Archive for November 2009

Things we like of late

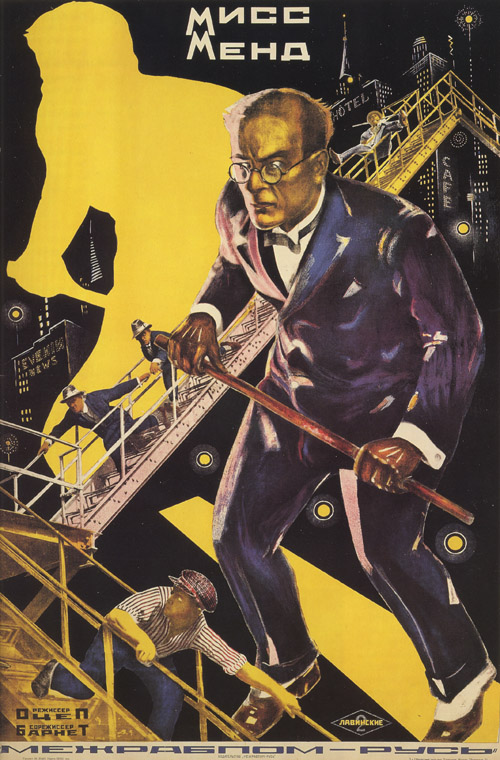

One of several posters the Stenberg brothers designed for Miss Mend.

We’ve been quite busy in the tail end of October. David sweated over a Bresson essay, started on his online version of Planet Hong Kong, and continued to help out in Lea Jacobs’ seminar on film stylistics. Kristin has started organizing a book about the statuary from the site in Egypt where she works for three weeks each year. And both of us have been steering the ninth edition of Film Art: An Introduction through the final phase of production. So instead of a blog essay this week, we offer some items from recent months that we think deserve wider notice and in some cases a pat on the back.

In our second report from the Vancouver film festival, Kristin wrote about a Chilean film, The Maid. She suggested that it was entertaining enough to be remade in English as a vehicle for an actress willing to play middle-aged and curmudgeonly. On October 16, the film was released theatrically. Starting in one theater, then going to six, and now 13 in its third week, it’s doing pretty well judging by per-theater averages. It’s not likely to get beyond big-city arthouses, but at least a release means that it should come out on DVD.

Speaking of DVDs, German silent cinema continues to be well-served with two new releases from British firm Eureka! F. W. Murnau’s 1922 film Phantom was already available in the US on the 2006 disc from Flicker Alley. The new Eureka! set includes both Phantom and Die Finanzen des Grossherzogs (1924). We saw the latter years ago at the National Film Theatre in London. It’s a comedy, and it struck us that Murnau was a bit ill at ease in that genre. Still, any Murnau film is worth a look. The set contains commentary on Die Finanzen by David Kalat, and there’s an essay on both films by Janet Bergstrom.

Speaking of DVDs, German silent cinema continues to be well-served with two new releases from British firm Eureka! F. W. Murnau’s 1922 film Phantom was already available in the US on the 2006 disc from Flicker Alley. The new Eureka! set includes both Phantom and Die Finanzen des Grossherzogs (1924). We saw the latter years ago at the National Film Theatre in London. It’s a comedy, and it struck us that Murnau was a bit ill at ease in that genre. Still, any Murnau film is worth a look. The set contains commentary on Die Finanzen by David Kalat, and there’s an essay on both films by Janet Bergstrom.

One of the best arguments that sequels and series, even those about super-villains out to rule the world, aren’t necessarily bad is Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse films. They span almost the length of his directorial career, from the two-part serial Dr. Mabuse der Spieler in 1922 through Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse in 1933, up to his last but definitely not least film, Die 1000 Augen des Dr. Mabuse (1960), which David included in his Belgian summer course. For those who can’t get enough of this arch-fiend and his followers, Eureka! has packaged all three in a new boxed set. There are numerous extras, which you can read about here. For those who have only seen The 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse dubbed in English, this set gives the option of German with subtitles or dubbed. (The films are not available from Eureka! separately.)

The films of Lev Kuleshov pupil Boris Barnet are only gradually being discovered outside Russia. One of the hits of this year’s “Il Giornate del Cinema Muto” was his 1928 comedy, The House on Trubnaya. Yes, there were Soviet Montage comedies, and this is one of the funniest. Let’s hope an enterprising company brings it out on DVD.* In the meantime, Flicker Alley is doing its bit to make Barnett known by releasing his 1926 three-part serial, Miss Mend. We saw it years ago without subtitles, so we look forward to finally finding out exactly what this fast-paced thriller is about. Something anti-capitalist involving the “Rocfeller and Co.” factory.

Soviet film was much on our minds this semester because our Cinematheque was running a series of films by Grigori Alexandrov. Probably best known for collaborating on Eisenstein’s silent films, Alexandrov came into his own in the 1930s with a series of lumpy but ingratiating musicals. They run the gamut from slapstick to mild satire (of familiar targets like bureaucrats). He likes silly gags, direct address to the audience, and a sort of relentless jollity that seems designed to prove Stalin’s claim in those years of privation that “Life has become gayer, comrades, life has become more joyous.”

Jolly Fellows (aka Jazz Comedy, 1934) is a somewhat labored effort in Marx Brothers absurdity, while Bright Path (1940) gives us a Stakhanovite Cinderella. It’s full of special-effects trickery used for comic effect, as when a poster coyly comes to life.

Although Alexandrov helped bring Hollywood production values to Soviet cinema, his 1936 Circus is a pointed critique of American racial bigotry.

Alexandrov’s best known film is Volga Volga (1938), reportedly Stalin’s favorite movie. It’s a meandering tale enacting the battle of highbrow music and popular tastes, including a clever scene (perhaps derived from the “Isn’t It Romantic?” number of Love Me Tonight) in which the movie’s principal tune jumps from boat to boat down the river, until it has become an unofficial national anthem. The films star Alexandrov’s wife, Lyubov Orlova, whose bullheaded energy swamps all resistance. The series is from a touring program, Red Hollywood, and you can read the background here.

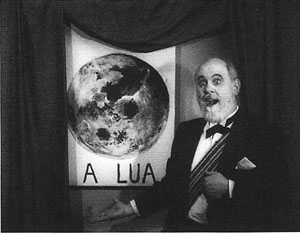

Wisconsin Bioscope silent films went south in August–specifically, to São Paulo’s third Brazilian Days of the Silent Cinema. Here at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Dan Fuller, a photographer and historian of photography, teaches students to use classic cameras and devise their own 1910s movies. Of the two Bioscope films chosen for the São Paolo festival, A Expedição brasieira de 1916 (2006) depicts the first earthlings’ arrival on the moon. It features a stirring performance by a novice actor (above) whose film career was tragically cut short when he decided to become a professor.

Cinema in yet another land is the subject of Research Guide to Japanese Film Studies by Abé Mark Nornes and Aaron Gerow. At its center is a robust bibliography, including journals as well as books, but there’s much more: a survey of archival collections of films and documents, a list of film distributors, a gathering of online resources, and even a list of bookstores specializing in Japanese cinema. Donald Richie calls it “a reference work which both illuminates and defines this field, clearing a formerly obscured terrain for future scholarship.” Markus and Aaron are strong participants in a tide of younger scholars, both Asian and Western, who are rethinking this very important national cinema.

Images, not moving, come at you in another package. Remember Viewmasters? Vladimir, a projectionist at the Northwest Film Center in Portland, makes handsome viewmaster-style discs presenting strange tales culled from Kafka, Calvino, and less-known sources. The images are still-lifes incorporating toys and props, and it’s up to you to figure out the narrative. Concept sometimes outruns execution, but the shots suggest a childhood world turned sinister. You can even get your own viewer–called, naturally, a Vladmaster.

Images, not moving, come at you in another package. Remember Viewmasters? Vladimir, a projectionist at the Northwest Film Center in Portland, makes handsome viewmaster-style discs presenting strange tales culled from Kafka, Calvino, and less-known sources. The images are still-lifes incorporating toys and props, and it’s up to you to figure out the narrative. Concept sometimes outruns execution, but the shots suggest a childhood world turned sinister. You can even get your own viewer–called, naturally, a Vladmaster.

At Parallax View, Sean Axmaker is building an online archive of the complete run of the legendary magazine Movietone News. Richard T. Jameson and Kathleen Murphy are leading voices in American film criticism, but I suspect that the younger generation isn’t as aware of them as it should be. In Movietone News and elsewhere they provide a body of criticism that nicely balances judgment, information, and ideas. Hats off to Jim Emerson for using Halloween as an occasion to point up Richard’s astute observations on modern shot design.

On Sunday night we went along with Jeff Smith to a campus lecture by Steven Pinker. The talk was a condensation of Pinker’s book The Stuff of Thought, a fascinating effort to show how various dimensions of language, chiefly semantics and pragmatics, reflect basic concepts of space, time, causality, and social relations. Language, Pinker says, furnishes a window into human nature. In a virtuoso turn, the book wraps up two trilogies at once: it caps a pair on cognitive and evolutionary theory (How the Mind Works and The Blank Slate) and a pair on grammar and semantics (The Language Instinct and Words and Rules).

On Sunday night we went along with Jeff Smith to a campus lecture by Steven Pinker. The talk was a condensation of Pinker’s book The Stuff of Thought, a fascinating effort to show how various dimensions of language, chiefly semantics and pragmatics, reflect basic concepts of space, time, causality, and social relations. Language, Pinker says, furnishes a window into human nature. In a virtuoso turn, the book wraps up two trilogies at once: it caps a pair on cognitive and evolutionary theory (How the Mind Works and The Blank Slate) and a pair on grammar and semantics (The Language Instinct and Words and Rules).

David first heard Pinker speak at an at extraordinary conference in Santa Barbara in August 1999. Coordinated by Leda Cosmides and John Tooby, “Imagination and the Adapted Mind” was an effort to explore how the arts could be illuminated by contemporary psychology, particularly one informed by an evolutionary perspective. This event–featuring not only Pinker but also Mark Turner, Eleanor Rosch, Ellen Dissayanake, Don Browne, and other luminaries–was a major moment in bringing “evolutionary aesthetics” to the table, although it’s taken about a decade for most humanists to catch up. (Several of the papers are available in a double issue of SubStance.) It was at that event that Pinker made his notorious suggestion that art was a byproduct of the brain’s evolution, a sort of “mental cheesecake” designed as a compact “superstimulus” appealing to our senses, mind, and emotions.

David had read The Stuff of Thought when it came out and had viewed the talk online. Sunday’s lecture remained a compelling performance, packing a remarkable number of ideas, data, and vivid examples into an entertaining seventy-five minutes. Pinker has been called the Dawkins of linguistics and cognitive psychology, but his sense of humor is rowdier. His straightfaced analysis of swearing is lively enough on the page, but it’s uproarious live.

Finally: Ever notice how many classic kung-fu movies are in widescreen? David has posted a new online essay tracing how Shaw Brothers popularized the anamorphic format in Hong Kong. The essay also considers how the widescreen format led Hong Kong filmmakers toward a distinctive approach to composition, cinematography, and dynamic movement. . . . of which the image below is a fair instance.

*[Nov 5: Thanks to James Steffen for alerting us to the fact that Edition Filmmuseum is bringing out The House on Trubnaya, along with Barnett’s other silent comedy of the same period, The Girl with the Hat Box, soon. There’s an impressive list of films in preparation, including the rare Expressionist classic Von morgens bis Mitternacht (1920), by Karl Heinz Martin. Comedy lovers should key an eye open for the release of a collection of Max Davidson’s hilarious silent comic shorts, including, we presume, the immortal Pass the Gravy.

Variety also has announced that Sundance is going national. On January 28, 2010, eight filmmakers will present their films and hold Q&As in eight theaters across the U.S.A. Madison, with one of only two Sundance multiplexes in the country, will be one of the host cities.]

Return to the 36th Chamber.