Archive for the 'National cinemas: Iran' Category

Il Cinema Ritrovato: revelations from India and Iran

Pather Panchali

Kristin here:

The second half of my week at the Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna was centered around two Asian events: a small program of Iranian films from the 1960s and 1970s and the restored Apu trilogy. In between those screenings I tried to fit in some programs of pre-1920s cinema.

Bringing the Apu Trilogy back from the ashes

That was the title of a panel presentation during the festival, one which I missed because I was watching the first of the four Iranian films. In this case the metaphor is literal. The original negatives of the Apu films were stored in a London warehouse, and in 1993 a fire damaged them extensively.

In 2013, The Criterion Collection and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences began a collaborative restoration. Working meticulously by hand and employing an innovative rehydration technique, experts at L’Immagine Ritrovata in Bologna rescued the images for about 40 percent of Pather Panchali and 60 percent of Aparajito. The negative of Apu Sansar (The World of Apu) was wholly lost. For it and the missing parts of the other two films, footage from fine-grained masters and duplicate negatives from various archives was used. The restoration was done in 4K. (For an interview with Lee Kline, Criterion’s technical director, see here. There is a short but informative short film on the restoration, including some before-and-after comparisons, on Vimeo.)

The result is spectacular, far better than one would expect, given the dire circumstances the restorers faced. It was a privilege to see the entire trilogy over three days on the huge screen of the Cinema Arlecchino from the front row. There were times when the replacement footage was obvious, but for the most part, the images look pristine. They also look like film, with no hint of video-y quality about them.

I had seen the trilogy only once, in 16mm back in my graduate-school days. At the time, I admired it but wasn’t bowled over. Sitting through the Ritrovato screenings, I found it a profoundly moving and beautiful experience. Satyajit Ray manages both to maintain a quiet, leisurely pace and to compress the hero’s life, from birth to early adulthood, into three parts totalling less than six hours.

Apu’s strict but devoted mother (below left, in Aparajito) anchors the first two films, gaining our sympathy despite her scolding and worrying. Apu’s wife, Apurna (below right, in Apu Sansar), is in the third film for a remarkably short time. Yet we quickly come to understand her love for this unknown man whom she marries almost by accident, her sense of humor, and her compassion, all of which are vital to our sympathy for Apu’s utter devastation after her death. Indeed, the trilogy involves five major deaths, all of which makes the hopeful ending the more affecting.

Presumably The Criterion Collection will bring out a Blu-ray set of the three films, though no date has yet been announced.

Iran’s own New Wave

Admirers of Abbas Kiarostami, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Asghar Farhadi, Jafar Panahi, and other notable directors of the Iranian cinema of the past few decades might be curious about their forerunners. Iranian film critic and historian Ehsan Khoshbakht has begun to satisfy that curiosity by programing a short series of classics of pre-Revolutionary cinema. According to his program notes (available in their entirety online), the four films shown in Bologna constitute about a quarter of the output of the Iranian New Wave. I hope there will be further screenings at future festivals.

As Khoshbakht warned in introducing the earliest film in the series, Shab-e Ghuzi (Night of the Hunchback, 1965), it is not a masterpiece and certainly not a forerunner of the filmmaking that would later bring Iran to prominence in international festivals and art cinema. Director Farrokh Ghaffari was a pioneer of Iranian filmmaking beginning in the 1950s, but he is perhaps equally important in having started the first Iranian film archive.

Night of the Hunchback is a black comedy with a story loosely derived from The Trouble with Harry. A player in a cheap entertainment troupe is accidentally killed, and the bulk of the film follows his corpse as it is passed from one group of characters to another; these include a pair of smugglers running a beauty salon, who provide much of the film’s humor (above). Most try to dispose of it, but a society woman trails it in the hope of retrieving an incriminating document in its jacket pocket. By Western standards it seems like a fairly mainstream commercial work, but it departed from commercial Iranian cinema, according to Khoshbakht, “with its respect for folklore and its bitter portrayal of the upper class.” It was a commercial flop but gained some attention at European film festivals.

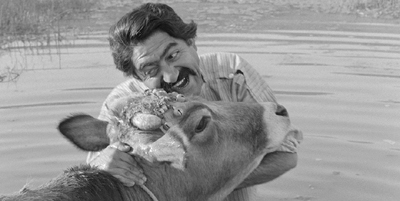

The most famous film of the era is Gaav (The Cow, dir. Dariush Mehrjui, 1969). It centers around Hassan, the owner of his village’s sole cow. He dotes on the beast, as is quickly established in an early scene when he affectionately bathes her.

When the cow mysteriously dies (a cause is hinted at but never confirmed), the villages lament the loss of their only source of milk, but they also worry about how Hassan will react when he hears the news.

Although Hassan is the evident protagonist of the film, the drama centers more around the ignorance, lack of judgment, and even cruelty of the villagers. The film begins not by introducing Hassan and his cow but with a disturbing scene of the local children chasing and tormenting a mentally defective young man. This establishes the tone for several later scenes.

When the cow’s death is discovered, the small group of men who wield authority initially concoct a story of the cow having run away, and the villagers bury the carcass (bottom). As Hassan descends slowly into madness, the people supposedly trying to help him make every possible wrong decision, leading to disaster.

If the films I discussed in my previous entry extolled the virtues of village life and represented leaving home as unwise, The Cow is just the opposite. Cut off from the outer world, the villagers have little education or ability to come up with logical solutions to problems. It’s a theme repeated in the other two Iranian fiction films on the program as well.

Yek Ettefagh-e sadeh (A Simple Event, dir. Shrab Sahid Saless, 1973), the latest of the films shown, seems the most obvious forerunner of the wave of Iranian cinema that started in the 1980s. It closely follows the daily routine of a young, unnamed boy living in a small town on the edge of the Caspian Sea. We see him at school, helping sell the few fish that his father catches each day, eating and trying to study in the almost unfurnished house he shares with his father and sickly mother.

There’s little dialogue, apart from scenes in the school. I believe the boy speaks two lines in the entire film, and his father communicates with him only occasionally, to order him around: “Close the door” or “Study.” Much of the action consists of the boy running through the streets on errands, including his night-time visit to fetch a doctor for his ailing mother (below).

Although there’s a superficial resemblance between A Simple Event and the later films of the “child quest” genre, I see considerable differences as well. In films like Kiarostami’s Where Is My Friend’s Home? or Panahi’s The Mirror, the child protagonists have clear-cut goals which they have decided upon themselves. They are stubborn and determined, and as they doggedly pursue their goals we are never unsure about their motives.

In A Simple Event the boy has no goal, and we learn almost nothing about his character. Is he really as stupid as his teacher believes, or is he behind his classmates because he gets little chance to do his homework? Does he love his mother or is he indifferent to her declining health? Is he resentful but cowed by his elders? Or is he resigned and accepting of his lot? We have no way of knowing. His one independent action is to buy a bottle of Coca-Cola to go with his usual meager meal after his father uncharacteristically gives him a little money.

There’s certainly a suggestion, once again, that small-town life is deadening to people. The rote learning and lack of relevance in the subjects taught in school help explain the lack of imagination and the resignation to their situation among the students.

My suspicion is that later directors may have seen the potential in A Simple Event and built upon it, introducing a greater empathy with their child protagonists and certain greater drama and suspense.

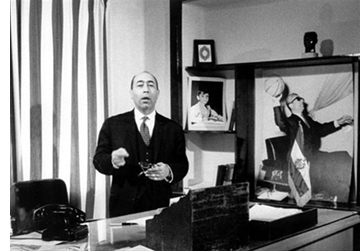

To me, the surprise among the Iranian films was Oon Shab Ke Baroon Oomad Ya Hemase-Ye Roosta Zade-ye Gorgani (The Night It Rained or the Epic of the Gorgan Village Boy, dir. Kamran Shirdel, 1967). It’s a  sophisticated investigative documentary that reminded me of the work of Erroll Morris.

sophisticated investigative documentary that reminded me of the work of Erroll Morris.

The film begins with a written report on the making of the film itself, submitted to the authorities by Shirdel. It seems to describe earnest attempts to document an inspiring story that had been widely circulated in newspapers. On a rainy night, a boy in the village of Gorgon had discovered that flooding had undermined the local train tracks; he signaled an oncoming train by setting his jacket alight, successfully stopping it and saving 200 passengers’ lives.

Doubt begins to creep in, though. Among the many newspaper titles shown trumpeting the boy’s feat, we find one calling it a pack of lies. Shirdel’s report indicates that his team could not find the boy and set out to interview various people. Gradually it becomes apparent that the whole story was concocted and that the train–a cargo train with no passengers aboard–was stopped by local railway officials. Throughout the film, there are further passages from the production report, describing the filming work as if it were for a simple, laudatory documentary about the heroic boy. We see, however, that much of the filming undermines that heroism and satirizes the government’s willingness to perpetuate false accounts of it.

Shirdel carefully avoids making that point explicitly. He intercuts interview scenes, some of the boy rattling off his story and some of newspaper editors defending the story (above). In other scenes, we hear from indignant railway officials and an editor who dismisses the incident as pure fiction. The director seems to let us decide on the truth, but the the absurdity of boy’s supposed heroism becomes increasingly apparent.

Not surprisingly, Shirdel’s film was banned. Six years later, according to the program notes, “it was deemed harmless. It was then premiered at the Tehran International Film Festival where it won the Best Short Film award.” Clearly the officials who cleared it for release missed the ironic underpinnings of the film.

The Night It Rained (and perhaps others of Shirdel’s films) may have offered a model of reflexive filmmaking that later directors picked up on. Close-up, The Mirror, Salaam Cinema, and Through the Olive Trees all bring filmmaking into the stories they tell.

Thanks to Ramin S. Khanjani for some corrections concerning the Iranian section of this entry. His article on The Night of the Hunchback, “Actors and Conspiracies,” was published in Film International 15, 3/4 (Autumn 2009/Winter 2010): 66-71.

The Cow.

Middle-Eastern fare at VIFF

Winter Sleep.

Kristin here:

Iranian cinema moves on

Maybe it’s just the particular selection of Iranian films at this year’s festival, but I sensed a shift from the ones we’ve seen in previous years. Last year I titled one of my entries “Familiar Middle-Eastern filmmakers return to Viff.” This year familiar names are missing, including Kiarostami, Panahi, Rasoulof, and Farhadi. (Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s new feature, The President, was at Venice but not here at VIFF.) Moreover, all three of the Iranian fiction features this year depart from some conventions we’ve grown used to in the New Iranian Cinema of the past decades.

Whether A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014) is actually an Iranian film is debatable, though it is listed as such in the program. Its director, Ana Lily Amirpour, was raised in England and subsequently moved to the USA, where she studied filmmaking at UCLA. A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is her first feature and has American backing (including Elijah Wood as one of several executive directors) and was shot in California. Amirpour is of Iranian descent, and the film is in Farsi, which may be enough to have it considered Iranian.

It’s hard to imagine, however, such a film being made in Iran. It’s a vampire film, taking place in an imaginary town called Bad City, perhaps located in Iran but perhaps not. Its setting look distinctly like the less picturesque parts of the American West:

Amirpour has fashioned a remarkably good pastiche of an American widescreen, black-and-white genre film of the late 1950s or early 1960s, as this image and the one at the bottom of this entry demonstrate. As the Variety review points out, the look is also informed by graphic novels, notably Sin City. Indeed, this summer Amirpour has published a brief graphic novel with the same title as her film; it’s apparently a prequel to the movie’s story. Given that it is labeled #1, the artist presumably envisions a series.

The genre is the vampire film, though this one is hardly conventional. The vampire is the Girl of the title, and the director has taken amusing advantage of the resemblance between her triangular black hijab and the classic floor-length cloak worn by screen vampires, such as that of Bela Lugosi in the 1931 Dracula:

The heroine moves eerily through the streets of the town (see bottom), picking as her victims men who have exploited women. A romance develops between her and a more sensitive young man, clearly modeled on James Dean.

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night played at Sundance and has been picked up for American Distribution by Kino Lorber, apparently with an October release planned.

The two other Iranian films are what David has dubbed “network narratives.” One is straightforwardly so, the other far less so.

Rakhshan Bani-Etemad’s Tales (2014) in some ways develops on the classic quest narrative of so many Iranian classics since the 1980s, where hero or heroine (often a child) doggedly set out to accomplish something, with the struggle laid out in detail. In Tales the questing characters are multiplied, with their paths crossing and sometime re-crossing.

Unlike in most of the earlier films, these quests don’t always yield results, and hence closure. The characters are mostly involved in seeking help of some sort, sometimes from other people, sometimes from a government institution. The cumulative effect is to suggest a society that has lost the ability or the will to respond, even to desperate pleas.

The film begins with a filmmaker riding in a friend’s cab, shooting the passing cityscape. He immediately drops out of the story, though he will return. Ironically, the story’s action begins with a failed attempt to help someone. The cab driver is hailed by a prostitute with a sick child. Recognizing her as an old friend of his family’s, he buys medicine and a toy for the child, only to find that the woman has disappeared into the night.

Arriving home, he tells his mother of this encounter. We then follow her in a scene in an office building, where she tries to fill out a form complaining about not having received her pension. A gentleman in the corridor helps her, and we follow him into a meeting with a petty bureaucrat who takes calls from his wife and mistress, ignoring what the man is trying to tell him.

A central scene returns to the mother, now on a bus of protestors. The same filmmaker whom we saw at the opening is making a film about their personal plights. We watch through the viewfinder as the mother pleads for help. It’s not clear whom the film is aimed at or who will eventually see it. Later in Tales, the filmmaker remarks that all films eventually get seen, but this seems far too vague to hold out much hope for those caught in a maze of bureaucratic red tape and neglect.

The network structure reportedly resulted from the fact that under the Ahmadinejad regime Bani-Etemad could only get a license to make a series of shorts. Subsequently she was able to weave these together into a feature.

Bani-Etemad, who also produced Tales, is considered Iran’s top female director. Here she brings back some characters from her earlier films, including Dr. Dabiri, from Gilaneh (2005), and Sarah, from Nargess (1992). The VIFF program quotes her as saying, “Tales returns to the characters of my previous films under today’s circumstances.”

Finally there is Fish and Cat (2013), which elicited mostly praising reviews when it debuted in Venice. (For an example, see our friend Alissa Simon’s take on it for Variety.)

Despite running a lengthy 134 minutes, director Shahram Mokri shot the entirety as one lengthy take, without benefit of CGI. A sinister mood is set up immediately when a title hints that it will concern some restaurant owners in a remote district who may have used human flesh in their meat dishes. Two owners of the restaurant are introduced in the opening scene, and we follow them as they set out on a path through the nearby woods, carrying weapons, tools, and a bag soaked in what looks like blood:

The pair chat until their path crosses that of Kazim, a young man participating in an annual kite-flying event to take place by a nearby lake; he’s trying to ditch his clinging father. We follow him to the lake, then leave him to latch onto Parviz, who is trying to organize the young people arriving for the event. And so it goes, until eventually the brief scenes between the people who meet and part begin to repeat, but from a different vantage point. Much of the action involves the camera tracking with the characters from behind, as in the frame above, resulting in an occasional difficulty in identifying whom we’re watching.

The tone remains ominous throughout, with the two thugs and a third accomplice intruding at intervals, perhaps with murderous intentions. There’s also plenty of dark humor as well, and despite the slow unrolling of the action, the film remains absorbing throughout. Some viewers will be tempted to see the film on DVD/BD again, trying to work out the complicated looping chronology of the plot–possibly diagramming it, as the filmmakers presumably had to.

Those who can’t do

We wrote about Israeli director Nadav Lapid’s first feature, Policeman, in our 2011 VIFF report. This year he is back with his second, The Kindergarten Teacher (2014).

The film is a psychological study of young woman, Nira, who is an apparently ordinary and devoted kindergarten teacher. She learns that one of her small charges, Yoav, a shy, uncommunicative five-year-old boy, has an odd habit. Occasionally he begins to pace back and forth, declaring “I have a poem” and then reciting a short poem that would do credit to an adult author.

Nira’s reaction to this apparent prodigy is shifting, occasionally ambiguous, and increasingly disturbing. We are confined almost entirely to what she observes and does, so we get no other view of Yoav except when his nanny and father talk with Nira.

Initially she seems inclined to take advantage of Yoav. We witness her reciting one of his poems as her own at a poetry-writing group that she attends. This premise is soon dropped, however, when Nira takes Yoav under her wing. She favors him over his classmates and encouraging his artistic impulses. Eventually she tries to take control of him, clearly picturing herself as gaining reflected glory from being a mentor to a great artist.

Given the limited point of view, we are encouraged to speculate as to how Yoav comes up with his poems and how far Nira will go in crafting the triumphant public career that she clearly wants for the boy. When she discovers that his boorish, business-minded father has no use for poetry, she increasingly tries to control Yoav, taking him to a public poetry-reading and getting him to recite onstage:

Cumulatively the film traces a slow and disturbing path toward her greater obsession. A subtly presented clue suggests the nature of Yoav’s recitations–to us, that is, if we catch it. Nira misses it, or chooses to ignore it.

Once again in Anatolia

Three years ago we wrote about Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Once upon a Time in Anatolia as one of our favorite films of the 2011 VIFF. Now Ceylan is back with another long film, Winter Sleep (2014), and again it stood out among the films we saw this year.

The film was shot in the Cappadocia region of Anatolia in central Turkey. The area is a major tourist attraction, with caves, “fairy chimneys” and other spectacular stone formations, rock-cut chapels, and structures from antiquity.

The protagonist, Aydin, is an ex-theater actor now retired and running a hotel made up partly of rooms cut into the picturesque rock formations. It’s the winter season, with only a Japanese couple and a motorcycle devotee staying at the hotel, and Aydin has plenty of time to write columns for the local paper and bicker with his young wife Nihal and embittered, recently divorced sister Necla:

This time there is no crime investigation or mystery around which the plot centers. Instead the narrative is a character study, played out partly in long conversations between Aydin and the two women. There are also scenes in which Aydin reacts with indifference to the sufferings of his impoverished tenants.

The early part of the film is given over to Aydin, who at first seem mildly sympathetic, brilliant and creative. But as he converses with Necla in a lengthy central scene in his study, his remorselessly sardonic sister picks apart his flaws in a verbal duel between two equally witty characters. Later, Nihal feels beaten down by Aydin’s opposition to her charitable work, the only activity that gives her satisfaction in this isolated life, and she finishes the job of exposing Aydin’s selfishness.

The program notes compare the film to the plays of Chekhov, and there is a definite similarity, both in the conversations and in the contrasts between the wealthy family and the working-class people who resent being dependent upon them. Despite the fact that much of the film consists of long conversation scenes–and runs for 196 minutes–the large, sold-out audience with whom we watched the film were dead silent, clearly captivated by the story. Unlike Chekhov, in the end the film offers a glimmer of hope for the characters.

Ceylan has said that he shot in the distinctive landscapes of Cappadocia only reluctantly:

I actually didn’t want to use it, but I had to. I originally wanted a very simple, plain place, but the film had to be set in a tourist area, and I needed a hotel that is a little isolated, outside of town. Cappadocia was the only place I could find that in the winter time still had tourists.

I was afraid of shooting in Cappadocia because it might have been too beautiful, too interesting. But I didn’t show it too much, I hope.

Ceylan succeeded, I think. There are enough shots of the rock formations to impress us, but they are used sparingly. One might interpret the landscapes as reflections of the characters’ inner turmoil, in much the way that Maurice Stiller and especially Victor Sjöström used Scandinavian landscapes in their classic films of the 1910s and 1920s. (See top, where Aydin pauses to think near some rocky outcroppings.)

It certainly shows enough that Winter Sleep might cause a rise in tourism among art-cinema audiences. One hotel’s blog has already mentioned the film as a way of luring customers.

Winter Sleep won the Palme d’Or at Cannes this year and will receive an “awards-season” release in the USA by Adopt Films.

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night.

Familiar Middle-Eastern filmmakers return to VIFF

Closed Curtain (2013).

Kristin here:

Two years ago David and I wrote about a group of Iranian and Israeli films that featured prominently in the 2011 VIFF program. This year’s program boasted several more, many of them by the same directors.

Closed Curtain (Jafar Panahi and Kambuzia Partovi, 2013)

Despite still being banned from filmmaking and forbidden to leave Iran, Panahi has followed This is Not a Film with another fascinating feature that has made its way abroad. This time he co-directs with Kambuzia Partovi, who also plays one of the main characters, a screenwriter.

The writer flees to a seaside house (apparently Panahi’s) to hide his dog from a roundup of animals deemed “unclean” under Islam. Once ensconced, the writer tries to conceal his pet by sealing the many large windows with opaque curtains. Eventually their privacy is invaded by another refugee, a young woman sought by local police for participating in a nearby party.

This first section of the film seems to be a straightforward allegory for Panahi’s own situation, but well after the midpoint, Panahi himself appears and takes over as the main character. With the curtains removed, he stares at the pond behind the house, seemingly having a vision of himself amid the beauties of nature. He also gazes at the sea in front of the house, envisioning himself walking into it to commit suicide.

The opening stretches emphasize suspense, when the writer hears voices and sirens outside, and unseen officials hammer against the door. The result is an image of the creative artist forced to conceal himself from forces of authority. With Panahi’s appearance, the film becomes more subjective than allegorical, and the abrupt juxtaposition of the two parts of the film create a puzzling whole. But that whole is rigorously filmed and arouses interest throughout.

Manuscripts Don’t Burn (Mohammad Rasoulof, 2013)

In 2010, I posted about Rasoulof’s beautiful film, The White Meadows (2009), an overtly allegorical film about the sufferings of various sectors of Iranian society. At that point I wrote, “He was arrested alongside Jafar Panahi (who edited The White Meadows) and about a dozen others on March 2. Fortunately he was released fairly soon, on March 17. What his future as a director in Iran is remains to be seen.” Most immediately, he was given a prison sentence and banned from filmmaking. Neither condition evidently kept him from finishing the impressive Goodbye (2011), which I discussed here. More recently, upon returning to Iran from Europe, Rasoulof has had his passport seized and is unable to travel or to reunite with his family. Most observers believe that this treatment is a response to his harshly critical new film, Manuscripts Don’t Burn, which has attracted attention at several festivals.

Manuscripts Don’t Burn differs considerably from The White Meadows. There is no hint of allegory here as Rasoulof examines the state surveillance system.The plot centers around two dissident authors and their strategies for hiding their manuscripts and evading the authorities. While a ruthless, educated young official decides on two authors’ fates, two working-class men carry out the kidnapping, torture, and murders that he orders. The hitmenare seen as victims themselves, as one of them, trying to pay medical bills for a sick child, continually finds that his last job’s payment has not yet been transferred to his bank account. They endure stakeouts in chilly weather and grab takeout food on the fly. The whole film is shot in muted tones (in both Tehran and Hamburg) and conveys a sense of unrelenting grimness.

The plot is drawn from unspecified real-life events, and the film cautiously carries no credits for cast or crew. (For more information on the film’s background, see Stephen Dalton’s informative review from the film’s premiere at Cannes.)

The Past (Asghar Farhadi, 2013)

Since A Separation (2012; see our entry here) became the first Iranian film to win an Oscar for best foreign-language film, Farhadi has become the most prominent director working in that country. This is witnessed by the fact that his new film, The Past, has been put forth as Iran’s candidate for this year’s Academy nomination.

The plot of the new film draws upon familiar strategies that created a strong, moving situation in A Separation. Again a husband and wife are on the brink of divorce. In this case, the husband, Ahmad, is Iranian, and the wife, Marie is French. Clearly they had lived together for a time in France, since when Ahmad arrives from Tehran, he knows how to get around Paris. Marie has two daughters from a previous marriage and plans to marry the small-businessman Samir, by whom she is pregnant. Samir has a morose young son who resists the idea of having Marie as a mother.

With this larger cast of characters, disagreements and obstacles pile up. Marie is extremely strict and strong-willed. Her older daughter is rebellious and stays out late. Ahmad tries to mediate between Samir’s miserable son and Marie’s scolding, while Samir tries to please Marie and still help his son adjust to the upcoming marriage.

As in A Separation, The Past builds up a mystery about an unhappy event. Samir’s wife has attempted suicide. What led her to this desperate measure? Her chronic depression? An embarrassing argument with one of Samir’s customers? Or did she know of Samir’s affair with Marie? Ahmad’s attempts to solve this mystery provide a strong, intriguing subplot alongside the shifting conflicts among the main adult characters.

With so many characters involved, the accumulation of problems and unhappiness eventually threatens to tip over into an exasperating melodrama. But I think Farhadi juggles all these motivations and events so well that we never feel that he has gone too far.

There has been some controversy over the fact that the film was shot entirely in France and therefore has little Iranian about it. Indeed, the Farsi-speaking emigrés who attended the VIFF screening to hear their native language spoken were perhaps disappointed that it was all in French. Yet in an ensemble cast, Ahmad remains the central character, helping to reconcile the others and comfort the three children (as in a rare cheerful moment when he helps the younger ones get a toy out of a tree).

If not quite as satisfying a film overall as A Separation, The Past confirms Farhadi as an Iranian director who can make appealing films for an international audience.

Trapped (Parviz Shahbazi, 2012)

Trapped is probably closer than most Iranian films shown at festivals to the sort of thing seen by popular audiences in its home country. The program notes describe it as a “moral thriller.” It revolves around Nazanin, a studious first-year medical student (see image at bottom) forced through lack of dormitory space to share a flat with party-loving Sahar, who is trying to leave Iran. Sahar has borrowed money to pay for her exit visa and, unable to pay it back, is imprisoned. Nazanin struggles selflessly to help her out, including foolishly signing a promissory note taking on Sahar’s debt and even sharing the threat of imprisonment.

The plot reminded me of the “child quest” tales that were prominent in the golden age of the Iranian cinema of the 1980s and 1990s, such as The Mirror and Where Is My Friend’s Home. (Shahbazi was the assistant director of Panahi’s The White Balloon, as well as conceiving its basic premise.) Here the heroine is distinctly older than the protagonists of those films, but she retains a naivete that makes her seem more childlike than the other characters, who manipulate and ultimately threaten her.

While Trapped doesn’t have the simplicity and charm of those earlier films, it offers an absorbing story. It paints a grim picture of Tehran and gives some insight into the realities of life there. Like many Iranian films, it raises the prospect of emigration, though in this case Nazanin’s strong desire to stay in the country and become a doctor is held up as the better choice.

A Place in Heaven (Yossi Madmony, 2013)

Two years ago I also reported on Madmony’s Restoration. A Place in Heaven is a considerably more ambitious film. It traces the life of a military hero, known only by his wildly inappropriate nickname Bambi, across much of Israeli history. The title derives from a flashback scene early on, when a cook at a military camp praises Bambi’s brave deeds and remarks that he has already earned a place in heaven. A secular Jew, Bambi scoffs at the notion and signs an impromptu contract trading that place to the cook in exchange for a daily spicy omelet.

Although Bambi dotes on his son Nimrod, the boy grows up to become a strictly religious Jew who disapproves of much that his father does. Still, when Bambi is on his deathbed, Nimrod goes in search of the cook to get back the place in heaven. As with Restoration, the plot is largely based around the father-son relationship, though there is also a touching and tragically short relationship between Bambi and his beautiful wife.

Unlike the largely urban Restoration, this film shows off the bleakly beautiful landscapes of Israel’s desert.

There were many other striking and moving films on display at VIFF this year. David and I really can’t do justice to all of them, but in a final post he will consider Koreeda’s Like Father, Like Son, Jia’s A Touch of Sin, Johnnie To’s The Blind Detective, the Godard segment of 3x3D, and Oliveira’s Gebo and the Thief. Like the items I’ve invoked here, each deserves an entry to itself, but time limits and further travels force us to be quick. Still, we hope that you can tell from our entries, VIFF 2013 yielded an extraordinarily high level of quality. As usual!

P.S. 17 October 2013: Thanks to Hamidreza Nassiri for correcting the original entry: Panahi is not, as we had said, under house arrest.

Trapped (2013).

Around the world in a multiplex: First dispatch from Vancouver

Kristin here–

My title exaggerates. There are other venues for the Vancouver International Film Festival besides the Empire Granville multiplex. There is the Pacific Cinematheque, often used for more avant-garde items; the Vancity Theatre, which screens art films and hosts industry events year-round; and the gorgeous old picture palace, the Vogue, a multiple-use venue that hosts both big screenings and gala events. But frequently we find ourselves wandering for a whole day among the Granville’s seven screens, circling the globe cinematically.

The Middle East

Four years ago we blogged about Captain Abu Raed (2007), the first Jordanian feature film in decades. This year there is The Last Friday (2011,  Yahya Alabdallah), and by now the fact of a Jordanian film appearing at festivals is no longer notable. Production has now been systematized. The Last Friday was financed (for around $100,000) by the Royal Film Commission of Jordan’s Educational Feature Film Program.

Yahya Alabdallah), and by now the fact of a Jordanian film appearing at festivals is no longer notable. Production has now been systematized. The Last Friday was financed (for around $100,000) by the Royal Film Commission of Jordan’s Educational Feature Film Program.

The basic plotline is simple, with protagonist Youssef, a handsome, hard-working middle-aged man, divorced and reduced to driving a taxi prone to breakdowns, struggling to earn money for a serious operation. The cinematography was done using a Red One camera, and the resulting images are impressive. (Alabdallah often resorts, with good effect, to what David has termed planimetric compositions, those shot directly toward a flat background.) There is little dialogue, and Youssef’s struggles are conveyed by small details, visual and aural. The fact that he has tampered with his apartment block’s switch boxes to steal electricity is established early on, but by-play with the fuses he has transferred or hidden becomes an unnecessary but entertaining motif.

Perhaps the “educational” part of the film comes from Youssef’s son, a teenage wastrel who hangs out at his father’s apartment. It eventually comes out that he has stopped going to school, and Youssef has the additional burden of confronting his ex-wife to thrash out a method for dealing with their errant son.

The Last Friday treads that risky line so many independent filmmakers on small budgets take, singling out a character with a problem and showing him or her doggedly dealing with it. It takes a sure touch and an interesting character to make this work, and Alabdallah manages both, helped by Ali Suliman’s performance in the lead role.

So far undoubtedly the biggest unexpected gem this year has been the Iranian family melodrama/thriller A Respectable Family (2012). The film is the first fiction feature by documentarist Massoud Bakhshi; it was shown in the Directors’ Fortnight series at Cannes and gained generally favorable reviews.

The plot concerns Arash, a professor who has lived in Paris for decades and, as a guest post at the university in his hometown of Shiraz winds down, seeks in vain for the return of his passport to allow him to return home. At the same time, a lawyer informs him and his mother that a sizable sum of money has been left to them by his estranged, abusive father. The family drama that plays out depends for effect on an extraordinarily complex and tight script with numerous abrupt turns and surprises that keep the audience as busy as in any recent Hollywood thriller. In particular, Bakhshi’s use of switches in point of view and flashbacks to the period of Arash’s youth are masterful.

Here I pass along the same advice I have given friends here at the festival in recommending the film: don’t read reviews or program notes about this film before seeing it. Everything I have read about the film gives away key pieces of information that should be kept secret.

The tone of the film, with its implicit but obvious criticism of the Iran-Iraq war and the regime that fostered it, plus the ending’s evident support for student demonstrators, make it amazing that the film could be made within Iran. It apparently has not been released within its home country and most likely won’t be. Yet the Iranian press reported calmly on its favorable reception at Cannes, as the press there usually does when national films gain prestige abroad. A story in the Teheran Times remarked: “It was a great surprise that non-Iranian filmgoers were able to relate to the Sacred Defense (1980-1988 Iran-Iraq war) and the concept of martyrdom, which are themes of the film, Mohammad Afarideh [the film’s producer] told the Persian service of the Mehr New Agency.” Afarideh added, “The film has an Iranian storyline, but the structure Bakhshi has chosen for the dialogue helps attract foreign audiences as well.”

Many in Iran and elsewhere were also surprised that A Separation could connect with western audiences in the way it did. It’s a pity that A Respectable Family is unlikely to gain such a widespread audience, but it is worth seeking out. It plays once more here in Vancouver, on October 3 at 6:45 pm in the Empire Granville 2.

Latin America

Una noche (2012) is listed in the program as a Cuban/UK/USA co-production. The Cuban contribution comes primarily from the setting and the cast–and the cooperation of the government. (Certainly it makes setting out to try and escape to the USA an unattractive prospect.) It was entirely shot in Havana and environs, and three young first-time actors play the principal roles. The director is Lucy Mulloy, making her feature debut. It is otherwise largely New York based, having been at least partially supported by the Independent Filmmaker project in its “Narrative Independent Filmmaker Lab,” which funds films with budgets of under a million dollars. Post-production seems mainly to have been done at the Tisch School of the Arts at NYU.

Perhaps as a result of such mixed origins, Una noche manages to create a strong, Hollywood-style plot with plenty of local color. The opening shows a blonde tourist in a car, but the heroine’s voice declares that this will not be this girl’s story but her own. Quick but effective characterization sets up the close relationship between twin brother and sister. They’re poor kids from the barrio scratching a living, with Lila working as a dance-hall girl and Elio serving as a cook. Yet we are away from Lila for long stretches, becoming aware, as she is not, that Elio is gay and has a crush a fellow cook. But Raul is an obviously straight young thug, and he has talked Elio into making an attempt to cross to the USA on a raft.

Their preparations, gathering the materials and supplies they need, take us through the poverty-stricken neighborhoods, with Elio’s shiftless friends catcalling at girls and joyriding on their bikes by clinging to buses. Raul visits a dealer to buy medicine for his AIDS-stricken mother, a gaunt former beauty still turning tricks to support herself.

The action escalates as Raul accidentally injures a tourist and Lila discovers that Elio is planning to leave her and go with Raul. Mulloy deliberately downplays the ending, flashing a dedication on the screen to give us the impression that the film is over. Almost as an afterthought mixed in with the beginning of the credits, she presents brief shots showing us of the fates of the characters, filmed from a distance and without Lila’s voiceover. The Variety reviewer found the ending abrupt and “somewhat inadequately foreshadowed,” yet it seemed appropriate to me, and indeed was one of the most original touches in the film.

The North American rights to Una Noche were picked up earlier this year by Sundance Selects after the film proved a hit at the Tribeca Film Festival, winning Best New Narrative Director, Best Cinematography, and Best Actors (shared between its two male leads). Ironically, two of the young lead actors used the Tribeca festival as an occasion to request asylum in the USA.

The Antipodes

There is something comforting about the fact that, after all the success of the Lord of the Rings trilogy and the prospect of a series of Avatar films  being made there into the indefinite future, the New Zealand Film Commission is still funding the same sorts of low-budget genre movies that were made before the country became Middle-earth and Pandora. Robert Sarkies, veteran Kiwi director, has followed up his gripping, headline-based thriller Out of the Blue (20o6) with a return to Scarfies (1999) territory, albeit on a more grotesque level.

being made there into the indefinite future, the New Zealand Film Commission is still funding the same sorts of low-budget genre movies that were made before the country became Middle-earth and Pandora. Robert Sarkies, veteran Kiwi director, has followed up his gripping, headline-based thriller Out of the Blue (20o6) with a return to Scarfies (1999) territory, albeit on a more grotesque level.

Two Little Boys (2012) is based on the old getting-rid-of-an-incriminating-corpse premise, with wimpy Nige (Bret Mackenzie, left) accidentally killing a Scandinavian sports star with his car. Despite a recent quarrel, Deano (Hamish Blake), his best friend from childhood, agrees to help him out and hatches more and more devious and grisly methods for disposing of the body–and later of Nige’s roommate, pudgy, clueless Maori roommate Gav, who adds a touch of sweetness with his persistent obliviousness to the pair’s fiendish doings.

It’s a feather-weight film, but one with many funny moments. It also shows off some parts of New Zealand seldom used in films, starting off in the southernmost and westernmost city, Invercargill, and the bleakly beautiful Catlins, on the southeast coast.

Europe

From the ridiculous to the sublime. Journal de France (2012) presents a sort of professional autobiography of the great French photographer and filmmaker Raymond Depardon. The framing situation is a journey through France that Depardon takes (supposedly alone, though there is someone there to film him), photographing landscapes and villages with his big view camera (bottom). There’s a charmingly chatty scene of him photographing four aged men who had posed for him in the same spot earlier (top).

Interspersed is footage from throughout Depardon’s career. This is presented in voiceover by co-director Claudine Nougaret, the filmmaker’s partner in private life and his long-time sound recordist. Much of this footage didn’t make it into the finished documentaries, including practice shots from when Depardon was learning the trade and amazing footage of many of the major events of the late twentieth century. Depardon travelled widely, often going into war-torn areas of Africa, such as Biafra in the late 1960s. His candid footage of people in the streets of Prague during its invasion by Russian tanks in 1968 is astonishing. Also memorable is a shot of Nelson Mandela quietly sitting in a chair. Depardon asked him to sit for a minute without speaking. Without a watch, Mandela timed it to the second. He learned the trick while in prison.

One comes away with a sense of not just a man with a keen eye and a great deal of patience. Depardon’s bravery and political conscience allowed him to leave behind a legacy of images with an immediacy that brings half-forgotten historical moments to vivid life.

Now I’m off to the Granville again, to see a Japanese film and then a South Korea one. David will blog about these in a future dispatch.