a final time to help his friends. Jamal emerges ebullient from a sea of shit, but Salim dies drowned in the money he identified with power.

Our three main characters share a childhood, and what happens to them then prefigures what they will do as grownups. This is a long-standing device of classical cinema, stretching back to the silent era. Public Enemy and Angels with Dirty Faces give us the good brother and the bad brother. Wuthering Heights, Kings Row, and It’s a Wonderful Life present romances budding in childhood. These are plenty of less famous examples. Here, for instance, is a synopsis of Sentimental Tommy (1921), a film that may no longer exist.

The people of Thrums ostracize Grizel, a child of 12, and her mother, known as The Painted Lady, until newcomer Tommy Sandys, a highly imaginative boy, comes to the girl’s rescue and they become inseparable friends. Six years later Tommy returns from London, where he has achieved success as an author, and finds that Grizel still loves him. In a sentimental gesture he proposes, but she, realizing that he does not love her, rejects him. In London, Tommy is lionized by Lady Pippinworth, and he follows her to Switzerland. Having lost her mother and believing that Tommy needs her, Grizel comes to him but is overcome by grief to see his love for Lady Pippinworth. Remorseful, Tommy returns home, and after his careful nursing Grizel regains her sanity.

The device isn’t unknown in Indian cinema either; Parinda (1989) motivates the character relationships through actions set in childhood. Somehow, we are drawn to seeing one’s lifetime commitments etched early and fulfilled in adulthood.

This story pattern carries within it one of the great thematic oppositions of the cinema, the tension between destiny and accident. In Slumdog, The Three Musketeers may be introduced casually, but it will somehow provide a template for later events. Lovers are destined to meet, even if by chance, and when chance separates them, they are destined to reunite . . . if only by chance. A plot showing children together assures us that somehow they will re-meet, and their childhood traits and desires will inform what they do as adults. It is written.

This theme reaffirms the psychological consistency prized by classic film dramaturgy as well. Characters are introduced doing something, as we say, “characteristic,” and this first impression becomes all the more ingrained by the sense that things had to be this way. What you choose—say, to pursue the love of your childhood—manifests your character. But then, your character was already defined with special purity in that childhood.

Just another movie conceit? The existence of Classmates.com seems to suggest otherwise.

Chance needs an alibi, however. Hollywood films are filled with coincidences, and the rules of the game suggest that they need some minimal motivation. Not so much at the beginning, perhaps, because in a sense every plot is launched by a coincidence. But surely, our plausibilists ask, how could it happen that an uneducated slumdog would have just the right experiences to win the quiz? A lucky guy!

As Swarup realized, the flashback structure helps the audience by putting past experience and present quiz question in proximity for easy pickup. Yet as Beaufoy indicates in one of the most informative screenwriting interviews I know, the device also softens the impression of an outlandishly lucky contestant. At the start we already know that Jamal has won, so the question for us is not “How did he cheat?” but rather “What life experience does the question tap?” Each of the links is buried in a welter of other details, any one of which could tie into the correct answer. Moreover, sometimes the question asked precedes the relevant flashback, and sometimes it follows the flashback, further camouflaging the neat meshing of past and present.

It’s a diabolical contrivance. If you question Jamal’s luck, you ally with the overbearing authorities who suspect cheating. (You just think the film cheated.) Who wants to side with them? By the end the inevitability granted by the flashback obliges us to accept the inspector’s conclusion: “It is bizarrely plausible.”

The film has an even more devious out. Jamal can reason on his own, arriving at the Cambridge Circus answer. More important, his street smarts have made him such a good judge of character that he realizes that the MC is misleading him about the right answer to the penultimate question. So his winning isn’t entirely coincidence. Life experience has let him suss out the interpersonal dynamics behind the apparently objective game. As for the final answer—a lucky guess? Fate?—it’s a good example of how things can be written (in this case by Alexandre Dumas).

Slumdoggy style

The whole edifice is built on a cinematic technique about a hundred years old: parallel editing. Up to the climax, we alternate between three time frames. The police interrogation takes place in the present, the game show in the recent past (shifting from the video replay to the scenes themselves), and Jamal’s life in the more distant past. Any one of these time streams may be punctuated, as we’ve seen, by brief flashbacks. So the problem is how to manage the transitions between scenes in any one time frame and the transitions among time frames.

Needless to say, our old friend the hook—in dialogue, in imagery—is pressed into service often. A sound bridge may link two periods, with the quiz question echoing over a scene in the past. “How did you manage to get on the show?” Cut to Jamal serving tea in the call center. In a particularly smooth segue, the boys are thrown off the train as kids and roll to the ground as teenagers. There are negative hooks too. At the end of a quarrel with Salim, Jamal walks off saying, “I will never forgive you.” The next scene opens with the two of them sitting on the edge of an uncompleted high-rise building, having come to an uneasy truce.

In the climax, the three time frames all come into sync, creating a single ongoing present. Jamal will return to the show. The double-barreled questions are reformulated. Now we have genuine suspense: Will he win the top prize? Will Latika find him? To pose these engagingly, directors Danny Boyle and Loveleen Tandan create an old-fashioned chase to the rescue.

Each major character gets a line of action, all unwinding simultaneously: Salim prepares to sacrifice himself to the gangster Khan, she flees through traffic, and Jamal enters the contest’s final round. A fourth line of action is added, that of the public intensely following Jamal’s quest for a million. He has become the emblem of the slumdog who makes good.

The rescue doesn’t come off; Latika misses Jamal’s phone plea for a lifeline, and he is on his own. Fortunately, he trusts in luck because “Maybe it’s written, no?” The lovers reunite instead at the train station, where Jamal had pledged to wait for Latika every day at 5:00. Fitting, then, that in the epilogue a crowd shows up, standing in for all of Mumbai, singing and dancing to “Jai Ho” (“Victory”). All the remaining lines of action—Jamal, Latika, and the multitudes—assemble and then disperse in a classic ending: lovers turning from the camera and walking into their future, leaving us behind.

Then there’s the film’s slick technique. The whole thing is presented in a rapid-fire array, with nearly sixty scenes and about 2700 shots bombarding us in less than two hours. Critics both friendly and hostile have commented on the film’s headlong pacing and flamboyant pictorial design. If some of Slumdog’s storytelling strategies reach back to the earliest cinema, its look and feel seems tied to the 1990s and 2000s. We get harsh cuts, distended wide-angle compositions, hurtling camerawork, canted angles, dazzling montage sequences, faces split by the screen edge, zones of colored light, slow motion, fast motion, stepped motion, reverse motion (though seldom no motion). The pounding style, tinged with a certain cheekiness, is already there in most of Danny Boyle’s previous work. Like Baz Luhrmann, he seems to think that we need to see even the simplest action from every conceivable angle.

Yet the stylistic flamboyance isn’t unique to him. He is recombining items on the menu of contemporary cinema, as seen in films as various as Déjà Vu and City of God. (That menu in turn isn’t absolutely new either, but I’ve launched that case in The Way Hollywood Tells It.) More surprisingly, we find strong congruences between this movie’s style and trends in Indian cinema as well.

Over the last twenty years Indian cinema has cultivated its own fairly flashy action cinema, usually in crime films. Boyle has spoken of being influenced by two Ram Gopal Varma films, Satya (1998) and Company (2002). Company‘s thrusting wide angles, overhead shots, and pugilistic jump cuts would be right at home in Slumdog.

It seems, then, that Slumdog’s glazed, frenetic surface testifies to the globalization of one option for modern popular cinema. The film’s style seems to me a personalized variant of what has for better or worse become an international style.

Slumdogma

Boot Polish.

I’d like to mention many other ways in which the movie engages viewers, such as running (an index of popular cinema; does anybody run in Antonioni?). But I’ve said enough to suggest that the film is anchored in film history in ways that are likely to promote its appeal to a broad audience. The idea of looking for appeals that cross cultures rather than divide them isn’t popular with film academics right now, but a new generation of scholars is daring to say that there are universals of representation and response. It is these that allow movies to arouse similar emotions across times and places.

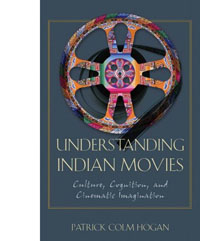

Patrick Hogan has made such a case in his fine new book Understanding Indian Movies: Culture, Cognition, and Cinematic Imagination. There he shows that much of what seems exotic in Indian cinema constitutes a local specification of factors that have a broad reach—certain plot schemes, themes, and visual and auditory techniques. Hogan, an expert in Indian history and culture, is ideally placed to balance universal appeals with matters of local knowledge that require explication for outsiders.

For my part, I’d just mention that a great deal of what seems striking in Slumdog has already been broached in Indian cinema. Take the matter of police brutality. The torture scene at the start might seem a piece of exhibitionism, with an outsider (Boyle? Beaufoy?) twisting local culture to western ideas of uncivilized behavior. But look again at the gangster films I’ve mentioned: they contain brutal scenes of police torture, like this from Company.

Like Hong Kong cinema and American cinema, Indian filmmaking seems to take a jaundiced view of how faithful peace officers are to due process.

More basically, consider the representation of the Mumbai slums. Doubtless the title slants the case from the first; Beaufoy claims to have invented the word “slumdog,” though Ram is called a dog at one point in the novel. The insult, and the portrayal of Mumbai, has made some critics find the film sensationalistic and patronizing. Most frequently quoted is megastar Amitabh Bachchan’s blog entry.

If SM projects India as [a] Third World dirty underbelly developing nation and causes pain and disgust among nationalists and patriots, let it be known that a murky underbelly exists and thrives even in the most developed nations.

Soon Bachchan explained that he was neutrally summarizing the comments of correspondents, not expressing his own view. In the original, he seems to have been suggesting that the poverty shown in Slumdog is not unique to India, and that a film portraying poverty in another country might not be given so much recognition.

It’s an interesting point, although many films from other nations portray urban poverty. More generally, Indian criticisms of the image of poverty in Slumdog remind me of reactions to Italian Neorealism from authorities concerned about Italy’s image abroad. The government undersecretary Giulio Andreotti claimed that films by Rossellini, De Sica, and others were “washing Italy’s dirty linen in public.” Andreotti wrote that De Sica’s Umberto D had rendered “wretched service to his fatherland, which is also the fatherland of . . . progressive social legislation.” Liberal American films of the Cold War period were sometimes castigated by members of Congress for playing into the hands of Soviet propagandists. It seems that there will always be people who consider films portraying social injustice to be too negative and failing to see the bright side of things, a side that can always be found if you look hard enough.

Moreover, Neorealists made a discovery that has resonated throughout festival cinema: feature kids. Along with sex, a child-centered plot is a central convention of non-Hollywood filmmaking, from Shoeshine and Germany Year Zero through Los Olvidados and The 400 Blows up to Salaam Bombay, numerous Iranian films, and Ramchandi Pakistani. Yes, Slumdog simplifies social problems by portraying the underclass through children’s misadventures, but this narrative device is a well-tried way to secure audience understanding. We have all been children.

There is another way to consider the poverty problem. The representation of slum life, either sentimentally or scathingly, can be found in classic Indian films of the 1950s. One of my favorites of Raj Kapoor’s work, Boot Polish (1954), tells a Dickensian tale of a brother and sister living in the slums before being rescued by a rich couple. (Interestingly, the key issue is whether to beg or do humble work.) Another example is Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zamin (Two Acres of Land, 1953). Later, shantytown life was more harshly presented in Chakra (1981), shot on location.

And of course poverty in the countryside has not been overlooked by Indian filmmakers.

Slumdog may have become a flashpoint because more recent Indian cinema has avoided this subject. In an email to me Patrick Hogan (who hasn’t yet seem Slumdog) writes:

There was a strong progressive political orientation in Hindi cinema in the 1940s and 1950s. This declined in the 1960s until it appeared again with some works of parallel cinema. Thus there was a greater concern with the poor in the 1950s–hence the movies by Kapoor and Roy that you mention. There are some powerful works of parallel cinema that treat slum life, but they had relatively limited circulation. On the other hand, that does not mean that urban poverty disappeared entirely from mainstream cinema. At least some sense of social concern seemed to be retained in mainstream Indian culture, thus mainstream cinema, until the late 1980s.

However, at that time Nehruvian socialism was more or less entirely abandoned and replaced with neo-liberalism. In keeping with this, ideologies changed. Perhaps because the consumers of movies became the new middle classes in India and the Diaspora, there was a striking shift in what classes appeared in Hindi cinema and how classes were depicted. As many people have noted, films of the neoliberal period present images of fabulously wealthy Indians and generally focus on Indians whose standard of living is probably in the top few percentage points. . . . I don’t believe this is simply a celebration of wealth and pandering to the self-image of the nouveau riche–though it is that. I believe it is also a celebration of neoliberal policies. Neoliberal policies have been very good for some people. But they have been very bad for others. . . .

However, at that time Nehruvian socialism was more or less entirely abandoned and replaced with neo-liberalism. In keeping with this, ideologies changed. Perhaps because the consumers of movies became the new middle classes in India and the Diaspora, there was a striking shift in what classes appeared in Hindi cinema and how classes were depicted. As many people have noted, films of the neoliberal period present images of fabulously wealthy Indians and generally focus on Indians whose standard of living is probably in the top few percentage points. . . . I don’t believe this is simply a celebration of wealth and pandering to the self-image of the nouveau riche–though it is that. I believe it is also a celebration of neoliberal policies. Neoliberal policies have been very good for some people. But they have been very bad for others. . . .

In this neoliberal cinema (sometimes misleadingly referred to as “globalized”), even relatively poor Indians are commonly represented as pretty comfortable. The difference in attitude is neatly represented by two films by Mani Ratnam—Nayakan (1987) and Guru (2007). The former is a representation of the difficulties of the poor in Indian society. The film already suffers from a loss of the socialist perspective of the 1950s films. Basically, it celebrates an “up from nothing” gangster for Robin Hood-like behavior. (This is an oversimplification, but gives you the idea.)

Guru, by contrast, celebrates a corrupt industrialist who liberates all of India by, in effect, following neoliberal policies against the laws of the government. Neither film offers a particularly admirable social vision. But the former shows the urban poor struggling against debilitating conditions. The latter simply shows a sea of happy capitalists and indicates that lingering socialistic views are preventing India from becoming the wealthiest nation in the world. Part of the propaganda for neoliberalism is pretending that poor people don’t exist any longer–or, if they do, they are just a few who haven’t yet received the benefits.

Paradoxically, then, perhaps local complaints against Slumdog arise because the film took up a subject that hasn’t recently appeared on screens very prominently. The same point seems to be made by Indian commentators and by Indian filmmakers who deplore the fact that none of their number had the courage to make such a movie. The subject demands more probing, but perhaps the outsider Boyle has helped revive interest in an important strain of the native tradition!

Finally, the issue of glamorizing the exotic. Some critics call the film “poverty porn,” but I don’t understand the label. It implies that pornography of any sort is vulgar and distressing, but which of these critics would say that it is? Most such critics consider themselves worldly enough not to bat an eye at naughty pictures. Some even like Russ Meyer.

So is the issue that the film, like pornography, prettifies and thereby falsifies its subject? Several Indian films, like Boot Polish, have portrayed poverty in a sunnier light than Slumdog, yet I’ve not heard the term applied to them. Perhaps, then, the argument is that pornography exploits eroticism for money, and Slumdog exploits Indian culture. Of course every commercial film could be said to exploit some subject for profit, which would make Hollywood a vast porn shop. (Some people think it is, but not typically the critics who apply the porn term to Slumdog.) In any case, once any commercial cinema falls under the rubric of porn, then the concept loses all specificity, if it had any to begin with.

The Slumdog project is an effort at crossover, and like all crossovers it can be criticized from either side. And it invites accusations of imperialism. A British director and writer use British and American money to make a film about Mumbai life. The film evokes popular Indian cinema in circumscribed ways. It gets a degree of worldwide theatrical circulation that few mainstream Indian films find. This last circumstance is unfair, I agree; I’ve long lamented that significant work from other nations is often ignored in mainstream US culture (and it’s one reason I do the sort of research I do). But I also believe that creators from one culture can do good work in portraying another one. No one protests that that Milos Forman and Roman Polanski, from Communist societies, made One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Chinatown. No one sees anything intrinsically objectionable in the Pang brothers or Kitano Takeshi coming to America to make films. Most of us would have been happy had Kurosawa had a chance to make Runaway Train here. Conversely, Clint Eastwood receives praise for Letters from Iwo Jima.

Just as there is no single and correct “Indian” or “American” or “French” point of view on anything, we shouldn’t deny the possibility that outsiders can present a useful perspective on a culture. This doesn’t make Slumdog automatically a good film. It simply suggests that we shouldn’t dismiss it based on easy labels or the passports of its creators.

Moreover, it isn’t as if Boyle and Tandan have somehow contaminated a pristine tradition. Indian popular films have long been hybrids, borrowing from European and American cinema on many levels. Their mixture of local and international elements has helped the films travel overseas and become objects of adoration to many westerners.

I believe we should examine films for their political presuppositions. But those presuppositions require reflection, not quick labels. If I were to sketch an ideological interpretation of Slumdog, I’d return to the issue of how money is represented in an economy that traffics in maimed children, virgins, and robotic employees. Money is filthy, associated with blood, death, and commercial corruption. The beggar barracks, the brothel, the call center, and the quiz show lie along a continuum. So to stay pure and childlike one must act without concern for cash. The slumdog millionaire doesn’t want the treasure, only the princess, and we never see him collect his ten million rupees. (An American movie loves to see the loser write a check.) To invoke Neorealism again, we seem to have something like Miracle in Milan–realism of local color alongside a plot that is frankly magical.

Perhaps this quality supports the creators’ claims that the film is a fairy tale. As with all fairy tales, and nearly all movies I know, dig deep enough and you’ll find an ideological evasion. Still, that evasion can be more or less artful and engrossing.

So it seems to me enlightening and pleasurable to see every film as suspended in a web, with fibers connecting it to different traditions, many levels and patches of film history. Acknowledging this shows that most traditions aren’t easily exhausted, and that fresh filmmaking tactics can make them live again. Thinking historically need not numb us to surprises.

The amount of Web writing on Slumdog is exploding. Go to GreenCine for a good sampling of commentary from late 2008. The film’s technique is discussed in Stephanie Argy, “Rags to Riches,” American Cinematographer 89, 12 (December 2008), 44-61. Boyle shows his camera to Darren Aronofsky at Slantfilm. Kim Voynar of Movie City News reviews, critically, the Slumdog backlash.

For a more detailed rationale for this entry’s suspension of value judgments for the sake of analysis, try my earlier blog entry here. Noël Carroll discusses question-and-answer structures in narrative in several books, notably The Philosophy of Horror; or, Paradoxes of the Heart (New York: Routledge, 1990), 130-136. On recent Indian action movies, see Lalitha Gopalan, Cinema of Interruptions: Action Genres in Contemporary Indian Cinema (London: British Film Institute, 2002). The quotations from Giulio Andreotti come from P. Adams Sitney, Vital Crises in Italian Cinema: Iconography, Stylistics, Politics (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1995), 107; and Millicent Marcus, Italian Film in the Light of Neorealism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), 26.

Thanks to Cathy Root, who is at work on a book on Bollywood, for advice and links. Thanks as well to Patrick Colm Hogan and Lalita Pandit for corrections, information, and ideas.

PS 2 Feb: David Chute, expert on Indian cinema, has written a helpful and balanced entry on Slumdog at his Hungry Ghost site.

PPS 14 Feb: From another expert on Indian film, Corey Creekmur, at the University of Iowa, some further ideas and references on the childhood motif:

I would emphasize that establishing a film’s narrative direction through childhood events is a dominant narrative trope in popular Indian cinema, animating many famous “golden age” examples, including Raj Kapoor’s Awara (1951), Mehboob Khan’s Anmol Ghadi (1946), and Bimal Roy’s Devdas (1955), along with a number of the major 1970s films starring Amitabh Bachchan, which often carry childhood traumas into the adult character’s life. The story of brothers growing up on two sides of the law is also a Hindi film staple, central to Bachchan’s emergence as a superstar in Deewar in 1975. It seems to me curious that Slumdog Millionaire’s Western filmmakers draw on these conventions more fully than the source novel [Q & A] by a non-resident Indian does.

I attempt to explain the decades-long cultural function (and eventual waning) of this narrative trope — often achieved through a specific formal device (a dissolve from boy to man) moving from the lives of children to adults (skipping over adolescence) that I call the “maturation dissolve” — in an article “Bombay Boys: Dissolving the Male Child in Popular Hindi Cinema,” in Where the Boys Are: Cinemas of Boyhood, ed. Murray Pomerance and Frances Gateward. (Detroit: Wayne State UP, 2004). In that essay I suggest that some of the Hollywood examples — as well as Citizen Kane — you mention could have inspired the Indian examples, but also suggest certain Indian sources (the childhood love of the god Krishna and his consort Radha, which informs all versions of Devdas) as well. Since I’m citing myself, I’ll also note a recent essay on the “Devdas” phenomenon in Indian cinema: “Remembering, Repeating, and Working Through Devdas,” which appears in Indian Literature and Popular Cinema: Recasting Classics, ed. Heidi R. M. Pauwels (Routledge, 2008). By the way, you might also enjoy a website devoted to popular Hindi cinema by my colleague Philip Lutgendorf (with whom I regularly teach Indian cinema classes). Most of the entries on his site are his, but as you will note, sometimes he lets me put my two cents in there as well: http://www.uiowa.edu/~incinema/

PPPS 21 February: Several scholars comment on the film’s representation of the Dahravi neighborhood and the multilayered significance of Indian protests against Slumdog. See today’s New York Times here and here.

Vancouver wrapup (long-play version)

Our final post from this year’s Vancouver International Film Festival. Plenty to talk about, so today you get your money’s worth. Oh, wait….it’s free. So you definitely get your money’s worth.

Kristin here—

East

If Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf have been the most prestigious Iranian directors, with their features prominent at film festivals, Majid Majidi has been among the most popular. His Children of Heaven (1997) and The Color of Paradise (1999) both had international success, perhaps largely due to their focus on children and their sentimental, heartwarming stories. The Song of Sparrows (above, 2008) represents a pleasant development and is the best Majidi film I’ve seen. It’s still sentimental and heartwarming, but there’s also a great deal of humor and some highly imaginative situations that give the film more originality than the director’s earlier work.

For a start, the film puts children into supporting roles and sticks continuously with Karim, a hard-working father who strives to make extra money to replace his daughter’s hearing aid. Initially Karim works at an ostrich farm, a completely unexpected locale that generates considerable humor—until one ostrich escapes and Karim loses his job. His one asset is his motorcycle, which he turns into a cab in nearby Tehran, thereby earning good money. Meanwhile his mischievous son and his friends dream of dredging a covered pond near their village and making money by filling it with goldfish to sell.

The triumphs and obstacles that Karim and his son meet make up the bulk of the story, though the life of the tiny cluster of houses in which the main family and their neighbors dwell is charmingly depicted.

The plot of Under the Bombs involves a Lebanese divorcée returning from abroad to search for her sister  and son just after the 2006 war between Hezbollah and Israel. Only one taxi driver is willing to drive her into the southern region, where bombing could re-erupt at any time; he’s from that area himself, and he’s also attracted to Zeina. This simple story, however, is not half as compelling as the environment in which it takes place.

and son just after the 2006 war between Hezbollah and Israel. Only one taxi driver is willing to drive her into the southern region, where bombing could re-erupt at any time; he’s from that area himself, and he’s also attracted to Zeina. This simple story, however, is not half as compelling as the environment in which it takes place.

The film opens abruptly with extreme long shots of bombs going off among residential blocks, and as the two main characters travel through scenes of devastation, there is a vivid sense of the action being staged as the events depicted were actually unfolding. One scene depicts French NATO troops landing with the first relief supplies; another shows coffins being dug out of a mass grave and handed over to grieving family members.

Director Philippe Aractingi manages to convey something of the sense of outrage that news coverage of the Hurricane Katrina disaster did in the U.S. As Zeina questions shelter inhabitants about her lost relatives, they tell their tales of losing their entire families and of being separated from loved ones. We can’t tell whether these people may be actors or actual people who have suffered the losses they describe, but a cumulative sense of outrage emerges at the Israelis’ willingness to attack residential areas in their fight against terrorists.

West

Last time I wrote about films from Haiti and Jordan. The festival continued to offer films from countries that have had little or no regular production. El Camino (2007) hails from Costa Rica, though its director, Ishtar Yasin, is Chilean-Iraqi. The narrative is spare, though not in the enigmatic art-cinema fashion of Eat, for This Is My Body. We are introduced to 12-year-old Saslaya and her younger, mute brother Dario. They live with their grandfather in a shack and scavenge in the local dump. The grandfather sexually abuses Saslaya, and the children set out to find their mother. We watch their journey progress in typical picaresque fashion as they meet people, witness a puppet show put on by a vaguely sinister old man, and wander the streets of the local town. Yet we don’t learn where their mother is, why and when she left. The exposition is minimal, as is the dialogue. Watching El Camino, one becomes aware of how much talk most films contain, since the siblings don’t talk to each other or anyone else.

Finally, nearly 70 minutes into a 91-minute film, the children take a ferry. There the other passengers exchange stories about why they are traveling. Gradually we learn that the early part of the film was set in poverty-stricken Nicaragua, and these people are trying to enter Costa Rica illegally to find work. Saslaya reveals that her mother had left with that goal eight years earlier, after their father died. At last we get some sense of the situation, but the pair’s progress is interrupted once the group goes ashore and are shot at by local authorities. Losing Dario, Saslaya wanders into a town and perhaps an unhappy future—one that may echo what had happened to her mother.

This simple story is enhanced by poetic, even at times vaguely surrealist images, such as the two men struggling to move a wooden table who keep crossing the children’s path. With so little narrative to follow, we are encouraged to focus on the hardships and occasional pleasures of a culture which seldom figures in world cinema.

I referred to the two Mexican films that I described in our first Vancouver report as melodramas. Add another  to the list with Francisco Franco’s Burn the Bridges. Two teenagers care for their dying mother in a setting that seems to attract many Latin American filmmakers: a large, decaying mansion. The sister refuses to leave the house, determined to build an isolated world for herself and her brother, to whom she feels an incestuous attraction. He, however, wants nothing more to escape, especially when a tough new kid at school awakens his dawning homosexuality. The action seems a bit overblown at times; I wasn’t always sure whether apparent humor was deliberate or not. But the film and its settings are visually compelling, especially a scene in which the brother and his new friend sneak into a forbidden part of their Catholic school, passing a series of large religious paintings and finally emerging on the roof.

to the list with Francisco Franco’s Burn the Bridges. Two teenagers care for their dying mother in a setting that seems to attract many Latin American filmmakers: a large, decaying mansion. The sister refuses to leave the house, determined to build an isolated world for herself and her brother, to whom she feels an incestuous attraction. He, however, wants nothing more to escape, especially when a tough new kid at school awakens his dawning homosexuality. The action seems a bit overblown at times; I wasn’t always sure whether apparent humor was deliberate or not. But the film and its settings are visually compelling, especially a scene in which the brother and his new friend sneak into a forbidden part of their Catholic school, passing a series of large religious paintings and finally emerging on the roof.

O’Horten is a Norwegian film from Bent Hamer, who has emerged as a film festival favorite with his  previous Kitchen Stories (2003) and Factotum (2005). It’s a character study of a fastidious train engineer striving to cope with retirement; the film plays out in an episodic series of encounters that eventually lead to Horten’s acceptance of his new life. The comedy of eccentricity proceeds in leisurely, continually entertaining scenes. Apart from its mainly quiet tone and somewhat slow pace, it presents no art-cinema challenges to the audience. Norway has chosen it as its candidate for this year’s foreign-language Oscar, and Sony Classic Pictures has announced that it will release the film in the U.S. in early 2009.

previous Kitchen Stories (2003) and Factotum (2005). It’s a character study of a fastidious train engineer striving to cope with retirement; the film plays out in an episodic series of encounters that eventually lead to Horten’s acceptance of his new life. The comedy of eccentricity proceeds in leisurely, continually entertaining scenes. Apart from its mainly quiet tone and somewhat slow pace, it presents no art-cinema challenges to the audience. Norway has chosen it as its candidate for this year’s foreign-language Oscar, and Sony Classic Pictures has announced that it will release the film in the U.S. in early 2009.

Many critics have treated Terence Davies’ Of Time and the City as if it were a sort of elegiac cinematic salute to his native city of Liverpool. Despite the fact that, following the undeserved commercial failure of his excellent adaptation of The House of Mirth (2000), Davies has not made any films, he clearly retains his popularity among aficionados. In fact, however, there is plenty of criticism interspersed with the new film’s lyrical passages. Davies deplores what has become of Liverpool since his childhood there and doesn’t hesitate to assess blame, and he includes harsh comments on religion and on British royalty. He has said that he modeled his documentary on those of Humphrey Jennings, and in particular Listen to Britain (1942), though Jennings’ films had none of the bitterness on display here. Given, however, that Davies was bullied in his school, grew up gay in a more intolerant era, and has had a stunted filmmaking career, such bitterness is hardly surprising.

During Davies’s youth, brick row-houses encouraged communities among the working-class families  necessary to Liverpool’s industries. Using moving and still footage from the era set to classical music, the director manages to create a poignant sense of the grim conditions these people endured. Modern footage shows these old row-houses in ruins—yet shows the council apartment blocks that replaced them to be in almost equally ramshackle shape. Davies contrasts these with some of the few remaining glorious buildings of Liverpool, mainly columned government spaces through which he cranes his camera. He also filmed candid footage of children, perhaps hinting at the one hope for the future, perhaps displaying those whose youthful memories of Liverpool are now being formed in a far less attractive city.

necessary to Liverpool’s industries. Using moving and still footage from the era set to classical music, the director manages to create a poignant sense of the grim conditions these people endured. Modern footage shows these old row-houses in ruins—yet shows the council apartment blocks that replaced them to be in almost equally ramshackle shape. Davies contrasts these with some of the few remaining glorious buildings of Liverpool, mainly columned government spaces through which he cranes his camera. He also filmed candid footage of children, perhaps hinting at the one hope for the future, perhaps displaying those whose youthful memories of Liverpool are now being formed in a far less attractive city.

Of Time and the City marks a welcome comeback, one which I hope will lead to more films by Davies.

DB here:

A miscellany

The Dragons and Tigers programs continued to bring forth very impressive items. Jia Zhang-ke’s 24 City offered a meditation on newly industrializing China, in the vein of last year’s Useless. Aditya Assarat’s Wonderful Town was a prototypical “art movie” that handled a doomed love affair with sensitivity and suspense.

Especially engaging was the new offering from Brillante Mendoza, whose Slingshot I admired at Vancouver last year. In Serbis (“Service”), the Family film theatre lives up to its name only with respect to its management. For here, in the sweltering Philippines town of Angeles, the Pineda family screens porn. The movies attract mostly gay men, who service one another in the auditorium, the toilets, and the stairways. While the matriarch Nanay Flor fights a legal battle, she runs the lives of her employees and kinfolk in a milieu teetering on the edge of confusion. The Pinedas live in the theatre, so that the youngest boy must thread his way to school through a maze of transvestite hookers.

Mendoza confines the action almost entirely to the movie house. That premise recalls Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye Dragon Inn, but Serbis has none of that film’s nostalgia for classic cinema. Here movie exhibition is an extension of the sex trade, exuberant in its tawdriness, steeped in heat and sweat, prey to randy projectionists and stray goats. Almodovar might make something more elegant out of the situation, but Mendoza’s careening camera yanks us from vignette to vignette, from the complaints of the operatic Nanay Flor to her loafing husband to the lusty projectionist with a boil on his buttock. Crowded with vitality, the film can spare its last moments for a burst of reaction shots that imply a whole new layer of comic-melodramatic turpitude.

In other strands of the festival, I enjoyed Nik Sheehan’s lively documentary FlicKeR, which tells the tale of Brion Gyson, friend to the Beats and especially Burroughs. But the real star is Gyson’s Dream Machine. A turntable that spins a slotted cylinder around a lightbulb, the gadget—reminiscent of the Zootrope and other precinematic toys—proved mesmerizing to artists and countercultural fellow travelers. Marianne Faithful, Iggy Pop, and other worthies attest to the hypnotic power of the Machine, which triggered a drug-free high. Sheehan fills in a patch of important cultural history and may inspire others to tickle their alpha waves with a homemade Dreamer.

Almost exactly halfway through Steve McQueen’s Hunger lies a long dialogue scene in which IRA prisoner Bobby Sands explains to a priest why he has to launch a hunger strike. Over cigarettes the two men debate the cost of pushing tactics to this extreme. Running nearly twenty minutes and relying almost entirely on a protracted profile shot, it’s the first extended conversation in what is largely a film of bits of behavior and glimpses of a harrowing place.

Hunger starts by showing the morning routine of a guard at Maze Prison. He washes up. Stiff along a wall, he smokes a cigarette. He painstakingly folds up the tinfoil that wraps his lunch. McQueen’s oblique approach to the subject is maintained when we see a new prisoner brought in. Through him we learn of the cell walls whorled with excrement, the unannounced beatings, and the charade of providing tidy clothes for the prisoners to wear on visitors’ day.

Hunger starts by showing the morning routine of a guard at Maze Prison. He washes up. Stiff along a wall, he smokes a cigarette. He painstakingly folds up the tinfoil that wraps his lunch. McQueen’s oblique approach to the subject is maintained when we see a new prisoner brought in. Through him we learn of the cell walls whorled with excrement, the unannounced beatings, and the charade of providing tidy clothes for the prisoners to wear on visitors’ day.

Comparisons with Bresson’s A Man Escaped are inevitable. McQueen is less rigorous and original pictorially, assembling shots based on current image schemas (planimetric framings, selective focus, extreme close-ups, artily off-center compositions, handheld shots for scenes of violence). And he can underscore points a bit too much, as with the repeated shots of the guard’s scabbed knuckles. Still, compared with Schnabel’s conventionally daring Diving Bell and the Butterfly, the film is willing to be unusually hard on us. Through his nameless prisoners, McQueen treats both brutality and fortitude matter-of-factly. His experience with gallery-installation video seems to have encouraged him to let sheer duration do its job. A patient shot stationed at the end of the corridor waits while a guard, proceeding steadily toward us, clears puddles of urine with a push-broom.

Once Sands passes through his revolutionary catechism, the stakes are clear. The rest of the film returns to the dry, nearly dialogue-free atmosphere of the opening as Sands’ strike ravages his body. The objectivity of the opening yields to Sands’ hallucinatory recollections of his childhood as a long-distance runner. Some may see these images, including birds in flight, as clichéd sympathy-getters, but McQueen’s handling is pretty unsensational. Hunger’s quasi-geometrical structure, the sidelong introduction of horrific material, and the almost clinical treatment of Sands’ deterioration invite us to feel, but they also urge us to think about the price of sacrifice to a cause.

Genre crossovers

Some people consider the “festival movie” a genre in itself–the somber psychological drama with little external action, shot at a slow pace. The stereotype is all too often accurate, but festivals play genre pictures too. Usually these are impure genre pictures, more self-consciously artful or ambitious than multiplex crowd-pleasers. Vancouver had its share of such crossover items.

Hansel and Gretel, a South Korean horror film, played with a classic premise: the happenstance that brings someone from the normal world into a peculiar, isolated household. In this case, a superficial young man lost in a forest stumbles into the House of Happy Children. Here three kids seem to rule their passive, saccharine parents. The situation recalls Joe Dante’s episode of the Twilight Zone film, and during the Q & A director Yim Phil-sung acknowledged the influence of that movie, as well as Night of the Hunter. Brisk, fast-paced, and boasting remarkable sets—dazzlingly lit, jammed with toys and sweets, and ineradicably sinister—Hansel and Gretel could earn cult following in America. Rob Nelson has more here.

Artier, and scarier, was Let the Right One In, a Swedish film by Tomas Alfredson. Adapting Chekhov’s precept that the gun on the mantle in Act 1 has to go off in Act 3, the film begins with the boy Oskar playing with a knife at his window. Later we’ll learn that his stabbing is a fantasy rehearsal for dealing with the bullies who torment him at school. He meets Eli, a girl who comes out only at night, and their adolescent friendship/ love affair on the jungle gym of a housing block is intertwined with a series of vampire attacks on a small town. The tautly constructed script develops in gory directions that I found both unexpected and inevitable. The wintry widescreen cinematography is handsome and precise, and may well look better on 35mm than on the somewhat contrasty digital version available for the festival. It will have a limited opening in the U. S. later this month.

After School, by Uchida Kenji, is an agreeable thriller—somewhat overbusy and implausible in its plotting, but offered with a modesty and assurance that make it worth a watch. The basic situation, of a missing salaryman who may be having an affair, gains suspense by initially restricting our viewpoint to a shabby private detective. Uchida has fun with one of those misleading openings so common nowadays: you think you understand it from the get-go, but when it’s replayed it takes on a new meaning (and explains the title). The final shot, from a surveillance camera trained on an elevator, is a nicely oblique reminder of what seemed at the time a throwaway moment.

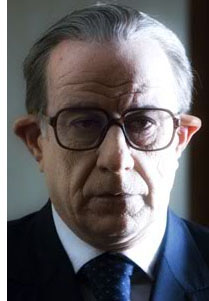

Variety characterizes Il Divo’s genre as “Biopic, Foreign, Political, Drama,” which covers all the bases. Giulio Andreotti, long-time Italian politico, is the subject of the movie, described by an ironic friend as “one-half of the current Italian film renaissance.” The movie surveys Andreotti’s career after the Red Brigades’ murder of Aldo Moro, which triggered a wave of investigations, tribunals, and assassinations, and it concentrates on years after 1995, when Andreotti was accused of links to the Mafia. The first half-hour feels like a single montage sequence, with murders and huddled meetings whisked past us thanks to rapid cutting, swooping camera movements, and pulsating music. (The eclectic score ranges from Sibelius to Gammelpop.) Imagine the sinuous opening of Magnolia, with machine guns.

Variety characterizes Il Divo’s genre as “Biopic, Foreign, Political, Drama,” which covers all the bases. Giulio Andreotti, long-time Italian politico, is the subject of the movie, described by an ironic friend as “one-half of the current Italian film renaissance.” The movie surveys Andreotti’s career after the Red Brigades’ murder of Aldo Moro, which triggered a wave of investigations, tribunals, and assassinations, and it concentrates on years after 1995, when Andreotti was accused of links to the Mafia. The first half-hour feels like a single montage sequence, with murders and huddled meetings whisked past us thanks to rapid cutting, swooping camera movements, and pulsating music. (The eclectic score ranges from Sibelius to Gammelpop.) Imagine the sinuous opening of Magnolia, with machine guns.

When director Paolo Sorrentino settles down to to presenting straightforward scenes, his florid technique persists (he never met a crane shot he didn’t like), but the action is dominated by Toni Servillo’s lead performance, which is weirdly showoffish in its own way. Servillo’s Andreotti is a rigid, buttoned-up fussbudget, an impassive mole of a man; only his epigrams (“Trees need manure to grow”) suggest a mind inside. The maniacally contained performance is as stylized as a turn by Lon Chaney, and as hard to keep your eyes off. Then again, given the glimpses of Andreotti in this report on the Italian response to Il Divo, the portrayal seems only a little exaggerated.

Of course there can be a straightforward genre picture here and there at the festival. The most disappointing instance I saw was The Girl at the Lake, an Italian whodunit that is only a notch or so above a TV movie. More entertaining was Welcome to the Sticks, the fish-out-of-water comedy that has become the top-grossing French film of recent years. A postal supervisor is assigned to a remote village where, he’s convinced, the hicks and the freezing cold will make him miserable. Instead he finds warm-hearted people and plenty of fun. The problem is to keep his wife from finding out how much he’s enjoying himself.

The item is hammered and planed to the Hollywood template. Plot lines: love affairs, both primary and secondary, complicated by work. Structure: four parts, with a neat epilogue that wraps everything up. Motifs: traffic cops, carillon bells, and food, often treated as running gags. Style: overall, less cutting than we might find in Hollywood (8.7 seconds average shot length), but still huge close-ups for extended passages of dialogue. In all, Wecome to the Sticks is sitcom fare that provided, I have to admit, a nice break from a lot of misery on display in the more orthodox festival offerings.

Turning Japanese

In our first communiqué, I talked about films by Kitano and Wakamatsu. I want to add comments on two more Japanese movies I saw, both of exceptional quality.

In All Around Us, Hashigushi Ryosuke (Like Grains of Sand, 1995) tells the story of a fraught marriage. The happy-go-lucky Kanao settles into a job as a courtroom artist for TV news, while Shozo, who works in publishing, is a believer in strict rules for their relationship. Their efforts to have a child end unhappily, and Shozo finds her life unraveling. Domestic troubles, amplified by tumult in Shozo’s extended family, play out while every day Kanao covers soul-destroying criminal cases, many involving assaults on children.

The mix of tender sentiments and extreme violence (offscreen, but evoked through chilling testimony) give the film a typically Japanese flavor. Hashigushi filters much of the courtroom horrors through Kanao’s point of view, so that while a defendant berates himself for not killing more people, Kanao watches a mother, and the close-up of her bandaged wrist concentrates all her grief.