Archive for the 'Film music' Category

When worlds collide: Mixing the show-biz tale with true crime in ONCE UPON A TIME . . . IN HOLLYWOOD

Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood.

Jeff Smith here:

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood might turn out to be the buzziest film of 2019. Some of this water-cooler talk is due to its unusual status within an ever-enlarging field of true crime stories. (Call it a “not quite true” crime story.) Indeed, the genre is hotter than ever thanks to a bevy of new podcasts, telefilms, and miniseries.

Industry analysts, though, are also keen to interpret Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s box office fortunes. As that rare big summer release that is neither a sequel nor a franchise title, it can be seen as a test of whether original content can survive amidst heavily marketed, presold tentpoles.

The lesson so far? To quote William Goldman, “Nobody knows anything.” In The Washington Post, one unnamed studio executive warned, “I don’t see any blue-sky meaning here.” The executive added, “This movie has assets that almost no other film has. That’s what drove it.” At least one of those assets is Tarantino himself, who is a brand, if not a franchise. Fans know what to expect in a Tarantino film, which is why the film is sui generis when it comes to this summer’s slate. Due to its unique IP, it can’t really be compared with films like Men in Black International or Spider-man: Far from Home. Yet thanks to Tarantino’s larger than life presence, it also isn’t Long Shot or Booksmart or Stuber.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is catnip to Tarantino nerds like me. It has the usual surfeit of references to obscure films and television shows. Some of these are deftly interwoven into the story itself. It boasts a carefully curated soundtrack that unearths “some-hits” wonders. It also contains scenes depicting nasty yet comical violence, a hallmark of Tarantino’s work ever since Reservoir Dogs.

At first blush, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood would seem to be Tarantino’s most linear film. Yet it still displays certain continuities with his oeuvre in terms of story structure and technique. Although the film eschews the chapters and title cards found in Pulp Fiction and Kill Bill, it still contains elements of what David calls “block construction.” In the case of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, it is all about threes. The plot is structured around three days in the winter and summer of 1969: February 8th, February 9th, and August 9th. Each “chapter” is introduced showing the date via superimposed text. And all three chunks of narrative crosscut among the activities of three actors – Sharon Tate, Rick Dalton, and Cliff Booth – as they try to adapt to changes in the film and television industries.

If all of this assures that you’d never mistake Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood as the work of another director, other elements show Tarantino striking out in new directions. Chief among these is his mash-up of two normally distinct story types: the show-biz tale and the true crime yarn. Think of it as Singin’ in the Rain meets In Cold Blood. In what follows I outline some of the ways that Tarantino adapts his signature style to two well-established storytelling options: the multiple draft narrative and the network narrative. I also consider the effects Tarantino’s counterfactual history has on the conventions of the show-biz tale and the celebrity biopic.

My analysis contains major spoilers. If you haven’t seen Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, stop reading now!

My world and welcome to it

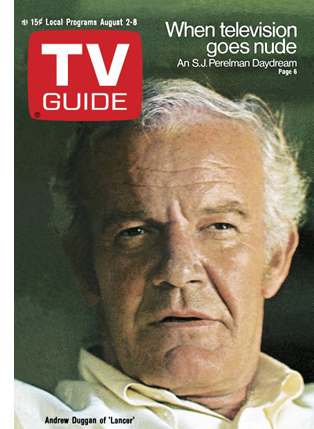

Quick trivia question: what actor was on the cover of TV Guide during the week that Sharon Tate was murdered by the Manson family? Sharp viewers of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood should know the answer. We see Tate’s housemate, Woychiech Frykowski, reading that issue of the magazine as he watches Teenage Monster on late night television.

Give up? It was character actor Andrew Duggan, who played the cattle baron Murdoch Lancer on the TV show of the same name. Yes, that Lancer! The same one that featured Rick in a guest spot some six months earlier.

Give up? It was character actor Andrew Duggan, who played the cattle baron Murdoch Lancer on the TV show of the same name. Yes, that Lancer! The same one that featured Rick in a guest spot some six months earlier.

Tarantino’s film treats this little bit of pop culture ephemera as an uncanny coincidence. It simply becomes yet another way that he can intertwine the destinies of his three protagonists. But that brief shot got me thinking: did Tarantino start with the idea that he’d recreate whatever series was featured on TV Guide the week Tate was killed?

If so, Rick might have appeared just as easily as an aspiring cartoonist next to William Windom on the NBC sitcom, My World and Welcome to It. The show debuted just six weeks after Tate’s death. It is not unthinkable that NBC would have pushed for a cover on TV Guide in an effort to promote the premiere. Yet Tarantino’s counterfactual history in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood would have been vastly different if that had been the case.

Did Tarantino really base his screenplay on this conceit? I doubt it. Lancer fits so snugly into the world that the director captures onscreen that it is not be so easily replaced. Tarantino seems to have a nostalgic fondness for the show, much as I did in my wasted youth. (I recall having a Lancer lunchbox at age six.) Production designer Barbara Ling describes the steps she took to recreate Lancer’s mix of Spanish/Western design. This involved adding adobe storefronts to the wooden ones, and substituting iron coils for wooden pegs on the saloon’s staircase. Ling added, “This was a [rich] cattle town and the buildings are two and three stories. It’s not Deadwood.”

Many critics have characterized Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood as another hangout movie. This is Tarantino’s designation for a film that is leisurely paced, fairly light on plot, and mostly gives the audience a chance to spend time with the characters. Indeed, because of these qualities, reviewers often compare Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood to Jackie Brown, a film that Tarantino himself compared to Rio Bravo, which was Howard Hawks’ hangout movie.

The resemblances don’t stop there. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s three-headed protagonist bears certain similarities to Jackie Brown’s Jackie, Ordell, and Max.

Yet while watching Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, I felt this film, more than any of Tarantino’s others, was an exercise in world-building. Normally we associate that term with sci-fi, fantasy, and comic book movies. It is especially important for transmedia properties where the fictional universe depicted exceeds the bounds of any individual film, television series, book, or video game.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is also an alternate history, a type of speculative fiction also common in sci-fi and comic book stories. The Avengers: End Game and Spider-man: Into the Spiderverse are both relatively recent examples. This suggests a loose affiliation between Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood and other blockbusters even as Tarantino tweaks that formula by situating his speculative fiction within the generic framework of true crime.

Tarantino largely avoids the industrial motivations behind these two narrative techniques commonly seen in tentpoles. Instead, he simply recreates the pop culture world of his youth. In doing so, the director’s real world, his “realer than real” universe, and his “movie movie” universe all collide.

Keepin’ it real (and realer)

As Tarantino has explained in interviews, the “realer than real” universe is an alternate reality close to our own where his fictional characters can intermingle with real people. The “movie movie” universe, on the other hand, is a more overtly fantastic world closer in spirit to comic books or exploitation films. The characters have unusual abilities or even supernatural powers. The “movie movie” thus downplays the realistic motivations usually found in the “realer than real.” In Tarantino’s oeuvre, Reservoir Dogs and True Romance exemplify the “realer than real.” Kill Bill and From Dusk to Dawn are instances of the “movie movie.”

Each universe features a web of connections that can link particular tales together. For example, Kill Bill’s Sheriff Earl McGraw and his son Edgar pop up in Death Proof. Similarly, Lee Donowitz, the cocaine-sniffing movie producer in True Romance, is purportedly the son of Sgt. Donny Donowitz, the “bear Jew” in Inglourious Basterds.

In Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, the most obvious references to these two Tarantino universes are the fictional brands he has created. During the end credits, we see Rick in a TV ad for Red Apple cigarettes. According to a Tarantino wiki, “ads or packs of these flavorful smokes” can be seen in The Hateful Eight, Inglourious Basterds, Planet Terror, Kill Bill, Pulp Fiction, From Dusk till Dawn, Four Rooms and Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion. (The latter is an obvious outlier. Yet the Red Apple nod was likely an in-joke related to Tarantino’s offscreen romance with Mira Sorvino, who played Romy.)

Similarly, Tarantino’s fictional fast food chain, Big Kahuna Burger, appears on a bus billboard in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood. It previously was featured in a memorable scene in Pulp Fiction. (“That’s a tasty burger!”) But it had already debuted as a delicious snack devoured by Mr. Blonde in Reservoir Dogs. Big Kahuna later comes back in two other Tarantino films, From Dusk Till Dawn and Four Rooms, as well as Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion.

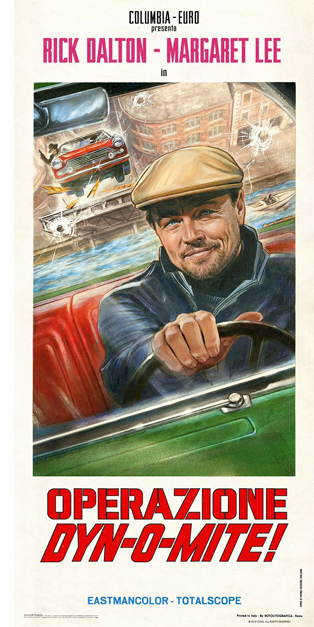

Other references to the “realer than real” are more arcane. In a montage sequence where Randy the Stuntman summarizes Rick’s experience starring in Italian films, we see a poster for Operazione Dy-no-mite, a James Bond knockoff directed by Antonio Margheriti. Fans of Inglourious Basterds will recognize “Antonio Margheriti” as the alias Donny Donowitz uses for the premiere of Nation’s Pride.

Other references to the “realer than real” are more arcane. In a montage sequence where Randy the Stuntman summarizes Rick’s experience starring in Italian films, we see a poster for Operazione Dy-no-mite, a James Bond knockoff directed by Antonio Margheriti. Fans of Inglourious Basterds will recognize “Antonio Margheriti” as the alias Donny Donowitz uses for the premiere of Nation’s Pride.

Much of the fun of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood comes from the way Tarantino overlays these three universes to create a singular fictional world. For example, at one point we learn that Rick was considered for the role of Captain Virgil Hilts, the part played by Steve McQueen in John Sturges’ The Great Escape. Tarantino even inserts digitally altered footage of The Great Escape to show us a scene of Rick as Hilts. Since Rick claims he never met Sturges, this moment appears to represent an imagined version of the film that could exist in some type of alternate history. It invites us to consider how different Rick’s career might have been had fortune smiled upon him instead of McQueen.

To disentangle this knot, one must surmise that The Great Escape and Steve McQueen belong to both the real world and the “realer than real” world. Yet the scene of McQueen at the Playboy mansion and Rick describing his missed opportunity can only belong to the “realer than real.” And the character of Hilts himself exists only in the “movie movie” world. Hilts shares this status along with other characters Rick plays onscreen, such as Bounty Law’s Jake Cahill and The FBI’s Michael Murtaugh. After all, movie magic enables Cliff Booth to stand-in for Rick for scenes involving physical action. That two actors can play the same character within the same scene suggests that fictional personae in cinema have a unique ontological status quite different from the real world.

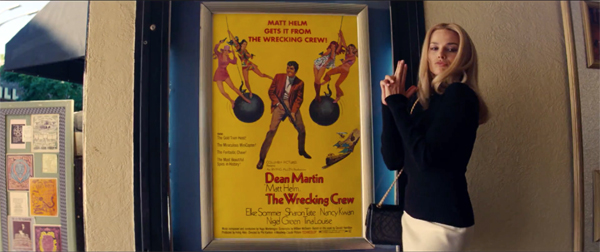

Arguably, the scene where Sharon Tate watches herself in The Wrecking Crew raises even more vexing issues about what is real and what is fictional. Unlike the clip from The Great Escape, the theatre screening shows the real Sharon Tate playing the character Freya in The Wrecking Crew. The fictional Sharon Tate watches the real Sharon Tate, along with the rest of the Bruin Theater’s audience. Yet, because Margot Robbie only pretends to be Sharon Tate for Tarantino’s camera, she doesn’t really watch herself playing the role. Obviously, Robbie belongs only to the real world. Yet Sharon Tate, as both an actual person and a fictional character, inhabits both the real world and the “realer than real world.”

Here the film indulges the Bazinian conceit that cinema has indexical properties. While making The Wrecking Crew, the film camera captured an imprint of the real Sharon Tate that preserved her being beyond the reaches of time and even death. In Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, this moment is both joyful and sad. The viewer imagines the thrill that Tate feels in watching herself on the big screen, basking in the glow of incipient stardom. Yet the delight we experience is colored by our knowledge of what happened to the Sharon Tate seen falling on Dean Martin’s camera case. Unlike Robbie’s character, that Tate is doomed to a grisly death at the hands of psychopaths.

By film’s end, however, we are forced to reevaluate where Sharon Tate fits into Tarantino’s universe. When Cliff and Rick thwart the attack of Tex Watson, Susan “Sadie” Atkins, and Patricia “Katie” Krenwinkel, both Sharon Tates appear to move solely to the realm of the “realer than real.” Like the fictional Sharon Tate played by Robbie, the actress who appeared in The Wrecking Crew also lives on in a parallel universe created by the forking of time. And the fate of that character remains completely undetermined. Now fully a part of the “realer than real,” Tarantino’s Sharon Tate might eventually snort cocaine with movie producer Lee Donowitz or bum a Red Apple cigarette from Pulp Fiction’s Mia Wallace.

Once she joins the “realer than real,” almost any fate you could imagine for Sharon Tate seems possible. And it is that sense of the actress’ unlimited horizons that gives the ending of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood its resonance. Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time films always situated viewers in the realm of myth. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, on the other hand, evokes the fairy tale.

Tarantino is known for his experimentation with narrative, and the simplicity of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s “what-if” scenario could seem like a retreat from the formal play seen in his earlier films. Yet I’d argue that Tarantino’s merging of fact and fiction is even more audacious in certain respects. It strikes me as an unconventional example of what David calls “multiple draft narratives,” like Krzystof Kieslowski’s Blind Chance or Peter Howitt’s Sliding Doors. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood gives us a second draft of history, albeit one where the key decision point is saved almost until the end of the film. And unlike Blind Chance or Sliding Doors, Tarantino doesn’t need to tell us what the different outcomes are for each of these tales. The first draft of history is one we already know.

In fact, the notion of multiple drafts offers a useful lens for all three films in Tarantino’s “counterfactual” trilogy. (The other two are Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained.) In Groundhog Day, Source Code, and Edge of Tomorrow, each iteration of the basic situation shows the protagonist inching toward his goals. They gradually progress to the point where they are able to alter destiny, either theirs or the world’s or both.

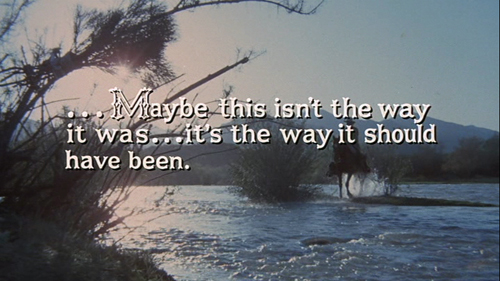

Inglourious Basterds, Django Unchained, and Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood all present images of history not as it was, but as it should have been. Such counterfactual histories run counter to the norms of speculative fictions that often present us with dystopian worlds we were lucky to avoid. (Think Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, Robert Harris’ Fatherland, or Kevin Willmott’s “mockumentary” C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America.) All of these stories depend upon our knowledge of the first draft of history. Yet Tarantino gives us second drafts that right particular historical wrongs in either small or large measure. In doing so, Tarantino gives us versions of history that are closer in spirit to his favorite movies. All three films in the “counterfactual” trilogy feature tidy resolutions. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, however, is even more self-conscious about the way Tarantino’s second draft of history takes the form of a “movie movie” climax. The realer-than-real version is the one we ought to prefer.

Paging Mr. Melcher, Mr. Terry Melcher…

If Tarantino’s conflation of fact and fiction evokes certain traits of the multiple-draft narrative, his vivid recreation of Hollywood circa 1969 illustrates another type of story popularized in American independent films and various art cinemas: the network narrative.

Tarantino has broached this form before in Inglourious Basterds. There he moves back and forth between three mostly independent storylines: 1) the Basterds’ guerrilla campaign against German soldiers, 2) Archie Hicox and Bridget von Hammersmarck’s initiation of Operation Kino, and 3) Shosanna’s plan to avenge her family’s deaths during the premiere of Nation’s Pride. SS officer Colonel Hans Landa threads through all three storylines. He orders the killing of Shosanna’s family in the opening scene. Later he shares apple streudel with Shosanna in a Paris café. Landa also investigates the scene where Hicox has been killed. In the climax, he interrogates Bridget in a scene that contains a grim allusion to Cinderella’s lost slipper.

Finally, Landa negotiates a deal with Aldo Raine’s superiors that guarantees his immunity from prosecution for war crimes.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is obviously much less plot-driven than Inglourious Basterds. Yet, as noted above, it shares a similarity in the way it interweaves the stories of three characters: Rick, Cliff, and Sharon.

It’s frequently said that Hollywood is a company town. By situating all three characters within the film and television industries, Tarantino tacitly stays faithful to that truism. The protagonists’ shared profession also facilitates the kinds of attenuated links between stories commonly found in network narratives.

Part of the fun of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood comes in recognizing the “six degrees of separation” that join all of these people, both real and fictional, in the same entertainment ecosphere. Take, for instance, one decidedly minor character: actress and singer Connie Stevens, played by Dreama Walker. At the Playboy Mansion party, Stevens listens to Steve McQueen explain the romantic triangle that has Sharon living with her current husband, Roman Polanski, and her ex-boyfriend, Jay Sebring. Stevens, though, is the ex-wife of actor James Stacy, who played Johnny Madrid in Lancer. Stacy (played in our film by Timothy Olyphant) is Rick Dalton’s scene partner for the episode of Lancer that Dalton hopes can spur his comeback. Dalton is Sharon Tate’s neighbor on Cielo Drive, the same house that Charles Manson targets as the site of the “family’s” first murder. This circuit even loops back on itself. When Stacy and Dalton first meet on set, Stacy asks Rick whether it was true that he almost got a part in The Great Escape, the same part played by McQueen.

Two characters in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood serve as nodes that connect all three storylines together. The first is Cliff, Rick’s stunt man and gofer. Although not a resident at Cielo Drive, he spends a lot of time in Rick’s home and thus is privy to what happens in Sharon’s abode. This is especially evident when Cliff repairs Rick’s fallen TV antenna. The camera is aligned with him as he overhears Sharon playing a Paul Revere and the Raiders album. He also notices Charles Manson approaching the Polanski residence. Tarantino’s casting of Damon Herriman as Manson is likely an allusion to the television show, Justified. Herriman played Dewey Crowe alongside Olyphant.

Justified was also an adaptation of Elmore Leonard’s “Raylan Givens” books. Tarantino has long admired Leonard’s work as a writer of both westerns and crime novels.

Employing a redundancy that befits Hollywood storytelling, Cliff gets linked to Sharon’s storyline in other ways. While working as Rick’s stunt man for an episode of The Green Hornet, he gets involved in a dust-up with Bruce Lee. Lee gave Sharon Tate some pointers on fighting as she prepared for her role in The Wrecking Crew. And in real life, the martial arts legend was recommended for the role of Kato on television’s The Green Hornet by Sebring, Tate’s former boyfriend.

Perhaps Cliff’s most important role in the film’s network involves his dalliance with Pussycat, one of the many young women who viewed Manson as a kind of guru. Cliff picks up Pussycat as a hitchhiker and gives her a ride back to the Spahn ranch. Having worked on the ranch back when it was an active production site, Cliff grows concerned for the safety of its owner, George Spahn. Cliff notices how the Manson clan has taken over and is troubled by its weird vibe. Determined to see George for himself, Cliff forces his way into George’s house over the objections of the Manson girls, especially Squeaky. George seems careworn, but Cliff finds that there is little he can do for him.

When Cliff sees a pocketknife sticking out of his front tire, he confronts Clem, one of Manson’s followers. The conflict becomes physical. Cliff breaks Clem’s nose with one punch and then proceeds to beat him to a bloody pulp.

This proves to be a dangling cause that gets resolved in the film’s climax when Cliff recognizes Tex, Sadie, and Katie as people he met at the Spahn ranch.

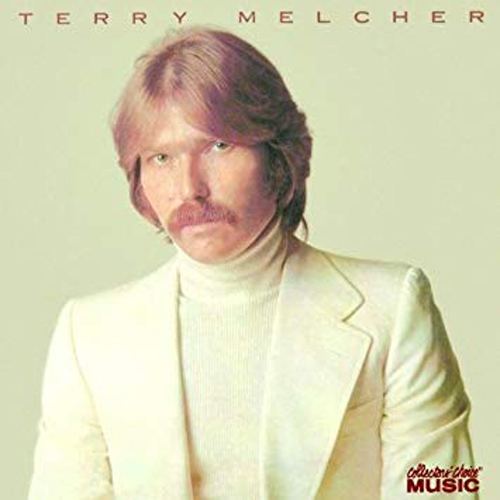

The other character who links the storylines together is one we never see: record producer Terry Melcher. Melcher is the “Terry” that Manson mentions when he visits Cielo Drive in the scene described above. Later, Tex reminds Sadie, Katie, and Linda that Charlie directed them to go to the place where Terry Melcher lived and kill everyone inside.

Although these are the only explicit references to Melcher, he is indirectly represented in several other aspects of the film. Here it helps to know a little about Melcher’s career and Manson lore. Even if Melcher’s name draws a blank, you likely know many of the bands he worked with: the Byrds, the Mamas and the Papas, and Paul Revere and the Raiders.

All these musicians crop up in one way or another in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood. Melcher’s last major credit of the 1960s was as producer of the Byrds’ Ballad of Easy Rider. When Rick berates Tex for parking his car on Cielo Drive, he yells, “Hey, Dennis Hopper! Move this fucking piece of shit!” Rick’s insult fits with his general disdain for hippies. But it also alludes to Easy Rider by comparing Tex’s look to that of Hopper’s character, Billy.

Two of the Mamas and the Papas – Michelle Phillips and Cass Elliot – both appear in the party scene at the Playboy mansion.

We also hear the Mama and the Papas’ big hit, “California Dreaming” in a cover version by Puerto Rican singer José Feliciano. And when the car driven by Tex crawls up Cielo Drive, the music issuing from the Polanski residence is the Mamas and the Papas’ “12:30: Young Girls are Coming to the Canyon.” Even before Tex’s directive to the Manson girls, Tarantino has given us a subtle reminder that Melcher was Charlie’s intended, if indirect, target.

Finally, Sharon plays Paul Revere and the Raiders’ “Good Thing” and “Hungry” on a hi-fi in her bedroom.

The choice of music is especially fitting since the band’s lead singer, Mark Lindsay, lived in the same house on Cielo Drive with Melcher and his then girlfriend, Candice Bergen.

Beyond these musical references, Melcher’s history with Manson informs Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood in another way. Melcher recorded some demos of Manson’s songs, and even discussed making a documentary about Manson’s commune at the Spahn Ranch. In testimony at trial, Melcher said that any possibility of a record contract with Manson was sundered when Charlie asserted that he’d never join a musicians’ union. Manson’s staunch refusal was rooted in his desire to avoid entanglements with the establishment. Yet union membership was a condition for any contract with Melcher’s label, Columbia records. Another factor in Melcher’s decision was his assessment of Manson’s talent. Charlie couldn’t sing.

Although Melcher publicly stated that he only considered Manson’s musicianship, he privately expressed concerns about Charlie’s mental stability. These were heightened when he visited the Spahn Ranch and witnessed Manson in a physical altercation with a drunken stunt man. Tarantino more or less recreates this episode in his film, substituting Cliff for the unnamed stunt man and the hapless Clem for Charles Manson.

More importantly, Melcher is the son of screen legend Doris Day and stepson of agent/manager/producer Martin Melcher. In Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, he becomes the ideal, if absent, symbol of the combined worlds of music, television, and film that Tarantino so lovingly details.

How the West was lost

Los Angeles circa 1969 is presented as the epicenter of the American entertainment industries. It’s a place where a hairdresser like Jay Sebring rubs shoulders with action stars, TV cowboys, ingénues, film directors, and pop stars –and make $1000 a day to boot! The constant stream of hits from KHJ radio is as ubiquitous as the many movie posters, billboards, and theater marquees that feature Hollywood’s latest and greatest.

Tarantino’s press kit for Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood makes reference to Joan Didion’s famous observation in “The White Album” that “the Sixties ended abruptly on August 9, 1969, at the exact moment when word of the murders on Cielo Drive traveled like brushfire through the community.” Most critics take Didion’s reference to the Sixties as shorthand for the end of the “peace and love generation.” Yet Tarantino’s slightly revisionist take suggests it’s not only the youthquake that died, but also a certain strain of Hollywood filmmaking that passed with it.

Although I don’t doubt their historical accuracy, the litany of titles that appear throughout Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood feels as curated as any of Tarantino’s music soundtracks. Some, like 2001: A Space Odyssey, are films that entered the canon of great sixties cinema. Others, like The Night They Raided Minsky’s, are early films by directors who’d later achieve greatness. (In this case, William Friedkin, who won an Oscar in 1972 for The French Connection.)

But many, like Lady in Cement, Tora, Tora, Tora!, Krakatoa: East of Java, Mackenna’s Gold, C.C.& Company, and even The Wrecking Crew, are largely forgettable movies.

Tarantino clearly has affection for all of the drive-in theaters and Hollywood picture palaces where these titles played. But the titles themselves are evidence of the industry’s struggle to adapt to new tastes and a rapidly changing media landscape. Old-school show biz types, like Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra, continued their success as singers and television personalities. But their careers as actors had functionally ended by 1969. And the efforts to keep them relevant often seemed either strikingly anachronistic or just plain weird.

In the opening scene of Lady in Cement, Frank Sinatra fights off a small school of sharks while he is examining the body of a nude woman who, like Luca Brazzi, sleeps with the fishes. And yes, the scene is as ludicrous as it sounds. If this is what became of Hollywood’s once great tradition, it is hard not to think we should just let it pass.

Yet, the fear of obsolescence also explains the oversize role that Tarantino gives to the Western as part of this changing landscape. True Grit and The Wild Bunch were among the summer of 1969’s biggest hits. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid would eventually become the year’s top-grossing film. All three Westerns feature cowboy heroes that are either aging, outmoded, or both. They reminded contemporary viewers that horse riders would soon yield to horseless carriages, the lone bounty hunter would soon be supplanted by paramilitary detective agencies, and the humble six-shooter can’t match the lethal power of a Mexican army machine gun.

In retrospect, though, the popularity of the Western in 1969 represents the genre’s last gasp. Studios continued to make Westerns during the 1970s, but only three – Jeremiah Johnson, The Outlaw Josey Wales, and The Electric Horseman – would surpass $10 million in rentals in the entire decade.

On television, such long-running series as Gunsmoke, Bonanza, and The Virginian had their last round-ups. The networks tried their hands at new Westerns, like Alias Smith and Jones (below), Hec Ramsey, Dirty Sally, and Lancer, but they were all short-lived. At the start of the 1980s, the genre was completely moribund. Subsequent efforts to recapture the Western’s former glory were mostly the equivalent of flogging a dead pony.

As a total cinephile, Tarantino is entirely aware of this aspect of the genre’s history. This is signaled quite explicitly in the decrepit condition of the Spahn Movie Ranch. Yet Tarantino also uses Rick’s career arc to signify its downward trajectory.

No character in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is as strongly associated with the Western as Rick. His home is filled with collectibles like his Hopalong Cassidy coffee mugs. His walls are decorated with posters for The Golden Stallion and A Time for Killing. On set, he reads pulp oaters like Ride a Wild Bronc to relax between takes.

By using Rick to dramatize the twin declines of both Old Hollywood and its “bread and butter” genre, the narrative arc of Tarantino’s drugstore cowboy is one suffused with nostalgic melancholy. The key moment in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood occurs when Rick breaks down telling the story of Easy Breezy to Trudi Fraser, his Lancer co-star. He describes Easy “coming to terms with what it’s like to feel slightly more useless each day.”

The various threads of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s network finally knot together in the Manson family’s attack on Cielo Drive. At the moment of truth, it is telling that Rick reaches not for a firearm, but for the prop flamethrower he wielded in The 14 Fists of McCluskey. By recalling the moment when Rick shouts, “Anyone here order fried sauerkraut?”, Tarantino reminds us that violent spectacle and snappy quips will eventually replace the Western’s ritualistic showdowns.

Still, it is a musical allusion to the Western that gives Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood its final grace note. Cliff and Rick have thwarted the Manson family’s attack. The ambulance takes Cliff to the hospital. Rick offers an explanation of what just happened to his neighbors. Jay recognizes Rick as television’s Jake Cahill. Via the intercom, Sharon invites him to come up for a drink. As Rick walks to the house, we hear the start of Maurice Jarre’s “Lily Langtry” [sic] from his score for The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean.

John Huston’s film begins with an expository title shown below that highlights the western’s tendency toward self-mythology. It is especially apt for Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s counterfactual history.

Jarre’s cue, though, appears in a scene where the renowned actress Lillie Langtry finally visits Judge Bean’s Texas town. Langtry is given a tour of the Bean’s house, now converted into a museum that also acts as a shrine to her. Bean worshipped Langtry, but tragically dies before he gets to meet her. Tarantino inverts both Huston’s sad ending and its dramatization of missed opportunity. By altering the course of history, the cowboy in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood gets to be the real-life hero rather than the TV heavy. Rick also gets to meet the actress he’s admired from afar. Rick and Sharon are still both married to other people. But their chance meeting in the film’s epilogue feels more than anything like a dream fulfilled.

A star is unborn

In the previous section, I dwelt on the role of the Western in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood because of its symbolic significance in capturing a particular historical moment. But Tarantino borrows quite freely from another narrative prototype: the show-biz tale. In fact, while walking out of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, I wondered aloud if it was Tarantino’s twisted take on A Star is Born.

Like A Star is Born, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood centers on a male performer whose career has started to decline and a female newcomer whose star is on the rise. Moreover, Rick’s drinking problems create an obstacle to his comeback in much the same way that alcohol contributes to the downfall of the male protagonists in all four versions of A Star is Born.

Tarantino, though, subtly alters this template in two ways. First, he depicts his two stars as neighbors rather than as a romantic couple. Secondly, he cleverly depicts Rick’s career arc as an inverse mirror of Sharon’s.

Tate was an Army brat who grew up in Europe. Her earliest work was as an extra in Italian films. She moved to Hollywood in 1962 and got her break playing Jethro Bodine’s girlfriend on The Beverly Hillbillies. In the mid-sixties, Tate made the move to films, appearing in Eye of the Devil and The Fearless Vampire Killers.

It was during production of the latter that Tate met her future husband, Roman Polanski. Tate’s role in Valley of the Dolls further enhanced her status as an “up and comer.” In 1968, Tate earned a Golden Globe nomination in the category of “Most Promising Newcomer — Female.”

In direct contrast, Rick’s career begins in Hollywood and ends in Italy. Rick enjoys early success with Bounty Law and The 14 Fists of McCluskey. But soon finds himself reduced to guest star roles on television. Against his better judgment, Rick agrees to star in four Italian quickies. Two of these are spaghetti westerns directed by Sergio Corbucci, a Tarantino fave who created the popular “Django” character. Rick returns to Hollywood but his future is uncertain. He could be the next Clint Eastwood, star of A Fistful of Dollars and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Or he could be the next Richard Harrison, star of $100,000 Dollars for Ringo and Secret Agent Fireball.

If this were all there was to the comparison, it would hardly be worth mentioning. But Tarantino hints at other parallels through a much more obscure and convoluted cinematic reference. An auteur as shrewd as Tarantino would undoubtedly remember that the Rolling Stones’ “Out of Time” –used in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood under shots of Rick’s return from Rome – was previously featured in the opening sequence of Hal Ashby’s Coming Home.

The connection to Ashby’s film is strengthened by the casting of Bruce Dern as George Spahn, a role originally intended for Burt Reynolds. Early in his career Dern played Jane Fonda’s uptight, martinet husband in Coming Home. More importantly, during Coming Home’s climax, Dern’s character commits suicide by wading into the ocean to drown himself, just as James Mason does at the conclusion of George Cukor’s version of A Star is Born.

Which brings us back to Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s controversial ending. Earlier I discussed the resemblance between its counterfactual history and multiple draft narratives. Here I want to discuss it as an illustration of the caprice of fame.

Much more than the endings of Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained, the climax of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood feels both resolved and unresolved. Hitler’s violent death in Inglourious Basterds surprised audiences who first saw it in theaters. Yet the historical record indicates that the Basterds simply saved Hitler the trouble of later killing himself and his wife, Eva Braun. At the conclusion of Django Unchained, the protagonist’s revolt clearly hasn’t ended slavery as a “peculiar institution.” But its story of personal revenge remains deeply satisfying.

The ending of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood left me with more questions than answers. I get it. Sharon Tate lives instead dying at the hands of the Manson family. Tarantino gives us the Hollywood happy ending that this story lacked in reality. But what’s next?

Do the deaths of Tex, Sadie, and Katie mean that Leno and Rosemary LaBianca also survive? Maybe. Perhaps the loss of three members of the cult might cause the others to reevaluate their loyalty to Manson. Perhaps Manson himself would reevaluate his plan to trigger a race war.

But maybe not. If Manson were the hero of Tarantino’s grindhouse climax rather than its villain, one could easily imagine the film running another twenty minutes with Manson vowing to get even. You might imagine it as something like the surprising “second climax” of Django Unchained. After mourning the loss of his compatriots, Charlie would proclaim. “The fires of Hell will descend upon the Hollywood hills. This time it’s personal.”

Perhaps the bigger question is whether Sharon continues to be the “It” girl during the next phase of her career. The allusions to A Star is Born suggest a steady upward trajectory. But the reality is that success depends upon a certain amount of luck. It is never assured. A few box office bombs and Sharon Tate might be reduced to the same sort of TV guest spots that Rick is doing.

In this way, the ending of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood asks us to consider a potential paradox. Did Sharon Tate become more famous in death than she ever would have been in life?

The theme of talent tragically cut down in the prime of life is a hoary cliché of the celebrity biopic. Tarantino is smart to steer clear of it. Yet whenever we watch a film like Prefontaine, Beyond the Sea, or Lenny, one starts to wonder, “Would anyone bother to make this film if its subject had lived?”

To be sure, the totality of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood shuns any pat answer. Cass Elliot of the Mamas and the Papas died at age 32. Initial reports said she choked on a ham sandwich in the midst of having a heart attack. I remember the media reports when Mama Cass passed in 1974. But does anyone who didn’t live through that moment?

James Stacy, star of Lancer, nearly died in a deadly motorcycle accident. (Tarantino hints at this fate by showing Stacy, sans helmet, riding his steel horse away from his trailer.) Stacy survived, but lost an arm and a leg as a result of his near fatal injuries. He eventually made a comeback in 1977 and even earned an Emmy nomination for his work on Cagney and Lacey.

Yet, if you mention James Stacy during dinner conversation tonight, I suspect your companion will ask, “Who?”

And then there is the scene where Pussycat and the other Manson girls walk past a large mural of James Dean in his iconic pose from Giant. Dean was certainly famous during his lifetime. But he became a legend at age 24 after his Porsche Spyder collided with another car, snapping his neck.

Would Sharon Tate have achieved stardom had she lived? God only knows. I certainly don’t. I do know one thing, though. Being a victim of the “crime of the century” preserved Tate’s image in popular memory with a vividness that very few human beings on this earth ever achieve.

Margot Robbie’s performance as Tate is extraordinary. She reminds modern viewers of the verve, spirit, and sensuality that Sharon brought to the screen. Yet it is the image of Tate as a tragically murdered heroine that Tarantino, like Mark Macpherson in Laura, appears to have fallen in love with. And it is this image that continues to haunt me some fifty years after Tate’s death.

Thank you to David and Kristin for their comments onf an earlier draft of this post. Thanks also to JJ Bersch and Maureen Rogers for letting me bounce some of ideas off them.

Vincent Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders remains the most comprehensive account of the Tate-LaBianca murders. Tom O’Neill, though, has spent the last 20 years investigating Manson’s crimes. His new book, Chaos: Charles Manson, the C.I.A., and the Secret History of the Sixties, claims that Bugliosi’s investigation was deeply flawed. Instead, his research suggests that Manson was a drug trafficker and C.I.A. operative. For O’Neill, the notion that Bugiliosi saved Los Angeles from a hippie death cult is wrong. The motive for the crimes was both simpler and more quotidian. All of Manson’s murders were the result of drug deals gone wrong. An interview with O’Neill can be found here.

The story that Terry Melcher witnessed a fight at the Span Movie Ranch between Charles Manson and a drunken stunt man sounds apocryphal. Yet it appeared in The Telegraph’s obituary for Melcher, which was first published in 2004. I haven’t been able to independently corroborate that story with another source. However, even if it isn’t true, it is part of Manson lore. I saw the same story repeated on at least three other websites. Doris Day’s death in May spawned the publication of a handful of articles about her relationship with Terry. They can be found here, here, and here. An brief overview of Melcher’s career as a record producer can be found in Rolling Stone’s obituary.

For those interested in learning more about Sharon Tate’s life, I recommend Sharon Tate: Recollection. It was written by Tate’s mother Debra. It also features a foreword by her husband, Roman Polanski.

Mark Harris’s Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood and Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls survey the momentous changes taking place in the film industry during the late 1960s.

Bruce Fretts provides a fairly thorough overview of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s voluminous pop culture references.

Several articles have also appeared that address different aspects of the film’s production. An interview with choreographer can be found here. Cinematographer Robert Richardson and production designer Barbara Ling detail their efforts to recreate the sets of the TV show Lancer here. Richardson also discussed Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s visual influences in a Hollywood Reporter podcast.

An interview with Mary Ramos, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s music coordinator, can be found here. Guides to Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s music soundtrack can be found here, here, and here.

An analysis of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s box office implications is found here.

Finally, the release of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood has occasioned a number of think pieces that address aspect of the film’s counterfactual history and its identity politics. Here philosopher David Bentley Hart discusses the moral implications embedded in Tarantino’s counterfactual trilogy.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s gender politics is addressed here. The author, Aisha Harris, compares Tarantino’s depiction of Sharon Tate to other female characters in his filmography. Finally, zeitgeist readings of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood in relation to the current political landscape can be found here and here.

Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood.

Oscar’s siren song: The return: A guest post by Jeff Smith

A Star Is Born.

As you probably know, Jeff Smith has been our collaborator on Film Art: An Introduction and our Criterion Channel series “Observations on Film Art.” For the last few years (here and here and here), Jeff has offered his thoughts on the Academy’s music nominees. This time around, he concentrates on the songs.

Here’s a brief preview of the Best Original Song category in this year’s Academy Awards. I also include a prediction for this year’s winner. Of course, I’d be the first to admit I don’t even win my own Oscar pool. So you’ll want to take that into account before making any wagers.

A good old-fashioned tune

Mary Poppins.

The Academy has a long history of nominating songs from live action and animated musicals. This year is no exception.

“The Place Where Lost Things Go” from Mary Poppins Returns fits that bill, giving Disney a third straight nomination in this category. (“Remember Me” from Coco and “How Far You’ll Go” from Moana are the others.) Like the Sherman Brothers, who wrote songs for the original Mary Poppins, Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman derived inspiration from British Music Hall.

In fact, although actor Lin-Manuel Miranda insisted that he didn’t want his character to sound like Hamilton, Shaiman and Wittman wrote a patter section of “A Cover is Not a Book” for him, enabling Miranda to show off his unique skill set. With its tricky wordplay and fast pace, the classic patter song is a forerunner of the rhymes spat by rap and hip-hop artists. As Shaiman noted, “So we got very lucky there because we didn’t want to feel like we were pandering to the audience, to supply Lin with rap that would seem anachronistic.”

“The Place Where Lost Things Go” sits on the opposite side of the musical spectrum as a soft, mid-tempo ballad scored for strings and winds. Fans of the original Mary Poppins will note that it bears more than a faint resemblance to “Stay Awake.” Both songs are sung to the Banks children at bedtime in an effort to inveigle them to sleep. Whereas “Stay Awake” shows the über-Nanny using reverse psychology, “The Place Where the Lost Things Go” is a paean to memory, loss, and grief. The children’s mother has recently died and they further risk losing their beloved house. Mary Poppins reassures the children that they will be reunited one day with all their loved ones and that, in the meantime, their mother will forever have a place in their hearts.

The number is beautifully sung by Emily Blunt and it captures the sense of melancholy that gives Mary Poppins Returns its emotional heft. Still, it seems like a long-shot to take home the award. I admire Marc Shaiman’s work. He has written some absolutely iconic scores in the past, like The American President. And I’d love to see him recognized this Sunday, even if it is just for his phenomenal work on South Park: Bigger, Longer, and Uncut. But I fear that an Oscar statuette with his name engraved upon it is also in the place where the lost things go.

When corn meets pone

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs.

The second nominee is David Rawlings and Gillian Welch’s “When a Cowboy Trades His Spurs for Wings.” It appears in the comically violent opening story of the Coen Brothers’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. It is sung as a duet by the titular character and the Kid, a mysterious gunslinger dressed in black. Buster has just been shot dead in a duel. In the song, the Kid imparts some lessons learned from his short, rugged life as a cowboy with Buster chiming in to provide harmony. Kid’s grimly acknowledges that he will suffer the same fate as Buster. It is just a matter of time.

Rawlings and Welch are long-time collaborators, having worked together on the former’s debut album. Rawlings has also produced albums by Welch and by Willie Watson, who plays the Kid. Adding to the sense of family reunion is the fact that Welch provided the voice of one of the Sirens in O Brother Where Art Thou? Among those enchanted by the Sirens? You guessed it – Tim Blake Nelson, who plays Buster.

In an interview in Variety, Welch describes the absurdity of the original pitch the Coens made to her and Rawlings:

It was a pretty straightforward thing: “Well, we need a song for when two singing cowboys gun it out, and then they have to do a duet with one of ‘em dead. You think you can do that?” “Yeah, I think we can do that,” she laughs.

In crafting the song, Rawlings and Welch pull off a rather neat trick. They’ve created something evocative of the “singing cowboy” films that inspired the first segment of The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. Yet is also connects with a larger tradition of mournful ballads that are part of folk and country music history. A lilting Texas waltz, the number is sparsely orchestrated, relying largely on guitar, harmonica, and vocals. The lyrics also make reference to a “bindling sheet.” As Welch noted, the word “bindling” was something she and Rawlings made up as a gesture toward the Coens’ fondness for anachronistic language. Yet it also works as a clever allusion to the “white linen” that is wrapped around a dying cowboy’s body in “Streets of Laredo.”

As was the case with Mary Poppins Returns, this song perfectly blends music and narrative, beautifully capturing the darkly humorous sensibility characterizing the Coens’ career. The lyrics are solemn, but Tim Blake Nelson’s yodeling lightens the tone to keep it from seeming maudlin. If I had a vote to cast, this is where I’d put it. Yet my gut tells me that the Academy’s beacon will shine on one of the other nominees.

A song for one of the Supremes

Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

The third nominee, “I’ll Fight,” was written by Diane Warren, a longtime Academy favorite. The song represents Warren’s tenth nomination, but she has never taken home top honors. This year, in an ironic twist, she may lose out to former co-writer Lady Gaga. (The two were nominated for “Til It Happens to You” in The Hunting Ground.) Warren admits that “I’ll Fight” is another of her “call to arms” songs as she has turned more of her energies toward films that support social causes.

One can easily make a solid prima facie case for “I’ll Fight” as the song to beat. It features a strong, soaring vocal performance by Jennifer Hudson, a previous Oscar winner for Dreamgirls.

Warren’s melody and lyric capture the inspirational vibe that is found in several previous winners, most recently “Glory” from Selma. And, of course, Warren herself seems long overdue.

Even so, “I’ll Fight” has a number of things working against it. It is featured in a documentary, and documentaries usually don’t get the exposure of more mainstream releases. It appears over The RBG’s closing credits, which mostly restricts the song to a summative function. And, unlike “All the Stars” and “Shallow,” the song failed to chart, an indication that it didn’t get much exposure in the music marketplace. I feel confident that Warren’s opportunity to make an acceptance speech will come someday. But on Oscar night, she’ll once again be the “bridesmaid” rather than the “bride.”

The battle of the titans

Black Panther.

For me, the race comes down to the remaining two nominees: “All the Stars” from Black Panther and “Shallow” from A Star is Born. Both tracks have gotten extraordinary exposure outside the films in which they appeared. The former was a chart hit in 25 countries, garnering steady radio airplay and thousands of streams and downloads in the process. The latter arguably did even better, charting in 40 countries, selling nearly 600,000 downloads and accruing almost 150 million streams. Both songs are fueled by star power: hip-hop sensation Kendrick Lamar for “All the Stars” and pop diva Lady Gaga for “Shallow.”

Lamar has just the right profile to woo Academy voters, even those in the music branch for whom “big beatz” and “flow” seem like foreign concepts. He has won thirteen Grammy Awards as well as the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for Music, becoming the first artist to do so from outside the domains of classical and jazz music. Billboard even compared Lamar to Shakespeare.

Although some music critics argue that “All the Stars” is not entirely typical of Lamar’s and SZA’s respective styles, it does fit beautifully with the overall vibe of Ryan Coogler’s pathbreaking film. The song begins with loping rhythms, electronic textures, and auto-tuned vocals. When Lamar drops the beat in the chorus, “All the Stars” gains intensity thanks to the layering of additional synthesizers and SZA’s melismatic topline.

The overall effect is one that neatly draws together Black Panther’s principal settings, being equal parts Wakanda and Oakland. The tension in the lyrics between the sung choruses and Lamar’s linguistic turns also restages the film’s central conflict: Prince T’Challah’s policy of peaceful co-existence vs. Killmonger’s thirst for violent world revolution. Appearing over the end credits, the number also works brilliantly with the shifting lines, shapes, and textures of the sequence’s graceful animation.

Lady Gaga, of course, supplies “Shallow” with its vocal fireworks. But she shares her nomination with three other collaborators, all of whom cut pretty large figures in the world of popular music.

Chief among them is superproducer Mark Ronson, who twirled the knobs on Gaga’s fifth album, Joanne in 2016. Ronson is perhaps best known for his smash hit, “Uptown Funk.” Yet, Ronson had already won three Grammy’s for his production of Amy Winehouse’s Back to Black long before he gave us his Bruno Mars earworm. Besides his production work for Gaga, Winehouse, and Mars, Ronson has collaborated with a “who’s who” of current stars and pop music legends: Adele, Lily Allen, Miley Cyrus, Kaiser Chiefs, Chance the Rapper, Janelle Monae, Duran Duran, Nile Rodgers, and Paul McCartney.

One of Ronson’s other songwriting partners, Anthony Rossomondo, shares the nomination for “Shallow.” Rossomondo is a guitarist and trumpet player who was a founding member of Dirty Pretty Things and toured with the Libertines as Pete Doherty’s replacement. Fans of British television might also remember Rossomondo as Pete Neon in The Mighty Boosh, the surrealist comedy series about a pair of failed musicians working in an alien shaman’s magic shop.

Rounding out the quartet of songwriters is Andrew Wyatt, still another songwriting partner of both Ronson and Gaga, who also penned tunes for Mars, Lil’ Wayne, Beck, Florence + the Machine, and former Oasis bad boy, Liam Gallagher. Wyatt also has previous experience writing for film. He composed four songs for the Hugh Grant/Drew Barrymore romantic comedy, Music and Lyrics, including the wonderful pastiche of eighties New Wave, “PoP! Goes My Heart.”

With so much musical talent on board, it is hard to see how “Shallow” could miss. Yet the song’s many virtues are enhanced by its perfect placement in the story. It was a lot to expect that one song could deliver something that a) pays off the romantic sparks of Ally and Jackson’s initial flirtation; b) signifies Ally’s leap of faith as she returns to the stage to complete Jackson’s arrangement of her song; and c) convince the audience that Ally could legitimately be the proverbial overnight sensation of the film’s title. “Shallow” delivers on all that and more.

The song begins with Jackson singing, “Tell me something, girl.” The first verse is sparely arranged for just voice and acoustic guitar. Jackson essentially baits Ally into claiming a spotlight he believes is rightfully hers. When Ally comes on stage, she begins the second verse in the lower part of her vocal register, adding a husky sensuality that captures the slow-burn of the couple’s simmering passions. Piano, violin, and pedal steel guitar slightly thicken the arrangement while maintaining the relatively soft dynamic level. An octave leap leads into the chorus, which Ally belts out with newfound confidence.

The lyrics serve as a metaphor for the character’s personal journey, her willingness to take the emotional and professional risks that Jackson had encouraged. This is Ally’s moment of self-realization. Yet it also foreshadows the relationship’s failure by previewing a future in which her stardom will overtake his.

This is followed by Jackson and Ally finally harmonizing together on the phrase, “In the shallow, the sha-ha-low.” Their voices blend, suggesting the consummation of their romantic connection onstage, if not yet in bed. Ally follows with a kind of vocal cadenza. No longer bound by lyrics, she sets free the “yargh” in her voice that rock critic Greil Marcus famously ascribed to Van Morrison’s Irish soul.

The addition of drums and bass enhance the big crescendo that leads into the final chorus. Jackson joins Ally at her microphone and the two finish the song with a final duet. The song is in G major, but ends on an E minor chord, another subtle hint of the sadness that ultimately consumes couple’s relationship.

As an Oscar nominee, “Shallow” has a lot to offer. It is a duet between a major movie star and a major star of the recording industry. It not only pays off a previous dangling cause, but also foreshadows later plot developments. Best of all, it takes the audience on an emotional journey that symbolizes the characters’ story arcs in microcosm. If the snatch of “Shallow” heard in the A Star is Born trailer proved surprisingly meme-worthy, the full performance of it in the film was indelible. Moreover, in a cheeky bit of self-mythologization, it invites viewers to consider “Joanne,” the flesh-and-blood being that sits just behind the Gaga mask.

Prediction: “Shallow”

I likely tipped my hand earlier, but I fully expect Lady Gaga and company to add Oscar to the Grammy and Golden Globe they’ve already won. If that happens, I’ll be content with the result, even if the memory of Tim Blake Nelson and Willie Watson’s duet tickles me every time I think of it. I’ve enjoyed Mark Ronson and Lady Gaga’s music for more than a decade. And if nothing else, an Oscar for Andrew Wyatt will balance the scales of justice. Back in 2008, I felt Wyatt was robbed when he failed to secure a nomination for a song Billboard called “the greatest fake 80s song of all time.” Well, if I see Wyatt clutching an Oscar come Sunday, you’ll hear a little PoP! go in my heart.

For an alternate take on this year’s music nominees, a real pop star from the eighties, Thomas Dolby, offers his perspective here. A report on a panel discussion at the Los Angeles Film School featuring several of the nominees can be found here.

Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman talk about their work on Mary Poppins Returns here and here.

Gillian Welch discusses working with the Coen Brothers on The Ballad of Buster Scruggs here and here.

Diane Warren offers her perspective on writing “empowerment anthems” here and here. A deep dive into Warren’s career can be found on a Hollywood Reporter podcast featuring the 10-time Oscar nominee.

Finally, much ink has been spilled about the process of writing “Shallow” for A Star is Born. You can read more here and here and here and here.

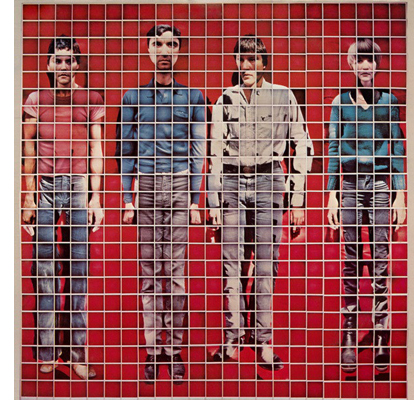

Jeff Smith has provided us many guest blogs related to film music, most recently his discussion of the score for True Stories.

Music and Lyrics (2007).

From transistors to transmedia: Talking Heads tell TRUE STORIES

True Stories.

Jeff Smith is no stranger to this blogsite. He has written several entries, some based upon his Criterion Collection commentaries for FilmStruck, others on topics related to film sound and scoring. Here he brings his massive expertise to bear on the music of True Stories, newly available in a 4K transfer from Criterion.–DB

Jeff here:

As promised, this is a follow-up blog to David’s discussion of True Stories and its collage of tabloid culture, kitsch, Performance Art, Robert Wilson, Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons, and Our Town. At least some of these connections also characterize the New York music scene in the 1970s from which Talking Heads emerged. Buoyed by the energy of punk and New Wave, Byrne had long straddled the boundaries between mass culture and the avant garde.

As before, Andy Warhol serves as something of a role model. Besides designing album covers for mainstream pop performers, such as the Rolling Stones, Billy Squier, and Diana Ross, Warhol also served as the nominal producer of The Velvet Underground & Nico. The artist himself is also the subject of David Bowie’s “Andy Warhol” from Hunky Dory and Lou Reed’s “Andy’s Chest,” an outtake that eventually surfaced on VU, the 1985 compilation of Velvet Underground miscellany.

Working in the opposite direction, Byrne and company’s connections to the Manhattan cultural scene gave their work a kind of artistic credibility. Yet their avant garde impulses were always counterbalanced by a veneration of the soul, funk, and blues music that shaped rock and roll’s art and history. In what follows, I trace the long and winding road Talking Heads took in their journey to True Stories, both as film and as album.

Making the scene

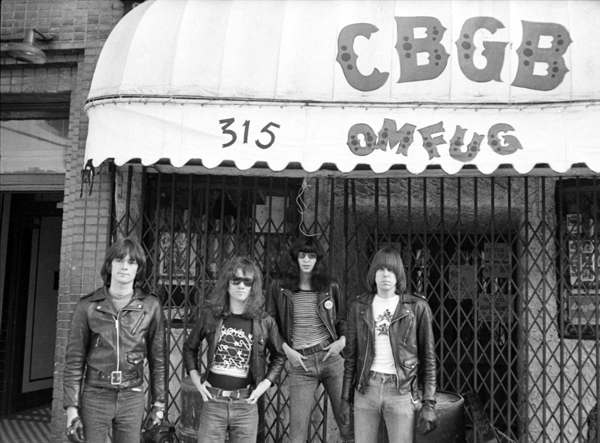

The Ramones at CBGB in the 1970s.

David Byrne’s band, Talking Heads, is almost certainly the most successful group to emerge from the downtown New York music scene of the late 1970s. Of the eight albums the band released between 1977 and 1988, seven of them were certified either gold or platinum. Little Creatures, the album released just before True Stories, went double platinum, selling more than two million units. So did Stop Making Sense, the soundtrack to their concert film directed by Jonathan Demme.

At the start of their recording career, much of the energy surrounding the New York music scene centered on the venerable East Village club, CBGB. Its name was short for “Country, Bluegrass, and Blues.” Yet the bands who came to be identified with the venue were about as far away from roots music as you could get. Initially, CBGB was associated with the emerging American punk rock scene. The Ramones were frequent performers as were the Plasmatics, Richard Hell and Voidoids, and Johnny Thunders’ band, the Heartbreakers.

Yet the range of musical styles represented at CBGB ventured quite far afield from the sped-up, chainsaw guitar sounds of punk. Patti Smith channeled her inner Rimbaud over Lenny Kaye’s Nuggets-inspired guitar lines. Television featured the evocative string-bending of Tom Verlaine. who stretched out in long solos using modal scales that fused Ravi Shankar with John Coltrane. James Chance and the Contortions showcased the wild saxophone playing of their frontman, specializing in a peculiar form of avant-funk jazz. Blondie began by refashioning sixties garage rock into their own brand of punk. But their style became more eclectic, branching out to include disco, calypso, and rap. They attained a huge crossover success in the process, thanks to lead singer Debbie Harry’s sex appeal and sultry alto.

Talking Heads sounded like none of these. “New Feeling,” the second track on their debut album, established the template for the band’s music: skittering guitar lines, tightly wound rhythms, and David Byrne’s strangled yelp. Its spare, spiky pop sound featured the rhythmic interplay of Byrne’s and Jerry Harrison’s guitar lines and the precise sixteenth note fills of drummer Chris Frantz.

Talking Heads 77 occasionally added elements that slightly broadened their musical palette. Think of the steel drum sounds that color “Uh-Oh, Love Comes to Town” or the loping electric piano chords of “Don’t Worry About the Government.” Indeed, the latter wouldn’t sound out of place in a Sesame Street bumper.

Yet, the album’s flagship single was “Psycho Killer” for a reason. Its nervy energy epitomized the group’s sound in its early days at CBGB. This was rock and roll to be sure. But it seemed like the kind of thing the subject of Edward Munch’s The Scream would dance to if he ever got off that bridge.

Talking Heads’ follow-up, More Songs About Buildings and Food, initiated a period of fruitful collaboration with producer Brian Eno. Using synthesizers and other keyboard instruments to flesh out the band’s sound, Eno nudged the Heads toward more danceable tunes. Built on Tina Weymouth’s pliant, bouncy bass lines, songs like “Found a Job” and “Stay Hungry” saw the band incorporating elements of seventies funk, soul, and disco. The band’s cover of Al Green’s “Take Me to the River” also gave the group their first chart hit.

That single’s slow climb peaked the same week of Talking Heads’ television debut on Saturday Night Live. For many viewers, this was their first encounter with Byrne’s “Norman Bates meets Pete Townshend” persona. And, even though Byrne’s hipster nerd desperation seemed the absolute antithesis of Green’s “lover man” come-on, his apparent interest in exploring black musical idioms felt almost painfully sincere.

Bringing Noho to the bush of ghosts

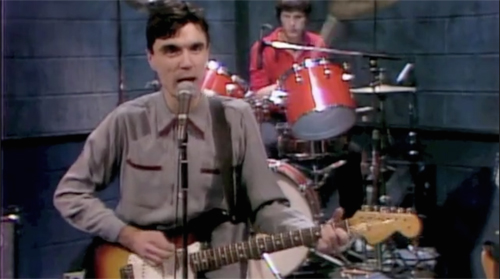

Music video for Once in a Lifetime.

Over the next three albums, the Heads’ collaboration with Brian Eno pushed them even deeper into world musical cultures. The band simplified their song structures, but increased the complexity of their arrangements and instrumentation. “I Zimbra” added Cuban, Brazilian, and African percussion along with the signature stylings of Robert Fripp’s guitar work. Remain in Light‘s densely layered synthesizers, various types of drums, and percussion atop the guitars, bass, and trap set that had been the core of the group’s sound since their first album. Created through countless overdubs that enabled each band member to play percussion alongside their normal instruments, the album featured extended Afrofunk and worldbeat grooves that interwove “call and response” vocal lines with intricate polyrhythms.

To recreate this sound on stage, the band recruited several players from other groups. On tour Talking Heads became a sort of New Wave supergroup with King Crimson’s Adrian Belew on guitar, Ashford and Simpson’s Steve Scales on percussion, and Funkadelic’s Bernie Worrell on keyboards. The expansion of Byrne’s musical vision was nothing short of stunning. Using improvised jams and communal music-making as a point of departure, Remain in Light went well beyond the faux gospel and art school irony of “Take Me to the River.” By mixing preachers’ rants with the wordplay of Bronx rappers, Byrne discovered his inner Fela Kuti.

Talking Heads start making cents (on sync licenses)

1983 would prove to be a watershed year for Talking Heads. The band released Speaking in Tongues, which spawned their first top ten hit, “Burning Down the House.” The record also represented a kind of apotheosis. It was less musically adventurous than Remain in Light. But it seamlessly blended the band’s early New Wave sound with its later Afrofunk influences. Instead of grooving on one chord, most songs on Speaking in Tongues contained more conventional harmonic changes. And instead of building songs out of shorter “loops,” the new record featured much more traditional song structures with clear demarcations of verses, choruses, and bridges.

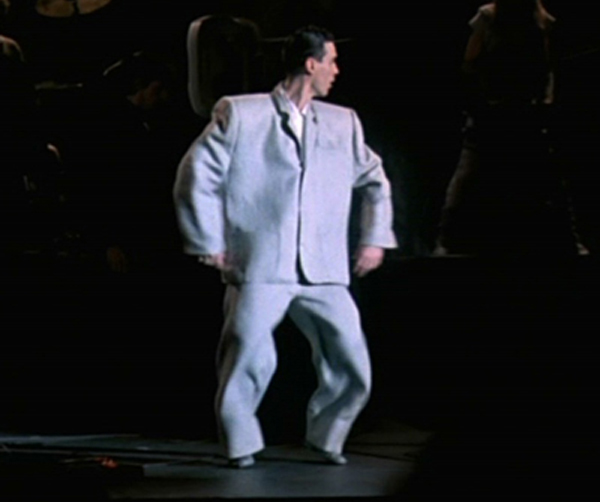

The album also served as the centerpiece of Jonathan Demme’s concert film, Stop Making Sense, which was filmed over four separate dates in December of 1983 at the Pantages Theater in Los Angeles. The set list more or less traced the history of Talking Heads, beginning with David Byrne performing “Psycho Killer” on an acoustic guitar accompanied by a rhythm track played back by a boombox. It closed with a performance of “Crosseyed and Painless” that featured the full tour ensemble, including Scales, Worrell, guitarist Alex Weir, and two female backup singers. In between, Byrne bounced around the stage in his big white suit, turning the concert stage into a space for performance art. As before, Byrne seemed to self-consciously reject the usual rock star poses. Instead, he shook, squirmed, and jerked like a giant white Gumby on a hot tin roof. Stop Making Sense went on to become a modest commercial success and won the National Society Film Critics award for Best Documentary of 1984.

Between 1983 and 1986, Talking Heads also saw their profile raised by the use of songs in other popular films. The group had already been featured in a motley group of titles prior to Speaking in Tongues. “Life During Wartime” was included in Alan Moyle’s Times Square (1980), a teen comedy about two aspiring punk singers in New York. But so was almost every other hot artist of the moment, such as Joe Jackson, Gary Numan, the Cars, the Cure, and the Pretenders. The Heads had also performed “Psycho Killer” in Bette Gordon’s short film, Empty Suitcases.

The industry surge in soundtrack sales in the early to mid-eighties, though, gave Talking Heads access to more high-profile studio projects. “Burning Down the House” made an appearance in the rowdy fratboy comedy, Revenge of the Nerds. And the use of “Once in a Lifetime” over the opening credits of Paul Mazursky’s Down and Out in Beverly Hills (1986) fueled the song’s return to Billboard’s Hot 100 more than five years after it was released.

A much more interesting case of music licensing occurred with the push given to “Swamp,” the opening track on side two of Speaking in Tongues. Robbie Robertson of The Band selected the song for inclusion on the soundtrack of King of Comedy (1982) well before the album was released. It then appeared again just months later in the Tom Cruise teen comedy, Risky Business. The reuse of “Swamp” so soon after Scorsese’s film might well be a case of serendipity. Paul Brickman, Risky Business’ screenwriter and director, likely glommed onto it when he heard David Byrne intone the phrase “risky business” in the song’s last verse.

“Swamp,” though, anticipated yet another change of direction in the band’s music. Unlike the worldbeat influences that were still evident in the rest of Speaking in Tongues, the track returned Talking Heads to American terra firma, more specifically the musical idioms of the Mississippi delta. A slow, blues shuffle tune with strong triplet rhythms, “Swamp” was truly unlike anything else the group had done before. Floating on Bernie Worrell’s funky synth textures, it sounded like a Parliament cover of an old Muddy Waters song. The fact that Byrne’s vocals deliberately mimicked John Lee Hooker just added to its overall strangeness.

But just as “I Zimbra” presaged Talking Heads’ foray into Afrofunk, “Swamp” foreshadowed the band’s turn toward American roots music. Their follow-up album, Little Creatures, showed the band branching out even further with the rollicking zydeco of “Road to Nowhere” and the soporific country weeper, “Creatures of Love.” All of this would eventually lead Byrne and co. to True Stories and to a state with a musical canvas almost as large as its geography: Texas.

More songs about voodoo and dreams

In the special features on Criterion’s excellent edition of True Stories, David Byrne acknowledges that his conception of the film was partly inspired by his admiration for Robert Altman’s Nashville. The resemblances between the two films aren’t hard to discern. Both films feature multiple protagonists and use setting to unify the film’s different plotlines. Both films include the perspectives of one or more outsiders — The Narrator in True Stories, Opal and John Triplette in Nashville — who serve as the viewer’s guide to the community each explores. Both films also involve preparations for a local celebration – the talent show, the political rally – to motivate musical numbers by a variety of performers, much in the manner of a revue or jukebox musical.

Texas is home to a distinctive mix of different kinds of “roots” music. Byrne was keen to capture that breadth. In an essay on the music written for True Stories, Byrne says, “I realized there was a lot to represent – rock, country, Tex-Mex, polkas, Latin, lounge jazz, disco, and some made-up genres, like an accordion marching band.” Trips to scout locations for the film brought Byrne into contact with a number of clubs and musicians. He then offered some local musicians an opportunity to contribute to the score. None of the groups represented is particularly well known outside of True Stories. Indeed, neither the Panhandle Mystery Band nor Brave Combo achieved even the modest fame accorded to Texas singers like Delbert McClinton or Freddy Fender. Still these local musicians definitely added to the “specialness” that Virgil represents.

In his collaborations with local musicians and the songs written for various actors to sing in True Stories, Byrne found himself serving two masters. On the one hand, Byrne wanted to pursue his vision for the film and to write songs that express the feelings and perspectives of various characters. On the other hand, though, Byrne also had to make sure these numbers still worked as Talking Heads tracks. It seems likely that Warner’s willingness to support the film depended upon the ancillary revenues they hoped to earn from the soundtrack. The Heads had been signed by Sire Records, a subsidiary of Warner Music. Given the band’s previous sales, a new Talking Heads album served as a hedge against the film’s disappointing box office.

Virgil wants its MTV

The three songs Talking Heads recorded specifically for the film – “Wild, Wild Life,” “Love for Sale,” and “City of Dreams” — are perhaps the best illustration of Byrne’s need to create corporate “synergy” in the relationship between True Stories and its music ancillaries. All of them are foursquare rock and roll songs. No doubt they reassured Warner Bros. that they had commercially marketable singles that could generate radio airplay and hopefully drive traffic to movie theaters. “Wild, Wild Life” would become the second biggest hit in the band’s history, peaking at #25 and spending about five months on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart.

Notably, though, Byrne insisted these weren’t genuine Talking Heads records. Instead, they represented the band’s attempts to sound like other popular artists. Byrne described the role models for these tracks:

The closing song, “City of Dreams,” is my version of a Neil Young anthem. Its lyrics echo the history lesson at the beginning of the film. “Love for Sale” was our version of a Stooges song, and “Wild, Wild Life” was my attempt at writing a song like something one might hear on MTV at the time.

Byrne doesn’t give us a lot to go on here, but we can discern at least some similarities between the songs and the artists he cites. On “City of Dreams,” Byrne’s voice doesn’t have the fragility that Young’s “high lonesome” tenor conveys. But the lyrics evoke the kind of imagery found in some of Young’s most famous songs, especially those that relate the experience of Native Americans. Indeed, Byrne’s verse about the Spanish search for gold wouldn’t seem out of place in “Cortez the Killer,” the standout track on Young’s 1975 album Zuma.

With its crunchy guitar riff and drum break, “Love for Sale” at least nominally sounds like it could be a track from the Stooges’ Fun House. It certainly channels some of the proto-punk energy that made the Stooges, especially lead singer Iggy Pop, a revered cult band in the early seventies. Yet Talking Heads’ performance shows their customary clockwork precision, and the record generally lacks the kind of wild abandon that one associates with the Stooges’ best tracks. Eric Thorngren’s audio engineering of “Love for Sale” also adds a layer of studio polish that an album like Raw Power most pointedly refuses. In an odd way, the recording gives us some insight into how the Heads might have sounded had they been a punk band in their CBGB days.

Perhaps the bigger irony here is that the song functions as an interpolated music video watched by the Lazy Woman during a bout of channel surfing. It shows Byrne’s usual eye for inventiveness within the form: silhouettes, primary colors, and a surrealist arc in which each band member is molded into a chocolate figurine wrapped in foil. Yet here is where the similarity between the Heads and Stooges ends. Iggy Pop may have been known for pouring oil or honey on his body during Stooges concerts. But in 1986, the Stooges were about the last band one would expect to see on MTV.

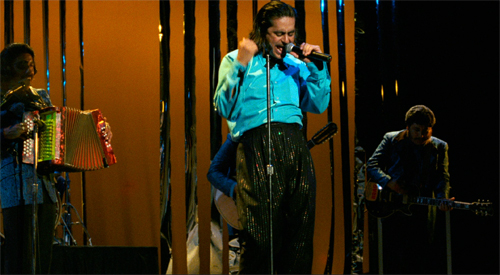

“Wild, Wild Life” is motivated in a similar way. Heard in a Virgil dance club, much of the film’s cast lip syncs to it against a bank of video monitors. Like “Love for Sale,” this footage became the basis of a very successful music video promoting the film. In a bit of an in-joke, guitarist Jerry Harrison twice appears onscreen dressed as an iconic rival artist: first as Billy Idol, then as Prince. (Note that Tina Weymouth also appears with Harrison as a fetching Apollonia.) Still, the lack of specificity in Byrne’s description suggests that it was Talking Heads’ attempt to make a rather generic pop record. In contrast to the film’s celebration of “specialness,” Byrne’s explanation of the song’s purpose functions as a backhanded critique of MTV’s role as tastemaker. In trying to sound like everyone, “Wild, Wild Life” fit quite snugly into the music network’s video rotation.

The sage in bloom is like perfume

The film’s remaining songs are performed by characters. They illustrate Byrne’s desire to capture the breadth of Texas’ musical culture in a variety of idioms. Other bits of music are also interspersed between these numbers. There are snatches of nondiegetic score based on Byrne’s two “dream” songs (“City of Dreams” and “Dream Operator”). Meredith Monk contributed a brief minimalist theme that is featured in the film’s opening and closing scenes. It is perhaps the clearest reminder of Byrne’s outsider status, enveloping the film within the sounds of the downtown Manhattan arts scene. It also includes Carl Finch’s “Buster’s Theme” as music played during True Stories’ infamous accordion parade.

At least two songs evoke the swamp pop of Eastern Texas, which shares much of its sound with the music of New Orleans. “Hey Now” features the simple tonic/dominant changes and “call and response” strophic patterns heard in second line parades during Mardi Gras. Sung by children, it sounds like a modernized version of the Dixie Cups classic, “Iko Iko.”

“Papa Legba,” on the other hand, carries a more pronounced “island vibe,” conjuring the Cuban and Jamaican styles that were such an important influence on Dave Bartholomew, Fats Domino, and Lloyd Price. Performed by the great Pops Staples, the style is apt since the song is ostensibly an appeal to a central figure in Haitian folklore. (Legba is a demigod in voodoo culture who facilitates communication between living beings and the souls of the dead.) Staples expressed concern about this scene. The actions of his character, Mr. Tucker, ran squarely against the actor’s Christian faith. Yet, despite Staples’ literal embodiment of the “magic negro” trope, Tucker’s actions here come across as rather benign. He acts on Louis’ behalf, and both characters seem so decent and honest that their resort to sorcery seems quite harmless.

In other films and television shows, such as Crossroads or American Horror Story, Legba is often trotted out as a stand-in for Satan himself. In True Stories, though, Tucker’s Legba number is a slightly less hokey version of Leiber and Stoller’s “Love Potion # 9.”

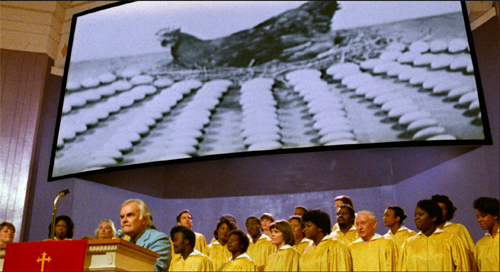

“Puzzling Evidence” is a straightforward gospel number, delivered from the pulpit by John Ingle as The Preacher. As an enumeration of possible conspiracies, the scene might seem today as QAnon avant la lettre. But sober reflection suggests the song is further evidence that Richard Hofstadter’s “paranoid style” of American politics has a long and rich history.