Archive for the 'Digital cinema' Category

TIFF: More than movies

Audiences gather for screenings at the Bell Lightbox, hub of the Toronto International Film Festival.

DB here:

Around midnight tonight, the crowds packing the Toronto International Film Festival will disperse, leaving the city full of memories of another extraordinary year. I’ve been back in Madison for this last week, but my few days at TIFF remain on my mind. This is partly because along with the films came a lot of ideas, opinions, and information. At any festival, fraternizing with audiences, critics, and programmers is one fine way to get that stimulation. It happened after some of the Wavelengths section’s short-film programs. Here are Raymond Phatanavirangoon and Bob Koehler outside the Art Gallery of Toronto, where their Devo retro-stylings raised our conversation to a new level.

More structured sessions delivered too. Out of my 4-plus days at the Toronto International Film Festival, I set aside about one and a half for industry panels and filmmaker Q & A’s. Let me tell you a little of what I learned.

From Assayas to Asia

TIFF: Where programmers meet stardom.

The talkfests I attended shed light on both film artistry and film business-making. Central to the first area was the master class with Olivier Assayas, hosted by Brad Deane.

Assayas, a charming fellow, talked fluently about how Something in the Air (discussed here) bears traces of his youth. During the 1970s, high-school kids were “footsoldiers of the cultural war of the time.” He recalled his affinities with the artistic side of the counterculture, as opposed to the extremes of the political activists, some of whom, being aligned with Maoism, refused to recognize the Cultural Revolution as “disaster on a demented level.” Yet this shouldn’t be taken as apolitical aestheticism; Assayas has been a vigorous advocate for the work of Situationist Guy Debord.

Assayas was refreshingly detailed about his working methods. He writes only one draft of his screenplay, partly because he wants to protect the “digressive” aspects of his story. (This tendency is apparent, and enjoyable, in Something in the Air.) Since his films are difficult to classify within standard genres, he needs to cobble together creative financing for each project. But the script becomes obsolete when he casts the film and visits locations. By embodying the characters, the actors create beings “more powerful than what I’ve written.” Working with them, he refuses to supply background on the characters’ psychology. “I look to them to understand the characters.” This hands-off approach yields striking results in the new film, where nearly all the cast is non-professional.

Assayas was refreshingly detailed about his working methods. He writes only one draft of his screenplay, partly because he wants to protect the “digressive” aspects of his story. (This tendency is apparent, and enjoyable, in Something in the Air.) Since his films are difficult to classify within standard genres, he needs to cobble together creative financing for each project. But the script becomes obsolete when he casts the film and visits locations. By embodying the characters, the actors create beings “more powerful than what I’ve written.” Working with them, he refuses to supply background on the characters’ psychology. “I look to them to understand the characters.” This hands-off approach yields striking results in the new film, where nearly all the cast is non-professional.

Assayas doesn’t undertake elaborate rehearsals, instead coming to the set each morning and describing the shots they’ll make. He wants to take account of the evolution of the film as it’s been developing. He doesn’t fully block the shots. He sketches each one in longish takes that, as the actors expand on the action, “add layers” to what he’d initially planned. Alternatively, he cuts up the long takes and combines pieces of them. For Something in the Air, he relied on stable and wide framings, partly in reaction to trends toward handheld shots and close-ups, partly because he used the crane to create a “floating,” more lyrical circulation through the space.

Artistry, mixed with business sense, was apparent in one of the panels at the Asian Film Summit’s day of meetings. Colin Geddes hosted a session on Asian genre cinema, and several producers and directors shared thoughts on action cinema as an international genre. Fanboy blood pulsed high.

Artistry, mixed with business sense, was apparent in one of the panels at the Asian Film Summit’s day of meetings. Colin Geddes hosted a session on Asian genre cinema, and several producers and directors shared thoughts on action cinema as an international genre. Fanboy blood pulsed high.

Eli Roth (left), another kid who grew up with Kung-Fu Theatre on TV, was bowled over years later by Korean and Japanese thrillers like Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance. Now Roth is producer and co-writer of The Man with the Iron Fist, directed by RZA–who is, according to Roth, letter-perfect on his kung-fu film knowledge. “We wanted to do a movie like we saw as kids on Saturday afternoon.” But production values in the genre have swollen since the old days. The project is using the Hengtian studio’s vast replica of the Forbidden City. RZA, Roth says, expected The Last Emperor to be a kung-fu movie, so this is his attempt to make things right.

Tom Quinn, Co-President of the Weinstein Company’s RADiUS division, had similar affinities. As he pointed out, East Asian countries have strong local markets and so can build a base in genre cinema. With quantity comes quality. While working at Goldwyn and Magnolia, Quinn handled US distribution for The Host, Pulse, Tears of the Black Tiger, and most recently 13 Assassins, along with many other titles. Ong-Bak, on view at TIFF in 2004, was a particular triumph for him, yielding over a million dollars in its first weekend of release and eventually garnering $4.5 million in the US. Even the heavy piracy of Ong-Bak Quinn takes as a positive sign, “a validation of the film’s value.”

Bill Kong, a legendary Hong Kong producer and a force behind Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, along with Stephen Fung, director of Tai Chi 0 (above), filled out the panel. Overall, the discussion ranged widely, but one question kept cropping up. Why is it that Western films are widely popular in Asia, but Asian cinema is almost completely a niche market in the West? I didn’t hear a clear answer (though I’d start an answer with Western racial prejudice).

Kong noted that Asian filmmakers don’t have high expectations about penetrating the US market, but other panelists were more hopeful about crossover projects. Quinn pointed out that the festival circuit built an audience, and Roth thinks that Tarantino has been a major player in making Asian film more popular, especially with the Kill Bill duet. The fact that Russell Crowe plays a major part in The Man with the Iron Fist suggests that things may be changing.

Bigger than Bollywood

Mira Nair.

The East/West dynamic was also the focus of two other panels. “India: Lessons from Bollywood and the Independents” brought together a nearly all-female group of experts to discuss local financing and wider distribution. All were agreed that it was necessary to convince the world that Indian cinema was bigger than Bollywood. As director Dibakar Banarjee put it: “We need to open the third eye.”

The local industry has a certain comfortable inertia. A film might cost only $150,000, but it can collect 90% of its production costs upon its opening run, said Shailja Gupta, who has been both a director and production executive. Foreign distribution is a major risk at this budget level. So how does a project, particularly an independent film, get international traction?

Coproductions are an obvious path, and while they are still rare, the trend is emerging. The Indian government’s National Film Development Corporation Ltd. has helped with coproductions since 2006, says Nina Lath Gupta, NDFC Managing Director. Such enterprises are rare and mostly involve France or Germany. By establishing the Film Bazaar in 2007, the NDFC acknowledged the importance of marketing as well as financing, and this is getting local filmmakers acquainted with the need to think more globally.

Another path to the overseas market was suggested by Guneet Monga (right). She is a producer on the network narrative Peddlers and the two-part gangster saga Gangs of Wasseypur; both earned very good buzz at TIFF. Monga pointed out that sales agents can help shape projects for international distribution.Working with Elle Driver, she was able to generate three versions of Gangs, targeted for different regions. Moreover, sales agents can help a film by avoiding the old practice of selling it as a single package. Instead, the agent can pre-sell it with a minimum guarantee and negotiate territorial rights further down the line.

Another path to the overseas market was suggested by Guneet Monga (right). She is a producer on the network narrative Peddlers and the two-part gangster saga Gangs of Wasseypur; both earned very good buzz at TIFF. Monga pointed out that sales agents can help shape projects for international distribution.Working with Elle Driver, she was able to generate three versions of Gangs, targeted for different regions. Moreover, sales agents can help a film by avoiding the old practice of selling it as a single package. Instead, the agent can pre-sell it with a minimum guarantee and negotiate territorial rights further down the line.

Mira Nair, distinguished director of Salaam Bombay and Monsoon Wedding, has long enjoyed worldwide exposure, of course. She shared her thoughts on how filmmakers could follow their visions and still, as she put it, “put bums on seats.” That’s accomplished by not worrying about distribution but devoting energies to creative choices–such as she undertook in The Reluctant Fundamentalist, her first foray into the thriller genre.

During the India panel, moderator Meenakshi Shedde asked if China might become a coproduction partner for local films. This is currently not happening, but the question reflects the significance of the People’s Republic on the global film scene. Earlier in the day, a panel on “Financing Between Asia and the West,” moderated by Patrick Frater, concentrated mostly on China as the leading edge of the region. Once more, the question of coproductions was central.

“Coproduction is a reality now for global filmmaking,” declared Peter Shiao, CEO of Orb Media Group. But the power of China in the new media landscape has created a false optimism among Western entrepreneurs. Shiao warned newcomers that coproductions can’t be fulfilled in good faith with perfunctory gestures, such as including a Chinese actor in a secondary role. (The Expendables 2 was mentioned in this connection.) Aspiring filmmakers need to grasp and follow the China Coproduction Film Office regulations straightforwardly.

Solid coproductions are rare, agreed Bruno Wu, founder and chair of many top Chinese media groups. He pointed out that what works in China won’t necessarily work in the rest of the world, but what works in the rest of the world is likely to work in China. So the Chinese investor needs to look at projects that will play internationally. He gave as examples his firms’ deals with Justin Lin and John Woo, who have reliably won global audiences. Along similar lines, Stuart Ford, founder and CEO of IM Global, suggested that a good alternative to coproduction involves soliciting equity investment from China for Western films. For example, Chinese investors in Paranoia, a $40 million production, acquired mainland distribution rights as part of the deal.

The soundness of investing in Western films seems borne out by local box-office figures. Seventy percent of China’s market receipts come from English-language imports; the several hundred domestic films produced earn only twenty percent. And theatrical receipts provide, according to Peter Shiao, ninety percent of a film’s earnings. Windows in the Western sense don’t exist, and there’s no legitimate home video market. Gradually local filmmakers are experimenting with Western ancillary tactics; Painted Skin: The Resurrection recently tried out apps and games.

China-based Video on Demand is more promising. In a few years, Wu expects there to be several million addressable HD cable homes, and providing entertainment on demand might provide a way around the national quota system for film import. There is no quota restraining VOD distribution, and as it takes hold, it might reduce piracy.

A killer app? (as in killing off business?)

Jonathan Sehring and Winnie Lau at the VOD panel at TIFF, 9 September 2012.

Speaking of VOD, in early September I signed up. I did it partly because there was one title I needed to see immediately: Keanu Reeves’ Side by Side, the documentary about the digital vs. film controversy. More abstractly, I had been learning a little about VOD when I recast and expanded my blogs on digital exhibition for Pandora’s Digital Box, and I was curious about how VOD worked in practice.

After a period of turmoil, the US film industry has integrated VOD into its system of non-theatrical ancillaries. Before, we had DVD and Blu-ray, both rental and retail, along with movie channels like HBO and Sundance available on subscription cable. Eventually movies would show up on basic-cable channels. There was also “pay per view” via cable, a one-off transaction now known as Pay TV VOD.

Now, the internet has expanded the options.

*Electronic Sell-Through (EST) allows the consumer to download a film and own it. This service is available through iTunes, Amazon, and other outlets.

*iVOD (internet VOD) is a one-off rental, to be run immediately or within a specified time period. To check the 1.77 aspect ratio on Dial M for Murder, I rented it for 24 hours on iTunes.

*Subscription VOD (SVOD), which you get with Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, and other providers. This option provides a library of titles available at any time for a monthly fee. SVOD is comparable to cable-television subscriptions, and it’s becoming very popular, as all-you-can-eat options tend to be.

In addition, another option hovers over the business:

*Premium VOD (PVOD) consists of a one-off rental available sooner than the traditional home-video window. The transmission would be via cable or satellite, not the Net, and the price point has typically been $30 for one viewing. The studios tried out PVOD with DirecTV in 2011, with apparently unencouraging results. Worse, last year’s Tower Heist fracas, during which Universal planned to put the film on PVOD 30 days after theatrical release, triggered threats of boycotts from exhibitors. PVOD, however, is likely to reappear at some point because it can offset losses from the declining DVD market.

No surprise, then, that one industry panel was called “VOD Killed the DVD Star.” The session assembled major players in that domain to discuss the present situation and the prospects for the future.

Much of the panel’s time was devoted to explaining why filmmakers needed to be flexible about accepting VOD as a legitimate complement to or substitute for theatrical release. VOD, they insisted, shouldn’t be seen as a dumping ground for weak or narrow-interest films. The reason: The consumer is king, and consumers want everything on demand.

Winnie Lau, Executive Vice-President for Sales and Acquisitions at Fortissimo, said that companies now recognized that consumers should be able to see a film on whatever platform they want. Given the high costs of a theatrical release, that option isn’t justifiable for many films. Philip Knatchbull, CEO of Curzon Artificial Eye, put the case more strongly, declaring that with the consumer in control, notions like windows and “on demand” are losing their usefulness. His view suits a company that, like IFC, has integrated video and theatrical distribution with theatre ownership and HD delivery. There are, he suggested, only home cinema and public cinema, and everyone in the film value chain should be aiming to reach millions of screens.

Tom Quinn of RADiUS was working for Magnolia when in 2005 Mark Cuban experimented with a multiple-platform release of Bubble. “His vision,” Quinn recalled, “was to make films available whenever people liked.” The Bubble experiment was problematic because it came out on film and on DVD simultaneously, but Quinn said that “the hotel VOD numbers were through the roof.” This summer, after twelve months of preparation, RADiUS has issued its first VOD titles, and Bachelorette, released earlier in September, won notice for earning about half a million dollars in its first weekend.

The prototype of longer-term VOD success is the later career of Edward Burns. Burns, who had his first success with the breakout indie movie The Brothers McMullen (1995), was lively and articulate. “VOD helped me stay in business.” He knew firsthand the slow rollout that characterized 35mm platform release in the 1990s, along with the months of press tours. In the years that followed, he realized that his movies–basically, as he put it, people bullshitting with one another around a kitchen table–had shrinking theatrical prospects. In 2007, he offered Purple Violets exclusively on iTunes. This came around the time that IFC and Magnolia were experimenting with day-and-date releasing on different platforms.

The prototype of longer-term VOD success is the later career of Edward Burns. Burns, who had his first success with the breakout indie movie The Brothers McMullen (1995), was lively and articulate. “VOD helped me stay in business.” He knew firsthand the slow rollout that characterized 35mm platform release in the 1990s, along with the months of press tours. In the years that followed, he realized that his movies–basically, as he put it, people bullshitting with one another around a kitchen table–had shrinking theatrical prospects. In 2007, he offered Purple Violets exclusively on iTunes. This came around the time that IFC and Magnolia were experimenting with day-and-date releasing on different platforms.

Burns was satisfied with the results and built a production model around VOD. The cast and crew work for free and collectively own the film. Budgets can be low; he claimed last year that Newlyweds cost only $100,000. Payments are deferred, and if a film breaks through, everyone makes money. His last three films, he reported, did. He compared the business model to that of an indie band. VOD gets his work to the people who watch HBO, Showtime, AMC. “That’s our audience.”

Burns is an unusual instance, since as one panelist pointed out, he has established his own brand. Still, other VOD releases can break out. The most widely publicized example is Margin Call, with about $4.5 million on VOD. Jonathan Sehring, President of IFC and Sundance Selects, was a pioneer of alternative platforms, and he remarked that 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days did better on VOD than in theatrical release (where it grossed $1.2 million). In a recent interview, Sehring indicates that the recent IFC release About Cherry as doing as well as Bachelorette on VOD and other revenue streams.

It seems, then, that these and other industry decision-makers see VOD as offering two avenues, depending on the film. VOD can provide a new window, to be added before or after or during theatrical release. Alternatively, VOD can replace theatrical, as it has done for Burns (who will still occasionally give a film like the upcoming Fitzgerald Family Christmas brief theatrical play). With this option, many films, both domestic and imported, will never see a theatrical release but they might make money on the less costly VOD platform.

The problem for the second strategy is finding a way to make the film stand out from the thousands of titles available in cable and VOD libraries. A theatrical release provides the “shop window,” as Knatchbull called it, but without that, the film needs other salient features–big stars or cult buzz–to attract the home viewer.

Despite the panel’s title, the guests didn’t predict that VOD would displace discs. In fact a couple of panelists agreed that DVD and Blu-ray would be around quite a while. Quinn (left) confessed that as someone who grew up with VHS he would always be collecting his favorite films on physical media.

There’s something else to consider: some dramatic disparities between VOD and DVD consumption. The differences are spelled out in a recent IHS Screen Digest report.

On one hand, the VOD audience has grown rapidly. The report counted transactions–buying a movie in any form–and came up with striking figures for the world’s top five regions.

2007: DVD retail and rental: 2.7 billion transactions; online VOD in all forms: 14.8 million transactions.

2011: DVD retail and rental: 2.58 billion transactions; online VOD in all forms: 1.4 billion transactions (nearly all SVOD).

The Screen Digest team estimates that 2012 will see an even bigger burst in online VOD, totaling 3.4 billion transactions, with nearly all that via subscription. (I’m in there somewhere.) By contrast, physical media sales and rentals are predicted to fall further, to 2.4 billion transactions.

The disparity lies in “monetization.” We have some access to weekend box office grosses, but almost none to income from DVD and VOD, so comparison is difficult. Still, everyone knows that DVD purchase and rental, along with pay TV licensing, yield the bulk of film revenues. In another research report, Screen Digest estimates that in the US the 2012 surge in VOD will yield only $1.72 billion. DVD will yield $11.1 billion, nearly ten times the VOD transactions. Even with the declining retail and rental prices of discs, VOD yields much less per transaction than DVD does, especially with subscription services leveling out the cost to consumers.

So did VOD kill, or at least wound, the DVD star? When measured in transactions, yes. In revenues, no. Moguls pay off their Ferraris in dollars, not transactions, so it seems that VOD would have to expand colossally, or raise prices, or both, to come close to achieving the returns of DVD.

It’s conceivable that VOD will cannibalize other windows, if you’ll excuse the mixed metaphor. DVD transactions were going downhill before the rise of VOD, but perhaps VOD will accelerate that plunge. iTunes already charges up to $20 for EST downloads of a new release. As consumers become used to storing their movie and TV collections digitally, the convenience of EST could hurt DVD sales.

Moreover, VOD has always threatened the theatrical market. That’s why exhibitors cried foul when Premium VOD was tried. But box-office grosses overall remain robust because ticket prices are constantly rising and 3D and Imax rely on upcharges. These revenues offer studios a good reason to maintain strict windows, at least for their most successful releases. Still, studios are very likely to continue to press for PVOD. And indie distributors have embraced VOD release exuberantly. Foreign and indie titles released on VOD before or during the theatrical run may steal business from art houses.

In sum, VOD might shake up the other platforms quite a bit. If your analogy is the music business, theatrical and DVD formats stand in for albums, while VOD is the online force that lowers consumers’ sense of a fair price point. There’s some discussion of raising prices for some iVOD and Pay TV VOD offerings to parity with theatrical ticket prices. I wonder if consumers will sit still for that. As a novice VOD’er who likes going out to see movies big, I probably wouldn’t. Unless Hulu’s Criterion library discovered a lost Mizoguchi.

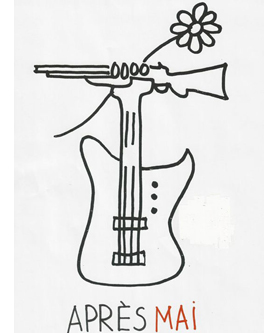

Assayas’ autobiography A Post-May Adolescence has just been published in English translation. It includes two essays on Debord. At the same time, an anthology of critical essays on Assayas, edited by Kent Jones, has appeared in the sterling Austrian Film Museum series.

Patrick Frater reports on the TIFF Asian Film Summit at Film Business Asia.

My statistics on the progress of VOD come from “Movie Consumption Stabilizes,” IHS Screen Digest (April 2012): 95-98, and “Online Movie Consumption in the US,” IHS Screen Digest (May 2012): 116. See also Andrew Wallenstein’s Variety story, where we learn that Netflix’s subscription model is beating the pants off the competition. Thanks to David Hancock of IHS Screen Digest for further information.

As before, thanks to my Toronto hosts Cameron Bailey, Brad Deane, Christoph Straub, Andrew McIntosh, Andrea Picard, and all their colleagues.

TIFF leaves an indelible mark: The ankle of Crystal Decker, Marketing Manager of Well Go USA Entertainment, US distributor of Tai Chi 0.

P.S. 17 September: Thanks to Anuj Mehta for correction of a misspelled name.

ADD = Analog, digital, dreaming

Luther Price, Sorry Horns (handmade glass slide, 2012).

DB here, just back from the Toronto International Film Festival:

It’s commonly said that any substantial-sized film festival is really many festivals. Each viewer carves her way through a large mass of movies, and often no two viewers see any of the same films. But things scale up dramatically when you get to the big boys: Berlin, Cannes, Venice, and Toronto. I’ve never been to the first three, but my first visit to TIFF was like wading into pounding surf and letting the current carry me off.

This is the combinatorial explosion of film festivals: A hefty 450-page catalog listing over 300 films from 60 countries. Moreover, because it’s both an audience festival and an industry festival where movies are bought, sold, and launched, you observe a range of viewing strategies. Although I sit too close to be much bothered, my friends tell me of mavens darting in and out of shows or checking their cellphones during slow stretches of what’s onscreen. The crowds add to the air of electric excitement, as of course do the visits of glamorous celebs.

So I was inundated. How to choose what to see in 3 ½ days for viewing? (I reserved time for industry panels.) I knew that some of the prime titles, such as Kiarostami’s Like Someone in Love or the remarkable-looking Leviathan, would be available for Kristin and me at Vancouver later in the month. And I saw no reason to stand in queues for Looper, Argo, and other movies that I could see in empty Madison, Wisconsin multiplexes during off-peak hours.

I still missed many, many things I wanted to catch. For much wider assessment of major movies, you should go to the coverage offered by the tireless scouts of Cinema Scope and the no less tireless scouts of MUBI. Here I’ll talk just about a few films that made me think about—no surprise—digital vs. analog moviemaking.

Fragments and figments

Mekong Hotel.

Stephen Tung Wai’s Tai Chi 0 (0 as in zero) represents everything we think of when we say that digital production and postproduction have transformed cinema. This kung-fu fantasy from the Chinese mainland (but using Hong Kong talent, including the director) retrofits the genre for the video-game generation. CGI rules. The result is, predictably, monstrous fantasy—a globular iron behemoth, a sort of Steampunk locomotive version of the Death Star—but also screens within screens, GPS swoops, tagged images, Pop-Up bubbles identifying the cast, and other scribbling that turns the movie screen into a multi-windowed computer monitor. One more thing Scott Pilgrim must answer for.

Jang Sun-woo played with similar possibilities in his 2002 Resurrection of the Little Match Girl, inserting character dossiers and creating digital effects mimicking gamescapes. But he sometimes paused to give these images a dreamlike langor. Tai Chi 0 never lingers on anything and instead carries the level of busyness to crazier heights. In a panel at the Asian Film Summit, Fung explained that one scene of the film was inspired by a particular online game. Sammo Hung was playing Fruit Ninja or something similar and Fung decided to include a scene of villagers turning away invading soldiers with a barrage of produce.

Fung said as well that fantasy martial arts remains a blockbuster genre in the PRC (viz. the success of Painted Skin: The Resurrection). Tai Chi 0 ends on a cliff-hanger, the end titles (rolled too fast to read) provide a trailer for part 2, and apparently a third part is in the works. Now China has franchise fever.

The stop-and-start plot is familiar from Hong Kong films of the 70s onward (including over-made-up gwailo villains), but its execution wrecks nearly everything I like about classic kung-fu movies. Clearly though, I’m not in the audience the movie is aimed at. My friend Li Cheuk-to, artistic director of the Hong Kong International Festival, opined that this digital froth could be very appealing to China’s online generation.

Tai Chi 0 exemplifies what academics writing on digital have talked about as the “loss of the real.” As Tom Gunning pointed out back in 2004, though, things aren’t so simple. Digital photography, after all, remains photography. The lens intercepts a sheaf of light rays and fastens their array on a medium. The fact that a shot can be reworked in postproduction doesn’t mean that every digital image must surrender the tangible things of this world.

At TIFF, the power of digital cinema to bear witness was on display in Sion Sono’s Land of Hope. Sono has already documented Japan’s 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Himizu, which I haven’t seen, but in that and Land of Hope, he abandons the wacko bad taste that made Love Exposure and Cold Fish so memorable. This is a sober, traditional drama presented with straightforward economy. It takes place in a fictitious district, Nagashima, but the fact that the name combines “Nagasaki” and “Hiroshima” suggests the gravity of Sono’s approach.

Three couples’ lives are torn apart by the quake, the tsunami, and the collapse of the nearby nuclear power plant. (All of these catastrophes are kept offscreen, glimpsed in TV reportage.) The oldest couple refuses to evacuate, clinging to their farm. Their son and his wife move to a nearby city where they succumb to the fear of radiation affecting their unborn child. And an unmarried couple wander the ruins looking for the girl’s father.

Sono intercuts the three lines of action. The old farmer adroitly manages his wife’s dementia and lets her indulge her fantasy of dancing in a village festival. In a critique of Japanese conformity, the young couple is shown being mocked for their worries about radiation poisoning. (The wife seals their apartment and, in a touch recalling the grotesque side of Sono, takes to wearing a Hazmat suit.) Less sharply developed are the fairly aimless ramblings of the youngest couple, though Sono injects some suspense when they dodge police blockades. At intervals, plaintive Mahler (a Sono weakness) surges up to underscore the futility of their search.

Throughout, government reassurances and the media’s insistence on putting on a happy face are treated with robust skepticism. Instead, Sono celebrates a dogged persistence to get through each day. The young couple’s mantra of “one step, one step” supplies the upbeat tone of the last scenes. As affecting as you’d expect is the footage of areas around the plant, seen as a wintry wasteland. Like Rossellini filming in bombed Berlin in Germany Year Zero, Sono has shot precious footage of ruins that testify to a calamity in which nature conspired with human blunders. And he did it digitally.

You can’t expect something so conventionally dramatic from Apichatpang Weerasethakul, and Mekong Hotel doesn’t supply it. It’s as relaxed as Tai Chi 0 is frenetic, and its central conceit makes it another pendant to Uncle Boonmee. The boy Tong and the girl Phon meet from time to time on the terrace of the hotel overlooking the river. They talk about folk traditions and the flood then besieging Thailand. They also encounter spirits that are as tangible, even mundane as they are; Phon’s dead mother appears in her room occasionally knitting. More shocking are the ghosts called Pobs who seem to possess the characters and make them hunch over and gobble intestines, sometimes in situations that suggest the organs have been torn from another character. All these scenes are handled with the usual Weerasethakul tact: long-take long shots, usually one per scene, that push the everyday and the extraordinary to the same unruffled level.

Mekong Hotel seems to operate on two planes of time. On the image track and in the dialogue, we witness Tong and Phon on the terrace or walking along the river. But the music, snatches of repetitive guitar tunes, seems to come from another time frame. At the start we see a guitarist practicing, and his noodlings run almost constantly under the drama we see. Another motif, fixed and lustrous shots of the Mekong River, yields a visual if not dramatic climax: a slowly paced choreography of Jet-skis crisscrossing the water. Here the digital medium may work to Weerasethakul’s advantage, with the clouds and landscape hanging unmoving over the racing watercraft, as a single, slow ship wades into the middle of their oscillating geometry.

The analog alternative

I suspect that Olivier Assayas filmed Something in the Air (originally Après Mai) on film, but even if he didn’t, the movie is a tribute to analog reproduction–mimeograph machines, LPs and turntables, and cinema in its different guises, from exploitation films to agitprop and experimental lyrics. We all know that the 1960s continued well into the 1970s, and here Assayas shows the uneasy carryover with a mixture of sympathy and critical detachment. The film starts with our high-school protagonist Gilles carving a peace symbol into his desk, flagrantly ignoring the teacher’s lecture. The shot encapsulates the film’s tension between political activism and image-making, and Gilles will oscillate between them in the course of the plot.

The poles come to be represented by two young women—the wealthy and ethereal Laure for whom he makes his paintings and the more hardheaded leftist rebel Christine, who goes out with him and others on nightly graffiti raids. When Laure leaves for London, Gilles continues his painting while leafleting and splashing slogans on walls, with the occasional Molotov cocktail to spice things up. The copains’ rebellion leads to some harm, but they cling to their ideals.

The poles come to be represented by two young women—the wealthy and ethereal Laure for whom he makes his paintings and the more hardheaded leftist rebel Christine, who goes out with him and others on nightly graffiti raids. When Laure leaves for London, Gilles continues his painting while leafleting and splashing slogans on walls, with the occasional Molotov cocktail to spice things up. The copains’ rebellion leads to some harm, but they cling to their ideals.

When summer comes, Gilles joins a film collective headed to document workers’ struggles in Italy. He encounters the arguments that made me smile in nostalgia: Shouldn’t revolutionary content have a revolutionary form? But how shall we reach the working class if our films are opaque? Assayas, who grew in this period and was repelled by the Maoist dogmatism of Cahiers du cinéma and Cinéthique, evokes these debates to remind us that the counterculture was about art and political change at one and the same time. Something in the Air chronicles a few years when imagination mattered.

After an early, shocking clash of students pounded down in a police riot, the film adopts a more circumspect rhythm, salting its scenes with books, magazines, record albums, and songs of the time. The plot keeps our interest by delaying exposition about the characters’ family lives until rather late. When we learn that Gilles’ father writes scripts for the celebrated Maigret TV series, we’re invited to see his forays into abstract painting as his form of teen rebellion. The plot doesn’t mind straying a bit from Gilles, as when his friend Alain, another aspiring artist, gets caught up in the fervor and pursues a wispy red-haired American dancer.

Characters meet, work or play together, drift apart, re-converge, and eventually settle into something like grown-up life. But at the end, when Gilles has apparently been absorbed into commercial filmmaking in London, he is granted one last vision of one of his Muses, who reaches out for him from the screen of the Electric Cinema.

Analog triumphs as well in The Master. Sitting in the front row of Screen 1 at the TIFF Lightbox (see below), I was astonished at the 70mm image before me. Not a scratch, not a speck of dust, not a streak of chemicals, and no grain. So did it have that cold, gleaming purity that digital is supposed to buy us? Not to my eye. The opening shot of a boat’s wake, which will pop up elsewhere in the movie, was of a sonorous blue and creamy white that seemed utterly filmic. Now we know the way to make movies look fabulous: Shoot them on 65.

The Master, as everybody now knows, centers on Freddie Quell, an explosive WWII vet, and his absoption into a spiritual cult run by the flamboyant Lancaster Dodd. Followers of The Cause are encouraged, through gentle but mind-numbingly repetitious exercises, to probe their minds and reveal their pasts. With the air of a charming rogue in the young Orson Welles mold, Dodd seems the soul of sympathy. But like Freddie he’s capable of bursts of rage, especially when his methods are questioned. Freddie becomes a sidekick because of Dodd’s fondness for his moonshine, while he also serves as a test case for the efficacity of The Cause’s “processing” therapies. If you can get this hard-bitten, borderline-sociopath in touch with his spiritual side, you can help, or fleece, anybody.

Like There Will Be Blood, this movie is primarily a character study. That film gained plot propulsion from Daniel Plainview’s oil projects, but many situations worked primarily to reveal facets of his dazzling self-presentation, his repertoire of strategies for dominating others. Something similar happens with Dodd and the ways he charms his congregation. But here the action is more episodic and the point-of-view attachment is dispersed across two characters. Dodd’s counterbalancing figure, the clenched Freddie, is so difficult to grasp psychologically (at least for me) that the film didn’t seem to build to the sort of dramatic, even grotesque peaks we find in other Anderson projects.

This is also a story about an institution, a quasi-church with a pecking order, rules, and roles. I wanted to know more about how The Cause worked, how it recruited people, and how it garnered money. Laura Dern plays a wealthy patron who lets the group stay in her home, and at one point Dodd is arrested for embezzling from the foundation, but the details of his crime aren’t explained. I also wanted to know more about the group’s doctrine, which seems so vague that Scientology need not worry about being targeted. The rapid-fire catechisms between Dodd and his acolytes are gripping enough, as Q & A dialogue usually is, but what system of beliefs lies behind them? The film seems to fall back on the familiar surrogate father/son dynamics at the center of most Anderson movies, but here filled in less concretely.

In short, after one screening I was left thinking the film was somewhat diffuse and flat. But I need to see it again. I thought better of Boogie Nights and Punch-Drunk Love after re-viewing them, so I look forward to trying to sync up with The Master on another occasion. Alas, in Madison, Wisconsin, I won’t have a 70mm image to entice me.

A bit of each, and both

Luther Price, No. 9 (handmade glass slide, 2012).

Analog imagery came into its own on other occasions, notably during the two programs of experimental films gathered under the heading “Wavelengths.” (At one I spotted Michael Snow in the audience.) Expertly curated by Andréa Picard, these programs assembled some strong, provocative films by several young filmmakers. I won’t review each one here–Michael Sicinski provides very useful commentary on nearly all those I saw—but I must mention the striking slide show that served as an overture one evening. The images didn’t move, exactly, but they might as well have.

Luther Price has been making remarkable films on 8mm and 16mm for several years, and one Wavelength program featured his Sorry Horns, a three-minute mix of abstraction and found footage. The same mix was evident in the procession of stunning handmade glass slides. Many, like the one surmounting today’s entry, evoke early cinema, decay, and clichéd Christian imagery: the wounds of film deterioration become cinema’s stigmata. Even the sprocket holes and soundtracks are invaded by festering particles. Arp-like blobs, pockmarked faces, and spliced and sliced movie frames lie under grids as irregular as medieval leaded windows. This is all gloriously analog.

No less captivating is the new, 100% digital work of an even older master of American avant-garde cinema. In one Wavelengths program Ernie Gehr offered us Departure (2012), a train trip playing on optical illusions in the spirit of Structural Film. We all know what it’s like to sit on a stationary train but then feel, when another train passes, as if we’ve started to move. Gehr translates this kinesthetic illusion into optical terms by filming, first upside down and then in judicious framings, several railbeds rushing by, faster and faster.

These layered ribbons sometimes unfurl right, sometimes left, and sometimes simply hover there as fixed, pulsating strips, all but losing the details of rail and tie and spike. Sometimes the one on top moves right, the grass verge beside it moves left, and the bottom track moves right (or left). This creation of flip-flop movement harks back to Side/Walk/Shuttle (1991) and to Gehr’s 1974 exercise in traffic abstraction Shift, which filmed patterns of commuter traffic from a very high angle.

Accompanying Departure was one of nineteen pieces in Gehr’s Auto-Collider series. Most of them contain some recognizable imagery, Gehr explains, but not number XV, the one we saw. In a sense the distilled essence of Departure, that film’s whooshing planes become vibrant, and vibrating, stacks of bold color, a bit like Daniel Buren in a joyous mood.

How did Gehr create the gorgeous Auto-Collider images? He declined to explain. Kristin suggested a plausible means to me, but I’m keeping quiet. In the analog age, when new methods of abstraction required a lot of sweat equity, filmmakers freely explained their painstaking work with lenses, light, and optical printers. But digital video practice flattens the learning curve. Powerful discoveries like Gehr’s or Phil Solomon’s are very easily replicated without much time, toil, or talent. Hell, somebody would make an app for them.

These artists are right to have trade secrets, just as magicians do. We should be satisfied merely to look. What we see reminds us that both analog and digital media harbor possibilities that go beyond the ability to replicate phenomenal reality. Both media can also dazzle us with things we’ve never seen, or imagined.

Digital projection seems to be taking over the festival scene, if TIFF is any indication. Cameron Bailey reports in a tweet that of the 362 films screened, 232 (64%) were in the Digital Cinema Package format and another 79 (21%) were in HDCam. The remainining 51 (15%) were in 16mm, 35mm, and 70mm.

Are the digital items still films? Robert Koehler suggested that maybe we will start calling everything movies. Interestingly, at the Wavelengths screenings, the artists called their artworks (whether on film or on digital video) “pieces.” Me, I still vote for calling films films, even if they’re on video, just as we have books in digital formats (such as, oh, I don’t know, this one). For me, at least these days, a film is a moving-image display big or small, whether it’s on film or some other medium. For some purposes we may want to specify further: Just as e-book and graphic novel indicate a platform or a publishing format, TV movie or video clip tells us more about what kind of film we have.

See also my January entry on festival problems with digital projection.

Thanks to Cameron Bailey, Andréa Picard, and their colleagues for enabling my visit to TIFF.

The industry screening of The Master at TIFF. Photo by M. Dargis.

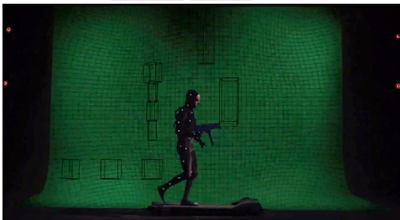

Beyond praise 5: Still more supplements that really tell you something

Real-time performance-capture images for The Adventures of Tintin.

Kristin here:

The Extraordinary Voyage (2011, Serge Bromberg and Eric Lange)

I had expected to follow up my entry on Hugo when the DVD was released. I anticipated that its supplements would explore the flashy technical and artistic aspects in detail. But the lengthy first chapter proved to be largely the cast and crew presenting variations on how lucky they were to have worked with Martin Scorsese (and each other) and how much they learned from him.

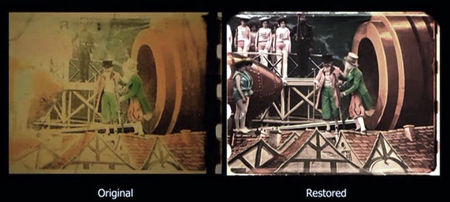

That wasn’t promising, and I turned instead to Georges Méliès himself. Flicker Alley, which has served the filmmaker so well in the past (see here), has recently released the restored color version of A Trip to the Moon in a Blu-ray/DVD combination set. It is accompanied by a 65-minute documentary on the Méliès, the film, and the restoration. It’s odd to call a 65-minute film that accompanies a fifteen-minute “feature” a supplement, but I recommend it anyway.

I suspect that The Extraordinary Voyage would be quite effective in easing students into very early silent cinema and intriguing them about an era that must seem hopelessly remote to them. It begins with a charming introduction to the context of the turn of the previous century and then moves quickly into the director’s young-adult life. When it comes to the famous incident in which Méliès’ camera jammed while he was filming, creating an inadvertent magical transformation, the filmmakers have an actual 1937 recording of Méliès himself describing the event. Presumably this was the original source of this oft-repeated anecdote. He specifies that it happened on the Place de l’Opéra and involved a bus turning into a hearse. I still wonder if it all happened so neatly, but hearing it directly from Méliès makes it a little more plausible. If it wasn’t true, it should have been.

The film includes as talking heads several filmmakers who admire Méliès’ work: Costa-Gavras, Jean-Pierre Jeunet, Michael Gondry, Tom Hanks, and Michel Hazanavicius. There is a good summary of the fascination with the moon in popular culture of the day,  including works by Jules Verne, Jacques Offenbach, and H. G. Wells.

including works by Jules Verne, Jacques Offenbach, and H. G. Wells.

The documentary touches on issues relevant to early silent cinema in general. One of these is the frequent pirating of films, with Méliès starting an American branch of his Star Films in New York, under the direction of his brother Gaston, to help protect his intellectual property. A clip from the Segundo de Chomon version of the film, An Excursion to the Moon, is included.

At about 23 minutes in, a short overview of early movie music is given, followed by a helpful explanation of how the hand-coloring of Méliès’ films was handled by a local workshop run by women. At 30 minutes in there are several dazzling examples of hand-colored scenes (right).

After a quick summary of Méliès’ decline and death, the film moves to the restoration of the only known hand-colored copy of A Trip to the Moon, found in the film archive in Barcelona. Here the hero is Tom Burton, the Director of Technicolor Creative Services, who gives a brief indication of how computers have transformed restoration:

We have a palette of digital tools to work from that are a collection of maybe five or six of the main commercially available restoration platforms, but then we also bring into the mix all of the approaches that you would use if you were doing visual effects for a modern movie.

The comparison of visual effects with restoration is in some ways an apt one and might lead students to look upon early films in a new light.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (Blu-ray/DVD/Ultraviolet set, Sony Pictures Home Entertainment)

It’s probably a good idea to supply both Blu-ray and DVD discs in one package, but including the supplements only in Blu-ray is annoying and increasingly common. That’s the way the Girl with the Dragon Tattoo discs have been handled. Teachers without access to a Blu-ray player have fewer options when trying to use supplements in teaching. It also makes it much more difficult to make frame grabs from the supplements to, say, illustrate a blog entry on useful supplements.

I decided to check out the supplements for this film because the ones for Zodiac and The Social Network were so good. I figured David Fincher was particularly concerned about his films’ bonus materials. Unfortunately this set of supplements is quite uneven. The cast and crew seem to be obsessed with the character of the heroine and with the delights of shooting in Sweden. I confess that I stopped watching some of the chapters as the talking heads went on and on about these subjects. Some of the tracks also consisted of a lot of candid behind-the-scenes footage, which is all very well, but there was little structure to this and only occasional comments to explain what was going on.

Fortunately the “Post-Production” section is very informative and interesting. “In the Cutting Room” is fairly technical but makes some fascinating points. I particularly liked the description of how Fincher eliminates reframings and unsteady shots by using the extra image space allowed by newer capture media. (Earlier digital film frames allowed no extra image area outside what would show up on the screen; as the image below indicates, the final frame can be selected from a larger picture.) This desire for a stable image in an era where the “queasi-cam” so often rules points to one distinctive trait in Fincher’s style. It indicates a willingness to actually think through the framing of each individual shot and the purpose for choosing that framing. Steven Spielberg does the same thing. Many don’t.

Editor Angus Wall talks about this advantage of the extra size of the image and how Fincher uses it to stabilize unsteady images. It’s worth quoting at length, and it demonstrates the thoughtful commentary in this particular supplement:

I’ve never seen a movie that was sort of “re-operated” to the extent that this one was. Which I think has an effect on the viewing of the movie. David is really type-A in terms of making the shots very specific. They start in a certain way, they end in a certain way. And the framing, he’s very precise in terms of his composition. He doesn’t like a lot of what you see in 99% of movies, which is very subtle moves where the operator will actually reframe according to how the actor’s moving. David doesn’t like that. Even if there were a lot of those in this film, and before, some of those takes we would have thrown out, because we just wouldn’t have been able to stabilize them to the degree that he likes it. With this, because you have this full raster, this big area around the image, you can take those images and stabilize them, really lock them down. So the movie is really locked down in terms of camera operating. More than any other movie that I can think of.

The smooth glide as the car initially approaches the country house is one example of that utter stability, used to ominous effect in that particular scene.

There’s also some interesting discussion about how the two main characters don’t meet each other until well into the film and how that affected decisions about editing. Rather than frequently intercutting between Mikael Blomkvist and Lisbeth Salander, the filmmakers decided to create longer self-contained scenes involving each, thus switching back and forth less frequently. The idea was that the exposition set forth in each scene would be too difficult to absorb if it was chopped into smaller segments. Form, style, and function, neatly explained.

Fincher also points to an interesting underlying anxiety the spectator might feel because the narrative progress gives little sense of how much action is still to come:

You don’t know where you are in the narrative. You don’t know if you’re at the beginning of the third act or … I don’t think it’s bad, because we have a five-act movie. I think that’s what’s causing everybody’s anxieties, that it doesn’t feel like, OK, here’s where we are, we’re entering the third act now. Now it feels like, fuck, this movie could go on … indefinitely. That’s the part that’s bothering me. If we told them it was going on for another forty-five minutes, they wouldn’t have a problem. It’s the indefinite part.

Since I’ve written a book claiming that classical films usually don’t have three acts, I was intrigued by this statement. (See also my earlier blog entry here and David’s essay here.) I posit instead that classical films typically create acts that run about 25 to 30 minutes, and that the film’s length determines how many acts it has. Four acts is the most common throughout Hollywood’s history, but a 158-minute film would be likely to have five acts. (Has David Fincher read my book?!) His point about the audience feeling a bit lost in an unconventional narrative structure is a rare instance of a director talking about form in such an abstract way, and it seems quite valid for The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

It’s also rare to get a supplement on ADR (automated [or additional] dialogue replacement), but there’s a six-minute one in the “Post-Production” section. This consists of a behind-the-scenes session with Rooney Mara supplying not just dialogue but breathing, grunts, and other noises. It’s clearly a real session, not a staged one, though the actress does seem a bit self-conscious with the documentarian’s camera turned on her. Fincher’s and Mara’s banter between takes gives a sense of what I suspect really goes on during this phase of production.

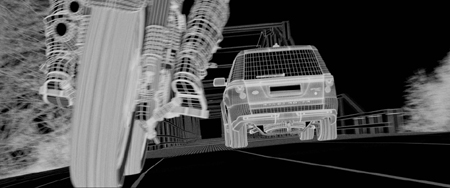

There’s a brief supplement called “Main Titles,” which deals with the form and inspiration for the CGI under the titles. Fincher wanted to tell the story of the whole trilogy in two and a half minutes, “and it has to be spectacular.” Apart from the discussion of form, there’s a good look at unrendered CGI footage compared to the finished images.

Finally, an eight-minute “Visual Effects Montage” displays a variety of special effects in a clever way. There is a section at the beginning where we are shown the image without added effects, then the same image with the areas to be altered highlighted in various superimposed colors, and finally the finished images with the effects added. This is particularly good for showing the sorts of mundane effects that are used to enhance shots unnoticeably, adding cars’ headlight beams, reflections in glass, falling snow, and the like. There is a shot with a section of a building on location blotted out with a greenscreen and the final shot showing the use of alterations in the building:

Obviously here the fog was also added with CGI.

This montage goes very quickly. If you’re using it in a class, best to prepare ahead and be ready to pause and point out what’s going on in the many short shots used in the demonstrations.

The second half of the effects montage moves to splashier scenes of the type the public associates with “special effects”: wire-frame vehicles for a chase (see image at the top of this section), head-replacement to add Mara’s head to her stunt-double’s body, and explosions.

Don’t bother with the “Stockholm Syndrome” section. Basically all we learn is that when a scene is shot on location, sheep can unexpectedly wander in and interfere.

The Adventures of Tintin (Blu-ray/DVD/Digital Copy combo, Paramount Pictures)

Again, the supplements for this release are available only in Blu-ray.

Steven Spielberg and Peter Jackson decided some years ago to collaborate on what was announced to be a three-film series adapted from Hergé’s Tintin comic books. The notion was that each of them would direct one film, with an as-yet-unspecified director doing the third. Spielberg’s initiatory film did not do as well at the domestic box-office as had been hoped, though it fared better in Europe and other non-North American markets, where the comics are highly popular. Jackson has announced that after he finishes both parts of The Hobbit, he will launch into the next Tintin film. (At least, that’s what he said originally. After yesterday’s announcement that there will be three Hobbit films, his start on the Tintin film will presumably be delayed.)

The supplements form a narrative of the film’s making, bookended by “Toasting Tintin” and “Toasting Tintin Part 2,” brief episodes set at the launch and wrap parties. The tale is pleasant and generally worth watching, though they are far from as entertaining and informative as the supplements that Michael Pellerin produced and directed for Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings and King Kong DVD sets. But this is Spielberg’s show, since he did the first film and indeed originated the project. At first he envisioned the film as live-action, with the dog Snowy the only major CGI character. Spielberg asked Jackson’s effects house Weta Digital to do some tests animating Snowy. To his (apparent) surprise, Jackson himself, as a fan of the comics since childhood, played Captain Haddock in the test. That fact was well known to fans, and the inclusion of the test footage (above) is no doubt a crowd-pleaser.

The decision to use cutting-edge performance-capture techniques led to the film being entirely animated.

“The World of Tintin” gives background on Hergé and deals briefly with the screenwriting process. This leads into “The Who’s Who of Tintin,” dealing with characters and acting, with some good material on performance capture near the end. The next section, “Tintin: Conceptual Design” has good material on the visual style of the characters and near the end includes some pre-viz material.

The outstanding supplement, however, is “Tintin: In the Volume,” nearly 18 minutes of footage concerning performance capture. Spielberg’s role as director was primarily concentrated into a remarkably short 31-day shoot with the actors. This was done in a state-of-the-art performance-capture facility called “The Volume” and located at Giant Studios. The Volume is a large space with about 160 cameras built into the ceiling and pointing down into the performance space. These capture the space from multiple angles. Additional cameras on the stage level follow the actors’ movements, which are inserted into the space. Moreover, hand-held monitors similar to portable gaming devices allow the filmmakers to see simple versions of the settings and the partially rendered characters while pointing the device at the actors in their performance-capture rigs.

There are also larger monitors that show the actors their own performances translated into the characters (top of entry). Whatever one thinks of the look of contemporary animation of this type, the technology has evolved to a remarkable level, and this supplement provides an excellent explanation of the practicalities of performance capture. We see the motion-capture suits being put on and the dots painted onto the actors’ skin. There is also information on how the set elements and props need to be transparent so that the cameras can capture the dots on the actors’ faces and costumes through them. The image at the bottom shows Jamie Bell as Tintin looking at a mock-up of the model ship. It’s made of little metal rods and rendered into a ship on the monitors.

“Snowy: From Beginning to End” is less cutesy than it sounds. It discussed the digital tool developed for modeling the dog’s fur. There’s also good stuff on how several dogs were recorded to provide different-sounding barks depending on the type of action in a scene.

The biggest tasks on the film came after the performance capture and editing. Weta Digital spent two years creating the final images. “Animating Tintin” is an excellent eleven-minute account of that process.

The sections “Tintin: The Score” and “Collecting Tintin” (on Weta Workshop’s designs for the collectible figures) are rather thin and could be skipped unless a teacher wants to show the whole set of supplements as a single “making-of” documentary.

It’s become apparent that many of the best supplements on Blu-ray and/or DVD releases are devoted to special effects, especially performance capture. The Adventures of Tintin does genuinely involve innovations in this technology, and the “In the Volume” chapter is very informative. Supplements are getting repetitive, though, and I would like to see the producers of such documentaries pay more attention to techniques and choices in other areas. Comparing final cuts of scenes with earlier cuts, or showing story conferences where real debates about scripts occur (as was done in the first Pirates of the Caribbean film’s supplements), or displaying how decisions about digital-intermediate grading are made–a bit of imagination could spice up the offerings. That and a realization that film fans are interested in just about any aspect of production (or distribution, for that matter). Supplements risk falling into conventional patterns, and that won’t make them the appealing bonus material that they used to be.

While I was gearing up to write this entry, we received Mark Parker and Deborah Parker’s book, The DVD and the Study of Film: The Attainable Text (Palgrave, 2011). Based on a great deal of research, including many interviews, the authors include a summary history of DVDs and supplements; there is a detailed chapter on The Criterion Collection, interviews with directors and scholars who have recorded commentary tracks, and a case study of Atom Egoyan.

Digital projection, there and here

Galeries Cinéma banner, Brussels, 2012.

DB here:

The Cinéma Arenberg, in the splendid Galerie de la Reine, has long been a mainstay of Brussels film culture. Since 1939, the lovely Art Deco theatre was what we Americans call an art-house. Over the years Kristin and I visited the city, the Arenberg’s autumn and spring schedules featured recent releases, but every summer the programmers plunged into plucky repertory programs. While the multiplexes ran Hollywood blockbusters, the Arenberg provided 90 or so classics and little-known releases under the rubric of Écran Total. It was here, for example, that I saw von Trier’s The Kingdom and resaw Vanishing Point. Four years ago I left a little note about the three titles I watched during my last day in town: India Song, Serpico, and Darjeeling Limited. That trio gives you a sense of how varied and interesting the programming was.

The Arenberg closed down at the end of 2011, but the cinema has reopened under new management as Galeries Cinéma. It didn’t sponsor an Écran Total season this year. Instead it offered brand-new releases on its three screens, along with some children’s programs.

Most notable for me this time was Leos Carax’s Holy Motors. Whatever you’ve heard about this film is probably accurate. I found it an exhilarating, frustrating, and continuously provocative descent into Surrealist role-playing. It’s a tour of cinema genres and an anthology of bits of other movies, from Marey to Franju, and not forgetting Carax’s own. Especially evocative were the poetic fusions, such as the way that the body stocking Oscar dons for digital motion-capture evokes both ninja outfits and the leotards of Feuillade’s Vampires. Carax films Oscar’s SPFX exercise in a way that connects Muybridge to video games and recalls the exuberantly spasmodic scene in Mauvais Sang in which Denis Lavant races madly down the street to the accompaniment of David Bowie’s “Modern Love.”

Whether you find Holy Motors infuriating or beguiling, you won’t forget it.

Exquisitely shot on digital capture, Carax’s film was given crisp, bright digital projection at the Galeries. And speaking of digital projection. . . .

The new issue of Film History, devoted to digital technology’s impact on filmmaking and film culture, includes Lisa Dombrowski’s article “Not If, But When and How: Digital Comes to the American Art House.” It’s a very fine survey of all the issues facing the art-film community at this moment. Lisa reviews the major technological and financing conditions before going into depth on a case study of three art theatres in Miami. The author of a very good book on Samuel Fuller, Lisa knows how to tie together industrial and aesthetic issues skilfully.

Another young scholar, this one at the Free University of Brussels, has concentrated on the digital transition in Europe. Since 2005 Sophie De Vinck has been studying how the conversion of theatres fits into European film policy. The result was her 2011 thesis, “Revolutionary Road? Looking back at the position of the European film sector and the results of European-level film support in view of their digital future.” The thesis, running to a whopping 769 pages, is an immense resource, and not just for people interested in digital cinema. Sophie surveys the history of national and international support of the Western European film industry, from production through exhibition, and she provides both a broad context and very specific analysis.

Part of her argument is that the “diversity” aimed at by subsidized filmmaking hasn’t been matched by diversity in audiences. But digitization offers a new chance to show films outside the dominant forms of commercial cinema and perhaps attracted new sectors of the public. “Every innovation usually brings with it possibilities for new or smaller sector players to strengthen their competitive position.” Her examination of how digital conversion affects small and art-house venues provides a complement to Lisa’s research.

I wish I’d known about Sophie’s thesis when I was writing the blogs that became Pandora’s Digital Box, but at least I can signal her work now. Best news of all: Sophie has generously made “Revolutionary Road?” available under a Creative Commons license here as a pdf. Full of valuable statistics and well-honed observations, her work helps us understand how the contemporary European film industry has survived and sometimes flourished over the last fifty years.

Cinema Arenberg, Brussels, 2008. The original design of the curved doorway and neon sign was restored in 2005-2006.

The indispensable site Cinema Treasures has a brief entry on the history of the Cinéma Arenberg/ Galeries. More extensive information can be found in Isabel Biver’s luxurious survey, Cinémas de Bruxelles: Portraits et destins, which I wrote about in an earlier entry.

P.S. 1 August 2012: I just learned from Gabrielle Claes that Giovanna Fossati’s book on digital restoration in film archives, From Grain to Pixel, is now available for free in pdf form here. It’s well worth reading.