A turning point in digital projection?

Sunday | October 21, 2007 open printable version

open printable version

Kristin here–

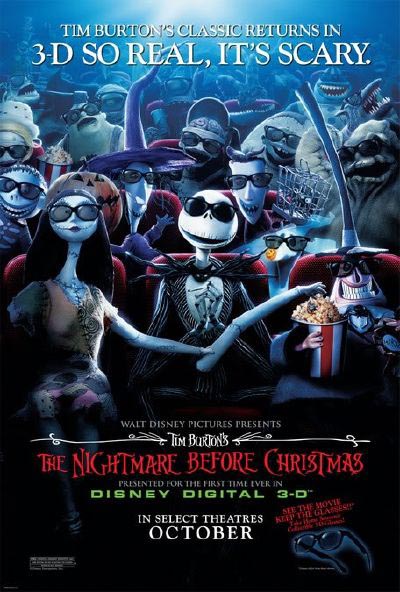

This past Friday, October 19, marked an historic moment in the history of Madison movie-going. We got our first permanent digital projection set-up, and not just digital, but 3D. The first film to be presented there was Tim Burton’s The Nightmare before Christmas.

We’ve had several big changes in the local theater scene recently. In May the first purpose-built Sundance Cinemas art-film multiplex opened. Madison, I gather, is considered a pretty good moviegoing market for its size. A more modest two-screen theater, the Hilldale, was shut down and demolished. Not such a bad thing, since the Hilldale, a two-screen house, was not aging well. We now have two multiple-screen theaters showing nothing but art films, Westgate and Sundance, as well as the Orpheum theater, University of Wisconsin union, and the Communication Arts Department’s Cinematheque showing art films part-time. Overall the city has a total of something like 60 screens for a population of just over 200,000.

Film vs. Digital: The Film Scholar’s Perspective

As film historians, David and I like to work directly with films. This summer he posted an entry on the joys and possibilities of analyzing films on a flatbed editing table. We used to insist that all the frame enlargements we used to illustrate our books be from film. We acquired hundreds of trailers and patiently cut them up, mounting them in slide frames to use in lectures. Naturally they looked great. For older films, we went to archives and used special photographic equipment to capture frames. Eventually DVD technology got good enough that we had to admit frames captured from them could look as good on the pages of a textbook as reproductions from our slides or negatives. Now Film Art and our other books contain illustrations from a mixture of sources.

But obtaining images for illustrations is a very different thing from watching a movie projected digitally in a theater. The images from a strip of real film have a distinctive look to them. They convey a sense of life. It’s a subtle thing, but the minute grains that make up the blacks, whites, and colors in the frames shimmer slightly from frame to frame. (That’s why a freeze frame makes an image look suddenly grainy. There’s no play of the particles from frame to frame to overlap and create a richness.) Digital projection throws visual information on the screen far faster, eliminating the shimmer and creating instead a fixed-looking image.

So we’re not in a great hurry to see 35mm projection disappear, and we watch the growth of digital exhibition with both interest and some trepidation.

The Slow Progress of Digital Projection

Digital projection has been around for years now, but for most of those years we lovers of 35mm film could largely ignore it. The earliest digital screenings of films in theaters took place way back in 1998, with satellites beaming The Last Broadcast into the few American houses with the proper equipped. Every now and then other digital advances would be touted, but the installation of digital projection equipment around the world has been slow.

Some of the reasons for that slowness are obvious. As usual with such technological breakthroughs, there have been competing systems. There still are. The cost of such a projection system is around $150,000. Tell your theater-chain owner holding nine sites, each with ten screens, that he or she needs to make an expenditure of $13.5 million and see what the response is. Especially if that owner has fairly new, expensive 35mm projectors already installed. The theater owners have argued that the distributors should pay part of the costs. The distributors, naturally, want the exhibitors to pay.

Both groups would gain advantages from digital. Among those are savings in printing up thousands of copies of a given film, usually at over a thousand dollars apiece, and shipping the very heavy prints via overnight courier service. There would be no physical prints going through projector gates and suffering scratches and breakage.

Assuming theater owners will end up paying for most or all of the conversion, they would want to charge extra in order to make up the costs of the equipment. There are undoubtedly people who think digital is superior, and they would pay a higher admission price. A lot of moviegoers, however, couldn’t care less whether the moving image they see in the multiplex is coming out of a 35mm projector or a digital one—and they’re probably not about to pay a dollar or two more to go in the digital auditorium that’s playing The Bourne Ultimatum rather than the one with the old-fashioned 35mm system.

Until now, that is. Modifications of projection systems that allow for 3-D projection have finally given exhibitors a selling point that will get patrons into theaters at advanced prices. Our local multiplex that is showing Nightmare is charging two dollars more for it than for films on its other screens. Apparently people will pay. Nationwide this weekend Nightmare is estimated to make $5,245,000 in 564 theaters, for a per-screen average of $9,122. That’s the highest average in the top 25 films. In contrast, 30 Days of Night, the top grosser at $16 million, has a $5,604 per-screen average.

The question remains, will people remain willing to pay extra for 3-D once its novelty value wears off?

2007 is increasingly being touted as the year when digital installations have speeded up most radically. The conversion will still be a slow process, but for the first time it becomes plausible to think that in the not too distant future digital might kill off 35mm projection. In the October 13-14 issue of The Hollywood Reporter, Gregg Kilday, its editor, suggests that 2009 will be the breakthrough year for digital 3-D. Two major 3-D projects, DreamWorks’ animated Monsters vs. Aliens and James Cameron’s Avatar, will debut within a few months of each other. The real question, he says, is whether enough theaters will be outfitted with digital projection by then. With big theater chains now adopting the new technology, it seems quite possible. (See here for an excellent summary of the current situation of theater conversion and 3-D films in the pipeline.)

Alone with my 3D Glasses

As I was sitting at my desk last Wednesday afternoon, finishing up my David Cronenberg entry, I got a call from a friend of ours, Tim Romano. Tim is an expert projectionist, perhaps the best in town. He’s the one theaters often call on to test new equipment and screen the big blockbusters ahead of time to check for flaws. Not surprisingly, Tim was testing the new digital projector by running Nightmare over and over, as if for a regular day’s screenings, but without an audience. Tim suggested that I might want to drop in and catch a screening. Naturally I headed for we call Point, which is really the Marcus Point UltraScreen Cinema.

As the name suggests, Point is part of the Marcus Theatres Corporation’s chain of 47 theaters (594 screens), scattered across Wisconsin, Illinois, Minnesota, Ohio, North Dakota, and Iowa. Some of the chain’s other theaters will be getting digital projection installations as well. The name Marcus is a big one here in the Midwest, since The Marcus Corporation also owns or manages 20 hotels in the area. Its theater chain is the seventh largest in the country.

Arriving at Point, I received my 3-D glasses from the ticket seller, obtained my snack of choice (Junior Mints), and headed for what proved to be an otherwise empty auditorium. I had missed the opening, but having seen the film a couple of times, I figured that didn’t matter. I was here to see what digital 3-D looks like.

When we go to the movies, David and I usually sit in the center of rows three to five, depending on the size of the screen. This time I sat in row five, but I quickly found the edges of the eyepieces were not wide enough to take in the entire screen. There’s an aisle across the auditorium behind the fifth row, so I sat at the front of the upper section of the house, approximately row eight. That worked fine.

I’m not sure the glasses I had were the same kind that are being used for commercial screenings. Still, my impression is that if you’re used to being down front, sitting a bit further back works well for this film.

Nightmare was originally made on 35mm film using stop-motion to animate puppets. It was transformed into a 3-D film using technology from a company called Real D, which also has been the major player in the move to install digital projection equipment in theaters.

Tim wasn’t, however, projecting Nightmare on a Real D projection setup. Just recently Dolby has moved into digital projection in a big way, and the Point installation is part of its rollout of competing equipment. (For details and other cinema chains using Dolby, see here.) Dolby may have the edge, since its projector works with existing white screens, while Real D’s requires a special silver one.

Happily, the new polarized glasses work better than earlier models. My experience with the older glasses was that one’s eyes sometimes had to struggle to resolve the images onscreen into three dimensions, and one could end up with a headache by the end of the movie. Dolby’s digital 3-D system makes perception of the depth effects automatic and effortless.

Speaking of the glasses, I was amused to note that publicity for the film (see the poster above) shows the characters wearing what look very much like sunglasses. Most probably people still think of 3-D glasses as clunky and cumbersome. This is clearly an attempt to counter that image and make the glasses look cool, like the ones sported by characters in Men in Black or The Matrix.

The depth effect is definitely impressive, even in a retro-fitted film like Nightmare. Because it was not originally produced in 3-D, most of the depth appears to extend behind the screen. I remember seeing 3-D films made in the 1950s that strive to thrust objects out at the audience—most effectively in House of Wax when a carnival barker has a paddle-ball that he bounces directly toward the camera. I rather prefer the depth behind the screen to the depth in front, which tends to be distracting. Whatever the promoters say about people wanting to feel themselves in the movie, I would prefer not to have projectiles coming at my face or actors tumbling into my lap.

The movement of the characters was fine most of the time. I found that rapid action caused a ghosting, blurred effect that was quite different from the rock-steady three-dimentionality of static or slowly moving figures. That ghosting may simply be an artifact of the process of turning 2-D into 3-D, and perhaps films made in 3-D will not have it.

Then there’s the matter of grain and other qualities of 35mm film. Certainly one can’t object to the lack of dust and scratches. The absence of grain is a little disconcerting, but it’s really hard to judge in an animated film like this. Presumably, though, it’s not significantly different from 2-D digital projection, which I’ve never seen. I suppose I shall get used to it.

The Current Trend

So Nightmare provides only a limited indication of what the future holds.

Thus far animated films have made up the bulk of the digital 3-D films released. It’s much easier and cheaper to build 3-D into a CGI cartoon (e.g., Disney’s Meet the Robinsons) than to use it on the set of a live-action film. Indeed, the current generation of 3-D features that include actors have employed motion-capture technology. The proof of that pudding will come with Robert Zemekis’s Beowulf, due out November 16.

The real future of 3-D will depend on it attracting adult audiences, and that means that more live-action films will need to be made. That’s not happening now because the technology remains to expensive, cumbersome, and touchy to be easily used on set. The technology is bound to advance, though.

In the meantime, possibly we can expect that for the near future, digitally equipped auditoriums will be a little like Imax is now. A multiplex might have one Imax screen, but it would never put Imax in all its other theaters. Similarly, a theater owner might be willing to pay that $150,000 to convert one projection system in a multiplex, with digital 3D remaining a special attraction, one which people are willing to pay a little extra for.

If such a scenario is fulfilled, then we may see 35mm and digital share the multiplexes of the world for a long time. You wouldn’t hear me complaining.