Title wave

Thursday | September 11, 2008 open printable version

open printable version

The very first drafts of the outline always had Cloverfield on them. . . . Cloverfield was what I always wanted to call the movie. . . . It’s a terrible title . . . if you’re trying to sell something, who the hell’s gonna go see that?. . . But it’s cool. There’s a reason. I could state the reason, but it’s very clear it is meant to be obtuse. I believe that the film answers why it is called Cloverfield, I believe that it’s in the film, I believe that you can make that argument. It says exactly what I want it to say. But it’s very clear that we don’t want to explain it.

Screenwriter Drew Goddard, at Creative Screenwriting podcast

DB here:

Don’t think about a movie title too long. Even a familiar one can turn strange before your eyes.

This was brought home to me long ago when I showed Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan in a course. Before the film started, a student asked me, “Who is it?” I didn’t understand. “I mean, who is her fan?” It never occurred to me to take the title this way, but actually in the movie Lady W does attract a big fan.

Titles can be explicit, but they’re often metaphorical, associative, and oblique. Sometimes they’re downright obscure. But as Drew Goddard says, they can be cool.

Don’t Worry, We’ll Think of a Title (1966)

The least provocative titles are based on the protagonist’s name: Brubaker, Anthony Adverse, Erin Brockovich, Norma Rae, Speed Racer. One step removed is the title that describes the protagonist’s job or role: Gladiator, Hitman, The Cable Guy, Bob le flambeur, perhaps also The Godfather. Then there are the titles, like The Last Action Hero or Prince of Players or Little Caesar, that characterize the protagonist more figuratively.

If the movie has a pair of protagonists, the title can reflect that, as in David and Bathsheba, Pete’n’Tilly, and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. When the title elevates a secondary figure, as in Melvin and Howard or Harry and Tonto, it has the effect of making us consider the relationship between the two as central to the action. When there are several main characters, we can get a title characterizing the group, not just Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice but The Professionals and The Breakfast Club.

Things get a little more curious when the title focuses on a character other than the protagonist(s). Rebecca identifies a dead character, but her aura haunts the (unnamed) heroine. Both versions of The Man Who Knew Too Much refer, at least literally, to a minor figure. Why is The Wizard of Oz not called Dorothy Goes to Oz? Why does Mizoguchi’s great Sansho the Bailiff take its title from the name of the villain? It’s not as if Mizoguchi was trying to do an Ian Fleming (Dr. No, Goldfinger).

Perhaps Wizard and Sansho bear their titles because they’re adapted from literary sources that had those titles. But that just pushes the problem back a step: Why do the originals have these titles? And in asking why, I’m not asking for information about what went on in an author’s mind or a story conference. The why question here is about purpose and function. What does the title do in relation to the film’s plot or theme?

For instance, you can argue that the title of The Wizard of Oz works to highlight the seductive world of Oz, so different from Kansas, with the Wizard himself being a figure with one foot in fantasy and one in reality (since the Wizard is actually a prairie mountebank). Similarly, I’m inclined to say that Sansho the Bailiff’s title reminds us of the socially sanctioned cruelty at its center. Zushio and Anju, the fugitive brother and sister, may each escape in a different way, but Sansho’s world remains; it is our world.

Some titles are simply place names, like Casablanca, Macao, Philadelphia, or New York, New York. Others specify dates: 1860, 1900, 1941, 1984. In both strategies, the title often evokes symbolic associations or parallels with the here and now.

The title can refer to the core situation, as with Back to School or Being John Malkovich, or to a key scene, as in Sophie’s Choice and Gunfight at the OK Corral. This can get abstract and metaphorical. Housekeeping features a very offbeat approach to housekeeping. The Birth of a Nation characterizes America reborn after the Civil War. Being There describes more or less all that the cipher-like hero does. The title can even predict the action, as in The Great Escape, A Man Escaped, and Killing of a Chinese Bookie. In these instances we have anomalous suspense: Why and how will an announced action be carried out?

Reaching for the Moon (1917/ 1930/ 1933)

More rarely, the title can refer to the film’s central formal device. Through Different Eyes and Vantage Point announce that they will play with subjective point of view. The Blair Witch Project justifies its title by posing as a dossier of found student footage. The Prestige warns us that a magic trick’s surprise payoff might well be matched by one at the end of this movie. Kristin and I have long assumed that the title of Tati’s Play Time refers not only to the anarchic relaxation unleashed in the Royal Garden restaurant but also to the movie’s own perceptual strategy of making us see amusement in banal incidents.

Hitchcock, the tireless formalist, provided titles that give away his game. Rear Window announces a stationary viewpoint and a limited field of action. More fancifully, you could take Rope as announcing the film’s sinuous long takes. Family Plot is nicely equivocal, referring at once to a communal grave, a conspiracy among kin, and of course the movie’s own mysterious plot of knotty kin relations.

Then there are the generic characterizing titles, usually single-word titles like Notorious or Spellbound or Pushover or Identity or Slacker or Speed or even, probably most generic of all, Conflict (borne by at least five films, from 1916 to 1955). Here again, though, we can find puzzles.

We know why Homicidal is called Homicidal, but what purpose is served by calling a movie Psycho? Again, the source book provides the title, but Robert Bloch’s novel is narrated in the first person and the title gives us a big clue about the sort of mind we’re in. Hitchcock’s film presents the story more objectively, and it begins with Marion Crane’s theft. Those critics who see the film as blurring the boundaries between sanity and insanity would say that Marion, who impulsively commits a crime, and Norman are points on a continuum. People we take to be normal have irrational impulses, a point reinforced by Norman’s line, “We all go a little mad sometimes. Haven’t you?” After their conversation about private traps, Marion seems to recognize herself in his question.

Same old song (1997)

Many titles are citations or quotations, and they usually highlight a thematic element. Both Yankee Doodle Dandy and Born on the Fourth of July are drawn from the same song: both offer portraits of patriotism, but in very different keys. Pennies from Heaven is highly, perhaps heavily, ironic, something you can’t say about Meet Me in St. Louis.

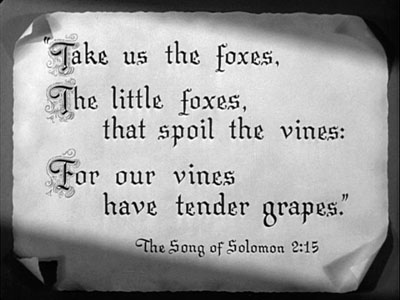

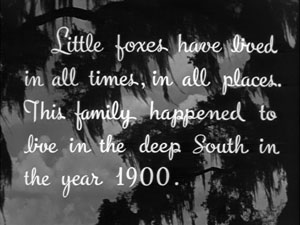

Not all citations are as transparent as these. The Little Foxes explains its title in a prologue, seen above. The Bible verse is then linked to the story we’ll see.

We’re ready to understand the family as creating a milieu that could easily corrupt the tender vine, Xan.

A catch phrase can work too, such as The Sweet Hereafter or It Takes a Thief or It’s a Wonderful Life. You Can’t Take It With You emphasizes pursuing fun rather than riches. Phffft suggests that a couple has split, but how would you explain that outside the U. S.? (The French title is, perhaps surprisingly, Phffft.)

Some catchphrase titles suggest the sort of multiple meanings we saw in Family Plot and Play Time. All That Jazz packs a lot into three words: most basically, a flurry of trivial stuff (pushing our hero into overdrive), but also music and the heights of emotion (being jazzed). You Only Live Once at first suggests seizing the moment, but by the end of the film you begin to think it implies: “Who could bear to live twice?” I especially like The Best Years of Our Lives, which also changes its significance across the film. The bulk of the movie asks: The returning servicemen have given their prime years for us, but how do we reward them? By the end of the movie, the title seems to be suggesting that their best years, of healing and self-understanding and integration into families, lie ahead of them.

I’ve known students, especially from outside the U. S., to have trouble with His Girl Friday. It’s a two-tiered reference. First is Robinson Crusoe’s “man Friday,” his aboriginal servant. But in American slang, a girl Friday is the boss’s closest female assistant, an all-around tough worker and troubleshooter. That’s what Hildy is to Walter Burns, until she decides to marry Bruce and move to Albany. She reverts to her girl Friday role in the course of the film, as the title has predicted she would.

We don’t always know when a quotation is at work. I have always found Some Came Running obscure. The phrase isn’t used in the film, or in the text of the James Jones source novel. But the novel’s epigraph takes a passage from Mark 10: 17:

And when he was gone forth into the way, there came one running, and kneeled to him, and asked him, Good Master, what shall I do that I may inherit eternal life?

This is the passage where Jesus asks the rich man to give all that he has to the poor, apparently as unlikely an event then as now. The problem is that in the Biblical passage, only one came running. The reader has to imagine several characters in the novel as “running” to ask how they will get into heaven. But the citation seems to me a mismatch, since the characters of novel and film aren’t all rich. In any case, without the epigraph tacked to the movie, its significance gets lost. This doesn’t stop me from liking the title, though.

One of my favorite instances of the obscure catchphrase-title is Ozu’s I Was Born, But . . . To decipher it you have to know that during the Depression, Japanese college graduates often couldn’t find work, and the sentence “I graduated, but . . . ,” trailing off, suggesting “. . . I’m unemployed,” was a topical one at the time. Ozu in fact made a film with that title. But then he decided to have fun with it, making a college comedy called I Flunked, But . . . Then came an even sillier extension: When he makes a film about boys, it becomes I Was Born, But . . . [I still have problems…]. Our parallel, I suppose, is the move from Honey, I Shrunk the Kids to Honey, I Blew Up the Kid.

Which reminds me: Titles have a strange habit of speaking for the character. We have I Was a Teenage Werewolf, I Dood It, I Love Melvin, Me and the Colonel, My Favorite Brunette, My Cousin Vinny, Blackmail Is My Life, and so on. This convention points up the difference between literature and film. A book with one of these titles would lead us to expect first-person narration, and it would be strange if it didn’t. A movie with such a title might provide voice-over commentary from the protagonist, as How Green Was My Valley and I Walked with a Zombie do, but more likely it won’t.

For Your Eyes Only (1981)

Many titles seem enigmatic when you first hear them. They create curiosity and build up an urge to check out the film. In most cases, the mystery gets cleared up in the course of the movie. Erik Gunneson’s Milk Punch does this through a bit of action, but more commonly the title is clarified in a line of dialogue or a motif. You have to wait for the very end of They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? or Rio Bravo to get a reference to the title. A good embedded title shifts its meanings, as Best Years does. One scene of Silence of the Lambs explains the title’s relevance to Clarice’s character and shows what drives her to pursue Buffalo Bill. By the end of the film it points toward a moment when her inner pain will start to fade. And the title may reverberate beyond that moment, pointing to larger themes of injured innocence in a world of slaughter.

Sometimes the title is more oblique. Take North by Northwest. Many critics believe that it refers to Hamlet’s confession that “I am but mad North-northwest: When the wind is southerly, I know a hawk from a handsaw.” Roger Thornhill, caught off balance by the espionage game he’s plunged into, could be said to have lost his bearings. But I’ve always thought that the compass-point title logo and the cross-hatched latitude/ longitude array that launch the movie prepare us for travel, in a roughly westerly, then northwesterly direction (New York-Chicago-South Dakota). And when Roger is sent from Chicago to Rapid City, he travels by airliner: He flies north, by Northwest. A Hitchcock joke?

We occasionally encounter a title that isn’t explained in the course of the action, so we are invited to ponder its implications. 8 ½ is a famous example; insiders know Fellini treated it as an opus number (seven features + two shorts + this new feature = 8 ½). American Graffiti can refer to the transitory events of the single night the film shows—the kids have scrawled their dramas on the town in one long summer blast. But I think you can also read the title as referring to the pop tunes that engulf and comment on the action. Americans write their graffiti on the airwaves.

In recent times Hong Kong films have tried to make their English-language titles more comprehensible, but in the golden years there were some delirious ones. We had Banana Cop, Wheels on Meals, Why Wild Girls, Gun Is Law, Tiger on Beat, Devil Fetus, Burning Sensation, Boys?, Kung-Fu vs. Acrobatic, Evil Black Magic, Ghost Punting, Takes Two to Mingle, Vampire’s Breakfast. . . Even Chungking Express and Ashes of Time aren’t straightforward. A real problem in studying Hong Kong films seriously is to explain to people that a movie called Police Story or Naked Killer can be pretty interesting. And if the titles don’t perturb them, the subtitles will.

But most of the Hong Kong titles are inadvertently puzzling, sort of accidental surrealism. Of course Surrealist filmmakers have given us many willfully meaningless titles, such as Emak Bakia and The Andalusian Dog. Arguably Brazil and even A Hard Day’s Night are in this vein (although I think that both of these can be explained in roundabout ways).

Today’s American films seem drawn to recherché titles. I heard Jonathan Caouette remark that he chose the title Tarnation for reasons he couldn’t specify; it just seemed to fit. One catchphrase, “the elephant in the room,” has founded two movies, but in such an abbreviated form—Elephant—that you might not recognize the link. I never thought I’d find synecdoche on a movie credit, since few Americans know how to pronounce it, let alone know what it means. But trust Charlie Kaufman to give it a try. (He also inadvertently stole a pun I’ve been using in film theory courses since the seventies.) But at least I think I get the title’s point, given the protagonist’s obsession to build a miniature city. Other titles are flat-out baffling.

Take Reservoir Dogs. Tarantino says “it’s more of a mood title, it just sums up the movie, don’t ask me why.” (1) I like the title. I just don’t understand why it works so well. Do certain dogs guard reservoirs, as some guard junkyards? Are these guys as vicious as dogs, as dirty as dogs, or doggy in the sense of losers, or what? In other words, why does it seem more fitting than, say, Sump-Pump Ferrets?

Despite the logo showing faces spilling out of a blossom, Magnolia doesn’t explain its title unless you dig around outside the film. During the rain of frogs, the traffic collisions take place on Magnolia Boulevard in the San Fernando Valley. So in a way, Magnolia is one point of convergence for several of the story lines that crisscross the plot. But that’s pretty thin motivation.

What about Syriana? Before I went to the film, I had heard that the title referred to an imaginary, prototypical Middle Eastern territory used in Pentagon war games and computer simulations. But Stephen Gaghan, in another Creative Screenwriting podcast, supplies details:

It was a real term. I heard it for real in a very conservative think-tank, where they said, “We’re going to redraw the map in the Middle East, we’re going to make a new country out of Syria, Iraq, and Iran—the borders of ancient Persia, less Pakistan. We’re going to call it Syriana.” I’m like, “Excuse me? Would you repeat that?” So I shot it, I had William Hurt explaining it. But I didn’t think it helped at the end of the day. We’re not going to make a new country in the Middle East right now.

As he saw the collapse of America’s invasion of Iraq, Gaghan came to believe that explaining the title would date the movie.

I wanted to go for a title that couldn’t be pegged to right now. You notice there’s no reference to Iraq in the movie, there’s just the most passing reference to 9/11, which was an improv thing we did, and there’s no Israel. I wanted the more permanent sense of what it is inside of men, particularly men in the west, that makes them believe that they can remake any region to suit their own purposes. . . . I wanted it to be specific to the film, not to the time. So that if you think about the tone of the film, when you think about what happened in the movie, it would only be Syriana, and Syriana could not skid into some other reference point.

Then there’s Cloverfield, which I’ve discussed earlier this year. Part of the movie’s mystique is that nobody can agree on what the title refers to. The creature? Central Park, where the video camera is found? An exit on California Interstate 10, near where producer J. J. Abrams has his office? On this last option, screenwriter Drew Goddard says no way:

If we would do that, we would be dicks. We would be assholes.

I don’t want to get into the labyrinthine question of the relations of Cloverfield to Lost and to the film’s viral marketing campaign online. What interests me is the fact that part of the fun around, if not exactly in, the film is playing with all these possibilities . . . and waiting to see if a sequel will explain further. Perhaps a teasing title can help get people into theatres for a followup movie.

Finally, Primer. Not only do I not understand the significance of the title; I don’t know how to pronounce it.

I Love a Mystery (1945)

Why have we seen such a rise in cryptic titles in recent years? Several factors seem important. A puzzling title lifts your film above the clutter and creates buzz as people wonder what this movie could be about. This buzz factor is multiplied by the Internet. The title can be researched through Google and discussed endlessly in chatrooms. Filmmakers know that we can revisit a film on video whenever we want, so the movie can be rescanned by eager eyes searching for clues to the title’s meaning. Mystery titles summon up the geek in us.

Which means that the current wave of peculiar titles probably owes a lot to Tarantino. In the interview I already cited, Tarantino stressed that that title of Reservoir Dogs let the audience play with the possibilities.

The main reason that I don’t go on record is because I really believe in what the audience brings. . . . People come up to me and tell me what they think it means and I am constantly astounded by their creativity and ingenuity. As far as I’m concerned, what they come up with is right, they’re 100 percent right. (2)

But then, as Jonathan Walley pointed out to me, cool opacity isn’t confined to movie titles.

Band names have always been evocative: The Rolling Stones weren’t literally rolling stones, The Pixies not literally pixies. But what many of them evoke now strikes me as much more obscure and, to quote Grandpa Simpson, “weird and scary”: System of a Down, Teeth of Lions Rule the Divine, One Day as a Lion, My Morning Jacket, etc. Many of these are alternative bands, and many of the films with these obscure titles are alt/indie films, or at least films with those pretensions, so there’s a parallel there, I’d say. The willful obscurity of title, of band or film, evokes an ironic, think-outside-the-box, you’re-not-meant-to-get-it indie attitude that appeals to the intended audience.

That is, obtuse titles for an acute public.

For comments, suggestions, and memory-jogging, thanks to the Badger Filmies: Susan Antani, Colin Burnett, Andrea Comiskey, Sydney Duncan, Stew Fyfe, Jason Gendler, Doug Gomery, Jonah Horwitz, Tristan Mentz, Jason Mittell, Tim Palmer, John Powers, Brad Schauer, Chris Sieving, and Jonathan Walley.

(1) Quoted in “Reservoir Dogs Press Conference,” in Quentin Tarantino Interviews, ed. Gerald Peary (Oxford: University of Mississippi Press, 1998), 38.

(2) Some writers have hazarded that the title derives from Tarantino’s awkward pronunciation of Au revoir les enfants, coupled with Straw Dogs, but as far as I can tell, this relies on a second-hand source–ie, a former girlfriend–and Tarantino hasn’t confirmed it.