Area Man Lives in Fear that Attractive Woman Will Ask What’s on His iPod

Tuesday | October 31, 2006 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

I’ve enjoyed Steven Levy’s technology books since Insanely Great, his (highly favorable) history of Apple. His newest one, The Perfect Thing: How the iPod Shuffles Commerce, Culture, and Coolness is a smooth ride, letting us in on the creation of the gadget, the rising power of iTunes, and the mesmerizing mystery of iPodolatry. I learn from Levy that people dress up their iPods, mourn their passing when the batteries die, and use them to meet strangers.

I was dimly aware of this last winter. I was sitting in my office and saw a young guy in the hall outside waiting for a class to start. He was watching a video on his pod and two young women came up to him. “Oooh, is that a fifth-generation iPod?” He showed it to them, and soon going out for coffee with them took precedence over going to class.

iPods invaded our house in two waves. Kristin goes to an Egyptian dig site in Amarna every year, mostly to work on registering statuary fragments, and as soon as she learned of Steve Jobs’ latest brain child, she wanted one. Now she could listen to her favorite music while standing for hours at a work table. I gave her a first-gen iPod for Christmas, and our computer assistant Brad Schauer helped her load it up with Handel, Mozart, and Vivaldi, mostly operas. She’s taken it over with her on every trip since.

I had no interest in listening to music as I moved through the world. I had tried a DiscMan long ago, but I didn’t like feeling insulated from the sounds around me. During travel, especially plane trips, I read. But when the video iPod came along, I thought that it had possibilities, so last winter I got one, the big mama with lots of GB.

By having Brad load Kristin’s baby, I now realize, I missed part of the fun: picking out what you’ll put on and arranging items into playlists. I also met with frustration. I hadn’t realized the dominance of pop music as a paradigm for all music until I bumped into iTunes. Of course it had no trouble with my boomer tracks (Burt Bacharach, the Drifters, Sam Cooke, etc.). But the program didn’t like art music. It chopped up operas so that little gaps appeared between tracks that should flow seamlessly, and it couldn’t read my old and obscure CDs. At one point, iTunes decided that all my Sibelius symphonies should be arranged by movement, so it grouped together seven first movements, seven second movements, and so on.

Reinstalling and upgrading the program, as well as setting up playlists, eventually solved these problems. Now my Mahler plays seamlessly and my Björk has the right pauses between songs. I still listen more seldom than most podders; not when walking around the world, mostly just in airports or in hotel rooms. More enticing has been the video function.

I’m a purist about moving images. I like movies on big screens, and grudgingly accept watching them on a tv monitor for convenience. I don’t much care for the look of images in home theatres; a lot of people, having invested so much in these behemoths, seem unable to see how mushy and artifact-ridden their systems are. (When I complained to a friend, he responded: “I like video artifacts the way you like grain.”) I often use a TV or computer monitor to study a film, but I very seldom watch a movie for the first time on a computer or other tiny display.

But my video iPod…well, I don’t love it or worship it, but I do admire and respect it and like to hang around with it.

Part of the attraction is, as Levy talks about at length, is the cool mystique of it. It is a good object. Its subtle heft and operating ease make it a pleasure to fondle. Then too, the very idea of it is entrancing. How can something so small store so many things that matter so much to us? But there’s another factor at work in the video iteration. I think that iPods also make the film viewing experience intimate in a way that other media don’t.

Levy talks about how Sony erred when it built two earphone jacks into the first Walkman. Morita believed that people would want to share the music with a friend. Wrong. Levy points out that it was all about privacy, about enclosing you in a bubble cut off from social interaction. Likewise, nobody can really watch your video iPod with you. It’s a little world addressed to you alone.

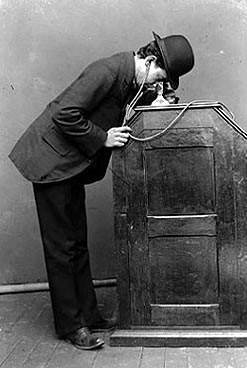

iPod version 0.0

In some ways we’re going through a period in which our audio-visual media are looking back to earlier forms. With multiplexes and Imax, big screens and 3-D presentations have returned in force; you’d think it was 1953 again. Similarly, the iPod rediscovers the Kinetoscope, Edison’s early peephole film system. Most were silent, but some were equipped with sync sound. You plugged in earphones, peered through a slot, and cranked a long film loop through. It was an arcade attraction without much of a future; large-scale success came to the system that projected images for a crowd. Now, however, we can have a portable Kinetoscope, and the fact that it’s at our command (stop, go back, skip over, shuffle) probably makes it all the more mesmerizing.

For the most part, I don’t watch fiction films on my iPod. I watch documentaries, most repetitively Adam Curtis’s The Power of Nightmares, one of the great docs of recent years. I don’t watch TV at home, but I catch up with shows like The Shield and The Wire via my iPod. I watch some YouTube clips, especially the Two Chinese Students (aka Back Dorm Boys), which always give me a lift.

But I confess I’ve also put on films that work, for me, like favorite music. These are films I know well and love to look at in idle moments. I play the reconstruction of Eisenstein’s Bezhin Lug, with stirring Prokofiev audio extracts; Les demoiselles de Rochefort; Feuillade’s Fantomas; Akerman’s Golden 80s; Lang’s Spies; episodes of Twin Peaks. Except for the Demy, all fit nicely in the 3×4 window. All lift my spirits.

Cooler people download Lost or store their pictures or swap playlists with others, but my needs are more prosaic. This digital version of peephole cinema supplies me with comfort food.