Archive for the 'Film technique: Performance' Category

Watching you watch THERE WILL BE BLOOD

DB here:

Today’s entry is our first guest blog. It follows naturally from the last entry on how our eyes scan and sample images. Tim Smith is a psychological researcher particularly interested in how movie viewers watch. You can follow his work on his blog Continuity Boy and his research site.

I asked Tim to develop some of his ideas for our readers, and he obliged by providing an experiment that takes off from my analysis of staging in one scene of There Will Be Blood, posted here back in 2008. The result is almost unprecedented in film studies, I think: an effort to test a critic’s analysis against measurable effects of a movie. What follows may well change the way you think about visual storytelling.

Tim’s colorful findings also suggest how research into art can benefit from merging humanistic and social-scientific inquiry. Kristin and I thank Tim for his willingness to share his work.

Tim Smith writes:

David’s previous post provided a nice introduction to eye tracking and its possible significance for understanding film viewing. Now it is my job to show you what we can do with it.

Continuity errors: How they escape us

Knowing where a viewer is looking is critical to beginning to understand how a viewer experiences a film. Only the visual information at the centre of attention can be perceived in detail and encoded in memory. Peripheral information is processed in much less detail and mostly contributes to our perception of space, movement and general categorisation and layout of a scene.

The incredibly reductive nature of visual attention explains why large changes can occur in a visual scene without our noticing. Clear examples of this are the glaring continuity errors found in some films. Lighting that changes throughout a scene, cigarettes that never burn down, and drinks that instantly refill plague films and television but we rarely notice them except on repeated or more deliberate viewing. In my PhD thesis I created a taxonomy of continuity errors in feature films and related them to various failings during pre-production, filming, and post-production.

Our inability to detect continuity errors was elegantly demonstrated in a study by Dan Levin and Dan Simons. In their study continuity errors were purposefully introduced into a film sequence of two women conversing across a dinner table. If you haven’t seen it before, watch the video here before continuing, and see how many continuity errors you can spot.

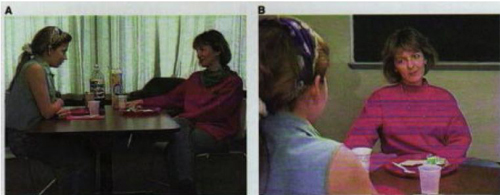

Two frames from the clip used by Levin and Simons (1997). Continuity errors were deliberately inserted across cuts (e.g., the disappearing scarf), and viewers were asked after watching the video whether they noticed any.

The short clip contained nine continuity errors, such as a scarf that changed colour, then disappeared, plates that changed colour and hands that changed position. During the first viewing, viewers were told to pay close attention but were not informed about the continuity errors. When asked afterwards if they noticed anything change, only one participant reported seeing anything and that was a vague sense that the posture of the actors changed. Even during a second viewing in which they were instructed to detect changes, viewers only detected an average of 2 out of the 9 changes and tended to notice changes closest to the actors’ faces such as the scarf.

Although Levin and Simons did not record viewer eye movements, my own experiments investigating gaze behaviour during film viewing indicate that our eyes will mostly be focussed on faces and spend virtually no time on peripheral details. If you as a viewer don’t fixate a peripheral object such as the plate, you are unable to represent the colour of the plate in memory and can, therefore not detect the change in colour when you later refixate it.

Tracking gaze

To see how reductive and tightly focused our gaze is whilst watching a film, consider Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (TWBB; 2007). In an earlier post, David used a scene from this film as an example of how staging can be used to direct viewer attention without the need for editing.

The scene depicts Paul Sunday describing the location of his family farm on a map to Daniel Plainview, his partner Fletcher Hamilton, and his son H.W. The entire scene is treated in a long, static shot (with a slight movement in at the beginning). Most modern film and television productions would use rapid editing and close-up shots to shift attention between the map and the characters within this scene. This frenetic style of filmmaking–which David termed intensified continuity in his book The Way Hollywood Tells It (2006)–breaks a scene down into a succession of many viewpoints, rapidly and forcefully presented to the viewer.

Intensified continuity is in stark contrast to the long-take style used in this scene from TWBB. The long-take style, which was common in the 1910s and recurred at intervals after that period, relies more on staging and compositional techniques to guide viewer attention within a prolonged shot. For example, lighting, colour, and focal depth can guide viewer attention within the frame, prioritising certain parts of the scene over others. However, even without such compositional techniques, the director can still influence viewer attention by co-opting natural biases in our attention: our sensitivity to faces, hands, and movement.

In order to see these biases in action during TWBB we need to record viewer eye movements. In a small pilot study, I recorded the eye movements of 11 adults using an Eyelink 1000 (SR Research) eyetracker. This eyetracker uses an infrared camera to accurately track the viewer’s pupil every millisecond. The movements of the pupil are then analysed to identify fixations, when the eyes are relatively still and visual processing happens; saccadic eye movements (saccades), when the eyes quickly move between locations and visual processing shuts down; smooth pursuit movements, when we process a moving object; and blinks.

Eye movements on their own can be interesting for drawing inferences about cognitive processing, but when thinking about film viewing, where a viewer looks is of most interest. As David demonstrated in his last post, analysing where a viewer looks whilst viewing a static scene, such as Repin’s painting An Unexpected Visitor, is relatively simple. The gaze of a viewer can be plotted on to the static image and the time spent looking at each region, such as a characters face or an object in the scene can be measured.

However, when the scene is moving, it is much more difficult to relate the gaze of a viewer on the screen to objects in the scene. To overcome this difficulty, my colleagues and I developed new visualisation techniques and analysis tools. These efforts were part of a large project investigating eye movement behaviour during film and TV viewing (Dynamic Images and Eye Movements, what we call the DIEM project). These techniques allow us to capture the dynamics of gaze during film viewing and display it in all its fascinating, frenetic glory.

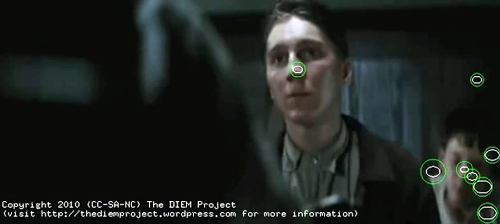

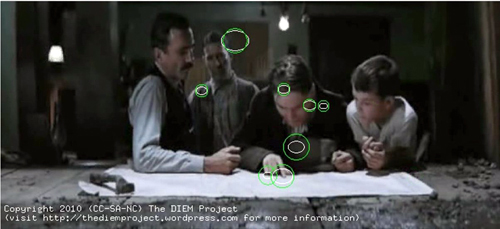

To begin, the gaze location of each viewer is placed as a point on the corresponding frame of the movie. The point is represented as a circle with the size of the circle denoting how long the eyes have remained in the same location, i.e. fixated that location. We then add the gaze location of all viewers on to the same frame. Although the viewers watched the clip at different times, plotting all viewers together allows us to look for similarities and differences between where people look and when they look there. This figure shows the gaze location of 8 viewers at one moment in the scene. (The remaining 3 viewers are blinking at this moment.)

A snapshot of gaze locations of 8 viewers whilst watching the “map” sequence from There Will Be Blood (2007). Each green circle represents the gaze location of one participant, with the size of the circle indicating how long the eyes have been in fixation (bigger equals longer).

You have a roving eye

Plotting static gaze points onto a single frame of the movie allows us to see what viewers were looking at in a particular frame, but we don’t get a true sense of how we watch movies until we animate the gaze on top of the movie as it plays back. Here is a video of the entire sequence from TWBB with superimposed gaze of 11 viewers.

You can also see it here. The main table-top map sequence we are interested begins at 3 minutes, 37 seconds.

The most striking feature of the gaze behaviour when it is animated in this way is the very fast pace at which we shift our eyes around the screen. On average, each fixation is about 300 milliseconds in duration. (A millisecond is a thousandth of a second.) Amazingly, that means that each fixation of the fovea lasts only about 1/3 of a second. These fixations are separated by even briefer saccadic eye movements, taking between 15 and 30 milliseconds!

Looking at these patterns, our gaze may appear unusually busy and erratic, but we’re moving our eyes like this every moment of our waking lives. We are not aware of the frenetic pace of our attention because we are effectively blind every time we saccade between locations. This process is known as saccadic suppression. Our visual system automatically stitches together the information encoded during each fixation to effortlessly create the perception of a constant, stable scene.

In other experiments with static scenes, my colleagues and I have shown that even if the overall scene is hidden 150milliseconds into every fixation, we are still able to move our eyes around and find a desired object. Our visual system is built to deal with such disruptions and perceive a coherent world from fragments of information encoded during each fixation.

The second most striking observation you may have about the video is how coordinated the gaze of multiple viewers is. Most of the time, all viewers are looking in a similar place. This is a phenomenon I have termed Attentional Synchrony. If several viewers examine a static scene like the Repin painting discussed in David’s last post, they will look in similar places, but not at the same time. Yet as soon as the image moves, we get a high degree of attentional synchrony. Something about the dynamics of a moving scene leads to all viewers looking at the same place, at the same time.

The main factors influencing gaze can be divided into bottom-up involuntary control by the visual scene and top-down voluntary control by the viewer’s intentions, desires, and prior experience. As part of the DIEM project we were able to identify the influence of bottom-up factors on gaze during film viewing using computer vision techniques. These techniques allowed us to dissect a sequence of film into its visual constituents such as colour, brightness, edges, and motion. We found that moments of attentional synchrony can be predicted by points of motion within an otherwise static scene (i.e. motion contrast).

You can see this for yourself when you watch the gaze video. Viewers’ gazes are attracted by the sudden appearance of objects, moving hands, heads, and bodies. The greater the motion contrast between the point of motion and the static background, the more likely viewers will look at it. If there is only one point of motion at a particular moment, then all viewers will look at the motion, creating attentional synchrony.

This is a powerful technique for guiding attention through a film. But it’s of course not unique to film. Noticing points of motion is a natural bias which we have evolved by living in the real world. If we were not sensitive to peripheral motion, then the tiger in the bushes might have killed our ancestors before they had chance to pass their genes down to us.

But points of motion do not exist in film without an object executing the movement. This brings us to David’s earlier analysis of the staging of this sequence from TWBB. This might be a good time to go back and read David’s analysis before we begin testing his hypotheses with eyetracking. Is David right in predicting that, even in the absence of other compositional techniques such as lighting, camera movement, and editing, viewer attention during this sequence is tightly controlled by staging?

All together now

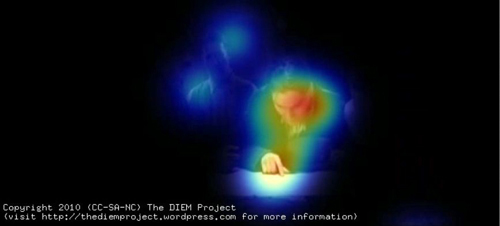

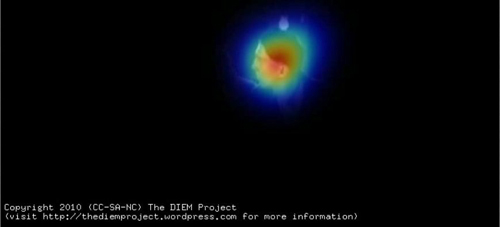

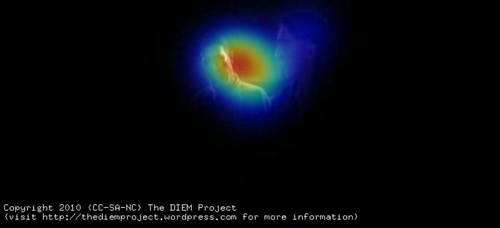

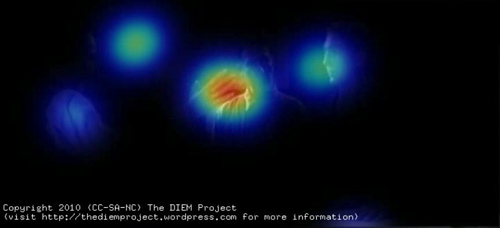

To help us test David’s hypotheses I am going to perform a little visualisation trick. Making sense of where people are looking by observing a swarm of gaze points can often be very tricky. To simplify things we can create a “peekthrough” heatmap. A virtual spotlight is cast around each gaze point. This spotlight casts a cold, blue light on the area around the gaze point. If the gazes of multiple viewers are in the same location their spotlights combine and create a hotter/redder heatmap. Areas of the frame that are unattended remain black. By then removing the gaze points but leaving the heatmap we get a “peekthrough” to the movie which allows us to clearly see which parts of the frame are at the centre of attention, which are ignored and how coordinated viewer gaze is.

Here is the resulting peekthrough video; also available here. The map sequence begins at 3:38.

Here is the image of gaze location I showed above, now matched to the same frame of the peekthrough video.

The gaze data from multiple viewers is used to create a “peekthrough” heatmap in which each gaze location shines a virtual spotlight on the film frame. Any part of the frame not attended is black, and the more viewers look in the same location, the hotter the color.

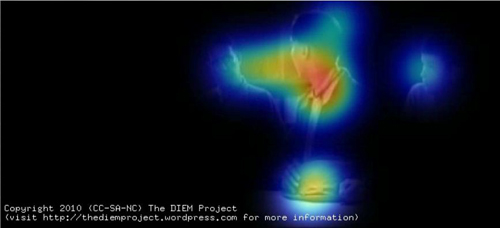

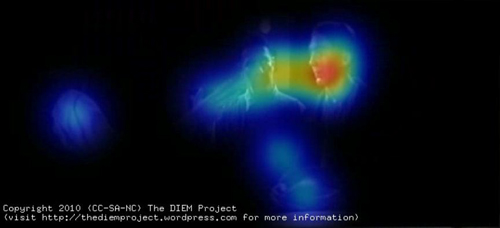

David’s first hypothesis about the map sequence is that the faces and hands of the actors command our attention. This is immediately apparent from the peekthrough video. Most gaze is focused on faces, shifting between them as the conversation switches from one character to another.

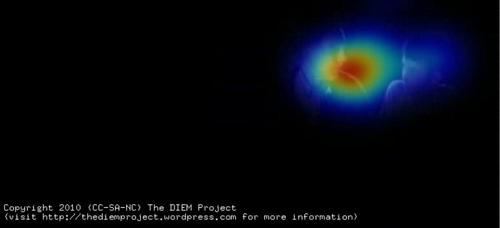

The map receives a few brief fixations at the beginning of the scene but the viewers quickly realise that it is devoid of information and spend the remainder of the scene looking at faces. The only time the map is fixated is when one of the characters gestures towards it (as above).

We can see the effect of turn-taking in the conversation on viewer attention by analyzing a few exchanges. The sequence begins with Paul pointing at the map and describing the location of his family farm to Daniel. Most viewers’ gazes are focused on Paul’s face as he talks, with some glances to other faces and the rest of the scene. When Paul points to the map, our gaze is channeled between his face and what he is gazing/pointing at.

Such gaze prompting and gesturing are powerful social cues for attention, directing attention along a person’s sightline to the target of their gaze or gesture. Gaze cues form the basis of a lot of editing conventions such as the match an action, shot/reverse-shot dialogue pairings, and point-of-view shots. However, in this scene gaze cuing is used in its more natural form to cue viewer attention within a single shot rather than across cuts.

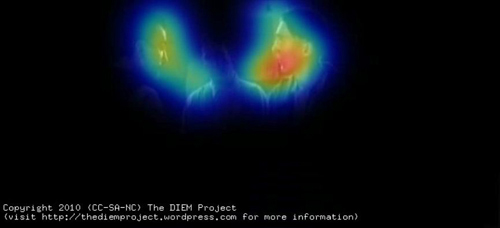

As Paul finishes giving directions, Daniel asks him a question which immediately results in all viewers shifting the gaze to Daniel’s face. Gaze then alternates between Daniel and Paul as the conversation passes between them. The viewers are both watching the speaker to see what he is saying and also monitoring the listener’s responses in the form of facial expressions and body movement.

Daniel turns his back to the camera, creating a conflict between where the viewer wants to look (Daniel’s face) and what they can see (the back of his head). As David rightly predicted, by removing the current target of our attention the probability that we attend to other parts of the scene is increased, such as H. W., who up until this point has not played a role in the interaction. Viewers begin glancing towards HW and then quickly shift their gaze to him when he asks Paul how many sisters he has.

Gaze returns to Paul as he responds.

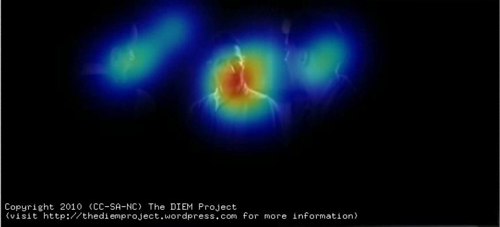

Gaze shifts from Paul to Daniel as he asks a short question, and then moves to Fletcher as he joins the conversation.

The quick exchanges of dialogue ensure that viewers only have enough time to shift their gaze to the speaker and then shift to the respondent. When gaze dwells longer on a speaker, such as during the exchange between Fletcher and Paul, there is an increase in glances away from the speaker to other parts of the scene such as the other silent faces or objects.

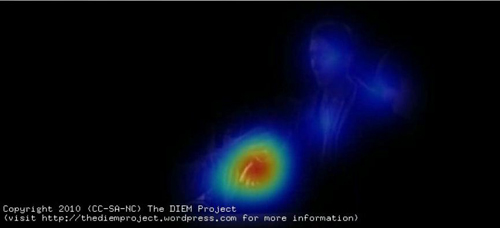

An object that receives more fixations as the scene develops is Paul’s hat, which he nervously fiddles with. At one point, when responding to Fletcher’s question about what they grow on the farm, Paul glances down at his hat. This triggers a large shift of viewer gaze, which slides down to the hat. Likewise, a subtle turn of the head creates a highly significant cue for viewers, steering them towards what Paul is looking at while also conveying his uneasiness.

The most subtle gesture of the scene comes soon after as Fletcher asks about water at the farm. Paul states that the water is generally salty and as he speaks Fletcher shifts his eyes slightly in the direction of Daniel. This subtle movement is enough to cue three of the viewers to shift their gaze to Daniel, registering their silent exchange.

This small piece of information seems critical to Daniel and Fletcher’s decision to follow up Paul’s lead, but its significance can be registered by viewers only if they happened to be fixating Fletcher at the time he glanced at Daniel. The majority of viewers are looking at Paul as he speaks and they miss the gesture. For these viewers, the significance of the statement may be lost, or they may have to deduce the significance either from their own understanding of oil prospecting or other information exchanged during the scene.

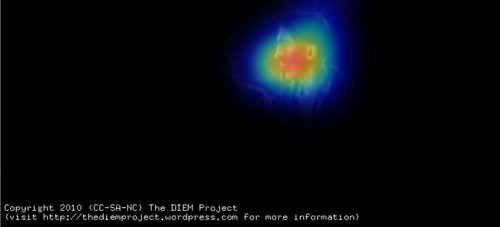

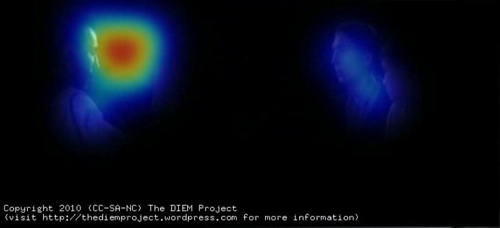

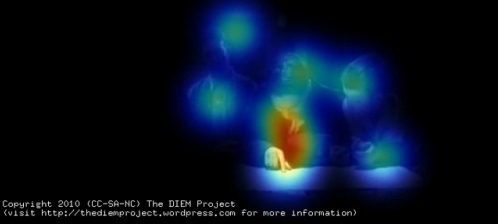

The final and most significant gesture of the scene is Daniel’s threatening raised hand. As Paul goes to leave, Daniel stalls him by raising his hand centre frame in a confusing gesture hovering midway between a menacing attack and a friendly handshake. In David’s earlier post he predicted that the hand would “command our attention.” Viewer gaze data confirm this prediction. Daniel draws all gazes to him as he abruptly states “Listen….Paul,” and lifts his hand.

Gaze then shifts quickly; the raised hand becomes a stopping off point on the way to Paul’s face. . .

. . . finally following Daniel’s hand down as he grasps Paul’s in a handshake.

We like to watch

The rapid sequence of actions clearly guide our attention around the scene: Daniel – Hand -Paul – Hand. David’s analysis of how the staging in this scene tightly controls viewer attention was spot-on and can be confirmed by eyetracking. At any one moment in the scene there is a principal action signified either by dialogue or motion. By minimising background distractions and staging the scene in a clear sequential manner using basic principles of visual attention, P. T. Anderson has created a scene which commands viewer attention as precisely as a rapidly edited sequence of close-up shots.

The benefit of using a single long shot is the illusion of volition. Viewers think they are free to look where they want but, due to the subtle influence of the director and actors, where they want to look is also where the director wants them to look. A single static long shot also creates a sense of space, clear relationship between the characters, and a calm, slow pace which is critical for the rest of the film. The same scene edited into close-ups would have left the viewer with a completely different interpretation of the scene.

I hope I’ve shown how some questions about film form, style, practice, and spectatorship can be informed by borrowing theory and methods from cognitive psychology. The techniques I have utilised in recording viewer gaze and relating it to the visual content of a film are the same methods I would use if I was conducting an experiment on a seemingly unrelated topic such as visual search. (See this paper for an example.)

The key difference is that the present analysis is exploratory and simply describes the viewing behaviour during an existing clip. What we cannot conclude from such a study is which aspects of the scene are critical for the gaze behaviour we observe. For instance, how important is the dialogue for guiding attention? To investigate the contribution of individual factors such as dialogue we need to manipulate the film and test how gaze behaviour changes when we add or remove a factor. This type of empirical manipulation is critical to furthering our understanding of film cognition and employing all of the tools cognitive psychology has to offer.

But I expect an objection. Isn’t this sort of empirical inquiry too reductive to capture the complexities of film viewing? In some respects, yes. This is what we do. Reducing complex processes down to simple, manageable, and controllable chunks is the main principle of empirical psychology. Understanding a psychological process begins with formalizing what it and its constituent parts are, and then systematically manipulating and testing their effect. If we are to understand something as complex as how we experience film we must apply the same techniques.

As in all empirical psychology the danger is always that we lose sight of the forest whilst measuring the trees. This is why the partnership between film theorists and empiricists like myself is critical. The decades of film theory, analysis, practice and intuition provide the framework and “Big Picture” to which we empiricists contribute. By sharing forces and combining perspectives, we can aid each other’s understanding of the film experience without losing sight of the majesty that drew us to cinema in the first place.

On the importance of foveal detail for memory encoding, see J. M. Findlay, Eye scanning and visual search, in The Interface of Language, Vision, and Action: Eye movements and the visual world, ed. J.M. Henderson and F. Ferreira (New York: Psychology Press, 2004), pp. 134-159. Levin and Simons’ continuity-error experiment is explained in D. T. Levin and D. J. Simons, “Failure to detect changes to attended objects in motion pictures,” Psychonomic Bulletin and Review4 (1997), pp. 501-506.

A note about our equipment and experimental procedure. We presented the film on a 21 inch CRT monitor at a distance of 90cm and a resolution of 720×328, 25fps. Eye movements were recorded using an Eyelink 1000 eyetracker and a chinrest to keep the viewer’s head still. This eye tracker consists of a bank of infrared LEDs used to illuminate the participant’s face and a high-speed infrared camera filming the face. The infrared light reflects of the face but not the pupil, creating a dark spot that the eyetracker follows. The eyetracker also detects the infrared reflecting off the outside of the eye (the cornea) which appears as a “glint”. By analysing how the glint and the centre of the pupil move as the viewer looks around the screen the eyetracker is able to calculate where the viewer is looking every millisecond.

As for the heatmaps, the greater the number of viewers, the more consistent the heatmaps. The present pilot study used gaze from only 11 viewers, which introduces a lot of noise into the visualisations. Compare the scattered nature of the gaze in the TWBB video to a similar scene visualised with the gaze of 48 viewers. We would probably see the same degree of coordination in the TWBB clip if we had used more viewers.

For a comprehensive discussion of attentional synchrony and its cause, see Mital, P.K., Smith, T. J., Hill, R. and Henderson, J. M., “Clustering of gaze during dynamic scene viewing is predicted by motion,” Cognitive Computation (in press). Social cues for attention, like shared looks, are discussed in Langton, S. R. H., Watt, R. J., & Bruce, V., “Do the eyes have it? Cues to the direction of social attention,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 4, 2, pp. 50-59. For more on our inability to detect small discontinuities, see Smith, T. J. and Henderson, J. M., “Edit Blindness: The relationship between attention and global change blindness in dynamic scenes,” Journal of Eye Movement Research (2008) 2 (2), 6, pp. 1-17.

For further information on the Dynamic Images and Eye Movement project (DIEM) please visit http://thediemproject.wordpress.com/. This research was funded by the Leverhulme Trust (Grant Ref F/00-158/BZ) and the ESRC (RES 062-23-1092). To view more visualisations from the project visit this site. The DIEM project partners are myself, Prof. John M Henderson, Parag Mital, and Dr. Robin Hill. Gaze data and visualisation tools (CARPE: Computational and Algorithmic Representation and Processing of Eye-Movements) can also be downloaded from the website. When using or referring to any of the work from DIEM, please reference the Cognitive Computation paper cited above.

Wonderful work in this area has already been conducted by Dan Levin (Vanderbilt), Gery d’Ydewalle (Leuven), Stephan Schwan (KMRC, Tübingen), and the grandfather of the recent revival in empirical cognitive film theory, Julian Hochberg. I am indebted to their pioneering work and excited about taking this research area forward.

Finally, I would like to thank David and Kristin for inviting me to describe some of my work on their wonderful blog. I have been an avid follower of their work for years and David has been a great supporter of my research.

DB PS 26 February: The response to Tim’s blog has been astonishing and gratifying. Tens of thousands of visitors have read his essay here, and his videos have been viewed over 700,000 times on sites across the Web. I’m very happy that so many non-psychologists–scholars, critics, and filmmakers–have found something of value here. The extended discussion on Jim Emerson’s scanners site, in which I participated a little, is especially worth reading. For more comments and replies from Tim and his team, go to Tim’s Continuity Boy blogpage and the DIEM team’s Vimeo page. At Continuity Boy, Tim will post more videos based on his group’s experimental efforts.

DB PS 18 October: Tim has posted a new, equally interesting experiment on tracking non-visible (!) movement on his blogsite.

THE SOCIAL NETWORK: Faces behind Facebook

DB here:

What do John Ford, Andy Warhol, and David Fincher have in common? Eyeball these remarks.

Ford, asked what the audience should watch for in a movie: “Look at the eyes.”

Warhol: “The great stars are the ones who are doing something you can watch every second, even if it’s just a movement inside their eye.”

Fincher, on the big club scene in The Social Network: “What’s cinematic are the performances . . . . What their eyes are doing as they’re trying to grasp what the other person is telling them.”

It isn’t just cinema that makes eyes important. Eyes are felt to be significant in literature, from the highest to the lowest. In just a couple of pages of a pulp adventure story you can read these sentences:

“Then it certainly does look very mysterious,” he said, but his blue eyes were quiet and searching.

Chief Inspector Teal suddenly opened his baby-blue eyes and they were not bored or comatose or stupid, but unexpectedly clear and penetrating.

What do quiet eyes look like, actually? Or searching ones: perhaps they’re moving a bit? Bored or comatose eyes might be droopy, so let’s count the eyelids as part of the eye. But what could make eyes, by themselves, penetrating? Nonetheless, we think we understand what such sentences mean.

Watching eyes is tremendously important in our social lives. We need to monitor other people’s glances to see if they are looking at us. We need to track what else they might be looking at. We need to watch for signals sent by the eyes, particularly attitudes toward the situation we’re in. For example, we seldom look directly into each others’ eyes, as characters in movies do constantly; in real life, “mutual gaze” is intermittent and brief. But if two people stare intently at each other, we’re likely to assume keen attraction or rising aggression.

In an essay from Poetics of Cinema available on this site, I talk about mutual gaze in cinema and how it can be exploited for dramatic purposes. The same essay takes up the issue of blinking; we blink frequently, but film characters seldom do, and the actors usually make the blinks emotionally expressive (of fear, uncertainty, weakness, etc.).

The problem is that eyes, by themselves, tell us very little about what the person behind them is thinking or feeling. We can show this with a little experiment.

Do the eyes have it?

What do these eyes tell us?

Certainly they give us information–about the direction the person is looking, about a certain state of alertness. The lids aren’t lifted to suggest surprise or fear, but I think you’d agree that no specific emotion seems to emerge from the eyes alone.

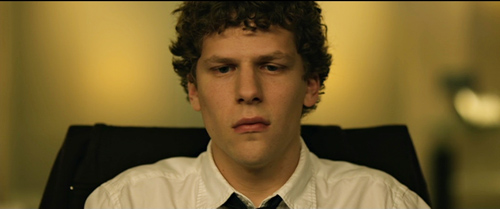

So what happens if we add eyebrows? (I’ve tipped the one above to conceal the brows; now you get to see the face’s proper angle.)

Now there’s a degree of surprise. The brows are lifted somewhat. But still the emotion seems fairly unspecific: not particularly sad or angry or distressed; probably not joyous either. Then what?

I’d call this dazed, slightly perplexed surprise. The sloping brows suggest the man is trying to figure out what’s happened; but the mouth is a slight gape. You can almost imagine the lips murmuring: “Ohhh,” or “Wow,” and not in appreciation or pleasure. If you wanted to show someone being blindsided, this is a pretty precise way to do it.

Of course context helps us a lot. Eduardo Savarin has just been gulled by his partner Mark Zuckerberg and by the interloper Sean Parker. His stock in the company that he co-founded is now worthless. So the situation informs our reading of Eduardo’s expression, and this permits the actor to underplay. Actor Andrew Garfield doesn’t give us bug-eyed surprise or frowning bafflement; he relies on our understanding of what he must be feeling (what we would feel) in order to refine and nuance his expression. When an actor underacts, we’re often expected to fill in the emotions we could plausibly imagine him to be feeling, on the basis of the story at this point. In isolation, the expression might be vague or ambiguous; the narrative situation helps sharpen it.

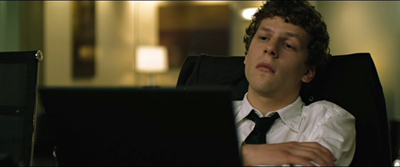

Back to the main question: How informative are the eyes alone? Try this one.

Again, I’ve tipped the shot a little to conceal the brows. Not much evident from the bare eyes, is there? Again, a certain focus and interest, but that’s about it. No marked surprise or fear or sadness.

Something has been added. The brows aren’t lifted in surprise or fear or sadness or distress; they seem to be relaxed. The angle of the look suggests concentration, but we’re not getting as much information as we got from Eduardo’s brows. We need a mouth.

The impression of concentration is greater, and I think we’d agree that this small smile of satisfaction gives us some insight into what the character is feeling. Again, the eyes tell only part of the story.

And again context matters. Mark Zuckerberg has just figured out that he can enhance The Facebook by adding users’ information about their romantic relationships. The tight, sidelong smile confirms not only his genius but also his view that college is partly about getting laid.

Less with the eyebrows

At this point you might be getting impatient with me. Isn’t this all obvious? Of course the actors use their faces–they’re paid to do that. But sometimes going obvious can get us to notice things.

For one thing, the eyes in themselves aren’t that emotionally informative. Pupil dilation can convey physical arousal, but that’s another story for another time. More commonly, the eyes give us the all-important information about what the person is looking at. The lids convey alertness, or drowsiness, or if they’re pinched a bit, concentration or anger.

Sometimes the eyes give us all the information we get. Here is Mark just before he agrees to take the job coding for the Winklevoss brothers’ project, The Harvard Connection. He moves from alertness to calculation by narrowing his eyes. As the phrase goes, you can hear the wheels turning.

Crucial to this moment is that nothing but Mark’s eyes and lids move; he doesn’t even turn his head. At the film’s climax, he will open up a little bit, and the eyelids play a central part. Getting the news that the Facebook party has been busted, Mark starts to breathe more laboriously, then wobbles his head slightly and closes his eyes. For once his concentration is broken.

It’s about as close as Mark comes to a canonical expression of sadness.

Obvious as it seems, by isolating the eyes we can notice the division of labor among eyes, eyelids, brows, and mouth: Each component supplies a bit of information. We’re remarkably skillful in integrating all these cues. What researchers into face perception call the informational triangle–the two eye regions tapering down to the mouth–creates a package of social and psychological signals. It’s this whole ensemble, the most informative parts of the face working together, that guides us in making sense of other people, or of film acting.

I’ve come to especially appreciate eyebrows. Daniel McNeill, in The Face: A Natural History, writes:

The eyebrow is the great supporting player of the face, and its work generally escapes notice. It helps signal anger, surprise, amusement, fear, helplessness, attention, and many other messages we grasp almost at once. Indeed, without eyebrows the surprise expression almost disappears. The eyebrows are such active little flagmen of mind-state it’s amazing anyone can wonder about their purpose. We use them incessantly (p. 199).

Since eyebrows are so important, actors must control them carefully. In the film’s first scene, Erica Albright moves her eyebrows vivaciously (and widens her eyelids too), but Mark’s brows are rigid and knit together.

This scene introduces us to Mark’s facial behavior. He will glance to the side when he’s pressed, but he’ll focus sharply on the other person when he’s trying to dominate the conversation. His mouth seems to be ruled by the triangularis and mentalis muscles, creating the inverted smile sometimes called the “facial shrug,” even when the lips are relaxed. Erica smiles a lot, something that usually triggers a responding smile. But not from this guy, though a smirk will occasionally flit over his mouth when he says something insulting. The closest we get to a true smile, I think, is at the blowout conclusion of the contest for internships, and that’s seen in the fairly distant long shot at the top of this section.

Above those eyes and that mouth sit those hooded brows, almost never lifting or lowering. Which is to say that Mark seldom shows surprise, and his anger will usually be visible in the set of his mouth (and in his words.) His flatlined brows sometimes suggest keen concentration, sometimes aloofness when he tilts his head back, or more pervasively the sense that everything in the vicinity is irritating. He seems to be permanently scowling, an effect that Fincher and DP Jeff Cronenweth accentuate by lighting that draws his brows closer together and hollows out the eye sockets.

How different this performance is from the actor Jesse Eisenberg’s everyday facial configuration (or at least the one he employs to send us other signals) can be seen in the making-of documentary accompanying The Social Network on DVD. One example surmounts this entry and shows a much different set of expressive cues–raised eyebrows, wider eyes, more cheerful mouth. The actor’s face is very mobile; he can even turn in the inner corners of his brows, which is hard to do voluntarily.

In one section of the making-of, Jesse reports that Fincher was often telling him, “Less with the eyebrows,” and onscreen Eisenberg delivered. By the end, for the last shots of Mark alone, Fincher asked for what’s become famous as the Queen Christina effect–an expression that could be read in many ways. “I want everybody to put anything on it.”

The result is a portrait of Generation Whatever, or an image of stoic loneliness, or of bemused curiosity about an old girlfriend, or. . . .

One more consequence of my noting the obvious: The centrality of faces to modern movies. Today’s films use close-ups very heavily, probably more than at any other point in film history. (The Way Hollywood Tells It explores some reasons why.) What I’ve called the “intensified continuity” style of modern cinema relies on tight single shots of individual players.

So modern players must be maestros of their facial muscles and eye movements. In other styles of filmmaking, currently and historically, the actor’s performance is projected onto more body parts through gestures, stance, gait, and the like. Recall Cary Grant, who performed with his whole body. Of course he wasn’t bad in close-ups either.

Faces aren’t everything in movies like The Social Network. Most characters use their arms and hands freely–probably the Winklevi the most. Mark is straightjacketed, but even he will gesture sometimes, as when a drooping Twizzler becomes his hand prop. He usually prefers a shrug, though it’s executed without the eyebrow lift most people add. Postures and personal walking styles play key roles in the film as well.

Still, as in most movies today, here eyes and brows and mouths are the main channels of emotional information. Fincher again: “It was really a movie about kids’ faces.” And even films from the 1910s, made before directors used a lot of cutting, often used long-shot staging to direct attention to the body’s most informative zones. A 1913 book on film acting noted, “Facial expression is perhaps the most important part of photoplaying. . . . After all is said and done the eyes are really the focus of one’s personality in photoplaying.”

Facebook facework

I can’t offer a complete account of nonverbal behavior in The Social Network here, but I want to end with a hypothesis that would be worth more detailed inquiry. The film’s central relationship is that between über-nerd Mark and Econ-major Eduardo, the coder and the aspiring tycoon (although he also supplies Mark with a crucial algorithm). Through facework, Fincher and his actors delineate the contrasting personalities and trace their shifting dynamic.

From the start, we get Mark’s stare of frowning concentration, drawing on the muscle called the corrugator, Darwin’s “muscle of difficulty.” By contrast, Andrew Garfield’s performance is marked by a look of worry and abashment. He’s often kinking his eyebrows, furrowing his brow, and ducking his head. Fincher motivates this behavior by having him often stoop over Mark’s workstation, tilt his head downward, and lift his eyes from underneath his brow.

In this shot/ reverse-shot passage, Mark’s mask never slips but Eduardo, wrinkling his brow and tipping his chin down a bit, looks apologetic.

Even when Eduardo has every right to berate Mark, he looks like he’s the one in the wrong. Instead of displaying the jammed-down, pinched-together brows of an angry man, he won’t lose his patient, slightly anxious look.

See the last image on this entry for a moment when Eduardo seems on the verge of tears–and this is after he’s gotten an invitation to join two alluring women.

You can argue that the blindsided expression we dissected earlier is one culmination of the facial cues that Andrew Garfield has been blending in the course of the film. But things are more complicated. The plot gives us two forward-moving timelines, one in the past tracing the rise of Facebook, the other in the present, during which Mark is deposed in two lawsuits. At an early deposition, Mark’s implacable stare works to make Eduardo revert to his old obeisance.

But in a climactic face-off, we come to see a different Eduardo.

Eduardo’s quiet testimony about whether anyone’s share but his was diluted (“It wasn’t”) affects Mark more deeply than the bluster of the Winklevoss brothers. The words are delivered without the usual sidelong glance, kinked eyebrows, or head ducking that has defined Eduardo earlier. His brow is smooth, his brows level. This is man to man, and it’s Mark who breaks off eye contact.

You could nuance this transformation by tracing it scene by scene, and contrasting it with the body language displayed by other characters. For today I simply wanted to sketch the broad development that I think is at work in this core relationship. The drama of domination and betrayal is played out in eyes, eyebrows, mouths, mutual gazes, and the like as much as it is in the dialogue and incidents.

There is no art, Shakespeare’s Duncan says, to read the mind’s construction in the face. He’s right about the reading part; we grasp expressions fast, intuitively, and often reliably. But there is art in the performer’s construction of the face, and of the director’s cinematic shaping of it.

John Ford’s remark about looking at the eyes is quoted in Joseph McBride’s Searching for John Ford (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010), p.2; the Warhol quotation comes from Andy Warhol and Pat Hackett, POPism: The Warhol ’60s (New York: Harper and Row, 1980), p. 109; quotations from David Fincher come from the bonus features on the collector’s edition DVD of The Social Network. My quotations about eyes in fiction are drawn from Leslie Charteris, Prelude for War (New York: Doubleday, Doran, 1938), pp. 171, 173. The 1913 quotation about eyes comes from Francis Agnew’s Motion Picture Acting (Syracuse: Reliance Newspaper Syndicate), p. 40; I learned of it from Janet Staiger’s article, “‘The Eyes Are Really the Focus’: Photoplay Acting and Film Form and Style,” Wide Angle 6, 4 (1985), pp. 14-23.

Ed Tan offers a very good analysis of the issues I mention here in his article “Three Views of Facial Expression and Its Understanding in the Cinema,” in Moving Image Theory: Ecological Considerations, ed. Joseph D. Anderson and Barbara Fisher Anderson (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005), pp. 107-127. I find Vicki Bruce and Andy Young’s In the Eye of the Beholder: The Science of Face Perception (Oxford University Press, 1998) a very helpful guide to ideas in this research area. The “facial shrug” is described in Gary Faigin’s excellent The Artist’s Complete Guide to Facial Expression (New York: Watson-Guptill, 1990), pp. 104-105.

There’s a fascinating debate in the human sciences about whether particular aspects of nonverbal communication are constant across cultures. Gestures vary considerably, but are facial expressions universal to some degree? Or do they differ from culture to culture? Are they primarily expressions of the person’s emotion, or are they signals which have developed, through evolution or cultural convention, to influence others? You can read more about these and other issues in Paul Ekman and Wallace V. Friesen, Unmasking the Face (Cambridge, MA: Maor Books, 2003) and Alan J. Fridlund, Human Facial Expression: An Evolutionary View (San Diego: Academic Press, 1994). The classic account is by Darwin, whose 1872 book Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals is available in an edition in which Ekman includes an afterword explaining the development of this research tradition.

Up to the minute, more or less: Contemporary research on smiling and eye contact.

PS 2 February: Thanks to William Flesch for correcting my Shakespeare citation: I originally attributed it to Hamlet.

Capellani ritrovato

Aladin ou la lampe merveilleuse.

Kristin here–

[Note, July 11, 2011. The release of a considerable number of Capellani films on DVD since the 2010 festival has allowed me to add some frames to my examples below. The frames from L’Arlésienne, L’Épouvante, and Pauvre mère are new, and the one from Cendrillon has been replaced by a better copy. For more on the DVD, see the entry on the second half of the retrospective.]

Back in the 1980s and early 1990s, researchers into silent cinema became used to the discovery of little-known auteurs. The 1910s proved an exceptionally rich source of directors beyond the familiar names of Griffith, Ince, Chaplin, Feuillade, Lubitsch, Stiller, and Sjöström.

In 1986 Le Giornate del Cinema Muto’s epic retrospective of pre-1919 Scandinavian cinema revealed the Swedish master Georg af Klercker. In 1989, a similarly ambitious presentation of pre-Revolutionary Russian films brought the work of Evgeni Bauer to light. In 1990, the “Before Caligari” year added Franz Hofer to the list of obscure directors at last receiving their due. After that quick series of revelations, there has been a dearth of such significant revelations until, some would argue, now.

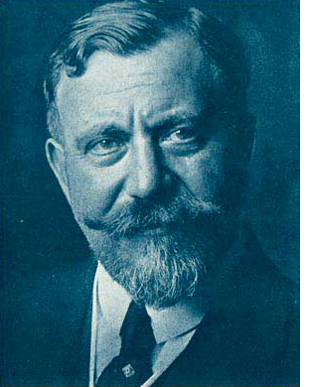

This year Bologna’s Il Cinema Ritrovato presented 24 films directed by Albert Capellani (1874-1931), previously known mainly to specialists for two films, his magisterial adaptations of Hugo in the four-part serial Les Misérables (1912) and of Zola in Germinal (1913). The retrospective has been  arranged by Mariann Lewinsky, who, as in previous years, has also been responsible for this year’s “Cento anni fa” program, covering the output of 1910. (The “Cento anni fa” series began in 2003, with Tom Gunning as programmer, and Mariann took over that duty in 2004.)

arranged by Mariann Lewinsky, who, as in previous years, has also been responsible for this year’s “Cento anni fa” program, covering the output of 1910. (The “Cento anni fa” series began in 2003, with Tom Gunning as programmer, and Mariann took over that duty in 2004.)

A gradual rediscovery

When Georges Sadoul wrote his multi-volume Histoire général du cinéma, the second part (1948) mentioned Capellani a few times. With the lack of available prints of the films, however, he was limited to treating the director primarily as the head of S.C.A.G.L., the prestige production unit launched by Pathé in 1908. Richard Abel’s The Ciné Goes to Town: French Cinema 1896-1914 (1994) devotes considerably more space to Capellani. Dick was able to view and analyze seven of the shorts and four features but was hampered by the incompleteness of some of these and the lack of such key films as L’Arlésienne (1908). As Mariann points out in her program notes, Capellani’s significance has been commented on by several scholars, including our colleagues Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs. (Ben’s detailed analysis of the acting in Germinal is here, including a citation to a 1993 article on the film by Michel Marie).

Mariann, however, has recently been instrumental in bringing Capellani’s films to broader attention. The decision to mount retrospectives of his work has spurred archives to restore several which had been unavailable or lost, and more prints will presumably be ready for next year.

Capellani has actually been creeping up on us in Bologna for some time now. In 2006, Mariann’s programs from 100 years ago had reached 1906–the year when Capellani’s career really got started, though at least one of his films appeared in 1905. We saw only one from 1906, La Fille du sonneur. I can’t say that I remember anything about it. In the 1907 program, Les Deux soeurs, Le Pied de mouton, and Amour d’esclave. Again, I probably would have to say that I don’t recall these films, except that I vaguely recognized Le Pied de mouton, a fairy tale about a young man who receives a magic object in the form of a large sheep’s foot, when it was shown again this year.

By 2008, however, a pattern had started to emerge, and Mariann showed seven Capellani films, with six of them forming one program devoted solely to the director’s work, “Albert Capellani and the Politics of Quality”: La Vestale, Mortelle idylle, Corso tragique, Samson, L’Homme aux gants blancs, and Marie Stuart. The seventh, Don Juan, appeared in the “Men of 1908” program.In visiting archives and choosing films Mariann often saw prints without credits and from unknown directors, so the pattern only gradually became clear. In the 2008 catalogue she reflected on her realization that Capellani was showing up regularly in her choices for the annual centennial celebrations: “When organising the 1907 programme, however, in the light of Amour d’esclave, a gorgeous mise-en-scène of classical antiquity, I asked myself for the first time, ‘Who made this sophisticated film?'”

She speculated that the relative neglect of Capellani perhaps came from the Surrealists’ campaign against highbrow filmmaking during the 1910s and 1920s:

From his very first film on–the memorable Le chemineau of 1905, based on an episode from Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables–Albert Capellani transports the contents and qualities of bourgeois culture to the cinema. He films Zola, Hugo and Daudet–his Arlésienne of 1908 has unfortunately been lost. His many fairy tale films (scène des contes), biblical and historical scenes reveal him as a great art director, who also adopted the latest developments in modern dance and worked with its stars Stacia Napierkowska and Mistinguiette. Highly versatile, he had an unerring sense of the best approach to a given genre.

Fortunately, L’Arlésienne has subsequently been discovered by Lobster Films, just in time to be presented this year.

The 2009 program contained only two Capellani films, but one was the extraordinary Zola adaptation L’Assommoir. This had been known only from fragments until a complete copy was found in Belgium. It displays an unusual degree of realism that fits the naturalist subject matter and also contains complex and deft staging that moves numerous characters around a scene in a way that shifts the spectator’s attention among them exactly as the flow of the narrative requires. The other, La Mort du Duc d’Enghien, was shown again this year. It’s a rare case of an historical drama of the period that manages to arouse a genuine sympathy for its main character, a young nobleman unjustly arrested and executed upon Napoleon Bonaparte’s orders. More on it later. The 2009 catalogue announced that in the following year, Capellani would graduate from the annual “Cento anni fa” programs to his own retrospective.

This year’s films

This first full-fledged Capellani retrospective gave a generous though not complete overview of his surviving films from early 1906 to 1914—a few bearing 2010 restoration dates. Capellani also worked in the United States from 1915 to 1922, and the program included The Red Lantern, a 1919 feature starring Nazimova. This, Mariann’s notes assure us, is “a taster for next year’s festival,” which will include further restorations from the French period, as well as more features from his American career. (It would be good to see the other Capellani films shown in previous years repeated, now that we have a sense of his work more generally.)

Ideally our examples here should include frames from the films shown at this year’s festival, but none of them is out on DVD. The Brewster article linked above has a generous selection of well-reproduced frames from a 35mm print of Germinal. As far as I know, the only Capellani film available on DVD is Aladin ou la lampe merveilleuse, on the third volume of Kino International’s “The Movies Begin” set. I’m sure it was included there not because it was a Capellani but because it survives in beautiful condition and is an epic with elaborate hand-coloring. I’ve included frames at the top and bottom of this entry, despite the fact that it has not been shown at Bologna. The smaller frames illustrating a few of films shown at Il Cinema Ritrovato come from the Gaumont Pathé Archives website (registration required). This site is the best online source of information on the director’s films, including complete video versions in a few cases. These are, however, quite small screens, and they display the double branding of a prominent timer and a bug of a Pathé rooster superimposed over much of the frame.

Capellani had worked in the theater as a director and actor until Pathé recruited him in 1905. In a sense, he became a specialist in literary adaptations, especially after his appointment in 1908 as artistic director of S.C.A.G.L. Yet the films being shown this year include pure melodrama (such as Pauvre mère, “Poor mother,” 1906), crime-suspense films (L’Épouvante, “The Terror,” 1911), classic fairy-tales (Cendrillon, 1907), and historical/biblical costume pictures (Samson, 1908).

With his theatrical background, it is not surprising that Capellani was able to cast many old colleagues in his films, notably Henry Krauss, who played Quasimodo in Notre-Dame de Paris (1911) and Jean Valjean in Les Misérables (1912). Wherever his actors came from, however, Capellani was a master at directing performances. In many cases the acting makes characters who would seem completely conventional figures in most films of the day into people with whom the audience can empathize.

The staging in Capellani’s shots is inevitably impeccable. The progression of the story is clear even in shots with numerous characters on camera. More of his stage experience coming out, one might say, but he also adapts his technique to the visual pyramid of space tapering toward the camera’s lens.

L’Évadé des Tuileries (1910), for example, deals with the Count du Champcenetz, the governor of the Tuileries during the French Revolution, who initially tries to alert the royal family to their impending arrest and subsequently flees for his life from the revolutionary forces that invade the palace. In the most spectacular shot, he rushes in, exhausted and wounded, to speak to the king as the members of the royal family gradually enter and guards surround them. Champcenetz collapses and slides partway under a chair at the foreground right as the revolutionaries burst into the room. The business of the ensuing struggle, the departure of the combatants with the royals under arrest, and a short burst of looting leaves a still scene with the dead and wounded on the floor. Suddenly an arm moves at the far lower right corner of the frame, and we become aware that Champcenetz has survived.

David has praised the sustained tableau staging in depth of the 1910s, in the films of Feuillade, Sjöström, Hofer, and others, but here is Capellani doing it all in 1910—and this is not the first of his films to display such control of the complex arrangement of actors in space.

None of this is to suggest that Capellani’s films are “stagey.” He is quite capable of a cinematic flourish for purposes of dramatic effectiveness. L’Arlésienne, shot largely on location in the old town of Arles, includes a shot of the young couple atop a tower that looks over the cityscape. The camera begins on the spire, panning right until the couple appear in medium shot, with the town beyond them and the parapet. They wander out right, and the camera pans around the parapet, only catching up with the couple when they are roughly 180 degrees opposite to where the camera started:

It is hard to believe that in London L’Arlésienne played on the same program as L’assassinat du Duc de Guise, which, sophisticated as it is in some ways, seems seems downright old-fashioned when contrasted with Capellani’s film.

Even flashier is L’Épouvante, which seems at first a simple story of a young woman in danger as she retires for the night, unaware that a burglar had stolen her jewelry just before she came in and is now hiding under the bed. She lights a cigarette and carelessly tosses the match on the floor. The camera tracks slowly back from the bed to bring the burglar into view; he registers fear that the match is still alight and might set the rug on fire. He reaches to snuff it out, and a sudden cut places us at a high angle above the heroine as she looks down and sees the hand appearing from beneath her bed. A return to the long shot displays her reaction:

Up to this point our sympathy has been entirely with the heroine. But once she escapes the room and locks the burglar in, his struggle to escape before the police find him takes up much of the remaining action and gradually gains him our sympathy as well. Trapped multiple stories up, he climbs to the roof, only to have to retreat as the pursuers rush up and search there. Moving downward, the burglar ends up hanging by an ominously bending gutter.

Only the heroine is left in her flat to discover his plight, and she lowers some drapes for him to climb up. In a touchingly awkward scene, the man is relieved but unable to express his gratitude except by returning the stolen jewelry and silently exiting, while she makes no attempt to stop him. In a way, L’Épouvante reminded us of Suspense, Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley’s remarkable 1913 film of a woman besieged in her house by a burglar, but the unexpected shift of emotional dynamics between the two characters in Capelanni’s film makes it equally memorable.

Capellani’s pictorial sense in real locations has been widely remarked upon. Even in La Mariée du château maudit (1910), a relatively slight tale of spooky doings in a deserted castle where a wedding party plays hide-and-seek, becomes impressive in part because of its use of an extensive set of actual ruins. There’s also a remarkable moment after the bride accidentally becomes locked in a room with a skeleton dressed in a bridal gown. She reads an old book telling of the young woman’s fate, and two successive bits of the story appear as matte shots on the right and left leaves of the open book. (Working at Pathé, Capellani could use impressive special effects, as the dream image in the Aladin frame at the top demonstrates.)

The sets are masterful as well. I was particularly struck by Jean Valjean’s desk in the second episode of Les Misérables (1912). It creates an effect of forced perspective that is like German Expressionist eight years ahead of its time. Valjean has escaped from prison and become a mayor and successful small-factory owner. Javert, formerly a guard at the prison and now a local police officer, suspects Valjean of being the fugitive. Now he comes to Valjean’s office to introduce himself.

Valjean sits at the left behind an enormous desk which dominates the left and center of the screen; its size is exaggerated by rows and stacks of thick volumes ranged across its top. About a third of the screen is empty at the right, where Javert enters at the rear and walks only partway forward. The effect is to make Javert appear smaller than he really is, with the low camera height that Pathé films were using by this point exaggerating the effect; during part of the scene he is also partially blocked by the desk. The suggestion is that he has no ability to follow up his suspicions of such a powerful man.

In a subsequent scene, when Valjean brings the ailing worker Fantine to his office, the desk has been moved away from the camera, which frames the scene from further to the right. The result is a far more open space at the right, while Valjean brings forward a chair for Fantine that puts her in front of the desk. Unlike Javert, she is not dwarfed by the desk, which, once Valjean comes to lean over her, is barely visible. Instead, the right half of the screen is left unoccupied so that a flashback can fill it.

In the scene like the one with Javert, a German Expressionist film would have exaggerated the size of the desk even further and perhaps tilted the floor up at the rear, but the effect is clear and dramatic enough as it is. Again, it is not an effect one would expect to find in a film of the early 1910s. There is also a contrast between the massive desk and the relatively small, insubstantial table that Javert uses as a desk in the setting of the police headquarters

Even the most conventional films receive what I began to recognize as Capellani touches, often to bring a moment of realism into a fantasy or melodramatic setting. In Cendrillon, the gardener who carries in a huge pumpkin to be turned into the heroine’s magic coach exits wiping the sweat from his head with a handkerchief (below left). The little girl who falls out of a window to her death in Pauvre mère leaves a large, dramatic splotch of blood on the sidewalk when her lifeless body is lifted—a realistically gory touch of a sort which I don’t recall seeing in any other film of this era (below right). When the hero finds the magic lamp in Aladin ou la lampe merveilleuse, he blows dust off it and turns it over to shake out further dirt (see bottom).

Another sort of touch appears in La Mort du Duc D’Enghien, a carefully executed motif of a sort one doesn’t often see in films of this type. The hero is arrested while at a hunting lodge, and throughout he wears a distinctive hat that’s probably part of a hunting outfit. He throws it defiantly to the floor during the courtroom scene in which he is unjustly condemned; he throws it down again in his cell, this time to indicate despair and exhaustion; in the final execution scene, he tosses it aside as part of his brave resignation, facing the firing squad with open arms and without a blindfold. These moments aren’t stressed, and one could understand the plot perfectly well without noticing the repetition. Still, the motif helps characterize D’Enghien quickly in this relatively short film and indicates the care with which Capellani was crafting even his one-reelers.

Mariann was somewhat apologetic about La Glu, a 1913 feature, since it centers around a femme fatale who victimizes three men in the course of the narrative. The title is the heroine’s nickname, and it means what it sounds like, “glue,” and particularly sticky substances like bird-lime that are used to ensnare. But the audience thoroughly enjoyed this distinctly absurd but entertaining and fast-paced tale of a heartless, mercenary woman, played with relish by Mistinguett, and the men foolish enough to fall for her. After all, there are plenty of depictions of love-’em-and-leave-’em men from this period, so why not turn the tables? At least one flagrant coincidence brings all of them to the south of France, where the heroine goes for a vacation, and Capellani contrasts the early scenes of high-society Paris with the stark seascapes in and around a fishing village. Though another literary adaptation (from a novel and play by Jean Richepin), this film certainly stands out among the pre-war features and demonstrates once more Capellani’s versatile ability with a range of genres.

After all these treats, the last French feature on offer, Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge (1914), proved a slight let-down. Capellani had a penchant for substituting letters and other texts for intertitles, but this film pushes the device to the point where sometimes it seemed as if every other shot was an insert. The plot, dealing with a scheme to rescue the imprisoned Marie Antoinette, was also frustratingly complicated and not presented with the admirable clarity that characterizes most of the other films. As I’ve mentioned, Capellani was often able to generate an empathy with the characters which is rare for films of this period, but as a result of the constant plot twists, the Chevalier and his endangered mistress remain rather remote figures. There are some effective moments, though. One exterior view of the protagonist’s home places a door at the upper center, approached by a symmetrical pair of staircases running to the right and left and forming a pyramid shape. A foreground pond elaborates the space still further, so that when a crowd tries to break in, the staging utilizes the frame vertically and horizontally, with intricate movements of individuals to avoid the water.

Ahead of his time–up to a point

As I remarked in an entry on last year’s festival, L’assommoir struck me as looking like it had been made in 1912 or 1913 rather than 1909. Now it becomes clear that many of Capellani’s films give this sense of trying things that other filmmakers would begin doing routinely a few years later. In some cases, like L’Arlésienne, it’s a focus on acting of a sort that we associate with Griffith’s films like The Mothering Heart or The Painted Lady. In others, it’s the motifs or the subtle changes of framing or the eye for landscapes. Although the editing is not usually flashy, Capellani is good at keeping spatial relationships clear, as the series of shots depicting Valjean’s escape from prison in the first part of Les misérables demonstrates. As Mariann wrote, he seemed able to adapt to any genre. I’m not a particular fan of the historical films so common during this period, but Capellani manages to humanize most of his.

It was only with Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge that the sense of Capellani being ahead of most of the directors of his time largely disappeared, though it seems premature to judge from a single 1914 film. Perhaps during the immediate pre-war era, and especially the creatively fecund year of 1913, the exploration of the cinema by an increasing number of masters created a spurt that he did not participate in. And perhaps more films from 1913 and 1914 will appear in next year’s retrospective and give us a better sense of how his career developed in that crucial period. It will also be interesting to trace his assimilation of the developing classical Hollywood norms once he moved to the U.S. By 1919 and The Red Lantern, he clearly had absorbed the norms thoroughly, and his style had become indistinguishable from that of his American colleagues.

Added July 13: Roland-François Lack has kindly written to point out that another Capellani film exists on DVD. (Thanks, Roland-François!) His 1908 version of the French tale Peau d’âne was included as a supplement on the  collector’s edition of Jacques Demy’s film of the same name. It is also included in the “Intégrale Jacques Demy” 12-disc set. These DVDs are Region 2 (Europe) and won’t work on other region-coded players.

collector’s edition of Jacques Demy’s film of the same name. It is also included in the “Intégrale Jacques Demy” 12-disc set. These DVDs are Region 2 (Europe) and won’t work on other region-coded players.

The source of the print isn’t clear on the disc. (It’s another one that hasn’t been shown at Bologna.) Probably Pathé’s own archive, since there’s a little rooster-shaped bug superimposed at the lower left in every shot.

It’s a fairly contrasty print with replaced intertitles in French only. It also seems to be running at 24 fps or something close to it. The action zips right along, which is a pity. There’s a lot of carefully executed pantomime-style acting. It’s impossible to catch all the gestures, especially since there are often three or four actors going at it at the same time. It would actually be a good film for teaching about the acting styles of this period if one could just slow it down.

I wouldn’t have spotted this as a Capellani film if I hadn’t known its source when I watched it. Still, it has some of the traits we’ve recently come to associate with him. The meeting between the heroine and Prince Charming takes place in a carefully chosen setting with a reflecting pond in the foreground. It looks like the film was shot on a hazy day, but it looks as though the camera may be set up to shoot with the sunlight at the characters’ backs.

The film also has the director’s typical elaborate interior sets juxtaposed with a dramatic use of real exteriors. The frame at the left below shows the fairy appearing for the first time to the princess. It’s not easy to see, but the busy interior includes a deep, diagonal space with several arches decorated with portraits that are painted, frames and all on the square pillars. Once the heroine disguises herself and flees to avoid her suitors, Capellani goes on location, using an impressive château and streets that look like they are in the same vicinity.

I hope that some of the more realistic films will soon appear on DVD. Lobster in particular could make their newly restored L’Arlésienne available.

Everybody’s Irish

Three Bad Men (1926) at the Piazza Maggiore; Orchestra del Teatro Communale di Bologna conducted by Timothy Brock. Photo by Lorenzo Burlando.

DB, still in Bologna:

The early Ford retrospective at Cinema Ritrovato rolls on. The surviving reel of The Last Outlaw (1919) proved very tantalizing. An end-of-the-West Western, it shows its grizzled hero revisiting the town of his youthful exploits. But now, in an anticipation of Ride the High Country (1962), civilization has taken over. Cars chase Bud off the streets and the theatre features movies (Universal Bluebirds at that, a bit of product placement). Ford heightens the contrast by letting us into the hero’s memory, introduced by the title: “Memories of the past flashing back to him”—the earliest reference to the term “flashback” I recall seeing in the movies.

The plot of Cameo Kirby (1923) involves a cardsharp who tries to help a southern family but whose chivalrous intentions are misunderstood. The film’s virtues were, I’m afraid, undercut by a choppy, contrasty print. Another 1923 vehicle, North of Hudson Bay (1923) was in much better shape. A fairly routine adventure about schemers trying to take over the gold claim of two brothers, it was enlivened by a mysterious murder scene, in which a man is shot before our eyes but we can’t say exactly how. Ford later replays the scene to clarify what happened, and then sets up suspense as the trap is put in play again, this time to kill our hero.

Kentucky Pride (1923) is a turf tale narrated by a racehorse. This might have become a tedious gimmick, but the film handles it with aplomb and modest emotion. Our narrator Virginia’s Future stumbles during the race, and the scene during which she is about to be shot generates a great deal of suspense and concern. At the end, her reunion with her son, Confederacy, is smoothly integrated into the humans’ reconciliations and just deserts. In between, Virginia’s Future passes from owner to owner, in something of a rough draft for the adventures of Bresson’s donkey in Au hazard Balthasar.

Kentucky Pride is a programmer, but between the peaks of racetrack excitement we get several arresting interludes. In one scene the now-destitute horse farmer reunites with his daughter. He’s at the dinner table. She comes up behind him and covers his eyes. So far, so conventional. But he raises his calloused, dirtied hands very slowly to touch her wrists. Prolonging the gesture shows not only Ford’s delicate way with such moments but the quiet skill of Henry B. Walthall; it’s impossible not to think of similar handwork in Griffith’s The Avenging Conscience (1914) and The Birth of a Nation (1915). The scene’s subdued pathos was enhanced by the accompaniment of Neil Brand, a Bologna regular.

Kentucky Pride is a programmer, but between the peaks of racetrack excitement we get several arresting interludes. In one scene the now-destitute horse farmer reunites with his daughter. He’s at the dinner table. She comes up behind him and covers his eyes. So far, so conventional. But he raises his calloused, dirtied hands very slowly to touch her wrists. Prolonging the gesture shows not only Ford’s delicate way with such moments but the quiet skill of Henry B. Walthall; it’s impossible not to think of similar handwork in Griffith’s The Avenging Conscience (1914) and The Birth of a Nation (1915). The scene’s subdued pathos was enhanced by the accompaniment of Neil Brand, a Bologna regular.

In another horsy tale, The Shamrock Handicap (1926), the financially challenged aristocrat is an Anglo-Irish lord , and to pay his taxes he sells some of his stable to an American racing entrepreneur. His top rider, Neil, goes along, leaving sweetheart Sheila behind. Once in the US, Neil takes a serious spill and acquires a game leg. Soon the aristocrat and his 120 % Irish household are coming to America to stake everything on racing their pride filly in the Handicap. The whole thing is a pleasant tissue of contrivance and coincidence, allowing Ford some chances for sentiment, camera tricks induced by ether, and gags on Irishness. The horse handler discovers that all his old friends and kinfolk in the New World have become cops.

There were opportunities to develop Sheila as more than a pretty face (that belongs to the enchanting Janet Gaynor), but the plot puts the menfolk to the front. The scenes of Neil’s acceptance in the hard-bitten jockey world show America as a place in which ethnic minorities hang together; his best friend is a Jewish rider who keeps a black valet. The characteristic Ford sadness surfaces in a lovers’ reunion. When Neil greets Sheila at dockside, Ford gives us a painful glimpse of wounded masculine pride. Neil stands waiting with his pals. Has he recovered?

As Sheila approaches, Neil swings his crutch abruptly away from her, as if to hide it. But the same gesture sharply reveals to us that he’s now lame.

In their embrace, the crutch falls away. Neil clutches Sheila as if she were not his sweetheart but his mother; he needs consolation, not passion.

The film may be about male pride, but as ever in Ford a man’s sense of self-worth is sustained by a touching reliance on women. So it’s fitting that the walking staff Neil leaves behind in Ireland–a slip in continuity, you might think–becomes his new crutch when he comes home again for good.

Lightnin’ (1925) moves not like lightning but at the pace of its elderly protagonist, Bill (Lightnin’) Jones. The opening is a drawling play with rustic humor, centering on Bill’s laborious stratagems to hide his whisky bottles from his wife. Bill isn’t Irish, but he might as well be, like the purported Welshmen of How Green Was My Valley (1941).

Initially the film seems to depend on one of those promising screenwriting switcheroos. The couple manage a hotel perched on the border between California and Nevada, so aspiring divorcées can collect their California mail and still maintain residency in Nevada. A dividing line runs through the center of the house, and it provides some adroit byplay when a young lawyer, pursued by corrupt businessmen, teases the Nevada sheriff by hopping from state to state. The romance between the lawyer and the old couple’s adopted daughter is handled briskly, with the usual repeated-and-varied dialogue motifs (courtesy Frances Marion’s script). One might expect a climax wringing comic confusion out of the divided household. But soon the border gimmick is forgotten and Ford moves to the emotional core of the movie, the testing of the old couple’s marriage.

When Mrs. Jones tries on a guest’s fashionable dress to find out what it’s like to wear nice clothes, Bill reacts obtusely. It’s his indifference as much as her decision to sell the hotel to land-grabbers that pushes her to sue for divorce. The climax is a prolonged trial scene in which Bill becomes his own advocate. As in later folkish tales like Judge Priest (1934) and The Sun Shines Bright (1953), plot dynamics take a back seat to horseplay and quietly detailed scenes of character reaction and reflection. Some laughs are milked from the family dog wavering between husband and wife, the judge flirting with a flapper, and the dimwitted drinking buddy with his two pudgy children. But soon Bill is fingering his Civil War medal as he slowly confesses his faults as a husband, and we recognize what we’d learn to call a pure Fordian moment.

Those were the days when you could make a film about old people.

For more on Ford, visit Tag Gallagher’s generous and wide-ranging website. It includes a revised version of his critical biography on the Skipper, as well as articles on many other filmmakers. For more Cinema Ritrovato photos, go here. For Gabe Klinger‘s rapid-fire Bologna updates, try Mubi. And for remarks on non-Fordian entries in this abundant festival, check in with us again soon.