Archive for the 'Silent film' Category

Albatros soars

Gribiche (1925).

Kristin here:

Lazare Meerson was one of the great set designers of the late silent period and into the 1930s. His name may not immediately ring a bell, but he designed the great French films of René Clair (La Proie du vent, An Italian Straw Hat, Les deux timides, Sous les toits de Paris, Le Million, À nous la liberté, and La Quatorze Juilliet) and Jacques Feyder (Gribiche [above], Carmen, Les Nouveaux Messieurs, Le Grand Jeu, Pensions Mimosas, and La Kermesse héroïque). He crossed paths with most of the major French Impressionist directors, sometimes in their post-Impressionist periods: Marcel L’Herbier (Feu Mathias Pascal, his masterpiece L’Argent, Le Mystère de la chambre jaune, and Le parfum de la dame en soi), Jean Epstein ( Les Aventures de Robert Macaire), and Abel Gance (Le fin du monde and Poliche). His credits include work with such French directors as Maurice Tourneur, Julien Duvivier, and Claude Autant-Lara.

Meerson was born in Russia and fled the Revolution. Making his way via Germany to Paris, he became the assistant to set designer Alberto Cavalcanti on Feu Mathias Pascal. That’s one of the five French films on a new Flicker Alley release, “From Moscow to Montreuil: The Russian Émigrés in Paris: 1920-1929.” Meerson’s illustrious career led him to England in the second half of the 1930s, where he designed several notable films, including Paul Czinner’s As You Like It, Clair’s Break the News, and Feyder’s Knight without Armour, as well as the classic The Scarlet Pimpernel. He died in 1938 at the young age of 38. (The best online source on Meerson is R. F. Cousins’ filmography, bibliography, and brief biography.) His influence lives on in the work of his most prominent student, Alexandre Trauner (Le jour se lève, among many others).

I begin with Meerson in order to stress how many important strands of film history come together in this very ambitious Flicker Alley set. It allows us to trace Meerson’s early years, from his first apprentice work, Feu Mathias Pascal, to his first and third projects for Feyder. That in itself would be enough to make this release notable, but the Albatros film studio in Paris during the 1920s hosted an amazing collection of talented people working in the cutting-edge styles of the era.

Here we also find three films starring the extraordinary Russian star Ivan Mosjoukine, known to most audiences by reputation only, and then only for the ephemeral Kuleshov experiment that used footage from an old film with Mosjoukine.  This experiment is not known to survive. In it a close view his impassive face reputedly was edited together with shots of a dead woman, a bowl of soup, a small child, or perhaps other subjects, depending on which report you read. Spectators supposedly credited Mosjoukine with a marvelous performance, based on eyeline editing rather than any changes in his expression. We shall probably never know the exact form this experiment took and who saw it. I have to believe that the shots of Mosjoukine were inserted at wide intervals in a feature film, not strung together one right after the other, as makers of modern “reconstructions” of the experiment seem to assume. It’s much more interesting to watch Mosjoukine in the three very different performances presented here: Le Brasier Ardent, Kean, and Feu Mathias Pascal. His face is anything but impassive

This experiment is not known to survive. In it a close view his impassive face reputedly was edited together with shots of a dead woman, a bowl of soup, a small child, or perhaps other subjects, depending on which report you read. Spectators supposedly credited Mosjoukine with a marvelous performance, based on eyeline editing rather than any changes in his expression. We shall probably never know the exact form this experiment took and who saw it. I have to believe that the shots of Mosjoukine were inserted at wide intervals in a feature film, not strung together one right after the other, as makers of modern “reconstructions” of the experiment seem to assume. It’s much more interesting to watch Mosjoukine in the three very different performances presented here: Le Brasier Ardent, Kean, and Feu Mathias Pascal. His face is anything but impassive

We can also appreciate Belgian-born director Jacques Feyder, who had begun his feature-film career with L’Atlantide (1921) and Crainquebille (on our 10-best list for 1922) and then suffered a box-office disappointment with the charming, poignant Visages d’enfants, making two notable films for Albatros. Gribiche contains the first performance by Françoise Rosay, Feyder’s wife, who became one of the grandes dames of French cinema.

Most of all, however, this set makes a big step in showing us what happened after the Revolution to the most important Russian production company, that of Josef Ermolieff. The founder, as Lenny Borger points out in the highly informative booklet accompanying the set, had French connections from the start. Ermolieff “begin his career as a technical assistant at Pathé’s Moscow branch, and by 1912 had moved up through the ranks to become Pathé’s sales agent in Russia. On the verge of the war, he founded his own company and studio and gathered around him a core of artists and technicians who later would become the Russian film colony of Paris.”

The Russian work of the Ermolieff company was revealed to modern audiences in the groundbreaking retrospective of pre-Revolutionary Russian cinema presented at the La Giornate del Cinema Muto festival in Pordenone, Italy in 1989. The flood of hitherto unknown films included great melodramas starring Mosjoukine and other wonderful actors who made their way to Paris in the wake of the Revolution.

Ermolieff initially took his company to Yalta, where in 1918-19, they made several films. The next stop was Constantinople, and finally Paris via Marseilles. Ermolieff purchased the old Pathé studio in Montreuil-sous-Bois and set up filmmaking. The first film entirely produced there, Yakob Protazanov’s L’Angoissante aventure (1920) is not included in the Flicker Alley set. It does survive, however. I remember it as an entertaining film with the added attraction of having a story built around filmmaking. Perhaps someday that, too, can be made available on DVD. In the meantime, the five films in the set show the Russian emigrés gradually merging with the French filmmaking establishment of the day and supporting the work of some of the important Impressionist filmmakers.

Ermolieff himself decided to set up shop in Germany, selling the studio to two of his colleagues, Alexandre Kamenka and Noë Bloch. Renaming the firm Les Film Albatros, they brought it into the mainstream of French cinema.

Le brasier ardent (1923)

Mosjoukine directed two films, of which this is the second. It has a reputation as an audacious, surrealist, and almost incomprehensible film. This may be due to the fact that prints available in archives during the 1970s and 1980s lacked intertitles. The opening nightmare sequence is indeed disturbing, but at least with intertitles, we understand that it is only a dream. It begins with a wild-eyed man tied to a stake where he is about to be burned. The heroine stands looking on, resisting as the man pulls on her long hair, apparently intent on dragging her into the fatal flames to accompany him in death. Subsequent scenes of the nightmare show the heroine encountering different men, all played by Mosjoukine, culminating in a man in evening dress stalking her along a vaguely Expressionist street until she escapes and wakes up in bed.

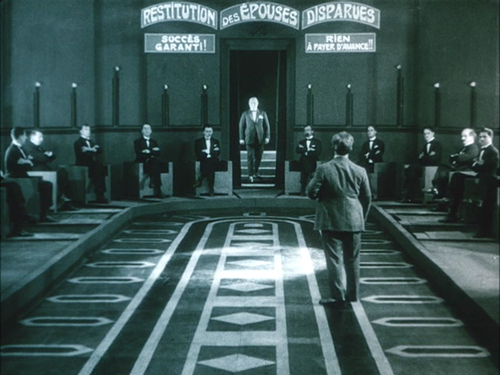

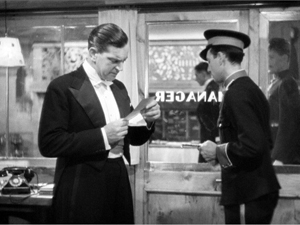

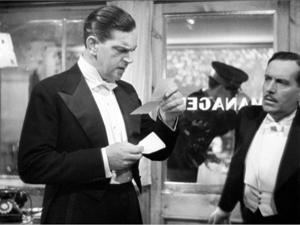

This nightmarish opening must have established vivid expectations in the spectators of 1923 as to what sort of film they were in for. After the heroine wakes up, however, what follows is quite different. The main plot is a stylized but quite amusing comedy. The heroine is a pampered wife, married to a rich man whom she does not love. She is faithful, but he is unreasonably jealous. He goes to a distinctly odd detective agency, one department of which is “Recovery of Lost Wives” (above), with “Success guaranteed!” and “Nothing to pay in advance!” Juxtaposed with the bizarre opening, this quirky humor might have eluded puzzled audiences of the day. Certainly the film itself was a failure, and Mosjoukine stuck to acting thereafter.

Unfortunately for the husband, Detective Z, whom he picks from the eccentric group pictured above, is the very man, again played by Mosjoukine, whom his wife has dreamed about. What follows is an odd tale with the detective and wife gradually falling love. Mosjoukine, known for his tragic, intense characters in the Russian cinema, plays such figures in the fantasy sequences–but in the main story he is allowed to play for laughs, gamboling and rolling on the floor like a puppy when the wife finally appears at his mother’s apartment and declares her love for him.

Mosjoukine should not, however, be allowed to overshadow his co-stars, Ermolieff actors who were also were to make their way into the wider French production of the day, including Impressionism. The wife is played by Nathalie Lissenko, one of the stars of the pre-Revolutionary cinema, who had acted opposite Mosjoukine in Russia. Among her 1920s roles was the protagonist of one of Epstein’s finest films, the largely unknown L’Affiche (1924). The husband is Nicolas Koline, who started his career with Ermolieff only after the company had left the Soviet Union. He will be familiar to silent-film fans from his performance as Tristan Fleury in Gance’s Napoléon.

Kean (1923)

Le Brasier ardent has definite touches of the Impressionist style, but Alexandre Volkoff’s big-budget biopic Kean went further in that direction. I have to admit that it’s not one of my favorite Albatros films. Borger points out that, although it was a prestige picture in its day and quite successful, it has not worn well. The fault in part may lay in the source material, a play co-authored by Alexandre Dumas. Still, the film is notable for Mosjoukine’s anguished performance as the great Shakespearean actor. It also contains one of the most famous sequences of the Impressionist movement, where Kean gets drunk and dances frantically. Borger describes it: “The increasingly frenzied cutting that translate his state of mind was not there by chance: since the trade screenings of Abel Gance’s La Roue [also released by Flicker Alley] a few months prior to the shooting of Kean, rapid-cutting had become all the rage in French films–look at some of the major commercial pictures produced after La Roue’s release and you will find at least one obligatory explosion of rapid editing. But Volkoff was Gance’s best imitator.”

Feu Mathias Pascal (1925)

To quote myself from an article in the issue of Griffithiana devoted to the 1989 Pordenone retrospective:

These two films abruptly brought the Albatros group to the attention of the Impressionist directors and to supporters of the French avant-garde cinema. After having virtually ignored the Russian emigrés to this date, Cinéa published a long article on Le Brasier ardent and an interview with Mosjoukine; Kean received similar attention, and articles in Cinéa-Ciné pour tous and Cinémagazine appeared reguarly thereafter. After this point, Mosjoukine starred in films by the French Impressionists as well as those by emigré directors: Le Lion des Mogols, for Epstein, Feu Mathias Pascal, for L’Herbier, and, nearly, in Napoléon, for Gance.

For decades Feu Mathias Pascal was the most familiar of L’Herbier’s films, at least in the USA, where an abridged version was part of the Museum of Modern Art’s circulating 16mm collection. By now his L’Argent (1928) has probably eclipsed the earlier film’s reputation, at least in the eyes of critics, historians, and silent-film enthusiasts. Feu Mathias Pascal is a more approachable film, though, and would be a good choice for teaching French Impressionism.

Adapted from a novel by Pirandello, it stars Mosjoukine as a character described at the outset: “From childhood Mathias Pascal, a tormented dreamer, has cherished a fantastic hope to free himself to become his own Master!” This paves the way for the many dreams, visions, and heightened emotional states that will be conveyed by the superimpositions, selective focus, camera movements, and fast cutting beloved of the Impressionists.

Pascal finds himself in exactly the sort of situation he hates: tormented by his overbearing mother-in-law and by a wife too weak to side with him against her. His mother and infant daughter both die, and grief-stricken, he flees. A large win at a casino and a mistaken identification of the body of a suicide as Pascal lead him to seize the opportunity to begins a new life.

Mosjoukine left Albatros after this film, pursuing his stardom in big-budget exotic historical films and melodramas, including work in Hollywood and Germany, before his death in 1939 at the age of 49. This was also Michel Simon’s first significant film; he appears in an important supporting role.

Gribiche (1925)

Gribiche is a charming film built around the talents of the boy actor Jean Forest, whom Feyder had discovered for a small role in Crainquebille.

He plays Antoine, nicknamed “Gribiche,” the son of a war widow who struggles to support him and keep him in school. As the film opens, Gribiche returns the dropped purse of a rich woman, Mme. Maranet (Françoise Rosay), and refuses the proffered reward. Maranet, having a scientific interest in children’s welfare, on a whim offers to adopt him. Knowing that his mother is being courted by Philippe Gavary, whom she hopes to marry, Gribiche pretends to want the private education promised by Maranet, and off he goes to live in her modern mansion (Meerson’s design, see top). There he is raised by servants and tutors to a strict schedule, with no time allowed for play. Meanwhile, his mother becomes engaged to her suitor.

The story contains some implausibilities. During a fairground outing with his mother and Gavary (above), Gribiche overhears the two discussing a possible marriage, but both seem worried about Gribiche. There is a hint that the man won’t propose if he has to take on a stepson. This scene motivates the whole chain of affairs. Yet Gavary seems to like the boy, and when Gribiche gets fed up with his sterile life with Maranet and runs away, Gavary is concerned and willing to take him in with no hint of discord between him and the mother. Still, the story on the whole is carried by Forest’s ability to play for both humor and pathos, the beautiful Meerson settings, and the comic business with the tutors and servants. Rosay remarkably creates a character who is friendly and sympathetic yet lacks the deeper warmth that would allow her to raise a child.

For those not familiar with Feyder’s early work, this and the next item are musts. His three most important earlier films are available on DVD, so much of the director’s silent career, previously little known, is now accessible.

Les Nouveaux Messieurs (1928)

This is a Feyder work well worth getting to know. Moving beyond his films based on stories of innocents oppressed (Crainquebille, Visages d’enfants, and Gribiche), Feyder made an adaptation of Carmen (1926) that is competent but not exciting and Thérèse Raquin (1928), which to the best of my knowledge does not survive.

Les Nouveaux Messieurs was an adaptation of a different kind, one which Borger quite rightly compares to René Clair’s late silent comedies. Taken from a popular play of the 1925-26 season, it is a satirical comedy about Jacques Gaillac, an electrician who runs for public office and briefly ends up as labor minister in a leftist government. Along the way he courts Suzanne, a ballerina who is the mistress of the wealthy Count of Montoire-Grandpré. The Count is an older man who is patiently resigned to fighting off her occasional suitors, and we see him pulling political strings on the sly.

Once again Feyder displays his talent for casting actors who can build sympathy for characters who would normally register as unpleasant. Gaby Morlay makes the mercenary ballerina appealing, someone we can believe the naïve electrician would fall in love with. Veteran actor Henri Roussell is remarkable as the Count, eschewing the obvious tropes of anger and jealousy. He is instead smart, amusing, and clearly so devoted to Suzanne that we half hope she will go back to him. The film again has Meerson settings and displays Feyder’s eye for striking visuals, both on location (above) and in the studio (below).

I recently mentioned in my discussion of Blancenieves that it was an excellent imitation of a European film made in 1928 or 1929. Les Nouveaux Messieurs is a good example of the kind of film it’s modeled on.

Coming up

Flicker Alley recently revealed that it has three releases nominated for awards in Il Cinema Ritrovato’s annual DVD awards for 2013, winners to be announced at the festival this year. Oddly, I can’t find a list of all the nominees online. When it appears, I’ll add it. The Flicker Alley nominees are: Nanook of the North/The Wedding of Palo, Feu Mathias Pascal, and “From Moscow to Montreuil.” Congratulations!

Now, if Flicker Alley will manage to release its long-rumored project, Albatros’s 1923 serial, La Maison du mystère, starring Mosjoukine, we will all be doubly grateful. For a bit of information on that and a great deal of information on various film-preservation topics, see this interview with David Shepherd, preservation expert and co-producer with Jeffery Masino of “From Moscow to Montreuil.” Nitrateville has posted a shorter interview with Shepherd, but one devoted entirely to the Albatros release.

Finally, readers who use Facebook should consider Liking Flicker Alley’s page. It lists public screenings of silent films, sponsored by itself and others alike, as well as other silent-film-related news and information about Flicker Alley releases.

The most comprehensive publication on Albatros is François Albera’s Albatros: des Russes à Paris 1919-1929 (Paris: Cinémathèque française, 1995), which contains numerous designs and on-set production photos.

My article is “The Ermolieff Group in Paris: Exile, Impressionism, Internationalism,” Griffithiana 35/36 (October 1989), pp. 50-57. (The quotation is from pages 52-53.) Lenny Borger’s “From Moscow to Montreuil: the Russian Emigrés in Paris 1920-1929,” appears in the same issue, pages 28-39, including a filmography.

Flicker Alley recently released Feu Mathias Pascal separately in a Blu-ray version.

Les Nouveaux Messieurs (1928).

Silent films, old and new

Blancanieves

Kristin here:

February and March have been good to silent cinema. Time for a round-up of some highlights as we impatiently anticipate Il Cinema Ritrovato, coming up in a little over two months.

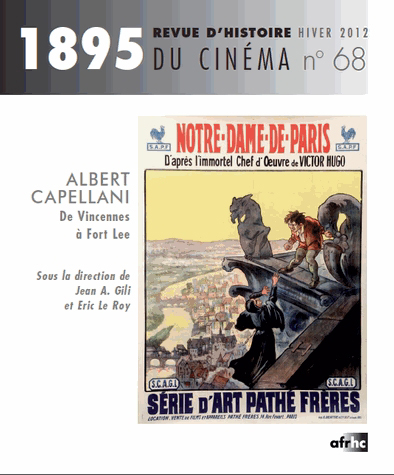

Publications on Albert Capellani

In reporting on the 2010 and 2011 programs of Il Cinema Ritrovato, I highlighted one of the festival’s major revelations, that of the silent films of Albert Capellani. These generous doses of Capellani’s splendid films were put together by Mariann Lewinsky, who realized his importance after she included some of his shorts in her annual “Cento Anni Fa” programs. In my entries I argued that Capellani was revealed as one of the early cinema’s great masters. (The 2010 entry is here, and the 2011 one here.)

Not surprisingly, during the intervening years, scholars have been busy researching Capellani’s films and career. March 6 to 24 saw a major retrospective at the Cinémathèque Française. (Information on the program is still available online, as is a detailed press release.) Shortly before it began, the first biography appeared: Christine Leteux’s Albert Capellani: Cineaste du Romanesque, with a foreword by Kevin Brownlow.

Leteux discovered Capellani in May of 2012, thanks to seeing Notre-Dame de Paris and Les Misérables at the Forum des Images in Paris. Setting out to learn more about the filmmaker, she realized how thoroughly his memory had nearly vanished from film history. She sought out and received the cooperation of his grandson, Bernard Basset-Capellani, whom she describes as “intarissable” (inexhaustible) on the subject.

The result is a solid, traditional biography, with chapters mostly organized around the companies for which Capellani worked (Pathe, SCAGL, World, Mutual, and so on) and some of his key films (Les Misérables, The Red Lantern). The prose style is easily readable French, at least to someone like me with an average knowledge of the language. For an interview with Leteux concerning the book, see here.

The book is on sale at the Cinémathèque’s shop, which unfortunately does not sell online. It was supposed to be available on Amazon.fr, but so far is not. The easiest way for those outside France to order it is through three third-party book-sellers on amazon.fr, all offering it at the cover price of 14.90 €. Leteux’s book is a vital source for anyone interested in early cinema.

I was pleased to see that the last chapter ends with some quotations from my second entry on Capellani, ending with “With the end of the main retrospective, however, it is safe to say that from now on anyone who claims to know early film history will need to be familiar with Capellani’s work.”

The book includes a filmography and list of films available on DVD. These include a new one, a restoration of The Red Lantern by our friends at the Cinematek in Brussels, available on Amazon.fr or directly from the Cinematek’s shop.

The French-language historical journal on cinema, 1895, timed its March, 2013 issue to coincide with the Cinémathèque’s retrospective. It is entirely devoted to Capellani. I have not had a chance to see it yet, but the table of contents is available here. The only online purchasing source for individual issues I have found is here; the page gives a lengthy summary of the contents.

Mariann continues to search for more surviving prints for restoration and eventual inclusion in future editions of Il Cinema Ritrovato. She has sent me some tantalizing news about recent discoveries and restorations. There will be a third Capellani season in 2014. This will probably include some of the director’s American films: Social Hypocrites (now restored), Flash of the Emerald (the one surviving reel), Inside of the Cup (surviving but so far with no projection print), Eye for Eye (two surviving reals), Sisters, and the French film Le Nabab. Other possible restorations include House of Mirth, La belle limonadiere, and Oh Boy!

A description of the 2013 Ritrovato festival is available here.

Nanook and friends

Early this year we posted our annual list of the ten best films of ninety years ago. It featured the classic early documentary, Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North. In March our friends at Flicker Alley released a two-disc Blu-ray edition of Nanook paired with the 1934 Danish feature, The Wedding of Palo (Palos Brudefærd). The latter is one of those titles that one occasionally encounters on the fringes of older historical surveys, but it has been difficult indeed to see. This new print is a 2012 restoration from a George Eastman House original 35mm nitrate copy.

Nanook is familiar enough, but The Wedding of Palo is not. It was made by the Danish explorer and anthropologist Knud Rasmussen, who appears in a brief introductory passage. Clearly he was influenced by Flaherty’s work. He combines a simple fictional narrative with documentary scenes of traditional Inuit life in eastern Greenland. The basic story involves the heroine Navarona, whose brothers are reluctant to lose their housekeeper by allowing her to marry. Two men of the tribe court her and come into violent jealous conflict. Interjected are sequences of a salmon hunt, a festival, a traditional song duel between the two rivals, and a polar-bear hunt. The staged dialogue scenes involve sound recording, with no subtitles but the occasional brief intertitle to translate.

Nanook is familiar enough, but The Wedding of Palo is not. It was made by the Danish explorer and anthropologist Knud Rasmussen, who appears in a brief introductory passage. Clearly he was influenced by Flaherty’s work. He combines a simple fictional narrative with documentary scenes of traditional Inuit life in eastern Greenland. The basic story involves the heroine Navarona, whose brothers are reluctant to lose their housekeeper by allowing her to marry. Two men of the tribe court her and come into violent jealous conflict. Interjected are sequences of a salmon hunt, a festival, a traditional song duel between the two rivals, and a polar-bear hunt. The staged dialogue scenes involve sound recording, with no subtitles but the occasional brief intertitle to translate.

As in Nanook, the non-professional actors are remarkably natural, especially the “actress” portraying the heroine. There is a cute young boy brought in at intervals for comic appeal, and the members of the village seem always to be laughing and enjoying a suspiciously carefree life. The film has the advantage of more spectacular scenery than that in Flaherty’s film, with huge mountains and glaciers in place of the vast ice-covered vistas (see bottom image).

As usual, the Flicker Alley team has gone beyond the call of duty with this release. It includes not only the two features, but six bonus films, as described in the press release:

Nanook Revisited (Saumialuk) by Claude Massot was made in the same locations used by Flaherty. It shows how Inuit life changed in the intervening decades, how Flaherty consciously depicted a culture which was then already vanishing, and how Nanook is used today to teach the Inuit their heritage. Nanook Revisited was produced in 1988 on standard definition video for French television. Dwellings of the Far North (1928) is the igloo-building sequence of Nanook re-edited and re-titled as an educational film; Arctic Hunt (1913) and extended excerpts from Primitive Love (1927) are by Arctic explorer Frank E. Kleinschmidt; Eskimo Hunters of Northwest Alaska (1949) by Louis deRochemont shows many activities seen in Nanook thirty years after, and Face of the High Arctic (1959) depicts the ecology of the region, produced by the National Film Board of Canada.

Altogether, the films run an impressive 281 minutes. There’s also a booklet with excerpts from Flaherty’s book, My Eskimo Friends, an essay by Lawrence Millman, “Knud Rasmussen and The Wedding of Palo,” and notes on the films.

Snow White and the Seven (?) Bullfighting Dwarves

In 2011, a French film, The Artist, gained huge attention in the infotainment media as a modern version of silent cinema, winning yet another Best Picture Oscar for the Weinstein brothers. It was a reasonably successful imitation of mid- to late 1920s cinema during the transition to sound. Now a much better modern silent film has arrived, Pablo Berger’s Blancanieves, a loose version of the Snow White story transposed to 1920s Spain. A famous bullfighter is paralyzed after being gored in the ring. His wife dies in childbirth and his scheming nurse marries him. She keeps his daughter, Carmen, away from her father by setting her to work as a downtrodden servant in his country estate. Upon her father’s death, the evil wife schemes to have her killed, and she escapes to the protection of a troupe of six bullfighting dwarves who, possessing uncertain arithmetic skills, bill themselves as seven bullfighting dwarves.

While The Artist was a fairly good imitation of 1920s Hollywood filmmaking, Blancanieves is a pastiche of the 1928-29 era of European silent cinema. It draws on what I have termed the International Style of filmmaking, a late 1920s blend of influences from the French Impressionism, German Expressionism, and Soviet Montage movements. One could almost pass it off as a genuine film of the era.

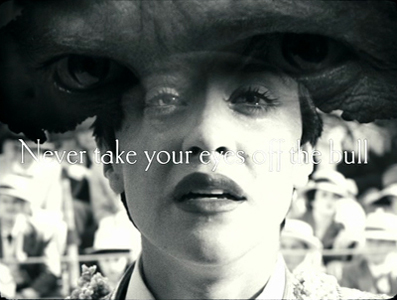

At times there are subjective effects à la Impressionism. A superimposition conveys Carmen’s memories of her father’s crucial instructions to her, and superimposed images of hands waving handkerchiefs present the enthusiam of the crowd’s plea for the bull to be pardoned.

This was also the period in which the power of the wide angle lens, particularly in close-ups and in low-angle shots, was exploited, initially in Soviet cinema and then all over Europe. Blancanieves is full of such shots, as in the frame at the top of this entry and in these two shots from the opening scene:

There are also montage sequences, building up to flurries of very short shots. This accelerated-editing technique is typical of both Soviet and French filmmaking of the era.

The too-frequent use of handheld camera in Blancanieves detracts somewhat from the feeling of authenticity. In the late 1920s, cameras were too heavy to be handheld. They could be strapped to the body of the cinematographer with harnesses, but that creates a subtly different look. And during the late 1920s, shots with the camera holding on a character while the background spins around behind him or her would have been achieved by placing both camera and actor on a large turntable. (This effect apparently was pioneered in Germany in the mid-1920s). But the occasional dramatic lighting effects, particularly in the climactic scene, are distinctly reminiscent of German cinema.

In general, the narrative is charming and amusing. The heroine’s pet rooster provides exactly the sort of comic relief that is common in films of the 1920s, and the story has an effective fairy-tale quality. I found the ending a bit disappointing and certainly not typical of the films of the 1920s. Still, Berger has clearly watched an enormous number of 1920s European films and absorbed their styles. He can imitate the International Style remarkably well, telling a tale that is appropriate to the 1920s and yet has a touch of humor that doesn’t belittle the silent era.

Blancanieves was released in the US on March 29 and is currently making the rounds of art-houses and festivals.

Other entries discussing the International Style and wide-angle filming at the end of the silent era can be found here and here.

The Wedding of Palo

Sir Alfred simply must have his set pieces: THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH (1934)

The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934).

DB here:

Hitchcock made six remarkable thrillers from 1934 through 1938, and I have long believed that the first one was the best. I think very well of Sabotage, and both The Lady Vanishes and The 39 Steps are strong contenders. But for me, The Man Who Knew Too Much has got damn near everything going for it.

I came to it a little late. It wasn’t the first Hitchcock I wrote about; that was Notorious, in a 1969 piece that nakedly reveals the limitations of a college senior’s knowledge. Nor was it the first Hitchcock I saw; that was Vertigo, when I was about ten. Inauspiciously for me, when Vertigo was revived for national television broadcast in 1972, I was flying to a job interview in Madison, Wisconsin.

I got that job, though, and soon The Man Who Knew Too Much became very important for me. Seeing it at a film society screening, I was bowled over. Then I discovered that it was available for purchase in a cheap 16mm print. I bought a print and began teaching the film as a model of narrative construction. It worked its way into the first edition of Film Art, in 1979 and hung around there for several editions.

That sample analysis has been available as a pdf on our site, but check it out at the Criterion site, where it’s enhanced with nice frame enlargements and a major extract. The essay makes my case for the movie as an extremely well-constructed piece in the classical storytelling tradition.

So I was the ideal consumer for a spruced-up DVD/ Blu-ray release, and as usual Criterion doesn’t disappoint. It’s a handsome version, with some fine supplements. We get two rare interviews with Sir Alfred from CBS’s arts program Camera Three (featuring Pia Lindstrom and William K. Everson) and a perceptive discussion with Guillermo del Toro, who makes a vigorous case for the film. So does Philip Kemp in his commentary, which is strong on production background. Kemp offers valuable information on script versions and on Hitchcock’s niche in the English industry. The accompanying booklet includes a lively appreciation by The Self-Styled Siren, aka Farran Smith Nehme.

So I was the ideal consumer for a spruced-up DVD/ Blu-ray release, and as usual Criterion doesn’t disappoint. It’s a handsome version, with some fine supplements. We get two rare interviews with Sir Alfred from CBS’s arts program Camera Three (featuring Pia Lindstrom and William K. Everson) and a perceptive discussion with Guillermo del Toro, who makes a vigorous case for the film. So does Philip Kemp in his commentary, which is strong on production background. Kemp offers valuable information on script versions and on Hitchcock’s niche in the English industry. The accompanying booklet includes a lively appreciation by The Self-Styled Siren, aka Farran Smith Nehme.

Interest in Hitchcock seems to be the one constant in the whirligig of tastes in film culture. He is a mainstay of home video and cable television; apparently the films can be re-released in perpetuity. Professors love to teach his films. The techniques are obvious and vivid, and the films offer a manageable complexity that encourages interpretation. Class, gender, power, the law—whatever your favorite themes, they’re all on the surface, yet enticingly ambivalent. Not to mention how much fun these movies are to watch. I’ve always enjoyed introducing “lesser Hitchcock” like Stage Fright and Dial M for Murder and then watching the audience fall under their spell.

Critics navigate by Hitchcock as a fixed pole star. Reviewers compare every new thriller to the classics of The Master of Suspense. Just look at what people write about Soderbergh’s Side Effects. And for those who promoted the auteur approach to Hollywood cinema, Hitchcock was a beachhead. Who could doubt that this man turned out personal projects within the impersonal machine known as Hollywood? And if he could do it, why not Ford, Hawks, Sternberg, Ray, and all the rest? Hitchcock nudged skeptics down the slippery slope toward auteurism.

Even if Hitchcock isn’t to your taste, you can’t avoid his influence. That became obvious around the 1970s, when directors began borrowing from him more or less overtly: Spielberg’s Vertigo track-and-zoom in Jaws (now itself a convention), De Palma’s homages/pastiches, Polanski’s use of point-of-view in Repulsion and Rosemary’s Baby, the endless Psycho sequels and the van Sant remake, and the rest. But Hitch was no less influential in his own day; I’d argue that filmmakers of the 1940s had to raise their game if they wanted to meet the challenge of Rebecca, Foreign Correspondent, Suspicion, Shadow of a Doubt, Spellbound, and Notorious. Billy Wilder told a reporter that Double Indemnity was his effort to “out-Hitch Hitch.”

What was so special? Obviously, the throwaway humor—sometimes airy, sometimes slapstick, sometimes sardonic. And obviously a gift for switching situations around, playing them against cliché, setting us up for a jolt. But I think there’s something else afoot. Part of the Master’s repute rests on virtuosity of film technique. Hitchcock makes movie movies, even when, like Rope or Dial M, they seem “theatrical.” And this movieness is best seen, I think, by considering a term that always comes up with Lord Alfred: the set piece.

Maintaining a tradition

Hitchcock held onto the flamboyant expressive devices of silent and early sound cinema far longer than any other director. For decades he kept alive techniques that many directors thought were old hat: abrupt cuts to details of gestures and objects; blurry point-of-view images to suggest distraught or befuddled states of mind (as above); very brief insert shots to accentuate violence. Compare Battleship Potemkin with Foreign Correspondent’s assassination scene.

Hitchcock built entire films around classic silent techniques. The Kuleshov effect governs Rear Window; the German “entfesselte” or “unchained” camera dominates Rope and Under Capricorn. Rope and Dial M revive the aesthetics of the German kammerspielfilm, or “chamber play.” The Germanic look was alive and well in the spiderweb shadow-work of Suspicion, while both French Impressionism and German Expressionism inform the dream sequences of Spellbound and Vertigo. He also preserved the “creative use of sound” that was the hallmark of directors like Clair and Milestone. While others had pretty much given up the expressionistic use of music and effects, Hitchcock was always ready to draw on them. The hallucinatory Merry Widow Waltz haunts Shadow of a Doubt, while Hitchcock’s penchant for giving us two pieces of information simultaneously, one in the image and another on the soundtrack, let him design scenes visually and push a lot of dialogue offscreen.

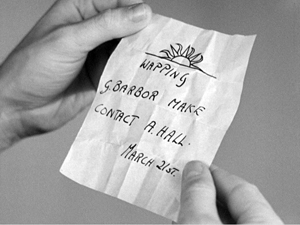

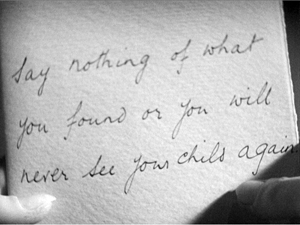

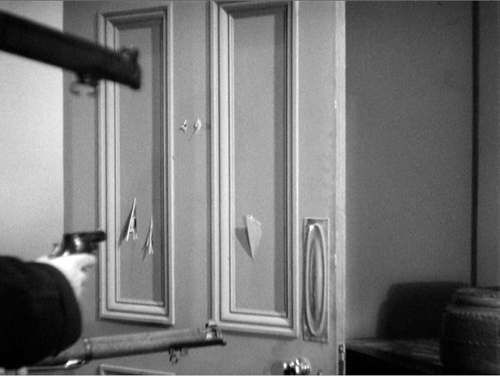

This flexibility of technique modulates from scene to scene. In The Man Who Knew Too Much, note-reading is presented in three ways, in rapid succession. First, Bob finds Louis’ note in the hairbrush.

Soon Bob gets a message from the front desk. What does it say? Hitchcock hides that by, for once, not supplying subjective point of view.

Only when the note is passed to Jill do we get to see it, but with a twist. Nobody but Hitchcock would add an extra shot that cuts to the note in her hand without revealing what it says.

That extra shot is what Eisenstein called a primer; as with dynamite, you need a little charge to trigger the blast.

We often forget that classic silent directors used their pictorial techniques for suspense. Lang’s Mabuse films and Spione furnish plenty of instances, but so do the Soviet montage films. The scene in which the police wait for the worker to return to his wife in The End of St. Petersburg now looks like pure Hitchcock, and of course the Odessa Steps sequence was the Psycho shower of its day. So it isn’t surprising that Hitchcock would turn his silent-film virtuosity toward creating scenes of high tension and threatened violence. Nor is it surprising that his skills would crystallize in “set pieces.”

Everybody talks about Hitchcock’s fondness for set pieces. It’s part of his brand. We have the Statue of Liberty climax in Saboteur, the milk carried up the staircase in Suspicion, the milk-and-razor scene and the final suicide in Spellbound, the spectacular rescue of Alicia at the end of Notorious, and the efforts of Bruno to retrieve the lighter in Strangers on a Train.

But, come to think of it, what makes something a set piece?

Game, set piece, match

Foreign Correspondent (1940).

As commonly understood in the arts, a set piece is a fairly self-contained portion of a larger work. It has a distinct beginning and end, and it’s understandable and impressive if extracted from its original. It’s designed to be a bravura display of concentrated virtuosity. In music, an example would be an operatic aria like the Queen of the Night’s in The Magic Flute: it is so flashy and complete in itself that it can enjoyed on its own, in a concert setting.

Two early uses of the term shed light on its implications. In stage parlance, a “set piece” is an item of the set that can stand alone, like a gate or fake tree. In pyrotechnics, a “set piece” is a carefully patterned arrangement of fireworks; here again, it implies a display that dazzles the audience.

In the silent era, I’d suggest, the clearest exponent of set pieces is Eisenstein, who became known as “the master of the episode.” Many of his big scenes, like the Odessa Steps massacre, are developed at such length that they function as mini-films. But you can consider passages in Chaplin and Keaton as set pieces—the dance of the breadrolls in The Gold Rush perhaps, or the windstorm in Steambout Bill, Jr. The musical would seem to be a natural home of the set piece, with numbers standing out against more mundane scenes. In modern cinema, again under the aegis of Hitchcock: De Palma offers plenty, and perhaps the prize fights in Raging Bull constitute a string of them. Today the home of the set piece is the action picture; the chases and fights are the main attraction, and the genre challenges directors and crew to find new ways to intoxicate us.

The aesthetic of the set piece implies that some scenes function as filler while others get the whipped-up treatment. If that’s right, many great directors don’t favor mounting set pieces. Ozu, Mizoguchi, Dreyer, Hawks, and others present what we might call “through-composed” films. Just as Wagnerian opera and its successors minimized set pieces, these filmmakers create a surface texture that doesn’t create self-contained high points. (I grant you that the immolation of Herlofs Marthe in Dreyer’s Day of Wrath might count.)

Given the detachable quality of set pieces, it’s true that some of Hitchcock’s can seem implausible or gratuitous. How essential is Guy’s lighter to any plausible scheme of Bruno’s? If you want to kill Roger Thornhill, why send him to a crossroads in Midwest corn country? (A knife in the back on the Greyhound is more reliable.) It was this tendency to sacrifice story logic for stunning anthology bits that Raymond Chandler deplored:

The thing that amuses me about Hitchcock is the way he directs a film in his head before he knows what the story is. You find yourself trying to rationalize the shots he wants to make rather than the story. Every time you get set he jabs you off balance by wanting to do a love scene on top of the Jefferson Memorial or something like that.

Chandler has a point. How do you integrate a set piece into a whole movie? (I’ll make some suggestions shortly.) But first, give Hitch his due. For him, I think a set piece was a compact repository of inherently cinematic ideas carried to a limit within a sequence. A set piece is a challenge: How much can you squeeze out of a situation?

Go back to Foreign Correspondent. Setting an assassination in Amsterdam allowed Hitchcock to integrate the idea of a clue based on a waywardly turning windmill. So far, Chandler’s objection seems tenable: The windmill is just a gimmick. But once Hitchcock sets his hero exploring the lair, he can create a set piece that answers a question that no one ever thought to ask before: How do you eavesdrop in a windmill?

Johnny Jones has to evade the killers by crawling up alongside the giant gears, then down, then up again. At each step he barely escapes being spotted. When he seems safe, his topcoat gets snagged in the grinding gears, so he has to slip his arm out of it—just in time to avoid being crushed.

Yet once Jones is freed from the coat, it’s carried around the gearwork and might be spotted by the gang. And the old diplomat upstairs, mind hazed by drugs, is likely to reveal Jones’ presence. Hitchcock squeezes seven minutes of suspense out of all this, with a casual air that suggests: Of course, dear chap, any director worth his salary can see that a windmill harbors all kinds of excruciating menace. All in a day’s work, you know.

A whispered terror on the breeze

If anything is a set piece, the Albert Hall sequence in The Man Who Knew Too Much is. Philip Kemp’s commentary for the Criterion DVD considers it Hitch’s first, although aficionados would probably consider the “knife” sound montage of Blackmail at the very least a rough sketch for what would come. Lucky you: The entire Albert Hall sequence is excerpted on the Criterion site.

A set piece benefits from a simple premise. Here, Jill’s child is being held hostage, which keeps her from informing the police of what little she knows about the plot. We know that during the concert an assassin will try to shoot a diplomat.

You can imagine Chandler asking: Why plug Ropa during a concert, with all those witnesses? Why not when the target is on the sidewalk, shot from a rooftop for easy escape? You can hear that bland replying murmur: Raaaymond, it’s only a moovie…

So we have some conditions for a set piece: a compact piece of action limited in time and space. But there’s also a strong time marker. Ramon the assassin is to wait for a dramatic pause in the score; it’s followed by a shattering choral outburst that will muffle the pistol shot. We’ve been given a rehearsal of the passage in a gramophone record, but since we don’t hear the whole piece then, we can’t predict exactly when the chorus will hit its peak.

Hitchcock magnifies this uncertainty by letting the piece, Arthur Benjamin’s Storm Clouds Cantata, play out in its entirety. Its combination of lyrical and dramatic passages blend into a stream of music that coincides with the emotional action onscreen. I suspect that the piece, composed specifically for the film, glances at the most celebrated new choral piece of the era, William Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast (1931). It too has a charged dramatic pause followed by a tremendous choral blast: “Slain!” You can listen to it here, and you can hear some of the musical affinities at 27:11 and after.

So the self-contained quality of the sequence is enhanced by the unfolding soundtrack, as well as its “bookend” structure: Jill arrives at the Albert Hall/ Jill leaves. (Hitchcock was very fond of this coming-and-going bracketing; many scenes of The Birds are built out of this.) But to be a set piece we need virtuosity too, right?

As our Film Art essay indicates, Hitchcock structures the scene using nearly every technique in the silent-cinema playbook. We get dynamically accentuated compositions, crisp point-of-view editing, subjective vision (even blurring as Jill drifts into a panicky reverie), and suspenseful crosscutting back to the gang holding Bob and Betty prisoner. The techniques build to their own crescendo, with more and shorter shots of Jill, the orchestra players, and the curtain concealing Ramon. As the climax approaches, details of the players’ performance pass in a flash. As another layer, though, all these visual techniques are synchronized with the musical structure of the piece. Most obvious is the slow tracking shot back from Jill as the female soloist launches in:

There came a whispered terror on the breeze./ And the dark forest shook.

The text has always teased me, because in my early years of studying the film I couldn’t hear everything there. Now that the Storm Clouds Cantata has become a minor concert piece, we have a full version of the text. It’s the description of an especially ominous storm, one that drives birds away and makes trees tremble in fear. The only creature left, vulnerable to the gale, is a child:

Around whose head screaming/ The night-birds wheeled and shot away.

The orchestral and choral forces mount on the line that has always come through the sound mix:

All save the child—all save the child.

The line is ambiguous. Its literal sense is that all the creatures have fled the oncoming storm except the child (“all save the child”). But Hitchcock’s cutting and the film’s overall context leave it as an imperative: the child must be rescued. Thus the musical dynamics and the text stress, for us and presumably for Jill, that Betty’s safety depends on what she does.

Soon the cantata’s text finds another analog in the concert hall. The choir sings of the storm clouds finally breaking and “finding release.” That phrase, repeated with rising intensity, yields the dramatic pause and then the final outburst that is to cover Ramon’s pistol shot. But now we have to see this phrase as prophecy and comment: Jill’s scream during the pause is the release of her tightened anxiety. And of course the line slyly signals the release of the suspense built up through the whole sequence.

With Hitchcock, you always get more.

In all, the sequence becomes exactly what a set piece ought to be: compact, with sharp boundaries and a strongly profiled arc of interest, elaborated with a great variety of technical resources and a thrusting emotional impact. But is it too much of an independent sequence? One can imagine Chandler worrying that Hitch doesn’t care much about how to hook it up with everything else. Let’s see.

This scepter’d isle

There’s no doubt that a plot driven by set pieces can seem episodic, just a matter of pretty clothes clipped to a slender line. In action movies it’s a classic problem, which, say, Speed doesn’t fully solve but Die Hard does.

You can mask an episodic plot, though, through some stratagems. First, make your filler material charming. The Man Who Knew Too Much gives us comedy in the dentist office and in the Tabernacle, with Bob and Clive mumbling messages through hymnody. You can also whisk the audience from scene to scene so quickly that the viewer has to concentrate on local connections. This is one purpose of what I’ve called the hook, the transition that smoothly links the end of one scene with the beginning of the next. If you’ve got some plot holes, strengthen your hooks–especially those that hide your gaps.

The Man Who Knew Too Much has some nifty hooks. I especially like the way the fingers pointing to the bullet hole are followed by a shot of Ramon’s head: effect and cause neatly given by a straight cut. Then there’s the contrast of the fire in the fireplace dissolving to the skier pin, a sort of thermal hook. But probably the most memorable one is Betty’s line about Ramon’s brilliantined hair.

This hook is a motif as well, and recurring images or sounds like this can help knit together your movie. In Foreign Correspondent, we get hats and birds in various scenes. Here, as our Film Art essay indicates, teeth, the skier pin, sharpshooting, the cantata’s main theme, and other motifs weave through the overall structure of the film.

You can as well knit your big scenes together through certain narrative patterns, such as a trip or a search, both strategies that Hitchcock employs in many movies. In The Man Who Knew Too Much, Bob’s investigation of the gang follows the menu set out in Louis’ note: the sun emblem, Wapping, G. Barbour, and A. Hall. This serves as a sort of map for the middle act of the film. Once Bob has cracked the message, though, the film shifts into a new register. Jill, who has been waiting passively at home, takes over the role of protagonist. And her actions will fulfill another motif: that of interruption and distraction.

The film begins with Betty’s dog disrupting Louis’ ski jump. That’s an innocent accident, as is the moment when Jill nearly spoils Roman’s skeet shooting. But soon afterward Abbott’s chiming watch deliberately breaks Jill’s concentration, making her lose the shooting match. In effect the Albert Hall sequence offers payback: With her scream Jill not only disrupts the performance but spoils Ramon’s aim as Abbott had spoiled hers.

The Albert Hall sequence fits into the film in a less obvious way, one that plays along the thematic dualities that marble the movie. Throughout the film contrasts “Englishness” with “foreignness,” the latter split between allies (Louis, Ropa) and enemies. The Storm Cloud Cantata and what follows represent a sort of triumph of England over her adversaries.

At the St. Moritz resort, the Lawrence family is set off from Louis, their French friend, and two men: Abbott the German and Ramon the Latin. (He’s handily fudged; he has a Spanish name but calls the English “extraordinaire.” And his hair is greasy.) “Sworn enemies, eh?” Jill says half-humorously to Ramon before losing the skeet shoot. After Louis’ death Bob is at a loss in the hotel, unable to speak German or Italian, and distracted while Betty is kidnapped. The English aren’t at home in this world.

Once Bob and Jill have returned to London, they join the family friend Clive, a Wodehousian upper-class twit but gifted with loyalty and tenacity. Bob and Clive have learned from Gibson of the Foreign Office that the gang intends to assassinate the diplomat Ropa. They must tell what they know; the killing could prove as catastrophic as the assassination that triggered the war of 1914-1918. Yet Bob keeps mum. He might be enacting E. M. Forster’s dictum: “If I had to choose between betraying my friend and betraying my country, I hope I would have the guts to betray my country.”

The conflict between family love and civic duty is played out in the rest of the second act, when the men’s investigation takes them to a working-class neighborhood of Wapping. There, we learn that behind respectable English institutions—a dentist, eccentric religion—foreign elements lurk. Bob has solved Louis’ riddle, but at the cost of becoming another hostage. Bob and Betty re-meet, in a characteristically subdued stiff-upper-lip encounter that denies Abbott the tearful scene he expected. The dignity with which Bob conducts himself, asking about Betty’s dressing gown and her school grades while staring defiantly at the gang, leaves the others abashed.

Clive has escaped, though, and has managed to send Jill to the Albert Hall. That musical set piece initiates the film’s climax dramatically but also thematically. For one thing, Benjamin’s cantata reaffirms another bit of Englishness. A national choral tradition runs back to Purcell and Handel, was sharpened in Mendelssohn’s Elijah, and was revived in the early twentieth century by Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius and Vaughan Williams’ Sea Symphony. Hitchcock and screenwriter Charles Bennett could have used Bach or Beethoven, but the choice of this brooding, mildly modernistic piece reminiscent of Walton is a nice bit of propaganda for British musical culture of the interwar years.

More importantly, the concert sequence solves the film’s ideological problem: How to save the world without destroying your family? Jill’s impulsive scream doesn’t divulge what she and Bob know about the gang, but it does serve to derail the gang’s plan and save Ropa. And by leading the police to follow Ramon to the hideout, she in effect chooses to risk Betty and Bob for the capture of the gang. Here, perhaps, the sheer drive of the action muffles the significance of her choice; Chandler complains that Hitchcock tended to take refuge from plot problems in “wild chases.”

What follows, in the middle of some violence that remains shocking today, is a vigorous reassertion of Englishness. The vignettes during the siege display stalwart national virtues. A postman insists on making his rounds during the gunplay. An inspector swipes sweets and pauses for a cup of tea. The police reluctantly take up arms, only after several of their unarmed number are mowed down. Slipping into adjacent buildings, snipers move a piano while its fussy owner rescues his potted plant. And a cop who was slated to go off duty finds a warm mattress to die on. This unassuming valor, so different from Ramon’s petulant swagger and Abbott’s self-congratulatory sadism, will win out. The victory is announced by the pent-up crowd rushing jubilantly forward as the siege ends.

In any other movie the mother would have been huddling with the child and the man would grab a rifle to pick off his enemy on the roof. But making Jill the crack shot reasserts another quintessentially English image: the hunting, shooting, riding mistress of the estate. She gets her second chance to fire, bringing down Ramon when even the police sniper hesitates. It’s also a bit of guilty revenge for the death of Louis, whom Jill danced into the line of fire. Hitchcock, as usual, renders it elliptically: we see Jill grab the gun but not fire it. As she and Bob and Betty are reunited, the movie that began with the line, “Are you all right, sir?” ends with a mother reassuring her weeping daughter, “It’s all right.”

This, we might say, is how you integrate set pieces into your movie—narratively, stylistically, and thematically. Others would disagree with me, but nearly forty years of living with this film hasn’t made me change my mind. The Man Who Knew Too Much is Hitchcock’s first thoroughgoing masterpiece.

Thanks to Abbey Lustgarten, UW-Madison alum, for her excellent production job on the Criterion disc. Thanks also to Peter Becker and Casey Moore for coordinating the posting of our Film Art piece with this blog entry.

For more on Chandler and Hitchcock, see William Luhr, Raymond Chandler and Film (New York: Unger, 1982), 81-93. My quotation comes from Raymond Chandler Speaking, ed. by Dorothy Gardiner and Kathrine Sorley Walker (Books for Libraries Press, 1971), 132.

Hitchcock probably doesn’t deserve 100% of the credit for the Foreign Correspondent windmill scene; it was designed by the great William Cameron Menzies.

When I wrote the Film Art analysis back in the 1970s, Kristin hadn’t elaborated her ideas about how large-scale parts, or acts, can shape a film. Yet I think that the three parts that the analysis mentions constitute pretty well-articulated acts. The first part has as its turning point Bob’s realization that when Gibson traces Betty’s call, police will converge on Wapping and endanger her. So Bob and Clive set out to save her. That decision comes about twenty-six minutes into the movie. I’d mark the end of the second act with Abbott’s sending Ramon on his mission after playing the cantata recording; that comes at about fifty-three minutes into the film. At this point we know everything we need to know, so the premises can play out. The last act is shorter, as climaxes tend to be. The Albert Hall sequence and the final shootout and rescue take up the final twenty-three minutes, capped by a very brief epilogue of the reunited family. For more on act structure, see Kristin’s entry here, mine here, and my essay on action movies, as well as Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood and my The Way Hollywood Tells It.

A final note: Frank Vosper, who plays Ramon, was a well-known stage actor and playwright. His most famous play is Love from a Stranger (1936); the film version was released in 1937. Another successful Vosper play was the fantasy comedy Murder on the Second Floor (1929), in which a writer devises a play consisting of all the clichés of sensational mystery fiction. But the Vosper play that piques my curiosity most is his 1927 drama called—I’m not kidding—Spellbound.

See? With Hitchcock you always get more.

The Man Who Knew Too Much.

Sometimes two shots . . .

The Mormon’s Victim (1911).

DB here:

. . . just knock you out.

Last summer during a trip to the Royal Film Archive of Belgium I came across a single camera setup that bloomed like a flower in an almost casual way. This entry is in the same spirit, but there’s nothing casual about this cut. I spotted it during my current visit to the Danish Film Archive in Copenhagen.

Nina Gram is engaged to Sven Berg, best friend of Nina’s brother Olaf. But Andrew Larsson, a Mormon, fascinates Nina with his courtliness and his gripping sermons. One night, during a visit to her family’s home, Larsson gets Nina alone while Sven, Olaf, and others are playing cards in another room. She’s starting to succumb to Larsson’s charm offensive (though we think he has offensive charm).

As The Mormon’s Victim (Mormonens Offer, 1911; Nordisk Films, directed by August Blom) develops, Larsson will induce Nina to flee to Utah with him, where he’ll keep her prisoner. Sven and Olaf will track them down by train, ship, and auto, the entire flight and pursuit joined through crosscutting reminiscent of Griffith. The Mormon’s Victim has several memorable shots, including some striking ones taken from a car. But in particular there’s this cut. The two shots surmount today’s entry.

A full shot shows Larsson and Nina in the parlor. Earlier in the scene Sven has left the card game in the distant room to check on what his fiancée is up to. He comes forward hesitantly; this is partly to express his vague worries about Larsson, but it’s also Blom’s way of making sure we know it’s Sven in the rear of the tableau. When Sven returns to the game, he settles in directly behind Nina and Larsson, so that he becomes the most visible figure at the card game.

When Larsson entices Nina away from the piano, they place themselves on the settee in the foreground. And in my first image up top, we can see solid, oblivious Sven right behind them. A blow-up of that area of the shot is on the right.

Then Blom cuts directly in. The axial cut was the most frequent sort of editing found within scenes at this period, and Blom’s cut is more or less along the camera axis, though displaced a bit to the right. The result is a medium two-shot of Larsson staring almost hypnotically at Nina and her responding with rising passion.

You see where I’m going with this. There’s actually a third person in the shot. Sven is still sitting behind them, but now even more tightly sandwiched between the faces–a tiny figure but fully discernible in the 35mm print. On the right I enlarge that portion of the image for you. Dead center, Sven’s tiny head floats between their profiles like a bubble from Nina’s lips or a rose between her teeth.

You see where I’m going with this. There’s actually a third person in the shot. Sven is still sitting behind them, but now even more tightly sandwiched between the faces–a tiny figure but fully discernible in the 35mm print. On the right I enlarge that portion of the image for you. Dead center, Sven’s tiny head floats between their profiles like a bubble from Nina’s lips or a rose between her teeth.

This is a remarkable shot. Since Nina eventually turns away and refuses Larsson’s kiss, we’re tempted to say that the shot creates a visual metaphor, suggesting that Sven “comes between” them. Fair enough, especially since the Danes have the same figure of speech (at komme i mellem). But I’d also want to signal how this possibility of thinly-sliced depth fits smoothly into the tableau style I’ve discussed many times on this blog and in my recently posted video lecture. It relies on hyper-precise staging in depth, accentuated by the axial cut (always a cut that accentuates depth).

It’s all the more remarkable because in those days, the camera viewfinder was mounted alongside the lens. We’re so used to reflex viewing–that is, seeing exactly what the lens of our camera or phone is framing–that we tend to forget that until the 1960s, in most cases a cinematographer had to compose the shot allowing for the parallax difference between the viewfinder and the lens. True, in most tableau shots the camera is far enough back to give some leeway for background planes, and some cameras could swivel (“toe in”) the viewfinder inward as the framing got closer. But this scene remains an extraordinary piece of filmmaking. The cinematographer Axel Graatkjaer, only twenty-six when he shot this film, deserves credit for pulling off a rare stunt.

The Mormon’s Victim is yet another example of the great variety and boldness of the cinema of the 1910s. Had I known it, I would probably have squeezed it into my video lecture, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.” Maybe I can work it into the followups I plan to post later this year. In the meantime, take this as another instance of why we should thank film archives for preserving fairly obscure films that have a lot to teach us about what talented creators have done with our favorite medium.

Ron Mottram surveys the local films of this period in his indispensable The Danish Cinema before Dreyer. For more on the tableau style, see the lecture I just mentioned, along with the blog entries in the category. I have more on Danish films and the tableau tradition here, and I discuss that tradition as a background to Dreyer in an essay on the Danish Film Institute’s Dreyer site.

Thanks to Thomas Christensen and Mikael Braae of the archive for all their help. I have devoted other entries to their archive and Danish film culture, but this might be the most relevant today.

Mikael Braae surveys a recently received collection of over 400 35mm film prints. He’s in the process of sorting and examining them. There are still big 35mm collections out there!