Archive for the 'Directors: Johnnie To Kei-fung' Category

The boy in the Black Hole

PTU.

DB here:

Films from Hong Kong’s Milkyway company earn a lot of praise for their visual qualities. Shooting in Technovision, Johnnie To Kei-fung and other directors have created some of the most vivid and fluid imagery in contemporary cinema. But the movies have soundtracks too. What about them?

When I saw Tsui Hark’s Time and Tide (2000), I staggered out exhausted. I was overwhelmed not only by the delirious plot and its cascade of feverish imagery—who else puts the camera inside a dryer at a laundromat?—but also by what seemed to me the most elaborate soundtrack I’d ever heard in a Hong Kong film.

Shortly after seeing the movie, I visited the Milkyway headquarters and met Martin Chappell, the sound designer of Time and Tide. (For his credits and his company information, go here.) I figured that he could help me hear more in all movies, not just his own.

Years later, during my spring visit to Hong Kong, I got my wish. Martin gave me an interview and sent me several information-packed emails. As I’d hoped, he taught me to listen better.

At the console

Martin Chappell is a concussive burst of enthusiastic energy, an impression aided by the fact that he looks about sixteen. He loves moviemaking and sound design. Growing up in England, he started as a bass guitarist and audio fan, and he studied music and acoustics. When he graduated he worked in sound studios and became a roadie. After a year in Australia, he moved to Hong Kong and got a job in a radio station.

Soon he was working at TNT, creating sound effects for cartoons and dubbing American movies into Mandarin. Hired briefly away by MGM, Martin then shifted to Milkyway. His first effort there was helping on the mix for The Intruder (1996).

Now, with over fourteen years of audio engineering experience, he is sovereign of sound at Milkyway. Ensconced at the heart of Milkyway’s facility, Martin presides over what he calls the Black Hole. The company’s sound studio consists of several rooms, including a Foley studio that is a black hole within the Black Hole.

By Hollywood standards, these studios are minuscule. (Compare the mixing theatre I visited last year for 3:10 to Yuma.) As usual in Hong Kong cinema, work must be fast and tight. Martin typically has a sound crew of three, sometimes including Foley artists. Postproduction sound is usually allotted three weeks, sometimes a little longer. Often he has to prepare a mix on short notice so that visiting critics, festival programmers, or backers can preview a work in progress. As a result, Martin can be found in the Black Hole far into the night, blasting through reel after reel.

Waiting for no man

Most Hong Kong films have a bare-bones approach to sound: dialogue, music, and minimal effects. The sort of detailing that Hollywood offers, especially in Foley techniques, has not been common. There simply isn’t the time and money for a densely mixed track. A lot of time has to be allotted for dubbing the film twice, once in Cantonese and once in Mandarin for the mainland and overseas Chinese market. As a result, even the best Hong Kong films often have a dry, vacant ambiance, which is commonly masked by music. (Perhaps the wall-to-wall music in Wong Kar-wai’s films is an effort to supply a rich sound texture in the absence of other options.)

But Time and Tide had more resources. As part of a Sony initiative to expand into Asian production, which also yielded Crouching Tiger and Kitano’s Brother, it had a large budget by Hong Kong standards. Martin had three months for sound postproduction, “the longest schedule I’ve had in my life,” and a sound crew of eight.

Martin found Time and Tide “a beautiful learning experience.” Working around the clock under the tutelage of veteran postproduction supervisor Hui Koan (The Blade, The Legend of Zu), Martin was encouraged to take chances. He could create rich Foley tracks—remember the tinny ricochet of the little boy’s abandoned skateboard?—and he borrowed ideas from Fight Club, Gladiator, and The Matrix. He was layering sound in the Hollywood manner, albeit on a smaller scale. And he pushed toward wilder possibilities. He recalls the pleasure of putting jungle bird calls under early shots of clubbers wandering through nighttime traffic.

Out and about

Hong Kong looks lovely, but Martin thinks that it’s just as breathtaking in its noise—“a rich sonic soup.” Virtually every chance he gets, he heads out to record in the field.

I pretty much never leave home without my Edirol R-09, and I have a Zoom HR for portable hard disc recording.

It’s important to have a recorder with you all the time. You never know when some drunk is going to burst into song whilst lying in the gutter. In Sparrow, Simon Yam challenges Ka Dung to steal the cop’s handcuffs when they’re outside a bar late at night. So I just pulled the recording I’d made earlier of some drunk guys singing karaoke. It was late one night, I was walking back from the pub, and I heard it echoing out an alleyway.

I feel I’m incredibly lucky. I went out one night to get fresh recordings of a minibus for Linger. I’d scouted the spot, but when I got there the heavens opened and I didn’t have an umbrella. I ran to a nearby bridge—serendipity. I realize it’s next to a tram road, so I recorded buses and trams in the rain, and these sounds feature prominently in Sparrow.

Martin’s wife Marisha often comes with him, either operating or providing effects herself. Recording on the fly freshens up his library, and keeps him alert to new possibilities.

I’m always hoping for a gift from the Ear in the Sky. I’m actually trying to type quietly now, but there’s a band playing downstairs and it’s coming through the walls. They sound terrible, but I think it could be used for a bar scene—late night outside somewhere? . . .

You can see Martin on location in a two-part TV show here.

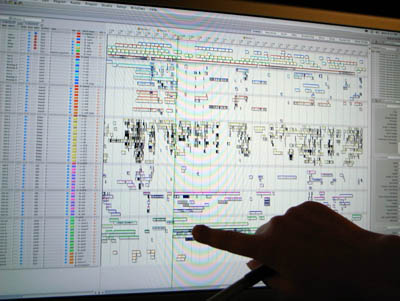

Back in the studio, Martin revels in software like his Digital Performer and Propellerhead Reason programs. His setup isn’t a Mercedes, like ProTools, he says, more of a Lexus—but in some ways it’s more flexible than the more famous option. Johnnie To wants rich tracks, so “Now I spend almost all my time on Foley and ambience.” Martin “finds the flavor” of the sound through his synthesizer.

I load a recording into Reason and I can play with it in real time on my keyboard—pitching it up or down, sweeping the filters, tweaking the equalization. I do so much with ambiance like this. Sometimes I tie it to the picture, other times I just play on a whim. . . . It’s almost fun.

Alongside his high-tech equipment, Martin employs some home-made items, such as his gobo panel, an upright mesh of stones that is virtually a sculpture (above). The gobo can muffle or redirect sound. Placed between two sources, it can allow clean recording of each track.

Every gun makes its own music

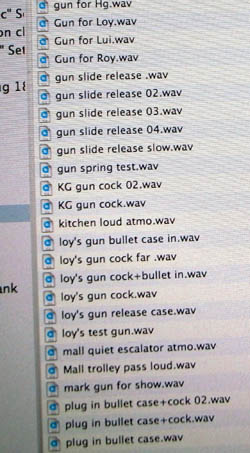

In The Mission, each of the five bodyguards gets a different pistol. Martin gave each one a different sound, labeled in his files by the actor’s name. Here “Roy’s gun” is sometimes coded as “loy’s gun,” and there are plenty of other discrete sound bits on file.

I asked Martin about the mall shootout, which has become a classic in the genre.

There seemed to be so much space in there, and we were adding artificial reverbs, but none of them seemed to work real well. That’s when we decided to experiment a bit, developing things we’d tried in A Hero Never Dies. We just put in the tail of a cannon firing. So that phrase “Bring out the big guns” is literally true here.

There was also a really long gap between some gunshots. We tried adding more, but it felt too busy. So we tried lengthening each gunshot, with the cannon tail reverberating. But that still wasn’t long enough, so we started playing with it, almost jamming with the music. We time-stretched the cannon tails, not just a bit like you’re supposed to. It gave a very artificial but tense sound. If you think it’s music, it might well be.

But even then it wasn’t long enough. So before the next pistol shot, we actually reversed the cannon sound. We get the reversed echo first, then we hear the shot itself! It feels like time has slowed down, then speeded up.

Martin might also have mentioned that these wavering gun reports swoop across left and right channels, creating a dynamic acoustic space for cinema’s most static static gunfight.

Martin also shared his thoughts on the role of sound in fleshing out characterization. After reading Walter Murch’s book In the Blink of an Eye he began to think about how to use sound subjectively. The result was the PTU scene in which Lam Suet, head bandaged, smoking in his car, suffers auditory hallucinations.

Martin acknowledges that there are plenty of conventions that audiences would miss if they weren’t present. When a character hangs up the phone on another character, the disconnected line is signaled through a beep or hum, even though this seldom happens in real life. Martin would also like to hear mobile phone calls in that “headphone bleed-through” effect. He’d also like to handle dialogue like that, “half-overheard, not fully comprehended.”

Still, he finds ways to bypass conventions. In PTU, when the officer played by Simon Yam is abusing the suspect in the video arcade, Martin avoided the library whacking sound, what he calls “the Foley kung-fu cloth flap.” Simon’s slaps are synched to explosions, whizzing missiles, and other arcade sounds. (I offer a visual analysis of one scene in PTU here.)

Ear in the sky

Martin believes that in most films, there’s an immediate need to establish the setting, the placement of the characters, and the scene’s mood. This is done through images, of course, but sound plays an important role. Often a wide shot orients us generally, while sound focuses on one zone of action in that space. “I would guess if you watch TV with no sound, it would be very difficult to really focus. Sound can bring out the visual and guide the eye.”

As an example, Martin walked me through a few moments in Sparrow. The elusive Chun Lei has gulled a quartet of pickpockets, and they pursue her to a rooftop. As the men explore it, we hear traffic and a distant plane, which evokes Chun Lei’s plan to flee Hong Kong.

They spot her on the roof. The suggestion that she might jump is underscored by distant traffic horns.

As the men approach Chun Lei, Martin added distant sirens and a soft wind.

An extreme long-shot provides a still broader sound canvas, with traffic sounds predominating.

In a much tighter shot, as the actors come closer to the camera, the ambiance thins and softens. “Now we time the traffic to underline the dialogue.” Chun Lei leans forward to kiss Bo, trying to provoke the leader Kei to jealousy. We hear echoes of a passing truck, almost as a warning.

Only professionals would probably notice these maneuvers, and there’s a reason. Martin thinks that sound can bypass the conscious mind, working directly on our most visceral impulses (fight or flight?). In this he echoes Gary Rydstrom, quoted in an earlier blog of ours: “Film sound is the side door to people’s brains.”

I’m grateful to Martin for all the time and effort he put into our interview. Next time I see a Milkyway film, or any movie, I’ll listen harder. You too?

Photo by Martin Chappell.

Truly madly cinematically

DB here, still in Hong Kong:

You are a film director. How do you convey to an audience that a character mysteriously sees hidden personalities in other characters?

Filmmakers are problem-solvers, at least sometimes, and I’ve argued elsewhere that we can often explain their creative choices as efforts to pose and solve problems. I ran across an intriguing example during my stay here in Hong Kong. I interviewed Tina Baz, the editor for Johnnie To’s film Mad Detective (2007), which I blogged about from Vancouver in October.

Tina has a fascinating history. Lebanese and French-educated, she attended art school in Beirut and film school in Paris. Armed with a maitrise from the Sorbonne, she began editing. Over a dozen years, she has built up an impressive career. She was editor on The Mourning Forest (2007), A Perfect Day (2005), and several other high-profile projects.

Tina has a fascinating history. Lebanese and French-educated, she attended art school in Beirut and film school in Paris. Armed with a maitrise from the Sorbonne, she began editing. Over a dozen years, she has built up an impressive career. She was editor on The Mourning Forest (2007), A Perfect Day (2005), and several other high-profile projects.

Mad Detective was Tina’s first film for Johnnie To, as well as her first experience with the Hong Kong crime genre. She was accustomed, she says, to the more psychologically-driven narratives of French cinema, and she had to work in a new way during the seven weeks it took to edit the film. This is an unusually long editing time for Hong Kong filmmaking, and it reflects the complicated tasks this film set her.

If you haven’t seen Mad Detective, you will probably want to stop reading. The scenes I’m discussing come fairly early in the film, but they do contain some surprises you might not want to know about in advance.

Headquarters

The rough cut of the film, adhering closely to Wai Ka-fai’s script, displayed a complicated flashback structure. The plot began fairly far into the action and then jumped back to establish the exposition. Central to that exposition is the film’s premise: Detective Bun, played by Lau Ching-wan, solves cases by extraordinary telepathic/ intuitive/ visionary insights. But the original cut blurred that concept, mixing it with an early revelation of the identity of the villain, a corrupt cop named Ko Chi-wai, and background on Bun’s young partner Ho. How to cut through the clutter?

The first step to a solution was to straighten out the chronology and to focus tightly on Bun from the start. The audience needed to understand the film’s eccentric psychological premise—specifically, that Bun’s gift allows him to detect multiple personalities buried within another person.

In talking with me, Tina went over three scenes that establish Bun’s peculiar abilities. (1) The sequences furnish striking examples of how filmmakers find precise technical solutions to storytelling problems. This trio of scenes also follow Hollywood’s Rule of Three. According to this, a key piece of information should be presented three times, preferably in different ways. (2) (Once for the smart people, once for the average people, and once for slow Joe in the back row.) Tina smiled. “This is not something that French directors would say.” The Rule of Three can be seen as another aid to solving the broad problem of clarity—making sure that the audience understands the story.

Discussing all three scenes adequately would take a lot of space and require dozens of stills, so I’ll concentrate on the first two. These should suffice to show how the filmmakers solved a tricky narrational problem.

The first scene takes place in police headquarters and it’s the simplest. It starts with Bun absorbing details of Ho’s investigation. We hear, offscreen, a whining woman complaining that a maniac can’t solve a case. We think at first that it’s the voice of another cop, but after a second complaint from offscreen, Bun looks up. Cut to the whining woman, who stands among the cops.

Bun rises and walks to a pudgy cop who grins ingratiatingly. Now cut from the cop to the whining woman, in a similar composition against the same background.

An over-the-shoulder shot presents Bun staring as we hear the fat cop asking, “Do you recognize me?”

After the fat cop flatters him, Bun head-butts him. Bending over the fallen cop, Bun says, “Shut up. I see and hear you, bitch!” Cut from the bloody-nosed cop to Bun to the bloody-nosed woman.

After Ho dismisses the team, Bun slowly approaches and confides: “I can see the inner personalities of a person” (below). This line of dialogue crystallizes what we’ve seen–the bitchy woman inside the ingratiating man–and prepares for the next few scenes.

On the street

The second vision scene is more complicated, and Tina had several discussions with To and Wai about whether to include it. The new problem, based on the key line above, is to establish that Bun can see not one but several hidden personalities in Ko, the crooked cop. How can this premise be shown?

The major scene coming up shows the two partners confronting Ko at a restaurant. There Bun will envision some of Ko’s inner people manifesting themselves. But there’s also dramatic conflict to be conveyed in the scene, which culminates in a beating in the men’s room. Again, too much information! Tina, To, and their colleagues decided to include an intermediate scene, one that had little dramatic consequence but got audiences more comfortable with the premise.

Ho and Bun trail the suspect along the street, first in a car and then on foot. The results have the kind of precision I’ve pointed to in another Milkyway film, PTU.

In the car, Tina’s cutting establishes the differences between the two cops’ points of view. A two-shot of Ho and Bun yields to a straightforward POV shot of Ko striding along the sidewalk.

But a cut to Bun watching is followed by a shot of seven people in Ko’s place. In a nice instant of uncertainty, a few heads emerge from behind a parked van and are only partially visible. At first glance we might take them for passersby walking ahead of Ko.

Before we can fully identify this band of spirits, and as the car draws abreast, a cut to Ho watching leads to a shot of Ko, whistling.

Another cut to Bun, and now we see, as he apparently does, a full view of the platoon of Ko-personalities striding along whistling.

This mildly wacko variant is consistent with the narration’s mixed attitude toward Bun’s visions: are they supernatural insights or hallucinations?

Bun leaps from the car and pursues Ko’s band of personalities, and a new variation shows him and them in the same frame. But this is re-framed by Ho’s POV, which reasserts that to anyone but Bun, Ko is all by himself.

Abruptly, the visions halt and turn, staring at Bun. By now we are trained to understand what’s happening without a corresponding objective shot of Ko. Ko, we infer, has turned around to check on who’s following him.

Likewise, we can grasp the image of Bun passing through the group of figures as simply Bun walking past Ko.

At this point, we have no need to see the objective action. To and Tina have stressed the absence of an objective view by showing Ho, in the background, looking in another direction and missing this byplay (above). After Bun has passed, the troupe of avatars walks in their new direction, and then we get the objective shot of them “as” Ko.

This effect is anchored when Ho turns and notices Ko going into the restaurant.

As a meticulous touch, Ko’s departure from the frame reveals Bun still walking away in the distance. The geography is simple and impeccable.

The idea of seeing “inner personalities” has been made concrete while undergoing a lot of variation. Sometimes shots of the spirits are sandwiched between shots of Bun looking; sometimes not. Sometimes we have Ho to verify what’s really happening, but sometimes not. And sometimes Bun can be in the same frame as the avatars. Otherwise, Tina points out, the scenes would become boring.

Once the street scene has laid out how Bun sees Ko Chi-wai, the next scene, unfolding in the restaurant and a men’s toilet, can play with the premise still more. Tina explains that the creative team constantly asked, “How far can we go with Bun’s point of view, his vision?” Quite far, it turns out. The premise gets varied further across the whole movie, in imaginative ways. Which is to say that a solution to a problem can pose new problems, which the filmmakers go on to grapple with.

In our discussion, Tina noted that the street scene goes beyond simply giving us information. There’s a disquieting emotional effect when the spirits turn and confront Bun, their expressions ominously blank. Finding a solution to a creative problem often yields an unexpected payoff like this.

Bonus features

As I indicated, I can’t pursue the felicities of the restaurant scene here. Instead, here are some quick final thoughts.

*Mad Detective shows once more the power of basic techniques of performance (e.g., the act of looking), framing, and editing. To and Wai have no need for fancy CGI effects to evoke the “inner personalities” of Ko or the other cop. Our minds make the necessary connections. Lev Kuleshov would have admired the engineering economy of this sequence.

*In passing Tina and I talked about actors’ eyes, a special interest of mine. (3) Tina had noticed that actors try not to blink. She agreed that blinks pose problems for editors: “Blinking is very hard on cutting.” She remarked that Elia Suleiman would strain to keep from blinking until tears flowed from his eyes.

*Mad Detective was signed by both Johnnie To and Wai Ka-fai, but their joint projects are usually filmed by To, with Wai supplying the script and consulting as production proceeds. Tina confirms To’s habit of shooting with the whole scene’s layout in his head, using very few takes per shot and not a lot of coverage. The film is “very pre-cut,” she says. You can see this, I think, in the way To relies on matches on action and ends one shot with something that prepares you for the next one.

*To follows Hong Kong tradition of adding all the sound in postproduction. This makes for economy and efficiency in shooting, but it also gives HK films the fluency of silent cinema. The filmmaker gains a freedom of camera placement and is encouraged to think about how to tell the story visually. Tina and Shan Ding, To’s all-around assistant, pointed out that sync sound might make the director depend more on dialogue and static conversation scenes. Still, I think that sometimes they wish for a scene shot with direct sound.

*As with many Milkyway films, several scenes were filmed at the company headquarters. An earlier blog here discussed the ambitious rooftop set for Exiled. For Mad Detective, the fistfight in the restaurant toilet was filmed in the main men’s room of the Milkyway building, with a fake urinal added. Shan Ding provides documentation in the snapshot below, using a double for Lam Suet.

To come: Another Milkyway interview, this one with ace sound designer Martin Chappell. And a final batch of impressions from the Hong Kong International Film Festival, which ends on Sunday.

(1) If you know Mad Detective, you’re aware that Bun’s ability to discern hidden personalities is displayed in an earlier scene. But given the way in which that story action is presented, we can’t say that that his powers are established there. This scene is one of many clever narrational stratagems in a film that benefits from being rewatched.

(2) See Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), 31.

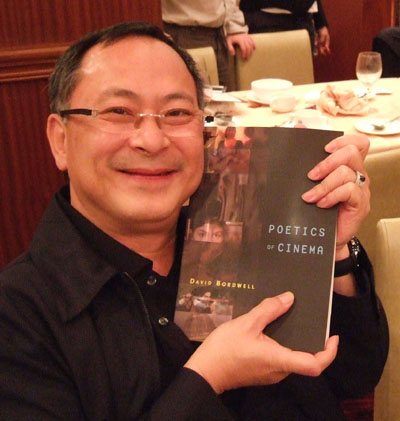

(3) Laugh if you must, but I wrote an essay about this. “Who Blinked First?” is available in Poetics of Cinema.

Party time in Hong Kong

Today, pix from two get-togethers during the Hong Kong International Film Festival.

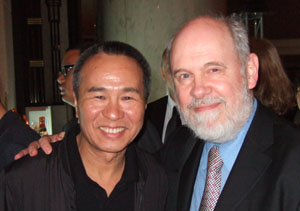

Johnnie’s dinner

Johnnie To gave another of his legendary dinners, this time to a crowd of filmmakers, distributors, festival directors and programmers, and hangers-on like me. The meal was old-school HK fusion, mixing Brit colonial food (boiled tongue, boiled potatoes, boiled veggies) with unique local variations (pigeon, a puffy vanilla soufflé). I think it’s akin to what Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung scarf down so elegantly in In the Mood for Love. Very tasty.

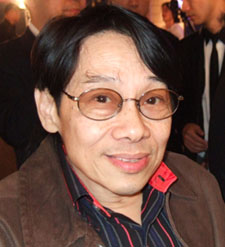

Among those present: Director Kirk Wong.

Kirk made The Club (1981), Health Warning (1982), Gunmen (1988), and other classics, including the 1994 double-header Organized Crime and Triad Bureau and Rock ‘n’ Roll Cop. These are terrific movies, admired by every fan of action cinema.

Festival consultants consult: Mike Walsh (Melbourne, Adelaide); Stephen Cremin (Far East Film Festival of Udine, Screen International); and Todd Brown (S x S W, FantAsia, Twitchfilm).

Cameron Bailey, Co-Director of the Toronto International Film Festival, lets me try an Ozu-style composition.

A small bolt of lightning

One of the most appealing things about Hong Kong film is that character actors, as we call them in America, go on and on, becoming not only stars but directors and producers. As Leslie Cheung pointed out, the local audience is loyal to its favorites and encourages them to try many things.

Eric Tsang, the short, cherubic guy with the perpetually hoarse voice and blinding smile, began, surprisingly, as a soccer player. In 1974 he became a bit player and stuntman in Shaws’ martial-arts releases. He directed two of the movies in the top-grossing Aces Go Places cycle (1982, 1983), and rose to become a screen personality. He’s so familiar to Hong Kong movie lovers that we couldn’t call him Tsang; he’s just Eric, and he’s irreplaceable.

He worked steadily and hard, appearing in nine films in 1985 and an astounding seventeen in 1988. Several of his performances are superb: playing a small-time loser in Final Victory (1987), a flamboyantly gay music coach in He’s a Woman, She’s a Man (1994), a philandering policeman in the exhilarating and little-known Task Force (1997), a wistful romantic in Metade Fumaca (1999), and of course an implacable triad boss in the Infernal Affairs trilogy (2002-2003). He perks up every movie he graces, rescuing routine projects with his beaming ordinariness. In a fairly ordinary policier like Cop on a Mission (2001), he starts out as a thuggish menace and becomes not only sympathetic but heroic in his devotion to his errant wife.

Cop on a Mission is one of several of Eric’s films screened in the HKIFF tribute. The event also emphasizes his role as a producer. Thanks to him, we have The Outlaw Brothers (1990), Dr. Mack (1995), Men Suddenly in Black (2003), Jiang Hu (2004), and several films he coproduced with Peter Chan Ho-sum. Most recently, Eric has launched a project to support young directors. He launched Winds of September, a feature trilogy about coming of age in the “three Chinas”—the mainland, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

For the premiere of Tom Lin Shu-yu‘s Taiwan entry on Friday night, the festival held a little party for several hundred of Eric’s closest friends. For once, that last phrase is no joke; everybody feels close to him.

Glamor to spare: Cheng Pei-pei, of Shaws’ glory days and since, with her daughter Marsha Yuan Zi-hui.

Peter Chan, fresh from the success of The Warlords, chats with Tony Rayns.

Michelle Carey, Festival Editor of the encyclopedic online journal Senses of Cinema and scout for several film festivals. Alongside, Cheung Tat-ming, idiosyncratic young actor; check out his laid-back performance in Once Upon a Time in Triad Society 2 (1996).

Also there were Teddy Robin Kwan, a wonderful actor and pop singer who first made his mark with movies from Cinema City, and Albert Lee, this year’s Executive Director of the festival.

And Eric was as entertaining from the back as from the front.

Next time, I promise more on the movies. I close with two items:

Strangest line of the last twenty-four hours: From inside a hotel room I was passing: “Mom, I haven’t mentioned a threesome until now.”

Johnnie To shows himself a man of outstanding taste.

And I show myself a man of no shame. But you knew that already.

THE place

“For us, Hong Kong will always be the place.”

Chuck Norris, The Octagon (1980)

DB here:

Hong Kong’s Entertainment Expo, including the Hong Kong International Film Festival, the Asian Film Finance Forum, and the Hong Kong Filmart, runs for nearly a month, and it has drawn me back to the fragrant harbor. For refreshers, you can visit last year’s posts here.

Biz

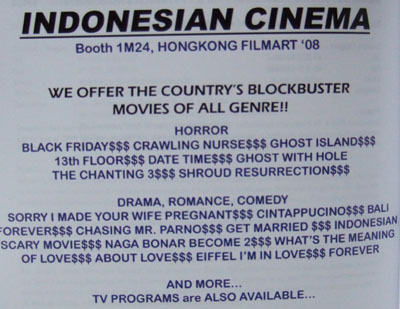

The Filmart has become Asia’s biggest spring media event, with hundreds of companies crowding into a pavilion of the Convention Centre. Here people traffic in movies and TV shows, buying and selling distribution rights, seeking funds for production and partners in movie ventures. I wandered through it last year, and you can track this year’s activities at Variety’s site here.

The last figures I saw indicate that the world pumps out about 4800 features each year. Coming to a market like Filmart, you get to peek below the waterline and see the iceberg that’s underneath.

There are, for instance, the bulk genre items from secondary, or tertiary, producing countries.

There are the films that seem somewhat derivative.

Then there’s the vehicle with the midrange star that just might make it to late-night cable.

Finally, there are the films that acknowledge themselves to be identical. These descriptions come from Imagination Worldwide’s catalogue ad.

By contrast Filmart mounted a respectful display devoted to Edward Yang, who died last summer. Edward made idiosyncratic, powerful films that would, even today, be very hard to sell at a market. He was a skilled cartoonist, and the display includes some of his perky storyboards and a self-portrait.

The Asian Film Awards, which I covered last year, started things off with a midsize bang Monday night.

The full results can be found here. I was pleased that Secret Sunshine, quite a good film, won three top awards (film, director, actress). Milkyway, a favorite company of mine, garnered a couple of prizes, and The Sun Also Rises, one of my favorites from last year, did pick up the Production Design prize.

Some Big Stars were visible at both the show and the after-party. Heartthrob Tadanabu Asano arrives.

Lee Kang-sheng and Tsai Ming-liang mingle before the awards.

Marco Muller, Director of the Venice Film Festival, at the after-party.

I got to talk briefly with one of my heroes, Hou Hsiao-hsien.

And of course Tony Leung Chiu-wai, emblem of the Entertainment Expo and winner of the Best Actor Award (Lust, Caution), was everywhere, and always looking good.

Within 36 or so hours, I saw quite a lot of movies. With friends Paisley Livingston and Mette Hjort and their kids I caught Enchanted, which pleased me with its schmaltzy cleverness. As part of the Festival, I re-watched on 35mm two movies I’d seen and commented upon last year: Jiang Wen’s The Sun Also Rises and the Tsui/ Lam/ To Triangle. These were shown at the shock-and-awe auditorium of a new cinema in a spanking new mall, Elements. The seats vibrate at the lowest frequencies, creating what is marketed as “4-D.”

At Filmart I saw the Luc Besson production Taken, another satisfying dose of formulaic filmmaking. Altogether different was Manuel de Oliveira’s Christopher Columbus, The Enigma. The title suits this apparently slight film about a historian’s earnest pursuit of Portugal’s influence on North American history. Haunting images of 1940s Manhattan swathed in fog, along with touching scenes of Mr. and Mrs. Oliveira visiting historic sites, linger.

Two films struck me as excellent. Gao Qunshun’s Old Fish (2008) centers on a simple idea. Somebody is planting bombs throughout Harbin, and an aging police officer is the only person remotely qualified to dismantle them. Over a leisurely half hour, we’re introduced to Old Fish, his wife, and his colleagues. Then the first bomb is found, and the suspense kicks in. The apparently clumsy codger, who in an early scene fumbles a World War II grenade, summons up wiliness and delicacy when he has to defuse the mysterious packages.

Two films struck me as excellent. Gao Qunshun’s Old Fish (2008) centers on a simple idea. Somebody is planting bombs throughout Harbin, and an aging police officer is the only person remotely qualified to dismantle them. Over a leisurely half hour, we’re introduced to Old Fish, his wife, and his colleagues. Then the first bomb is found, and the suspense kicks in. The apparently clumsy codger, who in an early scene fumbles a World War II grenade, summons up wiliness and delicacy when he has to defuse the mysterious packages.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen more tension-filled sequences of this sort. The film made me realize that in any bomb-disposal scene, when close-ups of a sweating face and a knifeblade hovering over a wire are followed by an extreme long-shot of the scene—that’s when we expect an explosion. Conventionally, the long shot announces the bang. But here, Gao gives us the long shot, and we have to wait, and wait some more. When the explosion does come, it is genuinely surprising.

Shot by shot and sound by sound, this is a very well-crafted, humane film. If anybody tells you that “foreign films” are digressive and boring, show them Old Fish.

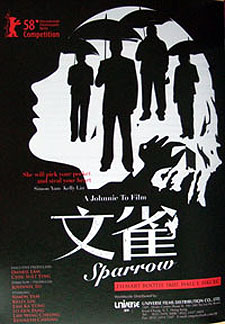

Just as fine, but more unclassifiable, was Johnnie To Kei-fung’s The Sparrow (2008), premiered at Berlin. A gang of pickpockets led by Simon Yam is beguiled by a mysterious lady on the run (Kelly Lin), and their schemes start to fall apart. As often with To, the conception of the film is slim, but the execution is rich. There are the games and competitions, the symmetries and repetitions, the offhand motifs (here, cigarettes, cigars, and pipes), the geometrical and arithmetical plot mechanics. Johnnie To has become perhaps the world’s most unpretentiously, unapologetically formalist director.

It’s a procession of twists and set-pieces. There are the funny one-off shots, like the two grifters with symmetrically broken legs and the gang flashing the razor blades they hide in their mouths. Some sequences are unpredictable miniatures, like the scenes that show how many camera angles you can find in an elevator car, even with a fishtank squeezed in. There’s also a delirious bit with a lipstick-stained cigarette.

Other set-pieces unfold more majestically. There’s a sweeping crane shot of the gang vacuuming up wallets of passersby, and an elaborate theft of a pendant during massage therapy. The climax is an exuberant pocket-picking competition with all contestants stalking through a downpour, their umbrellas forcing them to work with only one hand.

The Sparrow is at once a loving tribute to old Hong Kong island (Simon’s hobby is black-and-white photography), an unpredictable genre piece, and an exercise in light-fingered filmmaking. Like Old Fish, it offers lessons to Hollywood directors, if they have the wit to learn them.

Bits

At Filmart, Fred Ambroisine multitasks, taking cellphone calls and shooting docu footage at the same time.

Deng said “To get rich is glorious,” and now Mao agrees.

And in the spanking new, gargantuan mall known simply as Elements, an entire room is devoted to one essential Element.

More to come, soon I hope, from The Place.