Archive for the 'Hollywood: The business' Category

The classical Hollywood whatzis

Black Panther.

DB here:

In the academic world, there are conferences and conventions. Conventions tend to be humongous jamborees associated with professional groups like the Modern Language Association and the American Historical Association. They feature panels, workshops, plenary events, book displays, hundreds of papers, and meetings of subgroups–boards, caucuses, and the like. Also sexual liaisons, I’m told. If you want to feel like you belong to a corporation, go to a convention.

Conferences tend to be smaller and focused on single topics. Sometimes speakers are solicited through a call for papers, and sometimes the speakers are invited (the result might be called symposia). I think conferences are more exciting, liaisons aside. Some of the best experiences of my life have been get-togethers like “Imagination and the Adapted Mind: The Prehistory and Future of Poetry, Fiction, and Related Arts” (1999, University of California–Santa Barbara).

Last month, Kat Spring and Philippa Gates of Wilfred Laurier University added another to my list of favorite conferences. “Classical Hollywood Studies in the 21st Century,” which I announced in the run-up to it, was a wonderful gathering of scholars working on American studio cinema from a variety of angles.

Waterloo mon amour

Scott Higgins talks Minnelli.

We heard about production, distribution, marketing and publicity practices, censorship, and fandoms. Mark Glancy analyzed the trade-paper and fan-mag positioning of the Cary Grant/ Randolph Scott household (♥ + ♥?), while Will Scheibel studied discourse around the sad fate of Gene Tierney. Through both close analysis and probing of primary documents, several papers treated racial and gender representation: Charlene Regester on Double Indemnity, Philippa on portrayals of Chinatown, Barry Grant on race in science fiction, Ryan Jay Friedman on African American musical numbers. There was consideration of style and narrative as well, as in Chris Cagle’s case for distinguishing baroque and mannered styles within “1940s Hollywood formalism” and in Stefan Brandt’s tracing of thematic affinities between Finding Dory and The Grapes of Wrath.

I was glad to see the industry and its affiliated institutions get so much attention. Paul Monticone proposed a cultural approach to the MPPDA, while Tom Schatz traced industry developments in the New Hollywood and after. At the level of reception, Peter Decherney traced how digital tools can measure fan engagement with Star Wars. And John Belton, pioneer of detailed technological history, shared a Bazinian take on digital cinema.

Little-appreciated creative workers got to share the spotlight, in Helen Hanson’s paper on Lela Simone (music supervisor for the Freed unit) and Cristina Lane’s study of the career of Joan Harrison, Hitchcock’s “work wife.” Kay Kalinak revealed how composers swiped from themselves, as Tiomkin did in his score for The Big Sky. And there were lots of surprises, as with Shelley Stamp’s revelation of how film noir was sold to female audiences, Adrienne McLean’s account of stars’ running, or at least signing, advice columns, and Kirsten Moana Thompson’s dissection of the unique paint mixtures used in Disney animation.

It wasn’t musty, either. Things were light and friendly, with serious topics treated without pomp. Blair Davis’s obsessive search for science-fiction elements in serials and B films of the 1930s and 1940s, Steven Cohan’s zesty admiration for the “backstudio” picture, Kyle Edwards taking Torchy Blaine (and her budgets) straight, Dan Goldmark’s affectionate dissection of Pixar’s use of memory, and Liz Clarke’s enthusiasm for heroines of World War I films–all showed that classical filmmaking can be studied with both admiration and rigor. Not to mention Richard Maltby’s patented wry wit. (“David, you know I’ve always been a vulgar Marxist.”)

I have to signal my pride in witnessing how many of the participants were affiliated with our program. Tino Balio on MGM, Scott Higgins on Minnelli’s staging, Lisa Dombrowski on late Altman, Charlie Keil (with Denise McKenna) on Hollywood as a “social cluster,” Eric Hoyt (doyen of Lantern) on trade papers, Mary Huelsbeck on archival resources, Vince Bohlinger on US censorship of Soviet films, Maria Belodubrovskaya on Stalinist movie plots, Brad Schauer on Universal’s acting school, Kat Spring on how the trade papers conceived the musical, Patrick Keating on using the video-essay form to analyze lighting–all showed how you can pack a lot of ideas and information into 18 minutes. I was elated to see the learning and energy these several generations of Wisconsinites displayed.

The authors of The Classical Hollywood Cinema got in their licks. Janet Staiger talked about current screenwriting practices, highlighting the role of gatekeepers (agents, script analysts) and the need for vivid writing that can indulge in flourishes–“movies on the page.” Kristin drew on her Frodo Franchise project to show the problems, but also the advantages, of researching an event while it’s happening.

As for me, I got to give the keynote lecture. It was an intimidating situation, but it did allow me to make the case for analyzing films in relation to norms. Since the conference, I’ve thought more about the idea of Hollywood “classicism” and how we might analyze changes in it.

Not exactly classical, but sweet

Janet Staiger and Kristin Thompson, on a research trip to Washington DC 1979.

Now, some thirty-three years since we wrote The Classical Hollywood Cinema, we all know a lot more. There’s scarcely a paragraph of my chapters I wouldn’t change, and much of the research I and others have done since would correct, nuance, and deepen their claims. (I think Janet’s and Kristin’s contributions survive better than mine.)

What did we three do? I’d say we sought to provide a comprehensive description and explanation of narrative and cinematic techniques in the studio years. We traced ties between craft conditions and production decisions on the one hand and the resulting film on the other. We argued that studio division of labor allowed not only reliable production but a standard menu of artistic options. Going beyond the individual filmmaker, we traced how adjacent institutions–not just the studio but professional associations, supply firms, trade papers, and the like–worked to define and maintain the style. We also suggested reading the professional literature rhetorically, seeing industry discourse as a way for individuals and organizations to set agendas and crystallize preferred solutions to problems. We tried to show how technological innovations like color and widescreen cinema took particular turns because of this matrix of activities. And we began the project of treating Hollywood filmmaking as a flexible but bounded set of norms of style and story.

What did we three do? I’d say we sought to provide a comprehensive description and explanation of narrative and cinematic techniques in the studio years. We traced ties between craft conditions and production decisions on the one hand and the resulting film on the other. We argued that studio division of labor allowed not only reliable production but a standard menu of artistic options. Going beyond the individual filmmaker, we traced how adjacent institutions–not just the studio but professional associations, supply firms, trade papers, and the like–worked to define and maintain the style. We also suggested reading the professional literature rhetorically, seeing industry discourse as a way for individuals and organizations to set agendas and crystallize preferred solutions to problems. We tried to show how technological innovations like color and widescreen cinema took particular turns because of this matrix of activities. And we began the project of treating Hollywood filmmaking as a flexible but bounded set of norms of style and story.

The book received both praise and criticism. With the passage of time some issues have become clearer, and some critiques have, as far as I can tell, lost some force. For instance:

The term. Why call it “classical”? Humanists love to debate terminology. But we pointed out in the book that we inherited the term from French commentators, as far back as the 1920s, and from more recent academic circles. Nothing hangs on the name, actually. We could call it “standard” style or “mainstream” style or X style, and the descriptive claims we make about it will hold good. As I indicate in the book, the “classical” label suggests an effort toward coherent, unified storytelling–at least in comparison with the more episodic narratives we find in other traditions. (In Planet Hong Kong I reflect on more episodic approaches.)

The focus on production. Why not talk about distribution, exhibition, or reception? (A) It would require a much bigger book. (B) Production and its affiliated institutions are the most pertinent and proximate causal factors in shaping the films as we have them. (C) It’s not clear that conditions further along the chain have many consequences for the way the movies behave. (D) You can’t talk about everything. (E) All of the above.

The term, again. By calling Hollywood storytelling and style “classical,” don’t you ignore its ties to modern culture? This view, advanced most fully by Miriam Hansen, suggests that the causal factors we trace aren’t broad enough; we don’t consider the rise of urban culture and its associated patterns of behavior and experience. The modern city purportedly alters people’s perception and rhythms of life, and these shape the way films are made. Hollywood’s aesthetic is better conceived as “vernacular modernism.” I’ve responded to this line of argument in On the History of Film Style, where I argue that the position has an equivocal conception of urban experience and how perception works. Moreover, these critics haven’t shown how the cultural forces they invoke have shaped the narrative strategies and fine-grained stylistic features we analyze. The urban experience would have to have a sort of feedback effect on the filmmakers (given the proximity of production, as above). What’s the causal story to be told here? There’s also a problem of delayed timing: the modern city, choked with traffic and distracting displays, antedates the 1910s, when the Hollywood style crystallizes. On the whole, the modernity position seems to me to rely on analogies, not causation.

A rage for disorder. How unified are these films, really? Critics sometimes point to musicals, action movies, noirs, comedies, and other films that seem narratively disjointed. We argued that classical construction was a goal, not always achieved, but even genres that seemed to favor loose plotting put their films together fairly tightly. In addition, principles of both surface structure (dialogue hooks, continuity cutting) and plot structure (goal orientation, deadlines, appointments, etc.) bind the action in most feature-length pictures. In more recent years, analyses by Kristin in Storytelling in the New Hollywood and by me in The Way Hollywood Tells It and Reinventing Hollywood, along with some entries on this site, have, I think, convinced people just how carefully sculpted a classical film can be. Fights, chases, and escapes aren’t mere spectacle; they advance the story by creating new obstacles or revealing betrayals or killing off the hero’s best friend. I have, though, come to accept coincidence as being more important than screenwriting gurus have claimed. Yet even here, coincidence is absorbed into a pattern of cause-and-effect and motivation that isn’t willy-nilly. In short: Where you find planting and foreshadowing, you’ll find “classical” unity.

The neglect of auteurs. Why treat the output of hacks and mediocrities as on the same level as the work of the great filmmakers? Andrew Sarris promoted the idea of writing American film history as the accretion of the “personal visions” of directors. And historians of other arts routinely conceived of history as a succession of exemplary works produced by exceptional creators. But we were asking different questions. We sought to understand a tradition as a whole, and to explain its emergence and longevity. That’s an effort of value in its own right. Moreover, an auteurist could benefit from knowing relevant norms, because then one could pinpoint the distinctiveness of individual filmmakers. Throughout his work, Sarris occasionally signaled when a director made an uncommon choice of camera setup or cutting, and this gesture presupposes a norm in the background.

The schlock of the new. By stopping your survey in 1960, don’t you assume that a post-classical cinema came next–one less concerned with goal-directed plots and “invisible” style? We argued that the industrial conditions for the studios faltered around 1960, but the creative and labor practices (division of labor, hierarchy of control, etc.) continued into the present. We thought that classically constructed films dominated output afterward (Jaws, The Godfather, The Exorcist). Not that there aren’t changes. We suggested that many of the changes detectable in the more unusual “New Hollywood” films of the 197os are traceable to the influence of European art cinema; those principles of construction were blended with genres and stylistic patterns characteristic of the studio tradition. (Since then, other researchers have found this to be the case.) In addition, there are many post-1960 films which are “hyperclassical.” Back to the Future, Jerry Maguire, Die Hard, Hannah and Her Sisters, and others are “more classical than they have to be,” with intricate patterns of motifs and plotting–packed, we might say, with classical features. The same goes for many films we’ve discussed in our blog entries since 2006.

The monolith (no, not 2001). So the classical style never changes, is always in force, can’t go away? Ridiculously monolithic! Actually, we argued that classical filmmaking does change, but within boundaries. I invoked Leonard Meyer’s notion of “trended change,” in which

change takes place within a limiting set of preconditions, but the potential inherent in the established relationships may be realized in a number of different ways and the order of the realization may be variable. Change is successive and gradual, but not necessarily sequential; and its rate and extent are variable, depending more upon external circumstances than upon internal preconditions.

This seems to me to capture change in the studio tradition. Hollywood films can have 400 or 2000 shots, they can be told chronologically or not, they can have single protagonists or multiple protagonists, and there will be a lot of variety at any moment. But they will still tend to obey canons of classical staging, camerawork, cutting, sound work, and dramaturgy. And those changes are, as Meyer suggests, not generated from within the style, as a necessary unfolding like the growth of an organism. The variations are created by external circumstances such as budget constraints, production trends, influential models, new tools, fashion, competition among filmmakers, and the like. I’d make the analogy to the well-made play, which has survived as a model of plotting for nearly two centuries, but has allowed for a huge variety of manifestations, from Ibsen to Doubt and beyond. Perhaps perspective painting and Western tonal music, both robust traditions, would also exhibit trended change within history.

In the book, I tried to analyze levels of change by a three-tier model that still seems valid, though perhaps too abstract. Coming back from Waterloo, I began to see a way to specify a little more the kinds of change we can track, at least in terms of narrative construction. Maybe this effort will also help us understand why we think the “classical” system changes more than it does.

Black Panther in three dimensions

Narrative theorists often distinguish between “story” and “discourse.” There’s the causal-chronological string of events, and there’s the way they’re presented in the text we have. There are other terms for the distinction (story/plot, fabula/syuzhet), and they aren’t completely congruent. In an essay reprinted here I propose that we can better think of narratives as having three dimensions: the story world, the structure of the plot, and the narration.

Start with narration. Why? Because it’s the flow of information we encounter moment by moment, given to us through all the resources of the medium. Black Panther begins with a visual representation of how vibranium created the nation of Wakanda, while we hear on the soundtrack a father recounting the tale to his son. (Here the film’s narration is given as both pictorial and voice-over.)

In an earlier version of this entry, I said that it was T’Chaka speaking to T’Challa. But Fiona Pleasance wrote to point out that the voice is actually that of T’Chaka’s brother N’Jobu telling his son N’Jadaka, who will grow up to be Killmonger. They’re living in exile, which motivates the need to rehearse the nation’s origins.

The narration isn’t only giving exposition about Wakanda’s history. It’s establishing a hierarchy of knowledge, in which the father is presented as knowing more than his son. This is important for a later revelation of what aspects of the past are suppressed. And flashbacks and other narrational choices will further channel the flow of information. Soon after the prologue, we jump back to 1992, when T’Chaka learned of N’Jobu’s affiliation with arms dealer Klaue.

With or without voice-over, the regulated flow of story information will continue throughout the movie. Out of this narration we build a story world. We’re cued to construct characters, to register their roles and attitudes and feelings, to sense their hopes and fears. We also construct the story’s physical world, with its geography and furnishings and rules. Very quickly, for instance, we understand that Wakanda is a land of utopian technology but ruled by ancient tribal lore and rites. Through redundant information we learn of T’Challa’s family and friends, past conflicts among characters, and the threats to Wakanda.

Okay, so we have narration that coaxes us into co-creating a story world. What’s left for my third dimension, plot structure? Kristin convinced me that it’s another level of construction, one that organizes the story world into a comprehensible pattern that can in turn be transmitted via narration. She argues that classical films often have four large-scale parts (not three acts), each typically running about half an hour. Those parts focus the action in the story world around the characters’ goals.

In the Setup, running about half an hour, we meet the main characters and learn their goals. In the Complicating Action, another half hour more or less, the goals get redefined as a result of new obstacles. Then comes the Development, which is largely a holding pattern. Here we get backstory, character portrayal, fantasies and flashbacks, the upgrading of secondary characters, and elaboration of motifs. At the end of the Development, a crisis develops; at this point we know nearly everything we need to know and can concentrate on the outcome. Now comes the Climax, usually with a deadline pressing on the action. At the end, with the action largely resolved, there’s an epilogue (or “tag”) that celebrates the final state of things.

This anatomy of plot structure echoes the classic screenplay manuals up to a point. The Setup corresponds to Act I, the Climax to Act III. The Complicating Action and the Development in effect split the second act. But Kristin’s layout is more precise, I think, because she shows that goals and obstacles change between the first and second part. She also points up the more or less arbitrary delays and detours that prolong the action in her third part, the Development. This “desert of the Second Act,” as screenwriters call it, can now be seen as doing its own distinctive narrative work, not least prolonging suspense.

This structure didn’t have to have such sharply defined segments. Why can’t the setup be an hour, dawdling over introducing the protagonist’s goals? Why not cut out the Development, if it’s mostly delay? The Hollywood tradition has created this distinctive, tight form as one solution to the problem of organizing an appealing narrative at feature length.

Take Black Panther again. The Setup charges T’Challa, newly made king, with responding to Klaue’s theft of a precious Wakandian tool made of vibranium. (Screenplay gurus sometimes call this the “inciting incident.”) At the 35-minute mark T’Challa, Okole, and Nakia set out on a mission to retrieve the artifact. At sixty-one minutes, the midpoint, the goals need revising. Klaue is dead, the Wakandans’ ally Ross is severely wounded, and the real antagonist is revealed: the fierce fighter Erik, aka Killmonger.

The Development provides important backstory involving T’Challa’s uncle’s child N’Jadaka (more flashbacks, including replays of the 1992 scene presented in the Setup–revealing the child Erik as on the scene). T’Challa’s allies flee from Killmonger, who prepares to use the precious vibranium to make weapons for world insurrection. T’Challa, near death, has been rescued by his rival the Jabari chieftain Baku. All pretty typical Development, moving the hero toward his “darkest moment” and facing him with a deadline.

The Climax, which tends to be the shortest section in most films, starts at about 99:00. It’s a gigantic battle scene, involving air combat, ground fighting, and the confrontation of T’Challa and Killmonger–all crosscut for maximum suspense. After the resolution, we get a tag showing a montage of life returning to normal, T’Challa kissing Nakia, and another visit to the 1992 world when T’Challa comes calling in a space ship.

The film has the characteristic double plotline, a romance line of action (will T’Challa and Nakia reunite?) and one centering on a project (keeping vibranium out of the wrong hands). Major developments are carefully foreshadowed. The paternal voice-over establishes the Jabari tribe’s isolation, and Baku’s crucial role is planted when he challenges T’Challa to mortal combat. Later Baku will save the young king. Kristin also points out the importance of motifs in tightening classical structure. Here we get recurring lines (“”I never freeze”/ “Did he freeze?”), the lip that identifies a Wakandan, the importance of border patrols, and the ring that reveals Erik as kin to T’Challa. Parallel scenes–two waterfall fights, two burial ceremonies with attendant ephiphanies, two street strolls of T’Challa and Nakia–measure significant dramatic differences.

Despite being an installment in a much bigger saga, Black Panther is a solid example of classical construction. (I don’t have to explain how it obeys the rules of continuity staging and editing, do I?) A hundred years after the Hollywood storytelling system settled in, it’s still shaping the movies coming out each Friday.

Main attraction: Worldmaking

Why have so many smart people thought that studio storytelling changed drastically after 1960, or 1945, or 1977? I think it was because trended change was happening along two of these three dimensions.

Narrationally, there were trends toward innovation. I argue in Reinventing Hollywood that 1940s filmmakers consolidated narrative devices that had appeared piecemeal in the silent and early sound eras. Those strategies–flashbacks, voice-overs, subjective sequences, self-conscious artifice, mystery plotting–gained a new prominence and were explored with unprecedented ingenuity. The 1990s was another period of experimentation, reworking all those techniques and more, such as network narratives and forking-path plotting. These suggested to sensitive critics that something new was up. For me, they show the versatility of the classical system, its ability to explore what Meyer calls its “preconditions.”

One broad narrational change I’d now emphasize is the tendency to be more elliptical. The opening of Black Panther doesn’t show us N’Jobu speaking to his son. This misled me, and perhaps some others. Executive producer Nate Moore explained:

“We landed on N’Jobu telling the story to his son, which wasn’t our first choice, but ultimately felt really satisfying,” said Moore. “Hopefully on repeat viewings you go, ‘Oh that’s who I was listening to, OK that’s cool.'”

A film in earlier periods would have shown us the speaker and listener, but we’ve so “overlearned” the convention of a tale told by an elder to a child that we need only one set of cues, on the soundtrack. Still, the uncertainty about the speakers–we haven’t met any of the characters yet–offers less redundancy than is traditional. I’m reminded of the old man’s voice-over that opens The Road Warrior; only at the very end do we learn his identity.

The elliptical prologue exemplifies what’s perhaps the most common change in narrational strategies across history. A lot of new practices, such as the substitution of straight cuts for dissolves and fades between scenes, involve this sort of reduction in redundancy. It’s possible because Hollywood films are traditionally quite repetitious in doling out story information, as is indicated by the infamous Rule of Three. (Once for the smart people, once for the average people, and once for Slow Joe in the Back Row.) Still, as is typical of trended change, not every film must adopt an elliptical technique. Black Panther‘s beginning could easily have shown us father and son talking, without any sense of being old-fashioned.

The suppression of the prologue’s speakers not only puts the emphasis on the tale but adds a bonus for repeat viewings. This is the sort of “thickening” of classical style I analyzed in The Way Hollywood Tells It. I proposed there that making the films available on video formats enabled fans to hunt for fine points and Easter Eggs. Nate Moore’s comments seem to presuppose this sort of fan-driven recidivism. Such sneaky bits for insiders weren’t unknown in earlier periods (I talk about some here and here and here), but the ability to scan and pause DVDs made such games more common.

The bigger changes across Hollywood history, and the ones that constantly impress observers, spring from the movies’ story worlds. The popularity of fantasy and science fiction is, from this standpoint, an extreme instance of the most common way that the tradition refreshes itself. Most of the novelty of Hollywood, I think now, involves worldmaking, big or small. Find new milieus, new characters, new situations. Create conflicted protagonists–fallible, vulnerable, torn by indecision. Turn the heterosexual romance into a gay one. Build your plot around an ensemble (Grand Hotel, Nashville). Take the heist formula and feminize it (Ocean’s 8). And on and on.

Repopulating the story world has another advantage: it yields a new range of thematic implications and thus invites interpretation. Get Out, a film we discussed a bit at the conference, calls on both specific horror-film conventions (the mad scientist, the innocent victim lured to a corrupt community) and broader classical conventions (a double plotline, a restricted viewpoint for suspense and surprise, 1940s dream states, a last-minute rescue). What made the film intriguing and controversial was turning the white bourgeoisie into modern plantation seigneurs re-enslaving African Americans. This refashioning introduces thematic material that can provoke public discussion.

You can call this endless remaking of story worlds unimaginative. But the variorum impulse, this combinatorial cascade of materials and techniques, seems typical of popular art. Art makers take familiar schemas and rework them in novel ways. I’m not exactly saying that everything is a remix, but everything does start from a point of departure in some tradition. Even Cubist painters needed the work of Cézanne and the genre of the still life in order to contrive their innovations.

Moreover, we’re far more sensitive to the story world than the other dimensions of narrative. We’re interested in other persons (or person-like agents, such as Dory), so naturally we’re quick to register the new people, places, and things that a movie prompts us to co-create. Narration and plot structure, although they have immense impact on us, are far less visible. So it’s not surprising that the most imaginatively gripping novelty in mainstream narrative film involves the creation of fresh agents and arenas for story action.

Compared with the story worlds, Kristin’s four-part-plus-epilogue template is far less noticeable. Yet it is a stable and enduring dimension of Hollywood storytelling. Given characters with goals, the narrative structure squeezes those into a sturdy and quietly familiar mold of rising action, delayed action, and culminating action. The strictness of the form, with its well-timed turning points and echoing motifs, seems as reliable as the conventions of narration. It’s a stubborn, persistent feature that testifies to the continuing power of the classical model of narrative.

I can’t claim to have fathomed all the principles of classical storytelling and style. Still, I think we’ve made progress in understanding the engineering, so to speak, of one major cinematic tradition. And it doesn’t exist in splendid isolation. Hollywood’s continuity editing system provided a lingua franca of popular cinema worldwide, and Hollywood narrative structure and narration has been borrowed, wholesale or piecemeal, in other national traditions. Filmmakers, having found a bundle of principles that are understandable and pleasurable to wide audiences, have clung to them for a very long time. Call it classicism or whatever, it’s real and strong and it works pretty well and I bet it’s not going away any time soon.

Thanks to Kat and Philippa for inviting us to their splendid conference. I believe that a book will collect the papers given there; when that happens, we’ll alert you.

More thoughts on our book can be found at “The Classical Hollywood Cinema twenty-five years along.”

The ideas in this entry stem from the books mentioned above, from Poetics of Cinema, and from several other items on our site. If you’re curious, you can look at Kristin’s explanation of the four-part structure and two pieces where I develop her template in relation to the action movie and in relation to traditional act structure. For application to some recent films, see this entry from 2016 , this one from 2017, and this one from last January. An analysis of The Wolf of Wall Street illustrates the three dimensions of film narrative.

P.S. 15 June: Fiona Pleasance, who corrected my attribution of the prologue’s voice-over, helpfully adds:

It could therefore be argued that not seeing the speakers is a weakness of the film, leading as it does to such confusion.

Personally I believe that, narratively, it does make more sense for the speaker to be N’Jobu. Growing up in Wakanda, as T’Challa does, we can assume he would learn about his country’s past by osmosis, without the need for his father to reiterate it. Such stories become much more important for exiles like N’Jobu and his son.

I believe this does not negate the idea of the father knowing more than the son, which is also addressed in Killmonger’s vision after taking the heart-shaped herb, when he confronts the image of his father, just as T’Challa has done. Also, Killmonger at one point refers to hearing his father tell “fairy stories” about Wakanda, which he came to believe were just that. (Or words to that effect. I’m working entirely from memory; I can’t check as the DVD hasn’t been released in Germany yet!).

Thanks to Fiona for writing! If other readers have further thoughts, they should correspond.

Some of the Badger brigade: Brad Schauer, Vince Bohlinger, Masha Belodubrovskaya, Lisa Dombrowski, Patrick Keating, and Lisa Jasinski.

Hollywood now and then: A conference at Wilfrid Laurier University

DB here:

An extraordinary event is shaping up for next weekend. Katherine Spring and her colleagues at Wilfrid Laurier University are hosting a conference, Classical Hollywood Studies in the 21st Century.

It features talks by scholars young, youngish, oldish, and just plain old. All are continuing to make striking contributions to understanding American studio cinema. The team is really staggering, a who’s who of expert researchers. There are also screenings of A Letter to Three Wives (1948) and Carmen Jones (1955).

The array of research questions and arguments is exhilarating. It shows just how many fruitful ways there are to explore Hollywood’s history, aesthetics, and cultural functions.

I will be giving a keynote talk. Yes, it’s intimidating to be facing such a stellar assembly. I will try to beguile them with Jedi mind tricks, tortuous and subtle arguments laced with distracting examples and Wildean wit. What could go wrong?

Kristin will be presenting as well. So will many of our Wisconsin colleagues and alumni: Tino Balio, Maria Belodubrovskaya, Vince Bohlinger, Lisa Dombrowski, Scott Higgins, Eric Hoyt, Mary Huelsbeck, Patrick Keating, Charlie Keil, Brad Schauer, Kat Spring, and of course Janet Staiger, our collaborator on The Classical Hollywood Cinema. I look forward to reuniting with these Badgers, to reconnecting with old friends from elsewhere, and to making new friends laboring on the same territory.

One outstanding feature of this get-together: No competing sessions. This allows us all to follow the same papers and build a sense of community, with discussion developing organically and continuing across three days. This is the best conference format, I think.

There are plans to publish the papers. We may be able to blog a little during the event.

Thanks very much to Kat and her colleagues for inviting us. I predict a hell of a time will be had by all.

Some background on our book, and thoughts about it twenty-five years later, can be found here.

Carmen Jones (1955).

Geoffrey O’Brien reviews REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in NYRB

Backfire (1950).

DB here:

The New York Review of Books has just published a review by Geoffrey O’Brien of Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. This is a big deal for me.

I never thought my work would be reviewed in a publication I’ve subscribed to since my college days. And to be reviewed by O’Brien is a special honor. He’s one of those wide-ranging intellectuals who are rare today. He writes fiction and poetry, and offers criticism of film, literature, music, painting, and theatre. He’s ideally equipped to appraise my arguments about how 40s cinema drew on narrative conventions in adjacent arts. He’s also a connoisseur of the obscure and marginal in classic studio cinema.

I especially admire his writings on noir film and literature, on popular music, and his study of American cinema as a sort of popular hallucination. The Phantom Empire makes this case memorably, but the opening of his review catches the flavor too.

One night not long ago I found myself once again drawn into a movie from the tail end of the 1940s. This one, with the thoroughly generic title Backfire (not to be confused with Crossfire or Criss Cross or Backlash ), did not come with a high pedigree. It had sat on the shelf for two years after it was filmed in 1948, and afterward seems to have faded quickly from recollection. But movies of that time, when they emerge decades later, have devious ways of holding the attention: beguiling hooks and feints lead deeper into a maze whose inner reaches remain tantalizing no matter how many times those well-worn pathways have been explored, and no matter how many times the interior of the maze has led only to an empty space.

One night not long ago I found myself once again drawn into a movie from the tail end of the 1940s. This one, with the thoroughly generic title Backfire (not to be confused with Crossfire or Criss Cross or Backlash ), did not come with a high pedigree. It had sat on the shelf for two years after it was filmed in 1948, and afterward seems to have faded quickly from recollection. But movies of that time, when they emerge decades later, have devious ways of holding the attention: beguiling hooks and feints lead deeper into a maze whose inner reaches remain tantalizing no matter how many times those well-worn pathways have been explored, and no matter how many times the interior of the maze has led only to an empty space.

In a state of suspended fascination only just distinguishable from the preliminary stages of dreaming, I remained absorbed as documentary-style scenes of wounded war veterans recuperating at a hospital in Van Nuys, California, gave way to progressively more disjointed and often barely comprehensible episodes: an unidentified woman creeping in the dark into a patient’s room with a message about a missing war buddy, a murder investigation, a cleaning woman peering through a keyhole in a fleabag Los Angeles hotel, a winding path from mortuary to boxing arena to gambling den to the office of a particularly corrupt doctor, a plaintive piano theme playing over and over accompanied by reminiscences of its origin in a far-off Austrian village. The story splintered into flashbacks, spiraling into deepening confusions of identity and chronology, punctuated, as if to keep the spectator awake, by a series of point-blank shootings.

All the while, the dialogue was evoking the trauma of wartime injury, questioning the difference between memory and hallucination, talking about nightclub rackets, tax evasion, gambling debts, obsessive love, as the narrative coiled in its final swerve toward a strangling, silhouetted on a bedroom wall while Christmas carols were sung in the background. And then, abruptly, the nightmare was over, we were back in the veterans’ hospital after a second and successful round of rehabilitation, and the three surviving principal characters were even managing to laugh as they took off in their jeep for Happy Valley Ranch. By then I could hardly have said what the movie was about or even if it was especially good—few viewers have ever thought so—yet could not deny that something had caught me in its grip and stirred up troubling associations, like partially retrieved memories of a parallel life.

Apart from wishing I could write like this, I find myself agreeing. Popular culture does offer us a phantasmagoric alternative world that we can drift through in an almost somnambulistic way. I don’t see this argument as the sort of Zeitgeisty criticism I’ve complained about elsewhere. Rather, I think it’s in the spirit of Parker Tyler, who saw Hollywood not as reflecting a collective psyche but as building occasionally rickety story worlds out of cultural flotsam scavenged from wherever. Not a mirror but a mirage.

That hallucination demands that conventions and schemas, norms and forms, bring order to an occasionally demotic array of materials. Given this orientation, the sort of analysis I float in Reinventing Hollywood might seem to be overthought and flat-footed. But O’Brien gets into both the book’s research assumptions and its ambitions. He sees that I was trying to figure out how the dépaysment of Forties cinema stems from the frantic pressures of the industry, ambitious filmmakers itching to explore unusual narrative strategies, and the jolts that occur when time schemes collide, motives get muddled, and story premises wriggle out of control. To savor eccentricities, you need the sense of a center, and that’s where my inquiry starts.

It’s a generous review. O’Brien makes my arguments crisp and cogent, and he adds ideas of his own. It’s a review that both fans and nonspecialists can learn from, as I did. It’s also good to know that some of my jokes didn’t fall flat. (I can hear readers asking: Wait, there were jokes?)

For more on Reinventing Hollywood, go to the tag 1940s Hollywood. The book is available from the University of Chicago Press website and the mighty Amazon. As ever, I owe thanks to the University of Chicago Press staff, particularly Rodney Powell, Kelly Finefrock-Creed, Levi Stahl, and Melinda Kennedy.

I discuss Parker Tyler’s conception of the Hollywood Hallucination in The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture.

New colors to sing: Damien Chazelle on films and filmmaking

La La Land.

DB here:

Between the end of principal photography on First Man and the start of post-production, Damien Chazelle squeezed in a visit to the UW–Madison. We’re very glad he did. A hell of a time was had by all.

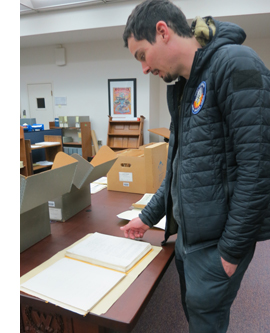

His visit culminated a Cinematheque series devoted to his work. On Friday 23 February we picked him up at O’H are and had a fine ride back talking about film and less important things. Then he visited our archives at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research; on the right, he examines an original Final Revised script of Citizen Kane.

are and had a fine ride back talking about film and less important things. Then he visited our archives at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research; on the right, he examines an original Final Revised script of Citizen Kane.

After that, he sat down for a conversation about his career with a hundred or so students. At a quick dinner, he and our Cinematheque impresario Jim Healy gave dueling impersonations of Michael Gazzo as Frankie Pentangeli. Damien then plunged into a long Q & A with a full house who had just seen La La Land in 35mm.

Next morning he met with Criterionistas Kim Hendrickson and Grant Delin for a FilmStruck segment. Then, in a discussion with Kelley Conway, he introduced a string of films he curated for the Cinematheque. But he wasn’t off the hook, because driving back to O’Hare with Kelley and Jeff Smith, he was immersed in more film talk.

Damien proved himself the ultimate guest—friendly and generous, enthusiastic and excited, free of airs and snark. We learned a lot from him. Herewith, a sample.

A Direct-Cinema musical

Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench.

Although he considered a musical career, film was Damien’s first love. He wrote scripts in middle school, transcribed movie dialogue from VHS tapes, and as an undergrad watched films in Harvard’s magnificent archive. The film program there, with leaders like Alfred Guzzetti and Ross McAlwee, stressed documentary and experimental film, and the exposure stuck. Among the films Damien curated for our Cinematheque show were the Rouch-Morin investigation Chronicle of a Summer and Su Friedrich’s Sink or Swim.

No surprise, then, that his first feature, Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench, was shot in a Direct Cinema mode. It’s got light leaks and run-and-gun footage, complete with bumpy handheld pans and zooms. To get around problems of inexperienced actors, Damien told some of them that it was a documentary. The 16mm project was produced over three years; sometimes the exposed films sat in the lab while Damien drummed up donations from friends, family, and strangers. (Writing blind to Harvard alums, Damien got a donation from John Lithgow.) When a processing accident ruined some footage, Damien’s producer talked the lab into free work for a time.

Guy and Madeline cuts among three characters: trumpeter Guy, his ex-girlfriend Madeline, and his new girlfriend Ilena. Like a Nouvelle Vague film, it relies on chance encounters. Madeline is emotionally wrenched by the breakup with Guy, and we follow her efforts to find work and a new partner. Ilena’s semi-reluctant meeting with an older man who brings her home to meet his daughter reminded me of the moment in Shoot the Piano Player when Charlie, running from the thugs, falls into step beside a stranger who tells him his own troubles. And of course the title characters recall the separated lovers of The Umbrellas of Cherbourg.

For all its documentary textures, the film at times becomes what J. Hoberman called a Mumblecore musical. But there’s a gradual shift to the full-blown show-biz mode. Damien talked of the thrilling moment in Hollywood musicals when realistic presentation of a scene gives way to nondiegetic music and the characters leap to a new, more ethereal level. Guy and Madeline presents this transition in gradual doses.

At first, the numbers are motivated realistically. Guy, an African American, plays trumpet with a jazz ensemble, so we get scenes of their performance at a local hangout. We move a bit further toward stylization with a party sequence that induces some talented kids to indulge in singing and tap-dancing among their friends—captured in casually imperfect framings.

The transition to pure musical fantasy comes forward after the breakup in a solo number, with Madeline singing a soliloquy as she wanders in the park. There’s no sense of an audience; this is a private reverie. (A whiff of this tune, heard on a car radio, makes its way into La La Land‘s opening shot.)

When Madeline takes up work at a diner, the components come together in an all-out production number addressed to us.

In an echo of Bande à part’s “Madison” sequence (lucky name), shooting a dance number in cinéma-vérité mode brings out an intriguing friction. It’s the same kind of productive clash we get on the soundtrack, between Justin Hurwitz’s shimmering Legrand-inflected score and varieties of jazz (Dixieland, Guy’s cool composition for Madeline). And like Nouvelle Vague characters, these people are devoted to books, the arts, and self-exploration.

As a “staged documentary” Chazelle’s film parallels Chronicle of a Summer in an intriguing way. That film starts as pure Direct Cinema, with investigators stopping people on the street to ask them questions. But as we get to know the group the film concentrates on, there’s a lot more control and “fictionalization.” There are precise matches on action, for instance, with camera ubiquity indicating careful restaging.

This rigging doesn’t damage the film as a document of summer 1960. Damien learned from it that you can make a truthful movie by “creating a situation with less and less acting to do.” Given this hybrid quality, Chronicle of a Summer becomes a vivid example of a moment when a film mode is “figuring itself out.” Its self-conscious artifice, which includes participants watching themselves during a screening, was foundational for the New Wave. “You watch a language being born.” That language was also political, as Damien pointed out: The film summons up memories of the Holocaust and glimpses of the Algerian war.

In other respects, Damien’s first film looks forward to La La Land thematically and formally. Guy and Madeline starts with the moment of the couple’s breakup (on the bench) and flashes back to vignettes of their love affair before returning to the bench. This opening loop is like the one that jumps from Mia’s night out back to the traffic jam and then follows Sebastian. A large stretch of each film’s plot is about how the couple’s lives converge and diverge.

Similarly, when the signature tune “I Left My Heart in Cincinnati” is played, shots of Madeline and Guy frame a flashback to the combo’s earlier performance, as if they’re sharing the memory. Something similar happens at the climax of La La Land, in what seems to be a mutual vision of Sebastian and Mia’s alternative future. As often happens in Chazelle’s cinema, epiphanies burst out in moments of musical performance.

Blood, sweat, and tears on the drumhead

Grand Piano.

Despite playing many festivals and winning critical praise, Guy and Madeline didn’t open any doors in Hollywood. Damien picked up odd jobs, not all film-related, while writing commercial genre screenplays. He sold a kidnapping script (not made) and Grand Piano (2013), skillfully directed by Eugenio Mira. He began getting assignments like The Last Exorcism Part II (2013) and he contributed to the screenplay for what became 10 Cloverfield Lane (2017), released long after he’d worked on it.

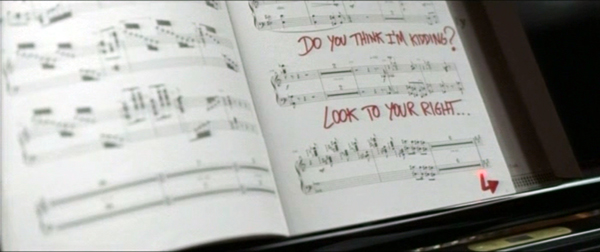

I found Grand Piano pretty impressive on the big screen. Chazelle’s script and Mira’s direction create a solid thriller built around the situation Hitchcock designed for his versions of The Man Who Knew Too Much. Most of the action takes place during a concert celebrating the return of a traumatized pianist to the stage. As he’s about to start the program, a sniper uses cellphone messages and scribbles on the score to demand a perfect performance of the florid piece that spooked the pianist years before.

At first restricted to the pianist, the film’s viewpoint widens gradually to include others, and soon crosscutting builds tension. The tormenting voice (“Play one wrong note and you die”) calls to mind the music teacher in Whiplash. As in a classic thriller, the climax arrives when the victim must fight back. And as in Whiplash, the performer wins using the only weapon he has: nearly crazed virtuosity.

Damien now thinks that the long germination of the scripts for Whiplash and La La Land made them better. As financing kept falling through, the films gained more layers. Whiplash (2014) found a home first, with Blumhouse producing and helping with the financing. It was their idea to shoot a scene to show investors (we screened it in our series), and the project found financing at Bold Films.

Given a $3 million budget and a 20-day schedule, Whiplash demanded meticulous storyboarding and very little coverage. Like Hitchcock and Leone, Damien shot only what he needed. He used two cameras for the rehearsal scenes and three for the climactic concert. The cuts and camera moves were planned to coincide with measures of the music.

Damien calls Whiplash a film about music (the same could apply to Grand Piano). It owes a lot to the sports-film genre as well; Damien envisioned its punishing force as indebted to Raging Bull. He turns big-band drumming into blunt-force trauma, with gory drumheads and cymbals. Sam Fuller would have approved.

Like Guy and Madeline and Grand Piano, Whiplash culminates in a musical performance that carries a powerful emotional impact. No wonder that as a kid Chazelle studied one-reel movies of classic drummers, then started to think of the shorts as films in their own right. In this spirit he curated for us two Dudley Murphy shorts, St. Louis Blues (1929, with Bessie Smith) and Black & Tan (1929, with Duke Ellington), along with the 1954 documentary Jazz Dance, a night on the town that explodes with pure human happiness. In all these, music-making is pushed to the edge of ecstasy.

This time around with Whiplash (good name for a movie about sadomasochistic musicians), I noticed its straightforward classical construction. Damien says that he learned screenplay construction after moving to LA. Its tale of a boy caught between a good but weak father and a punishing, strong one gains strength and sharpness from its traditional four-part plot.

At the crucial 25-minute mark, Fletcher wins Andrew’s trust. Four minutes later, in the performance of “Whiplash,” Fletcher is bellowing and Andrew is sobbing. First reversal noted. The second part, the Complicating Action, interweaves Andrew’s romance with Nicole, his persistence in drumming, and his fraught relation with his family. This part culminates at the midpoint with Fletcher’s giving Andrew a new rival, which impels Andrew to break up with Nicole. In the Development section, Andrew suffers more setbacks. A harrowing car accident leads him to botch a major competition and assault Fletcher. He leaves school, accuses Fletcher of abuse, and abandons drumming.

After he discovers Fletcher playing piano in a club, he agrees to join his new combo, which preciptates the climax: a competition performance at which Andrew, realizing that Fletcher is out for revenge, seizes control. The result is another burst of barely controlled frenzy, complete with unmotivated bursts of light spattering Andrew in the last shot.

Whiplash is a film without pity. Andrew’s rejection of Nicole suggests that he’s become obsessive, and after his scuffle with Fletcher he’s drained and numb. And no sympathy is extended to the monstrous Fletcher. Damien avoided what he called the “rubber ducky” moment that shows this man to be damaged by some childhood trauma. We get no explanation of his ruthless brutality; he’s simply a force to be fled or fought. (Damien told us that he modeled Fletcher on a music teacher he’d had; the original probably wasn’t as nasty, but Damien wanted the film to convey how frightening he was to a fifteen-year-old.)

At the end, Andrew earns a glint of triumph, but the reverse shot shrewdly withholds from us the expression that might warm us up to this man. His sliced-off smile and slight nod are all it takes for Andrew to react.

Still, his grudging approval means that Andrew has won over one scary dad.

Embarrassing yourself and your characters

At 29, Chazelle found himself with a hit, confirming the Magic Number 30 Rule. Whiplash made a splash at the Sundance Film Festival and went on to be nominated for several Oscars, winning three. It also brought in a lot more than its cost. Damien could now reignite La La Land.

Lionsgate, via Summit, picked it up and production began. There were 40 days of shooting across 65 locations. The production was able to be so efficient because of careful planning and the reliance on long takes. “The long take has become fashionable,” Damien says, who knows his film history: “But it’s actually the most old-fashioned kind of thing.” Whiplash is an editing-driven movie, but La La Land relies on many fewer shots. The moments of shot/reverse shot–notably in the spoiled dinner when Sebastian is briefly between tour gigs–gain a prominence they don’t have in most movies.

In shooting, the morning was given over to rehearsals, followed by a great many takes–often required to sync the actors to playback. Around about take twelve, Damien recalls, things started to crystallize, but sometimes as many as twenty takes were needed. While Whiplash stayed tight to the screenplay, La La Land was heavily improvised. The visuals were pre-designed, but the relationship at the center needed a casual feel, as if the characters were tossing off their lines.

Damien had thought he would simply be able to cut together the “one-ers,” but editing took five months, not least because he and his long-time editor Tom Cross played with many versions. Every number was a candidate for deletion, including the freeway opening. (Yeah, I shuddered.) There was also some digital adjustment of the 35mm original. David Koepp wrote me:

Maybe ask Chazelle about how beautifully he used color to direct our eye in his LA LA LAND opening. Always the right burst of costume color directing us to the right spot at the right time… although I guess that’s more of a compliment than a question.

Damien explained that he made those colors pop a bit more by digitally toning down other costumes in that intricate opening sequence.

La La Land has steadily grown in my regard and affection; I think it’s one of the best recent American movies. Just the title gets you going. “La la” suggests music, but also the self-absorption of jamming your ears lalalala. LA is a town of airheads, but it can become a town of worthwhile fantasy too. Damien spoke of most movies trying to make fake sets look real; he wanted to “take real stuff and make it look false.”

This time around, I was struck by the film’s harsh side. It’s pretty hard on mainstream Hollywood, from the smug partygoer who says he’s really good at world-building to Mia’s superficial roommates. Their anthem “Someone in the Crowd” is about careerism, but it becomes for her about the search for a soulmate.

Then there’s Sebastian. A lot of Hollywood plots work only if the guy is a jerk. In Whiplash, Andrew turns smug when he thinks he’s Fletcher’s pet, and he dumps Nicole heartlessly. (He’s becoming a bit like Fletcher.) In La La Land, I began to see Sebastian as a stubborn nerd, refusing to play the cocktail-bar set list and ranting about jazz to anyone who’ll listen. Ryan Gosling’s ingratiating performance makes this nerd more likable, but as written the character is pretty arrogant.

One scene that puzzled me now makes sense in a larger pattern of Seb’s obtuse, evasive behavior. After he learns he may be kept from attending Mia’s show, why doesn’t he phone her? We see him brooding outside the music studio.

He may think he can still make it in time, which would reflect his somewhat risky self-assurance. But Damien pointed out that elsewhere in the film he’s not seen using a cellphone, or for that matter a computer. Old school as he is, he seems wary of modern technology. He drives an utterly impractical Buick convertible. He plays cassette tapes and LPs and his apartment’s phone is an old-style handset, antenna and all. An omitted screenplay scene showed him in a movie audience ranting at somebody using a phone, thereby disturbing the viewers more than the caller has.

I’m being too hard on Sebastian, of course. We admire his idealism, his tenacity, and his romantic attachment to what he thinks is the best of the past. Still, Damien has remarked that he sees sides of himself in both Andrew and Sebastian, which reminds us that “commercial” films can also be personal ones. For him, the strongest creative choices risk exposing you. “If you’re not embarrassing yourself, you’re not doing your job.”

If Sebastian is too willful, Mia is too eager and desperate. “I can do it differently,” she tells the audition staff after they’ve brushed her off. Sebastian and Mia complement each other. His cockiness (“Fuck ’em”) pushes her to mount her one-woman show, while she tries to steer him back to his basic commitments. The larger theme seems to me that the most vital art comes from yourself, be it your memory of a Francophile aunt or your irrational attachment to classic jazz. Instead of having to fit into prefab TV characters, Mia gets her breakout role in a film that will build its script around her personality.

Damien spoke of the musical as Hollywood’s most avant-garde genre. That partly stems from the transition from realism to fantasy that launches a number. This shift provides the film’s final turning point, with Mia’s audition; for once a Chazelle film makes its musical climax a subdued one, but it’s no less a demonstration of the performer’s authentic emotion. Art’s power comes from novelty (“new colors to sing”) grounded in sincerity and self-awareness, even if by some standards it seems awkward and geekish.

The avant-garde overtones are also a matter of how musicals make real locations look unreal—as Demy films memorably show. So it was uncannily appropriate that Damien asked us to introduce La La Land with Bruce Baillie’s All My Life (1966). A slow pan left across a fence and flowers gives way to a diagonal tilt up to the sky; the whole accompanied by Ella Fitzgerald and Teddy Wilson.

La La Land might well be a sequel, as we tilt down from another blue sky to a gridlocked freeway.

As Baillie turns a prosaic bush and fence into an audiovisual flow, so the opening of Chazelle’s film takes the banality of a traffic jam and makes it an explosion of youthful hope and energy, complete with somersaults.

The sheer cinematic exuberance of La La Land will, I think, keep the film alive for a long time. “Every scene, a new idea”: Damien quoted Arnaud Desplechin quoting Truffaut. Many parts of La La Land put nifty tweaks on the conventions of comedy, drama, and the musical. There’s the “enacted” slow-mo at the party, the iris around a kiss, and the montage rendered as a flash-forward from a duet at the piano (“City of Stars”). There’s often a tweak on what might have been perfunctory filler. The exit-on-an-elevator shot is lit and costumed so as to (a) suggest the conformity of the dress code for an audition; (b) emphasize the height of her rivals; and (c) accentuate the spill on the less glamorous Mia’s blouse. Her disadvantages are diagrammed.

Then there’s the idea of having a “real” dream ballet at the planetarium and a virtual one at the end. Speaking of the end, I especially liked the head-fake at the start of the present-time part. By showing Mia on the Warners lot and Sebastian in his club, we’re invited to infer for a moment that they stayed a couple, before revealing that she’s actually married to an easygoing beefcake and Seb still lives alone.

Pitching La La Land, Damien found that many producers insisted that the couple unite for a happy ending. Damien objected that many of the great romantic films, including Casablanca, A Star Is Born, and Gone with the Wind, center on lost love. Still, he found a way to a happy ending by offering an alternative outcome that many viewers will prefer.

True, it’s sad. But Jacques Demy once remarked that sad movies make him happy. For me, La La Land is that sort of movie.

How much does cinephilia help a director? I’d expected Damien to recommend the sort of movie immersion he had as a kid. And he admitted the power of the past. “I can’t unwatch the movies I’ve seen.” But some great directors aren’t cinephiles, he granted. He cited Bresson and Dreyer; I thought of Ford. What’s important, he suggested, is a relation to some, any art form–if not film, then visual arts or theatre or literature.

Maybe the best of both worlds is to be a young filmmaker who knows both film and another medium, such as music, and thinks as an audiovisual artist. Damnien remarked that in writing he starts with images rather than words but then lets the dialogue focus the scene. Interestingly, Eisenstein taught his students to stage a scene first as if it were in a silent film, then revise it with music, color, and (only then) dialogue. That assured that pictorial storytelling would be foremost.

Kristin and I were gratified to hear that Damien has over the years read several things we’ve written. In turn, he taught us a lot. His visit reminded me that one path to filmmaking achievement is just thinking about your craft and your choices, in light of your life experiences and your encounters with powerful art. He passed that lesson along to the hundreds of people who came to learn from him.

Thanks to Damien Chazelle and Alissa Goldberg for making the visit possible. Thanks as well to J. J. Murphy, Mike King, Ben Reiser, Matt St. John, Mary Huelsbeck, Amy Sloper, Maria Belodubrovskaya, Erik Gunneson, Jason Quist, Kim Hendrickson, and Grant Delin. Event planners Kelley Conway, Jeff Smith, and above all Jim Healy, Cinematheque Director, deserve massive gratitude as well.

We have other discussion of La La Land on this site: my search for some of its roots in 1940s innovations, and my analysis of its song plot. There’s also a wide-ranging conversation among experts Kelley Conway, Eric Dienstfrey, and Amanda McQueen. Jeff Smith weighed in on the film’s score, correctly predicting its Oscar triumph.

P.S. 8 March 2018: Many thanks to Steve Elworth for a correction about All My Life.

Kelley Conway interviews Damien Chazelle.