Archive for the 'National cinemas: UK' Category

An evening with Mr. Smith

Dad’s Stick (John Smith, 2012).

DB here, from London:

Last week we held another annual meeting of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. I think it’s safe to say that a hell of a time was had by all. I hope to file a report on some of what was said in nearly 100 presentations across 3 ½ days. For now I want just to note a conference highlight that deserves special notice.

English filmmaker John Smith has been working since the mid-1970s, originally in 16mm and now in HD video. On Thursday 18 June, several lucky participants got a very substantial sampling of his career’s achievement in an evening retrospective.

English filmmaker John Smith has been working since the mid-1970s, originally in 16mm and now in HD video. On Thursday 18 June, several lucky participants got a very substantial sampling of his career’s achievement in an evening retrospective.

In their visual wit and their emphasis on perceptual shifts, Smith’s films owe something to the international Structural Film trend, but they stand out by their wit and their almost classical beauty. I saw affinities with Hollis Frampton, especially in Associations (1975), in which a test of word-associations slips hilariously out of control. But Smith seems to lack Frampton’s interest in poeticizing scientific and philosophical concepts. The work sampled in our session was characterized by sensuous appeals: precise framing, saturated color, image-sound counterpoint, and richly detailed landscapes. The conceptual element entered as teasing jokes or half-formed narratives.

I had seen three or four before. Hackney Marshes–November 4, 1977 wasn’t in the program, but Kristin and I referred to it in Film History: An Introduction, because of its brash editing patterns. More famous, I suppose, and screened on Thursday, was The Black Tower (1985-87, below), with its oppressive rectangle looming over a striking variety of locales. The film keeps cutting among widely different vistas and neighborhoods, each with the tower visible in middle distance. The associations pile up: state surveillance, a prehistoric monolith, a dark temple, or an alien spacecraft. It was a pleasure to see again.

Altogether different is another of Smith’s most famous works, The Girl Chewing Gum (1976). A busy street is rendered strange by the soundtrack, in which a commentary seems to be directing the whole ensemble of passersby and traffic. Quite soon the voice-over turns into something quite odd. I find a whiff of Monty Python in this charming lesson in image/sound interference. (You can watch it on Vimeo here.)

One of the most striking selections was Blight (1994-96). The demolition of a nearby building becomes, through Smith’s maniacally locked-down camera, a study in abstract composition and eerie movement. My stills can’t suggest the way in which apparently fixed timbers and bricks suddenly shift or fall, moved by no visible hand. The music by Jocelyn Pook further “defamiliarizes” imagery of collapsing walls and exposed wiring. And the tattered man above seems to be watching the whole proceedings.

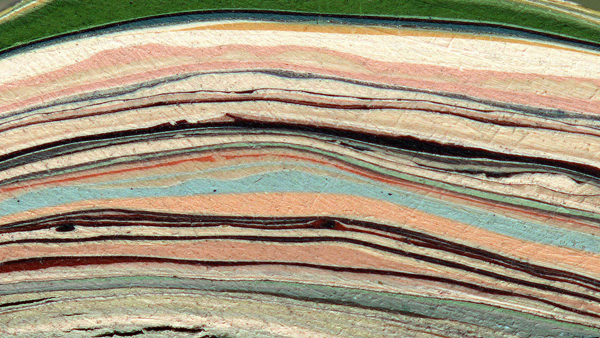

The program concluded with recent work. Flag Mountain (2010, above) elicited much comment. Fixed stop-motion telephoto shots of a mountain in Nicosia become almost hallucinatory in vibrant HD video and rapid day/night alternations. Dad’s Stick (2012, above) is a lovely tribute to Smith’s father, but it’s also a witty game of form. What seems at first to be a voluptuous abstract painting turns out to be something more mundane, but now mysterious in its accidental beauty. As a bonus, you get a good-natured teasing of art critics’ jargon. Part of Dad’s Stick is here.)

John proved a delightful and modest commenter on his work. He points out that the fixity of each image allows him to treat them as discrete items, like letters of an alphabet, so that the cutting has a crisp force. He’s come to like HD video, but yearns to “get out the old Bolex and shoot one last film.” He declines all the standard labels—avant-gardist, experimental filmmaker, maker of “artist’s films.” He thinks that his films can be appreciated by anybody who’s open-minded, and I think we all agreed. Quiet yet powerful, John Smith’s work seems to me to attest to the continuing relevance of artisanal filmmaking.

You can visit John’s website here. A large selection of his work is available on the three-DVD set John Smith, available from Lux here. The discs aren’t region-coded. Every university should have this set, as well as the Cinema 16 collection, British Short Films, which includes work by John and his contemporaries.

Thanks to Tim Smith, Murray Smith, and John Smith (no relation, none at all) for arranging this wonderful evening.

The Black Tower (John Smith, 1985-1987).

Hitchcock again: 3.9 steps to s-u-s-p-e-n-s-e

Henry Edwards; Alfred Hitchcock.

DB here:

My previous entry reminded you that Hitchcock was notorious for distinguishing between suspense and surprise. To achieve suspense, he maintained, the audience has to be aware of more than the characters know. Surprise arises when we know as much as the characters, or less. Hitchcock also declared his general preference for suspense, since it provides prolonged tension while surprise produces merely a momentary buzz. The mystery was: Where do this distinction and this preference come from? Are they original with Sir Alfred, or can we find precedents?

The story so far:

Step 1: The distinction itself goes back at least to the eighteenth century and the playwright/theorist Gotthold Ephriam Lessing. Lessing likewise expressed his preference for suspense because it demanded superior craftsmanship and yielded stronger effects on the audience.

Step 2: The distinction and the preference for suspense was still circulating in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century commentaries on theatre. My entry also mentioned a 1922 screen playwriting manual by Howard Dimick that took the same stance.

So we’ve located general conditions for influence. By the early 1920s, the suspense/surprise doublet was still circulating in the worlds of film and theatre, when Hitchcock was starting his career. But influence, like its source-word influenza, requires close contact. It would be good to find the secret agent who might have passed along the idea to the young director.

Step 3: My P.S. to the entry ropes in one candidate: Eliot Stannard. Richard Allen proposed him as a possibility, and Ian Macdonald supplied information that strengthened the suspicion. Stannard was a busy screenwriter of the period, who worked closely with Hitchcock on nearly all his silent pictures, and he even wrote a manual on screenwriting. Although he apparently didn’t talk about suspense and surprise in print, he would have known William Archer and other drama theorists who did. Stannard could well have initiated Hitchcock into the idea.

Step 3.9: But do we have the wrong man? After I posted my P. S., another foreign correspondent weighed in. Charles Barr writes:

A key figure here is Henry Edwards. Director in British cinema 1916-1937, and actor for much longer. His (lost) feature film Lily of the Alley in 1923 made a big point of avoiding intertitles. Whether or not he saw it, Hitchcock must have at least been aware of it, even though later he always said that The Last Laugh was the first such film. And already in 1920 Edwards had spelled out the surprise/suspense distinction: see attachment from the trade paper The Bioscope.

Edwards was indeed a major figure, as producer, actor, and director during the 1910s and 1920s. At the British Film Institute site, Geoff Brown and Briony Dixon provide a lively account of his career. He was clearly in a position to influence younger filmmakers.

The 1920 Bioscope article, cited in the Brown/Dixon overview and supplied to Charles by Ph.D. student Michaela Mikalauski, is a revelation. Edwards writes:

We must so construct our story that suspense is created–suspense is the dread that something may happen, and it is on this that we must build our story.

We must so construct it, that by careful preparation impeding difficulties or dangers are looming up before our characters. We must show the audience these dangers, and keep our characters ignorant of them until the proper moment; and it is the nearing of the danger to the blissfully ignorant character, making us long to cry out and warn him, that give suspense.

Tellingly, Edwards uses an example of an explosion. Imagine that our hero, wandering in the wilderness, has taken shelter in a shack. He sits on a box and lights a cigarette. While he has a leisurely smoke, his match has ignited some dry rubbish by the box. He rises and leaves the shed, just as the box is blown to pieces. Now we realize that it contained dynamite.

Here is a case in which there is expectancy, and never for a moment suspense, because the audience does not know of the impending danger to the character.

Now let us defy the critics who clamour for “surprise” in film construction, and tell the incident in the language of the screen.

Edwards goes on to imagine that we’ve seen quarrymen leave the box of dynamite behind. When the hero ambles in and settles down on the box for a smoke, we’re already apprehensive. Now every gesture he makes prolongs the tension, and we watch anxiously as the discarded match ignites scraps beside the box.

It becomes a question as to which will take the longer, the hero to recover his strength and go, or the box of dynamite to explode. Here is sheer suspense, and when there hero has gone it is no jar to the audience but rather a pleasurable expectancy to see the box explode harmlessly in the air.

After supplying another, more psychological example, Edwards concludes his piece: “The letters of the film alphabet are s-u-s-p-e-n-s-e.”

This article–published the very year that a young and innocent Hitchcock began work for Famous Players-Lasky in Islington–shows that the terms in which Hitchcock understood the suspense/ surprise distinction were already clearly articulated in English film culture. Even the bomb situation that Hitchcock would summon up for Truffaut is there in Edwards’ piece. But of course this information doesn’t sabotage the standing of Stannard, who may have read the Bioscope article and transmitted its lesson to Hitchcock in later years.

I confess I had thought I was done with the thing, but the last few days have brought a small frenzy of emails, and I’m feeling a bit of vertigo. Still, there seems not a shadow of a doubt that Hitchcock was maintaining his faith in a storytelling device that goes back quite far and still had a grip on the formative years of British and American cinema.

Thanks very much to Charles Barr for the information and for sending me the Edwards article. It was published as “The Language of Action,” Bioscope (1 July 1920), supplement p. iv. Thanks also to Michaela Mikalauski for locating the piece, and to Antti Alanen for forwarding some crucial email addresses.

Charles’ revised edition of his Vertigo monograph includes some further comments on the suspense/surprise distinction as it relates to that film. Charles is also completing a new book, with Alain Kerzoncuf, called Hitchcock: Lost and Found. It surveys the little-known films from all periods of Hitchcock’s career. “It devotes some 15,000 words to ‘Before the Pleasure Garden,’ discussing the 21 films Hitchcock was involved with (surviving in whole or part or not at all) and also a bit on the wider context, which is where Edwards comes in. This is all about to go to the publisher (Kentucky) and if all goes well will be out by the end of 2014.”

I’m grateful to all. The little adventure, which I suspect is not quite over, has been rich and strange.

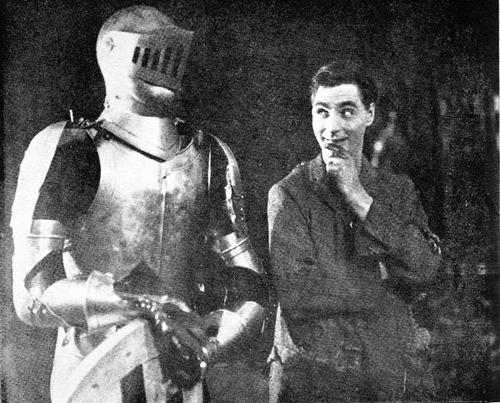

Broken Threads (1918), produced and directed by Henry Edwards, who also starred.

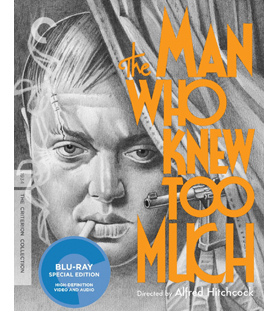

Sir Alfred simply must have his set pieces: THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH (1934)

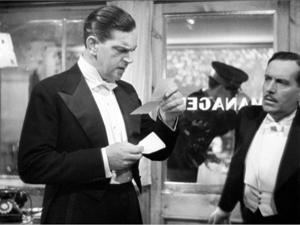

The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934).

DB here:

Hitchcock made six remarkable thrillers from 1934 through 1938, and I have long believed that the first one was the best. I think very well of Sabotage, and both The Lady Vanishes and The 39 Steps are strong contenders. But for me, The Man Who Knew Too Much has got damn near everything going for it.

I came to it a little late. It wasn’t the first Hitchcock I wrote about; that was Notorious, in a 1969 piece that nakedly reveals the limitations of a college senior’s knowledge. Nor was it the first Hitchcock I saw; that was Vertigo, when I was about ten. Inauspiciously for me, when Vertigo was revived for national television broadcast in 1972, I was flying to a job interview in Madison, Wisconsin.

I got that job, though, and soon The Man Who Knew Too Much became very important for me. Seeing it at a film society screening, I was bowled over. Then I discovered that it was available for purchase in a cheap 16mm print. I bought a print and began teaching the film as a model of narrative construction. It worked its way into the first edition of Film Art, in 1979 and hung around there for several editions.

That sample analysis has been available as a pdf on our site, but check it out at the Criterion site, where it’s enhanced with nice frame enlargements and a major extract. The essay makes my case for the movie as an extremely well-constructed piece in the classical storytelling tradition.

So I was the ideal consumer for a spruced-up DVD/ Blu-ray release, and as usual Criterion doesn’t disappoint. It’s a handsome version, with some fine supplements. We get two rare interviews with Sir Alfred from CBS’s arts program Camera Three (featuring Pia Lindstrom and William K. Everson) and a perceptive discussion with Guillermo del Toro, who makes a vigorous case for the film. So does Philip Kemp in his commentary, which is strong on production background. Kemp offers valuable information on script versions and on Hitchcock’s niche in the English industry. The accompanying booklet includes a lively appreciation by The Self-Styled Siren, aka Farran Smith Nehme.

So I was the ideal consumer for a spruced-up DVD/ Blu-ray release, and as usual Criterion doesn’t disappoint. It’s a handsome version, with some fine supplements. We get two rare interviews with Sir Alfred from CBS’s arts program Camera Three (featuring Pia Lindstrom and William K. Everson) and a perceptive discussion with Guillermo del Toro, who makes a vigorous case for the film. So does Philip Kemp in his commentary, which is strong on production background. Kemp offers valuable information on script versions and on Hitchcock’s niche in the English industry. The accompanying booklet includes a lively appreciation by The Self-Styled Siren, aka Farran Smith Nehme.

Interest in Hitchcock seems to be the one constant in the whirligig of tastes in film culture. He is a mainstay of home video and cable television; apparently the films can be re-released in perpetuity. Professors love to teach his films. The techniques are obvious and vivid, and the films offer a manageable complexity that encourages interpretation. Class, gender, power, the law—whatever your favorite themes, they’re all on the surface, yet enticingly ambivalent. Not to mention how much fun these movies are to watch. I’ve always enjoyed introducing “lesser Hitchcock” like Stage Fright and Dial M for Murder and then watching the audience fall under their spell.

Critics navigate by Hitchcock as a fixed pole star. Reviewers compare every new thriller to the classics of The Master of Suspense. Just look at what people write about Soderbergh’s Side Effects. And for those who promoted the auteur approach to Hollywood cinema, Hitchcock was a beachhead. Who could doubt that this man turned out personal projects within the impersonal machine known as Hollywood? And if he could do it, why not Ford, Hawks, Sternberg, Ray, and all the rest? Hitchcock nudged skeptics down the slippery slope toward auteurism.

Even if Hitchcock isn’t to your taste, you can’t avoid his influence. That became obvious around the 1970s, when directors began borrowing from him more or less overtly: Spielberg’s Vertigo track-and-zoom in Jaws (now itself a convention), De Palma’s homages/pastiches, Polanski’s use of point-of-view in Repulsion and Rosemary’s Baby, the endless Psycho sequels and the van Sant remake, and the rest. But Hitch was no less influential in his own day; I’d argue that filmmakers of the 1940s had to raise their game if they wanted to meet the challenge of Rebecca, Foreign Correspondent, Suspicion, Shadow of a Doubt, Spellbound, and Notorious. Billy Wilder told a reporter that Double Indemnity was his effort to “out-Hitch Hitch.”

What was so special? Obviously, the throwaway humor—sometimes airy, sometimes slapstick, sometimes sardonic. And obviously a gift for switching situations around, playing them against cliché, setting us up for a jolt. But I think there’s something else afoot. Part of the Master’s repute rests on virtuosity of film technique. Hitchcock makes movie movies, even when, like Rope or Dial M, they seem “theatrical.” And this movieness is best seen, I think, by considering a term that always comes up with Lord Alfred: the set piece.

Maintaining a tradition

Hitchcock held onto the flamboyant expressive devices of silent and early sound cinema far longer than any other director. For decades he kept alive techniques that many directors thought were old hat: abrupt cuts to details of gestures and objects; blurry point-of-view images to suggest distraught or befuddled states of mind (as above); very brief insert shots to accentuate violence. Compare Battleship Potemkin with Foreign Correspondent’s assassination scene.

Hitchcock built entire films around classic silent techniques. The Kuleshov effect governs Rear Window; the German “entfesselte” or “unchained” camera dominates Rope and Under Capricorn. Rope and Dial M revive the aesthetics of the German kammerspielfilm, or “chamber play.” The Germanic look was alive and well in the spiderweb shadow-work of Suspicion, while both French Impressionism and German Expressionism inform the dream sequences of Spellbound and Vertigo. He also preserved the “creative use of sound” that was the hallmark of directors like Clair and Milestone. While others had pretty much given up the expressionistic use of music and effects, Hitchcock was always ready to draw on them. The hallucinatory Merry Widow Waltz haunts Shadow of a Doubt, while Hitchcock’s penchant for giving us two pieces of information simultaneously, one in the image and another on the soundtrack, let him design scenes visually and push a lot of dialogue offscreen.

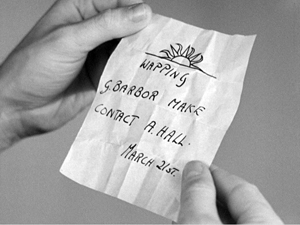

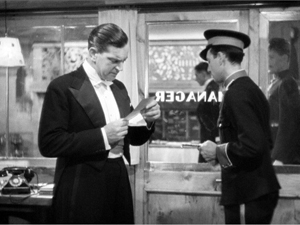

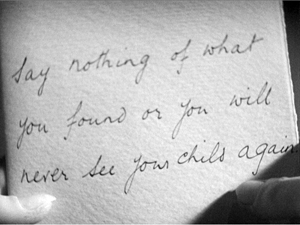

This flexibility of technique modulates from scene to scene. In The Man Who Knew Too Much, note-reading is presented in three ways, in rapid succession. First, Bob finds Louis’ note in the hairbrush.

Soon Bob gets a message from the front desk. What does it say? Hitchcock hides that by, for once, not supplying subjective point of view.

Only when the note is passed to Jill do we get to see it, but with a twist. Nobody but Hitchcock would add an extra shot that cuts to the note in her hand without revealing what it says.

That extra shot is what Eisenstein called a primer; as with dynamite, you need a little charge to trigger the blast.

We often forget that classic silent directors used their pictorial techniques for suspense. Lang’s Mabuse films and Spione furnish plenty of instances, but so do the Soviet montage films. The scene in which the police wait for the worker to return to his wife in The End of St. Petersburg now looks like pure Hitchcock, and of course the Odessa Steps sequence was the Psycho shower of its day. So it isn’t surprising that Hitchcock would turn his silent-film virtuosity toward creating scenes of high tension and threatened violence. Nor is it surprising that his skills would crystallize in “set pieces.”

Everybody talks about Hitchcock’s fondness for set pieces. It’s part of his brand. We have the Statue of Liberty climax in Saboteur, the milk carried up the staircase in Suspicion, the milk-and-razor scene and the final suicide in Spellbound, the spectacular rescue of Alicia at the end of Notorious, and the efforts of Bruno to retrieve the lighter in Strangers on a Train.

But, come to think of it, what makes something a set piece?

Game, set piece, match

Foreign Correspondent (1940).

As commonly understood in the arts, a set piece is a fairly self-contained portion of a larger work. It has a distinct beginning and end, and it’s understandable and impressive if extracted from its original. It’s designed to be a bravura display of concentrated virtuosity. In music, an example would be an operatic aria like the Queen of the Night’s in The Magic Flute: it is so flashy and complete in itself that it can enjoyed on its own, in a concert setting.

Two early uses of the term shed light on its implications. In stage parlance, a “set piece” is an item of the set that can stand alone, like a gate or fake tree. In pyrotechnics, a “set piece” is a carefully patterned arrangement of fireworks; here again, it implies a display that dazzles the audience.

In the silent era, I’d suggest, the clearest exponent of set pieces is Eisenstein, who became known as “the master of the episode.” Many of his big scenes, like the Odessa Steps massacre, are developed at such length that they function as mini-films. But you can consider passages in Chaplin and Keaton as set pieces—the dance of the breadrolls in The Gold Rush perhaps, or the windstorm in Steambout Bill, Jr. The musical would seem to be a natural home of the set piece, with numbers standing out against more mundane scenes. In modern cinema, again under the aegis of Hitchcock: De Palma offers plenty, and perhaps the prize fights in Raging Bull constitute a string of them. Today the home of the set piece is the action picture; the chases and fights are the main attraction, and the genre challenges directors and crew to find new ways to intoxicate us.

The aesthetic of the set piece implies that some scenes function as filler while others get the whipped-up treatment. If that’s right, many great directors don’t favor mounting set pieces. Ozu, Mizoguchi, Dreyer, Hawks, and others present what we might call “through-composed” films. Just as Wagnerian opera and its successors minimized set pieces, these filmmakers create a surface texture that doesn’t create self-contained high points. (I grant you that the immolation of Herlofs Marthe in Dreyer’s Day of Wrath might count.)

Given the detachable quality of set pieces, it’s true that some of Hitchcock’s can seem implausible or gratuitous. How essential is Guy’s lighter to any plausible scheme of Bruno’s? If you want to kill Roger Thornhill, why send him to a crossroads in Midwest corn country? (A knife in the back on the Greyhound is more reliable.) It was this tendency to sacrifice story logic for stunning anthology bits that Raymond Chandler deplored:

The thing that amuses me about Hitchcock is the way he directs a film in his head before he knows what the story is. You find yourself trying to rationalize the shots he wants to make rather than the story. Every time you get set he jabs you off balance by wanting to do a love scene on top of the Jefferson Memorial or something like that.

Chandler has a point. How do you integrate a set piece into a whole movie? (I’ll make some suggestions shortly.) But first, give Hitch his due. For him, I think a set piece was a compact repository of inherently cinematic ideas carried to a limit within a sequence. A set piece is a challenge: How much can you squeeze out of a situation?

Go back to Foreign Correspondent. Setting an assassination in Amsterdam allowed Hitchcock to integrate the idea of a clue based on a waywardly turning windmill. So far, Chandler’s objection seems tenable: The windmill is just a gimmick. But once Hitchcock sets his hero exploring the lair, he can create a set piece that answers a question that no one ever thought to ask before: How do you eavesdrop in a windmill?

Johnny Jones has to evade the killers by crawling up alongside the giant gears, then down, then up again. At each step he barely escapes being spotted. When he seems safe, his topcoat gets snagged in the grinding gears, so he has to slip his arm out of it—just in time to avoid being crushed.

Yet once Jones is freed from the coat, it’s carried around the gearwork and might be spotted by the gang. And the old diplomat upstairs, mind hazed by drugs, is likely to reveal Jones’ presence. Hitchcock squeezes seven minutes of suspense out of all this, with a casual air that suggests: Of course, dear chap, any director worth his salary can see that a windmill harbors all kinds of excruciating menace. All in a day’s work, you know.

A whispered terror on the breeze

If anything is a set piece, the Albert Hall sequence in The Man Who Knew Too Much is. Philip Kemp’s commentary for the Criterion DVD considers it Hitch’s first, although aficionados would probably consider the “knife” sound montage of Blackmail at the very least a rough sketch for what would come. Lucky you: The entire Albert Hall sequence is excerpted on the Criterion site.

A set piece benefits from a simple premise. Here, Jill’s child is being held hostage, which keeps her from informing the police of what little she knows about the plot. We know that during the concert an assassin will try to shoot a diplomat.

You can imagine Chandler asking: Why plug Ropa during a concert, with all those witnesses? Why not when the target is on the sidewalk, shot from a rooftop for easy escape? You can hear that bland replying murmur: Raaaymond, it’s only a moovie…

So we have some conditions for a set piece: a compact piece of action limited in time and space. But there’s also a strong time marker. Ramon the assassin is to wait for a dramatic pause in the score; it’s followed by a shattering choral outburst that will muffle the pistol shot. We’ve been given a rehearsal of the passage in a gramophone record, but since we don’t hear the whole piece then, we can’t predict exactly when the chorus will hit its peak.

Hitchcock magnifies this uncertainty by letting the piece, Arthur Benjamin’s Storm Clouds Cantata, play out in its entirety. Its combination of lyrical and dramatic passages blend into a stream of music that coincides with the emotional action onscreen. I suspect that the piece, composed specifically for the film, glances at the most celebrated new choral piece of the era, William Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast (1931). It too has a charged dramatic pause followed by a tremendous choral blast: “Slain!” You can listen to it here, and you can hear some of the musical affinities at 27:11 and after.

So the self-contained quality of the sequence is enhanced by the unfolding soundtrack, as well as its “bookend” structure: Jill arrives at the Albert Hall/ Jill leaves. (Hitchcock was very fond of this coming-and-going bracketing; many scenes of The Birds are built out of this.) But to be a set piece we need virtuosity too, right?

As our Film Art essay indicates, Hitchcock structures the scene using nearly every technique in the silent-cinema playbook. We get dynamically accentuated compositions, crisp point-of-view editing, subjective vision (even blurring as Jill drifts into a panicky reverie), and suspenseful crosscutting back to the gang holding Bob and Betty prisoner. The techniques build to their own crescendo, with more and shorter shots of Jill, the orchestra players, and the curtain concealing Ramon. As the climax approaches, details of the players’ performance pass in a flash. As another layer, though, all these visual techniques are synchronized with the musical structure of the piece. Most obvious is the slow tracking shot back from Jill as the female soloist launches in:

There came a whispered terror on the breeze./ And the dark forest shook.

The text has always teased me, because in my early years of studying the film I couldn’t hear everything there. Now that the Storm Clouds Cantata has become a minor concert piece, we have a full version of the text. It’s the description of an especially ominous storm, one that drives birds away and makes trees tremble in fear. The only creature left, vulnerable to the gale, is a child:

Around whose head screaming/ The night-birds wheeled and shot away.

The orchestral and choral forces mount on the line that has always come through the sound mix:

All save the child—all save the child.

The line is ambiguous. Its literal sense is that all the creatures have fled the oncoming storm except the child (“all save the child”). But Hitchcock’s cutting and the film’s overall context leave it as an imperative: the child must be rescued. Thus the musical dynamics and the text stress, for us and presumably for Jill, that Betty’s safety depends on what she does.

Soon the cantata’s text finds another analog in the concert hall. The choir sings of the storm clouds finally breaking and “finding release.” That phrase, repeated with rising intensity, yields the dramatic pause and then the final outburst that is to cover Ramon’s pistol shot. But now we have to see this phrase as prophecy and comment: Jill’s scream during the pause is the release of her tightened anxiety. And of course the line slyly signals the release of the suspense built up through the whole sequence.

With Hitchcock, you always get more.

In all, the sequence becomes exactly what a set piece ought to be: compact, with sharp boundaries and a strongly profiled arc of interest, elaborated with a great variety of technical resources and a thrusting emotional impact. But is it too much of an independent sequence? One can imagine Chandler worrying that Hitch doesn’t care much about how to hook it up with everything else. Let’s see.

This scepter’d isle

There’s no doubt that a plot driven by set pieces can seem episodic, just a matter of pretty clothes clipped to a slender line. In action movies it’s a classic problem, which, say, Speed doesn’t fully solve but Die Hard does.

You can mask an episodic plot, though, through some stratagems. First, make your filler material charming. The Man Who Knew Too Much gives us comedy in the dentist office and in the Tabernacle, with Bob and Clive mumbling messages through hymnody. You can also whisk the audience from scene to scene so quickly that the viewer has to concentrate on local connections. This is one purpose of what I’ve called the hook, the transition that smoothly links the end of one scene with the beginning of the next. If you’ve got some plot holes, strengthen your hooks–especially those that hide your gaps.

The Man Who Knew Too Much has some nifty hooks. I especially like the way the fingers pointing to the bullet hole are followed by a shot of Ramon’s head: effect and cause neatly given by a straight cut. Then there’s the contrast of the fire in the fireplace dissolving to the skier pin, a sort of thermal hook. But probably the most memorable one is Betty’s line about Ramon’s brilliantined hair.

This hook is a motif as well, and recurring images or sounds like this can help knit together your movie. In Foreign Correspondent, we get hats and birds in various scenes. Here, as our Film Art essay indicates, teeth, the skier pin, sharpshooting, the cantata’s main theme, and other motifs weave through the overall structure of the film.

You can as well knit your big scenes together through certain narrative patterns, such as a trip or a search, both strategies that Hitchcock employs in many movies. In The Man Who Knew Too Much, Bob’s investigation of the gang follows the menu set out in Louis’ note: the sun emblem, Wapping, G. Barbour, and A. Hall. This serves as a sort of map for the middle act of the film. Once Bob has cracked the message, though, the film shifts into a new register. Jill, who has been waiting passively at home, takes over the role of protagonist. And her actions will fulfill another motif: that of interruption and distraction.

The film begins with Betty’s dog disrupting Louis’ ski jump. That’s an innocent accident, as is the moment when Jill nearly spoils Roman’s skeet shooting. But soon afterward Abbott’s chiming watch deliberately breaks Jill’s concentration, making her lose the shooting match. In effect the Albert Hall sequence offers payback: With her scream Jill not only disrupts the performance but spoils Ramon’s aim as Abbott had spoiled hers.

The Albert Hall sequence fits into the film in a less obvious way, one that plays along the thematic dualities that marble the movie. Throughout the film contrasts “Englishness” with “foreignness,” the latter split between allies (Louis, Ropa) and enemies. The Storm Cloud Cantata and what follows represent a sort of triumph of England over her adversaries.

At the St. Moritz resort, the Lawrence family is set off from Louis, their French friend, and two men: Abbott the German and Ramon the Latin. (He’s handily fudged; he has a Spanish name but calls the English “extraordinaire.” And his hair is greasy.) “Sworn enemies, eh?” Jill says half-humorously to Ramon before losing the skeet shoot. After Louis’ death Bob is at a loss in the hotel, unable to speak German or Italian, and distracted while Betty is kidnapped. The English aren’t at home in this world.

Once Bob and Jill have returned to London, they join the family friend Clive, a Wodehousian upper-class twit but gifted with loyalty and tenacity. Bob and Clive have learned from Gibson of the Foreign Office that the gang intends to assassinate the diplomat Ropa. They must tell what they know; the killing could prove as catastrophic as the assassination that triggered the war of 1914-1918. Yet Bob keeps mum. He might be enacting E. M. Forster’s dictum: “If I had to choose between betraying my friend and betraying my country, I hope I would have the guts to betray my country.”

The conflict between family love and civic duty is played out in the rest of the second act, when the men’s investigation takes them to a working-class neighborhood of Wapping. There, we learn that behind respectable English institutions—a dentist, eccentric religion—foreign elements lurk. Bob has solved Louis’ riddle, but at the cost of becoming another hostage. Bob and Betty re-meet, in a characteristically subdued stiff-upper-lip encounter that denies Abbott the tearful scene he expected. The dignity with which Bob conducts himself, asking about Betty’s dressing gown and her school grades while staring defiantly at the gang, leaves the others abashed.

Clive has escaped, though, and has managed to send Jill to the Albert Hall. That musical set piece initiates the film’s climax dramatically but also thematically. For one thing, Benjamin’s cantata reaffirms another bit of Englishness. A national choral tradition runs back to Purcell and Handel, was sharpened in Mendelssohn’s Elijah, and was revived in the early twentieth century by Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius and Vaughan Williams’ Sea Symphony. Hitchcock and screenwriter Charles Bennett could have used Bach or Beethoven, but the choice of this brooding, mildly modernistic piece reminiscent of Walton is a nice bit of propaganda for British musical culture of the interwar years.

More importantly, the concert sequence solves the film’s ideological problem: How to save the world without destroying your family? Jill’s impulsive scream doesn’t divulge what she and Bob know about the gang, but it does serve to derail the gang’s plan and save Ropa. And by leading the police to follow Ramon to the hideout, she in effect chooses to risk Betty and Bob for the capture of the gang. Here, perhaps, the sheer drive of the action muffles the significance of her choice; Chandler complains that Hitchcock tended to take refuge from plot problems in “wild chases.”

What follows, in the middle of some violence that remains shocking today, is a vigorous reassertion of Englishness. The vignettes during the siege display stalwart national virtues. A postman insists on making his rounds during the gunplay. An inspector swipes sweets and pauses for a cup of tea. The police reluctantly take up arms, only after several of their unarmed number are mowed down. Slipping into adjacent buildings, snipers move a piano while its fussy owner rescues his potted plant. And a cop who was slated to go off duty finds a warm mattress to die on. This unassuming valor, so different from Ramon’s petulant swagger and Abbott’s self-congratulatory sadism, will win out. The victory is announced by the pent-up crowd rushing jubilantly forward as the siege ends.

In any other movie the mother would have been huddling with the child and the man would grab a rifle to pick off his enemy on the roof. But making Jill the crack shot reasserts another quintessentially English image: the hunting, shooting, riding mistress of the estate. She gets her second chance to fire, bringing down Ramon when even the police sniper hesitates. It’s also a bit of guilty revenge for the death of Louis, whom Jill danced into the line of fire. Hitchcock, as usual, renders it elliptically: we see Jill grab the gun but not fire it. As she and Bob and Betty are reunited, the movie that began with the line, “Are you all right, sir?” ends with a mother reassuring her weeping daughter, “It’s all right.”

This, we might say, is how you integrate set pieces into your movie—narratively, stylistically, and thematically. Others would disagree with me, but nearly forty years of living with this film hasn’t made me change my mind. The Man Who Knew Too Much is Hitchcock’s first thoroughgoing masterpiece.

Thanks to Abbey Lustgarten, UW-Madison alum, for her excellent production job on the Criterion disc. Thanks also to Peter Becker and Casey Moore for coordinating the posting of our Film Art piece with this blog entry.

For more on Chandler and Hitchcock, see William Luhr, Raymond Chandler and Film (New York: Unger, 1982), 81-93. My quotation comes from Raymond Chandler Speaking, ed. by Dorothy Gardiner and Kathrine Sorley Walker (Books for Libraries Press, 1971), 132.

Hitchcock probably doesn’t deserve 100% of the credit for the Foreign Correspondent windmill scene; it was designed by the great William Cameron Menzies.

When I wrote the Film Art analysis back in the 1970s, Kristin hadn’t elaborated her ideas about how large-scale parts, or acts, can shape a film. Yet I think that the three parts that the analysis mentions constitute pretty well-articulated acts. The first part has as its turning point Bob’s realization that when Gibson traces Betty’s call, police will converge on Wapping and endanger her. So Bob and Clive set out to save her. That decision comes about twenty-six minutes into the movie. I’d mark the end of the second act with Abbott’s sending Ramon on his mission after playing the cantata recording; that comes at about fifty-three minutes into the film. At this point we know everything we need to know, so the premises can play out. The last act is shorter, as climaxes tend to be. The Albert Hall sequence and the final shootout and rescue take up the final twenty-three minutes, capped by a very brief epilogue of the reunited family. For more on act structure, see Kristin’s entry here, mine here, and my essay on action movies, as well as Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood and my The Way Hollywood Tells It.

A final note: Frank Vosper, who plays Ramon, was a well-known stage actor and playwright. His most famous play is Love from a Stranger (1936); the film version was released in 1937. Another successful Vosper play was the fantasy comedy Murder on the Second Floor (1929), in which a writer devises a play consisting of all the clichés of sensational mystery fiction. But the Vosper play that piques my curiosity most is his 1927 drama called—I’m not kidding—Spellbound.

See? With Hitchcock you always get more.

The Man Who Knew Too Much.

TINKER TAILOR once more: Tradecraft

DB here:

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy has to be counted a success ($64 million worldwide so far), and it may have brought new attention to John le Carré’s writing. The fact that some websites and Twitter feeds lured readers to my entry on the film (and thanks to all) suggests that people can enjoy a film even though major aspects of the plot escape them. Everybody loves a mystery, right?

Regular readers won’t be surprised to learn that I had originally written something longer about le Carré’s narrative strategies generally. Out of common human decency I cut the entry in half and focused on the film. But seeing the interest in what I’d posted, I thought that there might be enough hard-core readers who’d want to go down the rabbit hole again.

So one more post, which reflects a little more on the film, while arguing that le Carré’s development as a novelist offers a fascinating example of a writer trying out various methods of storytelling. Ideally, you should read this after reading my first post. The next three sections don’t spill any secrets, but if you want to avoid spoilers, stop at the section called “Burrowing.”

Going to ground

During the 1970s le Carré seems to me to have reinvented the dense, almost digressive plotting we associate with the nineteenth century British novel. A little narrative theory helps us understand his ongoing exploration of storytelling technique.

We’re used to thinking that a plot presents one or two major characters moving through the world. That movement yields adventures in the broadest sense: encounters with others, experiences that illuminate some aspect of life, conflicts both inner and outer. Our mental prototype of a plot, certainly in mainstream films, features a protagonist (or a couple) accompanied by lesser figures who become allies, helpers, lovers, rivals, and enemies.

Le Carré’s first novels accord with our prototype, with the addition of those old standbys Mystery And Intrigue. Call for the Dead (1961) and A Murder of Quality (1962) are mostly straightforward detective stories. Although George Smiley is a secret agent, he’s forced to investigate crimes. Accordingly, he goes from place to place, suspect to suspect, and hears out their explanations and alibis. With The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963), le Carré moves closer to an adventure plot, as we follow a protagonist in a linear succession of encounters. As is common in the genre, concealed information is sprung on us at various points, forcing us to recast what we thought we knew.

It takes a mind as odd as that of Viktor Shklovsky, the great literary theorist, to point out that we can think of any longish narrative as the intersection among many stories. He believed that as a form the novel developed out of assemblies of shorter tales. He pointed to The 1001 Arabian Nights and The Decameron as examples of this sort of compilation—long works built out of collected stories, enclosed within a bigger storytelling situation.

When the novel became a distinct genre, Shklovsky thought, it continued this tradition. In essence, each novel makes a long story out of several shorter stories. But unlike what happens in the compilation format, the stories become connected to one another. Character A figures not only in her own plot, but in Character B’s. This tends to hide the fact that separate stories are nestled within the overall architecture.

Besides connecting all the sub-stories, the ordinary novel makes some of them very minor. Our simpler prototype relies on suppressing or compressing all the other story lines except the one involving the protagonist. Our protagonist meets lots of people, but some are given no background, others a bit, and still others a fair amount, but nobody’s story can override the hero’s.

Shklovsky asks us to rethink our idea of the standard novel. It becomes not a straight-line path but a tangle of virtual tales that has been radically chopped down and ironed out. All the latent stories might be intriguing enough to sustain a plot in themselves, but for immediate purposes they must be subordinated to the fate of those creatures we call protagonists. In effect, Shklovsky suggests that every narrative can be thought of as an undernourished network narrative.

In a tale of mystery and detection of course, hidden backstories of some of the characters come to light gradually. But severe selectivity still reigns, because the backstories bear on the protagonist’s main goal: solving the mystery. When Smiley cracks a murder case or agent Leamas realizes that he has been deceived by his superiors, we understand other characters’ lives in a new way, but they don’t steal the stage from our hero.

Still, Shklovsky notes, some storytellers have realized that secondary characters can claim the spotlight as well. At the limit, they can furnish new narratives, as in Wicked and Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. Henry Jenkins’ idea of transmedia storytelling exemplifies this idea: the ally in one tale can become the hero of another, perhaps on another media platform. But of course nineteenth-century novelists aimed to do the same thing within a single tale, building elaborate plots that would give us an ample sense of how the lives of many characters converge through chance or common purpose. Our Mutual Friend, Pot-Bouille, and War and Peace try to accommodate a great many stories within their wide compass.

I think that with the novel Tinker, Tailor le Carré decided to try this option, to give the spy novel—typically the province of the teasing linear plot exemplified in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold—the sense of a panorama surveying many characters’ lives and perspectives and, still more broadly, the institutions that they serve.

Backchanneling

But there’s a problem here: How to expand your plot to do justice to many characters’ backstories and sidestories? Again Shklovsky provides useful hints, and le Carré tried many of the options he proposes.

Shklovsky suggests that stories can be integrated in two basic ways. One is through framing. You the writer set a self-contained tale, or several tales, inside a bigger one. This is exemplified by The Decameron and The Canterbury Tales, as in the films that Pasolini made from these classic works. We can see this option at work in a movie like Dead of Night (1945), in which guests at a country house party swap stories of the morbid and bizarre. Actually, le Carré tried this. The Secret Pilgrim (1990), is virtually a collection of short stories framed by an aged spy listening to Smiley lecture at MI6’s training school.

Another option is what Shklovsky calls “threading,” the principle that traces the consecutive adventures of a protagonist. This is the prototype I’ve already mentioned. But Shklovsky suggests that by keeping the protagonist thread you can still expand the framed tales. In Don Quixote, the adventures of the Knight and Sancho Panza hold their own interest, but they surround a string of embedded tales told by the people they meet. And sometimes those embedded tales are pretty long.

It seems to me that le Carré sought ways in which he could expand his embedded tales without losing the main thread. For example, his novel following The Spy…, The Looking Glass War (1965), splits the protagonist function up into three characters, their parallelism stressed by the section titles: “Taylor’s Run,” “Avery’s Run,” and “Leiser’s Run.” There is an overarching rhythm to the action, but we have three distinct protagonists. It’s as if the author is rehearsing, on a smaller scale, the shifting viewpoints that he will exploit in his longer fictions. The tripled protagonist also allows le Carré to present different standpoints on that center of spying operations MI 6, known as the Circus.

The following book, A Small Town in Germany (1968), is a return to a single protagonist and a straight detective plot, but now the mystery focuses on the bureaucracy behind espionage. Alan Turner, an embittered spy in the Leamas mold, is searching not only for a staff member missing from the British embassy in Bonn but also for some damaging files that have vanished. The drab routines of sorting, checking, and managing information become the object of scrutiny, and Her Majesty’s civil servants are prime suspects. Le Carré had found a way to put burrowing at the center of his plot.

After these efforts, in which Smiley barely appears, le Carré might well have felt ready to test his talents on a broader canvas. First came The Naïve and Sentimental Lover (1971), a satiric psychological novel about a businessman who becomes entranced by a novelist and his wife. The book, which runs over 400 pages, shows le Carré’s eagerness to stretch out. Just as important, I suspect, is its value as a laboratory for narrative experiments. Descriptions swell, and inner states are reported in detail. Instead of a roaming point of view, there are deep plunges into the main character’s mind and senses through stream of consciousness, free indirect discourse, and a curiously omniscient voice, sometimes pitying and sometimes jocular. Compare the driving scenes in the opening lines of two books.

“Why don’t you get out and walk? I would if I were your age. Quicker than sitting with this scum.”

“I’ll be all right,” said Cork, the Albino coding clerk, and looked anxiously at the older man in the driving seat beside him.

(A Small Town in Germany)

Cassidy drove contentedly through the evening sunlight, his face as close to the windshield as the safety belt allowed, his foot alternating diffidently between accelerator and brake as he scanned the narrow lane for unseen hazards. Beside him on the passenger seat, carefully folded into a plastic envelope, lay an Ordnance Survey map of central Somerset. . . . For the attention of Mr. Aldo Cassidy ran the deferential inscription; for Aldo was his first name. He drove, as always, with the greatest concentration, and now and then he hummed to himself with that furtive sincerity common to the tone-deaf.

(The Naïve and Sentimental Lover)

The style seems to me unsure, but clearly the writer is moving beyond terseness toward something more enveloping and commentative.

Returning to the espionage genre, le Carré hit upon another way to fill a big canvas. He resurrected that old formula, the supreme master-mind criminal pitted against our beleagured hero. The master spy isn’t Mabuse or Fu Manchu but the Russian Karla, snug in Kremlin Centre, and George Smiley’s efforts to flush him out are chronicled in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (1974), The Honourable Schoolboy (1977), and Smiley’s People (1979). The mass-market omnibus edition of these runs to nearly a thousand densely packed pages. How did our author manage plots on this new scale?

Wrangling

Chekhov says that if a story tells us that there is a gun on the wall, then subsequently that gun ought to shoot. . . In a mystery novel, however, the gun that hangs on the wall does not fire. Another gun shoots instead.

Viktor Shklovsky

Some expansions are pretty evident. The Quest for Karla trilogy introduces many new characters, mostly people who staff the Circus or who are involved with the institution of espionage: from secretaries and “scalphunters,” the lonely and low-down agents assigned to menial bits of spying, to the very top, such as the Minister who oversees MI6 and Lacon the pliant civil servant overseeing the Circus. Some of these characters are in turn given private lives, with friends and lovers. The connections ramify.

In addition, there are the civilians whose lives are touched by the Cold War chessgame. In The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, that demographic was represented by Liz Gold, Leamas’ lover. But in the Karla trilogy we get a panoply of more or less innocent figures who are pulled into webs of plot and counterplot. And here le Carré does something quite shrewd.

He tends to start the novel with these characters, people at the very edge of the web. Smiley’s People opens with an unassuming Russian émigrée living in Paris. She’s confronted by a Soviet agent telling her she might be permitted to see her long-lost daughter. What does that have to do with Smiley’s cleaning the Circus stables after the mole scandal, or Smiley’s loss of power after the Jerry Westerby misadventure? Positing enigmas at two or three degrees of separation, working inward across the web, le Carré lets the reader gradually sense the lines of force that lead inexorably to the principals.

So le Carré grows his book not merely by expanding his cast. He finds a new balance between thread structure and framed stories. In Smiley’s People, perhaps the most orthodox entry in the trilogy, Smiley investigates the death of an émigré Soviet general, and this entails a fairly standard detective plot. The novelty comes in the fact that the participants Smiley questions are former agents whom he ran, or colleagues retired from the Circus—his people. And what they tell him isn’t rendered in compressed dialogue or summary. Their recollections spread out luxuriantly, claiming considerable interest in their own right, sometimes with only slight points of contact with the main plot, sometimes burying clues that Smiley must dig out.

More intricate is The Honourable Schoolboy, the longest entry in the Karla trilogy. It has two main threads: Jerry Westerby’s efforts to trace money flowing from Moscow to Hong Kong, and Smiley’s struggle to rebuild the Circus. The plot encapsulates the two main types of spy fiction—indeed, the two types that le Carré had already mastered in his earlier books. While Jerry’s plot is suspenseful adventure stuff, Smiley’s plot is inquiry-oriented, like that in Ambler’s classic Mask of Dimitrios (1939). To stretch the canvas on a still bigger frame, le Carré makes Smiley pass investigative assignments to other Circus personnel, like Connie Sachs and Doc di Salis (who get characterized in detail). Indeed, both main lines of action are filled out with rich and lengthy sub-stories. We can study the tradecraft of old Craw, majestic spy-journalist; the puzzling past of Lizzie Worthington, Drake Ko’s mistress; and the enigmas around her lover Ricardo, either dead or flying heedlessly through an Asia in flames.

The Honourable Schoolboy also has a more layered narration than its predecessors. It switches point of view constantly, in the process virtually promoting Peter Guillam to the rank of Smiley’s Watson. Most striking is the plot’s ultimate narrating framework, a sort of institutional memory serving as recording angel. Instead of the all-knowing, somewhat condescending voice of The Naïve and Sentimental Lover, this narration is brisk and brusque. It defends Smiley against those in the intelligence community who, through shortsightedness or malice, misjudged his decisions.

It has been laid at Smiley’s door more than once since the curtain was rung down on the Dolphin case that now was the moment when George should have gone back to Sam Collins and hit him hard and straight just where it hurt. George could have cut a lot of corners that way, say the knowing; he could have saved vital time.

They are talking simplistic nonsense.

This opinionated, godlike narrating agency is never identified. It’s one of the many signs that in the Karla books le Carré is reviving conventions of the triple-decker novel. And so he did; he bid to become our Dickens. (The larger-than-life father-son duo of A Perfect Spy is perhaps his most extravagant exercise in this vein.)

He echoes Wilkie Collins too. For mystery, never far from Dickens’ concern, is central to Collins and le Carré. Sustaining the reader’s interest through mystery seems not as important for our highbrow novelists now; it’s the province of “genre fiction.” But many of the canonical works of fiction and drama turn on secrets that are hinted at, then dramatically exposed (not only Oedipus and Hamlet but works by Henry James, Ibsen, Conrad, O’Neill, Faulkner). On the first page of Crime and Punishment, Raskolnikov thinks, “Why am I going there now? Am I capable of that? Is that serious?” The question of that that keeps us reading. You can argue that the modernist novel, with its fascination with time-juggling and stream of consciousness, found a sort of equivalent for the secrets, deceptions, and puzzles that drive classic tales. In any event, during the first decade of le Carré’s career, he began to explore the ways in which embedded stories can blossom into mysteries.

Burrowing

In my original entry, I didn’t straighten out the plot of Tinker Tailor, but now, as the film nears the end of its theatrical run, I’ll tell the novel’s tale straight. Skip if you don’t want it all ironed out.

Bill Haydon, working for British intelligence, is in the pay of Moscow Centre and its head, Karla. He has been passing information to the Russians for years, but Control, the head of the Circus, is starting to get suspicious. He believes that one of his five top men is a mole. Karla entices Control into sending an agent, Jim Prideaux, to meet a Czech general supposedly going to defect. This leads to a spectacular failure—Prideaux is shot and captured—and allows Karla to install an ambitious dunce, Percy Alleline, in Control’s position.

Haydon is the best and the brightest, the flower of English manhood. Suave, easygoing, with an Oxbridge artistic flair, he is as debonair as Smiley is brooding and inscrutable. Haydon has strained his friendship with Smiley by conducting a brief affair with Smiley’s wife Ann, but that episode was initiated by Karla to make Smiley reluctant to suspect Bill of bigger crimes. Haydon has already tempted Percy with the promise of a double agent, a cultural attaché in London called Polyakov. Through Polyakov Karla feeds the Circus trivia, mixed with bits of good information, to the gratification of Alleline’s inner circle—Haydon, Roy Bland, and Toby Esterhase—as well as Oliver Lacon and the Minister overseeing the bureaucracy. And the Americans approve.

Upon Control’s forced retirement, his team is abandoned and he dies a short time later. A permanently damaged Jim Prideaux is brought back to a new life as French teacher at a minor boy’s school. Smiley retires, while his wife Ann leaves to take up a string of love affairs.

But when a raffish field agent, Ricki Tarr, reports on good authority that there is a mole at the very top of the Circus, Lacon asks Smiley to investigate sub rosa. Smiley installs himself in a shabby hotel and with the help of a youngish colleague, Peter Guillam, and an old friend, Inspector Mendel, he starts patiently scouring the records. Following in Control’s footsteps, Smiley discovers disparities, missing documents, and incompatible testimony. Eventually he is able to pressure Toby into revealing the location of the safe house where Alleline’s cadre meets Polyakov.

By inducing Tarr to send a message galvanizing the Circus’ top brass, Smiley forces the traitor to hurry to meet Polyakov at their usual place. There Smiley, Guillam, and Mendel record Bill Haydon’s incriminating conversation and play it back to the embarrassment of the inner circle. There remains a long epilogue, in which Bill, in detention, confides in Smiley and seems to have no regrets about sending his closest friend Jim Prideaux into a trap and months of torture. Jim has discovered the treachery of his dearest friend and, sneaking into the compound, kills Haydon. While Smiley, now occupying Control’s seat of power, goes to the countryside for a possible reunion with Ann, Jim returns to his school, the object of the boys’ adoration but also a morose, haunted man.

I’ve tried to synopsize the action as a thread, in Shklovsky’s sense, but I can’t do justice to the novel’s exfoliating plotlines. We’ve seen that a detective story basically presents the sleuth going from person to person, asking questions and getting information. Since Smiley is the protagonist, much of what I’ve traced has to be discovered through testimony or flashbacks. As Shklovsky remarks, any mystery in a plot involves some play with time, either ellipsis (what happens in the gap?) or rearranged order (hiding crucial causes) or a late point of attack (so that we must go back to reconstruct why things are as they are).

But your straight-line Q & A investigation can be pretty plodding. Check for yourself by trying to read one of the “classic” detective stories by S. S. Van Dine. Forced to present official reports and characters’ recollections, le Carré skillfully expands those into robust, extensive stories of their own, filled out with characterization, detail, and atmosphere. The recording-angel narrator moves easily from reporting the interrogations to summarizing past action and then to full-blown scenes rendered from the viewpoint of the witnesses.

As in the later books of the trilogy, le Carré’s point of entry is oblique. Instead of starting with Smiley, principal investigator, it starts with Jim Prideaux’s enigmatic arrival at the boys’ school, and even that is presented at one remove, through the vantage point of Bill Roach, aka Jumbo, a hapless “new boy” at the school. Only after that do we meet Smiley, hailed by the obnoxious gossip Roddy Martindale (a convenient expository device) who chats about the usurpation at the Circus. Soon Smiley is summoned to Lacon’s home, where he and Peter learn Ricki Tarr’s story of spying in Hong Kong and falling in love with Irina, the wife of a KGB spy. It’s she that tells him of the mole in the Circus.

Tarr’s tale is the first embedded story, running four chapters. Once Smiley takes the assignment, relatively little happens in the present. His investigation carries him to his old Russia expert, Connie Sachs, and she recounts another block of information, about how her suspicions of Polyakov led her to be sacked from the Circus. Once Smiley is back at his hotel, he starts his reading, and for five chapters we get a big chunk of the past, including Smiley’s discovery of Bill’s affair with Ann. Smiley’s homework is interrupted by a suspenseful string of scenes involving Peter’s smuggling crucial files out of the Circus.

Another embedded story soon follows: Over dinner Smiley tells Peter of his only meeting with Karla, many years before. Then, pursuing yet another clue, Smiley questions Sam Collins, the man on Circus duty the night Jim was ambushed. As in any good detective story, Bill Haydon seems to have an alibi (he heard the news at his club) and acts resolutely un-guilty, bursting into the Circus to take command and demand the return of his old pal Jim. Sam’s embedded story to Smiley is followed by others, from the man who drove Jim into Czechoslovakia and from Jerry Westerby, who heard rumors that the military were waiting for Prideaux. Getting ever closer to the fateful incident that set the whole shuddering machine into motion, Smiley finally hears Jim’s own version of what happened to him that night and in the months afterward.

After so many extended stories—recounted by witnesses, filtered through hearsay, written up in bureaucratic files, commented upon by the recording angel—the plot launches into forward motion. Smiley and his colleagues set their trap, and there’s a suspenseful set-piece spanning two chapters. Le Carré alternates among Tarr in Paris, Mendel watching affairs at the Circus, and Smiley waiting in the safe house to trap the traitor. There follows an equally crosscut epilogue, with Bill and Smiley’s confrontations alternating with vignettes of other characters—including a young woman, introduced for the first time, who seems to have borne a child by Bill. The book concludes with Smiley, waiting to meet Ann and meditating on what drove Bill.

Scalphunter

In adapting a novel for the screen there is a natural temptation to dramatize the information supplied by narrative description in the original text by turning it into dialogue, but this is generally to be resisted. Where possible it should be translated into action, gesture, imagery. Much of it can be dispensed with altogether.

David Lodge

Imagine trying to adapt this monster! Respecting the novel’s construction would demand a cascade of flashbacks, long tales framed by Smiley’s investigation. The seven-installment BBC series, scripted by Arthur Hopwood, took the simpler option of starting with a scene that is presented very late in the novel, in Jim’s embedded story told to Smiley. The series opens with Control summoning Jim and sending him off to Czechoslovakia; Jim is shot and Control is cast out. Clarifying the string of events this way, and giving us a decent action scene early on, has its cost: Smiley doesn’t enter the plot for nearly 23 minutes. Yet this construction does obliquely retain the portmanteau quality of the novel’s concept, in which sustained blocks of action are allowed to stretch and breathe.

Soon, as in the novel, the TV series gives us Ricki Tarr’s story of his affair with Irina, presented as a discrete flashback. Then Smiley’s trawl through the files is supplemented by his visits to Connie and others. Sometimes their recollections are dramatized in flashbacks, other times we simply watch them tell Smiley of them. Fortunately for the viewer, there are also scenes of Smiley bringing Peter up to date, and briefing Lacon on current discoveries. Because the BBC series was broadcast in weekly episodes, this sort of backtracking was necessary. And since Hopcraft had several hours to fill, the plotting could be somewhat spacious. Nonetheless, the book’s oscillating time scheme was somewhat flattened out, and the block construction—main thread interrupted by inset stories—was compressed. The inset tales didn’t expand to their novelistic dimensions.

The Tinker Tailor film, of course, had to be much more squeezed down. I mentioned in the earlier entry that the screenwriters compared their structure to a mosaic, and I followed this out in my discussion of how the narration was elliptical and fragmentary, leaving out redundancies that are usually required in popular film. Many scenes are both spacious and laconic. The rhythm is slow, and we’re given time to see and hear everything; but that “everything” might be only a voice dimly overheard, or a doorbell, or an image that gives one piece of information.

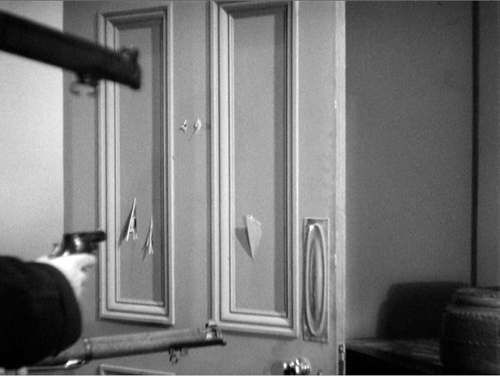

Take an instance I didn’t pick out in the original post. In order to steal a file, Peter Guillam has arranged for Mendel to call him, pretending to be a garage mechanic.

The call provides a pretext for Guillam’s retrieving his bag from the security officer, so he can slip the file inside.

George Formby’s music-hall tune “Mr. Wu’s a Window Cleaner Now” is playing on the garage radio. It’s carried down the phone line to the call-screener at the Circus, who murmurs along with it as the call is recorded.

After the tense meeting with the Circus cadre, Guillam has apparently sneaked the file out. But on the staircase an offscreen voice softly sings “Mr. Wu” before we see the source, not Guillam but Roy Bland. He descends slightly ahead of Guillam.

Guillam follows right behind, pausing and looking off nervously as Bland passes through the foreground.

The empty stretch of the staircase shot allows us to think that it’s Guillam offscreen, humming the tune he heard on the line, so it’s a surprise when Bland appears. We realize that he must have heard the call, or the recording.

Another film would have cut away during Guillam’s maneuver to show Bland and his colleagues listening to Peter’s fake conversation. That would have dialed up the suspense: Will they detect the trick? Instead, showing the lady on the phone lets us know that the call is being recorded. Only retrospectively—and by a single piece of information that slips by—do we realize that Bland has heard the conversation. Guillam is being watched closely. There’s a meta-message here too: By humming the tune, Bland lets Guillam know he’s overheard the call. Bland’s casual feint fits with the intimidation of Guillam that began when he was called into Percy’s meeting.

In all, the moment’s oblique, ricocheting transmission of story information could easily be missed. (In the book, it’s Bill who waylays Guillam and asks if he’s seeing Smiley. “Guillam’s world, which was showing signs till then of steadying to a sensible pace, plunged violently.”) The film’s script and direction have followed David Lodge’s suggestion of translating Peter’s sudden panic into images and sounds, but more laconic ones than we usually find.

More broadly, the film’s stinginess about supplying information extends to its protagonist. As I suggested in the first post, Smiley doesn’t just solve mysteries—he is one. What does he want? Oldman’s dry, impassive performance bottles the shrewdness, sternness, and pain that Guinness let leak out in the series. It still seems to me that the film’s Smiley is playing a waiting game; even the “Aha!” moment near the climax, when he seems to have hit upon something, proves to be obscure.

After the montage parades the suspects and shows the shifting train tracks outside Smiley’s dingy hotel, the narration doesn’t present the classic giveaway clue or blinding insight. Immediately we see Smiley, by force of will, bullying his superiors and Toby into giving him the information he needs to trap the mole . . . whose identity isn’t pinned down until the ambush. Smiley’s emotion bursts forth only once more, in his confrontation in Haydon’s cell. After a slight confirmatory smile (Prideaux, Smiley surmises, “knew deep down it was you all along”), Smiley asks if Karla ever considered letting Bill take over Control’s post.

Bill, angry: “I’m not his bloody office boy!”

Smiley, almost roaring, but with expression unchanged: “What are you then, Bill?”

Bill, after a pause, in a subdued, strangled voice: “I’m someone who has made his mark.”

Smiley exhales, the burst of energy gone, and turns slightly aside.

Smiley’s outburst here is his most vehement utterance in the movie. By the epilogue, Smiley, still unsmiling, has assumed his place as Control’s successor.

Mole-hunters

You have to let go of the idea of explaining it all to the audience. You have to make it so complex that the audience understands that they can’t understand all of it. . . . We had to make it trustworthy and credible but also so complex that you couldn’t penetrate it. . . but not so incomprehensible that it put people off.

Dino Jonsäter, editor, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy

More than most plot types, I think, a mystery story lures us into analysis. Think of the endless fan probes into Memento, Primer, Donnie Darko, and the like. The secrets in the action, and the roundabout tactics of recounting it, invite us to think about narrative technique more abstractly than we usually do. We’re encouraged to study how we’ve been misled. Analysis is a bit like detective work, but also like academic research. The analyst has a lot in common with Smiley and his patient burrowing into the files. He is, in the books, an amateur philologist and a scholar of German poetry.

For many, the mysteries of Tinker Tailor have aroused an urge to analyze. Jim Emerson has compiled a handy roundup of exceptional probes into the film. Some of my readers have filed perceptive reports as well. Filmmaker and teacher Stew Fyfe offers this:

I agree that what they’ve done with the film is subtract most of the redundancy, with bits of information offered up only once. If you missed it, you missed it. I was surprised when Smiley actually told Ricki Tarr that he missed the chip in the door; that seemed like the movie was taking it uncharacteristically easy on the audience for a moment. It was kind of thrilling to see a film that trusts its audience to keep up with it the way this one does. I wonder if they might have initially stripped more info out and then put some back in during the editing process. . . .

The other thing that has struck me is how very legible the film is when you see it a second time. Most everything does indeed seem to be there, in frame, but the audience isn’t cued to be looking for certain things. Ann does have some slight reaction to Bill Haydon when he sits down at the party, if I remember correctly (something cues Smiley to turn and look at him). And it’s clear why Bland offers to accompany Guillam to lunch.

Or performances take on a different meaning based on the information we have by the end of the film. It’s clear by the end that some sort of relationship was going on between Haydon and Prideaux, which makes Haydon’s conversation on the phone the night Prideaux was captured play differently the second time around. (The Haydon-Prideaux relationship was actually one thing that didn’t work for me the first time watching the film. The nature of their relationship hadn’t registered, so Prideaux’s act of shooting Haydon didn’t have the same emotional heft. The scene played much more strongly the second time I saw the film.)

I guess Smiley’s eureka moment is a little bit of a leap, but otherwise, it’s all there.

And here’s Ben Slater, a long-time le Carré admirer.

I read the screenplay, officially online as part of Focus’s awards campaign (http://focusawards2011.com/workspace/ttss-screenplay.pdf) , and it’s fascinating how much of the adaptation was reworked and restructured in production.

The film was intended to open ‘cold’ with Prideaux’s mission. His meeting with Control – now the opening sequence – wasn’t till much later. The abortive mission and the Christmas party were intended to only be returned to once each, and yielded most of their secrets (Karla’s presence/Bill and Ann) on the first go-round.

There are myriad tiny and fairly dramatic changes – in the script Ricki Tarr’s first appearance is much more impactful, the killing of Bill is very different, etc. Some of these are changes Alfredson must have made during filming, others suggest a great deal of time spent re-arranging and re-sculpting the fragments of the plot in editing – trying to make the story flow as elegantly as possible. I imagine this was tough!

Interestingly, the bold decision to make Smiley silent for so long in the opening scenes seems to have been made in post. They simply cut all his first lines of dialogue. And Smiley’s closing line of the film was also shot and cut – “Shall we begin?”

It’s impossible to watch the film without running the novel and the TV series alongside it, and it struggles to compete in terms of narrative and character, but the real triumph is arguably the ambience of broken England it evokes – cigarettes, whiskey, bad burgers, bad skin and failed lives.

So mystery stories tease us into analysis. But they also flaunt some common characteristics of all storytelling. Encountering any tale, we always want to know what comes next, but we’re also curious about what was left out, or lied about, or presented in passing, or hidden in plain sight. The writer is the mole, and we’re the mole-hunters. As novelist Jane Smiley puts it:

The most basic conviction of every novelist from Lady Murasaki on . . . is that things are not as they appear.

My arguments from Victor Shklovsky come from various essays in Theory of Prose, trans. Benjamin Sher (Dalkey Archive, 1991); the epigraph is from the essay “Sherlock Holmes and the Mystery Story,” 110-111. The David Lodge epigraph is from his “Novel, Screenplay, Stage Play: Three Ways of Telling a Story,” in Lodge, The Practice of Writing (Penguin, 1997), 215. The Jane Smalley quotation is in her 13 Ways of Looking at the Novel (Anchor, 2006), 49. For more thoughts from editor Dino Jonsäter, go to “Cutting Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy” on Creative Cow.

I’ve signaled before the marvelous two-part interview with le Carré for the CBC, but why not do it again? Since writing the last piece I also discovered a helpful interview with Tomas Alfredson and Gary Oldman at Film School Rejects. I have other notes on the Hong Kong atmosphere of The Honourable Schoolboy here.