Archive for the 'Actors' Category

THE SOCIAL NETWORK: Faces behind Facebook

DB here:

What do John Ford, Andy Warhol, and David Fincher have in common? Eyeball these remarks.

Ford, asked what the audience should watch for in a movie: “Look at the eyes.”

Warhol: “The great stars are the ones who are doing something you can watch every second, even if it’s just a movement inside their eye.”

Fincher, on the big club scene in The Social Network: “What’s cinematic are the performances . . . . What their eyes are doing as they’re trying to grasp what the other person is telling them.”

It isn’t just cinema that makes eyes important. Eyes are felt to be significant in literature, from the highest to the lowest. In just a couple of pages of a pulp adventure story you can read these sentences:

“Then it certainly does look very mysterious,” he said, but his blue eyes were quiet and searching.

Chief Inspector Teal suddenly opened his baby-blue eyes and they were not bored or comatose or stupid, but unexpectedly clear and penetrating.

What do quiet eyes look like, actually? Or searching ones: perhaps they’re moving a bit? Bored or comatose eyes might be droopy, so let’s count the eyelids as part of the eye. But what could make eyes, by themselves, penetrating? Nonetheless, we think we understand what such sentences mean.

Watching eyes is tremendously important in our social lives. We need to monitor other people’s glances to see if they are looking at us. We need to track what else they might be looking at. We need to watch for signals sent by the eyes, particularly attitudes toward the situation we’re in. For example, we seldom look directly into each others’ eyes, as characters in movies do constantly; in real life, “mutual gaze” is intermittent and brief. But if two people stare intently at each other, we’re likely to assume keen attraction or rising aggression.

In an essay from Poetics of Cinema available on this site, I talk about mutual gaze in cinema and how it can be exploited for dramatic purposes. The same essay takes up the issue of blinking; we blink frequently, but film characters seldom do, and the actors usually make the blinks emotionally expressive (of fear, uncertainty, weakness, etc.).

The problem is that eyes, by themselves, tell us very little about what the person behind them is thinking or feeling. We can show this with a little experiment.

Do the eyes have it?

What do these eyes tell us?

Certainly they give us information–about the direction the person is looking, about a certain state of alertness. The lids aren’t lifted to suggest surprise or fear, but I think you’d agree that no specific emotion seems to emerge from the eyes alone.

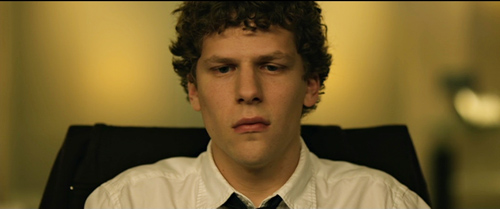

So what happens if we add eyebrows? (I’ve tipped the one above to conceal the brows; now you get to see the face’s proper angle.)

Now there’s a degree of surprise. The brows are lifted somewhat. But still the emotion seems fairly unspecific: not particularly sad or angry or distressed; probably not joyous either. Then what?

I’d call this dazed, slightly perplexed surprise. The sloping brows suggest the man is trying to figure out what’s happened; but the mouth is a slight gape. You can almost imagine the lips murmuring: “Ohhh,” or “Wow,” and not in appreciation or pleasure. If you wanted to show someone being blindsided, this is a pretty precise way to do it.

Of course context helps us a lot. Eduardo Savarin has just been gulled by his partner Mark Zuckerberg and by the interloper Sean Parker. His stock in the company that he co-founded is now worthless. So the situation informs our reading of Eduardo’s expression, and this permits the actor to underplay. Actor Andrew Garfield doesn’t give us bug-eyed surprise or frowning bafflement; he relies on our understanding of what he must be feeling (what we would feel) in order to refine and nuance his expression. When an actor underacts, we’re often expected to fill in the emotions we could plausibly imagine him to be feeling, on the basis of the story at this point. In isolation, the expression might be vague or ambiguous; the narrative situation helps sharpen it.

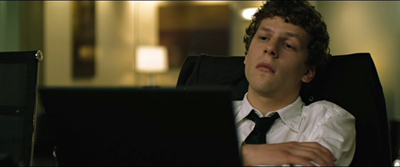

Back to the main question: How informative are the eyes alone? Try this one.

Again, I’ve tipped the shot a little to conceal the brows. Not much evident from the bare eyes, is there? Again, a certain focus and interest, but that’s about it. No marked surprise or fear or sadness.

Something has been added. The brows aren’t lifted in surprise or fear or sadness or distress; they seem to be relaxed. The angle of the look suggests concentration, but we’re not getting as much information as we got from Eduardo’s brows. We need a mouth.

The impression of concentration is greater, and I think we’d agree that this small smile of satisfaction gives us some insight into what the character is feeling. Again, the eyes tell only part of the story.

And again context matters. Mark Zuckerberg has just figured out that he can enhance The Facebook by adding users’ information about their romantic relationships. The tight, sidelong smile confirms not only his genius but also his view that college is partly about getting laid.

Less with the eyebrows

At this point you might be getting impatient with me. Isn’t this all obvious? Of course the actors use their faces–they’re paid to do that. But sometimes going obvious can get us to notice things.

For one thing, the eyes in themselves aren’t that emotionally informative. Pupil dilation can convey physical arousal, but that’s another story for another time. More commonly, the eyes give us the all-important information about what the person is looking at. The lids convey alertness, or drowsiness, or if they’re pinched a bit, concentration or anger.

Sometimes the eyes give us all the information we get. Here is Mark just before he agrees to take the job coding for the Winklevoss brothers’ project, The Harvard Connection. He moves from alertness to calculation by narrowing his eyes. As the phrase goes, you can hear the wheels turning.

Crucial to this moment is that nothing but Mark’s eyes and lids move; he doesn’t even turn his head. At the film’s climax, he will open up a little bit, and the eyelids play a central part. Getting the news that the Facebook party has been busted, Mark starts to breathe more laboriously, then wobbles his head slightly and closes his eyes. For once his concentration is broken.

It’s about as close as Mark comes to a canonical expression of sadness.

Obvious as it seems, by isolating the eyes we can notice the division of labor among eyes, eyelids, brows, and mouth: Each component supplies a bit of information. We’re remarkably skillful in integrating all these cues. What researchers into face perception call the informational triangle–the two eye regions tapering down to the mouth–creates a package of social and psychological signals. It’s this whole ensemble, the most informative parts of the face working together, that guides us in making sense of other people, or of film acting.

I’ve come to especially appreciate eyebrows. Daniel McNeill, in The Face: A Natural History, writes:

The eyebrow is the great supporting player of the face, and its work generally escapes notice. It helps signal anger, surprise, amusement, fear, helplessness, attention, and many other messages we grasp almost at once. Indeed, without eyebrows the surprise expression almost disappears. The eyebrows are such active little flagmen of mind-state it’s amazing anyone can wonder about their purpose. We use them incessantly (p. 199).

Since eyebrows are so important, actors must control them carefully. In the film’s first scene, Erica Albright moves her eyebrows vivaciously (and widens her eyelids too), but Mark’s brows are rigid and knit together.

This scene introduces us to Mark’s facial behavior. He will glance to the side when he’s pressed, but he’ll focus sharply on the other person when he’s trying to dominate the conversation. His mouth seems to be ruled by the triangularis and mentalis muscles, creating the inverted smile sometimes called the “facial shrug,” even when the lips are relaxed. Erica smiles a lot, something that usually triggers a responding smile. But not from this guy, though a smirk will occasionally flit over his mouth when he says something insulting. The closest we get to a true smile, I think, is at the blowout conclusion of the contest for internships, and that’s seen in the fairly distant long shot at the top of this section.

Above those eyes and that mouth sit those hooded brows, almost never lifting or lowering. Which is to say that Mark seldom shows surprise, and his anger will usually be visible in the set of his mouth (and in his words.) His flatlined brows sometimes suggest keen concentration, sometimes aloofness when he tilts his head back, or more pervasively the sense that everything in the vicinity is irritating. He seems to be permanently scowling, an effect that Fincher and DP Jeff Cronenweth accentuate by lighting that draws his brows closer together and hollows out the eye sockets.

How different this performance is from the actor Jesse Eisenberg’s everyday facial configuration (or at least the one he employs to send us other signals) can be seen in the making-of documentary accompanying The Social Network on DVD. One example surmounts this entry and shows a much different set of expressive cues–raised eyebrows, wider eyes, more cheerful mouth. The actor’s face is very mobile; he can even turn in the inner corners of his brows, which is hard to do voluntarily.

In one section of the making-of, Jesse reports that Fincher was often telling him, “Less with the eyebrows,” and onscreen Eisenberg delivered. By the end, for the last shots of Mark alone, Fincher asked for what’s become famous as the Queen Christina effect–an expression that could be read in many ways. “I want everybody to put anything on it.”

The result is a portrait of Generation Whatever, or an image of stoic loneliness, or of bemused curiosity about an old girlfriend, or. . . .

One more consequence of my noting the obvious: The centrality of faces to modern movies. Today’s films use close-ups very heavily, probably more than at any other point in film history. (The Way Hollywood Tells It explores some reasons why.) What I’ve called the “intensified continuity” style of modern cinema relies on tight single shots of individual players.

So modern players must be maestros of their facial muscles and eye movements. In other styles of filmmaking, currently and historically, the actor’s performance is projected onto more body parts through gestures, stance, gait, and the like. Recall Cary Grant, who performed with his whole body. Of course he wasn’t bad in close-ups either.

Faces aren’t everything in movies like The Social Network. Most characters use their arms and hands freely–probably the Winklevi the most. Mark is straightjacketed, but even he will gesture sometimes, as when a drooping Twizzler becomes his hand prop. He usually prefers a shrug, though it’s executed without the eyebrow lift most people add. Postures and personal walking styles play key roles in the film as well.

Still, as in most movies today, here eyes and brows and mouths are the main channels of emotional information. Fincher again: “It was really a movie about kids’ faces.” And even films from the 1910s, made before directors used a lot of cutting, often used long-shot staging to direct attention to the body’s most informative zones. A 1913 book on film acting noted, “Facial expression is perhaps the most important part of photoplaying. . . . After all is said and done the eyes are really the focus of one’s personality in photoplaying.”

Facebook facework

I can’t offer a complete account of nonverbal behavior in The Social Network here, but I want to end with a hypothesis that would be worth more detailed inquiry. The film’s central relationship is that between über-nerd Mark and Econ-major Eduardo, the coder and the aspiring tycoon (although he also supplies Mark with a crucial algorithm). Through facework, Fincher and his actors delineate the contrasting personalities and trace their shifting dynamic.

From the start, we get Mark’s stare of frowning concentration, drawing on the muscle called the corrugator, Darwin’s “muscle of difficulty.” By contrast, Andrew Garfield’s performance is marked by a look of worry and abashment. He’s often kinking his eyebrows, furrowing his brow, and ducking his head. Fincher motivates this behavior by having him often stoop over Mark’s workstation, tilt his head downward, and lift his eyes from underneath his brow.

In this shot/ reverse-shot passage, Mark’s mask never slips but Eduardo, wrinkling his brow and tipping his chin down a bit, looks apologetic.

Even when Eduardo has every right to berate Mark, he looks like he’s the one in the wrong. Instead of displaying the jammed-down, pinched-together brows of an angry man, he won’t lose his patient, slightly anxious look.

See the last image on this entry for a moment when Eduardo seems on the verge of tears–and this is after he’s gotten an invitation to join two alluring women.

You can argue that the blindsided expression we dissected earlier is one culmination of the facial cues that Andrew Garfield has been blending in the course of the film. But things are more complicated. The plot gives us two forward-moving timelines, one in the past tracing the rise of Facebook, the other in the present, during which Mark is deposed in two lawsuits. At an early deposition, Mark’s implacable stare works to make Eduardo revert to his old obeisance.

But in a climactic face-off, we come to see a different Eduardo.

Eduardo’s quiet testimony about whether anyone’s share but his was diluted (“It wasn’t”) affects Mark more deeply than the bluster of the Winklevoss brothers. The words are delivered without the usual sidelong glance, kinked eyebrows, or head ducking that has defined Eduardo earlier. His brow is smooth, his brows level. This is man to man, and it’s Mark who breaks off eye contact.

You could nuance this transformation by tracing it scene by scene, and contrasting it with the body language displayed by other characters. For today I simply wanted to sketch the broad development that I think is at work in this core relationship. The drama of domination and betrayal is played out in eyes, eyebrows, mouths, mutual gazes, and the like as much as it is in the dialogue and incidents.

There is no art, Shakespeare’s Duncan says, to read the mind’s construction in the face. He’s right about the reading part; we grasp expressions fast, intuitively, and often reliably. But there is art in the performer’s construction of the face, and of the director’s cinematic shaping of it.

John Ford’s remark about looking at the eyes is quoted in Joseph McBride’s Searching for John Ford (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010), p.2; the Warhol quotation comes from Andy Warhol and Pat Hackett, POPism: The Warhol ’60s (New York: Harper and Row, 1980), p. 109; quotations from David Fincher come from the bonus features on the collector’s edition DVD of The Social Network. My quotations about eyes in fiction are drawn from Leslie Charteris, Prelude for War (New York: Doubleday, Doran, 1938), pp. 171, 173. The 1913 quotation about eyes comes from Francis Agnew’s Motion Picture Acting (Syracuse: Reliance Newspaper Syndicate), p. 40; I learned of it from Janet Staiger’s article, “‘The Eyes Are Really the Focus’: Photoplay Acting and Film Form and Style,” Wide Angle 6, 4 (1985), pp. 14-23.

Ed Tan offers a very good analysis of the issues I mention here in his article “Three Views of Facial Expression and Its Understanding in the Cinema,” in Moving Image Theory: Ecological Considerations, ed. Joseph D. Anderson and Barbara Fisher Anderson (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005), pp. 107-127. I find Vicki Bruce and Andy Young’s In the Eye of the Beholder: The Science of Face Perception (Oxford University Press, 1998) a very helpful guide to ideas in this research area. The “facial shrug” is described in Gary Faigin’s excellent The Artist’s Complete Guide to Facial Expression (New York: Watson-Guptill, 1990), pp. 104-105.

There’s a fascinating debate in the human sciences about whether particular aspects of nonverbal communication are constant across cultures. Gestures vary considerably, but are facial expressions universal to some degree? Or do they differ from culture to culture? Are they primarily expressions of the person’s emotion, or are they signals which have developed, through evolution or cultural convention, to influence others? You can read more about these and other issues in Paul Ekman and Wallace V. Friesen, Unmasking the Face (Cambridge, MA: Maor Books, 2003) and Alan J. Fridlund, Human Facial Expression: An Evolutionary View (San Diego: Academic Press, 1994). The classic account is by Darwin, whose 1872 book Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals is available in an edition in which Ekman includes an afterword explaining the development of this research tradition.

Up to the minute, more or less: Contemporary research on smiling and eye contact.

PS 2 February: Thanks to William Flesch for correcting my Shakespeare citation: I originally attributed it to Hamlet.

PLANET HONG KONG: Starstruck

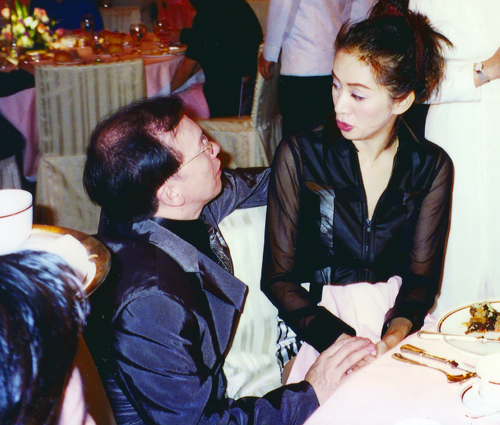

The late Anita Mui Yim-fong with Joe Junior. Hong Kong Film Awards party, April 1995.

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run daily entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have time or inclination to raise in the text. The first one, listing around 25 HK classics, is here. The second, a quick overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The third, on principles of HK action cinema, is here. The one following this considers western Hong Kong movie fans, the next entry focuses on directors, and the last entry reflects on film festivals, while adding a short list of some of my favorite HK movies. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D.

Today I want simply to share some photos I’ve taken of HK film performers over the last fifteen years. I’ll concentrate on the years B.B. (Before Blog)–that is, before 2007, when I began writing entries about my visits to the Hong Kong International Film Festival. Many other pictures of stars can be found in those annual entries, which can be accessed from this point on. I provide some links identifying the performers if you want to track down some films they were in. My snapshots’ quality isn’t professional–often my protagonists are bathed in tinted light–but for what it’s worth….

We reach back to the Analog Era, starting with my first visit to the Fragrant Harbour. Two couples at the 1995 Hong Kong Film Awards: Carina Lau Ka-ling and Tony Leung Chiu-wai; and Sandra Ng Kwun-yu and Simon Yam Tat-wah.

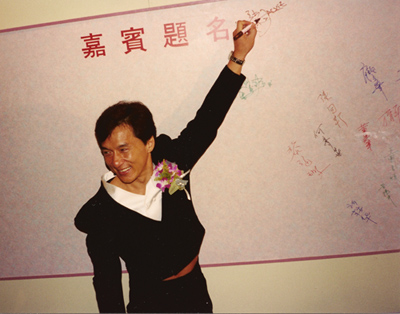

So on my first visit I was within viewing distance of two gods and two goddesses of Hong Kong film. Still, my most memorable moment came before the ceremony, when Jackie Chan came in and boldly wrote his name at the very top of the message board, above everybody else’s.

Two years later, when I was doing research for PHK, I met some performers in less public situations. This being Hong Kong, food was usually involved. Below, Francis Ng Chun-yu at a restaurant paused to promote his latest movie, Mad Stylist; and Shu Qi at Manfred Wong Man-chun’s fine restaurant.

Before you ask: Yes, I ate dinner with each of them. I was so dazzled I don’t remember a damn thing. Good thing I took pictures.

During the same 1997 visit, I managed to interview several filmmakers, one of whom was Anthony Wong Chau-sang. And what he said, I do remember. I took notes.

Alhough Anthony said it felt strange to be interviewed by a professor, he talked pretty freely. The interview ranged over acting styles (he was one of the few who experimented with the Method) and told some anecdotes about working with John Woo, Ringo Lam, and Kirk Wong. He also talked about his punkish rock music; who would think this gentle-looking guy was the lead performer on his classic “Let Thunder-God Gash All the Manic Bullies.”

One of the great things about Hong Kong is that stars from earlier eras are still treasured by younger moviegoers. I’ve seen Ti Lung, hero of many Shaw films of the 1970s and of the classic A Better Tomorrow (1986) several times, and he’s always surrounded by a swarm of young fans asking for his autograph. Here he is in a quieter moment at the 2001 Hong Kong Film Awards afterparty. Alongside is the ruggedly handsome Roy Cheung Yiu-yeung at the same event.

Earlier that evening at the Awards Michelle Yeoh was, as you’d expect, besieged by fans and news people.

Two from 2004: Jackie on the red carpet, more sedately dressed than before; and Eric Tsang Chi-wai.

Hong Kong Film Awards, 2006. An axiom of the 2000s Hong Kong cinema, Lam Suet; and Simon Yam again, this time with inveterate HK fan Mike Walsh.

Skipping ahead to 2008 and the premiere of Run Papa Run, here is the director, the ever-radiant Sylvia Chang Ai-chia, and one of her stars Louis Koo Tin-lok. I think of him as a newcomer, which he was when I was first visiting Hong Kong; but he has been in over sixty movies since 1994.

Also from 2008: Lau Ching-wan clowns in the kitchen of Paulina and Johnnie To Kei-fung, with Mrs. Lau (Amy Kwok) not at all put out. (More of Lau, from a few years earlier, here.)

One thing that struck me from my very first visit onward. Here stars are unbelievably approachable. Most enjoy meeting their fans, and they aren’t pretentious. This warmth adds to their lustre; glamorous as some stars are, they remain close to everyday people. As Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing put it, “In Hong Kong, once the audiences love you, they go on loving you for a very long time.”

The annual tribute to Leslie Cheung, held on the anniversary of his 2003 death; Mandarin Oriental Hotel, 2007.

Another Bologna briefing

More notes and notions from Cinema Ritrovato, all from DB:

Could you make a movie today about a farm girl who becomes a concert pianist under the sway of a womanizing egomaniac? The slightly nutty I’ve Always Loved You (1946) displays Frank Borzage’s usual faith in the way lovers communicate by spiritual ESP, this time aided by Rachmaninoff. Borzage talked the low-end Republic studio into this expensive project, and the result, though marred by strained performances, looks great in a glowing restoration by UCLA. A teenage André Previn darts through, and for once someone playing the piano onscreen (in this case Catherine McCloud) looks skillful. (The playback renditions were those of Arthur Rubinstein, credited as “the world’s greatest pianist.”) The title is perfectly ambiguous, since it could refer to any character’s attitude toward almost any other.

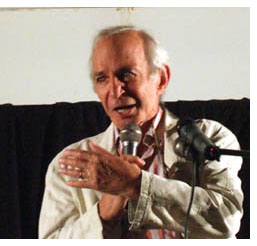

Travel delays prevented Ben Gazzara from introducing the fine print of Anatomy of a Murder. Too bad. It would be fascinating to hear how he developed his disturbing portrayal of an accused killer under Preminger’s notoriously dictatorial direction. But Gazzara did participate in an interview with Peter von Bagh that led into a screening of a beautiful restoration of Jack Garfein’s The Strange One (aka End as a Man).

Gazzara talked of coming out of the Actors Studio after the success of Marlon Brando, a tremendous influence on Gazzara’s generation. He recalled that he was in the same Studio class as James Dean, Steve McQueen, and Paul Newman. What was the Method? “It’s a word I never use. I don’t know what it means. . . It gave you things to fall back on” if you couldn’t come to grips with the script material.

Gazzara talked of coming out of the Actors Studio after the success of Marlon Brando, a tremendous influence on Gazzara’s generation. He recalled that he was in the same Studio class as James Dean, Steve McQueen, and Paul Newman. What was the Method? “It’s a word I never use. I don’t know what it means. . . It gave you things to fall back on” if you couldn’t come to grips with the script material.

He said that he loved Hollywood acting of the studio era: Gable, Grant, Tracy, and Stewart remain fresh and modern. When he saw Meet John Doe, he realized that Gary Cooper used his own version of the Method: “He did very little, but he did everything.”

Gazzara said that seeing Faces (1968) drew him to Cassavetes. “I was mesmerized. I was so jealous. I thought, I’ve gotta work with this man.” A year later he made Husbands. Cassavetes was very supportive, always “waiting for surprises.” He was laughing in enjoyment behind the camera, encouraging his players. “All you did was safe, and you could do no wrong.”

The Strange One, set in a Southern military academy, was Gazzara’s first film. He was offered the part of the cadet who eventually leads a revolt against the Machiavellian cadet Jocko De Paris. But Gazzara said that he wanted to play DeParis because “he got all the laughs.” George Peppard wound up with the good guy role. Though the film seems to me confused on several dimensions, Gazzara revels in the showy part of a soft-spoken, eminently reasonable sociopath. As in Anatomy of a Murder, he makes gently menacing use of a cigarette holder.

In the early 1930s, Japanese companies explored the possibility of exporting their films to Europe and the US. One result of these initiatives was Nippon: Liebe und Leidenschaft in Japan, a 1932 German compilation created by Carl Koch. It originally consisted of three films from the Shochiku studio, condensed and supplied with German intertitles. The original films were silent, so, oddly enough, synced Japanese dialogue was added.

In the version screened here, only two episodes were presented. What beauties they were! Since many of the 1920s and 1930s Japanese films that survive look quite weatherbeaten, it was wonderful to see, in the print from the Cinémathèque Suisse, how gorgeous quite ordinary movies from this era could be.

The first story, Kaito samimaro (orig. 1928), deals with a young samurai rescuing his beloved from the clutches of a corrupt priest. Brisk and beautifully shot, it came to the sort of frothing swordplay climax typical of the period—rapid cutting, dynamic tracking, and slashing assaults aimed at the camera. Kagaribi (1928), about a young vassal betrayed by his corrupt lord, likewise ended with a protracted action scene capped by a jolting climax. A prolonged tracking shot follows the young man’s former lover as she backs away from him, but then we cut to a full shot. With a single stroke he kills her, jaggedly ripping a paper door in his follow-through. Both stand motionless for a moment before she falls. A conventional finish, but no less eye-smiting for that. For more on the power of this action-cinema tradition, see an earlier entry on this site.

There are no fewer than ten flashbacks in the 1950 Swedish film Flicka och Hyacinter (Girl with the Hyacinths, above). Peter von Bagh’s Bologna programming has often highlighted Nordic work that’s little known outside the region, such as this engrossing post-Kane exercise in probing a dead person’s life. Teasingly directed by Hasse Ekman, the interlocking flashbacks would be savored by today’s puzzle-film aficionados, and the movie’s equivalent of Rosebud is genuinely surprising. The twist would never have been permitted in Hollywood of that era.

Kristin and I hope to post one more entry, probably soon after Ritrovato’s final session on Saturday. Lots more to report–Lubitsch, Borzage, Chaplin (of course), etc. For now, a glimpse of the official names of the Cineteca’s two screening rooms…

Charlie, meet Kentaro

DB here:

Echoing an earlier virtual roundtable on this blog, I want to write about my two favorite B film series, now available in handsome DVD boxed sets. Both series were mounted at 20th Century-Fox, both were adapted from genre fiction, and both seem very much of their time: lots of exotic Orientalia, and probably too many middle-aged men in tiny mustaches and broad fedoras. But to my mind these films offer brisk, unpretentious entertainment, solidly crafted and surprisingly subtle. They also allow us to trace some changes in the ways movies were made across the 1930s.

There’s another reason for this blog. Tim Onosko, a friend of Kristin’s and mine, recently died after a battle with pancreatic cancer. Tim was an extraordinary figure, as you can find here. He was central to Madison film culture for forty years, and in his various creative activities, he shaped everything from The Velvet Light Trap to Tokyo Disneyland. He and his wife Beth also made a documentary, Lost Vegas: The Lounge Era. Tim and I enjoyed talking about the two series I’ll be mentioning. He loved these films, as he loved all films and popular culture generally, with a sharp-eyed dedication. So this is a small effort at an homage to Tim.

The Hawaiian and the Japanese

Charlie Chan, a Hawaiian police inspector of Chinese ancestry, became famous in a series of six novels by Earl Derr Biggers, from The House without a Key (1925) to The Keeper of the Keys (1932). Chan novels were brought to the screen at the end of the 1920s by Pathé and Universal, but for Behind That Curtain (1929) Fox took over the franchise. Warner Oland, a Swedish-born actor who had often played Asians, settled into the lead role in Charlie Chan Carries On (1931). He played Chan up through Charlie Chan at Monte Carlo (1937), then fled Hollywood under peculiar circumstances and went to Sweden, where he died soon afterward.

The Mr. Moto films overlapped with the Oland cycle. John P. Marquand introduced Moto in the novel No Hero (1935) and made him more central to four novels that followed. Again, Fox bought the rights and launched the film series with Thank You, Mr. Moto (1937). It starred Peter Lorre as the mysterious Japanese, and I think it’s fair to say that the role made him a Hollywood star. The series ran for eight installments, ending in 1939 with Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation.

The Mr. Moto films overlapped with the Oland cycle. John P. Marquand introduced Moto in the novel No Hero (1935) and made him more central to four novels that followed. Again, Fox bought the rights and launched the film series with Thank You, Mr. Moto (1937). It starred Peter Lorre as the mysterious Japanese, and I think it’s fair to say that the role made him a Hollywood star. The series ran for eight installments, ending in 1939 with Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation.

Each series echoed its mate. Tim claimed that in an early Chan, a character is reading a Moto story in the Saturday Evening Post, though I’ve never found that scene. When Charlie’s Number One Son turns up to help Moto in Mr. Moto’s Gamble (1938) it’s revealed that Charlie and Moto are old friends. There’s a more elegiac moment in Mr. Moto’s Last Warning (1939) when a theatre displays a poster for the Chan series—perhaps as well serving as an homage to the recently deceased Warner Oland. Despite Oland’s death, the Chan series continued until 1949, with Sidney Toler in the role, but with Lorre’s departure the Moto films ceased.

Having a Caucasian actor play an Asian protagonist was common at the time. Today, it seems condescending or worse, but we should recognize that the films featured Asian actors as well, often in significant roles. The most visible example is Keye Luke as Charlie’s highly Americanized son. Forever blurting out “Gosh, Pop!” Luke is a lively and likable presence.

Just as important, the portrayal of the detectives is remarkably free of racism. Charlie and Moto are clearly the quickest-witted characters, and both prove resourceful in all kinds of ways. Moto’s judo subdues thugs twice his size, and Charlie is up-to-date in the new technologies of detection.

The scripts go out of their way to show both men skilfully handling the prejudice they encounter. In Charlie Chan at the Opera (1936), a blatantly racist cop (William Demarest) who calls Charlie “Chop Suey” is mocked incessantly by everyone, most gently by Charlie. Moto excels at pretending to be the stereotypical Asian (“Ah, so!” “Suiting you?”). And both our protagonists are sympathetic to others who are in minorities. Charlie is notably unwilling to participate in guying black servants as the whites do, and Charlie Chan at the Circus (1936) shows his keen sympathy with the “freaks,” treating them with quiet courtesy. The Moto series presents a Japanese who doesn’t seem to share his country’s goal of ruling Asia. In Thank You, Mr. Moto, he enjoys a respectful friendship with a Chinese family of declining fortunes.

The Chan series features straightforward detection. A murder is committed, and either Charlie is in the vicinity or the police ask for his help. A young and innocent couple is involved, adding pressure for Charlie to solve the case. Another murder is likely to take place, and a few attempts are made on Charlie’s life before he comes to the solution. In traditional fashion he tends to assemble all the suspects at the climax before exposing the guilty party.

The Chan series features straightforward detection. A murder is committed, and either Charlie is in the vicinity or the police ask for his help. A young and innocent couple is involved, adding pressure for Charlie to solve the case. Another murder is likely to take place, and a few attempts are made on Charlie’s life before he comes to the solution. In traditional fashion he tends to assemble all the suspects at the climax before exposing the guilty party.

The Moto films aren’t as concerned with puzzles. Like the novels, they’re tales of international intrigue, involving smuggling, theft of archaeological treasures, and the like. There’s more violence and physical action, with shootouts and last-minute rescues. Moto Kentaro (his given name is visible only on his identity card) is a more shadowy presence than Charlie, often working under vague auspices. He’s either an agent of Interpol, a functionary of the Japanese government, or an exporter who takes up intrigue as a hobby. (1) In Mr. Moto’s Gamble, arguably the best of the series, he engages in old-fashioned detection involving murder during a boxing match. Unsurprisingly, the film was originally planned as a Chan vehicle, and it even includes Number One Son as Moto’s sidekick.

The Moto films aren’t as concerned with puzzles. Like the novels, they’re tales of international intrigue, involving smuggling, theft of archaeological treasures, and the like. There’s more violence and physical action, with shootouts and last-minute rescues. Moto Kentaro (his given name is visible only on his identity card) is a more shadowy presence than Charlie, often working under vague auspices. He’s either an agent of Interpol, a functionary of the Japanese government, or an exporter who takes up intrigue as a hobby. (1) In Mr. Moto’s Gamble, arguably the best of the series, he engages in old-fashioned detection involving murder during a boxing match. Unsurprisingly, the film was originally planned as a Chan vehicle, and it even includes Number One Son as Moto’s sidekick.

Looks and looking

We can learn a lot by studying the two main actors’ performance styles. The plump Oland plays Chan as stolid but not ponderous. He floats across a room and gravely circulates among suspects, giving the films their deliberate pacing. Oland’s drawn-out delivery and pauses were due, people say, to his acute alcoholism, but he never seems to be struggling to find his lines. Charlie is at pains to be unobtrusive, modest, and tactful; his characteristic gesture is a simple one, letting the fingertips of one hand grasp one finger of the other.

He is a loving father, doting on his many children (all in tow in Charlie Chan at the Circus). Although Number One Son may exasperate him, you would go far in films to find as warm a portrayal of a father’s affectionate efforts to curb an impulsive boy. See Charlie Chan at the Olympics (1937) for the casual byplay between Charlie and Lee, now an art major and a member of the swimming team. Lee’s bubbling energy gives Charlie’s imperturbability even greater gravitas.

The short and slim Lorre plays Moto as a suave man-about-Asia, hand thrust casually into his trouser pocket. Moto is an art connoisseur, a graduate of Stanford (class of ‘21), and a master of many languages. Lorre, so easily caricatured at the time and now, hit on a brilliant idea: He didn’t give Moto stereotyped tricks of pronunciation. Unlike Oland, he didn’t usually drop articles or compress syntax.(2) Lorre just played the part in his lightly accented English, as he would in The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca. He added a soft-spoken delivery, a modest smile, and a trick he may have picked up from Marlene Dietrich–ending his sentences with a slight upward inflection, turning every statement into a polite question.

Reaction shots of suspects are a convention of these movies, but after several cuts show us everybody looking shifty, the reverse shots of our heroes show us that they miss none of this byplay. (3) Charlie is alert, but he hides his penetrating view behind a bland courtesy. As Moto, Lorre presents a more aggressive intelligence. Peering through round spectacles, those bug eyes, panic-stricken in M, can now become pensive or bore into a suspect. Charlie needs the force of law, but Moto, who usually acts alone, is dangerous by himself, and Lorre’s horror-show pedigree serves him well in giving his hero’s stare a sinister edge.

Listening and looking

You can argue that Oland and Lorre, coming to their parts only a few years after sound had arrived, helped Hollywood develop a wider array of acting styles. We historians of Hollywood have rightly praised gabby comedies like Twentieth Century (1934) and It Happened One Night (1934) for finding a performance technique suited to sound films, particularly in the wake of technical improvements in acoustic recording. If movies had to talk, we think, they should really talk, fast and hard and heedlessly. In this church our Book of Revelations is His Girl Friday (1940).

Lorre and Oland, like Karloff and Lugosi, remind us of the virtues of being gentle, spacious, and deliberate. This isn’t a reversion to those hesitant, strangled mumblings of the earliest talkies. Rather, the movies’ plots surround our Asians with rapid-fire duels of cops and reporters, snapping out “Say!” and “Hiya, sister!” and “Watch it, wise guy!” and “Don’t be a sap!” Against clattering percussion Moto and Charlie deliver a melodic purr.

Some people still believe that in Citizen Kane Welles and Gregg Toland introduced American film to steep low angles, tight depth compositions, and noirish lighting. In The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I’ve argued that the Gothic, somewhat cartoonish look of Kane synthesized and amplified trends that were emerging during the 1930s. The Chan and Moto films are wonderful places to study these visual schemas.

E

E

In Charlie Chan in Egypt (1935, above), cinematographer Charles G. Clarke (whom Kristin and I interviewed for the Hollywood book) offers flashy depth and silhouette effects, and nearly all the Chan films have moments of clever staging. Charlie Chan at the Opera, above, is particularly engrossing, with its huge set (recycled from the A-picture Café Metropole, 1937). The same film, incidentally, contains scenes of a fictitious opera, Carnival, composed by Oscar Levant. This was an ambitious gesture for a B film and looks forward to Bernard Herrman’s Salammbo sequences of Kane.

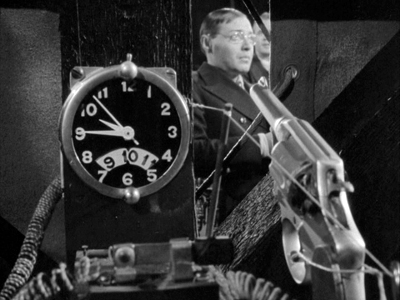

The Motos are even more remarkable. You want wild angles? Venetian-blind shadows? Telltale reflections in eyeglasses? Swishing bead curtains? Twisted expressionist décor? You’ve come to the right place.

Some late thirties Fox sets seem to have been stored in Caligari’s Cabinet. Watching these films, it becomes clear that Kane applied the moody technique of crime and horror films to ambitious drama. One bold setup in Mr. Moto’s Gamble looks like a dry run for a Toland big-foreground composition (done here, as often in Kane, through special-effects). I like this shot so much I used it in Figures Traced in Light.

Yet all this creativity took place within severe constaints. These were B pictures, running under seventy minutes and shot in a month or so. Three or four would be released each year. They shamelessly used stock footage, leftover sets, and the same players in different roles from film to film. (Watch for Ray Milland, Ward Bond, and others on the way up.) The boys in the Fox cutting room seem to have enforced a remarkable uniformity: most of the Chans in these DVD sets, regardless of director, contain between 600 and 660 shots, while the faster-paced Motos average between four and six seconds per shot. The actors created hurdles too. Oland sank even further into drinking while the high-strung Lorre was addicted to morphine and periodically retired to sanitariums to recover. Those were the days; rehab wasn’t yet a matter for infotainment.

The Fox DVD boxes are model releases. The prints are well-restored (better on the second sets than the first) and filled with astute, informative supplements. We get a lot of detail about production matters, including why Oland left Hollywood. There is welcome biographical background on master minds like Sol Wurtzel and Norman Foster. I still want to know more about James Tinling, though; his direction of Mr. Moto’s Gamble and Charlie Chan in Shanghai (1935) belies his reputation as a hack.

“The cinema is not dangerous,” Moto reassures the Siamese tribesmen about to be filmed in Mr. Moto Takes a Chance (1938). Immediately, the woman who’s being filmed dies. The adventure begins. Who can resist movies like these? They have kept me happy since my childhood, when I watched them on Sunday afternoon TV. They can keep your children, and you, happy too.

For some good reading, see John Tuska, The Detective in Hollywood (Doubleday, 1978); Charles Mitchell, A Guide to Charlie Chan Films (Greenwood, 1999); Howard M. Berlin, The Complete Mr. Moto Film Phile: A Casebook (Wildside, 2005); and Stephen Youngkin, The Lost One: A Life of Peter Lorre (University Press of Kentucky, 2005).

For more on Charlie, click here. Charles Mitchell has a nice wrapup on Kentaro here.

(1) The involvement of an innocent romantic couple was a convention of slick-magazine fiction of the day (both the Chan and Moto novels were serialized in the Saturday Evening Post), and it recurs throughout mainstream detective fiction of the 1930s. Most writers of the period wrestled with the problem of how to make the couple interesting. See Carter Dickson/ John Dickson Carr’s short story, “The House in Goblin Wood,” for a brilliant handling of the device.

(2) As many commentators have noted, Charlie doesn’t speak pidgin English; he seems to be mentally translating. Interestingly, the generation gap is apparent here too, since Number One Son speaks peppy and perfect American slang.

(3) One hyperclever moment in Mr. Moto’s Gamble gives us the usual rapid-fire array of single shots of discomfited suspects but neglects to show us the real culprit.