Archive for the 'Film piracy' Category

Creating a classic, with a little help from your pirate friends

DB here:

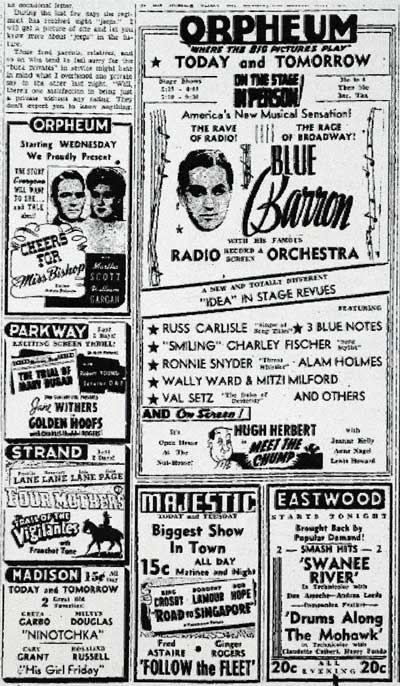

In early April of 1940, His Girl Friday came to Madison, Wisconsin. It ran opposite Juarez, The Light that Failed, Of Mice and Men, and a re-release of Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Pinocchio was about to open. Most screenings cost fifteen cents, or $2.21 in today’s currency.

Before television and home video, film was a disposable art. Except in big cities, a movie typically played a town for a few days. Programs changed two or three times a week, and double bills assured the public a spate of movies—nearly 700 in 1940 alone. People responded, going to the theatres on average 32 times per year. Given the competition, it’s no surprise that His Girl Friday didn’t stand out in the field; it was nominated for no Academy Awards and honored by no prizes. On just a single day in Madison, the cast of His Girl Friday was up against icons like Muni, Colman, March, and Bette Davis.

Nowadays, of course, nearly everyone regards HGF as one of the great accomplishments of the studio system. Most would consider it a better movie than any of the others it played opposite in my home town. A typical example of critical exuberance is Jim Emerson’s comment here. Or read James Harvey’s 1987 encomium:

It would be hard to overstate, I think, the boldness and brilliance of what Hawks has done here: not only an astonishingly funny comedy, but a fulfillment of a whole tradition of comedy—the ur-text of the tough comedy appropriated fully and seamlessly to the spirit and style of screwball romance. His Girl Friday is not only a triumph, but a revelation.

Oddly, this extraordinary film lay largely unnoticed for three decades. How did it become a classic? The answer has partly to do with the rising status of Howard Hawks, the director, among critics. It also owes something to changes in how academics thought about film history. And a little movie piracy didn’t hurt.

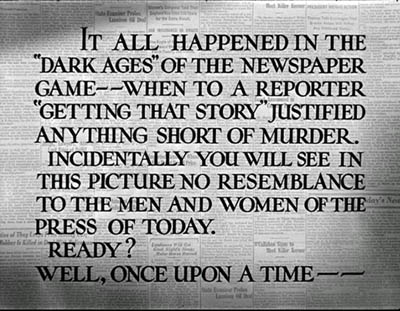

An unseen power watches over the Morning Post

Hawks the Artist is a creation of the 1960s. Before that, American film historians almost completely ignored him. Andrew Sarris often reminds us that he’s absent from Lewis Jacobs’ Rise of the American Film (1939), but he’s also missing from Arthur Knight’s The Liveliest Art (1957), the most popular survey history of its day. Apart from press releases and reviews of individual films, there were few discussions of Hawks in American newspapers and magazines. The most famous piece is probably Manny Farber’s “Underground Movies” of 1957, which treats Hawks along with other hard-boiled directors like Wellman and Mann.

From the start, Hawks was more appreciated in France. There film historians acknowledged A Girl in Every Port (1928), in part because of the presence of Louise Brooks, and they usually flagged Scarface (1932) as well, which they could see and Americans couldn’t. (Howard Hughes kept it out of circulation for decades.) But Hawks is barely mentioned in Georges Sadoul’s one-volume Histoire du cinéma mondiale (orig. 1949) and he’s ignored in the 1939-1945 volume of René Jeanne and Charles Ford’s monumentally monotonous Histoire encyclopédique du cinéma (1958).

The essay that marked the first phase of reevaulation was evidently Jacques Rivette’s “The Genius of Howard Hawks” in Cahiers du cinéma in 1953. Inspired by Monkey Business, Rivette’s philosophical flights and you-see-it-or-you-don’t tone helped define the auteur tactics identified with Cahiers’s young Turks. Rivette and his colleagues became known as “Hitchcocko-Hawksians.” The essay, however, doesn’t seem to have been immediately influential. Antoine de Baecque claims that within Cahiers, an admiration for Hawks was controversial in a way that liking Hitchcock was not. (1) It took some years for Hawks to ascend to the Pantheon.

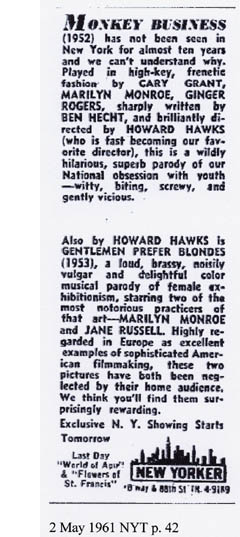

The story of that ascent has been well-told by Peter Wollen in his essay, “Who the Hell Is Howard Hawks?” In France, the Young Turks’ tastes had been nurtured by Henri Langlois, who showed many Hawks films at the Cinémathèque Française. In New York, Andrew Sarris and Eugene Archer had become intrigued by Cahiers but were ashamed that as Americans they didn’t know Hawks’ work. They persuaded Daniel Talbot to show a dozen Hawks films at his New Yorker Theatre during the first eight months of 1961. The screenings’ success allowed Peter Bogdanovich to convince people at the Museum of Modern Art to arrange a 27-film retrospective for the spring of 1962. The package went on to London and Paris, sowing publications in its wake.

The story of that ascent has been well-told by Peter Wollen in his essay, “Who the Hell Is Howard Hawks?” In France, the Young Turks’ tastes had been nurtured by Henri Langlois, who showed many Hawks films at the Cinémathèque Française. In New York, Andrew Sarris and Eugene Archer had become intrigued by Cahiers but were ashamed that as Americans they didn’t know Hawks’ work. They persuaded Daniel Talbot to show a dozen Hawks films at his New Yorker Theatre during the first eight months of 1961. The screenings’ success allowed Peter Bogdanovich to convince people at the Museum of Modern Art to arrange a 27-film retrospective for the spring of 1962. The package went on to London and Paris, sowing publications in its wake.

For the MoMA retrospective, Hawks granted Bogdanovich a monograph-length interview, which was to be endlessly reprinted and quoted in the years to come. (2) Sarris, now knowing who the hell Hawks was, wrote a career overview for the little magazine, The New York Film Bulletin, and this piece became a two-part essay in the British journal Films and Filming. Both Bogdanovich and Sarris made brief reference to His Girl Friday, as did Peter John Dyer in another 1962 essay, this one for Sight and Sound. At the end of 1962, another British magazine, Movie, published an issue on Hawks. At the start of 1963, Cahiers devoted an issue to him, including an homage by Langlois himself. Thanks to the work of Archer, Bogdanovich, Sarris, and MoMA, Hawks was rediscovered.

Sarris provided a condensed case for Hawks in his far-reaching catalogue of American directors, published as an entire issue of Film Culture in spring of 1963. There followed an interview with Hawks’s female performers in the California journal Cinema (late 1963), an appreciation by Lee Russell (aka Peter Wollen) in New Left Review (1964), another Cahiers issue (November 1964), J. C. Missiaen’s slim French volume Howard Hawks (1966), Robin Wood’s Howard Hawks (1968), and Manny Farber’s Artforum essay (1969). There were doubtless other publications and events that I never learned about or have forgotten. In any case, by the time I started grad school in 1970, if you were a film lover, you were clued in to Hawks, and you argued with the benighted souls who preferred Huston. . . even if you hadn’t seen His Girl Friday.

Light up with Hildy Johnson

One of my obsessions in graduate school was the close analysis of films. But I was also interested in whether one could build generalizations out of those analyses. My initial thinking ran along art-historical lines. My Ph. D. thesis on French Impressionist cinema sought to put the idea of a cinematic group style on a firmer footing, through close description and the tagging of characteristic techniques. But that approach came to seem superficial. I wasn’t satisfied with my dissertation; although it probably captured the filmmakers’ shared conceptions and stylistic choices, I couldn’t offer a very dynamic or principled account of formal continuity or change.

Watch a bunch of movies. Can you disengage not only recurring themes and techniques, but principles of construction that filmmakers seem to be following, if only by intuition? As I was finishing my dissertation, reading Russian Formalist literary theory pushed me toward the idea that artists accept, revise, or reject traditional systems of expression. These become tacit norms for what works on audiences. My reading of E. H. Gombrich pushed me further along this path. We should, I thought, be able to make explicit some of those norms. Eventually I would call this perspective a poetics of cinema.

I was assembling my own version of some ideas that were circulating at the time. In the early 1970s, several theorists floated the idea that different traditions fostered different approaches to filmic storytelling. People were seeing more experimental and “underground” work, as well as films from Asia and what was then called the Third World. Being exposed to such alternative traditions helped wake us up to the norms we took for granted. The mainstream movie, typified by what Godard called “Hollywood-Mosfilm,” seemed more and more an arbitrary construction.

People began examining films not as masterworks or as expressions of an auteur, but as instances of a representational regime. Films became “tutor-texts,” specimens of formal strategies that were at play across genres, studios, periods, and directors. Again, the French pointed the way, particularly Raymond Bellour, Thierry Kuntzel, and Marie-Claire Ropars. At the same moment, Barthes’ S/z was published in English, and it seemed to provide a model for how one might unpick the various strands of a text, either literary or cinematic. Screen magazine was a conduit for many of these ideas in the English-speaking world.

Some of my contemporaries disdained the mainstream cinema and moved toward experimental or engaged cinema. Others read the dominant cinema symptomatically, for the ways it revealed the contradictions of ideology. I learned from both approaches, but I believed that the current analysis of how Hollywood worked, even considered as a malevolent machine, was incomplete. Could we come up with a more comprehensive and nuanced account of the mainstream movie? This line of thinking was already apparent in non-evaluative studies of form and style, such as essays by Thomas Elsaesser, Marshall Deutelbaum, and Alan Williams. (3)

At some point in graduate school at the University of Iowa, between fall 1970 and spring 1973, I saw a screening of His Girl Friday. I fell in love with its heedless energy. It seemed to me a perfect example of what Hollywood could do.

In my admiration I was channeling the cultists. Rivette, in a review of Land of the Pharoahs: “Hawks incarnates the classical American cinema.” (4) Bogdanovich: He is “probably the most typical American director of all.” Richard Griffith, then film curator of MoMA, had slighted Hawks in his addendum to Paul Rotha’s The Film Till Now, but in his foreword to the Bogdanovich interview he caved to the younger generation: “Hawks works cleanly and simply in the classical American cinematic tradition, without appliquéd aesthetic curlicues.” As for HGF, in the 1963 Cahiers tribute Louis Marcorelles called it “the American film par excellence.”

Praising Hawks, and HGF specifically, was part of a larger Cahiers strategy to validate the sound cinema as fulfilling the mission of film as an art. What traditional critics would have considered theatrical and uncinematic in HGF—confinement to a few rooms, constant talk, an unassertive camera style—exactly fit the style that Bazin and his younger colleagues championed. (For more on that argument, see Chapter 3 of my On the History of Film Style.)

These niceties didn’t inform my reaction at the time. I was already primed to like Hawks, though, having caught what films I could after reading Wood et al. (During my initial summer in Iowa City, I went to a kiddie matinee of El Dorado and got Nehi Orange spilled down my neck.) On my first viewing His Girl Friday delighted me with the sheer gusto of the pace and playing. Clearly the cast was having fun. A press release sent out before the film claimed that during one scene, with Cary Grant dictating frantically to Rosalind Russell, she cracked him up by handing over what she had typed.

Cary Grant is a ham. Cary Grant is a ham. Now is the time for all good men to quit mugging. You don’t think you can steal this scene, do you—you overgrown Mickey Rooney? The quick brown fox jumps over the studio. Cary Grant is a ham.

Even discounting this tale as PR flackery, we know from Todd McCarthy’s excellent biography that Hawks encouraged competitive scene stealing and wily improvisation. Russell hired an advertising copywriter to compose quips she could “spontaneously” conjure up in her duels with Grant.

If there was a “classical Hollywood cinema”—a phrase that was in the early ’70s coming into circulation via Screen—the buoyant forcefulness of His Girl Friday embodied it. Here was a film pleasure-machine that hummed with almost frightening precision. What else do you expect from a director who studied engineering and whose middle name is Winchester?

Production for use

When I saw His Girl Friday, little had been written about it. Despite Langlois’ screenings, before the 1962 touring program, the Cahiers critics seemed to have had limited access to Hawks’ prewar work. His Girl Friday wasn’t released theatrically in France until January of 1945 (not perhaps the most propitious moment), and it apparently made no long-lasting impression on the intelligentsia. I can’t find any critical commentary on it in French writing before the 1963 issue of Cahiers.

In the United States, HGF earned Hawks a courteous write-up in the New York Times by, of all people, Bosley Crowther, (5) but it wasn’t acknowledged as an instant classic like Mr. Smith Goes to Washington or The Philadelphia Story. After the initial flurry of mostly favorable reviews, the movie seems to have been forgotten until Manny Farber’s 1957 essay, and even there it’s only mentioned in a list. Interestingly, it wasn’t screened during the 1961 New Yorker series. Robin Wood’s sympathetic but not uncritical discussion in his Hawks book of 1968 seems to have been the most comprehensive account available since the movie’s release.

At about the time Wood’s book was published, something big happened. Columbia Pictures failed to renew its copyright, and His Girl Friday fell into the public domain.

Entrepreneurs made dupe copies, in quality ranging from okay to terrible. You could rent one for peanuts and buy one for only a little more. Some of these bleary prints have been telecined and turned into the DVD versions of the film that fill bargain bins today. After I got to the University of Wisconsin, where Hawks films stoked the two dozen campus film societies, I bought a public domain print. The copy was better than average, although it lacked the fairy-tale warning title at the start. From 1974 on, I showed the poor thing constantly.

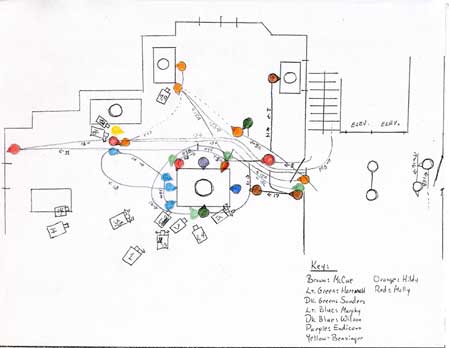

In Introduction to Film, taught to hundreds of students each semester, HGF illustrated some basic principles of classical studio construction. It had the characteristic double plotline (work/ romance), a careful layout of space, an alternation of long takes and quick cutting, manipulation of point-of-view, judicious depth framing (see frame below), and cascading deadlines. In Critical Film Analysis, I asked students to map out scenes shot by shot (see diagram above) and to show how different approaches (genre-based, feminist, Marxist) would interpret the film. In a seminar on “the classical film and modernist alternatives” HGF grounded comparisons with Bresson, Dreyer, Ozu, Godard, and Straub/Huillet. By steeping ourselves in such alternative traditions, could we resist the naturalness of Hollywood artifice?

The movie became a UW staple. It went into the first edition of Film Art (1979) as an instance of classical construction; even the telephones were scrutinized. Marilyn Campbell’s paper from our seminar was published in 1976. (6) Over the years, many of our grad students, exposed to the film in our courses, have gone on to use it in their teaching.

Doesn’t have to rhyme

I can’t let HGF go. I still use moments to illustrate points in my writing and lectures. Madison colleagues and I swap banter from it; Kristin and I talk in Hawks-code, as she explains here. I’ve been told that grad students in another PhD program compared our program to the Morning Post pressroom (favorably or not, I don’t know). Thanks to Lea Jacobs, the invitation to my retirement party was surmounted by a picture of Walter Burns whinnying into his phone.

But seriously, His Girl Friday, isn’t a bad guide to a lot of social life. You can learn a lot from its Jonsonian glee in selfishness and petty incompetence, as well as its sense that virtue resides with the person who has the fastest comeback. Think as well how often you can use this line in a university setting:

If he wasn’t crazy before, he would be after ten of those babies got through psychoanalyzing him.

I’m not claiming special credit for the HGF revival, of course. Plenty of other baby-boomer film professors were teaching it. It became a reference point for feminist film criticism, particularly Molly Haskell’s From Reverence to Rape (1974), and it has never lost its auteurist cachet. Richard Corliss’s 1973 book on American screenwriters flatly declared that “His Girl Friday is Hawks’s best comedy, and quite possibly his best film.”

Most important of all, TV stations were screening their bootleg prints. HGF didn’t become a perennial like that other public domain classic It’s a Wonderful Life, but its reputation rose. Its availability pushed the official Cahiers/ Movie masterpieces Monkey Business and Man’s Favorite Sport? into a lower rank, where in my view they belong.

Once HGF became famous, the proliferation of shoddy prints became an embarrassment. In 1993 it was inducted into the National Film Registry, which gave it priority for Library of Congress preservation. Columbia managed to copyright a new version of the film. A handsomely restored version was released on DVD, and a few years back I saw a 35mm copy whose sparkling beauty takes your breath away.

The lesson that sticks with me is this. If Columbia had renewed its copyright on schedule, would this film be so widely admired today? Scholars and the public discovered a masterpiece because they had virtually untrammeled access to it, and perhaps its gray-market status supplied an extra thrill. Thanks mainly to piracy, His Girl Friday was propelled into the canon.

Epilogue

In May of 1940, His Girl Friday hung around Madison, shifting from its first venue, the Strand downtown, to an east side screen, the Madison. The film came back in late September to yet a third screen, the Eastwood (now a music venue).

HGF was revived in March of 1941, as the second half of a double bill at the Madison (bottom left below). Check out the competition: some killer re-releases from Ford, Lubitsch, Astaire-Rogers, and Hope-Crosby. A Midwestern city of 60,000 could become its own cinémathèque without knowing it.

(1) Antoine de Baecque, Cahiers du cinéma: Histoire d’une revue, vol. 1: À l’assaut du cinéma, 1951-1959 (Paris: Cahiers du cinéma, 1991), 202-204.

(2) Bogdanovich has published a much fuller version in Who the Devil Made It? (New York: Knopf, 1997) , 244-378.

(3) Thomas Elsaesser, “Why Hollywood?” Monogram no. 1 (April 1971), 2-10; “Tales of Sound and Fury,” Monogram no. 4 (1972), 2-15; Marshall Deutelbaum, “The Structure of the Studio Picture,” Monogram no. 4 (1972), 33-37; Alan Williams, “Narrative Patterns in Only Angels Have Wings,” Quarterly Review of Film Studies 1, 4 (November 1976), 357-372.

(4) Jacques Rivette, “Après Agesilas,” Cahiers du cinéma no. 53 (December 1955), 41.

(5) Bosley Crowther, “Treatise on Hawks,” New York Times (17 December 1939), 126. “He brings to his work as a director the ingenious and calculating brain of a mechanical expert. . . . He pitches into the job just as though he were building a racing airplane.”

(6) Marilyn Campbell, “His Girl Friday: Production for Use,” Wide Angle 1, 2 (Summer 1976), 22-27.

For a helpful collection of conversations with the master, see Howard Hawks Interviews, ed. Scott Breivold (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2006). Go here for a 1970s piece by James Monaco on then-current controversies.

PS 24 Feb: Jason Mittell responds to my post with some nice nuancing and draws out the implication for copyright issues: contrary to current media policy, the wider availability of a work can actually enhance its value.

Coming attraction: Kristin is preparing a blog entry commenting on fair use in the digital age.

Our first anniversary, with a note on the unexpected fruits of film piracy

DB here:

This blog started on 26 September 2006. During its first year, it has attracted over 400,000 pageloads, over a quarter of a million visitors, and over 50,000 returning visitors. We currently average about 1000 visitors a day. While this is small potatoes by the standards of mammoth websites, it’s far more than we expected when we started. We’re grateful to all those readers who sought us out or stumbled upon us, who Googled and Yahoo’d us, who linked and listed us, who sent us corrections and extra information. And we’re grateful to our web tsarina Meg Hamel who set this up and keeps things running smoothly.

In the last twelve months, we’ve posted about 200,000 words, or enough for two books. We’ve tried to make most entries as attentive to ideas and information as what we’d write for a print publication—if not a scholarly book, at least a mainstream article. Kristin and I think of our blog as a sort of column, published in a magazine we edit, with no length restrictions, no assigned topics, and as many pictures as we like. It’s been fun to write more informally than we usually do. We’ve also been able to call attention to regional and national cinemas (e.g., Hong Kong, Denmark, New Zealand) we think deserve more attention. We can also pursue topics that we couldn’t fit into larger research projects, like Kristin’s interest in the Lord of the Rings franchise and my curiosity about alien autopsies.

While the blog originally aimed to supplement Film Art: An Introduction, we think that the best way to do that is to keep reminding our readers that the world of film is dazzling in its diversity and unpredictability. One commentator said that our blog was aimed at students and nonspecialists, but we find that many professional film scholars and film journalists check on us. Perhaps that’s because we wander where we like, from very old films to recent films we see at multiplexes and festivals, and we propose ideas that could be considered more closely and researched more exactingly. One correspondent said that many of our entries could be the basis for research articles. Maybe, but we have more ideas than we can ever write up systematically, so off to the blog they have gone. In addition, we’ve sometimes used the blog to extend or supplement things we’ve published in books and articles.

Looking back at what we’ve done, I notice some recurrent themes.

*In keeping with the blog’s title, we emphasize film as an art form. More specifically, we’re especially interested in how structure and technique work together, which few blogs outside the industry do. For instance, most online critics have concentrated on praising or condemining The Brave One, and in rather general terms. If we wrote about it, we’d probably focus on the effects of its alternating points of view, its use of the four-part script structure, and its recourse to oddly rocking camera movements to convey Erica’s disorientation at crucial moments (and trace how those develop in patterned ways across the film). That is, we’d incline toward somewhat finer-grained analysis of cinematic storytelling, even if that means going shot by shot. If we want as well to make an evaluation of the film, as we sometimes do, we then have some concrete evidence to back it up.

*We also treat film art as tied to film commerce—both the mainstream industry and the less-acknowledged form of commerce known as film festivals. We’ve always believed that there isn’t necessarily a battle between film as an art form and “the business.” Much of our published work, including Kristin’s Exporting Entertainment and my work on Hong Kong film and contemporary Hollywood, as well as our collaboration with Janet Staiger on The Classical Hollywood Cinema, tries to trace out ways in which funding affects the look and feel of the finished work. Money matters!

*We’re happy to find that a lot of filmmakers read and link us. One of the purposes of Film Art was to show how artistic expression in cinema is tied to practical decisions made by filmmakers; that’s why we begin the book with an overview of the process of film production. In our academic work as well, we’ve been more inclined than most scholars to interview filmmakers, to read technical journals, and to study how craft practices create artistic effects. We’ve developed friendly relations with Asian filmmakers like Johnnie To and American filmmakers like Mark Johnson and James Mangold. We’ll continue to discuss how technique, technology, and filmmaking traditions interact in cinematic expression.

*We’ve tried to deflate some clichés of mainstream film journalism. Writers of feature articles are pressed to hit deadlines and fill column inches, so they sometimes reiterate ideas that don’t rest on much evidence. Again and again we hear that sequels are crowding out quality films, action movies are terrible, people are no longer going to the movies, the industry is falling on hard times, audiences want escape, New Media are killing traditional media, indie films are worthwhile because they’re edgy, some day all movies will be available on the Internet, and so on. Too many writers fall back on received wisdom. If the coverage of film in the popular press is ever to be as solid as, say, science journalism or even the best arts journalism, writers have to be pushed to think more originally and skeptically.

*There’s the theme we might call the continuing presence of the past. I notice that many of our entries comment on a current event or topic by showing that it has parallels and precedents in earlier periods of film history. This isn’t, I hope, showoffishness or academic point-scoring or a bored conservatism. Often this historical awareness allows us to correct hype and nuance ideas. Yes, today’s cinema experiments with flashbacks and intersecting story lines; but these are formal strategies we find in earlier periods of filmmaking too. So the interesting questions become: How are today’s strategies different? Why do these traditions get reinvented now? What consequences do they yield in our current circumstances? Rather than celebrating apparent innovation, it’s more exciting to see how filmmakers connect to tradition, shaping it in ways that even they might not be aware of doing. We tend to see the present through a narrow window, but historical awareness widens and deepens the view.

We rethink our project from time to time. Regular readers will notice that we’ve just added a roll of Readers’ Favorite Entries, on the right. We’ve also talked about adding a podcast to the site. In any event, we look forward to another year of our little magazine, and we have a folder full of ideas that we hope will tantalize you.

I’m off to Vancouver to cover the festival, as I did a year ago. More information on its wonderful lineup is here. In the meantime, some dessert.

Piracy ahoy

In Shanghai a few years ago I visited a shop selling pirated DVDs. Two illegal titles caught my eye.

According to the Motion Picture Association of America, the trade association of the major Hollywood companies, all pirated editions have their origin in camcorder copies made during screenings. In other words, it’s those outlaw consumers ripping us off.

But a large part of piracy can be traced to people working inside the industry. A common source is the raft of DVD screeners sent out to Academy members during awards season. It has proven impossible to keep these discs from getting into the hands of pirates. Other bootleg copies come from inside the production and distribution companies. Famously, a copy of Bulletproof Monk surfaced in China before the final cut was made; it’s widely believed that an employee leaked it. With so many special-effects houses working on a film in postproduction, it’s not difficult for one keyboard jockey to upload a working copy to the Darknet. Hence all those time-coded versions of the Star Wars saga that made their way into eager fans’ hard drives.

Further evidence of this tendency comes from the first Shanghai DVD I examined, that of The Passion of the Christ, not then available legally anywhere. It was a curious copy. It was an auditorium version, as pirates call movies snagged during a screening. The color and resolution were poor, and the camera zoomed in during the credits to a 1.75 ratio, wrecking the anamorphic compositions and creating closer framings.

Poor as it was, the bootlegged disc lacked some of the usual problems. The image was stable and centered, with no sign of being filmed from a seat in the house. The sound wasn’t tinny or boomy, as it would be if it came from theatre speakers, but it was plagued with whistles and dropouts.

I concluded that this was a version made by a projectionist in off-hours. He or she had time to set up the camera on a tripod near the back of the house and record the whole film without distraction, using an iffy sound feed. But what was more puzzling was the fact that the print being screened had no subtitles.

So what I was seeing was an early version, before any subtitles had been put on. The projectionist wasn’t your local multiplex employee but someone in the postproduction process. In a way, however, this bootleg copy fulfills Mel’s dream. As the film began shooting Mel claimed:

Obviously, nobody wants to touch something filmed in two dead languages. They think I’m crazy, and maybe I am. But maybe I’m a genius. I want to show the film without subtitles. Hopefully, I’ll be able to transcend language barriers with visual storytelling. If I fail, I’ll put subtitles on it, though I don’t want to.

On the bootleg DVD you could add Chinese titles or barely comprehensible English ones. Of course once the official DVD version came out, you could turn all subs off, but for a moment the bootleg market had given us Mel’s vision pure.

The second DVD that caught my eye points up another unexpected consequence of piracy. The cover of the release is at the very top of today’s entry. What made me investigate was the fact that Michael Caine is listed as being in the movie twice (though with different Chinese characters giving “his” name). Even the eager young researcher of PCU, immersed in the oeuvres of Gene Hackman and Michael Caine, might want to add a paragraph about this movie.

The credits on the back of the package add to the confusion. They are for Disney’s The Kid, and the running time is listed at 2:49. (The Kid is only 104 min.) I later learned that The Kid is a default paste-in on many DVD backsides. Why reproduce several different credit lists when all that matters is the metamessage, “This is an American movie”? But if it’s a Disney film, why does the printing also provide the Universal logo and an R rating?

So I broke down and watched the movie. (Flawless copy, by the way.) It is Code 11-14, a 2001 TV movie by Jean de Segonzac (big clue on the cover). An LA cop is tracking a serial killer. The killer follows the cop and his family onto a passenger jet and terrorizes them. According to Hal Erickson’s All Movie Guide, CBS pulled it from the schedule in the wake of 9/11. It wasn’t broadcast until 2003. Code 11-14 stars David James Elliott, Nanci Chambers et al., but not Michael Caine.

These sorts of mind games are pleasant. It’s fun to be thrown off balance by guessing how the credits got scrambled (PhotoShop set to Random?) and why Mr. Caine is credited doubly. Is he twice as popular in China as any other actor?

But the strongest justification for the existence of this pirate copy seems to me the liner notes.

What you see on the cover above—England movie circles cluster animportant history for but moving—is but a foretaste of what you find on the back. I reproduce it word for word.

This large war movie, empty cluster in the movie circles elite of England but move, for re-appear their motherland atAn important history of the period of World War II but worker harder, the film to record theatrical breeze The space describes the German Nazi in 1910 got empty bomb British intensive metropolis, make England Lose miserably heavy, but also arose England people together enemy spirit to make Germany, in numerous Popular actor inside, exceed the gram. The boon of . The willing to thinks, the shares the drama more, play the cuckoldry of The jade of Susan then expresses romantic, in addition, the Lawrence the brilliant jazz in military tactics with, the plays the plays the heartless condition in hungry clap very sublime and lifelike.

Exactly. I rest my case.

PS 30 Sept: I should’ve realized there’d be a website devoted to maniacal pirate prose and pictures. Thanks to Stuart Ian Burns, I learn that you can find many more at a Flickr group called, logically, crappy DVD bootleg covers.