Wisconsin Film Festival: Retro-mania

Tuesday | April 4, 2017 open printable version

open printable version

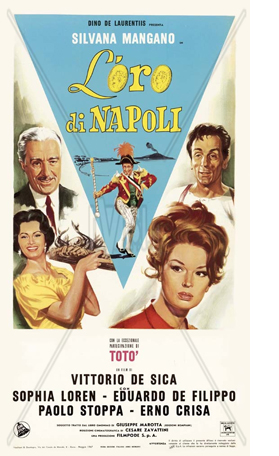

The Gold of Naples (L’oro di Napoli, 1954).

DB here:

With the growing popularity of subscription streaming services, I suspect that film festivals will need to amp up their retrospective offerings. I was very surprised that a good film like I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore, which would in earlier years have played arthouses, had no theatrical release. Despite its acclaim at Sundance, it went straight to Netflix online. True, Amazon has shown great willingness to port its high-profile titles to big screens. But by and large, as Netflix, Amazon, and other services produce and buy up new films, I suspect that festival premieres of indie titles will become more and more a display case for streaming. See it this week at our festival, and next month online!

It must be dispiriting for filmmakers hoping for theatrical play. Yet this crunch may oblige festival programmers to emphasize archival and studio restorations. These rarities are unlikely to show up on streaming any time soon, and festival screenings can build a public for them—so that they may eventually come to DVD or subscription services.

Case in point: Several restored titles at our Wisconsin Film Festival drew sellout crowds.

AMPAS comes through

To my regret, I didn’t catch the Academy Film Archive restoration Across the World and Back, a collection of global adventures of “the world’s most traveled girl,” the self-named Aloha Wanderwell. Her 1920s and 1930s footage, which included record of the Taj Mahal and the Valley of the Kings, was introduced and commented on by Academy archivist Heather Linville. Everybody I talked to loved it. Go to AMPAS for many clips and pictures.

To my regret, I didn’t catch the Academy Film Archive restoration Across the World and Back, a collection of global adventures of “the world’s most traveled girl,” the self-named Aloha Wanderwell. Her 1920s and 1930s footage, which included record of the Taj Mahal and the Valley of the Kings, was introduced and commented on by Academy archivist Heather Linville. Everybody I talked to loved it. Go to AMPAS for many clips and pictures.

I did manage to squeeze into another Academy restoration, Howard Hughes’ Cock of the Air (1932). The film amply showcases Hughes’ two principal concerns, aviation and the female mammary glands. (I guess technically that makes three concerns.) It’s a minor-key Lubitsch switch in which priapic flyboy Chester Morris pursues sexy Billie Dove, who’s resolved to bring his ego crashing to earth. We get lots of nuzzling, murmured double entendres, and scenes of passion quickly doused by the woman’s coquettish withdrawal. I thought the plot thin, needing a romantic rival or two, but the leering pre-Code stuff is good dirty fun. The high point comes when Billie encases herself in a suit of armor and Chester arms himself with a can opener.

The direction is credited to Tom Buckingham, a lower-tier artisan, but it seems possible that parts of the film were handled by Lewis Milestone, who contributed the original story. The first couple of reels are very flashy, with odd angles, complicated tracking shots, and bursts of rhythmic editing. They’re typical of Milestone’s showy, sometimes showoffish, style in All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) and The Front Page (1931; also shown at WFF).

Cock of the Air encountered heavy censorship, with the can-opener episode entirely snipped from the release version. The Hays Office even provided local censor boards with guidance for further cutting. When Heather discovered a pre-censorship print at the Academy—an exciting find—she discovered that the offending footage was there, but the soundtrack portions were lost.

Heather proceeded to hire actors to voice the parts in accord with the script and the onscreen lip movements. The results are sonically smooth, but in the spirit of fair dealing, the bits of replacement are marked with a discreet bug in the lower right corner of the frame. This is a nice piece of archival integrity. Heather also showed an informative short on the restoration of this engaging piece of naughty early sound cinema.

Of incidents and non-incidents

The Incident (1967).

Two other pieces of film history got fitted into place with the revival of Larry Peerce’s One Potato, Two Potato (1964), a classic of American social-problem cinema, and the rarer The Incident (1967). This latter glimpse of mean streets creates what screenwriter David Koepp calls a Bottle, a tightly constrained space in which the drama plays out. Here the Bottle is a subway car in which several people, a cross-section of New York life, become the playthings of two young thugs, played by Tony Musante and Martin Sheen.

Starting by gay-bashing and culminating in a charged racial confrontation, the subway conflicts sought to show how the solid citizens can’t summon the will to respond collectively—even when they take their turn under the thugs’ lash. It was intended as a response to the infamous murder of Kitty Genovese, whose screams were mostly ignored by her Queens neighbors. (A recent documentary, The Witness, revisits the case.)

The plot is provocative enough, but the manner of filming, evocative of cinéma-vérité, drives every moment home. Forbidden to film on the subway system, director Larry Peerce and ace cinematographer Gerald Hirschfeld (Cotton Comes to Harlem, Young Frankenstein) had to rely on sets, except for shots snatched with hidden cameras. But what a set they had for the subway car. Peerce explained in an energetic Q & A that the car was built to five-sixth scale, with no wild walls. It forced the players to interact in a cramped, pressurized atmosphere.

The plot is provocative enough, but the manner of filming, evocative of cinéma-vérité, drives every moment home. Forbidden to film on the subway system, director Larry Peerce and ace cinematographer Gerald Hirschfeld (Cotton Comes to Harlem, Young Frankenstein) had to rely on sets, except for shots snatched with hidden cameras. But what a set they had for the subway car. Peerce explained in an energetic Q & A that the car was built to five-sixth scale, with no wild walls. It forced the players to interact in a cramped, pressurized atmosphere.

A believer in improvisation, Peerce rehearsed different groups of actors separately, then brought them together to let some natural friction emerge. He encouraged them to add to the script and build immediate reactions—so immediate that Thelma Ritter, a veteran unused to improv methods, responded to Musante’s goadings by slapping him. All this is captured in a superheated style of fast cuts, big close-ups, and screeching sound. It’s a white-knuckle ride that retains its power. I hadn’t seen it since 1970, but the violent climax, utterly earned, is disturbingly contemporary. The film’s final moments are being replayed, in reality, all over America as you read this.

The nicest surprise of my retrospective viewing was The Gold of Naples (1954). Studded with big names (Ponti and De Laurentiis, Totó and de Sica, Silvana Mangano and Sophia Loren), it has sometimes been thought to be one of those lightweight Italian comedies that represent a quiet refusal of the Neorealist impulse. On the contrary, it proves to be a bold contribution to block construction, here in the omnibus genre. Several stories are laid end to end, exemplifying the vivacity and poignancy of life in Naples’ back alleys.

One story has a tight, shocking arc: the tale of a prostitute (Mangano) who thinks she’s marrying for love until she learns her new husband’s guilt-ridden sadomasochistic motives. The finale is a scrappy anecdote, in which The People give a local plutocrat the ultimate vocalization of disrespect.

But some episodes, taken as conventional stories, are oddly off-center. A wife (Loren, bursting out of her blouse and skirt) has lost a ring in a torrid encounter with her lover. She finds it again, and no harm done. The search for it is a pretext for sampling other lives. Or: A penniless count addicted to gambling is reduced to playing cards with an exceptionally lucky neighborhood kid. He learns no lesson, the kid is bored with winning, and all is as before. More disquieting: A family bullied by a rich man who has moved in with them finds a way to kick him out, but there’s little sense of triumph. He remains unbowed, and manages to spoil their celebration of his eviction. Most scripts would let us enjoy his comeuppance, but here we’re left with the cowering family, which has become so unused to freedom that they may not know what to do next.

But some episodes, taken as conventional stories, are oddly off-center. A wife (Loren, bursting out of her blouse and skirt) has lost a ring in a torrid encounter with her lover. She finds it again, and no harm done. The search for it is a pretext for sampling other lives. Or: A penniless count addicted to gambling is reduced to playing cards with an exceptionally lucky neighborhood kid. He learns no lesson, the kid is bored with winning, and all is as before. More disquieting: A family bullied by a rich man who has moved in with them finds a way to kick him out, but there’s little sense of triumph. He remains unbowed, and manages to spoil their celebration of his eviction. Most scripts would let us enjoy his comeuppance, but here we’re left with the cowering family, which has become so unused to freedom that they may not know what to do next.

Above all, in an episode cut from the original American release (and missing from this poster, though at the top of today’s entry), a mother follows her son’s coffin driven through the street. She throws wrapped candies for children to pick up. That’s it. No flashbacks to life with her boy, no dialogue telling us how he died, no colorful secondary characters to provide that life-goes-on final note. It could be called “The Incident,” though nothing more unlike the fever-pitch drama of Larry Peerce’s film could be imagined.

According to screenwriter Cesare Zavattini, a Hollywood producer once told him:

“This is how we would imagine a scene with an aeroplane. The plane passes by. . . a machine gun fires . . . the plane crashes. And this is how you would imagine it. The plane passes by. . . The plane passes by again… The plane passes by once more…”

He was right. But we have still not gone far enough. It is not enough to make the aeroplane pass by three times; we must make it pass by twenty times.

And, Zavattini seems to suggest, the machine gun should never fire.

The lack of a dramatic peak, to which a normal scene would build, can force our attention to downshift to the minutiae of moment-by-moment action, or rather micro-action. That’s what happens in this sequence of The Gold of Naples, which Zavattini helped write. Every gesture and glance becomes potentially, but ambiguously, significant. De Sica’s patient recording of a very thin slice of life is as radiantly unpretentious a model of “pure Neorealism” as anything to come from the 1940s.

This is just a glimpse of the delights among the 150 screenings that are gracing our eight-day film festival. (We’re now the largest university-sponsored festival in the country, though probably not in budget.) Details of this magnificently programmed affair are here. We’ll blog again soon.

Thanks to the programmers Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, and Mike King, along with all the institutions, wise elders, community supporters, and volunteers that make WFF fun. You can browse earlier reportage from this event here.

You can also see the restored Front Page (1931) in Criterion’s new His Girl Friday DVD release. On Cock of the Air’s censorship travails, see the AFI site. It will be screened very soon at the TCM Festival. Also set for the TCM festival is The Incident, which will screen later in April at Film Forum. Mike Mashon gives more information on Aloha Wanderwell in his LoC blog.

How wrong I was to miss booking The Gold of Naples when I ran a film club in college and good old Audio-Brandon offered it. Even without the funeral scene and the up-yours finale, it would be worth seeing. Now no version seems available in the US; WFF director Jim Healy brought a print from Italy. It would be perfect for FilmStruck.

Read…watch movie…grab food…read…watch movie…