Archive for the 'National cinemas: Hong Kong' Category

Sometimes a swordfight . . .

The Valiant Ones (Zhonglie tu, 1975).

DB here:

. . . makes you sit up. And notice a simple but ingenious cinematic technique.

One of the refrains of this blog is: We want to know filmmakers’ secrets, even the secrets they don’t know they know.

Over my years of studying Hong Kong film, I kept coming back to the work of King Hu (Hu Jingquan), one of the great directors of Chinese cinema. Most famous for A Touch of Zen (1971), Hu made several other striking martial arts films: Come Drink with Me (1966), Dragon Inn (aka Dragon Gate Inn, 1967), The Fate of Lee Khan (1973), and Raining in the Mountain (1979).

Kristin and I have a special fondness for The Valiant Ones (1975), which consists largely of virtuoso combat sequences. Here we find some of Hu’s most spectacular experiments in staging, framing, and cutting action scenes. The story isn’t complicated, but the result lives up to his motto: “If the plots are simple, the stylistic delivery will be even richer.” Unhappily, for reasons of rights, The Valiant Ones is harder to see than his other masterworks.

When I was studying Hu’s work at a European archive, I told the archivist that watching The Valiant Ones I had started to understand his secrets. She smiled and said, “All right, but don’t tell anyone.” Ha! Fat chance. I broke the news in an article and then in Planet Hong Kong. I use our current lockdown to share it more widely.

Suppose you have a character called the Whirlwind Swordsman. He circles his adversary so quickly, ducking and bobbing, shifting front and back, that the target is bewildered. How would you render this quicker-than-the eye tactic on film? Today’s directors think automatically of digital effects. But that wasn’t on the menu in 1975.

Wu Jiayun and his wife are pretending to be interested in joining a pirate gang. In a series of audition bouts, the chief pirate sends his minions to spar with them. Here we see first Wu’s wife take up a monk’s archery challenge. (I include that as bonus material.) It’s a fair sample of the rhythm Hu gets through a combination of editing and figure movement. The audition continues with Wu showing a stout pirate his Whirlwind technique.

Did you see what King Hu did? He used a double for Wu, dressed him in white, and had him rocket into and out of the foreground while the primary Wu dodged in and out of frame in the background. Sometimes Wu leaves one spot and reappears elsewhere only one frame later!

Significantly, Hu set up this cleverly confined framing by means of a simple axial match-on-action. The larger view oriented us to the area clearly.

Giving up his fondness for discontinuous cuts, Hu used this cut to prime us to expect continuity of space as the shot unfolds. The double is in effect inserted in the splice.

Is it merely a trick? All’s fair in cinema. The gliding, percussive force of the frame entrances and exits shows us a preternaturally gifted fighter whose moves are too fast for the naked eye. We have no time to reflect on how it was done.

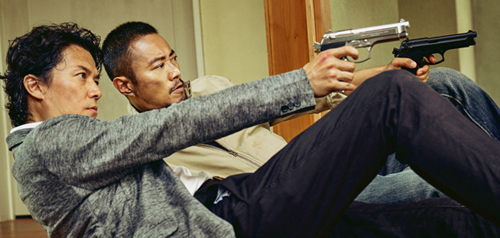

Interestingly, Wu seems to have taught Mrs. Wu his technique. At the climax she gets a chance to practice surrounding a hapless fighter. See my stills up top and at the bottom.

Secrets? You bet. We appreciate them all the more when we work to discover them.

For more on King Hu, see Stephen Teo, Chinese Martial Arts Cinema: The Wuxia Tradition (Edinburgh University Press, 2009). I discuss Hu’s style in more detail in “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse” in Poetics of Cinema, and in “Three Martial Masters” in Planet Hong Kong, 2d. ed.

A Touch of Zen and Dragon Inn are available in fine restorations in the Criterion Collection and on the Criterion Channel. Also on the Channel is Hubert Niogret’s superb biographical film about King Hu.

Some recent entries (here and here) review the ideas of axial cutting and matches on action.

This is the second time I’ve used King Hu in this series; he’s a rich source of startling cinema. For other “Sometimes…” entries, go here.

The Valiant Ones (1975).

Quality bingeing

Mon Oncle (1958)

Kristin here:

Or binging, if you prefer. Either is an acceptable spelling.

Streaming entertainment is one of the things that are saving our sanity as we sit in our homes. With the theaters closed and new movies either delayed or sent straight to streaming, movie critics, other journalists, and movie buffs are now making best-films-to-stream-during-the-pandemic lists a new and common genre across the internet.

Maybe you’ve been streaming a lot of TV series, even ones you’ve already seen, and are feeling a bit guilty about that. Maybe you’re longing for something more worthwhile to watch but wishing that that something would take up more time than your average feature film.

For those people, I offer a list of films to binge. These are either long in themselves or are split up into many parts that can be binged just like TV series. Others are stand-alones but can be grouped in meaningful ways.

My experience is that online disc orders are taking longer than usual. With Amazon prioritizing health and work-at-home supplies, Blu-rays are taking around two weeks rather than two days. (David and I, of course, count Blu-rays and streaming as part of our work-at-home requirements.) While you’re waiting, I’ll bet many of you have some of these discs on your shelves already and have always meant to make time for them. That time, lots of it, has arrived.

Serials

Many fine serials were made in the silent era, but Louis Feuillade remains the director that most of us think of first in relation to this format. His three great serials of the 1910s (not including, alas, the fine Tih Minh [1918]) are available on home video.

Fantômas (1912). 5 episodes, 337 minutes. Fantômas is available in Blu-ray and DVD from Kino Lorber. David wrote a viewer’s guide to it here.

Les Vampires (1915). 10 episodes, 417 minutes. Les Vampires is available on Blu-ray and DVD from Kino Lorber. As far as I can tell, it is streaming only on Kanopy (apart from unwatchable public domain pre-restoration prints).

Judex (1917). 12 episodes, 315 minutes. Judex is ordinarily available from Flicker Alley, though it is currently listed as out of stock. Amazon has 5 left. For maximum bingeing opportunities, watch all three serials in a row and then stretch them out with Georges Franju’s charming remake, Judex (1963) for an extra 98 minutes (it’s $2.99 to stream it on Amazon Prime).

Miss Mend (Boris Barnet, 1926). Three episodes, 235 minutes. The only American-style serial from the Soviet Union that I know of, or at least the only one easily available. I wrote about it briefly when it first came out from Flicker Alley. You can still get it from Flicker Alley or Amazon. We wrote briefly about it here.

Le Maison de mystère (Alexandre Volkoff, 1923). 10 episodes, 383 minutes. I’ve already written in some detail about this long-lost serial. It’s probably not as good as Feuillade’s best, but it’s good fun and beautifully photographed (see top of section) and acted–and long enough to require a meal break. Fans of the great Ivan Mosjoukine (as he spelled his name after emigrating from Russia to France) will especially want to see this one. Available from Flicker Alley

Berlin Alexanderplatz (Rainer Werner Fassbender, 1980) 13 episodes and an epilogue. 15 hours, 31 minutes. Back when it first came out, this was treated more as a film than a TV series. It showed in 16mm at arthouses and archives. David and I drove to Chicago to see the whole thing in batches over a single weekend at The Film Center (now the Gene Siskel Film Center). It’s available on either DVD or Blu-ray as a Criterion Collection set (#411 for you Criterion number-lovers). It’s also streaming on the Channel. Both have a batch of supplements, even the 1931 German film of the novel, so you can stretch the experience out even longer.

Silent serials may work for some families, if the kids have been introduced to silents already through the more obvious route of films with Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and the other great comics of the era. If not, families can fill their time with more recent films in episodes with continuing stories.

The serial format has had a comeback in recent decades, partly due to the influence of the first Star Wars trilogy and partly to the need for ever expanding amounts of moving-image content in the era of home-video, cable, and internet services. For those who want to binge Star Wars, you don’t need my guidance. Anyway, I gave up after the first of the recent series, the one where Adam Driver took over as the villain. (Not that I have anything against Adam Driver. It was the film.) Even daily life in a pandemic is too short for more.

The Harry Potter series. (2001-2011) Eight episodes, 990 minutes, or 16.5 hours. This series is not high art, but it’s pretty good, highly entertaining (to some, at least), and even has one episode, number three, directed by Alfonso Cuarón, HP and the Prisoner of Askaban (above). The others are HP and the Sorcerer’s Stone (or Philosopher’s Stone in the UK and elsewhere; Chris Columbus), HP and the Chamber of Secrets (Chris Columbus), HP and the Goblet of Fire (Mike Newell), HP and the Order of the Phoenix, HP and the Half-Blood Prince, HP and the Deathly Hallows: Part I, and HP and the Deathly Hallows: Part II (the last four, David Yates). These films are, of course, available in multiple versions, on disc and streaming. As far as I can tell, none of the complete boxed sets have the two last parts in 3D; those have to be purchased separately. Having seen the last film in a theater in 3D, I can say that it doesn’t seem to be one of those films that is much improved if one sees it that way (unlike Mad Max: Fury Road, in the section below).

The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings extended editions: An Unexpected Journey (2012), The Desolation of Smaug (2013), The Battle of the Five Armies (2014), The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), The Two Towers (2002), and The Return of the King (2003, above). 6 episodes, 1218 minutes, or 20 hours, 18 min. Yes, for sheer length this serial tops them all. Plus there are lots of supplements. Each part of the Hobbit films has one commentary track and a bunch of making-ofs, adding up to 40 hours, 5 1/2 minutes. This pales, however, in comparison with the LOTR extended editions, which have four commentary tracks, totaling 45 hours, 44 minutes. The making-ofs are hard to get exact figures for, but I estimate about 22 hours for all three films. That’s about 68 hours of audio and visual supplements.

To top that off, the Blu-ray set contains the three feature-length documentaries by Costa Botes: The Fellowship of the Rings: Behind the Scenes, The Two Towers: Behind the Scenes, and The Return of the King: Behind the Scenes, all adding another 5 hours, 2 1/2 minutes. (Botes’s films were also included in a “Limited Edition” reissue of the theatrical versions of the LOTR films in 2006.) In toto, if one watches every single item and listens to all the commentaries, one could escape 133 hours and 10 minutes of isolation boredom–and possibly go mad in the process. But treating the bingeing as an eight-hour-a-day job, it would come to 16 1/2 days.

All this does not include the supplements accompanying the theatrical-version discs. These are charming but more oriented toward introducing complete neophytes to the universe of Middle-earth than toward giving filmmaking information.

Series

Series, as opposed to serials, usually involve continuing characters but self-contained stories. Most of the series below could be watched out of order without suffering much. It would help to watch Mad Max first, since it’s an origin story. The Apu Trilogy should be watched in order because it’s about the central character’s stages of life. Each of the M. Hulot films bears the traces of the contemporary culture in which it is set, but one can understand each fine out of order. I saw Traffic first, in first run, and then saw the others.

Mad Max (1979), Mad Max 2, aka The Road Warrior (1981), Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985), and Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) add up to 411 minutes, or 6 hours and 51 minutes. You know them, you love them–but have you ever watched them straight through? We’ve written about Fury Road (here and here). That’s a film where the 3D really does play an active role.

Jacques Tati’s Monsieur Hulot films: Mr. Hulot’s Holiday (1953), Mon Oncle (1958, see top), Play Time (1967), and Traffic (1971). They add up to 7 hours and 4 minutes. Or add his non-Hulot films, Jour de fête (1949) and Parade (1974) for just under an additional 3 hours of hilarity. You can buy all of Tati’s films at The Criterion Collection or stream them at The Criterion Channel. Throw in my “Observations on Film Art” segment on Parade for an extra 12 minutes. And check out Malcolm Turvey’s new book, Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comedic Modernism, soon to be discussed in a portmanteau books blog here.

Dr. Mabuse films plus Spione: Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (1922), Spione (1928, frame above), The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933) and The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960), adding up to 610 minutes, or 6 hours and 10 minutes. Few if any directors have extended a series over such a stretch of time, and the Mabuse films are quite different from each other (including having different actors play the master criminal). I throw Spione into the mix because the premise and tone are so similar to the first Mabuse film. Haghi is basically Mabuse as a master spy instead of a gambler and general creator of chaos; given that he’s played by Rudolf Klein-Rogge, who was the first Mabuse, the comparison is almost inevitable. One can almost imagine Haghi as just another of Mabuse’s disguises and it fits right into the series. I’ve linked the streaming sources to the titles above.

Kino Lorber has the restored version of Der Spieler on DVD and Blu-ray, Eureka has the restored version of Spione on DVD and Blu-ray (note: Region 2 coding) The Criterion Collection offers a DVD of Testament, and Sinister Cinema has a DVD of The 1,000 Eyes. (For those who want to dig deeper, there a Blu-ray set of all of Lang’s silents, from Kino Classics and based on the F. W. Murnau Stiftung restorations. That totals 1894 minutes, or about 31 and a half hours. I don’t know if that counts the supplements, but there are lots of them.)

Apu Trilogy: Pather Panchali (“Song of the Little Road,” but nobody calls it that, 1955), Aparajito (1956), and The World of Apu (1959). 341 minutes. Satyajit Ray’s trilogy may seem like a serial, in that it follows the life of the main character, Apu. Yet Ray had not planned a sequel until Pather Panchali achieved international success, and the films have big time gaps in between, with no dangling causes. These are three of the most beautiful, touching films ever made, and the stunning restoration from a damaged negative and other materials is little short of a miracle. If you have never seen these or saw them before the restoration, do yourself a favor and binge them. Have some tissues handy, and I don’t mean for stifling coughs and sneezes. Available on disc from The Criterion Collection and streaming on The Criterion Collection here, here, and here.

Now I briefly cede the keyboard to David for his recommendations of Hong Kong series.

Triads vs. cops, Triads vs. Triads

Infernal Affairs (2003).

There are many delightful Hong Kong series. I enjoy the silly Aces Go Places franchise (1982-1989) and the pulse-pounding Once Upon a Time in China saga (1991-1997). Alas, almost none of these installments entries are represented on streaming. I could find only the weakest OUATIC title, Once Upon a Time in China and America (1997) on Amazon Prime, Vudu, and iTunes.

If you want to go for samples, there are two diversions from the ever-lively Fong Sai-yuk series. The Legend (US title of the first entry, a bit pricy from Prime). The more reasonably priced Legend II, the US version of the second entry, has a fantastically funny martial-arts climax featuring Josephine Siao Fong-fong as Jet Li’s mom. This is available from several streamers. Older kids won’t find either one too rough, I think.

There are two outstanding series more suitable for adult bingeing. Infernal Affairs (2003-2004) was made famous by Scorsese’s remake The Departed (2006), but the original is better, and the follow-ups are loopier. The first entry offers solid, suspenseful plotting and meticulous performances by top HK stars Tony Leung Chui-wai and Andy Lau Tak-wah, supported by a rogues’ gallery of unforgettable character actors. Parts two and three spin off variations on the first one, tracing out before-and-after incidents and throwing in some quite strange narrative contortions. The whole thing provides an engrossing five and a half hours of entertainment. Available from several services.

In my book Planet Hong Kong I analyze the trilogy as an example of how directors Andrew Lau and Alan Mak Siu-fai created a more subdued thriller than is usual in their tradition. Bonus material: In the spirit of providing free stuff during the crisis, here in downloadable pdf form is my little chapter on the trilogy: Infernal Affairs interlude.

Also subdued, even subtle, is Johnnie To Kei-fung’s Election (2005) and Election 2 (aka Triad Election, 2006). These films dared to show secret gang rituals that other filmmakers shied away from. The first part plays out ruthless competition among rival Triad leaders, including strikingly unusual methods of punishing one’s adversary. The second entry, even more audacious, suggests that Hong Kong Triad power is intimately tied up with mainland Chinese gangs, backed up by political authority.

Johnnie To’s pictorialism, so feverish in The Longest Nite (1998), A Hero Never Dies (1998), The Mission (1999), and other films, gets a nice workout here as well. Infernal Affairs is agreeably moody, but the Election films are black, black noir.

The pair add up to three hours and a quarter. The first film is apparently available only on disc but the second is streaming from several sources.

Of course, to get into the real Hong Kong at-home experience, some viewers will find all these films easily and cost-free on the Darknet.

Thematic combos

Flicker Alley’s Albatros films. 5 films, 664 minutes, or 11 hours and 4 minutes. I wrote about the DVD set, “French Masterworks: Russian Émigrés in Paris 1923-1929” when it first came out. It’s still available here. The Albatros company made some of the key films of the 1920s, most of which are still too little known, including Ivan Mosjoukine’s Le brasier ardent (1923, above). If this is still a gap in your viewing of French films, here’s a chance to fill it.

Yasujiro Ozu: The Criterion Collection has released a helpful thematic grouping of some of Ozu’s early films. One is “The Silent Ozu: Three Family Comedies” (DVD and streaming), including I Was Born, but …, Tokyo Chorus, and Passing Fancy, adding up to 281 minutes. The British Film Institute has gone further along the same lines, releasing “The Gangster Films,” also three silents: Walk Cheerfully (1930), That Night’s Wife (1930), and the wonderful Dragnet Girl (1933); they add up to 259 minutes. The BFI has also put out “The Student Films,” (listed as out of stock at the moment) yet more silents: Ozu’s earliest complete surviving film, Days of Youth (1929), I Flunked, But … (1930), The Lady and the Beard (1931) , and Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth? (1932), adding up to 251 minutes.

David has recorded an entry on Ozu’s Passing Fancy for our sister series, “Observations on Film Art,” on the Criterion Channel; it should go online there sometime this year.

Or watch all the “season” films in a row: Late Spring (1949), Early Summer (1951), Early Spring ((1956), Equinox Flower (1958), Late Autumn (1960), End of Summer (1961), and An Autumn Afternoon (1962), for a grand total of 840, or 14 hours. Including An Autumn Afternoon is cheating a bit, since the original title means “The Taste of Mackerel.” Still, it’s so much like the earlier films in equating a season with a stage of life that the English title seems perfect. The early films equate the seasons with the young people, about to marry or recently married, while in the later films, and especially the last three, the seasons refer to the older generation, lending an elegiac tone to the end of Ozu’s career. David has done commentary for the DVD of An Autumn Afternoon.

All of these (except for Days of Youth) and many other Ozu films can be streamed on The Criterion Channel, which also has a bunch of supplements on this master director.

Or just watch The Criterion Channel’s Kurosawa films in chronological order, or Bresson’s or Godard’s or Bergman’s or …

Or watch all of Hideo Miyazaki’s films in chronological order, with or without the company of kids.

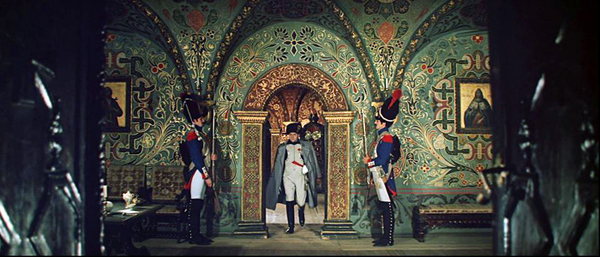

Just really long films

War and Peace (Sergei Bondarchuk, 1965-1967, above) 4 parts: 7 hours, 3 minutes, 44 seconds. I suppose this is technically a serial, since the parts were released over three years. Still, the idea presumably was that it ultimately should be seen as one film, and the running time would permit it being seen in one day fairly easily. I have not seen this restored version, only the considerably cut-down American release back when it first came out. I remember it as being quite conventional, but on a huge scale in terms of design, cinematography, and crowds of extras. Seeing it in its original version would no doubt be impressive (see above). Available on disc at The Criterion Collection and streaming on The Criterion Channel. The supplements total 175 minutes and four seconds, pushing the total up to nearly 10 hours.

Satan’s Tango (Béla Tarr, 1994) 450 minutes, or 7 hours 30 minutes. Film at Lincoln Center has just made Tarr’s epic available for streaming; you can rent it for 72 hours and support a fine institution. As to owning it, the DVDs seem to be out of print. There is, however, a Blu-ray coming from Curzon Artificial Eye on April 27 in the UK. Pre-order it here. Obviously many of us will still be stuck inside by the time it arrives. Or if you have it on the shelf and never quite got around to watching it, here’s your chance. Derek Elley’s Variety review sums up its pleasures. Our local Cinematheque has shown it twice, once in 35mm and more recently on DCP (see here, with the news buried at the bottom of the story). David reported on that first showing, and later he wrote a general entry about Tarr’s work on the occasion of having met the man himself.

Shoah (Claude Lanzmann, 1985) 550 minutes, or 9 hours and 10 minutes. The Holocaust examined through modern interviews with a broad range of people involved. Available in a restored version on disc from The Criterion Collection. It does not seem to be available currently for streaming.

Unclassifiable

Then there’s Dau (2020-), a biopic of a Soviet scientist that is perhaps the most ambitious filmmaking venture ever.

Shot on 35mm over three years in a real working town with 400 characters played by actors who remained in character and costume round the clock the whole time. Few have seen these, though two showed at the Berlin festival this year. We haven’t seen them but plan to give it a go, since they have just shown up online. Here’s a helpful summary of the project. At the Dau Cinema website, you can stream the first two films for $3 each: Dau. Natasha (2:17:53) and Dau. Degeneration, (6:09:06) adding up to 8 hours and 27 minutes. Twelve more films are announced for future release, with no timings given. Clearly not suitable for family viewing.

I have not attempted to add up all these timings, but if you can track most of them down, they might get you through much of the isolation period. Stay safe!

Election (2005).

What a difference a day makes: CHUNGKING EXPRESS comes to the Criterion Channel

Chungking Express (1994).

DB here:

Chungking Express is nearly twenty-five years old, and it remains as jittery and sparkling as it was in 1994. I saw it on laserdisc in the fall of that year and immediately cottoned to it–more keenly than to its mate, Ashes of Time (which I came to admire eventually). I saw it on the screen in spring of 1995 during my first visit to the Hong Kong International Film Festival. (It’s unspooling, as Variety would say, as we speak, although I’m not there dammit.) That was also when I met Wong Kar-wai for the first and only time. I was asked to present him the Hong Kong Film Critics Society award for Ashes of Time. During the same visit, I was at the Hong Kong Film Awards when Chungking Express won for best picture, best director, best actor (Tony Leung Chiu-wai), and best editing (William Chang Che-wi).

The trip was a turning point in my life. Thanks to that visit and later ones, I met Li Cheuk-to, Ho Wai-ling, Jacob Wong, Stephen Teo, Athena Tsui, Law Kar, Bede Chang, Shu Kei, Michael Campi, Ross Chen, Yvonne Teh (of Webs of Significance), Chuck Stephens, Stefan Hammond, Grace Ng, Shelley Kraicer, Lau Sing-hon, Joanna Lee, Ken Smith, Lisa from Toronto, Ding Yuin Shan, To Kei-chi, Yau Nai-hoi, Johnnie To, Sam Ho, Fu Poshek, Peter Chan, Ann Hui, Dora Mak (from UW), Bérénice Reynaud, Wong Ain-ling, Frederic Ambroisine, King Wei-chu, Chris Berry, Bob Davis, and many more people who became good friends. In later visits I got back in touch with old friends turned expats–Patricia Erens, Mike and Melissa Curtin, Darrell Davis, Yueh Yu-yeh, Nat Olson (from UW, of Hong Kong Hustle), Mette Hjort, Paisley Livingston–and longer-term comrades like Tony Rayns, Mike Walsh, Gary Bettinson, and Peter Rist. The Fragrant Harbour, a crossroads of Chinese culture, became a central node in the only social network that matters to me: the non-virtual one. Not Facebook but Face-to-Face.

I think of Hong Kong often; I regret not being able to attend the festival in recent years; and I’m saddened when I reflect that Ain-ling and Wai-ling are no longer with us. Twenty-four years went by too fast.

Chungking Express was made during a gap in the filming of Ashes and proved that for once Wong could turn out a quickie. Andrew Lau started as cinematographer for the first story, but when he left to make his own film, Chris Doyle picked it up. Both made good use of that loose “free camera” style that now seems to be everywhere. I usually find it annoying, but here the ambiance and the players and the sheer look of the city win me over. There’s also some peekaboo slit-staging.

The movie benefits from an ingratiating and eclectic score, drowsy voice-overs, and people who like to eat and talk about romance.

Chungking Express typifies everything that I love about Hong Kong and its people and its cinema. When I see that jet and that clothesline, I remember looking out the window of such a plane and wondering about the people I saw on the rooftops, scarily close. Staying at the Salisbury YMCA, I was a short walk from the Bottoms Up bar and Chungking Mansions. And when I finally stopped by the Midnight Express and realized that the California Café was just across the street, I realized how tricky Wong had been with cinematic geography. (I didn’t get to the Midlevels escalator until later.) Chungking Express captures the careenng energy of this city, while warming it with a preposterous lyricism. Faye treats her salad squirters like marimbas, and those guys have to be the least tough cops in the territory.

Chungking Express typifies everything that I love about Hong Kong and its people and its cinema. When I see that jet and that clothesline, I remember looking out the window of such a plane and wondering about the people I saw on the rooftops, scarily close. Staying at the Salisbury YMCA, I was a short walk from the Bottoms Up bar and Chungking Mansions. And when I finally stopped by the Midnight Express and realized that the California Café was just across the street, I realized how tricky Wong had been with cinematic geography. (I didn’t get to the Midlevels escalator until later.) Chungking Express captures the careenng energy of this city, while warming it with a preposterous lyricism. Faye treats her salad squirters like marimbas, and those guys have to be the least tough cops in the territory.

I wound up talking about the film a lot. I taught it in courses and lectured on it elsewhere. It got a chapter in Planet Hong Kong and an analysis in Film Art: An Introduction.

Now it’s the subject of an installment on our Criterion Channel series on FilmStruck. There I try to show how its narrative construction welds together bits that might otherwise seem disconnected. Seeing it a couple more times to prepare that commentary, I found still more to admire. In the Mood for Love is totally fine, and I’m a big fan of As Tears Go By and The Grandmaster, but Chungking Express is the one I’ll watch any time, any place, anywhere. I like pineapple. I like bittersweet chocolate too.

Later this semester I get to meet a class to talk with them about this charming movie. For 75 minutes, I’ll once more be in touch with a city, only partly imaginary, that for all its harsh edges is filled with flirtations, dead-end love affairs, good humor, and expired canned goods.

I hope you like it too. If you haven’t seen it, what are you waiting for? You can play a clip from the installment on the Criterion website. With the original DVD release now out of print and pricey, FilmStruck is your best chance to see it on video.

Thanks as ever to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, and Grant Delin of Criterion for the fun of making this installment. Our entire Criterion series is here.

For more on Hong Kong film, check this tag.

P.S. 28 March 2018: Midnight Express had a makeover after the film made it famous, as you see below, but it’s now a 7-11. Nate Olson’s Hong Kong Hustle site shows the result. Thanks to Miklos Kiss and Dan Balogh for updating us.

Venice 2017: Crimes, no misdemeanors

Outrage Coda (2017).

DB here:

The period from 1985-1995 was a sterling era for world cinema. Whatever you think of Hollywood of that time (it wasn’t as bad as they say), American independent film was flourishing then. On the global stage, things were even better, as witness the rising careers of Hou Hsiao-hsien, Edward Yang Dechang, Jackie Chan, Tsui Hark, Abbas Kiarostami, and Wong Kar-wai. It was exhilarating to watch these and other directors turn out splendid work like City of Sadness, A Brighter Summer Day, Police Story, Project A Part II, Peking Opera Blues, Once Upon a Time in China, The Blade, Where Is the Friend’s Home?, Through the Olive Trees, Days of Being Wild, Chungking Express, and more.

That’s not all. In Hong Kong, John Woo was redefining the urban action film with the flamboyant, romantic A Better Tomorrow (1986), The Killer (1989), and Hard-Boiled (1992). In Japan, a standup comedian known as “Beat” Takeshi Kitano took over the helming of a crime thriller, Violent Cop (1989), and decided to continue directing, turning out not only the bored-hitman saga Sonatine (1993) but also the lyrical A Scene at the Sea (1991). Another Japanese filmmaker, Kore-eda Hirokazu, launched his career with the meditative, Hou-ish Maborosi (1995).

I loved these films, and still do. Woo and Kitano belong to an older generation (mine, actually), while Kore-eda is younger. None has gone away. All came to Venice 74 with murder on their minds.

Confessed, but to what?

The Third Murder (2017).

The Third Murder (Sandome no satsujin) is Kore-eda’s first venture into the crime genre, and he brings to it the same steady humanism we find in all his work. I’ve elsewhere recorded my uneasiness with his current visual style. Unlike the grave, long-take Maborosi, his films of the last decade or so are pictorially conventional, even academic, with their big close-ups, needlessly sidling camera moves, and other features of intensified continuity. But he continues to take narrative risks, and his almost Renoirian willingness to see many moral and psychological points of view make every film fairly gripping.

The Third Murder begins abruptly. An unseen victim is bludgeoned and the body is burned. The killer is the man we’ll come to know as Misumi. He’s captured. Like 99% of people charged with crimes in Japan, he readily confesses. His lawyers face only the question of sentencing: Should they try to get him life imprisonment rather than execution? When one attorney, Shigemori, decides to investigate more closely, he peels back layers of uncertainty about the circumstances, the victim, and the motive(s). Like many a victim in crime fiction, this businessman needed killing.

Following conventions of the investigative procedural, the plot relies on secrets, viewpoint shifts that drop hints, twists that frustrate simple understanding, and flashbacks that make us question what we thought we knew. Shooting in anamorphic widescreen, Kore-eda produces some extreme framings reminiscent of Kurosawa’s High and Low, one of the films he studied while preparing the project. Despite occasionally flashy moments, it’s a soberly told tale, emphasizing characterization and social critique. By the end, Misumi acquires a weary, radiant dignity, while entrepreneurial capitalism and the justice system are revealed as compromised. (In this respect it recalls I Just Didn’t Do It, 2007, by another 80s-90s director, Suo Masayuki.) In moving to the sordid terrain of the crime story, The Third Murder shows that Kore-eda hasn’t given up his sympathetic probing of human nature and his praise for un-grandiose self-sacrifice.

Bullets to the head and elsewhere

Manhunt (2017).

Sober and un-grandiose don’t apply to Manhunt (Zhuibu), John Woo’s return to bloody brotherhood and outsize ordnance. After prestige Hollywood efforts like Windtalkers (2002), the nationalistic costume picture Red Cliff (2008-2009), and the ensemble-disaster movie The Crossing (2014-2015), Woo is back with what he does best: showing many people firing many guns, dodging bullets (bad guys have bad aim), diving for cover in slow-motion, floating through hazes of cordite, and instantly recovering from wounds that would finish off you and me. These characters also run endlessly, hop into the path of trains, overturn vehicles, and set loose unconscionable numbers of pigeons.

1990s Hong Kong directors could make cheap pictures look expensive; given bigger budgets, they made expensive pictures look cheap. Here that cheapness shows most in some video-generated shots that recall the bad old days of edge enhancement. But who has time to study such problems when you’re smacked by a fusillade of 3000-plus shots in 105 minutes? Resistance is futile, and the pace doesn’t relent. When the fights and pursuits pause, the dialogue scenes flash by in a flurry of cuts and unfortunate lapses into English. (Much of the soundtrack recalls the eerily dubbed voices on US videos of The Killer.)

You’ve got no time to worry much about all this after an opening that drops us straight into an ambush. Ultra-cool Du Qiu drifts into a bar and quotes yakuza movies before leaving the hostesses to slaughter the gangsters dining there. It does get your attention, and it encourages you to sit through the exposition showing Du as the trusted lawyer for a corrupt pharmaceutical company. He proceeds to be framed for murder and goes on the run. Meanwhile stalwart detective Yamura, charged with bringing Du in, begins to suspect that there’s a bigger scheme afoot. Of course he is right.

This is all completely preposterous and continually enjoyable, with constantly startling action choreography and an overheated soundtrack that at one point breaks into Turandot. Here those damn pigeons don’t just soar into the sky; thanks to CGI, they flap annoyingly into the middle of fight scenes, spoiling a punch or a gunman’s aim. We have, besides our twinned heroes, one corrupt cop, one psychopathic son, one fairly mad scientist, two expert hitwomen (one played by Woo’s daughter), a fleet of black-suited motorcycle assassins, and two docile women who acquire some non-negligible lethality. In the press conference, Woo emphasized his eagerness to create women warriors, and he hasn’t stinted. There are hallucinatory images of a bloody wedding dress to enhance the feminine mystique.

Manhunt is a kind of palimpsest of Asian action movies. It’s a remake of a 1978 Takakura Ken movie released to great popularity in China during the 1980s. Woo, in Hong Kong, had already succumbed to that actor’s spell. What Alain Delon was to The Killer, Takakura is to this, and the steelly self-possession of Zhang Hanyu gives the film a solemnity amid all the flamboyance.

Woo has turned the Japanese original into a real Hong Kong movie, vintage 1992. It lacks the mournful homoeroticism of his prime-period work; these two men don’t gaze moistly at each other, but fire quips and complaints in the Lethal Weapon manner. (The bonding is strongest between the duo of female killers.) Still, it’s very welcome, with its proudly retro air and fanboy in-jokes. It earns the right to begin with a reference to a Japanese classic and conclude with a wink to A Better Tomorrow, as if that movie were the next link in a grand tradition. “Old movies always end this way,” says one of the survivors of the carnage. I wish more new movies did the same.

Hitmen in cars getting shot

Outrage Coda (2017).

Compared to Woo, Kitano is brutally laconic. In Outrage Coda, except for one Wooish slow-mo massacre, violence is brusque, shocking, and over fast. In a film full of bland pans following yakuza cars here and there, the end of one panning movement bursts into shooting before you realize it’s happening, and it ends just as suddenly. Kitano likes his confrontations, for sure, and sometimes there’s a buildup, but mostly the blood just erupts, punctuating long scenes of gangster intrigue.

Here that intrigue involves three rival gangs, each with bosses capable of remarkable lip contortions: the Hanabishi yakuza family, its once-powerful subsidiary the Sanno group, and a gang of fixers operating in Japan and Korea under the auspices of boss Chang. Add in two cops, one ready to knuckle to corrupt superiors, the other raging against them, and you have the world through which Otomo (Kitano) and his sidekick Ichikawa move. Normal life, as it’s commonly known, has no place here.

The action bristles with schemes, shifting alliances, double-crosses, faked deaths, and power grabs.”Your methods,” remarks one boss to a co-conspirator, “are increasingly more intricate.” Remarkably, after an introduction humiliating the not-so-bright Hanaba during a sexcapade, Otomo isn’t seen that much. Two-thirds of the running time are devoted to the machinations of the gangs and the cops. Otomo and Ichikawa swing into action rather late, their task being to chop through the knots of plot and counterplot.

The opening few minutes spread out the key motifs. A fishing scene displaying Kitano’s characteristic love for boyish pastimes is interrupted by the discovery of a pistol. The credits sequence announces the importance of cars with gorgeous shots of Otomo being driven through neon-lit streets, his ride seen from straight down as lights play over it. Throughout, deals are struck or broken in cars, and one memorable execution makes creative use of a Toyota. Even that banal filler, shots of cars pulling up and disgorging their riders, gets played for variations: distant thunder when bosses arrive for a conference, abstract configurations when rival forces meet on a rooftop.

During the 1990s Kitano was one of those directors working with what I’ve called planimetric staging and compass-point editing. (Wes Anderson, Terence Davies, and others worked the same territory.) Characters face the camera in medium shot, and shots change along the lens axis or at 90 degrees to it. It’s as if we were in between the characters. When I asked Kitano about the technique back then, he claimed that it was his effort at realism, capturing how people faced one another in conversation. He added that he didn’t know how to direct a scene, and this was the easiest way.

I thought that his images’ paper-doll simplicity suggested a naivete suited to Kitano’s childish hitmen. Moreover, this rigorous, geometrical technique takes on special impact when presenting mobster shootouts. Instead of ducking for cover as Woo’s heroes do, Kitano’s stand up and keep blasting, firing straight out at the viewer in tit-for-tate exchanges. His unflinching framing, refusing Woo’s camera arabesques, gives these encounters a ceremonial gravity, turning them into rituals of professional righteousness. Last man standing, indeed.

The face-to-face shootouts in Outrage Coda adhere to this style, and early in the film so do the conversations. Here is Otomo discovering Hanada in his masochistic rig.

But for many dialogue scenes Kitano has gone with more orthodox staging and shooting. We get over-the-shoulder shots for conversation, tight close-ups to emphasize character reactions, and even that commonplace of modern cinematography, the arcing movement around a speaker to pick up a listener in the background. These choices allow Kitano to expose the ripe performances of the two conspiratorial dons Nishino (Nishida Toshiyuki) and Nakata (Shiomi Sansei); their leathery skin, slip-sliding jaws, and shouted outbursts gain a lot from this treatment. Not that I’m really complaining. In a slightly longer film than Manhunt, Kitano gives us around 700 shots, less than a quarter of Woo’s outlay. Each image carries a lot of weight.

Outrage Coda concludes a trilogy, and at the press conference Kitano said that he conceived this and Outrage Beyond (2012) as one continuous phase of the story. He wanted the series to finish. The ending of this installment will fuel much speculation about his next move, and he hinted that he might adapt a forthcoming novel, one that’s a love story. He’s done one before in A Scene at the Sea, and arguably in Kikujiro (1999). His fans, who mobbed him at the panel, are certainly ready for whatever he comes up with.

Thanks as ever to all those at the Venice Film Festival who made our stay so enjoyable. Special thanks to Peter Cowie, Alberto Barbera, Michela Nazzarin, Jasna Zoranovich, and our colleagues at the Biennale College Cinema endeavor.

For more on John Woo’s style of action cinema, see my book Planet Hong Kong. I discuss planimetric staging and compass-point editing in On the History of Film Style and several blog entries, notably the persistently popular Shot-consciousness (which has side notes on Kitano) as well as entries on Wes Anderson.

John Woo and Kitano Takeshi satisfy their fans.