Archive for the 'Film theory: Cognitivism' Category

Good and good for you

Late Autumn (Ozu Yasujiro, 1960).

DB here:

Manohla Dargis of the New York Times has just written a piece that refers to some ideas that have appeared on this site. If you see the article online, you’ll find the links to appropriate entries, but if you’ve come here after reading the paper edition of the Times, you can find the Tim Smith essay she cites here. It is a remarkable piece of work, and it’s gratifying that Dargis has called attention to it. (Tim’s video experiments have received many hundreds of thousands of downloads already.) My table-setting entry, on task-driven looking, is here.

The backstory is simple. On this site in 2008, I took a slow, unemphatic scene from There Will Be Blood as an example of how a director can subtly guide our attention without cutting, camera movement, or auditory underlining. My analysis was guided by recognition of my own responses and some knowledge of traditions of cinematic staging. Tim, in his turn, used the tools of modern perceptual research to show that we can gain firmer knowledge of directorial craft. By tracking viewers’ eye-scanning, Tim demonstrates vividly that filmmakers can shape our experience of the action on a second-by-second basis. This not only helps us understand how we grasp images. It shows that humanistic inquiry and psychological research can collaborate.

Why so unserious?

Late Spring (Ozu Yasujiro, 1949).

Those who navigate Internet eddies and flows know that dozens of responses have swirled around Dan Kois’ “Eating Your Cultural Vegetables.” Kois wants to like long, slow movies, but after trying for years, he has found that he just can’t enjoy many of them. He can mimic, even anticipate, the judgments of those who do, but in his heart he finds most of the celebrated films boring. He’s now decided to give in to his impulse and declare that he needn’t pretend to enjoy Tarkovsky or Hou Hsiao-hsien:

As I get older, I find I’m suffering from a kind of culture fatigue and have less interest in eating my cultural vegetables, no matter how good they may be for me.

As one man’s confession of guilt and fatigue, this is doubtless sincere, although its sideswiping putdowns of viewers who praise such movies suggest more calculation than humility. Still, this cry from the heart has broader implications, as many Net writers have discussed. Kois’ complaint elicited not one but two responses from the New York Times film critics A. O. Scott and Manohla Dargis. For one thing, Kois’ essay seems to offer aid and comfort to people who are afraid to try something different. Indeed, it lets them feel superior to the phonies who claim to like such films. Moreover, Kois justifies the most superficial response a moviegoer can make. Simply shrugging off a film by saying, “It’s boring!” is about as uninformative a response as saying, “It’s interesting!” And one should always be suspicious of somebody, in the name of debunkery, telling us that we shouldn’t bother to know something.

Kois’ piece exploits the special status that film enjoys in today’s culture. High and low mingle. Because movies are so accessible, and Hollywood movies are so eager to give us what somebody has decided that we want, coterie tastes are dismissed as snobbism. Things seem different in other arts. Would the Times publish a piece in which someone confessed to finding Tarkovsky’s contemporary, the Soviet composer Sofia Gubaidulina, boring? No, because to talk about her is already to enter a restricted and high-level conversation. It goes without saying that a great many listeners would be bored by her music, but who cares what non-experts think about a modern composer? Film, however, is a free-fire zone; anybody’s opinion is worth a public hearing.

I’ve kept out of the fracas because I thought Kois’ piece was silly-season fluff. Of course I wrote my own replies in my head, such as We used to have a name for this: Philistinism. I also thought that the essay operated in bad faith. Kois wasn’t as apologetic as he tried to seem. He claims humility (he “yearns…to experience culture at a more elevated level”) when really disdaining this area of cinema and considering the people who claim to enjoy it mere poseurs. The exaggerations show, I think, that this is not a serious piece:

Surely there are die-hard Hou Hsiao-hsien fans out there who grit their teeth every time a new Pixar movie comes out.

Surely not.

Still, Kois’ complaint touches on something important about film history. We have a polarized film culture: fast, aggressive cinema for the mass market and slow, more austere cinema for festivals and arthouses. That’s not to say that every foreign film is the seven-and-a-half hour Sátántangó, only that demanding works like Tarr’s find their homes in museums, cinematheques, and other specialized venues. Interestingly for Kois’ case, many of the most valuable movies in this vein don’t get any commercial distribution. The major works of Hou, Tarr, and others didn’t play the US theatre market. Sátántangó is just coming out on DVD here, nearly twenty years after its original appearance. Most of us can’t get access to the most vitamin-rich cultural vegetables, and they’re in no danger of overrunning our diet.

The race is to the slowest

City of Sadness (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1989).

For the historian, the polarization between fast pop movies and slow festival films asks to be explained. My take goes roughly this way.

From the 1940s through the 1960s, certain directors developed a new approach to telling stories. Antonioni, Dreyer, Bergman, and a few others opted for a style that relied on slower pacing and even “dead moments” that seemed to halt the narrative altogether. “Dedramatization,” it was sometimes called, and many rightly considered it a powerful innovation in the history of film as an art. But these films did get a purchase on the international movie market, often for other reasons (sex in Antonioni and Bergman, religiosity in Dreyer). They also came along at a time when there was a niche audience eager to have new cinematic experiences. (On this period see Tino Balio’s Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens.)

But artists being artists, competition grew up. The long take, for instance, got longer and more virtuosic. Miklós Jancsó, shamefully ignored today, made a series of pageants of Hungarian history in superbly sustained, intricate camera movements; some of his films have only twelve shots. But his films are sumptuous compared to what we found elsewhere. From the late 1960s through the 1970s, it seems, a new generation of filmmakers competed to make ever more austere films. They often kept the camera fixed, framed the action at a distance, and sustained the shot for many minutes. The works of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet are the high-water marks of this trend, but there were also Chantal Akerman, Theo Angelopoulos, and even Rainer Werner Fassbinder (Katzelmacher) and Wim Wenders (Kings of the Road). Werner Herzog’s successful career as a documentarist has perhaps let people forget that he once made very slow and demanding films like Fata Morgana; his Heart of Glass, screened in US arthouses in the 1970s, would surely not find a distributor today.

From a marketing standpoint, the avant-garde overplayed its hand. The new austerity came along just when Spielberg and Lucas were reinventing Hollywood. As movies got faster and louder, long-take minimalism looked perversely ascetic. Some of the directors, like Straub and Huillet, remained loyal to their project; others crossed over. It is quite a shift from Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), a 201-minute film mostly about housework, to the musical The Golden Eighties (1986) and A Couch in New York (1996). Likewise with Wenders’ Summer in the City (1970) and Wings of Desire (1987). I happen to admire both strains in these directors’ works, but there’s no doubt which is the more audience-friendly.

Today, directors who persist in long-take, slowly-paced storytelling are aiming chiefly at the festival market, which means that most of their films will be shown theatrically only, to be blunt, in France. But some of the greatest directors of our time, notably Hou Hsiao-hsien, Edward Yang, and Abbas Kiarostami, have done their best work in this mode. The US arthouse market has taken decades to discover them, through more accessible works like Flight of the Red Balloon, Yi Yi, and Certified Copy. Kois confesses to loving Yi Yi, so I’d urge him to look at Yang’s Terrorizers and A Brighter Summer Day, more rigorous but no less gripping films, though they lack the traditional arthouse bait of a charming child. Hou’s Red Balloon also has a cute kid and refers back to an arthouse classic, while Kiarostami, not normally given to couples and romances, offers us in Certified Copy a pleasantly teasing take on Antonioni and Resnais.

Minimalism of the 1970s variety got revived by 1980s American indies, notably Jim Jarmusch, but with more entertainment value. In later years he too crossed over stylistically; however unpredictable the plot maneuvers of Ghost Dog and Broken Flowers, they lack the long takes and open-ended unfolding of time we find in Stranger than Paradise. Even Kelly Reichardt, one of Kois’ targets, doesn’t give us anything like the severity of the 1970s generation. That makes the “purer” films from overseas that persist in this tradition even more off-putting. If Kois can’t take Meek’s Cutoff, as he claims, he’d find Hong Sangsoo (Oki’s Movie) or Liu Jiayin (Oxhide and Oxhide II) cinematic chloroform.

So Kois may assume that “boring” films have persisted in today’s film culture because of snobbism, but there are deeper reasons. The competition among filmmakers to push an aesthetic horizon further, the narrowing of audience tastes, the search for a budget-appropriate niche that could stand in opposition to the visual spectacle of the New Hollywood–these seem to me important factors in making slow movies a ghetto for cinephiles.

Why shouldn’t people follow Kois in giving up their vegetables? No reason, except that they’re missing some worthwhile cinematic experiences. Not all austere movies are good, but viewers who want to expand their cinematic horizons should consider the possibility of learning to look at certain movies differently. Kois can’t see that; he thinks that people who like the movies that bore him are usually phonies. But I believe that some of those admirers have developed a repertory of viewing habits that adjust to different cinematic traditions. If you can like both Stravinsky and rock and roll, why can’t you like Hou and Spielberg?

Look again, closer

Voyage to Cythera (Theo Angelopoulos, 1984).

This is the prospect opened up by Dargis’ latest article. She suggests that Kois’ response isn’t wholly based on taste. It may stem from literally not knowing how to look at certain kinds of movies.

Kois’ article treats most defenses of slow films as a matter of hand-waving and you-see-it-or-you-don’t attitudinizing. Again, he has a point: Those reactions are common, I think. The fact that cinephiles must face is that this sort of film is very difficult to talk about. We can point out the creative choices in Hollywood because narrative in some degree drives everything we see and hear. But when narrative relaxes, most viewers don’t know what to look or listen for.

The problem has haunted me for decades, ever since the 1970s when I took an interest in Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer, and Mizoguchi–all filmmakers felt, at the time, to be slow. I failed to come to grips with the problem in my 1981 book on Dreyer; I even anticipated Kois in calling Gertrud (another item that would never grace theatre screens today) boring–but I took that to be a good thing, as a challenge to conventional viewing habits.

What can I say? I was young. Since then, I think I’ve come up with better ways of talking about the other directors I mentioned, as well as some in their camp, such as Angelopoulos and Hou and Tarr. A lot of my answer comes down to the way, pace Dargis and Smith, they structure our attention.

My arguments are set out in the places I mention in the tailpiece of this entry. In brief, these filmmakers become engaging, even entertaining, when we realize that they are to some extent shifting our involvement from characters and situations to the manner of presentation. Not narrative but narration is what engages us. And we need, as Dargis points out, some schemas for grasping these alternative patterns. We have robust and refined schemas for following a story, but grasping the dynamics of narration, the how as well as the what, takes more practice, and perhaps some instruction from critics.

The process is like taking in an opera on two levels: following the stage action but also registering the patterns, the emotional highs and lows, of the music that accompanies–and sometimes overwhelms–it. Let Papagena and Papageno stammer each one’s name again and again. The repetition isn’t needed for the drama, but it’s thrilling on sheerly musical grounds.

Now imagine that sort of development transposed to cinema, in which we can appreciate, at one and the same time, not only the story’s unfolding but the patterns that present it. The supreme master of this possibility, I think, is Ozu, perhaps cinema’s Mozart. But you can find the same qualities in more somber key elsewhere. For example, in watching Angelpoulos’ Voyage to Cythera, I think that you have to be prepared to see the arrival of track workers in yellow slickers, visible through the speckled window pane in the shot above, as a kind of visual epiphany, the quiet equivalent of a stunt in a summer tentpole picture.

Given a narrative mandate, we’re on the lookout for pictorial factors that affect the dramatic situation. But when narrative slows, other things, maybe not of narrative moment, pop out, like the yellow-garbed train workers on their handcar. At such moments, it’s not that our eyes roam around aimlessly; it’s that the director guides us in a different way, toward a visual search that isn’t wholly driven by plot considerations. Here’s a shot from Ozu’s End of Summer (1961).

The principal action is a party of young people singing. But the faces are no more important than the gleaming drinks on the table, a little suite of colors and shapes that become fascinating in themselves. (For instance, several of the liquids and bottle labels sit along the same horizon line, regardless of how far the drinks are from us.) You don’t discover this half-gag, half-still-life by groping: Ozu has lit it and composed it so that you’re invited to discover it. He has found a way to activate what in most movies would be filler material. And if you think that noticing colors and shapes on the tabletop is just trivial, consider that we enjoy staring at the same sorts of patterns in an abstract Kandinsky. Or is he cultural roughage too?

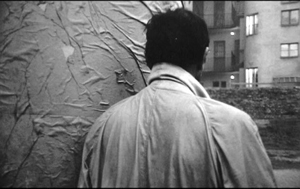

In an Ozu film, even though he cuts rather fast, we’re given time to see everything. But this isn’t random rummaging. It’s visual exploration guided by Ozu’s decisions about composition, lighting, and color. Something similar, I think, is going on with Tarr, although there it’s more a matter of texture and tactile qualities. His people shamble through mud, oily puddles, dusty corners, and tearing winds. In one shot of Damnation, a rain-soaked wall shrivels to match a wrinkled topcoat.

The story is still going forward, but by turning his protagonist from us and aligning him with the wall, Tarr has given his shot an extra layer of sensuous appeal. Try to remember the way any wall looked in Transformers 3, before it got blasted to rubble.

Slow movies let us look around, and good slow-movie makers give us something to see when we do. But what do we do when these accessory appeals don’t just accompany the narrative but swamp it? What if we lose track of the characters? The film may steer us to pictorial or auditory qualities that take over our perception.

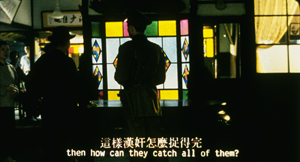

The authorities are looking for a man in the family in Hou’s City of Sadness, but you have to rely almost solely on dialogue to identify what’s going on and who’s speaking.

The sheer pictorial beauty of the shot becomes a sort of anti-narrative pretext. But if you’re alert, you won’t take the plot off the table, because at one crucial moment a figure flashes through the far left background, more or less fully lit, who may be the suspect the cops are seeking.

Sometimes you have to destroy narrative in order to save it.

Hou asks that we engage with his distant, fixed images in a complex way, being patient but vigilant, enjoying abstract geometry while also sustaining old-fashioned suspense. It’s this dynamic between story and style, fastening on plot elements but also discovering accessory pleasures and patterns, that I think constitutes one delight of the sort of films that Kois finds boring.

Add Bresson, Mizoguchi, Dreyer, Tarkovsky, and others to my list of directors whose very different styles invite us to explore what the rapid pace of most narrative cinema refuses to dwell upon. These filmmakers invite us to grasp the space and time of a scene in a fresh way. The details and dimensions of a world surge forward, not simply as a backdrop for characters hurtling toward a goal, but as something valuable in their own right. For some viewers, me included, they do more. They also ask you to transfer those viewing skills to life outside the theatre. They encourage you to find a new way to look at our world.

Not all slow, minimalist movies are good. That’s why I think critics are obliged to rebut Kois with careful analysis, not the gaseous generalities about sublimity and eternal mystery to which we too often resort. Digging deeper, we can not only answer skeptics but expand our understanding of how cinema works. These films have opened windows for many of us. Why should we keep them to ourselves?

First, thanks to Manohla Dargis for enjoyable correspondence about these issues.

Tim Smith’s blog, Continuity Boy, is a good way to keep up with his energetic and expanding research program.

Dargis mentions the invisible gorilla experiments of Chabris and Simons. I talk about their relevance to film here and here.

Kristin has written on comparable matters in Tati; she even wrote an essay on M. Hulot’s Holiday called “Boredom on the Beach.” (It and an essay on Play Time are in her book Breaking the Glass Armor.) Tati’s films, in their spasmodic pauses and shamelessly repeated or sustained gags, could also count as part of the postwar dedramatization trend.

My initial arguments about different registers of viewer perception and cognition were made in Narration in the Fiction Film (1985). My case for Ozu is in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, available online. More recently, I’ve become interested in cinematic staging and have concentrated on challenging directors like Mizoguchi, Angelopoulos, and Hou; see On the History of Film Style (1998) and Figures Traced in Light (2005). All of these “slow” filmmakers ask us to be sensitive to unusual sorts of narrative patterning, and some purely non-narrative patterning. More thoughts on these matters can be found in The Way Hollywood Tells It (20006) and Poetics of Cinema (20007).

On this site, you can find similar lines of argument, especially about Béla Tarr, Mizoguchi Kenji, and silent directors like Louis Feuillade, Victor Sjöström and some Danish creators. See director entries for Hong Sangsoo, Liu Jiayin, and others mentioned above. Later this month I hope to post a bit more about how directors guide our attention without recourse to fast-paced editing–before editing was really invented.

Sátántangó (Béla Tarr, 1994).

Cognitive scientists 1, screenplay gurus 0

Kristin here:

The annual meeting of the Society for the Cognitive Study of the Moving Image is currently taking place at Elte University in Budapest. It runs from June 8 to 11. It must have started off very well. Barbara Flueckiger posted this comment on the opening keynote address on Facebook: “Just attended an absolutely fascinating and inspiring talk by Talma Hendler, a professor of psychiatry and neuroscience: ‘Brain Shows Where the Drama Is. A Call for an Empirical Neurocinematic Agenda.'”

Last week David posted a new web essay on “common-sense film theory” as a way of participating from afar in the work going on in Budapest. Now it’s my turn to post a SCSMI-related item.

The mirage of the second-act desert

Twelve years ago I published Storytelling in the New Hollywood (Harvard University Press). It included a claim that most classical Hollywood feature films have four acts, lasting roughly 25-30 minutes each, adding up to a film of from 100 minutes to two hours. This claim ran counter to the old notion, popularized by Syd (Screenplay) Field, that Hollywood movies (and, according to Field, all feature narrative films) have three acts of 30, 60, and 30 minutes respectively.

My book analyses ten films in detail, dividing them into their four parts: Setup, Complicating Action, Development, and Climax (usually including an epilogue). I also have an appendix listing ninety additional films that I timed by large-scale part, ten for each decade from the 1910s to the 1990s. My conclusion was that most of these films stuck to the four-part structure with each part within five minutes either way of lasting a half-hour. Some of the exceptions were actual three-act films (e.g., Adam’s Rib) and others were longer films. Amadeus, one of my ten main examples, is 160 minutes long and has five large-scale parts. (“Large-scale part” was the rather cumbersome term I employed in the book, trying to avoid the misleading word “act.” I have to admit though, that there’s little chance of people discontinuing “act” and switching to “large-scale part.”)

I also defined the “turning point” that Field says divides acts more concretely than he does, specifying that it usually results from moments when the main characters formulate or modify the goals that drive the narrative forward. (I expand upon the relationship of goal shifts and turning points in a previous entry.)

Unlike Field and other screenwriting “gurus,” I allow for exceptions to my four-part schema. The Pink Panther doesn’t have a turning point until over 52 minutes in; the lengthy early part of the film consists of a bedroom-farce situation of male sexual frustration that makes absolutely no progress toward the putative subject of the film, the theft of a valuable jewel. As far as I can tell, It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World has no turning points at all. I remember thinking it was quite funny when I saw it as a child.

Some screenwriters have read the book, and some who teach screenwriting courses assign it as a textbook. At least it’s still in print, which is something to be grateful for at my age.

Since the book was published, it certainly hasn’t knocked out the conventional view that films have three acts. Not infrequently I read a review in Variety or another specialist journal that refers to the last quarter of the film as the “third act.” The idea that films fall into chunks lasting 30 minutes, 60 minutes, and 30 minutes, no matter how counterintuitive or inaccurate, is too entrenched to be dislodged, apparently.

Still, I have the consolation that I’m apparently right. Other people have tried out my claim and found it to work. Creative Screenwriting gave a very kind review to my book (in its March/April 2002 edition, not online). D. K. Holm, the reviewer, was inspired to test out my system on the next three films he saw in theaters. He declared that it worked as predicted for The Shipping News, In the Bedroom, and even Ali, a five-act film. (My claim is that longer films don’t stretch their four acts. They add more, roughly 30 minutes long, for every half hour beyond the standard two-hour feature. Roughly half an hour apparently seems to create a pleasing balance as far as Hollywood practitioners are concerned—whether they’re aware of it or not.)

Real scientists at work

Now James E. Cutting, whom we enjoyed meeting and talking with at last year’s SCSMI conference (David devoted part of his report on the conference to James’s work), has collaborated with two of his graduate students, Kaitlin L. Brunick and Jordan E. DeLong, on a quantitative study related to Storytelling. They set out to test the whether the four large-scale parts of a classical film are reflected on the stylistic level. Specifically, do shot lengths and the use of non-cut shot transitions (fades, dissolves, and the like) vary in a patterned way across or among the parts?

It’s exciting to see cognitive scientists study claims that I’ve made on the basis of close film analysis. David has had his claims about staging and attention in There Will Be Blood confirmed by Tim Smith’s eye-tracking research on the same sequence. Now the results of Cutting, Brunick, and DeLong’s work relating to the four-part structure have been published in Projections (Vol. 5, issue 1, Summer 2011), subscriptions of which are included in SCSMI membership. Luckily I didn’t know this article was on the way, or I might have been in some suspense to find out whether my model worked. (This and other articles on film are also available online, linked from this page that lists the work on film published by James and his colleagues.)

As the authors’ starting point, they accepted my four-part structure. Or as they put it:

We find Thompson’s argument persuasive and her data remarkably clean. Nonetheless, the division into acts is built on a detailed analysis of the narrative, and we work from the physical properties of film. Many observers might agree on act divisions, but these divisions would not necessarily be reflected in any physical measure of a film’s shots and transitions. Thus, without prejudice as to what we might find, we sought data in shot lengths and in shot transitions that might corroborate Thompson’s analysis. (p. 4)

The team used 150 films they had previously studied in their work on editing patterns and their possible correlations to human attention. Of these, some were eliminated because they were too long, so that the statistical work could concentrate on films with four parts. I cannot claim to be able to follow all the statistical manipulations the data from these films were put through—though I can tell from the information in the footnotes that the degree of probability for some of their results indicated an amazingly small chance of error.

The figure at the top is a “scatter plot” of shot lengths for 143 Hollywood films from the period 1935 to 2005. These figures have been statistically adjusted in ways that allow the films to be compared despite their differing lengths. (I have no idea how this sort of thing is done. You’ll have to see the explanation in the article.)

One striking revelation of this chart is that the lengthiest shots in the films occur at the beginning, end, and at the one-quarter, two-quarter, and three-quarter points. Moreover, the “scallop” pattern of rising and falling average shot lengths shows a “tendency toward intensification of films near the middles of acts, where shot lengths become slightly shorter.” The ASLs were found to be as much as 1.1 seconds shorter than in the early and later portions of the acts.

Luckily I was right about the four parts. But beyond that the authors came up with results supporting my claims about the functions of the plot’s third part, the Development. Here’s how.

As part of the study, the authors tackled the question of where non-cut shot changes fall in relation to the quarters of films. Non-cut changes are fades, dissolves, and the like. It turns out, not surprisingly, that quite a few of them come early on, since the exposition may move among time and places setting up the basic premises of the narrative. But the rest tend to come in the third quarter, the Development. That makes sense to me. By my definition, the Development is essentially the stretch of action where most of the major premises, goals, and obstacles have been established. Before the climax can begin, the protagonist usually struggles against obstacles, usually provided by the antagonist. Often relatively little happens in the Development to forward the action, at least in comparison with the other three parts. At the Development’s end, some vital last premise is introduced that allows the action to move into the climax portion, where the plot moves forward relatively quickly and no more major premises are introduced.

The Development might contain extra fades and dissolves for two reasons. First, a surprising number of films have a montage sequence shortly after the middle turning point. The one depicting Michael Dorsey’s rise to fame as Dorothy Michaels in Tootsie is one such. Second, since the Development often is the section where time passes until the point where the climax can begin, one would expect fades or dissolves to cover temporal gaps. I’d have to go back and watch a bunch of films to confirm those hunches, but they seem logical.

My main purpose in writing Storytelling in the New Hollywood was to show that the principles of classical narrative construction formulated in the 1910s and used throughout the studio era are still operative today. Despite film reviewers’ complaints that action and special effects have come to substitute for story appeal in modern mainstream films, the kinds of films they find so shapeless do usually stick to the same four-part structure, contain goals and conflict and the rest of the principles that have been in effect for decades. Cutting, Brunick, and DeLong’s work bolsters this claim about classical narrative’s stability over time. They find that “there are no obvious differences in these patterns for films of different eras.” (p. 8.)

This issue of Projections has other articles applying a cognitive-science approach, and with luck future issues may contain some of the papers we have been unable to attend at this year’s conference.

James, Kaitlin, and Bradford have set up an online overview of their research in progress, “Shot Structure and Visual Activity: The Evolution of Hollywood Film.” The graphics and type are quite small, but right-click on the page and click “Marquee Zoom,” which brings up the little magnifying glass that allows you to enlarge it multiple times.

For online applications of the idea of four-part structure, see David’s essay on Mission: Impossible III and his blog entry on Source Code.

Jordan DeLong, Kaitlin Brunick, and James Cutting at annual convention of SCSMI, Roanoke 2011.

Madison calling Budapest: Can you read me?

Can you look at this picture without smiling? I think it’s hard, for reasons that relate to one thread of the essay here. Thanks to Levi Buchhuber, age eight months, and Jim Cortada, grandpa.

DB here:

Next week several dozen bright, energetic researchers will be crowding into conference rooms at Elte University in Budapest for the annual meeting of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. Full details on the event are here. As usual, I expect that a hell of a time will be had by all.

I’ve discussed the purposes and projects of the members of this dynamic bunch on earlier occasions. If you want a rundown, I’d suggest reading the items in chronological order:

*I sketch out the SCSMI project in this entry. There are more ruminations in two run-ups to the 2008 Madison SCSMI get-together (here and here), and one a year later summing up that event.

*For a report on the wonderful 2009 Copenhagen convention, go here.

*I try to sum up the wide-ranging 2010 Roanoke powwow here, while a recent blog, “Molly Wanted More,” can be considered an echo of that event.

*For an utterly fun introduction to some of the research on display at SCSMI, head to one of our most popular entries, the guest blog by Tim Smith called “Watching you watch THERE WILL BE BLOOD.”

This year’s paper line-up is especially enticing, and the prospect of seeing so many old friends is even more thrilling. Alas, for reasons beyond our control, Kristin and I aren’t able to attend. As the date draws near, my need to stay home saddens me more than I had expected it would. I must content myself with directing you, with all the fervor I can muster, to the event. Many of our members have told me that their first visit was life-changing, providing them a whole new social network that would encourage their research. Moreover, I notice that every year several participants tell me that they think this one was the best session yet. We’re just getting better, and we’re not going away! I should also alert you to the likelihood that many of the papers will be published in the SCSMI-affiliated journal Projections.

I thought, though, that I might participate a little at long range. So I’ve posted a web essay that sets out, in less technical terms, what my proposed paper for the convention would have tried to say. The essay, “Common Sense + Film Theory = Common-Sense Film Theory?,” reflects an effort to rethink ideas about filmic comprehension that I set out in Narration in the Fiction Film in 1985. This book was one of the first efforts to explore how findings in cognitive science might help us make progress in understanding cinematic storytelling.

I’d stand by much of what I argued there, but in the light of further thinking and later research (much of it conducted by SCSMI members), I wanted to float some ideas that recast and correct my arguments in the book. (Yes, I hope I’ve learned something in twenty-five years.) Some of my more recent notions are available in Poetics of Cinema and under the Film theory: Cognitivism category on this blogsite, but the conference provided a good occasion to submit to the sort of friendly but pointed critique at which my SCSMI colleagues excel.

Of course, give me another twenty-five years and I’ll probably find fault with what I say now. Others won’t need so much time.

Start with this question, which I think is one of the most fascinating we can ask:

What enables us to understand films?

Continue reading here.

To my SCSMI cohort: I wish you a superb gathering. See you next year, at Sarah Lawrence!

Joe Anderson, co-founder of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, opens the 2010 session at Roanoke.

Molly wanted more

The Crime of M. Lange.

DB here:

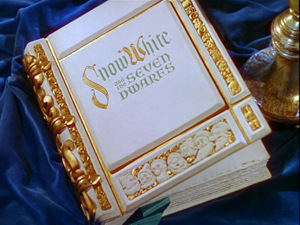

I was watching Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs some years ago with a friend’s three-year-old daughter. Molly hadn’t seen the movie before, and she watched it in a fascinated silence. At the end, Snow White and the prince leave the dwarfs and ride off into the distance.

At this point Molly cried, “More!”

This surprised me. How could she know, on her first pass, that the story was ending?

In and out

It has no name that I’m aware of, but it’s one of the most common conventions of movie storytelling. At the end of the film, the story world closes itself off from us. The characters turn away, perhaps walking into the distance. We may get a distant long shot of the scene. In some cases the camera accentuates this withdrawal by craning or tracking away from the action.

At the end of The Wild One, the biker hero smiles at the woman he’s met and goes out into the street. After exchanging a glance with the ineffectual sheriff, he swings his motorcycle around, his back to us. Cut to an extreme long shot as he rides off.

Once you notice this sort of ending, you’re likely to think about beginnings. Sure enough, we find some symmetry. A movie often visually brings us into the story world. Most common is an inward progression, moving from a large view to the central space of action. As far back as 1919, Griffith started Broken Blossoms with an overall view of the harbor and an explanatory title.

Then we have a gradual entry into the Chinese neighborhood, moving steadily from long shots to closer views. The young ladies we encounter aren’t major characters in the plot, but we’re still slowly drawn into the story world.

At the film’s end, Griffith’s cutting will manage a parallel withdrawal, from the lovers to the temple and back to the waterfront view.

In fact, Snow White starts with a comparable, if somewhat smoother shift inward, from the exterior of the Queen’s castle then, via camera movement and dissolves, to the Queen at her mirror.

This last shot reminds us that alternatively, a film can start with the characters coming forward, as if to meet us. This is the way The Wild One begins.

Any sort of combination is possible. The Silence of the Lambs starts with Clarice Starling climbing up a hill toward us and pausing long enough for us to register her as a protagonist.

She then turns and runs off into the forest. If this were an ending, we might see her go off further and further into the distance. But this is an opening, so we follow her with a tracking shot forward, letting her lead us into the story action. Soon we’re back to the frontality and intimacy of an opening passage, like the shot of the Queen.

At the end, Jonathan Demme gives us a pair of “farewell” shots. The first occurs when Clarice, who’s been talking to Dr. Lecter on the phone, hears the line go dead. We pull away from her.

The second farewell shot takes place on Lecter’s end in a Caribbean island. It shows him rising to follow Chilson and walking away from us, to be swallowed up into the crowd.

The Silence of the Lambs takes leave of its protagonists in two alternative ways: If the camera doesn’t move away from our characters, it seems, then the characters move away from the camera. They may even seal themselves off, as when a flight attendant pinches shut the curtain at the end of The Hunt for Red October.

So when we speak of films’ “openings” or “closings,” it seems that we are often talking about a world that initially invites us in but will finally expell us, however slowly and politely.

See it here!

Researchers play Jeopardy! Their answers always take the form of a question. Most film critics work in the declarative mode (“The performances are gripping”), but ideally the academic film researcher works in the interrogative mode. What is this pattern of beginnings and endings doing in movies? How does it work? How did it become common? And how do we learn it?

Take the first question, about the purposes and functions of the device. At one level its neat symmetry mimics the sort of frame that we find in other sorts of narrative, particularly oral storytelling. Fictional stories need to be set off from the surrounding flow of discourse. When we hear “Once upon a time,” we all know a fairy tale is starting. There are equivalents in other oral traditions, as in “Here is a tale . . . .” (Yoruba) and “See it here!” (Hause).

Likewise, oral storytelling traditions use formulaic final lines. In our fairy tales, it’s often “And they lived happily ever after.” Native American folk tales may finish with the storyteller simply saying, “The end” or “Tied up.” African oral epics sometimes use the formula “That is what I know” or “Let us leave the words right here.”

In fact, I cheated a little with my examples from Snow White. The film actually is bracketed by a literal opening and closing.

In film, however, the symmetrical structure is only part of the answer. While a film can copy the literary idea of opening and closing a written text, the medium as a whole offers something more. Thanks to the visual nature of movies, the widening or closing-off of the story world can mimic the act of our entering or backing out of a tangible situation. That’s what we see in Snow White and my other examples. In a sense we greet the characters, and after spending some time with them we bid them farewell. The sense of entering and leaving their world is harder to capture so concretely in literature or theatre.

So we need a more specific account of the convention. Surely you’ve thought about the most obvious candidate. The entry/ leave-taking pattern mimics our activities as perceiving, socially inclined people. For creatures like us, to encounter a new situation or setting simply involves approaching it or letting it approach us, then becoming part of it and fixing our attention on its details. At a party, we amble closer to a knot of people we want to talk with, or someone comes up to us. Sooner or later that encounter ends or trails off, and we withdraw or turn away or watch when others depart. More poignantly, the extreme long-shot option can recall moments when a car or bus or train carried us away from our loved ones. In any case, thanks to moving images the salient features of this very common experience can be made tangible for viewers.

This convention, we might say, is just natural. Molly, who had already logged three years of social experience, could plausibly make the analogy with ease. She recognized that her encounter with the world of Snow White was coming to an end–the characters were leaving her–and could express her regret.

This common-sense answer is, I think, basically right. But it needs to be fortified against some objections.

For one thing, not all films use this convention. Lots of films start with close-ups of particular items in an environment, plunging us into details without a gradual entry (below, Back to the Future; Muriel; ou le temps d’un retour).

And lots of films don’t end with marks of withdrawal or closure. They end on close views, often of the characters or a significant object (below, Le Silence de la mer; Sorry, Wrong Number).

If this pattern were biased by our natural proclivities, wouldn’t it be more common than it is? And if it comes so naturally, why wasn’t it present at the start of cinema, as soon as people started telling stories? Most of the storytelling techniques we now consider very user-friendly, like cutting and camera movement, emerged after many years of moviemaking. It’s akin to a problem in the history of painting: Why did painters need centuries to learn to imitate the way things look?

Moreover, the naturalness can look pretty unnatural. Nobody lies down in the middle of the road to let a horde of bikers sweep by, as in the beginning of The Wild One. The high angle at the end of the movie doesn’t imitate anybody’s likely point of view; it mimics, if anything, a godlike perspective we almost never get. Similarly, the cuts and dissolves that link the views in Broken Blossoms and Snow White don’t have any parallel in our real experience. Tied to our bodies, we can only move toward or away from situations in real time, step by step. The time-compression and freedom of position we get on film are far from natural. In sum, the concrete ways in which this immersion/ withdrawal pattern shows up in actual movies suggest that the films aren’t imitating the literal vantage points we might assume in the real world. There is a lot of contrivance going on.

Real life, amped up

So the convention has some roots in our perceptual and social experience, but filmmakers have streamlined and sharpened it for our uptake. Another example of this process, which I discuss here, involves actors’ eye behavior. Film actors start with normal patterns of looking and blinking, but they modify them in order to signal emotional states and to concentrate our attention on the drama. Similarly, the schema of entering/ leaving a milieu derives from our common experience, but it can be simplified and stylized through cinematic techniques that have no correspondence in our normal experience. All that matters is that the result preserves the core of that schema.

As filmmakers simplify our perceptual and social experiences, they amplify them as well. Movie characters stare at each other more intently than we do in normal life. The actors are stripping off everyday noise (blinks, averted looks) in order to create cleaner, exaggerated signals of mutual attention to the dramatic situation. Likewise, a steep high angle like that ending The Wild One or the pointedly closed curtains of The Hunt for Red October exaggerates the sense of departure and conclusion, giving the action a weight it wouldn’t have in ordinary life.

Why don’t all films use the entry/ retreat convention? I think we should consider such conventions to be tools. They arise in particular filmmaking traditions, perhaps through trial and error, and get refined for different purposes. Some filmmakers might never use them, or knowingly refuse them to create different reactions, or play games with them (as Resnais does at the start of Muriel). But when filmmakers want certain effects, these tools are ready to hand. If you want to ease your audience into the story world, a slow entry pattern works very well. It’s so familiar that the viewer can overlook its contrivance and concentrate on the story information.

So Jeopardy!-style, we have new questions. Has the opening/ closing device spread because it is a very accessible, spontaneously understood convention? Or is it because filmmakers in other cultures have mechanically copied Hollywood? Perhaps it’s like a tool that originates in particular cultural circumstances but which can be useful all over the world. The Phillips-head screw was devised for the US automotive industry but is now a universal gadget. Over time, such tools become more widespread, perhaps dominant. But a tool can always be refused if the task changes.

There’s still a mystery, though. Assuming that viewers understand these image-clusters as signaling beginnings and endings, how did that understanding come about? How, and when, do people learn the conventions? If they are quickly learned, is that because they play into inclinations of our minds?

My best guess for now is this. We tend to think that all artistic conventions are equally hard to learn, but that’s probably not the case. The conventions of Cubist painting demand more effort and knowledge than the conventions of perspective drawing, and that’s probably not just because we’ve seen more perspective pictures across our lives. Likewise, mastering the conventions of Structural Film demands more time and trouble than mastering those of popular genre filmmaking. It seems likely that some conventions rise to dominance because they fit most viewers’ prior inclinations rather well. For example, we are creatures who interact socially in face-to-face manner. Shot/ reverse-shot editing is unfaithful to our ordinary experience in many ways; cuts provide instant changes of viewpoint we can’t achieve in real time and space. But shot/ reverse-shot cutting preserves the familiar social pattern of turn-taking and conversational flow, so it’s comparatively easy to learn.

Still, I don’t have a full answer. My questions bring us back to Molly. If she had seen Snow White before, we might say that she remembered that the film ended at this point. But she hadn’t seen the film before. So does her demand for more indicate that she generalized from her experience of other films? Did she have already a degree of “narrative competence,” allowing her to recognize certain types of cues? Is her competence full or spotty? (Maybe she gets endings, but not characters’ intentions, or goal orientation.) And how did she acquire that competence? Quickly or slowly?

Maybe some researchers have already explored how children master narrative framing of this sort. (I’d welcome correspondence on the matter.) My hunch is that Molly grasped the cinematic convention, perhaps on limited exposure, because she recognized the core perceptual and social experiences it preserves. Leveraging this insight, perhaps, was some understanding of narrative architecture generally. More basically, it may be that as social animals we’re tuned by evolution to detect fairly quickly some constant features of interactions with our peers.

In any case, I’m betting that Molly wasn’t simply mastering a convention cut off from everyday life, like algebraic equations. To learn anything, you already need to know a lot. Cinematic storytelling isn’t, as some semiologists once thought, a highly arbitrary sign system. It piggybacks on our experience of the world–our knowledge, certainly, but also our most routine ways of sensing and thinking. Not least, understanding movies taps skills associated with our social intelligence. More on this in a future entry, I hope.

This is only an anecdote, but I hope it provokes readers to think about the broader issues I raise. I floated these ideas in my closing address for the convention of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, on 5 June 2010. I thank the members of the audience for their contributions to that discussion. Incidentally, this year’s meeting is coming up, in Budapest this June. For more on SCSMI and the sort of issues broached in this entry, go to this category on this site.

My basic argument for a “moderate constructivism” in understanding film conventions is developed in the 1996 essay “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic Vision,” reprinted in Poetics of Cinema (2008), 57-82. I discuss the entry/ withdrawal pattern as a holistic strategy in a later essay in that collection, “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative”, 94-95. An earlier, more fancily titled piece puts the pattern in the context of a different argument: “Neo-Structuralist Narratology and the Functions of Filmic Storytelling” in Marie-Laure Ryan, ed., Narrative across Media: The Languages of Storytelling (2004), 209.

It’s worth mentioning that, like Snow White, the images at the start and conclusion of Le Silence de la mer are enframed by a book–in this case, shots of the original book by Vercors. This iconography is of course common when a film wants to emphasize the literary origins, though in some films, like Dreyer’s, the device of the film as a replay of an already-written text plays a more complicated narrative role. I talk about that in my book The Films of Carl Theodor Dreyer (1981).

The research on children’s understanding of stories is vast and detailed. Alison Gopnik briskly summarizes the evidence that even very young children have surprising narrative competence in The Philosophical Baby (2009), chapters 1 and 2. The pioneering source here, at least for an amateur like me, was Katherine Nelson, ed., Narratives from the Crib (1989).

The Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans. As in many films, the final shot addresses the viewer in a comparatively overt way.