Archive for the 'FilmStruck' Category

On the Criterion Channel: Five reasons why HIROSHIMA MON AMOUR still matters

Often this scandalous or honorable story, this beautiful or ugly one, will be told you the next day or the next month, sometimes in fragments. There is nothing that is of a piece in this world, everything is a mosaic.

Balzac, Une fille d’Ève

DB here:

We’re not big fans of listicles. Our only effort in this direction is our annual review of the 10 best movies of 90 years ago. But now we have my Criterion Channel installment devoted to Hiroshima mon amour. (There’s a sample here.) The installment is focused on the film’s use of editing. That topic does allow me to touch on wider matters of storytelling and theme, but I found myself struggling to squeeze in all I wanted to say. So. . . .

If you haven’t seen the film, both this and the Criterion Channel segment will teem with spoilers. Now I’ll give a plot synopsis, but the shocks in the film’s early stretches are probably softened if you know the story’s premises. So if you haven’t seen the film yet, you’re advised to stop reading now.

Hiroshima mon amour, the 1959 feature film directed by documentarist Alain Resnais, tells the story of a brief sexual affair between an unnamed man and woman. She has come to Hiroshima to make a film about the effects of the US nuclear bombing of the city in 1945. Her plane is scheduled to leave the following day, but he asks her to stay longer in Japan. As a result, what drama there is becomes psychological—pressured by her deadline, but complicated by her memories.

After their first night of lovemaking, she tries to break with him, but in the course of the day he pursues her and they meet at intervals. They go to his house for another bout of lovemaking, to a bar called the Tea Room, to the train station, and back to her hotel, where the film began. In the course of their affair, she recalls and recounts her wartime romance with a German soldier stationed in her city of Nevers. At the liberation, he was shot by a sniper. The townsfolk punished her by cropping her hair and confining her in a cellar.

In a gesture characteristic of ambitious cinema of the period, we don’t definitely learn that the woman decides to leave. The final scene, suggesting that she will always think of the man as Hiroshima, does imply that they’re parting. More important, in the course of their affair she has realized that her memories of her first love are fading, and she fears that makes her deeply disloyal to him. Worse, she feels that she’s already forgetting her Japanese lover. The passage of time and the waning of emotion come to feel like a betrayal.

Hiroshima is one of the most important films ever made, summing up many tendencies of modern cinema but also indicating new directions for later filmmakers. Its implications and possibilities radiate out in several directions, like the spidery silhouette (in negative?) under the opening credits. So a listicle format seems, for once, justified.

(1) The opening

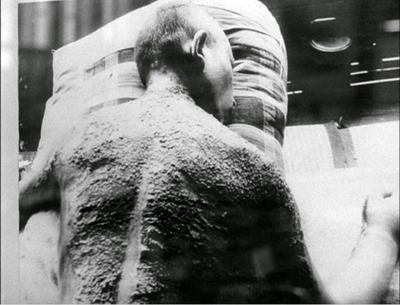

Two bodies, from the waist up, are locked in an embrace. The faces aren’t visible. At first, the bodies are powdered with dust but as the images dissolve into one another, the limbs are glittering and then oily with sweat.

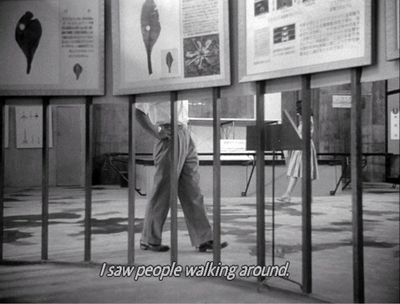

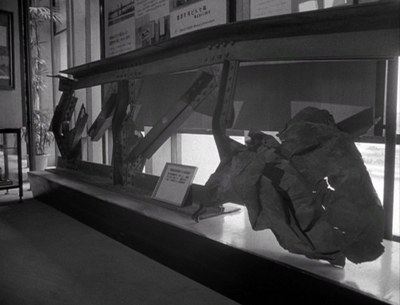

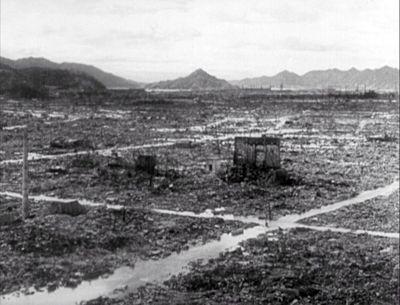

These images give way to documentary-style shots of Hiroshima, both in the present and in newsreel footage. We see modern architecture, a hospital, museum exhibits, city streets, a cheerful lady bus conductor, victims of the nuclear blast, and even restaged scenes of the bombing’s aftermath, taken from fiction films.

Over all the footage float a male voice and a female voice: “You saw nothing in Hiroshima–nothing.” “I saw it all…” She describes what can be seen and understood, while he contradicts her. We return intermittently to their bodies. The sequence concludes with her voice: “I met you here.”

Thus ends one of the most daring sequences in film history, a dense thirteen minutes of imagery, music, and dialogue. I think it’s hard for us today to grasp just how jolting this opening felt in 1959. Ten years after its premiere, when I first saw it (and without much foreknowledge), I was overwhelmed. For me, and I think for many others, cinema wasn’t quite the same after this.

For one thing, there’s the sex. Although it’s portrayed abstractly, the voluptuous skin tones and clutching, twisting arms are powerfully erotic–and poetic. The oily skin might be considered realistic, but the dust particles can’t be justified as anything but metaphorical, perhaps nuclear fallout or the ashes of a city in flames. (Is this like the embracing couples discovered in Pompeii by the heroine of Voyage to Italy?) Later the sexual angle will become more socially specified; it’s an “interracial” coupling, involving a French woman with a Japanese man. An entire “social problem” movie could be made about this situation, which this film takes utterly for granted.

Then there’s the juxtaposition of this stylized intercourse with the bombing of Hiroshima–and naked bodies very different from the ones we see in bed. We’re given smooth tracking shots through a hospital and a museum. In some of his documentaries Resnais had presented locales in solemn, slightly disquieting traveling shots, mimicking a tourist-eye view into a library (Toute la mémoire du monde, 1956) or a concentration camp (Nuit et brouillard/ Night and Fog, 1956). Here, similar traveling shots are more or less anchored to the unseen woman reporting on her impressions.

I say more or less because, in a slippage characteristic of the film, sometimes the camera height is lower than an adult’s eye level, as in the second shot above. And often the camera is withdrawing along the line of the museum exhibits, as if looking backward.

Already the imagery is rendered a little detached from a human perspective. More generally, by suppressing the woman’s face and eliminating diegetic sound, the shots for all their concreteness seem unreal, as if pulled up from memory or imagination.

When the shots segue to found footage (“I saw the newsreels”) and then to strident reenactments, those too seem less historical records or blatant fictionalizing than part of a phantasmagoric vision.

Maps and twisted relics, faces and stones, kitsch and authentic suffering are all put on the same plane, with a disturbing neutrality.

Perhaps this is the tragedy of Hiroshima as absorbed by a consciousness unequal to it. But what consciousness could comprehend it? Night and Fog openly proposed that our minds couldn’t grasp the enormity of the Holocaust. Not that this was a counsel of despair; our very helplessness was a warning to remain vigilant against the next glimpse we might get of human monstrousness. Here another voice challenges the limits of our sympathetic imagination: “You saw nothing.”

What about the opening’s soundtrack? Plaintive piano music, Debussy-ish, passes to strings and woodwinds–slow and brooding, but sometimes disarmingly bouncy. Nothing could be farther from the Mahleresque scores of Hollywood cinema or most documentaries than this chamber-music intimacy. The score pulls a bit away from the images, we might say, seldom emphasizing them even at their most horrific.

In his documentaries, Resnais had pioneered a lyrical, somewhat dry voice-over quite different from the conventional nudging or hectoring Voice-of-God commentary. Like the tracking shots, though, this vocal technique takes on a new effect in a fictional cinema. For one thing, when and where is the conversation occurring? Not evidently during the lovemaking. Before? After? Maybe never? Is it a sort of telepathic exchange, expressing the essence of her tourist-level days in the city and then his assured sense that such an experience blinded her to the real Hiroshima? Interestingly, we’ll learn that he wasn’t in Hiroshima during the attack. So perhaps he, like the narrator of Night and Fog, is warning her against premature confidence in understanding any historical event on this scale.

The woman’s voice dominates the soundtrack, meditating on her lover and her surroundings. Again, it might be a monologue addressed to the man at some point, but thanks to rushing shots through Hiroshima streets, it equates his body with his city. This motif will culminate at the climax, when she compresses her memories of 1944 down to landscapes in Nevers and she decides to give her lover a name: Hiroshima.

Since the mid-1940s, André Bazin had argued that the future lay with long take-filming that respected the continuum of reality–the continuum that Soviet filmmakers had freely splintered in order to make rhetorical and poetic points. Yet with this overture, Hiroshima revived and revamped the Soviet tradition of montage-based moviemaking. The sequence averages a little more than six seconds per shot, a rate seldom seen in European fictional film of the 1950s. The result somewhat recalls the free editing of Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, but it anchors the visual disjunctions in psychology and a personal drama yet to be specified.

Bazin had worried that by chopping the world into little fragments, editing by its nature ruled out ambiguity of expression. Yet here was a film that showed, as avant-garde filmmakers had done, that montage could generate poetic ambiguity. Editing patterns could create analogies and associations. The spatter on a rock could evoke the scars on a victim’s head, and the dusted couple of the opening could become ghostly doubles of a victim of radiation.

One could even intercut staged footage and documentary material without hiding the filmmaker’s artifice (as Citizen Kane does with the faked footage in “News on the March”). Free montage and collage-like mixing of documentary and fiction would be hallmarks of 1960s and 1970s films by Alexander Kluge, Dušan Makavejev, and of course Jean-Luc Godard.

Something similar happened with the soundtrack. Detached, unemphatic scores would become part of the repertoire of modern cinema, as would floating voice-overs. Films like Chungking Express and Wings of Desire, to say nothing of the work of (again) Godard, would show the expressive power of voices cut free from story time and space. Montage, as Eisenstein prophesied juxtaposed not only image to image but image to sound.

No later passage of Hiroshima mon amour is as aggressively disorienting as this overture. It’s as if Psycho started with the shower sequence. This opening not only introduces a lot of cinematic and thematic material. It also seeks to sensitize us to images and sounds, as a poem at the start of a novel might sensitize us to language. My discussion of editing in the Criterion installment points out that most of the ensuing film is cut in a pretty orthodox way, respecting the rules of continuity construction. But the sheer disjunctiveness of this prologue prepares us to notice whatever abruptness and juxtapositions do arrive. Assailed by this opening, at once jagged and eerily smooth, we’re set to register some even finer-grained shifts in time and sequence to come.

(2) Flashbacks that aren’t flashbacks

Hiroshima’s script by Marguerite Duras was, Resnais claimed, based on “parallel editing” that would link wartime France and contemporary Japan. But Resnais insisted that this editing didn’t create flashbacks.

Here is another movie, one that Resnais and Duras didn’t make. A French woman visiting Hiroshima on a film shoot turns tourist. She then meets a Japanese man and they have sex. Next day she avoids him, but he pursues her and eventually she agrees to spend the evening with him. In a bar we get the big reveal: the woman explains her wartime love affair and the punishment that drove her out of Nevers. Her past episodes are given in large blocks, perhaps one long flashback. The plot concludes with the man and the woman forced to choose their future.

We’ve already seen that the woman’s tourist-eye view has been fragmented, scrambled, and stylized in the opening montage. We might be tempted to call those images flashbacks, were they not so firmly part of an overall collage including purely documentary material. But once the story proper begins, we, or at least I, am inclined to call the bursts of images from 1944 Nevers flashbacks–brief ones, but flashbacks.

I say this because I take the primary purpose of a flashback is to present story material out of chronological order. A secondary purpose, not always in force, is to represent a character’s memories. Some films, especially after Pulp Fiction, rearrange story order without appeal to character memory. In classical studio cinema, though, flashbacks are usually motivated by a character recalling or recounting an event that she remembers. More often than not the scenes we see in the past aren’t restricted to what she witnesses or even knows about. Memory provides a rationale for the main purpose–revealing action in the past.

But there’s a contrary line of thought that says that a character’s memory ought not to count as a flashback because memories exist in the present. Arthur Miller took this line with respect to the time-shifts in his play Death of a Salesman, as I discuss in Reinventing Hollywood. Resnais, it turns out, felt the same way. For him, the fragments of the past that interrupt the present-time scenes of Hiroshima exist in the present because they’re being remembered. He wrote to Duras during shooting: “The past won’t be expressed by true flashbacks, but will be felt to be present throughout.” In 1968 he reiterated: “In Hiroshima there is not a second’s worth of flashbacks.”

There’s no point in quibbling about terms, but we should note that Resnais thought his interruptive images of the past were capturing something important about how memory works. Memory is fragmentary and jumbled, not operating in the big chronological blocks given us in 1940s Hollywood flashbacks. When asked by his producer if Citizen Kane hadn’t already shifted chronology, Resnais replied: “Yes, but with me, it’s all disordered.”

Moreover, memory is abrupt and fragmentary: Resnais uses cuts, not dissolves, to deliver his memory images. The first instance in the film has become a locus classicus. The woman sees her Japanese lover’s hand twitch, and that leads to another hand, a quick pan to a dead man being kissed, and then the Japanese lover again. This time-shift is literally a flash, lasting only a few frames.

And to insist that memory operates in the present moment, Resnais uses present-time diegetic noise–a train whistle in the scene above, a pop tune on a jukebox later–providing something that literature can’t: the absolutely simultaneous presence of now and then.

Again, Resnais brings into sound cinema narrative strategies that had emerged in silent film. Gance in La Roue, Fredrikh Ermler in Fragments of an Empire, and others had provided rapid-fire memory montages. In most commercial sound cinema, this sort of mental imagery was largely confined to one-off sequences depicting dreams, hallucinations, or mental illness. Resnais and Duras boldly made an entire film in which recollected moments unexpectedly erupt into present-tense action.

Again, though, the filmmakers introduce ambiguity. It’s hard to plausibly assign some of the “memories” of Nevers to the female protagonist. Bare landscapes and abrupt tracking shots of empty streets seem more like Eliot’s “objective correlative,” more oblique representations of feelings, than traces of what the woman has witnessed. Even the invasive images from the past aren’t free of the uncertainties that hover over the opening sequence. This strategy of hovering between subjectivity and “authorial commentary” would become central to 1960s art cinema–perhaps most obviously in Red Desert, where the unrealistic color can be taken as both an expression of the protagonist’s alienation or a more detached, stylized presentation of a modern wasteland.

(3) Talkies and walkies

Griping about Antonioni’s longueurs, Dwight Macdonald remarked that “the talkies have become the walkies.” His complaint captures something important. From Bicycle Thieves through La Strada and L’Avventura up to Linklater’s Before/After trilogy, the idea of building a plot around two characters’ more or less mundane traipsing became a salient option for filmmakers who wanted to stray from classical narrative organization.

But settling down in one place to talk became important too. Serious European cinema often featured dialogue scenes of a length that would have been discouraged in American cinema. Play adaptations like Sjöberg’s Miss Julie (1951) naturally featured such protracted conversations, but so did works by Bergman such as Waiting Women (1952), Wild Strawberries (1957), and Brink of Life (1958). Having revived silent-film montage in Hiroshima‘s early stretches, Resnais and Duras makes peace with their contemporaries in the second part by settling their characters down for two good chats broken by a long stroll.

It all starts when the man declares, after a second bout of lovemaking, that they have sixteen hours to kill before her departure. By Hollywood standards, this period should be handled with dramatic crises leading to the deadline. Instead, we get a quick montage of the city at dusk (with figures unnaturally still, as if rehearsing for walk-on parts in Last Year at Marienbad) and the two of them at a table in the Tea Room bar.

It’s in this lengthy scene that the woman’s memories become most coherent for us and the man. What was private in earlier parts of the film–flashes like the hand on the bed–become externalized in her confession. Again, though, we get Resnais’s version of “disorder.” For one thing, her Nevers story isn’t given in a block, but rather as a burst of fragments. After their second lovemaking, she had already begun to tell her lover about her affair with the German, and the editing was rather choppy: six alternations of past and present in about seven minutes. Now at the Tea Room she’s more explicit about his fate and her punishment. Over twenty-four minutes, the action alternates between Hiroshima and Nevers seventeen times. Often a single shot breaks into her confession.

For another thing, the incidents remembered tumble out of order. Glimpses of her imprisoned in a basement are followed by her ritual haircutting before being sent there. Image and sound fall out of true: we see her pedaling to Paris, we hear her telling us what she read in the newspapers upon arriving. We need to integrate what she’s recounting now with what she’s recalled earlier.

By the time the couple leave the Tea Room, we have a fairly coherent account of the woman’s Nevers trauma. In our alternative film, we’d now have a climax in which she decides to leave Hiroshima or stay. Instead, she and the man separate. She returns to her hotel, washes her face, accuses herself of betraying her German lover with the Japanese, and. . . wanders back outside.

She returns to the Tea Room, now closed. The plot’s irresolution is prolonged. Her lover materializes, as if summoned by her voice-over. The woman, now distraught, tells him she’ll stay. Immediately she tells him to leave. He says he could never leave her. Then he leaves her.

What follows is a string of further evasions and encounters, almost a suite of variations on how a couple can seek to connect and avoid connecting. The film becomes a walkie. Resnais planned the street scenes, he explained in a letter to Duras, by listening to a tape of her reading the commentary and blocking the actors’ movements with wooden dolls.

The woman moves down the street, trailed by her lover. He follows her to a train station, and then to a bar called–you must remember this–Casablanca. She eludes him by letting a slick stranger join her for a drink. The night goes on. Dawn arrives.

In the course of these stop-and-start ramblings, memories return, but images of her lover dwindle, to be replaced by those of Nevers; he has faded into the landscape. As I indicated, these might as well be narrational commentary rather than her memories, with the film’s overarching form juxtaposing the French city with the Japanese one in ways she doesn’t yet grasp.

Now you know why people say art movies seem never to end: They tease us with closure and then deny it. Extended talk scenes and walk scenes, however realistic they may seem in contrast with busy Hollywood plots, are also conventions of this mode of filmmaking. It’s up to the filmmakers to shape them to their immediate purposes.

(4) At the limit

In a plot centered on action–goals, blockages, clashes among characters, struggles to accomplish some feat–you typically have a clear-cut climax and resolution. The protagonist either succeeds or fails. But when you deny that sort of arc, you have to find other ways to inject drama. In Hiroshima, we have a classic instance of the undecided protagonist, who can’t settle on a goal and so drifts from situation to situation, each one of which dramatizes a facet of her character, or of her indecision.

Sooner or later, the plot has to stop, so if there’s no decisive way to end the action, how do you conclude? The most favored option, borrowed from serious literature, involves what literary theorist Horst Ruthrof calls a “boundary situation.” Instead of creating a resolution by what the protagonist accomplishes, the plot confronts the character with something that forces a reevaluation of his or her life. The drama is psychological, not physical; the resolution involves insight, not action of the normal sort. As Ruthrof puts it, the character “in a flash of insight become[s] aware of meaningful as against meaningless existence.” The boundary situation is existential, consisting of “a final vision or revelation, rejection of false moral premises, and the gain of a state of authenticity.”

James Joyce called such bursts of recognition “epiphanies,” and he employed them in his Dubliners short stories. Ruthrof argues persuasively that they can be found throughout modern European literature, from Flaubert and Tolstoy to Conrad and Thomas Mann. In Narration in the Fiction Film, I proposed that many films in the European tradition had recourse to boundary-situation plots. Guido’s acceptance of all the contradictions of his life in 8 ½ and Isak Borg’s reconciliation with his past in Wild Strawberries are fairly clear examples.

Instances of boundary situations are central to two Marguerite Duras novels of the period. The Square (1955) consists of routine encounters on a park bench between an unnamed man and woman. They talk at length each time, and the climax comes when the man declares suddenly, “I’m a coward.” Moderato Cantabile (1956) is set in a cafe, and the conversations are broken by time shifts to piano lessons and a party. Again we get laconic exchanges between a man and woman who don’t know each other, culminating in confession and tears. (“I wish you were dead.”/ “I am.”) Resnais said that he wanted to work with Duras after reading Moderato Cantabile.

In Hiroshima, what, finally, provides closure for the plot? Not the woman’s decision to stay or not; we never know what she chooses. Instead, her affair has forced her to psychological crisis. She realizes that her memories of her first love are partial and impermanent. This shocks her as an act of disloyalty. And she feels that she’s already forgetting her Japanese lover. The passage of time and the waning of emotion come to feel like a betrayal.

The film’s climax is a personal epiphany, not a clear-cut showdown. The woman has come to accept that her past and present are ephemeral, that even the memories she’s making now–of the lover whose skin she adores–will wane. What remains? The late sequences that take her wandering through his city cement the relation between his body and the town: her voice-over repeats the exultant incantation that opened the film, but now we hear it over shots of neon signs and empty streets. So she can name the man: “Hiroshima.” And although we have never had privileged access to his mind, the fact that he rejoiced in hearing her story of her past, in being the only person she had told of it, he may well have achieved a similar epiphany. He reciprocates, calling her “Nevers. Nevers in France.”

This is of course just one interpretation. Whatever thematic implications a critic constructs from the film, though, I think that those will depend on acknowledging the transformative boundary situation that functions as a climax. The woman’s confrontation with the man and the city has forced her to a self-recognition, putting her life in a new light.

Cinema of character rather than plot, we sometimes call it. I’d rather say it’s a particular breed of plot, one that replaces achievement of external goals with achievement of partial, tentative, but still life-transforming insight. A different dramaturgy for a different tradition.

(5) Consolidating innovations

Voyage to Italy; La Pointe Courte.

Hiroshima mon amour changed the way movies told their stories, not least because it revised some trends that had emerged in two other European films of the 1950s.

One was Roberto Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy (released late 1954). Despite featuring two major American stars, Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders, it was far from an ordinary Hollywood picture. It pushed further that conception of “plotless,” anecdotal narrative on display in Neorealist films like Paisá and Umberto D. The center of the tale is a couple whose marriage is quietly dying. Having inherited a villa in Naples, the characters must decide to sell it. But instead of building a conflict out of this goal, the film fills itself with episodes of the husband’s philandering and the wife’s touring of the region. It settles its plot by an epiphany in which man and wife are mysteriously reconciled.

Voyage to Italy, wrote Jacques Rivette, “opens a breach. . . . All cinema, on pain of death, must pass through it.” “The story is loose, free, full of breaks,” said Eric Rohmer, “and yet nothing could be further from the amateur. I confess my incapacity to define adequately the merits of a style so new that it defies all definition.” Rivette again: “Here is our cinema, those of us who in our turn are preparing to make films (did I tell you, it may be soon).”

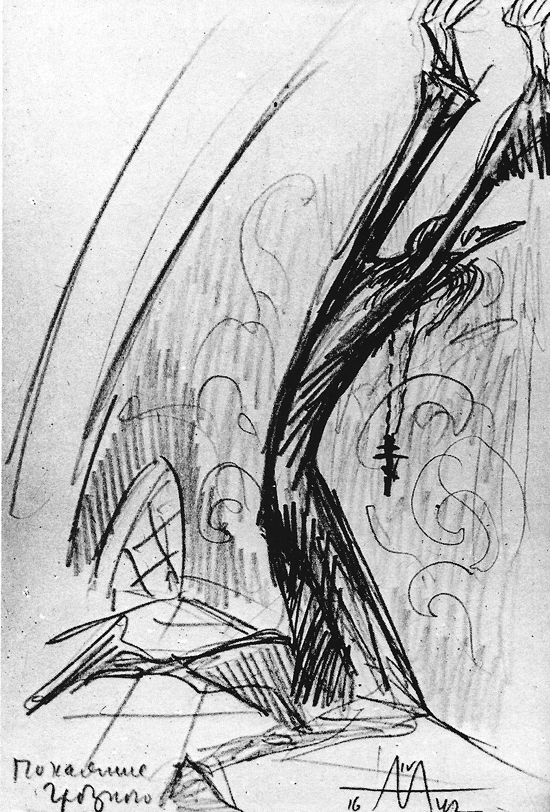

The Cahiers du cinéma critics weren’t so eager to welcome Agnès Varda’s La Pointe Courte (1956). A married couple drifts through a fishing village, and their meditations on their life together are woven into documentary recording of the locals’ work and relaxation. André Bazin championed the film, but others in the Cahiers team were cool, objecting to the stylized photography and performances. The fact that it was made by a woman probably didn’t help. Against Varda’s wishes Cahiers ran a photo of her as a martyred angel, and it’s hard not to see it as mockery, especially since the caption revels in Henri Agel’s “wicked manhandling” of the film in his review.

Because La Pointe Courte was produced by a company registered to make only short films, it couldn’t achieve commercial distribution and so circulated mostly to ciné-clubs. But most reviews were praising, and today it’s recognized as a bold anticipation of the Nouvelle Vague.

Among those films that La Pointe Courte anticipates is Hiroshima. Resnais, was editor on La Pointe Courte. He initially resisted the job, telling Varda: “Your explorations are too close to mine,” but he wound up working for free.

Three films about couples, then, rendered in a strikingly episodic way. All use long walks and extended talks. All three display a dual structure as well. Rossellini intercuts the activities of husband and wife. Varda, influenced by the parallel structure of Faulkner’s novel Wild Palms, alternates scenes of village life with the couple’s wanderings. And as we’ve seen, Resnais asked Varda to build Hiroshima upon an editing strategy that set the past against the present.

There are probably other antecedents of the film (Resnais was reminded of Il Grido when cutting La Pointe Courte), but I hope I’ve said enough to indicate how Resnais recasts an emerging tradition of ambitious European cinema. He goes beyond it in all the ways I’ve mentioned and more I haven’t, but like all art works it owes part of its power to its reworking of techniques it inherits.

We could list more reasons that this film endures, certainly. Not least: Its unforgettably enigmatic title. Even that offers us ambiguous fragments, in something like an abrupt cut. “Hiroshima mon amour” might suggest “I love the city of Hiroshima.” But there’s no punctuation, no comma or dash that would equate the two terms. Instead, we might take it as a splice. It might be a contrast: “Hiroshima” versus “my love, the German soldier.” But then, since the Japanese comes to stand in for the German, the title would equate “Hiroshima” to him. This would be consistent with the final dialogue: “Hiroshima, that’s your name.” The film’s very title implies the ambivalent juxtapositions that Resnais will build up through cutting.

Thanks as ever to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and their colleagues at Criterion for making this installment. Thanks as well to old friend Erik Gunneson and to Kelley Conway for discussion of Resnais and Varda. Our entire Criterion Channel series is here.

Bazin’s worries that montage lacked ambiguity are set forth in various essays in What Is Cinema? vol. I, ed. and trans. Hugh Gray (University of California Press, 1967), particularly “The Evolution of the Language of Cinema,” 36.

Resnais’s comments about Hiroshima‘s avoidance of flashbacks are quoted in Jean-Louis Leutrat, Hiroshima mon amour, 2nd ed. (Armand Colin, 2006), p. 84. He describes his film’s “disorder” in conversation with Anatole Dauman, quoted in Jacques Gerber, Souvenir-Écran: Anatole Dauman, Argos Films (Pompidou, 1989), 86-87. He mentions his use of puppets to plan his staging in a letter reprinted in Tu n’as rien vu à Hiroshima, ed. Marie-Christine de Navacelle (Gallimard, 2009), 66. This lovely edition shouldn’t be confused with Tu n’as rien vu à Hiroshima!, ed. Raymond Ravar (Brussels: Institut de Sociologie, Université Libre de Bruxelles, 1962). This remarkable volume is a detailed book-length analysis of the film and includes interviews with Resnais.

Horst Ruthrof’s discussion of boundary situations appears in The Reader’s Construction of Narrative (Routledge, 1981), 101-108.

See Cahiers du cinéma: The 1950s: Neo-Realism, Hollywood, New Wave, ed. Jim Hillier (Harvard University Press, 1985), 192-208, for Rivette and Rohmer on Voyage to Italy. The macho mockery of Varda occurs in Cahiers no. 56 (February 1956), 29. For a comprehensive discussion of La Pointe Courte, see Kelley Conway, Agnès Varda (University of Illinois Press, 2015), 9-26. We consider Kelley’s book and Varda’s film here

In Narration in the Fiction Film, I argue that the ambiguous interplay of objective realism, subjective projection, and external narrational commentary is a major strategy of “modernist” cinema or “art cinema.” That argument is sketched in an earlier essay available here, with an update. See also the blog entry, “How to watch an art movie, reel 1.”

I played awhile with the idea that the floating voice-overs in the opening sequence might have been Duras’s efforts to capture what Nathalie Sarraute described as sous-conversation, the unarticulated subtexts that shape what we actually say. The historical timing fits, as Sarraute’s essay positing the possibility, “Conversation and sous-conversation,” appeared in early 1956. (See Sarraute, The Age of Suspicion: Essays on the Novel, trans. Maria Jolas, Braziller, 1963). But I’m not fully convinced of a direct debt. More generally, though, Sarraute’s insistence that the contemporary novel must replace external action with dialogue that hints at internal states seems in accord with the way Duras and Resnais conceived Hiroshima. Maybe here the image track does duty for Sarraute’s “subterranean conversation”? And perhaps the idea of sous-conversation is more relevant to Duras’s own films, particularly the masterpiece India Song (1975).

Hiroshima mon amour.

The camera as perpetual motion machine: Jeff Smith on BREAKING THE WAVES

Jeff Smith’s analysis of von Trier’s film has been posted on our series on the Criterion Channel of FilmStruck. Here, as is his custom, he offers more insights into this extraordinary work.

I still remember the shock I felt watching Lars von Trier’s Breaking the Waves for the first time. Some of it was undoubtedly a response to the film’s emotionally unsettling narrative. Yet I also wasn’t quite prepared for the caught-on-the-fly quality of Robby Müller’s handheld cinematography.

Was this the same director who had created such striking, high-contrast, black and white images for Zentropa?

Was this the same Robby Müller who composed the austere, yet stylish landscapes shots in Kings of the Road, Paris, Texas, and Down by Law?

In contrast to the very controlled look of those titles, the prologue to Breaking the Waves establishes a more muted visual style. Interior spaces look washed-out and the color is drained from the beautiful Scottish landscape. This effect was created by shooting on 35mm, scanning the negative to video, and transferring the altered footage back to film.

The camera also moves constantly. It anxiously follows action as it unfolds to capture a sense of both intimacy and immediacy. In Zentropa, the actors mostly were subsumed into the overall visual design of the image. In Breaking the Waves, the specific choices in editing and cinematography were subordinated to the actors’ performances. For Trier, this choice was partly dictated by the material. He wanted to preserve a sense of existential mystery about the film’s events. The decision to shoot in a raw, naturalistic style was necessary to keep the film believable.

Breaking the Waves also laid down a marker in terms of von Trier’s commitment to the dictates of the Dogme 95 manifesto. Although the film departs from those principles in significant ways, it previews the even nervier approach von Trier takes in The Idiots.

Yet elements of pictorial stylization are retained in Breaking the Waves, and they foreshadow the formal tensions that characterize much of von Trier’s later work. In Dancer in the Dark, the juxtaposition of stylization and naturalism is evident in the way Bjork’s musical numbers provide escape from the grim misery of Selma’s daily existence. Antichrist opens with luminous black and white imagery in super-slow -motion that directly contrasts with the slightly more desaturated color seen in the rest of the film.

Melancholia begins with fantastic, colorful, almost still tableaux accompanied by an excerpt from Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde. This differs markedly from the rest of the film which is shot in the semi-documentary style seen in Trier’s Dogme work.

In what follows, I trace the way Breaking the Waves’ dialectic between naturalism and stylization is expressed in particular visual motifs. I also show how these techniques reinforce some of von Trier’s larger thematic concerns. Warning: some spoilers ahead.

Camera playing catchup

Robby Müller’s handheld cinematography in Breaking the Waves fulfills a number of different objectives. First and foremost, the constant, restless movement adds a visual dynamism that contrasts with the locked-down camera frequently seen in “slow cinema.” Secondly, the association of this style with documentary adds a jolt of authenticity to the scenes of Jan aboard ship and the various emergencies that occur at the hospital. Lastly, the “caught on the fly” quality of the images lends a sense of intimacy and immediacy to the character’s interactions.

Breaking the Waves’ most common technique involves the use of rapid pans to convey a feeling of imminence–the sense of pushing us toward what is just about to happen in the scene. Those anticipatory pans pans serve a number of storytelling functions.

They’re often used during dialogue scenes as a variant of more conventional shot/reverse shot techniques. In the hospital, when Bess and Dodo discuss Jan’s sick fantasies, the camera swivels between the two speakers some eight times.

The entire conversation is handled in five longish takes instead of the dozen or so shots we’d get if von Trier had used shot/reverse shot.

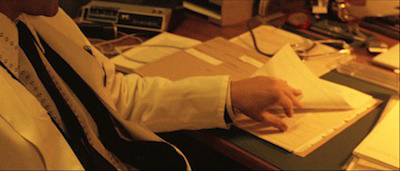

More commonly, von Trier’s dialogue scenes use quick pans to capture another character’s reaction before then cutting back to the other speaker. Near the midpoint of Breaking the Waves, we see Richardson rifling through the pages of Bess’s file. Richardson asks Bess about her care under another doctor. The camera swings swiftly over to Bess who professes ignorance of this prior episode.

The camera then pans back to Richardson.

He acknowledges that her treatment was related to her brother’s death before von Trier eventually cuts back to Bess. Given the emphasis on performance during shooting, these panning movements keep the actors in the moment, enhancing the impression of dramatic intimacy and visual energy. But the style also enables Trier to shoot coverage so that he can select between different takes during editing.

In some instances, these rapid shifts from one character to another preserve the interactions of the ensemble within a single take. This occurs, for example, as the wedding party reacts to the sudden appearance of rain. We see it again later when Jan and his buddies pass around a flask of booze.

In still other cases, these rapid pans enhance the dramatic impact of eyeline matches. The viewer is often cued to these moments by a character’s glance offscreen and their facial expression. The camera then pivots to reveal what is in the offscreen space. A fairly early instance of this is when Dodo returns to Bess’s house to find her sitting quietly and Bess’s mother asleep.

Later Trier uses Bess’s glance offscreen to cut during a whip pan to a rabbit on the side of the road.

The moment serves as counterpoint to what we’ve just seen. Bess has vomited in disgust after a sexual encounter on a bus. The way she wrinkles her nose at the bunny reminds us of her childlike naiveté.

The panning motif pays off during the inquest into Bess’s death. Dr. Richardson testifies that Bess died because of her inherent goodness. Unsurprisingly, this claim is met with skepticism from the magistrate presiding over the hearing. Von Trier then cuts to a close-up of Dodo.

The camera tilts down and pans right as she grasps someone’s hand. It then tilts back up, to reveal Jan seated next to her.

The revelation comes as a bit of surprise because Trier has omitted the narrative action that connects the hospital scenes to the hearing. As mysterious as Bess’s death is, Jan’s recovery prompts even deeper questions. How is it that Jan survived when it appeared that his own death was imminent? More pertinent, how was his paralysis cured? In exploring the nature of the miraculous as part of the everyday, von Trier presents us with an enigma that he refuses to explain. It is here that we first begin to grasp the meaning of Bess’ religious faith and the impact of her self-sacrifice.

Are you there, God? It’s me, Bess.

Another important visual motif involves the long takes used for Bess’ talks with God. For the most part, Breaking the Waves’ average shot length is relatively short. But Trier sets off these moments of prayer by shooting them in a markedly different style.

More often than not, Müller’s camera photographs Bess in close-up or medium close-up to focus our attention on her face. Emily Watson uses the simplest of means to indicate the two sides of her dialogues with God. She shifts her gaze either upward or downward and changes her style of speech. Notably, in a suggestion of the degree to which Bess has internalized the church’s doctrines, her vocal impersonation of God sounds uncannily like one of the church elders.

These shots of prayer often unfold in real time lasting a minute or more. Their duration and more static framing convey both a sense of intimacy and important information about Bess’ motivation. Her imagined conversations with the heavenly father help to explain her actions in what would otherwise seem like wildly improbable changes in character.

These scenes also invite the viewer to consider Bess’ mental stability. Because of her childlike nature, Bess’ belief that God talks directly to her initially seems delusional. Yet, as the film goes on, Bess’ devotion to both God and her husband introduces the possibility that her actions are divinely inspired. By demonstrating her selfless love for Jan above all else, including her own safety, von Trier suggests that Bess’ sacrifice might be the reason for Jan’s recovery.

Or it could all just be a coincidence. Jan’s recuperation might not have any explicable cause, either physical or spiritual.

An energetic but casual style: raw immediacy as studied nonchalance

Throughout much of Breaking the Waves’ running time, von Trier’s narration seems to be rather communicative. The relentless camera movement and frequent cutting suggest a desire to capture the story as it unfolds and to transmit the most narratively salient material.

At key moments, however, the film’s visual techniques prove surprisingly reticent. Significant plot developments are sometimes handled in an offhand fashion. This strategy seems to be an extension of von Trier’s interest in making the film’s melodramatic narrative seem plausible. (Indeed, Breaking the Waves plays as a sort of Magnificent Obsession for the art film crowd.) More than that, though, this restraint also encourages viewers to form their own conclusions about the events depicted.

Consider Jan’s observation that Bess has blood on her wedding dress after consummating their marriage in the bathroom of the reception hall.

Another director would likely cut to an insert from Bess’s pov to underscore this image. It would serve as a symbol of her loss of innocence and as a grim foreshadowing of her ultimate fate (i.e. love as a form of blood sacrifice). But Trier refuses to force that interpretation on the viewer. Instead, by showing Bess calmly rinsing out the stain, von Trier allows the moment to resonate more organically.

This motif reaches a kind of apotheosis in the shot of Jan standing on crutches at Bess’s gravesite. The whole story has built toward this moment. Yet Trier treats it in a pointedly cursory fashion. Jan is photographed in long shot. The camera’s distance mollifies the character’s evident grief and refuses the viewer the kind of emotional catharsis we commonly associate with such rituals.

Jan’s silence also preserves the sense of mystery about how this turn of events occurred. Is Jan’s ability to walk evidence of the hand of God? Perhaps. Yet it might also be seen as a kind of cosmic joke, proof that humanity’s existence is ruled by forces of Kierkegaardian absurdism.

Rendering the kitsch sublime

Breaking the Waves’ most striking shots appear in the film’s chapter titles. Von Trier worked with the artist Per Kirkeby to create these images using fairly simple computer animation tools. Early in the production, they were described as merely panorama shots. But as the work developed, Trier described them as natural landscapes that evoked the Romantic tradition. This picture-postcard imagery is simultaneously both beautiful and banal, sublime and kitschy.

These more conventionally picturesque shots are further differentiated by Trier’s use of music. Each chapter title is accompanied by a different seventies classic: Elton John’s “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road,” Mott the Hoople’s “All the Way to Memphis,” Procol Harum’s “A Whiter Shade of Pale,” and David Bowie’s “Life on Mars.” The combination of music and saturated color enable these proleptic titles to function as the antithesis of the film’s handheld camerawork. As Kirkeby himself explained, they contrasted with Müller’s “tropistic intimacy.”

By using these titles to structure the narrative, von Trier preserves the opposition between naturalism and stylization until Breaking the Waves’ final shot. After Jan and his pals give Bess an impromptu burial at sea, they awaken the next morning to the sounds of bells ringing. We know from the scenes of Jan and Bess’ wedding that the source of the sound can’t be the church. Rather miraculously, the bells ring in the clouds unmoored from any terrestrial structure.

Von Trier denies us narrative closure by refusing to explain the meaning of Bess’ actions. But he gives us a kind of formal closure by synthesizing within a single image the different styles of cinematography seen throughout Breaking the Waves.

A riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma

Breaking the Waves has always fascinated me as a study in contradictions. The film is about a miracle, but it is rendered in a style that seems wholly naturalistic. The cast was encouraged to improvise to create the desired sense of spontaneity. Yet Stellan Skarsgård reported that the actors mostly stuck to the script because the dialogue was so good as written. The plot hinges on an answered prayer, but the outcome is such a cruel twist of fate that it leads the viewer to doubt the nature of divinity entirely.

Even the central characters are defined by contradictions. Jan is a worldly outsider whose passions and joie de vivre raise the hackles of the strict Calvinist community where the principal actions take place. Bess was raised inside this overtly patriarchal structure, but she displays such childlike innocence that the inherently sinful nature of humanity somehow eludes her. Only von Trier would make a film in which a character’s adultery and debauchery are construed as holy acts of spiritual self-sacrifice. Bess might seem like a secular saint. But her sainthood is achieved by almost completely abasing herself.

This sense of contrast and contradiction also extends to Trier’s sources for Breaking the Waves. Much of the inspiration for Bess came from a children’s book entitled Gold Heart. The title character is a young girl who enters the woods with bread and other foodstuffs in her pockets. By the end of her journey, she is left naked and empty-handed. Her innate goodness and generosity makes her vulnerable, almost to the point of self-destruction. To quote von Trier, “Gold Heart is Bess in the film. She is goodness in its most absolute gestalt.”

At the other end of the cultural spectrum, though, von Trier incorporates ideas drawn from the films of his Danish predecessor, Carl Theodor Dreyer. The original title of Breaking the Waves was “Love is Everything,” the aphorism that Gertrud’s protagonist wanted as her epitaph. The basic dramatic situation is also reminiscent of Ordet. Like Inger, Jan is bedridden and near death. Like Johannes, Bess is the holy fool whose insistence on faith acts as a counter to science and rationality. And as in Dreyer’s work (La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, Day of Wrath) a woman’s decisive actions put her at odds with a community steeped in religious dogma.

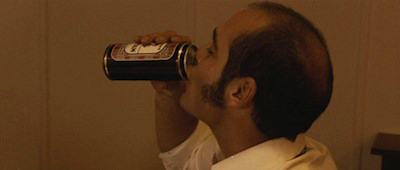

Breaking the Waves accent on contrasts is perhaps best epitomized in one of the film’s lighter moments. During Jan and Bess’s wedding reception, Terry and the Chairman of the church elders chug their beverages.

A close-up shows Terry crushing his beer can in an homage to a similar contest of machismo in Jaws.

It takes a rather dark turn, however, when the Chairman breaks the glass he’s holding with his bare hand.

Although the scene is a bit of a throwaway, it in many ways epitomizes the tonal shifts that mark von Trier’s work as a whole. All of his films contain moments of bleak humor, episodes where laughter slightly obscures the stories’ violent undertones and dark menace. To quote the spirit animals in Antichrist, “Chaos reigns” in the von Trier universe. And whether it is death, nightmare visions, or the literal end of the world, the prototypical von Trier hero confronts this chaos mindful of the immense absurdity of the inexplicable.

Thanks to Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, Peter Becker, and the whole Criterion team for their superb work on the video. A complete list of our FilmStruck installments is here.

Several different editions of Breaking the Waves have been released on home video. I recommend the Criterion dual-format edition. As one would expect, it contains lots of goodies in the extra features. These include deleted and extended scenes, interviews with Emily Watson and Stellan Skarsgård, and selected-audio commentary by von Trier, editor Anders Refn, and location scout Anthony Dod Mantle.

The published screenplay from Faber & Faber includes introductory essays by von Trier, artist Per Kirkeby, and Swedish film critic Stig Björkman.

Collections of interviews with Denmark’s enfant terrible can be found here and here. There’s also a good online interview with von Trier about Breaking the Waves.

The quote from Stellan Skarsgård can be found at Mental Floss.

I also want to thank the film faculty at the University of Copenhagen and Lars von Trier himself. I had the rare privilege of hearing the director discuss his work after a special screening of Antichrist that was arranged for attendees of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image conference in 2009. I learned a lot from the experience, especially about von Trier’s fondness for mixed pictorial styles within his films.

Breaking the Waves (1996).

FilmStruck goes to THE DEVIL: A guest post by Jeff Smith

The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941).

Jeff here:

Last week, the latest in our series of “Observations on Film Art” videos dropped on FilmStruck. The topic this time was continuity editing in The Devil and Daniel Webster.

Many of our faithful blog readers are surely familiar with the techniques and devices that make up the continuity system. The video is really intended to be a primer for the uninitiated. It illustrates some of the basic formal elements of classical continuity, such as the eyeline match, shot/reverse shot, and the 180° rule.

In the video, I tried to highlight some of the reasons why the continuity system became common among popular cinemas around the globe. The tacit principles of the continuity system help ensure that:

- the story’s dimensions of space and time are clearly communicated to the audience

- characters’ and objects’ positions remain relatively constant from shot to shot

- that eyelines and screen direction stay consistent

- the spectator’s attention is guided to the most salient details in a scene.

The last may be the most important, if least understood. Several perceptual psychologists argue that one of the things that makes cinema a unique art form is its ability to produce attentional synchrony among viewers.

Editing is not the only means of guiding attention, to be sure. Filmmakers use lighting, composition, figure movement, camera movement, and blocking to nudge us to look at particular areas of the frame. The continuity system, though, further harnesses these shifts of attention by yoking them to the timing of cuts. Cuts are often coordinated with natural attention cues in a scene, such as conversational turns, changes in where the characters look, and pointing gestures. As Tim J. Smith, Daniel Levin, and James E. Cutting put it, “By piggy-backing on natural visual cognition, Hollywood style presents a highly artificial sequence of viewpoints in a way that is easy to comprehend, does not require specific cognitive skills, and may even be perceived by viewers who have never watched film before.”

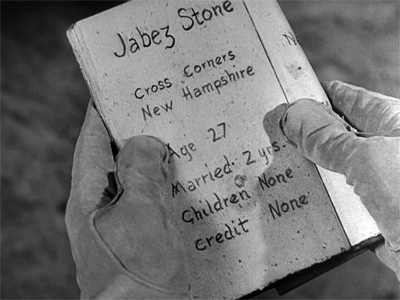

In its deployment of classical Hollywood editing techniques, The Devil and Daniel Webster doesn’t do anything particularly special. Rather, in telling the story of how a New Hampshire farmer, Jabez Stone, sold his soul to the devil, it beautifully illustrates the clarity and efficiency of Hollywood craft at the height of the studio era. Indeed, the editing epitomizes the style of director William Dieterle as a whole: simple, direct, no fuss, no muss.

That being said, The Devil and Daniel Webster does add a few wrinkles to the usual Hollywood style. For example, it uses “trick film” techniques dating back to the era of George Melies to highlight the magical powers of the diabolical Mr. Scratch.

When Jabez throws an axe, it is initially seen as a blur heading straight for Scratch’s head.

A combination of stop-motion substitution and rear projection shows the axe freeze in midair.

A traveling matte is then used as the axe bursts into flames.

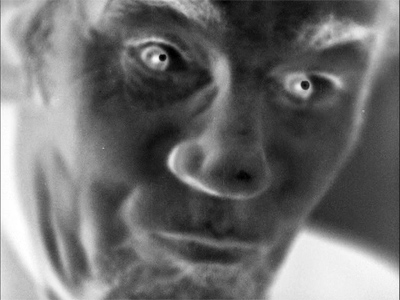

Moreover, the Criterion DVD contains deleted scenes from an earlier preview version of the film titled Here is a Man. This alternate version was, in fact, more formally adventurous than the one commonly seen by contemporary audiences. Each time something bad befalls Jabez during the first 20 minutes of the film, Here is a Man cuts to a few frames of photographic negative of Scratch. For instance, when Mary accidentally falls off a wagon, Dieterle cuts to Walter Huston smugly pursing his lips.

Dieterle and his collaborators wisely removed these shots from the final version of the film. The opening scene shows Scratch with Jabez’s name in a small book he carries with him.

When ruinous things start happening to Jabez, viewers naturally infer that Scratch caused them. The oddball moments in Here is a Man, unlike the other effects shots, don’t really add any new information and are heavy-handed in their symbolism.

The Long and the Short of It: Adapting Stephen Vincent Benét to the Silver Screen

Beyond offering good examples of editing craft, The Devil and Daniel Webster is of interest today for other reasons. One involves some of the creative choices made by Stephen Vincent Benét and Dan Totheroh in adapting the former’s short story, first published by The Saturday Evening Post in 1936. The second issue I’ll explore has to do with the way the film speaks to political issues of its moment. It seems endorse a collectivist vision of society as a counter to the excesses of unrestrained capitalism.

Most film adaptations use books for their source material, and most screenwriters face the challenge of condensing the book’s narrative to fit the running time of a typical feature film (roughly about two hours). In the case of The Devil and Daniel Webster, Benét and Totheroh faced the opposite problem.“The Devil and Daniel Webster” runs less than twenty pages in a Hythloday Press collection of Benét’s short stories. So how do you stretch Benét’s relatively slim tale to fit a 107 minute running time? Benét and Totheroh did what most screenwriters do when they confront the same dilemma. They add incidents, invent new characters, and develop new subplots, adding this material to the existing story spine.

Some print editions of Benét’s story break it into five parts with each new segment introduced with a Roman numeral. Part I introduces Daniel Webster via the tall tales told about him in the New England area. It also provides exposition to Jabez’s blighted existence, and the deal he makes with the devil. After breaking his plow on a stone, Jabez angrily proclaims, “I vow it’s enough to make a man want to sell his soul to the devil. And I would, too, for two cents!”

Part II covers the seven-year period of prosperity Jabez enjoys as well as his interest in contesting the mortgage held by the mysterious stranger. This section also establishes the stranger’s mystical powers as Jabez hears the voice of his neighbor, Miser Stevens, coming from a moth-like creature that the stranger captures in a bandanna.

Part III describes Jabez’s recruitment of Daniel Webster for his defense and the preparations for trial. Parts IV and V depict the trial itself. The former introduces the judge and jury, and portrays Daniel’s passionate defense of Jabez. The latter tells of the jury’s verdict and Daniel’s banishment of Mr. Scratch from New Hampshire.

One of the most striking things about Benét’s original story is how much of it focuses on the trial itself. Approximately half of the story covers Webster’s initial deliberations with Mr. Scratch, his demand for a trial, and the legal proceedings. In contrast, these story events account for less twenty percent of the film’s running time.

In expanding the story to feature length, Benét and Totheroh add new incidents, characters, and subplots to the early and middle sections of the screenplay. Consider, for example, Benét’s economy in his prose description of Jabez’s misfortunes:

If he planted corn, he got borers; if he planted potatoes, he got blight. He had good-enough land, but it didn’t prosper him; he had a decent wife and children, but the more children he had, the less there was to feed them. If stones cropped up in his neighbor’s field, boulders boiled up in his; if he had a horse with the spavins, he’d trade it for one with the staggers and give something extra.

Years of toil and trouble for Jabez are compressed into three sentences. When Jabez breaks his plowshare, it becomes simply the proverbial straw on the camel’s back, coming at a time when his wife and children are sick and even his horse has a rheumy cough.

In their script, Benét and Totheroh create a handful of new vignettes to illustrate Jabez’s rotten luck. In the film’s first scene, Jabez’s pig breaks its leg after being chased by the family dog. Later, Jabez’s wife, Mary, takes a tumble off their wagon when trying to stop her husband from selling the family’s calf. Still later, a fox gets into Jabez’s henhouse. In the film, Jabez’s breaking point comes not with the plow, but after he spills precious seed in a puddle just outside his barn. Unlike the story’s description of blight and corn borers, these brief episodes not only visualize Jabez’s tribulations, but also contain their own short dramatic arcs.

Another way Benét and Totheroh expand the original story is to add depth and specificity to its secondary characters. In the original, Miser Stevens never appears as anything more than an insect that’s escaped from Scratch’s collecting box. In the film, he is much more fully fleshed-out character, especially as embodied by the wonderful character actor, John Qualen.

Benét and Totheroh’s screenplay uses Stevens to create important story parallels. Like Scratch, who possesses a mortgage on Jabez’s soul, Stevens holds the mortgage to the Stone farm. Yet, Stevens also has made a Faustian bargain with Mr. Scratch. His death at Jabez’s party lingers over the rest of the film, a vivid reminder of what’s at stake during the trial.

Benét’s story also treats Jabez’s wife and children quite impersonally. The characters are never named. The references to them mostly add narrative weight to Jabez’s sense of burden. In contrast, the film version not only give these characters names and individual traits, but also uses them to highlight changes Jabez undergoes once he becomes a wealthy landowner. Jabez and his wife, Mary, frequently argue about disciplining their son, Daniel. Jabez indulges Daniel, spoiling him but offering little in the way of love. Similarly, after becoming successful, Jabez also falls short of what we’d expect of a caring husband.

In the middle parts of the film, Jabez becomes crueler and harder. He starts treating trespassers on his land more harshly. He even fires a weapon at one in an effort to scare him away. His anti-social attitudes make him an outcast among the citizenry of Cross Corners.

As was the case with Jabez’s family, the film gives the townspeople more life and personality. Early on, they serve to motivate Daniel Webster’s presence in the story, welcoming him to Cross Corners and serving as a receptive audience for the Senator’s political views. Later, the townspeople act as a foil for Jabez, establishing an important thematic contrast between his laissez faire mindset and their more communitarian values.

Lastly, Benét and Totheroh also invent several new characters for the film adaptation. Of these, the most important is Belle. Loosely allied with Mr. Scratch, Belle is ostensibly Daniel’s nanny, but is implied to be Jabez’s mistress. Belle supplies a sexual temptation not present in the original story, and this complements the temptations of wealth and power. In this respect, the character anticipates the femme fatales found in the cycle of films noir that appear later in the forties, especially as played by Simone Simon at her most fetching.

Although Dieterle was best known for costume pictures rather than film noir, the photographic style of The Devil and Daniel Webster sometimes displays the kind of dark, moody look we associate with noir’s Germanic influence. Consider, for example, the shot of Scratch’s entrance into Jabez’s barn. The mists, the backllight, and the gnarled tree in the background all foreshadow the darkness that will soon take hold of Jabez’s soul.

In the case of The Devil and Daniel Webster, tracing the film’s lineage back to German expressionism is fairly easy. Prior to becoming a director, Dieterle was an actor in dozens of German silent films, including F.W. Murnau’s Faust (1926). Murnau’s adaptation of Goethe’s play not only shares its narrative conceit with Dieterle’s film, but is also one of the most strikingly photographed of his twenties masterpieces.

Looking both backward and forward, The Devil and Daniel Webster might seem like a link between German Expressionism and American film noir. Like German films of the 1910s and 1920s, Dieterle’s film contains some of the fantasy elements found in canonical titles like The Student of Prague (1913), Der Golem (1915), or The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920). Dieterle’s curious afterlife fantasy Six Hours to Live (1932), discussed in an earlier entry, has a strong affinity with Gothic and Expressionist imagery. Like films noir of the forties, the cinematographic style of The Devil and Daniel Webster captures the story’s dark, fatalistic tone.

Indeed, the look of the final trial scene displays the same sort of stylization seen in the dream sequence of The Stranger on the Third Floor (1940), a film often seen as a key noir progenitor.

Still, Dieterle also retains the folksy Americana that was an appealing part of Benét’s original story. Some of the characters, like Ma Stone or Squire Slossum, seem like they’ve wandered into the story from one of Frank Capra’s small towns or John Ford’s rural comedies. This combination makes The Devil and Daniel Webster a true original. Indeed, it might count as an almost singular example of “cracker barrel noir” if the term itself didn’t seem like a complete oxymoron.

Things That Make a Country a Country, and a Man a Man: Benét’s Tale as Allegory

One of the other things that interests me about The Devil and Daniel Webster is the degree to which both the story and the film can be read as allegory. Benét’s original narrative certainly makes American identity a central theme. The opening paragraph proposes that, if you go to Daniel Webster’s gravesite and call his name, you’ll hear his deep, rolling voice ask, “Neighbor, how stands the Union?” Benét adds, “Then you better answer the Union stands as she stood, rock-bottomed and coppersheathed, one and indivisible, or he’s liable to rear right out of the ground.” This description not only foreshadows the oratorical power that Webster will display when Jabez goes on trial, but also the sacrifices Scratch prophesies. These include Webster’s loss of two sons in combat and a missed opportunity to become president.

Later, Webster will challenge Scratch on the grounds of his nationality, saying “no American citizen may be forced into the service of a foreign prince.” Scratch responds that he is an American, and further that he was present for “the first wrong done to the first Indian” and when the first American slave ship set sail for the Congo. Moreover, when Scratch assembles his jury, he selects a group of black-hearted souls whose dark deeds affected the course of the nation’s history. Among them is the pirate Edward Teach, otherwise known as Blackbeard. There’s also Walter Butler, the architect of the Cherry Valley massacre; Simon Girty, who burnt men at the stake; and Governor Thomas Dale, who Benét claims “broke men on the wheel.” Overseeing the proceedings is Judge John Hathorne, a magistrate in Salem who supervised some of the witch trials.

The larger significance of these passages is hard to ignore. Jabez may be on trial within the narrative, but Benét seems to put America itself on trial. The plaintiff and defendant, thus, come to symbolize the yin and yang of America’s soul. Webster represents the virtues that define the American ethos: grit, pluck, ingenuity, and liberty. Scratch, on the other hand, associates himself with the nation’s original sins: genocide, slavery, cruelty, torture, and theocratic inquisition. Webster emerges victorious in the legal battle, but as he says in his summation, our citizens’ hard-won freedom came at a cost of suffering and tribulation. Successes and failures are all part of the great journey of humanity. Says Webster, “And everybody had played a part in it, even the traitors.”

Dieterle’s film preserves all of these elements of Benét’s short story, but adds a couple of wrinkles of its own. First, General Benedict Arnold is added to the film’s panel of jurors, even though he is pointedly absent from the original. In the story, Webster observes that he misses Arnold’s company and is told that the General is engaged in other business. Benedict Arnold is not only fully present in the film version, but is even featured prominently during the trial scene in several medium close-ups.

Webster even singles out Arnold in his impassioned defense of Jabez’s character. Using Arnold’s betrayal of his country as a cautionary tale, the orator asks the jury to give Jabez the second chance that the devil denied to them.

The other, even more important, change made by Benét and Totheroh is the subplot concerned with the formation of the Grange. Officially known as the Order of the Patrons of Husbandry, the Grange was founded in 1867 to promote the interests of farmers and rural communities. But Webster died in 1852. As an addition to the screenplay of The Devil and Daniel Webster, the Grange seems to be a historical anomaly.

So why this anachronistic subplot? The simple answer is that it sharpens the conflict between Jabez and the other townspeople. Not only is he differentiated in class, but he’s set apart by his personal values. The less obvious answer involves the film’s historical context. Released in 1941, the story of a lone holdout resisting the pressure of others in his community likely would evoke broader geopolitical issues. The plea for unity in the face of existential evil would seem to suggest The Devil and Daniel Webster works as an allegorical critique of American isolationism on the threshold of World War II.

Like other allegories, this type of reading follows a pattern of metaphorical substitution. The Grange becomes a stand-in for the Allied Powers. Scratch represents Hitler, Mussolini, Tojo, and other Axis leaders. And, as discussed above, Stone and Webster symbolize America itself.

Dieterle’s earlier career in Hollywood also offers some additional warrant for this interpretation. He was a German Jew who emigrated to the U.S. in 1930. His relocation was less about fleeing the Nazis than it was the opportunity to work for Warner Bros. Still, Dieterle bore witness to the corrosive effects of Nazi ideology, and his directorial assignments show a loose affiliation with anti-Fascist politics. He helmed The Life of Emile Zola, a Warners biopic that depicts the French author’s involvement in the Dreyfus affair. The film won the Oscar for Best Picture in 1938. Thanks to its timely exploration of anti-Semitism, Zola burnished Warner Bros. reputation as Hollywood’s most socially conscious studio.

That same year, Dieterle directed Blockade (1938) for producer Walter Wanger. Although it is mostly a routine espionage thriller, the film is now remembered as one of the few films Hollywood made about the Spanish civil war. As scripted by John Howard Lawson, who later was blacklisted as one of the Hollywood Ten, Blockade is now seen as an emblem of the Popular Front. Most film historians associate it with anti-Fascist politics, even though the film pointedly avoids identifying the Loyalist and Nationalist sides of the conflict.

Unlike these previous projects, The Devil and Daniel Webster positioned Dieterle as both producer and director. The creative decisions involved in the addition of the Grange subplot would seem more directly under his control. The film’s thematic emphasis on collective interests seems to suggest this political subtext in much the same way that Alfred Hitchcock’s Lifeboat (1944) is sometimes viewed as a parable of democracy’s failure in the face of dictatorship.

In highlighting this allegorical dimension of The Devil and Daniel Webster, I don’t wish to suggest that it makes the film inherently more interesting. Indeed, like other allegorical interpretations, it seems a bit reductive and simplistic. More importantly, if taken too far, these types of interpretive strategies quickly become wrongheaded and even silly (i.e. Belle as a stand-in for Vichy collaboration).

Yet, I also can’t help but feel that The Devil and Daniel Webster’s invocation of American identity offers something important to a contemporary audience. If, like me, you bristle every time you hear “American interests” referenced as the reason to abandon the Paris Accords or to potentially withdraw from NATO, then you have a sense of the film’s relevance to our moment.

The whole arc of the Grange subplot seems to invert much contemporary political rhetoric insofar as it dramatizes the social benefits of the Commons and the individual tragedy of self-interest. In the parlance of our times, Jabez is a risk-taker, mortgaging his immortal soul for the promise of earthly riches. Yet, when we see the resulting inequality in Dieterle’s film, we recognize the situation for what it is. For Jabez, Miser Stevens, and other capitalist mountebanks, it is, quite literally, a deal with the devil. And that, consarn it, is a lesson that all modern viewers can take to heart.

A handy introduction to the continuity system can be found in Chapter 6 of Film Art.

To learn more about the role of editing in guiding viewers’ attention, see Tim J. Smith, Daniel Levin, and James E. Cutting, “A Window on Reality: Perceiving Edited Moving Images,” Current Directions in Psychological Science 21, no. 2 (2012): 107-113. A PDF of this essay can be found here.

Stephen Vincent Benét can be found in many places around the web, including here. Lotte Eisner’s The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema and the Influence of Max Reinhardt (1974, University of California Press) remains a useful introduction to the movement’s lighting and visual motifs. For more on the interpretation of films as political allegories, see my book Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds (2014, University of California Press).

The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941).

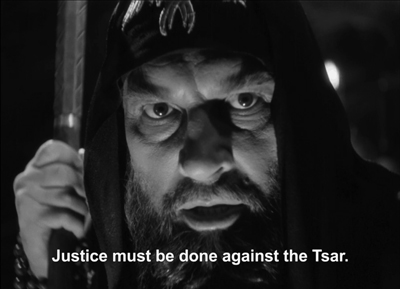

Eisenstein makes a scene: IVAN THE TERRIBLE Part II on the Criterion Channel

For Yuri Tsivian

DB here:

Everyone knows Eisenstein as a theorist and practitioner of something called montage, which in his hands comes to mean a lot of things. But he was no less interested in what he called expressive movement. He believed that the viewer could be aroused by dynamic physical action that carried powerful feeling. Expressive movement pervades the set-pieces of his silent films. On the Odessa Steps of 1925’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), we get the robotic descent of the Cossacks opposed to the agitated flight of the citizenry, and the street massacre of October (1927) makes even mechanical bridges seem ferocious. And less flamboyant moments, from the animalistic antics of the spies in Strike to the weeping masses at the Odessa quai, are full of expressive postures, gestures, and facial behavior. Eisenstein sculpts the human body so as to project extreme states of feeling.

That effort is on full display in Ivan the Terrible Part II, which I discuss in our current entry on FilmStruck‘s Criterion Channel. My commentary, grounded in a single sequence, builds on an analysis I offered in my book The Cinema of Eisenstein, but the clever experts at Criterion have created dynamic juxtapositions through cuts and replays that I couldn’t summon up in print. I try to show how, as ever, Eisenstein sacrifices bland realism of behavior to something more sharp and intense. In this “theatrical” film, he goes beyond line readings to offer maniacally heightened physical action–a sort of deadly serious, amped-up, live-action cartoon. Eisenstein worshipped Disney, after all.

Today’s blog entry bounces off that installment to show the connection between expressive movement and the most banal stock-in-trade of cinema: the standard scene of two people talking to each other.

Lessons with the master

A sketch from Eisenstein’s lectures on Crime and Punishment.

Eisenstein’s silent films seek a “dramaturgy of film form” that would surpass traditions of theatrical and novelistic storytelling. This mission, which creates a sort of epic cinema, left an odd gap. From Strike (1925) to Old and New (1929), his films are notably lacking in one stock ingredient. He seldom creates sustained scenes showing a developing conflict between two characters in an ordinary setting–a parlor or office or street. With few exceptions, Eisenstein “explodes” even standard scenes by cutting to action elsewhere. The factory owners of Strike chortle over drinks while, thanks to parallel montage, the workers are rounded up by soldiers on horseback.

Other Soviet Montage directors were willing to work up theatrical scenes: Pudovkin has a Hitchcockian suspense sequence in Mother (1926), while Kuleshov turns the second stretch of By the Law (1926) into a Kammerspiel. But Eisenstein’s urge to splinter face-to-face dramaturgy came from a different sense of theatre–that “Theatricalism” of his teacher Meyerhold, who saw the stage not as the copy of a real space but as an arena for performance. Eisenstein extended this idea by thinking of the shot and the sequence as an arena for action, specifically expressive movement.

By the 1930s, Eisenstein may have sensed that sound cinema would make films more theatrical in a traditional sense. Sequences would be more concentrated in one locale and focused on a few characters. Crosscutting, a mainstay of silent film, would become rarer. He accordingly began to ponder creative ways of filming two-handers. In his courses at the Soviet film school VGIK he explored ways to intensify dramatic face-offs without interruptive cutting.

These lectures are inspiring because they show you a filmmaker thinking through problems and tracing how one solution leads to new problems. A soldier returns from the war to find his wife pregnant with another man’s child. With his students Eisenstein spent weeks scrutinizing options for performance, shooting, and cutting this simple situation. A banquet is held for Dessalines, Haitian hero. How do you film his realization that his hosts are planning to kill him? How do you present the bedroom of Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, or the claustrophobic apartment of Thérèse Raquin? How do you stage Raskolnikov’s murder of the pawnbroker in Crime and Punishment…and do it in one fixed shot? (You don’t hear much about Eisenstein the long-take man.)

The results of this line of thinking show up in his films. Alas, we have only glimpses in what remains of Bezhin Meadow (finished 1937; banned, now lost). And Alexander Nevsky (1938), still conceived on a broad canvas, doesn’t really face up to the demands of intimate scenes. It’s only in both parts of Ivan the Terrible (1944, 1946) that we can see how Eisenstein plunged into doing what most directors do: filming uninterrupted scenes of people talking to one another.

Needless to say, he doesn’t do it the way they do.

The tsar in your lap

Expressive movement is involved, but so too are other stylistic strategies. For one thing, Eisenstein rethinks analytical editing. Characters need not face one another; they can be turned to the viewer and interact by shifting their eyes. No need for over-the-shoulder reverse angles either; you can cut in or out along the camera axis. Both strategies are introduced at the start of Ivan the Terrible Part I.

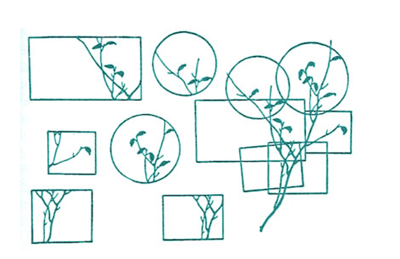

More elaborately, Eisenstein may dissect a scene through what he called in his VGIK classes the “montage unit” (uzel), a cluster of shots taken from roughly the same orientation. These yield chunks of space that overlap when edited together. He diagrammed this procedure in an illustration of cherry blossoms he found in a Japanese drawing manual.

This collage of overlapping bits, anticipating Hockney’s photo paste-ups, is actualized on film in the Pskov sequence of Ivan Part I, as I discuss in my book.

Another strategy is the use of depth. While Renoir, Welles, William Cameron Menzies, and other directors were trying out deep-space staging and depth of camera focus, so was Eisenstein. Well before Welles, he and his Soviet colleagues offered grotesque wide-angle shots. Below, Old and New and China Express (Ilya Trauberg, 1929).

More rigorously, Eisenstein began to think of how to arrange his scenes along the camera axis. True, a great many of his scenes are staged laterally, with figures arrayed from left to right.

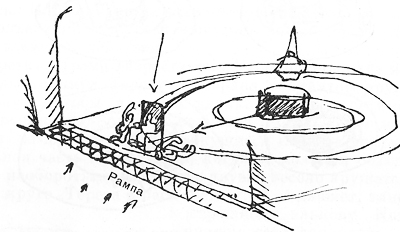

But others, particularly those at a dramatic pitch, are staged in depth. And what distinguishes Eisenstein, to my mind, is a strikingly confrontational or immersive approach. You can see it emerging in the VGIK exercises, notably in his stage designs for a hypothetical production of Thérèse Raquin. Here the paralyzed, speechless Madame Raquin terrorizes the murderous lovers with her glittering eyes. Eisenstein wanted the actors to perform on a turntable that would show her chair rotating to spy on the couple’s affair from different vantage points. At the climax, when the guilty lovers commit suicide, Madame Raquin’s chair was to break from the circle and propel itself forward, so that she would be staring furiously into the audience.

The footlights, marked with arrows, indicate that the effect is exaggerated by horror-style lighting from below.