Archive for the 'Directors: Kore-eda Hirokazu' Category

More VIFF vitality, fancy and plain

I Wish.

DB here:

Back from Vancouver Internatonal Film Festival, we’re still assimilating. We just learned of the winners, but here are some more movies that won my admiration.

Three lives, four-plus hours

Art cinema has been attracted to mystery and intrigue plots since at least The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Antonioni needed an enigmatic disappearance to get L’Avventura going. Before and after there were Cronaca di un amore, La Commare Secca, Blow-Up, La Guerre est finie, and the works of Robbe-Grillet. Not to mention Vagabond and Toto les héros and, venturing to Asia, Chungking Express and Fallen Angels.

True to this tradition, in Dreileben (Three Lives, 2011), conventions of festival cinema—elliptical transitions, ambiguous dream sequences, retrospectively identified point-of-view shots, anecdotal realism, de-dramatization, open endings—punctuate, and puncture, a killer-on-the-loose scenario. The genre is respected to the extent of supplying teasing clues, some conveniently recorded on video and in an old photograph. (Shades of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.)

The murder-mystery element is, I think, part of the reason that this TV installment-story has been making the festival rounds. Yes, there’s also its pedigree (three accomplished directors) and its use of the now-common strategy of network narrative. Each of the three episodes focuses on different characters whose paths cross. We get pieces of the whole story; scenes glimpsed in one episode are fleshed out in another.

The tryptych format recalls the Belgian Trilogy (Lucas Belvaux, 2002). But that exercise retold its story by centering on a core of characters, replaying events and switching point of view (and genre) from film to film. Dreileben’s first two episodes focus on characters at some remove from the crime and the criminal, a strategy that redefines what counts as the central situation. Moreover, and unlike most network narratives, these plots show few points of contact. Characters connect very rarely across episodes, so that each tale gains a weight of its own. The mad-killer element comes to seem secondary for quite a while.

The first episode, Beats Being Dead, directed by Christian Petzold, is largely organized around the perspective of Johannes, a young medical student about to embark on a prestigious fellowship. He becomes attached to a moody immigrant woman working in a nearby hotel. Over the romance hovers not only a brutish biker club but also a mental patient, accused of murdering a girl, who escapes from Johannes’ hospital and lurks around the forest. This episode is presented in a clean, almost enameled visual style sharpened by the abrupt scene shifts characteristic of modern cinema.

The second part, Don’t Follow Me Around (Dominik Graf), seemed to me the strongest. Johanna, a female police psychologist, is brought to the town, apparently to profile the criminal, but actually to conduct a rather different investigation. She stays with an old friend and her husband, and Johanna’s visit opens up a new psychodrama all its own. The rather narrow focus of the first, on a romantic triangle, here widens to consider frayed friendships, marital suspicions, and old passions. The character relationships get more complicated as things move along. The somewhat informal framings and jerky cutting (nearly three times as many shots as in the Petzold, in about the same running time) accentuate Johanna’s discomfort and her eventual moments of confronting her past.

After two films hovering around the fringes of the crime, the third installment, One Minute of Darkness, signed by Christoph Hochhausler, seems to go to the heart of things. Now we follow the escaped lunatic Molesch pursued by Markus, a cop so flagrantly unhealthy that he seems to risk a coronary every time he rises from his sagging armchair. Yet this detective story turns out to be not quite as cut-and-dried as we expect. That’s partly because of Molesch’s encounter with a little girl and partly because the first episode is revealed in retrospect to unfold in a more indeterminate time frame than we might have thought. The film doesn’t plug every gap, I think; I left thinking we needed a fourth or fifth installment. But that’s probably part of the point.

Genre conventions permeate all three episodes, which seriatim present twentysomething romance, simmering melodrama, and classic sleuthing and pursuit, all spiced by stalker-in-the-shadows atmospherics. Dennis Lim’s illuminating essay indicates that this trio of films is the product of a German debate about how filmmakers committed to “auteur cinema” can deal with matters of genre.

More broadly, works like Dreileben characterize much of today’s festival moviemaking: an effort to graft modernist narrative strategies onto a genre-driven plot premise. (We see it in The Skin I Live in too.) A cynic could argue that a serial-killer investigation serves to attract audiences who might be put off by purely formal gymnastics. But actually mystery plots, based on hiding information and misdirecting our attention, mesh well with the narrational maneuvers of international art cinema. If crossover films like this bring in more viewers, that’s a side benefit of merging two robust traditions—a storytelling mode that hides and then reveals secrets, and one that believes that even when revealed, secrets remain secretive.

POV = Perplexities of Vision

Headshot.

The barely-converging fates of Dreileben reminded me of the network knitting of Johnnie To’s Life without Principle. In a similar way, two exercises in optical point-of-view echoed the last sequence of Panahi’s This is Not a Film. In that non-film, the camera abandoned by a cameraman seems to be picked up by Panahi himself and carried beyond what we normally think of as “house arrest.” But one of the resources of the POV shot is that it can coax us to ask who’s seeing what we see. If we aren’t given an identifying shot of the looker, we can start to wonder. Played upon in countless horror movies to hint at the eyes of the stalking monster/ killer, the unspecified POV in Panahi’s hands (or perhaps not in his hands) becomes charged with political consequence.

Optical POV isn’t as fully exploited as you might expect in Pan-ek Ratanaruang’s Headshot. One of its premises is that Tul, a contract killer, is wounded in the cranium and as a result sees the world upside down. But the trauma takes place in the first few scenes, and what follows until the midpoint is a set of flashbacks explaining how he became a gun for hire. Present-time episodes showing him getting adjusted to his affliction alternate with past-tense scenes that supply him with motives for revenge.

So far, so noirish. Indeed, the iconography (crooked lawyers, not one but two femmes fatales, chiaroscuro scenes) and the plot (flashbacks, voice-overs, double- and triple-crosses) put us in familiar, quite enjoyable territory. Needless to say, like nearly all film noir heroes Tul has never seen a film noir, so he can’t sense the walls closing in as quickly as we can. He remains idealistic—“I may kill people, but I’m not a crook”—and trusting to a fault.

The upside-down POV works okay as a general pointer to the film’s Buddhist thematics, but the inverted shots are fairly few, introduced to defamiliarize a bit of action. They aren’t exploited as a thoroughgoing formal device. For a while vision scientists believed, mistakenly, that when people wore inverting spectacles, they eventually learned to see the world rightside up. Is Ratanaruang suggesting that Tul adapted in this way?Early in the film the hero pins pictures on his wall upside down, but near the film’s end I thought I saw a shot ostensibly through Tul’s eyes showing us the inverted pictures on the wall, rather than the way they’d look if he saw upside down. In real life, as if it were relevant, it seems that wearing inverted spectacles doesn’t make you see things right way round eventually. The world always looks flipped. But you can adapt to this upside-down array fairly quickly and execute normal activities like riding a bicycle and even reading. Presumably this explains why Tul’s marksmanship remains lethally good in the gunplay finale.

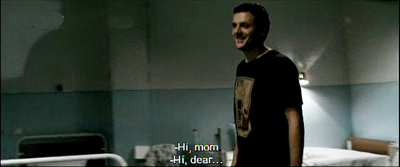

Far more consistent–obsessive, actually–is the play with optical POV in the Romanian film Best Intentions by Adrian Sitaru. When Alex’s mother has a stroke, he leaves Bucharest to visit her. She’s recovering reasonably well, but Alex becomes so anxious about her care that he makes life miserable for her, his father, his girlfriend Lia, and the doctor, an old family friend. After the first scene, when Alex gets the call about her stroke, a drastically totalizing POV system kicks in. Whenever Alex is in the presence of anyone else—major character, minor character, onlooker—we see him through that person’s eyes. If he’s alone, usually on the phone, the shots of him are unassigned and objective, but when he’s in public, he’s only shown subjectively. Moreover, we never get a POV shot from his perspective.

A narrational game emerges. When Alex is interacting with only one other person, we quickly grasp who the Unseen Seer is. For instance, we understand that he’s met at the train by his father, identified by his offscreen voice.

When Alex first visits his mother in the hospital, however, the POV floats momentarily. At first it might seem we’re seeing Alex’s entry through his mother’s eyes,when he briefly acknowledges the camera’s field of view.

But when he moves past, we realize we’re seeing him from the viewpoint of the woman in the bed beside his mother’s.

When he’s with only one other character, the scene plays out without cuts. When cuts come within a scene, they’re motivated as shifts from one character’s POV to another’s. Here we first see Alex and his mother through the eyes of the patient across the room, whom we glimpse in the background during his entrance above. When the mother’s neighbor looks at them, that motivates a closer view of them.

This tag-team POV becomes quite engaging when several characters are present. In a dazzling scene of three couples drinking around a tavern table, the dialogue is fast-moving and the cuts come quickly. I found myself trying to chart exactly whose view we’re getting. Sometimes the POV gets anchored retroactively: one of several characters we see in shot A becomes the POV vessel in shot B. For more fun, the system develops in unexpected ways as the movie proceeds.

The experiment is worthwhile, and not just as a formal game. Recall Erving Goffman’s notion that social life is a stage in which we enact the roles that put us in a good light. Best Intentions shows Alex as not only a caring son but a guy earnestly playing a caring son. In the Theatre of Everyday Life, he’s something of a drama queen. Of course he’s partly right to be concerned about the health-care system (he’s probably seen The Death of Mr. Lazarescu), but that concern also handily motivates his incessant performance of his part.

As a result of Sitaru’s rigorous formal constraints, Alex is onscreen for nearly every instant of this 101-minute movie. (The very brief exception is itself of interest.) His narcissism, his urge to control others, and his inability to really listen to his family and friends—all are perfectly captured by a stylistic strategy that constantly gives him center stage. I haven’t seen Sitaru’s previous film Hooked (2007), but that too used an enveloping POV strategy. Interestingly, there he assigned all three major characters optical POV shots. In Best Intentions, denying Alex his own POV underscores his fretful obliviousness to what anyone else thinks. He makes a scene in every scene, becoming an object of fascination and frustration, for others and for us.

Calming down

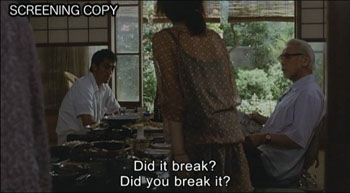

All these films, as well as others we’ve discussed in this year’s VIFF, might seem to support the idea that Form Is the New Content. It takes a film like Hirokazu Kore-eda’s I Wish to remind you of the power of less convoluted storytelling. Like Still Walking, it’s a family drama-comedy, but a little more somber and a little more comic. Devastatingly simple, too.

A family has split up. One brother, Koichi, stays with his mother and grandparents in Kagoshima, where the volcano splutters ashes into the air. The younger brother, toothily grinning Ryu, has gone off to Fukuoka with father, a scruffy rock guitarist. The boys communicate by phone, hoping to reunite the family.

They hatch a plan. They’ve convinced themselves that if they make a wish at the precise moment that two bullet trains pass one another, that wish will be granted. So Koichi and Ryu plan a pilgrimage that eventually encompasses their pals and that becomes a confrontation with the mundane realities of death and solitude, mitigated by comradeship and the hospitality of strangers.

The boys’ situation ripples outward to encompass the grandparents’ friends and the sons’ schoolmates and their parents, all of whom earn quietly incisive vignettes. Routines—classroom encounters, swimming sessions, Koichi’s run-ins with teachers, Ryu’s nights out with dad’s band—are recycled without fuss, building up a textured sense of each boy’s world. Kore-eda presents everything so unemphatically that he makes film direction look very easy.

Despite lacking the fanciness of the modern network narrative and its disjunctive time schemes and viewpoint switches, Kore-eda’s plot, like that of Ozu’s Early Summer, effortlessly creates a ramifying world in which our boys feel at once comfortable and apprehensive. Come to think of it, some of the kid comedy recalls the two brothers’ antics of I Was Born But, and the surprisingly sympathetic young teachers, reminiscent of the adults in Ohayo, become co-conspirators and, a little bit, surrogate parents. I Wish is a modest movie; it almost lowers its eyes in front of you. It’s also the closest thing to perfection that I saw in Vancouver.

For a lively roundup of ideas on Dreileben, see David Hudson’s Daily MUBI entry. An informative presskit is here. Headshot has been bought for US release by Kino Lorber. An informative interview with Adrian Sitaru is here. I discuss arthouse genre crossovers in an earlier year’s entry from VIFF. For a more thorough study of network narratives, see “Mutual Friends and Chronologies of Chance” in my Poetics of Cinema.

23 October 2011: Thanks to Christoph Huber for correcting an error in the initial post. Although there is a town called Dreileben, the film doesn’t take place there, as I had said.

I Wish.

Wantons and wontons

Oxhide II.

DB here, with more from the Vancouver film fest:

Two of the more innovative films I saw evoked film history—one explicitly, the other obliquely. Raya Martin’s Independencia is part of a planned series devoted to the history of the Philippines, told from the bottom up. In this first installment, villagers flee into the jungle to hide from the American “liberation” of their islands. The film centers on a mother and son who, joined by a woman the son finds, create a new family. After years, the son and the woman have a child, but their new life is threatened by the encroachment of the invaders.

What sets Independencia apart is Martin’s effort to create the look and feel of a 1930s fiction feature. He shot the movie wholly in a studio, and the evidently faked backdrops are counterbalanced by gorgeously controlled lighting effects, and even dashes of color. Since virtually no Filipino films survive from this period, Martin gives us less a pastiche than a possibility, a sort of hypothetical archival film. The fact that the film makes aggressive use of Dolby sound, especially during a tremendous storm sequence, only adds to the sense of history being reimagined for today.

More traditional, at first glance, is Puccini and the Girl, a historical drama by Paolo Benenuti and Paolo Baroni. Facts of the case: In 1909, a maid in Puccini’s Tuscan villa, accused of being his concubine, committed suicide. But an autopsy revealed that she was a virgin.

The film’s reconstruction of what happened behind the scenes, tracing the veins of jealousy and deceit running through the household, relies on recent research into the tragedy.

At the same time, we have an homage to silent cinema. In most scenes we hear no dialogue: actors whisper at a distance from us, or simply conduct themselves without speaking. What words we do hear are recited pro forma (the Mass) or sung (in a waterside tavern, or in nondiegetic accompaniment). There is only one line of conversation, and that is given greater saliency by being a cry from the heart.

So we’re largely confronted with a silent film, accompanied by music and sound effects. To add to the estranging effect, characters communicate chiefly through letters and telegrams—exactly as in the films of the period. We hear the letters’ text read aloud, but the sense of stately compositions propelled by written commentary, distinctive features of 1910s cinema, remains. An unwitting homage, perhaps, but one that pleased this fan of classic tableau cinema.

Independencia was part of the Dragons and Tigers thread, one of the hallmarks of the Vancouver event. Year after year it gives an unequaled view of current Asian cinema. This year’s program, assembled by Tony Rayns and Shelly Kraicer, was at least as fine as ever. Eight films compete for the $10,000 prize given to first or second features. The winning film, Eighteen by Jang Kun-jae, centered on the familiar situation of teenage lovers separated by parents and school pressures. I didn’t see all the competitors, but my own favorite was Chris Chong’s Karaoke, a Malaysian story of a young man coming to terms with his mother’s decision to sell her karaoke bar. The first ten minutes are quite creative, disorienting the audience through complicated sound mixing, while the boy’s community, devoted to the production of palm oil, is presented with a documentary directness.

Outside the competition, I saw several Asian films of consequence. I’ve already discussed Yang Heng’s Sun Spots and Bong Joon-ho’s Mother. Ho Yuhang’s At the End of Daybreak marks a shift from his lyrical first feature, Rain Dogs, which I reviewed at Vancouver in 2006. A plot situation close to that of Eighteen is treated in much darker tones. A young man falls in love with a high-school girl, but he’s driven to murder by her growing indifference to him. The familiar elements of furtive sex, drinking parties, and demands from the girl’s family for reparations are given a noirish treatent. Ho’s admiration for American crime novels shows in his increasingly bleak handling of the affair. Here the femme fatale is a high-school girl, and the entrapped male’s revenge is complicated by an unexpected erection.

Also under the influence of classic crime films was Yang Ik-June’s Breathless from Korea (right). It shows a brutal debt collector coming to terms with his childhood. Under a harsh surface realism, the film has the contours of the familiar redemption of a hard case, including the decision to reform that comes a tad too late. (Whenever a crook vows that this will be the last time he pulls a job, wait for the ironic retribution.) I thought that the character parallels (two scenes of murdered mothers) were somewhat too neat, but the director plays the anti-hero with conviction and deadpan humor, and Kim Kkobbi supplies an exhilarating turn as the tough high-school girl who becomes his companion.

Also under the influence of classic crime films was Yang Ik-June’s Breathless from Korea (right). It shows a brutal debt collector coming to terms with his childhood. Under a harsh surface realism, the film has the contours of the familiar redemption of a hard case, including the decision to reform that comes a tad too late. (Whenever a crook vows that this will be the last time he pulls a job, wait for the ironic retribution.) I thought that the character parallels (two scenes of murdered mothers) were somewhat too neat, but the director plays the anti-hero with conviction and deadpan humor, and Kim Kkobbi supplies an exhilarating turn as the tough high-school girl who becomes his companion.

Bong Joon-ho has been something of a leitmotif on this site lately, with my comments on Influenza and Mother. Under the rubric “Bong Joon-Ho & Co.,” Dragons and Tigers screened a collection of shorts paying tribute to the Korean Academy of Film Arts. Most were from the 2000s, but Kim Eui-suk’s Chang-soo Gets the Job, dated from 1984. Focusing on a gang of teenage purse snatchers, Kim’s film was a little rough technically, but it built its story deftly. The quality of the rest was quite strong, with the grisly and wacky Anatomy Class (2000, Zung So-yun) being a high point. Meanwhile, Bong’s Incoherence (1994) shows that his urge to deflate official hypocrisy, seen in Memories of Murder and The Host, was already present in his student days.

My admiration for Hirokazu Kore-eda runs high, as I indicated in my discussion of Still Walking at last year’s VIFF. But Air Doll, while full of vagrant pleasures, left me unsatisfied. The Kafkaesque premise, derived from a manga, is that an inflatable saucy-French-maid dolly comes to life, endowed with speech and movement but retaining her seams and air valve (both of which will figure in the plot). Her sad-sack owner doesn’t notice the transformation, but while he’s at work, she takes a job at a video store and wanders the city.

The aim, I think, is to defamiliarize ordinary city life by seeing it through Nazomi’s eyes. The fact that a sex effigy is the most innocent character in the movie is part of the point. Makeup, money, and fashion start to seem extensions of sad, solitary eroticism, and the line between mainstream movies and porn gets blurred. But all the thematic elements didn’t blend very well, and at moments, as during the music montages showing people’s desperate loneliness, I worried that for once Kore-eda had slipped into conventional sentimentality. The tone also shifts, with a climax that revises the big scene of In the Realm of the Senses. Kore-eda deserves credit for his unflagging effort to try something fresh with every project, but here, it seemed to me, that the film was defeated by an overcute conceit and underdeveloped execution.

The most exciting Asian film I saw at VIFF was Liu Jiayin’s Oxhide II. Her first feature, Oxhide, was screened at Vancouver in 2005. (Full disclosure: I was on the jury that awarded that film the D & T prize.) This one seemed to me even better.

To say that this 132-minute film is about a family making dumplings is accurate but misleading. To add that the action consumes only nine shots makes it sound like an arid exercise. In fact, it’s a consistently warm, engaging—I don’t hesitate to say entertaining—film that is also a demonstration of how a simple form, patiently pursued, can yield unpredictable rewards.

In the first Oxhide, we saw the comedy and tensions of Liu’s life with her parents, who run a leatherwork shop. By the time she shot part two, they had already lost their business, but the sequel presupposes that the shop is still going, albeit coming to a critical point. So there’s a quasi-documentary aspect, as the family’s financial strains, discussed cryptically at various points, hover over the mundane process of wonton cookery. Yet although everything looks spontaneous, it was all completely staged—written out in detail, rehearsed over months, reworked in test footage, and eventually played out in “real time.”

And in real space. The first shot, which consumes twenty minutes, shows Liu’s father pummeling a hide in his vise and eventually clearing the table for serious food preparation.

Actually, the film’s subject is that table. On its surface, a meal is prepared; around it, the family gathers; we even see what happens underneath. We watch father and mother chop scallions, mince pork, twist and yank dough, pinch the dumpling wrappers around the filling. We watch the daughter try to match her parents’ dexterity. This is a movie about housework as handiwork, and family routines and frictions.

For minutes on end, we see only hands and arms; Liu’s 2.35 frame often chops off faces. Liu employed a construction-paper mask to create the CinemaScope format within HD video. Why the wide frame? Most filmmakers use it for expansive spectacle, she remarks; but “I wanted to see less.” And the horizontal stretch further emphasizes the table.

As if this weren’t rigorous enough, Liu has filmed the table from a strictly patterned arc of camera positions, dividing the space into 45-degree segments. These unfold in a clockwise sequence around the table. What could seem an arbitrary structural gimmick is justified by the fact that each setup proves ideally suited to each stage of the process. When father and mother team up to start the meal, the angle gives us two centers of interest. And Liu feels free to “spoil” her mathematical structure by varying the height and angle of her camera. Plates, bowls, and an articulated lamp become massive outcroppings in this micro-landscape.

Oxhide II is unpretentiously inventive, quietly virtuosic. Evidently it took a Chinese filmmaker (whose day job is writing TV dramas) to blend domestic life with the rigor of Structural Film. Liu displays the fine-grained resources yielded by several cinema techniques, from framing and staging to lighting and sound. The finished dumplings get constantly rearranged on the cutting board. Each family member has a different technique for pulling off bits of dough, and each gesture yields its own distinctive snap.

I had to think, almost with pity, of all those US indie filmmakers who believe they have to cultivate CGI and slacker acting, to seduce investors and strain for outrageous sex and edgy violence. Liu made this no-budget, low-key masterpiece over years in a single room, and with her parents. That’s a new definition of cool.

Liu promises us another installment. In the meantime, every festival that’s serious about the art of cinema should pledge to show Oxhide II.

Puccini and the Girl.

PS 12 October: Thanks to Matthew Flanagan for correcting an embarrassing typo.

PS 15 October: Thanks to Ben Slater for correcting yet another one!

Vancouver wrapup (long-play version)

Our final post from this year’s Vancouver International Film Festival. Plenty to talk about, so today you get your money’s worth. Oh, wait….it’s free. So you definitely get your money’s worth.

Kristin here—

East

If Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf have been the most prestigious Iranian directors, with their features prominent at film festivals, Majid Majidi has been among the most popular. His Children of Heaven (1997) and The Color of Paradise (1999) both had international success, perhaps largely due to their focus on children and their sentimental, heartwarming stories. The Song of Sparrows (above, 2008) represents a pleasant development and is the best Majidi film I’ve seen. It’s still sentimental and heartwarming, but there’s also a great deal of humor and some highly imaginative situations that give the film more originality than the director’s earlier work.

For a start, the film puts children into supporting roles and sticks continuously with Karim, a hard-working father who strives to make extra money to replace his daughter’s hearing aid. Initially Karim works at an ostrich farm, a completely unexpected locale that generates considerable humor—until one ostrich escapes and Karim loses his job. His one asset is his motorcycle, which he turns into a cab in nearby Tehran, thereby earning good money. Meanwhile his mischievous son and his friends dream of dredging a covered pond near their village and making money by filling it with goldfish to sell.

The triumphs and obstacles that Karim and his son meet make up the bulk of the story, though the life of the tiny cluster of houses in which the main family and their neighbors dwell is charmingly depicted.

The plot of Under the Bombs involves a Lebanese divorcée returning from abroad to search for her sister  and son just after the 2006 war between Hezbollah and Israel. Only one taxi driver is willing to drive her into the southern region, where bombing could re-erupt at any time; he’s from that area himself, and he’s also attracted to Zeina. This simple story, however, is not half as compelling as the environment in which it takes place.

and son just after the 2006 war between Hezbollah and Israel. Only one taxi driver is willing to drive her into the southern region, where bombing could re-erupt at any time; he’s from that area himself, and he’s also attracted to Zeina. This simple story, however, is not half as compelling as the environment in which it takes place.

The film opens abruptly with extreme long shots of bombs going off among residential blocks, and as the two main characters travel through scenes of devastation, there is a vivid sense of the action being staged as the events depicted were actually unfolding. One scene depicts French NATO troops landing with the first relief supplies; another shows coffins being dug out of a mass grave and handed over to grieving family members.

Director Philippe Aractingi manages to convey something of the sense of outrage that news coverage of the Hurricane Katrina disaster did in the U.S. As Zeina questions shelter inhabitants about her lost relatives, they tell their tales of losing their entire families and of being separated from loved ones. We can’t tell whether these people may be actors or actual people who have suffered the losses they describe, but a cumulative sense of outrage emerges at the Israelis’ willingness to attack residential areas in their fight against terrorists.

West

Last time I wrote about films from Haiti and Jordan. The festival continued to offer films from countries that have had little or no regular production. El Camino (2007) hails from Costa Rica, though its director, Ishtar Yasin, is Chilean-Iraqi. The narrative is spare, though not in the enigmatic art-cinema fashion of Eat, for This Is My Body. We are introduced to 12-year-old Saslaya and her younger, mute brother Dario. They live with their grandfather in a shack and scavenge in the local dump. The grandfather sexually abuses Saslaya, and the children set out to find their mother. We watch their journey progress in typical picaresque fashion as they meet people, witness a puppet show put on by a vaguely sinister old man, and wander the streets of the local town. Yet we don’t learn where their mother is, why and when she left. The exposition is minimal, as is the dialogue. Watching El Camino, one becomes aware of how much talk most films contain, since the siblings don’t talk to each other or anyone else.

Finally, nearly 70 minutes into a 91-minute film, the children take a ferry. There the other passengers exchange stories about why they are traveling. Gradually we learn that the early part of the film was set in poverty-stricken Nicaragua, and these people are trying to enter Costa Rica illegally to find work. Saslaya reveals that her mother had left with that goal eight years earlier, after their father died. At last we get some sense of the situation, but the pair’s progress is interrupted once the group goes ashore and are shot at by local authorities. Losing Dario, Saslaya wanders into a town and perhaps an unhappy future—one that may echo what had happened to her mother.

This simple story is enhanced by poetic, even at times vaguely surrealist images, such as the two men struggling to move a wooden table who keep crossing the children’s path. With so little narrative to follow, we are encouraged to focus on the hardships and occasional pleasures of a culture which seldom figures in world cinema.

I referred to the two Mexican films that I described in our first Vancouver report as melodramas. Add another  to the list with Francisco Franco’s Burn the Bridges. Two teenagers care for their dying mother in a setting that seems to attract many Latin American filmmakers: a large, decaying mansion. The sister refuses to leave the house, determined to build an isolated world for herself and her brother, to whom she feels an incestuous attraction. He, however, wants nothing more to escape, especially when a tough new kid at school awakens his dawning homosexuality. The action seems a bit overblown at times; I wasn’t always sure whether apparent humor was deliberate or not. But the film and its settings are visually compelling, especially a scene in which the brother and his new friend sneak into a forbidden part of their Catholic school, passing a series of large religious paintings and finally emerging on the roof.

to the list with Francisco Franco’s Burn the Bridges. Two teenagers care for their dying mother in a setting that seems to attract many Latin American filmmakers: a large, decaying mansion. The sister refuses to leave the house, determined to build an isolated world for herself and her brother, to whom she feels an incestuous attraction. He, however, wants nothing more to escape, especially when a tough new kid at school awakens his dawning homosexuality. The action seems a bit overblown at times; I wasn’t always sure whether apparent humor was deliberate or not. But the film and its settings are visually compelling, especially a scene in which the brother and his new friend sneak into a forbidden part of their Catholic school, passing a series of large religious paintings and finally emerging on the roof.

O’Horten is a Norwegian film from Bent Hamer, who has emerged as a film festival favorite with his  previous Kitchen Stories (2003) and Factotum (2005). It’s a character study of a fastidious train engineer striving to cope with retirement; the film plays out in an episodic series of encounters that eventually lead to Horten’s acceptance of his new life. The comedy of eccentricity proceeds in leisurely, continually entertaining scenes. Apart from its mainly quiet tone and somewhat slow pace, it presents no art-cinema challenges to the audience. Norway has chosen it as its candidate for this year’s foreign-language Oscar, and Sony Classic Pictures has announced that it will release the film in the U.S. in early 2009.

previous Kitchen Stories (2003) and Factotum (2005). It’s a character study of a fastidious train engineer striving to cope with retirement; the film plays out in an episodic series of encounters that eventually lead to Horten’s acceptance of his new life. The comedy of eccentricity proceeds in leisurely, continually entertaining scenes. Apart from its mainly quiet tone and somewhat slow pace, it presents no art-cinema challenges to the audience. Norway has chosen it as its candidate for this year’s foreign-language Oscar, and Sony Classic Pictures has announced that it will release the film in the U.S. in early 2009.

Many critics have treated Terence Davies’ Of Time and the City as if it were a sort of elegiac cinematic salute to his native city of Liverpool. Despite the fact that, following the undeserved commercial failure of his excellent adaptation of The House of Mirth (2000), Davies has not made any films, he clearly retains his popularity among aficionados. In fact, however, there is plenty of criticism interspersed with the new film’s lyrical passages. Davies deplores what has become of Liverpool since his childhood there and doesn’t hesitate to assess blame, and he includes harsh comments on religion and on British royalty. He has said that he modeled his documentary on those of Humphrey Jennings, and in particular Listen to Britain (1942), though Jennings’ films had none of the bitterness on display here. Given, however, that Davies was bullied in his school, grew up gay in a more intolerant era, and has had a stunted filmmaking career, such bitterness is hardly surprising.

During Davies’s youth, brick row-houses encouraged communities among the working-class families  necessary to Liverpool’s industries. Using moving and still footage from the era set to classical music, the director manages to create a poignant sense of the grim conditions these people endured. Modern footage shows these old row-houses in ruins—yet shows the council apartment blocks that replaced them to be in almost equally ramshackle shape. Davies contrasts these with some of the few remaining glorious buildings of Liverpool, mainly columned government spaces through which he cranes his camera. He also filmed candid footage of children, perhaps hinting at the one hope for the future, perhaps displaying those whose youthful memories of Liverpool are now being formed in a far less attractive city.

necessary to Liverpool’s industries. Using moving and still footage from the era set to classical music, the director manages to create a poignant sense of the grim conditions these people endured. Modern footage shows these old row-houses in ruins—yet shows the council apartment blocks that replaced them to be in almost equally ramshackle shape. Davies contrasts these with some of the few remaining glorious buildings of Liverpool, mainly columned government spaces through which he cranes his camera. He also filmed candid footage of children, perhaps hinting at the one hope for the future, perhaps displaying those whose youthful memories of Liverpool are now being formed in a far less attractive city.

Of Time and the City marks a welcome comeback, one which I hope will lead to more films by Davies.

DB here:

A miscellany

The Dragons and Tigers programs continued to bring forth very impressive items. Jia Zhang-ke’s 24 City offered a meditation on newly industrializing China, in the vein of last year’s Useless. Aditya Assarat’s Wonderful Town was a prototypical “art movie” that handled a doomed love affair with sensitivity and suspense.

Especially engaging was the new offering from Brillante Mendoza, whose Slingshot I admired at Vancouver last year. In Serbis (“Service”), the Family film theatre lives up to its name only with respect to its management. For here, in the sweltering Philippines town of Angeles, the Pineda family screens porn. The movies attract mostly gay men, who service one another in the auditorium, the toilets, and the stairways. While the matriarch Nanay Flor fights a legal battle, she runs the lives of her employees and kinfolk in a milieu teetering on the edge of confusion. The Pinedas live in the theatre, so that the youngest boy must thread his way to school through a maze of transvestite hookers.

Mendoza confines the action almost entirely to the movie house. That premise recalls Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye Dragon Inn, but Serbis has none of that film’s nostalgia for classic cinema. Here movie exhibition is an extension of the sex trade, exuberant in its tawdriness, steeped in heat and sweat, prey to randy projectionists and stray goats. Almodovar might make something more elegant out of the situation, but Mendoza’s careening camera yanks us from vignette to vignette, from the complaints of the operatic Nanay Flor to her loafing husband to the lusty projectionist with a boil on his buttock. Crowded with vitality, the film can spare its last moments for a burst of reaction shots that imply a whole new layer of comic-melodramatic turpitude.

In other strands of the festival, I enjoyed Nik Sheehan’s lively documentary FlicKeR, which tells the tale of Brion Gyson, friend to the Beats and especially Burroughs. But the real star is Gyson’s Dream Machine. A turntable that spins a slotted cylinder around a lightbulb, the gadget—reminiscent of the Zootrope and other precinematic toys—proved mesmerizing to artists and countercultural fellow travelers. Marianne Faithful, Iggy Pop, and other worthies attest to the hypnotic power of the Machine, which triggered a drug-free high. Sheehan fills in a patch of important cultural history and may inspire others to tickle their alpha waves with a homemade Dreamer.

Almost exactly halfway through Steve McQueen’s Hunger lies a long dialogue scene in which IRA prisoner Bobby Sands explains to a priest why he has to launch a hunger strike. Over cigarettes the two men debate the cost of pushing tactics to this extreme. Running nearly twenty minutes and relying almost entirely on a protracted profile shot, it’s the first extended conversation in what is largely a film of bits of behavior and glimpses of a harrowing place.

Hunger starts by showing the morning routine of a guard at Maze Prison. He washes up. Stiff along a wall, he smokes a cigarette. He painstakingly folds up the tinfoil that wraps his lunch. McQueen’s oblique approach to the subject is maintained when we see a new prisoner brought in. Through him we learn of the cell walls whorled with excrement, the unannounced beatings, and the charade of providing tidy clothes for the prisoners to wear on visitors’ day.

Hunger starts by showing the morning routine of a guard at Maze Prison. He washes up. Stiff along a wall, he smokes a cigarette. He painstakingly folds up the tinfoil that wraps his lunch. McQueen’s oblique approach to the subject is maintained when we see a new prisoner brought in. Through him we learn of the cell walls whorled with excrement, the unannounced beatings, and the charade of providing tidy clothes for the prisoners to wear on visitors’ day.

Comparisons with Bresson’s A Man Escaped are inevitable. McQueen is less rigorous and original pictorially, assembling shots based on current image schemas (planimetric framings, selective focus, extreme close-ups, artily off-center compositions, handheld shots for scenes of violence). And he can underscore points a bit too much, as with the repeated shots of the guard’s scabbed knuckles. Still, compared with Schnabel’s conventionally daring Diving Bell and the Butterfly, the film is willing to be unusually hard on us. Through his nameless prisoners, McQueen treats both brutality and fortitude matter-of-factly. His experience with gallery-installation video seems to have encouraged him to let sheer duration do its job. A patient shot stationed at the end of the corridor waits while a guard, proceeding steadily toward us, clears puddles of urine with a push-broom.

Once Sands passes through his revolutionary catechism, the stakes are clear. The rest of the film returns to the dry, nearly dialogue-free atmosphere of the opening as Sands’ strike ravages his body. The objectivity of the opening yields to Sands’ hallucinatory recollections of his childhood as a long-distance runner. Some may see these images, including birds in flight, as clichéd sympathy-getters, but McQueen’s handling is pretty unsensational. Hunger’s quasi-geometrical structure, the sidelong introduction of horrific material, and the almost clinical treatment of Sands’ deterioration invite us to feel, but they also urge us to think about the price of sacrifice to a cause.

Genre crossovers

Some people consider the “festival movie” a genre in itself–the somber psychological drama with little external action, shot at a slow pace. The stereotype is all too often accurate, but festivals play genre pictures too. Usually these are impure genre pictures, more self-consciously artful or ambitious than multiplex crowd-pleasers. Vancouver had its share of such crossover items.

Hansel and Gretel, a South Korean horror film, played with a classic premise: the happenstance that brings someone from the normal world into a peculiar, isolated household. In this case, a superficial young man lost in a forest stumbles into the House of Happy Children. Here three kids seem to rule their passive, saccharine parents. The situation recalls Joe Dante’s episode of the Twilight Zone film, and during the Q & A director Yim Phil-sung acknowledged the influence of that movie, as well as Night of the Hunter. Brisk, fast-paced, and boasting remarkable sets—dazzlingly lit, jammed with toys and sweets, and ineradicably sinister—Hansel and Gretel could earn cult following in America. Rob Nelson has more here.

Artier, and scarier, was Let the Right One In, a Swedish film by Tomas Alfredson. Adapting Chekhov’s precept that the gun on the mantle in Act 1 has to go off in Act 3, the film begins with the boy Oskar playing with a knife at his window. Later we’ll learn that his stabbing is a fantasy rehearsal for dealing with the bullies who torment him at school. He meets Eli, a girl who comes out only at night, and their adolescent friendship/ love affair on the jungle gym of a housing block is intertwined with a series of vampire attacks on a small town. The tautly constructed script develops in gory directions that I found both unexpected and inevitable. The wintry widescreen cinematography is handsome and precise, and may well look better on 35mm than on the somewhat contrasty digital version available for the festival. It will have a limited opening in the U. S. later this month.

After School, by Uchida Kenji, is an agreeable thriller—somewhat overbusy and implausible in its plotting, but offered with a modesty and assurance that make it worth a watch. The basic situation, of a missing salaryman who may be having an affair, gains suspense by initially restricting our viewpoint to a shabby private detective. Uchida has fun with one of those misleading openings so common nowadays: you think you understand it from the get-go, but when it’s replayed it takes on a new meaning (and explains the title). The final shot, from a surveillance camera trained on an elevator, is a nicely oblique reminder of what seemed at the time a throwaway moment.

Variety characterizes Il Divo’s genre as “Biopic, Foreign, Political, Drama,” which covers all the bases. Giulio Andreotti, long-time Italian politico, is the subject of the movie, described by an ironic friend as “one-half of the current Italian film renaissance.” The movie surveys Andreotti’s career after the Red Brigades’ murder of Aldo Moro, which triggered a wave of investigations, tribunals, and assassinations, and it concentrates on years after 1995, when Andreotti was accused of links to the Mafia. The first half-hour feels like a single montage sequence, with murders and huddled meetings whisked past us thanks to rapid cutting, swooping camera movements, and pulsating music. (The eclectic score ranges from Sibelius to Gammelpop.) Imagine the sinuous opening of Magnolia, with machine guns.

Variety characterizes Il Divo’s genre as “Biopic, Foreign, Political, Drama,” which covers all the bases. Giulio Andreotti, long-time Italian politico, is the subject of the movie, described by an ironic friend as “one-half of the current Italian film renaissance.” The movie surveys Andreotti’s career after the Red Brigades’ murder of Aldo Moro, which triggered a wave of investigations, tribunals, and assassinations, and it concentrates on years after 1995, when Andreotti was accused of links to the Mafia. The first half-hour feels like a single montage sequence, with murders and huddled meetings whisked past us thanks to rapid cutting, swooping camera movements, and pulsating music. (The eclectic score ranges from Sibelius to Gammelpop.) Imagine the sinuous opening of Magnolia, with machine guns.

When director Paolo Sorrentino settles down to to presenting straightforward scenes, his florid technique persists (he never met a crane shot he didn’t like), but the action is dominated by Toni Servillo’s lead performance, which is weirdly showoffish in its own way. Servillo’s Andreotti is a rigid, buttoned-up fussbudget, an impassive mole of a man; only his epigrams (“Trees need manure to grow”) suggest a mind inside. The maniacally contained performance is as stylized as a turn by Lon Chaney, and as hard to keep your eyes off. Then again, given the glimpses of Andreotti in this report on the Italian response to Il Divo, the portrayal seems only a little exaggerated.

Of course there can be a straightforward genre picture here and there at the festival. The most disappointing instance I saw was The Girl at the Lake, an Italian whodunit that is only a notch or so above a TV movie. More entertaining was Welcome to the Sticks, the fish-out-of-water comedy that has become the top-grossing French film of recent years. A postal supervisor is assigned to a remote village where, he’s convinced, the hicks and the freezing cold will make him miserable. Instead he finds warm-hearted people and plenty of fun. The problem is to keep his wife from finding out how much he’s enjoying himself.

The item is hammered and planed to the Hollywood template. Plot lines: love affairs, both primary and secondary, complicated by work. Structure: four parts, with a neat epilogue that wraps everything up. Motifs: traffic cops, carillon bells, and food, often treated as running gags. Style: overall, less cutting than we might find in Hollywood (8.7 seconds average shot length), but still huge close-ups for extended passages of dialogue. In all, Wecome to the Sticks is sitcom fare that provided, I have to admit, a nice break from a lot of misery on display in the more orthodox festival offerings.

Turning Japanese

In our first communiqué, I talked about films by Kitano and Wakamatsu. I want to add comments on two more Japanese movies I saw, both of exceptional quality.

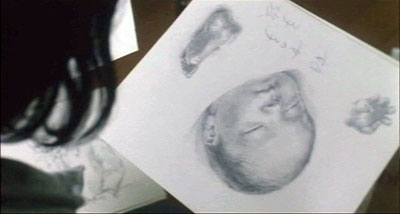

In All Around Us, Hashigushi Ryosuke (Like Grains of Sand, 1995) tells the story of a fraught marriage. The happy-go-lucky Kanao settles into a job as a courtroom artist for TV news, while Shozo, who works in publishing, is a believer in strict rules for their relationship. Their efforts to have a child end unhappily, and Shozo finds her life unraveling. Domestic troubles, amplified by tumult in Shozo’s extended family, play out while every day Kanao covers soul-destroying criminal cases, many involving assaults on children.

The mix of tender sentiments and extreme violence (offscreen, but evoked through chilling testimony) give the film a typically Japanese flavor. Hashigushi filters much of the courtroom horrors through Kanao’s point of view, so that while a defendant berates himself for not killing more people, Kanao watches a mother, and the close-up of her bandaged wrist concentrates all her grief.

The tact of Hashigushi’s handling is on display in a late sequence. As Shozo struggles out of her depression, her family gathers for what apparently will be her grandfather’s final moments. The adults assemble to discuss the situation while children play in a room behind them. Kanao shows them sketches that they take to be of the father in his final moments.

During their discussion, the adults are distracted by the children shattering an urn in the background.

Here Hashigushi uses staging techniques I’ve discussed in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. Kanao’s display of his sketch favors us; it is centered and frontal. Then, after blocking the children’s play for some time, Hashigushi reveals it—centered and exposed as the adults in the foreground turn to look.

Then most of the family leaves. Hashigushi tracks in slowly to the mother’s confession of her misdeeds, and he ends the shot with a close-up of Shoko.

In a film in which the camera moves seldom and without much fanfare, this creates a simple, powerful impact and refocuses the drama on the psychologically fragile Shoko.

The film I’ve admired most across the festival is, predictably, Still Walking by Kore-eda Hirokazu. It relies on a simple situation. Grandpa and grandma celebrate a son’s death anniversary by a visit from the families of their son and daughter. Across a little more than a day, memories resurface and old tensions are replayed.

Everything unfolds quietly, and the pace is steady: none of the histrionics, both dramaturgical and stylistic, of the Danish Celebration and other psychodramas of dysfunctional families. Still Walking is a classic Japanese “home drama” in the Ozu mold. The conflicts will be muffled and nothing is likely to break the placid surface.

In a stream of vignettes Kore-eda brings each family member to life, displaying an easy mastery in shifting attention from one to another. Gradually he assembles a group portrait of a domineering father, a good-humored mother, a slightly daffy daughter, a son always compared unfavorably to his elder brother, and in-laws striving to be well-received by the grandparents without alienating their spouses. The spirit of Ozu, particularly Tokyo Story and Early Summer, hovers over specifics: a dead brother is invoked, the family poses for a picture, and the patriarch, a retired doctor, has a clinic in his home.

Kore-eda doesn’t get as much credit as he deserves; he’s often overshadowed by extroverts like Miike Takeshi. That’s partly because his is an art of quietness, shown perhaps in its most extreme form in his first feature, Maborosi (1995). At the time I thought it was only one, albeit exquisitely wrought, version of the “Asian minimalism” that sprang up in Taiwan, Japan, China, and even a bit in Hong Kong. I suspect that this trend was largely due to Hou Hsiao-hsien’s masterpieces like Summer with Grandfather, Dust in the Wind, and City of Sadness. A Japanese critic told me that indeed Maborosi was criticized as being too Hou-like.

Now, after After Life, Distance, Nobody Knows, and Hana, Kore-eda has moved to the forefront of Japanese cinema. It seems to me that he maintains the classic shomin-geki tradition of showing the quiet joys and sadness of middle-class life while also plumbing the resources of “minimalist” mise-en-scene.

In Still Walking he works in an engaging, unfussy way. He lets us get to know and like his characters, feeling neither superior nor inferior to them. He builds up his plot more through motifs than dramatic action; a good example is the pop song that the mother loved and that gives the movie its title. The technique, spare but not austere, enforces the relaxed pacing. The film has only around 375 shots in its 111 minutes. While there are plenty of reaction shots and close-ups (the first shot shows women’s hands scraping radishes), some scenes play out in long takes rich in detail.

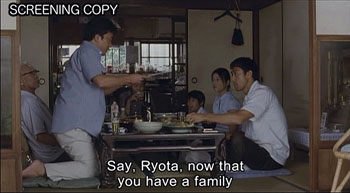

For example, in a three-minute shot early in the film, most of the family is gathered around a table.

The brother-in-law, a used-car salesman, goes out to the garden to play with the children.

Now the family members discuss the dead brother’s widow, who doesn’t come to family gatherings.

When the father declares that a widow with a child is harder to marry off, he is obtusely insulting his son Ryota’s new wife. Kore-eda marks the disruption with a cut to a reverse angle.

This generates another long take, in which Ryo’s wife Yukari deflates the tension by saying she was lucky to get him. The women then rise and clear the foreground, somewhat as the brother-in-law had by going into the garden. As the family talks, we can see him in the distance helping the kids break open a melon.

Ryo talks about his job restoring paintings. It’s clear that the father disapproves of it, wishing that Ryo, like the deceased brother, had taken up medicine. Kore-eda keeps the garden action as a secondary point of interest by having Ryo glance off occasionally.

But Ryo’s explanation of his job is cut off by the father’s abrupt rise and walk to the doorway, ordering the kids to stay away from one plant.

When the father returns to the table, the nearly two-minute long shot is replaced by a series of singles as Ryo tries to explain his work.

These shots employ one of Ozu’s staging tactics, settling two characters not directly opposite one another but one space apart. The camera seats us across from each one. As a result, the men can be posed frontally, while now we can watch where their glances go—most often, downward. The new setups let us see that the father and son don’t look at each other much.

Instead of moving to these singles right away, as most directors today would, Kore-eda has saved them as a way to articulate the next, more intense phase of the drama. It is arguably a less ostentatious way to raise the tension than the prolonged track inward that Hashigushi uses in All Around Us. (Then again, Hashigushi employs that technique at a climactic moment, while this scene we are still rather early in Kore-eda’s film.) The point is the simplicity and delicacy with which Kore-eda deploys traditional elements of craft.

It wouldn’t be fair to offer a more intensive analysis of this trim work, since it has yet to be widely seen. In the best of all worlds, it will get an American theatrical release.

In all, another wonderful Vancouver festival. See you there next year?

FlicKeR.

Mostly Asian, and why not?

David here:

A correspondent asks: Why am I spending so much time at the Vancouver Film Festival watching Asian movies?

Well, I have dabbled in other regions. Most recently, I enjoyed Eugène Greene’s short Signs, a metronome-and-protractor movie that nonetheless harbors a sharp sting of emotion. More straightforwardly entertaining was Aki Kaurismaki’s Lights in the Dusk. You’ve seen the story’s premise before, both in film noir (femme fatale dooms hero) and in other Kaurismaki films (loser comes stubbornly back for more trouble, and gets it). But it’s as usual filmed in a laconic, Bressonian way, and we get another Kaurismaki protagonist who is blank-faced, obstinate, more than a bit thick, and, despite everything, quixotic.

Still, Asian films have come first for me, as for many others here. Why? The evidence is clear: Since the 1980s, movies from Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, Mainland China, South Korea, and more recently Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines have offered an almost unrivaled range of accomplishment. (Want names? Tsui Hark, John Woo, Wong Kar-wai, Kitano Takeshi, Kore-eda Hirokazu, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Edward Yang, Jia Zhang-ke, and on and on.) The energy hasn’t flagged, and Vancouver has been in the forefront of supporting this tidal wave of talent. Tony Rayns’ brilliant programming has set an international standard, and the festival’s Dragons and Tigers competition for first features have brought many young filmmakers to world attention.

So herewith some more outstanding Asian revelations from my final Vancouver days:

Hana: Kore-eda keeps surprising us; each film is quite different from the one before. In a downtrodden neighborhood of Edo (the old name for Tokyo), people live in mud and dung, struggling to get by. Some of the loyal 47 ronin wait impatiently to avenge their executed lord, while a young man hangs around trying to find his father’s killer. But the fact that the youth is a fairly inept warrior tips you off to the essentially comic vision underlying this warm movie. Add in a bully who isn’t actually a bad guy and a gallery of low-life neighborhood types, who pass the time rehearsing a play that unwittingly satirizes the samurai ethos. The result is a film that probes the righteousness of vengeance with tact and vulgar humor. Everybody I know wanted to see this again, right away.

My Scary Girl (Korea): The Trouble with Harry meets The Forty-Year-Old Virgin. Dae-Woo has never had a date, but he decides to start with his cute neighbor. He doesn’t know that she’s a Woman with a Past, not to mention a fairly worrisome Present and an ominous Future. Romantic comedy shifts to black comedy, and bowling pins mix with lopped-off fingers. It’s a crowd-pleaser, and Hollywood will probably rush to remake it. But will an American director have the guts to keep the very logical but not wholly happy ending?

I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone: Taiwanese director Tsai Ming-liang has provocative ideas and burnished imagery, but sometimes I’ve thought he’s too clever by half. This movie, his first in his native Malaysia, won me over because it seems to play to all his strengths. Four people intersect around, under, and on a mattress, with an extra character as a kind of comatose sentinel. Tsai’s gorgeous imagery isn’t just pretty for its own sake. Like Tati, he can design compositions which are actually funny, and his long takes give us time to probe the textures and crannies of staircases, a building site, and ordinary streets. The film’s last shot is alone worth the price of admission.

No Mercy for the Rude (Korea): This time the hitman is a mute (or is he?) vowing to kill only the really bad people, and hoping to accumulate enough pay to afford an operation on his “short tongue.” He falls in with a street kid and a hooker, and as the seriocimic plot unfolds we get the very Asian insistence that childhood innocence can be recovered even in the midst of carnage. The film indulges in some flights of fancy—a hitman’s picnic, a hitman who’s a ballet dancer—before coming to its satisfying end in, of all places, a bullring.

Faceless Things: Warnings about gay sadomasochism to the contrary, this doesn’t offer much you can’t see in Warhol or Waters. What it does provide is three shots. The first, nearly 45 minutes long, provides virtually a one-act play about a motel tryst between a businessman and his teenage lover. The second shot shifts us to an anonymous sexual encounter that is admittedly fairly off-putting, but handled with the mix of casual framing and off-kilter suspense we find in, again, Warhol. The very last shot is very brief and puts the other two into a new context. Director Kim Kyong-Mook is only in his early twenties, but his ambition and daring make him a filmmaker to watch.

My last night has come all too soon. So just to make sure that the Europeans are still at work, I’ll check on the French cop movie Le Petit Lieutenant. I’ll end with another Dragons and Tigers entry, the Taiwanese movie Do Over.

Maybe a Chinese dinner afterward. Film isn’t the only thing that Asians do well.