Archive for the 'Festivals: Hong Kong' Category

Revisiting Planet Hong Kong

The East Is Red (1993).

DB here:

In about two weeks, we try something new here. It’s an experiment in self-publishing, like everything on this site, but this time we offer a new version of an oldish book.

Planet Hong Kong was published in 2000. It sold pretty well for an academic book, shifting about 7000 copies through 2007. It was translated into Chinese twice, once in Hong Kong and once on the mainland. It also got encouraging reviews; I’ve put up links at the end of this entry.

At some point in 2008, Harvard University Press took the book out of print, a decision I learned about accidentally in spring of 2009. The story is here.

Since then, the book has become rather scarce; only about twenty copies are currently offered on Amazon. Rather than letting the poor thing fade away, I considered revising it for the web. The more I thought about it, the better the prospect looked. I could add as much to the text as I wanted. The text could be corrected, updated, and supplemented in the future. I could add photos, lots of them, and they could be in color. The text would be searchable. And instead of waiting nine to thirteen months to see the result, I could see it in weeks.

Moreover, readers could use the book as they liked. If it was presented as a pdf download, they could read it on a computer or on several models of e-book readers. They could also print out all or part of it. Interestingly, when I asked students and faculty if they’d use the book, nearly all said they’d print it, or let a facility like Kinko’s do it. All in all, it looked like an experiment worth trying.

[Insert montage of fluttering calendar pages here]

God of Gamblers (1989).

Since July I’ve spent virtually all my time on the book, with a break to go to the unmissable Vancouver film fest. Reworking the manuscript, watching and rewatching films, and preparing new material kept me from writing other things I had planned. No blog for Godard’s eightieth birthday, aiming to defend Film Socialisme as an intelligible part of his career. No web entry on the remarkable films of Kon Satoshi, creator of Perfect Blue, Millennium Actress, and The Girl Who Leaped through Time. No discussion of the 1950s-1960s art-cinema canon in the light of Tino Balio’s fine new book on that period in U. S. film culture. No speculations on the psychological processes aroused by a movie’s opening scenes. Maybe next year.

Instead, apart from two quick entries provoked by Inception, I was absorbed in Hong Kong movies on film and DVD, notes from ten years of film festivals and conferences, and plenty of books and websites. Two blog entries, one on coincidence and the other on Jackie Chan’s Police Story, were chips from the workbench. As for my seeing recent releases, The Social Network and Megamind have been about it.

Now, after a month of fourteen-hour days, Planet Hong Kong redux is close to ready. I hope to make it available on this site during the week of 20 December.

The beast has grown in captivity. The first edition ran about 130,000 words; the new version adds 40,000 words. (In defense, I remind you of Adorno explaining why The Authoritarian Personality turned out so long: “We didn’t have enough time to make it short.”) There are over 150 new stills, all in color and many from 35mm prints. But no clips! These films are too beautiful to be reduced to those wretched mutants you get on YouTube. Besides, I don’t have the rights.

Planet Hong Kong 2.0 will not be free. My Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema and Kristin’s Exporting Entertainment are free online, but neither of those was revised, and we absorbed comparatively little of the costs of production. By contrast, the digital PHK is the fruit of a lot of paid labor. Heather Heckman and Mark Minett did excellent scanning and Photoshop tweaking, and Meg Hamel, our web tsarina, designed the book and is making it web-ready. I’m still reckoning the cost of the e-book, but it will be $20 or less. Payment will be rendered unto Caesar, aka Caesar Bordwell, via PayPal.

Here’s a sample page from our beta version. I’m still fiddling with the text, but the design looks to me like a nice compromise between the stability of a book page and the flow of a website. The file I’m using here is low-resolution, and this frame from it is a paltry 72 dpi jpeg, but the final pdf page should look very sharp. For curious boffins, the 35mm frame stills were scanned at 2000 dpi and reduced to 300 dpi for insertion. We don’t know yet how big the whole book’s file will be, but of course Meg will optimize it for downloading.

By the way: No, Wong Kar-wai did not invent the luscious image of the yearning woman.

Once the book is up, I plan to add a Hong Kong picture gallery to this site. It will include snapshots of celebs and fans from across the years 1995-2010.

ISNAQs (Infrequently, Sometimes Never, Asked Questions)

Enter the Dragon (1973).

PHK isn’t a comprehensive history of Hong Kong filmmaking; for that you must turn to Stephen Teo’s Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions. Nor is it a fan’s guide to the wild and crazy side of this local cinema. Stefan Hammond’s two books handle that task nicely, and there are many similar handbooks since. Most strikingly, the fanboys have been usurped by the professors. A geyser of academic books and articles about Hong Kong cinema burst in the new millennium, along with invaluable documentation from the Hong Kong Film Archive and the Hong Kong International Film Festival. My book doesn’t rival these.

What does this book do, then?

I try to design my books in layers, with different implications and possibly different readerships, at each level. The first and founding layer of Planet Hong Kong is my effort to convey the sheer pleasure offered by this filmmaking tradition. I write as an enthusiast for other enthusiasts, and for potential converts. In this respect, PHK is an academic dressup of a noble gonzo tradition. Hong Kong cinema has benefited from the gusto of admirers like Ross Chen, Lisa Morton, Stephen Cremin, Grady Hendrix, Stefan Hammond, Chuck Stephens, Richard Corliss, David Chute, Howard Hampton, and other lively writers. This cinema inspires dazzling, sometimes headbanging appreciations from critics.

Next there’s a historical layer. Hong Kong cinema is, I’m convinced, an important “national school” in world film history. It shaped global popular culture to a degree matched only by the westerns and gangster films turned out by the Hollywood studios. Every video game that includes martial arts, every American action movie, and every comic book showing a sword-wielding superhero owe a lot to Bruce Lee and the cinema he springs from. Less obviously, Hong Kong innovated approaches to film form and style that remain striking today. When I wrote the book, this artistic heritage was almost completely unappreciated, by both general audiences and specialized film scholars. The situation is a little better now, but the case always needs restating. Through close analyses of many films and sequences, the book tries to show the originality and force of the Hong Kong touch.

Another layer up, the book asks how popular cinema works. The clichéd split between “art” and “business” isn’t much help in understanding mass-entertainment film. The business relies on artistic traditions, and those traditions in turn are born from and shaped by industrial factors–not just constraints but also enabling opportunities. Hong Kong film provides a case study in how a mass-entertainment movie builds its effects on genre, star appeal, storytelling strategies, and stylistic tactics. It shows vividly how a media industry relies on conventions, and how artists tap those, stretch them, and sometimes twist them out of recognition. My interviews with several writers, directors, choreographers, and actors helped me understand the ways that creativity could be fostered by craft traditions.

At the most general level, PHK is a small-scale demo of an approach to asking questions about cinema. It shows how we might systematically study the principles of construction informing popular filmmmaking. Stealth poetics, in other words.

The old and the new

Leave Me Alone (2004).

The big changes in Asian cinema of the last decade make the original book something of a historical artifact itself. I did the research across the 1990s and wrote nearly all of it in 1998. Its emphases reflect issues circulating in fan and academic culture at that time. DVDs, introduced in 1997, had not become widespread, and VCDs were unwatchable. (Still are.) Most of the films that mattered had to be studied on film copies, although laserdiscs offered a passable backup in some cases. VHS tapes were seldom letterboxed, but laserdiscs often were.

The biggest constraint on the book was the scant availability of Shaw Brothers films on any format. Thanks to the Hong Kong International Film Festival, trips to archives, and the film collector’s market, I was able to see quite a few, but nothing like what’s available now in the massive and restored Shaw DVD library. Consequently, apart from the work of King Hu, Chang Cheh, and Lau Kar-leong, PHK doesn’t deal with the very interesting output of the territory’s most famous company. Fortunately, Shaws has been carefully studied in the years since my book, in a massive volume from the Hong Kong Film Archive and in Poshek Fu’s China Forever: The Shaw Brothers and Diasporic Cinema. For my part, this web essay and these blog entries try to make amends.

I could have recast PHK top to bottom, but I wasn’t convinced that I could come up something as pointed as the original. The text has been corrected, of course, and patches have been recast for greater clarity. It has also been enhanced by a few more examples, film sequences I referred to in passing but could not illustrate because I couldn’t find a print or couldn’t include color images. The chief updating is a series of sections added to the back end.

So here is what the book now looks like.

The first chapter broaches the general idea of an aesthetic of popular cinema. There follows an interlude comparing Hong Kong and Hollywood, focusing on The Untouchables and Gun Men. Instead of launching into a general history of local cinema, Chapter 2 sketches some general features of the territory’s film culture, concentrating on its audiences and its critics. The following interlude,”Two Dragons,” talks about Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, the two most famous Hong Kong heroes. Chapter 3 provides a condensed history of Hong Kong filmmaking up to 1997. The next chapter, “Once Upon a Time in the West,” traces how Hong Kong film attracted fans and festival prestige. There’s an interlude devoted to John Woo, then the fanboys’ demigod.

The first chapter broaches the general idea of an aesthetic of popular cinema. There follows an interlude comparing Hong Kong and Hollywood, focusing on The Untouchables and Gun Men. Instead of launching into a general history of local cinema, Chapter 2 sketches some general features of the territory’s film culture, concentrating on its audiences and its critics. The following interlude,”Two Dragons,” talks about Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, the two most famous Hong Kong heroes. Chapter 3 provides a condensed history of Hong Kong filmmaking up to 1997. The next chapter, “Once Upon a Time in the West,” traces how Hong Kong film attracted fans and festival prestige. There’s an interlude devoted to John Woo, then the fanboys’ demigod.

Chapter 5 surveys the industry, with emphasis on filmmakers’ craft traditions (how stories are planned, scenes are cut, and so on). The interlude that follows takes Tsui Hark as an instance of a director who creatively reworked such traditions. Chapters 6 and 7 go into the most detail about the aesthetics of Hong Kong film, surveying the dynamics of genre, the star system, visual style, and plot construction. Between these two chapters is sandwiched an interlude devoted to Wong Jing, the most disreputable major filmmaker in the territory. The longest chapter, the eighth, explores the distinctive aesthetic of action pictures, from martial arts to contemporary crime movies. The interlude that follows discusses three outstanding directors in the martial-arts tradition: Chang Cheh, Lau Kar-leung, and King Hu. The final chapter of the original book considers how the premises of popular cinema can be adapted to create “art films.” The principal, but not sole, example is the work of Wong Kar-wai. The original book concluded with an analysis of Chungking Express.

The new material in this edition starts with a chapter on changes in the film industry since 1997. That’s followed by an interlude focusing on the Infernal Affairs trilogy, which was as you know the source for The Departed. The next chapter considers how the artistic trends surveyed in the first edition have changed over the last ten years or so. While discussing developments in genre, storytelling, technology, and style, the chapter includes sections on Stephen Chow (particularly Shaolin Soccer and Kung-Fu Hustle), Wong Kar-wai (In the Mood for Love and 2046), and Johnnie To Kei-fung. The final interlude is a more in-depth discussion of To’s crime films and their relation to the indigenous action-movie tradition. At the very end is a new bibliography and endnote citations.

Readers not drawn to Hong Kong cinema might find my more general arguments of interest. For example, I suggest that Hong Kong shows us how important regional and diasporan networks are in creating and maintaining a film culture. To the claim that films reflect their societies, I reply that Hong Kong films suggest a different way to think about such a dynamic, using the model of cultural conversation. Readers interested in fandom should find something intriguing in the story of how cultists around the world helped establish Hong Kong film as a cool thing in the early 1990s. I also argue against the tendency in film studies to assume that when a film tradition doesn’t follow the rules of classical plot construction it must be based on something called “spectacle.” I suggest instead that we need to study principles of episodic plotting, which are probably quite common in popular art generally. In these and other areas, I wanted to use this cinema as a way into thinking about popular moviemaking as a whole.

After World War II, a tailor shop in Hong Kong put up a sign: “Reopening soon. Sooner if possible.” The same goes for me: Planet Hong Kong Redux is coming soon. Sooner if possible.

Here are some reviews of Planet Hong Kong by Richard Corliss in Time Asia (said I typed in my shorts with a beer at my elbow), Paul F. Duke in Variety (liked the book, worried that I talked like a Marxist), an anonymous writer in The Economist (said I’m a scholar who writes as a fan), Steve Erickson in Senses of Cinema (noticed my appreciation of stars), Mina Shin for Framework (developed my suggestions about festival culture), Leon Hunt in Scope (liked book, called me an empiricist, which tickles me down to my sense data), and Shelly Kraicer at chinesecinemas.org (as usual, more generous than he should be).

The most unexpected mention of the book seems to have vanished from the web. A New York critic who is surprisingly easy to outrage made an interesting attempt to charge me with synergistic marketing. He proposed, in the midst of a pan of Tsui Hark’s Time and Tide, that PHK was a covert attempt to promote Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, which had just won acclaim at Cannes. I wrote James Schamus, writer-producer of CTHD: “Now that we’ve been found out, we have to abandon our scheme to reprint my Dreyer book so as to coincide with Ang’s remake of Ordet.”

My quotation from Adorno may be apocryphal.

P.S. 13 December: Thanks to Daniel Erdman, I’ve now got the synergistic review mentioned above. It’s here. Thanks as well to Antti Alanen, who writes from Finland:

About ‘no time to be short’: quite possibly Adorno said so, and you are in good company:

Blaise Pascal: “Je n’ai fait celle-ci plus longue que parce que n’ai pas eu le loisir de la faire plus courte” (The Provincial Letters). J.W. von Goethe: »Da ich keine Zeit habe, dir einen kurzen Brief zu schreiben, schreibe ich dir einen langen« (letter to his sister Cornelia, but Goethe had apparently learned this from Cato and Cicero).

And soon after that came from Antti, Philippe Theophanidis wrote to point out the Pascal source as well. Once more I pay for the lack of a classical education!

Golden Scissors Part I (1963). Famous martial-arts choreographer and director Lau Kar-leung is on the far right. Source: Hong Kong Film Archive.

The Omnivoyeur’s dilemma

Otouto.

DB here:

Any major film festival is really many festivals. You meet someone who tells you about all the films they’ve been seeing, and the overlap with your dance card is virtually nil. You’ve both been in the same town, and probably hit the same venues, but you’ve been to different festivals.

Then there are certain syndromes. You convince yourself you need to see 3-5 films a day. Otherwise, what’s the point of traveling all this way? Soon you realize, horribly, that after a couple of days of this regimen, you can’t recall what you’ve seen. Some early afternoon, Festival Amnesia will set in, and you can’t remember what you saw that morning. Was it that ambitious but ultimately unsatisfying little romance from the Bosporus? Or the Chinese movie about moping teenagers trying to leave their dingy village? What were the names of those movies, anyhow?

My own symptoms are getting acute. Twice in recent years, I have found myself in front of a film suddenly realizing that I had seen it at another festival. I had forgotten the title. At least I caught my mistake with the first shots, but I expect that in time I will obliviously sit through the whole movie twice—probably liking it on the first pass and declaring it disappointing on the second.

Then there’s Viewer’s Remorse. Watching 3-5 titles a day, you inevitably encounter some stinkers. You take this philosophically until you meet someone else, who rhapsodizes about the string of masterpieces they’ve seen. Suddenly you realize that you have backed losers. Your friend has had a transformative festival experience, and you might as well have been flossing. Worse, your carefully picked mediocrities swell in your mind, blotting out the good films you managed to catch by dumb luck. Panicked, you thumb through the schedule to see if the great things you’ve missed are playing a second time.

They aren’t.

So film festivals aren’t by any means the sweet deal they may at first seem. Even putting aside queueing, officious door staff, racing between venues, and projection problems, there are plenty of features to make people like me more neurotic than we already are.

But I can’t complain about my latest visit to Hong Kong. True, breathing problems put me out of commission some days and eventually forced me to return home early. My biggest regrets were missing the Zanussi films and the two Angelopolous films, The Weeping Meadow and The Dust of Time. (Watch: Somebody will tell me they are all masterpieces.) Still, I managed to see a fair amount in two mini-festivals I carved out of Filmart and the festival proper.

Turning Japanese, yet again

Golden Slumber.

Parade, from director Isao Yukisada, is an ensemble picture about Tokyo twentysomethings sharing a flat. Their love affairs and marathon viewings of soap operas are disrupted when Satoru, a male prostitute, crashes there one night and winds up hanging around with them. With his blank passivity and ambisexual good looks he arouses their curiosity and, as usual in such movies, winds up changing everyone’s lives. The film was pretty good at portraying the way the kids keep life intriguing by conjuring up mysteries about their neighbors. (Is the man next door running a brothel?) The plot ran out of steam, I thought, but I enjoyed seeing a movie in that sober style that apparently only the Japanese can now pull off: only about 400 shots in nearly two hours, with an unassertive fixed camera that gave the characters room to breathe.

Also about a young cohort, but more action-driven, was Golden Slumber, by Nakamura Yoshihiro. He directed Fish Story (2008), a favorite of mine from last year’s festival. This one is about a hapless young man pulled into a plot to assassinate the prime minister. Threaded with glimpses of his college days, when he and his pals worked in a fireworks shop and became connoisseurs of fast food, the plot follows his efforts to avoid arrest and find how he was framed. Like a lot of contemporary Asian films, Golden Slumber sounds a note of nostalgia not only for long-lost innocence but also for kids’ self-consciously retro tastes in popular culture—in this case, the Beatles song “Golden Slumbers” (“Once there was a way to get back home . . . .”). Less zany than Fish Story, whose story pivoted around how an obscure album prepared for the end of the world, this seemed to me finally quite agreeable, thanks to its likably awkward hero and its lovelorn ending.

Longtime readers of this blog won’t be surprised that one favorite of my personal Japanese mini-fest was Yamada Yoji’s tear-jerker Otouto (aka Ototo, “Younger Brother”), a remake of a 1960 Ichikawa film. A widow who ekes out a living as a pharmacist is about to marry off her beautiful daughter. But during the wedding dinner her ne’er-do-well brother pops up and turns the ceremony into a catastrophe. Japanese movies are very good at evoking social embarrassment, and the disruption caused by Tetsuro makes you wriggle in your seat. He could have been simply a lovable loser, but he’s not that likable, let alone lovable, and his waywardness brings misfortunes on his sister’s family. In this movie about how you must love your relations no matter what, Yamada shows the classic resignation to family ties that has characterized the films from the Shochiku studio since the 1920s.

As usual with Yamada, the direction is crystalline in a way you hardly ever see now: calm framings, unhurried pacing, longish takes (about 12 seconds on average), and lighting and composition that etch every object in relief. When Ginko the mother peels an apple, the skin curls off in a long ribbon, and it’s as fascinating as a car chase in any other movie. In a film in which the camera seldom moves, a handheld shot regains some of its original power. Maybe I’m what Groucho called a sentimental old fluff, but like Kabei–Our Mother, Otouto shows that some cinematic traditions are still worth something.

For the real Shochiku flavor, experts will tell you, you need to return to the 1930s, and the festival did so with its small retrospective of Shimazu Yasujiro. A prolific director of comedies and dramas (he made over a hundred silent films), Shimazu built a reputation in the 1920s with family dramas like Father (1923). Most of his films are lost, and he died in 1945, so he didn’t benefit from the postwar revival of the industry and its growing renown in the West. His most famous work is probably the ingratiating Our Neighbor Mis Yae (1934), which features in the retrospective.

The remaining Shimazu films don’t seem to me to reveal the stylistic consistency we find in Ozu or Mizoguchi or Shimizu. There are flamboyant pictorial touches in First Steps Ashore (1932), a drama of sailors and prostitutes with stark lighting and cluttered sets influenced by The Docks of New York.

A fight scene is rendered in a long-lens shot that looks very modern, though the technique had already been seen in Japanese swordplay films.

Perhaps most original are the variants Shimazu works on a picturesque divider in a waterfront bar, which becomes a fascinating grid that sorts out faces.

Having been trained by this cheese-grater divider, we are given the tougher task of spotting the seaman peering from the distance at our stoker hero and the taxi dancer he rescues. (Not so easy to see in my still: He’s watching from the square and circle aligned horizontally behind the hero’s lips and chin.)

This “game of vision,” where we must strain to see action that’s blocked by bits of setting or furnishing, is characteristic of Japanese film then and since.

Okoto and Sasuke (1935) and Lights of Asakusa (1937), the two Shimazus I caught during my stay, aren’t as visually tricky as First Steps Ashore, but they display Shimazu’s characteristic interest in marginal characters (a blind woman in Okoto, stage performers in Asakusa). Both films close with a self-sacrificing retreat from the world. Later films, including the wonderful Brother and His Younger Sister (1939), would give this retreat a positive ideological spin. Disgusted by office politics, a young man takes his sister and mother to Manchuria to start anew, and the finale shows a clump of earth clinging to the plane wheels, as if a bit of Japan’s very soil would sanctify the empire’s new outpost.

Fei Mu, Film Poet

Nightmares in Spring Chamber.

A second mini-festival during my Hong Kong stay centered on Chinese film history. I’ve mentioned the Patrick Lung Kong titles in an earlier entry. The other prime figure was Fei Mu, celebrated as one of China’s best filmmakers. His Spring in a Small Town (1948) is often considered the greatest of all Chinese films, and it’s not an unreasonable judgment.

Unfortunately, only about half of Fei’s output survives. The earliest film we have is Song of China (aka Filial Piety, 1935), a paean to Confucian virtues. Parents permit their son to move to the city, but the son falls prey to self-indulgence and a temperamental wife. Even when he holds a banquet to honor his parents it is merely an excuse for what the father calls “revelry and gambling.” Soon the daughter is being seduced by a city slicker and told that “parental consent is a timeworn tradition.” This lesson in traditional morality is filmed quite fluently, with telling use of tracking shots, especially during the banquet, and sudden bursts of angular montage.

On Stage and Backstage (1937), from a Fei Mu script, is a 37-minute comedy. A troublesome diva refuses to come to a performance unless she’s paid, but the manager can’t afford it. So a street performer is brought in to substitute for the star in a performance of Farewell My Concubine. While the production is shot frontally and with little depth, director Zhou Yihua contrasts that area of action with the backstage milieu by means of layered compositions and lateral tracking shots through tangles of ropes and props. I enjoyed this charming film when I saw it during my first trip to Hong Kong, and its appeal held up well for me.

I came home too soon to catch Bloodshed on Wolf Mountain (1936), usually considered a strong work, and the little-seen Children of the World (1940). Other films in the series included The Show Must Go on (1952) from a Fei script and Romance in the Boudoir (1960), from Fei’s brother Louis; I already discussed the latter here. There were also two Chinese Opera films. A Wedding in the Dream (1948), China’s first color film, stars the legendary Mei Lanfang, the Peking Opera performer best known in the west who became friends with Chaplin and Eisenstein.

This image from Wedding in the Dream is a posed production still; the film itself, a straightforward record of Mei’s performance, survives in dreadfully worn condition. I found Murder in the Oratory (1937) more intriguing. A man is urged by his mother to murder his wife, the daughter of the man who killed his father. From the start, when an opera stage dissolves into a fully three-dimensional space, you realize that this will be an experiment in creating something halfway between canned theatre and a “filmic” treatment. So we get all the trappings of an opera performance, including stylized movement and singing, but with the camera weaving among the characters and furnishings, finding unusual angles, and even assuming characters’ optical viewpoints.

Far different is another title I enjoyed on my first visit to Hong Kong in 1995. Nightmares in Spring Chamber (1937) is an episode in the portmanteau film Lianhua Symphony. This 13-minute allegory of Japan’s imperial ambitions shows a maniacal frock-coated Japanese pursuing innocent Chinese girls through a vast bare villa. He cackles over a spinning globe and captures one girl, but she’s rescued by the other, a surrogate for the Chinese soldier we glimpse occasionally. Full of canted angles, hallucinatory visions, under lighting, looming shadows, and other trappings of German Expressionism, and accompanied by snatches of Debussy and the Danse macabre, it’s a far cry from the other items in the series, and it suggests a director of considerable versatility.

Last year the Festival premiered the restoration of the rerelease of Fei’s 1940 Confucius, which I wrote about then. This year a second restoration inserted titles to cover the gaps and put some scrappy scenes into their proper order. In addition, a very informative book, Fei Mu’s Confucius, accompanied the screenings. The essays explicate the film from several angles, including its relation to Confucian doctrine, to classic poetry and painting, and to other Fei Mu works.

Thanks to retrospectives like this one, we can see how much Fei’s official masterwork owes to his earlier efforts. There are touches of lighting and staging in these films that are more subtly developed in Spring in a Small Town, and the stately pacing of Confucius is here put to more mundane subject matter. Still, nothing I saw matches the quiet erotic boldness of this milestone of world cinema, which anticipates so much of what we find in Antonioni and other postwar European filmmakers.

So much to see, and even less time than I’d planned: Film festivals somehow manage to leave you unsatisfied and yet feeling full. A nice dilemma to have.

Spring in a Small Town.

METROPOLIS unbound

Fritz Lang has created a lot of pretty pictures and has discovered the astonishing talent of Brigitte Helm. I cannot blame him for not being able to cut the quantity of ideas in individual scenes mercilessly enough (the water catastrophe, the duel), but instead repeatedly trying out new lighting and angles. This time the film’s qualities lie precisely in these efforts: and if the viewer knows how to make the best of something, he will derive pleasure from these images.

Rudolf Arnheim, review of Metropolis, 1927.

Along with La Roue and The Battleship Potemkin, Metropolis (1927) is one of the great sacred monsters of the cinema. Many versions circulate, and restorations never seem to stop. A beautifully restored, though incomplete, version was premiered in Berlin in 2001. This is the basis of the most authoritative DVD releases. By now, however, everybody has heard about the 2008 discovery of a significantly longer version in Argentina, a 16mm preservation copy drawn from a scratch-infested 35 nitrate original.

Since 2008 a team at the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung has been at work adding material from the Argentine version to the earlier one. Kristin and I have written earlier entries (here and here) tracing the progress of the restoration, and the team have produced a detailed website explaining their work. The result made its world premiere at the Berlin Film Festival earlier this year, and an exhaustive exhibition about the film has been running at the Deutsche Kinematek in Berlin.

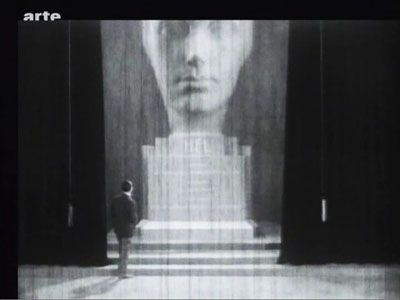

Now I’ve seen it, at a screening during the Hong Kong International Film Festival. Frank Strobel, a member of the restoration team, conducted the Hong Kong Sinfonietta, and another collaborator, Martin Koerber, curator at the Deutsche Kinematek, was present to discuss the restoration process. A handsome booklet, cosponsored by the Goethe-Institut of Hong Kong, provided a lot of background. The film was projected digitally, but at very high resolution and looking quite crisp. I had a front-row center seat. I had a swell time.

Metropolis has never been my favorite Lang of the period, but this version makes the strongest possible case for the film. It’s hard to dislike its shameless, preposterous ambitions, its stew of biblical and modern ingredients, its bold architectural vistas, and its trancelike characterizations. Also, people running crazily about in gargantuan spaces can usually hold your interest.

I just met a girl named Maria

All [the American editors] were trying to do was to bring out the real thought that was manifestly back of the production and which the Germans had simply “muffed.” I am willing to wager that “Metropolis” as it is seen at the Rialto now is nearer Fritz Lang’s idea than the version he himself released in Germany. . . . There was originally a very beautiful statue of a woman’s head, and on the base was her name–and that name was “Hel.” Now the German word for “hell” is “hoelle” so they were quite innocent of the fact that this name would create a guffaw in an English speaking audience. So it was necessary to cut this beautiful bit out of the picture . . . .

Randolph Bartlett, The New York Times, 13 March 1927

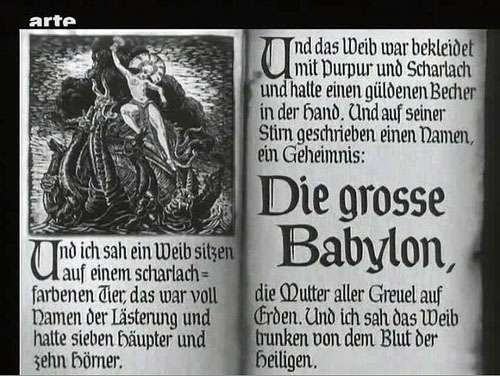

The new version gives the film a better narrative balance. Somewhat surprisingly, the plot hinges on one of the oldest and simplest narrative devices: mistaken identities. The overlord Fredersen engages the crazed scientist Rotwang to create a mechanical Maria who will lead the workers astray. Rotwang takes the occasion to avenge himself on Fredersen by having his robot urge the workers to destroy the machines. Two Marias, then–actually more, if you count the robot Maria’s incarnation as the Whore of Babylon in the Yoshiwara Club.

Thanks to the Argentine footage, we now know that another major character doubling involves Freder. At the start of the version we all know, Freder is visited by Maria and a flock of children. Upon seeing her radiant charity, he becomes suddenly convinced that he must join the oppressed workers, his “brothers and sisters.” Helping them has become his destiny. He gains an ally in Josaphat, an employee whom his father has brusquely fired. Descending to the cavernous machine halls, Freder switches identities with Georgy, a worker who returns aboveground to live Freder’s life. Freder wants him to go to Josaphat’s apartment, where they will meet. But the Thin Man, a long, leering hireling of Freder’s father, is charged with trailing Freder.

Stretches of the Thin Man subplot are missing from the previous version, but now we can see that Georgy/ Freder is a sort of early counterweight to the Maria/ Maria parallels. As in the latter case, the switch leads to misunderstanding, with the Thin Man following Georgy to the club and eventually to Josaphat. The Georgy substitution also allows Harbou and Lang to introduce the Yoshiwara Club early, but teasingly, in a rapidly dissolving montage. Only later will we get a good look at the delicious degeneracy inside.

As Martin Koerber indicated in several remarks, the older, most common version of Metropolis turns it into a science-fiction film, since it puts the robot Maria at the center of the plot. Just as important, though, is Freder’s plan for overturning class oppression, something fleshed out in the Georgy/ Josaphat material. Other new footage puts the relationship between Fredersen and Rotwang in a new light. We now see that Rotwang was in love with Fredersen’s wife Hel, and he has constructed not only a huge bust of her but also a “mechanical man,” outfitted with a distinctly female anatomy, as a sort of Hel substitute.

Fredersen diverts Rotwang’s plan to the purpose of mimicking Maria. So we get another doubling: Freder’s mother Hel becomes the firmware for the robot Maria through the machinations of two father figures. (Freder will kill one and redeem the other.) In all, the new footage yields a play of eerie Freudian substitutions.

The 2010 restoration also establishes the film as consisting of three large-scale movements. The first section, “Prelude” (Auftakt), runs a bit more than an hour. It shows Freder joining the workers and his father planning to have the Thin Man follow him. This part also introduces Rotwang, establishes Fredersen’s order to make a robot Maria, and ends with Rotwang’s capture of Maria. A second part, called “Intermezzo” and lasting about thirty minutes, is devoted to intertwining the Freder/ Josaphat plot with the creation of the robot Maria. The section more or less climaxes with a demo of the new Maria, dancing sexily at the Yoshiwara.

In “Furioso,” everything builds to a climax across a remarkable fifty minutes. The cloned Maria leads the workers to destroy the machines, fulfilling Rotwang’s plan to avenge himself on Fredersen, while the real Maria escapes from Rotwang’s compound during a fight between Rotwang and Fredersen. (We’re still lacking some of this footage.) At the same time, Freder and Josaphat converge on the underground city. The workers’ smashing of the machines triggers a flood from which the children must be saved. At the finale, during a hand-to-hand struggle with Freder, Rotwang falls to his death. There follows the famous epilogue in which Freder, “the Mediator,” must bring together hands (the foreman Grot) and head (the capitalist Fredersen).

Fluidity and freedom

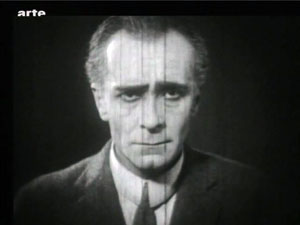

This delirious fable is rendered with unrelenting zest. Lang has now perfected his breathless version of silent-film narration. He relies on simple, immediately graspable compositions, rapid crosscutting among different plotlines, and a dynamic approach to analytical editing.

In the late 1920s, many American films became more heavily dependent on intertitles; it’s as if directors were anticipating talkies. But of Metropolis’s over 1800 shots, I counted only 26 expository titles and 156 dialogue titles—in a film running nearly 2 ½ hours. Lang plunges us into each scene with no fuss, and once we’re there, a smooth continuity carries us from shot to shot. Confronting the seven deadly sins in the cathedral, Freder turns away, twisting Georgy’s cap in his hands as he exits the frame.

Cut to the main area of the cathedral, and Freder is still twisting the cap as he enters the frame. (Like other shots from the Argentine version, this is slightly reduced because of the 16mm source.)

He lifts the cap, and we get his point of view on Georgy’s name and number.

Cut to the Yoshiwara nightclub closing, as Georgy steps groggily into the street.

Here the new footage lets us see that Lang is exploiting the sort of verbal and imagistic hooks he had developed in earlier films: from Georgy’s cap to Georgy himself, with no need of an intertitle to take us to the new scene.

Lang’s freedom of camera position is typical of late silent cinema, but he deploys his angles with characteristic precision. As usual in Europe, Hollywood-style continuity isn’t completely adhered to—there are some crossings of the 180-degree line—but Lang is careful to keep us oriented to the action through eyelines. This allows great flexibility in camera placement.

Fredersen is dictating to his secretaries while Josaphat is monitoring prices. A vast establishing shot shows all of them.

Fredersen’s pacing around his office allows Lang to introduce a new area around the window and the desk.

Now pacing in the center of the office, Fredersen pauses in his dictation and Freder bursts in behind him.

But Fredersen, who’s already holding up one hand as he speaks, simply twists his wrist, and this silences his son.

The shot approximates Freder’s point of view, but Lang gets a bonus from it. The sharp change of angle makes the imperious hand (and not, say, Fredersen’s expression) the compositional focus of the shot. In fact, this sort of hovering hand will become part of the characterization of Fredersen, and Lang will stress it through, once more, energetic changes of angle.

And still later, the framing will spotlight Freder’s pointing finger by pushing it to one zone on the far right of the shot.

Lang’s concise handling of such small actions forms a delicate counterbalance to the mass movements elsewhere in the film. Perhaps for him, both gestures and crowd scenes are merely two ways of creating a geometry that can activate every area of the screen.

The carefully controlled freedom of spatial construction is facilitated by one of Lang’s favorite tactics: shooting from directly on the axis of character interaction. (No, Wes Anderson didn’t invent this.) Lang in effect sets the camera between the two characters so that they stare out at us, as if mesmerized. The technique is most memorable in the scene in which Freder is confronted by Maria and the children.

Again, though, the Argentine material brings more instances to our attention.

Putting the camera on the axis allows Lang leeway in changing his angles. From a shot on the center line, you can cut to pretty much any other area of space.

Lang’s crisp visual narration comes to a climax in the well-named Furioso section. As the action ramps up, the characters rush from spot to spot, hurling themselves into the frame and then abruptly halting to hold the composition.

The extreme case is the robot Maria, whose head and limbs jerk puppetlike from one position to another.

In all, Lang’s precise, almost diagrammatic visual style rushes us through the film’s wild plot and dazzling architecture. An emblem of precision in the service of slightly demented material might be that memorable close-up of the robot Maria: One eye staring out normally, the other half-closed, and the mouth half-twisted in a leer, as if the circuitry in the skull was failing.

A little encyclopedia

Martin Kroeber, Togichi Akira, Winnie Fu, Sam Ho, and Wong Ain-ling discuss preservation and restoration at the Hong Kong Film Archive.

In a Q & A after the screening, Martin Koerber and Frank Strobel shared information about the version. They and their colleague Anke Wilkening could publish a whole book about the restoration, but here are some highlights, drawn as well from Martin’s comments at a lengthy seminar at the Hong Kong Film Archive.

*Sources for information about the premiere version include a copy of the script (helpfully marked with reel ends and calculations about running time), censorship cards recording the credits and intertitles reel by reel, Gottfried Huppertz’s musical score, and thousands of production stills.

*Using these materials, earlier researchers were able to create a sort of mosaic of the version that premiered in Berlin in January 1927. The resulting study film embedded long swathes of blank footage as place-holders. The fact that the Argentine shots fitted in neatly proved the validity of that edition. This study film may be ordered on DVD at nominal cost by educational and research institutions.

*What’s still missing? Some shots in the Argentine version may have been censored; we’re missing a bit in which Georgy, at liberty in a cab, sees a woman baring her body. Also lacking is nearly all the fight between Rotwang and Fredersen, which enables Maria’s escape. In addition, the Argentine print lacks a scene showing a monk preaching in the cathedral, which yields some apocalyptic images.

*If the film plays fast for contemporary tastes, don’t blame the restorers. This version runs at 24 frames per second. Actually, for the 1927 premiere the film was run even faster. The score includes passages accompanying missing footage as well as over a thousand synch-points for specific onscreen action. On the basis of this evidence, it seems that the film was designed to run at about 28 frames per second. This reminds us that silent-film running speeds were far from standardized, and they sometimes exceeded the 24 fps that would be established for sound film. (For more on this matter, go here and scroll down a bit.) In addition, Frank mentioned that in theatres with orchestras, the conductor could regulate the speed of the film with a dial set into the podium.

*Why insert the cropped 16mm footage in such obvious fashion? Couldn’t the framelines be adjusted to match the surrounding 35mm material? Yes, but this slight blowup of the footage would falsify the shot scale of the original footage and not match comparable shots in the 35mm footage. Moreover, Martin pointed out that because not all the scratches and fuzziness of the 16mm material could be purged, it’s better to let these stand stand out somewhat as evidence of the vagaries of film history–like leaving some damage visible in historic buildings.

*Why is the restoration in black and white, since most silent film restorations are in color? Lang was opposed to tinting and toning, so Metropolis premiered in black and white. This caused a debate among critics, some of whom considered it a promising departure from contemporary practices of coloring scenes. The tinted versions that one can occasionally see are likely export versions colored at the request of distributors in particular markets.

*Although future screenings of the 2010 version are to be accompanied by other ensembles devising their own music, there’s a powerful case for retaining Huppertz’s original score. It reflects the filmmakers’ intentions, and its Wagnerian romanticism and modern rhythms are enjoyable simply as music. Just as important, Huppertz designed his score around leitmotifs that, as in opera, can call to mind characters who aren’t onscreen at the moment.

*Metropolis, Martin argued, is too often considered simply a late Expressionist film or an early science-fiction effort. Now we can see that it’s much more: “a compendium of everything in the air in 1927 Germany.” It brings together political ideas, debates about class society and urban life, current trends in the fine arts, acting styles, and cinematic experiments. It owes a great deal to the “monumental” films of the late 1910s, such as Joe May’s Herrin der Welt (1919), but it’s also a synthesis of what filmmaking had become since then. “It’s a little encyclopedia of 1927 cinema. . . . There’s something in it for everybody.”

To see the restoration with the stirring score, vigorously conducted by Frank, was a high point of my Hong Kong trip and indeed of my filmgoing year.

This version of Metropolis was simulcast, if that’s the right word, on 12 February by Arte during the premiere at the Berlin International Film Festival. My frames are taken from that broadcast version; hence the bug. The restoration will be screened on Turner Classic Movies in the fall, and then released on DVD in the US by Kino International.

The epigraph quotation from Arnheim comes from Film Essays and Criticism, trans. Brenda Benthien (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997), 119. The article about the US cut of the film, which became widely seen around the world, is Randolph Bartlett, “German Film Revision Upheld as Needed Here,” New York Times (13 March 1927), X3.

Thanks to Martin Koerber for an abundance of information. For further reading, he recommends Erich Kettelhut’s memoirs on designing and filming the project, Der Schatten des Architekten (Munich: Belleville, 2009), ed. Werner Sudendorf, with many documents from sketches and photos; and the Deutschen Kinemathek exhibition catalogue, Fritz Langs Metropolis, ed. Franziska Latell and Werner Sudendorf (Munich: Belleville, 2010). You can get a sense of the tangled history of the versions of the film from Martin’s article in the latter volume, which includes a detailed account of the digital restoration. An earlier version of his piece, keyed to the 2001 version, is available as “Notes on the Proliferation of Metropolis,” in Preserve Then Show (Copenhagen: Danish Film Institute, 2002), 128-137. The Metropolis exhibition runs through 25 April.

A special thanks to Lee Tsiantis, Langian extraordinaire.

Hopscotching through history

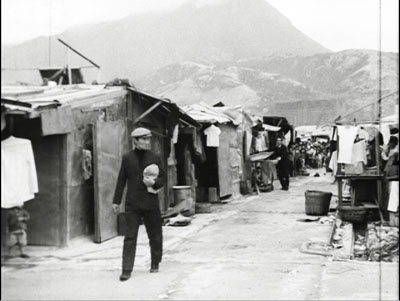

Temple Street, Hong Kong.

DB here:

Thanks to the Film Festival and screenings at the Film Archive, I’ve skipped gratefully through nearly a hundred years of local film history.

The Roast Duck legend, cooked at last?

First things, or rather first films, first. Last year local authorities declared 2009 to be the centenary of Hong Kong cinema. The long-standing claim (repeated in my Planet Hong Kong) was that To Steal a Roast Duck, aka The Trip of the Roast Duck, was made in 1909 and was the first locally produced fiction film. The controversy arose because the claim was based on later recollections of filmmakers. No fiction films from that era survived. We had no contemporary evidence that the Roast Duck was made in that year or that it was the first anything. Perhaps it wasn’t even made at all? In a blog entry last year, I summed up the arguments.

Now, thanks to the persistence of Frank Bren and Law Kar, we can come to more reliable conclusions. At a conference in December, scholars from around the world gathered at the Hong Kong Film Archive to discuss early Chinese cinema. One of the results was further revelations about the territory’s first film.

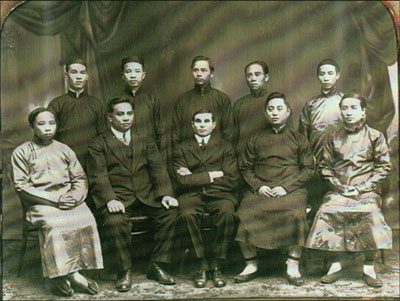

We know that at some point the Ukrainian-American entrepreneur Benjamin Brodsky came to Hong Kong and set up a film unit. (The picture above shows him surrounded by nine Chinese co-directors of the company he founded in November 1914.) An earlier Brodsky company made Roast Duck, among other films. But when?

At the conference Law Kar announced the discovery of a 1914 Moving Picture World interview with Roland Van Velzer, a photographer recruited from New York by Brodsky. During his stay in what he called “that queer land” of Hong Kong, Van Velzer shot four films in 1914.

We did a first native drama, entitled “The Defamation of Choung Chow.” With my experience and guidance the picture turned out well and when shown in public proved to be a wonderful drawing card. . . . The reason of its great popularity was because it was a Chinese piece entirely. . . . We made three other subjects during my stay there. These were: “The Haunted Pot,” The Sanpan Man’s Dream” and “The Trip of the Roast Duck,” the latter a rough “chase” picture. All of these pictures had phenomenal runs at the native theaters.

According to Van Velzer, then, the first film, made and shown in 1914, was what is now known as Chuang Tzi Tests His Wife. Roast Duck was evidently the fourth film made by the team that year.

Brodsky is significant not merely because he supported talent in producing the colony’s first fictional films. He also made long documentaries about China and Japan that played in the US. He seems to have been a colorful guy. In his barnstorming circus days, he once purged a lion with castor oil. Full details are here in an article by Bren and Kar. In the meantime, we can look forward to a more plausible centenary of Hong Kong film in 2014.

Social conscience, modern stylings

The Story of a Discharged Prisoner.

Hop ahead to the 1960s. Although the local language of Hong Kong is Cantonese, movies in Mandarin rule the market, with Shaw Brothers providing gaudily colored costume pictures, musicals, romantic dramas and comedies, and of course rather violent swordplay exercises. By contrast films made by Cantonese companies under tiny budgets look threadbare. Yet a few filmmakers tried to make Cantonese cinema more vigorous and innovative, and the most influential was Patrick Lung Kong.

Lung Kong was born in 1935, and by the time he was thirty he had performed in virtually every production role, from screenwriting and producing to publicity and distribution. Well-known as an actor since 1958, he graduated to directing in1966 with Prince of Broadcasters. His second film, The Story of a Discharged Prisoner (1967) was a landmark in local cinema, expressing sympathy for an ex-convict who tries to avoid being pulled back into crime. Lung Kong goes on to make many of the socially critical films of the period: Teddy Girls (1969), Hiroshima 28 (1974), and Mitra (1976). He ceased directing in 1981 but continued to work as an actor and distributor. He now lives in New York City, but he came back for the retrospective that the Film Archive has mounted.

I had seen some Lung Kong films in earlier visits to Hong Kong, but the retrospective will allow us to assess his career as a whole. Virtually none of his films are available on DVD, and none, as far as I know, with English subtitles. Particularly important, apart from the works I’ve mentioned, are his heavily censored film about a plague striking Hong Kong, Yesterday Today Tomorrow (1970) and the bitter domestic drama Pei Shih (1972).

When he started in the industry, he says, “I ran into these acquaintances who taunted me by saying how I was trying my hand at making Cantonese chaan pin [shabby films]. That was very insulting to the film profession in general…so I promised myself to go in and change things when the opportunity arose.” For him, change meant both modernizing Cantonese film technique and tackling social problems.

Lung Kong’s cinema, all agree, has a strong moralizing bent. He focuses on social problems—juvenile delinquency, nuclear war, prostitution, the exploitation of women in marriage. The films mix sensationalism, partly as audience bait, and social criticism. The Story of a Discharged Prisoner, reimagined by Tsui Hark and John Woo as A Better Tomorrow (1986), is at once a gangster tale and a harsh comment on the poverty that drives men to crime. Lung himself, armed with calisthenic eyebrows, plays the police officer hounding the protagonist. The Prince of Broadcasters begins as a pointed critique of popular culture, where schoolgirls fasten obsessively on a playboy radio personality. The film devolves into a more traditional thwarted-lovers plot when the protagonist reforms through his (mostly) chaste relationship with a wealthy girl.

Lung Kong’s cinema, all agree, has a strong moralizing bent. He focuses on social problems—juvenile delinquency, nuclear war, prostitution, the exploitation of women in marriage. The films mix sensationalism, partly as audience bait, and social criticism. The Story of a Discharged Prisoner, reimagined by Tsui Hark and John Woo as A Better Tomorrow (1986), is at once a gangster tale and a harsh comment on the poverty that drives men to crime. Lung himself, armed with calisthenic eyebrows, plays the police officer hounding the protagonist. The Prince of Broadcasters begins as a pointed critique of popular culture, where schoolgirls fasten obsessively on a playboy radio personality. The film devolves into a more traditional thwarted-lovers plot when the protagonist reforms through his (mostly) chaste relationship with a wealthy girl.

Lung’s film style is self-consciously 1960s modern, with zooms, calculated compositions, and handheld passages. He cuts fast, avoids dissolves, and offers fairly complex traveling shots. Looking at the cheap sets and listening to the awkward sound (including snippets of classical music and The Great Escape grabbed from LPs), one becomes aware of what a Cantonese director of the day was up against. So if the technique seems at times forced, you can at least admire Lung’s attempt to give his films a contemporary gloss.

The films were of crucial importance for local culture of the 1960s and have had continuing influence on younger directors. A very informative book of essays and interviews, produced to the usual handsome standards of the Film Archive, is in Chinese but includes a disk with a digital pdf of English translations. Two of the texts can be found here.

Jean Christophe in Macau

Another hop. I know nothing about Louis Fei, except that he was the brother of Fei Mu, whom I’ll be talking about in an upcoming entry. Romance in the Boudoir (1960) recasts the core situation of Fei Mu’s masterpiece Spring in a Small Town (1948). The situation, drawn from Romain Rolland’s novel Jean Christophe, is simple: A woman in a loveless marriage is visited by her former lover. In this version, her husband is a miserly doctor who wants the lover, Qin, to help him get a hospital post. Qin’s presence in the household rekindles the old romance and the couple hover on the edge of adultery.

Romance in the Boudoir is a bold piece of work. It opens with a prologue showing husband and wife trudging through Macau, utterly distant from each other. On the soundtrack we hear a woman singing about marriage as a prison. When Qin arrives, a parallel sequence traces him from the harbor to the household as a male vocalist sings of his weariness and broken heart. These melodic soliloquies will be evoked later in the film, when Qin and Suxuan stretch out by the fireplace and start to sing as the camera circles them.

Louis Fei makes maximal use of the house set, letting the vast staircase dominate the action on both floors. Repeated setups from the top of the stairs show the bannister cutting diagonally into the frame, pointing like an arrow to the climactic moment at the front door in the distance. Over everything hovers erotic tension, lasting several minutes during one scene when the former lovers tentatively touch one another before recoiling and then drawing toward one another again. If the doctor is somewhat caricatural, the portrayals of the wife and lover show a great subtlety, and the use of props, notably a glass of milk, is nicely modulated. This film shows how comparative large budgets enabled the Mandarin-language companies to make films of a high production standard, both in script and execution.

Dragons on fire

Now jump to 2010. Dante Lam is the hot new action director on the local scene, after the success of Beast Stalker (2008) and The Sniper (2009). Actually, like most overnight successes, he’s been at it awhile. He made an admirer of me with Jiang Hu: The Triad Zone (2000), which has one of the most graceful passages of graphic cutting (involving a red umbrella) that I’ve seen in recent Hong Kong film.

He’s back with the first big action film of the season, tagged with the barely adequate English title Fire of Conscience. The action scenes are better than the plot, which is better than the eternal impassivity of Leon Lai, a pictorial cipher in nearly every role he assumes. Still, you have to reckon with a film that includes not only a thrilling car chase, a truly scary gunfight in a restaurant, and grenades tossed around pretty casually but also a pregnant woman locked in a car slowly filling with carbon monoxide. The topper comes in the very last few shots, which provide as gruesome a flashback image as I’ve seen in quite some time and justifies the key line, “Save for revenge, what else is there?”

Visually, Fire of Conscience never surpasses the bravado of the black-and-white CGI opening, during which the camera coasts through a snapshot of action and lets clues float and scatter around the frozen characters. (It’s admittedly gimmicky, but more hypnotic than the comparable Watchmen opening.) Still, it’s exciting genre fare. What hath Ben Brodsky wrought?

Photo of Brodsky and colleagues by courtesy of Mr. Ronald Borden. The interview with R. F. Van Velzer was published in Hugh Hoffman, “Film Conditions in China,” Moving Picture World (25 July 1914), 577. Thanks to Frank Bren and Law Kar for this information, and to Tony Slide for calling attention to the article. The quotation from Lung Kong is from Clarence Tsui, “Scenes of the Crime,” South China Morning Post (22 March 2010), C1.

Patrick Lung Kong, with Sam Ho of the Hong Kong Film Archive.