Archive for the 'Directors: Welles' Category

Venice 2018: Welles and THE OTHER SIDE OF THE WIND

DB here:

The Venice Biennale film festival unveiled to a panting cinephile public the long-rumored Welles film The Other Side of the Wind, now reconstructed thirty-three years after its director’s death. This is only one of many possible versions. Welles reportedly edited two scenes himself, including an erotic encounter in a rainstorm-shaken car, but the rest has been assembled from about a hundred hours of footage. (But see the PS in the codicil below.) Welles left many notes but no definitive script, so editor Bob Murawski, with guidance from many Welles experts, has carved out something that must stand as a best approximation what its initiator had in mind.

Approximation is also the word for my response. I need to see the film more than once in order to get to grips with it. Not that it’s a dense, complex work; I don’t think it is. It’s just that I need to shake off a sense of déja vu.

Or rather, déja lu. Having read about the film for years, I found almost nothing onscreen that I hadn’t been primed for by press coverage, by Joe McBride’s What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?, and by Josh Karp’s Orson Welles’s Last Movie. I found myself groping for a triple vision: How to imagine seeing the film fresh, without knowing its plot, characterization, and most pungent lines already? And then, how would it have looked and felt in the context of 1970s filmmaking? Finally, of course, how to consider it now, in the context of modern cinema?

Sorry, but I’m far from having an answer to any of these questions. Herewith, just some things that the film made me think about.

All together now

One persistent narrative premise, on stage and screen, might be called the climactic gathering. The plot is concentrated in a limited space and a short span of time–a day, or better, a night. The occasion is a meeting or party that brings together friends, acquaintances, associates, or kinfolk. As time passes, quarrels break out, old wounds rip open, and eventually family secrets and past transgressions are exposed. Examples of this dramaturgy are O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night, Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, and films like Twelve Angry Men, A Wedding, Margin Call, and The Celebration.

The advantages of this format are many. The limits of time and place realistically assemble characters for intense confrontations, and those can be interwoven quickly to maintain audience interest. Actors like such a setup because the deterioration of civility that usually comes with the situation allows them to show a range of emotions that will culminate in bravura breakdowns. But the disadvantage is a certain obviousness: the secrets or suppressed feelings or traumatic memories will have to be stated rather nakedly. Subtlety may not be easy to achieve.

The Other Side of the Wind situates the climactic-gathering format in Movieland. After filming a stretch of director Jake Hannaford’s work in progress, called The Other Side of the Wind, cast and crew and hangers-on drive out to his house. The party aims to celebrate his seventieth birthday and, perhaps, enable him to drum up finishing money. A night of uninhibited drinking and verbal sniping is broken by screenings of parts of Hannaford’s film. At the climax, Hannaford drives away to a fatal car crash.

Welles, being Welles, puts new twists on the template. In Reinventing Hollywood, my book on 1940s cinema, I argued that he, like Hitchcock, was under unusual pressure to keep coming up with new ideas. Both filmmakers were so widely copied that they had to outrun their imitators. As Welles told Gary Graver, his loyal DP in his late years:

Somebody always has to be ahead of everybody else. I have to be steps ahead of everybody. I have to be more inventive and do things that nobody has done.

His urge to innovate helped fuel the fifteen years he devoted to shooting and cutting The Other Side of the Wind. This jaundiced satire of Hollywood displays some striking formal strategies–some original for the period, some familiar from his other work, but all an effort to galvanize audiences as he had throughout his career.

A man’s man

This Hollywood party is rendered in blunt satire and in-jokes. It’s haunted by Mr. Pister (Joseph McBride), a geeky film critic asking questions about phallic symbols and the camera’s quest for reality. A more acerbic critic, Juliet Riche (Susan Strasberg), is a stand-in for Pauline Kael, who wrote a notorious broadside against Welles. Peter Bogdanovich plays the implausibly named Brooks Otterlake, a younger, successful director who is both a disciple of Hannaford’s (he calls Jake “Skipper” and “Daddy”) and a rival to him. Familiar faces from the studio years–Paul Stewart, Dan Tobin, Mercedes McCambridge–as well as younger figures like Paul Mazursky and Henry Jaglom make appearances. This climactic gathering brings together New Hollywood and Old, even Elderly, Hollywood.

By casting John Huston as the lanky, roguish Hannaford, Welles adds an evocative layer to the citations. Welles had acted in several Huston films; now Huston is in front of the camera, his face resembling, in Dwight Macdonald’s phrase, a relief map of the Dakota badlands. He was nine years older than Welles, but he made his directorial debut with The Maltese Falcon in the same year as Citizen Kane. Significantly, his star rose after Welles’s fell. By the time Huston won acclaim with The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) and The Asphalt Jungle (1950), Welles was unemployable as a Hollywood director and scrounging work in Europe.

Karp reports that Welles told Huston that his role was a critique of all egotistical directors—“It’s about us, John”—and Welles considered playing the part himself. But Welles wouldn’t have fit the more specific target the film seems to home in on, the swashbuckling filmmakers like Rex Ingram, Howard Hawks, and William Wellman. Huston embodied the hunting-shooting-fishing-punching persona to the full. In this context, Riche’s suggestion that Jake Hannaford harbors gay desires for his male stars takes on a special bite.

Was Welles taking jabs at Huston’s image? I have to wonder. While Welles was fleeing hotel bills and performing offhand magic on talk shows, Huston maintained an active studio career; he took leave from Other Side to make one of his biggest successes, The Man Who Would Be King (1975). At the least, Hannaford’s climactic gathering can be seen as another sort of convergence, bearing the traces of the contrasting 1970s fates of two prodigious directors who came up together.

Cameras and cutting

The notion of tracing a day and night in the lives of several movie people was sharpened by Welles’ decision to shoot The Other Side of the Wind in a reflexive cinéma-vérité style. Today we accept a grab-and-go documentary look as a legitimate approach to fictional presentation, but in Other Side the technique is given a realistic pretext. Anticipating the premise of The Office and other TV shows, Welles’ innovation was to provide specific sources for everything we see and hear: an array of cameras and tape recorders. Here even intimate exchanges are captured by at least one camera.

In a way, this idea reverts to Welles’ lifelong interest in the how of storytelling. His radio plays, under the rubric “First Person Singular,” often framed their stories within a narrator’s commentary. This Conradian inclination toward embedded tales, brilliantly managed in his Mercury radio adaptation of Dracula, emerged as well in Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons. Other Side’s mosaic of scenic bits harks back to the montage of sources (dance music, government announcement, network news bulletins, voice-over diary entries) that fill the War of the Worlds broadcast (1938).

Like Kane, Other Side opens with the main action already completed. An image of a crumpled car is accompanied by Bogdanovich/Otterlake’s voice explaining that Hannaford died in a crash after his party. (Apparently, Welles would himself have supplied this narration.) That explanation frames the footage that has been assembled documenting Jake’s last day on earth. Embedded in all that material, mostly black and white and in 4:3 format, are scenes from Hannaford’s last movie, in ripe color and widescreen and full of arty compositions and one frequently naked lady. Although they’re motivated as being projected to various audiences in the film, at the end some of the imagery seems to float free, being intercut with the documentary material.

The result is an extended experiment, more radical than even Rear Window, in the Kuleshov effect. Cuts between cameras and partyers, or people in conversation, are linked solely by our understanding of the context; there are few establishing shots. The cuts link shots that were made months or years apart, in any of the many houses Welles commandeered as his sets.

Admittedly, he had been up to such tricks before. The instructive documentary They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead (also screened at Venice) shows an example from Othello of shot/reverse shot cutting based on vast gaps in production time. But Other Side‘s shifting cast and locales have created Welles’s most disjunctive, fragmentary film. I counted about 2300 shots in 117 minutes, an average of three seconds per shot. He applied the same approach in F for Fake (1973), but that feels less scrappy because Welles’s buoyant voice-over glues everything together.

On this blog we try to practice a criticism of enthusiasm, writing mostly about films we admire and avoiding panning the films we don’t. Still, as a lifelong Welles fan, I can’t duck an initial appraisal.

I confess being disappointed by the film. I’m not ready to call it The Other Side of the Windbag, but I’m not sure it escapes the on-the-nose quality we often find in the climactic-gathering format. Here people must get both nasty and horribly transparent about baring their feelings. Moreover, the film-within-the-film, shot in glowing color and abstract cityscapes, is supposed to be a parody of Antonioni (Zabriskie Point in particular), but (a) most of it is more like a slick-magazine version of a trance film from the 40s like Meshes of the Afternoon; and (b) it’s inconceivable that even in the Love Era Hannaford’s project could receive commercial funding or release. It seems to me a bad idea of what a bad movie looks like.

Still, I’m trying to keep an open mind. Watching it more analytically and reading what critics write about it may open it up for me in ways I can’t now predict. For the moment, it’s satisfying enough to thank Netflix for enabling us to see in however hypothetical a form, what forty years’ fuss has been about.

As ever, thanks to Paolo Baratta, Alberto Barbera, Peter Cowie, Michela Lazzarin, and all their colleagues for their warm welcome of us to this year’s Biennale. I’ve especially enjoyed discussing The Other Side of the Wind with Peter, whose The Cinema of Orson Welles shaped my view of the director’s career way back in 1965.

My quotation from Gary Graver comes from Joe McBride’s What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?, p. 225.

For more on the Kuleshov effect, see “What happens between shots happens between your ears” and “They’re looking for us.”

Feel free to visit our Instagram page for an ever-expanding set of snapshots of the Venice festival.

P.S. 5 September 2018: Standard accounts suggest that Welles completed editing only two sequences. Alert reader Evan Davis points out that editor Bob Murawski says that Welles edited about 30% of the finished film. Thanks to Evan for this.

I apologize for the typos and whiffs in this entry; we’ve had unreliable access to the Net lately, and not all revisions took.

P.S. 8 September 2018: Ardent Wellesian Jim Naremore has created his own website, and it’s must reading for every cinephile. Right off the bat he gives us a thoughtful piece, “Orson Welles, Citizen of the World,” available in English only online. Watch for Jim’s essay on The Other Side of the Wind, slated to be published in Cineaste.

John Huston, Orson Welles, and Peter Bogdanovich on the set of The Other Side of the Wind.

Welles at 101, KANE at 75 or thereabouts

DB here:

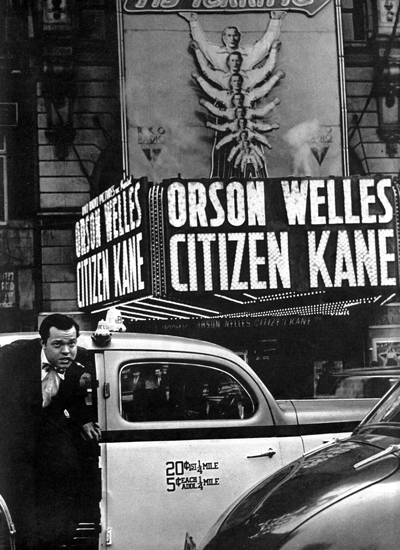

Kristin and I are one-third through our New York stay, and blogging has suffered. There have been talks to give, old friends to visit, new friends to meet, and movies and exhibitions to see. And there’ll be more activities of these sorts to come. But I can’t let 6 May pass without some acknowledgment of Orson Welles.

That’s partly because I just finished a draft of the Welles section of my 40s Hollywood manuscript. (Yeah, that beast was another distraction from blogging. All 158,000 rough-hewn words of it are now dispatched to some unwary readers.) So Welles was on my mind already when the anniversary of the “official” Citizen Kane release came up on 1 May.

Actually, by the time Kane had that roadshow release, it had been widely seen by the Hollywood community. In the face of the Hearst press’s attacks, RKO head George Schaefer held invitational screenings in early 1941 to build up support for the film. Variety estimated that by late March 1,200 producers, directors, writers, actors, and agents had seen the picture. The number was so big that RKO dispensed with a splashy Hollywood opening. (The article title is pure Varietyese: “So Many Cuffo Gloms at ‘Kane’ It Kayoes Idea of a $5.50 Preem,” Variety, 2 April 1941, 2, 20.) As a result, I think, Kane‘s influence began to be registered some months before its New York premiere, as the look of The Maltese Falcon (shot June and July of 1941) might suggest.

What I offer today, on the Boy Wonder’s birthday, is a consideration of that movie from an unusual angle looking not just at its originality but also at its shrewd consolidation of a variety of techniques.

Wellesapoppin’

We’re so used to considering Kane powerfully original that it’s worth remembering that it synthesizes a lot of traditions. I’m not thinking of Pauline Kael’s claim that it’s a culmination of the 1930s newspaper genre; as so often, she fails to persuade me. I’m thinking instead of the look and sound of the movie, as well as its storytelling strategies.

Depth staging and deep-focus cinematography are two techniques not always kept distinct in critical discussion. 1930s Jean Renoir films have plenty of depth staging but usually not so much deep focus. Citizen Kane won attention partly because it has plenty of both, and in exaggerated form. The figures often stretch very far back, someone or something is often rather close to the camera, and often all of them are sharply focused.

Without taking anything away from the boldness of Welles and cinematographer Gregg Toland, we should recognize that they reworked visual patterns—what I’ll call schemas—that were already circulating in filmmaking. Framings with big foregrounds, distant planes, and low angles weren’t unknown in silent films (Opium, 1919; Greed, 1925; A Woman of Affairs, 1928) and some early talkies (No Other Woman, 1933).

There was a sort of fad for such deep staging, especially with wide-angle lenses, during the late 1930s, though all the planes weren’t usually kept in focus. Some directors, such as John Ford (here and here) and William Wyler, favored deep images, while art director William Cameron Menzies (see here and here) made them part of his artistic signature. Below: Ford’s Long Voyage Home (1940), shot by Toland, and Menzies’ Our Town (1940), directed by Sam Wood.

It’s now acknowledged that many of Kane’s deepest shots weren’t actually made in the camera, but by means of special effects, particularly matte shots. Interestingly, this too wasn’t utterly original; compare the composite shot from Kane with the one from Mr. Moto’s Gamble (1935), which has an even more aggressive foreground.

Welles and Toland called attention to these techniques by a radical gesture: many of these deep shots are long takes from a fixed camera position. Most filmmakers who used these depth schemas inserted them into passages of orthodox scene dissection. The depth shots might establish a locale, or they might be inserted into a series of analytical cuts, or they might be part of a shot/ reverse shot pattern. But in Kane you’re forced to notice the Baroque plunge of space because the lengthy take rubs your nose in the flashy composition.

It’s clear that Kane crystallized a certain look that was picked up by John Huston, Anthony Mann with or without his DP John Alton, and many other directors. The Welles/Toland version of depth consolidated a visual style that dominated American black-and-white filmmaking into the 1960s. Typically, though, filmmakers didn’t rely on the fixed long take as much as Welles did in Kane. Even Welles gave up that option in favor of dynamic editing of deep-focus shots, as in The Lady from Shanghai (1948) and Othello (1952/1955).

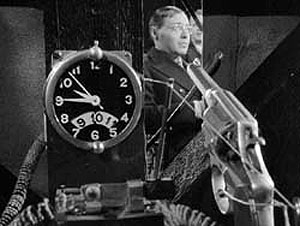

Not everything is long takes and depth. The pictorial variety of the film is, I think, unprecedented. The “News on the March” sequence becomes a virtuoso exercise in all the techniques that the rest of the film won’t be using. For perhaps the first time in history, Welles artificially distresses his staged scenes to make them match archival footage. He adds scratches and light flares.

This newsreel is so film-savvy that it can build in jump cuts and fast-motion as guarantors of fake authenticity. One passage mimics two-camera reportage, allowing us to imagine paparazzi crouched and perched at a fence to grab clandestine shots of an elderly Kane.

Here the schemas that are borrowed come from archival and documentary traditions, repurposed to add realism to this fictional biography. Welles, as we’ve seen in the Great Ambersons Poster Mystery (here and here and here), was a smart-alec cinephile: your disobedient servant.

What about sound? Back in 1994, Rick Altman wrote a pioneering article showing how Kane manipulates our sense of auditory space, and he connected that to Welles’ use of radio conventions. Contrary to what we might expect, Welles’s soundtrack doesn’t create much “deep-focus sound”; Altman shows that our impression of that is created chiefly by an overall reverberation rather than precise placement of sonic events. Altman also stresses Welles’ use of sudden, loud sound events to start or end a scene–another radio technique.

Today we’re lucky to have a great many of Welles’ radio programs available on the Web, and we can appreciate how his rich soundscapes mingle noises, dialogue, and voice-over narration. These shows remain very gripping. Listening to Kane in the same spirit, I’ve been impressed with how talky it is, how sounds crash in on you, and how even bursts of silence can be startling. Welles told one biographer that he aimed to create spiky transitions, both visual and sonic, because he thought most films of the period were dull.

He had already made his stage reputation on “shock effects,” those stunning high points in particular productions: the death of Macbeth in the Harlem production (1936), an actor’s headfirst tumble into the orchestra pit in Horse Eats Hat (1936), the mob’s murder of Cinna the Poet in Caesar (1937), the guillotine scenes in Danton’s Death (1938), and police agents firing from the audience in Native Son (1941). He became known as a director of thrilling moments, ever willing to sacrifice steady buildup to anything that would astonish. Forties theatre critics had a name for it: “Wellesapoppin’.” That quality dominates Kane’s images and sounds.

Remembering, recounting, replays

Otto Hullet, Barbara O’Neill, and Orson Welles in Sidney Kingsley’s Ten Million Ghosts (1936).

Just as Kane amplifies visual and auditory schemas already in circulation, the film does somewhat the same thing to narrative strategies. The key innovation here involves flashbacks and point of view.

Flashbacks were rare in the 1930s, but the early 1940s began a flashback craze that continued throughout the decade. Between August 1940 and December 1941, every top studio tried out flashbacks in a major release: The Great McGinty (Paramount), Kitty Foyle (RKO), I Wake Up Screaming (Fox), H. M. Pulham, Esq. (MGM), and Strawberry Blonde (Warners). A reviewer claimed that the “retrospective viewpoint” technique in A Woman’s Face, released the same month as Kane, “had of late become commonplace.” By September 1941 the Los Angeles Times critic considered the technique overused.

Even though the trend was already launched, Kane probably strengthened Hollywood’s inclination toward time-shifting. Again, it crystallizes in an influential way possibilities opened up in film, radio, theatre, and other media.

Kane’s central premise—a dead man recalled by one or more survivors—had been rehearsed in earlier films. The Power and the Glory (1933), scripted by Preston Sturges, was probably the most noted experiment in that vein. (For more, see this long-ago entry.) Another example was The Life of Vergie Winters (1934), which begins with a funeral procession and flashes back to the start of a backstreet love affair. (See this entry.) The Escape (1939) centers on a doctor who tells a crime reporter about a recently deceased neighborhood gangster, and flashbacks enact his tale.

These earlier examples stick to a single teller, while Kane offers reports on its dead man from five characters. Here again, however, there are precedents. In fiction and drama, trials have long served as motivation for flashbacks from multiple viewpoints. A major example, perhaps the first, is Robert Browning’s verse novel The Ring and the Book (1868-1869). Multiple tellers recounting events in flashback were staples of Hollywood courtroom dramas too. Beyond the trial-based format, Welles’ radio programs had welcomed multiple storytellers, sometimes embedding them within one another’s tales, sometimes letting them banter with each other.

Kane assembles views on a person rather than evidence of a crime, but even this is not completely unknown. Some playwrights had tried out what Kane screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz had called the “prismatic” approach to an absent central character. Sophie Treadwell’s play Eye of the Beholder (1919) portrays an offstage woman as seen through the eyes of her former husband, her lover, her lover’s mother, and her own mother. The play These Few Ashes (1928) presents the life of a (supposedly) dead roué through the recollections of three women, each of whom sees him quite differently.

Then there’s reporter Thompson’s investigation. The Power and the Glory’s exhumation of the tycoon’s past is presented simply as his old friend’s recounting; it’s not the investigation of a mystery. Kane innovated in the biographical film genre by creating curiosity based on the dying man’s last word, “Rosebud.” That device shifts us to the terrain of the detective story. The dying message had become a mystery-tale convention from Conan Doyle onward, and Welles and Mankiewicz shrewdly recruited it for their purposes (although it’s not clear exactly who hears Kane say the crucial word).

In blending conventions of several genres, Kane motivates the flashbacks on diverse grounds. The film’s detective-story side is anticipated by The Phantom of Crestwood and Affairs of a Gentleman (1934); in both, flashbacks represent the suspects’ answers under questioning. Like The Escape, Kane uses a reporter’s search for a story to justify its flashbacks, and the reporter isn’t the protagonist (as he’d be in a typical newsman movie). And being something of a biopic, Welles’s film can trace the rise of a great man from the vantage point of old age, as in Edison, the Man (1940). By the way, that’s another film of the era using a journalist’s questioning to launch flashbacks to a person’s life.

Another wrinkle: Kane’s flashback organization skips around in the past. Episodes of Kane’s life are not presented in 1-2-3 order. Plays set in courtrooms, such as Elmer Rice’s On Trial (1914), had rendered flashbacks out of sequential order, and so had radio dramas. Welles’ 1938 radio adaptation of Dracula shuffles episodes in the manner of the source novel. Non-chronological strings of flashbacks weren’t common in film, but The Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932) and The Power and the Glory used them significantly.

Even rarer is the replayed flashback, the scene from earlier in the film that is repeated, usually to reveal something we hadn’t caught on the first pass. Kane has occasion to present a brief replay from differing character viewpoints. Susan’s opera premiere is first treated curtly, as the object of the stagehands’ scorn. Later, in her flashback, the same scene registers the central characters’ reactions: a severe Kane, a bored Leland, the harried singing master, and above all the panicked Susan.

Replay flashbacks were rare in the 1930s, but The Witness Chair (1936) provides one example. After Kane, they would become more common, with Mildred Pierce (1945) offering one of the period’s most complex examples. (I discuss it here and here, with a video here.)

Even the coup de théâtre of following Kane’s death with a newsreel can be seen as revising a schema. “News on the March” isn’t exactly a flashback, but it provides exposition by shuttling among time periods in a manner characteristic of the film to come. Projected headlines and documentary footage, faked or actual, had found their way into 1930s theatre practice, notably in the WPA Living Newspaper productions. Many 1930s films opened with montage sequences using headlines, stock footage, and voice-overs like those in newsreels; The Roaring Twenties (1939) is a bold example. Gabriel over the White House (1933), with its mix of library footage and staged shots, anticipates Kane somewhat, as does Welles’ script for an uncompleted 1939 RKO project, The Smiler with a Knife, which includes a newsreel surveying the career of the fascist villain.

Another, less proximate source may be Sidney Kingsley’s 1936 Broadway play Ten Million Ghosts. This strident antiwar tract lasted only eleven performances and was never published; I took a look at a copy of the script last week. In the original production Welles played the naïve young poet André in love with the daughter of a munitions magnate during World War I.

Ten Million Ghosts includes a scene in which arms makers spend an evening watching a battlefront newsreel in their parlor. Kingsley’s purpose is to show the capitalists as utterly indifferent to the slaughter that the camera records.

They watch in silence for a while. Then there are technical comments on the explosives, shells, etc. as we see them hurl geysers of earth and men into the sky.

Was this embedded newsreel an early source for News on the March? Scholars have wondered. And there’s more.

As the film unwinds, André, who has learned that his family has been killed in the war, cries out in protest. Madeleine is torn between him and her father. To win her over her father angrily defends his double-dealing between both sides in the war. It’s all just business, he insists. Then we get this piece of action:

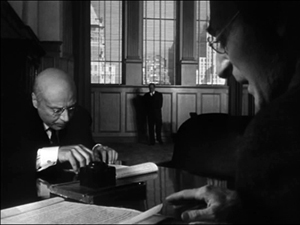

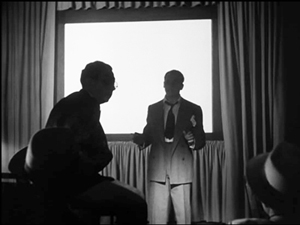

De Kruif rises, intercepting the beam of the projecting machine, his face highly lighted, his shadow, black and ominously magnified, thrown on the screen superimposed over the pictures of men writhing in bloody destruction.

Was De Kruif’s moment in the play a visual idea that inspired Kane’s projection-room scene? If so, Welles and Toland revised the premise of the play. Instead of the rather obvious looming shadow cast on the screen, the story editor is a silhouette against the blank white rectangle, and then, in a reversed setup, he becomes another silhouette, this time splitting the projector beam.

Welles told Peter Bogdanovich that he never saw the projection scene in Kingsley’s play because he was always back in his dressing room at that point. But as Pat McGilligan points out in his new biography Young Orson, Welles could hardly have been unaware of the film-within-the-play; many critics commented on it. More decisively, in the playscript, André is clearly onstage during the screening. He cries out against the carnage: “Look, look! Those are only pictures. . . Out there it’s real. . .” Peter Noble’s 1956 biography The Fabulous Orson Welles quotes Welles as declaring that this scene left a strong impression on him.

It’s not enough just to mention some sources. If you practice historically-slanted criticism, you need to ask not only “Where from?” but “What for?” In other words, you have to ask how elements that a filmmaker inherits get repurposed for the particular movie.

So, for instance, Kane’s depth-designed images held in long takes allow a more “theatrical” shift of attention within a visual field (driven largely by following who’s speaking). They also create contrasts of scale and visual weight. And each scene will have its specific demands that the depth technique fulfills. A depth shot can present cause and effect in the same frame, and it can build suspense by letting us await Kane’s interference in a foreground situation.

Similarly, Kane’s narrative strategies, synthesizing so many earlier efforts, blend to create a mystery that isn’t about whodunit but rather “why’d he do it?”

I’m not exactly saying that everything is a mashup. But that slogan does capture the fact that in art nothing comes from nothing. Kane blends several options that had been circulating in popular culture and high culture for some years. Like others before and since, Welles revised schemas tried out earlier; he combined some, exaggerated some, and infused many of them with new force. Because of his film’s prestige, he gave thrusting imagery, bold sonic manipulations, and complicated time shifts a new prominence in Hollywood filmmaking. The Forties had begun.

There are a several essential Welles sources. Apart from the many fine critical studies (see especially Jim Naremore’s Magic World of Orson Welles and Joe McBride’s What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?), the biographical surveys I habitually turn to are Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, This Is Orson Welles (Da Capo rev. ed., 1998), with a painstaking chronology by Jonathan Rosenbaum; the three-volume Simon Callow biography; Bret Wood’s Orson Welles: A Bio-Bibliography (Greenwood, 1990); Barbara Leaming’s Orson Welles: A Biography (Viking, 1985; my reference to shock effects is from p. 338); Frank Brady’s Citizen Welles (Scribners, 1990); and most recently Pat McGilligan, Young Orson: The Years of Luck and Genius on the Path to Citizen Kane (Harper, 2015). Pat’s discussion of Ten Million Ghosts is on pp. 366-367; Welles’ misremembering of the production is on p. 78 of This Is Orson Welles. A typescript of Kingsley’s play is held in the New York Public Library, at the Lincoln Center Library for the Performing Arts.

Rick Altman’s study is “Deep-Focus Sound: Citizen Kane and the Radio Aesthetic,” Quarterly Review of Film & Video 15, 3 (1994): 1-33. If it’s available without cost online, I haven’t found it. The programs “Dracula” (1938), “The Hurricane” (1939), and “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” (1940) provide vivid examples of multiple narrators and embedded flashbacks. For a comprehensive account of Welles’ radio work, see Paul Heyer, The Medium and the Magician: Orson Welles, the Radio Years 1935-1952 (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2005). As for prismatic flashbacks, in the mid-1930s, Mankiewicz had built the plot of an unfinished play around the memories of people who had known John Dillinger. See Richard Meryman, Mank: The Wit, World, and Life of Herman Mankiewicz (New York: Morrow, 1978), 247, 258.

On Kane‘s visual style and its place in film history, see my accounts in The Classical Hollywood Cinema (1985) and On the History of Film Style (1997), as well as on this site (here and here especially). A detailed analysis of Kane‘s narrative strategies is in Chapter Three of Film Art: An Introduction, 11 ed., (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2016). The distinction between depth staging and deep cinematography is explored in Chapters Four and Five.

Local Boy Makes Very, Very Good: Welles comes home

DB here:

Nearly a hundred years ago George Orson Welles was born in Kenosha, Wisconsin. The story goes that when the UW—Madison asked him to come get an honorary degree long afterward, he refused. The reason? He claimed he was conceived in Rio de Janeiro, so he considered himself Brazilian.

About ninety years ago, little Orson went to Indianola summer camp outside Madison. (A memoir of his stay, criticizing Welles’ more lurid version, is here.) He attended fourth grade in Madison 1925-1926. At that time he was studied as a child prodigy by psychologist Dr. F. G. Mueller. A story about the little rascal, who was already staging plays, appeared in a local paper. Then he transferred to the Todd School for Boys in Woodstock, Illinois.

About ninety years ago, little Orson went to Indianola summer camp outside Madison. (A memoir of his stay, criticizing Welles’ more lurid version, is here.) He attended fourth grade in Madison 1925-1926. At that time he was studied as a child prodigy by psychologist Dr. F. G. Mueller. A story about the little rascal, who was already staging plays, appeared in a local paper. Then he transferred to the Todd School for Boys in Woodstock, Illinois.

Madison has done pretty neatly by him. Our Wisconsin State Historical Society collections include some Wellesiana: production material on Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons, and unmade projects, along with a rich trove from Agnes Moorehead, who taught school in Soldiers Grove and got a Masters at our university. For decades, Welles’ films were staples of our bustling campus film-society scene, and out of that emerged Wisconsin-born Joseph McBride. Joe produced a fine critical monograph on Welles in 1972 and has been writing about him ever since. Another supremo Wellesian, James Naremore, did his doctorate here. Douglas Gomery, one of our Film Studies alumni, wrote a foundational study of Welles’ relation to the studio system, and Michael Wilmington, who collaborated with Joe on a book on John Ford, has also written eloquently on Welles over the years.

So I had good luck coming here in 1973. As a teenager getting interested in film, I focused most avidly on Welles. I watched Kane and Ambersons on late-night TV, and as a good omen, there was a 16mm screening of Kane during my first week as a college freshman. With pals I traveled to New York to see the newly released Chimes at Midnight (twice) and wrote a review for our student newspaper. A few years after that Film Comment published my first serious piece of film criticism, an essay on Kane. That movie has been a leitmotif of my life—a centerpiece of our textbook Film Art since its publication in 1979, important in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, and still stubbornly facing me down in my current struggles with 1940s Hollywood narrative.

So it’s in the nature of things that our Cinematheque is honoring Welles in a year-long retrospective that started in January. And it’s even niftier that our current Wisconsin Film Festival has included three items celebrating this prodigious and prodigal Cheesehead.

Never too much johnson

I like quick cutting very much. I didn’t do much of it at the start. But the more I work, the more I like it.

Orson Welles

Welles shot film material to fill in exposition for the three acts of a stage production he was mounting in 1938. Too Much Johnson was a revival of a turn-of-the-century farce, and how the smart-alecky boys must have snickered at the title. The film remained uncompleted and was never shown with the play (which failed out of town). Welles edited the first part of the footage to some extent, but what remains of the rest are rushes. The footage was discovered in Pordenone, Italy in 2008 and has recently become available for screenings. You can watch it on Fandor, though we discovered that it plays best on the big screen with an audience and live music. For us, piano accompaniment was supplied by the versatile David Drazin.

Movies have long been mixed with live performance. Early films were inserted between vaudeville acts. In Japan, films enhanced and extended the action of plays. Eisenstein famously insinuated comic footage into his 1923 Moscow production of The Wise Man, and the idea caught on in Europe as well. By 1938, the New York stage had its own tradition of mixed-media, notably in the “Living Newspapers” sponsored by the Works Progress Administration. Welles had played in another politically pointed production, Sidney Kingsley’s Ten Million Ghosts (1936), which incorporated both slides and film.

The Too Much Johnson footage is a tribute to silent movies, or at least silent movies as a young theatre director in 1938 thought of them. At that time, many intellectuals admired slapstick comedy; serious silent drama was largely considered old-fashioned and “theatrical.” Movie aficianados also appreciated the silent avant-garde, especially Clair’s Entr’acte (1924), which enjoyed a place in the crystallizing Museum of Modern Art canon. Entr’acte, another movie inserted in bits during a stage show (Rélâche), was itself a reworking of American chase-and-stunt extravaganzas. I think the Too Much Johnson material bears traces of both Hollywood and Paris, especially with certain cuts that are even bolder than what we’d find in Sennett or Lloyd.

Welles scrambles several trends of silent cinema. To evoke the period of Gillette’s 1894 play, an early scene suggests filmed theatre before 1908 or so, but Welles immediately interrupts it with very brief, looming close-ups.

Elsewhere, Welles provides a flurry of Soviet-style axial cuts when the couple are interrupted in bed.

These “concertina” cuts, along with the mismatches of a twisting Joseph Cotten, create a jumpy effect reminiscent of Kuleshov’s By the Law (1925) and other films. (Though I doubt that Welles had seen that.)

There’s also a lot of Soviet-style Eccentrism in the opening footage, with Cotten scrambling over buildings and through a market in the Harold Lloyd manner. At both a pastiche and a potpourri, Too Much Johnson stands as something more than a curiosity. It’s a sketchbook, a finger-exercise in silent cinema technique, and a testament to buoyant youth from a twenty-three-year-old. It’s also evidently the first of Welles’ many unfinished films.

Noble artificiality

Chuck Workman’s Magician: The Astonishing Life and Work of Orson Welles has the good sense not to get in the way of Welles’ overwhelming presence. The documentary smoothly incorporates many interview clips with Himself and collaborators, kin, and admirers. There are also some splendid family photographs. The structure is chronological, and clips from the film are surrounded by contextualizing commentary from Welles and others. There’s a wonderful moment when Workman illustrates, with production photos, the dead silence following the Martians’ attack in Welles radio drama. The documentary even manages to throw doubt on Welles’ reminiscences by juxtaposing contradictory interview statements. I have a hunch that Jim Naremore, who was the major consultant on the project, encouraged this sort of historical frankness. Every Welles researcher knows that against his selective memory and penchant for fabulism, the documents must be checked.

Among the familiar but always compelling landmarks, Norman Lloyd makes a comment that set me thinking. “He brought, in one word, theatricality.” Welles was a sponge, blending many of the innovations in staging and conception that streamed into America from overseas, but I think he was particularly marked by what was then called “theatrical theatre.”

Among the familiar but always compelling landmarks, Norman Lloyd makes a comment that set me thinking. “He brought, in one word, theatricality.” Welles was a sponge, blending many of the innovations in staging and conception that streamed into America from overseas, but I think he was particularly marked by what was then called “theatrical theatre.”

The Europeans, notably Piscator, and the Russians, notably Meyerhold, had embraced frank artifice. They challenged all forms of realism, from the bland ignore-the-fourth-wall parlors of the well-made play, to the Naturalist notion that the play was a “slice of life” and that you could hang bleeding cuts of meat in your stage-set butcher shop. They also challenged the atmospheric Symbolism of Appia and others. Instead, theatrical theatre offered a stripped-down presentation that broke with the proscenium and hurled itself at the audience. The stage space was no longer a room or imaginary world cut off from the audience; it was of a piece with the auditorium. Performances were no longer representational, but “presentational,” in the manner of jugglers, acrobats, or…magicians.

For Americans, the idea of Theatrical Theatre was crystallized in Mordecai Gorelik’s book New Theatres for Old (1940). Gorelik traced the trend from Toller’s Masse Mensch (1921) directly to Welles’ 1937 “no-scenery” production of Julius Caesar. Other productions of that season, including The Cradle Will Rock (Welles and Houseman, using a bare stage perforce) and Our Town, with its scripted catcalls from the audience, were turning the blank stage into a space continuous the auditorium—not an imaginary locale but an area for acting and interacting.

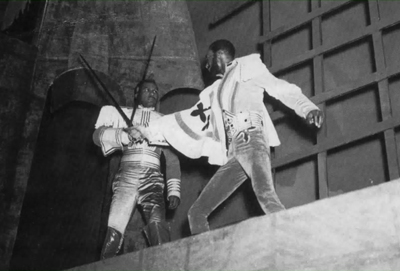

Gorelik quotes Gordon Craig: “Do not forget that there is such a thing as noble artificiality.” Not a bad summation of Welles’ productions, including the Harlem Macbeth (above) and the War of the Worlds broadcast, as well as the films. Theatrical theatre is confrontational, sometimes angrily and sometimes, as in Welles’ penchant for reviving vaudeville, good-naturedly. Even Gorelik couldn’t go along with Mercury’s 1937 Faustus, which he deprecated as a “sleight-of-hand performance.” But I think it’s plausible to take Welles as in the tradition Lloyd alludes to. Expecting realism blocks some people from appreciating the brazen stylization, the pranksterish poke in the eye we get from many of the movies.

Hearts of age

Over the last thirty years or so, I remembered Chimes at Midnight as a more cohesive movie than the admirably choppy Othello. Seeing Chimes again yesterday, I realized that they were mates. There was the same ransom-note assemblage of scenes, the abrupt cutaways covering changes in character position, the use of long shots showing characters not speaking the lines we hear them say. You hear a line and may find that nobody has opened his mouth. An empty tavern becomes suddenly full after we’ve hung around one area of it. The great battle scene starts out making sense spatially but then dissolves into chaos, as men grind and hammer one another, and the dust at their feet turns to bloody mud.

So what? One of the lessons Welles seems to have learned from Eisenstein is that continuity is overrated. Almost every shot-change forces you to readjust your attention, and a cut is less a link than a jolt. André Bazin was right to praise Welles’ long takes, but the Wonder Boy of the 1940s also loved disjunctive cuts, apparently from Too Much Johnson onward. Not all the harsh editing in The Lady from Shanghai and Macbeth can be attributed to studio interference. By the time we get to Othello, the same paste-up aesthetic governs almost every scene, with sound sometimes covering the gap and sometimes accentuating it.

Welles told Peter Bogdanovich that only the Greeks and the French classicists wrote true tragedies. Tragedy ought to be austere and pure, he seems to have thought. Shakespeare, he insisted, gives us high-level blood-and-thunder melodrama. So his Shakespeare films are rough and tumble, full of violent, strident effects, from the brimstone paganism of Macbeth to Othello’s Turkish-bath assassination. Here, it’s Falstaff and his followers providing earthy comedy, with Prince Hal enjoying the riotous living and the escalating slanging matches, where punning insults are swapped between gulps of sack. The glowing Boar’s Head versus the spare, chilly palace; fiery Fat Jack versus severe, monastic Henry IV; romps in the forest versus carnage on the battlefield—these are the options facing the young prince. Playing, as we now say, the long game, he warns Falstaff twice that when he assumes power, the old rogue will be cast off. When the new king follows his father’s advice “to busy giddy minds with foreign quarrels” (sound familiar?), you have to wonder if an occasional robbery of pious pilgrims is worse than Henry V’s cynical venture into patriotic gore: “No King of England if not King of France!” Falstaff, cold as any stone, is hauled off to his grave. Melodrama, again, and none the worse for it.

Thanks to Jared Case of George Eastman House who brought Too Much Johnson to us and provided lively commentary. Eastman House is the archive that restored the film, and is the site of The Nitrate Picture Show starting 30 April. (See you there?) Thanks as well to Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, and Mike King of our festival for many varieties of help. They do a swell job.

Frank Brady interviewed Welles extensively about the Too Much Johnson project, and the informative results are in Brady’s Citizen Welles: A Biography of Orson Welles, 145-151.

The Wisconsin Film Festival runs until 16 April, and there are many high points yet to come—not least, a 35mm screening of Where the Sidewalk Ends (15 April), which Kristin and I must miss (snif). The Cinematheque series continues this summer with a focus on Welles the actor, and in the fall with several rarities.

Of the many, many Welles celebrations this year, the Indiana University one later this month will surely be the lollapalooza.

Douglas Gomery’s trailblazing article, arguing that Welles was a prototype of the Hollywood independent, is “Orson Welles and the Hollywood Industry,” Persistence of Vision 7 (1989), 39-43. On Too Much Johnson, see Joe McBride’s in-depth piece at Bright Lights. There are too many excellent books on Welles to itemize here, but at the very least your shelf needs Peter Bogdanovich and Jonathan Rosenbaum’s This Is Orson Welles, Jim Naremore’s Magic World of Orson Welles, Joe McBride’s What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?, Jonathan Rosenbaum’s Discovering Orson Welles, and Simon Callow’s luxuriant two-volume biography. The most complete account of Welles’ stay in Madison that I know is in Peter Noble’s The Fabulous Orson Welles, pp. 26-33. The article about the Boy Wonder, age ten, appeared in The Capital Times (19 February 1926). Welles talks about Shakespearean plays as melodrama in the third audiocassette accompanying This Is Orson Welles, at 52:02.

Our analysis of Citizen Kane occupies chapters 3 and 8 of Film Art, and chapter 27 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema. There are many references to Kane and Ambersons on this site; check the Welles category. My 1967 review of Chimes at Midnight is here, on p. 9. It’s all too obviously the work of a twenty-year-old, and it demonstrates how it’s not really that hard to write a passable movie review. But at least it’s enthusiastic about the right things.

P. S. 13 April 2015: Joe McBride writes:

And Madison Mafia made man Pat McGilligan’s upcoming biog Young Orson: The Years of Luck and Genius on the Path to Citizen Kane will have many illuminating things to say about OW’s Madison days, as well as correcting other myths.

Thanks to Joe and best wishes to Pat, whose book will appear in August. For background on the Madison Movie Mafia, go here.

P.P.S. 13 April 2015: Manfred Polak advises me that the copy of Too Much Johnson that I linked is blocked for some regions of the world. It’s available for all on National Film Preservation Foundation pages. The complete 66-min. work print we saw in Madison is here and can be downloaded here. There’s also a 34-min. edited version, downloadable here.

Thanks very much to Manfred!

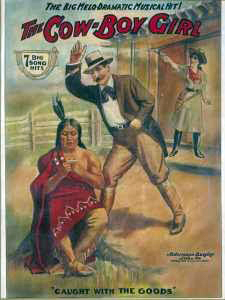

The AMBERSONS Poster Mystery: The clincher

DB here:

Bingo! Crowdsourcing pays off. Alert blogger Ivan Paio found the original poster that’s tucked into the Magnificent Ambersons frame! It confirms that Welles used not a film poster but one advertising a stage show…that could have played the Bijou in 1912.

If you’re not familiar with our quest, you can go here and here and here. Be sure to visit Ivan’s site for details, and give him a big hand.