Archive for the 'National cinemas: Italy' Category

Stuck inside these four walls: Chamber cinema for a plague year

The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972).

Privacy is the seat of Contemplation, though sometimes made the recluse of Tentation… Be you in your Chambers or priuate Closets; be you retired from the eyes of men; thinke how the eyes of God are on you. Doe not say, the walls encompasse mee, darknesse o’re-shadowes mee, the Curtaine of night secures me… doe nothing priuately, which you would not doe publickly. There is no retire from the eyes of God.

Richard Brathwaite, The English Gentlewoman (1631)

DB here:

We’re in the midst of a wondrous national experiment: What will Americans do without sports? Movies come to fill the void, and websites teem with recommendations for lockdown viewing. Among them are movies about pandemics, about personal relationships, and of course about all those vistas, urban or rural, that we can no longer visit in person. (“Craving Wide Open Spaces? Watch a Western.”)

Cinema loves to span spaces. Filmmakers have long celebrated the medium’s power to take us anywhere. So it’s natural, in a time of enforced hermitage, for people to long for Westerns, sword and sandal epics, and other genres that evoke grandeur.

But we’re now forced to pay more attention to more scaled-down surroundings. We’re scrutinizing our rooms and corridors and closets. We’re scrubbing the surfaces we bustle past every day. This new alertness to our immediate surroundings may sensitize us to a kind of cinema turned resolutely inward.

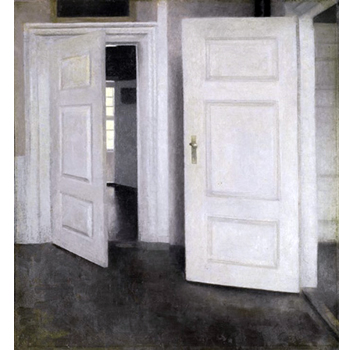

Long ago, when I was writing a book on Carl Dreyer, I was struck by a cross-media tradition that explored what you could express through purified interiors. I called it “chamber art.” In Western painting you can trace it back to Dutch genre works (supremely, Vermeer). It persisted through centuries, notably in Dreyer’s countryman Vilhelm Hammershøi (below).

Plays were often set in single rooms, of course, but the confinement was made especially salient by Strindberg, who even designed an intimate auditorium. For cinema, the major development was the Kammerspielfilm, as exemplified in Hintertreppe (1921), Scherben (1921), Sylvester (1924), and other silent German classics. Kristin and I talk about this trend here and here.

In the book I argued that Dreyer developed a “chamber cinema,” in piecemeal form, in his first features before eventually committing to it in Mikael (1924) and The Master of the House (1925). Two People (1945) is the purest case in the Dreyer oeuvre: A couple faces a crisis in their marriage over the course of a few hours in their apartment. (Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem available with English subtitles.) But you can see, thanks to Criterion, how spatial dynamics formed a powerful premise of his later masterpieces Vampyr (1932), Day of Wrath (1943), Ordet (1955), and Gertrud (1964).

Dreyer wasn’t alone. Ozu tried out the format in That Night’s Wife (1930), swaddling a husband, wife, child, and detective in a clutter of dripping laundry and American movie posters.

Bergman exploited the premise too, in films like Brink of Life (1958), Waiting Women (1952), his 1961-1963 trilogy, and Persona (1966). (All can be streamed on Criterion.)

Chamber cinema became an important, if rare expressive option for many filmmaking traditions. Writers and directors set themselves a crisp problem–how to tell a story under such constraints?

The challenge is finding “infinite riches in a little room.” How? Well, you can exploit the spatial restrictiveness by confining us to what the inhabitants of the space know. Limiting story information can build curiosity, suspense, and surprise. You can also create a kind of mundane superrealism that charges everyday objects with new force.

On the other hand, you need to maintain variety by strategies of drama and stylistic handling. Chamber cinema–wherever it turns up–offers some unique filmic effects, and maybe sheltering in place is a good time to sample it.

Herewith a by no means comprehensive list of some interesting cinematic chamber pieces. For each title, I link to streaming services supplying it.

Bottles of different sizes

From David Koepp I learned that screenwriters call confined-space movies “bottle” plots. There’s a tacit rule: The audience understands that by and large the action won’t stray from a single defined interior. In a commentary track for the “Blowback” episode of the (excellent) TV show Justified, Graham Yost and Ben Cavell discuss how TV series plan an occasional bottle episode, and not just because it affords dramatic concentration. It can save time and money in production.

Usually the bottle consists of more than a single room. The classic Kammerspielfilms roam a bit within a household and sometimes stray outdoors. But their manner of shooting provides a variety of angles that suggest continuing confinement. Dreyer went further in The Master of the House. He built a more or less functioning apartment as the set, then installed wild walls that let him flank the action from any side. Then editing could provide a sense of wraparound space.

The variations in camera setups throughout the film are extraordinary. Dreyer would create more radically fragmentary chamber spaces in La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928), while his later films would use solemn, arcing camera movements to achieve a smoother immersive effect. (For more on Dreyer’s unique spatial experimentation, here’s a link to my Criterion contribution on Master of the House. I talk about the tricks Dreyer plays with chamber space in Vampyr in an “Observations” supplement on the Criterion Channel.)

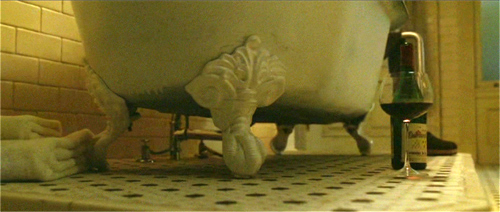

Likewise, Koepp’s screenplay for Panic Room allows David Fincher to move 360 degrees through several areas of a Manhattan brownstone. The film also offers a fine example of how our awareness of domestic details gets sharpened by a creeping camera.

Trust Fincher to find sinister possibilities in a dripping bathtub leg and a kitchen island.

Confined to quarters

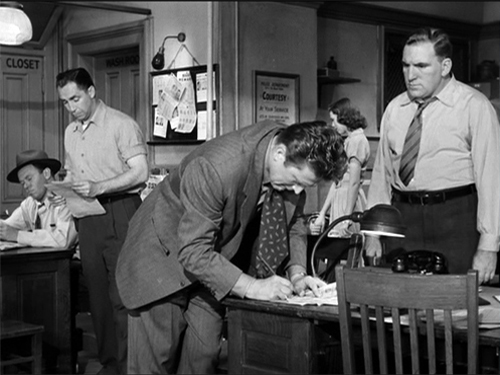

Detective Story (1951).

Many chamber movies are based on plays, as you’d expect. Unlike most adaptations, though, they don’t try to “ventilate” the play by expanding the field of action. Or rather, as André Bazin pointed out, the expansion is itself fairly rigorous. They don’t go as far afield as they might.

Bazin praised Cocteau’s 1948 version of his play Les parents terribles (aka “The Storm Within”) for opening up the stage version only a little, expanding beyond a single room to encompass other areas of the apartment. This retained the claustrophobia, and the sense of theatrical artifice, but it spread action out in a way that suited cinema’s urge to push beyond the frame. The freedom of staging and camera placement is thoroughly “cinematic” within the “theatrical” premise.

Depending on how you count, Hitchcock expanded things a bit in his adaptation of Dial M for Murder. Apart from cutting away to Tony at his club, Hitchcock moved beyond the parlor to the adjacent bedroom, the building’s entryway, and the terrace.

An earlier entry on this site talks about how 3D let Sir Alfred give an ominous accent to props: a particularly large pair of scissors, and a more minor item like the bedside clock.

Hitchcock gave us a parlor and a hallway in Rope (1948), but when Brandon flourishes the murder weapon, the framing audaciously reminds us that we aren’t allowed to go into the kitchen.

Bazin did not wholly admire William Wyler’s Detective Story (1951), despite its skill in editing and performances; he found it too obedient to a mediocre play. True, the film doesn’t creatively transform its source to the degree that Wyler’s earlier adaptation of The Little Foxes (1941) did; Bazin wrote a penetrating analysis of that film’s remarkable turning point. Detective Story is more obedient to the classic unities, confining nearly all of the action to the precinct station. Although I don’t think Wyler ever shows the missing fourth wall, he creates a dazzling array of spatial variants by layering and spreading out zones of the room. In his prime, the man could stage anything fluently.

As Bazin puts it: “One has to admire the unequaled mastery of the mise-en-scène, the extraordinary exactness of its details, the dexterity with which Wyler interweaves the secondary story lines into the main action, sustaining and stressing each without ever losing the thread.”

Some films are even more constrained. 12 Angry Men (1957), adapted from a teleplay, is a famous example. Once the jury leaves the courtroom, the bulk of the film drills down on their deliberation. Again, the director wrings stylistic variations out of the situation; Lumet claims he systematically ran across a spectrum of lens lengths as the drama developed.

But you don’t need a theatrical alibi to draw tight boundaries around the action. Rear Window (1954), adapted from a fairly daring Cornell Woolrich short story, is as rigorous an instance of chamber cinema as Rope. Here Hitchcock firmly anchors us in an apartment, but he uses optical POV to “open out” the private space.

With all its apertures the courtyard view becomes a sinister/comic/melancholy Advent calendar.

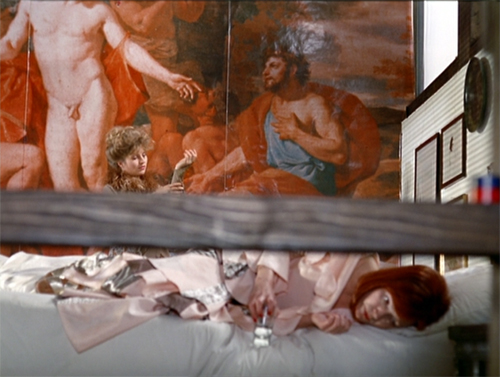

Fassbinder’s Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972) denies us this wide vantage point on the outside world. This space seems almost completely enclosed. But Fassbinder finds a remarkable number of ways to vary the set, the camera angles, and the costumes. We’re immersed in the flamboyant flotsam of several women’s lives. The result is a cascade of goofily decadent pictorial splendors.

It’s virtually a convention of these films to include a few shots not tied to the interiors. At the end, we often get a sense of release when finally the characters move outside. That happens in 12 Angry Men, in Panic Room, in Polanski’s Carnage (2011) , and many of my other examples. Without offering too many spoilers, let’s say Room (2015) makes architectural use of this option.

On the road and on the line

Filmmakers have willingly extended the bottle concept to cars. The most famous example is probably Kiarostami’s Ten (2002), which secures each scene in a vehicle and mixes and matches the passengers across episodes. The strictness of Kiarostami’s camera setups exploit the square video frame and always yield angular shot/reverse shots. They reveal how crisp depth relations can be activated through the passing landscape or in story elements that show up in through the window.

Perhaps Kiarstami’s example inspired Danish-Swedish filmmaker Simon Staho. His Day and Night (2004) traces a man visiting key people on the last day of his life, and we are stuck obstinately in the car throughout. This provides some nifty restriction, most radically when we have to peer at action taking place outside.

Staho’s Bang Bang Orangutang (2005), a portrait of a seething racist, takes up the same premise but isn’t quite so rigorous. We do get out a bit, but the camera stays pretty close to the car. I discuss Staho’s films a little in a very old entry.

Like autos, telephones provide a nice motivation for the bottle, as Lucille Fletcher discovered when she wrote the perennial radio hit, “Sorry, Wrong Number.” The plot consists of a series of calls placed by the bedridden woman, who overhears a murder plot. The film wasn’t quite so stringently limited, but the effect is of the protagonist at the center of several crisscrossed intrigues.

A purer case is the Rossellini film Una voce umana (1948), in which a desperate woman frantically talks with her lover. It relies on intense close-ups of its one player, Anna Magnani.

It’s an adaptation of a Cocteau play, which Poulenc turned into a one-act opera. In all, the duration of the story action is the same as the running time.

I wish Larry Cohen’s Phone Booth displayed a similarly obsessive concentration, but we do have the Danish thriller The Guilty, where a police dispatcher gets involved in more than one ongoing crime. We enjoyed seeing it at the 2018 Wisconsin Film Festival.

And of course car and phone can be combined, as they are in Locke (2013)–another play adaptation. Tom Hardy plays a spookily calm businessman driving to a deal while taking calls from his family and his distraught mistress. Those characters remain voices on the line while he tries to contend with the pressures of his mistakes.

House arrest, arresting houses

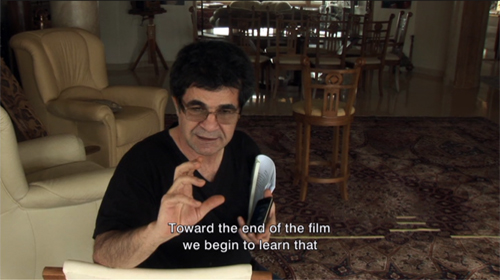

Sometimes you must embrace the chamber aesthetic. In 2010 the fine Iranian director Jafar Panahi was forbidden to make films and subjected to house arrest. Yet he continued to produce–well, what? This Is Not a Film (2012) was shot partially on a cellphone within (mostly) his apartment.

Wittily, he tapes out a chamber space within his apartment. Then he reads a script to indicate how absent actors could play it and how an imaginary camera could shoot it.

But his imaginary film still isn’t an actual film, so he hasn’t violated the ban. So perhaps what we have is rather a memoir, or a diary, or a home video? Panahi’s virtual film (that isn’t a film) exists within another film that isn’t a film. Yet it played festivals and circulates on disc and streaming. The absurdity, at once touching and pointed, suggests that through playful imagination, the artist can challenge censorship.

Panahi slyly pushed against the boundaries again with Closed Curtain (2013, above). Shot in his beach house, it strays occasionally outside. Next came Taxi (2015), in which Panahi took up the auto-enclosed chamber movie, with largely comic results.

More recently, he has somehow managed to make a more orthodox film, 3 Faces (2018), which considers the situation of people in a remote village.

The chamber-based premise needn’t furnish a whole movie. As in Room, Kurosawa’s High and Low (1963) is tightly concentrated in its first half. We are in two enclosures, a house and a train. The film then bursts out into a rushed, wide-ranging investigation. Large-scale or less, the chamber strategy remains a potent cinematic force.

They say that the last creatures to discover water will be fish. We move through our world taking our niche for granted. Cinema, like the other arts, can refocus our attention on weight and pattern, texture and stubborn objecthood. We can find rich rewards in glimpses, partial views, and little details. Chamber art has an intimacy that’s at once cozy and discomfiting. Seeing familiar things in intensely circumscribed ways can lift up our senses.

So take a break from the crisis and enjoy some art. But return to the world knowing that for Americans this catastrophe is the result of forty years of monstrous, gleeful Republican dismantling of our civil society. Rebuilding such a society will require the elimination of that party, and the career criminal at its head, as a political force. This pandemic must not become our Reichstag fire.

Yeah, I went there.

Thanks to the John Bennett, Pauline Lampert, Lei Lin, Thomas McPherson, Dillon Mitchell, Erica Moulton, Nathan Mulder, Kat Pan, Will Quade, Lance St. Laurent, Anthony Twaurog, David Vanden Bossche, and Zach Zahos. They’re students in my seminar, and they suggested many titles for this blog entry.

Bazin’s comments on Detective Story come in his 1952 Cannes reportage, published as items 1031-1033, and as a review (item 1180), in Écrits complets vol. I, ed. Hervé Joubert-Laurencin (Paris: Macula, 2018), pp. 918-922, 1059. My quotation comes come from the review, where he does grant that Wyler is the Hollywood filmmaker “who knows his craft best. . . . the master of the psychological film.”

The tableau style of the 1910s probably helped shift Dreyer toward the chamber model, which he learned to modify through editing. I discuss Dreyer’s relation to that style in “The Dreyer Generation” on the Danish Film Institute website. Also related is the web essay, “Nordisk and the Tableau Aesthetic.”

Some other examples could be mentioned, but I didn’t find them on streaming services in the US. It would be nifty if you could see the tricks with chamber space in Dangerous Corner (1934); fortunately it plays fairly often on TCM. There’s also Duvivier’s Marie-Octobre (1959), a tense drama about the reunion of old partisans.

I especially like the 1983 Iranian film, The Key, directed by Ebrahim Forouzesh and scripted by Kiarostami. It’s a charming, nearly wordless story of how a little boy tries to manage household crises when Mother is away. It has the gripping suspense that is characteristic of much Iranian cinema, and the boy emerges as resourceful and heroic (though kind of messy). Kids would like it, I think.

Also, I’ve neglected Asian instances. Maybe I’ll revisit this topic after a while.

P.S. 1 April 2020: Thanks to Casper Tybjerg, outstanding Dreyer scholar, for corrections about the nationality of The Guilty and the Staho films.

Gertrud (1964).

Women in charge: Highlights from Torino

Beanpole (2019).

DB here:

Every day we’ve spent at the Torino Film Festival has yielded us fine and sometimes superb film experiences. Herewith some examples, all probably coming to a screen (large, small) near you.

Extracurricular melodrama

Wet Season (2019).

From Anthony Chen (Ilo Ilo, 2013) comes a woman’s drama of professional and personal travail. Ling is a Malaysian teacher working in a Singapore boys’ school. She’s trying to get pregnant through in vitro fertilization , although her husband is reluctant. She takes care of her elderly father-in-law while pressing her mostly indifferent students to pass their Chinese examinations. Things take a drastic turn when, just as Ling’s husband drifts away from her, one boy becomes violently infatuated with her.

Poised and mild-mannered, Wet Season handles its melodramatic material with restraint. For instance, there’s the careful use of Ling’s car. She and her husband are introduced driving to work together, but the shots don’t show their faces. It’s an effective expression of their empty marriage. Similar shots recur throughout the film.

Denying us the standard view forces us to pay attention to the dialogue. Lest this be thought a simply byproduct of production constraints (it’s easier to shoot a rainy drive from the back seat), later we see Ling in a more standard angle.

The new framing allows us to see her accusing glance at Wei Lun.

Still other uses of the car enable Chen to stress Ling’s reactions to developments in the drama.

Here, as so often in film, simple but shrewd production choices can build strong emotional impact. By the end, when the typhoon has finally blown over, Ling can confront the future with some hope.

Horror diva

As indicated in our previous entry, the guest of honor for Torino’s horror retrospective was the star of 1960s Italian (and other) frightfests, Barbara Steele. She received the Gran Primio Torino during the festival. Several of her films were shown, reminding me of the delirious ways that Italian filmmakers revised the genre. Take the two features I saw.

Mario Bava’s Black Sunday (La maschera del demonio, 1960), which came out the same year as Psycho, is in some ways more shocking. The opening, in which a spike-studded iron mask is pounded bloodily into the face of a witch still makes you jump. What follows is essentially an old-dark-house plot, with one character after another prowling around a castle and getting killed off by the undead witch Asa and her brother. Asa targets her descendant, the beautiful Katia, in the belief that taking her blood will grant her immorality.

Barbara, with bat-wing eyelashes and magnificently tousled hair, plays both Asa and Katia. In a bravura image, Bava uses visual effects to give us the two women in a fine widescreen composition.

The film’s endless play of highlights and shadow is really something. Although I’ve seen it before, I never appreciated its visual splendor until I encountered this DCP restoration. Kristin pointed out that we can see how the eyelights on Asa are flicked on and off so that she seems throbbing with supernatural energy.

Two years later, Barbara made for director Riccardo Freda The Horrible Dr. Hichcock (L’Orribile Segreto del Dr. Hichcock). It’s close to 1940s Hollywood Gothics in centering on uxoricide. But in a typical giallo fantastic twist, the husband who dispatches one wife accidentally tries to kill a second to revive the first. There are 1940s motifs such as the sinister housekeeper (Rebecca), the dominating portraits of Wife #1, the efforts to gaslight Wife #2, and even a glowing glass of milk (Suspicion) with which Dr. H hopes to dispatch his new wife–played, of course, by Ms Steele.

Freda has recourse to the fog and sinister noises of Black Sunday, but Bava’s labyrinthine secret passages and torture chambers are replaced by rooms stuffed with sinister chachkies. And Hichcock is in Technicolor, so Freda gives the dank Victorian parlors a subdued color design. Barbara is right at home here too, rolling her eyes apprehensively as she’s given the poisoned milk.

In all, the Torino horror retrospective was a bracing reminder of a genre that has shaped popular cinema to this day. The presence of Ms Steele was a wonderful bonus.

Cops, moles, and femmes fatales

The Whistlers (La Gomera, 2019).

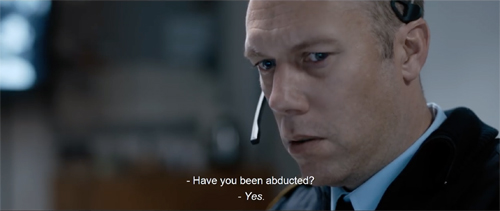

When a film is grounded in a basic genre formula, much of your enjoyment comes from seeing not only fresh twists of plot but also felicities of sound and image. That was my response to Corneliu Porumboiu’s The Whistlers (La Gomera), a quietly flashy neo-noir.

Everything is there. We have the intricate schemes of cops, crooks, and everybody in between in pursuit of mattresses stuffed with cash. There’s the tired, seen-too-much cop who works for the gang, not least because of the wiles of a stupendously gorgeous femme fatale. There are the Eurotrash thugs and heavies supervised by a calculating boss, and flashbacks that lead you to wonder who exactly is conning whom.

But Porumboiu tinkers with the familiar narrative mechanics. In an age of cellphones and video surveillance, the crooks must communicate in a frankly analog code: they whistle their messages, disguised as birdsong. The tough supervisor who suspects our protagonist is a mole isn’t the usual overbearing male, but rather a woman with her own femme fatale streak. She’s as suspicious of surveillance as the crooks, stepping outside her bugged office to negotiate extralegal stings with her staff.

Likewise, Porumboiu gives up the “free-camera” straying and fumblings that we see in so many films these days. He locks down his camera to create precise, radiant images. Here’s Gilda, yes, you heard that right, smoking and waiting for trouble.

It’s a pleasure to see crisp frame entrances and exits, along with tracking shots reserved for climactic moments, as when the gang steps into a police ambush mounted on a disused film set. A well-judged sense of framing enables an overhead shot in which the dark blood of a dead man at a work station flows into the mouse and lights it up in a discreet crimson flash.

The Whistlers isn’t as rich, I think, as the director’s earlier policier, Detective, Adjective, but it’s a satisfying genre exercise. It yields dry wit (sleek fashionista gangsters struggling to load mattresses into a small car) and surprise twists–not least the epilogue, which brings back the coded whistles in an amusing sound gag.

Women at war

Beanpole (2019).

Another way to put it: The Whistlers is that rarity today, the thoroughly “designed” film. Here all the stylistic and narrative choices stand sharply revealed as part of what we are to notice, and enjoy. (Other instances: the Coens, Almodóvar.) Another example at Torino is the already widely-praised Russian drama by Kantemir Balagov, Beanpole.

Leningrad: World War II has recently ended, and two women must face the postwar world. Iya and Masha have been gunners at the front. Iya was invalided out because of episodes of “freezing,” seizing up in a sort of paralyzed trance and making clicking sounds until the spasm eventually passes. Now she works in a hospital patching up wounded soldiers and taking care of Masha’s child, born at the front. Masha eventually returns and takes a job at the hospital as well.

But their friendship suffers through a horrific accident that plunges the towering and slender Iya, the beanpole (dilda, “tall girl”) of the title, into shame and depression. Masha, more aggressive in remaking herself as the war ends, drives the second half of the film. She begins a pragmatic relationship with the weak soldier Sasha. When he brings her home to meet his parents, proud members of the Bolshevik bourgeoisie, she supplies all her backstory about life on the front that fills in crucial gaps.

Beanpole‘s few characters–the two women, Sasha, and a weary doctor supervising the clinic–throb with a Dostoevksian intensity. With her paralysis and quiet mournfulness, Iya recalls Prince Myshkin; some shots virtually sanctify her.

As in Dostoevsky’s novels, nearly every scene is worked up to a furious emotional pitch. The nosebleed that seems to pass contagiously among characters is virtually a sign of passions under pressure.

The tension is carried through lengthy, often silent stares shared between characters thrusting themselves at one another. Balagov relies on close-ups and tight two-shots running very long; there are about 325 shots in the film’s 131 minutes. Here Iya helps a dying soldier to smoke in a perfectly composed two-shot in the wide format.

Without prettifying Leningrad during and after the siege, the film’s pictorial design is ravishing. The main sets are designed to complement one another. The hospital is bathed in a creamy light, while the night streets radiate a dark golden glow.

The apartment Iya and Masha share is ripe in dark greens and reds, the result of years of tearing away layers of wallpaper. (See our top image.) The doctor’s apartment offers a warmer, less distraught balance of reds and greens.

The palatial home of Sasha’s parents yields another register, one of tidy, frosty elegance.

And the clinic is given a dose of red and green by the painted walls and the presence of little Pashka.

The pictorial harmonies and modulations are just one part of this gripping, exhilarating film. Beanpole will be distributed by Kino Lorber in the US and Mubi in the UK.

We wish to thank Jim Healy, Emanuela Martini, Giaime Alonge, Silvia Saitta, Lucrezia Viti, Helleana Grussu, and all their colleagues for their kind help with our visit.

Thanks as well to David Vandenbossche for a correction of a movie title.

For more Torino images, visit our Instagram page.

Cynthia Hichcock (Barbara Steele), trapped in a coffin by her husband, in The Horrible Dr. Hichcock (1962).

Venice 2019: Political dramas, allegorical and real-life

Waiting for the Barbarians (2019).

Kristin here:

The 76th Venice International Film Festival is over, but I have two films yet to blog about. This will be our final entry. Soon we’re both off to the other VIFF, the Vancouver International Film Festival, from which we will of course be blogging.

Waiting for the Barbarians

I was particularly looking forward to this film, since I admire Ciro Guerra’s two previous features, Embrace of the Serpent (2015) and Birds of Passage (2018). It was rather surprising that Guerra should have a new film premiering only a year after Birds of Passage, especially since both are in their own ways epics in relation to most other art films. The fact that it stars the great stage and screen actor Mark Rylance was another factor in its favor.

Oddly enough, the morning press screenings and evening red-carpet screening of Waiting for the Barbarians were relegated to the penultimate day of the festival, Friday, September 6. It was the last of the films in competition to be shown, with The Burnt Orange Heresy (in the festival’s Fuori Concorso thread) the closing film on Saturday. By that point, quite a few of the foreign-press members had departed for Toronto or elsewhere. The Friday afternoon press conference, despite including Johnny Depp on the panel (above), was SRO, but there was no immense queue to get and and very few standing at the sides or sitting on the central stairs, as usually happens when big stars are present.

Overall the film has received lukewarm reviews, with a few more praising pieces mixed in. Both David and I, however, found it riveting. It deals with the unnamed Magistrate (Rylance), who rules a fort community on the border of a desert landscape inhabited by nomadic tribes. The Magistrate controls the place with a loose rein, meting out mild punishments for what he perceives as minor infractions by the local population. He seems content, excavating for ancient wooden rods inscribed with undeciphered texts and apparently has a relationship with a sympathetic local prostitute. He seems friendly with the people under his care and has taken the trouble to learn their language.

The countries which this border area separate are never identified and are clearly fictional places serving to portray the horrors of colonial domination by western nations. Clearly the white officials and soldiers in the film are not intended to be British. The flags on display bear no resemblance to the Union Jack and the costumes are not British. The local nomads speak Mongolian, and the main female character, referred to only as “the Girl,” is played by Gana Bayarsaiknan, a Mongolian performer.

The conflict is set moving by the arrival of Colonel Joll, an ominous figure in black, sporting bizarre dark glasses with frames of twisted wire (in the background of the frame at the top). His suggestion that he will use “pressure” to force the locals to confess their crimes turns out to be a considerable understatement. Joll ventures a little way into the the territory of those he calls “the barbarians.” He claims to turn up evidence that the local people are plotting to attack the colonial forces along the border. He has discovered this evidence though torture.

Much more description would provide too many spoilers. In general, the Magistrate tries to reason Joll and his confederates out of their plans. He also frees prisoners and nurses the native girl, who has also been tortured, back to a semblance of health. Eventually he finds himself driven to rebellion.

The film, with exteriors shot in Morocco, creates a vivid sense of a fortress community isolated from the world, and the cinematography as the Magistrate leads a small group to try and return the Girl to her people is austerely beautiful.

So far all the release dates for Waiting for the Barbarians are for festivals, including the London Film Festival. Whether it will be released in the US, as Guerra’s two previous films were, is unknown. I would suggest giving it a chance, despite some lackluster reviews. It’s another film that would lose much of its effect when streamed on a small screen.

Adults in the Room

Each year a small number of celebrities receive special awards, essentially salutes to long and fruitful careers. This year the main honors went to Pedro Almodóvar, Julie Andrews, and Costa-Gavras. We didn’t catch the awards ceremonies themselves, and the Amodóvar and Andrews ceremonies were followed by classic films of their past (Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown and Victor Victoria respectively). Costa-Gavras’ career started as an assistant director to René Clair, René Clément, Henri Verneuil, Jacques Demy, Marcel Ophüls, Jean Giono, and Jean Becker before beginning to direct on his own. Apart from his numerous features, perhaps most notably Z (1969), he has been president of the Cinémathèque Française since 2007.

Now, at age 86, he brought with him a new feature, Adults in the Room, a dramatization of the tensions and strategies of the politicians and diplomats struggling to find a solution to the Greek financial crisis.

As in most such films, the actors have been chosen for their resemblance to the historical figures. In the upper of the two images below, for example, Josiane Pinson plays Christine Lagarde, head of the IMF, and Daan Schuurmans is Jeroen Dijsselbloemm, president of the Eurogroup.

The film begins with the unlikely election of a leftist government in Greece (the Coalition of the Radical Left, or Syriza) in January of 2015. The film sticks largely to the point of view of Yanis Varaufakis, the fiercely dogged Finance Minister. His memoirs of the struggle to refinance Greece’s overwhelming debt and to keep Greece from being expelled from the European Union were the basis for the script by Costa-Gavras.

Remarkably, Costa-Gavras follows the events through an almost unbroken series of conversation scenes. These center on clashes between Varaufakis and Greece’s Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras, and on stormy meetings involving representatives of the Eurogroup and the infamous “Troika” (the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund). The Troika faction, which had bailed out the Greeks and insisted on disastrous austerity measures, absolutely refuses Greece’s demand that the loans stop and that the debt be devalued to a viable level.

This does not begin to convey the complexity of the Greek crisis, but Costa-Gavras manages to create suspense, whether or not we can actually follow exactly what is going on. There are moments when Varaufakis’ negotiation strategies are withheld from us, and we are as puzzled as the officials watching them from across the room, as in this glance-POV cut:

These meetings are linked primarily by shots establishing the various cities in which these complex and fruitless meetings take place. Often superimposed titles reveal the locations, as when the Greek Prime Minister arrives in Brussels for one such meeting (see bottom).

By the end we are not left with a thorough grasp of the intricacies of these events, which would hardly be possible for a crisis that started around 2009 and is still going on. Still, we gain a somewhat better understanding than we are likely to have on the basis of news stories stretched sporadically over over so many years. We are also left indignant at the determination of the Troika to persist in the very policies that drove Greece deeper and deeper into debt. Some have found the film tedious in its intense focus on meetings and strategies. Others I talked to after the press screenings found it fascinating. Certainly the film and its source book have chosen the brief period of the crisis (about six months) that shows most clearly and dramatically what Greece faced from the rest of the EU and why its crisis still has not ended.

For one final time this year, thanks to Paolo Baratta and Alberto Barbera for another fine festival, and to Peter Cowie for his invitation to participate in the College Cinema program. We also appreciate the kind assistance of Michela Lazzarin and Jasna Zoranovich for helping us before and during our stay.

Adults in the Room (2019).

Venice 2019: Repremieres

The Spider’s Strategem (1970).

Kristin here:

The policy at the Venice International Film Festival is to show only world premieres of films. Luckily that includes premieres of restored prints of classic films. These form a major thread in the program here, and this year had been particularly rich in older films that have been unavailable or available only in incomplete or poor prints. We have been catching up with some favorites and were introduced to unfamiliar ones.

The Spider’s Strategem (1970)

Back in the mid-1970s, David and I taught Bernardo Bertolucci’s film, which he made directly after the better-known The Conformist (also 1970). Thanks to the New Yorker print, we came to know it well, and when we wrote Film Art: An Introduction, an example of it went in and has stayed in. David analyzed the film’s storytelling principles at length in Narration in the Fiction Film.

The film came out in VHS versions in the US and UK, both out of print, but it never was released on DVD or Blu-ray. Now it returns in a stunning restoration from Fondazione Cineteca di Bologna and Massimo Sordella. (The restored version is out on Blu-ray in Japan, but without English subtitles.)

The plot involves a young man, Athos Magnani, who returns to the village where his father, who shares his name and appearance, gained a reputation as a bold leader of a small resistance group during the 1930s. He was also mysteriously murdered. The father’s mistress, Draifa, urges his son to stay and investigate the crime, and, it is hinted, to take his father’s place in her bed.

Young Magnani does investigate, but he quickly becomes uncertain as to which villagers were his father’s friends and which his enemies. He also finds himself targeted with threats of violence. Flashbacks mix scenes of past and present with no attempt to differentiate them via period props, changing ages, or stylistic contrasts. The ambiguities, which continue to the end, are not surprising, given that the literary source was a Jorge Luis Borges short story.

Whether or not one enjoys the teasing plot, the visuals are enough to provide delight. The cinematography was done by two major Italian cinematographers: Franco Di Giacomo (The Night of the Shooting Stars, Il Postino) and Vittorio Storaro, known for his bold use of color (Dick Tracy, Tucker: The Man and His Dream, and Tango). The result (see top) is like a blend of classical paintings and an Italian fruit stall.

Now all we need is a Blu-ray release worthy of the print shown here.

Maria Zef (1981)

This was Italian director Vittorio Cottafavi’s penultimate work, made after he has worked almost exclusively in television since the beginning of the 1960s. It has a pleasantly old-fashioned look, perhaps not too surprising in that Cottafavi says he conceived it in 1938, two years after the source novel appeared. He was not able to make it until 1981, when it was seen a project local to the Friuli region of northeastern Italy.

Some internet sources list it as a TV series, but IMDb and others treat it as a film. Certainly it looks like a film and seems to have no obvious pause points. But it was produced by RAI and was shot in the TV-friendly Academy ratio rather than the wider formats that were standard by the 1980s. (While I was watching it, I thought of it as a much earlier film and was surprised to find that it was made so late.)

Maria, an adolescent girl, is traveling with her irrepressible younger sister Rosute and her dying mother. They carry a cart full of domestic implements to sell. The two are taken in by their uncle, Barbe Zef, who made the spoons and other wooden housewares that the trio had been peddling. He’s a gruff fellow, and violent when drunk. Under the influence, he rapes Maria and tries to stifle her subsequent resentment as if his attack had been just a natural impulse.

The film was shot on location in the Italian Alps (above). The region of Friuli will be familiar to many film scholars and buffs who have traveled there for the “Giornate del Cinema Muto” silent-film festival in Pordenone.

The restoration was done by Rai Teche. With luck, the new print will travel abroad and introduce Cottafavi, an Italian favorite, to broader audiences.

[September 10: Thanks to blogger Manfred Polak for providing further information on Maria Zef. He provides a link to a brief piece on the film at the Cineteca de Friuli website. This piece (in Italian) says the film will play at the I Milleocchi festival in Trieste, 13-18 September 2019. The Cineteca also plans a DVD release with numerous supplements. Its earlier release of Vito Pandolfi’s Gli ultimi had optional English subtitles, so perhaps the Maria Zef DVD will as well.]

Mauri (“Life force,” 1988)

This restoration from the New Zealand Film Commission and Park Road Post Production should make available a nearly forgotten classic of New Zealand cinema. It remains the only New  Zealand feature with a Māori woman, Merata Mita, as sole director. (In 1972, To Love a Māori had been co-directed by the husband-wife team Raimi and Rudall Hayward.) Mita had previously made the first feature-length documentary by a Māori woman, Patu! (1983). Much of her career was devoted to documentary filmmaking.

Zealand feature with a Māori woman, Merata Mita, as sole director. (In 1972, To Love a Māori had been co-directed by the husband-wife team Raimi and Rudall Hayward.) Mita had previously made the first feature-length documentary by a Māori woman, Patu! (1983). Much of her career was devoted to documentary filmmaking.

The plot centers largely around an interracial love triangle. Māori woman Ramari is loved by Steve, a white farmer who was schooled alongside Māori children and retained Māori friends as an adult. His father, however, is a rabid and apparently crazy racist who tries a variety of pranks, some violent, to break up the match. Ramari loves a Māori man, Rewa, who harbors a dark secret that prevents him from marrying her.

This drama plays out against the intertwined doings of the family and circle of friends headed by the matriarch Kara. She tries to instill traditional values into her children, grandchildren, and the various troubled people she has treated as her own offspring. The film is set and shot in a tiny, declining village, Te Mata, in the East Cape area of the North Island, south of the now-thriving Hawke’s Bay winery region.

According to the biographical page linked above, “Mita said she had consciously rejected Pākehā traditions of storytelling and embraced a layered approach, in keeping with the strongly oral traditions of Māori. She told writer Cushla Parekowhai: “These are differences that Pākehā critics don’t even take into account when they’re analyzing the film.” Pākehā is the Māori word for white people.

There are rare films, and here I think of Charles Burnett’s To Sleep with Anger, that are entirely set in a specific non-white culture and make no attempt to explain that culture to a white audience. Clearly Mita was trying for the same approach. Her film met with some criticism for not following mainstream conventions of film narrative. Nevertheless, like To Sleep with Anger, Mauri draws in viewers with its drama and appealing characters. Today audiences with a greater openness to other cultures will most likely greet this restored version with greater sympathy and appreciation.

Death of a Bureaucrat (1966)

Tomás Gutiérrez Alea is undoubtedly Cuba’s most famous and revered director. Even those with the most passing knowledge of Cuban cinema will know such titles as Memories of Underdevelopment (1968) and Strawberry and Chocolate (1993). Death of a Bureaucrat is another familiar title, restored by the Academy Film Archive and the Cinemateca de Cuba. The screening was introduced by our old friend Joe Lindner, Preservation Officer at the Academy Archive.

The film is essentially a slapstick farce on a rather unlikely topic, the burial and reburial of the titular bureaucrat. He was a man who distinguished himself by inventing a machine to mass-produce the white busts of political leaders which stand in every government office in Communist countries (and which resemble the bust on the bureaucrat’s tombstone, above). The plot, however, is set off when it is discovered that as a tribute to such a genius, the dead man’s work card has been buried with him, and his widow needs it to receive her benefits.

The rest of the film is a series of escalating efforts by the man’s son to track down the exhumation order which the cemetery officials demand if they are to be able to rebury the body after the card is retrieved. Numerous stamps, signatures, and forms are required, all of which can only be provided by a single person–naturally different in each case. The hero becomes increasingly desperate and begins to try stealth, slipping into an office after closing hours and smuggling his father’s coffin into the graveyard to rebury it himself. All the while the grieving widow gathers all the ice her friends and neighbors can supply to prevent the body, kept at her house, from deteriorating.

The action is amusing enough, including one scene where a hearse is revealed to have a small plastic skeleton dangling from its rear-view mirror. The action does become somewhat repetitious and drawn-out, and one gets the feeling at times that the humor is perhaps aimed at an uneducated audience of workers and peasants, comparable to the Socialist Realism imposed upon filmmakers in the Soviet Union after the 1920s.

It’s interesting that such criticism of the workings of government would be permitted, and yet bureaucratic red tape seem to have been a somewhat safe target for Communist filmmakers, especially if presented as a sort of holdover of bourgeois practices. In the 1920s the Soviets had My Grandmother (Kote Mikaberidze, 1929) and The State Functionary (Ivan Pyriev, 1930), and Death of a Bureaucrat somewhat recalls them.

Extase (1933)

Each of the three years we have visited the Venice International Film Festival, there has been a preliminary evening where a restored early film has been shown. The first year saw the restored Rosita, the second Der Golem, both with orchestral accompaniment. This year there was an early Czech sound film, Gustav Machatý’s Ecstasy.

Having see the film only in the incomplete version that circulated in 16mm in the US for many years, I must say that I had not been impressed. The new restoration by the Národni filmový archiv, with much support from other archives, is a very different film indeed.

The story makes more sense now. It begins with the heroine, played by Hedy Kiesler-Lamarr (as she was then) as a young women who marries a wealthy older man. He turns out to have little interest in passionate love, and she is left on her own to be seduced by a young engineer working on a project near her husband’s estate. The film became famous for its scene of the heroine swimming nude, as well as her first, explicit for its day, love scene with the engineer.

The melodrama works its way out, with the rich man killing himself and the heroine, feeling guilty, leaving her lover. At this point, in the restored print, an abrupt switch to a lengthy sequence shows the engineer returning to work, with a joyous celebration of labor depicted in an imitation of Soviet films of the era. This incongruous ending to the plot comes quite unexpectedly, creating a film very different from the versions available hitherto.

Extase remains a less than wholly satisfactory film, but it now reveals its mixture of various influences of the era: the subjectivity of French Impressionism, the soft style of cinematography from the silent era, and in its ending, the propaganda and montage construction of Soviet cinema. Like Genina’s Prix de Beauté (1930), it’s an early-sound effort to preserve the aesthetics of mature silent cinema.

The evening definitely provided a new, startling version of a hitherto mutilated classic.

Thanks to Paolo Baratta and Alberto Barbera for another fine festival, and to Peter Cowie for the invitation for David to participate in the College Cinema program. We also appreciate the kind assistance of Michela Lazzarin and Jasna Zoranovich for helping us before and during our stay.

Our collaborator Jeff Smith provided a video analysis of another Alea film, Memories of Underdevelopment, for the Criterion Channel. He discusses it in this May blog post.

To go beyond our Venice 2019 blogs, check out our Instagram page.

September 10: Thanks to Hamish Ford and Lee Tsiantis for information concerning The Spider’s Strategem‘s releases on VHS and Japanese Blu-ray.

September 18, 2019: Thanks to Gareth McFeely for corrections on dates and spellings in the section on Mauri.

Mauri (1988).