Archive for the 'Directors: Ann Hui' Category

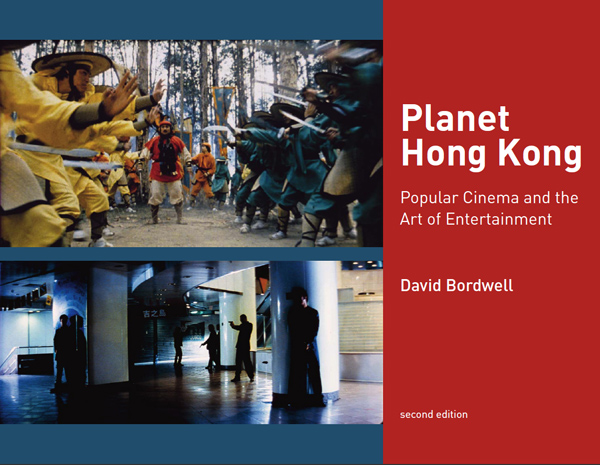

PLANET HONG KONG: Directors reframed

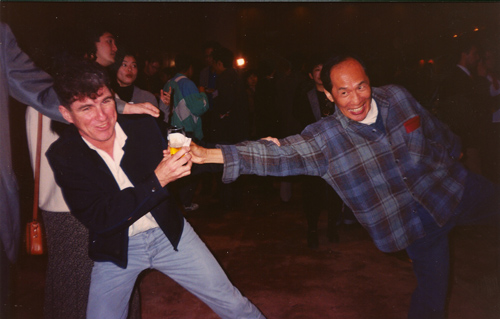

Your beer kung-fu is pretty good: Christopher Doyle and Po Chi Leung (Jumping Ash, He Lives by Night, etc.). Hong Kong Film Festival, 1996. Photo by DB.

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run daily entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have time or inclination to raise in the text. The first one, listing around 25 HK classics, is here. The second, a quick overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The third discusses principles of HK action cinema here. A fourth, a portfolio of photos of Hong Kong stars, is here. That was followed by a tribute to western Hong Kong fans. The final entry is concerned with the role of film festivals and a short list of other favorite films. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D.

When Andrew Sarris formulated an American version of the politique des auteurs, he used directorial “personality” as an index of true directorial creativity. Later, theorists and academics tried to define this elusive quality, and many concluded that auteur directors had recurring themes, a stylistic signature, and what we might call storytelling manner. To sketch an example: Welles can be thought of as concerned with the relation of power to love, and the loss of both. He favored aggressive depth compositions, long takes, and unusual uses of sound. In narrative terms, he was fond of stories featuring a larger-than-life man, turning on a puzzle or a crime, and presented in some time-shifting ways (e.g., flashbacks). This is a unsubtle characterization, but my point is simply that crtiics thought that recurring qualities like these offered a strong case for directorial authorship.

Yet a mass-market cinema makes “pure” authorship difficult, since directors may not freely choose their projects and their artistic preferences may be overridden by budgets, weather, producer rulings, censorship and the like. Creativity in a film industry, we’re usually told, requires collaboration. That’s true, but of course many other art forms do as well, notably theatre, dance, and song composition. A director may not explore favorite thematic concerns every time out (Look: stick to the script!), or may be thwarted in certain technical choices (We can’t afford long tracking shots!) or storytelling strategies (We’re adding a voice-over to clarify the backstory).

As with most high-output cinemas, the appeal of many Hong Kong films can be traced not to directorial flair but to the genre and other components (stars, scripts, studio resources). I wouldn’t say that many of the Jackie Chan-Sammo Hung-Yuen Biao outings like Winners and Sinners (1983), Wheels on Meals (this is not a typo; 1984), and My Lucky Stars (1985) exhibit much directorial personality, but they are skillfully made and pretty entertaining. Every industry needs its artisans, its steady hands on the tiller; it’s no mean feat to turn out a solid movie. Even the most distinctive directors in an industry need craft competence; as Sarris once remarked, “A great director has to be a good director.” Much of Planet Hong Kong is about the collective norms of local filmmaking, the tricks of the trade and the professional practices that shape the artistry of non-auteur movies.

But are there true Hong Kong auteurs? I think so, to various degrees. Ones discussed in PHK 2.0 are King Hu, Chang Cheh, Lau Kar-leung, Tsui Hark, Wong Kar-wai, and Johnnie To Kei-fung. John Woo, I argue, is one in a special, almost meta-sense: He understood the idea of authorship and crafted his public image, as well as his films, around certain themes (Christianity, heroic self-sacrifice) and stylistic choices (most visibly, flying pistoleros).

Wong Jing is a bit meta- too, in the way that Mel Brooks is a parodic auteur. Wong Jing’s farcical cinema carries to an extreme the vulgar potential always lurking in his territory’s cinema. He can provide quite precise mockery of other (better) directors, as when the arthouse filmmaker in Whatever You Want (1994) turns out a pretentious effort suspiciously similar to Ashes of Time. The evocative, fragmentary shots of Carina Lau Ka-ling clutching at her horse are replaced by one of Law Kar-ying caressing a cow.

So it was in hope of learning both about craft norms and directorial temperament that between 1995 and the present I’ve visited and talked with various filmmakers. The results are in the book, but here are some photos commemorating the encounters.

Here Ann Hui On-wah presents Wong Kar-wai with the best screenplay award (for Ashes of Time) at the first annual Hong Kong Film Critics Society Awards, 1995. She looks as happy as he is. The film also won Best Film, Best Director, and Best Actor (for Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing, who wasn’t present). For a further note on Wong, check the bottom of this entry.

My longest stay in Hong Kong was during the spring of 1997. Doing research for PHK, I interviewed several people. One of my top stops was BoB & Partners, then the latest incarnation of Wong Jing’s entrepreneurship. (On the wall in the left still you see posters for Naked Killer, 1992, and other genre classics.) BoB stood for “Best of the Best,” and one of the partners was Andrew Lau Wai-keung, top-flight cinematographer who had become famous as a director with the Young and Dangerous series. Soon he was to go on to Storm Riders (1998) and eventually to the Infernal Affairs trilogy (2002-2003). Next door, Wong Jing also talked with me. He had several TV screens facing him, one with video games, and you can see his console front and center on his desk.

Another busy man, Peter Chan Ho-sun, had become an important director of contemporary comedies and dramas (e.g., He’s a Woman, She’s a Man, 1994; Comrades, Almost a Love Story, 1996). I met him in 1997 and brought him to Madison in 1999; below, a photo from 2008. Even more prolific, and less easy to categorize, is Herman Yau Lai-to–DP, rock-and-roller, and director of everything from grossout horror (The Ebola Syndrome, 1996) to harsh social critique (From the Queen to the Chief Executive, 2001; Whispers and Moans, 2007). How could you not learn a lot about filmmaking craft from a guy who had directed over fifty movies and been DP on thirty-five more? I wrote about Herman’s On the Edge here.

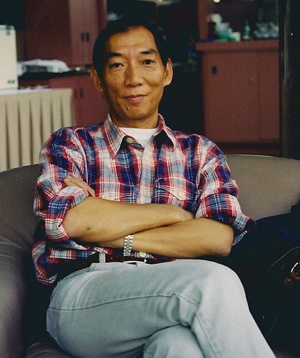

I met some directors from the older generation too. There was Yuen Woo-ping (aka Yuen Wo-ping), one of the great fight choreographers (The Matrix, Kill Bill) but also a lively director in exhilarating films like Legend of a Fighter (1982), Dance of the Drunk Mantis (1979), Iron Monkey (1993), and Tai-chi Master (1993). And there was Ng See-yuen, another local legend. He directed some sturdy kung-fu films like The Secret Rivals (1976) and The Invincible Armour (1977). He’s also an iconoclastic producer, backing Jackie Chan’s breakthrough film Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow (directed by Yuen Woo-ping), Tsui Hark’s Butterfly Murders (1979) and We’re Going to Eat You (1980), and several of the Once Upon a Time in China entries. Here Ng is at the 1997 Hong Kong Film Awards.

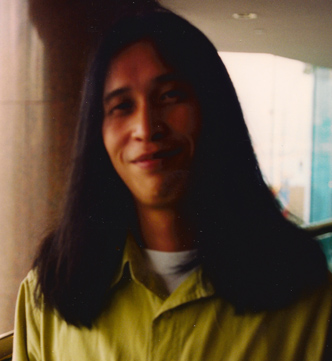

Two of the high points were my interviews with major figures of the Hong Kong New Wave of the 1980s, both still going strong in 1997. Ann Hui was warm and generous with her time; she visited Madison that year with Summer Snow (1995) and other films. The picture below is from 2005.

Then there was my several-hour talk with Tsui Hark at the Film Workshop headquarters. Good thing I taped it; I couldn’t keep up with him in my note-taking. He was planning Knock-Off and the animated version of Chinese Ghost Story.

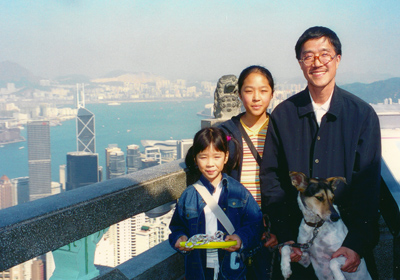

After 1997, I looked in on some other filmmakers. I was invited to visit the Academy for the Performing Arts in 2001 under the guidance of Professor Lau Shing-hon, another early New Waver (House of the Lute, 1980; The Final Night of the Royal Hong Kong Police, 2002). Here he is with his family on the Peak.

Since I started blogging, I have put my best (or rather the least amateurish) shots online. So for more snaps, you can rummage through the category, Festivals: Hong Kong. But I can’t resist two final ones. Here are Johnnie To and the younger director Soi Cheang Pou-soi (Love Battlefield, 2004; Dog Bite Dog, 2006; Accident, 2009), in shots from 2005 and 2009 respectively.

And now for something not quite completely different. In both print and e-book editions of Planet Hong Kong, I wrote about our last view of the Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia’s character in Chungking Express. Wong Kar-wai presents a jerky slow-motion shot of her leaving the crime scene and dodging out of the frame. It freezes on her, at a moment that yields a perversely unreadable image.

A shot of this frame would have been mud in the black-and-white pages of the book and probably not much better in the color pdf. I couldn’t imagine catching the faint reddish glint of the woman’s sunglasses. (Actually, the e-book’s quality turned out well enough that we might have tried for it.) So I picked the most legible image I could find from the shot, and that’s what’s in the print book and the digital copy (Fig. 9.13).

In any case, for obsessives like me, I reproduce the frozen frame here. This still comes from a 35mm print of the movie, and it is, of course, a lot more poetic than my snapshots, partly because it teases you about what’s in the frame.

PLANET HONG KONG now in cyberspace

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run a daily string of entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have a chance to raise in the text. This is the first one. The second, a quick overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The third, on principles of HK action cinema, is here. The fourth, a photo portfolio of HK stars, is here. The following ones deal with western fandom, some Hong Kong directors, and final reflections on film festivals and a list of other intriguing movies. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D.

± 25 classics: A cheat sheet

Rouge (1988).

I have an aversion to list-making (some day I’ll explain), but I’m often asked to recommend Hong Kong movies to people wanting a quick start. So I’m launching this suite of daily entries around Planet Hong Kong by charting some widely recognized high points in this effervescent cinema.

Some items are important for their historical influence, some for their intrinsic quality, some for both. I’m restricting myself to the years after 1960, although there are several influential and powerful films before that (e.g., In the Face of Demolition, 1953). Still, if you want a fair sample of this cinema’s output you must sample these more or less official classics. If the bug bites, you can supplement them with other items that I’ll mention in passing here and in the days to come. Several of these films are discussed in more detail in the book, and most are available on DVD.

The Wild, Wild Rose (1960): Cathay (to use its shortest name) was one of the two major companies of the 1960s and in this brassy show-business drama Grace Chang (Ge Lan) had her defining role as the Carmen of the nightclub scene. Another Grace Chang classic is Mambo Girl (1957), and you can get a sense of the gorgeous star culture of Cathay by seeing her and other top actresses in Sun, Moon, and Star (1961), sort of a Hong Kong Gone with the Wind.

The Love Eterne (1963, above): This adaptation of the “plum-blossom” opera was given lavish treatment by the Shaw Brothers studio, the major studio of the period. Li Han-hsiang’s spectacle of colorful costumes, big studio sets, and gender masquerade won several awards and helped establish Hong Kong films across Asian markets. Li went on to make many other sumptuous costume pictures, as I discuss briefly here and in subsequent entries. This web essay focuses on Shaws’ anamorphic output.

Come Drink with Me (1966): The first Shaw entry in its new martial arts cycle, pioneered by King Hu. In an inn various characters in disguise meet and bluff one another; eventually the woman warrior Golden Swallow takes on all comers. Strictly speaking, King Hu’s other films belong to Taiwanese cinema, but he is one of the greatest of all Chinese directors, so you will naturally want to see Dragon Gate Inn (1967), The Fate of Lee Khan (1973), The Valiant Ones (1975), and his official masterpiece, A Touch of Zen (1971). I give him a fair amount of space in Planet Hong Kong because of his historical importance and his innovations in the aesthetics of action. I talk a little about those innovations here.

Golden Swallow (1968): Shaws’ dominant director from the late 1960s onward, Chang Cheh specialized in films of “staunch masculinity,” martial arts pictures that replaced the female-centered romances and opera films. Golden Swallow shows the woman warrior, the nominal protagonist, muscled aside by a typical brooding Chang hero—Jimmy Wang Yu, acting as if he still nursed a grudge from being The One-Armed Swordsman (1967). Later Chang developed the masculine pairing of Ti Lung and David Chiang Da-wei (Blood Brothers, 1973) and the brawny teamwork of what came to be known in the West as the Five Venoms (as in Invincible Shaolin, 1978).

Fist of Fury (1972): Child star Bruce Lee came home from Hollywood, and his first kung-fu film, The Big Boss (1971), was a sensation. The most influential star in all Hong Kong cinema, Lee stands at the center of his classics; the plots, staging, and shooting simply set off his glowering charisma. Fist of Fury provides a string of archetypal scenes: he wipes the floor of a dojo with its students and master, he kicks to splinters a sign barring Chinese from a park, and he ends his life by hurling himself, shouting, into a hail of bullets. Remade as the no less enjoyable Fist of Legend (1994) with Jet Li.

The House of 72 Tenants (1973): The success of Shaw Brothers’ export-driven Mandarin-language product led to a decline in films made in Cantonese, the local language. (Hong Kong audiences heard Bruce Lee dubbed into Mandarin.) 72 Tenants, based on a popular play, brought back Cantonese cinema in a crowd-pleasing guise. Under the direction of veteran Chor Yuen, the crisscrossed stories of neighbors became an enduring reference point for local cinema—cited again last Lunar New Year in 72 Tenants of Prosperity.

The Private Eyes (1976): Another victory for Cantonese vernacular cinema. The Hui brothers, popular from television, brought their episodic sight-gag comedy to the big screen and were among the biggest stars of the 1970s. There are many classic scenes, including Michael and Sam’s sleight of hand with candies, a shark attack in a kitchen, and a bout of chicken aerobics—plus a weird contagion of neck braces. See also Security Unlimited (1981) and, for fairly daring mockery of Beijing, The Front Page (1990).

The 36th Chamber of Shaolin (1978). As his employer Shaw Studios was fading from the scene, Lau Kar-leung (aka Liu Chia-liang) created in nearly twenty films a virtual encyclopedia of the kung-fu tradition. Any choice among the films is arbitrary (I’ll mention more in a future entry), but let this exuberant display of color, movement, and emotion stand as an outstanding accomplishment. A young man burning with rebellion enters the Shaolin monastery. Through persistence and discipline he achieves the highest distinction and returns to his home town to fight the Manchu oppressors. Featuring the director’s brother Gordon Lau Kar-fai and Lo Lieh, both martial-arts icons.

Young Master (1980): Jackie Chan’s comic kung-fu caught fire in Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow (1978) and Drunken Master (1978). Young Master is a prime instance of his rubbery energy and bottomless masochism. It benefits from extended byplay with Yuen Biao, splendid jumper, and Shek Kin, patriarch of the Hong Kong martial arts movie. Soon Jackie would show both ambition and directorial prowess in Project A (1983), his leap into big budgets and pan-Asian superstardom.

Aces Go Places (1982): The most successful franchise in Hong Kong history was launched by this jaunty action comedy, stuffed with pratfalls and high-tech chases. The buffoonery was carried off by an unruffled Sam Hui Koon-kit and a sprightly Sylvia Chang Ai-chia, not to mention the robots. Any film is improved by robots.

Boat People (1982): Ann Hui On-wah, a practitioner of serious drama for over thirty years, established her reputation in world cinema with this poignant story about a photographer’s discovery of children cast out by war. Her earlier film about Vietnamese refugees, Story of Woo Viet (1981), gave TV actor Chow Yun-fat his first major film role. Another characteristic Hui work is Song of the Exile (1990).

Zu: Warriors of the Magic Mountain (1983) Which early film by Tsui Hark to choose? The Butterfly Murders (1979) looks forward to his recent Detective Dee; the hectic We’re Going to Eat You (1980) suggests Romero turned loose in China; many critics pick Dangerous Encounter—First Kind (1980), a rough-edged Buñuelian indictment of class differences. With Zu, however, Tsui showed his resolve to update classic genres, in this case the Cantonese swordplay fantasy, using modern technique and special effects—a trend that has continued right up to the recent Storm Warriors (2010). Go here for more thoughts on Tsui.

Police Story (1985): Possibly Jackie Chan’s directorial masterpiece. A rip-roaring auto chase through a hillside shantytown, capped by a runaway bus, would be the climax of any other movie, but here it’s just for openers. The film ends with a fight in a shopping mall that, for precision and visceral impact, deserves to be ranked with the great sequences in film history. More on this scene here.

Peking Opera Blues (1986): The woman warrior’s shining hour, complete with the obligatory cross-dressing. Tsui Hark moves toward historical action/ adventure in a breathless movie that showcases three great beauties: Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia, Sally Yeh, and Cherie Chung Cho-hung.

A Better Tomorrow (1986): The film that defined a generation and cemented Chow Yun-fat’s star stature. John Woo came out of Taiwanese exile to make a film that revived the Chang Cheh spirit of brotherhood, made even more romantically doomed by the idea that Hong Kong was living on borrowed time.

Rouge (1988): A courtesan’s ghost revisits contemporary Hong Kong and finds that no one else is willing to die for love—not even the man who pledged to join her in death. Stanley Kwan Kam-pang’s delicate yet straightforward handling of the plot, refusing all special effects, gives an extra poignancy. Others would suggest Kwan’s Centre Stage (aka Actress, 1992), a biographical study of the great film star Ruan Lingyu.

The Killer (1989): The Chow/ Woo collaboration that brought them to the attention of the West. Often imitated, at home and abroad, the original retains its bold lyricism and outlandish emotion: crime and punishment as (mostly male) melodrama, accompanied by cadenzas of annihilation. To be supplemented by A Better Tomorrow II (1987), Bullet in the Head (1990), and Hard Boiled (1992), all of which brought awed fanboys to their knees.

God of Gamblers (1989): A financial triumph for bad-boy producer/director Wong Jing and the definitive gaming movie for a town that loves a bet. Shamelessly cheesy in its plot mechanisms, surprisingly elegant in its direction, the movie yanks us from laughter to pathos. Plus Chow Yun-fat in a tuxedo. To be seen alongside Stephen Chow Sing-chi’s parody All for the Winner (1990).

Days of Being Wild (1990). Wong Kar-wai’s breakthrough film about young people adrift in the early 1960s. A dazzling array of stars (Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing, Maggie Cheung Man-yuk, Andy Lau Tak-wah, et al.) creates a languid movie about the magnetic pull of selfish passion. For many local critics, the most important film of the last thirty years. I discuss a rare alternate version of the film here.

Once Upon a Time in China (1991): Tsui Hark doing Movie Brat revisionism again, this time with the Southern Chinese folk hero Wong Fei-hong. This flamboyant exercise in fervent nationalism ushered Mainland wushu champion Jet Li onto the world stage. If Bruce Lee radiated a cocky sexual energy, this film helped establish Li’s star image as a shy and chaste warrior.

Chungking Express (1994)/ Ashes of Time (1994): A coin-flip. The first showed that Wong Kar-wai could make a movie fast, cheap, and charming. The second showed that a swordplay film could be drenched in romantic longing. Both bristled with audacious storytelling tactics. Chungking spliced two stories together (prefigured in the way characters bump into each other), while Ashes zigzagged and spiraled in time, refusing plot certainties but offering a hypnotic reverie instead. Western critics and fans, notably one Q. Tarantino, sat up and noticed. PHK devotes an entire section to Chungking; go here for more on Ashes of Time.

The Mission (1999): Johnnie To Kei-fung’s stealth classic. Made on a shoestring, shot in less than three weeks (without a developed script), filled with great character actors, this ascetic polar has some of the subtlest plot twists in Hong Kong film. If Kitano Takeshi in his prime had made a Hong Kong film, it might look like this. Of course the mall shootout has become a classic.

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000): This US-Hong Kong-Taiwan project showed that the world was ready for the wuxia pian, or film of heroic chivalry. CTHD became the top-grossing foreign-language film in U. S. history. The versatile Ang Lee centered the drama on two couples, one young and one older, and their life in the jianghu–that virtual, larger-than-life world of forests and rivers that tests warriors’ righteousness. Lee’s film prodded Zhang Yimou to make the artier Hero (2003), first in a procession of historical dramas that helped revive the Mainland film industry.

In the Mood for Love (2000): Julia Roberts’ favorite movie, I’m told. Revisiting the period and perhaps some of the characters of Days of Being Wild, Wong Kar-wai evokes muffled yearning through averted glances, hidden faces, radiant costumes, and a typically spine-tingling soundtrack. This Cannes prizewinner was given a sequel, 2046 (2004), that is harsher but no less romantic in its commitment to cherishing the past.

Infernal Affairs trilogy (2002-2003): A deliberate effort to break away from the hell-for-leather action film, the IA trio showed that Hong Kong filmmakers could construct a taut, restrained crime plot. The first installment is a compact, efficient suspense exercise, the second a wide-ranging exploration of betrayal, and the third a fairly daring experiment in time-shifting and subjectivity. Many recent crime films have taken their cues from the trilogy’s huge box-office success. Portions were remade as The Departed, and for once it was the Hollywood movie that was overblown (not least the contribution of Mr. Nicholson). I set down some thoughts on the two versions here and here.

Kung Fu Hustle (2004): Stephen Chow purists may consider it a case of comedic elephantiasis, but this big-budget extravaganza is historically significant for winning worldwide distribution and big box-office. Kung Fu Hustle is also packed with engaging CGI-enhanced gags, on every scale from tenement demolition to cobra-smooching. One of the funniest scenes will encourage you not to use the phrase “hair on fire.” The even more inventive Shaolin Soccer (2001) was Chow’s previous step toward making movies at once China-friendly and globally marketable; not for nothing is his company called The Star Overseas.

Later this week I’ll offer a list of other Hong Kong films that I think are worth attention. (So wait until you’ve seen all my picks before writing me to point out titles I’ve omitted here!) And somewhere I’ll try to wedge in some outstanding sequences. This is nothing if not a cinema of rousing set-pieces.

Nearly all the films I mention are available on DVD, with European and American editions usually being of superior quality to Hong Kong editions. Many of the filmmakers mentioned are discussed in other entries on our site; check the Directors category on the right.

In 2005, Chinese critics assembled a list of the 103 best films from the PRC, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. That list can be found here.

PS 3 Feb: Another list of top Chinese films, tilted somewhat toward Taiwan, is here.

A Better Tomorrow (1986).

The postman has rung more than twice

Optical Vacuum.

DB here:

While I try to whip up seven lectures for the Bruges Summer Film College and a couple more for the University of Copenhagen and our June Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image confab, I offer some quick notes on notable DVDs and books lugged to our door by our mailman.

When machines film better than they know

Snow blankets a terrace and the furniture on it. A bottle jerks back and forth on a pavement. Christmas lights blink on and off. Everything looks desolate. What people we see scuttle across washed-out landscapes, play mahjongg in stammering gestures, and toil in computer labs under glaring fluorescent lights. What planet are we on?

These images are available to any of us. For two years Dariusz Kowalski trawled through sites like www.opentopia.com for surveillance-camera footage. He chose only material from hidden cameras. He added nothing except some slow motion (“otherwise it would be too fast”) and a voice-over commentary from artist Stephen Mathewson reading passages from a year’s diary. The result was a fifty-five minute assemblage film called Optical Vacuum (2008), which I saw and admired in Hong Kong back in April.

Sometimes the diary account intersects with what we see: Mathewson talks of washing his laundry/ shots of a Laundromat. More often, the voice drifts off on its own. Optical Vacuum isn’t an effort to make a film essay or to create a complex audiovisual dynamic. Mathewson’s diary provides an intimacy that the footage lacks, but I think the film would stand up strongly without it.

As a flow of impersonal views, usually from a distant perch, the footage creates a bleak beauty.

Occasionally a human operator has commanded the camera to focus on something, usually a woman.

But most often the camera is just mindlessly recording.

In the process, the surveillance camera reinvents avant-garde film—not just the barely inflected fields of Structural cinema, but also the time compression and melting glimpses, the reflections and superimpositions, the transient ghosts and brutal geometry we find in silent experimental work by Richter, Vertov, and others. These stupid cameras can’t help turning reality into something else. They don’t know any better.

Optical Vacuum, along with other pieces by Kowalski, can be found on a PAL uncoded DVD from the extraordinary Austrian collective sixpack. The handsomely mounted Index release is available here, and elsewhere on the Net.

Dragons and tigers in the Udine sun

Italian festivals of specialized cinema are mounted with incomparable flair–lots of screenings, panels, interviews, book sales, and of course outstanding food. Most famous are Pordenone’s festival of silent cinema and Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato. But for admirers of Asian cinema, just as important is the Udine Far East Film event, which completed its eleventh installment on 2 May.

Italian festivals of specialized cinema are mounted with incomparable flair–lots of screenings, panels, interviews, book sales, and of course outstanding food. Most famous are Pordenone’s festival of silent cinema and Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato. But for admirers of Asian cinema, just as important is the Udine Far East Film event, which completed its eleventh installment on 2 May.

Alas, I’ve never been. In its earliest years it overlapped with the Hong Kong film festival; more recently, my commitments elsewhere, such as Ebertfest, have kept me away. But I have followed this celebration of Asian cinema at a distance through its remarkable publications.

The Udine event concentrates on popular cinema, mostly recent releases that are unlikely to come to US theatres or video stores. You can see films from Japan, Korea, and China but also from Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines. This year’s highlights include regional hits like Cape no. 7, Beast Stalker, Departures, and Ip Man as well as obscure and delirious items like Love Exposure and The Forbidden Legend: Sex and Chopsticks. Many screenings are European premieres.

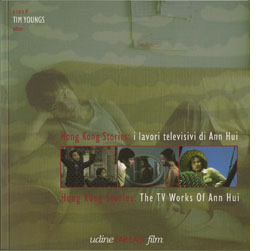

The programmers also mount adventurous retrospectives of rare items. One year it was a survey of the work of Patrick Tam, still too little known among Asian aficionados. This year the retrospective was devoted to Ann Hui’s TV films, which are among her best work. These films, shot in 16mm and broadcast in the 1970s, were strong meat for a culture unused to social criticism in its popular media. Hui’s dramas showed police corruption, the sex trade, abandoned children, and drug addiction. The episodes were researched and scripted under great time pressure, and Hui was allotted two weeks for shooting and post-production. “We were experts at shooting in the streets on the sly.” The stories’ concern for ordinary people and their problems has resurfaced again in The Way We Are (2008) and Night and Fog (2009).

The Hui volume is a model of the profuse documentation the Far East festival provides. Several concise essays, all in both English and Italian, enhance appreciation of the films. Contributors Law Kar, Shu Kei, and editor Tim Youngs do a fine job of situating Hui’s TV work in its context, and a lengthy interview with the director explores her working methods and intentions. There’s also valuable filmographic information about the episodes (four of them available on DVD).

The Hui volume is a model of the profuse documentation the Far East festival provides. Several concise essays, all in both English and Italian, enhance appreciation of the films. Contributors Law Kar, Shu Kei, and editor Tim Youngs do a fine job of situating Hui’s TV work in its context, and a lengthy interview with the director explores her working methods and intentions. There’s also valuable filmographic information about the episodes (four of them available on DVD).

As if this weren’t enough, the Udine event publishes a mammoth catalogue called Nickelodeon. Each year it’s a treasure chest of enthusiastically presented information. This time around, surveys of 2008 developments in all the major countries are accompanied by Roger Garcia‘s special section on the history of Thai action cinema. A vast section of reviews of the films to be shown rounds out this gift to the Asian cinephile. (A little of this material is available at the Udine site.) There is no coordinated effort to sell the books to the public, but if you want to purchase them, try writing to the festival directors at cec@cecudine.org.

So a tip of the hat to the dedicated Udine team, headed by Sabrina Baracetti, and a signal to you that if you have the time and the money to go, you would surely have a hell of a week. (Note that professors and students are offered lodging for some nights.) Who knows? A director might show up to put the audience in a movie, as Johnnie To once did. Even if you can’t make the trip, the quality of the publications makes them indispensible for research and enjoyable reading.

Rabbits from a hat

It’s tiresome to hear novelists kvetching that film adaptations mangle their work. So it’s a pleasure to read Christopher Priest’s brisk account of how his novel The Prestige became a film. In The Magic: The Story of a Film Priest takes us through the whole process, but this isn’t the usual behind-the-scenes tour. He never visited the set or met the principals. Instead we get the viewpoint of a writer living in East Sussex, following the production through agents’ correspondence and the gossip frothing up on Google Alerts.

It’s tiresome to hear novelists kvetching that film adaptations mangle their work. So it’s a pleasure to read Christopher Priest’s brisk account of how his novel The Prestige became a film. In The Magic: The Story of a Film Priest takes us through the whole process, but this isn’t the usual behind-the-scenes tour. He never visited the set or met the principals. Instead we get the viewpoint of a writer living in East Sussex, following the production through agents’ correspondence and the gossip frothing up on Google Alerts.

Priest is a lively writer, and he is frank about the ups and downs of the process. Initially he is happy that Nolan acquired the rights because the novel, a cunningly designed piece of misdirection, seems ideal for the director of Memento. But he confesses disappointment when the Prestige project is sidetracked by Batman Begins (“overlong, simplistic, and dull”). When the production gets under way, there are more swerves in the road. Given an early script, Priest admires the craftsmanship of Jonathan Nolan. But then he’s baffled that Christopher Nolan is saying two inconsistent things: that the film is completely different from the book, and that reading the book will spoil the film. Then again, during a press preview in Leicester Square, Priest succumbs to the film’s intricacies. “It has one of the most complicated and sophisticated narrative structures ever seen in an entertainment film.”

The story of the production ends here, but Priest goes on for about fifty pages to analyze the film in considerable detail. He dwells on the opening, which has no equivalent in his novel, and praises it for its fluent shifts among different points in story time. He appraises various aspects of the film, and he doesn’t stint criticisms. He notes that the Nolans stripped off his contemporary story, crucially altered the roles of the women, and turned his elusive mysteries into plot-driven secrets. Yet he concludes:

There is hardly a line of dialogue or moment of action in the film that can be traced back word-for-word, yet the whole thing is faithful to the novel in spirit, in story and in effect. I have differences with the screenplay in places, but none of those detracts from my general impression that it is a classic film adaptation of an existing novel, one which intending screenwriters would do well to study alongside the novel. (157).

Priest is a former movie critic (for the sturdy old British Film Institute publication Film) and an astute observer of what happens in a shot and on a soundtrack. He contacted me after my March blog entry discussing micro-repetitions in The Prestige and told me of The Magic. I ordered a copy pronto, and I’m glad I did. If you want to give your mail carrier a bit more job security, go to this page and click on GrimGrin Studio.

A masterpiece, and others not to be neglected

About Elly.

DB still in Hong Kong:

I haven’t been slack, honest; I’ve caught several items at the archive and during the first weekend of the Film Festival. I even saw Watchmen, accompanied by rump-shaking Shaw Active Sound. But today let me get caught up with some films I saw in Filmart last week.

I was unimpressed by the picture that launched Filmart, Derek Yee’s Shinjuku Incident. Billed as Jackie Chan’s emergence as a real actor, it features him as a confused illegal immigrant thrown into the Tokyo underworld. His character never made sense to me, and the direction was formulaic: basically pan around a group of actors until somebody says something. Daniel Wu gets to play another maniac.

Less heralded Filmart screenings were much more satisfying. The best, and my favorite film I’ve seen so far this year, was About Elly. It is directed by Asghar Farhadi, and it won the Silver Bear at Berlin. I can’t say much about it without giving a lot away; like many Iranian films, it relies heavily on suspense. That suspense is at once situational (what has happened to this character?) and psychological (what are characters withholding from each other?). Starting somewhat in the key of Eric Rohmer, it moves toward something more anguished, even a little sinister in a Patricia Highsmith vein.

Gripping as sheer storytelling, the plot smoothly raises some unusual moral questions. It touches on masculine honor, on the way a thoughtless laugh can wound someone’s feelings, on the extent to which we try to take charge of others’ fates. I can’t recall another film that so deeply examines the risks of telling lies to spare someone grief. But no more talk: The less you know in advance, the better. About Elly deserves worldwide distribution pronto.

Also worth seeing was A Place of One’s Own, a Taiwanese film that uses imagery of living spaces to explore generational differences. As a young rock singer’s career fades, his pop-star girlfriend’s career takes off. Their fates are intertwined with those of a family who live near a cemetery. The father makes exquisite paper dwellings that are burned during funeral ceremonies, the mother maintains gravesites (and talks to ghosts), while the son launches himself on a real-estate career with the help of a dodgy rich kid. Director Ian Lou (God Man Dog) enhances this network narrative with some clever flashback constructions as well.

My Dear Enemy.

Two films I saw in the market display different ways of using past incidents to explain a story’s present-time crises.

My Dear Enemy, by Lee Yoon-ki, exhibits a striking concentration and dramatic focus. Hee-soo’s boyfriend Cho borrowed $3500 from her before they broke up. Today she has tracked him down and demands it back. She drives him around as he visits various associates—his biker cousin, a high-class prostitute, a rich older woman who seems to be using his sexual services, an unmarried mother—scrounging for money to pay Hee-soo back. Across a day of setbacks both comic and frustrating, we come to learn of their romance and their deeper personalities.

At first Cho seems the classic annoying charming rogue, chattering about the music he likes, pausing to buy flowers and oversweet coffee, flattering every woman he meets, and on the verge of ducking Hee-soo’s demands. Every time he gets out of the car, you think he might bolt. These first impressions, however, get nuanced as we see how he moves easily and even gracefully through his milieu. He seems a loser, but we learn that he is resilient and resourceful. Meanwhile Hee-soo’s righteous determination to get her money back comes to seem something of a desperate effort to close the book on painful episodes from her past.

Lee Yon-ki, who earlier gave us This Charming Girl, is very good at structuring scenes so that we understand every character’s changing attitudes. To get the money, Cho lets his target think that he’s helping out Hee-soo, and at one point he implies that she’s pregnant. As Hee-soo realizes that he’s making her play a part in his drama of self-aggrandizement, she is hurt and ashamed. And Cho’s happy-go-lucky facility in his milieu makes her feel more of an outsider. One scene, in which Cho’s hooker friend calmly insults Hee-soo, is a subtle study in casual humiliation.

Yet Hee-soo’s tenacity wins Cho’s respect. At the same time, while as the day passes into night, Cho emerges as a figure with his own code of honor (he eventually provides a meticulous account of what he’s cost her in the day’s expenses) and even a dream of success that might, the last shot suggests, be fulfilled. Bits of business around coffee, cellphones, flowers, and a broken windshield wiper chart the fluctuations in their relationship concisely. My Dear Enemy is a model of how to make a tight, intimate movie focused on simple incidents that carry almost Hitchcockian tension: Will Cho pay Hee-soo off? Will he slip away and abandon her again? What will we learn next about each one’s past? Like About Elly, this is a character study with an engrossing plot.

More diffuse, I thought, was Ann Hui’s unfortunately titled Night and Fog. It’s a companion piece to The Way We Are, her 2008 study of life in the Tin Shui Wai area of Hong Kong. I offered an admiring account here.

This is the “darker story” Ann promised us at last year’s festival, and it’s based on an actual case. Lee Sum has married a Mainland woman, Ling, and has fathered two daughters with her. He’s on social security and Ling works as a waitress. But Lee is considerably older, and he suspects her of flirting with other men. He becomes insanely jealous, beating her and throwing her and their daughters out. Ling finds happiness in a woman’s shelter, but social services fail her and Lee brutally murders her and the children.

No harm in telling you the ending because the murder is the first thing we see. The film consists of a series of flashbacks, some nested within others, that trace what led up to Lee’s horrendous crime.The plot is presented in the framework of a police investigation, with witnesses to Ling’s life answering questions that pass into scenes from the past. The early flashbacks are quite linear, treating the buildup to Ling’s stay in the shelter and a moment in which she sings a song about a mushroom maiden. Then we plunge further into the past, showing her leaving her provincial home as an adolescent on the way to work in the city. Soon we’re given early moments in Lee’s courtship of her.

One effect of introducing the early stages of their marriage late is to mitigate the harsh portrayal of Lee that has dominated the first half of the film. He seems genuinely in love with Ling, and he rebuilds her parents’ home. Already, however, we glimpse his drunkenness, his sadism, and his aggressive sexual appetites.

On the whole, I’m not sure that this complicated flashback structure serves the film well. At times it is strikingly symmetrical, as when a scene of Lee returning from Shenzhen on the train is followed by a distant flashback of the marriage, and this is closed off by a shot of Ling and her daughters traveling on the same train. At other points, though, the relation between the witness’s testimony and the flashback episodes is arbitrary, with the flashbacks showing scenes unrelated to that witness’s knowledge of the family drama.

It seems to me as well that the power of the events leading up to Lee’s murder of his family is vitiated by the protracted Mainland visits, widening the film’s field of view to life in Sichuan and Ling’s family. Where My Dear Enemy lets its backstory emerge in piecemeal fashion through hinting dialogue, dramatizing every relevant moment in Ling’s past seems to lose some focus.

Likewise, there’s a certain fuzziness about the film’s main thrust. Is it a character study, trying to explain why Lee is violently jealous and why Ling stays with him? The only clear answer I could determine was her sense of indebtedness for his help to her parents. Is Night and Fog then best taken as a critique of the Hong Kong bureaucracy? The social workers are portrayed as indifferent or unable to understand domestic violence. But in that case we need to see more of the mechanisms of decision-making than we do, and then many of the intimate relations of the couple would be extraneous. The battered women’s shelter, while not unblemished, becomes the opposite pole to Ling’s dangerous household, and Huipresents it as a safe space where women can express their feelings spontaneously. But again, this angle on the material seems vitiated by bringing in a public protest against real-estate development of the harbor area—an important issue, but in the context a bit distracting.

The film seems to me to excel in areas that Hong Kong cinema has made its own: extreme emotion and sheer physicality. The violence of Lee’s assaults on his family are terrifying, and Simon Yam’s performance is tremblingly ferocious. Smoking furiously, swigging cans of beer, Yam gives us Lee Sum as a figure on the edge of destruction. He makes even fishing seem an act of aggression. Lee’s incessantly jiggling leg is like the timer on a pressure cooker, and when he sits down with his son from a previous marriage—a sleepy-eyed young pimp—the two of them share the same foot-jiggling tic. In this shot, Hui gives us a diagram of male aggression ready to burst.

If My Dear Enemy trades on suspense, Night and Fog creates dread. One is roundabout, the other more direct; one suggests much, the other shows everything. Two ways, we might say, of making modern cinema.

More, including another Iranian masterpiece, in my next communiqué.

Night and Fog.