Archive for the 'Film scholarship' Category

The book stops here: Theory, practice, and in between

Tinpis Run (Pengau Nengo, 1991).

DB here:

Apart from things I’m reading for research (academic monographs, 1940s Hollywood novels, star bios and autobios), the film books I like best are blends. They bring together information, ideas, and opinion. I learn some facts about films and their contexts. I encounter some concepts that illuminate those facts. And I get introduced to some arguments about the best way to understand the information and ideas. In my ideal world, the blend winds up answering some questions—maybe questions I’ve thought about, maybe ones that never occurred to me.

I especially like books that have one foot, or toe, in filmmaking practice. The poetics of cinema I try to practice is, from one angle, an effort to grasp the principles underlying filmmakers’ creative choices. Sometimes those choices are announced by the filmmakers; sometimes we have to reconstruct them on the basis of the films and other data. So for me a drastic split between theory and practice isn’t very informative.

These pronunciamientos are but prelude some comments on books that push several of my buttons. Maybe they’ll do the same for you.

Philosophy goes to the multiplex

Stagecoach (1939); True Grit (1969).

What book brings together Cézanne and Tony Soprano, Gregory Peck and Simone de Beauvoir, Plato and South Park, The Twilight Zone and Wittgenstein?

Okay, I know the answer: Practically every book by a littérateur convinced that Great Big Theory gives you a way of talking authoritatively about anything, especially pop culture. So I rephrase my question: What book brings together these and many more items with care, rigor, and infectious amusement?

That narrows the field quite a bit. A strong candidate is a book that has chapters like “What Mr. Creosote Knows about Laughter,” “Andy Kaufman and the Philosophy of Interpretation,” and “The Fear of Fear Itself: The Philosophy of Halloween”— not the movie but the holiday itself.

The short answer to my question: Noël Carroll’s new collection of essays, Minerva’s Night Out: Philosophy, Pop Culture, and Moving Pictures.

Noël Carroll isn’t merely the most important philosopher ever to write about popular culture. He has been for decades a major force in film theory and criticism, as well as a philosopher making contributions to moral and legal theory, historiography, and a welter of other areas. His fertile mind and prodigious typing skills have combined to produce over fifteen books and a list of articles running to triple digits.

It’s not just quantity, of course. For those of us in media studies, Carroll has been the most well-informed and adroit analyst of trends in film theory. His Philosophical Problems of Classical Film Theory (1988), Mystifying Movies: Fads and Fallacies in Contemporary Film Theory (1988), and Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies (1996, coedited with me) have proven enduring contributions to the debates about the best ways to understand the nature and functions of cinema. He is, as you can tell, a controversialist. Like all good philosophers, he’s devoted his life to getting the ideas right. Over the same period, Carroll has proven himself a wide-ranging practical critic, discussing classic silent films (especially comedy), modern avant-garde work, and Hollywood movies from the 1930s to the most recent releases. This isn’t to slight his important work as a dance and television critic as well.

It’s not just quantity, of course. For those of us in media studies, Carroll has been the most well-informed and adroit analyst of trends in film theory. His Philosophical Problems of Classical Film Theory (1988), Mystifying Movies: Fads and Fallacies in Contemporary Film Theory (1988), and Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies (1996, coedited with me) have proven enduring contributions to the debates about the best ways to understand the nature and functions of cinema. He is, as you can tell, a controversialist. Like all good philosophers, he’s devoted his life to getting the ideas right. Over the same period, Carroll has proven himself a wide-ranging practical critic, discussing classic silent films (especially comedy), modern avant-garde work, and Hollywood movies from the 1930s to the most recent releases. This isn’t to slight his important work as a dance and television critic as well.

This focus on film theory stems from the fact that Noël’s first Ph.D. degree was in film studies. But soon afterward he went on to get a second Ph.D. in the philosophy of art. His cinema research was always philosophically informed, but once he became a card-carrying philosopher, he commuted between two academic areas. He helped found the broader movement called Philosophy of Film, and he continues to write on a lot of different topics. His Humour: A Very Short Introduction is due out in a couple of weeks.

Minerva’s Night Out scans the range of his interests—not only all types of media (which he genuinely enjoys) but a variety of the philosophical puzzles they pose. These he tackles with verve, patient but not plodding analysis, and a range of references that make you wonder if this guy has seen and read pretty much everything.

Here’s the sort of thing that Noël thinks about. We all know that to enjoy a movie fully we often have to appreciate the way in which a star’s performance builds on previous roles. But there’s a problem. The fictional world of a film makes only certain types of knowledge relevant to our experience. At the center of this knowledge is what Carroll calls the “realistic heuristic,” the premise that all other things being equal, the things happening in the fiction are assumed to operate under the laws of our everyday world. Sherlock Holmes (whether incarnated by Basil Rathbone or Benedict Cumberbatch) is presumed to have lungs like the rest of us, unless we’re told otherwise. Likewise, it is true in the fiction that a room’s walls are solid, while they might in reality be fake. If I see the walls as painted sets or green-screen mattes, then I’m not responding to them as part of the story world.

The same attitude shapes our sense of the unfolding plot. Armed with the realistic heuristic, we have to assume that characters’ destinies are open, that many things can happen to them (as with us). But the principles by which a movie fiction is constructed—say, boy gets girl—aren’t part of our realistic heuristic. “What we believe is probable of a movie qua movie is radically different from what we believe to be probable in a movie conceived as a credible fictional world.” Movie lore tells us that boy will get girl, but to grasp and respond to the story emotionally, we have to feel in doubt. (Perhaps this is what people mean when they say that a mistake in the movie, or a distraction in the auditorium, takes them “out of the movie.” We’ve left the fiction.)

Similarly, movie lore connects the Ringo Kid of Stagecoach to Rooster Cogburn of True Grit (the original) because John Wayne portrays both. Yet the characters live in different, sealed-off story worlds. Ringo and Rooster have no knowledge of each other. Barring transmigration of souls, how can their connection be part of our experience of either movie as a consistent fiction?

Similarly, movie lore connects the Ringo Kid of Stagecoach to Rooster Cogburn of True Grit (the original) because John Wayne portrays both. Yet the characters live in different, sealed-off story worlds. Ringo and Rooster have no knowledge of each other. Barring transmigration of souls, how can their connection be part of our experience of either movie as a consistent fiction?

Carroll comes up with an ingenious explanation. Movies summon up star personas in the manner of allusions. Just as our experience is enhanced when we see a movie refer to another movie—Carroll’s example is a citation of Rocky in In Her Shoes—so do our mind and emotions respond to the presence of the star, as either a continuing allusion throughout the film or a one-off one, as with a cameo or walk-on. As he often does, Noël points out that practicing filmmakers use the concepts he elucidates. “Allusive casting” became part of the 1970s trend of paying homage to old Hollywood, but even in the studio era it wasn’t unknown. Carroll points to The Bigamist (above left), in which somebody says another character looks like Edmund Gwenn. Of course said character is played by Edmund Gwenn.

I’ve shrunk down Carroll’s line of reasoning to give you the flavor of the way he thinks. His piecemeal approach to theory focuses not on loosely named topics but specific questions. For example:

What if anything justifies us talking about popular culture as all one thing?

How do fiction films engage us in the emotional lives of their characters? Hint: It’s not through identification.

What makes us laugh at Mr. Creosote, rather than be horrified or disgusted by his vomit-laced gluttony?

How does a tale of dread, such as Poe’s “The Black Cat,” differ from a horror story?

Why should we care about Tony Soprano, who barehanded commits “crimes of which I don’t even know the names”?

Are the feelings awakened by art akin to friendship?

What role do moral emotions, such as the sense of community, play in our response to characters?

As for the jokes, they’re not of the esoteric academic type but rather straight-out funny. Just one essay, on the vague/implausible (you pick) notion that modernity (traffic, window displays, lotsa flashing lights) changed the very faculty of human perception:

The human eye rarely fixates; saccadic eye movement is the norm. We did not suddenly become attention-switching flâneurs in the late nineteenth century; we have been natural-born flâneurs since way back when.

No amount ot cultural conditioning will succeed in making normal viewers worldwide literally see human faces as cross-sections of centipedes.

I’m sure he’d give any indie filmmaker the rights to make Natural Born Flâneurs.

Viewers and their habits

Natsukawa Shizue in Town of Hope (Ai no machi, 1928).

Carroll tries to figure out certain logical conditions on spectators’ experience in general. That’s one province of film theory. But he’s also sensitive to the constraints on those conditions, the ways that historical and institutional circumstances can shape how viewers watch movies. (That’s part of the star-as-allusion argument.) Other researchers, historians by trade but sensitive to theoretical implications, have tried reconstructing the activities of theatres, trade personnel, and audiences in particular times and places.

A good cross-section of approaches has just appeared from Karina Aveyard and Albert Moran. Their anthology Watching Films: New Perspectives on Movie-Going, Exhibition and Reception contains 22 chapters of empirical research spread across the Europe, New Zealand, Australia, and the U.S. The researchers take us to particular cities and towns (Antwerp, Nottingham, and the Scottish Highlands) and to various points in history, from the 1920s to the present, passing en route the arrival of TV and the effects of the VHS revolution. There are also considerations of early reception theorists like Barbara Deming, along with studies of fan activities in Italy and elsewhere. Altogether, you couldn’t ask for a more enticing sampler of contemporary strategies for studying how audiences interact with cinema. Multiplicity long preceded the multiplex.

A good cross-section of approaches has just appeared from Karina Aveyard and Albert Moran. Their anthology Watching Films: New Perspectives on Movie-Going, Exhibition and Reception contains 22 chapters of empirical research spread across the Europe, New Zealand, Australia, and the U.S. The researchers take us to particular cities and towns (Antwerp, Nottingham, and the Scottish Highlands) and to various points in history, from the 1920s to the present, passing en route the arrival of TV and the effects of the VHS revolution. There are also considerations of early reception theorists like Barbara Deming, along with studies of fan activities in Italy and elsewhere. Altogether, you couldn’t ask for a more enticing sampler of contemporary strategies for studying how audiences interact with cinema. Multiplicity long preceded the multiplex.

A similar approach, but focused with razor acuity on a single country and period, is Hideaki Fujiki’s Making Personas: Transnational Film Stardom in Modern Japan. This book is an expedition into a nearly sunken continent, Japanese film of the silent era. Frustratingly few films have been preserved from those years, but paper documents abound. Fujiki has made intense use of them to answer the question: What were the cultural causes and results of the early star system in Japan?

The answers are rich and detailed. The very first stars weren’t on the screen at all; they were the benshi who narrated the silent program. Hideaki goes on to trace the career of the paradigmatic male star, Onoe Matsunosuke, and to show how his main traits (virtuosity and stature as “great man”) were reinforced by a troupe-based business model. Later chapters focus more on female stars, with emphasis on the influence of American actresses like Clara Bow. The flapper figure shaped not only Japanese female performers but women in real life.

Fujiki traces in some detail how the “modern girl” or moga floating through Ginza owed a good deal to Hollywood movies. He makes good use of what films survive from this period, particularly The Cuckoo (Hototogisu, 1922) and Town of Love (Ai no machi, 1928). In-depth analysis of the star image Natsukawa Shizue, above, allows him to discuss fan culture and movies’ role in accelerating trends in fashion and advertising. In all, Making Personas is a fascinating consideration of stardom as both an industrial and social construction in one of the world’s most important national traditions.

Education and environment

Institutions of another sort feature in two impressive books from the prolific Mette Hjort. She has had the very good idea of assembling documentation about how film schools work. How do different schools, academies, and more informal agencies understand the craft of filmmaking? What ethical values and social commitments are brought to the classroom and enacted in the production process? What are the histories of film schools around the world?

The answers come in two packed anthologies, The Education of the Filmmaker in Africa, The Middle East, and the Americas, and The Education of the Filmmaker in Europe, Australia, and Asia. From these we learn of the creative practices put into action by institutions in Nigeria, Palestine, Denmark, the West Indies, China, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Sweden, Germany, Australia, Japan, and many other localities. We get a real sense of intercultural communication and its breakdowns. Rod Stoneman points out that Tinpis Run, Papua New Guinea’s first indigenous feature, demanded postproduction discussions when outsider viewers couldn’t distinguish the villages presented in the story.

Things happen in these places that would astonish students at UCLA and NYU. Hamid Naficy tells of taking his Qatar students to Tanzania, where they worked on research projects only after spending the morning doing clerical and custodial work in schools and hospitals. We learn of children’s filmmaking initiatives in Mexico City, programs for at-risk youths in Brazil’s City of God favela, and students making photo and sound montages in Calcutta. One purpose of Mette’s collections is to remind us that film training goes far beyond getting your MFA and a showreel on a maxed-out credit card.

Hjort’s initiative, while already stimulating, ought to be continued and enriched. People are starting to understand the importance of film festivals within film culture—as distribution mechanisms, publicity arms, and in a roundabout way feedback systems shaping production. (One essay, by Marijke de Valck, points out the move by festivals toward film training.) More generally, we need to understand film education at all levels as shaping film production and film audiences.

Hjort’s introduction emphasizes that institutional politics are always related to larger political and cultural concerns. Social implications of filmmaking are brought to the fore in another emerging area of research. As each day seems to signal a new ecological disaster, it’s timely that a critical school has emerged to track how films and TV represent our relation to nature and technology. Among the scholars working prolifically in this area are Robin L. Murray and Joseph K. Heumann.

Hjort’s introduction emphasizes that institutional politics are always related to larger political and cultural concerns. Social implications of filmmaking are brought to the fore in another emerging area of research. As each day seems to signal a new ecological disaster, it’s timely that a critical school has emerged to track how films and TV represent our relation to nature and technology. Among the scholars working prolifically in this area are Robin L. Murray and Joseph K. Heumann.

Their first book, Ecology and Popular Film: Cinema on the Edge argues that apart from films like An Inconvenient Truth, which wear their green politics on their sleeve, there’s a much bigger and broader tradition of films about humans and the environment, ranging from fictional films with explicit messages, like Happy Feet (2006), to films with unintentional ones, like The Fast and the Furious (2001).

As “second-wave” practitioners of eco-criticism, Murray and Heumann aren’t much concerned with cheerleading or finding villains. They want to explore how media representations of the environment have responded to various cultural pressures. Their two most recent books are good examples. That’s All Folks? (2009), building on their analysis of Lumber Jerks in their first book, concentrates on American animated features. They perform careful symptomatic readings while also providing industrial context, such as the tactics by which Lucas and Spielberg adapted to the growing dinosaur craze of the 1990s.

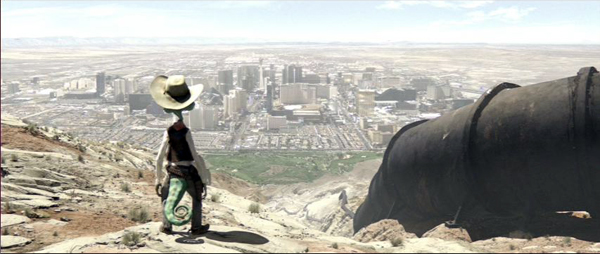

In Gunfight at the Eco-Corral (2012), Murray and Heumann tackle the Westerm on similar grounds, ranging from Shane and Sea of Grass to There Will Be Blood and Rango. Reading these chapters I was reminded how often the genre’s plots hinge on disputes over natural resources. Water, minerals, timber, grazing land, and what the authors call “transcontinental technologies” like the telegraph and the railroad are at the heart of classic Westerns, and the genre’s formulaic conflicts often have strong ecological resonance. This is the sort of criticism that refreshes your vision of movies you think know very well.

Their next book, Film and Everyday Eco-disasters is due out in June.

Things stick together

Lone Survivor (2013).

Finally, two more books merging theory and practice—but from opposite ends of the spectrum. One question that intrigues me involves coherence and cohesion in film. Roughly speaking, coherence involves the way the whole movie hangs together. If it’s a narrative film, how do the scenes or sequences fit into the larger plot? If it’s not narrative, what other principles organize the whole shebang? Cohesion involves how adjacent parts fit together—shot against shot, sequence to sequence. Both these concepts have practical implications, since every filmmaker confronts concrete choices about them in scripting, shooting, and editing.

Michael Wiese has contributed enormously to our understanding of filmmaking practice by publishing a series of books on cinema craft. The most recent one I know is by Jeffrey Michael Bays and it bears directly on cohesion. It’s called Between the Scenes: What Every Film Director, Writer, and Editor Should Know about Scene Transitions. Bays himself has written and directed films, written radio dramas (a great place to study transitions), and published books on filmmaking.

Between the Scenes is an entertaining and damn near exhaustive account of the ways that images and sounds can tie one scene to another. Bays considers aspects of space, like location or objects or actors; time; and visual graphics. The book also shows how sounds can bind scenes or emphasize sharp contrasts. In the example from Lone Survivor above, a soft whir of helicopter blades is heard over the first shot and grows louder when we move from the map to the landing area.

In a web essay called “The Hook” I explored some aspects of this process, but Bays goes into much more detail with many recent examples. He also raises ideas I never considered. For example, if we think of narratives as people traveling from one place to another (and most narratives are that, at least), then every filmmaker faces a choice: Show the journey or don’t show it. And if you show it, what parts and why and what does it tell us about the character? The larger point is: “Make sure you know where every character goes between every scene.” Thinking about this suggests ways to enrich your presentation, and it allows the characters—if only in your imagination—to inhabit a more fleshed-out world. Ideas like this can provoke everyone, filmmakers and film scholars alike.

Small-scale links between parts are considered more theoretically in Chiao-I Tseng’s Cohesion in Film: Tracking Film Elements. Trained in functionalist linguistics, Tseng brought her expertise to bear on film analysis. The results show a remarkable kinship between devices in language and certain cinematic transitions. Such linguistic functions as saliency (what stands out) and presumption (what can be taken for granted) are found in audiovisual texts too. For example, a shot taken over one character’s shoulder tends to lessen that character’s saliency and make another character, the one we see more clearly, more prominent.

Small-scale links between parts are considered more theoretically in Chiao-I Tseng’s Cohesion in Film: Tracking Film Elements. Trained in functionalist linguistics, Tseng brought her expertise to bear on film analysis. The results show a remarkable kinship between devices in language and certain cinematic transitions. Such linguistic functions as saliency (what stands out) and presumption (what can be taken for granted) are found in audiovisual texts too. For example, a shot taken over one character’s shoulder tends to lessen that character’s saliency and make another character, the one we see more clearly, more prominent.

This example is simple, but once Chiao-I gets going, she’s able to show how nearly every cut or camera movement can be seen as activating a unique tissue of cohesion devices. The words in a paragraph not only refer to ideas or things; they also link to other words in the paragraph and in the larger discourse. Similarly, in film, different aspects of the images and sounds stand out and adhere to one another instant by instant. Tseng’s analyses of passages in Memento, The Birds, The Third Man, and other films are accompanied by equally close studies of television commercials and educational documentaries. At the end, analysis is supplanted by synthesis, as she shows how the configurations she has pulled apart coalesce into levels that highlight characters and actions. It’s a fresh way to think about how we understand films within genres and stylistic traditions.

In effect, she’s showing the fine-grained patterns that emerge from the choices every filmmaker faces. It would be fascinating to sit in on a dialogue between Bays and Tseng, for they belong to the same community, or so I think anyhow. We’re all trying to understand aspects of cinema, and by focusing on certain phenomena rather closely, we have a good chance to understand them better.

So to the filmmaker who’s skeptical of theory, I say: We can’t think clearly without concepts, or talk clearly without terms. We need to develop rigorous ideas and arguments (i.e., theory) to understand film as best we can. But to the would-be theorist I say: Keep fastened on the look and feel of the films, and test your ideas and arguments not only against them, but against what you can find out about the craft of cinema, in all its historical implications.

I was pleasantly surprised, after I’d decided to talk about these books, to find work by Kristin and myself cited in some of them. Remaining coldly objective, however, I didn’t let these mentions diminish my praise.

Rango (Gore Verbinski, 2011).

Hitchcock again: 3.9 steps to s-u-s-p-e-n-s-e

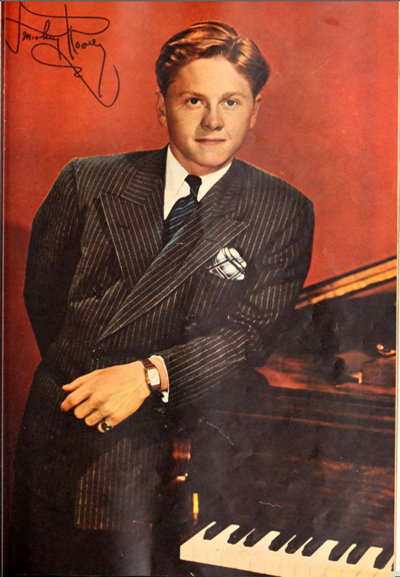

Henry Edwards; Alfred Hitchcock.

DB here:

My previous entry reminded you that Hitchcock was notorious for distinguishing between suspense and surprise. To achieve suspense, he maintained, the audience has to be aware of more than the characters know. Surprise arises when we know as much as the characters, or less. Hitchcock also declared his general preference for suspense, since it provides prolonged tension while surprise produces merely a momentary buzz. The mystery was: Where do this distinction and this preference come from? Are they original with Sir Alfred, or can we find precedents?

The story so far:

Step 1: The distinction itself goes back at least to the eighteenth century and the playwright/theorist Gotthold Ephriam Lessing. Lessing likewise expressed his preference for suspense because it demanded superior craftsmanship and yielded stronger effects on the audience.

Step 2: The distinction and the preference for suspense was still circulating in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century commentaries on theatre. My entry also mentioned a 1922 screen playwriting manual by Howard Dimick that took the same stance.

So we’ve located general conditions for influence. By the early 1920s, the suspense/surprise doublet was still circulating in the worlds of film and theatre, when Hitchcock was starting his career. But influence, like its source-word influenza, requires close contact. It would be good to find the secret agent who might have passed along the idea to the young director.

Step 3: My P.S. to the entry ropes in one candidate: Eliot Stannard. Richard Allen proposed him as a possibility, and Ian Macdonald supplied information that strengthened the suspicion. Stannard was a busy screenwriter of the period, who worked closely with Hitchcock on nearly all his silent pictures, and he even wrote a manual on screenwriting. Although he apparently didn’t talk about suspense and surprise in print, he would have known William Archer and other drama theorists who did. Stannard could well have initiated Hitchcock into the idea.

Step 3.9: But do we have the wrong man? After I posted my P. S., another foreign correspondent weighed in. Charles Barr writes:

A key figure here is Henry Edwards. Director in British cinema 1916-1937, and actor for much longer. His (lost) feature film Lily of the Alley in 1923 made a big point of avoiding intertitles. Whether or not he saw it, Hitchcock must have at least been aware of it, even though later he always said that The Last Laugh was the first such film. And already in 1920 Edwards had spelled out the surprise/suspense distinction: see attachment from the trade paper The Bioscope.

Edwards was indeed a major figure, as producer, actor, and director during the 1910s and 1920s. At the British Film Institute site, Geoff Brown and Briony Dixon provide a lively account of his career. He was clearly in a position to influence younger filmmakers.

The 1920 Bioscope article, cited in the Brown/Dixon overview and supplied to Charles by Ph.D. student Michaela Mikalauski, is a revelation. Edwards writes:

We must so construct our story that suspense is created–suspense is the dread that something may happen, and it is on this that we must build our story.

We must so construct it, that by careful preparation impeding difficulties or dangers are looming up before our characters. We must show the audience these dangers, and keep our characters ignorant of them until the proper moment; and it is the nearing of the danger to the blissfully ignorant character, making us long to cry out and warn him, that give suspense.

Tellingly, Edwards uses an example of an explosion. Imagine that our hero, wandering in the wilderness, has taken shelter in a shack. He sits on a box and lights a cigarette. While he has a leisurely smoke, his match has ignited some dry rubbish by the box. He rises and leaves the shed, just as the box is blown to pieces. Now we realize that it contained dynamite.

Here is a case in which there is expectancy, and never for a moment suspense, because the audience does not know of the impending danger to the character.

Now let us defy the critics who clamour for “surprise” in film construction, and tell the incident in the language of the screen.

Edwards goes on to imagine that we’ve seen quarrymen leave the box of dynamite behind. When the hero ambles in and settles down on the box for a smoke, we’re already apprehensive. Now every gesture he makes prolongs the tension, and we watch anxiously as the discarded match ignites scraps beside the box.

It becomes a question as to which will take the longer, the hero to recover his strength and go, or the box of dynamite to explode. Here is sheer suspense, and when there hero has gone it is no jar to the audience but rather a pleasurable expectancy to see the box explode harmlessly in the air.

After supplying another, more psychological example, Edwards concludes his piece: “The letters of the film alphabet are s-u-s-p-e-n-s-e.”

This article–published the very year that a young and innocent Hitchcock began work for Famous Players-Lasky in Islington–shows that the terms in which Hitchcock understood the suspense/ surprise distinction were already clearly articulated in English film culture. Even the bomb situation that Hitchcock would summon up for Truffaut is there in Edwards’ piece. But of course this information doesn’t sabotage the standing of Stannard, who may have read the Bioscope article and transmitted its lesson to Hitchcock in later years.

I confess I had thought I was done with the thing, but the last few days have brought a small frenzy of emails, and I’m feeling a bit of vertigo. Still, there seems not a shadow of a doubt that Hitchcock was maintaining his faith in a storytelling device that goes back quite far and still had a grip on the formative years of British and American cinema.

Thanks very much to Charles Barr for the information and for sending me the Edwards article. It was published as “The Language of Action,” Bioscope (1 July 1920), supplement p. iv. Thanks also to Michaela Mikalauski for locating the piece, and to Antti Alanen for forwarding some crucial email addresses.

Charles’ revised edition of his Vertigo monograph includes some further comments on the suspense/surprise distinction as it relates to that film. Charles is also completing a new book, with Alain Kerzoncuf, called Hitchcock: Lost and Found. It surveys the little-known films from all periods of Hitchcock’s career. “It devotes some 15,000 words to ‘Before the Pleasure Garden,’ discussing the 21 films Hitchcock was involved with (surviving in whole or part or not at all) and also a bit on the wider context, which is where Edwards comes in. This is all about to go to the publisher (Kentucky) and if all goes well will be out by the end of 2014.”

I’m grateful to all. The little adventure, which I suspect is not quite over, has been rich and strange.

Broken Threads (1918), produced and directed by Henry Edwards, who also starred.

Magic, this Lantern

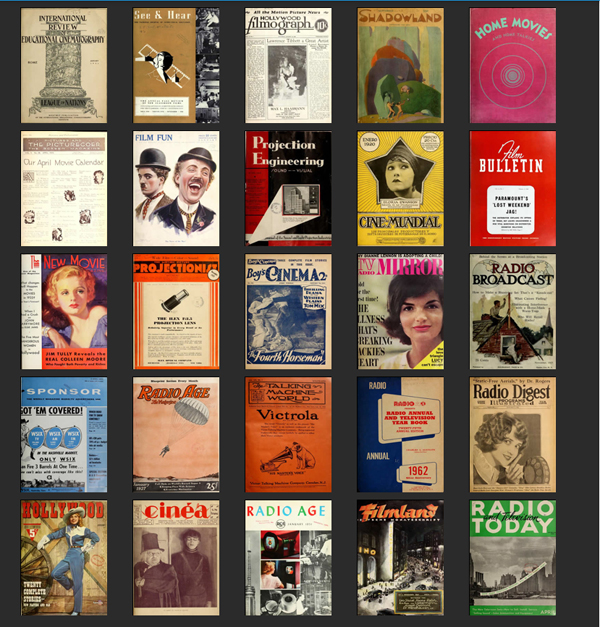

Home page of Lantern (top half).

DB here:

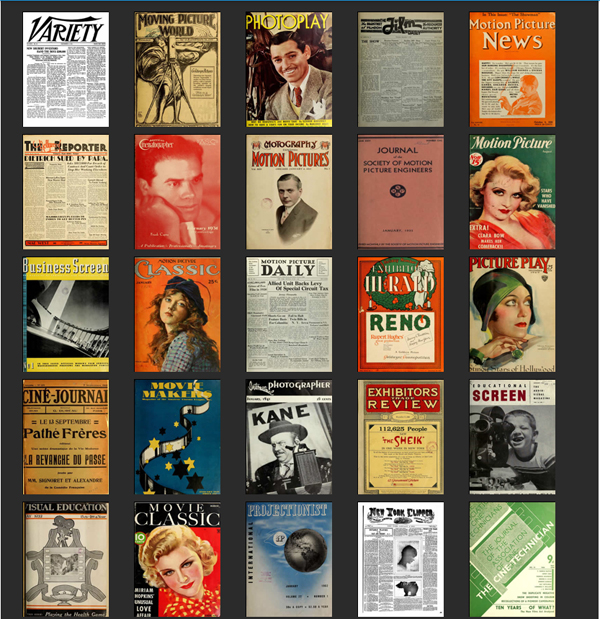

In earlier entries (here and here) we’ve reminded you of the immense and growing resource that is the Media History Digital Library. It was founded and is directed by David Pierce, world-renowned moving-image archivist, and it’s co-directed by UW-Madison Communication Arts professor Eric Hoyt. If you haven’t wandered, or rushed, or hop-skipped, through this wondrous library devoted to images and sounds, you owe it to yourself to start.

Of course it’s a remarkable resource for historians of film, television, and radio. It gathers a huge number of periodicals that can be searched, read, and downloaded–gratis. Thanks to its hookup with the Internet Archive, you can access and own entire books. The tireless Catherine Grant gives us Film Studies for Free. David and Eric give us Film History for Free.

But it isn’t just professional and amateur researchers who benefit. Anyone even mildly curious about media in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries should take the time to browse through the fan’s paradise that is Photoplay, the show-biz churn of Variety, the techie wonderland that is Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers and International Projectionist and many other publications. I guarantee you will be surprised and delighted by what you find: Big pages, beautifully displayed, that can hold you, we might say, spellbound; or at least make you girl crazy.

Why have you held back? Perhaps the sheer number of collections was daunting. And previously you had to search each journal separately, year by year.

Now Eric and his team, many here at UW, have made things even easier for historians and civilians alike. Today the MHDL crew have unveiled their new super-search engine, Lantern. Lantern allows you to search all of the MHDL publications at one go. Apart from the massive efficiency, you discover sources you wouldn’t have thought to check.

If you’re bold and type in Chaplin, for instance, you get 1446 hits. Many of them are from books, thanks to the generosity of Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum, Jeff Joseph, and many contributors to the Internet Archive. I struck minor gold with my first hit, a page from Charlie’s 1922 travel memoir My Visit:

Dear Mr. Chaplin: You are a leader in your line and I am a leader in mine. Your specialty is moving pictures and custard pies. My specialty is windmills. I know more about windmills than any man in the world. . . . You have only to furnish the money. I have the brains, and in a few years I will make you rich and famous.

A search for Gregg Toland brings you not only his much-reprinted 1941 American Cinematographer article, “Realism for Citizen Kane,” but also many AC articles featuring professional discussion of his contributions–not all of them complimentary. “Pan-focus…,” notes one, “may be a flash in the pan.” An anonymous review of The Little Foxes complains that in some shots “The eye hardly knows where to look.” But go beyond AC and you find lesser-known treasures: articles by Kane’s on-set still photographer, a different piece by Toland (opposite a full-page topless young lady), and 52 more. That’s just in 1941.

A search for Gregg Toland brings you not only his much-reprinted 1941 American Cinematographer article, “Realism for Citizen Kane,” but also many AC articles featuring professional discussion of his contributions–not all of them complimentary. “Pan-focus…,” notes one, “may be a flash in the pan.” An anonymous review of The Little Foxes complains that in some shots “The eye hardly knows where to look.” But go beyond AC and you find lesser-known treasures: articles by Kane’s on-set still photographer, a different piece by Toland (opposite a full-page topless young lady), and 52 more. That’s just in 1941.

Yes, while the default search digs for everything, you can limit your search by year and along other parameters.

Lest you think that this bounty is of interest only for followers of Hollywood, please note that the Global Cinema collection (1904-1957) includes books and periodicals from France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, Spain, and the United Kingdom. In 1921, for instance, Louis Delluc’s magazine Cinéa, while badmouthing Feuillade fairly constantly, gives unflagging support to L’Herbier’s El Dorado and adds in this sprightly caricature of Eve Francis.

Not all the collections are complete. There are of course copyright constraints on recent publications, and some journals are so rare that the runs must be filled in as copies are found. But the MHDL, like the universe, is constantly expanding, and possibly faster. Soon to be added are Quigley’s Exhibitors Herald, Cine-mundial, and more years of Variety. This spectacular enterprise is in the hands of people who are utter and dedicated completists.

I hate to pull a Grandpa Simpson, but when I think of all the time and money and gasoline and air tickets I ran through over several decades to visit libraries holding a few issues of this or that journal . . . and then think about the hours I spent paging through them looking for certain names, terms, film titles . . . and then think about how I painstakingly copied what I wanted onto 3 x 5 cards (photocopy not permitted) . . . I think–Well, what do you think I think?! I think how damn lucky you (and I) are to have all this material so accessible now. For work and play.

Same thing, come to think of it.

Thanks to Eric Hoyt for giving me a quick preview of Lantern, and to all my colleagues at UW-Madison who are supporting this remarkable undertaking. You can too: donations gratefully accepted.

P. S. 15 August 2013: Eric provides some helpful tips for using Lantern at the UW-Communication Arts blogsite Antenna.

Home page of Lantern (bottom half).

I’ll never tell: JASON reborn

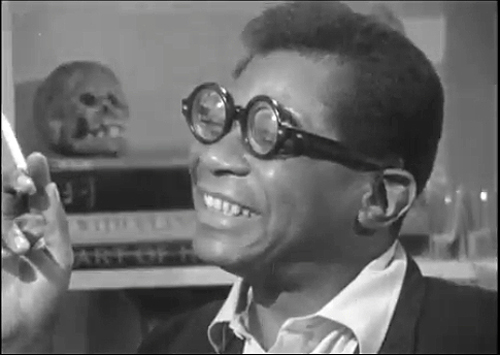

Portrait of Jason (1967).

DB here:

A white-walled apartment; no windows visible. Screen left: a day bed wedged into the corner. Center of screen: A fireplace and mantelpiece. Screen right: an easy chair with an end table boasting a lamp and ashtray. Behind it a bookcase. It’s as colorless a performance space as you could ask for, except perhaps for the skull on a bookshelf; but even that isn’t real.

In this arena a slender black man with thick Harold Lloyd glasses and a winning smile talks to us. His first words, delivered with calm sincerity, are immediately revealed as false.

My name is Jason Holliday. My name is Jason Holliday. (Breaks into laughter.)

(With a confiding smile) My name is Aaron Payne.

Over a single night, from 9 PM to 9 AM he talks to the camera, and eventually with the unseen filmmakers. High on marijuana and drunk on single malt scotch, he recounts his life as a gay hustler, recalls his family and childhood, and offers his analysis of how to behave around whites. He strikes attitudes, mimics the slaves in Gone with the Wind, and sings show tunes.

At first the filmmakers encourage him to tell this or that story, but late in the film one offscreen voice presses him. “Why’d you write letters about me?” “You should suffer.” “You’re full of shit.” Near the end Jason is sobbing. “If you don’t know,” he says, “I love you.” The offscreen voice is pitiless: “Stop that acting.”

Portrait of Jason (1967) is a legendary film that until recently had gone astray. Last Friday our Cinematheque hosted the US premiere of the restored version. The movie tells quite a story, but so too does Dennis Doros, VP of Milestone Films and the man whose tenacity brought back this delightful, disturbing record of Jason’s long night.

In and out of focus

It was a shocker in its day. What other film talked so frankly about gay life, race relations, and drug use? Where else would you hear virtually every four-letter word in the American vernacular? Shown in festivals and independent art houses, it won an astonishing level of praise. Here is Newsweek:

Jason lives, and Jason gives one of the most incredible performances ever recorded on film. This inverted Everyman, this anti-matter Jack Armstrong has a terrible tale to tell about how much it can hurt to be human, and he tells it in magnificently rich language with the gay desperation of an artist.

But the film was doubtless worrying. It circulated in the same year as Blow-Up, Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, Bike Boy, In Cold Blood, I am Curious (Yellow), Rush to Judgment, and I, a Woman—a year in which studio films, exploitation, art movies, and the underground seemed to be joyously blitzkrieging conventional values and good taste. Portrait of Jason opened at the New York Film Festival after a summer in which American cities had been shaken by riots in black neighborhoods. Now came a film in which a black man blithely reveals the cynicism behind his shuck-and-jive for rich white employers. And he’s a gay prostitute.

The director, Shirley Clarke, was a member of the New American Cinema group around the Film-Makers Coop and the magazine Film Culture, but she never fitted into any clear-cut category. She made dance films and some lyrical shorts like the zesty Bridges Go Round (1958), but she never joined the avant-garde tradition typified by Stan Brakhage, Michael Snow, and Ernie Gehr.

The director, Shirley Clarke, was a member of the New American Cinema group around the Film-Makers Coop and the magazine Film Culture, but she never fitted into any clear-cut category. She made dance films and some lyrical shorts like the zesty Bridges Go Round (1958), but she never joined the avant-garde tradition typified by Stan Brakhage, Michael Snow, and Ernie Gehr.

Her other feature-length films (The Cool World, The Connection) owed something to American cinéma vérité. Variety sourly remarked of Jason, “C’est la vérité,” and ran its review alongside a review of Frederick Wiseman’s Titicut Follies. But Clarke’s daughter Wendy recalls that although Shirley was friends with vérité filmmakers, she doubted that they could capture reality objectively. Leacock and Pennebaker would have found it impure to jab their own comments into the subject’s monologue the way Clarke and her lover Carl Lee do. Clarke’s approach is closer to that of the French cinéma direct, as pioneered by Jean Rouch and Chris Marker. In Le joli mai (1963) the filmmakers ask their interviewees frankly: “Are you happy?” This question underlies Portrait of Jason too.

Apart from the coaxing and goading interjections, Clarke’s filming method seems artless. There are fewer than fifty shots in 105 minutes, and they’re linked by black frames and out-of-focus passages. Both transitions mimic casual shooting. Yet Dennis Doros and Wendy Clarke pointed out that Clarke loved cutting. She was aware of the paradox:

I had enormous patience in terms of editing and I’ve always adored that part of making films, and in an odd way as I develop as a director I set up less and less situations to edit. The better I’ve become as a director, the less editing, the more I’m thinking in terms of the last twenty or thirty minutes that will have no editing at all.

In Jason the cutting isn’t as casual as it might seem. The blurry passages conceal edits, and the order of scenes doesn’t reflect the progress of the shoot. It will take patient research to determine the original chronological order of the reels we see. Clarke claimed that she enjoyed editing because at that phase she was really discovering her film.

Clarke’s apparently loose shooting, often running the camera until the magazine is empty, may seem a version of Warhol’s static films like Eat. It seems likely that she also learned from Warhol’s approach to performance. His psychodrama-based dramaturgy, as explained in J. J. Murphy’s fine book, constantly hovers between confession and put-on, and this is central to what happens in Clarke’s film. But Clarke gives her movie a more clear-cut narrative contour than Warhol would, with Jason’s monologue devolving from grinning self-assurance to stricken self-exposure.

Clarke and her crew acknowledge the act of filming, although they don’t emerge from behind the camera, as some do in The Connection. This recognition of artifice can encourage the subject to perform, to play up to the camera for the approval of the filmmakers and the audience. And a chance to perform is exactly what Jason wants. Now, he chortles, he can show off the nightclub act he’s been working on. The film is at once an audition and an effort to define himself. He’ll create “a picture I can save forever—one beautiful something that’s my own.”

So in the stage space between the day bed and the armchair, he strolls and poses. He fires off randy one-liners like “If I’d been a ranch, I’d be called Bar None.” Flipping his boa, he channels Mae West, Butterfly McQueen, Dorothy Dandridge, and Harry Belafonte. (Did he rename himself in honor of Judy Holliday?) He jiggles ice cubes in his glass with the winking panache of Dean Martin at the Sands. Clarke once said that in watching the rushes she was reminded of her choreography films: Jason seemed to be dancing.

To recover from his numbers, Jason flings himself offstage, flopping back on the daybed or sinking into the armchair as his cigarette burns down to the filter. In these moments, he seems to be candid. He admits that even with all the money he’s borrowed from friends, he’s not ready to take the show-business plunge. Drunk and giggling, he tells of childhood beatings with a razor strop: you mustn’t stick your butt up high but press yourself against the bed; that hurts less. His oscillations of mood are dislocating, passing from exuberance to frankness to self-mockery. Moments of self-celebration (“I’m a male bitch”) can also seem inadvertent glimpses of vulnerability–which may be exactly what Jason wants us to think. At one level Jason gives lessons in impression management.

I see his tears at the climax as born of authentic pain, but I can’t be sure. Earlier in the film he bragged: “When I do my pathetic bag, I’m really pathetic.” The layers of Jason’s one-queen show seem endless. Clarke said in an interview that everything he does on film—his jokes, stories, even the weeping—she had seen many times before. “His entire life is a role.” He seems to spill everything, but one of his mottos, delivered with finger snaps, is: “I’ll never tell.”

Treasure hunt

Wendy Clarke, Dennis Doros, and Maxine Fleckner Ducey.

How was this extraordinary film brought to light again? That was the story Dennis Doros told at our departmental colloquium the day before the screening. His company Milestone has specialized in reviving forgotten or neglected films of all types, including American independent work like Kent MacKenzie’s The Exiles and Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep. Simply trying to get a quality version of Portrait of Jason took him on a hunt that revealed, after many twists, that the closest thing to an original print was residing here in Madison, Wisconsin.

Back in the 1960s and early 1970s, our Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research made an effort to collect off-Hollywood cinema, including the works of East Coasters like Emile de Antonio, Doris Chase, and Shirley Clarke. Clarke’s collection, like several others, harbors vast amounts of personal papers and film material.

Clarke shot Jason on 16mm, but no negative has yet been found. There were 35mm prints made, and some wound up in archives, notably at the Museum of Modern Art. But among the material Clarke began giving the Center in 1973 were six reels of silent 16mm footage and several reels of sound recording. When they were inspected, the reels were believed to be either outtakes or stretches of a rough cut. We didn’t yet have a release print of Jason to compare them to.

Many years later, after searching high and low across the world, Dennis had the good idea of adding up the footage counts of our reels. The length was four minutes longer than the final running time of the film. After further research, our footage was revealed as Clarke’s original cut of summer 1967, which was trimmed and revised for the film’s official premiere at the New York Film Festival. This was, says Dennis, “the great irony in the search. Because Shirley Clarke had created a film that was meant to look unedited—filled with out-of-focus shots and black leader—Shirley’s 16mm fine-grain master was hidden all these years as outtakes!”

Our archivist Maxine Fleckner Ducey assisted Dennis throughout his quest. They found that the sound material, alas, was indeed outtakes, and Dennis still needed a good 35mm print of the Film Festival/release version for sound and final checking. More hunting ensued. Searching through the WCFTR collection, Dennis found an old telegram from Jacques Ledoux of Belgium asking permission to borrow a print from the Swedish Film Institute. Dennis contacted Jon Wengstrom at that archive, and soon he had a copy that could guide the restoration.

The whole process was enabled by funding from the Academy and from a Kickstarter campaign. To support that effort, Dennis and his wife and business partner Amy Heller made a video that traces their search for Jason. Their restored version had its world premiere at the Berlin Film Festival, and it will go on to other festivals and selected theatres. The image and sound quality far surpasses that of earlier versions in circulation.

A sort of epilogue came when Dennis and Wendy Clarke visited Madison last week. They dipped into Shirley’s vast collection, and in only two days they found treasures of a personal as well as professional nature. Perhaps some of their discoveries will surface as bonus materials on the eventual DVD release. Dennis and Wendy stayed on to introduce Friday’s premiere and take questions.

A charming pendant to Jason was the screening of a half-hour of Wendy’s Love Tapes series. In the 1970s Shirley shifted to making videos, and Wendy followed her path and became a major video artist. The series began as Wendy’s video diaries, but in 1977 she began recording people talking about what love means to them. Each person sat alone in a room, seeing her or his image on the monitor, and talked for three minutes. Over the years, the formats shifted from reel-to-reel tape to VHS to DVD, but the theme remained the same.

Wendy now has over 2500 tapes, shot in museums, schools, shopping malls, prisons, centers for battered women, and even in a booth at the World Trade Center. Ideally, she says, everyone on the planet should make one—a goal that isn’t so far-fetched thanks to smart phones and the Internet.

The Love Tapes assembly we saw with Jason was broadcast on PBS in 1982, and it was alternately grave and exhilarating. People celebrated love they’ve found but also mourned its passing and reflected on how it shaped their lives. Wendy has tried other themes, notably death, but love works best. “You talk about everything in it.” Sort of what happens in Jason too.

Thanks to Wendy Clarke and Dennis Doros for their visit to Madison, and to Jim Healy for facilitating it. Thanks also to Joe Lindner and Mike Pogorzelski, two graduates of our program, for enabling the Academy to take part in Milestone’s project. Maxine Fleckner Ducey was a great help on the Milestone project and, on a daily basis, makes us proud to have the WCFTR connected to our program. Thanks as well to current WCFTR director Vance Kepley for background information on the Clarke collection.

Project Shirley recently won Milestone an award from the National Society of Film Critics (the company’s sixth). Look for more Project Shirley material to surface from our holdings. And who, as Dennis asked in colloquium, will write the first book on this remarkable artist?

I drew Clarke’s comments about editing from Gretchen Berg, “An Interview with Shirley Clarke,” Film Culture 44 (Spring 1967), 55; and “A Conversation—Shirley Clarke and Storm de Hirsch,” Film Culture 46 (Autumn 1967), 47. The Newsweek review of Jason appeared in the issue of 6 November 1967, and the Variety review appeared on 25 October 1967.

The trailer for the new version of Jason is here; it includes side-by-side comparison of an archived 35mm print and the restoration. Clarke’s discussion of Jason’s role-playing is captured in an episode of the TV series Cinéastes de notre temps, by Noël Burch and André S. Labarthe. You can watch it here.

On The Connection, see J. Hoberman’s lively introduction on the New York Review of Books blog. Jason is a prototype of the portrait genre of documentary, a subject covered with care in Paul Arthur’s essay, “Identity and/as Moving Image,” Line of Sight: American Avant-Garde Film since 1965 (University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 24-44.

A sample of Wendy Clarke’s Love Tapes is here.

Love Tapes (1982).